Эхнатон – египетский фараон и основоположник монотеизма. Его жизнь до сих пор покрыта тайнами, а ученые продолжают строить догадки и предположения. Эхнатон правил недолго, он прожил всего 39 лет (1375 – 1336 г. до н.э.), но даже за это время он внес большие перемены в жизнь всего Египта. Его деятельность можно кратко обозначить, как сосредоточение власти только в руках фараона.

Эхнатон при рождении получил имя Аменхотеп IV. Его отцом был фараон Аменхотеп III, он взял в жены дочь жреца Тию. Считается, что она является потомком Яхмоса I, с которого и началась династия Тутмосидов. У Эхнатона было немало родственников: 4 сестры и старший брат Тутмос. О молодости Эхнатона известно совсем мало, он проживал в отдельном дворце, возможно даже за пределами Египта. Несколько лет он правил вместе с отцом, на тот момент Аменхотеп III уже тяжело болел.

Начало своего царствования он начал с масштабного строительства. Он возвел храмовые комплексы в Гемпаатоне и Хутбенбене. Позже между Фивами и Мемфисом был построен целый город – Ахет-Атон. Это была новая столица Египта. Название расшифровывается, как «Горизонт Атона».

Фараон меняет свое имя на Эхнатон, что означает «Угодный Атону». Начинаются большие перемены в религиозной сфере. По приказу фараона единым богом провозгласили Атона. Поклоняться ему могли только сам Эхнатон и его жена Нефертити. Остальные поданные должны были молиться им. Появилась новая должность – верховный жрец, им стал сам фараон. Остальные жрецы уже не имели такой силы как раньше. Таким образом, Эхнатон сосредоточил в своих руках власть во всех сферах жизни. Другие божества были запрещены. Противники этих перемен жестоко наказывались. Некоторые были сожжены, что считалось самой страшной смертью. Ведь тогда человек не сможет попасть в загробную жизнь.

По приказу фараона строились новые храмы для Атона. Они отличались богатейшими хозяйствами, и распоряжаться ими мог только Эхнатон. Для своего окружения он стал выбирать людей из низших сословий. Их социальное происхождение обозначалось словом «немху», что означало «сирота». Примерно в середине своего правления фараон стал уничтожать все упоминания о предыдущем боге Амоне. А само слово «бог» было заменено на «правитель». По какой причине Эхнатон решился на такую реформу не ясно.

Личная жизнь фараона так же полна тайн. Одни ученые предполагают, что его жена Нефертити приходится ему сводной сестрой по мужской линии. Другие считают, что его сын Тутанхамон также был рожден от одной из его сестер. Это могла быть либо Бакетатон, либо Небеттах.

В количестве детей ученые также не пришли к единому мнению. Нефертити родила Эхнатону 6 дочерей. Вторая жена Кийа, также родила дочь. Многие исследователи не считают Тутанхамона сыном Эхнатона, он может быть ему племянником или даже внуком.

Самая известная жена Эхнатона — Нефертити. Она имела большое влияние на мужа и всегда поддерживала его идеи. На всех изображениях она предстает в синем парике и в царском головном уборе. Интересен тот факт, что нет ни одного изображения Нифертити вместе с другой женой Эхнатона Кийей. А после смерти Нефертити ее дочери массово уничтожали изображения Кийи. В сохранившихся же портретах она практически везде одна.

Во внешней политике Эхнатон так же не пошел по пути отца. Он перестал отправлять дары союзникам. Так в 1360 г. до н.э. началась война с Митанией, в которой были потеряны все земли в Сирии.

Смерть Эхнатона также вызывает споры. Предположительно он был отравлен противниками его религиозной реформы. Как и положено фараону еще при жизни была построена его гробница в Амарне. Но после того как столицу перенесли обратно в Фивы, Эхнатона перезахоронили в Долине Царей.

Реформа Эхнатона просуществовала недолго, после его смерти всего через два года были восстановлены культы старых богов.

Биография

Фараон Эхнатон считается знаковой фигурой в истории Древнего Египта. Он не только муж самой Нефертити, называемой воплощением красоты на Земле, но и революционер своего времени, вознамерившийся заменить пантеон одним-единственным Атоном. За время правления Эхнатона Древний Египет не развязал ни одной войны, а в искусстве наступил расцвет натурализма.

Детство и юность

В жилах фараона, названного при рождении Аменхотеп IV, течет поистине голубая кровь. Отец Аменхотеп III происходил из великой династии Тутмосидов, из которой вышли все правители по имени Тутмос и третья женщина-фараон Хатшепсут. Мать Тия, хотя и была дочерью жреца, но считалась потомком царицы Яхмос-Нефертари, жены Яхмоса I, который и основал род Тутмосидов.

У Эхнатона был старший брат Тутмос, умерший маленьким, и сестры Небеттах, Сатамон, Хенуттанеб и Исиду. О наличии прочих близких родственников говорят многочисленные веpсии.

Сведений о первых годах биографии фараона сохранилось немного, да и те слишком обобщенные. Известно, что царский сын жил во дворце, небольшом по размеру, но богато украшенном мозаикой и росписью. Однако находился дворец не в Фивах, а возможно, и вовсе за пределами Египта. Упоминается, что жизнь юного Эхнатона подвергалась опасности, и некую неоценимую помощь в этой ситуации оказал слуга Пареннефер, которого фараон впоследствии возвысил.

Правление

Когда точно десятый фараон 18 династии взошел на престол Египта, неизвестно. Предполагается, что пару лет Аменхотеп IV правил вместе с отцом, который к тому времени уже тяжело болел. В наследство Эхнатон получил богатое и могущественное государство. В первые годы развернул обширное строительство, одними из объектов стали храмовые комплексы в Гемпаатоне и Хутбенбене.

Эхнатон, помимо верховенства культа Солнечного бога, ввел новую должность, верховного жреца бога Атона, и без ложной скромности первым занял её. Ритуалы велено справлять не в потаенном святилище, а на открытом воздухе. Причем поклоняться Атону имели право только Эхнатон и его жена Нефертити, а, следовательно, остальные должны были поклоняться им.

Культ Ра, на протяжении веков сопровождавший египтян, был запрещен, тем самым оказались лишены власти жрецы. Особенно невзлюбил фараон богов Амона, Мут и Хонсу, трех самых почитаемых в Фивах небожителей. В пылу сражений за монотеизм Эхнатон не побоялся стереть имя отца, которое переводилось как «Амон доволен».

В знак начала новой жизни Эхнатон велел построить новую столицу между Фивами и Мемфисом, назвал ее Ахет-Атон – «Горизонт Атона». Королевский дворец из белого камня занимал площадь в 20 гектаров. Единоличная царская власть укрепилась еще сильнее, влияние прежнего государственного аппарата не сказывалось, во всяком случае, внешне на решении вопросов.

Обижал Аменхотеп IV и соседей, перестал посылать подарки, заключал политические союзы с одними государствами, забывая о прежних отношениях с другими. Но по большей части египетский фараон сохранил дипломатические связи с Ассирией, Вавилоном, Миттанией.

Личная жизнь

Родственные связи в Древнем Египте представляют клубок загадок даже для ученых умов, не то что для простых обывателей. Результатом одних таких исследований стал вывод о том, что от связи Эхнатона с собственной сестрой родился будущий фараон Тутанхамон. Имя девушки в научных кругах зашифровано и звучит как KV35YL (по месту обнаружения мумии), в некоторых источниках — Бакетатон или Небеттах.

Самой известной женой фараона считается красавица Нефертити. По неподтвержденным данным, и у нее с Эхнатоном был один отец. Супруга родила Эхнатону 6 дочерей. После смерти одной из них, Макетатон, царица сошла с политической арены, а место матери, как ни странно, заняла дочь Меритатон. Правда, до нее царь Египта, опять же предположительно, обзавелся дочерью от второй жены Кийи.

Нефертити обладала невероятным влиянием, сопровождала мужа в поездках и практически была его главным советником. На широко тиражируемых фото скульптура жены фараона запечатлена в синем парике (или царском головном уборе), украшенном изображением богини-кобры.

Сменхкар, рано скончавшийся муж Меритатон, также приписывается в близкие родственники Эхнатону – то ли брат, то ли сын.

Еще четыре сестры, как полагает часть историков, умерли в юности. Третья по счету Анхесенамон стала женой Тутанхамона. После смерти Эхнатона, взойдя на престол, дети отказались от религиозных реформ отца.

История сохранила древние источники, в которых упоминается имя Тадухепы, несостоявшейся невесты отца Эхнатона и доставшейся ему «по наследству».

Смерть

Упоминаний о том, как завершилась эра Эхнатона, не сохранилось. Предположительно, фараона отравили. Преемники сделали все, чтобы имя «Угодного Атону» исчезло из памяти народа и материальных носителей.

Гробницу в Амарне Эхнатон повелел соорудить, как это было принято, еще при жизни. После того как столицу Египта вновь перенесли в Фивы, мумию фараона перезахоронили в Долине Царей. Египтологи считают, что это могила под кодом KV55.

В 1907 году американский исследователь Теодор Дэвис вскрыл захоронение и решил, что там погребен Тутанхамон. По другой версии, мумия — это Сменхкар.

Жизнь и смерть фараона-реформатора, причины, побудившие Эхнатона на одно из самых заметных преобразований древности, становятся предметом литературных изысканий. Особенный интерес вызывают легенды о проклятиях, которые настигают беспринципных искателей сокровищ в древних могилах.

