Исаак Ньютон — биография

Исаак Ньютон – математик, физик, астроном, механик. Сформулировал закон о всемирном тяготении, автор трех законов механики, вошедших в основу классической механики. Ему принадлежит разработка интегрального и дифференциального исчисления и теория цвета.

Исаака Ньютона считают величайшим светилом научного мира. Он прославился в физике и математике, открыл закон гравитации, движения и исчисления. И это кроме основной деятельности. Родившись в семье неграмотных крестьян, он собственным умом постиг тайны Вселенной, стал одним из создателей классической физики. Отличался скрытностью и замкнутым характером, некоторые свои открытия он так и не продемонстрировал своим современникам.

Детство

Родился Исаак Ньютон 4 января 1643 года (по юлианскому календарю) в деревне Вулсторп, расположенной в графстве Линкольншир в Великобритании. Мальчик родился недоношенным в самый канун Рождества, и потом считал это хорошей приметой. А пока он был хилым и слабым ребенком, у которого было мало шансов на выживание. Его долго не крестили, потому что не были уверены, что он вообще выживет. Однако мальчишка оказался на удивление живучим, он не только выкарабкался, но и сумел дожить до глубокой старости. Ньютон умер в 84, и это было скорее исключением, чем правилом в семнадцатом веке.

Своего отца мальчик не знал, Исаак Ньютон-старший умер за несколько месяцев до рождения сына. Новорожденного назвали в честь отца, достаточно состоятельного и успешного мелкого фермера. После того, как он умер, жена унаследовала поля и лесные угодия с плодородной землей. А еще ей досталась баснословная по тем временам сумма – пятьсот фунтов стерлингов.

Мама мальчика – Анна Эйскоу, вскоре устроила свою личную жизнь. Ее мужем стал богатый священник Варнава Смит, который не питал нежных чувств к своему трехлетнему пасынку. Мать с ее новым мужем переехали в другую деревню, а Исаак остался на попечении бабушки, а потом дяди Уильяма Эйскоу. Вскоре один за другим у Анны и Варнавы родилось трое детей.

Исаак рос разносторонне развитым ребенком. Ему нравилась поэзия, живопись, он трудился над изобретением ветряной мельницы и водяных часов, часами возился с бумажными змеями. Мальчик по-прежнему не отличался богатырским здоровьем и не любил общаться со сверстниками. Вместо веселых игр во дворе он проводил время в уединении, предпочитая заниматься тем, что представляло для него интерес.

В школе Исаак никак не мог подружиться со сверстниками, к тому же часто болел и пропускал занятия. Все это раздражало его одноклассников, и однажды они избили его до полусмерти. Это было большим унижением, и ответить кулаками своим обидчикам Ньютон не мог, потому что никогда не был силачом. Тогда он решил завоевать уважение своим умом.

До этого происшествия Исаак учился очень плохо, из-за чего его не любили учителя. После драки он всерьез взялся за учебу, постепенно приобрел себе славу лучшего ученика. Теперь его все больше интересовала математика, техника и необъяснимые явления в природе.

К шестнадцатилетию старшего сына мать снова овдовела, и ей самой было трудно управляться с хозяйством. Она привезла Исаака в родное поместье, в надежде на то, что он поможет ей вести домашние дела. Но, в то время Ньютон уже был серьезно увлечен конструированием разных механизмов, много читал и даже сочинял стихи.

Мать это очень раздражало, а тут еще друзья и родственники начали уговаривать ее дать согласие на то, чтобы парень продолжал учебу. Так, с помощью школьного учителя мистера Стокса, родного дяди Уильяма Эйскоу и знакомого Хэмфри Бабингтона, Исаак смог в 1661-м окончить школу и стать студентом Кембриджского университета.

Научная карьера

В вузе Исаак учился в статусе «sizar». Это человек, который учится бесплатно, но за это задействуется в разноплановых работах, в том числе и в помощи обеспеченным студентам. Ньютону не нравилось его положение, но он собрал все свое мужество и справился. Он был таким же нелюдимым, как и раньше, у него абсолютно не было друзей.

В те времена в Кембриджском университете учили естествознание и философию, опираясь на учения Аристотеля, несмотря на то, что уже было известно об открытиях Галлилея, Коперника и Кеплера. Ньютон много читал, он живо интересовался всеми новинками в мире астрономии, математики, фонетики и оптики. Молодой человек изучал даже теорию музыки, в общем, все, что было новым и попадалось ему под руку. Ему так нравилось это занятие, что он иногда не мог вспомнить, спал ли он, и что ел.

В 1664-м Исаак Ньютон начал самостоятельно трудиться. Он выделил основные проблемы человека и природы, которых насчитывалось сорок пять, и которые никто до него не пытался решить. Биография студента изменилась в том же году, после того, как в его жизни появился талантливый математик Исаак Барроу, преподаватель математической кафедры вуза. Спустя некоторое время Барроу стал учителем Ньютона и по совместительству одним из малочисленных друзей ученого.

Барроу сумел привить Ньютону любовь к математике, он стал серьезно заниматься этой наукой. Вскоре он уже мог похвастаться своим первым открытием в области математики – биноминальным разложением для производного рационального показателя. В это же время Ньютон стал бакалавром.

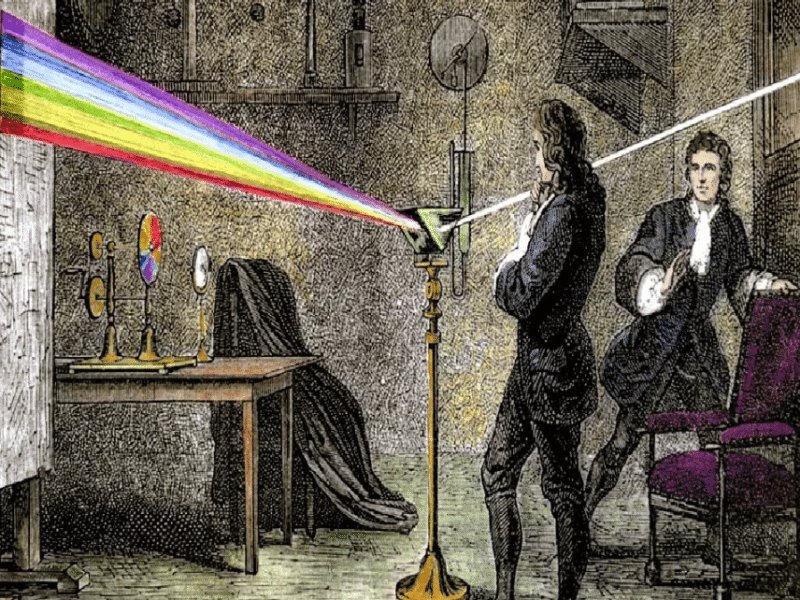

С 1665 по 1667 годы Исаак жил в родовом поместье в Вусторпе. Тогда Англия находилась во власти бубонной чумы, воевала с Голландией, и поэтому университет закрыли. Однако и дома он не прекращает своих научных изысканий. Основной интерес в те годы для Ньютона представляла оптика. Его интересовал вопрос преодоления хроматической аберрации в линзовых телескопах, и изучение этого явления привело его к открытию дисперсии. Он ставил эксперименты для познания физической природы света. Его опыты и сейчас проводят во многих вузах.

В итоге Исаак открыл корпускулярную модель света, он понял, что это поток частиц, вылетающий из источника света и прямолинейно двигающийся к ближайшему препятствию. Эта модель была очень далека от объективности, но стала основой в классической физике. Именно благодаря ей, потом сформировались современные понятия о физике явлений.

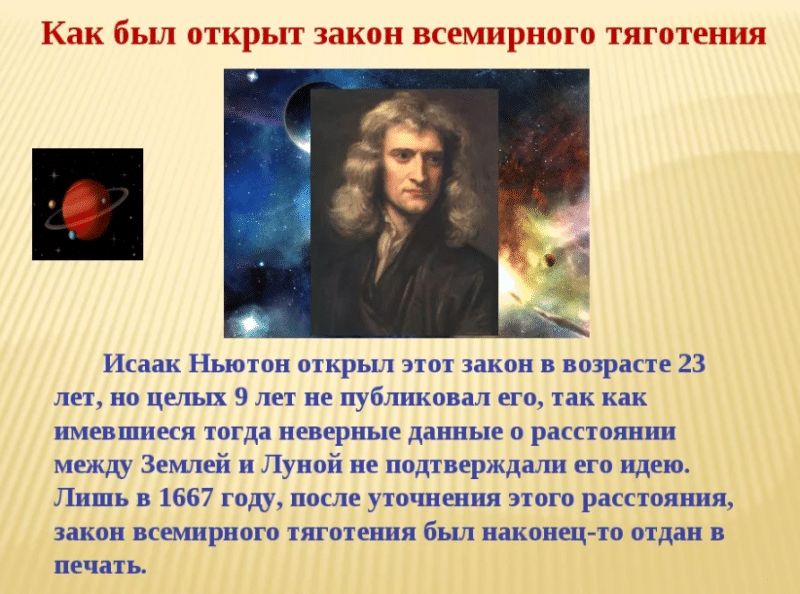

В то же время Ньютон открыл свой самый известный закон – о всемирном тяготении. Однако опубликован он был спустя несколько десятилетий, потому что Ньютона больше интересовал сам процесс, а не слава.

