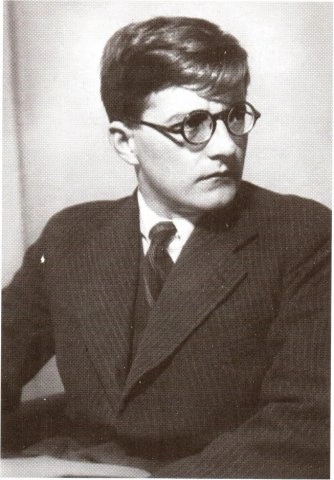

Дмитрий Шостакович — биография

Дмитрий Шостакович – композитор, пианист, педагог. Носил звание Народного артиста СССР, награжден многочисленными премиями СССР И РСФСР.

Мировая слава пришла к Дмитрию Шостаковичу в 20 лет, кода его Первую симфонию услышали не только на родине, но и в США и Европе. После этого прошло еще десять лет, и его музыка зазвучала со сцены ведущих театров мира. В сталинские времена его то поднимали до небес, то чуть ли не превращали во врага народа, но это не помешало ему стать крупнейшим композитором 20-го века, музыка которого будет жить вечно.

Детство

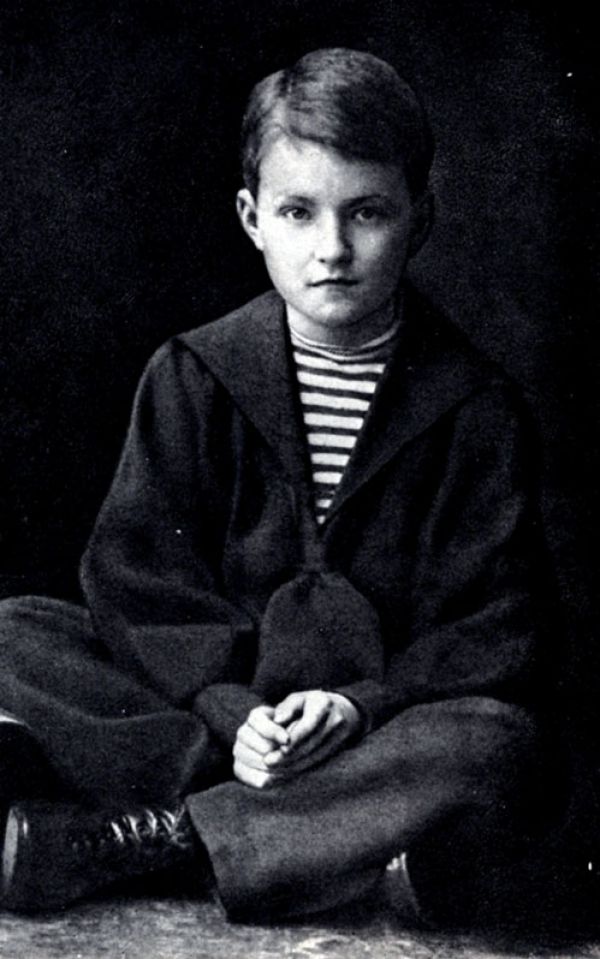

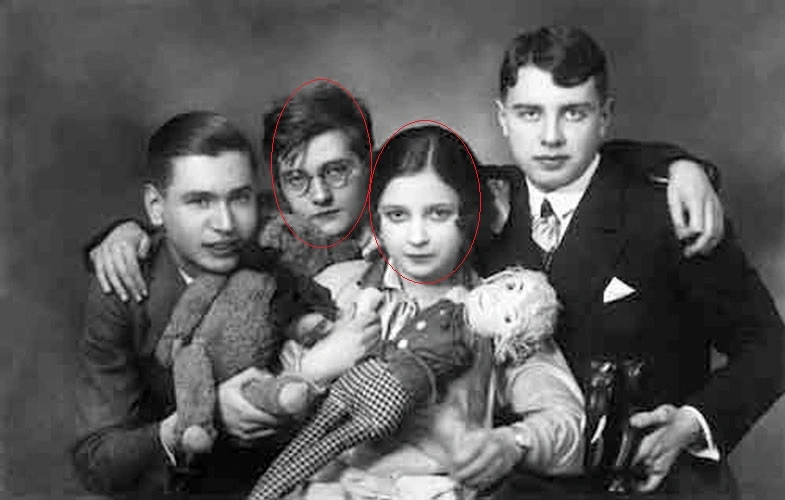

Родился Дмитрий Шостакович 25 сентября 1906 года в Санкт-Петербурге. Его отец – Дмитрий Болеславович, инженер-химик, страстно любил музыку. Мама Софья Шостакович окончила консерваторию по классу пианино, давала уроки игры на фортепиано для начинающих. На момент рождения Дмитрия в семье уже подрастала дочь Мария, которая стала известной пианисткой, после него родилась еще одна дочь – Зоя, ставшая ветеринаром. Все дети обладали музыкальными способностями, часто устраивали дома импровизированные концерты.

В 1916 году Диму отдали в коммерческую гимназию. Параллельно с этим он посещал частную музыкальную школу Игнатия Гляссера. Знаменитый музыкант научил Шостаковича отменно играть на пианино, но композиция не была его сильной стороной, поэтому предмет талантливый ученик постигал самостоятельно.

Дмитрий характеризовал Гляссера как самовлюбленного, скучного и неинтересного человека. Он проучился у него три года и бросил школу, хотя мама настаивала на продолжении обучения. Но Дмитрий всегда отличался твердостью характера, решения он менять не привык.

Началом творческой биографии Дмитрия можно считать пьесу «Траурный марш памяти жертв революции», написанную им под впечатлением от увиденной расправы над мальчиком. В 1917-м будущий композитор был свидетелем того, как казак разрубил ребенка саблей, и это навсегда осталось в его памяти.

Образование

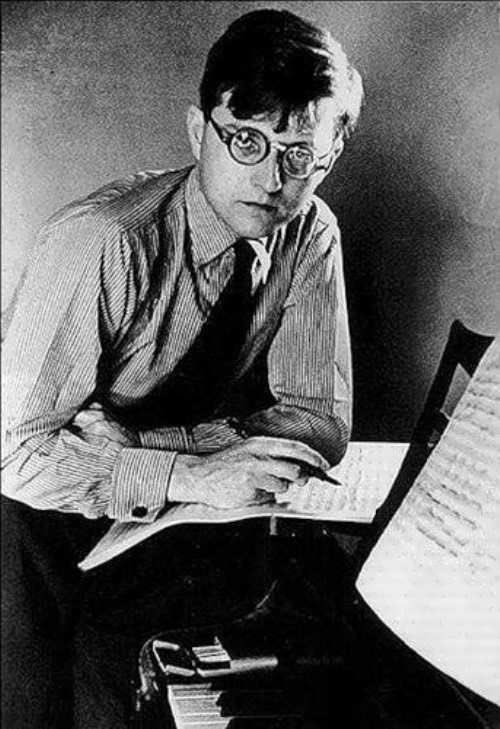

В 1919-м Дмитрий поступил в Петроградскую консерваторию. Буквально после первого курса он закончил работу над первым оркестровым сочинением – Скерцо fis-moll.

Спустя год он стал автором произведений для фортепиано «Три фантастических танца» и «Две басни Крылова». В те годы он познакомился с Борисом Асафьевым и Владимиром Щербачевым, членами «Кружка Анны Фогт».

Дмитрий был прилежным студентом, хоть и пришлось преодолевать множество трудностей. Он не наедался продуктовым пайком, который выдавали учащимся, часто голодал, но продолжал обучение. Шла зима, отопление в консерватории отсутствовало, многие болели и даже умирали.

Потом он напишет в своих мемуарах, что был слаб настолько, что даже не пытался ездить на учебу на трамвае. У него не было сил протискиваться в переполненный транспорт, поэтому юноша ходил пешком.

Семья очень бедствовала, особенно явным это стало после смерти отца. Дмитрий решил искать работу, и вскоре его приняли на должность тапёра в кинотеатр «Светлая лента». Он относился к своей работе с отвращением, платили за нее мало, сил требовалось много. Но приходилось терпеть из-за денег.

Прошел месяц, Дмитрий пошел за жалованием к хозяину кинотеатра Акиму Волынскому, но тот начал стыдить юношу, убеждать его, что искусство должно быть превыше всего, а материальная сторона не имеет значения.

Часть заработанных денег он все-таки выпросил, за остальным нужно было обращаться через суд. Прошло немного времени, имя Шостаковича уже начало набирать вес в музыкальном обществе, и его позвали на вечер памяти Волынского. Он пришел, и поведал всем о горьком опыте сотрудничества с этим человеком, чем привел в негодование организаторов мероприятия.

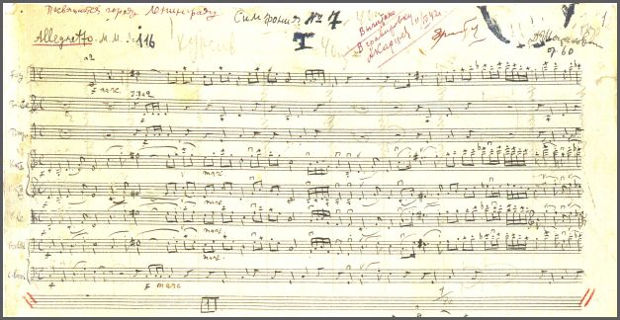

Документ об окончании консерватории по классу фортепиано Шостакович получил в 1923-м, а в 1925 году он завершил обучение по классу композиции. В качестве дипломной работы он представил Симфонию №1, которую впервые исполнили в Ленинграде в 1926-м. Спустя год симфонию услышали жители Берлина.