Среди научных и художественных книг читателям известны романы Тома Холланда «Спящий в песках» и Паулины Гейдж «Проклятие любви», монография Юрия Перепелкина «Кэйе и Семнех-ке-рэ. К исходу солнцепоклоннического переворота в Египте».

Память

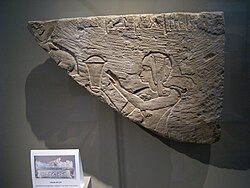

- Рельеф Эхнатона и Нефертити. Бруклинский музей

- Рельеф «Эхнатон, Нефертити и их дети». Египетский музей в Берлине

- Скульптура, изображающая Эхнатона и Нефертити на девятом году их царствования. Лувр, Париж

- Рельеф «Эхнатон в образе сфинкса перед солнечным диском Атоном». Музей Кестнера в Ганновере, Германия

- Городище Тель эль-Амарна (бывшая столица Ахет-Атон). Каир, Египет

- 2008 – приключенческий боевик «Джек Хантер. Проклятие гробницы Эхнатона». Режиссер Терри Каннингем.

- Головоломка «Сокровище Эхнатона». Часть мультиплатформенной компьютерной игры Assassin’s Creed Origins

|

|

|---|---|

| Amenophis IV, Naphurureya, Ikhnaton[1][2] | |

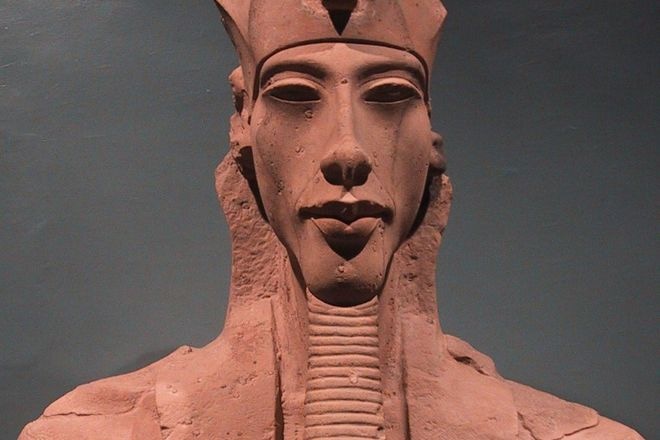

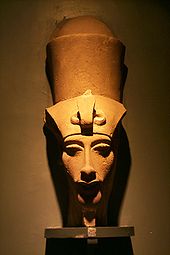

Statue of Akhenaten at the Egyptian Museum |

|

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign |

(18th Dynasty of Egypt) |

| Predecessor | Amenhotep III |

| Successor | Smenkhkare |

|

Royal titulary |

|

| Consort |

|

| Children |

|

| Father | Amenhotep III |

| Mother | Tiye |

| Died | 1336 or 1334 BC |

| Burial |

[6][7] |

| Monuments | Akhetaten, Gempaaten |

| Religion |

|

Akhenaten (pronounced ),[8] also spelled Echnaton,[9] Akhenaton,[3][10][11] (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ-n-jtn ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy, pronounced [ˈʔuːχəʔ nə ˈjaːtəj],[12][13] meaning «Effective for the Aten»), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning c. 1353–1336[3] or 1351–1334 BC,[4] the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before the fifth year of his reign, he was known as Amenhotep IV (Ancient Egyptian: jmn-ḥtp, meaning «Amun is satisfied», Hellenized as Amenophis IV).

As a pharaoh, Akhenaten is noted for abandoning Egypt’s traditional polytheism and introducing Atenism, or worship centered around Aten. The views of Egyptologists differ as to whether the religious policy was absolutely monotheistic, or whether it was monolatry, syncretistic, or henotheistic.[14][15] This culture shift away from traditional religion was reversed after his death. Akhenaten’s monuments were dismantled and hidden, his statues were destroyed, and his name excluded from lists of rulers compiled by later pharaohs.[16] Traditional religious practice was gradually restored, notably under his close successor Tutankhamun, who changed his name from Tutankhaten early in his reign.[17] When some dozen years later, rulers without clear rights of succession from the Eighteenth Dynasty founded a new dynasty, they discredited Akhenaten and his immediate successors and referred to Akhenaten as «the enemy» or «that criminal» in archival records.[18][19]

Akhenaten was all but lost to history until the late-19th-century discovery of Amarna, or Akhetaten, the new capital city he built for the worship of Aten.[20] Furthermore, in 1907, a mummy that could be Akhenaten’s was unearthed from the tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings by Edward R. Ayrton. Genetic testing has determined that the man buried in KV55 was Tutankhamun’s father,[21] but its identification as Akhenaten has since been questioned.[6][7][22][23][24]

Akhenaten’s rediscovery and Flinders Petrie’s early excavations at Amarna sparked great public interest in the pharaoh and his queen Nefertiti. He has been described as «enigmatic», «mysterious», «revolutionary», «the greatest idealist of the world», and «the first individual in history», but also as a «heretic», «fanatic», «possibly insane», and «mad».[14][25][26][27][28] Public and scholarly fascination with Akhenaten comes from his connection with Tutankhamun, the unique style and high quality of the pictorial arts he patronized, and the religion he attempted to establish, foreshadowing monotheism.

Family

The future Akhenaten was born Amenhotep, a younger son of pharaoh Amenhotep III and his principal wife Tiye. Akhenaten had an elder brother, crown prince Thutmose, who was recognized as Amenhotep III’s heir. Akhenaten also had four or five sisters: Sitamun, Henuttaneb, Iset, Nebetah, and possibly Beketaten.[29] Thutmose’s early death, perhaps around Amenhotep III’s thirtieth regnal year, meant that Akhenaten was next in line for Egypt’s throne.[30]

Akhenaten was married to Nefertiti, his Great Royal Wife. The exact timing of their marriage is unknown, but inscriptions from the pharaoh’s building projects suggest that they married either shortly before or after Akhenaten took the throne.[11] For example, Egyptologist Dimitri Laboury suggests that the marriage took place in Akhenaten’s fourth regnal year.[31] A secondary wife of Akhenaten named Kiya is also known from inscriptions. Some Egyptologists theorize that she gained her importance as the mother of Tutankhamun.[32] William Murnane proposes that Kiya is the colloquial name of the Mitanni princess Tadukhipa, daughter of the Mitanni king Tushratta who had married Amenhotep III before becoming the wife of Akhenaten.[33][34] Akhenaten’s other attested consorts are the daughter of the Enišasi ruler Šatiya and another daughter of the Babylonian king Burna-Buriash II.[35]

Akhenaten could have had seven or eight children based on inscriptions. Egyptologists are fairly certain about his six daughters, who are well attested in contemporary depictions.[36] Among his six daughters, Meritaten was born in regnal year one or five; Meketaten in year four or six; Ankhesenpaaten, later queen of Tutankhamun, before year five or eight; Neferneferuaten Tasherit in year eight or nine; Neferneferure in year nine or ten; and Setepenre in year ten or eleven.[37][38][39][40] Tutankhamun, born Tutankhaten, was most likely Akhenaten’s son, with Nefertiti or another wife.[41][42] There is less certainty around Akhenaten’s relationship with Smenkhkare, Akhenaten’s coregent or successor[43] and husband to his daughter Meritaten; he could have been Akhenaten’s eldest son with an unknown wife or Akhenaten’s younger brother.[44][45]

Some historians, such as Edward Wente and James Allen, have proposed that Akhenaten took some of his daughters as wives or sexual consorts to father a male heir.[46][47] While this is debated, some historical parallels exist: Akhenaten’s father Amenhotep III married his daughter Sitamun, while Ramesses II married two or more of his daughters, even though their marriages might simply have been ceremonial.[48][49] In Akhenaten’s case, his oldest daughter Meritaten is recorded as Great Royal Wife to Smenkhkare but is also listed on a box from Tutankhamun’s tomb alongside pharaohs Akhenaten and Neferneferuaten as Great Royal Wife. Additionally, letters written to Akhenaten from foreign rulers make reference to Meritaten as «mistress of the house.» Egyptologists in the early 20th century also believed that Akhenaten could have fathered a child with his second oldest daughter Meketaten. Meketaten’s death, at perhaps age ten to twelve, is recorded in the royal tombs at Akhetaten from around regnal years thirteen or fourteen. Early Egyptologists attribute her death to childbirth, because of the depiction of an infant in her tomb. Because no husband is known for Meketaten, the assumption had been that Akhenaten was the father. Aidan Dodson believes this to be unlikely, as no Egyptian tomb has been found that mentions or alludes to the cause of death of the tomb owner. Further, Jacobus van Dijk proposes that the child is a portrayal of Meketaten’s soul.[50] Finally, various monuments, originally for Kiya, were reinscribed for Akhenaten’s daughters Meritaten and Ankhesenpaaten. The revised inscriptions list a Meritaten-tasherit («junior») and an Ankhesenpaaten-tasherit. According to some, this indicates that Akhenaten fathered his own grandchildren. Others hold that, since these grandchildren are not attested to elsewhere, they are fictions invented to fill the space originally portraying Kiya’s child.[46][51]

Early life

Akhenaten’s elder brother Thutmose, shown in his role as High Priest of Ptah. Akhenaten became heir to the throne after Thutmose died during their father’s reign.

