18 марта 2009 года ФИФА заявила, что на проведение чемпионатов 2018/2022 годов было принято 9 заявок, которые подали: Австралия, Англия, Индонезия, Мексика, Россия, США, Япония, Также было подано две совместные заявки: от Португалии и Испании и вторая — от Бельгии и Нидерландов.

ФИФА, руководствуясь действующим положением о ротации континентов, из числа претендентов были исключены Австралия, Индонезия, Мексика, США и Япония. Таким образом, в голосовании приняли участие четыре заявки: от России, Англии и две совместные заявки: от Испании — Португалии и от Бельгии — Нидерландов.

2 декабря 2010 года в Цюрихе по результатам голосования было принято решение отдать России право проведения чемпионата мира 2018 года. Россия победила уже во втором туре, набрав более половины голосов:

| Страны-претенденты | Первый тур | Второй тур |

|

Россия |

9 | 13 |

|

Испания /

Португалия |

7 | 7 |

|

Нидерланды /

Бельгия |

4 | 2 |

|

Англия |

2 | — |

Выбор места проведения ЧМ 2026

На прошедшем 13 июня 2018 года в Москве 68-м Конгрессе ФИФА было принято решение о месте проведения финального турнира чемпионата мира по футболу 2026 года. Финальная часть турнира пройдет летом 2026 года сразу в трех странах — в США, Канаде и Мексике.

Матчи турнира состоятся в 23 городах:

— в 17 городах США (Нью-Йорк/Нью-Джерси, Филадельфия, Балтимор, Вашингтон, Бостон, Цинциннати, Нэшвилл, Атланта, Орландо, Майами, Хьюстон, Даллас, Лос-Анджелес, Сан-Франциско, Денвер, Канзас-Сити, Сиэтл),

— в 3-х городах Канады (Эдмонтон, Торонто, Монреаль),

— в 3-х городах Мексики (Мехико, Гвадалахара, Монтеррей).

Матчи чемпионата мира примут 11 городов Российской Федерации: Москва, Калининград, Санкт-Петербург, Волгоград, Казань, Нижний Новгород, Самара, Саранск, Ростов-на-Дону, Сочи и Екатеринбург. Матчи будут проводиться на 12 стадионах.

Стадионы

| № | Город | Название стадиона | Вместимость, в тыс. чел. |

| 1 | Москва | «Лужники» | 84 745 |

| 2 | Москва | «Открытие Арена» | 45 360 |

| 3 | Санкт-Петербург | «Санкт-Петербург» | 68 134 |

| 4 | Казань | «Казань Арена» | 45 105 |

| 5 | Екатеринбург | «Екатеринбург Арена» | 35 000 |

| 6 | Саранск | «Мордовия Арена» | 45 015 |

| 7 | Самара | «Самара Арена» | 44 918 |

| 8 | Сочи | «Фишт» | 47 659 |

| 9 | Ростов-на-Дону | «Ростов Арена» | 45 000 |

| 10 | Калининград | «Калининград» | 35 015 |

| 11 | Нижний Новгород | «Нижний Новгород» | 44 899 |

| 12 | Волгоград | «Волгоград Арена» | 45 015 |

Распределение матчей по стадионам

24 июня 2015 года ФИФА опубликовала предварительный календарь проведения финального турнира чемпионата мира по футболу 2018 года.

Матч открытия чемпионата мира 2018 года, в котором примет участие сборная России состоится 14 июня на московском стадионе «Лужники». Два других матча группового турнира россияне проведут в Санкт-Петербурге (19 июня) и в Самаре (25 июня).

В том случае, если наша сборная займет в группе А первое место, свой матч 1/8 финала против второй команды группы В она проведет 30 июня в Сочи. Если наша команда займет в своей группе второе место, то матч 1/8 финала она проведет 1 июля на стадионе «Лужники» против команды, занявшей в группе В первое место.

Остальные матчи 1/8 финала чемпионата мира пройдут в Москве на стадионах «Лужники» и «Открытие Арена», а также в Санкт-Петербурге, Казани, Сочи, Нижнем Новгороде, Ростове-на-Дону и Самаре.

Матчи 1/4 финала пройдут 6–7 июля в Казани, Нижнем Новгороде, Самаре и Сочи.

Полуфинальные матчи состоятся в Санкт-Петербурге — 10 июля и в Москве на стадионе «Лужники» — 11 июля.

Матч за третье место пройдет 14 июля в Санкт-Петербурге.

Финальный матч пройдет 15 июля в Москве на стадионе «Лужники».

«Волгоград Арена»

18 июня — Группа G. 1-й тур Тунис — Англия 1:2

22 июня — Группа D. 2-й тур Нигерия — Исландия 2:0

25 июня — Группа A. 3-й тур Саудовская Аравия — Египет 2:1

28 июня — Группа H. 3-й тур Япония — Польша 0:1

«Екатеринбург Арена»

15 июня — Группа A. 1-й тур Египет — Уругвай 0:1

21 июня — Группа C. 2-й тур Франция — Перу 1:0

24 июня — Группа H. 2-й тур Япония — Сенегал 2:2

27 июня — Группа F. 3-й тур Мексика — Швеция 0:3

«Казань Арена»

16 июня — Группа C. 1-й тур Франция — Австралия 2:1

20 июня — Группа B. 2-й тур Иран — Испания 0:1

24 июня — Группа H. 2-й тур Польша — Колумбия 0:3

27 июня — Группа F. 3-й тур Южная Корея — Германия 2:0

30 июня — 1/8 финала. Франция — Аргентина 4:3

6 июля — 1/4 финала Бразилия — Бельгия 1:2

«Калининград Арена»

16 июня — Группа D. 1-й тур Хорватия — Нигерия 2:0

22 июня — Группа E. 2-й тур Сербия — Швейцария 1:2

25 июня — Группа B. 3-й тур Испания — Марокко 2:2

28 июня — Группа G. 3-й тур Англия — Бельгия 0:1

«Лужники» (Москва)

14 июня — Группа A. 1-й тур Россия — Саудовская Аравия (матч открытия) 5:0

17 июня — Группа F. 1-й тур Германия — Мексика 0:1

20 июня — Группа B. 2-й тур Португалия — Марокко 1:0

26 июня — Группа C. 3-й тур Дания — Франция 0:0

1 июля — 1/8 финала. Испания — Россия 1:1 (3:4) П

11 июля — Полуфинал. Хорватия — Англия 2:1 ДВ

15 июля — Финал чемпионата. Франция — Хорватия 4:2

«Мордовия Арена»

16 июля — Группа C. 1-й тур Перу — Дания 0:1

19 июня — Группа H. 1-й тур Колумбия — Япония 1:2

25 июня — Группа B. 3-й тур Иран — Португалия 1:1

28 июня — Группа G. 3-й тур Панама — Тунис 1:2

«Нижний Новгород»

18 июня — Группа F. 1-й тур Швеция — Южная Корея 1:0

21 июня — Группа D. 2-й тур Аргентина — Хорватия 0:3

24 июня — Группа G. 2-й тур Англия — Панама 6:1

27 июня — Группа E. 3-й тур Швейцария — Коста-Рика 2:2

1 июля — 1/8 финала. Хорватия — Дания 1:1 (3:2) П

6 июля — 1/4 финала Уругвай — Франция 0:2

«Открытие Арена» (Москва)

16 июня — Группа D. 1-й тур Аргентина — Исландия 1:1

19 июня — Группа H. 1-й тур Польша — Сенегал 1:2

23 июня — Группа G. 2-й тур Бельгия — Тунис 5:2

27 июня — Группа E. 3-й тур Сербия — Бразилия 0:2

3 июля — 1/8 финала. Колумбия — Англия 1:1 (3:4) П

«Ростов Арена»

17 июня — Группа E. 1-й тур Бразилия — Швейцария 1:1

20 июня — Группа A. 2-й тур Уругвай — Саудовская Аравия 1:0

23 июня — Группа F. 2-й тур Южная Корея — Мексика 1:2

26 июня — Группа D. 3-й тур Исландия — Хорватия 1:2

2 июля — 1/8 финала Бельгия — Япония 3:2

«Самара Арена»

17 июня — Группа E. 1-й тур Коста-Рика — Сербия 0:1

21 июня — Группа C. 2-й тур Дания — Австралия 1:1

25 июня — Группа A. 3-й тур Уругвай — Россия 3:0

28 июня — Группа H. 3-й тур Сенегал — Колумбия 0:1

2 июля — 1/8 финала. Бразилия — Мексика 2:0

7 июля — 1/4 финала Швеция — Англия 0:2

«Санкт-Петербург»

15 июня — Группа B. 1-й тур Марокко — Иран 0:1

19 июня — Группа A. 2-й тур Россия — Египет 3:1

22 июня — Группа E. 2-й тур Бразилия — Коста-Рика 2:0

26 июня — Группа D. 3-й тур Нигерия — Аргентина 1:2

3 июля — 1/8 финала. Швеция — Швейцария 1:0

10 июля — Полуфинал. Франция — Бельгия 1:0

14 июля — Матч за 3-е место Бельгия — Англия 2:0

«Фишт» (Сочи)

15 июня — Группа B. 1-й тур Португалия — Испания 3:3

18 июня — Группа G. 1-й тур Бельгия — Панама 3:0

23 июня — Группа F. 2-й тур Германия — Швеция 2:1

26 июня — Группа C. 3-й тур Австралия — Перу 0:2

30 июня — 1/8 финала. Уругвай — Португалия 2:1

7 июля — 1/4 финала Россия — Хорватия 2:2 (3:4) П

Эмблема турнира

Эмблема чемпионата мира по футболу 2018

В октябре 2014 года в эфире Первого канала в программе «Вечерний Ургант» была представлена официальная эмблема чемпионата мира по футболу 2018 года. В мероприятии представления символики турнира приняли участие президент ФИФА Йозеф Блаттер, министр спорта России Виталий Мутко и лучший футболист мира 2006 года итальянец Фабио Каннаваро.

Как указано в пресс-релизе оргкомитета турнира в основу логотипа вошли три составляющих — покорение космоса, иконопись и любовь к футболу. Внеше логотип ЧМ 2018 года напоминает силуэт Кубка мира ФИФА.

Талисман чемпионата

В июне 2015 года оргкомитетом «Россия 2018» по результатам онлайн-опроса, проведенного с 1 по 31 мая были отобраны 10 самых популярных персонажей, которых жители России хотят видеть в качестве талисмана чемпионата мира по футболу 2018 года.