Могут быть знакомы

Творчество

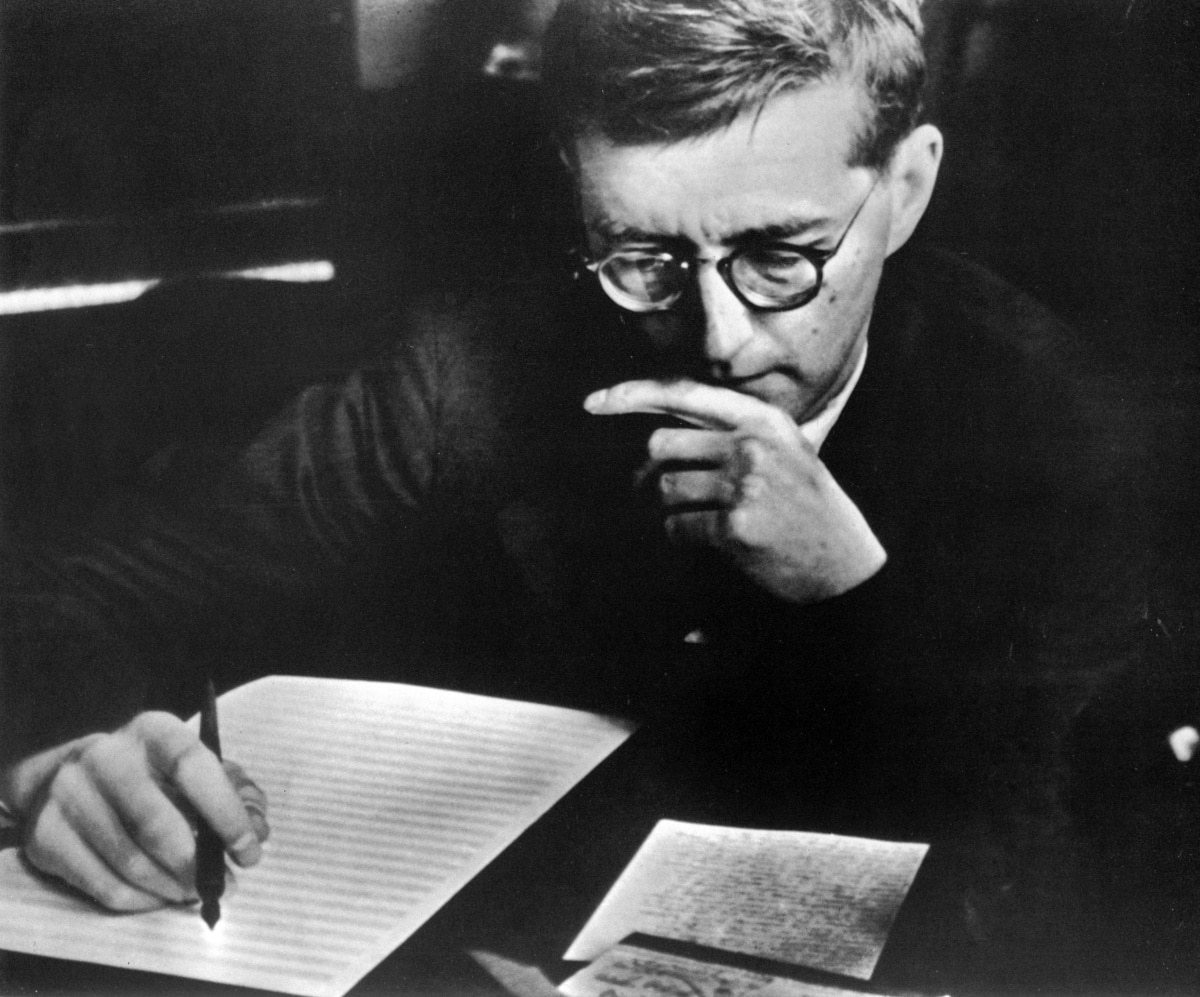

В 1932 году Дмитрий стал автором оперы «Леди Макбет Мценского уезда». Спустя несколько лет в копилке его работ появились пять симфоний. В 1938-м появилась «Джазовая сюита», которую чаще всего узнают по «Вальсу №2».

Сталину не понравилась музыка талантливого композитора, критики отреагировали мгновенно, в прессе появился ряд разгромных статей. Шостакович тогда окончил свою Четвертую симфонию, уже шли репетиции, но он остановил их буквально перед премьерой. Публика смогла услышать ее только в 60-х.

В годы войны партитура этой симфонии пропала, композитор считал ее навсегда утерянной, и после снятия блокады с Ленинграда начал ее восстанавливать по памяти. Но в 1946-м копии партий нашлись, и спустя 15 лет произведение прозвучало на публике.

Войну композитор встретил в Ленинграде, он как раз писал самую известную свою симфонию – Седьмую. Шостаковича эвакуировали в Куйбышев, он забрал с собой все наброски произведения, которое прославило его на весь мир. Симфонию №7 назвали «Ленинградской», она впервые прозвучала весной 1942-го в Куйбышеве.

После победы композитор пишет еще одну симфонию – Девятую, и представляет ее 3 ноября 1945-го, в родном Ленинграде. Шостакович становится одним из самых известных и востребованных композиторов, но длится это недолго. В 1948 году его музыку снова отнесли к разряду «чуждых советскому народу», а сам композитор попал в опалу вместе с Прокофьевым и Хачатуряном. Дмитрия уволили из Московской консерватории, лишили профессорского звания, которое он получил в 1939-м.

В 1949-м вышла кантата Шостаковича «Песнь о лесах», в которой он, поддавшись тенденциям того времени, расхваливал СССР и его триумфальное восстановление после войны. Критики и власти успокоились, Дмитрий получил за нее Сталинскую премию.

В 1950-м Шостакович пишет 24 Прелюдии и Фуги для фортепиано. На протяжении восьми лет он не издал ни одной симфонии, и только в 1953-м представил Десятую.

Спустя год выходит Одиннадцатая симфония, получившая название «1905 год». Вторая половина 50-х ознаменовалась работой над инструментальной музыкой, которая отличалась разнообразием формы и настроения.

Творческая биография Шостаковича продолжилась написанием еще четырех симфоний. Помимо этого он сочинял вокальные произведения и струнные квартеты. Последняя работа музыканта – Соната для альта и фортепиано.

Личная жизнь

Трудности преследовали композитора не только в профессиональном плане, но и в личной жизни. В 1923-м он познакомился с Татьяной Гливенко. Они любили друг друга, но в то время музыкант испытывал крайнюю нужду, поэтому так и не решился предложить ей руку и сердце. Восемнадцатилетняя девушка быстро нашла ему замену и вышла замуж. Спустя три года, когда дела композитора пошли успешно, он предложил любимой бросить мужа и сойтись с ним, но получил отказ.

Прошло немного времени, и Дмитрий женился на Нине Вазар. Они прожили в браке два десятка лет, стали родителями двоих детей. В 1938-м родился их первенец – сын Максим, спустя несколько лет семья пополнилась дочерью Галиной. В 1954-м композитор овдовел.

Второй раз Шостакович пошел в ЗАГС с Маргаритой Крайновой, сотрудницей ЦК ВЛКСМ. Однако они очень быстро поняли поспешность этого решения, и подали на развод.

В 1962-м композитор женился третий раз. Его избранницей стала Ирина Супинская, занимавшая должность редактора в издательстве «Советский композитор». Ее отец – репрессированный этнограф Антон Супинский. С Ириной композитор прожил всю оставшуюся жизнь.

Болезнь и смерть

Последние годы своей жизни Шостакович серьезно болел. Доктора не могли поставить диагноз, но пытались как-то помочь. Лечение заключалось в приеме курса витаминов, чтобы замедлить прогрессировавший недуг, но это мало помогало.

Потом все-таки композитору поставили диагноз — болезнь Шарко, или по-научному боковой амиотрофический склероз. Он лечился у американских и советских докторов, послушал совет Ростроповича и уехал в Курган, где принимал доктор Илизаров. В общей сложности он пробыл там 169 дней, лечение помогло ненадолго. Болезнь прогрессировала, несмотря на то, что он выполнял все предписания доктора, занимался специальной зарядкой и пил лекарства в соответствии с графиком. Единственной отдушиной для него в это время были походы на концерты, куда он отправлялся в сопровождении жены.

В 1975-м они поехали на концерт в Ленинград. В его программу включили романс Дмитрия Дмитриевича, и композитор очень хотел его услышать. Как назло, исполнитель от волнения не смог вспомнить начало, Шостакович разнервничался. Вернувшись домой, супруга вызвала музыканту неотложку, доктора которой диагностировали у него инфаркт и срочно госпитализировали.

В день смерти композитор собирался вместе с супругой смотреть футбольный матч по телевизору в больнице. Он попросил ее принести почту. Ирина отсутствовала совсем недолго, но когда вернулась, он уже скончался. Сердце Шостаковича остановилось 9 августа 1975 года.

Местом упокоения Дмитрия Шостаковича стало Новодевичье кладбище.

Слушать композиции

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Дмитрий Шостакович

В его судьбе было все – международное признание и отечественные ордена, голод и травля властей. Его творческое наследие беспрецедентно по жанровому охвату: симфонии и оперы, струнные квартеты и концерты, балеты и музыка к фильмам. Новатор и классик, творчески эмоциональный и человечески скромный – Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович. Композитор – классик 20 века, великий маэстро и яркий художник, на себе испытавший суровые времена, в которые ему пришлось жить и творить. Он близко к сердцу воспринимал беды своего народа, в его произведениях отчётливо слышится голос борца со злом и защитника против социальной несправедливости.

Краткую биографию Дмитрия Шостаковича и множество интересных фактов о композиторе читайте на нашей странице.

Краткая биография Шостаковича

В доме, где 12 сентября 1906 года пришел в этот мир Дмитрий Шостакович, сейчас находится школа. А тогда – Городская проверочная палатка, которой заведовал его отец. Из биографии Шостаковича мы узнаём, что в 10 лет, будучи гимназистом, Митя принимает категорическое решение писать музыку и всего 3 годами спустя становится студентом консерватории.

Начало 20-х было сложным – голодное время усугубила его тяжелая болезнь и внезапная смерть отца. Большое участие в судьбе талантливого студента проявил директор консерватории А.К. Глазунов, назначивший ему повышенную стипендию и организовавший послеоперационную реабилитацию в Крыму. Шостакович вспоминал, что ходил пешком на учебу только лишь из-за того, что был не в силах влезть в трамвай. Несмотря на сложности со здоровьем, в 1923 он выпускается как пианист, а в 1925 – как композитор. Всего лишь два года спустя его Первую симфонию играют лучшие мировые оркестры под руководством Б. Вальтера и А. Тосканини.

Обладая невероятной работоспособностью и самоорганизацией, Шостакович стремительно пишет свои следующие произведения. В личной жизни композитор был не склонен принимать поспешных решений. До такой степени, что позволил женщине, с которой его 10 лет связывали близкие отношения, Татьяне Гливенко, выйти замуж за другого из-за своей неготовности решиться на брак. Предложение он сделал астрофизику Нине Варзар, и неоднократно переносившееся бракосочетание наконец состоялось в 1932 году. Через 4 года появилась дочь Галина, еще через 2 – сын Максим. Согласно биографии Шостаковича с 1937 года он становится преподавателем, а затем и профессором консерватории.

