История Чингисхана. Походы и завоевания Чингисхана. Как Чингисхан стал завоевателем? Империя Чингисхана. Как Чингисхан объединил монголов? Какие страны покорил Чингисхан? Какую роль Чингисхан сыграл в истории?

Чингисхан – монгольский завоеватель и реформатор, основатель династии Чингизидов и Монгольской империи – крупнейшего в истории государства по площади территории.

Будущий великий завоеватель, носивший прозвище «Сотрясатель Вселенной», при рождении получил имя Темучин(в разных переводах – Тэмуджин, Темучжин). Чингисханом он стал именоваться лишь с 1206 года, когда был уже в возрасте 51 года (или 44 лет).

В годы юности Темучин, будучи мирным кочевником-скотоводом, и подумать не мог, что обстоятельства заставят его стать великим воином и правителем самого крупного государства в истории. А поводом забыть о мирной жизни стала… любовь к прекрасной девушке по имени Бортэ. И борьба с конокрадством. Но обо всем по порядку.

Происхождение, детство и взросление Чингисхана

Темучин родился в 1155 (по другим источникам – в 1162 или 1167) году в долине Делюн-Болдок (предположительно на территории современной России, в 8 километрах к северу от монгольской границы). Отцом Темучина был Есугэй – представитель знатного рода Борджигин и правитель многих монгольских племен.

Мать Темучина – Оэлун, которую Есугэй похитил у соседнего племени меркитов, согласно распространенному степному обычаю. Свое нетипичное для монголов имя Темучин получил в честь татарского вождя Тэмуджина-Угэ, который был побежден и убит Есугэем. Отец Темучина уважал поверженного врага и верил, что вместе с именем к новорожденному мальчику перейдут его сила и храбрость.

В возрасте девяти лет Темучин вместе с отцом отправился в земли их давнего друга – Дэй-Сечена, предводителя племени унгиратов, где был помолвлен с Бортэ, дочерью вождя. По тогдашним обычаям Темучин остался жить у родителей своей невесты, а его отец отправился домой один.

Согласно Сокровенному сказанию, на обратном пути Есугэй, утомленный жаждой, попросил воды у группы татар. Те напоили его, ибо закон гостеприимства в степи был важнее кровной мести. Однако когда Есугэй вернулся домой, он тяжело заболел (по легенде – из-за отравленной воды) и через три дня умер. С этого момента в детстве Темучина начались тяжелые времена.

Новым правителем на месте Есугэя стал его родственник – Таргутай, который опасался мести меркитов за похищение Оэлун, матери Темучина. Новый вождь принял решение забрать весь скот и изгнать вдов и детей Есугэя из племени, дабы отвести от себя гнев мстительных соседей. После этого Темучин вместе с семьей провел несколько лет в степи на грани голодной смерти.

Однако Таргутай опасался, что Темучин, повзрослев, захочет отомстить за такое гнусное предательство, поэтому решил пленить последнего. Темучина схватили и надели на него деревянную колодку с прорезями для головы и рук – с такой колодкой человек не мог самостоятельно ни пить, ни есть, а мог надеяться только на сердобольность прохожих. С колодкой на плечах Темучин прожил до своего пятнадцатилетия.

Но однажды ночью он все-таки сбежал и укрылся под водой в ближайшем озере. Начались поиски, и Темучина, сидящего в воде, заметил батрак по имени Сорган-Шира, но не выдал его, сделав для остальных вид, что там беглеца нет. После окончания поисков Темучин вылез из воды и пришел в дом к батраку, надеясь на дальнейшую помощь в побеге.

Сорган-Шира боялся гнева Таргутая, поэтому он отказал беглецу и хотел прогнать его, однако за Темучина вступились сыновья Соргана и уговорили отца дать ему лошадь и оружие. Годы спустя Темучин даровал этой семье привилегированное положение в своем государстве.

Вернувшись в степь к своей семье, Темучин все еще стеснялся ехать к своей невесте Бортэ, ведь он был теперь нищим (на самом деле Бортэ долгие годы преданно ждала жениха). Он стал заниматься скотоводством и мелкой торговлей, постепенно развивая хозяйство и полюбив мирную жизнь. Однажды неизвестные воры угнали у него всех лошадей, что стало тяжелым ударом для его дела.

Отправившись на поиски, Темучин повстречал парня по имени Боорчу, который бескорыстно согласился помочь. Вместе они смогли выследить и убить конокрадов, вернуть лошадей и взять богатую добычу. Так Темучин обрел первого настоящего друга, который и в дальнейшем был его ближайшим соратником в государственных делах.

Затем Темучин смог наконец приехать к своему тестю Дэй-Сечену и жениться на красавице Бортэ. С этого момента слава Темучина шла по степи впереди него: сын знаменитого воина, переживший вместе с семьей голодные годы в изоляции, сбежавший из плена гнусного тирана, смог все преодолеть и взял в жены дочь благородного хана.

Но дальнейшая судьба будущего Чингисхана вовсе не была простой и безоблачной. Меркиты, все еще желающие мести за похищение Оэлун (а по обычаям великой степи после смерти Есугэя ответственность за его поступки нес старший сын – Темучин), напали на становище Борджигинов и похитили Бортэ. По законам степи конфликт был исчерпан, но Темучин решил во что бы то ни стало вернуть любимую.

В поисках военной поддержки он обратился за помощью к старому другу своего отца Тоорил-хану и к своему знатному другу детства Джамухе. Будучи к тому моменту уже прославленным героем, он получил желаемую поддержку, открыв в себе навыки дипломата. Вместе с союзными войсками Темучин наголову разгромил меркитов недалеко от реки Селенги, обнаружив и качества полководца.

Как Темучин стал Чингисханом

После разгрома меркитов Тоорил-хан вернулся домой, а Темучин и Джамуха разделили власть в общем улусе. В своих племенах Темучин стремился устроить новый порядок и покончить с обычаями бандитизма, грабежей, конокрадства и предательства. Он ввел новые законы, по которым за эти преступления предусматривалась смертная казнь.

Однажды Тайчар – младший брат Джамухи – угнал лошадей у подданных Темучина, за что был схвачен и по новому закону казнен. Разгневанный Джамуха потребовал выдать убийц своего брата, но Темучин, признававший верховенство закона, отказал в этом. Старые друзья стали врагами, а в монгольских степях началась долгая и кровопролитная борьба за власть над всеми племенами. Джамуха собрал три тумена (30 000 воинов) и разбил врага в битве у гор Гулегу.

Потерпев поражение, Темучин стал искать нового союзника и обрел его в 1196 году. Он стал вассалом Тоорил-хана, именуемого теперь на китайский лад Ван-ханом. В 1199 году хан призвал Темучина на войну против слабеющих найманов. В процессе битвы тумены Ван-хана оказались отрезаны и почти полностью уничтожены, самого хана ждала верная гибель, но Темучин как нельзя кстати прислал необходимую помощь, за что Ван-хан завещал ему свой улус после смерти.

Совместно с Ван-ханом Темучин в 1200 году выступил против тайджиутов и меркитов. Он был ранен в бою стрелой, но остался жив. Ночью после битвы большинство тайджиутов скрылось, а среди оставшихся обнаружился тот самый меткий лучник, что ранил Темучина. Стрелок нисколько не боялся в этом признаться, и восхищенный его мужеством Темучин принял лучника в свое войско под новым именем – Джэбэ (стрела). Впоследствии Джэбэ стал одним из самых прославленных командиров в армии Чингисхана.

В 1201 году против набирающего силу Темучина сложилась мощная коалиция племен ойратов, татар, тайджиутов и меркитов, которые объявили себя вассалами Джамухи. В 1202 году Темучин выступил против татар и разбил их. Под предлогом мести за смерть своего отца он приказал истребить их всех, кроме детей ростом ниже тележного колеса (по монгольским обычаям малых детей было запрещено убивать).

Вскоре Ван-хан, давний покровитель и союзник Темучина, под давлением своего сына, лишившегося права наследовать титул, перешел на сторону Джамухи. Весной 1203 года Темучин и Ван-хан сошлись в битве при Харахалджит-Элетах.

Итогом битвы фактически была ничья, но Темучин, изначально имевший гораздо меньшее по численности войско, понес в ней серьезные потери, лишившие его перспектив для дальнейших крупных сражений. Монголы были вынуждены отступать, теряя людей из-за голода, болезней и дезертирства.

Но в это же время сложилась коалиция против Ван-хана, в которую вошел и сам Джамуха. Ван-хан нанес упреждающий удар и разбил врагов, после чего начал пировать в честь победы. Узнав, что враг потерял бдительность, Темучин с оставшимися силами нанес Ван-хану неожиданный и стремительный удар, полностью разгромив неприятеля. Сам Ван-хан бежал, но вскоре попал в руки найманов и был убит. Так закончилась жизнь могущественного Ван-хана и подвластного ему кереитского царства.

Джамуха, лишившись союзников, примкнул со своим войском к найманам. В 1204 году Темучин собрал армию из 45 000 всадников, двинулся на найманов и одолел их. Кучлук, сын найманского хана, сумел бежать к меркитам и заручиться их поддержкой, однако Темучин разбил и меркитов в 1205 году. Кучлук вновь смог сбежать, на этот раз далеко на запад – в государство Каракиданей, где заключил удачный брак с дочерью местного гурхана, а позже и сам стал правителем.