Выбор официального талисмана проходил в несколько этапов. На первом этапе были выбраны 10 вариантов талисмана — кот, амурский тигр, волк, богатырь, дальневосточный леопард, жар-птица, инопланетянин, космонавт, медведь и робот. После этого студенты 57 российских художественных вузов принимали участие в конкурсе и представили свои эскизы для дизайна талисмана.

Всероссийское голосование по выбору талисмана чемпионата мира стартовало 23 сентября 2016 года и продолжалось почти месяц. В голосовании приняли участие более миллиона человек.

- Кот — автор Софья Подлесных (Новогородский государственный университет имени Ярослава Мудрого)

- Тигр — автор Валерия Табуренко (Санкт-Петербургский университет промышленных технологий и дизайна)

- Волк — автор Екатерина Бочарова (Томский государственный университет).

По результатам голосования российских болельщиков официальным талисманом чемпионата мира по футболу 2018 года был выбран волк Забивака. В ходе голосования Волк Забивака 52, 8% голосов, Тигр — 26, 8%, Кот — 20, 4%.

Презентация талисмана ЧМ-2018 прошла 21 октября 2016 года в прямом эфире программы Первого канала «Вечерний Ургант».

1 июня 2018 года ФИФА представила официальную заставку чемпионата мира 2018 года (официальный канал ФИФА в YouTube).

25 июля 2015 года в Константиновском дворце Санкт-Петербурга состоялась жеребьевка отборочного турнира чемпионата мира по футболу 2018 года. Сборная России попала в группу «H», в которую также вошли Бельгия, Греция, Босния и Герцеговина, Эстония и Кипр.

Результаты нашей команды при определении победителя группы и распределении остальных мест учитываться не будут. Таким образом, наша команда проведет товарищеские матчи с европейскими командами, которые войдут в план подготовки сборной к финальному турниру.

Это второй случай в истории проведении отборочных игр, в которых принимает участие команда, которая является хозяйкой мирового первенства. Ранее, в 1934 году, в отборочном турнире участвовала сборная Италии, но тогда ее результаты учитывались при распределении мест.

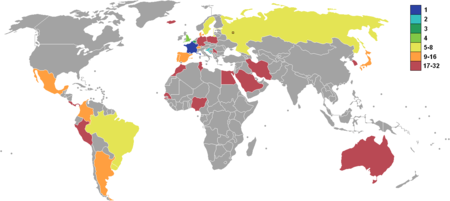

Состав участников мирового первенства

15 ноября 2017 года после завершения всех стыковых матчей стали известны все 32 национальные сборные, получившие право принять участие в чемпионате мира 2018 года.

Все 32 сборные распределены по четырем корзинам в соответствии с рейтингом ФИФА. Сборная России оказалась худшей командой по рейтингу среди всех команд, которые примут участие в финальной стадии чемпионата мира 2018 года. По состоянию на ноябрь 2017 года российская сборная занимала в рейтинге 65-е место, однако попала в первую корзину на правах хозяйки турнира. Если бы чемпионат мира проводился не в России, то наша команда попала бы в четвертую корзину.

Распределение команд по корзинам перед жеребьевкой:

Корзина А: Россия, Германия, Бразилия, Португалия, Аргентина, Бельгия, Польша, Франция.

Корзина В: Испания, Перу, Швейцария, Англия, Колумбия, Хорватия, Мексика, Уругвай.

Корзина С: Дания, Швеция, Исландия, Коста-Рика, Тунис, Египет, Сенегал, Иран.

Корзина D: Сербия, Нигерия, Япония, Марокко, Панама, Южная Корея, Саудовская Аравия, Австралия.

Жеребьевка группового этапа мирового первенства состоялась в Москве в Кремлевском Дворце съездов 1 декабря 2017 года.

Девизы сборных команд-участниц турнира

24 мая 2018 года пресс-служба ФИФА объявила девизы всех 32 команд-участниц финального турнира чемпионата мира.

Слоган сборной России — «Играй с открытым сердцем».

Предварительный состав

11 мая 2018 года тренерский штаб сборной России обнародовал расширенный состав команды для подготовки к чемпионату мира по футболу 2018. В состав списка включено 35 футболистов для расширенной заявки по регламенту ФИФА. Из них 28 уже вызваны на учебно-тренировочный сбор на базе Новогорск.

Главный тренер сборной России Станислав Черчесов назначил капитаном сборной вратаря Игоря Акинфеева.

14 мая стало известно, что после полученной в последнем туре чемпионат России травмы, защитник «Рубина» Руслан Камболов не сможет выступить в составе сборной. Вместо него тренерский штаб вызвал в состав команды защитника ЦСКА Сергея Игнашевича..

|

Игроки, вызванные на сбор |

Резервный список |

|

Вратари: |

|

|

|

|

Защитники: |

|

|

|

|

Полузащитники: |

|

|

|

|

Нападающие: |

|

|

|

Примечания:

* Вместо Руслана Камболова, получившего травму, 14 мая в состав сборной был вызван Сергей Игнашевич.

Окончательный состав

3 июня 2018 года тренерский штаб национальной сборной России обнародовал окончательный состав команды для участия в чемпионате мира. В него вошли 23 футболиста.

Вратари: Игорь Акинфеев (ЦСКА Москва), Владимир Габулов («Брюгге» Бельгия), Андрей Лунёв («Зенит» Санкт-Петербург).

Защитники: Владимир Гранат («Рубин» Казань), Сергей Игнашевич (ЦСКА Москва), Фёдор Кудряшов («Рубин» Казань), Илья Кутепов («Спартак» Москва), Андрей Семёнов («Ахмат» Грозный), Игорь Смольников («Зенит» Санкт-Петербург), Марио Фернандес (ЦСКА Москва).

Полузащитники: Юрий Газинский («Краснодар»), Александр Головин (ЦСКА Москва), Алан Дзагоев (ЦСКА Москва), Александр Ерохин («Зенит» Санкт-Петербург), Юрий Жирков («Зенит» Санкт-Петербург), Роман Зобнин («Спартак» Москва), Далер Кузяев («Зенит» Санкт-Петербург), Антон Миранчук («Локомотив» Москва), Александр Самедов («Спартак» Москва), Денис Черышев («Вильярреал» Испания).

Нападающие: Артём Дзюба («Арсенал» Тула), Алексей Миранчук («Локомотив» Москва), Фёдор Смолов («Краснодар»).

Из предварительного расширенного списка в основной состав не вошли 5 футболистов: Сослан Джанаев («Рубин»), Роман Нойштедтер («Фенербахче»), Константин Рауш, Александр Ташаев (оба — «Динамо») и Федор Чалов (ЦСКА).

В 2018 году формат финального турнира вновь остается без изменений — 32 команды, получившие право выступить в финальном турнире, разделены на 8 групп, по 4 команды в каждой. В стадию плей-офф выходят 16 команд, из которых: 8 победителей групп и 8 команд, занявших второе место.

На стадии плей-офф соревнования будут традиционно проводиться по олимпийской системе (с выбыванием) — 1/8 финала, 1/4 финала, полуфиналы, матч за 3-е место и финал.

Система видеоповторов

На нынешнем турнире впервые в истории проведения чемпионатов мира будет использоваться система видеоповторов. Система видеопомощи арбитрам (VAR) впервые на высшем уровне была обкатана на Кубке Конфедераций, проходившем также в России летом 2017 года.

Справка:

Система видеопомощи арбитрам (VAR) может быть использована в четырех случаях:

1. При забитых голах (помогает определить — пересек ли мяч линию ворот, а также не был ли он забит рукой…).

2. При удалениях (подсказывает кому и за что стоит показать красную карточку, помогает правильно определить вину всех футболистов участвовавших в конфликте на поле).

3. При назначении пенальти (определение степени вины футболиста, а также не было ли провокации со стороны упавшего игрока — так называемого.«нырка»).

4. При определение офсайда.

Главный судья может воспользоваться одним из двух вариантов для использования системы. Первый вариант — обратиться к повтору самостоятельно и просмотреть повтор эпизода на компьютере. Второй — воспользоваться подсказкой видео-ассистента по беспроводной связи.

Группа A

| № | Команды | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | В | Н | П | мячи | очки |

| 1 |

Уругвай |

3:0 | 1:0 | 1:0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5-0 | 9 | |

| 2 |

Россия |

0:3 | 5:0 | 3:1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8-4 | 6 | |

| 3 |

Саудовская Аравия |

0:1 | 0:5 | 2:1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2-7 | 3 | |

| 4 |

Египет |

0:1 | 1:3 | 1:2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2-6 | 0 |

Все матчи группы A

| Дата | Место | Матч | Голы |

| 14.06.2018 | «Лужники», Москва | Россия – Саудовская Аравия 5:0 | Газинский (12′); Черышев (43′, 90+1′); Дзюба (71′); Головин (90+4′) |

| 15.06.2018 | «Екатеринбург Арена» | Египет – Уругвай 0:1 | Хименес (90′) |

| 19.06.2018 | Санкт-Петербург | Россия – Египет 3:1 | Фатхи (47′) А; Черышев (59′); Дзюба (62′) — Салах (73′) П |

| 20.06.2018 | «Ростов Арена» | Уругвай – Саудовская Аравия 1:0 | Суарес (23′) |

| 25.06.2018 | «Самара Арена», Самара | Уругвай – Россия 3:0 | Суарес (10′); Черышев (23′) А; Кавани (90′) |

| 25.06.2018 | «Волгоград Арена» | Саудовская Аравия – Египет 2:1 | Аль-Фаридж (45+6′) П; Аль-Доссари (90+5′) — Салах (22′) |

Группа B

| № | Команды | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | В | Н | П | мячи | очки |

| 1 |

Испания |

3:3 | 1:0 | 2:2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6-5 | 5 | |

| 2 |

Португалия |

3:3 | 1:1 | 1:0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5-4 | 5 | |

| 3 |

Иран |

0:1 | 1:1 | 1:0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2-2 | 4 | |

| 4 |

Марокко |

2:2 | 0:1 | 0:1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2-4 | 1 |

Все матчи группы B

| Дата | Место | Матч | Голы |

| 15.06.2018 | «Фишт», Сочи | Португалия – Испания 3:3 | Роналду (4′, 44′, 88′) — Коста (24′, 55′); Начо (58′) |

| 15.06.2018 | Санкт-Петербург | Марокко – Иран 0:1 | Бухаддуз (90+5′) А |

| 20.06.2018 | «Лужники», Москва | Португалия – Марокко 1:0 | Роналду (4′) |

| 20.06.2018 | «Казань Арена» | Иран – Испания 0:1 | Коста (54′) |

| 25.06.2018 | «Мордовия Арена» | Иран – Португалия 1:1 | Ансарифард (90+3′) — Куарежма (45′) |

| 25.06.2018 | «Калининград Арена» | Испания – Марокко | Иско (19′); Аспас (90+1′) — Бутаиб (14′); Эн-Несири (81′) |