Война принесла не только печали и горести, но и новое трагическое вдохновение. Наравне со своими студентами, Дмитрий Дмитриевич хотел идти на фронт. Когда не пустили – хотел остаться в любимом окруженном фашистами Ленинграде. Но его с семьей почти насильно вывезли в Куйбышев (Самару). В родной город композитор уже не вернулся, после эвакуации поселившись в Москве, где продолжил преподавательскую деятельность. Изданное в 1948 году постановление «Об опере «Великая дружба» В. Мурадели» объявило Шостаковича «формалистом», а его творчество – антинародным. В 1936 его уже пытались поименовать «врагом народа» после критических статей в «Правде» о «Леди Макбет Мценского уезда» и «Светлом ручье». Та ситуация фактически поставила крест на дальнейших изысканиях композитора в жанрах оперы и балета. Но теперь на него обрушилась не только общественность, но сама государственная машина: его уволили из консерватории, лишили профессорского статуса, перестали публиковать и исполнять сочинения. Однако долго не замечать творца подобного уровня было невозможно. В 1949 Сталин лично попросил его поехать в США с другими деятелями культуры, вернув за согласие все отобранные привилегии, в 1950 он получает Сталинскую премию за кантату «Песнь о лесах», а в 1954 – становится Народным артистом СССР.

В конце того же года внезапно скончалась Нина Владимировна. Шостакович тяжело переживал эту утрату. Он был силен своей музыкой, но слаб и беспомощен в повседневных вопросах, бремя которых всегда несла его жена. Вероятно, именно желанием вновь упорядочить быт объясняется его новый брак всего полтора года спустя. Маргарита Кайнова не разделяла интересы мужа, не поддерживала его круг общения. Брак был недолгим. В это же время композитор познакомился с Ириной Супинской, которая через 6 лет стала его третьей и последней женой.

Она была без малого на 30 лет моложе, но об этом союзе почти не злословили за спиной — ближнее окружение четы понимало, что 57-летний гений постепенно теряет здоровье. Прямо на концерте у него начала отниматься правая рука, а затем в США был поставлен окончательный диагноз – болезнь неизлечима. Даже когда Шостаковичу с трудом давался каждый шаг, это не остановило его музыку. Последним днем его жизни стало 9 августа 1975 года.

Интересные факты о Шостаковиче

- Шостакович был страстным болельщиком футбольного клуба «Зенит» и даже вел тетрадь учета всех игр и голов. Другими его увлечениям были карты – он все время раскладывал пасьянсы и с удовольствием играл в «кинга», притом исключительно на деньги, и пристрастие к курению.

- Любимым блюдом композитора были домашние пельмени из трех сортов мяса.

- Дмитрий Дмитриевич работал без фортепиано, он садился за стол и записывал ноты на бумагу сразу в полной оркестровке. Он обладал такой уникальной работоспособностью, что мог за короткое время полностью переписать свое сочинение.

- Шостакович длительно добивался возвращения на сцену «Леди Макбет Мценского уезда». В середине 50-х он сделал новую редакцию оперы, назвав ее «Катерина Измайлова». Несмотря на прямое обращение к В. Молотову, постановка была вновь запрещена. Только в 1962 году опера увидела сцену. В 1966 году вышел одноименный фильм с Галиной Вишневской в заглавной роли.

- Для того чтобы выразить в музыке «Леди Макбет Мценского уезда» все бессловесные страсти, Шостакович использовал новые приемы, когда инструменты пищали, спотыкались, шумели. Он создал символические звуковые формы, наделяющие персонажей уникальной аурой: альтовая флейта для Зиновия Борисовича, контрабас для Бориса Тимофеевича, виолончель для Сергея, гобой и кларнет – для Катерины.

- Катерина Измайлова — одна из самых популярных партий оперного репертуара.

- Шостакович входит в число 40 самых исполняемых оперных композиторов мира. Ежегодно дается более 300 представлений его опер.

- Шостакович – единственный из «формалистов», который покаялся и фактически отрекся от своего предыдущего творчества. Это вызвало разное отношение к нему со стороны коллег, а композитор пояснил свою позицию тем, что иначе бы ему больше не дали работать.

- Первую любовь композитора, Татьяну Гливенко, тепло принимали мать и сестры Дмитрия Дмитриевича. Когда она вышла замуж, Шостакович вызвал ее письмом из Москвы. Она приехала в Ленинград и остановилась в доме Шостаковичей, но он так и не смог решиться на то, чтобы уговорить ее расстаться с мужем. Он оставил попытки возобновить отношения только после известия о беременности Татьяны.

- Одна из самых известных песен, написанных Дмитрием Дмитриевичем, прозвучала в фильме 1932 года «Встречный». Она так и называется – «Песня о встречном».

- В течение многих лет композитор был депутатом Верховного Совета СССР, вел прием «избирателей» и, как мог, пытался решить их проблемы.

- Нина Васильевна Шостакович очень любила играть на фортепиано, но после замужества – перестала, объясняя это тем, что супруг не любит дилетантства.

- Максим Шостакович вспоминает, что плачущим он видел отца дважды – когда умерла его мать и когда того заставили вступить в партию.

- В опубликованных воспоминаниях детей, Галины и Максима, композитор предстает чутким, заботливым и любящим отцом. Несмотря на свою постоянную занятость, он проводил с ними время, водил к врачу и даже играл на пианино популярные танцевальные мелодии во время домашних детских праздников. Видя, что дочери не нравятся занятия на инструменте, он позволил ей больше не учиться игре на фортепиано.

- Ирина Антоновна Шостакович вспоминала, что во время эвакуации в Куйбышев они с Шостаковичем жили на одной улице. Он писал там Седьмую симфонию, а ей было всего 8 лет.

- Биография Шостаковича гласит, что в 1942 году композитор участвовал в конкурсе на сочинение гимна Советского Союза. Также в конкурсе участвовал и А. Хачатурян. Выслушав все произведения, Сталин попросил двух композиторов сочинить гимн совместно. Они это сделали, и их произведение вошло в финал, наряду с гимнами каждого из них, вариантов А. Александрова и грузинского композитора И. Туския. В конце 1943 года был сделан окончательный выбор, им стала музыка А. Александрова, ранее известная как «Гимн партии большевиков».

- Шостакович обладал уникальным слухом. Присутствуя на оркестровых репетициях своих произведений, он слышал неточности в исполнении даже одной ноты.

- В 30-е композитор каждую ночь ожидал ареста, поэтому ставил у кровати чемоданчик с вещами первой необходимости. В те годы были расстреляны многие люди из его окружения, включая ближайшее — режиссер Мейерхольд, маршал Тухачевский. Тесть и муж старшей сестры были сосланы в лагерь, а сама Мария Дмитриевна — в Ташкент.

- Восьмой квартет, написанный в 1960 году, композитор посвятил своей памяти. Он открывается нотной анаграммой Шостаковича (D-Es-C-H) и содержит в себе темы многих его произведений. «Неприличное» посвящение пришлось изменить на «Памяти жертв фашизма». Эту музыку он сочинял в слезах после вступления в партию.

Творчество Дмитрия Шостаковича

Самое раннее из сохранившихся сочинений композитора — Скерцо fis-moll датировано годом поступления в консерваторию. Во время учебы, будучи еще и пианистом, Шостакович много писал для этого инструмента. Выпускной работой стала Первая симфония. Это произведение ждал невероятный успех, а о юном советском композиторе узнал весь мир. Воодушевление от собственного триумфа вылилось в следующие симфонии – Вторую и Третью. Их объединяет необычность формы – в обоих есть хоровые части на стихи актуальных поэтов того времени. Однако сам автор позже признал эти работы неудачными. С конца 20-х Шостакович пишет музыку для кино и драматического театра – ради заработка, а не повинуясь творческому порыву. Всего им оформлено более 50 фильмов и спектаклей выдающихся режиссеров – Г. Козинцева, С. Герасимова, А. Довженко, Вс. Мейерхольда.

В 1930 году состоялись премьеры его первых оперы и балета. И «Нос» по повести Гоголя, и «Золотой век» на тему приключений советской футбольной команды на враждебном западе получили плохие отзывы критики и после чуть более десятка представлений на долгие годы покинули сцену. Неудачным оказался и следующий балет, «Болт». В 1933 композитор исполнил партию фортепиано на премьере своего дебютного Концерта для фортепиано с оркестром, в котором вторая солирующая партия была отдана трубе.

В течение двух лет создавалась опера «Леди Макбет Мценского уезда», которая была исполнена в 1934 году почти одновременно в Ленинграде и Москве. Постановщиком столичного спектакля был В.И. Немирович-Данченко. Спустя год «Леди Макбет…» перешагнула границы СССР, покоряя подмостки Европы и Америки. От первой советской классической оперы публика была в восторге. Как и от нового балета композитора «Светлый ручей», имеющего плакатное либретто, но наполненного великолепной танцевальной музыкой. Конец успешной сценической жизни этих спектаклей был положен в 1936 году после посещения оперы Сталиным и последовавшими статьями в газете «Правда» «Сумбур вместо музыки» и «Балетная фальшь».

На конец того же года была запланирована премьера новой Четвертой симфонии, в Ленинградской филармонии шли оркестровые репетиции. Однако концерт был отменен. Наступивший 1937 не нес в себе никаких радужных ожиданий – в стране набирали ход репрессии, расстреляли одного из близких Шостаковичу людей – маршала Тухачевского. Эти события наложили отпечаток на трагическую музыку Пятой симфонии. На премьере в Ленинграде слушатели, не сдерживая слез, устроили сорокаминутную овацию композитору и оркестру под управлением Е. Мравинского. Тот же состав исполнителей два года спустя сыграл Шестую симфонию — последнее крупное довоенное сочинение Шостаковича.

9 августа 1942 года состоялось беспрецедентное событие – исполнение в Большом зале Ленинградской консерватории Седьмой («Ленинградской») симфонии. Выступление транслировалось по радио на весь мир, потрясая мужеством жителей несломленного города. Композитор писал эту музыку и до войны, и в первые месяцы блокады, закончив в эвакуации. Там же, в Куйбышеве, 5 марта 1942 года оркестром Большого театра симфония была сыграна впервые. В годовщину начала Великой Отечественной войны она исполнялась в Лондоне. 20 июля 1942 года, на следующий день после нью-йоркской премьеры симфонии (дирижировал А. Тосканини) журнал «Тайм» вышел с портретом Шостаковича на обложке.

Восьмую симфонию, написанную в 1943 году, критиковали за трагическое настроение. А Девятую, премьера которой прошла в 1945 – напротив, за «легковесность». После войны композитор работает над музыкой к кинофильмам, сочинениями для фортепиано и струнных. 1948 год поставил крест на исполнении произведений Шостаковича. Со следующей симфонией слушатели познакомились только в 1953. А Одиннадцатая симфония в 1958 году имела невероятный зрительский успех и была удостоена Ленинской премии, после чего композитора полностью реабилитировала резолюция ЦК об отмене «формалистического» постановления. Двенадцатая симфония посвящалась В.И. Ленину, а последующие две имели необычную форму: они были созданы для солистов, хора и оркестра – Тринадцатая на стихи Е. Евтушенко, Четырнадцатая – на стихи разных поэтов, объединенные темой смерти. Пятнадцатая симфония, ставшая последней, родилась летом 1971 года, ее премьерой дирижировал сын автора, Максим Шостакович.