С этого момента Джамуха был обречен – уже были покорены или истреблены все потенциальные союзники. Свои же соратники пленили Джамуху и отвезли к Темучину, надеясь на достойную награду. Но Темучин ненавидел предательство, и, согласно его законам, оно каралось смертью – именно такую награду и получили изменники.

Самому Джамухе была предложена жизнь и восстановление старой дружбы, но тот отказался и выбрал казнь через перелом хребта (у монголов – способ благородной казни для знатных особ).

А у Темучина тем временем больше не осталось в Великой степи врагов, которых он еще не победил. Весной 1206 года на курултае (всенародный съезд знати для принятия важнейших решений) Темучин принял новое имя Чингиз («Повелитель бескрайнего») и титул Великого Хана. С того момента мы знаем его под именем Чингисхан.

Монгольские завоевания Чингисхана

Чтобы навсегда положить конец междоусобицам среди монголов, нужно было постоянно иметь внешних врагов и всегда воевать с ними. Но численность населения Монголии была значительно ниже, чем у ближайших соседей, что предопределило ее дальнейшую внутреннюю политику.

Монголия стала предельно милитаризированной страной, где каждый взрослый и здоровый мужчина являлся воином, каждый старший сын был в военном резерве, а целью государства стали бесконечные завоевания и расширение границ. На тот момент в новом монгольском войске насчитывалось до десяти туменов (100 000 конных воинов), а для нужд армии в степи впервые появилась настоящая почтовая служба.

Но даже с такой численностью войск монголы в своих будущих войнах противостояли гораздо большим армиям, почти всегда побеждая благодаря талантам своих генералов. Боорчу, Джэбэ, Субэдэй, Хубилай и многие другие остались в истории как блестящие расчетливые стратеги, непредсказуемые и креативные командиры.

Характерной чертой армии Чингисхана была тщательная разведка всеми способами, в том числе разведка боем; распространено было дезинформирование противников, устройство засад, имитация панического отступления с последующей решительной контратакой.

Первым общемонгольским врагом небеспричинно стал северный Китай. В ту эпоху исторический Китай был разделен на три государства: относительно небольшое северо-западное царство Си Ся (оно же Тангутское царство) и две крупные империи – северная Цзинь (в которой правили иноземцы-чжурчжени, родственные современным эвенкам) и южная Сун. Цзинь и Сун были друг для друга историческими соперниками, а Си Ся – союзником Цзинь.

На протяжении тысячелетий между Китаем и народами Великой степи случались масштабные военные конфликты, а к началу XIII века они приобрели характер настоящего геноцида. Цзиньские армии осуществляли регулярные вторжения в степь с целью вырезать всех взрослых мужчин попавшихся им племен.

Узнав о планах Чингисхана воевать с ненавистной Цзинь, к нему добровольно присоединилось многочисленное племя уйгуров. Помимо того, старший сын Чингисхана Джучи провел в 1207 году успешную экспедицию на северо-запад (в современную Сибирь) и обложил данью местные коренные народы. До начала масштабной войны с Цзинь монголам еще нужно было лишить врагов поддержки союзников – Тангутского царства (Си Ся).

Чингисхан начал масштабную кампанию против тангутов в 1209 году. Разбив врагов в полевом сражении, монголы подошли к стенам столичного города Чжунсина (ныне город Иньчуань в Китае).

Город имел мощные укрепления и охранялся многочисленным гарнизоном, так что взять его штурмом было невозможно, а длительная осада была не в интересах монголов, опасавшихся, что к врагам придет подкрепление от Цзинь (впрочем, на самом деле чжурчжени в грубой и оскорбительной форме отвергли тангутских послов). Было решено затопить город водами местной реки, но сыграло свою роль отсутствие у монголов опыта строительства таких сложных сооружений, как плотины.

В итоге вода из реки хлынула не в город, а на лагерь монголов, вынудив последних снимать осаду и искать с тангутами компромисс. И он был найден, причем с выгодными для Чингисхана условиями. Тангутский царь, разгневанный из-за предательства на своих цзиньских союзников, присягнул на верность Чингисхану и стал его вассалом. В итоге империя Цзинь обрела нового врага.

В это же время Цзинь вела тяжелую войну на юге с могущественной империей Сун. Почти все армии были на южных границах, а монгольская угроза с севера была явно недооценена. К монгольской армии присоединились тангутские инженеры, которые знали все о штурме городов и умели строить осадные машины. Теперь Чингисхан мог не просто совершать грабительские набеги, а вести полноценную войну с оккупацией городов и территорий.

И такая война началась весной 1211 года, когда Чингисхан во главе своей стотысячной армии, заняв приграничный китайский город Фучжоу, столкнулся с четырехсоттысячной армией врага. Произошло сражение у хребта Ехулин, в котором огромное войско китайцев было полностью уничтожено. В августе того же года монголы овладели стратегически важной крепостью Байдэнчэн, которая являлась своеобразными «воротами» в Великой китайской стене.

Пройдя внутрь стены, монголы оказались теперь уже в самом сердце империи Цзинь. Больше никакой недооценки не могло быть, и чжурчжени стали перебрасывать свои армии с юга на север для борьбы с монголами. Монгольский генерал Джэбэ, обнаружив еще одну (и последнюю) гигантскую армию чжурчжэней, заманил ее в удобную для конницы Сюаньдэфускую долину с помощью своего любимого приема – ложного отступления. Здесь и была окончательно уничтожена основная армия империи Цзинь.

И тогда очень многое в империи поменялось. Местные кидани и китайцы уже больше не боялись чжурчженей, а Чингисхана считали своим освободителем. В 1213–1214 годах монгольские армии беспрепятственно оккупировали весь северный Китай.

Тогда же при дворе Чингисхана появляется потомок династии Ляо (ранее правившей этим государством) по имени Елюй Чуцай – ключевая фигура в дальнейшем становлении монгольской государственности, автор важнейших административных реформ, уже после смерти Чингисхана превративший Монголию из кочевой орды в развитую империю.

После триумфа в Китае монголы недолго выбирали себе нового противника. Старый враг Чингисхана – Кучлук, сын найманского хана, воевал против монголов в 1205 году, а после поражения бежал на запад к Каракиданям в регион Семиречья. К моменту окончания монгольско-китайского конфликта Кучлук был уже правителем на своей новой родине. Чингисхана давно привлекали богатства Семиречья с его древней и развитой торговой системой.

Кроме того, Кучлук, предположительно будучи несторианином, осуществлял в своих землях геноцид мусульман, за что получил репутацию кровавого тирана (монголы же были известны своей абсолютной терпимостью ко всем религиям).

Также Кучлук имел враждебные отношения со своим южным соседом – исламским Хорезмом. В 1218 году в Семиречье вторглась армия монголов под предводительством Джэбэ, начался масштабный и продолжительный западный поход.

Каракиданям был предложен достойный выбор: присоединиться к монголам в их дальнейших походах и взять богатую добычу, либо бессмысленно погибнуть в боях за ненавистного им Кучлука. В итоге Кучлук был почти беспрепятственно свергнут и бежал в Памир, где вскоре был убит, а Семиречье вошло в состав монгольской империи.

Новым соседом монголов теперь стал Хорезм. Это была богатейшая держава, контролирующая бывшие столицы великих древних империй – Элама, Персидской державы Ахеменидов, Парфии, Сасанидского царства.

Столица Хорезма – город Ургенч с населением 600 000 человек был крупнейшим городом мира, а регулярная армия насчитывала 400 000 хорошо обученных и вооруженных воинов. У монголов против такой мощной державы был шанс разве что совершить грабительский набег в приграничных территориях, а о захвате всей страны не стоило даже мечтать.

Можно сказать, что эта великая страна погибла от рук своего же правителя. Чингисхан изначально не собирался воевать с хорезмшахом и даже был инициатором торгового союза с соседями. Однако в 1219 году случилось непоправимое – в хорезмском городе Отрар были казнены монгольские послы и купцы.

Гибель своих послов Чингисхан не прощал никогда и никому. Он потребовал от хорезмшаха выдать виновных, но тот выбрал единственный неправильный вариант переговоров – обезглавил одного из очередных послов Великого Хана, а остальных отпустил, обрезав им бороды.

Началась война 1219–1221 годов. Хорезмшах принял губительное для страны решение – не собирать единое большое войско, а рассредоточить армии по городам и держать оборону. Для монголов это был шикарный подарок судьбы – теперь в каждой битве численное преимущество было на их стороне. А со штурмом городов никаких проблем не было, ведь к этому времени уже в каждом тумене был отряд китайских инженеров, создававших камнеметные орудия.

Всего два года ушло у монголов, чтобы по очереди взять штурмом все города. К сожалению, местные правители боялись хорезмшаха гораздо сильнее, чем Чингисхана, поэтому отказывались сдаваться и обрекали свои города на полное разрушение. После окончания войны Хорезм вместе с богатейшим историко-культурным наследием предыдущих империй лежал в руинах.

Хорезмшах Мухаммед II, видя крах своей державы, в 1220 году бежал сначала в оставшиеся города Ирана, затем в Закавказье. Чингисхан отправил три тумена во главе с опытнейшими Джэбэ, Субэдэем и Тохучаром в погоню за врагом. Позже Тохучар вместе со своим туменом был отозван и наказан за нарушение им договоренностей Чингисхана с некоторыми местными правителями (по другим источникам – погиб в сражениях с племенами горцев).

