Генрих VIII входит не только в число самых знаменитых британских монархов, но ещё и в список 100 величайших британцев. Одним из главных итогов его почти 40-летнего правления стала, конечно же, английская Реформация. Приход Генриха к власти для большинства жителей королевства ознаменовал надежду на грядущие перемены: молодой, статный, просвещённый и амбициозный король выступал живым символом эпохи английского Возрождения. Однако с течением лет произошла неизбежная трансформация личности Генриха, и из живого, атлетического сложения юноши со «взором горящим» он превратился в тирана, параноика и деспота.

Генрих родился 28 июня 1491 года в Лондоне. Он стал вторым сыном и третьим ребёнком для короля Генриха VII и его жены Елизаветы Йоркской. Всего же у пары родились 7 детей, из которых 4 пережили младенчество и раннее детство. Старший брат Генриха, принц Артур, наследник престола, готовился к роли будущего короля отдельно от брата и сестёр, он проживал в собственной резиденции и имел свой двор. И хотя Генрих получил прекрасное образование, его воспитание отличалось от того, которое полагалось принцу Уэльскому (наследнику правящего монарха). Так, например, историки делают вывод, что письму Генриха обучала непосредственно мать — их почерк и написание отдельных букв схожи. С детства он был окружён любящими и внимательными женщинами, включая маму Елизавету Йоркскую, бабушку Маргарет Бофорт и сестёр Маргариту и Марию.

Детский портрет Генриха. (flickr.com)

Всё изменилось в 1502 году, когда, предположительно, от потницы умер 15-летний Артур. Наследником престола стал Генрих, и его отец сделал всё возможное, чтобы уберечь сына от любой потенциальной опасности. В частности, так любившему подвижные игры и спорт мальчику запретили участвовать в любых мало-мальски рискованных активностях. Встал вопрос и о помолвке Генриха с подходящей кандидаткой. Генрих VII рассматривал возможность женить сына на Екатерине Арагонской, вдове Артура, однако на протяжении долгого времени король пытался урегулировать вопрос получения второй части приданого, обещанного за испанской инфантой её родителями, Изабеллой Кастильской и Фердинандом Арагонским. Кроме того, необходимо было получить специальное разрешение на брак от Папы Римского, так как вдова брата считалась близкой родственницей. Сторона Екатерины утверждала, что союз не был консумирован, а потому обстоятельств, препятствующих браку, не имелось. В итоге понтифик выдал соответствующее разрешение. Тем не менее окончательно вопрос о женитьбе не был урегулирован до самой смерти Генриха VII в 1509 году.

Хотя правление Генриха VII ознаменовало собой период относительного спокойствия в государстве, его личность и персона всё же ассоциировалась с тяжелейшим для Англии периодом Войны Роз. Кроме того, после смерти Артура в 1502-м и кончины Елизаветы Йоркской в 1503-м Генрих VII впал в уныние, граничащее порой с отчаянием, о чём было хорошо известно его двору.

Первые шаги молодого короля

22 апреля 1509 года Генрих VIII был объявлен королём, это произошло на следующий день после кончины его отца. Уже 11 июня того же года состоялась свадьба Генриха и Екатерины Арагонской. Оба, и король, и королева, были популярны в народе. На молодого Генриха возлагали по-настоящему большие надежды: именно он, сын «белой принцессы» из рода Йорков, должен был принести королевству долгожданный мир, процветание и покой. И всё же Генрих понимал, что его положение не столь безопасно, как ему хотелось бы: при дворе Тюдоров находилось как минимум несколько кандидатов, которые в теории могли бы оспорить его право на трон. Впоследствии многие из них подвергнутся преследованиям, гонениям и даже будут казнены. В скором времени станет очевидно, что Генрих стремится окружить себя не столько людьми знатными, сколько полезными и талантливыми, и благородное происхождение уже не играет значительной роли.

Двор Генриха и Екатерины — гудящий, роскошный и яркий. В отличие от отца, прославившегося своим крохоборством и экономией, новый король не жалел средств: огромное количество придворных жило, его и пило за его счёт; министры и государственные мужи сколачивали себе состояния и с радостью пользовались щедростью монарха; его военные планы, в частности, строительство и расширение флота, требовали больших инвестиций. Генрих VII оставил сыну немало денег, но за почти 40 лет потрачено будет практически всё. Молодой король приглашал ко двору художников, музыкантов, поэтов, не скупился на увеселения и представления: его страсть к театральности была хорошо известна. Великолепные рыцарские турниры — ещё одна слабость Генриха, он и сам обожал принимать в них участие.

Генрих искал славы — военной прежде всего. Молодой король с готовностью пускался в авантюры, заключал союзы попеременно то с Францией против Испании, то наоборот. Турбулентными оставались и отношения с ближайшим соседом — Шотландией. Аппетиты Генриха к войне на протяжении первых двух десятилетий сдерживались кардиналом Томасом Уолси, одним из влиятельнейших людей того времени. Фактически именно Уолси решал многие вопросы как внешней, так и внутренней политики. Предпочитая дипломатию открытой вражде, Уолси склонял короля в сторону заключения мирных договоров в противовес объявлению войны. Генрих неоднократно использовал членов своей семьи в качестве политического инструмента: так, дочь Марию много раз сватали за наследников то французского, то испанского престолов; Марию Тюдор, младшую сестру, он выдал замуж за старого французского короля Людовика XII; связи жены Екатерины с Испанией пригодились в налаживании отношений с императором Карлом V.

Генрих и Екатерина. (flickr.com)

Одним из важнейших вопросов для Генриха было укрепление династии и рождение наследника. Их союз с Екатериной продлился около 20 лет, но сына король так и не дождался. В 1519 году на свет появился Генри Фицрой — бастард от связи с фрейлиной Бесси Блаунт. На тот момент у Генриха была лишь одна дочь — принцесса Мария. Именно отсутствие законных сыновей подтолкнуло его к разводу с первой женой. В середине 1520-х Генрих влюбился в Анну Болейн, которая на тот момент состояла в свите Екатерины Арагонской. Анна была на 20 лет моложе предшественницы и покорила Генриха своей прелестью, живым умом и энергией. Для женщины той эпохи Анна была великолепно образована, начитана и умна, кроме того, разделяла многие пристрастия короля — от охоты до азартных игр.

Развод, разрыв с Римом и череда жён

В 1529 году начался суд по делу о разводе с Екатериной Арагонской. Генрих ожидал получить разрешение на аннулирование брака от Папы Римского, аргументируя своё желание разойтись с супругой тем, что их союз с самого начала не мог считаться легитимным по причине консумации отношений между Екатериной и его братом Артуром (сама королева яростно отрицала это предположение). Когда Рим отказался признавать брак недействительным, Генрих поручил Томасу Уолси найти решение. Для Уолси это стало началом конца: не сумев обеспечить королю развод, он лишился состояния и могущества, был обвинён в измене и в итоге умер по дороге в Лондон, куда направлялся для допроса, после которого его, скорее всего, приговорили бы к казни.

«Великое дело короля», как называли развод с Екатериной, завершилось уже стараниями Томаса Кромвеля, бывшего секретаря Уолси и будущего государственного секретаря, и Томаса Кранмера, впоследствии назначенного на должность архиепископа Кентерберийского. Именно Кранмер убедил Генриха в том, что король отвечает непосредственно перед богом, а не перед папой, и потому решать подобные вопросы монарх мог самостоятельно, без оглядки на Рим. Всё это и привело к назначению Генриха главой новой церкви, церкви Англии, и ознаменовало разрыв с Римом и католичеством.

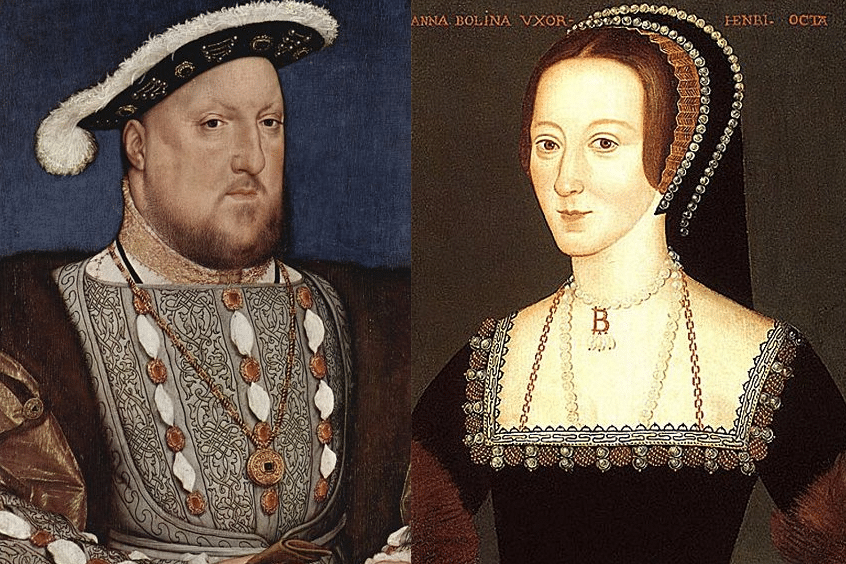

Генрих и Анна Болейн. (flickr.com)

В 1532-м Генрих тайно обвенчался с Анной Болейн, а 25 января 1533 года состоялась официальная церемония. Екатерина Арагонская была отправлена подальше от двора, её лишили права называться королевой, однако до самой смерти она так и не признавала факт аннулирования брака. 7 сентября 1533 года на свет появилась принцесса Елизавета. Первую дочь, Марию, вычеркнули из порядка престолонаследия и объявили незаконнорожденной. Отношения Анны и Генриха, до брака развивавшиеся в лучших традициях романтического рыцарского романа, стали стремительно ухудшаться после рождения Елизаветы. В последующие три года королева перенесла два выкидыша, чем невероятно разочаровала Генриха. Помимо прочего, он полагал активность супруги в политических и религиозных вопросах неприемлемой, а её семью — амбициозной и тщеславной, но главной «виной» Анны стала, конечно же, неспособность выносить наследника. В 1536 году её обвинили в измене, прелюбодеянии и инцесте и казнили. Меньше, чем через сутки после того, как палач отрубил Болейн голову, Генрих обручился с Джейн Сеймур.

