Происхождение и значение Исиды в Египте и не только

Исида считалась величайшем богиней. Известно, что она была сестрой, и в то же время женой великого Осириса, и с ним связана достаточно интересная история, о которой мы вам поведаем дальше. Соответственно, Исида была дочерью Нут и Геба, а значит – она была правнучкой верховного бога Ра, с которым Исиду также связывает удивительная легенда.

Роль Исиды, в Древнем Египте, была одна из самых сакральных и значимых. Изначально богиня считалась ответственной за плодородие, за ветер и воду, за мореплавание. Кроме того, Исида считалась и покровительницей семейного очага, супружеской верности и женственности. Кроме того, Исида была ответственна и за медицину, которой она покровительствовала. Ее священным животным был скорпион.

1

В нашей статье о Бастет мы рассказывали, что древние египтяне верили в то, что она является духовным образом богини Исиды. И это вполне вероятно, т.к. зоны ответственности обеих богинь тесно переплетались.

Исиду, отчасти, можно было считать покровительницей людей. Именно ей приписывали создание пчел. Кроме того, женщины Древнего Египта считали, что именно Исида, как богиня верности и супружества, учила людей ткать и прясть одежду, и свадебные наряды, в частности. Но главную славу богине снискало ее покровительство роженицам. Исида считалась покровительницей рожениц. Именно она определяла судьбу новорожденных царей Египта, на родах которых она всегда присутствовала.

Как мы уже сказали ранее, Исида была известна и грекам, и римлянам. Однако страх перед великой богиней был настолько силен, что они не отваживались звать ее иначе, чем «та, у которой тысяча имен». Впрочем, учитывая значение богини в жизни египтян, это совсем не удивительно. Ведь она считалась покровительницей фараонов и их власти, о чем говорил ее головной убор, в виде трона.

Интересный факт, Исида изначально была злой богиней и подавалась как сварливое и бестолковое создание, которое из-за своих внутренних разногласий, не могло найти общего языка не просто с другими богами, а даже с собственным сыном. Однако легенда гласит, что со временем богиня образумилась и из обузы превратилась в благодетельницу.

Наверное, особенно популярной богиня стала из-за своего отношения к мужу, которого она не предала и хранила ему верность до последнего момента. В те давние времена, такое поведение было редкостью, но подробнее об этом мы расскажем далее, в нашей статье.

Внешний вид Исиды и символы, олицетворяющие ее

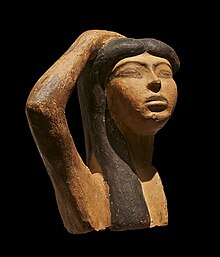

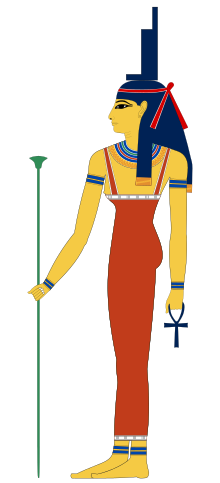

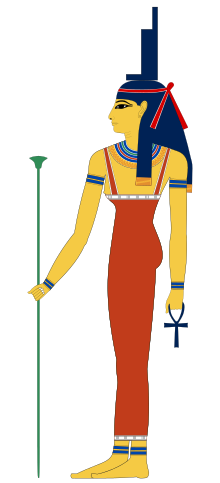

Практически всегда богиня изображалась в антропоморфном облике, т.е. Исида была обычной женщиной. Возможно, именно поэтому к ней привился образ богоматери. Нередко ее изображали как кормящую мать, с младенцем на руках.

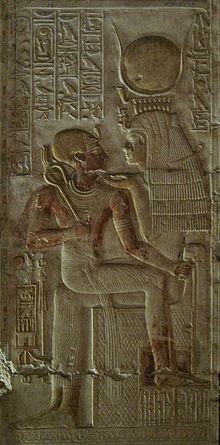

Как мы уже сказали выше, богиня олицетворяла собой власть фараонов, считавшимися ее детьми, поэтому в качестве головного убора у нее располагался именно трон фараонов. Впоследствии Исиду связывали с Хатхор, которая также считалась одним из ее воплощений. Однако об этом говорят очень не многие мифы и легенды, а главное – изображение с головным убором, обладающего рогами коровы.

Символом богини считалась и звезда Сириус, однако это в равной степени может относиться ко всей гелиопольской девятке. Да и вопрос с пирамидами и Великим Сфинксом также являются своеобразными отсылками к этой звезде, что уже несколько столетий позволяет выстраивать различные теории о пришельцах, а точнее о том, что богами Египта были именно пришельцы из созвездия Большого Пса.

Звезда Сириус – одно из небесных проявлений богини Исиды, отлично просматривалась с Земли, поэтому не удивительно, что в свое время моряки избирали звезду, в качестве ориентира, а сама Исида стала еще и покровительницей мореплавателей. Об этом говорят ее изображения, на которых богиня представала с лодками в руках. Кроме того, символом Исиды считалось и покрывало, в котором заключалась ее жизненная сила.

В Древнем Египте, богов часто изображали с различными атрибутами животных, и Исида не стала тому исключением. Несмотря на то, что на большинстве, дошедших до нас, изображений богини она была показана в теле человека, нередко встречались и ее изображениями с головой соколицы или с крыльями, такими же, как и у ее сестры, Нефтиды.

Считалось, что именно этими крыльями она создавала ветер или защищала Осириса. Что касается последнего, то, учитывая его трагическую судьбу, не удивительно, что Исида часто изображается коленопреклоненной, оплакивающей усопшего мужа. Именно их история и стала олицетворением супружеской верности в Древнем Египте.

Насколько почитаемой была Исида в жизни египтян

Еще в самом начале нашей статьи вы могли заметить, что мы сказали о том, что Исида была одной из самых почитаемых богинь Древнего Египта. Она покровительствовала всем людям, вне зависимости от их статуса и ранга в жизни. Таким образом, можно сделать вывод, что Исида прислушивалась к молитвам рабов и богачей, ремесленников и аристократов, девушек и мужчин, угнетенным и угнетающим.

Задать вопрос

Почему Исиду почитали больше, чем других богинь?

Причин тому очень много. Исида изначально ассоциировалась с теми направлениями, которые ценились египтянами, а впоследствии она получила от Ра тайные знания, и родила Гора, считавшегося перевоплощением Ра.

Рекомендуем по теме

Имя Исиды было первым, что приходило на ум египтянам, у которых случилось какое-то несчастье. Но чаще всего Исиду призывали именно на роды, чтобы она помогла разродиться роженицам. Сведения об Исиде дошли до нас и благодаря упоминанию ее гимнов в «книге мертвых».

Учитывая все это, понимаем, что еще одним из знаков отличия богини был амулет тет, изготавливающийся из яшмы и сердолика, красного цвета. Впоследствии ей стали приписывать любовь к золоту и нетленности, покровительницей чего она стала во времена позднего Египта.

Мифы об Исиде

Наверное, мы уже достаточно сильно вас раззадорили своими намеками на различные истории, связанные и Исидой, поэтому не будем больше тянуть, и расскажем несколько легенд об этой богине, дошедших до нас.

Исида и Осирис

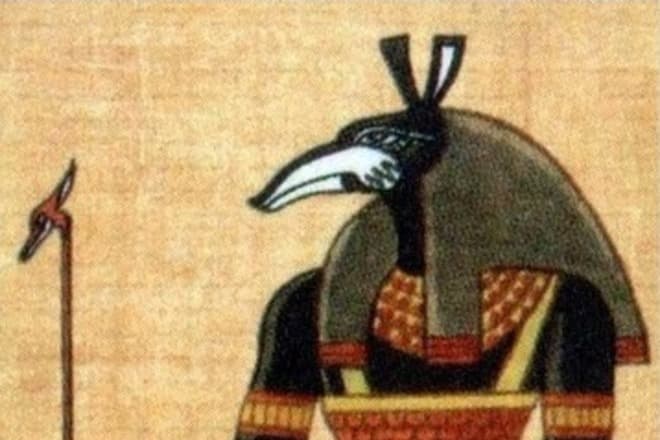

Легенда гласит, что Исида влюбилась в Осириса задолго до их замужества. По одной из легенд – это случилось даже до ее рождения, поэтому не удивительно, что впоследствии она стала его женой. Легенда гласит, что однажды между Осирисом и Нефтидой (сестрой Исиды) случился адюльтер. Узнав об этом, Исида была в отчаянии и так громко вскрикнула, что сотрясла вселенную. По этой легенде, от этой связи родился Анубис.

Согласно этой легенде, истинная неприязнь Сета к Осирису кроется именно в этом. И если так, то последующие действия Сета вполне оправданы и пострадавшее лицо он, а не Осирис, ведь Нефтида была его женой.

По другой версии Сет просто завидовал власти Осириса. Однажды, когда Осирис отправился в путешествие по миру, чтобы распространять цивилизацию за пределы Египта, он оставил вместо себя править именно Исиду. Однако, при возвращении домой, он попал в ловушку Сета, который его убил, спрятал тело в сундук и отправил его в путешествие по Нилу.

Несмотря на предательство Осириса, Исида сильно любила мужа. В отчаянии, она остригла свои прекрасные волосы, облачилась в траурные одежды и отправилась на поиски мужа. Его она нашла на сирийском побережье, Библосе, куда сундук прибило волнами, после долгих скитаний. Однако Сет не остановился на этом. Он отыскал несчастную вдову, отобрал у нее тело мужа и расчленил его на маленькие кусочки, которые рассыпал по всему Древнему Египту.

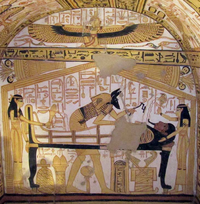

Однако Исида и в этот раз проявила супружескую верность. Она собрала все до единого кусочки мужа, а после, при помощи Анубиса (или Тота), превратила мужа в мумию. После этого она провела особый, сложный ритуал, который ей позволил на один только день вернуть мужа к жизни. Однако и этого вполне было достаточно, чтобы воплотить планы Исиды в реальность. С воскрешенным Осирисом она зачала ребенка, который получил имя Гор, и стал одним из величайших богов Древнего Египта.

Впоследствии Гор сумел одолеть Сета, но не в бою, а на суде, ибо битва их была долгой и жестокой, а силы их были равны. Также Гор сумел вернуть подобие жизни Осирису. Но это уже совсем другая история, о которой мы подробно расскажем вам в статьях о Горе, Осирисе и Сете, непосредственно, а пока – вернемся к Исиде.

