- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- On This Day in History

- Quizzes

- Podcasts

- Dictionary

- Biographies

- Summaries

- Top Questions

- Week In Review

- Infographics

- Demystified

- Lists

- #WTFact

- Companions

- Image Galleries

- Spotlight

- The Forum

- One Good Fact

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Geography & Travel

- Health & Medicine

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Literature

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- Science

- Sports & Recreation

- Technology

- Visual Arts

- World History

- Britannica Classics

Check out these retro videos from Encyclopedia Britannica’s archives. - Demystified Videos

In Demystified, Britannica has all the answers to your burning questions. - #WTFact Videos

In #WTFact Britannica shares some of the most bizarre facts we can find. - This Time in History

In these videos, find out what happened this month (or any month!) in history. - Britannica Explains

In these videos, Britannica explains a variety of topics and answers frequently asked questions.

- Student Portal

Britannica is the ultimate student resource for key school subjects like history, government, literature, and more. - COVID-19 Portal

While this global health crisis continues to evolve, it can be useful to look to past pandemics to better understand how to respond today. - 100 Women

Britannica celebrates the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, highlighting suffragists and history-making politicians. - Britannica Beyond

We’ve created a new place where questions are at the center of learning. Go ahead. Ask. We won’t mind. - Saving Earth

Britannica Presents Earth’s To-Do List for the 21st Century. Learn about the major environmental problems facing our planet and what can be done about them! - SpaceNext50

Britannica presents SpaceNext50, From the race to the Moon to space stewardship, we explore a wide range of subjects that feed our curiosity about space!

A domovoi, which can be spelled domovoj or domovoy, is a house spirit in pre-Christian Slavic mythology, a being who lives in the hearth or behind the stove of a Slavic home and protects the inhabitants from harm. Attested from the sixth century CE, the domovoi sometimes appears as an old man or woman, and sometimes as a pig, bird, calf, or cat.

Key Takeaways: Domovoi

- Alternate Names: Pechnik, zapechnik, khozyain, iskrzychi, tsmok, vazila

- Equivalent: Hob (England), brownie (England and Scotland), kobold, goblin, or hobgoblin (Germany), tomte (Sweden), tonttu (Finland), nisse or tunkall (Norway).

- Epithets: Old Man of the House

- Culture/Country: Slavic mythology

- Realms and Powers: Protecting the house, outbuildings, and occupants and animals residing there

- Family: Some domovoi have wives and children—the daughters are hauntingly beautiful but fatally dangerous to humans.

Domovoi in Slavic Mythology

In Slavic mythology, all peasant houses have a domovoi, who is the soul of one (or all) of the deceased members of the family, making the domovoi part of ancestor worship traditions. The domovoi lives in the hearth or behind the stove and householders took care to not disturb the smoldering remains of a fire to keep their ancestors from falling through the grate.

When a family built a new house, the eldest would enter first, because the first to enter a new house was soon to die and become the domovoi. When the family moved from one house to another, they would rake out the fire and put the ashes into a jar and bring it with them, saying «Welcome, grandfather, to the new!» But if a house was abandoned, even if it was burned to the ground, the domovoi remained behind, to reject or accept the next occupants.

To prevent the immediate death of the oldest member of the family, families could sacrifice a goat, fowl, or lamb and bury it under the first stone or log set, and go without a domovoi. When the oldest member of the family eventually died, he became the domovoi for the house.

If there are no men in the house, or the head of the house is a woman, the domovoi is represented as a woman.

Appearance and Reputation

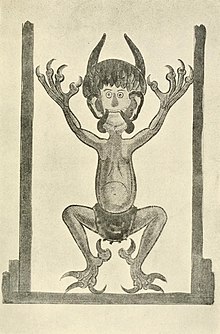

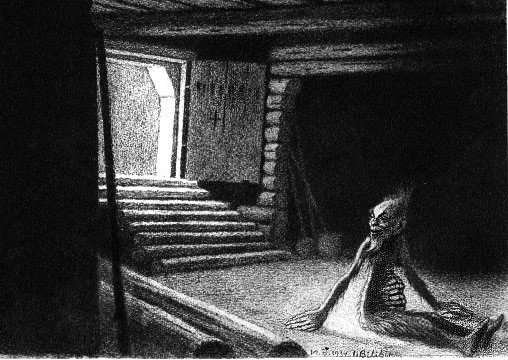

The peasant and the domovoi, 1922. Artist Chekhonin, Sergei Vasilievich (1878-1936).

Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images

In his most common appearance, the domovoi was a little old man the size of a 5-year-old (or under one foot tall) who is covered with hair—even the palms of his hands and the soles of his feet are covered with thick hair. On his face, only the space around his eyes and nose is bare. Other versions describe the domovoi with a wrinkled face, yellowish-gray hair, white beard, and glowing eyes. He wears a red shirt with a blue belt or a blue caftan with a rose-colored belt. Another version has him appearing as a beautiful boy dressed completely in white.