Egyptologists know very little about Akhenaten’s life as prince Amenhotep. Donald B. Redford dates his birth before his father Amenhotep III’s 25th regnal year, c. 1363–1361 BC, based on the birth of Akhenaten’s first daughter, who was likely born fairly early in his own reign.[4][52] The only mention of his name, as «the King’s Son Amenhotep,» was found on a wine docket at Amenhotep III’s Malkata palace, where some historians suggested Akhenaten was born. Others contend that he was born at Memphis, where growing up he was influenced by the worship of the sun god Ra practiced at nearby Heliopolis.[53] Redford and James K. Hoffmeier state, however, that Ra’s cult was so widespread and established throughout Egypt that Akhenaten could have been influenced by solar worship even if he did not grow up around Heliopolis.[54][55]

Some historians have tried to determine who was Akhenaten’s tutor during his youth, and have proposed scribes Heqareshu or Meryre II, the royal tutor Amenemotep, or the vizier Aperel.[56] The only person we know for certain served the prince was Parennefer, whose tomb mentions this fact.[57]

Egyptologist Cyril Aldred suggests that prince Amenhotep might have been a High Priest of Ptah in Memphis, although no evidence supporting this had been found.[58] It is known that Amenhotep’s brother, crown prince Thutmose, served in this role before he died. If Amenhotep inherited all his brother’s roles in preparation for his accession to the throne, he might have become a high priest in Thutmose’s stead. Aldred proposes that Akhenaten’s unusual artistic inclinations might have been formed during his time serving Ptah, the patron god of craftsmen, whose high priest were sometimes referred to as «The Greatest of the Directors of Craftsmanship.»[59]

Reign

Coregency with Amenhotep III

There is much controversy around whether Amenhotep IV ascended to Egypt’s throne on the death of his father Amenhotep III or whether there was a coregency, lasting perhaps as long as 12 years. Eric Cline, Nicholas Reeves, Peter Dorman, and other scholars argue strongly against the establishment of a long coregency between the two rulers and in favor of either no coregency or one lasting at most two years.[60] Donald B. Redford, William J. Murnane, Alan Gardiner, and Lawrence Berman contest the view of any coregency whatsoever between Akhenaten and his father.[61][62]

Most recently, in 2014, archaeologists found both pharaohs’ names inscribed on the wall of the Luxor tomb of vizier Amenhotep-Huy. The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities called this «conclusive evidence» that Akhenaten shared power with his father for at least eight years, based on the dating of the tomb.[63] However, this conclusion has since been called into question by other Egyptologists, according to whom the inscription only means that construction on Amenhotep-Huy’s tomb started during Amenhotep III’s reign and ended under Akhenaten’s, and Amenhotep-Huy thus simply wanted to pay his respects to both rulers.[64]

Early reign as Amenhotep lV

Akhenaten took Egypt’s throne as Amenhotep IV, most likely in 1353[65] or 1351 BC.[4] It is unknown how old Amenhotep IV was when he did this; estimates range from 10 to 23.[66] He was most likely crowned in Thebes, or less likely at Memphis or Armant.[66]

The beginning of Amenhotep IV’s reign followed established pharaonic traditions. He did not immediately start redirecting worship toward the Aten and distancing himself from other gods. Egyptologist Donald B. Redford believes this implied that Amenhotep IV’s eventual religious policies were not conceived of before his reign, and he did not follow a pre-established plan or program. Redford points to three pieces of evidence to support this. First, surviving inscriptions show Amenhotep IV worshipping several different gods, including Atum, Osiris, Anubis, Nekhbet, Hathor,[67] and the Eye of Ra, and texts from this era refer to «the gods» and «every god and every goddess.» The High Priest of Amun was also still active in the fourth year of Amenhotep IV’s reign.[68] Second, even though he later moved his capital from Thebes to Akhetaten, his initial royal titulary honored Thebes—his nomen was «Amenhotep, god-ruler of Thebes»—and recognizing its importance, he called the city «Southern Heliopolis, the first great (seat) of Re (or) the Disc.» Third, Amenhotep IV did not yet destroy temples to the other gods and he even continued his father’s construction projects at Karnak’s Precinct of Amun-Re.[69] He decorated the walls of the precinct’s Third Pylon with images of himself worshipping Ra-Horakhty, portrayed in the god’s traditional form of a falcon-headed man.[70]

Artistic depictions continued unchanged early in Amenhotep IV’s reign. Tombs built or completed in the first few years after he took the throne, such as those of Kheruef, Ramose, and Parennefer, show the pharaoh in the traditional artistic style.[71] In Ramose’s tomb, Amenhotep IV appears on the west wall, seated on a throne, with Ramose appearing before the pharaoh. On the other side of the doorway, Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti are shown in the window of appearances, with the Aten depicted as the sun disc. In Parennefer’s tomb, Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti are seated on a throne with the sun disc depicted over the pharaoh and his queen.[71]

While continuing the worship of other gods, Amenhotep IV’s initial building program sought to build new places of worship to the Aten. He ordered the construction of temples or shrines to the Aten in several cities across the country, such as Bubastis, Tell el-Borg, Heliopolis, Memphis, Nekhen, Kawa, and Kerma.[72] He also ordered the construction of a large temple complex dedicated to the Aten at Karnak in Thebes, northeast of the parts of the Karnak complex dedicated to Amun. The Aten temple complex, collectively known as the Per Aten («House of the Aten»), consisted of several temples whose names survive: the Gempaaten («The Aten is found in the estate of the Aten»), the Hwt Benben («House or Temple of the Benben»), the Rud-Menu («Enduring of monuments for Aten forever»), the Teni-Menu («Exalted are the monuments of the Aten forever»), and the Sekhen Aten («booth of Aten»).[73]

Around regnal year two or three, Amenhotep IV organized a Sed festival. Sed festivals were ritual rejuvenations of an aging pharaoh, which usually took place for the first time around the thirtieth year of a pharaoh’s reign and every three or so years thereafter. Egyptologists only speculate as to why Amenhotep IV organized a Sed festival when he was likely still in his early twenties. Some historians see it as evidence for Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV’s coregency, and believed that Amenhotep IV’s Sed festival coincided with one of his father’s celebrations. Others speculate that Amenhotep IV chose to hold his festival three years after his father’s death, aiming to proclaim his rule a continuation of his father’s reign. Yet others believe that the festival was held to honor the Aten on whose behalf the pharaoh ruled Egypt, or, as Amenhotep III was considered to have become one with the Aten following his death, the Sed festival honored both the pharaoh and the god at the same time. It is also possible that the purpose of the ceremony was to figuratively fill Amenhotep IV with strength before his great enterprise: the introduction of the Aten cult and the founding of the new capital Akhetaten. Regardless of the celebration’s aim, Egyptologists believe that during the festivities Amenhotep IV only made offerings to the Aten rather than the many gods and goddesses, as was customary.[59][74][75]

Name change

Among the last documents that refer to Akhenaten as Amenhotep IV are two copies of a letter to the pharaoh from Ipy, the high steward of Memphis. These letters, found in Gurob and informing the pharaoh that the royal estates in Memphis are «in good order» and the temple of Ptah is «prosperous and flourishing,» are dated to regnal year five, day nineteen of the growing season’s third month. About a month later, day thirteen of the growing season’s fourth month, one of the boundary stela at Akhetaten already had the name Akhenaten carved on it, implying that the pharaoh changed his name between the two inscriptions.[76][77][78][79]

Amenhotep IV changed his royal titulary to show his devotion to the Aten. No longer would he be known as Amenhotep IV and be associated with the god Amun, but rather he would completely shift his focus to the Aten. Egyptologists debate the exact meaning of Akhenaten, his new personal name. The word «akh» (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ) could have different translations, such as «satisfied,» «effective spirit,» or «serviceable to,» and thus Akhenaten’s name could be translated to mean «Aten is satisfied,» «Effective spirit of the Aten,» or «Serviceable to the Aten,» respectively.[80] Gertie Englund and Florence Friedman arrive at the translation «Effective for the Aten» by analyzing contemporary texts and inscriptions, in which Akhenaten often described himself as being «effective for» the sun disc. Englund and Friedman conclude that the frequency with which Akhenaten used this term likely means that his own name meant «Effective for the Aten.»[80]

Some historians, such as William F. Albright, Edel Elmar, and Gerhard Fecht, propose that Akhenaten’s name is misspelled and mispronounced. These historians believe «Aten» should rather be «Jāti,» thus rendering the pharaoh’s name Akhenjāti or Aḫanjāti (pronounced ), as it could have been pronounced in Ancient Egypt.[81][82][83]

| Amenhotep IV | Akhenaten | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name |