В 1958 году композитор берется за оркестровку «Хованщины». Его версии оперы суждено будет стать самой востребованной в последующие десятилетия. Шостакович, опираясь на восстановленный авторский клавир, сумел очистить музыку Мусоргского от наслоений и интерпретаций. Подобная работа была им проведена и двадцатью годами ранее с «Борисом Годуновым». В 1959 году состоялась премьера единственной оперетты Дмитрия Дмитриевича – «Москва, Черемушки», которая вызвала удивление и принималась восторженно. Через три года по мотивам произведения вышел популярный музыкальный фильм. В 60-70 композитор пишет 9 струнных квартетов, много работает над вокальными произведениями. Последним сочинением советского гения была Соната для альта и фортепиано, впервые исполненная уже после его кончины.

Музыка Шостаковича в кино

Дмитрий Дмитриевич написал музыку к 33 фильмам. «Катерина Измайлова» и «Москва, Черемушки» были экранизированы. Тем не менее он всегда говорил своим ученикам, что писать для кино можно только под угрозой голодной смерти. Несмотря на то что киномузыку он сочинял исключительно ради гонорара, в ней немало удивительных по красоте мелодий.

Среди его фильмов:

- «Встречный», режиссёры Ф. Эрмлер и С. Юткевич, 1932

- Трилогия о Максиме режиссёров Г. Козинцева и Л. Трауберга, 1934-1938

- «Человек с ружьём», режиссёр С. Юткевич, 1938

- «Молодая гвардия», режиссёр С. Герасимов, 1948

- «Встреча на Эльбе», режиссёр Г. Александров, 1948

- «Овод», режиссёр А. Файнциммер, 1955

- «Гамлет», режиссёр Г. Козинцев, 1964

- «Король Лир», режиссёр Г. Козинцев, 1970

Современная киноиндустрия часто использует музыку Шостаковича для создания музыкального оформления картин:

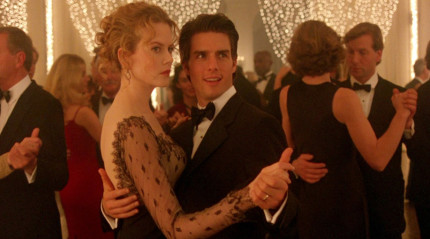

| Произведение | Фильм |

| Сюита для джаз-оркестра № 2 | «Бэтмен против Супермена: На заре справедливости», 2016 |

| «Нимфоманка: Часть 1», 2013 | |

| «С широко закрытыми глазами», 1999 | |

| Концерт для фортепиано с оркестром № 2 | «Шпионский мост», 2015 |

| Сюита из музыки к кинофильму «Овод» | «Возмездие», 2013 |

| Симфония №10 | «Дитя человеческое», 2006 |

К фигуре Шостаковича и сегодня относятся неоднозначно, называя его то гением, то конъюнктурщиком. Он никогда открыто не высказывался против происходящего, понимая, что тем самым потерял бы возможность писать музыку, которая была главным делом его жизни. Эта музыка даже спустя десятилетия красноречиво говорит как о личности композитора, так и о его отношении к своей страшной эпохе.

Понравилась страница? Поделитесь с друзьями:

Фильм о Шостаковиче

Содержание статьи

- Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович. Детство и юность

- «Творческий ответ художника на справедливую критику»

- «Шостаковичу, в чью эпоху я живу на Земле»

- Произведения Дмитрия Шостаковича

- Оперы

- Балеты

- Музыкальная комедия

- Для солистов, хора и оркестра

- Поэмы

- Для хора и оркестра

- Для оркестра

- Сюиты

- Концерты для инструмента с оркестром

- Для духового оркестра

- Для джаз-оркестра

- Камерно-инструментальные ансамбли

- Для скрипки и фортепиано

- Для альта и фортепиано

- Для виолончели и фортепиано

- Для фортепиано

- Для 2 фортепиано

- Для голоса с оркестром

- Для хора с фортепиано

- Для хора a cappella

- Для голоса, скрипки, виолончели и фортепиано

- Для голоса с фортепиано

- Для солистов, хора и фортепиано

- Музыка к спектаклям драматических театров

- Музыка к кинофильмам

- Инструментовка сочинений других авторов

Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович. Детство и юность

Дмитрий Шостакович родился 25 сентября 1906 года. Автор величайших симфонических произведений рано стал известным. Уже в 20 лет Шостакович написал свою Первую симфонию, которая звучала в концертных залах всего мира.

Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович родился в Санкт-Петербурге, его отец был простым инженером, но, хоть и не занимался музыкой профессионально, ценил искусство. Зато мать Дмитрия Шостаковича была настоящей пианисткой, именно она дала сыну первые уроки игры на музыкальном инструменте, которым стало фортепиано. Юношество Дмитрий Шостакович провел за занятиями в частной музыкальной школе. Уже там преподаватели заметили его Великолепный талант и абсолютный слух. Потом молодой музыкант поступил в Петроградскую консерваторию, окончил факультет композиции.

«Творческий ответ художника на справедливую критику»

Шостакович работал в кинотеатре тапером. Даже там во время показа фильмов он всегда экспериментировал с музыкой. Первая симфония Шостаковича была его дипломной работой. Слушатели в Ленинграде встретили ее бурными овациями, Дмитрию Шостаковичу пришлось пять раз выходить на поклон. Это произведение получило мировую известность. В 1932 году Дмитрий Шостакович создал оперу «Катерина Измайлова» по сюжету «Леди Макбет Мценского уезда». Опера была популярной в Москве и Петербурге, её тепло встречали также в Европе и Северной Америке. После того, как в зрительном зале оказался Иосиф Сталин, произведение признали антинародным, но Шостакович не сдался и продолжал писать музыку.

Его симфония №5 была встречена критиками уже тепло. Сталин назвал её «деловым творческим ответом советского художника на справедливую критику».

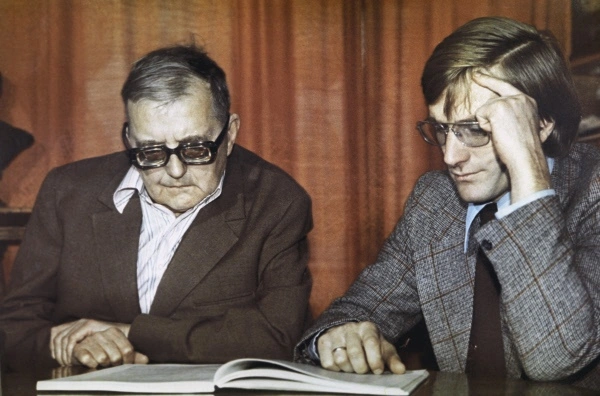

Фото: filarmonia.kh.ua

Первые месяцы Великой Отечественной войны Шостакович провел в Ленинграде. Кроме работы в Консерватории, он служил в добровольной пожарной дружине. Под впечатлением от одного из ночных дежурств он написал знаменитую Ленинградскую симфонию. В 1942 году ее исполнил оркестр Большого театра. Произведения Шостаковича звучали в блокадном Ленинграде и поддерживали людей в самые трудные времена.

В 1948 году Дмитрия Шостаковича обвинили в пресмыкании перед Западом, а его музыку запретили к прослушиванию. Правда уже через год запрет сняли, а композитор уехал в США в составе группы деятелей культуры Советского Союза

«Шостаковичу, в чью эпоху я живу на Земле»

Дмитрия Шостаковича ценили в творческой среде. Анна Ахматова подарила ему свою книгу с посвящением «Дмитрию Дмитриевичу Шостаковичу, в чью эпоху я живу на Земле».

Шостакович писал балеты и оперы, создавал симфонии и музыку к фильмам.

Последние годы жизни композитора были омрачены тяжелой болезнью. Дмитрий Шостакович скончался в Москве в 1975 году и покоится на Новодевичьем кладбище.

Фото: culture.ru

Произведения Дмитрия Шостаковича

Оперы

- Нос (по Н. В. Гоголю, либретто Е. И. Замятина, Г. И. Ионина, А. Г. Прейса и автора, 1928, поставлена в 1930, Ленинградский Малый оперный театр)

- Леди Макбет Мценского уезда (Катерина Измайлова, по Н. С. Лескову, либретто Прейса и автора, 1932, поставлена в 1934, Ленинградский Малый оперный театр, Московский музыкальный театр им. В. И. Немировича-Данченко; новая редакция в 1956, посвящена Н. В. Шостакович, поставлена в 1963, Московский музыкальный театр им. К. С. Станиславского и В. И. Немировича-Данченко)

- Игроки (по Гоголю, не окончена, концертное исполнение в 1978, Ленинградская филармония)

Балеты

- Золотой век (1930, Ленинградский театр оперы и балета)

- Болт (1931, там же)

- Светлый ручей (1935, Ленинградский Малый оперный театр)

Музыкальная комедия

- Москва, Черемушки (либретто В. З. Масса и М. А. Червинского, 1958, поставлена 1959, Московский театр оперетты)

Для солистов, хора и оркестра

- оратория Песнь о лесах (слова Е. Я. Долматовского, 1949)

- кантата Над Родиной нашей солнце сияет (слова Долматовского, 1952)

Поэмы

- Поэма о Родине (1947)

- Казнь Степана Разина (слова Е. А. Евтушенко, 1964)

Для хора и оркестра

- Гимн Москве (1947)

- Гимн РСФСР (слова С. П. Щипачёва, 1945)

Для оркестра

- 15 симфоний (№ 1, f-moll op. 10, 1925; № 2 — Октябрю, с заключительным хором на слова А. И. Безыменского, H-dur op. 14, 1927; № 3, Первомайская, для оркестра и хора, слова С. И. Кирсанова, Es-dur op. 20, 1929; .№ 4, c-moll op. 43, 1936; № 5, d-moll op. 47, 1937; № 6, h-moll op. 54, 1939; № 7, C-dur op. 60, 1941, посвящена городу Ленинграду; № 8, c-moll op. 65, 1943, посвящена Е. А. Мравинскому; № 9, Es-dur op. 70, 1945; № 10, e-moll op. 93, 1953; № 11, 1905 год, g-moll op. 103, 1957; № 12-1917 год, посвящена памяти В. И. Ленина, d-moll ор. 112, 1961; № 13, b-moll op. 113, слова Е. А. Евтушенко, 1962; № 14, op. 135, слова Ф. Гарсиа Лорки, Г. Аполлинера, В. К. Кюхельбекера и Р. М. Рильке, 1969, посвящена Б. Бриттену; № 15, op. 141, 1971)