Впоследствии упоминаются времена правления Гора. Сет еще не один раз пакостил своему племяннику, но Исида практически всегда выступала на стороне сына, что позволяло тому побеждать. Однако, одна из легенд гласит, что однажды Исиды решила поддержать Сета. Гор не простил матери предательства и отрубил ей голову.

Исида и Ра

Если вы уже читали нашу статью о верховном боге Древнего Египта, о Ра, то наверняка знаете эту историю. В ней говорится о стареющем Ра, истинная сила которого заключалась в его истинном имени, знал которое только сам Ра. Однако хитрая Исида была с этим не согласна. И вот, как это было.

Однажды Исида заметила, что Ра постарел настолько, что практически не отдавал отчета своим действиям. Ра восседал на троне, а с губ его капала на землю слюна. Исида незаметно подкралась к верховному богу и сумела собрать немного его слюны. Ее она смешала с пылью и сотворила из нее особую змею, которую она усилила заклинанием и положила на дорогу, по которой ежедневно прохаживался Ра.

И змея сделала свое дело. Стареющий бог не сумел самостоятельно избавиться от яда, и никто другой из богов не сумел ему помочь. Никто, кроме Исиды, но в замен она потребовала, чтобы Ра назвал ей истинное свое имя, дабы получить могучую силу верховного бога, сокрытую в старом теле Ра, имя, дающее ключ ко всем загадочным силам вселенной.

Однако Ра заподозрил что-то неладное. Он попытался выкрутиться и заявил, что он Хепри утром, Ра в полдень и Амон вечером. Однако этот ответ не утолил жажду таинств мудрой Исиды. И тогда Ра поведал ей свое истинное имя, а вместе с тем – и все тайны вселенной. Легенда гласит, что впоследствии Ра скрылся от богов, а его трон остался свободным на миллионы лет.

Кстати говоря, Исида сдержала обещание и излечила Ра от яда змеи. Интересный факт, обрывки ритуала, проведенного мудрой богиней, сохранился в истории и части его дошли до наших дней. Вот, что говорила Исида:

«Истекая, яд, выходи из Ра, Око Гора, выходи из Ра и засияй на его устах. Это заклинаю я, Исида, и это я заставила яд упасть на землю. Воистину имя великого бога взято у него, Ра будет жить, а яд умрёт; если же яд будет жить, то умрёт Ра».

Впоследствии, Исида, никогда не желавшая личной власти, передала знание своему сыну, Гору. Некоторые источники гласят, что Гор являлся перевоплощением самого Ра. По сути – так оно и было, ибо вместе с самым грозным оружием во вселенной (Оком Ра), таинствами мироздания и вселенной, и собственной мудростью – Гор ничуть не уступал Ра. А возможно, был даже более сильным и могучим.

Культ Исиды и его роль в мире

Рекомендуем по теме

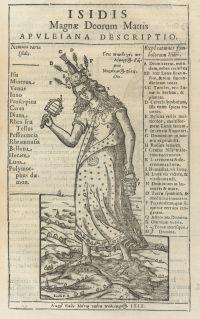

Культ Исиды – это второй, по значимости и распространенности культ древних времен, после культа Сераписа, о котором стало широко известно не только на просторах Древнего Египта, но и далеко за его пределами. Как мы уже сказали в самом начале нашей статьи, культ Исиды был широко известен в Древней Греции и Древнем Риме. Храм Исиды даже имелся в легендарных Помпеях, а саму Исиду отождествляли с греческими богами (в основном – с Реей, но есть источники, говорящие, что Исиду приравнивали с Афиной, Персефоной и Селеной).

Помимо этого, Исида была известна и в других европейских государствах. Ее таинства пользовались популярностью в Испании и Галлии, а также в Британии. Но история гласит, что чем дальше на запад – тем больше легенда теряла свое истинное значение. Т.е., образ матери богов, покровительницы семейного очага и покровительницы королевской власти за ней закрепился, но имя ее стерлось со страниц европейской истории.

Говорят, что Исида имеет непосредственное отношение к развитию христианства. Правда ли это?

Что касается именно развития – то это вряд ли, а вот что касается перенесшихся образов – это да. Исиду часто изображали, кормящей младенца, богоматерью. В те времена об Исиде знали во многих европейских государствах, но чем дальше на запад, тем больше забывали истинное значение легенды. Так Гор стал отождествляться с Иисусом, а Исида – с Девой Марией.

Интересный факт, культ Исиды в значительной степени повлиял и на развитие христианства. Как мы уже сказали ранее, богиню часто изображали в образе богоматери, кормящей младенца, но не многие знают, что последующий образ Иисуса пошел именно со времен Древнего Египта.

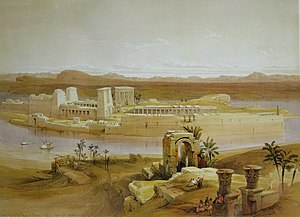

Исида – это чуть ли не единственное божество, храм которого существовал до самого крушения великой египетской цивилизации. А священный храм богини, на острове Филе, сумел пережить крах Египта и стоял даже после того, как Египет был христианизирован, т.е. уже в первых веках нашей эры.

Не затронули храм и приказы о запрете языческих культов. Но, к сожалению, военачальник Нарсес, по приказу византийского императора Юстиниана Первого, разрушил все центры языческой культуры, в число которых входил и храм Исиды. Реликвии храма, как гласит история, были доставлены в Константинополь. Однако многие храмы Исиды располагались по всей территории Древнего Египта, ибо значение Исиды в то время – было просто невероятным.

Пожалуй, на этом и заканчивается наша статья об одной из величайших богинь Древнего Египта. А закончить мы ее хотим интересным фактом, связанным непосредственно с нами, славянами. От имени Исиды происходит русское имя Сидор (Исида>Исидор (греч.)>Сидор). Дословно, имя означает «дар Исиды».

На этом мы с вами прощаемся, дорогие читатели. Всем удачи и до новых встреч.

Часто задаваемые вопросы

Почему на голове Исиды изображался то трон, то солнечный диск?

Почему Исида так долго искала гром с телом мужа?

История персонажа

Исида – честолюбивая богиня, основным долгом которой принято считать заботу о семье, никогда не забывала о собственной важности. Поэтому красавица приложила столько сил, чтобы вернуть трон собственному сыну, ведь быть матерью фараона гораздо почетнее, чем простой беглянкой. Впрочем, даже без блистательного Гора и верного Осириса Исида заняла важное место в египетском пантеоне богов. Покровительница женщин и плодородия знала, в чем именно нуждаются простые смертные.

История происхождения

Истоки культа богини лежат в небольшом городе Себеннит, располагавшемся в дельте Нила. До того, как занять место покровительницы фараонов, Исида почиталась в основном египетскими рыбаками. Местом поклонения богине считался город Буто.

Изначальный образ женщины заметно отличается от более поздних изображений красавицы. Исиду изображали с головой коровы, но распространение культа отразилось на внешности женщины. Когда влияние жены Осириса расширилось на весь Древний Египет, непривлекательную морду коровы заменили красивым лицом. О предыдущем образе напоминали только оставшиеся на прежнем месте рога.

Богиня постепенно обзаводилась родственниками, а также собственными мифами и легендами. С приходом Древнего Царства Исида обрела статус жены и помощницы божественного фараона. И если ранее красивую женщину воспринимали как покровительницу неба, теперь за Исидой закрепилась обязанность управлять ветром. С этого момента богиню изображали крылатой девой.

Слияние с культом Осириса обеспечило женщину большим влиянием и большим количеством обязанностей. Теперь Исиду воспринимали как защитницу мертвых, покровительницу беременных и символ верности, женственности и материнской любви.

Богиню стали изображать с распущенными волосами. Женщину одевали в серебристое платье, в руках богиня часто держала ведро (разлив Нила) и музыкальный инструмент систр. Нередко статую красавицы оборачивали плащом, подол которого расшивали цветами. Это служило напоминанием, что Исида – знаток лечебных трав и отваров.

К моменту образования Нового Царства Исида стала известна в Египте больше собственного супруга. Культ богини распространился на территорию Греции, где изначально был переименован в культ Деметры. Но позже женщина получила известность под собственным именем. Правда, основное значение богиня потеряла, приобретя при этом эротический символизм.

Во 2 веке до нашей эры имя Исиды зазвучало на территории Древнего Рима. В честь богини воздвигли храмы в Помпеях и Беневенте. Оттуда культ распространился на Европу и Азию. Исследователи утверждают, что некоторые элементы поклонения египетскому божеству нашли отражение и в христианстве.

Мифы и легенды об Исиде

Исида – старший ребенок бога земли Геба и богини неба Нут. Вскоре после рождения девушки у четы появились еще наследники: Осирис, Сет и Нефтида. После того, как Осириса провозгласили фараоном Египта, богиня вышла замуж за младшего брата.

Брак, который окружающие считали политическим, был построен на любви и взаимоуважении. Поэтому, когда злобный Сет убил Осириса, женщина направила все силы на возвращение любимого.

Страдающая вдова долго искала тело возлюбленного и случайно обнаружила гроб с Осирисом в проросшем на берегу Нила дереве. Исида обернулась коршуном, обняла тело погибшего мужа и, произнеся заклинание, воскресила Осириса. Увы, магии хватило лишь на то, чтобы предаться с богом любви. После этого Осирис вернулся в мир мертвых, а Исида осталась одна с новорожденным младенцем Гором на руках.

Изгнанная жена фараона бдительно опекала сына и всячески старалась вернуть законному наследнику трон Египта. Когда Гор стал достаточно взрослым, Исида созвала совет богов и потребовала справедливости. Зная, что правда не на его стороне, Сет настоял, чтобы Исиду не пускали на совет.

Женщина с помощью магии превратилась в старуху и, обманув стражей, направилась в покои фараона-захватчика. Перед тем, как войти к младшему брату, богиня приняла облик незнакомой красавицы. Сет, который всегда обращал внимание на привлекательных женщин, не устоял и на этот раз.

Мужчина попытался овладеть незнакомкой, но переодетая богиня попросила сначала выслушать грустный рассказ. Исида рассказала, что вышла замуж за пастуха, которого убили. И пришедший чужеземец захватил скот мужа, лишив сына пастуха наследства. Ослепленный Сет вскрикнул, что чужеземца надо покарать и вернуть стадо наследнику. В эту же минуту Исида вновь стала собой.