The domovoi is given to grumbling and quarreling, and he only comes out at night when the house is asleep. At night he visits the sleepers and glides his hairy hands across their faces. If the hands feel warm and soft, that is a sign of good luck; when they are cold and bristly, misfortune is on its way.

Role in Mythology

The main function of the domovoi is to protect the family of the household, to warn them when bad things are going to happen, to fend off forest spirits from playing pranks on the family and witches from stealing the cows. Industrious and frugal, the domovoi goes out at night and rides the horses, or lights a candle and roams the barnyard. When the head of the family dies, he may be heard wailing at night.

Before a war, pestilence, or fire breaks out, the domovoi leave their houses and assemble in the meadows to lament. If misfortune to the family is pending, the domovoi warns them by making knocking sounds, riding the horses at night until they are exhausted, or making the watch dogs dig holes in the courtyard or go howling through the village.

But the domovoi is easily offended and must be given gifts—small cloaks buried beneath the floor of the house to give them something to wear, or leftovers from dinner. On March 30th of each year, the domovoi turns malicious from dawn until midnight, and he must be bribed with food, such as little cakes or a pot of stewed grain.

Variations on a Domovoi

In some Slavic households, different versions of house spirits are found throughout the farmsteads. When a house spirit lives in a bathhouse he is called a bannik and people avoid taking baths at night because the bannik might suffocate them, especially if they haven’t prayed first. A Russian domovoi who lives in the yard is a domovoj-laska (weasel domovoi) or dvororoy (yard-dweller). In a barn they are ovinnik (barn-dweller) and in the barnyard, they are gumennik (barnyard dweller).

When a house spirit protects an animal barn he is called a vazila (for horses) or bagan (for goats or cows), and he takes on physical aspects of the animals and stays in a crib during the night.

Sources

- Ansimova, O.K., and O.V. Golubkova. «Mythological Characters of the Domestic Space in Russian Folk Beliefs: Lexicographic and Ethnographic Aspects.» Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 44 (2016): 130–38. Print.

- Kalik, Judith, and Alexander Uchitel. «Slavic Gods and Heroes.» London: Routledge, 2019. Print.

- Ralston, W.R.S. «The Songs of the Russian People, as Illustrative of Slavonic Mythology and Russian Social Life.» London: Ellis & Green, 1872. Print.

- Troshkova, Anna O., et al. «Folklorism of the Contemporary Youth’s Creative Work.» Space and Culture, India 6 (2018). Print.

- Zashikhina, Inga, and Natalia Drannikova. «Northern Russian and Norwegian Mythological Household Spirits of Inhabited Space Typology.» Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research 360 (2019): 273–77. Print.

3

Помогите пожалуйста!

Нужно на английском (с переводом) написать о мифические пнрсонаже ,в моем случае домовой. 5-7 предложений, типа:как выглядит, что делает, где живет и т. п

Только можно полегче, пожалуйста, а то учить это надо :'(

Спасибо большое заранее

1 ответ:

0

0

Домовой обычно живет в тех домах, где есть дети. похоже, этот большой волосатый чудик, который может напугать, но когда ты близко — вы увидите, что он симпатичный. он любит не только детей, но и домашних животных. когда вы выходите, домовой играет с животными. он любит жить в питомнике. там он чистит и играет.

brownie usually live in those homes where there are children. looks like this big hairy cat, which can scare, but when you close — you’ll see that he’s cute. he loves not only children but also Pets. when you leave, the house plays with the animals. he loves to live in the nursery. there, he cleans and plays.

Читайте также

1.How about ice-creame?

2.Would yoy like to eat soup?- With pleasure

My brother wants to join a spots club

Exaggerates; to catch; didn’t feel; himself; was passing; had heard; would not lie.

1. c

2. b

3. c

4. b

5. a

6. b

7. c

8. d

9. c

10. a

11. a

12. c

13. c

14. c

15. b

1) Why are they this color<span>?

</span>2) What’s the color of this toy<span>?