Погоню продолжили два тумена. Мухаммед обосновался на острове в Каспийском море, где тяжело заболел и умер предположительно в декабре 1220 года.

Узнав о смерти Мухаммеда, Джэбэ и Субэдэй отправили соответствующее извещение Чингисхану и, находясь уже за несколько тысяч километров от его ставки, самовольно решили продолжить поход на Кавказ и далее в кыпчакскую степь (в половецкие земли). Имея в распоряжении всего 20 000 воинов, они разбили аланов и двинулись на половцев. Так случился первый контакт монголов с Русью.

Половцы призвали русских князей на помощь в борьбе против новых иноземных захватчиков. В ту пору русские дружины славились на всю Европу как одна из самых могучих военных сил в известном мире, и князей безусловно заинтересовала возможность продемонстрировать всем свою военную мощь. Это было фатальное решение, которое позже предопределило враждебность отношений между Русью и Монгольской империей.

Против 20 000 монгольских всадников была собрана русско-половецкая армия численностью 80 000 воинов, которую возглавил галицкий князь Мстислав Удатный – доблестный воин, но бесхитростный полководец. Битва состоялась в 1223 году на реке Калке, куда русичей и половцев заманил Джэбэ.

Видя якобы беспорядочное отступление тумена Джэбэ, Мстислав Удатный бросился в погоню, пересек Калку и угодил в засаду Субэдэя. Состоялась кровопролитная битва, в которую половцы даже не стали вмешиваться, а Мстислав был вынужден отступать обратно через реку. Добравшись до лодок, он со своей дружиной стал переправляться через Калку, а оставшиеся лодки приказал сжечь, чтобы монголы не смогли пуститься в погоню – тем самым он обрек оставшихся на поле боя русичей на верную гибель.

Монголы понесли огромные потери в битве на Калке. Двинувшись на восток, чтобы вернуться в ставку Чингисхана, их обессиленные тумены потерпели сокрушительное поражение от волжских булгар. В 1224 году в Монголию вместе с Джэбэ и Субэдэем вернулись живыми лишь 4000 человек.

В феврале 1225 года Чингисхан вернулся в родную степь, чтобы решить одну старую проблему. Еще перед началом западного похода тангутское царство отказалось от своих вассальных обязательств и не предоставило ему свою армию. Тогда у Великого Хана были гораздо более амбициозные цели, чем усмирять непокорных, и он решил разобраться с тангутами позже.

И вот час возмездия настал: в 1226–1227 годах монголы захватывали один за другим тангутские города и истребляли местное население. Столичный город Чжунсин держался около года, но в итоге тоже пал. Тангутское царство было навсегда разрушено, а его народ полностью уничтожен.

Во время кампании против тангутов уже немолодой Чингисхан неудачно упал с лошади и тяжело заболел от полученных травм в сочетании с местным суровым климатом. Великий Хан умер в августе или сентябре 1227 года, оставив свою империю чингизидам – своим сыновьям от брака с Бортэ, которые еще долгое время продолжали великие завоевания и расширяли границы империи.

Роль Чингисхана в истории

Своими личными качествами Чингисхан запомнился современникам как безусловно великий человек. Его отличали бесконечная преданность друзьям и семье, ответственность перед подданными, умение слушать правду, какой бы она ни была, и абсолютная неприязнь к воровству и предательству. Однако своими завоеваниями он и его империя запустили в дальнейшей мировой истории такую цепь событий, какую невозможно однозначно охарактеризовать положительно или отрицательно.

Для монгольских племен изменения были самыми масштабными. При Чингисхане была принята Яса – первый всеобъемлющий список законов. Монголы – маленький кочевой народ, каких в степи были десятки – впервые обрели настоящую государственность, а позднее, благодаря реформам вышеупомянутого Елюя Чуцая, стали богатой и процветающей нацией, сохранившей свою этническую самобытность до наших дней.

Для Китая взаимоотношения с монголами стали отдельной и очень важной главой в истории. Чингисхан освободил китайскую нацию от чжурчжэней, а его внук Хубилай впервые за много веков объединил страну, создав империю Юань и сделав Пекин столицей Монгольской Империи.

Для Ирана и Средней Азии последствия монгольского нашествия были катастрофическими. Богатейший регион пришел в упадок и стал восстанавливать свое могущество лишь спустя 150 лет во времена правления великого завоевателя Тамерлана.

Подход Чингисхана к переговорам с осажденными городами был прост: можно либо добровольно сдаться и сохранить свои жизни, культуру и имущество (как происходило в Китае), либо оказать сопротивление – и тогда город вместе с жителями будет полностью уничтожен. К сожалению, большинство древних хорезмских городов выбрали второй вариант.

На Руси военное столкновение с туменами Чингисхана навсегда изменило ход истории. Участие русских князей в битве на Калке породило желание монголов отомстить и совершить разрушительный поход на Русь 1237–1241 годов, в результате которого развитая по тем временам русская экономика пришла в упадок. Все княжества утратили суверенитет вплоть до 1480 года.

Только Новгородская Республика сохранила независимость благодаря дружеским отношениям между монголами и Александром Невским. В целях борьбы с монгольским игом западные княжества добровольно присоединялись к Литве и Польше, а в северо-восточных территориях запустился процесс собирания земель русских, результатом которого стало закрепощение крестьян, угасание демократии в Новгороде и Пскове и возвышение принципов самодержавия.

This article is about Genghis Khan, the historical figure and Mongol leader. For other uses, see Genghis Khan (disambiguation).

| Genghis Khan | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||

Genghis Khan as portrayed in a 14th-century Yuan era album; now located in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. The original version was in black and white; produced by the Mongol painter Ho-li-hosun in 1278 under the commission of Kublai Khan. |

||||||||

| Great Khan of the Mongol Empire | ||||||||

| Reign | Spring 1206 – August 25, 1227 | |||||||

| Coronation | Spring 1206 in a Kurultai at the Onon River, in modern-day Mongolia | |||||||

| Successor | Tolui (as regent) Ögedei Khan |

|||||||

| Born | Temüjin[note 1] c. 1162[2] Khentii Mountains, Khamag Mongol |

|||||||

| Died | August 25, 1227 (aged 64–65) Xingqing, Western Xia |

|||||||

| Burial |

Unknown |

|||||||

| Spouse |

|

|||||||

| Issue |

|

|||||||

|

||||||||

| House | Borjigin | |||||||

| Dynasty | Genghisid | |||||||

| Father | Yesügei | |||||||

| Mother | Hoelun | |||||||

| Religion | Tengrism |

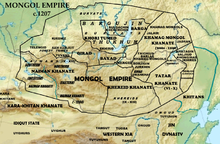

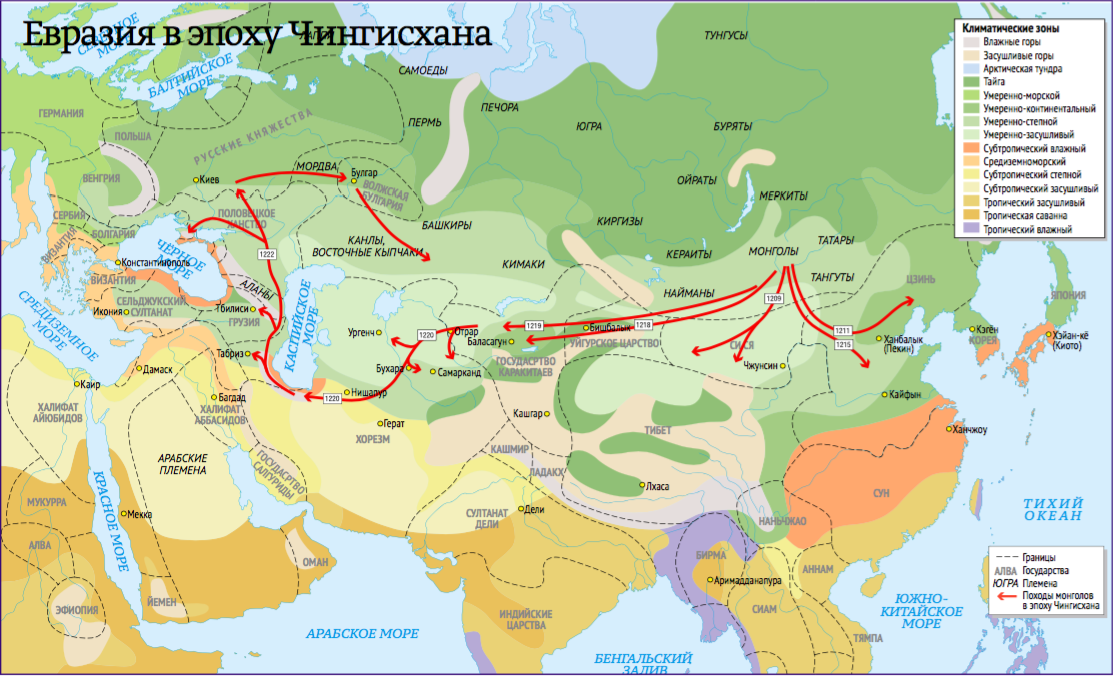

Genghis Khan[note 4] (born Temüjin;[note 1] c. 1162 – August 25, 1227)[2] was the founder and first Great Khan (Emperor) of the Mongol Empire, which became the largest contiguous empire in history after his death. He came to power by uniting many of the nomadic tribes of the Mongol steppe and being proclaimed the universal ruler of the Mongols, or Genghis Khan. With the tribes of Northeast Asia largely under his control, he set in motion the Mongol invasions, which ultimately witnessed the conquest of much of Eurasia, and incursions by Mongol raiding parties as far west as Legnica in western Poland and as far south as Gaza. He launched campaigns against the Qara Khitai, Khwarezmia, the Western Xia and Jin dynasty during his life, and his generals raided into medieval Georgia, Circassia, the Kievan Rus’, and Volga Bulgaria.