Любители любопытных фактов придерживаются мнения, что в открытии этого закона Ньютону помогло упавшее на голову яблоко. На самом деле ученый долго шел к этому открытию, проделывал опыты, записывал все в журнал.

Результатом долгого и кропотливого труда и стало это открытие. А вот легенда об упавшем на голову ученого яблоке принадлежит перу философа Вольтера.

Могут быть знакомы

Светило науки

После возвращения в конце 1660-х в Кембридж, Исаак Ньютон стал магистром. Теперь ему полагалась собственная комната и группа молодых студентов, которым он преподавал математику. Однако Исаак не очень любил преподавательскую деятельность, его больше интересовали научные разработки. Студенты это быстро «просекли» и стали прогуливать его лекции. Случалось такое, что аудитория была абсолютно пустой во время его урока. Зато Ньютон отметился изобретением телескопа-рефлектора, благодаря которому стал членом Лондонского королевского общества. Благодаря его изобретению, стали возможными большие открытия в астрономии.

В 1687-м в печать попала самая важная из всех работ ученого – книга, которую он назвал «Математические начала натуральной философии». Ньютон и до этого уже печатался, но именно этот труд имел очень большое значение – благодаря ему возникла рациональная механика и все математическое естествознание. Этот труд состоял из закона всемирного тяготения, трех уже знакомых законов механики, которые стали основой классической физики, ключевых понятий в физике.

Математический и физический уровень труда Ньютона превосходили все то, что до него открыли другие ученые в этой области. Работа не содержала недоказанную метафизику, в ней отсутствовали пространные рассуждения, необоснованные законы и расплывчатые формулировки, которых придерживались в своих трудах Декарт и Аристотель.

В 1699-м в Кембриджском университете студентов учили по системе мира Ньютона. В это время ученый занимал административные должности.

Личная жизнь и смерть

Выдающийся ученый был слишком занят своими изысканиями, он иногда забывал поесть и поспать, не говоря уже о женщинах. У него полностью отсутствовала личная жизнь, только бесконечное служение науке. Ученый не был женат, и наследников после себя не оставил.

Здоровье Ньютона резко пошатнулось в 1725 году. Он переехал в Кенсингтон рядом с Лондоном, где и умер 31 марта 1727 года. Ученый не оставил письменное завещание, но буквально перед смертью большую часть своего состояния отдал близким родственникам. Хоронили Ньютона с большими почестями. Местом его упокоения стало Вестминстерское аббатство, по соседству с королями и выдающимися общественными деятелями.

Основные труды

- «Новая теория света и цветов»

- «Движение тел по орбите»

- «Математические начала натуральной философии»

- «Оптика или трактат об отражениях, преломлениях, изгибаниях и цветах света»

- «О квадратуре кривых»

- «Перечисление линий третьего порядка»

- «Универсальная арифметика»

- «Анализ с помощью уравнений с бесконечным числом членов»

- «Метод разностей»

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

If you have found a spelling error, please, notify us by selecting that text and tap on selected text.

Биография Ньютона

4 Января 1643 – 31 Марта 1727 гг. (84 года)

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 625.

Исаак Ньютон (1642–1727 гг.) – выдающийся английский ученый, один из создателей классической физики. Биография Ньютона богата во всех смыслах этого слова. Он сделал немало открытий в области физики, астрономии, механики и математики, в том числе открыл закон всемирного тяготения.

Детские и юные годы

Исаак Ньютон родился 25 декабря 1642 (или 4 января 1643 г. по грегорианскому календарю) в деревне Вулсторп, графство Линкольншир.

Юный Исаак, по свидетельству современников, отличался мрачным, замкнутым характером. Мальчишеским шалостям и проказам он предпочитал чтение книг и изготовление примитивных технических игрушек.

Когда Исааку исполнилось 12 лет, он поступил на обучение в Грэнтемскую школу. Незаурядные способности будущего ученого обнаружились именно там.

В 1659 г., по настоянию матери, Ньютон был вынужден вернуться домой, чтобы вести фермерское хозяйство. Но благодаря усилиям учителей, сумевших разглядеть будущий гений, он вернулся в школу. В 1661 г. Ньютон продолжил образование в Кембриджском университете.

Обучение в колледже

В апреле 1664 г. Ньютон успешно сдал экзамены и приобрел более высокую студенческую ступень. Во время обучения он активно интересовался работами Г. Галилея, Н. Коперника, а также атомистической теорией Гассенди.

Весной 1663 г. на новой, математической кафедре начались лекции И. Барроу. Известный математик и крупный ученый позже стал близким другом Ньютона. Именно благодаря ему у Исаака возрос интерес к математике.

Во время обучения в колледже Ньютон пришел к своему основному математическому методу – разложению функции в бесконечный ряд. В конце этого же года И. Ньютон получил бакалаврскую степень.

Известные открытия

Изучая краткую биографию Исаака Ньютона, следует знать, что именно ему принадлежит изложение закона всемирного тяготения. Еще одним важнейшим открытием ученого является теория движения небесных тел. Открытые Ньютоном 3 закона механики легли в основу классической механики.

Ньютон сделал немало открытий в области оптики и теории цвета. Им были разработаны многие физические и математические теории. Научные труды выдающегося ученого во многом определяли время и часто были непонятны современникам.

Его гипотезы относительно сплюснутости полюсов Земли, явления поляризации света и отклонения света в поле тяготения и сегодня вызывают удивление ученых.

В 1668 г. Ньютон получил степень магистра. Еще через год он стал доктором математических наук. После создания им рефлектора, предтечи телескопа, в астрономии были сделаны важнейшие открытия.

Общественная деятельность

В 1689 г., в результате переворота, был свергнут король Яков II, с которым у Ньютона был конфликт. После этого ученого избрали в парламент от Кембриджского университета, в котором он заседал около 12 мес.

В 1679 г. произошло знакомство Ньютона с Ч. Монтегю, будущим графом Галифаксом. По протекции Монтегю Ньютон был назначен хранителем Монетного двора.

Последние годы жизни

В 1725 г. здоровье великого ученого стало стремительно ухудшаться. Он ушел из жизни 20 (31) марта 1727 г., в Кенсингтоне. Смерть наступила во сне. Похоронен Исаак Ньютон был в Вестминстерском аббатстве.

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Интересные факты

- В самом начале своего школьного обучения, Ньютон считался весьма посредственным, едва ли не худшим учеником. В лучшие его заставила выбиться моральная травма, когда он был избит своим рослым и намного более сильным одноклассником.

- В последние годы жизни великий ученый писал некую книгу, которая, по его мнению, должна была стать неким откровением. К сожалению, рукописи горят. По вине любимой собаки ученого, опрокинувшей лампу, книга исчезла в огне.

Тест по биографии

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Кристина Малышева

9/10

-

Наиль Галямов

10/10

-

Алексей Коваленко

7/10

-

Ами Магомедова

6/10

-

Михаил Калугин

10/10

-

Диана Сергеева

7/10

-

Александр Котков

9/10

Оценка по биографии

4.3

Средняя оценка: 4.3

Всего получено оценок: 625.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

This article is about the scientist and mathematician. For the American agriculturalist, see Isaac Newton (agriculturalist).

|

Sir Isaac Newton PRS |

|

|---|---|

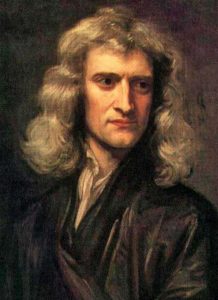

Portrait of Newton at 46 by Godfrey Kneller, 1689 |

|

| Born | 4 January 1643 [O.S. 25 December 1642][a]

Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 31 March 1727 (aged 84) [O.S. 20 March 1726][a]