Kanakht-qai-Shuti «Strong Bull of the Double Plumes» |

Meryaten «Beloved of Aten» |

|||||||||||||||||

| Nebty name |

Wer-nesut-em-Ipet-swt «Great of Kingship in Karnak» |

Wer-nesut-em-Akhetaten «Great of Kingship in Akhet-Aten» |

|||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus name |

Wetjes-khau-em-Iunu-Shemay «Crowned in Heliopolis of the South» (Thebes) |

Wetjes-ren-en-Aten «Exalter of the Name of Aten» |

|||||||||||||||||

| Prenomen |

Neferkheperure-waenre |

||||||||||||||||||

| Nomen | Amenhotep Netjer-Heqa-Waset

«Amun is Satisfied, Divine Lord of Thebes» |

Akhenaten «Effective for the Aten» |

Founding Amarna

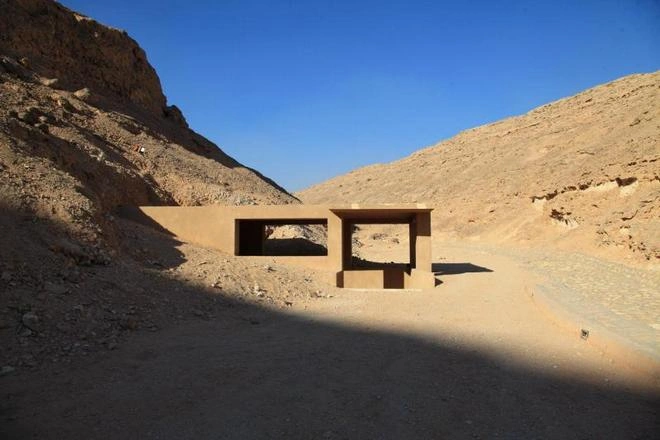

One of the stele marking the boundary of the new capital Akhetaten

Around the same time he changed his royal titulary, on the thirteenth day of the growing season’s fourth month, Akhenaten decreed that a new capital city be built: Akhetaten (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫt-jtn, meaning «Horizon of the Aten»), better known today as Amarna. The events Egyptologists know the most about during Akhenaten’s life are connected with founding Akhetaten, as several so-called boundary stelae were found around the city to mark its boundary.[84] The pharaoh chose a site about halfway between Thebes, the capital at the time, and Memphis, on the east bank of the Nile, where a wadi and a natural dip in the surrounding cliffs form a silhouette similar to the «horizon» hieroglyph. Additionally, the site had previously been uninhabited. According to inscriptions on one boundary stela, the site was appropriate for Aten’s city for «not being the property of a god, nor being the property of a goddess, nor being the property of a ruler, nor being the property of a female ruler, nor being the property of any people able to lay claim to it.»[85]

Historians do not know for certain why Akhenaten established a new capital and left Thebes, the old capital. The boundary stelae detailing Akhetaten’s founding is damaged where it likely explained the pharaoh’s motives for the move. Surviving parts claim what happened to Akhenaten was «worse than those that I heard» previously in his reign and worse than those «heard by any kings who assumed the White Crown,» and alludes to «offensive» speech against the Aten. Egyptologists believe that Akhenaten could be referring to conflict with the priesthood and followers of Amun, the patron god of Thebes. The great temples of Amun, such as Karnak, were all located in Thebes and the priests there achieved significant power earlier in the Eighteenth Dynasty, especially under Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, thanks to pharaohs offering large amounts of Egypt’s growing wealth to the cult of Amun; historians, such as Donald B. Redford, therefore posited that by moving to a new capital, Akhenaten may have been trying to break with Amun’s priests and the god.[86][87][88]

Akhetaten was a planned city with the Great Temple of the Aten, Small Aten Temple, royal residences, records office, and government buildings in the city center. Some of these buildings, such as the Aten temples, were ordered to be built by Akhenaten on the boundary stela decreeing the city’s founding.[87][89][90]

The city was built quickly, thanks to a new construction method that used substantially smaller building blocks than under previous pharaohs. These blocks, called talatats, measured 1⁄2 by 1⁄2 by 1 ancient Egyptian cubits (c. 27 by 27 by 54 cm), and because of the smaller weight and standardized size, using them during constructions was more efficient than using heavy building blocks of varying sizes.[91][92] By regnal year eight, Akhetaten reached a state where it could be occupied by the royal family. Only his most loyal subjects followed Akhenaten and his family to the new city. While the city continued to be built, in years five through eight, construction work began to stop in Thebes. The Theban Aten temples that had begun were abandoned, and a village of those working on Valley of the Kings tombs was relocated to the workers’ village at Akhetaten. However, construction work continued in the rest of the country, as larger cult centers, such as Heliopolis and Memphis, also had temples built for Aten.[93][94]

International relations

Painted limestone miniature stela. It shows Akhenaten standing before 2 incense stands, Aten disc above. From Amarna, Egypt – 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

The Amarna letters have provided important evidence about Akhenaten’s reign and foreign policy. The letters are a cache of 382 diplomatic texts and literary and educational materials discovered between 1887 and 1979,[95] and named after Amarna, the modern name for Akhenaten’s capital Akhetaten. The diplomatic correspondence comprises clay tablet messages between Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun, various subjects through Egyptian military outposts, rulers of vassal states, and the foreign rulers of Babylonia, Assyria, Syria, Canaan, Alashiya, Arzawa, Mitanni, and the Hittites.[96]

The Amarna letters portray the international situation in the Eastern Mediterranean that Akhenaten inherited from his predecessors. In the 200 years preceding Akhenaten’s reign, following the expulsion of the Hyksos from Lower Egypt at the end of the Second Intermediate Period, the kingdom’s influence and military might increased greatly. Egypt’s power reached new heights under Thutmose III, who ruled approximately 100 years before Akhenaten and led several successful military campaigns into Nubia and Syria. Egypt’s expansion led to confrontation with the Mitanni, but this rivalry ended with the two nations becoming allies. Slowly, however, Egypt’s power started to wane. Amenhotep III aimed to maintain the balance of power through marriages—such as his marriage to Tadukhipa, daughter of the Mitanni king Tushratta—and vassal states. Under Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, Egypt was unable or unwilling to oppose the rise of the Hittites around Syria. The pharaohs seemed to eschew military confrontation at a time when the balance of power between Egypt’s neighbors and rivals was shifting, and the Hittites, a confrontational state, overtook the Mitanni in influence.[97][98][99][100]

Early in his reign, Akhenaten was evidently concerned about the expanding power of the Hittite Empire under Šuppiluliuma I. A successful Hittite attack on Mitanni and its ruler Tushratta would have disrupted the entire international balance of power in the Ancient Middle East at a time when Egypt had made peace with Mitanni; this would cause some of Egypt’s vassals to switch their allegiances to the Hittites, as time would prove. A group of Egypt’s allies who attempted to rebel against the Hittites were captured, and wrote letters begging Akhenaten for troops, but he did not respond to most of their pleas. Evidence suggests that the troubles on the northern frontier led to difficulties in Canaan, particularly in a struggle for power between Labaya of Shechem and Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem, which required the pharaoh to intervene in the area by dispatching Medjay troops northwards. Akhenaten pointedly refused to save his vassal Rib-Hadda of Byblos—whose kingdom was being besieged by the expanding state of Amurru under Abdi-Ashirta and later Aziru, son of Abdi-Ashirta—despite Rib-Hadda’s numerous pleas for help from the pharaoh. Rib-Hadda wrote a total of 60 letters to Akhenaten pleading for aid from the pharaoh. Akhenaten wearied of Rib-Hadda’s constant correspondences and once told Rib-Hadda: «You are the one that writes to me more than all the (other) mayors» or Egyptian vassals in EA 124.[101] What Rib-Hadda did not comprehend was that the Egyptian king would not organize and dispatch an entire army north just to preserve the political status quo of several minor city states on the fringes of Egypt’s Asiatic Empire.[102] Rib-Hadda would pay the ultimate price; his exile from Byblos due to a coup led by his brother Ilirabih is mentioned in one letter. When Rib-Hadda appealed in vain for aid from Akhenaten and then turned to Aziru, his sworn enemy, to place him back on the throne of his city, Aziru promptly had him dispatched to the king of Sidon, where Rib-Hadda was almost certainly executed.[103]

In a view discounted by the 21st century,[104] several Egyptologists in the late 19th and 20th centuries interpreted the Amarna letters to mean that Akhenaten was a pacifist who neglected foreign policy and Egypt’s foreign territories in favor of his internal reforms. For example, Henry Hall believed Akhenaten «succeeded by his obstinate doctrinaire love of peace in causing far more misery in his world than half a dozen elderly militarists could have done,»[105] while James Henry Breasted said Akhenaten «was not fit to cope with a situation demanding an aggressive man of affairs and a skilled military leader.»[106] Others noted that the Amarna letters counter the conventional view that Akhenaten neglected Egypt’s foreign territories in favour of his internal reforms. For instance, Norman de Garis Davies praised Akhenaten’s emphasis on diplomacy over war, while James Baikie said that the fact «that there is no evidence of revolt within the borders of Egypt itself during the whole reign is surely ample proof that there was no such abandonment of his royal duties on the part of Akhenaten as has been assumed.»[107][108] Indeed, several letters from Egyptian vassals notified the pharaoh that they have followed his instructions, implying that the pharaoh sent such instructions.[109] The Amarna letters also show that vassal states were told repeatedly to expect the arrival of the Egyptian military on their lands, and provide evidence that these troops were dispatched and arrived at their destination. Dozens of letters detail that Akhenaten—and Amenhotep III—sent Egyptian and Nubian troops, armies, archers, chariots, horses, and ships.[110]

Only one military campaign is known for certain under Akhenaten’s reign. In his second or twelfth year,[111] Akhenaten ordered his Viceroy of Kush Tuthmose to lead a military expedition to quell a rebellion and raids on settlements on the Nile by Nubian nomadic tribes. The victory was commemorated on two stelae, one discovered at Amada and another at Buhen. Egyptologists differ on the size of the campaign: Wolfgang Helck considered it a small-scale police operation, while Alan Schulman considered it a «war of major proportions.»[112][113][114]