- симфоническая поэма Октябрь (op. 131, 1967)

- увертюра на русские и киргизские народные темы (ор. 115, 1963)

- Праздничная увертюра (1954)

- 2 скерцо (ор. 1, 1919; ор. 7, 1924)

- увертюра к опере «Христофор Колумб» Дресселя (ор. 23, 1927)

- 5 фрагментов (ор. 42, 1935)

- Новороссийские куранты (1960)

- Траурно-триумфальный прелюд памяти героев Сталинградской битвы (ор. 130, 1967)

Сюиты

- из оперы Нос (ор. 15-а, 1928)

- из музыки к балету Золотой век (ор. 22-а, 1932)

- 5 балетных сюит (1949; 1951; 1952; 1953; op. 27-a, 1931)

- из музыки к кинофильмам Златые горы (ор. 30-а, 1931)

- Встреча на Эльбе (ор. 80-а, 1949)

- Первый эшелон (ор. 99-а, 1956)

- из музыки к трагедии «Гамлет» Шекспира (ор. 32-а, 1932)

Концерты для инструмента с оркестром

- 2 для фортепьяно (c-moll ор. 35, 1933; F-dur op. 102, 1957)

- 2 для скрипки (a-moll op. 77, 1948, посвящён Д. Ф. Ойстраху; cis-moll ор. 129, 1967, посвящён ему же)

- 2 для виолончели (Es-dur ор. 107, 1959; G-dur op. 126, 1966)

Для духового оркестра

- Марш советской милиции (1970)

Для джаз-оркестра

- сюита (1934)

Камерно-инструментальные ансамбли

Для скрипки и фортепиано

- соната (d-moll ор. 134, 1968, посвящена Д. Ф. Ойстраху)

Для альта и фортепиано

- соната (ор. 147, 1975)

Для виолончели и фортепиано

- соната (d-moll ор. 40, 1934, посвящена В. Л. Кубацкому)

- 3 пьесы (ор. 9, 1923-24)

- 2 фортепианных трио (ор. 8, 1923; op. 67, 1944, памяти И. П. Соллертинского)

- 15 струн. квартетов (№ l, C-dur op. 49, 1938: № 2, A-dur op. 68, 1944, посвящён В. Я. Шебалину; № 3, F-dur ор. 73, 1946, посвящён квартету им. Бетховена; № 4, D-dur op. 83, 1949; № 5, B-dur op. 92, 1952, посвящён квартету им. Бетховена; № 6, G-dur ор. 101, 1956; № 7, fis-moll op. 108, 1960, посвящён памяти Н. В. Шостакович; № 8, c-moll op. 110, 1960, посвящён памяти жертв фашизма и войны; № 9, Es-dur ор. 117, 1964, посвящён И. А. Шостакович; № 10, As-dur op. 118, 1964, посвящён М. С. Вайнбергу; № 11, f-moll ор. 122, 1966, памяти В. П. Ширииского; № 12, Des-dur ор. 133, 1968, поcвящён Д. M. Цыганову; № 13, b-moll, 1970, поcвящён В. В. Борисовскому; № 14, Fis-dur op. 142, 1973, поcвящён С. П. Ширинскому; №15, es-moll ор. 144, 1974)

- фортепианный квинтет (g-moll op. 57, 1940)

- 2 пьесы для струнного октета (ор. 11, 1924-25)

Для фортепиано

- 2 сонаты (C-dur ор. 12, 1926; h-moll op. 61, 1942, поcвящена Л. Н. Николаеву)

- 24 прелюдии (ор. 32, 1933)

- 24 прелюдии и фуги (op. 87, 1951)

- 8 прелюдий (op. 2, 1920)

- Афоризмы (10 пьес, op. 13, 1927)

- 3 фантастических танца (op. 5, 1922)

- Детская тетрадь (6 пьес, op. 69, 1945)

- Танцы кукол (7 пьес, без op., 1952)

Для 2 фортепиано

- концертино (ор. 94, 1953)

- сюита (ор. 6, 1922, поcвящена памяти Д. Б. Шостаковича)

Для голоса с оркестром

- 2 басни Крылова (ор. 4, 1922)

- 6 романсов на слова японских поэтов (ор. 21, 1928-32, поcвящён Н. В. Варзар)

- 8 английских и американских народных песен на тексты Р. Бёрнса и др. в переводе С. Я. Маршака (без op., 1944)

Для хора с фортепиано

- Клятва наркому (cлова В. М. Саянова, 1942)

Для хора a cappella

- Десять поэм на слова русских революционных поэтов (ор. 88, 1951)

- 2 обработки русских народных песен (ор. 104, 1957)

- Верность (8 баллад на слова Е. А. Долматовского, ор. 136, 1970)

Для голоса, скрипки, виолончели и фортепиано

- 7 романсов на слова А. А. Блока (ор. 127, 1967)

- вокальный цикл «Из еврейской народной поэзии» для сопрано, контральто и тенора с фортепьяно (ор. 79, 1948)

Для голоса с фортепиано

- 4 романса на слова А. С. Пушкина (ор. 46, 1936)

- 6 романсов на слова У. Рэли, Р. Бёрнса и У. Шекспира (ор. 62, 1942; вариант с камерным оркестра)

- 2 песни на слова М. А. Светлова (ор. 72, 1945)

- 2 романса на слова М. Ю. Лермонтова (ор. 84, 1950)

- 4 песни на слова Е. А. Долматовского (ор. 86, 1951)

- 4 монолога на слова А. С. Пушкина (ор. 91, 1952)

- 5 романсов на слова Е. А. Долматовского (ор. 98, 1954)

- Испанские песни (ор. 100, 1956)

- 5 сатир на слова С. Чёрного (ор. 106, 1960)

- 5 романсов на слова из журнала «Крокодил» (ор. 121, 1965)

- Весна (слова Пушкина, ор. 128, 1967)

- 6 стихотворений М. И. Цветаевой (ор. 143, 1973; вариант с камерным оркестром)

- сюита Сонеты Микеланджело Буонарроти (ор. 148, 1974; вариант с камерным оркестром)

- 4 стихотворения капитана Лебядкина (слова Ф. М. Достоевского, ор. 146, 1975)

Для солистов, хора и фортепиано

- обработки русских народных песен (1951)

Музыка к спектаклям драматических театров

- «Клоп» Маяковского (1929, Москва, Театр им. В. Э. Мейерхольда)

- «Выстрел» Безыменского (1929, Ленинградский ТРАМ)

- «Целина» Горбенко и Львова (1930, там же)

- «Правь, Британия!» Пиотровского (1931, там же)

- «Гамлет» Шекспира (1932, Москва, Театр им. Вахтангова)

- «Человеческая комедия» Сухотина, по О. Бальзаку (1934, там же)

- «Салют, Испания» Афиногенова (1936, Ленинградский театр драмы им. Пушкина)

- «Король Лир» Шекспира (1941, Ленинградский Большой драматический театр им. Горького)

Музыка к кинофильмам

- «Новый Вавилон» (1929)

- «Одна» (1931)

- «Златые горы» (1931)

- «Встречный» (1932)

- «Любовь и ненависть» (1935)

- «Подруги» (1936)

- «Юность Максима» (1935)

- «Возвращение Максима» (1937)

- «Выборгская сторона» (1939)

- «Волочаевские дни» (1937)

- «Друзья» (1938)

- «Человек с ружьем» (1938)

- «Великий гражданин» (2 серии, 1938-39)

- «Глупый мышонок» (мультфильм, 1939)

- «Приключения Корзинкиной» (1941)

- «Зоя» (1944)

- «Простые люди» (1945)

- «Пирогов» (1947)

- «Молодая гвардия» (1948)

- «Мичурин» (1949)

- «Встреча на Эльбе» (1949)

- «Незабываемый 1919-й год» (1952)

- «Белинский» (1953)

- «Единство» (1954)

- «Овод» (1955)

- «Первый эшелон» (1956)

- «Гамлет» (1964)

- «Год, как жизнь» (1966)

- «Король Лир» (1971) и др.

Инструментовка сочинений других авторов

- М. П. Мусоргского — опер «Борис Годунов» (1940), «Хованщина» (1959), вокального цикла «Песни и пляски смерти» (1962)

- оперы «Скрипка Ротшильда» В. И. Флейшмана (1943)

- хоров А. А. Давиденко -«На десятой версте» и «Улица волнуется» (для хора с оркестра, 1962

Читайте также:

- Как полюбить классическую музыку и как не пропустить жизнь сквозь пальцы

- Мишель Петруччиани. Музыка вопреки

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

Shostakovich in 1950

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich[n 1] (25 September [O.S. 12 September] 1906 – 9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist[1] who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throughout his life as a major composer.

Shostakovich achieved early fame in the Soviet Union, but had a complex relationship with its government. His 1934 opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was initially a success, but eventually was condemned by the Soviet government, putting his career at risk. In 1948 his work was denounced under the Zhdanov Doctrine, with professional consequences lasting several years. Even after his censure was rescinded in 1956, performances of his music were occasionally subject to state interventions, as with his Thirteenth Symphony (1962). Shostakovich was a member of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR (1947) and the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union (from 1962 until his death), as well as chairman of the RSFSR Union of Composers (1960–1968). Over the course of his career, he earned several important awards, including the Order of Lenin, from the Soviet government.

Shostakovich combined a variety of different musical techniques in his works. His music is characterized by sharp contrasts, elements of the grotesque, and ambivalent tonality; he was also heavily influenced by neoclassicism and by the late Romanticism of Gustav Mahler. His orchestral works include 15 symphonies and six concerti (two each for piano, violin, and cello). His chamber works include 15 string quartets, a piano quintet, and two piano trios. His solo piano works include two sonatas, an early set of 24 preludes, and a later set of 24 preludes and fugues. Stage works include three completed operas and three ballets. Shostakovich also wrote several song cycles, and a substantial quantity of music for theatre and film.

Shostakovich’s reputation has continued to grow after his death. Scholarly interest has increased significantly since the late 20th century, including considerable debate about the relationship between his music and his attitudes to the Soviet government.

