Древний Египет — цивилизация, существовавшая с IV тыс. до н.э. до IV в. до н.э. Государство располагалось в Северо-Восточной Африке, в долине нижнего течения реки Нил. Древний Египет стал колыбелью высокоразвитой культуры, в дальнейшем оказавшей большое влияние на мировое искусство.

Особенности искусства.

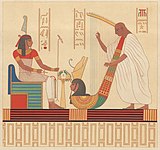

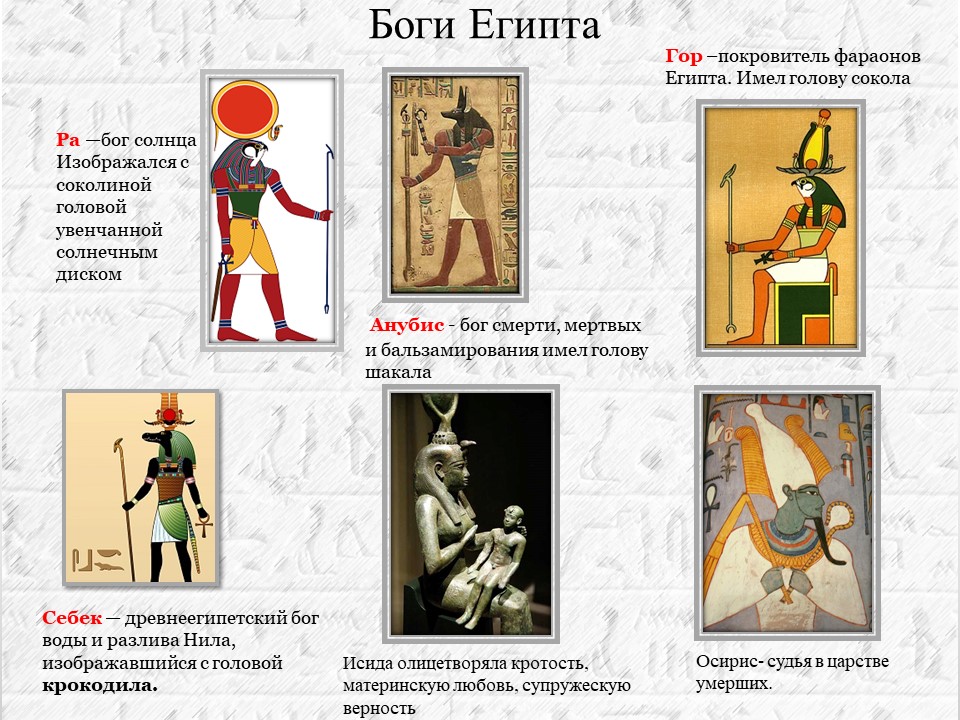

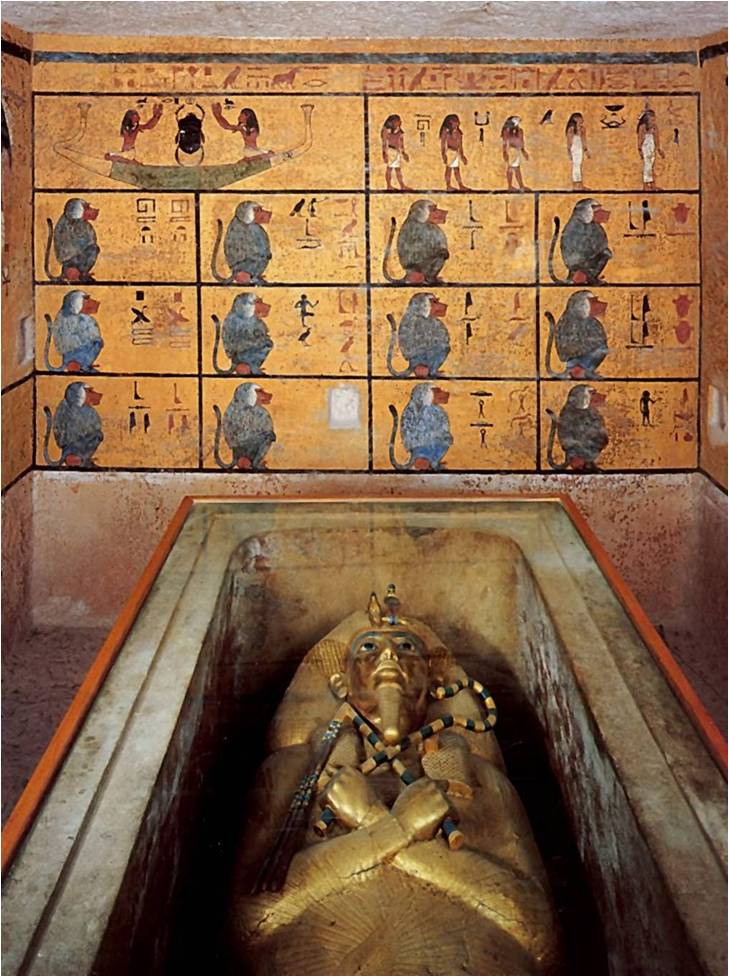

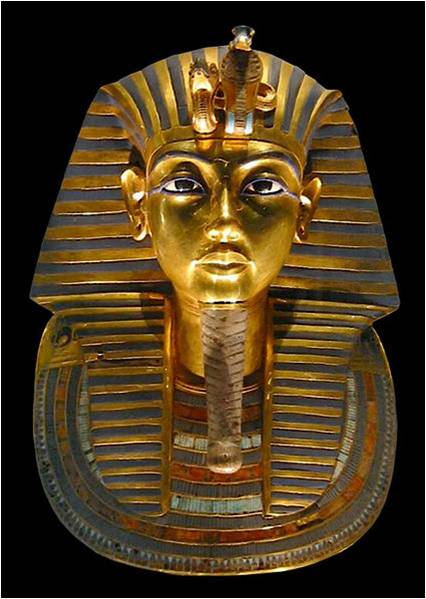

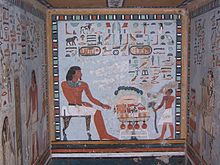

Особенности искусства Египта тесно связаны с религией и мифологией того времени. Египтяне поклонялись различным божествам и верили в загробную жизнь. Считалось, что жизнь продолжается после смерти, если сохранить тело человека и его изображения. Поэтому скульптуры и живопись, изображающие людей, считались чем-то магическим. Даже само слово «художник» означало «творящий жизнь». В таких произведениях уделялось большое внимание портретному сходству и особенно изображению глаз и губ. Так же было важно обеспечить загробную жизнь всем необходимым. Для этого строили гробницы и украшали их богатой росписью, как символом изобилия и благополучия.