Группа C

| № | Команды | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | В | Н | П | мячи | очки |

| 1 |

Франция |

0:0 | 1:0 | 2:1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3-1 | 7 | |

| 2 |

Дания |

0:0 | 1:0 | 1:1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2-1 | 5 | |

| 3 |

Перу |

0:1 | 0:1 | 2:0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2-2 | 3 | |

| 4 |

Австралия |

1:2 | 1:1 | 0:2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2-5 | 1 |

Все матчи группы C

| Дата | Место | Матч | Голы |

| 16.06.2018 | «Казань Арена» | Франция – Австралия 2:1 | Гризманн (58′) П; Бехич (80′) А — Единак (62′) П |

| 16.06.2018 | «Мордовия Арена» | Перу – Дания 0:1 | Поульсен (24′) |

| 21.06.2018 | «Екатеринбург Арена» | Франция – Перу 1:0 | Мбаппе (34′) |

| 21.06.2018 | «Самара Арена» | Дания – Австралия 1:1 | Эриксен (7′) — Единак (38′) П |

| 26.06.2018 | «Лужники», Москва | Дания – Франция 0:0 | |

| 26.06.2018 | «Фишт», Сочи | Австралия – Перу 0:2 | Каррильо (18′); Герреро (50′) |

Группа D

| № | Команды | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | В | Н | П | мячи | очки |

| 1 |

Хорватия |

3:0 | 2:0 | 2:1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7-1 | 9 | |

| 2 |

Аргентина |

0:3 | 2:1 | 1:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3-5 | 4 | |

| 3 |

Нигерия |

0:2 | 1:2 | 2:0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3-4 | 3 | |

| 4 |

Исландия |

1:2 | 1:1 | 0:2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2-5 | 1 |

Все матчи группы D

| Дата | Место | Матч | Голы |

| 16.06.2018 | «Открытие Арена», Москва | Аргентина – Исландия 1:1 | Агуэро (19′),— Финнбогасон (23′) |

| 16.06.2018 | «Калининград Арена» | Хорватия – Нигерия 2:0 | Этебо (32′) А; Модрич (71′) П |

| 21.06.2018 | Нижний Новгород | Аргентина – Хорватия 0:3 | Ребич (53′); Модрич (80′); Ракитич (90+1′) |

| 22.06.2018 | «Волгоград Арена» | Нигерия – Исландия 2:0 | Муса (49′, 75′) |

| 26.06.2018 | Санкт-Петербург | Нигерия – Аргентина 1:2 | Мозес (51′) П — Месси (14′); Рохо (86′) |

| 26.06.2018 | «Ростов Арена» | Исландия – Хорватия 1:2 | Сигурдссон (76′) П — Бадель (53′); Перишич (90′) |

Группа E

| № | Команды | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | В | Н | П | мячи | очки |

| 1 |

Бразилия |

1:1 | 2:0 | 2:0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5-1 | 7 | |

| 2 |

Швейцария |

1:1 | 2:1 | 2:2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5-4 | 5 | |

| 3 |

Сербия |

0:2 | 1:2 | 1:0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2-4 | 3 | |

| 4 |

Коста-Рика |

0:2 | 2:2 | 0:1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2-5 | 1 |

Все матчи группы E

| Дата | Место | Матч | Голы |

| 17.06.2018 | «Ростов Арена» | Бразилия – Швейцария 1:1 | Коутиньо (20′) — Цубер (50′) |

| 17.06.2018 | «Самара Арена» | Коста-Рика – Сербия 0:1 | Коларов (56′) |

| 22.06.2018 | Санкт-Петербург | Бразилия – Коста-Рика 2:0 | Коутиньо (90+1′); Неймар (90+7′) |

| 22.06.2018 | «Калининград Арена» | Сербия – Швейцария 1:2 | Митрович (5′) — Джака (52′); Шакири (90′) |

| 27.06.2018 | «Открытие Арена» | Сербия – Бразилия 0:2 | Паулиньо (36′); Силва (68′) |

| 27.06.2018 | Нижний Новгород | Швейцария – Коста-Рика 2:2 | Джемаили (31′); Дрмич (88′) — Уостон (56′); Зоммер (90+3′) А |

Группа F

| № | Команды | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | В | Н | П | мячи | очки |

| 1 |

Швеция |

3:0 | 1:0 | 1:2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5-2 | 6 | |

| 2 |

Мексика |

0:3 | 2:1 | 1:0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3-4 | 6 | |

| 3 |

Южная Корея |

0:1 | 1:2 | 2:0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3-3 | 3 | |

| 4 |

Германия |

2:1 | 0:1 | 0:2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2-4 | 3 |

Все матчи группы F

| Дата | Место | Матч | Голы |

| 17.06.2018 | «Лужники», Москва | Германия – Мексика 0:1 | Лосано (35′) |

| 18.06.2018 | Нижний Новгород | Швеция – Южная Корея 1:0 | Гранквист (65′) П |

| 23.06.2018 | «Фишт», Сочи | Германия – Швеция 2:1 | Ройс (48′); Кроос (90+5′) — Тойвонен (32′) |

| 23.06.2018 | «Ростов Арена» | Южная Корея – Мексика 1:2 | Мин (90+3′) — Вела (26′) П; Эрнандес (66′) |

| 27.06.2018 | «Казань-Арена» | Южная Корея – Германия 2:0 | Квон (90+2′); Мин (90+6′) |

| 27.06.2018 | «Екатеринбург Арена» | Мексика – Швеция 0:3 | Аугустинсон (50′); Гранквист (62′) П; Альварес (74′) А |

Группа G

| № | Команды | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | В | Н | П | мячи | очки |

| 1 |

Бельгия |

1:0 | 5:2 | 3:0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 9-2 | 9 | |

| 2 |

Англия |

0:1 | 2:1 | 6:1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8-3 | 6 | |

| 3 |

Тунис |

2:5 | 1:2 | 2:1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5-8 | 3 | |

| 4 |

Панама |

0:3 | 1:6 | 1:2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2-11 | 0 |

Все матчи группы G

| Дата | Место | Матч | Голы |

| 18.06.2018 | «Фишт», Сочи | Бельгия – Панама 3:0 | Мертенс (47′); Лукаку (69′, 75′) |

| 18.06.2018 | «Волгоград Арена» | Тунис – Англия 1:2 | Сасси (35′) П — Кейн (11′, 90+1′) |

| 23.06.2018 | «Открытие Арена», Москва | Бельгия – Тунис 5:2 | Азар (6′ П, 51); Лукаку (16′, 45+3′); Батшуайи (90′) — Бронн (18′); Хазри (90+3′) |

| 24.06.2018 | Нижний Новгород | Англия – Панама 6:1 | Стоунс (8′, 40′); Кейн (22′ П, 45+1′ П; 62′); Лингард (35′) — Балой (78′) |

| 28.06.2018 | «Калининград Арена» | Англия – Бельгия | Янузай (51′) |

| 28.06.2018 | «Мордовия Арена» | Панама – Тунис | Мерия (33′) А — Юссеф (51′); Хазри (66′) |

Группа H

| № | Команды | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | В | Н | П | мячи | очки |

| 1 |

Колумбия |

1:2 | 1:0 | 3:0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5:2 | 6 | |

| 2 |

Япония |

2:1 | 2:2 | 0:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4:4 | 4 | |

| 3 |

Сенегал |

0:1 | 2:2 | 2:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4:4 | 4 | |

| 4 |

Польша |

1:2 | 1:0 | 1:2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2:5 | 3 |

Все матчи группы H

| Дата | Место | Матч | Голы |

| 19.06.2018 | «Открытие Арена», Москва | Польша – Сенегал 1:2 | Крыховяк (86′) — Сионек (37′) А; Ньянг (60′) |

| 19.06.2018 | «Мордовия Арена» | Колумбия – Япония 1:2 | Кинтеро (39′) — Кагава (6′) П; Осако (73′) |

| 24.06.2018 | «Казань Арена» | Польша – Колумбия 0:3 | Мина (40′); Фалькао (70′); Куадрадо (75′) |

| 24.06.2018 | «Екатеринбург Арена» | Япония – Сенегал 2:2 | Инуи (34′);Хонда (78′) — Мане (11′); Ваг (71′) |

| 28.06.2018 | «Волгоград Арена» | Япония – Польша 0:1 | Беднарек (59′) |

| 28.06.2018 | «Самара Арена» | Сенегал – Колумбия 0:1 | Мина (74′) |

1/8 финала

Необходимо отметить, что команды, которые считаются фаворитами чемпионата, такие как Аргентина, Испания, смогли пройти в стадию плей-офф, только благодаря забитым голам на последних минутах матча.

Настоящей сенсацией стал невыход из группы действующих чемпионов мира — сборной Германии. Немцы сумели одержать только одну победу при двух поражениях и закончили турнир на последнем месте в группе, да еще и с отрицательной разницей забитых мячей (2-4).

Еще одной особенностью нынешнего чемпионата стало то, что в 1/8 финала впервые за 32 года не вышла ни одна сборная с африканского континента.

Впервые в истории мировых чемпионатов судьбу путевки в плей-офф решило количество полученных командой желтых карточек. В группе H cборные Японии и Сенегала набрали одинаковое количество очков — по четыре при одинаковой разнице мячей — 4:4. Результат личной встречи — 2:2 также не определил победителя. По последнему дополнительному показателю — коэффициенту фэйр-плей в 1/8 прошла сборная Японии, т.к. ее игроки получили четыре желтые карточки, а игроки сборной Сенегала шесть.