Other Egyptologists suggested that Akhenaten could have waged war in Syria or the Levant, possibly against the Hittites. Cyril Aldred, based on Amarna letters describing Egyptian troop movements, proposed that Akhenaten launched an unsuccessful war around the city of Gezer, while Marc Gabolde argued for an unsuccessful campaign around Kadesh. Either of these could be the campaign referred to on Tutankhamun’s Restoration Stela: «if an army was sent to Djahy [southern Canaan and Syria] to broaden the boundaries of Egypt, no success of their cause came to pass.»[115][116][117] John Coleman Darnell and Colleen Manassa also argued that Akhenaten fought with the Hittites for control of Kadesh, but was unsuccessful; the city was not recaptured until 60–70 years later, under Seti I.[118]

Overall, archeological evidence suggests that Akhenaten paid close attention to the affairs of Egyptian vassals in Canaan and Syria, though primarily not through letters such as those found at Amarna but through reports from government officials and agents. Akhenaten managed to preserve Egypt’s control over the core of its Near Eastern Empire (which consisted of present-day Israel as well as the Phoenician coast) while avoiding conflict with the increasingly powerful and aggressive Hittite Empire of Šuppiluliuma I, which overtook the Mitanni as the dominant power in the northern part of the region. Only the Egyptian border province of Amurru in Syria around the Orontes River was lost to the Hittites when its ruler Aziru defected to the Hittites; ordered by Akhenaten to come to Egypt, Aziru was released after promising to stay loyal to the pharaoh, nonetheless turning to the Hittites soon after his release.[119]

Later years

In regnal year twelve, Akhenaten received tributes and offerings from allied countries and vassal states at Akhetaten, as depicted in the tomb of Meryra II.

Egyptologists know little about the last five years of Akhenaten’s reign, beginning in c. 1341[3] or 1339 BC.[4] These years are poorly attested and only a few pieces of contemporary evidence survive; the lack of clarity makes reconstructing the latter part of the pharaoh’s reign «a daunting task» and a controversial and contested topic of discussion among Egyptologists.[120] Among the newest pieces of evidence is an inscription discovered in 2012 at a limestone quarry in Deir el-Bersha, just north of Akhetaten, from the pharaoh’s sixteenth regnal year. The text refers to a building project in Amarna and establishes that Akhenaten and Nefertiti were still a royal couple just a year before Akhenaten’s death.[121][122][123] The inscription is dated to Year 16, month 3 of Akhet, day 15 of the reign of Akhenaten.[121]

Before the 2012 discovery of the Deir el-Bersha inscription, the last known fixed-date event in Akhenaten’s reign was a royal reception in regnal year twelve, in which the pharaoh and the royal family received tributes and offerings from allied countries and vassal states at Akhetaten. Inscriptions show tributes from Nubia, the Land of Punt, Syria, the Kingdom of Hattusa, the islands in the Mediterranean Sea, and Libya. Egyptologists, such as Aidan Dodson, consider this year twelve celebration to be the zenith of Akhenaten’s reign.[124] Thanks to reliefs in the tomb of courtier Meryre II, historians know that the royal family, Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their six daughters, were present at the royal reception in full.[124] However, historians are uncertain about the reasons for the reception. Possibilities include the celebration of the marriage of future pharaoh Ay to Tey, celebration of Akhenaten’s twelve years on the throne, the summons of king Aziru of Amurru to Egypt, a military victory at Sumur in the Levant, a successful military campaign in Nubia,[125] Nefertiti’s ascendancy to the throne as coregent, or the completion of the new capital city Akhetaten.[126]

Following year twelve, Donald B. Redford and other Egyptologists proposed that Egypt was struck by an epidemic, most likely a plague.[127] Contemporary evidence suggests that a plague ravaged through the Middle East around this time,[128] and ambassadors and delegations arriving to Akhenaten’s year twelve reception might have brought the disease to Egypt.[129] Alternatively, letters from the Hattians might suggest that the epidemic originated in Egypt and was carried throughout the Middle East by Egyptian prisoners of war.[130] Regardless of its origin, the epidemic might account for several deaths in the royal family that occurred in the last five years of Akhenaten’s reign, including those of his daughters Meketaten, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.[131][132]

Coregency with Smenkhkare or Nefertiti

Akhenaten could have ruled together with Smenkhkare and Nefertiti for several years before his death.[133][134] Based on depictions and artifacts from the tombs of Meryre II and Tutankhamun, Smenkhkare could have been Akhenaten’s coregent by regnal year thirteen or fourteen, but died a year or two later. Nefertiti might not have assumed the role of coregent until after year sixteen, when a stela still mentions her as Akhenaten’s Great Royal Wife. While Nefertiti’s familial relationship with Akhenaten is known, whether Akhenaten and Smenkhkare were related by blood is unclear. Smenkhkare could have been Akhenaten’s son or brother, as the son of Amenhotep III with Tiye or Sitamun.[135] Archaeological evidence makes it clear, however, that Smenkhkare was married to Meritaten, Akhenaten’s eldest daughter.[136] For another, the so-called Coregency Stela, found in a tomb at Akhetaten, might show queen Nefertiti as Akhenaten’s coregent, but this is uncertain as the stela was recarved to show the names of Ankhesenpaaten and Neferneferuaten.[137] Egyptologist Aidan Dodson proposed that both Smenkhkare and Neferiti were Akhenaten’s coregents to ensure the Amarna family’s continued rule when Egypt was confronted with an epidemic. Dodson suggested that the two were chosen to rule as Tutankhaten’s coregent in case Akhenaten died and Tutankhaten took the throne at a young age, or rule in Tutankhaten’s stead if the prince also died in the epidemic.[43]

Death and burial

The desecrated royal coffin found in Tomb KV55

Akhenaten died after seventeen years of rule and was initially buried in a tomb in the Royal Wadi east of Akhetaten. The order to construct the tomb and to bury the pharaoh there was commemorated on one of the boundary stela delineating the capital’s borders: «Let a tomb be made for me in the eastern mountain [of Akhetaten]. Let my burial be made in it, in the millions of jubilees which the Aten, my father, decreed for me.»[138] In the years following the burial, Akhenaten’s sarcophagus was destroyed and left in the Akhetaten necropolis; reconstructed in the 20th century, it is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo as of 2019.[139] Despite leaving the sarcophagus behind, Akhenaten’s mummy was removed from the royal tombs after Tutankhamun abandoned Akhetaten and returned to Thebes. It was most likely moved to tomb KV55 in Valley of the Kings near Thebes.[140][141] This tomb was later desecrated, likely during the Ramesside period.[142][143]

Whether Smenkhkare also enjoyed a brief independent reign after Akhenaten is unclear.[144] If Smenkhkare outlived Akhenaten, and became sole pharaoh, he likely ruled Egypt for less than a year. The next successor was Nefertiti[145] or Meritaten[146] ruling as Neferneferuaten, reigning in Egypt for about two years.[147] She was, in turn, probably succeeded by Tutankhaten, with the country being administered by the vizier and future pharaoh Ay.[148]

Profile view of the skull (thought to be Akhenaten) recovered from KV55

While Akhenaten—along with Smenkhkare—was most likely reburied in tomb KV55,[149] the identification of the mummy found in that tomb as Akhenaten remains controversial to this day. The mummy has repeatedly been examined since its discovery in 1907. Most recently, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass led a team of researchers to examine the mummy using medical and DNA analysis, with the results published in 2010. In releasing their test results, Hawass’s team identified the mummy as the father of Tutankhamun and thus «most probably» Akhenaten.[150] However, the study’s validity has since been called into question.[6][7][151][152][153] For instance, the discussion of the study results does not discuss that Tutankhamun’s father and the father’s siblings would share some genetic markers; if Tutankhamun’s father was Akhenaten, the DNA results could indicate that the mummy is a brother of Akhenaten, possibly Smenkhkare.[153][154]

Legacy

With Akhenaten’s death, the Aten cult he had founded fell out of favor: at first gradually, and then with decisive finality. Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun in Year 2 of his reign (c. 1332 BC) and abandoned the city of Akhetaten.[155] Their successors then attempted to erase Akhenaten and his family from the historical record. During the reign of Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the first pharaoh after Akhenaten who was not related to Akhenaten’s family, Egyptians started to destroy temples to the Aten and reuse the building blocks in new construction projects, including in temples for the newly restored god Amun. Horemheb’s successor continued in this effort. Seti I restored monuments to Amun and had the god’s name re-carved on inscriptions where it was removed by Akhenaten. Seti I also ordered that Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Neferneferuaten, Tutankhamun, and Ay be excised from official lists of pharaohs to make it appear that Amenhotep III was immediately succeeded by Horemheb. Under the Ramessides, who succeeded Seti I, Akhetaten was gradually destroyed and the building material reused across the country, such as in constructions at Hermopolis. The negative attitudes toward Akhenaten were illustrated by, for example, inscriptions in the tomb of scribe Mose (or Mes), where Akhenaten’s reign is referred to as «the time of the enemy of Akhet-Aten.»[156][157][158]