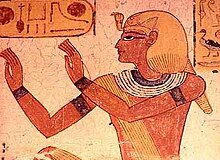

На протяжении всей своей истории, искусство Древнего Египта сохранило общую стилистику, следуя определённым правилам — канонам. Таким, как сочетание разных ракурсов (анфас и профиль) в одном изображении, схематическое изображение предметов, стандартные позы статуй фараонов. Эти традиции сформировались во время Древнего царства, которое, в представлении египтян, было эпохой порядка, установленного богами. В итоге, все предметы искусства того периода стали священным образцом для подражания.

Монументальность (массивность и величественность) — яркая особенность древнеегипетской скульптуры и архитектуры. Она была символом величия государства и фараона.

Периоды искусства Древнего Египта.

Принято выделять 3 периода развития древнеегипетского искусства.

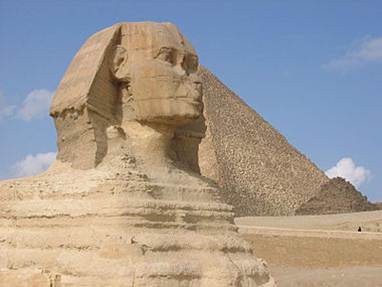

- Искусство Древнего царства (XXXII — XXIV вв. до н. э.). В этот период на основе религиозных верований и ритуалов сформировались основные каноны создания предметов искусства. Именно в это время построены Великие Пирамиды и Большой Сфинкс.