3) </span>Why do they have painted in this color<span>?</span>

In the Slavic religious tradition, Domovoy (Russian: Домово́й, literally «[ one] of the household»; also spelled Domovoi, Domovoj, and known as Polish: Domowik or Serbian and Ukrainian: Домовик, romanized: domovyk) is the household spirit of a given kin. They are deified progenitors, that is, the kin’s fountainhead ancestors.[2] According to the Russian folklorist E. G. Kagarov, the Domovoy is a personification of the supreme Rod in the microcosm of kinship.[3] Sometimes he has a female counterpart, Domania, the goddess of the household,[4] though he is most often a single god.[5] The Domovoy expresses himself as several other spirits of the household in its different functions.[6]

Etymology and belief[edit]

The term Domovoy comes from the Indo-European root * dom,[4] which is shared by many words in the semantic field of «abode», «domain» in the Indo-European languages (cf. Latin domus, «house»). The Domovoy have been compared to the Roman Di Penates, the genii of the family.[7] Helmold (c. 1120–1177), in his Chronica Slavorum, alluded to the widespread worship of penates among the Elbe Slavs. In the Chronica Boemorum of Cosmas of Prague (c. 1045–1125) it is written that Czech, one of the three mythical forefathers of the Slavs, brought the statues of the penates on his shoulders to the new country, and, resting on the mountain of the Rzip, said to his fellows:[2]

Rise, good friends, and make an offering to your penates, for it is their help that has brought you to this new country destined for you by Fate ages ago.

The Domovoy are believed to protect the well-being of kin in any of its aspects.[5] They are very protective towards the children and the animals of the house, constantly looking after them.[8] These gods are often represented as fighting with one another, to protect and make grow the welfare of their kin. In such warfare, the Domovoy of the eventual winner family is believed to take possession of the household of the vanquished rivals.[9]

They are believed to share the joys and the sorrows of the family, and to be able to forebode and warn about future events, such as the imminent death of a kindred person, plagues, wars or other calamities which threaten the welfare of the kin. The Domovoy become angry and reveal their demonic aspect if the family is corrupted by bad behaviour and language. In this case, the god may even quit and leave the kin unprotected against illness and calamity.[9]

Also, the tradition of Russian people «Sitting on the lane» which means spending a few minutes in silence sitting down before a long journey is connected with the Domovoy. According to the legend, Domovoy does not like to be alone. Otherwise, he can hide or take things from the owners of the house. Thus, the owners are trying to deceive Domovoy, pretending they will not leave their place of residence for a long time.[10]

Iconography and worship[edit]

Silesian statuettes of Domovoy, photographed in the early 20th century.[11]

The Domovoy is usually represented as an old, grey-haired man with flashing eyes. He may manifest in the form of animals, such as cats, dogs or bears, but also as the master of the house or a departed ancestor of the given family,[12] sometimes provided with a tail and little horns.[13] In some traditions the Domovoy are symbolised as snakes.[14] Household gods were represented by the Slavs as statuettes, made of clay or stone, which were placed in niches near the house’s door, and later on the mantelpieces above the ovens. They were attired in the distinct costume of the tribe to which the kin belonged.[7]

Sacrifices in honour of Domovoy are practised to make him participate in the life of the kin, and to appease and reconcile him in the case of anger. These include the offering of what is left of the evening meal, or, in cases of great anger, the sacrifice of a cock at midnight and the sprinkling of the nooks and corners of the common hall or the courtyard with the animal’s blood. Otherwise, a slice of bread strewn with salt and wrapped in a white cloth is offered in the hall or the courtyard while the members of the kin bow towards the four directions reciting prayers to the Domovoy.[9]

The Domovoy is believed to be somehow connected with the house building itself, so sacrifices are also practised when a family moved to a newly built house to invite the god to inhabit it. In this case, a hen and the first slice of bread cut for the first dinner in the new house are offered to the god and buried in the courtyard, reciting the formula:[15]

Our supporter, come into the new house to eat bread and obey your new master.

Similar rituals are practised to invite a Domovoy to transfer from one house to another, and to welcome him. [15]

Other household deities[edit]

Other household gods, or expressions of the Domovoy, are:

- Dvorovoy – tutelary deity of the courtyard[4]

- Bannik – «Bath Spirit», the tutelary deity of the private or public bathhouses,[note 1] who corresponds to the Komi Pyvsiansa[4]

- Ovinnik (Belarusian: Joŭnik) – «Threshing Barn Spirit»[17]

- Prigirstitis – known for his fine hearing[4]

- Krimba – household goddess among the Bohemians[4]

- The lizard-shaped Giwoitis[4]

Alternative naming[edit]

Some English-speaking authors interpret the name domovoy as «house elf».