Сборная России в серии послематчевых пенальти повергла сборную Испанию — признанного фаворита турнира и впервые в своей истории вышла в 1/4 финала чемпионата мира.

| Дата | Стадион | Команды | Счет | Голы |

| 30 июня | «Фишт», Сочи |

Уругвай —

Португалия |

2:1 | Кавани (7′, 62′) — Пере (55′) |

| 30 июня | «Казань Арена» |

Франция —

Аргентина |

4:3 | Гризманн (13′) П; Павар (57′); Мбаппе (64′, 68′) — Ди Мария (41′); Меркадо (48′); Агуэро (90+3′) |

| 1 июля | «Лужники» |

Испания —

Россия |

1:1 (3:4) П | Игнашевич (13′) А — Дзюба (41′) П |

| 1 июля | «Нижний Новгород» |

Хорватия —

Дания |

1:1 (3:2) П | Манджукич (4′) — Йоргенсен (1′) |

| 2 июля | «Самара Арена» |

Бразилия —

Мексика |

2:0 | Неймар (51′); Фирмино (88′) |

| 2 июля | «Ростов Арена» |

Бельгия —

Япония |

3:2 | Вертонген (69′); Феллайни (74′); Шадли (90+4′) — Харагуси (48′); Инуи (52′) |

| 3 июля | «Санкт-Петербург» |

Швеция —

Швейцария |

1:0 | Форсберг (66′) |

| 3 июля | «Открытие Арена» |

Колумбия —

Англия |

1:1 (3:4) П | Мина (90+3′) — Кейн (57′) П |

1/4 финала

Матчи стадии 1/4 финала, в которых встречались победители матчей 1/8 финала состоялись 6 и 7 июля.

Сборная России в серии послематчевых пенальти проиграла сборной Хорватии и выбыла и дальнейшей борьбы за титул. Тем не менее результат выступления нашей национальной команды на турнире нужно признать очень успешным — наша команда впервые в своей истории играла в 1/4 финала чемпионата и была в одном шаге от выхода в поуфинал.

| Дата | Стадион | Команды | Счет | Голы |

| 6 июля | «Нижний Новгород» |

Уругвай —

Франция |

0:2 | Варан (40′); Гризманн (61′) |

| 6 июля | «Казань Арена» |

Бразилия —

Бельгия |

1:2 | Аугусто (76′) — Фернандиньо (13′) А; Де Брёйне (31′) |

| 7 июля | «Фишт», Сочи |

Россия —

Хорватия |

2:2 (3:4) П | Черышев (31′); Фернандес (115′) — Крамарич (39′); Вида (100′) |

| 7 июля | «Самара Арена» |

Швеция —

Англия |

0:2 | Магуайр (30′); Алли (58′) |

Полуфинал

В двух полуфиналах турнира встретятся победители четвертьфинальных пар. Полуфинальные матчи состоятся в Санкт-Петербурге — 10 июля и в Москве на стадионе «Лужники» — 11 июля.

Примечательно, что к полуфинальной стадии среди претендентов на титул остались только европейские команды.

| Дата | Стадион | Команды | Счет | Голы |

| 10 июля 21.00 |

«Нижний Новгород» |

Франция —

Бельгия |

1:0 | Юмтити (51′) |

| 11 июля 21.00 |

«Лужники» |

Хорватия —

Англия |

2:1 ДВ | Перишич (68′); Манджукич (109′) — Триппьер (5′) |

Матч за 3-е место

Матч за третье место между командами Бельгии и Англии состоялся 14 июля на арене «Санкт-Петербург». Примечательно, что этот матч стал уже вторым между командами на этом турнире — в групповом турнире эти команды выступали в одной группе. В первой игре бельгийцы победили со счетом 1:0. В матче за 3-е место сборная Бельгии одержала более уверенную победу со счетом 2:0 и впервые в своей футбольной истории завоевала бронзовые медали чемпионата мира. В сборной Бельгии на 4-й минуте отличился защитник Томас Менье, а на 82-й минуте Эден Азар довел счет до победного.

Финал

Финал чемпионата мира между командами Франции и Хорватии состоялся 15 июля на арене «Лужники». Для сборной Франции это был уже третий финал в ее футбольной истории. Первый раз французы играли в финале домашнего чемпионата 1998 года и стали чемпионами мира, уверенно переиграв сборную со счетом 3:0. Во второй раз сборная Франции играла в финале в 2006 году. В этом матче они встречались с итальянцами и уступили им в серии послематчевых пенальти.

Для сборной Хорватии это первый выход в финал чемпионата мира.

В красивом и драматичном финальном матче сборная Франции победила сборную Хорватии со счетом 4:2 и стал чемпионом мира по футболу 2018 года. Франция стала двукратными обладателем высшего футбольного титула. Серебряные медали чемпионата достались сборной Хорватии, которая добилась наивысшего результата в своей футбольной истории.

Редактировать

Бомбардиры чемпионатов мира по состоянию на 2018 год

Наибольшее количество мячей в финальных турнирах чемпионатов мира забили:

| Мячи | Бомбардир | Чемпионаты мира |

| 16 мячей |

Мирослав Клозе (Германия) |

2002, 2006, 2010, 2014 |

| 15 мячей |

Роналдо (Бразилия) |

1994, 1998, 2002, 2006 |

| 14 мячей |

Герд Мюллер (Германия) |

1970, 1974 |

| 13 мячей |

Жюст Фонтен (Франция) |

1958 |

| 12 мячей |

Пеле (Бразилия) |

1958, 1962, 1966, 1970 |

| 11 мячей |

Шандор Кочиш (Венгрия) |

1954 |

|

Юрген Клинсманн (Германия) |

1990, 1994, 1998 | |

| 10 мячей |

Хельмут Ран (Германия) |

1954, 1958 |

|

Теофило Кубильяс (Перу) |

1970, 1978, 1982 | |

|

Гжегож Лято (Польша) |

1974, 1978, 1982 | |

|

Гари Линекер (Англия) |

1986, 1990 | |

|

Габриэль Батистута (Аргентина) |

1994, 1998, 2002 | |

|

Томас Мюллер (Германия) |

2010, 2014 |

Лучшие бомбардиры ЧМ-2018

Гарри Кейн (Англия) — 6

Криштиану Роналду (Португалия) — 4

Ромелу Лукаку (Бельгия) — 4

Денис Черышев (Россия) — 4

Антуан Гризманн (Франция) — 4

Килиан Мбаппе (Франция) — 4

Артем Дзюба (Россия) — 3

Диего Коста (Испания) — 3

Эдинсон Кавани (Уругвай) — 3

Йерри Мина (Колумбия) — 3

Эден Адар (Бельгия) — 3

Иван Перишич (Хорватия) — 3

Марио Манджукич (Хорватия) — 3.

Более 15 футболистов забили по 2 мяча.

«Золотой мяч» (лучший игрок чемпионата) — Лука Модрич (Хорватия)

«Серебряный мяч» — Эден Азар (Бельгия)

«Бронзовый мяч» — Антуан Гризманн (Франция)

«Золотая бутса» (лучший бомбардир турнира) — Гарри Кейн (Англия)

«Золотая перчатка» (лучший вратарь чемпионата – приз им. Льва Яшина) — Тибо Куртуа (Бельгия)

Приз лучшего молодого игрока — Килиан Мбаппе (Франция)

Приз «За честную игру FIFA» — сборная Испании

Символическая сборная (по версии ФИФА)

Вратарь – Тибо Куртуа (Бельгия)

Защитники – Диего Годин (Уругвай), Марсело (Бразилия), Тиаго Силва (Бразилия), Рафаэль Варан (Франция)

Полузащитники – Филиппе Коутиньо (Бразилия), Кевин де Брёйне (Бельгия), Лука Модрич (Хорватия)

Нападающие – Харри Кейн (Англия), Килиан Мбаппе (Франция), Криштиану Роналду (Португалия).

Лучший гол чемпионата мира

В списке голосования участвовало 18 голов, среди которых также были голы игроков сборной России Дениса Черышева и Артема Дзюбы.

Лучшим голом на турнире признан гол защитника сборной Франции Бенжамена Павара в ворота сборной Аргентины (4:3) в матче 1/8 финала ЧМ-2018.

См. также статьи:

Чемпионаты мира по футболу:

- Впервые в истории проведения чемпионатов мира в турнире приняли участие все 210 национальных ассоциаций, входящих в состав ФИФА.

- В рейтинге ФИФА, опубликованном за неделю до начала чемпионата мира сборная России занимала рекордно низкое место — 70-е, пропустив вперед сборную Саудовской Аравии, с которой они играли в одной группе на предварительном этапе.

- Единственным футболистом на планете, который трижды становился чемпионом мира по футболу, до сих пор остается легендерный бразильский футболист Пеле.

- Нападающий сборной России Олег Саленко является единственным в мире футболистом, сумевшим забить пять голов в одном матче. Это произошло на ЧМ-1994, когда ему удался пента-трик в ворота сборной Камеруна.

- Самым возрастным футболистом, когда-либо игравшим в финальных стадиях чемпионатов мира является колумбийский голкипер Мондрагон. Он вышел на поле в матче с Японией на ЧМ-2014 в возрасте 43 лет и трех дней. Но этот рекорд был побит на этом чемпионате, т.к. в играх турнира принял участие голкипер сборной Египта Эссаму Эль-Хадари, которому уже исполнилось 45 лет и почти пять месяцев!

- Впервые в истории проведения чемпионатов мира на этом турнире была использована система видеопомощи арбитрам (VAR), которая впервые на высшем уровне была обкатана на Кубке Конфедераций, проходившем также в России летом 2017 года.

- На третьем подряд чемпионате мира действующий чемпион мира не смог преодолеть стадию группового этапа. На этом турнире сборная Германии, действующий чемпион мира не смогла пробиться в стадию плей-офф. На чемпионате мира 2014 года из группы не вышла сборная Испании, а на чемпионате мира 2010 года – сборная Италии.

- После победы в серии послематчевых пенальти над сборной Испании национальная сборная России впервые в своей футбольной истории пробилась в 1/4 финала чемпионата.

- Так как после окончания четвертьфинальных матчей среди команд, претендующих на победу остались только сборные, представляющие Европу, нынешний чемпионат стал четвертым подряд, в котором чемпионский титул завоевала европейская сборная.

- Получение Россией права на проведение ЧМ-2018 по футболу //РИА Новости

- Постановление Правительство Российской Федерации от 20 июня 2013 г. № 518 «О Программе подготовки к проведению в 2018 году в Российской Федерации чемпионата мира по футболу» // Правительство Российской Федерации. 20 июня 2013 г.

- Представлена официальная эмблема чемпионата мира 2018 в России. //championat.com 29.10.2014 г.

- Выбрано 10 персонажей для талисмана ЧМ-2018 //championat.com 1.07.2015 г.

- Состоялась жеребьёвка европейской квалификации чемпионата мира — 2018 //championat.com 25.07.2015 г.

- ФИФА назвала города проведения первых матчей сборной России на ЧМ-2018 //rbc.ru 24.07.2015 г.

- Волк по имени Забивака стал талисманом чемпионата мира 2018 года //www.championat.com 22 октября 2016 г.

- Волк выбран официальным талисманом чемпионата мира по футболу 2018 года и назван Забивака //fifa.com 22 октября 2016 г.