Some Egyptologists, such as Jacobus van Dijk and Jan Assmann, believe that Akhenaten’s reign and the Amarna period started a gradual decline in the Egyptian government’s power and the pharaoh’s standing in Egyptian’s society and religious life.[159][160] Akhenaten’s religious reforms subverted the relationship ordinary Egyptians had with their gods and their pharaoh, as well as the role the pharaoh played in the relationship between the people and the gods. Before the Amarna period, the pharaoh was the representative of the gods on Earth, the son of the god Ra, and the living incarnation of the god Horus, and maintained the divine order through rituals and offerings and by sustaining the temples of the gods.[161] Additionally, even though the pharaoh oversaw all religious activity, Egyptians could access their gods through regular public holidays, festivals, and processions. This led to a seemingly close connection between people and the gods, especially the patron deity of their respective towns and cities.[162] Akhenaten, however, banned the worship of gods beside the Aten, including through festivals. He also declared himself to be the only one who could worship the Aten, and required that all religious devotion previously exhibited toward the gods be directed toward himself. After the Amarna period, during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties—c. 270 years following Akhenaten’s death—the relationship between the people, the pharaoh, and the gods did not simply revert to pre-Amarna practices and beliefs. The worship of all gods returned, but the relationship between the gods and the worshipers became more direct and personal,[163] circumventing the pharaoh. Rather than acting through the pharaoh, Egyptians started to believe that the gods intervened directly in their lives, protecting the pious and punishing criminals.[164] The gods replaced the pharaoh as their own representatives on Earth. The god Amun once again became king among all gods.[165] According to van Dijk, «the king was no longer a god, but god himself had become king. Once Amun had been recognized as the true king, the political power of the earthly rulers could be reduced to a minimum.»[166] Consequently, the influence and power of the Amun priesthood continued to grow until the Twenty-first Dynasty, c. 1077 BC, by which time the High Priests of Amun effectively became rulers over parts of Egypt.[160][167][168]

Akhenaten’s reforms also had a longer-term impact on Ancient Egyptian language and hastened the spread of the spoken Late Egyptian language in official writings and speeches. Spoken and written Egyptian diverged early on in Egyptian history and stayed different over time.[169] During the Amarna period, however, royal and religious texts and inscriptions, including the boundary stelae at Akhetaten or the Amarna letters, started to regularly include more vernacular linguistic elements, such as the definite article or a new possessive form. Even though they continued to diverge, these changes brought the spoken and written language closer to one another more systematically than under previous pharaohs of the New Kingdom. While Akhenaten’s successors attempted to erase his religious, artistic, and even linguistic changes from history, the new linguistic elements remained a more common part of official texts following the Amarna years, starting with the Nineteenth Dynasty.[170][171][172]

Akehnaten is also recognized as a Prophet in the Druze faith.[173][174]

Atenism

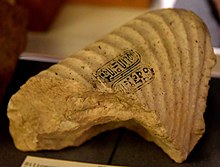

Relief fragment showing a royal head, probably Akhenaten, and early Aten cartouches. Aten extends Ankh (sign of life) to the figure. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

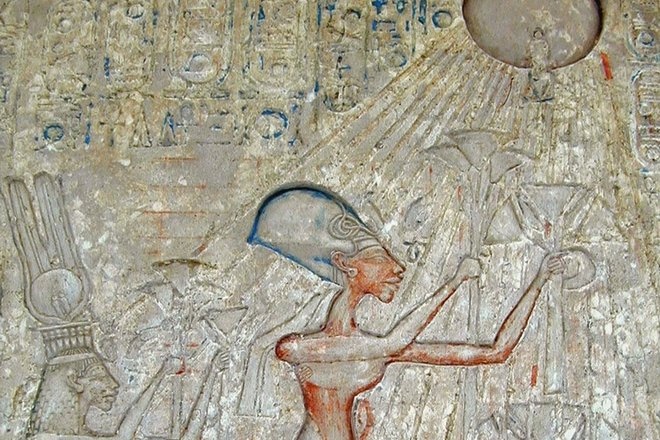

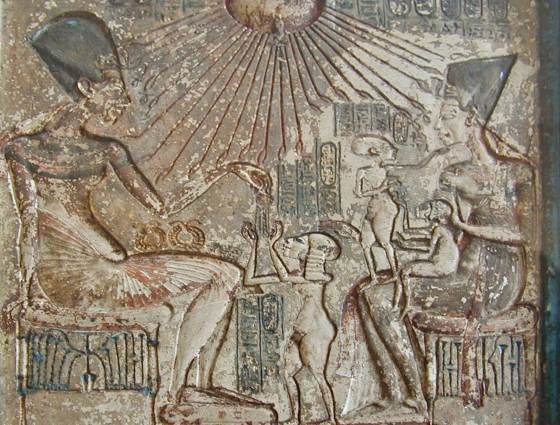

Pharaoh Akhenaten (center) and his family worshiping the Aten, with characteristic rays seen emanating from the solar disk. Later such imagery was prohibited.

Egyptians worshipped a sun god under several names, and solar worship had been growing in popularity even before Akhenaten, especially during the Eighteenth Dynasty and the reign of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten’s father.[175] During the New Kingdom, the pharaoh started to be associated with the sun disc; for example, one inscription called the pharaoh Hatshepsut the «female Re shining like the Disc,» while Amenhotep III was described as «he who rises over every foreign land, Nebmare, the dazzling disc.»[176] During the Eighteenth Dynasty, a religious hymn to the sun also appeared and became popular among Egyptians.[177] However, Egyptologists question whether there is a causal relationship between the cult of the sun disc before Akhenaten and Akhenaten’s religious policies.[177]

Implementation and development

The implementation of Atenism can be traced through gradual changes in the Aten’s iconography, and Egyptologist Donald B. Redford divided its development into three stages—earliest, intermediate, and final—in his studies of Akhenaten and Atenism. The earliest stage was associated with a growing number of depictions of the sun disc, though the disc is still seen resting on the head of the falcon-headed sun god Ra-Horakhty, as the god was traditionally represented.[178] The god was only «unique but not exclusive.»[179] The intermediate stage was marked by the elevation of the Aten above other gods and the appearance of cartouches around his inscribed name—cartouches traditionally indicating that the enclosed text is a royal name. The final stage had the Aten represented as a sun disc with sunrays like long arms terminating in human hands and the introduction of a new epithet for the god: «the great living Disc which is in jubilee, lord of heaven and earth.»[180]

In the early years of his reign, Amenhotep IV lived at Thebes, the old capital city, and permitted worship of Egypt’s traditional deities to continue. However, some signs already pointed to the growing importance of the Aten. For example, inscriptions in the Theban tomb of Parennefer from the early rule of Amenhotep IV state that «one measures the payments to every (other) god with a level measure, but for the Aten one measures so that it overflows,» indicating a more favorable attitude to the cult of Aten than the other gods.[179] Additionally, near the Temple of Karnak, Amun-Ra’s great cult center, Amenhotep IV erected several massive buildings including temples to the Aten. The new Aten temples had no roof and the god was thus worshipped in the sunlight, under the open sky, rather than in dark temple enclosures as had been the previous custom.[181][182] The Theban buildings were later dismantled by his successors and used as infill for new constructions in the Temple of Karnak; when they were later dismantled by archaeologists, some 36,000 decorated blocks from the original Aten building here were revealed that preserve many elements of the original relief scenes and inscriptions.[183]

One of the most important turning points in the early reign of Amenhotep IV is a speech given by the pharaoh at the beginning of his second regnal year. A copy of the speech survives on one of the pylons at the Karnak Temple Complex near Thebes. Speaking to the royal court, scribes or the people, Amenhotep IV said that the gods were ineffective and had ceased their movements, and that their temples had collapsed. The pharaoh contrasted this with the only remaining god, the sun disc Aten, who continued to move and exist forever. Some Egyptologists, such as Donald B. Redford, compared this speech to a proclamation or manifesto, which foreshadowed and explained the pharaoh’s later religious reforms centered around the Aten.[184][185][186] In his speech, Akhenaten said:

The temples of the gods fallen to ruin, their bodies do not endure. Since the time of the ancestors, it is the wise man that knows these things. Behold, I, the king, am speaking so that I might inform you concerning the appearances of the gods. I know their temples, and I am versed in the writings, specifically, the inventory of their primeval bodies. And I have watched as they [the gods] have ceased their appearances, one after the other. All of them have stopped, except the god who gave birth to himself. And no one knows the mystery of how he performs his tasks. This god goes where he pleases and no one else knows his going. I approach him, the things which he has made. How exalted they are.[187]

In Year Five of his reign, Amenhotep IV took decisive steps to establish the Aten as the sole god of Egypt. The pharaoh «disbanded the priesthoods of all the other gods … and diverted the income from these [other] cults to support the Aten.» To emphasize his complete allegiance to the Aten, the king officially changed his name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaten (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ-n-jtn, meaning «Effective for the Aten»).[183] Meanwhile, the Aten was becoming a king itself. Artists started to depict him with the trappings of pharaohs, placing his name in cartouches—a rare, but not unique occurrence, as the names of Ra-Horakhty and Amun-Ra had also been found enclosed in cartouches—and wearing a uraeus, a symbol of kingship.[188] The Aten may also have been the subject of Akhenaten’s royal Sed festival early in the pharaoh’s reign.[189] With Aten becoming a sole deity, Akhenaten started to proclaim himself as the only intermediary between Aten and his people, and the subject of their personal worship and attention[190]—a feature not unheard of in Egyptian history, with Fifth Dynasty pharaohs such as Nyuserre Ini proclaiming to be sole intermediaries between the people and the gods Osiris and Ra.[191]

Inscribed limestone fragment showing early Aten cartouches, «the Living Ra Horakhty». Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Fragment of a stela, showing parts of 3 late cartouches of Aten. There is a rare intermediate form of god’s name. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