His exceptional military successes made Genghis Khan one of the most important conquerors of all time, and by the end of the Great Khan’s life, the Mongol Empire occupied a substantial portion of Central Asia and present-day China.[11] Genghis Khan and his story of conquest have a fearsome reputation in local histories.[12] Medieval chroniclers and modern historians describe Genghis Khan’s conquests as resulting in such destruction that they led to drastic population declines in some regions. Estimates of the number of people who died through war, disease and famine as a consequence of Genghis Khan’s military campaigns range from about four million in the most conservative estimates to up to sixty million in the most sweeping historical accounts.[13][14][15] On the other hand, Genghis Khan has also been portrayed positively by authors ranging from medieval and renaissance scientists in Europe to modern historians for the spread of technological and artistic ideas under Mongol influence.[16]

Beyond his military successes, Genghis Khan’s civil achievements included the establishment of Mongol law and the adoption of the Uyghur script as a writing system across his vast territories. He also practiced meritocracy and religious tolerance. Present-day Mongolians regard him as the founding father of Mongolia for unifying the nomadic tribes of Northeast Asia.[17] By bringing the Silk Road under one cohesive political environment, he also considerably eased communication and trade between Northeast Asia, Muslim Southwest Asia, and Christian Europe, boosting global commerce and expanding the cultural horizons of all the Eurasian civilizations of the day.[18]

Names and titles

According to The Secret History of the Mongols, Genghis Khan’s birth name Temüjin (Chinese: 鐵木眞; pinyin: Tiěmùzhēn) came from the Tatar chief Temüjin-üge whom his father had just captured. The name Temüjin is also equated with the Turco-Mongol temürči(n), «blacksmith», and there existed a tradition that viewed Genghis Khan as a smith, according to Paul Pelliot, which, though unfounded, was well established by the middle of the 13th century.[19]

Genghis Khan is an honorary title meaning «universal ruler» that represents an aggrandization of the pre-existing title of Khan that is used to denote a clan chief in Mongolian. The appellation of «Genghis» to the term is thought to derive from the Turkic word «tengiz«, meaning sea, making the honorary title literally «oceanic ruler», but understood more broadly as a metaphor for the universality or totality of Temüjin’s rule from a Mongol perspective.[20][21]

When Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty in 1271, he had his grandfather Genghis Khan placed in official records and accorded him the temple name Taizu (Chinese: 太祖)[6][7] and the posthumous name Emperor Shengwu (Chinese: 聖武皇帝). Genghis Khan is thus also referred to as Yuan Taizu (Emperor Taizu of Yuan; Chinese: 元太祖) in Chinese historiography. Külüg Khan later expanded Genghis Khan’s title to Emperor Fatian Qiyun Shengwu (Chinese: 法天啟運聖武皇帝).[5]

Early life

Lineage and birth

Autumn at the Onon River, Mongolia, the region where Temüjin was born and grew up

Temüjin was born the first son of Hoelun, second wife of his father Yesügei, who was the chief of the Borjigin clan in the nomadic Khamag Mongol confederation,[21] nephew to Ambaghai and Hotula Khan,[22][23] and an ally of Toghrul of the Keraite tribe.[24] Temüjin was related on his father’s side to Khabul Khan, Ambaghai, and Hotula Khan, who had headed the Khamag Mongol confederation and were descendants of Bodonchar Munkhag (c. 900),[25][26] while his mother Hoelun was from the Olkhunut sub-lineage of the Khongirad tribe.[27][28] Temüjin’s noble background made it easier for him, later in life, to solicit help from and eventually consolidate the other Mongol tribes.[29]

There is considerable uncertainty surrounding both the date and location of Temüjin’s birth, with historical accounts assigning dates of birth ranging from 1155 to 1182 and a wide variety of possible birth locations. The Arab historian Rashid al-Din asserted that Temüjin was born in 1155, while the History of Yuan records his year of birth as 1162 and Tibetan sources implausibly present 1182 as the correct date.[2] Modern historical studies have largely attested the 1162 date presented by the Chinese history as the most realistic, given the significant problems associated with how either the 1155 or 1182 dates would reflect on other events in Temüjin’s timeline.[25] Accepting a birth in 1155, for instance, would render Temüjin a father at the age of 30 and would imply that he personally commanded the expedition against the Tanguts at the age of 72.[25] The Secret History of the Mongols relates that Temüjin was an infant during the attack by the Merkits, when a birth date of 1155 would have made him 18 years old.[25] The 1162 date has meanwhile been attested by various sources, including a 1992 study of the Mongol calendar commissioned by UNESCO that suggested the specific date of 1 May 1162.[2]

The location of Temüjin’s birth is largely shrouded in mystery, with a wide range of locations proposed, many in the vicinity of the mountain Burkhan Khaldun. One such location is Delüün Boldog, which lies near the rivers Onon and Kherlen.[25]

Tribal upbringing

Temüjin grew up with three brothers, Qasar, Hachiun, and Temüge; one sister, Temülen; and two half-brothers, Behter and Belgutei. As was common to nomads in Mongolia, Temüjin’s early life was marked by difficulties.[30]

At age nine, his father arranged a marriage for him and delivered him to the family of his future wife Börte of the tribe Khongirad. Temüjin was to live there serving the head of the household Dai Setsen until the marriageable age of 12.[31][32] While heading home, his father ran into the neighboring Tatars, who had long been Mongol enemies, and they offered his father food under the guise of hospitality, but instead poisoned him. Upon learning this, Temüjin returned home to claim his father’s position as chief, but the tribe refused him and abandoned the family, leaving it without protection.[33]

For the next several years, the family lived in poverty, surviving mostly on wild fruits, ox carcasses, marmots, and other small game killed by Temüjin and his brothers.[34] During this time, Temüjin’s mother, Hoelun, taught him about Mongol politics, including the lack of unity between the different clans and the need for arranged marriages to solidify temporary alliances, and strong alliances to ultimately ensure the stability of Mongolia.[35] Indeed, he was later successful, in part, because of his mother’s role as a warrior in battle.[36]

Over time, Temüjin’s older half-brother Behter began to exercise power as the eldest male in the family,[34] creating tension in the family that boiled over during one hunting excursion by the men of the family and resulted in the death of Behter at the hands of Temüjin and his brother Qasar.[34]

Later, in a raid around 1177, Temüjin was captured by his father’s former allies, the Tayichi’ud, enslaved, and, reportedly humiliated by being shacked in a cangue (a form of portable stocks). With the help of a sympathetic guard, he escaped from the ger (yurt) at night by hiding in a river crevice.[37] The escape earned Temüjin a reputation. Soon, Jelme and Bo’orchu joined forces with him, and they and the guard’s son Chilaun eventually became generals of Genghis Khan.[38]

Wives and concubines

As was common for powerful Mongol men, Temüjin had many wives and concubines.[39] These women were often queens or princesses that were taken captive from the territories he conquered or gifted to him by allies, vassals, or other tribal acquaintances.[40] His principal or most famous wives and concubines included: Börte, Yesugen, Yesui, Khulan Khatun, Möge Khatun, Juerbiesu, and Ibaqa Beki.

He gave several of his high-status wives their own ordos or camps to live in and manage. Each camp also contained junior wives, concubines, and children. It was the job of the Kheshig (Mongol imperial guard) to protect the yurts of Temüjin’s wives. The guards had to pay particular attention to the individual yurt and camp in which Temüjin slept, which could change every night as he visited different wives.[41] When he set out on his military conquests, he usually took one wife with him and left the rest of his wives and concubines to manage the empire in his absence.[42]

Uniting the Mongol confederations, 1184–1206

The locations of the Mongolian tribes during the Khitan Liao dynasty (907–1125)

In the early 12th century, the Central Asian plateau north of China was divided into several prominent tribal confederations, including Naimans, Merkits, Tatars, Khamag Mongols, and Keraites, that were often unfriendly towards each other, as evidenced by random raids, revenge attacks, and plundering.

Early attempts at power

Temüjin began his ascent to power by offering himself as an ally (or, according to other sources, a vassal) to his father’s anda (sworn brother or blood brother) Toghrul, who was Khan of the Keraites. This relationship was first reinforced when Börte was kidnapped by Merkits in around 1184. To win her back, Temüjin called on the support of Toghrul, who offered 20,000 of his Keraite warriors and suggested that Temüjin involve his childhood friend Jamukha, who was Khan of his own tribe, the Jadaran.[43]

Rift with Jamukha and defeat

As Jamukha and Temüjin drifted apart in their friendship, each began consolidating power and they became rivals. Jamukha supported the traditional Mongolian aristocracy, while Temüjin followed a meritocratic method, and attracted a broader range and lower class of followers.[44] Following his earlier defeat of the Merkits, and a proclamation by the shaman Kokochu that the Eternal Blue Sky had set aside the world for Temüjin, Temüjin began rising to power.[45] In 1186, Temüjin was elected khan of the Mongols. Threatened by this rise, Jamukha attacked Temujin in 1187 with an army of 30,000 troops. Temüjin gathered his followers to defend against the attack, but was decisively beaten in the Battle of Dalan Balzhut.[45][46] However, Jamukha horrified and alienated potential followers by boiling 70 young male captives alive in cauldrons.[47] Toghrul, as Temüjin’s patron, was exiled to the Qara Khitai.[48] The life of Temüjin for the next 10 years is unclear, as historical records are mostly silent on that period.[48]

Return to power

Around the year 1197, the Jin initiated an attack against their formal vassal, the Tatars, with help from the Keraites and Mongols. Temüjin commanded part of this attack, and after victory, he and Toghrul were restored by the Jin to positions of power.[48] The Jin bestowed Toghrul with the honorable title of Ong Khan, and Temüjin with a lesser title of j’aut quri.[49]

Around 1200, the main rivals of the Mongol confederation (traditionally the «Mongols») were the Naimans to the west, the Merkits to the north, the Tanguts to the south, and the Jin to the east.