- Официальный сайт ФИФА представил биографию талисмана ЧМ-2018 //championat.com 22 октября 2016

- Все талисманы чемпионатов мира по футболу (фотогалерея) //rbc.ru 22 октября 2016 г.

- Центральный банк России выпустил посвященные чемпионату мира-2018 монеты //rbc.ru 21 декабря 2016 г.

- Стали известны все 32 участника чемпионата мира- 2018 в России //championat.com 16 ноября 2017 г.

- Сборная России – худшая команда по рейтингу среди всех участников ЧМ-2018 //championat.com 16 ноября 2017 г

- Итоги жеребьёвки ЧМ-2018 по футболу //championat.com 1 декабря 2017 г

- Полное расписание всех матчей группового этапа ЧМ-2018 //championat.com 1 декабря 2017 г.

- Черчесов назвал расширенный состав сборной России для подготовки к ЧМ-2018 //championat.com 11 мая 2018 г.

- Игнашевич вызван в сборную России вместо Камболова //championat.com 14 мая 2018 г.

- ФИФА объявила девизы сборных команд на чемпионате мира //sportrbc.ru 24 мая 2018 г.

- ФИФА представила официальную заставку чемпионата мира 2018 года //Официальный канал ФИФА в YouTube.1 июня 2018 г.

- Состав сборной России по футболу на чемпионат мира — 2018 //championat.com 3 июня 2018 г.

- Сборная России установила антирекорд в рейтинге ФИФА //sportrbc.ru 7 июня 2018 г

- Чемпионат мира по футболу 2026 пройдет в США, Канаде и Мексике //championat.com 13 июня 2018 г.

- Сборная России обыграла Испанию в серии пенальти и вышла в 1/4 финала ЧМ-2018 //championat.com 1 июля 2018 г.

- Чемпионом мира по футболу 2018 года стала сборная Франции //Российская газета 15 июля 2018 г.

- Гол Павара в ворота сборной Аргентины был признан лучшим на ЧМ-2018 //championat.com 25 июля 2018 г.

- ФИФА объявила символическую сборную чемпионата мира-2018 по версии болельщиков //championat.com 25 июля 2018 г.

- Официальный сайт FIFA (англ, фр, нем, исп, порт)

- Страница Чемпионата мира по футболу 2018 на сайте FIFA

ЧМ для «чайников». Всё, что нужно знать о грандиозном турнире в России

Если вы знаете, кто такие Месси и Роналду, — этот текст не для вас. Здесь ликбез для тех, кто слово футбол употребляет очень редко.

Прочитайте и сможете поддержать разговор о футболе в любое время и в любом месте. Потому что целый месяц говорить будут только о нём.

Первый чемпионат мира в России

Начнём с главного. Чемпионат мира по футболу – один из двух главных спортивных турниров во всём мире наряду с Олимпийскими играми. Суммарная аудитория чемпионатов мира в XXI веке стабильно переваливает за три миллиарда человек, а, например, финальный матч чемпионата мира 2014 года, в котором сыграли сборные Германии и Аргентины, посмотрело более миллиарда зрителей. То есть каждый восьмой человек на планете, включая младенцев и стариков!

Чемпионат мира традиционно проводится раз в четыре года начиная с 1930-го. В 1942 и 1946 годах соревнования не проводились из-за Второй мировой войны. Турнир 2018 года, таким образом, станет 21-м в истории. И первым, который пройдёт на территории нашей страны.

В 1930 году Международная федерация футбола (ФИФА) просто пригласила всех желающих принять участие в турнире. В Уругвай, где проходили соревнования, приехали лишь 13 сборных. Хозяева и стали победителями турнира, выиграв финальный матч у Аргентины – 4:2.

С 1934 года количество команд, готовых принять участие в турнире, возрастало. ФИФА приняла решение определить формат турнира и проводить отборочные матчи, чтобы определять команды, достойные принять участие в соревнованиях. В 1934 году, например, в отборе принимали участие 32 сборных, 16 из которых попадали в финальную стадию. 84 года спустя цифры несколько изменились: в оборочных соревнованиях, которые продолжались два года, участвовали 207 сборных, сражавшихся за 31 путёвку. 32-е место получила страна-хозяйка – Россия.

За всю историю проведения чемпионатов мира лишь восемь сборных выигрывали титул. Бразилия получала кубок пять раз, Германия и Италия – по четыре. Также чемпионами мира становились Аргентина, Уругвай, Франция, Испания и Англия. Высшее достижение футболистов из нашей страны – четвёртое место команды Советского Союза на турнире 1966 года.

Единственный трёхкратный чемпион мира по футболу в истории – великий бразилец Пеле, который вместе с командой побеждал на турнирах 1958, 1962 и 1970 годов. Ещё 20 футболистов (15 бразильцев, четыре итальянца и аргентинец) становились чемпионами дважды.

Россияне проведут три матча. Или больше?

От российской команды перед стартом чемпионата мира, как правило, не ждут многого, но тем приятнее могут быть сюрпризы, которая сборная России преподнесёт болельщикам. Что касается неумолимых цифр и исторических фактов, то они на оптимистичный лад не настраивают. Сборная России, выступавшая на трёх чемпионатах мира — в 1994, 2002 и 2014 годах – ни разу не выходила из группы, хотя с соперниками нашей команде при жеребьёвке, как правило, везло.

К чемпионату мира 2018 года сборная России подходит на 70-м месте в рейтинге ФИФА. Это худший показатель среди всех стран — участниц турнира. Правда, стоит помнить, что страна-хозяйка всегда проседает в табели о рангах, поскольку не выступает в отборочном турнире.

Главный тренер национальной сборной – Станислав Черчесов, работающий с российской командой с 2016 года. Капитан команды – вратарь Игорь Акинфеев. Средний возраст команды – 28,3 года. Это чуть меньше, чем было в 2016 году на чемпионате Европы, но всё равно немало. Для сравнения: средний возраст немцев – 25,7 лет, бразильцев – 27,8, испанцев – 28,0.

Самый возрастной и опытный игрок сборной России – 38-летний защитник Сергей Игнашевич. Когда он дебютировал за сборную, его нынешний партнёр по сборной 22-летний Александр Головин, играющий на позиции полузащитника, ещё не пошёл в школу.

В российской сборной больше всего футболистов из «Зенита» и ЦСКА – шестеро и пятеро соответственно. «Спартак», «Локомотив», «Краснодар», «Рубин» и «Ахмат» отправили в сборную трёх игроков или меньше. Также в составе есть два футболиста, выступающих за рубежом: Владимир Габулов из бельгийского «Брюгге» и Денис Черышев из испанского «Вильярреала».

Последние результаты сборной России вряд ли могут порадовать поклонников команды. Россияне не смогли выиграть в семи последних товарищеских матчах. Последняя победа была одержана в октябре 2017-го в матче со сборной Южной Кореи. Что касается официальных матчей, то летом прошлого года Россия выступала на домашнем Кубке конфедераций. Обыграла Новую Зеландию, но уступила Португалии и Мексике и не смогла выйти из группы.

На чемпионате мира сборной России предстоит провести как минимум три матча — 14 июня в Москве с Саудовской Аравией, 19 июня в Санкт-Петербурге с Египтом и 25 июня в Самаре с Уругваем. Если по итогам этих матчей Россия выйдет из группы, то следующий матч проведёт 30 июня или 1 июля с кем-то из группы В. Вероятно, Испанией или Португалией.

11 городов, 12 стадионов, 5 фаворитов

Формат чемпионата мира максимально прост и всем привычен, поскольку не менялся уже 20 лет. В соревнованиях принимают участие 32 команды. На первом этапе все они жребием разделены на восемь квартетов. В этих группах по четыре сборные сыграют друг с другом по разу. Команды, занявшие два первых места, выйдут в плей-офф. Регламент матчей на вылет максимально прост: в следующий раунд проходит только победитель матча. Если основное время игры завершается вничью, игра продолжается ещё два тайма по 15 минут. Если и в овертайме ни одна из команд не смогла вырвать победу, то судьбу встречи решит серия послематчевых пенальти.

Первый матч чемпионата мира в России будет проведён 14 июня – в Москве на стадионе «Лужники» российская команда сыграет со сборной Саудовской Аравии. Заключительные матчи группового этапа будут сыграны 28 июня. А уже через день, 30 июня, в Сочи и Казани стартуют встречи 1/8 финала чемпионата мира. Решающий матч турнира, который определит новых чемпионов мира, будет проведён 15 июля – также в московских «Лужниках».

Матчи чемпионата мира будут проходить на 12 стадионах, построенных или реконструированных в 11 городах России. Самый вместительный стадион – столичные «Лужники» (вмещает 80 тыс. зрителей). Самый дорогой – «Стадион Санкт-Петербург» в Северной столице, на строительство которого ушло около 43 млрд рублей. Также матчи пройдут в Екатеринбурге, Волгограде, Самаре, Нижнем Новгороде, Ростове-на-Дону, Калининграде, Сочи, Казани и Саранске.

Кто выиграет чемпионат мира, разумеется, заранее предсказать невозможно. Этот турнир всегда дарит зрителям целую россыпь неожиданных результатов и футбольных открытий. Однако пятёрку фаворитов назвать всё же можно: сборные Германии, Бразилии, Испании, Франции и Аргентины, по мнению экспертов, имеют наибольшие шансы на победу в турнире.

«FIFA 2018» redirects here. For the video game, see FIFA 18.

| Чемпионат мира по футболу FIFA 2018 Chempionat mira po futbolu FIFA 2018 |

|

|---|---|

Играй с открытым сердцем |

|

| Tournament details | |

| Host country | Russia |

| Dates | 14 June – 15 July 2018 |

| Teams | 32 (from 5 confederations) |

| Venue(s) | 12 (in 11 host cities) |

| Final positions | |

| Champions | |

| Runners-up | |

| Third place | |

| Fourth place | |

| Tournament statistics | |

| Matches played | 64 |

| Goals scored | 169 (2.64 per match) |

| Attendance | 3,031,768 (47,371 per match) |

| Top scorer(s) | |

| Best player(s) | |

| Best young player | |

| Best goalkeeper | |

| Fair play award | |

|

← 2014 2022 → |

The 2018 FIFA World Cup was the 21st FIFA World Cup, the quadrennial world championship for national football teams organized by FIFA. It took place in Russia from 14 June to 15 July 2018, after the country was awarded the hosting rights in 2010. It was the eleventh time the championships had been held in Europe, and the first time they were held in Eastern Europe. At an estimated cost of over $14.2 billion, it was the most expensive World Cup ever held until it was surpassed by the 2022 World Cup in Qatar.[1][2]

The tournament phase involved 32 teams, of which 31 came through qualifying competitions, while as the host nation Russia qualified automatically. Of the 32, 20 had also appeared in the 2014 event, while Iceland and Panama each made their first appearance at the World Cup. 64 matches were played in 12 venues across 11 cities. Germany, the defending champions, were eliminated in the group stage for the first time since 1938. Host nation Russia was eliminated in the quarter-finals. In the final, France played Croatia on 15 July at the Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow. France won the match 4–2, claiming their second World Cup and becoming the fourth consecutive title won by a European team, after Italy in 2006, Spain in 2010, and Germany in 2014.