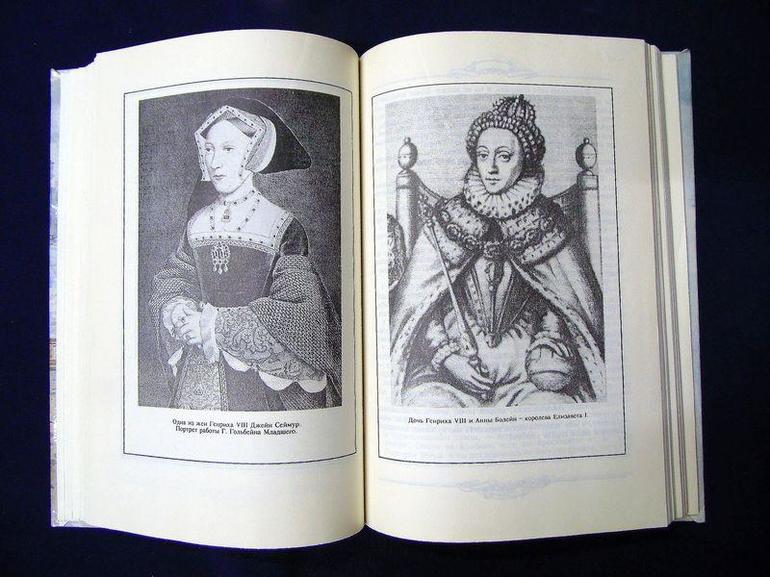

Третья супруга короля забеременела примерно через полгода после свадьбы, и в октябре 1537 года родила сына, которого назвали Эдуардом. Вне себя от радости, Генрих затеял празднования и торжества по случаю появления на свет такого долгожданного мальчика! Счастье вскоре омрачилось огромной печалью: Джейн скончалась спустя всего 12 дней после родов. Король заперся в своих покоях, отказывался принимать посетителей и участвовать в государственных делах. Впрочем, довольно скоро советники убедили Генриха в необходимости найти новую жену: одного наследника было недостаточно, монарху полагалось иметь сыновей «про запас» на случай смерти старшего сына.

Поисками кандидатки занимался Томас Кромвель, и его выбор пал на Анну, дочь Иоганна III, герцога Клевского. Кромвель настаивал на этом союзе, главным образом, по причине того, что Анна была лютеранкой, а укрепление связей с протестантским миром только способствовало бы продолжению дела Реформации. К тому же прочие европейские принцессы, к которым хотел свататься Генрих, не очень-то горели желанием вступать в брак со вспыльчивым, подозрительным и непредсказуемым королем, чьи жены «плохо кончали». Генрих отправил своего придворного художника Ганса Гольбейна Младшего написать портрет Анны, и, удовлетворённый увиденным, согласился на этот союз.

Генрих VIII и его шесть жён. (flickr.com)

Анна прибыла в Англию в конце декабря 1539-го, а уже в первый день 1540-го она увидела Генриха. Королю невеста не понравилась, по его словам, она ничуть не походила на свой портрет, однако отказываться было уже поздно. Свадьба состоялась 6 января 1540-го, но, судя по всему, союз так никогда и не был консумирован. Генрих сразу же поручил Кромвелю начать процедуру по аннулированию брака. Анна пробыла королевой-консортом около полугода, она приняла условия Генриха, согласилась на развод, чем невероятно осчастливила монарха, пожаловавшего ей имение, щедрое содержание и неофициальный титул «любимой сестры короля». Томас Кромвель, организовавший этот союз, впал в немилость и был заключён в тюрьму. Его обвинили в государственной измене и еретических взглядах и казнили.

Новой возлюбленной Генриха стала молоденькая Екатерина Говард. Он женился на ней практически сразу же после развода с Клевской. Екатерине на момент их свадьбы было, по разным подсчётам, от 15 до 20 лет. Близкие короля и придворные отмечали, что Говард как будто бы омолодила короля: он вновь почувствовал вкус к жизни, впервые после смерти Джейн Сеймур. Екатерина обожала танцы, балы, украшения, платья и увеселения. Король был щедр к девушке, дарил ей подарки и баловал сверх меры. Род Говардов был знатен, но семья Екатерины полагалась относительно небогатой. До появления при дворе она находилась на попечении Агнес Говард, вдовствующей герцогини Норфолк, толком ничему не обучалась, не умела писать и вела достаточно фривольный образ жизни для благородной девицы той поры. К роли королевы Екатерина была совсем не готова. Вскоре после свадьбы девушка заскучала: Генрих занимался государственными делами и всё чаще запирался в своих покоях из-за прогрессирующей болезни. При дворе поползли слухи о неверности пятой супруги короля, поговаривали о её добрачных связях с несколькими мужчинами. Генрих поручил провести расследование: выяснилось, что Говард не только имела любовника до встречи с королём, но и состояла в связи с одним из ближайших придворных монарха — Томасом Калпепером. 13 февраля 1542 года юную королеву казнили по обвинению в супружеской измене.

Джонатан Рис-Майерс в роли Генриха в «Тюдорах». (flickr.com)

Последней женой Генриха стала Екатерина Парр, дважды вдова, но всё ещё достаточно молодая, активная, невероятно просвещённая и прогрессивная для своего времени женщина. Парр была самой любимой мачехой как минимум для двоих детей Генриха: Елизаветы и Эдуарда. С принцессой Марией она тоже поддерживала тёплые отношения. Для короля Парр стала не только верной, терпеливой и разумной супругой, но также партнёром и другом. В то же время она не раз рисковала оказаться на волоске от гибели из-за своих чрезвычайно радикальных, по мнению Генриха, религиозных убеждений. Екатерина придерживалась протестантских взглядов и неоднократно заявляла о необходимости продолжения и углубления церковных реформ в Англии. Генрих, по сути, лишь номинально отказавшийся от католичества, такой подход не приветствовал. Был выписан ордер на арест королевы, однако Екатерина примирилась с мужем, заверив его, что ни в коем случае не ставила под сомнение мудрость и политику монарха.

Наследие Генриха VIII

К концу жизни Генрих страдал от множества заболеваний: его тело было покрыто нарывами и язвами, его мучила подагра, он с трудом передвигался из-за чрезмерной полноты, а старая рана на ноге, полученная во время турнира в 1536 году, постоянно нарывала и буквально сводила его с ума. Придворные врачи оказались неспособны облегчить его состояние. Он умер 28 января 1547 года, оставив после себя наследником малолетнего Эдуарда VI.

Чарльз Лоутон в фильме «Частная жизнь Генриха VIII». (flickr.com)

Генрих правил Англией 37 лет. В истории он известен как многоженец, порвавший с Римской католической церковью из-за любви к женщине. Разумеется, у английской Реформации были и другие, куда более глубокие предпосылки и причины: протестантские настроения к тому моменту уже завладели умами английской элиты, к тому же разрыв с Римом позволил Генриху стать одновременно проводником закона как светского, так и религиозного. Последующее за Реформацией разорение католических монастырей и аббатств обогатило казну, однако значительных денежных средств в наследство сыну монарх не оставил: траты превышали расходы. И хотя осторожные реформы Генриха носили во многом номинальный характер, его великое начинание впоследствии было продолжено сыном Эдуардом и дочерью Елизаветой.

При Генрихе был расширен и укреплён английский флот: это также стало отправной точкой для будущих свершений Англии на морях, освоения новых территорий и участия державы в Великих географических открытиях. Король покровительствовал искусствам, привечал и талантливых художников, музыкантов, поэтов и архитекторов. В эпоху правления Генриха было построено и восстановлено значительное количество замков и поместий (немало было, впрочем, и уничтожено, преимущественно, религиозных строений).