Kensington, Middlesex, Great Britain |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Education | Trinity College, Cambridge (M.A., 1668)[2] |

| Known for |

List

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors |

|

| Notable students |

|

| Influences |

|

| Influenced |

List

|

| Member of Parliament for the University of Cambridge | |

| In office 1689–1690 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert Brady |

| Succeeded by | Edward Finch |

| In office 1701–1702 |

|

| Preceded by | Anthony Hammond |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Annesley, 5th Earl of Anglesey |

| 12th President of the Royal Society | |

| In office 1703–1727 |

|

| Preceded by | John Somers |

| Succeeded by | Hans Sloane |

| Master of the Mint | |

| In office 1699–1727 |

|

| 1696–1699 | Warden of the Mint |

| Preceded by | Thomas Neale |

| Succeeded by | John Conduitt |

| 2nd Lucasian Professor of Mathematics | |

| In office 1669–1702 |

|

| Preceded by | Isaac Barrow |

| Succeeded by | William Whiston |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Whig |

| Signature | |

|

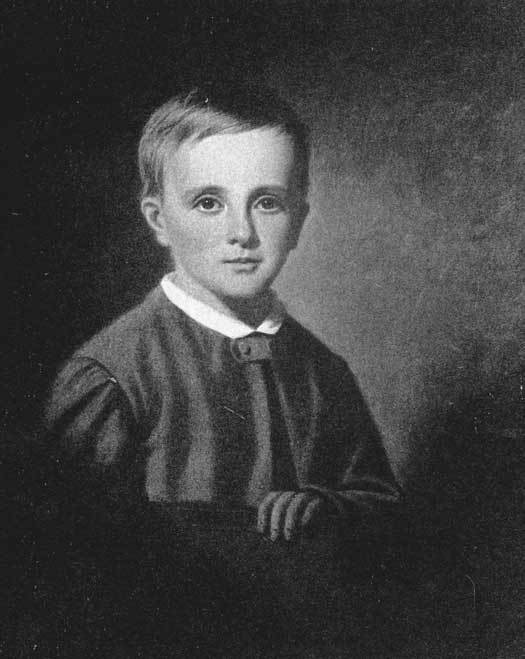

Sir Isaac Newton PRS (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27)[a] was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a «natural philosopher»), widely recognised as one of the greatest mathematicians and physicists and among the most influential scientists of all time. He was a key figure in the philosophical revolution known as the Enlightenment. His book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1687, established classical mechanics. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for developing infinitesimal calculus.

In the Principia, Newton formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation that formed the dominant scientific viewpoint for centuries until it was superseded by the theory of relativity. Newton used his mathematical description of gravity to derive Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, account for tides, the trajectories of comets, the precession of the equinoxes and other phenomena, eradicating doubt about the Solar System’s heliocentricity. He demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and celestial bodies could be accounted for by the same principles. Newton’s inference that the Earth is an oblate spheroid was later confirmed by the geodetic measurements of Maupertuis, La Condamine, and others, convincing most European scientists of the superiority of Newtonian mechanics over earlier systems.

Newton built the first practical reflecting telescope and developed a sophisticated theory of colour based on the observation that a prism separates white light into the colours of the visible spectrum. His work on light was collected in his highly influential book Opticks, published in 1704. He also formulated an empirical law of cooling, made the first theoretical calculation of the speed of sound, and introduced the notion of a Newtonian fluid. In addition to his work on calculus, as a mathematician Newton contributed to the study of power series, generalised the binomial theorem to non-integer exponents, developed a method for approximating the roots of a function, and classified most of the cubic plane curves.

Newton was a fellow of Trinity College and the second Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge. He was a devout but unorthodox Christian who privately rejected the doctrine of the Trinity. He refused to take holy orders in the Church of England, unlike most members of the Cambridge faculty of the day. Beyond his work on the mathematical sciences, Newton dedicated much of his time to the study of alchemy and biblical chronology, but most of his work in those areas remained unpublished until long after his death. Politically and personally tied to the Whig party, Newton served two brief terms as Member of Parliament for the University of Cambridge, in 1689–1690 and 1701–1702. He was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705 and spent the last three decades of his life in London, serving as Warden (1696–1699) and Master (1699–1727) of the Royal Mint, as well as president of the Royal Society (1703–1727).

Early life

Early life

Isaac Newton was born (according to the Julian calendar in use in England at the time) on Christmas Day, 25 December 1642 (NS 4 January 1643[a]), «an hour or two after midnight»,[17] at Woolsthorpe Manor in Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth, a hamlet in the county of Lincolnshire. His father, also named Isaac Newton, had died three months before. Born prematurely, Newton was a small child; his mother Hannah Ayscough reportedly said that he could have fit inside a quart mug.[18] When Newton was three, his mother remarried and went to live with her new husband, the Reverend Barnabas Smith, leaving her son in the care of his maternal grandmother, Margery Ayscough (née Blythe). Newton disliked his stepfather and maintained some enmity towards his mother for marrying him, as revealed by this entry in a list of sins committed up to the age of 19: «Threatening my father and mother Smith to burn them and the house over them.»[19] Newton’s mother had three children (Mary, Benjamin, and Hannah) from her second marriage.[20]

The King’s School

From the age of about twelve until he was seventeen, Newton was educated at The King’s School in Grantham, which taught Latin and Ancient Greek and probably imparted a significant foundation of mathematics.[21] He was removed from school and returned to Woolsthorpe-by-Colsterworth by October 1659. His mother, widowed for the second time, attempted to make him a farmer, an occupation he hated.[22] Henry Stokes, master at The King’s School, persuaded his mother to send him back to school. Motivated partly by a desire for revenge against a schoolyard bully, he became the top-ranked student,[23] distinguishing himself mainly by building sundials and models of windmills.[24]

University of Cambridge

In June 1661, Newton was admitted to Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. His uncle Reverend William Ayscough, who had studied at Cambridge, recommended him to the university. At Cambridge, Newton started as a subsizar, paying his way by performing valet duties until he was awarded a scholarship in 1664, which covered his university costs for four more years until the completion of his MA.[25] At the time, Cambridge’s teachings were based on those of Aristotle, whom Newton read along with then more modern philosophers, including Descartes and astronomers such as Galileo Galilei and Thomas Street. He set down in his notebook a series of «Quaestiones» about mechanical philosophy as he found it. In 1665, he discovered the generalised binomial theorem and began to develop a mathematical theory that later became calculus. Soon after Newton obtained his BA degree at Cambridge in August 1665, the university temporarily closed as a precaution against the Great Plague. Although he had been undistinguished as a Cambridge student,[26] Newton’s private studies at his home in Woolsthorpe over the next two years saw the development of his theories on calculus,[27] optics, and the law of gravitation.

In April 1667, Newton returned to the University of Cambridge, and in October he was elected as a fellow of Trinity.[28][29] Fellows were required to be ordained as priests, although this was not enforced in the restoration years and an assertion of conformity to the Church of England was sufficient. However, by 1675 the issue could not be avoided and by then his unconventional views stood in the way.[30] Nevertheless, Newton managed to avoid it by means of special permission from Charles II.

His academic work impressed the Lucasian professor Isaac Barrow, who was anxious to develop his own religious and administrative potential (he became master of Trinity College two years later); in 1669, Newton succeeded him, only one year after receiving his MA. Newton was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1672.[3]

Work

Calculus

Newton’s work has been said «to distinctly advance every branch of mathematics then studied».[31] His work on the subject, usually referred to as fluxions or calculus, seen in a manuscript of October 1666, is now published among Newton’s mathematical papers.[32] His work De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas, sent by Isaac Barrow to John Collins in June 1669, was identified by Barrow in a letter sent to Collins that August as the work «of an extraordinary genius and proficiency in these things».[33]

Newton later became involved in a dispute with Leibniz over priority in the development of calculus (the Leibniz–Newton calculus controversy). Most modern historians believe that Newton and Leibniz developed calculus independently, although with very different mathematical notations. Occasionally it has been suggested that Newton published almost nothing about it until 1693, and did not give a full account until 1704, while Leibniz began publishing a full account of his methods in 1684. Leibniz’s notation and «differential Method», nowadays recognised as much more convenient notations, were adopted by continental European mathematicians, and after 1820 or so, also by British mathematicians.[citation needed]

His work extensively uses calculus in geometric form based on limiting values of the ratios of vanishingly small quantities: in the Principia itself, Newton gave demonstration of this under the name of «the method of first and last ratios»[34] and explained why he put his expositions in this form,[35] remarking also that «hereby the same thing is performed as by the method of indivisibles.»[36]

Because of this, the Principia has been called «a book dense with the theory and application of the infinitesimal calculus» in modern times[37] and in Newton’s time «nearly all of it is of this calculus.»[38] His use of methods involving «one or more orders of the infinitesimally small» is present in his De motu corporum in gyrum of 1684[39] and in his papers on motion «during the two decades preceding 1684».[40]

Newton had been reluctant to publish his calculus because he feared controversy and criticism.[41] He was close to the Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier. In 1691, Duillier started to write a new version of Newton’s Principia, and corresponded with Leibniz.[42] In 1693, the relationship between Duillier and Newton deteriorated and the book was never completed.[43]

Starting in 1699, other members[who?] of the Royal Society accused Leibniz of plagiarism.[44] The dispute then broke out in full force in 1711 when the Royal Society proclaimed in a study that it was Newton who was the true discoverer and labelled Leibniz a fraud; it was later found that Newton wrote the study’s concluding remarks on Leibniz. Thus began the bitter controversy which marred the lives of both Newton and Leibniz until the latter’s death in 1716.[45]

Newton is generally credited with the generalised binomial theorem, valid for any exponent. He discovered Newton’s identities, Newton’s method, classified cubic plane curves (polynomials of degree three in two variables), made substantial contributions to the theory of finite differences, and was the first to use fractional indices and to employ coordinate geometry to derive solutions to Diophantine equations. He approximated partial sums of the harmonic series by logarithms (a precursor to Euler’s summation formula) and was the first to use power series with confidence and to revert power series. Newton’s work on infinite series was inspired by Simon Stevin’s decimals.[46]

When Newton received his MA and became a Fellow of the «College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity» in 1667, he made the commitment that «I will either set Theology as the object of my studies and will take holy orders when the time prescribed by these statutes [7 years] arrives, or I will resign from the college.»[47] Up until this point he had not thought much about religion and had twice signed his agreement to the thirty-nine articles, the basis of Church of England doctrine.