By Year Nine of his reign, Akhenaten declared that Aten was not merely the supreme god, but the only worshipable god. He ordered the defacing of Amun’s temples throughout Egypt and, in a number of instances, inscriptions of the plural ‘gods’ were also removed.[192][193] This emphasized the changes encouraged by the new regime, which included a ban on images, with the exception of a rayed solar disc, in which the rays appear to represent the unseen spirit of Aten, who by then was evidently considered not merely a sun god, but rather a universal deity. All life on Earth depended on the Aten and the visible sunlight.[194][195] Representations of the Aten were always accompanied with a sort of hieroglyphic footnote, stating that the representation of the sun as all-encompassing creator was to be taken as just that: a representation of something that, by its very nature as something transcending creation, cannot be fully or adequately represented by any one part of that creation.[196] Aten’s name was also written differently starting as early as Year Eight or as late as Year Fourteen, according to some historians.[197] From «Living Re-Horakhty, who rejoices in the horizon in his name Shu-Re who is in Aten,» the god’s name changed to «Living Re, ruler of the horizon, who rejoices in his name of Re the father who has returned as Aten,» removing the Aten’s connection to Re-Horakhty and Shu, two other solar deities.[198] The Aten thus became an amalgamation that incorporated the attributes and beliefs around Re-Horakhty, universal sun god, and Shu, god of the sky and manifestation of the sunlight.[199]

Siliceous limestone fragment of a statue. There are late Aten cartouches on the draped right shoulder. Reign of Akhenaten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Akhenaten’s Atenist beliefs are best distilled in the Great Hymn to the Aten.[200] The hymn was discovered in the tomb of Ay, one of Akhenaten’s successors, though Egyptologists believe that it could have been composed by Akhenaten himself.[201][202] The hymn celebrates the sun and daylight and recounts the dangers that abound when the sun sets. It tells of the Aten as a sole god and the creator of all life, who recreates life every day at sunrise, and on whom everything on Earth depends, including the natural world, people’s lives, and even trade and commerce.[203] In one passage, the hymn declares: «O Sole God beside whom there is none! You made the earth as you wished, you alone.»[204] The hymn also states that Akhenaten is the only intermediary between the god and Egyptians, and the only one who can understand the Aten: «You are in my heart, and there is none who knows you except your son.»[205]

Atenism and other gods

Some debate has focused on the extent to which Akhenaten forced his religious reforms on his people.[206] Certainly, as time drew on, he revised the names of the Aten, and other religious language, to increasingly exclude references to other gods; at some point, also, he embarked on the wide-scale erasure of traditional gods’ names, especially those of Amun.[207] Some of his court changed their names to remove them from the patronage of other gods and place them under that of Aten (or Ra, with whom Akhenaten equated the Aten). Yet, even at Amarna itself, some courtiers kept such names as Ahmose («child of the moon god», the owner of tomb 3), and the sculptor’s workshop where the famous Nefertiti Bust and other works of royal portraiture were found is associated with an artist known to have been called Thutmose («child of Thoth»). An overwhelmingly large number of faience amulets at Amarna also show that talismans of the household-and-childbirth gods Bes and Taweret, the eye of Horus, and amulets of other traditional deities, were openly worn by its citizens. Indeed, a cache of royal jewelry found buried near the Amarna royal tombs (now in the National Museum of Scotland) includes a finger ring referring to Mut, the wife of Amun. Such evidence suggests that though Akhenaten shifted funding away from traditional temples, his policies were fairly tolerant until some point, perhaps a particular event as yet unknown, toward the end of the reign.[208]

Archaeological discoveries at Akhetaten show that many ordinary residents of this city chose to gouge or chisel out all references to the god Amun on even minor personal items that they owned, such as commemorative scarabs or make-up pots, perhaps for fear of being accused of having Amunist sympathies. References to Amenhotep III, Akhenaten’s father, were partly erased since they contained the traditional Amun form of his name: Nebmaatre Amunhotep.[209]

After Akhenaten

Following Akhenaten’s death, Egypt gradually returned to its traditional polytheistic religion, partly because of how closely associated the Aten became with Akhenaten.[210] Atenism likely stayed dominant through the reigns of Akhenaten’s immediate successors, Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten, as well as early in the reign of Tutankhaten.[211] For some years the worship of Aten and a resurgent worship of Amun coexisted.[212][213]

Over time, however, Akhenaten’s successors, starting with Tutankhaten, took steps to distance themselves from Atenism. Tutankhaten and his wife Ankhesenpaaten dropped the Aten from their names and changed them to Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun, respectively. Amun was restored as the supreme deity. Tutankhamun reestablished the temples of the other gods, as the pharaoh propagated on his Restoration Stela: «He reorganized this land, restoring its customs to those of the time of Re. … He renewed the gods’ mansions and fashioned all their images. … He raised up their temples and created their statues. … When he had sought out the gods’ precincts which were in ruins in this land, he refounded them just as they had been since the time of the first primeval age.»[214] Additionally, Tutankhamun’s building projects at Thebes and Karnak used talatat’s from Akhenaten’s buildings, which implies that Tutankhamun might have started to demolish temples dedicated to the Aten. Aten temples continued to be torn down under Ay and Horemheb, Tutankhamun’s successors and the last pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Horemheb might also have ordered the demolition of Akhetaten, Akhenaten’s capital city.[215] Further underlining the break with Aten worship, Horemheb claimed to have been chosen to rule by the god Horus. Finally, Seti I, the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, ordered the name of Amun to be restored on inscriptions where it had been removed or replaced by Aten.[216]

Artistic depictions

Akhenaten in the typical Amarna period style.

Styles of art that flourished during the reigns of Akhenaten and his immediate successors, known as Amarna art, are markedly different from the traditional art of ancient Egypt. Representations are more realistic, expressionistic, and naturalistic,[217][218] especially in depictions of animals, plants and people, and convey more action and movement for both non-royal and royal individuals than the traditionally static representations. In traditional art, a pharaoh’s divine nature was expressed by repose, even immobility.[219][220][221]

The portrayals of Akhenaten himself greatly differ from the depictions of other pharaohs. Traditionally, the portrayal of pharaohs—and the Egyptian ruling class—was idealized, and they were shown in «stereotypically ‘beautiful’ fashion» as youthful and athletic.[222] However, Akhenaten’s portrayals are unconventional and «unflattering» with a sagging stomach; broad hips; thin legs; thick thighs; large, «almost feminine breasts;» a thin, «exaggeratedly long face;» and thick lips.[223]

Based on Akhenaten’s and his family’s unusual artistic representations, including potential depictions of gynecomastia and androgyny, some have argued that the pharaoh and his family have either suffered from aromatase excess syndrome and sagittal craniosynostosis syndrome, or Antley–Bixler syndrome.[224] In 2010, results published from genetic studies on Akhenaten’s purported mummy did not find signs of gynecomastia or Antley-Bixler syndrome,[21] although these results have since been questioned.[225]

Arguing instead for a symbolic interpretation, Dominic Montserrat in Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt states that «there is now a broad consensus among Egyptologists that the exaggerated forms of Akhenaten’s physical portrayal… are not to be read literally».[209][226] Because the god Aten was referred to as «the mother and father of all humankind,» Montserrat and others suggest that Akhenaten was made to look androgynous in artwork as a symbol of the androgyny of the Aten.[227] This required «a symbolic gathering of all the attributes of the creator god into the physical body of the king himself», which will «display on earth the Aten’s multiple life-giving functions».[226] Akhenaten claimed the title «The Unique One of Re», and he may have directed his artists to contrast him with the common people through a radical departure from the idealized traditional pharaoh image.[226]

Depictions of other members of the court, especially members of the royal family, are also exaggerated, stylized, and overall different from traditional art.[219] Significantly, and for the only time in the history of Egyptian royal art, the pharaoh’s family life is depicted: the royal family is shown mid-action in relaxed, casual, and intimate situations, taking part in decidedly naturalistic activities, showing affection for each other, such as holding hands and kissing.[228][229][230][231]

Small statue of Akhenaten wearing the Egyptian Blue Crown of War

Nefertiti also appears, both beside the king and alone, or with her daughters, in actions usually reserved for a pharaoh, such as «smiting the enemy,» a traditional depiction of male pharaohs.[232] This suggests that she enjoyed unusual status for a queen. Early artistic representations of her tend to be indistinguishable from her husband’s except by her regalia, but soon after the move to the new capital, Nefertiti begins to be depicted with features specific to her. Questions remain whether the beauty of Nefertiti is portraiture or idealism.[233]

Speculative theories

Sculptor’s trial piece of Akhenaten.

Akhenaten’s status as a religious revolutionary has led to much speculation, ranging from scholarly hypotheses to non-academic fringe theories. Although some believe the religion he introduced was mostly monotheistic, many others see Akhenaten as a practitioner of an Aten monolatry,[234] as he did not actively deny the existence of other gods; he simply refrained from worshiping any but the Aten.