Biography[edit]

Youth[edit]

Birthplace of Shostakovich (now School No. 267). Commemorative plaque at left

Born at Podolskaya Street in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, Shostakovich was the second of three children of Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina. Shostakovich’s immediate forebears came from Siberia,[2] but his paternal grandfather, Bolesław Szostakowicz, was of Polish Roman Catholic descent, tracing his family roots to the region of the town of Vileyka in today’s Belarus. A Polish revolutionary in the January Uprising of 1863–64, Szostakowicz was exiled to Narym in 1866 in the crackdown that followed Dmitry Karakozov’s assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II.[3] When his term of exile ended, Szostakowicz decided to remain in Siberia. He eventually became a successful banker in Irkutsk and raised a large family. His son Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer’s father, was born in exile in Narym in 1875 and studied physics and mathematics at Saint Petersburg University, graduating in 1899. He then went to work as an engineer under Dmitri Mendeleev at the Bureau of Weights and Measures in Saint Petersburg. In 1903, he married another Siberian immigrant to the capital, Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina, one of six children born to a Siberian Russian.[3]

Their son, Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, displayed significant musical talent after he began piano lessons with his mother at the age of nine. On several occasions, he displayed a remarkable ability to remember what his mother had played at the previous lesson, and would get «caught in the act» of playing the previous lesson’s music while pretending to read different music placed in front of him.[4] In 1918, he wrote a funeral march in memory of two leaders of the Kadet party murdered by Bolshevik sailors.[5]

In 1919, at age 13,[6] Shostakovich was admitted to the Petrograd Conservatory, then headed by Alexander Glazunov, who monitored his progress closely and promoted him.[7] Shostakovich studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and Elena Rozanova, composition with Maximilian Steinberg, and counterpoint and fugue with Nikolay Sokolov, who became his friend.[8] He also attended Alexander Ossovsky’s music history classes.[9] In 1925, he enrolled in the conducting classes of Nikolai Malko,[10] where he conducted the conservatory orchestra in a private performance of Beethoven’s First Symphony. According to the recollections of the composer’s classmate, Valerian Bogdanov-Berezhovsky [ru]:

Shostakovich stood at the podium, played with his hair and jacket cuffs, looked around at the hushed teenagers with instruments at the ready and raised the baton. … He neither stopped the orchestra, nor made any remarks; he focused his entire attention on aspects of tempi and dynamics, which were very clearly displayed in his gestures. The contrasts between the «Adagio molto» of the introduction and «Allegro con brio» first theme were quite striking, as were those between the percussive accents of the chords (woodwinds, French horns, pizzicato strings) and the momentarily extended piano in the introduction following them. In the character given to the pattern of the first theme, I recall, there was both vigorous striving and lightness; in the bass part there was an emphasized pliancy of tenderly threaded articulation. … Moments of these sorts … were discoveries of an improvised order, born from an intuitively refined understanding of the character of a piece and the elements of musical imagery embedded in it. And the players enjoyed it.[11]

On 20 March 1925, Shostakovich’s music was played in Moscow for the first time, in a program which also included works by his friend Vissarion Shebalin. To the composer’s disappointment, the critics and public there received his music coolly. During his visit to Moscow, Mikhail Kvadri introduced him to Mikhail Tukhachevsky,[12] who helped the composer find accommodation and work there, and sent a driver to take him to a concert in «a very stylish automobile».[13]

Shostakovich’s musical breakthrough was the First Symphony, written as his graduation piece at the age of 19. Initially, Shostakovich aspired only to perform it privately with the conservatory orchestra and prepared to conduct the scherzo himself. By late 1925, Malko agreed to conduct its premiere with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra after Steinberg and Shostakovich’s friend Boleslav Yavorsky brought the symphony to his attention.[14] On 12 May 1926, Malko led the premiere of the symphony; the audience received it enthusiastically, demanding an encore of the scherzo. Thereafter, Shostakovich regularly celebrated the date of his symphonic debut.[15]

Early career[edit]

After graduation, Shostakovich embarked on a dual career as concert pianist and composer, but his dry keyboard style was often criticized.[16] Shostakovich maintained a heavy performance schedule until 1930; after 1933, he performed only his own compositions.[17] Along with Yuri Bryushkov [ru], Grigory Ginzburg, Lev Oborin, and Josif Shvarts, he was among the Soviet contestants in the inaugural I International Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1927. Bogdanov-Berezhovsky later remembered:

The self-discipline with which the young Shostakovich prepared for the 1927 [Chopin] Competition was astonishing. For three weeks, he locked himself away at home, practicing for hours at a time, having postponed his composing, and given up trips to the theatre and visits with friends. Even more startling was the result of this seclusion. Of course, prior to this time, he had played superbly and occasioned Glazunov’s now famous glowing reports. But during those days, his pianism, sharply idiosyncratic and rhythmically impulsive, multi-timbered yet graphically defined, emerged in its concentrated form.[18]

Natan Perelman [ru], who heard Shostakovich play his Chopin programs before he went to Warsaw, said that his «anti-sentimental» playing, which eschewed rubato and extreme dynamic contrasts, was unlike anything he had ever heard. Arnold Alschwang [ru] called Shostakovich’s playing «profound and lacking any salon-like mannerisms.»[19]

Shostakovich was stricken with appendicitis on the opening day of the competition, but his condition improved by the time of his first performance on 27 January 1927. (He had his appendix removed on 25 April.) According to Shostakovich, his playing found favor with the audience. He persisted into the final round of the competition but ultimately earned only a diploma, no prize; Oborin was declared the winner. Shostakovich was upset about the result but for a time resolved to continue a career as performer. While recovering from his appendectomy in April 1927, Shostakovich said he was beginning to reassess those plans:

When I was well, I practiced the piano every day. I wanted to carry on like that until autumn and then decide. If I saw that I had not improved, I would quit the whole business. To be a pianist who is worse than Szpinalski, Etkin, Ginzburg, and Bryushkov (it is commonly thought that I am worse than them) is not worth it.[20]

After the competition, Shostakovich and Oborin spent a week in Berlin. There he met the conductor Bruno Walter, who was so impressed by Shostakovich’s First Symphony that he conducted its first performance outside Russia later that year. Leopold Stokowski led the American premiere the next year in Philadelphia and also made the work’s first recording.[21][22]

In 1927, Shostakovich wrote his Second Symphony (subtitled To October), a patriotic piece with a pro-Soviet choral finale. Owing to its modernism, it did not meet with the same enthusiasm as his First.[23] This year also marked the beginning of Shostakovich’s close friendship with musicologist and theatre critic Ivan Sollertinsky, whom he had first met in 1921 through their mutual friends Lev Arnshtam and Lydia Zhukova.[24][25] Shostakovich later said that Sollertinsky «taught [him] to understand and love such great masters as Brahms, Mahler, and Bruckner» and that he instilled in him «an interest in music … from Bach to Offenbach.»[26]

While writing the Second Symphony, Shostakovich also began work on his satirical opera The Nose, based on the story by Nikolai Gogol. In June 1929, against the composer’s wishes, the opera was given a concert performance; it was ferociously attacked by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM).[27] Its stage premiere on 18 January 1930 opened to generally poor reviews and widespread incomprehension among musicians.[28] In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Shostakovich worked at TRAM, a proletarian youth theatre. Although he did little work in this post, it shielded him from ideological attack. Much of this period was spent writing his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which was first performed in 1934. It was initially immediately successful, on both popular and official levels. It was described as «the result of the general success of Socialist construction, of the correct policy of the Party», and as an opera that «could have been written only by a Soviet composer brought up in the best tradition of Soviet culture».[29]

Shostakovich married his first wife, Nina Varzar, in 1932. Difficulties led to a divorce in 1935, but the couple soon remarried when Nina became pregnant with their first child, Galina.[30]

First denunciation[edit]

On 17 January 1936, Joseph Stalin paid a rare visit to the opera for a performance of a new work, Quiet Flows the Don, based on the novel by Mikhail Sholokhov, by the little-known composer Ivan Dzerzhinsky, who was called to Stalin’s box at the end of the performance and told that his work had «considerable ideological-political value».[31] On 26 January, Stalin revisited the opera, accompanied by Vyacheslav Molotov, Andrei Zhdanov and Anastas Mikoyan, to hear Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. He and his entourage left without speaking to anyone. Shostakovich had been forewarned by a friend that he should postpone a planned concert tour in Arkhangelsk in order to be present at that particular performance.[32] Eyewitness accounts testify that Shostakovich was «white as a sheet» when he went to take his bow after the third act.[33]

The next day, Shostakovich left for Arkhangelsk, where he heard on 28 January that Pravda had published an editorial titled «Muddle Instead of Music», complaining that the opera was a «deliberately dissonant, muddled stream of sounds …[that] quacks, hoots, pants and gasps.»[34] Shostakovich continued his performance tour as scheduled, with no disruptions. From Arkhangelsk, he instructed Isaac Glikman to subscribe to a clipping service.[35] The editorial was the signal for a nationwide campaign, during which even Soviet music critics who had praised the opera were forced to recant in print, saying they «failed to detect the shortcomings of Lady Macbeth as pointed out by Pravda«.[36] There was resistance from those who admired Shostakovich, including Sollertinsky, who turned up at a composers’ meeting in Leningrad called to denounce the opera and praised it instead. Two other speakers supported him. When Shostakovich returned to Leningrad, he had a telephone call from the commander of the Leningrad Military District, who had been asked by Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky to make sure that he was all right. When the writer Isaac Babel was under arrest four years later, he told his interrogators that «it was common ground for us to proclaim the genius of the slighted Shostakovich.»[37]

On 6 February, Shostakovich was again attacked in Pravda, this time for his light comic ballet The Limpid Stream, which was denounced because «it jangles and expresses nothing» and did not give an accurate picture of peasant life on a collective farm.[38] Fearful that he was about to be arrested, Shostakovich secured an appointment with the Chairman of the USSR State Committee on Culture, Platon Kerzhentsev, who reported to Stalin and Molotov that he had instructed the composer to «reject formalist errors and in his art attain something that could be understood by the broad masses», and that Shostakovich had admitted being in the wrong and had asked for a meeting with Stalin, which was not granted.[39]

The Pravda campaign against Shostakovich caused his commissions and concert appearances, and performances of his music, to decline markedly. His monthly earnings dropped from an average of as much as 12,000 rubles to as little as 2,000.[40]

1936 marked the beginning of the Great Terror, in which many of Shostakovich’s friends and relatives were imprisoned or killed. These included Tukhachevsky, executed 12 June 1937; his brother-in-law Vsevolod Frederiks, who was eventually released but died before he returned home; his close friend Nikolai Zhilyayev, a musicologist who had taught Tukhachevsky; his mother-in-law, the astronomer Sofiya Mikhaylovna Varzar,[41] who was sent to a camp in Karaganda; his friend the Marxist writer Galina Serebryakova, who spent 20 years in the gulag; his uncle Maxim Kostrykin (died); and his colleagues Boris Kornilov and Adrian Piotrovsky (executed).[42]