He was appointed Lucasian Professor of Mathematics in 1669, on Barrow’s recommendation. During that time, any Fellow of a college at Cambridge or Oxford was required to take holy orders and become an ordained Anglican priest. However, the terms of the Lucasian professorship required that the holder not be active in the church – presumably,[weasel words] so as to have more time for science. Newton argued that this should exempt him from the ordination requirement, and Charles II, whose permission was needed, accepted this argument; thus, a conflict between Newton’s religious views and Anglican orthodoxy was averted.[48]

Optics

In 1666, Newton observed that the spectrum of colours exiting a prism in the position of minimum deviation is oblong, even when the light ray entering the prism is circular, which is to say, the prism refracts different colours by different angles.[50][51] This led him to conclude that colour is a property intrinsic to light – a point which had, until then, been a matter of debate.

From 1670 to 1672, Newton lectured on optics.[52] During this period he investigated the refraction of light, demonstrating that the multicoloured image produced by a prism, which he named a spectrum, could be recomposed into white light by a lens and a second prism.[53] Modern scholarship has revealed that Newton’s analysis and resynthesis of white light owes a debt to corpuscular alchemy.[54]

He showed that coloured light does not change its properties by separating out a coloured beam and shining it on various objects, and that regardless of whether reflected, scattered, or transmitted, the light remains the same colour. Thus, he observed that colour is the result of objects interacting with already-coloured light rather than objects generating the colour themselves. This is known as Newton’s theory of colour.[55]

Illustration of a dispersive prism separating white light into the colours of the spectrum, as discovered by Newton

From this work, he concluded that the lens of any refracting telescope would suffer from the dispersion of light into colours (chromatic aberration). As a proof of the concept, he constructed a telescope using reflective mirrors instead of lenses as the objective to bypass that problem.[56][57] Building the design, the first known functional reflecting telescope, today known as a Newtonian telescope,[57] involved solving the problem of a suitable mirror material and shaping technique. Newton ground his own mirrors out of a custom composition of highly reflective speculum metal, using Newton’s rings to judge the quality of the optics for his telescopes. In late 1668,[58] he was able to produce this first reflecting telescope. It was about eight inches long and it gave a clearer and larger image. In 1671, the Royal Society asked for a demonstration of his reflecting telescope.[59] Their interest encouraged him to publish his notes, Of Colours,[60] which he later expanded into the work Opticks. When Robert Hooke criticised some of Newton’s ideas, Newton was so offended that he withdrew from public debate. Newton and Hooke had brief exchanges in 1679–80, when Hooke, appointed to manage the Royal Society’s correspondence, opened up a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions,[61] which had the effect of stimulating Newton to work out a proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector. But the two men remained generally on poor terms until Hooke’s death.[62]

Facsimile of a 1682 letter from Newton to William Briggs, commenting on Briggs’ A New Theory of Vision

Newton argued that light is composed of particles or corpuscles, which were refracted by accelerating into a denser medium. He verged on soundlike waves to explain the repeated pattern of reflection and transmission by thin films (Opticks Bk.II, Props. 12), but still retained his theory of ‘fits’ that disposed corpuscles to be reflected or transmitted (Props.13). However, later physicists favoured a purely wavelike explanation of light to account for the interference patterns and the general phenomenon of diffraction. Today’s quantum mechanics, photons, and the idea of wave–particle duality bear only a minor resemblance to Newton’s understanding of light.

In his Hypothesis of Light of 1675, Newton posited the existence of the ether to transmit forces between particles. The contact with the Cambridge Platonist philosopher Henry More revived his interest in alchemy.[63] He replaced the ether with occult forces based on Hermetic ideas of attraction and repulsion between particles. John Maynard Keynes, who acquired many of Newton’s writings on alchemy, stated that «Newton was not the first of the age of reason: He was the last of the magicians.»[64] Newton’s contributions to science cannot be isolated from his interest in alchemy.[63] This was at a time when there was no clear distinction between alchemy and science, and had he not relied on the occult idea of action at a distance, across a vacuum, he might not have developed his theory of gravity.

In 1704, Newton published Opticks, in which he expounded his corpuscular theory of light. He considered light to be made up of extremely subtle corpuscles, that ordinary matter was made of grosser corpuscles and speculated that through a kind of alchemical transmutation «Are not gross Bodies and Light convertible into one another, … and may not Bodies receive much of their Activity from the Particles of Light which enter their Composition?»[65] Newton also constructed a primitive form of a frictional electrostatic generator, using a glass globe.[66]

In his book Opticks, Newton was the first to show a diagram using a prism as a beam expander, and also the use of multiple-prism arrays.[67] Some 278 years after Newton’s discussion, multiple-prism beam expanders became central to the development of narrow-linewidth tunable lasers. Also, the use of these prismatic beam expanders led to the multiple-prism dispersion theory.[67]

Subsequent to Newton, much has been amended. Young and Fresnel discarded Newton’s particle theory in favour of Huygens’ wave theory to show that colour is the visible manifestation of light’s wavelength. Science also slowly came to realise the difference between perception of colour and mathematisable optics. The German poet and scientist, Goethe, could not shake the Newtonian foundation but «one hole Goethe did find in Newton’s armour, … Newton had committed himself to the doctrine that refraction without colour was impossible. He, therefore, thought that the object-glasses of telescopes must forever remain imperfect, achromatism and refraction being incompatible. This inference was proved by Dollond to be wrong.»[68]

Gravity

In 1679, Newton returned to his work on celestial mechanics by considering gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets with reference to Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. This followed stimulation by a brief exchange of letters in 1679–80 with Hooke, who had been appointed to manage the Royal Society’s correspondence, and who opened a correspondence intended to elicit contributions from Newton to Royal Society transactions.[61] Newton’s reawakening interest in astronomical matters received further stimulus by the appearance of a comet in the winter of 1680–1681, on which he corresponded with John Flamsteed.[69] After the exchanges with Hooke, Newton worked out a proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector. Newton communicated his results to Edmond Halley and to the Royal Society in De motu corporum in gyrum, a tract written on about nine sheets which was copied into the Royal Society’s Register Book in December 1684.[70] This tract contained the nucleus that Newton developed and expanded to form the Principia.

The Principia was published on 5 July 1687 with encouragement and financial help from Halley. In this work, Newton stated the three universal laws of motion. Together, these laws describe the relationship between any object, the forces acting upon it and the resulting motion, laying the foundation for classical mechanics. They contributed to many advances during the Industrial Revolution which soon followed and were not improved upon for more than 200 years. Many of these advances continue to be the underpinnings of non-relativistic technologies in the modern world. He used the Latin word gravitas (weight) for the effect that would become known as gravity, and defined the law of universal gravitation.[71]

In the same work, Newton presented a calculus-like method of geometrical analysis using ‘first and last ratios’, gave the first analytical determination (based on Boyle’s law) of the speed of sound in air, inferred the oblateness of Earth’s spheroidal figure, accounted for the precession of the equinoxes as a result of the Moon’s gravitational attraction on the Earth’s oblateness, initiated the gravitational study of the irregularities in the motion of the Moon, provided a theory for the determination of the orbits of comets, and much more.[71] Newton’s biographer David Brewster reported that the complexity of applying his theory of gravity to the motion of the moon was so great it affected Newton’s health: «[H]e was deprived of his appetite and sleep» during his work on the problem in 1692-3, and told the astronomer John Machin that «his head never ached but when he was studying the subject». According to Brewster Edmund Halley also told John Conduitt that when pressed to complete his analysis Newton «always replied that it made his head ache, and kept him awake so often, that he would think of it no more«. [Emphasis in original][72]

Newton made clear his heliocentric view of the Solar System—developed in a somewhat modern way because already in the mid-1680s he recognised the «deviation of the Sun» from the centre of gravity of the Solar System.[73] For Newton, it was not precisely the centre of the Sun or any other body that could be considered at rest, but rather «the common centre of gravity of the Earth, the Sun and all the Planets is to be esteem’d the Centre of the World», and this centre of gravity «either is at rest or moves uniformly forward in a right line» (Newton adopted the «at rest» alternative in view of common consent that the centre, wherever it was, was at rest).[74]

Newton’s postulate of an invisible force able to act over vast distances led to him being criticised for introducing «occult agencies» into science.[75] Later, in the second edition of the Principia (1713), Newton firmly rejected such criticisms in a concluding General Scholium, writing that it was enough that the phenomena implied a gravitational attraction, as they did; but they did not so far indicate its cause, and it was both unnecessary and improper to frame hypotheses of things that were not implied by the phenomena. (Here Newton used what became his famous expression «hypotheses non-fingo»[76]).