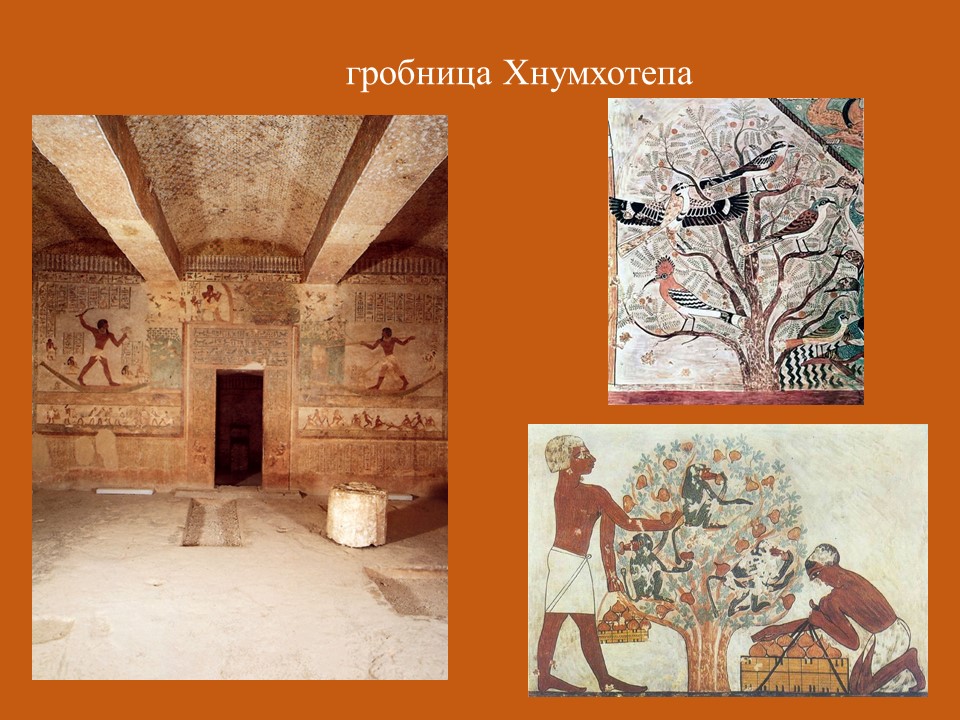

- Искусство Среднего царства (XXI — XVIII вв. до н. э.). В эту эпоху власть фараона уже не считается божественной, появляется идея равенства после смерти. В результате изображения фараонов становятся более реалистичными, а гробницы упрощаются. Появляется новая форма захоронения — гробница, высеченная прямо в скале. Слабая центральная власть приводит к разобщению областей. В каждой из них самостоятельно развиваются разные художественные школы, появляется больше индивидуальности и разнообразия в искусстве.