Shostakovich’s daughter Galina was born during this period in 1936;[43] his son Maxim was born two years later.[44]

Withdrawal of the Fourth Symphony[edit]

The publication of the Pravda editorials coincided with the composition of Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony. The work continued a shift in his style, influenced by the music of Mahler, and gave him problems as he attempted to reform his style. Despite the Pravda articles, he continued to compose the symphony and planned a premiere at the end of 1936. Rehearsals began that December, but according to Isaac Glikman, who had attended the rehearsals with the composer, the manager of the Leningrad Philharmonic persuaded Shostakovich to withdraw the symphony.[45] Shostakovich did not repudiate the work and retained its designation as his Fourth Symphony. (A reduction for two pianos was performed and published in 1946,[46] and the work was finally premiered in 1961).[47]

In the months between the withdrawal of the Fourth Symphony and the completion of the Fifth on 20 July 1937, the only concert work Shostakovich composed was the Four Romances on Texts by Pushkin.[48]

Fifth Symphony and return to favor[edit]

The composer’s response to his denunciation was the Fifth Symphony of 1937, which was musically more conservative than his recent works. Premiered on 21 November 1937 in Leningrad, it was a phenomenal success. The Fifth brought many to tears and welling emotions.[49] Later, Shostakovich’s purported memoir, Testimony, stated: «I’ll never believe that a man who understood nothing could feel the Fifth Symphony. Of course they understood, they understood what was happening around them and they understood what the Fifth was about.»[50]

The success put Shostakovich in good standing once again. Music critics and the authorities alike, including those who had earlier accused him of formalism, claimed that he had learned from his mistakes and become a true Soviet artist. In a newspaper article published under Shostakovich’s name, the Fifth was characterized as «A Soviet artist’s creative response to just criticism.»[51] The composer Dmitry Kabalevsky, who had been among those who disassociated themselves from Shostakovich when the Pravda article was published, praised the Fifth and congratulated Shostakovich for «not having given in to the seductive temptations of his previous ‘erroneous’ ways.»[52]

It was also at this time that Shostakovich composed the first of his string quartets. In September 1937, he began to teach composition at the Leningrad Conservatory, which provided some financial security.[53]

Second World War[edit]

In 1939, before Soviet forces attempted to invade Finland, the Party Secretary of Leningrad Andrei Zhdanov commissioned a celebratory piece from Shostakovich, the Suite on Finnish Themes, to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army paraded through Helsinki. The Winter War was a bitter experience for the Red Army, the parade never happened, and Shostakovich never laid claim to the authorship of this work.[54] It was not performed until 2001.[55] After the outbreak of war between the Soviet Union and Germany in 1941, Shostakovich initially remained in Leningrad. He tried to enlist in the military but was turned away because of his poor eyesight. To compensate, he became a volunteer for the Leningrad Conservatory’s firefighter brigade and delivered a radio broadcast to the Soviet people. listen (help·info) The photograph for which he posed was published in newspapers throughout the country.[56]

Shostakovich’s most famous wartime contribution was the Seventh Symphony. The composer wrote the first three movements in Leningrad while it was under siege; he completed the work in Kuybyshev (now Samara), where he and his family had been evacuated.[57] According to a radio address he made on 17 September 1941, he continued work on the symphony in order to show his fellow citizens that everyone had a «soldier’s duty» to ensure life went on. In another article written on 8 October, he wrote that the Seventh was a «symphony about our age, our people, our sacred war, and our victory.»[58] Shostakovich finished his Seventh Symphony on 27 December.[59] The symphony was premiered by the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra in Kuibyshev on 29 March and soon performed in London and the United States.[60] It was subsequently performed in Leningrad while the city was still under siege. The city’s remaining orchestra only had 14 musicians left, which led conductor Karl Eliasberg to reinforce it by recruiting anyone who could play an instrument.[61]

The Shostakovich family moved to Moscow in spring 1943, by which time the Red Army was on the offensive. As a result, Soviet authorities and the international public were puzzled by the tragic tone of the Eighth Symphony, which in the Western press had briefly acquired the nickname «Stalingrad Symphony.» The symphony was received tepidly in the Soviet Union and the West. Olin Downes expressed his disappointment in the piece, but Carlos Chávez, who had conducted the symphony’s Mexican premiere, praised it highly.[62]

Shostakovich had expressed as early as 1943 his intention to cap his wartime trilogy of symphonies with a grandiose Ninth. On 16 January 1945, he announced to his students that he had begun work on its first movement the day before. In April, his friend Isaac Glikman heard an extensive portion of the first movement, noting that it was «majestic in scale, in pathos, in its breathtaking motion».[63] Shortly thereafter, Shostakovich ceased work on this version of the Ninth, which remained lost until musicologist Ol’ga Digonskaya rediscovered it in December 2003.[64] Shostakovich began to compose his actual, unrelated Ninth Symphony in late July 1945; he completed it on 30 August. It was shorter and lighter in texture than its predecessors. Gavriil Popov wrote that it was «splendid in its joie de vivre, gaiety, brilliance, and pungency!»[65] By 1946 it was the subject of official criticism. Israel Nestyev asked whether it was the right time for «a light and amusing interlude between Shostakovich’s significant creations, a temporary rejection of great, serious problems for the sake of playful, filigree-trimmed trifles.»[66] The New York World-Telegram of 27 July 1946 was similarly dismissive: «The Russian composer should not have expressed his feelings about the defeat of Nazism in such a childish manner». Shostakovich continued to compose chamber music, notably his Second Piano Trio, dedicated to the memory of Sollertinsky, with a Jewish-inspired finale.

In 1947, Shostakovich was made a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR.[67]

Second denunciation[edit]

In 1948, Shostakovich, along with many other composers, was again denounced for formalism in the Zhdanov decree. Andrei Zhdanov, Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, accused the composers (including Sergei Prokofiev and Aram Khachaturian) of writing inappropriate and formalist music. This was part of an ongoing anti-formalism campaign intended to root out all Western compositional influence as well as any perceived «non-Russian» output. The conference resulted in the publication of the Central Committee’s Decree «On V. Muradeli’s opera The Great Friendship«, which targeted all Soviet composers and demanded that they write only «proletarian» music, or music for the masses. The accused composers, including Shostakovich, were summoned to make public apologies in front of the committee.[68] Most of Shostakovich’s works were banned, and his family had privileges withdrawn. Yuri Lyubimov says that at this time «he waited for his arrest at night out on the landing by the lift, so that at least his family wouldn’t be disturbed.»[69]

The decree’s consequences for composers were harsh. Shostakovich was among those dismissed from the Conservatory altogether. For him, the loss of money was perhaps the heaviest blow. Others still in the Conservatory experienced an atmosphere thick with suspicion. No one wanted his work to be understood as formalist, so many resorted to accusing their colleagues of writing or performing anti-proletarian music.[70]

During the next few years, Shostakovich composed three categories of work: film music to pay the rent, official works aimed at securing official rehabilitation, and serious works «for the desk drawer». The last included the Violin Concerto No. 1 and the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. The cycle was written at a time when the postwar anti-Semitic campaign was already under way, with widespread arrests, including that of Dobrushin and Yiditsky, the compilers of the book from which Shostakovich took his texts.[71]

The restrictions on Shostakovich’s music and living arrangements were eased in 1949, when Stalin decided that the Soviets needed to send artistic representatives to the Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace in New York City, and that Shostakovich should be among them. For Shostakovich, it was a humiliating experience, culminating in a New York press conference where he was expected to read a prepared speech. Nicolas Nabokov, who was present in the audience, witnessed Shostakovich starting to read «in a nervous and shaky voice» before he had to break off «and the speech was continued in English by a suave radio baritone».[72] Fully aware that Shostakovich was not free to speak his mind, Nabokov publicly asked him whether he supported the then recent denunciation of Stravinsky’s music in the Soviet Union. A great admirer of Stravinsky who had been influenced by his music, Shostakovich had no alternative but to answer in the affirmative. Nabokov did not hesitate to write that this demonstrated that Shostakovich was «not a free man, but an obedient tool of his government.»[73] Shostakovich never forgave Nabokov for this public humiliation.[74] That same year, he was obliged to compose the cantata Song of the Forests, which praised Stalin as the «great gardener».[75]

Stalin’s death in 1953 was the biggest step toward Shostakovich’s rehabilitation as a creative artist, which was marked by his Tenth Symphony. It features a number of musical quotations and codes (notably the DSCH and Elmira motifs, Elmira Nazirova being a pianist and composer who had studied under Shostakovich in the year before his dismissal from the Moscow Conservatory),[76] the meaning of which is still debated, while the savage second movement, according to Testimony, is intended as a musical portrait of Stalin. The Tenth ranks alongside the Fifth and Seventh as one of Shostakovich’s most popular works. 1953 also saw a stream of premieres of the «desk drawer» works.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Shostakovich had close relationships with two of his pupils, Galina Ustvolskaya and Elmira Nazirova. In the background to all this remained Shostakovich’s first, open marriage to Nina Varzar until her death in 1954. He taught Ustvolskaya from 1939 to 1941 and then from 1947 to 1948. The nature of their relationship is far from clear: Mstislav Rostropovich described it as «tender». Ustvolskaya rejected a proposal of marriage from him after Nina’s death.[77] Shostakovich’s daughter, Galina, recalled her father consulting her and Maxim about the possibility of Ustvolskaya becoming their stepmother.[77][78] Ustvolskaya’s friend Viktor Suslin said that she had been «deeply disappointed by [Shostakovich’s] conspicuous silence» when her music faced criticism after her graduation from the Leningrad Conservatory.[79] The relationship with Nazirova seems to have been one-sided, expressed largely in his letters to her, and can be dated to around 1953 to 1956. He married his second wife, Komsomol activist Margarita Kainova, in 1956; the couple proved ill-matched, and divorced five years later.[80]

In 1954, Shostakovich wrote the Festive Overture, opus 96; it was used as the theme music for the 1980 Summer Olympics.[81] (His ‘»Theme from the film Pirogov, Opus 76a: Finale» was played as the cauldron was lit at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece.)[82][83]

In 1959, Shostakovich appeared on stage in Moscow at the end of a concert performance of his Fifth Symphony, congratulating Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for their performance (part of a concert tour of the Soviet Union). Later that year, Bernstein and the Philharmonic recorded the symphony in Boston for Columbia Records.[84][85]

Joining the Party[edit]

The year 1960 marked another turning point in Shostakovich’s life: he joined the Communist Party. The government wanted to appoint him Chairman of the RSFSR Union of Composers, but to hold that position he was required to obtain Party membership. It was understood that Nikita Khrushchev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party from 1953 to 1964, was looking for support from the intelligentsia’s leading ranks in an effort to create a better relationship with the Soviet Union’s artists.[86] This event has variously been interpreted as a show of commitment, a mark of cowardice, the result of political pressure, and his free decision. On the one hand, the apparat was less repressive than it had been before Stalin’s death. On the other, his son recalled that the event reduced Shostakovich to tears,[87] and that he later told his wife Irina that he had been blackmailed.[88] Lev Lebedinsky has said that the composer was suicidal.[89] In 1960, he was appointed Chairman of the RSFSR Union of Composers;[90][91] from 1962 until his death, he also served as a delegate in the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.[92] By joining the party, Shostakovich also committed himself to finally writing the homage to Lenin that he had promised before. His Twelfth Symphony, which portrays the Bolshevik Revolution and was completed in 1961, was dedicated to Lenin and called «The Year 1917».