Впрочем, даже подобное признание не приблизило Исиду и Гора к трону. Предстояло еще пройти ряд испытаний. Мать, которая желала помочь любимому сыну, метнула во время поединка богов гарпун в Сета. Младший брат упросил сестру освободить его. Несмотря на ненависть к тирану, Исида сжалилась над убийцей мужа. Увидев, что богиня освободила Сета, разгневанный Гор сгоряча отрубил голову матери.

Конечно, великая покровительница мертвых не погибла. Голова тут же приросла к шее обратно. Любящая мать даже не разозлилась на сына и простила гордого юношу за пылкий порыв.

Добившись справедливости для сына, богиня захотела возвысить собственное имя среди богов. Чтобы получить больше влияния, Исида решила узнать тайное имя бога Ра. Подобное знание обеспечило бы женщину влиянием и могуществом.

Заметив, что Ра уже стар и болен, богиня стала собирать капающую слюну покровителя солнца. Смешав жидкость с пылью, Исида создала змею, которая укусила бога. Ра, страдающий от сильной боли, призвал богов. На мольбы о помощи откликнулась и Исида. Женщина пообещала вылечить бога, если тот скажет богине собственное тайное имя. Старик подчинился, а Исида получила статус хозяйки богов.

Интересные факты

- Буквальное значение имени богини – «трон», но египтяне переводили «Исида» как «та, что стоит у трона».

- Символ возлюбленной Осириса – фараонский трон, которым богиня украшала голову. Вторым по значимости амулетом Исиды считается тиет, или «узел Исиды». Подобным рисунком украшали саркофаги и одежду фараонов.

- Древние египтяне верили, что разлив Нила связан с божеством: река выходит из берегов из-за слез, которые проливает Исида по потерянному мужу.

Исида была одной из самых значимых богинь для древних египтян. Она воплощала силы плодородия, владела магией и могла совершать невозможное. Да что говорить – Исиде по силам было даже воскрешение умерших! В то же время она служила примером преданности и бесконечной любви к супругу, что делало богиню защитницей женщин.

Немногие божества могут состязаться с Исидой по своей популярности – её имя часто фигурирует в древних текстах, документах, описаниях обрядов и даже заклинаниях. Своей покровительницей её избирали царицы Египта, которые считали себя воплощением богини. На какие чудеса была способна Исида? И как сила её любви смогла одержать победу над самой смертью?

Исида – воплощение любви и материнства

Исида превратилась из малоизвестного божества в богиню, которой больше всего поклонялись в Египте

Исида была одной из самых почитаемых божеств в древнем Египте. Ее имя является греческой коррупцией в качестве египетского имени и буквально означает Королеву Трона. В египетской мифологии главной эннеадой (группой из девяти) была великая эннеада Гелиополиса. Она состоит из девяти основных египетских божеств, возглавляемых богом солнца и создателем Ра или Ра-Атум; затем следовали Шу и Тефнут, божества воздуха и влаги; Геб и Нут, которые представляли землю и небо и дети Геба и Нута: Осирис, Исида, Сиф и Нефтис. Исида, как и ее муж-брат Осирис, не были четко упомянуты в Древнем Египте до пятой династии (ок. 2494 — 2345 до н.э.). Таким образом, изначально Исида была малоизвестной богиней, которой не хватало посвященных храмов. Однако, по мере развития династического возраста ее значение возрастало, пока она не стала одним из важнейших божеств Древнего Египта. В первом тысячелетии до нашей эры Исида, наряду с Осирисом, стала наиболее широко поклоняющимся египетским божествам. Ее культ впоследствии распространился по всей Римской империи; в то время ей поклонялись от Англии до Афганистана. До сих пор есть еще люди, которые продолжают поклоняться Исиде.

Иконография

Богиня жизни и здоровья в древнегреческой мифологии часто отождествляется с коровой, между рогов которой заключено солнце, а также представляется как ястреб или женщина с крыльями, символизирующими ветер. В крылатом виде ее можно увидеть на крышках саркофагов.

Изображение представляет акт принятия душой новой жизни. На других иконах она предстает в виде одетой женщины, держащей в руках цветок лотоса — символ плодородия и власти, а также женщиной, кормящей грудью новорожденного сына. Иногда символом богини вечной жизни Исиды является египетский узел ору. Точное значение этой детали одежды неизвестно, но есть предположение, что оно отождествляет бессмертие.

Её происхождение можно проследить до знаменитого мифа об Осирисе

Происхождение Исиды можно отнести к мифу об Осирисе Древнего царства (с 2686. до н.э. — 2181 г. до н.э.) Древнего Египта. Миф об Осирисе является наиболее важной, а также знаменитой историей в древнеегипетской мифологии. Согласно мифу Осирис и его сестра — жена Исида были правителями мира после его создания. Мужчины и женщины были изначально крайне нецивилизованными. Однако благодаря дарам Исиды и учениям Осириса, они обучились искусству земледелия, культуры и способу жить цивилизованной жизнью. Однако Сет, брат Осириса, стал завидовать силе и престижу Осириса и готовился убить его, чтобы захватить трон. Он обманом заставил Осириса лечь в гроб, запер его и бросил в реку Нил. Когда Исида узнала об этом, она решила найти гроб, чтобы вернуть ее мужа к жизни. Тем временем гроб застрял на дереве, которое захватил Малкандер, король Библоса. В Библосе Исида встретила Астарту, жену Малкандера, и осталась во дворце под видом старой женщины. Когда Малкандеру и Астарте открылась истинная форма богини, они умоляли ее о милости и предложили ей все, что она хотела. Изида взяла дерево, в котором застрял ее муж, и попыталась найти способ освободить и оживить Осириса. Она срубила дерево и забрала тело Осириса обратно в Египет, спрятав его в дельтах Нила. Исида пошла собрать траву, которая могла бы помочь оживить ее мужа, Сет узнал об этом плане. Тогда он разрезал тело Осириса на части и бросил их по всей земле и в реку Нил.

Великий Ра и Исида: миф

В древних текстах об Исиде говорится, что у нее сердце более непокорное, чем у всех людей, и более умное, чем у всех богов. Исида считалась людьми колдуньей. Она опробовала свои умения на богах.

Так, с неукротимым желанием богиня хотела познать тайное имя бога Ра, сотворившего мир, а также небо и свет. Это дало бы ей власть над самым могущественным богом, а впоследствии — и над всеми богами. Для того чтобы узнать секрет главы пантеона богов Египта, богиня Исида применила хитрость. Она знала, что Ра стар и что когда он почивает, то с уголков его губ течет слюна и каплет под ноги.

Она соскребла эти капельки, перемешала их с дорожной пылью и вылепила змею. При помощи своих заклятий оживила и подбросила ее на дорогу, по которой должен был проходить Ра. Через некоторое время верховный бог был укушен змеей. Испугавшись, он кликнул на помощь детей и объяснил им, что его укусило что-то неизвестное, и сердце его трепещет, а члены исполнены холодом.

Исида, покорная его воле, тоже пришла к отцу и произнесла: «Открой мне имя свое, отец, ведь останется жить тот, чье имя будет упомянуто в заклинании!» Ра пришел в смятение — он знал об этом, но боялся. Он, притворяясь, что уступил дочери, зачитывал перечень случайных имен. Но Исиду не провести, и она настояла, чтобы отец произнес свое настоящее имя.

Ра, не в силах перенести жуткую боль, посвятил ее в ужасную тайну. После чего был исцелен дочерью. Интересно, что ни в одном из текстов, известных в настоящее время, это имя не было указано. В христианстве имя Бога также не знает никто.

Её называли Богородицей

Исида искала части тела своего мужа, чтобы положить их вместе. Ей удалось найти все части, кроме его члена, который был брошен в реку, а затем съеден рыбой. Тем не менее она была в состоянии оживить своего мужа, соединив части его тела вместе. Воскресив Осириса из мертвых, Исида поняла, что без пениса она и Осирис не смогут иметь ребенка. Несмотря на то, что Осирис был теперь жив, он не мог управлять землей живых, так как считался незавершенным. Он был отправлен в загробную жизнь, где принял положение Повелителя подземного мира. Однако, до этого Исида превратилась в воздушного змея, чтобы втянуть в тело семя Осириса. Она пролетела над Осирисом и успешно смогла зачать ребенка Гора. Из-за этого ее часто называют Девственницей-матерью. История чудесного рождения Гора может быть связана с подобными мифами в других религиях. Кроме того, «Исиду считают прообразом Богородицы».

Символика

В ритуалах празднования Дня плодородия во время шествия перед изображением бога Осириса устанавливали горшок или кубок, до краев наполненный водой. Этот символ обозначал вечную и неизменную смену поколений. Также в примитивных обрядах можно было увидеть факел, обозначающий мужчину, и чашу, символизирующую женщину, как ритуал зачатия наследника Осириса и Исиды.

- Животными, представляющими греческую богиню жизни, являлись ястреб, скорпион, крокодил, змей.

- Растения: тамаринд, лен, пшеница, ячмень, виноград, лотос.

- Металлы и камни: серебро, золото, черное дерево, слоновая кость, лазурит, обсидиан.

- Цвета Исиды: серебро, золото, черный, красный, синий и зеленый.

Исида столкнулась с трудными обстоятельствами, воспитывая сына

Забеременев, Исида спряталась в болотах дельты реки Нил, чтобы защитить себя и своего сына Гора от Сета. У нее была тяжелая беременность, большая часть которой была потрачена на сокрытие от Сета и его демонов. Исида родила Гора в болотах Дельты, где она пребывала одна. Исиде и ее сыну была предложена защита от Сета богинями Селкет и Нейт. Таким образом, Гора воспитывали и обучали три богини. Когда Гор стал взрослым и достаточно сильным, чтобы победить своего дядю Сета, он стал претендовать на престол Египта. Совет богов отвечал за разрешение конфликта между Сетом и Гором. В то время как большинство богов выбрали Гора в качестве преемника престола своего отца; Ра, Верховный Бог, поддерживал Сета, потому что он был старше и, следовательно, мудрее и опытнее. В связи с этим конфликт продолжался более 80 лет. Гору и Сету пришлось пройти через ряд сражений, чтобы доказать свою компетентность на трон. Несмотря на то, что все битвы выигрывал Гор, продолжал отказывать ему в его законном положении. В конечном итоге Гор все же становится правителем Египта.