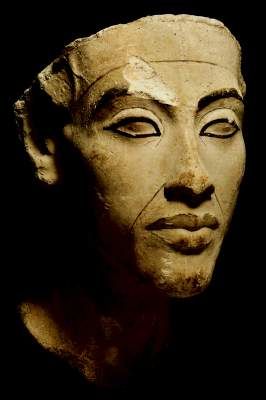

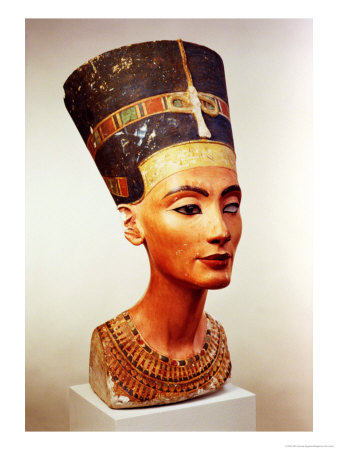

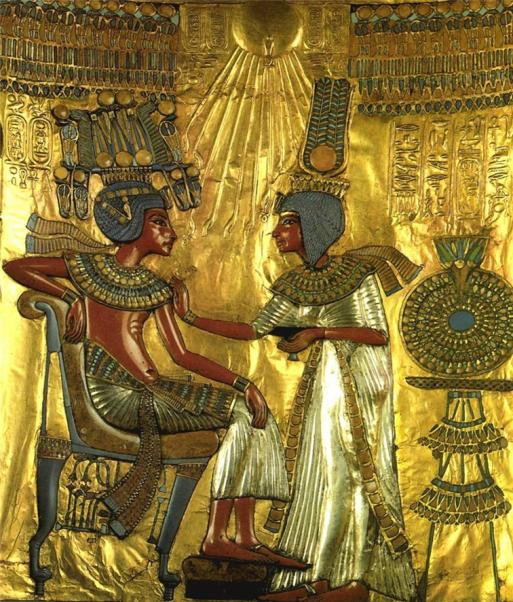

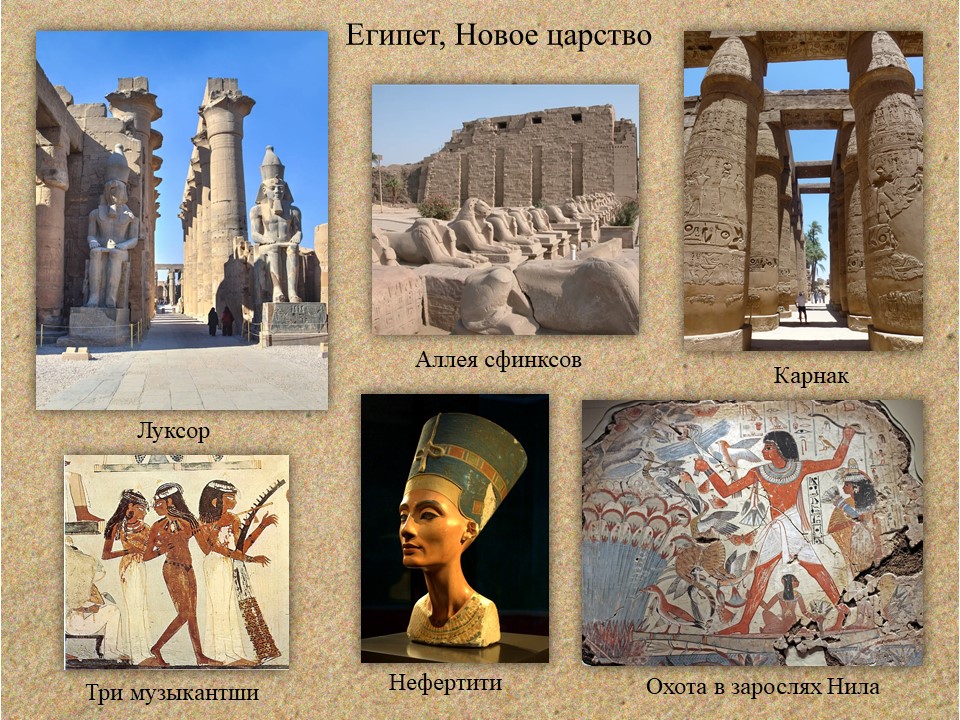

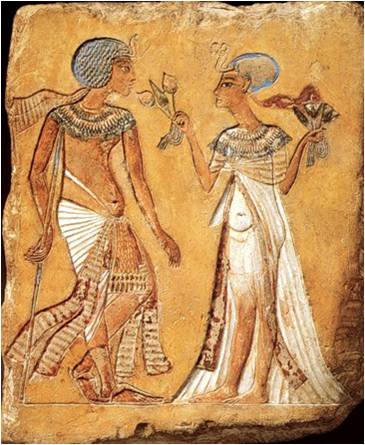

- Искусство Нового царства (XVII —XI вв. до н. э.). Это время расцвета вновь единого и сильного Египетского царства. Все произведения искусства этого периода свидетельствуют о благополучии, процветании и величии. Архитектура снова становится монументальной, но вместо гробниц возводят величественные храмы. Скульптуры, живопись и рельефы отличаются изысканностью, художники стараются передать движение и эмоции в своих работах. Активно развивается декоративно-прикладное искусство — домашняя утварь и украшения того времени выполнены с большим изяществом. В этом периоде нужно уделить особое внимание правлению фараона Эхнатона. Именно в эти годы каноны искусства уступили реалистичности. Появились изображения фараона в бытовых сценах — за едой, во время общения с семьёй. Впервые стали изображать жену фараона отдельно от мужа. Стала развиваться литература — кроме гимнов во славу богам, обнаружено достаточно много любовной лирики того периода.