О себе Генрих любил думать, прежде всего, как о гуманисте, истинном воплощении правителя эпохи Возрождения. Именно таким его видели и непосредственные потомки, в особенности Эдуард и Елизавета, с гордостью позиционировавшие себя наследниками и продолжателями дела великого отца. Необходимо помнить, что Генрих последних примерно 10 лет жизни мало напоминал самого себя в юности и молодости: необратимое превращение в тирана и деспота началось приблизительно в 1536 году, когда была казнена Анна Болейн. Оценка его личности с исторической точки зрения неоднократно менялась с течением времени, и современные исследователи смотрят на Генриха как на невероятно сложную, противоречивую, многогранную фигуру, оставившую после себя такой спорный, но, несомненно, местами грандиозный след.

Генрих VIII — биография

Генрих VIII – король Англии, унаследовавший престол от отца – Генриха VII. Второй монарх из династии Тюдор. Принимал прямое участие в Английской Реформации, отлучен от католической церкви, женат шесть раз.

О короле Англии Генрихе VIII написано уже очень много, но это отнюдь не уменьшает интерес к его персоне. Его действия – противоречивые и достаточно причудливые, основывались на политических и личных мотивах, в нем видели то короля-жуира, которого вообще не интересовали государственные дела, то жестокого и вероломного тирана, расчетливого политика, устраивавшего свою личную жизнь исключительно мотивируясь политическими мотивами. Единственно, в чем мнения всех писавших о нем совпадают, это деспотизм короля. Как в одном человеке сочетался тиран и благородный рыцарь, непонятно, но Генрих действительно обладал трезвым расчетом, способствующим укрепить его власть.

Детство

Родился Генрих VIII в Гринвиче 28 июня 1491 года. Его отец — Генрих VII, король Англии, мать – Елизавета Йоркская. Мальчик стал третьим по счету ребенком в королевской семье. Воспитывала Генриха родная бабушка – леди Маргарет Бофорт. Отец постепенно подготавливал сына к тому, что ему необходимо будет принять духовный сан, а бабушка водила его на мессы, иногда по шесть раз в день. Генриху часто доводилось писать сочинения на темы богословия, заниматься изучением Библии.

После смерти старшего брата Артура, первого претендента на трон, у Генриха появился шанс занять престол. Теперь он стал принцем Уэльским и начал активную подготовку к коронации.

Генрих VII прилагал много усилий для расширения влияния Англии и укрепления дружеских отношений с соседними государствами. По его настоянию младший сын взял в жены Екатерину Арагонскую, вдову умершего брата. Ее предки – основатели Испанского государства. История не сохранила документальных подтверждений того, как Генрих VIII всеми силами пытался избежать этого брака, но он решительно не хотел жениться на вдове.

Правление

После смерти Генриха VII в 1509 году, семнадцатилетний наследник престола взошел на трон. На протяжении первых двух лет его правления все государственные дела вели Уильям Уорхэм и Ричард Фокс. После них непосредственное управление страной принял на себя кардинал Томас Уосли, которого впоследствии возвели в титул лорда-канцлера Англии. Молодой король пока не мог управлять государственными делами, поэтому на период его взросления, реальную власть осуществляли опытные помощники. Они «достались» Генриху VIII от отца, ведь именно в годы его правления решали важные вопросы в стране.

Первая победа в славной биографии Генриха VIII случилась в 1512 году, когда он во главе своего флота отбыл к французским берегам. Английское войско под его командованием разгромило французов и победно вернулось на родину.

Военные действия по отношению к Франции велись вплоть до 1525 года. Успех попеременно был то на одной, то на второй стороне. Генрих VIII со своим войском сумел дойти до Парижа, но в связи с отсутствием средств в военной казне, дальше не продвинулся и заключил перемирие. Сам король зачастую бывал непосредственно на поле сражения. Он искусно стрелял из лука, и приказал всем своим подданным раз в неделю выделять один час на занятия по стрельбе из лука.

Внутреннюю политику короля вряд ли можно назвать идеальной. Указы, издаваемые Генрихом VIII, приводили мелких крестьян к полному разорению. Результатом таких необдуманных действий правителя стало появление в стране десятков тысяч бродяг. Для решения этой проблемы король не придумал другого выхода, как издать указ о наказании за бродяжничество. В результате тысячи бродяг, имевших до этого свое крестьянское хозяйство, были казнены через повешение.

Самый значимый вклад в историю развития Англии Генрих VIII сделал благодаря церковной реформе. Католическая церковь категорически не соглашалась на развод монарха с первой женой, поэтому Генрих VIII пошел на разрыв отношений с папством. Затем король предъявил Клименту VII обвинение в измене.

На должность Архиепископа Кентерберийского король назначил Томаса Кранмера, а тот в свою очередь признал недействительным брак монарха и вдовы его старшего брата. Генриху VIII не терпелось получить этот развод, так как он страстно желал жениться на Анне Болейн. Далее король принялся за полное искоренение римской церкви в Англии, добился закрытия всех соборов, храмов и церквей. Имущество, ранее принадлежавшее римской церкви, перешло государству, были казнены все священники и проповедники. Все Библии, напечатанные на других языках, кроме английского, сожгли. Король приказал вскрыть и разграбить могилы всех святых.

В 1540-м был казнен Томас Кромвель, главный помощник Генриха VIII в проведении всех реформ. После этого король снова вернулся в католическую веру и опубликовал «Акт о шести статьях». Парламент Англии полностью поддержал этот документ. Этим актом всем жителям страны предписывалось нести дары на мессу, исповедоваться и причащаться. Духовным служителям следовало принять обет безбрачия, и строго следить за соблюдением других монашеских обетов. Все, кто высказал свое несогласие с этим актом, были казнены, как изменники.

После казни пятой жены-католички, Генрих VIII принял решение об изменении церковной веры в королевстве. Вынес запрет на проведение католических обрядов, вернулся к протестантским. Реформы, проведенные за годы правления Генриха VIII, отличались нелогичностью и непоследовательностью, но зато Английская церковь обрела независимость от Рима.

К концу своего правления английский король поражал всех своей безжалостностью. Историки утверждают, что он страдал генетическим заболеванием, оказавшим большое влияние на состояние его психики. У него проявились такие черты характера, как вспыльчивость, мнительность, жестокость. Все, кто чем-то не угодил королю, были казнены.

Личная жизнь

Генрих VIII вошел в историю, как король-многоженец. У него было шесть официальных жен. Первая – Екатерина Аргонская, вдова старшего брата Артура. На ней он женился по настоянию отца, а вскоре добился развода. Он мотивировал свое желание развестись с Екатериной тем, что она не могла дать ему наследника. Все дети умирали буквально в первые дни после рождения. Выжила только одна дочь короля — Мария, а ему нужен был наследник. В 1553-м именно Мария заняла королевский престол Англии и осталась в истории страны как Мария Кровавая.

Второй раз Генрих VIII женился на Анне Болейн. Вначале король предлагал ей только романтические отношения, но в любовницах девушка ходить не собиралась. Именно это подтолкнуло короля на развод с Екатериной. Анне удалось внушить королю мнение, что он должен служить себе и короне, а что о нем думают римские священнослужители, это не должно его волновать. И Генрих VIII принялся рьяно проводить реформы.

В 1533-м Генрих официально женился на Анне Болейн. В том же году ее короновали. Через 9 месяцев после свадьбы родилась их дочь – Елизавета. Анна предпринимала много попыток родить королю сына, но после этого не смогла выносить ни одного ребенка. Пропасть между супругами с каждой новой попыткой рождения ребенка увеличивалась. В итоге, Генрих VIII обвинил супругу в измене, и ее казнили в 1536 году. Анну обезглавили.

После этого он женился на фрейлине покойной жены – Джейн Сеймур, причем сыграл свадьбу всего через неделю после того, как по его приказу Анне отрубили голову. В браке с Джейн родился долгожданный наследник. Сын Эдуард родился в 1537 году, а сама Джейн вскоре умерла. Причина – родовые осложнения.

Четвертый брак король заключил исключительно из политических убеждений. Его женой стала Анна Клевская, дочь Иоганна III Клевского, немецкого герцога. Генрих очень хотел до брака увидеть, как выглядит его будущая супруга, потому заказал, чтобы написали ее портрет.

Изображение молодой девушки пришлось ему по вкусу, и монарх решился на очередной брак. Но после встречи Генрих VIII разочаровался во внешности невесты, и приложил максимум усилий, чтобы скорее расстаться с ней. В 1540-м этот брак признали недействительным, так как до этого девушка уже была помолвлена с другим. Быстро нашли и виновника неудачного брака короля. Вину возложили на Томаса Кромвеля и вскоре его казнили.

В том же 1540-м году Генрих снова предпринял попытку устроить свою личную жизнь. На этот раз его избранницей стала сестра Анны Болейн, Екатерина Говард. Король был в нее влюблен, он и не подозревал, что у нее были романтические отношения с другим мужчиной. Она продолжала изменять королю и после бракосочетания. Ее любовником стал паж Генриха VIII. Когда король обо всем узнал, то велел казнить и жену и всех ее любовников в 1542 году.