Croatian player Luka Modrić was voted the tournament’s best player, winning the Golden Ball. England’s Harry Kane won the Golden Boot as he scored the most goals during the tournament with six. Belgium’s Thibaut Courtois won the Golden Glove, awarded to the goalkeeper with the best performance. It has been estimated that more than 3 million people attended games during the tournament.

Host selection[edit]

Russian bid personnel celebrate the awarding of the 2018 World Cup to Russia on 2 December 2010.

The 100-ruble commemorative banknote celebrates the 2018 FIFA World Cup. It features an image of Soviet goalkeeper Lev Yashin.

The bidding procedure to host the 2018 and 2022 FIFA World Cup tournaments began in January 2009, and national associations had until 2 February 2009 to register their interest.[3] Initially, nine countries placed bids for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, but Mexico later withdrew from the proceedings,[4] and Indonesia’s bid was rejected by FIFA in February 2010 after the Indonesian government failed to submit a letter to support the bid.[5] During the bidding process, the three remaining non-UEFA nations (Australia, Japan, and the United States) gradually withdrew from the 2018 bids, and thus were ruled out of the 2022 bid. As such, there were eventually four bids for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, two of which were joint bids: England, Russia, Netherlands/Belgium, and Portugal/Spain.[6]

The 22-member FIFA Executive Committee convened in Zürich on 2 December 2010 to vote to select the hosts of both tournaments.[7] Russia won the right to be the 2018 host in the second round of voting. The Portugal/Spain bid came second, and that from Belgium/Netherlands third. England, which was bidding to host its second tournament, was eliminated in the first round.[8]

The voting results were:[6]

| Bidders | Votes | |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |

| Russia | 9 | 13 |

| Portugal / Spain | 7 | 7 |

| Belgium / Netherlands | 4 | 2 |

| England | 2 | Eliminated |

Host selection criticism[edit]

The choice of Russia as host was controversial. Issues included the level of racism in Russian football,[9][10][11] human rights abuses by Russian authorities,[12][13] and discrimination against LGBT people in wider Russian society.[14][15] Russia’s involvement in the ongoing conflict in Ukraine had also prompted calls for the tournament to be moved, particularly following the annexation of Crimea.[16][17] In 2014, FIFA president Sepp Blatter stated that «the World Cup has been given and voted to Russia and we are going forward with our work».[18]

Russia was criticised for alleged abuse of migrant labourers in the construction of World Cup venues,[19] with Human Rights Watch reporting cases where workers were left unpaid, made to work in dangerously cold conditions, or suffering reprisals for raising concerns.[20][21] A few pundits claimed it was slave labour.[22][23][24] In May 2017, FIFA president Gianni Infantino admitted there had been human rights abuses of North Korean workers involved in the construction of Saint Petersburg’s Zenit Arena.[25] By June 2017, at least 17 workers had died on World Cup construction sites, according to Building and Wood Workers’ International.[26][27] In August, a group of eight US senators called on FIFA to consider dismissing Russia as the World Cup host if an independent investigation verified allegations of North Koreans being subjected to forced labor.[28]

Racism and Neo-nazi symbols displayed in the past by some Russian football fans drew criticism,[29] with documented incidents of racial chants, banners spewing hate-filled messages, and sometimes assaults on people from the Caucasus and Central Asia.[30][31] In March 2015, FIFA’s then Vice President Jeffrey Webb said that Russia posed a huge challenge from a racism standpoint, and that a World Cup could not be held there under the current conditions.[32] On July, United Nations anti-discrimination official Yuri Boychenko said that Russian soccer authorities had failed to fully grasp what racism was and needed to do more to combat it.[33] To address this as well as concerns of hooliganism in general, Russian intelligence services blacklisted over 400 fans from entering the stadiums by June 2018, with 32 other countries also sending officers to help local police screen attendees for valid ID cards.[34]

Allegations of corruption in the bidding processes and concerns over bribery on the part of the Russian team and corruption by FIFA members for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups led to threats from England’s FA to boycott the tournament.[35] They claimed that four members of the executive committee had requested bribes to vote for England, and Sepp Blatter had said it had already been arranged before the vote that Russia would win.[36] FIFA appointed Michael J. Garcia, a US attorney, to investigate and produce a report on the corruption allegations. Although the report was never published, FIFA released a 42-page summary of its findings as determined by German judge Hans-Joachim Eckert. Eckert’s summary cleared Russia and Qatar of any wrongdoing, but was denounced by critics as a whitewash.[37] Because of the controversy, the FA refused to accept Eckert’s absolving Russia from blame. Greg Dyke called for a re-examination of the affair and David Bernstein called for a boycott of the World Cup.[38][39] Garcia criticised the summary as being «materially incomplete» with «erroneous representations of the facts and conclusions», and appealed to FIFA’s Appeal Committee.[40][41] The committee declined to hear his appeal, so Garcia resigned to protest of FIFA’s conduct, citing a «lack of leadership» and lack of confidence in Eckert’s independence.[42]

On 3 June 2015, the FBI confirmed that federal authorities were investigating the bidding and awarding processes for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups.[43][44] In an interview published on 7 June 2015, Domenico Scala, the head of FIFA’s Audit And Compliance Committee, stated that «should there be evidence that the awards to Qatar and Russia came only because of bought votes, then the awards could be cancelled».[45][46] Prince William of Wales and former British Prime Minister David Cameron attended a meeting with FIFA vice-president Chung Mong-joon in which a vote-trading deal for the right to host the 2018 World Cup in England was discussed.[47][48]

Teams[edit]

Qualification[edit]

For the first time in the history of the FIFA World Cup, all eligible nations—the 209 FIFA member associations except automatically qualified hosts Russia—applied to enter the qualifying process.[49] Zimbabwe and Indonesia were later disqualified before playing their first matches,[50][51] while Gibraltar and Kosovo, who joined FIFA on 13 May 2016 after the qualifying draw but before European qualifying had begun, also entered the competition.[citation needed] Places in the tournament were allocated to continental confederations, with the allocation unchanged from the 2014 World Cup.[52][53] The first qualification game, between Timor-Leste and Mongolia, began in Dili on 12 March 2015 as part of the AFC’s qualification,[54][55][56] and the main qualifying draw took place at the Konstantinovsky Palace in Strelna, Saint Petersburg, on 25 July 2015.[57][58]

Of the 32 nations qualified to play at the 2018 FIFA World Cup, 20 countries competed at the previous tournament in 2014. Both Iceland and Panama qualified for the first time, with the former becoming the smallest country in terms of population to reach the World Cup.[59] Other teams returning after absences of at least three tournaments included: Egypt, returning to the finals after their last appearance in 1990; Morocco, who last competed in 1998; Peru, who last appeared in 1982; and Senegal, competing for the second time after reaching the quarter-finals in 2002. It was the first time three Nordic countries (Denmark, Iceland and Sweden) and four Arab nations (Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia) qualified for the World Cup.[60]

Notable teams that failed to qualify included: four-time champions Italy (for the first time since 1958), who were knocked out in a qualification play-off by quarter-finalists Sweden and were the highest-ranked team to not qualify; and the Netherlands, who were three-time runners-up and had finished in third place in 2014, and had qualified for the last three World Cups. Four reigning continental champions: 2017 Africa Cup of Nations winners Cameroon; two-time Copa América champions and 2017 Confederations Cup runners-up Chile; 2016 OFC Nations Cup winners New Zealand; and 2017 CONCACAF Gold Cup champions the United States (for the first time since 1986) also failed to qualify. The other notable qualifying streaks broken were for Ghana and Ivory Coast, both of which had qualified for the three previous tournaments.[61] The lowest-ranked team to qualify was the host nation, Russia.

Note: Numbers in parentheses indicate positions in the FIFA World Rankings at the time of the tournament.[62]

Draw[edit]

The draw was held on 1 December 2017 at 18:00 MSK at the State Kremlin Palace in Moscow.[63][64] The 32 teams were drawn into eight groups of four, by selecting one team from each of the four ranked pots.

For the draw, the teams were allocated to four pots based on the FIFA World Rankings of October 2017. Pot one contained the hosts Russia (who were automatically assigned to position A1) and the best seven teams. Pot two contained the next best eight teams, and so on for pots three and four.[65] This was different from previous draws, when only pot one was based on FIFA rankings while the remaining pots were based on geographical considerations. However, teams from the same confederation still were not drawn against each other for the group stage, except that two UEFA teams could be in each group. The pots for the draw are shown below.[66]

| Pot 1 | Pot 2 | Pot 3 | Pot 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Squads[edit]

Initially, each team had to name a preliminary squad of 30 players, but in February 2018 this was increased to 35.[67] From the preliminary squad, the team had to name a final squad of 23 players (three of whom had to be goalkeepers) by 4 June. Players in the final squad could be replaced for serious injury up to 24 hours prior to kickoff of the team’s first match. These replacements did not need to have been named in the preliminary squad.[68]

For players named in the 35-player preliminary squad, there was a mandatory rest period between 21 and 27 May 2018, except for those involved in the 2018 UEFA Champions League Final played on 26 May.[69]

Officiating[edit]

On 29 March 2018, FIFA released the list of 36 referees and 63 assistant referees selected to oversee matches.[70] On 30 April 2018, FIFA released the list of 13 video assistant referees, who acted solely in this capacity in the tournament.[71]

Referee Fahad Al-Mirdasi of Saudi Arabia was removed on 30 May 2018 over a match-fixing attempt,[72] along with his two assistant referees, compatriots Mohammed Al-Abakry and Abdulah Al-Shalwai. A new referee was not appointed, but two assistant referees, Hasan Al Mahri of the United Arab Emirates and Hiroshi Yamauchi of Japan, were added to the list.[73][74] Assistant referee Marwa Range of Kenya also withdrew after the BBC released an investigation conducted by a Ghanaian journalist which implicated him in a bribery scandal.[75]

| List of officials | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Confederation | Referee | Assistant referees | Video assistant referees |

| AFC | Alireza Faghani (Iran) | Reza Sokhandan (Iran) Mohammadreza Mansouri (Iran) |