With the Principia, Newton became internationally recognised.[77] He acquired a circle of admirers, including the Swiss-born mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier.[78]

In 1710, Newton found 72 of the 78 «species» of cubic curves and categorised them into four types.[79] In 1717, and probably with Newton’s help, James Stirling proved that every cubic was one of these four types. Newton also claimed that the four types could be obtained by plane projection from one of them, and this was proved in 1731, four years after his death.[80]

Later life

Royal Mint

In the 1690s, Newton wrote a number of religious tracts dealing with the literal and symbolic interpretation of the Bible. A manuscript Newton sent to John Locke in which he disputed the fidelity of 1 John 5:7—the Johannine Comma—and its fidelity to the original manuscripts of the New Testament, remained unpublished until 1785.[81]

Newton was also a member of the Parliament of England for Cambridge University in 1689 and 1701, but according to some accounts his only comments were to complain about a cold draught in the chamber and request that the window be closed.[82] He was, however, noted by Cambridge diarist Abraham de la Pryme to have rebuked students who were frightening locals by claiming that a house was haunted.[83]

Newton moved to London to take up the post of warden of the Royal Mint in 1696, a position that he had obtained through the patronage of Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax, then Chancellor of the Exchequer. He took charge of England’s great recoining, trod on the toes of Lord Lucas, Governor of the Tower, and secured the job of deputy comptroller of the temporary Chester branch for Edmond Halley. Newton became perhaps the best-known Master of the Mint upon the death of Thomas Neale in 1699, a position Newton held for the last 30 years of his life.[84][85] These appointments were intended as sinecures, but Newton took them seriously. He retired from his Cambridge duties in 1701, and exercised his authority to reform the currency and punish clippers and counterfeiters.

As Warden, and afterwards as Master, of the Royal Mint, Newton estimated that 20 percent of the coins taken in during the Great Recoinage of 1696 were counterfeit. Counterfeiting was high treason, punishable by the felon being hanged, drawn and quartered. Despite this, convicting even the most flagrant criminals could be extremely difficult, but Newton proved equal to the task.[86]

Disguised as a habitué of bars and taverns, he gathered much of that evidence himself.[87] For all the barriers placed to prosecution, and separating the branches of government, English law still had ancient and formidable customs of authority. Newton had himself made a justice of the peace in all the home counties. A draft letter regarding the matter is included in Newton’s personal first edition of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which he must have been amending at the time.[88] Then he conducted more than 100 cross-examinations of witnesses, informers, and suspects between June 1698 and Christmas 1699. Newton successfully prosecuted 28 coiners.[89]

Newton was made president of the Royal Society in 1703 and an associate of the French Académie des Sciences. In his position at the Royal Society, Newton made an enemy of John Flamsteed, the Astronomer Royal, by prematurely publishing Flamsteed’s Historia Coelestis Britannica, which Newton had used in his studies.[91]

Knighthood

In April 1705, Queen Anne knighted Newton during a royal visit to Trinity College, Cambridge. The knighthood is likely to have been motivated by political considerations connected with the parliamentary election in May 1705, rather than any recognition of Newton’s scientific work or services as Master of the Mint.[92] Newton was the second scientist to be knighted, after Francis Bacon.[93]

As a result of a report written by Newton on 21 September 1717 to the Lords Commissioners of His Majesty’s Treasury, the bimetallic relationship between gold coins and silver coins was changed by royal proclamation on 22 December 1717, forbidding the exchange of gold guineas for more than 21 silver shillings.[94] This inadvertently resulted in a silver shortage as silver coins were used to pay for imports, while exports were paid for in gold, effectively moving Britain from the silver standard to its first gold standard. It is a matter of debate as to whether he intended to do this or not.[95] It has been argued that Newton conceived of his work at the Mint as a continuation of his alchemical work.[96]

Newton was invested in the South Sea Company and lost some £20,000 (£4.4 million in 2020[97]) when it collapsed in around 1720.[98]

Toward the end of his life, Newton took up residence at Cranbury Park, near Winchester, with his niece and her husband, until his death.[99] His half-niece, Catherine Barton,[100] served as his hostess in social affairs at his house on Jermyn Street in London; he was her «very loving Uncle»,[101] according to his letter to her when she was recovering from smallpox.

Death

Newton died in his sleep in London on 20 March 1727 (OS 20 March 1726; NS 31 March 1727).[a] He was given a ceremonial funeral, attended by nobles, scientists, and philosophers, and was buried in Westminster Abbey among kings and queens. He is also the first scientist to be buried in the abbey.[102] Voltaire may have been present at his funeral.[103] A bachelor, he had divested much of his estate to relatives during his last years, and died intestate.[104] His papers went to John Conduitt and Catherine Barton.[105]

After his death, Newton’s hair was examined and found to contain mercury, probably resulting from his alchemical pursuits. Mercury poisoning could explain Newton’s eccentricity in late life.[104]

Personality

Although it was claimed that he was once engaged,[b] Newton never married. The French writer and philosopher Voltaire, who was in London at the time of Newton’s funeral, said that he «was never sensible to any passion, was not subject to the common frailties of mankind, nor had any commerce with women—a circumstance which was assured me by the physician and surgeon who attended him in his last moments».[107] There exists a widespread belief that Newton died a virgin, and writers as diverse as mathematician Charles Hutton,[108] economist John Maynard Keynes,[109] and physicist Carl Sagan each have commented on it.[110]

Newton had a close friendship with the Swiss mathematician Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, who he met in London around 1689[78]—some of their correspondence has survived.[111][112] Their relationship came to an abrupt and unexplained end in 1693, and at the same time Newton suffered a nervous breakdown,[113] which included sending wild accusatory letters to his friends Samuel Pepys and John Locke. His note to the latter included the charge that Locke «endeavoured to embroil me with woemen».[114]

Newton was relatively modest about his achievements, writing in a letter to Robert Hooke in February 1676, «If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.»[115] Two writers think that the sentence, written at a time when Newton and Hooke were in dispute over optical discoveries, was an oblique attack on Hooke (said to have been short and hunchbacked), rather than—or in addition to—a statement of modesty.[116][117] On the other hand, the widely known proverb about standing on the shoulders of giants, published among others by seventeenth-century poet George Herbert (a former orator of the University of Cambridge and fellow of Trinity College) in his Jacula Prudentum (1651), had as its main point that «a dwarf on a giant’s shoulders sees farther of the two», and so its effect as an analogy would place Newton himself rather than Hooke as the ‘dwarf’.

In a later memoir, Newton wrote, «I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea-shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.»[118]

In 2015, Steven Weinberg, a Nobel laureate in physics, called Newton «a nasty antagonist» and «a bad man to have as an enemy»,[119] noting Newton’s attitude towards Robert Hooke and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

It has been suggested by some scientists and clinicians that, based on these and other traits along with his profound power of concentration, that Newton may have had an undiagnosed form of high-functioning autism, now properly known as ASD1 within autism spectrum; formerly known as Asperger syndrome.[120][121][122]

Theology

Religious views

Although born into an Anglican family, by his thirties Newton held a Christian faith that, had it been made public, would not have been considered orthodox by mainstream Christianity,[123] with one historian labelling him a heretic.[124]

By 1672, he had started to record his theological researches in notebooks which he showed to no one and which have only recently[when?] been examined. They demonstrate an extensive knowledge of early Church writings and show that in the conflict between Athanasius and Arius which defined the Creed, he took the side of Arius, the loser, who rejected the conventional view of the Trinity. Newton «recognized Christ as a divine mediator between God and man, who was subordinate to the Father who created him.»[125] He was especially interested in prophecy, but for him, «the great apostasy was trinitarianism.»[126]

Newton tried unsuccessfully to obtain one of the two fellowships that exempted the holder from the ordination requirement. At the last moment in 1675 he received a dispensation from the government that excused him and all future holders of the Lucasian chair.[127]

In Newton’s eyes, worshipping Christ as God was idolatry, to him the fundamental sin.[128] In 1999, historian Stephen D. Snobelen wrote, «Isaac Newton was a heretic. But … he never made a public declaration of his private faith—which the orthodox would have deemed extremely radical. He hid his faith so well that scholars are still unraveling his personal beliefs.»[124] Snobelen concludes that Newton was at least a Socinian sympathiser (he owned and had thoroughly read at least eight Socinian books), possibly an Arian and almost certainly an anti-trinitarian.[124]