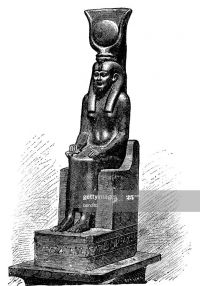

Исиде поклонялись как богине-матери

Огласно некоторым ранним мифам, Хатхор мать Гора. Однако, поскольку миф Осириса стал самым влиятельным из египетских мифов, Исида стала считаться матерью Гора. В связи с этим отношения Исиды с ее сыном Гором идеализировались как воплощение отношений матери и сына в древнеегипетском правлении. В мифе Осириса Исида приносит многочисленные жертвы Гору и предлагает ему защиту, когда он еще младенец. Мало того, она помогает своему сыну на протяжении всей его жизни и помогает ему вернуть трон Египта .Из-за Мифа Осириса Исида стала рассматриваться как воплощение материнской преданности, и это, в свою очередь, привело к тому, что она стала матерью-богиней. В Древнем Египте ко времени Нового царства (16 век до н.э. — 11 век до н.э.) Исида считалась матерью фараона. Таким образом, она часто изображается кормящей грудью фараона в скульптурах той эпохи.

Кто она такая?

Исет, Изида, или Исида — жена Осириса, бога загробного мира и возрождения. Она является матерью Гора, покровителя солнца и небес. Ее имя принято переводить как «имеющая тысячу имен». Если следовать фактическому переводу с древнего языка, то «исет» — слово, означающее «царский трон» или «престол». Такое имя, скорее всего, обусловлено тем, что носительница его была наделена большой властью. «Богиня Исида — богиня чего?» — спросите вы. Ей в древности поклонялись как покровительнице прекрасного пола, детства и материнства, женщин во время родов и в период беременности, а также плодородия, ветра, воды и, естественно, магии. Мистика и магия вообще тесно связаны с богиней Исидой. Ритуальные обряды активно пропагандировали жрицы ее культа.

В других культурах можно найти аналогичные культы, в которых в роли Исиды выступали Рея или Иштар. В Древнем Риме и Древней Греции также существовали собрания почитающих ее. Нефтис является сестрой этой богини. Это «владычица дома», правая рука и помощница Исиды, которая отвечает за ведение хозяйства и домашний очаг.

Как супруга Осириса, эта богиня иногда перенимает его функции. Так, например, согласно Диодору Сицилийскому, Исида научила смертных выращивать зерна и жать их. Эту богиню греки отождествляли с Деметрой, своей богиней-матерью. Чаще всего, однако, функции земледельца приходилось исполнять самому Осирису. Также вместе с легендами о том, что Нил вытекает из чрева этого бога, имелось и представление, что он разливается от слез его супруги, которая тоскует по своему мужу. Богиня Исида, по традициям античности, властвовала над реками и морями, являлась покровительницей моряков.

Она изображалась как сострадательная и прощающая богиня

В Египетской мифологии, Исида изображается как сострадающая и всепрощающая. Самая известная история о ее прощении описана как Исида и Семь Скорпионов. Эта история используется, чтобы изобразить доброту, проявленную Исидой, даже к тем, кто не был добр к ней. Когда Гор был молод и Исида находилась в укрытиях, чтобы защитить своего сына от Сета, она в сопровождении семи скорпионов вышла, чтобы собрать пищу и воду. Эти скорпионы были ее телохранителями, трое из которых двигались перед ней, двое по обе стороны от нее и двое следовали за ней, чтобы защитить ее со всех сторон. Исида, покидая болото, скрывала свою божественную славу и становилась бедной и старой женщиной. В итоге однажды, богатая дворянка взглянула на нее сверху вниз и отказала ей в пище и крове. Взбешенные скорпионы ужалили младшего сына дворянки и она побежала на улицу с просьбой о помощи, чтобы оживить сына. Услышав крик женщины, Исида вышла помочь ей. Она взяла ребенка на руки и доминировала над силой скорпионов, называя их тайными именами. Это полностью изменило силу укуса, и мальчик был спасен. Данная история, где она помогает женщине, которая отнеслась к ней не по доброму является одним из многих примеров сострадательной природы Исиды.

Сходство образа Исиды с образом реальной мирской женщины

Очень близок мифологический образ Исиды к реальной мирской женщине. В малоизвестной истории о ней рассказывается о печали и горьких страданиях, которые переживала богиня Исида (фото ее порой так печальны). Она жалуется на одиночество, причитает, а все из-за того, что простая смертная женщина не приняла ее на пороге дома. За это неуважение она расплатилась здоровьем своего сына, которого ужалил скорпион. В этой драме, впрочем, нельзя отказать Исиде в милосердии. Она все-таки спасла сына нерадивой хозяйки.

Исида сама является трепетной матерью. Это подтверждается во многих легендах. В одной из них, например, она приходит в исступление, видя своего умирающего сына. Страдания этой богини смогли остановить даже мировую ладью верховного бога Ра, в которой тот проплывал по небу.

Исида взяла на себя ряд ролей в Египетской мифологии

Будучи частью Богини-Матери, Исида взяла на себя ряд других ролей. В верованиях загробной жизни в Древнем Египте она помогала восстановить души умерших людей, как она это сделала для Осириса. Она приветствовала умершего в загробной жизни как мать, обеспечивая защиту и питание. Египетский фараон был проявлением Гора в жизни и Осириса в смерти. Поэтому Исида являлась мифологической матерью и женой фараонов. Исида была также связана с магическими силами, которые позволили ей оживить Осириса и защитить и исцелить Гора. Благодаря ее магическому знанию, она, как говорили, была «более умной, чем миллион богов». Есть также многочисленные мифы, которые показывают ее хитрость в решении ситуаций. Среди прочего, она использовала свое остроумие, чтобы перехитрить Сета во время его конфликта с сыном. Исида также была связана с потопом, который иногда приравнивали к слезам, которые она пролила над Осирисом. Кроме того, Исида была замечена как космическая богиня с различными текстами, утверждающими, что она организовала поведение солнца, луны и звезд; время и времена года, которые, в свою очередь, гарантировали плодородие земли. Символом Исиды на небесах был Сириус, самая яркая звезда в ночном небе, означающая богатство и процветание в Древнем Египете.

Символы Исиды

Главный символ описываемой богини — это царский трон. Его знак довольно часто располагается на ее голове. Священным животным Исиды почиталась великая белая корова Гелиополя, которая была матерью священного Аписа.

Широко распространенным символом Исиды считается амулет Тет, носящий название «узел Исиды». Он изготавливается из красных минералов – яшмы и сердолика.

Небесный символ богини – это Сириус. С восходом этой звезды от слез богини, оплакивающей любимого мужа, разливается Нил.

Вместе со своей сестрой она представляла космический баланс мира

К первому тысячелетию до н.э. Исида была одним из самых почитаемых божеств в Египте и она постепенно впитала черты многих других богинь. Как одну из тех, кто мог затопить Нил, ее звали Сати. Как та, которая наполнила земли своими водами и сделала их плодородными, она называлась Ангет. Как богиня возделываемых земель и полей, она была Сехет. Как богиня урожая, она была Рененет. Как связанная с перерождением, она была связана с Фениксом. Как даритель жизни, она была Анхетом. Концепция баланса в Египте было также изображение Исиды и ее сестры — близнеца Богини Нефтиды. Исида представляла свет, а Нефтида представляла темноту. Точно так же Исида представляла жизнь, а Нефтида — смерть. Однако, это не значит, что Нефтида воспринималась как зло. Вместо этого сестры представляли космический баланс между двумя противоположными концами спектра.

Храм Исиды был раскопон во время раскопок Помпеи

Исида считалась мощной богиней всего древнего Египта. В ее честь построены различные храмы и места поклонения. Первый большой храм для поклонения Исиде был построен вблизи дельты Нила, на Бехмейт эль-Хагаре. В более ранних святилищах Исиде, возможно, поклонялись вместе с Осирисом и Гором. Другой храм, посвященный Исиде расположен на Острове из Филае. Храм на Филае был построен в период царствования Нектанеб I ( 380 г. до н.э. — 362 г. до н.э.) и он стал одним из самых важных храмов в древнем Египте. Более того, многие считают , что Храм Исиды на Филае является последним из древних храмов, построенных в «классическом» египетском стиле. Знаменитый храм Исиды можно увидеть в Помпеях, древнем римском городе, который был разрушен извержением вулкана; и таким образом частично сохранился. Храм Исиды был одним из первых открытий во время раскопок Помпеи в 1764 году. Хорошо сохранившийся и почти неповрежденный, храм служил источником вдохновения для многих художников всего мира. Известно, что в 1769 году известный композитор Вольфганг Амадей Моцарт посетил Храм Исиды в Помпеях.

Имя Исиды в иероглифах

сида (Изида) (егип. js.t, др.-греч. Ἶσις, лат. Isis) — одна из величайших богинь древности, ставшая образцом для понимания египетского идеала женственности и материнства. Она почиталась как сестра и супруга Осириса, мать Гора, а, соответственно, и египетских царей, которые исконно считались земными воплощениями сокологолового бога.

Истоки культа

Будучи очень древним, культ Исиды, вероятно, происходит из Дельты Нила. Здесь находился один из древнейших культовых центров богини, Хебет, названный греками Исейоном (совр. Бехбейт эль-Хагар), лежащий в настоящее время в руинах. Вероятно, изначально она была локальным божеством Себеннита, но уже «Тексты пирамид» периода V династии указывают на ключевую роль этой богини в общеегипетском пантеоне. Изначально ассоциируясь с богом Гором, вследствие подъёма народного культа Осириса Исида выступает уже сестрой и женой Осириса и матерью Гора. Её первоначальные черты в период Нового царства переносятся на Хатор. В Гелиопольской теологической системе Исида, младшее божество эннеады, почиталась как дочь бога Геба и богини Нут, соответственно, как правнучка Ра.

Миф об Осирисе и Исиде

В мифах, часть которых дошла до нашего времени только в известном пересказе Плутарха («Об Исиде и Осирисе»), богиня хорошо известна как верная супруга Осириса, тело которого она нашла в долгих странствиях после того, как бога убил его родной брат Сет. Собрав воедино разрубленные на части останки Осириса, Исида с помощью бога Анубиса сделала из них первую мумию. Исида вылепила фаллос из глины (единственной частью тела Осириса, которую Исида так и не смогла найти, был фаллос: его съели рыбы), освятила его и прирастила к собранному телу Осириса. Превратившись в самку коршуна — птицу Хат, Исида распластала крылья по мумии Осириса, произнесла волшебные слова и забеременела. В храме Хатхор в Дендере и храме Осириса в Абидосе сохранились рельефные композиции, на которых показан сокровенный акт зачатия сына богиней в образе соколицы, распростёртой над мумией супруга. В память об этом Исида часто изображалась в облике прекрасной женщины с птичьими крыльями, которыми она защищает Осириса, царя или просто умершего. Исида часто предстает и коленопреклоненной, в белой повязке афнет, оплакивающая каждого усопшего так, как когда-то оплакивала самого Осириса.