Jurchen inscription (1196) in Mongolia relating to Temüjin’s alliance with the Jin against the Tatars

In his rule and his conquest of rival tribes, Temüjin broke with Mongol tradition in a few crucial ways. He delegated authority based on merit and loyalty, rather than family ties.[50] As an incentive for absolute obedience and the Yassa code of law, Temüjin promised civilians and soldiers wealth from future war spoils. When he defeated rival tribes, he did not drive away their soldiers and abandon their civilians. Instead, he took the conquered tribe under his protection and integrated its members into his own tribe. He would even have his mother adopt orphans from the conquered tribe, bringing them into his family. These political innovations inspired great loyalty among the conquered people, making Temüjin stronger with each victory.[50]

Rift with Toghrul

Senggum, son of Toghrul (Wang Khan), envied Temüjin’s growing power and affinity with his father. He allegedly planned to assassinate Temüjin. Although Toghrul was allegedly saved on multiple occasions by Temüjin, he gave in to his son[51] and became uncooperative with Temüjin. Temüjin learned of Senggum’s intentions and eventually defeated him and his loyalists.

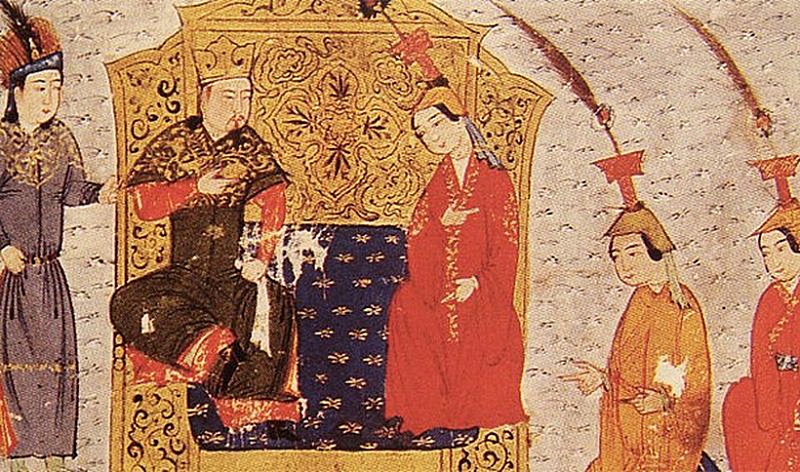

Genghis Khan and Toghrul Khan, illustration from a 15th-century Jami’ al-tawarikh manuscript

One of the later ruptures between Temüjin and Toghrul was Toghrul’s refusal to give his daughter in marriage to Jochi, Temüjin’s first son. This was disrespectful in Mongolian culture and led to a war. Toghrul allied with Jamukha, who already opposed Temüjin’s forces. However, the dispute between Toghrul and Jamukha, plus the desertion of a number of their allies to Temüjin, led to Toghrul’s defeat. Jamukha escaped during the conflict. This defeat was a catalyst for the fall and eventual dissolution of the Keraite tribe.[52]

After conquering his way steadily through the Alchi Tatars, Keraites, and Uhaz Merkits and acquiring at least one wife each time, Temüjin turned to the next threat on the steppe, the Turkic Naimans under the leadership of Tayang Khan with whom Jamukha and his followers took refuge.[53] The Naimans did not surrender, although enough sectors again voluntarily sided with Temüjin.

In 1201, a Khuruldai elected Jamukha as Gür Khan, «universal ruler», a title used by the rulers of the Qara Khitai. Jamukha’s assumption of this title was the final breach with Temüjin, and Jamukha formed a coalition of tribes to oppose him. Before the conflict, several generals abandoned Jamukha, including Subutai, Jelme’s well-known younger brother. After several battles, Jamukha was captured in 1205.[54]

According to The Secret History of the Mongols, Temüjin again offered his friendship to Jamukha. Temüjin had killed the men who betrayed Jamukha, stating that he did not want disloyal men in his army. Jamukha refused the offer, saying that there can only be one sun in the sky, and he asked for a noble death. The custom was to die without spilling blood, specifically by having one’s back broken. According to one account, Jamukha was executed by suffocation.[55]

Sole ruler of the Mongol plains

Genghis Khan proclaimed Khagan of all Mongols. Illustration from a 15th-century Jami’ al-tawarikh manuscript.

The part of the Merkit clan that sided with the Naimans were defeated by Subutai, who was by then a member of Temüjin’s personal guard and later became one of Temüjin’s most successful commanders. The Naimans’ defeat left Temüjin as the sole ruler of the Mongol steppe – all the prominent confederations fell or united under his Mongol confederation.

Accounts of Temüjin’s life are marked by claims of a series of betrayals and conspiracies. These include rifts with his early allies such as Jamukha (who also wanted to be a ruler of Mongol tribes) and Wang Khan (his and his father’s ally), his son Jochi, and problems with the most important shaman, who allegedly tried to drive a wedge between him and his loyal brother Khasar. His military strategies showed a deep interest in gathering intelligence and understanding the motivations of his rivals, exemplified by his extensive spy network and Yam route systems. He seemed to be a quick student, adopting new technologies and ideas that he encountered, such as siege warfare from the Chinese. He was also ruthless, demonstrated by his tactic of measuring against the linchpin, used against the tribes led by Jamukha.

As a result, by 1206, Temüjin had managed to unite or subdue the Merkits, Naimans, Mongols, Keraites, Tatars, Uyghurs, and other disparate smaller tribes under his rule. This was a monumental feat. It resulted in peace between previously warring tribes, and a single political and military force. The union became known as the Mongols. At a Khuruldai, a council of Mongol chiefs, Temüjin was acknowledged as Khan of the consolidated tribes and took the new title «Genghis Khan». The title Khagan was conferred posthumously by his son and successor Ögedei who took the title for himself (as he was also to be posthumously declared the founder of the Yuan dynasty).

According to The Secret History of the Mongols, the chieftains of the conquered tribes pledged to Genghis Khan by proclaiming:

«We will make you Khan; you shall ride at our head, against our foes. We will throw ourselves like lightning on your enemies. We will bring you their finest women and girls, their rich tents like palaces.»[56][57]

Military campaigns, 1207–1227

Western Xia dynasty

During the 1206 political rise of Genghis Khan, the Mongol Empire and its allies shared their western borders with the Tangut Western Xia dynasty. To the east and south of the Western Xia dynasty was the militarily superior Jin dynasty, founded by the Manchurian Jurchens, who ruled northern China as well as being the traditional overlords of the Mongolian tribes for centuries.[58]

Though militarily inferior to the neighboring Jin, the Western Xia still exerted a significant influence upon the adjacent northern steppes.[58] Following the death of the Keraites leader Ong Khan to Temüjin’s emerging Mongol Empire in 1203, Keriat leader Nilqa Senggum led a small band of followers into Western Xia before later being expelled from Western Xia territory.[58]

Battle between Mongol warriors and the Chinese

Using his rival Nilga Senggum’s temporary refuge in Western Xia as a pretext, Temüjin launched a raid against the state in 1205 in the Edsin region.[58] The next year, in 1206, Temüjin was formally proclaimed Genghis Khan, ruler of all the Mongols, marking the official start of the Mongol Empire, and the same year Emperor Huanzong of the Western Xia was deposed by Li Anquan in a coup d’état. In 1207, Genghis led another raid into Western Xia, invading the Ordos region and sacking Wuhai, the main garrison along the Yellow River, before withdrawing in 1208. Genghis then began preparing for a full-scale invasion, organizing his people, army and state to first prepare for war.[59]

By invading Western Xia, Genghis Khan would gain a tribute-paying vassal, and also would take control of caravan routes along the Silk Road and provide the Mongols with valuable revenue.[60] Furthermore, from Western Xia he could launch raids into the even more wealthy Jin dynasty.[61] He correctly believed that the more powerful young ruler of the Jin dynasty would not come to the aid of the Western Xia. When the Tanguts requested help from the Jin dynasty, they were refused.[51] Despite initial difficulties in capturing Western Xia cities, Genghis Khan managed to force Emperor Renzong to submit to vassal status.