The view that Newton was Semi-Arian has lost support now that scholars have investigated Newton’s theological papers, and now most scholars identify Newton as an Antitrinitarian monotheist.[124][129]

Although the laws of motion and universal gravitation became Newton’s best-known discoveries, he warned against using them to view the Universe as a mere machine, as if akin to a great clock. He said, «So then gravity may put the planets into motion, but without the Divine Power it could never put them into such a circulating motion, as they have about the sun».[131]

Along with his scientific fame, Newton’s studies of the Bible and of the early Church Fathers were also noteworthy. Newton wrote works on textual criticism, most notably An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture and Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel, and the Apocalypse of St. John.[132] He placed the crucifixion of Jesus Christ at 3 April, AD 33, which agrees with one traditionally accepted date.[133]

He believed in a rationally immanent world, but he rejected the hylozoism implicit in Leibniz and Baruch Spinoza. The ordered and dynamically informed Universe could be understood, and must be understood, by an active reason. In his correspondence, Newton claimed that in writing the Principia «I had an eye upon such Principles as might work with considering men for the belief of a Deity».[134] He saw evidence of design in the system of the world: «Such a wonderful uniformity in the planetary system must be allowed the effect of choice». But Newton insisted that divine intervention would eventually be required to reform the system, due to the slow growth of instabilities.[135] For this, Leibniz lampooned him: «God Almighty wants to wind up his watch from time to time: otherwise it would cease to move. He had not, it seems, sufficient foresight to make it a perpetual motion.»[136]

Newton’s position was vigorously defended by his follower Samuel Clarke in a famous correspondence. A century later, Pierre-Simon Laplace’s work Celestial Mechanics had a natural explanation for why the planet orbits do not require periodic divine intervention.[137] The contrast between Laplace’s mechanistic worldview and Newton’s one is the most strident considering the famous answer which the French scientist gave Napoleon, who had criticised him for the absence of the Creator in the Mécanique céleste: «Sire, j’ai pu me passer de cette hypothèse» («Sir, I didn’t need this hypothesis»).[138]

Scholars long debated whether Newton disputed the doctrine of the Trinity. His first biographer, David Brewster, who compiled his manuscripts, interpreted Newton as questioning the veracity of some passages used to support the Trinity, but never denying the doctrine of the Trinity as such.[139] In the twentieth century, encrypted manuscripts written by Newton and bought by John Maynard Keynes (among others) were deciphered[64] and it became known that Newton did indeed reject Trinitarianism.[124]

Religious thought

Newton and Robert Boyle’s approach to the mechanical philosophy was promoted by rationalist pamphleteers as a viable alternative to the pantheists and enthusiasts, and was accepted hesitantly by orthodox preachers as well as dissident preachers like the latitudinarians.[140] The clarity and simplicity of science was seen as a way to combat the emotional and metaphysical superlatives of both superstitious enthusiasm and the threat of atheism,[141] and at the same time, the second wave of English deists used Newton’s discoveries to demonstrate the possibility of a «Natural Religion».

The attacks made against pre-Enlightenment «magical thinking», and the mystical elements of Christianity, were given their foundation with Boyle’s mechanical conception of the universe. Newton gave Boyle’s ideas their completion through mathematical proofs and, perhaps more importantly, was very successful in popularising them.[142]

The occult

In a manuscript he wrote in 1704 (never intended to be published), he mentions the date of 2060, but it is not given as a date for the end of days. It has been falsely reported as a prediction.[143] The passage is clear when the date is read in context. He was against date setting for the end of days, concerned that this would put Christianity into disrepute.

So then the time times & half a time [sic] are 42 months or 1260 days or three years & an half, recconing twelve months to a year & 30 days to a month as was done in the Calender [sic] of the primitive year. And the days of short lived Beasts being put for the years of [long-]lived kingdoms the period of 1260 days, if dated from the complete conquest of the three kings A.C. 800, will end 2060. It may end later, but I see no reason for its ending sooner.[144]

This I mention not to assert when the time of the end shall be, but to put a stop to the rash conjectures of fanciful men who are frequently predicting the time of the end, and by doing so bring the sacred prophesies into discredit as often as their predictions fail. Christ comes as a thief in the night, and it is not for us to know the times and seasons which God hath put into his own breast.[145][143]

Alchemy

In the character of Morton Opperly in «Poor Superman» (1951), speculative fiction author Fritz Leiber says of Newton, «Everyone knows Newton as the great scientist. Few remember that he spent half his life muddling with alchemy, looking for the philosopher’s stone. That was the pebble by the seashore he really wanted to find.»[146]

Of an estimated ten million words of writing in Newton’s papers, about one million deal with alchemy. Many of Newton’s writings on alchemy are copies of other manuscripts, with his own annotations.[105] Alchemical texts mix artisanal knowledge with philosophical speculation, often hidden behind layers of wordplay, allegory, and imagery to protect craft secrets.[147] Some of the content contained in Newton’s papers could have been considered heretical by the church.[105]

In 1888, after spending sixteen years cataloguing Newton’s papers, Cambridge University kept a small number and returned the rest to the Earl of Portsmouth. In 1936, a descendant offered the papers for sale at Sotheby’s.[148] The collection was broken up and sold for a total of about £9,000.[149] John Maynard Keynes was one of about three dozen bidders who obtained part of the collection at auction. Keynes went on to reassemble an estimated half of Newton’s collection of papers on alchemy before donating his collection to Cambridge University in 1946.[105][148][150]

All of Newton’s known writings on alchemy are currently being put online in a project undertaken by Indiana University: «The Chymistry of Isaac Newton»[151] and summarised in a book.[152][153]

Newton’s fundamental contributions to science include the quantification of gravitational attraction, the discovery that white light is actually a mixture of immutable spectral colors, and the formulation of the calculus. Yet there is another, more mysterious side to Newton that is imperfectly known, a realm of activity that spanned some thirty years of his life, although he kept it largely hidden from his contemporaries and colleagues. We refer to Newton’s involvement in the discipline of alchemy, or as it was often called in seventeenth-century England, «chymistry.»[151]

Charles Coulston Gillispie disputes that Newton ever practised alchemy, saying that «his chemistry was in the spirit of Boyle’s corpuscular philosophy.»[154]

In June 2020, two unpublished pages of Newton’s notes on Jan Baptist van Helmont’s book on plague, De Peste,[155] were being auctioned online by Bonhams. Newton’s analysis of this book, which he made in Cambridge while protecting himself from London’s 1665–1666 infection, is the most substantial written statement he is known to have made about the plague, according to Bonhams. As far as the therapy is concerned, Newton writes that «the best is a toad suspended by the legs in a chimney for three days, which at last vomited up earth with various insects in it, on to a dish of yellow wax, and shortly after died. Combining powdered toad with the excretions and serum made into lozenges and worn about the affected area drove away the contagion and drew out the poison».[156]

Legacy

Fame

The mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange said that Newton was the greatest genius who ever lived, and once added that Newton was also «the most fortunate, for we cannot find more than once a system of the world to establish.»[157] English poet Alexander Pope wrote the famous epitaph:

Nature, and Nature’s laws lay hid in night.

God said, Let Newton be! and all was light.

But this was not allowed to be inscribed in the monument. The epitaph in the monument is as follows:[158]

H. S. E. ISAACUS NEWTON Eques Auratus, / Qui, animi vi prope divinâ, / Planetarum Motus, Figuras, / Cometarum semitas, Oceanique Aestus. Suâ Mathesi facem praeferente / Primus demonstravit: / Radiorum Lucis dissimilitudines, / Colorumque inde nascentium proprietates, / Quas nemo antea vel suspicatus erat, pervestigavit. / Naturae, Antiquitatis, S. Scripturae, / Sedulus, sagax, fidus Interpres / Dei O. M. Majestatem Philosophiâ asseruit, / Evangelij Simplicitatem Moribus expressit. / Sibi gratulentur Mortales, / Tale tantumque exstitisse / HUMANI GENERIS DECUS. / NAT. XXV DEC. A.D. MDCXLII. OBIIT. XX. MAR. MDCCXXVI,

which can be translated as follows:[158]

Here is buried Isaac Newton, Knight, who by a strength of mind almost divine, and mathematical principles peculiarly his own, explored the course and figures of the planets, the paths of comets, the tides of the sea, the dissimilarities in rays of light, and, what no other scholar has previously imagined, the properties of the colours thus produced. Diligent, sagacious and faithful, in his expositions of nature, antiquity and the holy Scriptures, he vindicated by his philosophy the majesty of God mighty and good, and expressed the simplicity of the Gospel in his manners. Mortals rejoice that there has existed such and so great an ornament of the human race! He was born on 25th December 1642, and died on 20th March 1726.