Согласно легенде, Осирис стал владыкой загробного мира, в то время как Исида родила Гора в тростниковом гнезде в болотах Хеммиса (Дельта). Многочисленные статуи и рельефы изображают богиню кормящей грудью сына, принявшего облик фараона. Вместе с богинями Нут, Тефнут и Нефтидой, Исида, носящая эпитет «Прекрасная», присутствует при родах каждого фараона, помогая царице-матери разрешиться от бремени. Исида — «великая чарами, первая среди богов», повелительница заклинаний и тайных молитв; её призывают в беде, произносят её имя для защиты детей и семьи. По преданию, для того, чтобы завладеть тайным знанием и обрести магическую силу, богиня вылепила из слюны стареющего бога Ра и земли зме́я, ужалившего солнечное божество. В обмен на исцеление Исида потребовала у Ра поведать ей свое тайное имя, ключ ко всем загадочным силам вселенной, и стала «госпожой богов, той, кто знает Ра в его собственном имени».

Своим знанием Исида, одна из божеств-покровителей медицины, исцелила младенца Гора, ужаленного в болотах скорпионами. С тех пор, подобно богине Селкет, она иногда почиталась как великая владычица скорпионов. Свои тайные силы богиня передала Гору, тем самым вооружив его великой магической силой. С помощью хитрости Исида помогла Гору одержать верх над Сетом во время спора за престол и наследство Осириса и стать владыкой Египта.

Миф о Ра и Исиде

Исида, прослыв среди людей колдуньей, решила испытать свои силы и на богах. Для того чтобы стать госпожой небес, она решила узнать тайное имя Ра. Она заметила, что Ра к тому времени стал стар, с уголков его губ капает слюна и падает на землю. Она собрала капли слюны Ра, смешала её с пылью, слепила из неё змею, произнесла над ней свои заклинания и положила на дороге по которой ежедневно проходил солнечный бог. Спустя некоторое время змея укусила Ра, он страшно закричал, и все боги бросились к нему на помощь. Ра сказал, что несмотря на все его заклинания и его тайное имя, его укусила змея. Исида пообещала ему, что исцелит его, но он должен сказать своё тайное имя. Бог солнца сказал, что он Хепри утром, Ра в полдень и Атум вечером, но это не удовлетворило Исиду. И тогда Ра сказал: «Пусть Исида поищет во мне, и моё имя перейдёт из моего тела в её». После этого Ра скрылся от взора богов на своей ладье, и трон в Ладье Владыки Миллионов Лет стал свободен. Исида договорилась с Гором, что Ра должен поклясться в том, что расстанется со своими двумя Очами (Солнцем и Луной). Когда Ра согласился с тем, чтобы его тайное имя стало достоянием колдуньи, а его сердце вынуто из груди, Исида сказала: «Истекая, яд, выходи из Ра, Око Гора, выходи из Ра и засияй на его устах. Это заклинаю я, Исида, и это я заставила яд упасть на землю. Воистину имя великого бога взято у него, Ра будет жить, а яд умрёт; если же яд будет жить, то умрёт Ра».

Символы

Символом Исиды был царский трон, знак которого часто помещается на голове богини. С эпохи Нового царства культ богини стал тесно переплетаться с культом Хатхор, в результате чего Исида иногда имеет убор в виде солнечного диска, обрамленного рогами коровы. Священным животным Исиды как богини-матери считалась «великая белая корова Гелиополя» — мать мемфисского быка Аписа.

Одним из широко распространенных символов богини является амулет тет — «узел Исиды», или «кровь Исиды», часто выполнявшийся из минералов красного цвета — сердолика и яшмы. Как и Хатхор, Исида повелевает золотом, считавшимся образцом нетленности; на знаке этого металла она часто изображается коленопреклоненной. Небесные проявления Исиды — это, прежде всего, звезда Сепедет, или Сириус, «госпожа звезд», с восходом которой от одной слезы богини разливается Нил; а также грозная гиппопотам Исида Хесамут (Исида, мать грозная) в облике созвездия Большой медведицы хранящая в небесах ногу расчлененного Сетха с помощью своих спутников — крокодилов. Также Исида вместе с Нефтидой может представать в облике газелей, хранящих горизонт небес; эмблему в виде двух газелей-богинь носили на диадемах младшие супруги фараона в эпоху Нового царства. Ещё одно воплощение Исиды — богиня Шентаит, предстающая в облике коровы покровительница погребальных пелен и ткачества, повелительница священного саркофага, в котором возрождается, согласно осирическому ритуалу мистерий, тело убитого братом Осириса. Сторона света, которой повелевает богиня — запад, ее ритуальные предметы — систр и священный сосуд для молока — ситула. Вместе с Нефтидой, Нейт и Селкет, Исида была великой покровительницей умершего, своими божественными крыльями защищала западную часть саркофагов, повелевала антропоморфным духом Имсети, одним из четырёх «сыновей Гора», покровителей каноп.

Центры почитания

Знаменитое святилище Исиды, существовавшее вплоть до исчезновения древнеегипетской цивилизации, находится на острове Филе, неподалеку от Асуана. Здесь богине, почитавшейся во многих других храмах Нубии, поклонялись вплоть до VI века н. э., в то время, когда весь остальной Египет уже был христианизирован. Святилище Исиды и Осириса на Филе оставалось вне зоны действия эдикта императора Феодосия I о запрете языческих культов 391 года в силу соглашения, достигнутого ещё Диоклетианом с правителями Нобатии, посещавшими храм в Филе как оракул. Наконец, византийский император Юстиниан I отправил военачальника Нарсеса разрушить культовые сооружения на острове и доставить их реликвии в Константинополь.

Другие центры почитания богини располагались по всему Египту; наиболее известные из них — это Коптос, где Исида считалась супругой бога Мина, владыки восточной пустыни; Дендера, где богиня неба Нут родила Исиду, и, конечно же, Абидос, в священную триаду которого богиня входила вместе с Осирисом и Гором.

Гностический гимн, связываемый некоторыми исследователями с Исидой

Да не будет не знающего меня нигде и никогда! Берегитесь, не будьте не знающими меня! Ибо я первая и последняя. Я почитаемая и презираемая. Я блудница и святая. Я жена и дева. Я мать и дочь. Я члены тела моей матери. Я неплодность, и есть множество ее сыновей. Я та, чьих браков множество, и я не была в замужестве. Я облегчающая роды и та, что не рожала. Я утешение в моих родовых муках. Я новобрачная и новобрачный. И мой муж тот, кто породил меня. Я мать моего отца и сестра моего мужа, и он мой отпрыск.

(Гром. Совершенный Ум. Гимн из библиотеки Наг-Хаммади, I—III вв. н. э.)

Исида в античной традиции

Богиня была хорошо известна грекам и римлянам. Жена Осириса. Её отождествляли с Деметрой. Изобрела паруса, когда искала своего сына Гарпократа (Гора).

Отождествляется с Ио, дочерью Инаха, египтяне так назвали Ио.

Некоторые считают, что она стала созвездием Девы. Поместила Сириус на голову Пса. Рыба, которая ей помогла, стала созвездием Южной Рыбы, а её сыновья — Рыбами.

В знаменитом произведении античного автора Апулея «Метаморфозы» описываются церемонии инициации в служители богини, хотя их полное символическое содержание так и остаётся загадкой.

Культ Исиды и связанные с ним мистерии приобрели значительное распространение в греко-римском мире, сравнимое с христианством и митраизмом. Как вселенская богиня-мать, Исида пользовалась широкой популярностью в эпоху эллинизма не только в Египте, где её культ и таинства процветали в Александрии, но и во всем Средиземноморье. Хорошо известны её храмы (лат. Iseum) в Библе, Афинах, Риме; неплохо сохранился храм, обнаруженный в Помпеях. Алебастровая статуя Исиды III века до н. э., обнаруженная в Охриде, изображена на македонской банкноте достоинством в 10 денаров. В позднеантичную эпоху святилища и мистерии Исиды были широко распространены и в других городах Римской империи, среди которых выделялся храм в Лютеции (совр. Париж). В римское время Исида намного превзошла своей популярностью культ Осириса и стала серьёзной соперницей становления раннего христианства. Калигула, Веспасиан и Тит Флавий Веспасиан делали щедрые подношения святилищу Исиды в Риме. На одном из изображений на триумфальной арке Траяна в Риме император показан жертвующим вино Исиде и Гору. Император Галерий считал Исиду своей покровительницей.

Отдельные авторы XIX—XX веков усматривали в почитании «Чёрных Мадонн» в христианских храмах средневековой Франции и Германии отголоски культа Исиды. Также встречалось мнение об иконографическом влиянии образа Исиды с младенцем Гором-Гармахисом на изображение Богородицы с младенцем Иисусом, а также параллели между мотивом бегства Святого семейства в Египет от преследований Ирода и сюжетом о том, как Исида спрятала юного Гора в тростниках, опасаясь гнева Сета.

По мнению известного этнографа и религиоведа Джеймса Фрэзера, элементы культа Исиды оказали значительное влияние на христианскую обрядность:

Величественный ритуал Исиды — эти жрецы с тонзурами, заутренние и вечерние службы, колокольный звон, крещение, окропление святой водой, торжественные шествия и ювелирные изображения Божьей Матери <�…> — во многих отношениях напоминает пышную обрядовость католицизма.

Однако ряд сходств, упоминаемых Фрэзером, является спорным. Например, Фрэзер упоминает тонзуры жрецов Исиды, хотя, согласно Плутарху, жрецы Исиды полностью удаляли волосы на голове и теле.

Источники

- Сайт «Wikipedia — Свободная Энциклопедия»

Культ Исиды возможно повлиял на Христианство

Поклонники Исиды иногда назывались «Исаакиями» и состояли из людей, принадлежащих низшим социальным классам. Представительство женщин в культе поклонения Исиде было гораздо более значительным по сравнению с культами любых других божеств. Культ Исиды предоставил женщинам пространство, в котором они могли действовать вне контроля границ, установленных принципами и культурами того времени. Когда Римская империя стала господствовать в христианстве, некоторые из практик, которым следовали Исаакиями, могли быть преобразованы в христианские традиции. Большое внимание уделяется изучению традиций в христианстве,которые, казалось бы, были переняты из других таинственных языческих культов, таких как культ Исиды. Были отмечены некоторые сходства между культом Исиды и христианством, включая концепцию загробной жизни, обрядов посвящения, крещения, смерти и воскрешения. Сходство между матерью Иисуса, Марией и Исидой было в центре дискуссии. Тем не менее, влияние египетской религии на христианство все же спорно.