Abdulrahman Al-Jassim (Qatar) |

| Ravshan Irmatov (Uzbekistan) | Abdukhamidullo Rasulov (Uzbekistan) Jakhongir Saidov (Uzbekistan) |

||

| Mohammed Abdulla Hassan Mohamed (United Arab Emirates) | Mohamed Al Hammadi (United Arab Emirates) Hasan Al Mahri (United Arab Emirates) |

||

| Ryuji Sato (Japan) | Toru Sagara (Japan) Hiroshi Yamauchi (Japan) |

||

| Nawaf Shukralla (Bahrain) | Yaser Tulefat (Bahrain) Taleb Al Maari (Qatar) |

||

| CAF | Mehdi Abid Charef (Algeria) | Anouar Hmila (Tunisia) | |

| Malang Diedhiou (Senegal) | Djibril Camara (Senegal) El Hadji Samba (Senegal) |

||

| Bakary Gassama (Gambia) | Jean Claude Birumushahu (Burundi) Abdelhak Etchiali (Algeria) |

||

| Gehad Grisha (Egypt) | Redouane Achik (Morocco) Waleed Ahmed (Sudan) |

||

| Janny Sikazwe (Zambia) | Jerson Dos Santos (Angola) Zakhele Siwela (South Africa) |

||

| Bamlak Tessema Weyesa (Ethiopia) | |||

| CONCACAF | Joel Aguilar (El Salvador) | Juan Zumba (El Salvador) Juan Carlos Mora (Costa Rica) |

|

| Mark Geiger (United States) | Frank Anderson (United States) Joe Fletcher (Canada) |

||

| Jair Marrufo (United States) | Corey Rockwell (United States) | ||

| Ricardo Montero (Costa Rica) | |||

| John Pitti (Panama) | Gabriel Victoria (Panama) | ||

| César Arturo Ramos (Mexico) | Marvin Torrentera (Mexico) Miguel Hernández (Mexico) |

||

| CONMEBOL | Julio Bascuñán (Chile) | Carlos Astroza (Chile) Christian Schiemann (Chile) |

Wilton Sampaio (Brazil) Gery Vargas (Bolivia) Mauro Vigliano (Argentina) |

| Enrique Cáceres (Paraguay) | Eduardo Cardozo (Paraguay) Juan Zorrilla (Paraguay) |

||

| Andrés Cunha (Uruguay) | Nicolás Taran (Uruguay) Mauricio Espinosa (Uruguay) |

||

| Néstor Pitana (Argentina) | Hernán Maidana (Argentina) Juan Pablo Belatti (Argentina) |

||

| Sandro Ricci (Brazil) | Emerson de Carvalho (Brazil) Marcelo Van Gasse (Brazil) |

||

| Wilmar Roldán (Colombia) | Alexander Guzmán (Colombia) Cristian de la Cruz (Colombia) |

||

| OFC | Matthew Conger (New Zealand) | Simon Lount (New Zealand) Tevita Makasini (Tonga) |

|

| Norbert Hauata (Tahiti) | Bertrand Brial (New Caledonia) | ||

| UEFA | Felix Brych (Germany) | Mark Borsch (Germany) Stefan Lupp (Germany) |

Bastian Dankert (Germany) Artur Soares Dias (Portugal) Paweł Gil (Poland) Massimiliano Irrati (Italy) Tiago Martins (Portugal) Danny Makkelie (Netherlands) Daniele Orsato (Italy) Paolo Valeri (Italy) Felix Zwayer (Germany) |

| Cüneyt Çakır (Turkey) | Bahattin Duran (Turkey) Tarık Ongun (Turkey) |

||

| Sergei Karasev (Russia) | Anton Averianov (Russia) Tikhon Kalugin (Russia) |

||

| Björn Kuipers (Netherlands) | Sander van Roekel (Netherlands) Erwin Zeinstra (Netherlands) |

||

| Szymon Marciniak (Poland) | Paweł Sokolnicki (Poland) Tomasz Listkiewicz (Poland) |

||

| Antonio Mateu Lahoz (Spain) | Pau Cebrián Devís (Spain) Roberto Díaz Pérez (Spain) |

||

| Milorad Mažić (Serbia) | Milovan Ristić (Serbia) Dalibor Đurđević (Serbia) |

||

| Gianluca Rocchi (Italy) | Elenito Di Liberatore (Italy) Mauro Tonolini (Italy) |

||

| Damir Skomina (Slovenia) | Jure Praprotnik (Slovenia) Robert Vukan (Slovenia) |

||

| Clément Turpin (France) | Cyril Gringore (France) Nicolas Danos (France) |

Video assistant referees[edit]

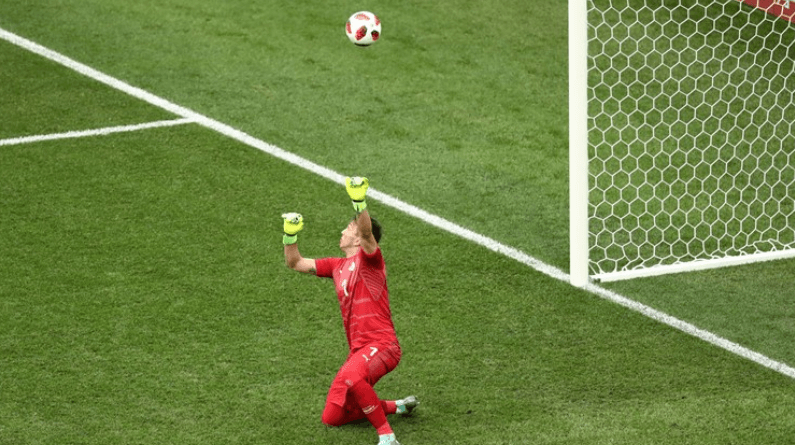

Shortly after the International Football Association Board’s decision to incorporate video assistant referees (VARs) into the Laws of the game (LOTG) on 16 March 2018, the FIFA Council took the much-anticipated step of approving the use of VAR for the first time in a FIFA World Cup tournament.[76][77]

VAR operations for all games were operated from a single headquarters in Moscow, which received live video of the games and were in radio contact with the on-field referees.[78] Systems were in place for communicating VAR-related information to broadcasters and visuals on stadiums’ large screens were used for the fans in attendance.[78]

VAR had a significant impact on several games.[79] On 15 June 2018, Diego Costa’s first goal against Portugal became the first World Cup goal based on a VAR decision;[80] the first penalty as a result of a VAR decision was awarded to France in their match against Australia on 16 June and resulted in a goal by Antoine Griezmann.[81] A record number of penalties were awarded in the tournament, a phenomenon partially attributed to VAR.[82] Overall, the new technology was both praised and criticised by commentators.[83] FIFA declared the implementation of VAR a success after the first week of competition.[84]

Venues[edit]

Russia proposed the following host cities: Kaliningrad, Kazan, Krasnodar, Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Rostov-on-Don, Saint Petersburg, Samara, Saransk, Sochi, Volgograd, Yaroslavl, and Yekaterinburg.[85] Each chosen city was located in European Russia (except Yekaterinburg,[86] which lies very close to the Europe-Asia border) in order to reduce travel time for the teams in the huge country. The bid evaluation report stated: «The Russian bid proposes 13 host cities and 16 stadiums, thus exceeding FIFA’s minimum requirement. Three of the 16 stadiums would be renovated, and 13 would be newly constructed.»[87]

In October 2011, Russia reduced the number of stadiums from 16 to 14. Construction of the proposed Podolsk stadium in the Moscow Oblast was cancelled by the regional government. Also, in the capital, Otkritie Arena was competing with Dynamo Stadium over which would be constructed first.[88][dead link]

The final choice of host cities was announced on 29 September 2012. The number of cities was reduced further to 11 and the number of stadiums to 12 as Krasnodar and Yaroslavl were dropped from the final list. Of the 12 stadiums used for the tournament, three (Luzhniki, Yekaterinburg and Sochi) had been extensively renovated and the other nine were brand new; $11.8 billion was spent on hosting the tournament.[89]

Sepp Blatter had said in July 2014 that, given the concerns over the completion of venues in Russia, the number of venues for the tournament may be reduced from 12 to 10.[90] He also said, «We are not going to be in a situation, as is the case of one, two or even three stadiums in South Africa, where it is a problem of what you do with these stadiums».[91]

Reconstruction of the Yekaterinburg Central Stadium in January 2017

In October 2014, on their first official visit to Russia, FIFA’s inspection committee and its head, Chris Unger, visited St. Petersburg, Sochi, Kazan and both Moscow venues. They were satisfied with the progress.[92] On 8 October 2015, FIFA and the local organising committee agreed on the official names of the stadiums to be used during the tournament.[93] Of the twelve venues, the Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow and the Saint Petersburg Stadium—the two largest stadiums in Russia—were used most; both hosted seven matches. Sochi, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod and Samara each hosted six matches, including one quarter-final match each, while the Otkritie Stadium in Moscow and the Rostov Stadium hosted five matches, including one round-of-16 match each. Volgograd, Kaliningrad, Yekaterinburg and Saransk each hosted four matches, but did not host any knockout stage games.

Stadiums[edit]

Exterior of Otkrytie Arena

in Moscow

Twelve stadiums in eleven Russian cities were built or renovated for the FIFA World Cup. Between 2010 (when Russia were announced as hosts) and 2018, nine of the twelve stadiums were built (some in place of older, outdated venues) and the other three were renovated for the tournament.[94]

- Kaliningrad: Kaliningrad Stadium (new). The first piles were driven into the ground in September 2015. On 11 April 2018 it hosted its first match.

- Kazan: Kazan Arena (new). The stadium was built for the 2013 Summer Universiade. It has since hosted the 2015 World Aquatics Championships and the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup. It serves as a home arena for FC Rubin Kazan.

- Moscow: Luzhniki Stadium (heavily renovated). The largest stadium in the country, it was closed for renovation in 2013. It was commissioned in November 2017.

- Moscow: Spartak Stadium (new). This stadium is the home arena to its namesake FC Spartak Moscow. In accordance with FIFA requirements, during the 2018 World Cup, it was called Spartak Stadium instead of its usual name Otkritie Arena. It hosted its first match on 5 September 2014.

- Nizhny Novgorod: Nizhny Novgorod Stadium (new). Construction of this stadium commenced in 2015 and was completed in December 2017.[95]

- Rostov-on-Don: Rostov Arena (new). The stadium is located on the left bank of the Don. Construction was completed on 22 December 2017.