Последней женщиной, которую монарх повел под венец, стала Екатерина Парр. До брака с Генрихом VIII она уже дважды побывала замужем, и оба раза оставалась вдовой. Женщина придерживалась протестантской веры, и сумела склонить супруга принять протестантство. После того, как Генрих умер, она выходила замуж еще два раза.

Смерть

У английского короля доктора обнаружили с десяток заболеваний. Но больше всего он страдал от ожирения. Передвигался монарх с трудом, объем его талии превышал полтора метра. Чтобы хоть как-то ходить, ему понадобились специальные устройства.

Генрих был страстным охотником, и однажды сильно травмировал ногу. Докторам удалось залечить травму, но они же и занесли в рану инфекцию. Рана постепенно увеличивалась и не заживала.

Доктора ничем не могли помочь, они объявили о смертельной болезни короля. Рана стала гноиться, чем доставляла королю не только физические, но и моральные страдания. Он постоянно пребывал в плохом настроении, все чаще проявлял свой деспотизм по отношению к окружающим.

Монарх приказал изменить ему рацион питания. Не ел овощей и фруктов, питался исключительно красным мясом. Доктора пришли к выводу, что именно это обстоятельство привело Генриха VIII к смерти 28 января 1547 года.

Память о самом кровавом короле Англии за всю ее историю сохранилась в книгах и фильмах, его статуя украшает госпиталь Святого Варфоломея.

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Краткая биография

Биография Генриха 8 Тюдора началась в Гринвиче (ныне Лондон). Дата его рождения — 28 июня 1491 года. Он был третьим ребенком английского короля Генриха VII и Елизаветы Йоркской. По желанию отца мальчик должен был принять духовный сан.

Внезапная смерть старшего брата в 1502 изменила судьбу Генриха — он стал главным претендентом на трон. Кроме того, по настоянию отца юноша женился на вдове брата Екатерине Арагонской ради союза с Испанией.

Генрих VII скончался в апреле 1509 года, когда наследнику исполнилось всего 17 лет. Первые 2 года государством управляли епископ Винчестерский и архиепископ Кентерберийский. Затем власть перешла кардиналу Томасу Уолси, а после его смерти — к Томасу Кромвелю.

В 1536 году Генрих VIII повредил из-за несчастного случая ногу. Рана загрязнилась и начала гнить. Врачи разводили руками — рана была трудной, а по мнению некоторых, и вовсе не излечимой. Из-за этого королю пришлось значительно снизить физические нагрузки и сменить рацион на более жирный и обильный. Появились первые приступы депрессии, в характере начали преобладать тиранические черты.

К концу жизни Генрих страдал от сильного ожирения и едва мог самостоятельно передвигаться. Его тело было покрыто опухолями, возможно, развилась подагра. Все это привело к быстрой кончине. Генрих Тюдор умер в возрасте 55 лет 28 января 1547 года.

Внешняя и внутренняя политика

Политика короля была крайне деспотичной, особенной жестокостью отличилась вторая половина правления. В это время были казнены многие политические противники монарха, последним стал Генри Говард, поэт и сын герцога Норфолка. Он умер за несколько дней до смерти короля. Впрочем, исчерпывающую характеристику предоставляет тот факт, что во время его правления были казнены около 72 тысяч человек и 2 супруги.

Краткий перечень внешнеполитической деятельности императора:

- В 1512 году молодой Генрих впервые отправился во главе флота против Франции. Поход увенчался успехом.

- В 1513 он отправился во 2 поход против того же врага. Сперва Англии удалось захватить 2 городка, но война на этом не закончилась. Следующие 12 лет разорительная война против Франции шла с попеременным успехом, а армия даже подошла к Парижу. Но уже в 1525 казна опустела окончательно, и монарху пришлось пойти на мировую.

Важнейшей реформой Генриха 8 стало отделение церкви и разрыв с Папой римским. Это произошло в 1529 году, когда королю необходимо было признать заключенный брак незаконным. Папа Климент VII не принял развод, из-за чего Генрих решил порвать с ним.

Хронология событий:

- В 1532 епископы Англии были обвинены в измене. Статья была выбрана «мертвая» (по ней никого до этого не судили) — обращению для принятия решения к правителю чужого государства (Папе), а не к своему монарху. Парламент вовсе запретил обращатсья к Папе для решения вопросов внутри государства. Новым архиепископом Кентерберийским стал Томас Крамер, который должен был обосновать порядок проведения развода.

- В ответ на подобную наглость Генрих был отлучен от Церкви.

- На следующий год Парламент назначил короля Главой новой Церкви Великобритании.

- В 1535—1539 годах произошла масштабная секуляризация земель монастырей, из-за чего они утратили экономическое преимущество. Были закрыты все монастыри — их имущество конфисковано, сами территории разграблены, а святые мощи осквернены. Лица, выступавшие против подобных реформ, оказались на эшафоте.

Впрочем, уже в 1540 году Генрих VIII вновь обратился к католицизму. Причинами стали неудачный брак с протестанткой и казнь отвечавшего за реформы Томаса Кромвеля. После казни 5 жены-католички и под влиянием последней супруги-протестантки король вновь сменил убеждения. И хотя действия монарха были непоследовательными и противоречивыми, в его правление была создана независимая английская Церковь.

Дела семейные

Генрих VIII был женат 6 раз. Большое количество браков связаны не только с любвеобильностью монарха, но и с его желанием иметь наследника. Интересный факт — английские школьники заучивают итоги браков Генриха 8 Тюдора и его жен по фразе: «развелся — казнил — умерла — развелся — казнил — пережила».

Список жен следующий:

- Екатерина Арагонская (1485−1536), дочь испанского короля. Была выдана замуж за старшего брата Генриха, который вскоре умер. Генрих женился на ней только в 1509 году, когда вступил на престол. К сожалению, супруги долго не могли завести детей — те либо рождались мертвыми, либо умирали в раннем возрасте. Выжила только дочь Мария. Это привело к желанию Генриха развестись, так как королю нужен был наследник. Бракоразводный процесс, начатый в 1525 году, растянулся на долгие годы — Папа Климент VII не мог принять окончательного решения. В результате в 1532 парламент запретит апелляции решения в Риме, а в начале следующего года архиепископ Кентерберийский объявил об аннулировании брака. Последние годы жизни жена провела в ссылке.

- Анна Болейн (1507−1536). Долгое время отказывалась становиться любовницей влюбленного короля. Когда бракоразводный процесс зашел в тупик, Анна наняла богословов, которые доказали, что король ответственен не перед Папой римским, а непосредственно перед Богом. Это послужило началом отсоединения английской церкви. Свадьба с Генрихом произошла в январе 1533, через 9 месяцев королева родила дочь Елизавету. После этого она дважды рожала сыновей, но оба не прожили и года. Через 3 года отношения испортились окончательно. Анна была обвинена в супружеской измене и казнена.

- Джейн Сеймур (1508−1537). Фрейлина Анны Болейн, ставшая королевой всего через неделю после смерти последней. Родила сына Эдуарда VI, но вскоре он скончалась от родильной горячки.

- Анна Клевская (1515−1557). Дочь герцога Клевского. Брак был политическим, направленным на укрепление союза. Несмотря на то что Генрих заранее видел портрет невесты, она сама ему не понравилась. Свадьбу сыграли в начале 1540 года, после чего король сразу же начал искать способы избавиться от супруги. Через полгода повод был найден — Анна была ранее помолвлена с герцогом Лотарингским, кроме того, супруги не спали вместе. Анна осталась при дворе и пережила неудавшегося супруга.

- Екатерина Говард (1520−1542). Двоюродная сестра Анны Болейн вскружила голову королю — брак был заключен через месяц после последнего развода. Однако вскоре выяснилось, что молодая жена имела любовников до свадьбы и изменяет мужу с его же пажом. Последнего и саму Екатерину казнили в феврале 1542.

- Екатерина Парр (1512−1548). Брак был заключен в 1543 году, когда Екатерина уже дважды овдовела. Благодаря ее влиянию, Генрих 8 обратился к протестантизму. После смерти мужа она вышла замуж за брата Джейн Сеймур.

Кроме того, король имел немало связей на стороне. Самой известной стали отношения с Элизабет Блаунт, ребенок которой стал единственным признанным бастардом.

Дети и наследники

У короля было немало детей как рожденных в браках, так и незаконнорожденных. Примечательно, что бастарды в основном прожили долгие жизни.

В браках родилось 10 детей, из них только трое пережили младенческий возраст:

- Мария I или Кровавая (1516−1558), дочь Екатерины Арагонской. Правила после Эдуарда VII с 1553 и стала первой коронованной королевой Англии и Ирландии. Она правила всего 4 года и умерла из-за охватившей страну лихорадки. Примечательно, что, будучи при смерти, королева успела составить завещание, в котором отказала своему супругу в каком-либо праве на английский трон.