In a 2005 survey of members of Britain’s Royal Society (formerly headed by Newton) asking who had the greater effect on the history of science, Newton or Albert Einstein, the members deemed Newton to have made the greater overall contribution.[159] In 1999, an opinion poll of 100 of the day’s leading physicists voted Einstein the «greatest physicist ever,» with Newton the runner-up, while a parallel survey of rank-and-file physicists by the site PhysicsWeb gave the top spot to Newton.[160] Einstein kept a picture of Newton on his study wall alongside ones of Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell.[161]

The SI derived unit of force is named the newton in his honour.

Woolsthorpe Manor is a Grade I listed building by Historic England through being his birthplace and «where he discovered gravity and developed his theories regarding the refraction of light».[162]

In 1816, a tooth said to have belonged to Newton was sold for £730[163] (US$3,633) in London to an aristocrat who had it set in a ring.[164] Guinness World Records 2002 classified it as the most valuable tooth, which would value approximately £25,000 (US$35,700) in late 2001.[164] Who bought it and who currently has it has not been disclosed.

Apple incident

Newton himself often told the story that he was inspired to formulate his theory of gravitation by watching the fall of an apple from a tree.[165][166] The story is believed to have passed into popular knowledge after being related by Catherine Barton, Newton’s niece, to Voltaire.[167] Voltaire then wrote in his Essay on Epic Poetry (1727), «Sir Isaac Newton walking in his gardens, had the first thought of his system of gravitation, upon seeing an apple falling from a tree.»[168][169]

Although it has been said that the apple story is a myth and that he did not arrive at his theory of gravity at any single moment,[170] acquaintances of Newton (such as William Stukeley, whose manuscript account of 1752 has been made available by the Royal Society) do in fact confirm the incident, though not the apocryphal version that the apple actually hit Newton’s head. Stukeley recorded in his Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton’s Life a conversation with Newton in Kensington on 15 April 1726:[171][172][173]

we went into the garden, & drank thea under the shade of some appletrees, only he, & myself. amidst other discourse, he told me, he was just in the same situation, as when formerly, the notion of gravitation came into his mind. «why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground,» thought he to him self: occasion’d by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a comtemplative mood: «why should it not go sideways, or upwards? but constantly to the earths centre? assuredly, the reason is, that the earth draws it. there must be a drawing power in matter. & the sum of the drawing power in the matter of the earth must be in the earths center, not in any side of the earth. therefore dos this apple fall perpendicularly, or toward the center. if matter thus draws matter; it must be in proportion of its quantity. therefore the apple draws the earth, as well as the earth draws the apple.»

John Conduitt, Newton’s assistant at the Royal Mint and husband of Newton’s niece, also described the event when he wrote about Newton’s life:[174]

In the year 1666 he retired again from Cambridge to his mother in Lincolnshire. Whilst he was pensively meandering in a garden it came into his thought that the power of gravity (which brought an apple from a tree to the ground) was not limited to a certain distance from earth, but that this power must extend much further than was usually thought. Why not as high as the Moon said he to himself & if so, that must influence her motion & perhaps retain her in her orbit, whereupon he fell a calculating what would be the effect of that supposition.

It is known from his notebooks that Newton was grappling in the late 1660s with the idea that terrestrial gravity extends, in an inverse-square proportion, to the Moon; however, it took him two decades to develop the full-fledged theory.[175] The question was not whether gravity existed, but whether it extended so far from Earth that it could also be the force holding the Moon to its orbit. Newton showed that if the force decreased as the inverse square of the distance, one could indeed calculate the Moon’s orbital period, and get good agreement. He guessed the same force was responsible for other orbital motions, and hence named it «universal gravitation».

Various trees are claimed to be «the» apple tree which Newton describes. The King’s School, Grantham claims that the tree was purchased by the school, uprooted and transported to the headmaster’s garden some years later. The staff of the (now) National Trust-owned Woolsthorpe Manor dispute this, and claim that a tree present in their gardens is the one described by Newton. A descendant of the original tree[176] can be seen growing outside the main gate of Trinity College, Cambridge, below the room Newton lived in when he studied there. The National Fruit Collection at Brogdale in Kent[177] can supply grafts from their tree, which appears identical to Flower of Kent, a coarse-fleshed cooking variety.[178]

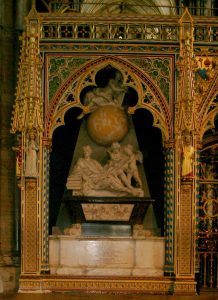

Commemorations

Newton’s monument (1731) can be seen in Westminster Abbey, at the north of the entrance to the choir against the choir screen, near his tomb. It was executed by the sculptor Michael Rysbrack (1694–1770) in white and grey marble with design by the architect William Kent.[179] The monument features a figure of Newton reclining on top of a sarcophagus, his right elbow resting on several of his great books and his left hand pointing to a scroll with a mathematical design. Above him is a pyramid and a celestial globe showing the signs of the Zodiac and the path of the comet of 1680. A relief panel depicts putti using instruments such as a telescope and prism.[180] The Latin inscription on the base translates as:

Here is buried Isaac Newton, Knight, who by a strength of mind almost divine, and mathematical principles peculiarly his own, explored the course and figures of the planets, the paths of comets, the tides of the sea, the dissimilarities in rays of light, and, what no other scholar has previously imagined, the properties of the colours thus produced. Diligent, sagacious and faithful, in his expositions of nature, antiquity and the holy Scriptures, he vindicated by his philosophy the majesty of God mighty and good, and expressed the simplicity of the Gospel in his manners. Mortals rejoice that there has existed such and so great an ornament of the human race! He was born on 25 December 1642, and died on 20 March 1726/7.

- —Translation from G. L. Smyth, The Monuments and Genii of St. Paul’s Cathedral, and of Westminster Abbey (1826), ii, 703–704.[180]

From 1978 until 1988, an image of Newton designed by Harry Ecclestone appeared on Series D £1 banknotes issued by the Bank of England (the last £1 notes to be issued by the Bank of England). Newton was shown on the reverse of the notes holding a book and accompanied by a telescope, a prism and a map of the Solar System.[181]

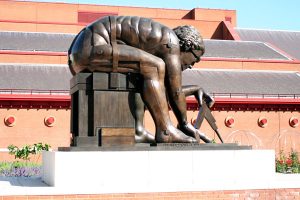

A statue of Isaac Newton, looking at an apple at his feet, can be seen at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. A large bronze statue, Newton, after William Blake, by Eduardo Paolozzi, dated 1995 and inspired by Blake’s etching, dominates the piazza of the British Library in London. A bronze statue of Newton was erected in 1858 in the centre of Grantham where he went to school, prominently standing in front of Grantham Guildhall.

The still-surviving farmhouse at Woolsthorpe By Colsterworth is a Grade I listed building by Historic England through being his birthplace and «where he discovered gravity and developed his theories regarding the refraction of light».[162]

The Enlightenment

Enlightenment philosophers chose a short history of scientific predecessors—Galileo, Boyle, and Newton principally—as the guides and guarantors of their applications of the singular concept of nature and natural law to every physical and social field of the day. In this respect, the lessons of history and the social structures built upon it could be discarded.[182]

It is held by European philosophers of the Enlightenment and by historians of the Enlightenment that Newton’s publication of the Principia was a turning point in the Scientific Revolution and started the Enlightenment. It was Newton’s conception of the universe based upon natural and rationally understandable laws that became one of the seeds for Enlightenment ideology.[183] Locke and Voltaire applied concepts of natural law to political systems advocating intrinsic rights; the physiocrats and Adam Smith applied natural conceptions of psychology and self-interest to economic systems; and sociologists criticised the current social order for trying to fit history into natural models of progress. Monboddo and Samuel Clarke resisted elements of Newton’s work, but eventually rationalised it to conform with their strong religious views of nature.