- Saint Petersburg: Saint Petersburg Stadium (new). Construction commenced in 2007 after the site, formerly occupied by Kirov Stadium, was cleared. The project was officially completed on 29 December 2016.[96] It has hosted 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup games and served as a venue for UEFA Euro 2020.

- Samara: Samara Arena (new). Construction officially started on 21 July 2014 and was completed on 21 April 2018.

- Saransk: Mordovia Arena (new). The stadium in Saransk was scheduled to be commissioned in 2012 in time for the opening of the all-Russian Spartakiad, but the plan was revised. The opening was rescheduled to 2017. The arena hosted its first match on 21 April 2018.

- Sochi: Fisht Stadium (slightly renovated). This stadium hosted the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2014 Winter Olympics. Afterwards, it was renovated in preparation for the 2017 FIFA Confederations Cup and the 2018 World Cup.

- Volgograd: Volgograd Arena (new). The main Volgograd arena was built on the demolished Central Stadium site, at the foot of the Mamayev Kurgan memorial complex. It was commissioned on 3 April 2018.[97]

- Yekaterinburg: Ekaterinburg Arena (heavily renovated). The Central Stadium of Yekaterinburg had been renovated for the FIFA World Cup. Its stands have a capacity of 35,000 spectators. The renovation project was completed in December 2017.

| Moscow | Saint Petersburg | Sochi | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luzhniki Stadium | Otkritie Arena (Spartak Stadium) |

Krestovsky Stadium (Saint Petersburg Stadium) |

Fisht Olympic Stadium (Fisht Stadium) |

| Capacity: 78,011[98] | Capacity: 44,190[99] | Capacity: 64,468[100] | Capacity: 44,287[101] |

|

|

|

|

| Volgograd |

Moscow Saint Petersburg Kaliningrad Nizhny Novgorod Kazan Samara Volgograd Saransk Sochi Rostov-on-Don Yekaterinburg |

Rostov-on-Don | |

| Volgograd Arena | Rostov Arena | ||

| Capacity: 43,713[102] | Capacity: 43,472[103] | ||

|

|

||

| Nizhny Novgorod | Kazan | ||

| Nizhny Novgorod Stadium | Kazan Arena | ||

| Capacity: 43,319[104] | Capacity: 42,873[105] | ||

|

|

||

| Samara | Saransk | Kaliningrad | Yekaterinburg |

| Samara Arena | Mordovia Arena | Kaliningrad Stadium | Central Stadium (Ekaterinburg Arena) |

| Capacity: 41,970[106] | Capacity: 41,685[107] | Capacity: 33,973[108] | Capacity: 33,061[109] |

|

|

|

|

Team base camps[edit]

Base camps were used by the 32 national squads to stay and train before and during the World Cup tournament. On 9 February 2018, FIFA announced the base camps for each participating team.[110]

- Argentina: Bronnitsy, Moscow Oblast

- Australia: Kazan, Tatarstan

- Belgium: Krasnogorsky, Moscow Oblast

- Brazil: Sochi, Krasnodar Krai

- Colombia: Verkhneuslonsky, Tatarstan

- Costa Rica: Saint Petersburg

- Croatia: Roshchino, Leningrad Oblast[111]

- Denmark: Anapa, Krasnodar Krai

- Egypt: Grozny, Chechnya

- England: Repino, Saint Petersburg[112]

- France: Istra, Moscow Oblast

- Germany: Vatutinki, Moscow[113]

- Iceland: Gelendzhik, Krasnodar Krai

- Iran: Bakovka, Moscow Oblast

- Japan: Kazan, Tatarstan

- Mexico: Khimki, Moscow Oblast

- Morocco: Voronezh, Voronezh Oblast

- Nigeria: Yessentuki, Stavropol Krai

- Panama: Saransk, Mordovia

- Peru: Moscow

- Poland: Sochi, Krasnodar Krai

- Portugal: Ramenskoye, Moscow Oblast

- Russia: Khimki, Moscow Oblast

- Saudi Arabia: Saint Petersburg

- Senegal: Kaluga, Kaluga Oblast

- Serbia: Svetlogorsk, Kaliningrad Oblast

- South Korea: Saint Petersburg

- Spain: Krasnodar, Krasnodar Krai

- Sweden: Gelendzhik, Krasnodar Krai

- Switzerland: Togliatti, Samara Oblast

- Tunisia: Pervomayskoye, Moscow Oblast

- Uruguay: Bor, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast

Preparation and costs[edit]

Budget[edit]

At an estimated cost of over $14.2 billion as of June 2018,[114] the 2018 FIFA event was the most expensive World Cup in history, surpassing the $11.6 billion cost of the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil.[114][115]

The Russian government had originally earmarked a budget of around $20 billion,[116] which was later slashed to $10 billion, for World Cup preparations. Half was spent on transportation infrastructure.[117] As part of the program to prepare for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, a federal sub-program—»Construction and Renovation of Transport Infrastructure»—was implemented with a total budget of ₽352.5 billion (rubles), with ₽170.3 billion coming from the federal budget, ₽35.1 billion from regional budgets, and ₽147.1 billion from investors.[118] The biggest item of federal spending was the aviation infrastructure costing ₽117.8 billion.[119] Construction of new hotels was a crucial area of infrastructure development in World Cup host cities. Costs continued to mount as preparations were underway.[115]

Infrastructure spending[edit]

Platov International Airport in Rostov-on-Don was upgraded with automated air traffic control systems. Modern surveillance, navigation, communication, control, and meteorological support systems were also installed.[120] Koltsovo Airport in Yekaterinburg was upgraded with radio-engineering tools for flight operation and received a second runway. Saransk Airport received a new navigation system; two new hotels were constructed in the city—the Mercure Saransk Centre (Accor Hotels) and Four Points by Sheraton Saransk as well as few other smaller accommodation facilities.[121] In Samara, new tram lines were laid.[122] Khrabrovo Airport in Kaliningrad was upgraded with radio navigation and weather equipment.[123] Renovation and upgraded radio-engineering tools for flight operations was completed in the Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Volgograd, Samara, Yekaterinburg, Kazan and Sochi airports.[120] On 27 March, the Russian Ministry of Construction Industry, Housing and Utilities Sector of reported that all communications within its area of responsibility had been commissioned. The last facility commissioned was a waste treatment station in Volgograd. In Yekaterinburg, where four matches were hosted, hosting costs increased to over ₽7.4 billion, exceeding the ₽5.6 billion rubles originally allocated from the state and regional budget.[124]

Volunteers[edit]

Volunteer flag bearers on the field prior to Belgium’s (flag depicted) group stage match against Tunisia

Volunteer applications to the 2018 Russia Local Organising Committee opened on 1 June 2016. The 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia Volunteer Program received about 177,000 applications,[125] and engaged a total of 35,000 volunteers.[126] They received training at 15 Volunteer Centres of the local organising committee based in 15 universities, and in volunteer centres in the host cities. Preference, especially in key areas, was given to those with knowledge of a foreign language and volunteering experience, but not necessarily to Russian nationals.[127]

Transport[edit]

Free public transport services were offered for ticketholders during the World Cup, including additional trains linking host cities, as well as services such as bus services within them.[128][129][130]

Schedule[edit]

Launching of a 1,000 days countdown in Moscow

The full schedule was announced by FIFA on 24 July 2015 without kick-off times, which were confirmed later.[131][132] On 1 December 2017, following the final draw, FIFA adjusted six kick-off times.[133][134]

Russia was placed in position A1 in the group stage and played in the opening match at the Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow on 14 June against Saudi Arabia, the two lowest-ranked teams of the tournament at the time of the final draw.[135] The Luzhniki Stadium also hosted the second semi-final on 11 July and the final on 15 July. The Krestovsky Stadium in Saint Petersburg hosted the first semi-final on 10 July and the third place play-off on 14 July.[136][52]

Opening ceremony[edit]

The opening ceremony took place on Thursday, 14 June 2018, at the Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow, preceding the opening match of the tournament between hosts Russia and Saudi Arabia.[137][138]

At the start of the ceremony, Russian president Vladimir Putin gave a speech, welcoming the countries of the world to Russia and calling football a uniting force.[139] Brazilian World Cup-winning striker Ronaldo entered the stadium with a child in a Russia jersey.[139] Pop singer Robbie Williams then sang two of his songs solo before he and Russian soprano Aida Garifullina performed a duet.[139] Dancers dressed in the flags of the 32 competing teams appeared carrying a sign with the name of each nation.[139] At the end of the ceremony Ronaldo reappeared with the official match ball which had returned from the International Space Station in early June.[139]

Young participants of the international children’s social programme Football for Friendship from 211 countries and regions took part in the opening ceremony of the FIFA World Cup at the Luzhniki stadium.[140]

Group stage[edit]

Competing countries were divided into eight groups of four teams (groups A to H). Teams in each group played one another in a round-robin, with the top two teams advancing to the knockout stage. Ten European teams and four South American teams progressed to the knockout stage, together with Japan and Mexico.

For the first time since 1938, Germany, the reigning champions, were eliminated in the first round. This was the third consecutive tournament in which the holders were eliminated in the first round, after Italy in 2010 and Spain in 2014. No African team progressed to the second round for the first time since 1982. The fair play criteria came into use for the first time when Japan qualified over Senegal because the team had received fewer yellow cards. Only one match, France versus Denmark, was goalless. Until then there were a record 36 straight games in which at least one goal was scored.[141] All times listed below are local time.[133]

| Tie-breaking criteria for group play |

|---|

The ranking of teams in the group stage was determined as follows:[68][142]

|

Group A[edit]

| Pos | Team

|

Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Pts | Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | +5 | 9 | Advance to knockout stage | |

| 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 4 | +4 | 6 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 | −5 | 3 | ||

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 6 | −4 | 0 |

Group B[edit]

| Pos | Team

|

Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Pts | Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 5 | +1 | 5 | Advance to knockout stage | |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 4 | +1 | 5 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | ||

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | −2 | 1 |

Group C[edit]

| Pos | Team

|

Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Pts | Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | +2 | 7 | Advance to knockout stage | |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | +1 | 5 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | ||

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | −3 | 1 |

Group D[edit]

| Pos | Team

|

Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Pts | Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | +6 | 9 | Advance to knockout stage | |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | −2 | 4 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | −1 | 3 | ||

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | −3 | 1 |

Group E[edit]

| Pos | Team

|

Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GD | Pts | Qualification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | +4 | 7 | Advance to knockout stage | |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 4 | +1 | 5 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | −2 | 3 | ||