Jin dynasty

In 1211, after the conquest of Western Xia, Genghis Khan planned again to conquer the Jin dynasty. Luckily for the Mongols, Wanyan Jiujin, the field commander of the Jin army, made several tactical mistakes, including avoiding attacking the Mongols at the first opportunity using his overwhelming numerical superiority, and instead initially fortifying behind the Great wall. At the subsequent Battle of Yehuling, which the Jin commander later committed to in the hope of using the mountainous terrain to his advantage against the Mongols, the general’s emissary Ming’an defected to the Mongol side and instead handed over intelligence on the movements of the Jin army, which was subsequently outmanoeuvred, resulting in hundreds of thousands of Jin casualties. So many, in fact, that decades later, when the Daoist sage Qiu Chuji was passing through this pass to meet Genghis Khan, he was stunned to still see the bones of so many people scattered in the pass. On his way back, he camped close to this pass for three days and prayed for the departed souls. In 1215, Genghis besieged the Jin capital of Zhongdu (modern-day Beijing). According to Ivar Lissner, the inhabitants resorted to firing gold and silver cannon shot on the Mongols with their muzzle-loading cannons when their supply of metal for ammunition ran out.[62][63][64] The city was captured and sacked. This forced the Jin ruler, Emperor Xuanzong, to move his capital south to Kaifeng, abandoning the northern half of his empire to the Mongols. Between 1232 and 1233, Kaifeng fell to the Mongols under the reign of Genghis’s third son and successor, Ögedei Khan. The Jin dynasty collapsed in 1234, after the siege of Caizhou.

Qara Khitai

Kuchlug, the deposed Khan of the Naiman confederation that Genghis Khan defeated and folded into his Mongol Empire, fled west and usurped the khanate of Qara Khitai (also known as the Western Liao, as it was originally established as remnants of the Liao dynasty). Genghis Khan decided to conquer the Qara Khitai and defeat Kuchlug, possibly to take him out of power. By this time the Mongol army was exhausted from ten years of continuous campaigning in China against the Western Xia and Jin dynasty. Therefore, Genghis sent only two tumen (20,000 soldiers) against Kuchlug, under his younger general, Jebe, known as «The Arrow».

With such a small force, the invading Mongols were forced to change strategies and resort to inciting internal revolt among Kuchlug’s supporters, leaving the Qara Khitai more vulnerable to Mongol conquest. As a result, Kuchlug’s army was defeated west of Kashgar. Kuchlug fled again, but was soon hunted down by Jebe’s army and executed. By 1218, as a result of the defeat of Qara Khitai, the Mongol Empire and its control extended as far west as Lake Balkhash, which bordered Khwarazmia, a Muslim state that reached the Caspian Sea to the west and Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea to the south.[65]

Khwarazmian Empire

Khwarazmian Empire (green) c. 1200, on the eve of the Mongol invasions

In the early 13th century, the Khwarazmian dynasty was governed by Shah Ala ad-Din Muhammad. Genghis Khan saw the potential advantage in Khwarazmia as a commercial trading partner using the Silk Road, and he initially sent a 500-man caravan to establish official trade ties with the empire. Genghis Khan and his family and commanders invested in the caravan gold, silver, silk, various kinds of textiles and fabrics and pelts to trade with the Muslim traders in the Khwarazmian lands.[66] However, Inalchuq, the governor of the Khwarazmian city of Otrar, attacked the caravan, claiming that the caravan contained spies and therefore was a conspiracy against Khwarazmia. The situation became further complicated because the governor later refused to make repayments for the looting of the caravans and hand over the perpetrators. Genghis Khan then sent a second group of three ambassadors (two Mongols and a Muslim) to meet the Shah himself, instead of the governor Inalchuq. The Shah had all the men shaved and the Muslim beheaded and sent his head back with the two remaining ambassadors. Outraged, Genghis Khan planned one of his largest invasion campaigns by organizing together around 100,000 soldiers (10 tumens), his most capable generals and some of his sons. He left a commander and number of troops in China, designated his successors to be his family members and likely appointed Ögedei to be his immediate successor and then went out to Khwarazmia.

The Mongol army under Genghis Khan, generals and his sons crossed the Tien Shan mountains by entering the area controlled by the Khwarazmian Empire. After compiling intelligence from many sources Genghis Khan carefully prepared his army, which was divided into three groups. His son Jochi led the first division into the northeast of Khwarazmia. The second division under Jebe marched secretly to the southeast part of Khwarazmia to form, with the first division, a pincer attack on Samarkand. The third division under Genghis Khan and Tolui marched to the northwest and attacked Khwarazmia from that direction.

The Shah’s army was split by diverse internecine feuds and by the Shah’s decision to divide his army into small groups concentrated in various cities. This fragmentation was decisive in Khwarazmia’s defeats, as it allowed the Mongols, although exhausted from the long journey, to immediately set about defeating small fractions of the Khwarazmian forces instead of facing a unified defense. The Mongol army quickly seized the town of Otrar, relying on superior strategy and tactics. Genghis Khan ordered the wholesale massacre of many of the civilians, enslaved the rest of the population and executed Inalchuq by pouring molten silver into his ears and eyes, as retribution for his actions.

Next, Genghis Khan besieged the city of Bukhara. Bukhara was not heavily fortified, with just a moat and a single wall, and the citadel typical of Khwarazmian cities. The city leaders opened the gates to the Mongols, though a unit of Turkish defenders held the city’s citadel for another twelve days. The survivors from the citadel were executed, artisans and craftsmen were sent back to Mongolia, young men who had not fought were drafted into the Mongolian army and the rest of the population was sent into slavery.[67] After the surrender of Bukhara, Genghis Khan also took the unprecedented step of personally entering the city, after which he had the city’s aristocrats and elites brought to the mosque, where, through interpreters, he lectured them on their misdeeds, saying: «If you had not committed great sins, God would not have sent a punishment like me upon you.»[68]

Significant conquests and movements of Genghis Khan and his generals

With the capture of Bukhara, the way was clear for the Mongols to advance on the capital of Samarkand, which possessed significantly better fortifications and a larger garrison compared to Bukhara. To overcome the city, the Mongols engaged in intensive psychological warfare, including the use of captured Khwarazmian prisoners as body shields. After several days only a few remaining soldiers, loyal supporters of the Shah, held out in the citadel. After the fortress fell, Genghis executed every soldier that had taken arms against him. According to the Persian historian Ata-Malik Juvayni, the people of Samarkand were then ordered to evacuate and assemble in a plain outside the city, where they were killed and pyramids of severed heads raised as a symbol of victory.[69] Similarly, Juvayni wrote that in the city Termez, to the south of Samarkand, «all the people, both men and women, were driven out onto the plain, and divided in accordance with their usual custom, then they were all slain».[69]

Juvayni’s account of mass killings at these sites is not corroborated by modern archaeology. Instead of killing local populations, the Mongols tended to enslave the conquered and either send them to Mongolia to act as menial labor or retain them for use in the war effort. The effect was still mass depopulation.[68] The piling of a «pyramid of severed heads» happened not at Samarkand but at Nishapur, where Genghis Khan’s son-in-law Toquchar was killed by an arrow shot from the city walls after the residents revolted. The Khan then allowed his widowed daughter, who was pregnant at the time, to decide the fate of the city, and she decreed that the entire population be killed. She also supposedly ordered that every dog, cat and any other animals in the city by slaughtered, «so that no living thing would survive the murder of her husband».[68] The sentence was duly carried out by the Khan’s youngest son Tolui.[70] According to widely circulated but unverified stories, the severed heads were then erected in separate piles for the men, women and children.[68]

Near to the end of the battle for Samarkand, the Shah fled rather than surrender. Genghis Khan subsequently ordered two of his generals, Subutai and Jebe, to destroy the remnants of the Khwarazmian Empire, giving them 20,000 men and two years to do this. The Shah died under mysterious circumstances on a small island in the Caspian Sea that he had retreated to with his remaining loyal forces.

Meanwhile, the wealthy trading city of Urgench was still in the hands of Khwarazmian forces. The assault on Urgench proved to be the most difficult battle of the Mongol invasion and the city fell only after the defenders put up a stout defense, fighting block for block. Mongolian casualties were higher than normal, due to the unaccustomed difficulty of adapting Mongolian tactics to city fighting.

As usual, the artisans were sent back to Mongolia, young women and children were given to the Mongol soldiers as slaves, and the rest of the population was massacred. The Persian scholar Juvayni states that 50,000 Mongol soldiers were given the task of executing twenty-four Urgench citizens each, which would mean that 1.2 million people were killed. These numbers are considered logistically implausible by modern scholars, but the sacking of Urgench was no doubt a bloody affair.[68]

Georgia, Crimea, Kievan Rus and Volga Bulgaria

Gold dinar of Genghis Khan, struck at the Ghazna (Ghazni) mint, dated 1221/2

After the defeat of the Khwarazmian Empire in 1220, Genghis Khan gathered his forces in Persia and Armenia to return to the Mongolian steppes. Under the suggestion of Subutai, the Mongol army was split into two forces. Genghis Khan led the main army on a raid through Afghanistan and northern India towards Mongolia, while another 20,000 (two tumen) contingent marched through the Caucasus and into Russia under generals Jebe and Subutai. They pushed deep into Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Mongols defeated the kingdom of Georgia, sacked the Genoese trade-fortress of Caffa in Crimea and overwintered near the Black Sea. Heading home, Subutai’s forces attacked the allied forces of the Cuman–Kipchaks and the poorly coordinated 80,000 Kievan Rus’ troops led by Mstislav the Bold of Halych and Mstislav III of Kiev who went out to stop the Mongols’ actions in the area. Subutai sent emissaries to the Slavic princes calling for a separate peace, but the emissaries were executed. At the Battle of Kalka River in 1223, Subutai’s forces defeated the larger Kievan force. They may have been defeated by the neighbouring Volga Bulgars at the Battle of Samara Bend. There is no historical record except a short account by the Arab historian Ibn al-Athir, writing in Mosul some 1,800 kilometres (1,100 miles) away from the event.[71] Various historical secondary sources – Morgan, Chambers, Grousset – state that the Mongols actually defeated the Bulgars, Chambers even going so far as to say that the Bulgars had made up stories to tell the (recently crushed) Russians that they had beaten the Mongols and driven them from their territory.[71] The Russian princes then sued for peace. Subutai agreed but was in no mood to pardon the princes. Not only had the Rus put up strong resistance, but also Jebe – with whom Subutai had campaigned for years – had been killed just prior to the Battle of Kalka River.[72] As was customary in Mongol society for nobility, the Russian princes were given a bloodless death. Subutai had a large wooden platform constructed on which he ate his meals along with his other generals. Six Russian princes, including Mstislav III of Kiev, were put under this platform and crushed to death.