- Елизавета I или Королева-дева (1533−1603), дочь Анны Болейн. Взошла на трон при поддержке знати вскоре после смерти сестры в конце 1558. Она находилась у власти почти 45 лет и стала последней представительницей рода Тюдоров. После ее кончины трон перешел династии Стюартов.

- Эдуард VI (1537−1553), сын Джейн Сеймур. Вступил на престол после смерти отца в 1547. Из-за молодого возраста (королю было всего 9 лет) находился под опекой дяди, после опалы последнего началось соперничество регентов. В 16 лет умер от пневмонии или туберкулеза. Наследником король назначил правнучку Генриха VII, однако народ не принял новую королеву. Всего через 10 дней она с семьей была арестована по обвинению в измене. Трон перешел к Марии.

Стоит отметить и самого известного внебрачного ребенка Генриха VIII, официально признанного им — Генри Фицроя. Мальчик долгое время считался претендентом на трон, но ребенок умер за год до рождения Эдуарда.

Интересные факты

Несмотря на то что Генрих VIII в основном известен многоженством и развитием протестантизма, о нем известны и другие интересные факты. Они относятся к разным сторонам жизни английского короля.

Малоизвестными фактами являются следующие:

- Генрих был отличным лучником и издал указ, согласно которому каждый англичанин должен был еженедельно по субботам посвящать час тренировкам в стрельбе.

- Монарх прекрасно говорил на 3 языках и хорошо разбирался в разных науках.

- Король получил отличное музыкальное образование — он пел и играл на нескольких музыкальных инструментах. Его перу принадлежало минимум 2 мессы и популярная в то время в народе песня «Pastime with Good Company» («Досуг в хорошем обществе») или «Баллада короля». По одной из версий он также написал в честь Анны Болейн балладу «Зеленые рукава».

- До 1541 года носил титул «Правитель Ирландии», затем ирландский парламент наделил правителя титулом «Король Ирландии».

- В молодости Генрих пользовался большим успехом у дам благодаря своей эффектной внешности — высокий (около 190 см), в хорошей спортивной форме, с густыми волосами и выбритым лицом. Из-за травмы ноги король был вынужден сменить активный образ жизни на сидячей, что привело к набору веса. Под конец жизни его талия составляла более 130 см. Представить его габариты можно по сохранившемуся доспеху.

- В последние годы король съедал до 5 тысяч калорий в день. Его рацион состоял из огромного количества жирного мяса (баранины, свинины, оленины и птицы) и алкоголя (красного вина и эля). Из-за большого веса и значительных габаритов монарх не мог самостоятельно передвигаться — ему приходилось использовать специальные механизмы.

- Его перу принадлежит книга «Защита 7 таинств» — ответ на «95 тезисов» Мартина Лютера. За эту книгу в 1521 году Папа присвоил Генриху титул «Защитник веры».

- Несмотря на то что на картинах король часто изображен с бородой, он ввел налог на ее ношение, из-за чего растительность на лице стала символом статуса и богатства. Платить должны были все люди, сумма же варьировалась в зависимости от социального статуса человека.

- В память о Генрихе Тюдоре в 2009 году была выпущена памятная монета в 5 фунтов. Она была посвящена 500-летию со дня его восхождения на престол.

Правление Генриха 8 насчитывает почти 40 лет, однако это время сложно назвать впечатляющим или плодотворным. Больше всего он известен сегодня как многоженец (у него было 6 жен) и создатель отдельной от Рима Церкви, которая подчинялась королю.

| Henry VIII | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Henry VIII after Hans Holbein the Younger, c. 1537–1562 |

|

| King of England Lord/King of Ireland (more…) |

|

| Reign | 22 April 1509 – 28 January 1547 |

| Coronation | 24 June 1509 |

| Predecessor | Henry VII |

| Successor | Edward VI |

| Born | 28 June 1491 Palace of Placentia, Greenwich, England |

| Died | 28 January 1547 (aged 55) Palace of Whitehall, Westminster, England |

| Burial | 16 February 1547

St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, Berkshire |

| Spouses |

Catherine of Aragon (m. ; ann. ) Anne Boleyn (m. ; ann. ) Jane Seymour (m. ; d. ) Anne of Cleves (m. ; ann. ) Catherine Howard (m. ; d. ) Catherine Parr (m. ) |

| Issue Among others |

|

| House | Tudor |

| Father | Henry VII of England |

| Mother | Elizabeth of York |

| Religion |

|

| Signature |

Henry VIII (28 June 1491 – 28 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement with Pope Clement VII about such an annulment led Henry to initiate the English Reformation, separating the Church of England from papal authority. He appointed himself Supreme Head of the Church of England and dissolved convents and monasteries, for which he was excommunicated by the pope. Henry is also known as «the father of the Royal Navy» as he invested heavily in the navy and increased its size from a few to more than 50 ships, and established the Navy Board.[1]

Domestically, Henry is known for his radical changes to the English Constitution, ushering in the theory of the divine right of kings in opposition to papal supremacy. He also greatly expanded royal power during his reign. He frequently used charges of treason and heresy to quell dissent, and those accused were often executed without a formal trial by means of bills of attainder. He achieved many of his political aims through the work of his chief ministers, some of whom were banished or executed when they fell out of his favour. Thomas Wolsey, Thomas More, Thomas Cromwell, Richard Rich and Thomas Cranmer all figured prominently in his administration.

Henry was an extravagant spender, using the proceeds from the dissolution of the monasteries and acts of the Reformation Parliament. He also converted the money that was formerly paid to Rome into royal revenue. Despite the money from these sources, he was continually on the verge of financial ruin due to his personal extravagance, as well as his numerous costly and largely unsuccessful wars, particularly with King Francis I of France, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, King James V of Scotland and the Scottish regency under the Earl of Arran and Mary of Guise. At home, he oversaw the annexure of Wales to England with the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542 and was the first English monarch to rule as King of Ireland following the Crown of Ireland Act 1542.

Henry’s contemporaries considered him to be an attractive, educated and accomplished king. He has been described as «one of the most charismatic rulers to sit on the English throne» and his reign has been described as the «most important» in English history.[2][3] He was an author and composer. As he aged, he became severely overweight and his health suffered. He is frequently characterised in his later life as a lustful, egotistical, paranoid and tyrannical monarch.[4] He was succeeded by his son Edward VI.

Early years

Born on 28 June 1491 at the Palace of Placentia in Greenwich, Kent, Henry Tudor was the third child and second son of King Henry VII and Elizabeth of York.[5] Of the young Henry’s six (or seven) siblings, only three – his brother Arthur, Prince of Wales, and sisters Margaret and Mary – survived infancy.[6] He was baptised by Richard Foxe, the Bishop of Exeter, at a church of the Observant Franciscans close to the palace.[7] In 1493, at the age of two, Henry was appointed Constable of Dover Castle and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. He was subsequently appointed Earl Marshal of England and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland at age three and was made a Knight of the Bath soon after. The day after the ceremony, he was created Duke of York and a month or so later made Warden of the Scottish Marches. In May 1495, he was appointed to the Order of the Garter. The reason for giving such appointments to a small child was to enable his father to retain personal control of lucrative positions and not share them with established families.[7] Not much is known about Henry’s early life – save for his appointments – because he was not expected to become king,[7] but it is known that he received a first-rate education from leading tutors. He became fluent in Latin and French and learned at least some Italian.[8][9]

In November 1501, Henry played a considerable part in the ceremonies surrounding his brother Arthur’s marriage to Catherine, the youngest child of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile.[10] As Duke of York, Henry used the arms of his father as king, differenced by a label of three points ermine. He was further honoured on 9 February 1506 by Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, who made him a Knight of the Golden Fleece.[11]

In 1502, Arthur died at the age of 15, possibly of sweating sickness,[12] just 20 weeks after his marriage to Catherine.[13] Arthur’s death thrust all his duties upon his younger brother. The 10-year-old Henry became the new Duke of Cornwall, and the new Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester in February 1504.[14] Henry VII gave his second son few responsibilities even after the death of Arthur. Young Henry was strictly supervised and did not appear in public. As a result, he ascended the throne «untrained in the exacting art of kingship».[15]

Henry VII renewed his efforts to seal a marital alliance between England and Spain, by offering his son Henry in marriage to the widowed Catherine.[13] Both Henry VII and Catherine’s mother Queen Isabella were keen on the idea, which had arisen very shortly after Arthur’s death.[16] On 23 June 1503, a treaty was signed for their marriage, and they were betrothed two days later.[17] A papal dispensation was only needed for the «impediment of public honesty» if the marriage had not been consummated as Catherine and her duenna claimed, but Henry VII and the Spanish ambassador set out instead to obtain a dispensation for «affinity», which took account of the possibility of consummation.[17] Cohabitation was not possible because Henry was too young.[16] Isabella’s death in 1504, and the ensuing problems of succession in Castile, complicated matters. Catherine’s father Ferdinand preferred her to stay in England, but Henry VII’s relations with Ferdinand had deteriorated.[18] Catherine was therefore left in limbo for some time, culminating in Prince Henry’s rejection of the marriage as soon he was able, at the age of 14. Ferdinand’s solution was to make his daughter ambassador, allowing her to stay in England indefinitely. Devout, she began to believe that it was God’s will that she marry the prince despite his opposition.[19]