Akhenaten and monotheism in Abrahamic religions

The idea that Akhenaten was the pioneer of a monotheistic religion that later became Judaism has been considered by various scholars.[235][236][237][238][239] One of the first to mention this was Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, in his book Moses and Monotheism.[235] Basing his arguments on his belief that the Exodus story was historical, Freud argued that Moses had been an Atenist priest who was forced to leave Egypt with his followers after Akhenaten’s death. Freud argued that Akhenaten was striving to promote monotheism, something that the biblical Moses was able to achieve.[235] Following the publication of his book, the concept entered popular consciousness and serious research.[240][241]

Freud commented on the connection between Adonai, the Egyptian Aten and the Syrian divine name of Adonis as stemming from a common root;[235] in this he was following the argument of Egyptologist Arthur Weigall. Jan Assmann’s opinion is that ‘Aten’ and ‘Adonai’ are not linguistically related.[242]

There are strong similarities between Akhenaten’s Great Hymn to the Aten and the Biblical Psalm 104, but there is debate as to relationship implied by this similarity.[243][244]

Others have likened some aspects of Akhenaten’s relationship with the Aten to the relationship, in Christian tradition, between Jesus Christ and God, particularly interpretations that emphasize a more monotheistic interpretation of Atenism than a henotheistic one. Donald B. Redford has noted that some have viewed Akhenaten as a harbinger of Jesus. «After all, Akhenaten did call himself the son of the sole god: ‘Thine only son that came forth from thy body’.»[245] James Henry Breasted likened him to Jesus,[246] Arthur Weigall saw him as a failed precursor of Christ and Thomas Mann saw him «as right on the way and yet not the right one for the way».[247]

Although scholars like Brian Fagan (2015) and Robert Alter (2018) have re-opened the debate, in 1997, Redford concluded:

Before much of the archaeological evidence from Thebes and from Tell el-Amarna became available, wishful thinking sometimes turned Akhenaten into a humane teacher of the true God, a mentor of Moses, a christlike figure, a philosopher before his time. But these imaginary creatures are now fading away as the historical reality gradually emerges. There is little or no evidence to support the notion that Akhenaten was a progenitor of the full-blown monotheism that we find in the Bible. The monotheism of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament had its own separate development—one that began more than half a millennium after the pharaoh’s death.[248]

Possible illness

Hieratic inscription on a pottery fragment. It records year 17 of Akhenaten’s reign and reference to wine of the house of Aten. From Amarna, Egypt. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

Limestone trial piece of a king, probably Akhenaten, and a smaller head of uncertain gender. From Amarna, Egypt – 18th Dynasty. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, London

The unconventional portrayals of Akhenaten—different from the traditional athletic norm in the portrayal of pharaohs—have led Egyptologists in the 19th and 20th centuries to suppose that Akhenaten suffered some kind of genetic abnormality.[223] Various illnesses have been put forward, with Frölich’s syndrome or Marfan syndrome being mentioned most commonly.[249]

Cyril Aldred,[250] following up earlier arguments of Grafton Elliot Smith[251] and James Strachey,[252] suggested that Akhenaten may have suffered from Frölich’s syndrome on the basis of his long jaw and his feminine appearance. However, this is unlikely, because this disorder results in sterility and Akhenaten is known to have fathered numerous children. His children are repeatedly portrayed through years of archaeological and iconographic evidence.[253]

Burridge[254] suggested that Akhenaten may have suffered from Marfan syndrome, which, unlike Frölich’s, does not result in mental impairment or sterility. Marfan sufferers tend towards tallness, with a long, thin face, elongated skull, overgrown ribs, a funnel or pigeon chest, a high curved or slightly cleft palate, and larger pelvis, with enlarged thighs and spindly calves, symptoms that appear in some depictions of Akhenaten.[255] Marfan syndrome is a dominant characteristic, which means sufferers have a 50% chance of passing it on to their children.[256] However, DNA tests on Tutankhamun in 2010 proved negative for Marfan syndrome.[257]

By the early 21st century, most Egyptologists argued that Akhenaten’s portrayals are not the results of a genetic or medical condition, but rather should be interpreted as stylized portrayals influenced by Atenism.[209][226] Akhenaten was made to look androgynous in artwork as a symbol of the androgyny of the Aten.[226]

Cultural depictions

Akhenaten’s life, accomplishments, and legacy have been preserved and depicted in many ways, and he has figured in works of both high and popular culture since his rediscovery in the 19th century AD. Akhenaten—alongside Cleopatra and Alexander the Great—is among the most often popularized and fictionalized ancient historical figures.[258]

On page, Amarna novels most often take one of two forms. They are either a Bildungsroman, focusing on Akhenaten’s psychological and moral growth as it relates to establishing Atenism and Akhetaten, as well as his struggles against the Theban Amun cult. Alternatively, his literary depictions focus on the aftermath of his reign and religion.[259] A dividing line also exists between depictions of Akhenaten from before the 1920s and since, when more and more archeological discoveries started to provide artists with material evidence about his life and times. Thus, before the 1920s, Akhenaten had appeared as «a ghost, a spectral figure» in art, while since he has become realistic, «material and tangible.»[260] Examples of the former include the romance novels In the Tombs of the Kings (1910) by Lilian Bagnall—the first appearance by Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti in fiction—and A Wife Out of Egypt (1913) and There Was a King in Egypt (1918) by Norma Lorimer. Examples of the latter include Akhnaton King of Egypt (1924) by Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Joseph and His Brothers (1933–1943) by Thomas Mann, Akhnaton (1973) by Agatha Christie, and Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth (1985) by Naguib Mahfouz. Akhenaten also appears in The Egyptian (1945) by Mika Waltari, which was adapted into the movie The Egyptian (1953). In this movie, Akhenaten, portrayed by Michael Wilding, appears to represent Jesus Christ and his followers proto-Christians.[261]

A sexualized image of Akhenaten, building on early Western interest in the pharaoh’s androgynous depictions, perceived potential homosexuality, and identification with Oedipal storytelling, also influenced modern works of art.[262] The two most notable portrayals are Akenaten (1975), an unfilmed screenplay by Derek Jarman, and Akhnaten (1984), an opera by Philip Glass.[263][264] Both were influenced by the unproven and scientifically unsupported theories of Immanuel Velikovsky, who equated Oedipus with Akhenaten,[265] although Glass specifically denies his personal belief in Velikovsky’s Oedpius theory, or caring about its historical validity, instead being drawn to its potential theatricality.[266]

In the 21st century, Akhenaten appeared as an antagonist in comic books and video games. For example, he is the major antagonist in limited comic-book series Marvel: The End (2003). In this series, Akhenaten is abducted by an alien order in the 14th century BC and reappears on modern Earth seeking to restore his kingdom. He is opposed by essentially all of the other superheroes and supervillains in the Marvel comic book universe and is eventually defeated by Thanos.[267] Additionally, Akhenaten appears as the enemy in the Assassin’s Creed Origins The Curse of the Pharaohs downloadable content (2017), and must be defeated to remove his curse on Thebes.[267] His afterlife takes the form of ‘Aten’, a location that draws heavily on the architecture of the city of Amarna.[268]

American death metal band Nile depicted Akhenaten’s judgement, punishment, and erasure from history at the hands of the pantheon that he replaced with Aten, in the song Cast Down the Heretic, from their 2005 album Annihilation of the Wicked.

Ancestry

See also

- Pharaoh of the Exodus

- Osarseph

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Cohen & Westbrook 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Rogers 1912, p. 252.

- ^ a b c d Britannica.com 2012.

- ^ a b c d e von Beckerath 1997, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Leprohon 2013, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b c Strouhal 2010, pp. 97–112.

- ^ a b c Duhig 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Dictionary.com 2008.

- ^ Montserrat 2003, pp. 105, 111.

- ^ Kitchen 2003, p. 486.

- ^ a b Tyldesley 2005.

- ^ Loprieno, Antonio (1995) Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,

- ^ Loprieno, Antonio (2001) “From Ancient Egyptian to Coptic” in Haspelmath, Martin et al. (eds.), Language Typology and Language Universals

- ^ a b Ridley 2019, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Hart 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Manniche 2010, p. ix.

- ^ Zaki 2008, p. 19.

- ^ Gardiner 1905, p. 11.

- ^ Trigger et al. 2001, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Hornung 1992, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Hawass et al. 2010.

- ^ Marchant 2011, pp. 404–06.

- ^ Lorenzen & Willerslev 2010.

- ^ Bickerstaffe 2010.

- ^ Spence 2011.

- ^ Sooke 2014.

- ^ Hessler 2017.

- ^ Silverman, Wegner & Wegner 2006, pp. 185–188.

- ^ Ridley 2019, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Dodson 2018, p. 6.

- ^ Laboury 2010, pp. 62, 224.

- ^ Ridley 2019, pp. 220.

- ^ Tyldesley 2006, p. 124.

- ^ Murnane 1995, pp. 9, 90–93, 210–211.

- ^ Grajetzki 2005.

- ^ Dodson 2012, p. 1.

- ^ Ridley 2019, p. 78.

- ^ Laboury 2010, pp. 314–322.

- ^ Dodson 2009, pp. 41–42.

- ^ University College London 2001.

- ^ Ridley 2019, p. 262.

- ^ Dodson 2018, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Dodson 2018, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Dodson 2009, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Ridley 2019, pp. 263–265.

- ^ a b Harris & Wente 1980, pp. 137–140.

- ^ Allen 2009, pp. 15–18.

- ^ Ridley 2019, p. 257.

- ^ Robins 1993, pp. 21–27.

- ^ Dodson 2018, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 154.

- ^ Redford 2013, p. 13.

- ^ Ridley 2019, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Redford 1984, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Hoffmeier 2015, p. 65.

- ^ Laboury 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Murnane 1995, p. 78.

- ^ Hoffmeier 2015, p. 64.

- ^ a b Aldred 1991, p. 259.

- ^ Reeves 2019, p. 77.