The Mongols learned from captives of the abundant green pastures beyond the Bulgar territory, allowing for the planning for conquest of Hungary and Europe. Genghis Khan recalled Subutai back to Mongolia soon afterwards. The famous cavalry expedition led by Subutai and Jebe, in which they encircled the entire Caspian Sea defeating all armies in their path, remains unparalleled to this day, and word of the Mongol triumphs began to trickle to other nations, particularly in Europe. These two campaigns are generally regarded as reconnaissance campaigns that tried to get the feel of the political and cultural elements of the regions. In 1225 both divisions returned to Mongolia. These invasions added Transoxiana and Persia to an already formidable empire while destroying any resistance along the way. Later under Genghis Khan’s grandson Batu and the Golden Horde, the Mongols returned to conquer Volga Bulgaria and Kievan Rus’ in 1237, concluding the campaign in 1240.

Western Xia and Jin dynasty

The vassal emperor of the Tanguts (Western Xia) had earlier refused to take part in the Mongol war against the Khwarezmid Empire. Western Xia and the defeated Jin dynasty formed a coalition to resist the Mongols, counting on the campaign against the Khwarazmians to preclude the Mongols from responding effectively.

In 1226, immediately after returning from the west, Genghis Khan began a retaliatory attack on the Tanguts. His armies quickly took Heisui, Ganzhou, and Suzhou (not the Suzhou in Jiangsu province), and in the autumn he took Xiliang-fu. One of the Tangut generals challenged the Mongols to a battle near Helan Mountains but was defeated. In November, Genghis laid siege to the Tangut city Lingzhou and crossed the Yellow River, defeating the Tangut relief army. According to legend, it was here that Genghis Khan reportedly saw a line of five stars arranged in the sky and interpreted it as an omen of his victory.

In 1227, Genghis Khan’s army attacked and destroyed the Tangut capital of Ning Hia and continued to advance, seizing Lintiao-fu, Xining province, Xindu-fu, and Deshun province in quick succession in the spring. At Deshun, the Tangut general Ma Jianlong put up a fierce resistance for several days and personally led charges against the invaders outside the city gate. Ma Jianlong later died from wounds received from arrows in battle. Genghis Khan, after conquering Deshun, went to Liupanshan (Qingshui County, Gansu Province) to escape the severe summer. The new Tangut emperor quickly surrendered to the Mongols, and the rest of the Tanguts officially surrendered soon after. Not happy with their betrayal and resistance, Genghis Khan ordered the entire imperial family to be executed, effectively ending the Tangut royal lineage.

Death and succession

Mongol Empire in 1227 at Genghis Khan’s death

Genghis Khan died within eight days of setting off for his final campaign against the Western Xia on 18 August 1227, according to the official History of Yuan commissioned during China’s Ming dynasty.[73] The date of his death is therefore said to have fallen on 25 August 1227, during the fall of Yinchuan. The exact cause of his death remains a mystery, and is variously attributed to illness, being killed in action or from wounds sustained in hunting or battle.[74][75][76] According to The Secret History of the Mongols, Genghis Khan fell from his horse while hunting and died because of the injury. The Galician–Volhynian Chronicle alleges he was killed by the Western Xia in battle, while Marco Polo wrote that he died after the infection of an arrow wound he received during his final campaign.[77] Later Mongol chronicles connect Genghis’s death with a Western Xia princess taken as war booty. One chronicle from the early 17th century even relates the legend that the princess hid a small dagger and stabbed or castrated him.[78] All of these legends were invented well after Genghis Khan’s death, however.[73] In contrast, a 2021 study found that the great leader likely died from bubonic plague, after investigating reports of the clinical signs exhibited by both the Khan and his army, which in turn matched the symptoms associated with the strain of plague present in Western Xia at that time.[79]

Genghis Khan (center) at the coronation of his son Ögedei, Rashid al-Din, early 14th century

Years before his death, Genghis Khan asked to be buried without markings, according to the customs of his tribe.[80] After he died, his body was returned to Mongolia and presumably to his birthplace in Khentii Aimag, where many assume he is buried somewhere close to the Onon River and the Burkhan Khaldun mountain (part of the Khentii mountain range). According to legend, the funeral escort killed anyone and anything across their path to conceal where he was finally buried. The Genghis Khan Mausoleum, constructed many years after his death, is his memorial, but not his burial site.

Before Genghis Khan died, he assigned Ögedei Khan as his successor. Genghis Khan left behind an army of more than 129,000 men; 28,000 were given to his various brothers and his sons. Tolui, his youngest son, inherited more than 100,000 men. This force contained the bulk of the elite Mongolian cavalry. By tradition, the youngest son inherits his father’s property. Jochi, Chagatai, Ögedei Khan, and Kulan’s son Gelejian received armies of 4,000 men each. His mother and the descendants of his three brothers received 3,000 men each. The title of Great Khan passed to Ögedei, the third son of Genghis Khan, making him the second Great Khan (Khagan) of the Mongol Empire. Genghis Khan’s eldest son, Jochi, died in 1226, during his father’s lifetime. Chagatai, Genghis Khan’s second son was meanwhile passed over, according to The Secret History of the Mongols, over a row just before the invasion of the Khwarezmid Empire in which Chagatai declared before his father and brothers that he would never accept Jochi as Genghis Khan’s successor due to questions about his elder brother’s parentage. In response to this tension and possibly for other reasons, Ögedei was appointed as successor.[81]

Later, his grandsons split his empire into khanates.[82] His descendants extended the Mongol Empire across most of Eurasia by conquering or creating vassal states in all of modern-day China, Korea, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and substantial portions of Eastern Europe and Southwest Asia. Many of these invasions repeated the earlier large-scale slaughters of local populations.

Organizational philosophy

Politics and economics

The Mongol Empire was governed by a civilian and military code, called the Yassa, created by Genghis Khan. The Mongol Empire did not emphasize the importance of ethnicity and race in the administrative realm, instead adopting an approach grounded in meritocracy.[83] The Mongol Empire was one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse empires in history, as befitted its size. Many of the empire’s nomadic inhabitants considered themselves Mongols in military and civilian life, including the Mongol people, Turkic peoples, and others. There were Khans of various non-Mongolian ethnicities such as Muhammad Khan.

There were tax exemptions for religious figures and, to some extent, teachers and doctors. The Mongol Empire practiced religious tolerance because Mongol tradition had long held that religion was a personal concept, and not subject to law or interference.[84] Genghis Khan was a Tengrist, but was religiously tolerant and interested in learning philosophical and moral lessons from other religions. He consulted Buddhist monks (including the Zen monk Haiyun), Muslims, Christian missionaries, and the Daoist monk Qiu Chuji.[85] Sometime before the rise of Genghis Khan, Ong Khan, his mentor and eventual rival, had converted to Nestorian Christianity. Various Mongol tribes were Shamanist, Buddhist or Christian. Religious tolerance was thus a well established concept on the Asian steppe.

Modern Mongolian historians say that towards the end of his life, Genghis Khan attempted to create a civil state under the Great Yassa that would have established the legal equality of all individuals, including women.[86] However, there is no evidence of this, or of the lifting of discriminatory policies towards sedentary peoples such as the Chinese. Women played a relatively important role in the Mongol Empire and in the family, for example Töregene Khatun was briefly in charge of the Mongol Empire while the next male leader Khagan was being chosen. Modern scholars refer to the alleged policy of encouraging trade and communication as the Pax Mongolica (Mongol Peace).

Genghis Khan realised that he needed people who could govern cities and states conquered by him. He also realised that such administrators could not be found among his Mongol people because they were nomads and thus had no experience governing cities. For this purpose Genghis Khan invited a Khitan prince, Chu’Tsai, who worked for the Jin and had been captured by the Mongol army after the Jin dynasty was defeated. Jin had risen to power by displacing the Khitan people. Genghis told Chu’Tsai, who was a lineal descendant of Khitan rulers, that he had avenged Chu’Tsai’s forefathers. Chu’Tsai responded that his father served the Jin dynasty honestly and so did he; also he did not consider his own father his enemy, so the question of revenge did not apply. This reply impressed Genghis Khan. Chu’Tsai administered parts of the Mongol Empire and became a confidant of the successive Mongol Khans.[citation needed]

Mural of siege warfare, Genghis Khan Exhibit in San Jose, California, US

Reenactment of Mongol battle

Military

Genghis Khan put absolute trust in his generals, such as Muqali, Jebe, and Subutai, and regarded them as close advisors, often extending them the same privileges and trust normally reserved for close family members. He allowed them to make decisions on their own when they embarked on campaigns far from the Mongol Empire capital Karakorum. Muqali, a trusted lieutenant, was given command of the Mongol forces against the Jin dynasty while Genghis Khan was fighting in Central Asia, and Subutai and Jebe were allowed to pursue the Great Raid into the Caucasus and Kievan Rus’, an idea they had presented to the Khagan on their own initiative. While granting his generals a great deal of autonomy in making command decisions, Genghis Khan also expected unwavering loyalty from them.