Early reign

Henry VII died on 21 April 1509, and the 17-year-old Henry succeeded him as king. Soon after his father’s burial on 10 May, Henry suddenly declared that he would indeed marry Catherine, leaving unresolved several issues concerning the papal dispensation and a missing part of the marriage portion.[17][20] The new king maintained that it had been his father’s dying wish that he marry Catherine.[19] Whether or not this was true, it was certainly convenient. Emperor Maximilian I had been attempting to marry his granddaughter Eleanor, Catherine’s niece, to Henry; she had now been jilted.[21] Henry’s wedding to Catherine was kept low-key and was held at the friar’s church in Greenwich on 11 June 1509.[20] Henry claimed descent from Constantine the Great and King Arthur and saw himself as their successor.[22]

On 23 June 1509, Henry led the now 23-year-old Catherine from the Tower of London to Westminster Abbey for their coronation, which took place the following day.[23] It was a grand affair: the king’s passage was lined with tapestries and laid with fine cloth.[23] Following the ceremony, there was a grand banquet in Westminster Hall.[24] As Catherine wrote to her father, «our time is spent in continuous festival».[20]

Two days after his coronation, Henry arrested his father’s two most unpopular ministers, Sir Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley. They were charged with high treason and were executed in 1510. Politically motivated executions would remain one of Henry’s primary tactics for dealing with those who stood in his way.[5] Henry also returned some of the money supposedly extorted by the two ministers.[25] By contrast, Henry’s view of the House of York – potential rival claimants for the throne – was more moderate than his father’s had been. Several who had been imprisoned by his father, including Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset, were pardoned.[26] Others went unreconciled; Edmund de la Pole was eventually beheaded in 1513, an execution prompted by his brother Richard siding against the king.[27]

Soon after marrying Henry, Catherine conceived. She gave birth to a stillborn girl on 31 January 1510. About four months later, Catherine again became pregnant.[28] On 1 January 1511, New Year’s Day, a son Henry was born. After the grief of losing their first child, the couple were pleased to have a boy and festivities were held,[29] including a two-day joust known as the Westminster Tournament. However, the child died seven weeks later.[28] Catherine had two stillborn sons in 1513 and 1515, but gave birth in February 1516 to a girl, Mary. Relations between Henry and Catherine had been strained, but they eased slightly after Mary’s birth.[30]

Although Henry’s marriage to Catherine has since been described as «unusually good»,[31] it is known that Henry took mistresses. It was revealed in 1510 that Henry had been conducting an affair with one of the sisters of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham, either Elizabeth or Anne Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon.[32] The most significant mistress for about three years, starting in 1516, was Elizabeth Blount.[30] Blount is one of only two completely undisputed mistresses, considered by some to be few for a virile young king.[33][34] Exactly how many Henry had is disputed: David Loades believes Henry had mistresses «only to a very limited extent»,[34] whilst Alison Weir believes there were numerous other affairs.[35] Catherine is not known to have protested. In 1518 she fell pregnant again with another girl, who was also stillborn.[30]

Blount gave birth in June 1519 to Henry’s illegitimate son, Henry FitzRoy.[30] The young boy was made Duke of Richmond in June 1525 in what some thought was one step on the path to his eventual legitimisation.[36] In 1533, FitzRoy married Mary Howard, but died childless three years later.[37] At the time of his death in June 1536, Parliament was considering the Second Succession Act, which could have allowed him to become king.[38]

France and the Habsburgs

In 1510, France, with a fragile alliance with the Holy Roman Empire in the League of Cambrai, was winning a war against Venice. Henry renewed his father’s friendship with Louis XII of France, an issue that divided his council. Certainly, war with the combined might of the two powers would have been exceedingly difficult.[39] Shortly thereafter, however, Henry also signed a pact with Ferdinand II of Aragon. After Pope Julius II created the anti-French Holy League in October 1511,[39] Henry followed Ferdinand’s lead and brought England into the new League. An initial joint Anglo-Spanish attack was planned for the spring to recover Aquitaine for England, the start of making Henry’s dreams of ruling France a reality.[40] The attack, however, following a formal declaration of war in April 1512, was not led by Henry personally[41] and was a considerable failure; Ferdinand used it simply to further his own ends, and it strained the Anglo-Spanish alliance. Nevertheless, the French were pushed out of Italy soon after, and the alliance survived, with both parties keen to win further victories over the French.[41][42] Henry then pulled off a diplomatic coup by convincing Emperor Maximilian to join the Holy League.[43] Remarkably, Henry had also secured the promised title of «Most Christian King of France» from Julius and possibly coronation by the Pope himself in Paris, if only Louis could be defeated.[44]

On 30 June 1513, Henry invaded France, and his troops defeated a French army at the Battle of the Spurs – a relatively minor result, but one which was seized on by the English for propaganda purposes. Soon after, the English took Thérouanne and handed it over to Maximillian; Tournai, a more significant settlement, followed.[45] Henry had led the army personally, complete with a large entourage.[46] His absence from the country, however, had prompted his brother-in-law James IV of Scotland to invade England at the behest of Louis.[47] Nevertheless, the English army, overseen by Queen Catherine, decisively defeated the Scots at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513.[48] Among the dead was the Scottish king, thus ending Scotland’s brief involvement in the war.[48] These campaigns had given Henry a taste of the military success he so desired. However, despite initial indications, he decided not to pursue a 1514 campaign. He had been supporting Ferdinand and Maximilian financially during the campaign but had received little in return; England’s coffers were now empty.[49] With the replacement of Julius by Pope Leo X, who was inclined to negotiate for peace with France, Henry signed his own treaty with Louis: his sister Mary would become Louis’ wife, having previously been pledged to the younger Charles, and peace was secured for eight years, a remarkably long time.[50]

Charles V, the nephew of Henry’s wife Catherine, inherited a large empire in Europe, becoming king of Spain in 1516 and Holy Roman Emperor in 1519. When Louis XII of France died in 1515, he was succeeded by his cousin Francis I.[51] These accessions left three relatively young rulers and an opportunity for a clean slate. The careful diplomacy of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey had resulted in the Treaty of London in 1518, aimed at uniting the kingdoms of western Europe in the wake of a new Ottoman threat, and it seemed that peace might be secured.[52] Henry met the new French king, Francis, on 7 June 1520 at the Field of the Cloth of Gold near Calais for a fortnight of lavish entertainment. Both hoped for friendly relations in place of the wars of the previous decade. The strong air of competition laid to rest any hopes of a renewal of the Treaty of London, however, and conflict was inevitable.[52] Henry had more in common with Charles, whom he met once before and once after Francis. Charles brought his realm into war with France in 1521; Henry offered to mediate, but little was achieved and by the end of the year Henry had aligned England with Charles. He still clung to his previous aim of restoring English lands in France but also sought to secure an alliance with Burgundy, then a territorial possession of Charles, and the continued support of the Emperor.[53] A small English attack in the north of France made up little ground. Charles defeated and captured Francis at Pavia and could dictate peace, but he believed he owed Henry nothing. Sensing this, Henry decided to take England out of the war before his ally, signing the Treaty of the More on 30 August 1525.[54]

Marriages

Family tree of the Wives of Henry VIII |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

King Henry VIII and all six of his wives were related through a common ancestor, King Edward I of England,[55] as follows:

|

Annulment from Catherine

During his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry conducted an affair with Mary Boleyn, Catherine’s lady-in-waiting. There has been speculation that Mary’s two children, Henry Carey and Catherine Carey, were fathered by Henry, but this has never been proved, and the king never acknowledged them as he did in the case of Henry FitzRoy.[58] In 1525, as Henry grew more impatient with Catherine’s inability to produce the male heir he desired,[59][60] he became enamoured of Mary Boleyn’s sister, Anne Boleyn, then a charismatic young woman of 25 in the queen’s entourage.[61] Anne, however, resisted his attempts to seduce her, and refused to become his mistress as her sister had.[62][nb 1] It was in this context that Henry considered his three options for finding a dynastic successor and hence resolving what came to be described at court as the king’s «great matter». These options were legitimising Henry FitzRoy, which would need the involvement of the Pope and would be open to challenge; marrying off Mary, his daughter with Catherine, as soon as possible and hoping for a grandson to inherit directly, but Mary was considered unlikely to conceive before Henry’s death, or somehow rejecting Catherine and marrying someone else of child-bearing age. Probably seeing the possibility of marrying Anne, the third was ultimately the most attractive possibility to the 34-year-old Henry,[64] and it soon became the king’s absorbing desire to annul his marriage to the now 40-year-old Catherine.[65]