Shostakovich’s musical response to these personal crises was the Eighth String Quartet, composed in only three days. He subtitled the piece «To the victims of fascism and war»,[93] ostensibly in memory of the Dresden fire bombing that took place in 1945. Yet like the Tenth Symphony, the quartet incorporates quotations from several of his past works and his musical monogram. Shostakovich confessed to his friend Isaac Glikman, «I started thinking that if some day I die, nobody is likely to write a work in memory of me, so I had better write one myself.»[94] Several of Shostakovich’s colleagues, including Natalya Vovsi-Mikhoels[95] and the cellist Valentin Berlinsky,[96] were also aware of the Eighth Quartet’s biographical intent. Peter J. Rabinowitz has also pointed to covert references to Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen in it.[97]

In 1962, Shostakovich married for the third time, to Irina Supinskaya. In a letter to Glikman, he wrote, «her only defect is that she is 27 years old. In all other respects she is splendid: clever, cheerful, straightforward and very likeable.»[98] According to Galina Vishnevskaya, who knew the Shostakoviches well, this marriage was a very happy one: «It was with her that Dmitri Dmitriyevich finally came to know domestic peace… Surely, she prolonged his life by several years.»[99] In November, he conducted publicly for the only time in his life, leading a couple of his own works in Gorky;[100] otherwise he declined to conduct, citing nerves and ill health.[citation needed]

That year saw Shostakovich again turn to the subject of anti-Semitism in his Thirteenth Symphony (subtitled Babi Yar). The symphony sets a number of poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, the first of which commemorates a massacre of Ukrainian Jews during the Second World War. Opinions are divided as to how great a risk this was: the poem had been published in Soviet media and was not banned, but it remained controversial. After the symphony’s premiere, Yevtushenko was forced to add a stanza to his poem that said that Russians and Ukrainians had died alongside the Jews at Babi Yar.[101]

In 1965, Shostakovich raised his voice in defence of poet Joseph Brodsky, who was sentenced to five years of exile and hard labor. Shostakovich co-signed protests with Yevtushenko, fellow Soviet artists Kornei Chukovsky, Anna Akhmatova, Samuil Marshak, and the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. After the protests, the sentence was commuted, and Brodsky returned to Leningrad.[102]

Later life[edit]

In 1964, Shostakovich composed the music for the Russian film Hamlet, which was favorably reviewed by The New York Times: «But the lack of this aural stimulation—of Shakespeare’s eloquent words—is recompensed in some measure by a splendid and stirring musical score by Dmitri Shostakovich. This has great dignity and depth, and at times an appropriate wildness or becoming levity».[103]

In later life, Shostakovich suffered from chronic ill health, but he resisted giving up cigarettes and vodka. Beginning in 1958, he suffered from a debilitating condition that particularly affected his right hand, eventually forcing him to give up piano playing; in 1965, it was diagnosed as poliomyelitis. He also suffered heart attacks in 1966 and 1971, as well as several falls in which he broke both his legs; in 1967, he wrote in a letter: «Target achieved so far: 75% (right leg broken, left leg broken, right hand defective). All I need to do now is wreck the left hand and then 100% of my extremities will be out of order.»[104]

A preoccupation with his own mortality permeates Shostakovich’s later works, such as the later quartets and the Fourteenth Symphony of 1969 (a song cycle based on a number of poems on the theme of death). This piece also finds Shostakovich at his most extreme with musical language, with 12-tone themes and dense polyphony throughout. He dedicated the Fourteenth to his close friend Benjamin Britten, who conducted its Western premiere at the 1970 Aldeburgh Festival. The Fifteenth Symphony of 1971 is, by contrast, melodic and retrospective in nature, quoting Wagner, Rossini and the composer’s own Fourth Symphony.[105]

Death[edit]

Shostakovich voting in the election of the Council of Administration of Soviet Musicians in Moscow in 1974 (photograph by Yuri Shcherbinin

Shostakovich died of heart failure on 9 August 1975 at the Central Clinical Hospital in Moscow. A civic funeral was held; he was interred in Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow. «He was known to have suffered from heart ailments that dated to his hospitalization for a heart attack in 1964».[106] Even before his death, he had been recognized with the naming of the Shostakovich Peninsula on Alexander Island, Antarctica.[107] Despite suffering from motor neurone disease (or ALS) from as early as the 1960s, Shostakovich insisted upon writing all his own correspondence and music himself, even when his right hand was virtually unusable.

Shostakovich himself left behind several recordings of his own piano works; other noted interpreters of his music include Mstislav Rostropovich,[108] Tatiana Nikolayeva,[109] Maria Yudina[citation needed], David Oistrakh,[110] and members of the Beethoven Quartet.[111][112]

His last work was his Viola Sonata, which was first performed officially on 1 October 1975.[113][page needed]

Shostakovich’s musical influence on later composers outside the former Soviet Union has been relatively slight, although Alfred Schnittke took up his eclecticism and his contrasts between the dynamic and the static, and some of André Previn’s music shows clear links to Shostakovich’s style of orchestration. His influence can also be seen in some Nordic composers, such as Lars-Erik Larsson.[114] Many of his Russian contemporaries, and his pupils at the Leningrad Conservatory were strongly influenced by his style (including German Okunev, Sergei Slonimsky, and Boris Tishchenko, whose Fifth Symphony of 1978 is dedicated to Shostakovich’s memory). Shostakovich’s conservative idiom has grown increasingly popular with audiences both within and outside Russia, as the avant-garde has declined in influence and debate about his political views has developed.[citation needed]

Music[edit]

Overview[edit]

Shostakovich’s works are broadly tonal[citation needed] but with elements of atonality and chromaticism. In some of his later works (e.g., the Twelfth Quartet), he made use of tone rows. His output is dominated by his cycles of symphonies and string quartets, each totaling 15. The symphonies are distributed fairly evenly throughout his career, while the quartets are concentrated towards the latter part. Among the most popular are the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies and the Eighth and Fifteenth Quartets. Other works include the operas Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, The Nose and the unfinished The Gamblers, based on the comedy by Gogol; six concertos (two each for piano, violin and cello); two piano trios; and a large quantity of film music.[citation needed]

Shostakovich’s music shows the influence of many of the composers he most admired: Bach in his fugues and passacaglias; Beethoven in the late quartets; Mahler in the symphonies; and Berg in his use of musical codes and quotations. Among Russian composers, he particularly admired Modest Mussorgsky, whose operas Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina he reorchestrated; Mussorgsky’s influence is most prominent in the wintry scenes of Lady Macbeth and the Eleventh Symphony, as well as in satirical works such as «Rayok».[115] Prokofiev’s influence is most apparent in the earlier piano works, such as the first sonata and first concerto.[116] The influence of Russian church and folk music is evident in his works for unaccompanied choir of the 1950s.[117]

Shostakovich’s relationship with Stravinsky was profoundly ambivalent; as he wrote to Glikman, «Stravinsky the composer I worship. Stravinsky the thinker I despise.»[118] He was particularly enamoured of the Symphony of Psalms, presenting a copy of his own piano version of it to Stravinsky when the latter visited the USSR in 1962. (The meeting of the two composers was not very successful; observers commented on Shostakovich’s extreme nervousness and Stravinsky’s «cruelty» to him.)[119]

Many commentators have noted the disjunction between the experimental works before the 1936 denunciation and the more conservative ones that followed; the composer told Flora Litvinova, «without ‘Party guidance’ … I would have displayed more brilliance, used more sarcasm, I could have revealed my ideas openly instead of having to resort to camouflage.»[120] Articles Shostakovich published in 1934 and 1935 cited Berg, Schoenberg, Krenek, Hindemith, «and especially Stravinsky» among his influences.[121] Key works of the earlier period are the First Symphony, which combined the academicism of the conservatory with his progressive inclinations; The Nose («The most uncompromisingly modernist of all his stage-works»[122]); Lady Macbeth, which precipitated the denunciation; and the Fourth Symphony, described in Grove’s Dictionary as «a colossal synthesis of Shostakovich’s musical development to date».[123] The Fourth was also the first piece in which Mahler’s influence came to the fore, prefiguring the route Shostakovich took to secure his rehabilitation, while he himself admitted that the preceding two were his least successful.[124]

After 1936, Shostakovich’s music became more conservative. During this time he also composed more chamber music.[125] While his chamber works were largely tonal, the late chamber works, which Grove’s Dictionary calls a «world of purgatorial numbness»,[126] included tone rows, although he treated these thematically rather than serially. Vocal works are also a prominent feature of his late output.[127]

Jewish themes[edit]

In the 1940s, Shostakovich began to show an interest in Jewish themes. He was intrigued by Jewish music’s «ability to build a jolly melody on sad intonations».[128] Examples of works that included Jewish themes are the Fourth String Quartet (1949), the First Violin Concerto (1948), and the Four Monologues on Pushkin Poems (1952), as well as the Piano Trio in E minor (1944). He was further inspired to write with Jewish themes when he examined Moisei Beregovski’s 1944 thesis on Jewish folk music.[129]

In 1948, Shostakovich acquired a book of Jewish folk songs, from which he composed the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. He initially wrote eight songs meant to represent the hardships of being Jewish in the Soviet Union. To disguise this, he added three more meant to demonstrate the great life Jews had under the Soviet regime. Despite his efforts to hide the real meaning in the work, the Union of Composers refused to approve his music in 1949 under the pressure of the anti-Semitism that gripped the country. From Jewish Folk Poetry could not be performed until after Stalin’s death in March 1953, along with all the other works that were forbidden.[130]

Self-quotations[edit]

Throughout his compositions, Shostakovich demonstrated a controlled use of musical quotation. This stylistic choice had been common among earlier composers, but Shostakovich developed it into a defining characteristic of his music. Rather than quoting other composers, Shostakovich preferred to quote himself. Musicologists such as Sofia Moshevich, Ian McDonald, and Stephen Harris have connected his works through their quotations.[clarification needed][131]