The Mongol military was also successful in siege warfare, cutting off resources for cities and towns by diverting certain rivers, taking enemy prisoners and driving them in front of the army, and adopting new ideas, techniques and tools from the people they conquered, particularly in employing Muslim and Chinese siege engines and engineers to aid the Mongol cavalry in capturing cities. Another standard tactic of the Mongol military was the commonly practiced feigned retreat to break enemy formations and to lure small enemy groups away from the larger group and defended position for ambush and counterattack.

Another important aspect of the military organization of Genghis Khan was the communications and supply route or Yam, adapted from previous Chinese models. Genghis Khan dedicated special attention to this in order to speed up the gathering of military intelligence and official communications. To this end, Yam waystations were established all over the empire.[87]

Impressions

Positive

Genghis Khan on the reverse of a Kazakh 100 tenge collectible coin.

Genghis Khan is credited with bringing the Silk Road under one cohesive political environment. This allowed increased communication and trade between the West, Middle East and Asia, thus expanding the horizons of all three cultural areas. Some historians have noted that Genghis Khan instituted certain levels of meritocracy in his rule, was tolerant of religions and explained his policies clearly to all his soldiers.[88] Genghis Khan had a notably positive reputation among some western European authors in the Middle Ages, who knew little concrete information about his empire in Asia.[89] The Italian explorer Marco Polo said that Genghis Khan «was a man of great worth, and of great ability, and valor»,[90][91] while philosopher and inventor Roger Bacon applauded the scientific and philosophical vigor of Genghis Khan’s empire,[16] and the famed writer Geoffrey Chaucer wrote concerning Cambinskan:[92]

The noble king was called Genghis Khan,

Who in his time was of so great renown,

That there was nowhere in no region,

So excellent a lord in all things

Portrait on a hillside in Ulaanbaatar, 2006

In Mongolia, Genghis Khan has meanwhile been revered for centuries by Mongols and many Turkic peoples because of his association with tribal statehood, political and military organization, and victories in war. As the principal unifying figure in Mongolian history, he remains a larger-than-life figure in Mongolian culture. He is credited with introducing the Mongolian script and creating the first written Mongolian code of law, in the form of the Yassa.

During the communist period in Mongolia, Genghis was often described by the government as a reactionary figure, and positive statements about him were avoided.[93] In 1962, the erection of a monument at his birthplace and a conference held in commemoration of his 800th birthday led to criticism from the Soviet Union and the dismissal of secretary Tömör-Ochir of the ruling Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party Central Committee.

In the early 1990s, the memory of Genghis Khan underwent a powerful revival, partly in reaction to its suppression during the Mongolian People’s Republic period. Genghis Khan became a symbol of national identity for many younger Mongolians, who maintain that the historical records written by non-Mongolians are unfairly biased against Genghis Khan and that his butchery is exaggerated, while his positive role is underrated.[94]

Mixed

There are conflicting views of Genghis Khan in China, which suffered a drastic decline in population.[95] The population of north China decreased from 50 million in the 1195 census to 8.5 million in the Mongol census of 1235–36; however, many were victims of plague. In Hebei province alone, 9 out of 10 were killed by the Black Death when Toghon Temür was enthroned in 1333.[96][dubious – discuss][better source needed] Northern China was also struck by floods and famine long after the war in northern China was over in 1234 and not killed by Mongols.[97][failed verification] The Black Death also contributed. By 1351, two out of three people in China had died of the plague, helping to spur armed rebellion,[98][failed verification] most notably in the form of the Red Turban Rebellions. However according to Richard von Glahn, a historian of Chinese economics, China’s population only fell by 15% to 33% from 1340 to 1370 and there is «a conspicuous lack of evidence for pandemic disease on the scale of the Black Death in China at this time.»[99] An unknown number of people also migrated to Southern China in this period,[100] including under the preceding Southern Song dynasty.[101]

The Mongols also spared many cities from massacre and sacking if they surrendered,[102] including Kaifeng,[103] Yangzhou,[104] and Hangzhou.[105] Ethnic Han and Khitan soldiers defected en masse to Genghis Khan against the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty.[106] Equally, while Genghis never conquered all of China, his grandson Kublai Khan, by completing that conquest and establishing the Yuan dynasty, is often credited with re-uniting China, and there is a great deal of Chinese artwork and literature praising Genghis as a military leader and political genius. The Yuan dynasty left an indelible imprint on Chinese political and social structures and a cultural legacy that outshone the preceding Jin dynasty.[107]

Negative

The conquests and leadership of Genghis Khan included widespread devastation and mass murder.[108][109][110][111] The targets of campaigns that refused to surrender would often be subject to reprisals in the form of enslavement and wholesale slaughter.[112] The second campaign against Western Xia, the final military action led by Genghis Khan, and during which he died, involved an intentional and systematic destruction of Western Xia cities and culture.[112] According to John Man, because of this policy of total obliteration, Western Xia is little known to anyone other than experts in the field because so little record is left of that society. He states that «There is a case to be made that this was the first ever recorded example of attempted genocide. It was certainly very successful ethnocide.»[110] In the conquest of Khwarezmia under Genghis Khan, the Mongols razed the cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, Herāt, Ṭūs, and Neyshābūr and killed the respective urban populations.[113] His invasions are considered the beginning of a 200-year period known in Iran and other Islamic societies as the «Mongol catastrophe.»[111] Ibn al-Athir, Ata-Malik Juvaini, Seraj al-Din Jozjani, and Rashid al-Din Fazl-Allah Hamedani, Iranian historians from the time of Mongol occupation, describe the Mongol invasions as a catastrophe never before seen.[111] A number of present-day Iranian historians, including Zabih Allah Safa, have likewise viewed the period initiated by Genghis Khan as a uniquely catastrophic era.[111] Steven R. Ward writes that the Mongol violence and depredations in the Iranian Plateau «killed up to three-fourths of the population… possibly 10 to 15 million people. Some historians have estimated that Iran’s population did not again reach its pre-Mongol levels until the mid-20th century.»[114]

Although the famous Mughal emperors were proud descendants of Genghis Khan and particularly Timur, they clearly distanced themselves from the Mongol atrocities committed against the Khwarizim Shahs, Turks, Persians, the citizens of Baghdad and Damascus, Nishapur, Bukhara and historical figures such as Attar of Nishapur and many other notable Muslims.[citation needed] However, Mughal Emperors directly patronized the legacies of Genghis Khan and Timur; together their names were synonymous with the names of other distinguished personalities particularly among the Muslim populations of South Asia.[115]

Depictions

16th century Ottoman miniature of Genghis Khan

Medieval

Unlike most emperors, Genghis Khan never allowed his image to be portrayed in paintings or sculptures.[116]

The earliest known images of Genghis Khan were produced half a century after his death, including the famous National Palace Museum portrait in Taiwan.[117][118] The portrait portrays Genghis Khan wearing white robes, a leather warming cap and his hair tied in braids, much like a similar depiction of Kublai Khan.[119] This portrait is often considered to represent the closest resemblance to what Genghis Khan actually looked like, though it, like all others renderings, suffers from the same limitation of being, at best, a facial composite.[120] Like many of the earliest images of Genghis Khan, the Chinese-style portrait presents the Great Khan in a manner more akin to a Mandarin sage than a Mongol warrior.[121] Other portrayals of Genghis Khan from other cultures likewise characterized him according to their particular image of him: in Persia he was portrayed as a Turkic sultan and in Europe he was pictured as an ugly barbarian with a fierce face and cruel eyes.[122] According to sinologist Herbert Allen Giles, a Mongol painter known as Ho-li-hosun (also known as Khorisun or Qooriqosun) was commissioned by Kublai Khan in 1278 to paint the National Palace Museum portrait.[123] The story goes that Kublai Khan ordered Khorisun, along with the other entrusted remaining followers of Genghis Khan, to ensure the portrait reflected the Great Khan’s true image.[124]

The only individuals to have recorded Genghis Khan’s physical appearance during his lifetime were the Persian chronicler Minhaj al-Siraj Juzjani and Chinese diplomat Zhao Hong.[125] Minhaj al-Siraj described Genghis Khan as «a man of tall stature, of vigorous build, robust in body, the hair of his face scanty and turned white, with cats’ eyes, possessed of dedicated energy, discernment, genius, and understanding, awe-striking…».[126] The chronicler had also previously commented on Genghis Khan’s height, powerful build, with cat’s eyes and lack of grey hair, based on the evidence of eyes witnesses in 1220, which saw Genghis Khan fighting in the Khorasan (modern day northwest Persia).[127][128] According to Paul Ratchnevsky, the Song dynasty envoy Zhao Hong who visited the Mongols in 1221,[129] described Genghis Khan as «of tall and majestic stature, his brow is broad and his beard is long».[127]