Исида была одной из самых значимых богинь для древних египтян. Она воплощала силы плодородия, владела магией и могла совершать невозможное. Да что говорить – Исиде по силам было даже воскрешение умерших! В то же время она служила примером преданности и бесконечной любви к супругу, что делало богиню защитницей женщин.

Немногие божества могут состязаться с Исидой по своей популярности – её имя часто фигурирует в древних текстах, документах, описаниях обрядов и даже заклинаниях. Своей покровительницей её избирали царицы Египта, которые считали себя воплощением богини. На какие чудеса была способна Исида? И как сила её любви смогла одержать победу над самой смертью?

Исида – первая в божественной четвёрке

В мифологии Древнего Египта была два верховных божества, отождествлявшиеся с небом и землёй, Нут и Геб. Первая была богиней небесных светил и всего небосвода, а Геб стал её супругой, с которым её разделял весь мир, находящийся между двумя мирами. Именно у этой могущественной пары родилась Исида, которая стала первым ребёнком неба и земли.

Братом-близнецом, а позднее и мужем Исиды стал Осирис, другими родственниками были сестра Нефтида и брат Сет. Мне не раз приходилось замечать, что в древнеегипетских мифах наиболее важные события связаны с этой четвёркой богов. несмотря на родственные связи и достаточно добрый нрав твоих из них, из-за Сета отношения сестёр и братьев оказались сложными.

Когда пришла пора создавать священный союз, Исиа стала супругой Осириса, Нефтида – Сета. Не стоит удивляться таким близкородственным бракам – в древнем Египте они были запрещены простым людям, однако боги и фараоны были вынуждены сохранять чистоту своей крови, из-за чего часто создавали семьи с родными братьями или сёстрами.

Несчастье богини

Несмотря на то, что Исида была образцом верности и любви к мужу, Осирис не отличался такими же качествами. В тот миг, когда он изменил своей жене с сестрой Нефтидой, богиней потустороннего мира, оскорблённая Исида издала крик отчаяния.

Вскоре она нашла в камышовых зарослях маленького Анубиса. Это был ребёнок Нефтиды от Осириса, однако мать выбросила его, боясь, что о её измене узнает грозный Сет. Надо отдать должное Исиде, она взяла племянника на воспитание, а подросший Анубис стал покровителем мёртвых и их проводником в иной мир. На мой взгляд, в Исиде воплощён некий женский и материнский идеал того времени, который, впрочем, актуален и сегодня.

Несмотря на ухищрения своей супруги, Сету стало известно о предательстве Осириса. Кроме того, он и сам был страстно влюблён в Исиду, которая не замечала никого, кроме своего мужа.

Коварством Сет вынудил царя богов Осириса лечь в чудесный саркофаг. Тут же брат захлопнул его крышку и бросил гроб в Нил. Исида, которая была с рождения наделена чарами, поняла, что её возлюбленный в беде. Отвергнув Сета, который теперь занял трон Осириса, она отправилась на долгие поиски.

Найдя мёртвого Осириса в нильской затоке, она вытащила саркофаг на землю. Исида превосходно владела магией, а потому могла воскресить супруга. Здесь хочу заметить, что изначально богиня была покровительницей волшебных сил и всевозможных магических ритуалов, а лишь со временем её функции расширились – она стала повелевать воздухом и влагой, плодородием и жизненной энергией.

Исида – великая волшебница

Тем не менее, даже мудрой Исиде требовались определённые вещества и снадобья для проведения ритуала. Когда она отправилась за ними, Сет вышел на берег в облике леопарда. Он разорвал тело несчастного Осириса на множество частей. Теперь его брат не мог возродиться. Когда Исида вернулась, она поняла, что случилось непоправимое, однако не потеряла мужества даже в такой ситуации.

С помощью своего воспитанника Анубиса богиня стала искать по всему миру части тела мужа. Там, где находили часть Осириса, люди возводили храмы в память о боге. Когда последний фрагмент был найден Исидой, она приступила к священному ритуалу. Ей удалось на некоторое время вернуть к жизни Осириса.

Как рассказывают мифы, богиня приняла облик сокола и соединилась с энергией супруга. В тот миг в ней зародилась жизнь. Осирис вынужден был вернуться в царство мёртвых, где стал правителем и главным судьёй, а Исида родила бога Гора, который справедливо наказал злого Сета.

Исида и тайное имя Ра

Однако порой Исида предстаёт хитроумной колдуньей, способной добиться желаемого любой ценой. Известно, что у бога Ра было тайное имя (какое – до сих пор неизвестно, ведь в древних текстах оно не указано). Исиде хотелось знать его, ведь тогда весь мир оказался бы в её подчинении. Упрямый Ра не отвечал на её вопросы. Тогда Исида с помощью магии наслала болезнь на бога.

Он знал, что излечить от недуга его сможет только Исида, а для исцеляющего заклинания необходимо было открыть богине своё тайное имя. Ра пришлось это сделать, после чего Исида изгнала болезнь, насланную ею же.

Не думаю, что бог пожалел о своих словах, поскольку своё знание Исида никогда не использовала против людей. Наоборот, богиню представляли защитницей и священной помощницей. Она являлась покровительницей царской семьи, что в текстах египтян описывается как земное воплощение богов.

Неспроста Исиду называют самой известной из богинь дохристианского времени. Она действительно повелевала многими стихиями и сферами жизни. Исида и являлась этой самой жизнью, которую дарила всему на свете – растениям, животным, людям. Её звездой считался Сириус, восход которого знаменовал разлив Нила. Даже свою священную реку древние египтяне называли “слезами Исиды”, которая оплакивала умершего мужа.

Мифология

Исида (египт. Исет) — одна из главных богинь в древнеегипетской религии, богиня жизни, смерти и магии в египетской мифологии, поклонение которой впоследствии распространилось по всему греко-римскому миру. Исида является частью гелиопольской Эннеады — девяти божеств, произошедших от бога-создателя Атума или Ра. В мифах Исида фигурирует, как дочь Геба — бога земли и Нут — богини неба, супруга Осириса, сестра Нефтиды и Сета, мать Хора. Имя богини, вероятно, означает «престол», «трон» и идентично знаку, который она несет на своей голове.

Впервые Исида упоминается в текстах Древнего царства (ок. 2686—2181 до н.э.) во времена Пятой династии (ок. 2494—2345 гг. до н.э.), как один из главных персонажей мифа об Осирисе, в котором она воскрешает своего убитого мужа, божественного царя Осириса, рождает от него сына Хора и защищает его. Во времена Нового Царства (ок. 1550—1070 гг. до н. э.), Исида стала отождествляться с богиней любви Хатхор и изображалась в головном уборе Хатхор: солнечный диск между рогами коровы. В дальнейшем значение Исиды в египетской мифологии также неуклонно возрастало. Если в период классического Египта она была представлена лишь в неотъемлемой связи с Осирисом, то в Птолемеевском эллинистическом Египте Исида превратилась в полноценное божество со множеством индивидуальных ролей. Она воспринималась, как Владычица всего: Всевидящая и Всемогущая, Спасительница, Учредительница, Судьба, Мудрость, Покровительница царствующей династии и т. д. В первом тысячелетии до нашей эры Осирис и Исида стали самыми почитаемыми египетскими божествами, при этом, Исида переняла черты многих других богинь. Правители Египта и его южного соседа, Нубии, построили храмы, посвященные Исиде, а ее храм на острове Филе посреди Нила был религиозным центром как для египтян, так и для нубийцев.

В эллинистический период (323–30 гг. до н.э.), когда Египтом правили греки, Исиде поклонялись как греки, так и египтяне.

Греческие приверженцы Исиды приписывали ей черты, взятые у греческих божеств, такие как изобретение брака и защита кораблей в море. После того как эллинистическая культура была поглощена Римом в первом веке до нашей эры, культ Исиды стал частью римской религии.

Мифы об Исиде

Античные авторы приводят различные версии происхождения Исиды. Так, согласно Плутарху, Исида была дочерью «великой матери богов» Реи от Гермеса. Дочерью «Гермеса Древнего» названа Исида и в одном из греческих магических папирусов (PGM.IV.2289). Также у Плутарха («Исида и Осирис», 3, 352А), Клемента Александрийского (Строматы 1.21.106) и Евсевия (Евангельское приготовление X. 12.22), Исида именуется дочерью Прометея. Некоторые другие античные источники называют Исиду дочерью греческой богини-земли Геи или Урана [1].

В герметическом трактате «Дева мира» сказано, что Исида и Осирис совместно ввели в человеческую жизнь «средства к существованию» (К.К. 23.65.1). В гимне Исидора Исида-Деметра доставляет для людей не только «пропитание» (H.lsid. 1.5) — ее «деяния» состоят в открытии для человечества элементов цивилизованной жизни: законов, морали, техники (H.Isid. I.4-8). <…> Диодор приписывает открытие зерен и плодов Исиде (эллинистическая традиция, восходящая к Леону Пеллею) <…> Согласно ареталогиям, Исида, подобно Деметре, открыла плоды земли (Куте.7; Hymn.Isid.1.8; П.З) <…> Исида, отождествленная с Деметрой, именуется «создательницей всей жизни» (Hymn. Isid.I.3-4) а также полезных навыков, способствующих улучшению жизни (Ibid. I.6-7). Отрывок у Диодора, где сообщается о том, как Исида нашла ячменные зерна, находит параллель в тексте Августина (August. De civ.Vff l.27 со ссылкой на Леона Пеллея)[2].