[18][19]

The Slavic languages and their local forms have variations of the term Domovoy and alternative names to describe the household god, including:

- Děd, Dĕdek, Děduška[2] (names of this form convey the concept of «grandfather», Czech)

- Did, Didko, Diduch, Domovyk (Ukrainian)[7]

- David (Belarusian)

- Dedek, Djadek[7]

- Šetek, Šotek (Czech)[7]

- Skřítek (Czech)[7]

- Škrata, Škriatok (Slovak)[20]

- Škrat, Škratek (Slovenian)[20]

- Skrzatek, Skrzat, Skrzot (Polish)[20]

- Chozyain, Chozyainuško (Russian)[14] (meaning literally «master» and «little master»)

- Stopan (Bulgarian)[14]

- Domovníček, Hospodáříček (Czech)

- Domaći (Croatian)[14]

- Zmek, Smok, Ćmok (snake form)[8]

The female counterpart Romania can appear as:

- Domovikha (Russian: домовиха)[4]

- Damavukha (Belarusian: дамавуха)

- Kikimora[4]

- Marukha[4]

- Volossatka[4]

Domovoy may also have a proper name:

- Zhiharko (Russian: Жихарько), used in northern governorates of Russia[21]

- Adamiy (Russian: Адамий), used in Russian zagovory[22]

- Dedushko Domovedushko (Russian: Дедушко-Домоведушко)[22]

- Romanushko (Russian: Романушко; diminutive of the name Roman)[22]

- Otamanushko (Russian: Отаманушко)[22]

In savoury, his wife may have a proper name as well:

- Adamushka (Russian: Адамушка)[22]

- Domanushka (Russian: Доманушка; derived from the name Domna and from the noun дом)[22]

- Serafimushka (Russian: Серафимушка)[22]

Gallery of household deities[edit]

-

Sculpture of Ovinnik («Threshing Barn Spirit»), by Belarusian sculptor Anton Shipitsa based on illustrations by Valery Slauk

-

See also[edit]

- Ancestor worship

- Hob (folklore) Anglo-Scots household spirit

- Deities of Slavic religion

- Household deity

- Huldufolk

- Slavic paganism

- Slavic Native Faith

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Slavic bathhouses (banya) – which are like saunas, with an inner steaming room and an outer changing room – have their tutelary god, Bannik. A Slavic bathhouse is a place where traditionally women gave birth and practised divination, thus a receptacle of vital forces. The third or fourth firing is dedicated to Bannik, who is invited to the bathhouse with his forest spirits. In the bathhouse, Bannik is traditionally consulted as he is considered able to forebode the future.[16]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ MeisterDrucke. «Domovoi, 1934 by Ivan Yakovlevich Bilibin (#778598)». MeisterDrucke. Retrieved 2022-07-21.

- ^ a b c Máchal 1918, p. 240.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mathieu-Colas 2017.

- ^ a b Máchal 1918, p. 241.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f Máchal 1918, p. 244.

- ^ a b Máchal 1918, p. 247.

- ^ a b c Máchal 1918, p. 242.

- ^ «Russian culture of customs and superstitions». Ruslingua School. 2021-08-05. Retrieved 2022-06-17.

- ^ a b Máchal 1918, pp. 244 ff.

- ^ Máchal 1918, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, pp. 49–54.

- ^ a b c d Máchal 1918, p. 246.

- ^ a b Máchal 1918, p. 243.

- ^ Alexinsky, G. (1973). «Slavonic Mythology». New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Prometheus Press. pp. 287–288.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, p. 58.

- ^

Jones, William (1898). Credulities Past and Present: Including the Sea and Seamen, Miners, Amulets and Talismans, Rings, Word and Letter Divination, Numbers, Trials, Exorcising and Blessing of Animals, Birds, Eggs, and Luck. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 472. Retrieved 2019-06-02.One way of pacifying an irritated ‘domovoy,’ or house elf, among the Russians […].

- ^

Arrowsmith, Nancy (2009) [1977]. «Dusky elves». Field Guide to the Little People: A Curious Journey Into the Hidden Realm of Elves, Faeries, Hobgoblins & Other Not-so-mythical Creatures. Woodbury, Minnesota: Llewellyn Worldwide. p. 69. ISBN 9780738715490. Retrieved 2019-06-02.The Domoviye are among the most important Slavic house elves, although their name is sometimes used for other species. […] The Domoviye (singular Domovoy) do favours for the family, stealing food and grain from the neighbours, cleaning the house, and taking care of the animals.

- ^ a b c Máchal 1918, p. 245.

- ^ «Жихарько». Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary: In 86 Volumes (82 Volumes and 4 Additional Volumes). St. Petersburg. 1890–1907.

- ^ a b c d e f g «АДАМИЙ ДЕДУШКА, БАБУШКА АДАМУШКА» [Adamiy the Grandfather, Adamushka the Grandmother].

General and cited sources[edit]

- Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765630889.

- Máchal, Jan (1918). «Slavic Mythology». In L. H. Gray (ed.). The Mythology of all Races. Vol. III, Celtic and Slavic Mythology. Boston. pp. 217–389.

- Mathieu-Colas, Michel (2017). «Dieux slaves et baltes» (PDF). Dictionnaire des noms des divinités. France: Archive ouverte des Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société, Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

External links[edit]

Media related to Domovoy at Wikimedia Commons