Henry’s precise motivations and intentions over the coming years are not widely agreed on.[66] Henry himself, at least in the early part of his reign, was a devout and well-informed Catholic to the extent that his 1521 publication Assertio Septem Sacramentorum («Defence of the Seven Sacraments») earned him the title of Fidei Defensor (Defender of the Faith) from Pope Leo X.[67] The work represented a staunch defence of papal supremacy, albeit one couched in somewhat contingent terms.[67] It is not clear exactly when Henry changed his mind on the issue as he grew more intent on a second marriage. Certainly, by 1527, he had convinced himself that Catherine had produced no male heir because their union was «blighted in the eyes of God».[68] Indeed, in marrying Catherine, his brother’s wife, he had acted contrary to Leviticus 20:21, a justification Thomas Cranmer used to declare the marriage null.[69][nb 2] Martin Luther, on the other hand, had initially argued against the annulment, stating that Henry VIII could take a second wife in accordance with his teaching that the Bible allowed for polygamy but not divorce.[69] Henry now believed the Pope had lacked the authority to grant a dispensation from this impediment. It was this argument Henry took to Pope Clement VII in 1527 in the hope of having his marriage to Catherine annulled, forgoing at least one less openly defiant line of attack.[66] In going public, all hope of tempting Catherine to retire to a nunnery or otherwise stay quiet was lost.[70] Henry sent his secretary, William Knight, to appeal directly to the Holy See by way of a deceptively worded draft papal bull. Knight was unsuccessful; the Pope could not be misled so easily.[71]

Other missions concentrated on arranging an ecclesiastical court to meet in England, with a representative from Clement VII. Although Clement agreed to the creation of such a court, he never had any intention of empowering his legate, Lorenzo Campeggio, to decide in Henry’s favour.[71] This bias was perhaps the result of pressure from Emperor Charles V, Catherine’s nephew, but it is not clear how far this influenced either Campeggio or the Pope. After less than two months of hearing evidence, Clement called the case back to Rome in July 1529, from which it was clear that it would never re-emerge.[71] With the chance for an annulment lost, Cardinal Wolsey bore the blame. He was charged with praemunire in October 1529,[72] and his fall from grace was «sudden and total».[71] Briefly reconciled with Henry (and officially pardoned) in the first half of 1530, he was charged once more in November 1530, this time for treason, but died while awaiting trial.[71][73] After a short period in which Henry took government upon his own shoulders,[74] Sir Thomas More took on the role of Lord Chancellor and chief minister. Intelligent and able, but also a devout Catholic and opponent of the annulment,[75] More initially cooperated with the king’s new policy, denouncing Wolsey in Parliament.[76]

A year later, Catherine was banished from court, and her rooms were given to Anne Boleyn. Anne was an unusually educated and intellectual woman for her time and was keenly absorbed and engaged with the ideas of the Protestant Reformers, but the extent to which she herself was a committed Protestant is much debated.[63] When Archbishop of Canterbury William Warham died, Anne’s influence and the need to find a trustworthy supporter of the annulment had Thomas Cranmer appointed to the vacant position.[75] This was approved by the Pope, unaware of the king’s nascent plans for the Church.[77]

Henry was married to Catherine for 24 years. Their divorce has been described as a «deeply wounding and isolating» experience for Henry.[3]

Marriage to Anne Boleyn

Portrait of Anne Boleyn, Henry’s second queen; a copy of a lost original painted around 1534.

In the winter of 1532, Henry met with Francis I at Calais and enlisted the support of the French king for his new marriage.[78] Immediately upon returning to Dover in England, Henry, now 41, and Anne went through a secret wedding service.[79] She soon became pregnant, and there was a second wedding service in London on 25 January 1533. On 23 May 1533, Cranmer, sitting in judgment at a special court convened at Dunstable Priory to rule on the validity of the king’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, declared the marriage of Henry and Catherine null and void. Five days later, on 28 May 1533, Cranmer declared the marriage of Henry and Anne to be valid.[80] Catherine was formally stripped of her title as queen, becoming instead «princess dowager» as the widow of Arthur. In her place, Anne was crowned queen consort on 1 June 1533.[81] The queen gave birth to a daughter slightly prematurely on 7 September 1533. The child was christened Elizabeth, in honour of Henry’s mother, Elizabeth of York.[82]

Following the marriage, there was a period of consolidation, taking the form of a series of statutes of the Reformation Parliament aimed at finding solutions to any remaining issues, whilst protecting the new reforms from challenge, convincing the public of their legitimacy, and exposing and dealing with opponents.[83] Although the canon law was dealt with at length by Cranmer and others, these acts were advanced by Thomas Cromwell, Thomas Audley and the Duke of Norfolk and indeed by Henry himself.[84] With this process complete, in May 1532 More resigned as Lord Chancellor, leaving Cromwell as Henry’s chief minister.[85] With the Act of Succession 1533, Catherine’s daughter, Mary, was declared illegitimate; Henry’s marriage to Anne was declared legitimate; and Anne’s issue declared to be next in the line of succession.[86] With the Acts of Supremacy in 1534, Parliament also recognised the king’s status as head of the church in England and, together with the Act in Restraint of Appeals in 1532, abolished the right of appeal to Rome.[87] It was only then that Pope Clement VII took the step of excommunicating the king and Cranmer, although the excommunication was not made official until some time later.[nb 3]

The king and queen were not pleased with married life. The royal couple enjoyed periods of calm and affection, but Anne refused to play the submissive role expected of her. The vivacity and opinionated intellect that had made her so attractive as an illicit lover made her too independent for the largely ceremonial role of a royal wife and it made her many enemies. For his part, Henry disliked Anne’s constant irritability and violent temper. After a false pregnancy or miscarriage in 1534, he saw her failure to give him a son as a betrayal. As early as Christmas 1534, Henry was discussing with Cranmer and Cromwell the chances of leaving Anne without having to return to Catherine.[94] Henry is traditionally believed to have had an affair with Madge Shelton in 1535, although historian Antonia Fraser argues that Henry in fact had an affair with her sister Mary Shelton.[33]

Opposition to Henry’s religious policies was at first quickly suppressed in England. A number of dissenting monks, including the first Carthusian Martyrs, were executed and many more pilloried. The most prominent resisters included John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, and Sir Thomas More, both of whom refused to take the oath to the king.[95] Neither Henry nor Cromwell sought at that stage to have the men executed; rather, they hoped that the two might change their minds and save themselves. Fisher openly rejected Henry as the Supreme Head of the Church, but More was careful to avoid openly breaking the Treasons Act of 1534, which (unlike later acts) did not forbid mere silence. Both men were subsequently convicted of high treason, however – More on the evidence of a single conversation with Richard Rich, the Solicitor General, and both were executed in the summer of 1535.[95]

These suppressions, as well as the Dissolution of the Lesser Monasteries Act of 1536, in turn contributed to more general resistance to Henry’s reforms, most notably in the Pilgrimage of Grace, a large uprising in northern England in October 1536.[96] Some 20,000 to 40,000 rebels were led by Robert Aske, together with parts of the northern nobility.[97] Henry VIII promised the rebels he would pardon them and thanked them for raising the issues. Aske told the rebels they had been successful and they could disperse and go home.[98] Henry saw the rebels as traitors and did not feel obliged to keep his promises to them, so when further violence occurred after Henry’s offer of a pardon he was quick to break his promise of clemency.[99] The leaders, including Aske, were arrested and executed for treason. In total, about 200 rebels were executed, and the disturbances ended.[100]

Execution of Anne Boleyn

On 8 January 1536, news reached the king and queen that Catherine of Aragon had died. The following day, Henry dressed all in yellow, with a white feather in his bonnet.[101] Queen Anne was pregnant again, and she was aware of the consequences if she failed to give birth to a son. Later that month, the king was thrown from his horse in a tournament and was badly injured; it seemed for a time that his life was in danger. When news of this accident reached the queen, she was sent into shock and miscarried a male child at about 15 weeks’ gestation, on the day of Catherine’s funeral, 29 January 1536.[102] For most observers, this personal loss was the beginning of the end of this royal marriage.[103]

Although the Boleyn family still held important positions on the Privy Council, Anne had many enemies, including the Duke of Suffolk. Even her own uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, had come to resent her attitude to her power. The Boleyns preferred France over the Emperor as a potential ally, but the king’s favour had swung towards the latter (partly because of Cromwell), damaging the family’s influence.[104] Also opposed to Anne were supporters of reconciliation with Princess Mary (among them the former supporters of Catherine), who had reached maturity. A second annulment was now a real possibility, although it is commonly believed that it was Cromwell’s anti-Boleyn influence that led opponents to look for a way of having her executed.[105][106]

Anne’s downfall came shortly after she had recovered from her final miscarriage. Whether it was primarily the result of allegations of conspiracy, adultery, or witchcraft remains a matter of debate among historians.[63] Early signs of a fall from grace included the king’s new mistress, the 28-year-old Jane Seymour, being moved into new quarters,[107] and Anne’s brother, George Boleyn, being refused the Order of the Garter, which was instead given to Nicholas Carew.[108] Between 30 April and 2 May, five men, including George Boleyn, were arrested on charges of treasonable adultery and accused of having sexual relationships with the queen. Anne was also arrested, accused of treasonous adultery and incest. Although the evidence against them was unconvincing, the accused were found guilty and condemned to death. The accused men were executed on 17 May 1536.[109] Henry and Anne’s marriage was annulled by Archbishop Cranmer at Lambeth on the same day.[110] Cranmer appears to have had difficulty finding grounds for an annulment and probably based it on the prior liaison between Henry and Anne’s sister Mary, which in canon law meant that Henry’s marriage to Anne was, like his first marriage, within a forbidden degree of affinity and therefore void.[111] At 8 am on 19 May 1536, Anne was executed on Tower Green.[112]

Marriage to Jane Seymour; domestic and foreign affairs

Jane Seymour (left) became Henry’s third wife, pictured at right with Henry and the young Prince Edward, c. 1545, by an unknown artist. At the time that this was painted, Henry was married to his sixth wife, Catherine Parr.