Исида принимает на себя роль покровительницы справедливого миропорядка и выступает в качестве олицетворения правды. В поздних источниках такие ассоциации приписываются Исиде довольно часто в связи с установлением в Египте добрых нравов и законов. Плутарх в одном из трактатов замечает, что, когда египетский царь Бокхорис становился жестоким, то Исида, для того, чтобы он судил справедливо, насылала на него змею, которая обвивала сверху его голову (Plut. De vitios.pud. III.529Р). Согласно Элиану, змею Фермуфис повязывают на изображения Исиды, как диадему. Причем эта змея не трогает добродетельных людей, но убивает только злодеев. Поздние античные авторы часто изображают Исиду изобретательницей египетской письменности (August. De civ. XVin.37). Также некоторые авторы приписывали Исиде открытие обработки льна (Марциан Капелла. Бракосочетание Филологии и Меркурия II.157-158: «Исида явила употребление и сеяние льна»), плавания под парусом (Гигин. Мифы 277: «Паруса первой сделала Исида: ведь когда они искала своего сына Гарпократа, она плыла на плоту под парусами») и покровительство мореходству и морякам.

Наиболее известными египетскими мифами, связанными с Исидой, являются миф об Исиде и Осирисе и миф об Исиде и Ра.

Миф об Исиде и Осирисе

Первое упоминание о богине Исиде встречается в мифе об Осирисе, впервые зафиксированном в «Текстах пирамид». В этом мифе она воскрешает своего убитого мужа, божественного царя Осириса, производит на свет и защищает его наследника Гора. Впоследствии важная роль Исиды в загробном мире была основана на этом мифе.

Единственным дошедшим до нас связным изложением этого мифа является трактат «Исида и Осирис» древнегреческого писателя и философа Плутарха, жившего во II веке. Отдельные эпизоды этой священной истории также отражены в египетских иероглифических текстах. Египетские источники рассказывают о таких важных моментах мифа, как растерзание Осириса, его воскрешение и зачатие от него Исидой Хора, сражение и судебная тяжба Хора и Сета-Тифона, снисходительное обращение Исиды с побежденным Тифоном, ссора Хора с матерью и т. д.

Осирис вызвал ревность своего (старшего) брата, Сета. Согласно самой ранней традиции, Сет подстерег Осириса, когда тот охотился в пустыне на газелей, и убил его. (Более поздние источники заявляют, что Сет действовал с шайкой из семидесяти двух сообщников или, согласно Плутарху, также с эфиопской царицей по имени Асо. И заговорщики положили Осириса, то ли убитого, то ли живого, в гроб, который они сбросили в реку.) Его верная жена, Исида (которая, как нам рассказывает Плутарх, получила первую информацию от «Панов и Сатиров» из Хеммиса, то есть от духов, которые сопутствовали рождению солнца), разыскивала его и, найдя в пустыне или реке, оживила Осириса с помощью волшебства. (Согласно другим версиям, она обнаружила, что Сет разрубил его на четырнадцать кусков, которые Исида с величайшей заботой собрала вместе при помощи Анубиса или мудрого Тота.) В веровании более позднего периода, когда всех богов представляли крылатыми, она вдохнула в него жизнь (только на время) своими крыльями. Согласно еще одной (поздней) версии, Исида не объединила фрагменты, но похоронила их там, где нашла <…> Согласно еще одной (поздней) версии, Исида последовала за телом к Финикийскому побережью, куда его в сундуке принесло течением. В Библе, как рассказывает нам Плутарх, его взяла в дом царская чета, Мелькарт и Астарта (то есть два городских бога Библа, как азиатские двойники Осириса и Исиды), вместе со стволом (который вырос из вереска или тамариска (когда на него вынесло сундук с телом Осириса) или стал таким кустом или деревом. Другие мифы дополняют эту историю, упоминая о кедре, в котором находилось тело Осириса, или его сердце, или голова). Из-за благоухания, окружавшего Исиду, придворные дамы наняли богиню няней к маленькому принцу, и она кормила его, кладя палец в его рот, а ночью клала его в «очищающий огонь» и в виде ласточки летала, причитая, вокруг деревянной колонны, в которой находилось тело Осириса. Царица неожиданно нагрянула к ней однажды ночью, закричала, когда увидела ребенка, объятого пламенем, и лишила его, таким образом, бессмертия. Открыв ей свою божественную природу, Исида получила столь желанную колонну и вырезала гроб или тело из ствола дерева. Сама колонна, обернутая, как мумия, в льняную ткань и пропитанная миррой, осталась как объект поклонения в Библе. Сопровождаемая своей сестрой Нефтидой, Исида вернула тело, то ли одно, то ли в гробу, обратно в Египет, чтобы оплакать его. Как плакальщиц, обеих сестер часто представляли в облике птиц. (Плутарх заставлял Сета, охотящегося при свете луны, снова найти тело и разрезать его на куски, которые Исида обязана была собрать воедино.) Согласно некоторым версиям, Гор был рожден (или зачат) до смерти своего отца. (Другие утверждали, однако, что он был произведен на свет, пока Исида и Осирис были еще в чреве их матери, то есть неба.) Превалировала теория, что Исида забеременела от трупа Осириса, (временно) оживленного (не открывая полностью гроба, или от вновь собранного тела, или даже просто от частей его), то ли человеческим способом, когда ее часто представляют сидящей на гробе и обычно принимающей форму птицы, или от крови, сочащейся из тела или из его частей. (Существуют более ранние варианты, что она забеременела от плода древа судьбы (обычно виноградной лозы) или от другой части этого древа; эти точки зрения, однако, приложимы также к рождению Осириса, который, в конце концов, как мы часто наблюдали, идентичен своему сыну, хотя он, скорее, представляет пессимистическую сторону мифа.) Со своим сыном Гором (еще не рожденным, или новорожденным, или очень юным) Исида бежала (из тюрьмы) в болота Нижнего Египта и (в виде коровы) спряталась от преследований Сета в зеленых зарослях джунглей на острове (или на плавучем острове, чье название греки передавали как Хеммис), где Гор, как другие солярные божества, родился в зеленых зарослях. Разные боги и богини, особенно ее сестра Нефтида и мудрый Тот, защищали Исиду и ухаживали за ней и младенцем богом. Некоторые сообщали, что Исида, чтобы спрятать ребенка, поместила его в сундук или корзину, которую пустила плыть по течению Нила. <…> Согласно некоторым источникам, Исида также заботилась об Анубисе, ребенке своей сестры (от Осириса, который зачал его, спутав Исиду и Нефтиду), и, воспитывая его, приобрела верного соратника [3].

Во время битвы Хора и Сета

Исида освободила Сета; или, по крайней мере, <…> она защитила его от смертельного удара; Гор обезглавил свою мать за этот поступок — объяснение обезглавленной женщины как Исиды. Позднее ее человеческое тело и голову коровы на некоторых рисунках объясняли как результат излечения этой раны богом Тотом [4].

В некоторых текстах относящихся к этому мифу, Исида также называется супругой Хора.

Миф об Исиде и Ра

Дошедший до нас миф об Исиде и Ра записан на «Туринском папирусе» конца Нового царства.

«И вот жила Исида, женщина, знающая магические слова. Сердце ее отвернулось от миллионов людей и обратилось к миллионам богов. [И задумала богиня стать подобной Ра в его могуществе, завладев тайным его именем.] Выступал Ра изо дня в день во главе своих гребцов и восседал на престоле обоих горизонтов. Но вот состарился бог: рот его дрожит, слюна его стекает на землю… Растерла Исида в руке своей слюну, смешала ее с землей и вылепила могучего змея с ядовитыми зубами, такими, что никто не мог уйти от него живым. Она положила его на пути, по которому должен был шествовать Великий Бог, согласно своему желанию, вокруг Обеих Земель [Египта]. И вот поднялся могучий бог перед богами, подобно фараону — да будет он жив, невредим, здрав, — и вместе со своей свитой двинулся в путь, как [он это делал] каждодневно. И вонзил в него могучий змей свои зубы. Живой огонь разлился по телу бога и поразил [его], обитающего в кедрах. Раскрыл могучий бог свои уста, и крик Его Величества — да будет он жив, невредим, здрав — достиг небес. И сказали боги Девятки: — Что это? Стали спрашивать его боги [о том, что с ним случилось]. Но не смог он ответить потому, что дрожали его челюсти, трепетали все его члены: яд охватил все его тело, подобно тому как Хапи [Нил] заливает всю страну во время половодья. Но вот Великий Бог собрался с силами [букв.— решился в сердце своем] и [крикнул богам, которые были] в его свите: — Подойдите ко мне, возникшие из плоти моей, вышедшие из меня, ибо хочу я поведать вам о том, что случилось со мной. Меня ужалило нечто смертоносное, о чем знает мое сердце, но чего не видели мои глаза и не может ухватить моя рука. Я не знаю, кто мог сделать такое со мной. Никогда раньше я не испытывал боли, подобной этой, еще не было боли страшнее. <…> Сердце мое полно пылающего огня, тело мое дрожит, члены мои разрывает боль. Пусть придут ко мне мои дети — боги, владеющие чарами речей и умеющие произносить их, — чья сила достигает небес. И приблизились к нему его дети, и каждый бог причитал над ним. Прибыла Исида со своими чарами, и было в устах ее дыхание жизни. Ведь слова, реченные ею, уничтожают болезни и оживляют тех, чье горло не дышит [букв. — закрыто]. И она сказала: — Что случилось, божественный отец мой? Неужели змей влил в тебя свой яд? Неужели один из созданных тобой поднял свою голову против тебя? Я повергну его своими заклинаниями… <…> Исида сказала Ра: — О мой божественный отец, скажи мне свое имя, ибо тот, кто скажет свое имя, будет жить. Ответил Ра: — Я — создатель неба и земли. Я сотворил горы и все то, что на них. Я — создатель вод. Я сотворил Мехет-Урт, создал Кем-атефа и сладость любви. Я — создатель небес и тайн обоих горизонтов, я поместил там души богов. Я — отверзающий свои очи и создающий свет. Я — закрывающий свои очи и сотворяющий мрак. Я — тот, по чьему повелению разливаются воды Нила, и тот, чье имя неведомо богам. Я — творец времени и создатель дней. Я открываю [праздничные] торжества. Я — вызывающий разлив. Я — создатель огня и жизни.<…> Я — Хепри утром, Ра в полдень, Атум вечером. Но не выходил яд, и боль не оставляла Великого Бога. И сказала Исида Ра: — Среди слов, которые ты говорил мне, не было твоего имени. Открой мне свое имя, и яд выйдет из тебя, ибо будет жить тот, чье имя произнесено. В это время яд жег, растекаясь пламенем, и жар его был сильнее, чем от огня. И сказал Его Величество Ра: — Пусть Исида обыщет меня и да перейдет имя мое из моего тела в ее тело. И Божественный сокрылся от богов, и опустел трон в Ладье миллионов [лет]. Когда пришло время, чтобы вышло сердце бога, Исида сказала своему сыну Хору: — Да будет связан он клятвой бога и да отдаст свои глаза (солнце и луну)! Когда Ра назвал свое имя, Исида, Великая Чарами, сказала: — Уходи, яд, выйди из Ра. Пусть Око Хора, выходящее из бога, засияет золотом на его устах. Я делаю так, чтобы яд упал на землю, ибо он побежден. Великий Бог отдал свое имя. Да будет жить Ра и да погибнет яд! Пусть погибнет яд и будет жить Ра» [5].