Works

Published in his lifetime

- De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas (1669, published 1711)[184]

- Of Natures Obvious Laws & Processes in Vegetation (unpublished, c. 1671–75)[185]

- De motu corporum in gyrum (1684)[186]

- Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687)[187]

- Scala graduum Caloris. Calorum Descriptiones & signa (1701)[188]

- Opticks (1704)[189]

- Reports as Master of the Mint (1701–1725)[190]

- Arithmetica Universalis (1707)[190]

Published posthumously

- De mundi systemate (The System of the World) (1728)[190]

- Optical Lectures (1728)[190]

- The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (1728)[190]

- Observations on Daniel and The Apocalypse of St. John (1733)[190]

- Method of Fluxions (1671, published 1736)[191]

- An Historical Account of Two Notable Corruptions of Scripture (1754)[190]

See also

- Elements of the Philosophy of Newton, a book by Voltaire

- List of multiple discoveries: seventeenth century

- List of things named after Isaac Newton

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e During Newton’s lifetime, two calendars were in use in Europe: the Julian («Old Style») calendar in Protestant and Orthodox regions, including Britain; and the Gregorian («New Style») calendar in Roman Catholic Europe. At Newton’s birth, Gregorian dates were ten days ahead of Julian dates; thus, his birth is recorded as taking place on 25 December 1642 Old Style, but it can be converted to a New Style (modern) date of 4 January 1643. By the time of his death, the difference between the calendars had increased to eleven days. Moreover, he died in the period after the start of the New Style year on 1 January but before that of the Old Style new year on 25 March. His death occurred on 20 March 1726, according to the Old Style calendar, but the year is usually adjusted to 1727. A full conversion to New Style gives the date 31 March 1727.[1]

- ^ This claim was made by William Stukeley in 1727, in a letter about Newton written to Richard Mead. Charles Hutton, who in the late eighteenth century collected oral traditions about earlier scientists, declared that there «do not appear to be any sufficient reason for his never marrying, if he had an inclination so to do. It is much more likely that he had a constitutional indifference to the state, and even to the sex in general.»[106]

Citations

- ^ Thony, Christie (2015). «Calendrical confusion or just when did Newton die?». The Renaissance Mathematicus. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Kevin C. Knox, Richard Noakes (eds.), From Newton to Hawking: A History of Cambridge University’s Lucasian Professors of Mathematics, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 61.

- ^ a b «Fellows of the Royal Society». London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- ^ Feingold, Mordechai. Barrow, Isaac (1630–1677) Archived 29 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, May 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2009; explained further in Feingold, Mordechai (1993). «Newton, Leibniz, and Barrow Too: An Attempt at a Reinterpretation». Isis. 84 (2): 310–338. Bibcode:1993Isis…84..310F. doi:10.1086/356464. JSTOR 236236. S2CID 144019197.

- ^ «Dictionary of Scientific Biography». Notes, No. 4. Archived from the original on 25 February 2005.

- ^ Gjertsen 1986, p. [page needed]

- ^ Newton, Isaac (February 1678). Philosophical tract from Mr Isaac Newton. Cambridge University. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

But because I am indebted to you & yesterday met with a friend Mr Maulyverer, who told me he was going to London & intended to give you the trouble of a visit, I could not forbear to take the opportunity of conveying this to you by him.

- ^ I. Bernard Cohen; George E. Smith (25 April 2002). The Cambridge Companion to Newton. Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-521-65696-2. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Niccolò Guicciardini (2009). Isaac Newton on mathematical certainty and method. MIT Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-262-01317-8. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ a b Ducheyne, Steffen (2009). «The Flow of Influence from Newton to Locke… and Back». Rivista di Storia della Filosofia (1984–). 64 (2): 245–268. doi:10.3280/SF2009-002001. ISSN 0393-2516. JSTOR 44024132. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ a b Rogers, G. A. J. (1978). «Locke’s Essay and Newton’s Principia». Journal of the History of Ideas. 39 (2): 217–232. doi:10.2307/2708776. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2708776. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ «Isaac Newton: «Judaic monotheist of the school of Maimonides»«. Achgut.com. 19 June 2007. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ See e.g. D. T. Whiteside, Before the Principia, in Journal for the History of Astronomy 1 (1970), 5–17, p. 7.

- ^ Jeremy Jennings. Revolution and the Republic: A History of Political Thought in France Since the Eighteenth Century. Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 347.

- ^ Bruni, Luigino; Porta, Pier Luigi (2003). «Economia Civile and Pubblica Felicità in the Italian Enlightenment». History of Political Economy. 35 (Suppl. 1): 361–385 (365). doi:10.1215/00182702-35-Suppl_1-361. S2CID 143538016.

- ^ Pearson, Roger (2005). Voltaire almighty : a life in pursuit of freedom. Internet Archive. New York : Bloomsbury : Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-58234-630-4.

- ^ «Isaac Newton, horoscope for birth date 25 December 1642 Jul.Cal». Astro-Databank Wiki. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Storr, Anthony (December 1985). «Isaac Newton». British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition). 291 (6511): 1779–1784. doi:10.1136/bmj.291.6511.1779. JSTOR 29521701. PMC 1419183. PMID 3936583.

- ^ Keynes, Milo (20 September 2008). «Balancing Newton’s Mind: His Singular Behaviour and His Madness of 1692–93». Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 62 (3): 289–300. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2007.0025. JSTOR 20462679. PMID 19244857.

- ^ Westfall 1980, p. 55.

- ^ «Newton the Mathematician» Z. Bechler, ed., Contemporary Newtonian Research(Dordrecht 1982) pp. 110–111

- ^ Westfall 1994, pp. 16–19.

- ^ White 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Westfall 1980, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Westfall 1980, pp. 71, 103.

- ^ Hoskins, Michael, ed. (1997). Cambridge Illustrated History of Astronomy. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-521-41158-5.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. «Waste Book». Cambridge University Digital Library. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ «Newton, Isaac (NWTN661I)». A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Westfall 1980, p. 178.

- ^ Westfall 1980, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Ball 1908, p. 319.

- ^ Whiteside, D.T., ed. (1967). «Part 7: The October 1666 Tract on Fluxions». The Mathematical Papers of Isaac Newton. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 400. Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Gjertsen 1986, p. 149.

- ^ Newton, Principia, 1729 English translation, p. 41 Archived 3 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Newton, Principia, 1729 English translation, p. 54 Archived 3 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Newton, Sir Isaac (1850). Newton’s Principia: The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. Geo. P. Putnam. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Clifford Truesdell, Essays in the History of Mechanics (1968), p. 99.

- ^ In the preface to the Marquis de L’Hospital’s Analyse des Infiniment Petits (Paris, 1696).

- ^ Starting with De motu corporum in gyrum, see also (Latin) Theorem 1 Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Whiteside, D.T., ed. (1970). «The Mathematical principles underlying Newton’s Principia Mathematica». Journal for the History of Astronomy. 1. Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–138.

- ^ Stewart 2009, p. 107.

- ^ Westfall 1980, pp. 538–539.

- ^ Stern, Keith (2009). Queers in history : the comprehensive encyclopedia of historical gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgenders. Dallas, Tex.: BenBella. ISBN 978-1-933771-87-8. OCLC 317453194.

- ^ Nowlan, Robert (2017). Masters of Mathematics: The Problems They Solved, Why These Are Important, and What You Should Know about Them. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. p. 136. ISBN 978-94-6300-891-4.

- ^ Ball 1908, p. 356.

- ^ Błaszczyk, P.; et al. (March 2013). «Ten misconceptions from the history of analysis and their debunking». Foundations of Science. 18 (1): 43–74. arXiv:1202.4153. doi:10.1007/s10699-012-9285-8. S2CID 119134151.

- ^ Westfall 1980, p. 179.

- ^ White 1997, p. 151.

- ^ King, Henry C (2003). The History of the Telescope. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-486-43265-6.

- ^ Whittaker, E.T., A History of the Theories of Aether and Electricity, Dublin University Press, 1910.

- ^ Olivier Darrigol (2012). A History of Optics from Greek Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-964437-7.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. «Hydrostatics, Optics, Sound and Heat». Cambridge University Digital Library. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Ball 1908, p. 324.

- ^ William R. Newman, «Newton’s Early Optical Theory and its Debt to Chymistry», in Danielle Jacquart and Michel Hochmann, eds., Lumière et vision dans les sciences et dans les arts (Geneva: Droz, 2010), pp. 283–307. A free access online version of this article can be found at the Chymistry of Isaac Newton project Archived 28 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine (PDF)

- ^ Ball 1908, p. 325.

- ^ «The Early Period (1608–1672)». James R. Graham’s Home Page. Retrieved 3 February 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b White 1997, p. 170

- ^ Hall, Alfred Rupert (1996). Isaac Newton: adventurer in thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-521-56669-8. OCLC 606137087.

This is the one dated 23 February 1669, in which Newton described his first reflecting telescope, constructed (it seems) near the close of the previous year.

- ^ White 1997, p. 168.

- ^ Newton, Isaac. «Of Colours». The Newton Project. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ a b See ‘Correspondence of Isaac Newton, vol. 2, 1676–1687’ ed. H.W. Turnbull, Cambridge University Press 1960; at p. 297, document No. 235, letter from Hooke to Newton dated 24 November 1679.

- ^ Iliffe, Robert (2007) Newton. A very short introduction, Oxford University Press 2007

- ^ a b Westfall, Richard S. (1983) [1980]. Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 530–531. ISBN 978-0-521-27435-7.

- ^ a b Keynes, John Maynard (1972). «Newton, The Man». The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes Volume X. MacMillan St. Martin’s Press. pp. 363–366.

- ^ Dobbs, J.T. (December 1982). «Newton’s Alchemy and His Theory of Matter». Isis. 73 (4): 523. doi:10.1086/353114. S2CID 170669199. quoting Opticks

- ^ Opticks, 2nd Ed 1706. Query 8.