The day after Anne’s execution the 45-year-old Henry became engaged to Seymour, who had been one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting. They were married ten days later[113] at the Palace of Whitehall, Whitehall, London, in the queen’s closet, by Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester.[114] On 12 October 1537, Jane gave birth to a son, Prince Edward, the future Edward VI.[115] The birth was difficult, and Queen Jane died on 24 October 1537 from an infection and was buried in Windsor.[116] The euphoria that had accompanied Edward’s birth became sorrow, but it was only over time that Henry came to long for his wife. At the time, Henry recovered quickly from the shock.[117] Measures were immediately put in place to find another wife for Henry, which, at the insistence of Cromwell and the Privy Council, were focused on the European continent.[118]

With Charles V distracted by the internal politics of his many kingdoms and also external threats, and Henry and Francis on relatively good terms, domestic and not foreign policy issues had been Henry’s priority in the first half of the 1530s. In 1536, for example, Henry granted his assent to the Laws in Wales Act 1535, which legally annexed Wales, uniting England and Wales into a single nation. This was followed by the Second Succession Act (the Act of Succession 1536), which declared Henry’s children by Jane to be next in the line of succession and declared both Mary and Elizabeth illegitimate, thus excluding them from the throne. The king was also granted the power to further determine the line of succession in his will, should he have no further issue.[119]

In 1538, as part of the negotiation of a secret treaty by Cromwell with Charles V, a series of dynastic marriages were proposed: Mary would marry a son of the King of Portugal, Elizabeth marry one of the sons of the King of Hungary and the infant Edward marry one of the Emperor’s daughters. The widowed King, it was suggested, might marry the Dowager Duchess of Milan.[120] However, when Charles and Francis made peace in January 1539, Henry became increasingly paranoid, perhaps as a result of receiving a constant list of threats to the kingdom (real or imaginary, minor or serious) supplied by Cromwell in his role as spymaster.[121] Enriched by the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry used some of his financial reserves to build a series of coastal defences and set some aside for use in the event of a Franco-German invasion.[122]

Marriage to Anne of Cleves

Having considered the matter, Cromwell suggested Anne, the 25-year-old sister of the Duke of Cleves, who was seen as an important ally in case of a Roman Catholic attack on England, for the duke fell between Lutheranism and Catholicism.[123] Hans Holbein the Younger was dispatched to Cleves to paint a portrait of Anne for the king.[124] Despite speculation that Holbein painted her in an overly flattering light, it is more likely that the portrait was accurate; Holbein remained in favour at court.[125] After seeing Holbein’s portrait, and urged on by the complimentary description of Anne given by his courtiers, the 49-year-old king agreed to wed Anne.[126] The marriage took place in January 1540.

However, it was not long before Henry wished to annul the marriage so he could marry another.[127][128] Anne did not argue, and confirmed that the marriage had never been consummated.[129] Anne’s previous betrothal to the Duke of Lorraine’s son Francis provided further grounds for the annulment.[130] The marriage was subsequently dissolved in July 1540, and Anne received the title of «The King’s Sister», two houses, and a generous allowance.[129] It was soon clear that Henry had fallen for the 17-year-old Catherine Howard, the Duke of Norfolk’s niece. This worried Cromwell, for Norfolk was his political opponent.[131]

Shortly after, the religious reformers (and protégés of Cromwell) Robert Barnes, William Jerome and Thomas Garret were burned as heretics.[129] Cromwell, meanwhile, fell out of favour although it is unclear exactly why, for there is little evidence of differences in domestic or foreign policy. Despite his role, he was never formally accused of being responsible for Henry’s failed marriage.[132] Cromwell was now surrounded by enemies at court, with Norfolk also able to draw on his niece Catherine’s position.[131] Cromwell was charged with treason, selling export licences, granting passports, and drawing up commissions without permission, and may also have been blamed for the failure of the foreign policy that accompanied the attempted marriage to Anne.[133][134] He was subsequently attainted and beheaded.[132]

Marriage to Catherine Howard

On 28 July 1540 (the same day Cromwell was executed), Henry married the young Catherine Howard, a first cousin and lady-in-waiting of Anne Boleyn.[135] He was delighted with his new queen and awarded her the lands of Cromwell and a vast array of jewellery.[136] Soon after the marriage, however, Queen Catherine had an affair with the courtier Thomas Culpeper. She also employed Francis Dereham, who had previously been informally engaged to her and had an affair with her prior to her marriage, as her secretary. The Privy Council was informed of her affair with Dereham whilst Henry was away; Thomas Cranmer was dispatched to investigate, and he brought evidence of Queen Catherine’s previous affair with Dereham to the king’s notice.[137] Though Henry originally refused to believe the allegations, Dereham confessed. It took another meeting of the council, however, before Henry believed the accusations against Dereham and went into a rage, blaming the council before consoling himself in hunting.[138] When questioned, the queen could have admitted a prior contract to marry Dereham, which would have made her subsequent marriage to Henry invalid, but she instead claimed that Dereham had forced her to enter into an adulterous relationship. Dereham, meanwhile, exposed Catherine’s relationship with Culpeper. Culpeper and Dereham were both executed, and Catherine too was beheaded on 13 February 1542.[139]

Marriage to Catherine Parr

Henry married his last wife, the wealthy widow Catherine Parr, in July 1543.[140] A reformer at heart, she argued with Henry over religion. Henry remained committed to an idiosyncratic mixture of Catholicism and Protestantism; the reactionary mood that had gained ground after Cromwell’s fall had neither eliminated his Protestant streak nor been overcome by it.[141] Parr helped reconcile Henry with his daughters, Mary and Elizabeth.[142] In 1543, the Third Succession Act put them back in the line of succession after Edward. The same act allowed Henry to determine further succession to the throne in his will.[143]

Shrines destroyed and monasteries dissolved

In 1538, the chief minister Thomas Cromwell pursued an extensive campaign against what the government termed «idolatry» practised under the old religion, culminating in September with the dismantling of the shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. As a consequence, the king was excommunicated by Pope Paul III on 17 December of the same year.[92] In 1540, Henry sanctioned the complete destruction of shrines to saints. In 1542, England’s remaining monasteries were all dissolved, and their property transferred to the Crown. Abbots and priors lost their seats in the House of Lords; only archbishops and bishops remained. Consequently, the Lords Spiritual – as members of the clergy with seats in the House of Lords were known – were for the first time outnumbered by the Lords Temporal.

Second invasion of France and the «Rough Wooing» of Scotland

The 1539 alliance between Francis and Charles had soured, eventually degenerating into renewed war. With Catherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn dead, relations between Charles and Henry improved considerably, and Henry concluded a secret alliance with the Emperor and decided to enter the Italian War in favour of his new ally. An invasion of France was planned for 1543.[144] In preparation for it, Henry moved to eliminate the potential threat of Scotland under the youthful James V. The Scots were defeated at Battle of Solway Moss on 24 November 1542,[145] and James died on 15 December. Henry now hoped to unite the crowns of England and Scotland by marrying his son Edward to James’ successor, Mary. The Scottish Regent Lord Arran agreed to the marriage in the Treaty of Greenwich on 1 July 1543, but it was rejected by the Parliament of Scotland on 11 December. The result was eight years of war between England and Scotland, a campaign later dubbed «the Rough Wooing». Despite several peace treaties, unrest continued in Scotland until Henry’s death.[146][147][148]

Despite the early success with Scotland, Henry hesitated to invade France, annoying Charles. Henry finally went to France in June 1544 with a two-pronged attack. One force under Norfolk ineffectively besieged Montreuil. The other, under Suffolk, laid siege to Boulogne. Henry later took personal command, and Boulogne fell on 18 September 1544.[149][146] However, Henry had refused Charles’ request to march against Paris. Charles’ own campaign fizzled, and he made peace with France that same day.[147] Henry was left alone against France, unable to make peace. Francis attempted to invade England in the summer of 1545 but reached only the Isle of Wight before being repulsed in the Battle of the Solent. Financially exhausted, France and England signed the Treaty of Camp on 7 June 1546. Henry secured Boulogne for eight years. The city was then to be returned to France for 2 million crowns (£750,000). Henry needed the money; the 1544 campaign had cost £650,000, and England was once again facing bankruptcy.[147]

Physical decline and death