Таким образом, в этой «Легенде о Ра и змее» Исида предстает в своей главнейшей ипостаси — как хитрая, умная богиня, в совершенстве владеющая магическим искусством, «великая чарами», мудрейшая богиня, познавшая тайны богов и людей и, наконец, посвященная в тайну тайн — знание сокровенного имени Ра.

Мистерии Исиды

В эллинистическую эпоху культ Исиды стал сопровождаться проведением мистерий. В мистериях люди усматривали надежду на лучшую жизнь в загробном мире и способ избавления от несовершенного земного устройства. В основу мистерий Исиды легли Элевсинские мистерии в честь греческой богини земледелия Деметры. Именно в эллинистическую эпоху утвердилась ипостась Исиды-плодородной земли, Исиды-Деметры. Мистерии Исиды представляли собой обряд символической смерти и последующего возвращения к жизни и спасения, получаемого по милости богини. Историк Диодор приписывает Исиде изобретение лекарства, дарующее бессмертие, под чем подразумевается учреждение мистических таинств.

Как пишет Плутарх в своем трактате, Исида, «не пренебрегла борьбой и битвами, которые выпали ей на долю, не

предала забвению и умолчанию свои скитания и многие деяния мудрости и мужества, но присовокупила к священнейшим мистериям образы, аллегории и памятные знаки перенесенных ею некогда страданий и посвятила их в качестве примера благочестия и одновременно ради утешения мужчинам и женщинам, которые претерпевают подобные же несчастия». Согласно интерпретации Плутарха, Исида приуготовляет посвященных через различные испытания к постижению «Первого, Владычествующего и доступного только мысли» , т.е. Осириса («Исида и Осирис», 2, 352А; 3, 352А; 78, 383А). Примечательно, что Плутарх делает особенное ударение на том, что совершенное познание и просвещение (преображение) человек может достигнуть только через приобщение к таинствам богини. И Плутарх, и, впоследствии, Апулей говорят о том, что конечная цель мистерий состоит в постижении Осириса. Но римский поэт Овидий ставит мистерии Исиды на высшую ступень, говоря:

- «Вечно Осирис честной пусть твои таинства чтит!» (Ovid. Amor. II.13.12).

Мистерии Исиды описываются в романе Апулея «Золотой осел» (Apul., Metam., XI, 3-5). В этой истории попавший в беду римлянин Луций возносит молитву о помощи Исиде, которую называл Небесной Царицей, потом он попал в плен сна и получил сновидение. В какое-то мгновение пред ним является прекрасная женщина, которая поднялась над морем, одетая в покрывало, обсыпанное звездами и луной. Женщина стала объяснять юноше, что она мать всех и царица мертвых и бессмертных. Она призналась, что известна под многими именами, одним из которых является Исида – мать богов, явившаяся перед ним в ответ на его молитвы. Далее в романе описывается посвящение Луция в ее таинства:

Достиг я пределов смерти, переступил порог Прозерпины и снова вернулся, пройдя все стихии, видел я пучину ночи, видел солнце в сияющем блеске, предстоял богам подземным и небесным и вблизи поклонился им. <…> Настало утро, и по окончании богослужения я тронулся в путь, облаченный в двенадцать священных стол <…> по самой середине храма против статуи богини на деревянном возвышении я был поставлен одетый поверх полотняной нижней одежды цветной нарядной верхней. С плеч за спину до самых пят спускался у меня драгоценный плащ. Взглянув внимательно на него, всякий увидел бы, что на мне кругом разноцветные изображения животных: тут и индийские драконы, и гиперборейские грифоны, животные, которых другой мир создает наподобие пернатых птиц. Стола эта у посвященных называется олимпийской. В правой руке держал я ярко горящий факел; голову мою прекрасно окружал венок из светлой пальмы, листья которой расходились в виде лучей. Разукрашенный наподобие солнца, помещенный против статуи богини, при внезапном открытии завесы я был представлен на обозрение народа. После этого я торжественно отпраздновал день своего духовного рождения, устроив изысканную трапезу с отборными винами. Так продолжалось три дня. На третий день после таких церемоний закончились и священные трапезы, и завершение моего посвящения [6].

Согласно герметическому трактату «Корэ Косму» («Дева Мира»), Исида устанавливает на земле мистерии совместно с Осирисом:

«Они, узнав от Гермеса, что все вещи внизу по воле бога-творца соответствуют вещам наверху, учредили на земле священные таинства, связанные с таинствами небесными».

Символизм Исиды

Уже в древности Исиду связывали с самой яркой звездой созвездия Большого Пса (рядом с Орионом) — Сотис (Плутарх пишет, что египтяне именовали созвездие Исиды Сотис, а греки соответственно называют Собакой), царицей неподвижных звезд а в позднюю эпоху ее также ассоциировали с планетой Венерой как Вечерней звездой (дочерью солнца) или Утренней звездой (матерью Солнца). В «Гимне Исиде» птолемеевского времени богиня названа «Сотис, владычицей небес». В греко-египетской иконографии Исида часто изображалась верхом на собаке. Также Исиду связывали с Луной и небом. Об отождествлении Исиды с Луной говорят Диодор, Плутарх и многие позднеантичные авторы. В античности Луну ассоциировали с ростом и питанием, и потому естественно, что она считалась «женским» светилом, связанным с физиологическими циклами, зачатием, беременностью и кормлением. Как богиня природы при сотворении Исида находилась в солнечной ладье Ра и, вероятно, олицетворяла рассвет.

На древних изображениях Исида имела рога или даже голову коровы. Священным животным Исиды, как богини-матери, считалась «великая белая корова Гелиополя» — мать мемфисского быка Аписа. Геродот упоминает о коровьих рогах Исиды (Herod. 11.41), а во времена Диодора считалось, что на голове Исиды не рога, а полумесяц (Диодор 1.11.4). Плутарх также пишет, что рога, с которыми изображается Исида, символически означают лунный серп. Часто Исида изображается в образе матери, кормящей грудью младенца Хора, принявшего облик фараона.

Одним из распространенных символов богини является амулет тиет — «узел Исиды», имеющий форму петли, похожую на анк. Его также называли «кровь Исиды», так как он часто изготовлялся из минералов красного цвета — сердолика и яшмы. Этот амулет использовался в качестве погребального для защиты своего владельца. Другим важным атрибутом Исиды был музыкальный инструмент систр — ударный музыкальный инструмент, по форме напоминающий букву Y.

Исида, как воскресительница Осириса и исцелительница Ра, наделялась целительными способностями. Диодор и Иоанн Лид упоминают об Исиде как о подательнице телесного здоровья (Диодор I. 25.5; Иоанн Лид De mens. IV. 45.696). В гимнах Исидора прославляется целительское искусство Исиды (Isid. 1.29-34; П.7-8). Христианский автор Софроний в житии Кирилла Александрийского пишет, что Исида— это «мрачный египетский демон», который обитает в храмовом притворе и обманывает людей мнимым исцелением.

Исида выступает в роли покровительницы царской власти. Текст из Дендера называет Исиду «правительницей Египта и предводительницей Обеих Земель», а также «царицей и правительницей Обеих Земель». В надписях и гимнах храма на Филе неоднократно повторяется, что без благоволения Исиды ни один царь не вступает на престол. Этим функциям соответствовали такие важнейшие атрибуты Исиды, как трон (древнейший символ, знак ее имени), урей и перо маат на голове.

Из стихий Исида связана с Землей, Водой и, отчасти, с Воздухом. Так, у Плутарха она отождествляется с плодородной землей, с которой соединяется во время разлива Нил. Исида считалась покровительницей плодородия и рожениц, вод (в том числе морских) и мореплавания. В качестве защитницы мореплавателей Исида могла изображаться с рулем корабля. Во времена Птолемеев Исида ассоциировалась с дождем, который в египетских текстах называется «Нил в небе». Почиталась Исида и как богиня ветра, создавшая его взмахами своих крыльев. Римский автор Лукиан сообщает, что в Египте Ио-Исида управляет разливами Нила и распоряжается ветрами (Luc. Dial. deor.3; cf. Kyme.39; Р.Оху 1380.237).

Античный неоплатоник Прокл говорит о хтонической природе Исиды и Деметры. Земля, будучи «производительницей», также является и «хранительницей» дня и ночи, поскольку она определяет их границы, их равновесие, их возрастание и убывание. Порфирий (Порфирий. De imag. ар. Евсевий. Приуготовление к Евангелию III. 11.49) называет Исиду одновременно «силой небесной земли» и «хтонической силой». В надписи из Филе говорится: «Осирис — это Нил, Исида — это поле, пашня». В своем трактате Плутарх интерпретирует образ Исиды как «женское начало природы», «кормилицы» и «всеобъемлющей». Некоторые позднеантичные и христианские авторы изображают Исиду как вечную силу, порождающую и питающую все живое (Евсевий. Приуготовление к Евангелию. III. 11.50; Макробий. Сатурналии. 1.20(18). В позднюю эпоху представления об Исиде, как «всеобщей Матери», были довольно широко распространены, поскольку ко времени римского владычества в Египте Исида заняла положение верховной, космической богини. Апулей перечисляет 13 народов, почитающих Исиду под разными именами, Оксиринхский папирус приводит названия 67 культовых центров Исиды в Нижнем Египте, и 55 — вне Египта. Исида во II в. н. э. превращается в женский аналог «единого бога» — она становится не просто вселенской богиней, но и «всебогиней» (Пантеей), объединяя в себе образы различных женских божеств.

Как сообщает Диодор, на стеле Исиды в Низе (Аравия) было написано:

«Я — Исида, царица всех земель, воспитанная Гермесом, и я установила столь великое, что это никто не сможет уничтожить. Я — старшая дочь самого молодого бога Крона. Я — жена и сестра царя Осириса. Я — первая, открывшая для людей плоды земли. Я — мать Хора царя. Я — восходящая (звезда) в созвездии Пса, мною построен город Бубастис. Радуйся, радуйся, о Египет, взрастивший меня!».[7]