Виды искусства Древнего Египта.

Архитектура.

Самые значимые строения Древнего Египта это усыпальницы, дворцы и храмы. Главным материалом архитекторов Египта был камень и кирпич-сырец. Архитектурные формы были массивными, строго геометричными и однообразными. Чаще всего использовались формы пирамид, колонн и пилонов (усечённые пирамиды).

Скульптура.

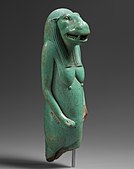

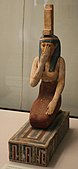

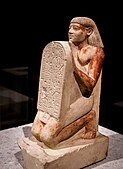

Древнеегипетские изваяния изображали богов и фараонов. Изваяния имели магическое значение, олицетворяли сущность человека. Все скульптуры создавались по сложившимся правилам — симметричными, в традиционных позах, с обязательным портретным сходством.

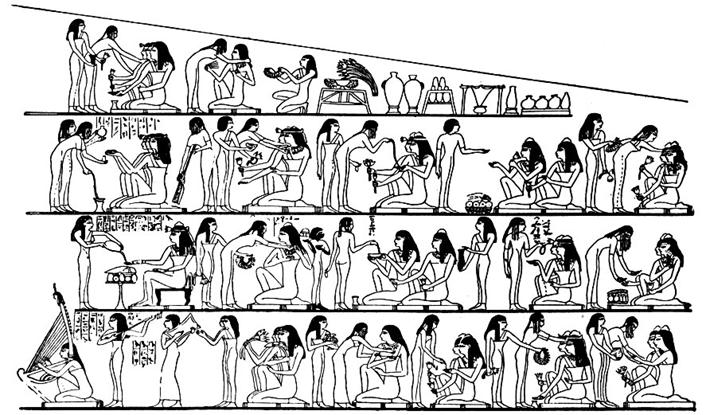

Живопись.

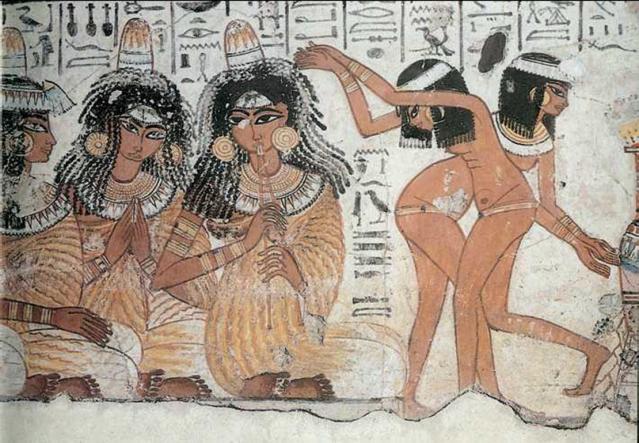

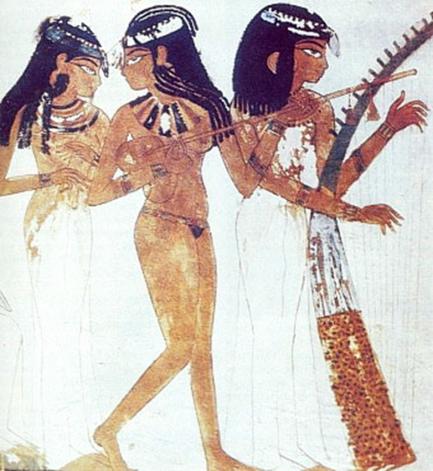

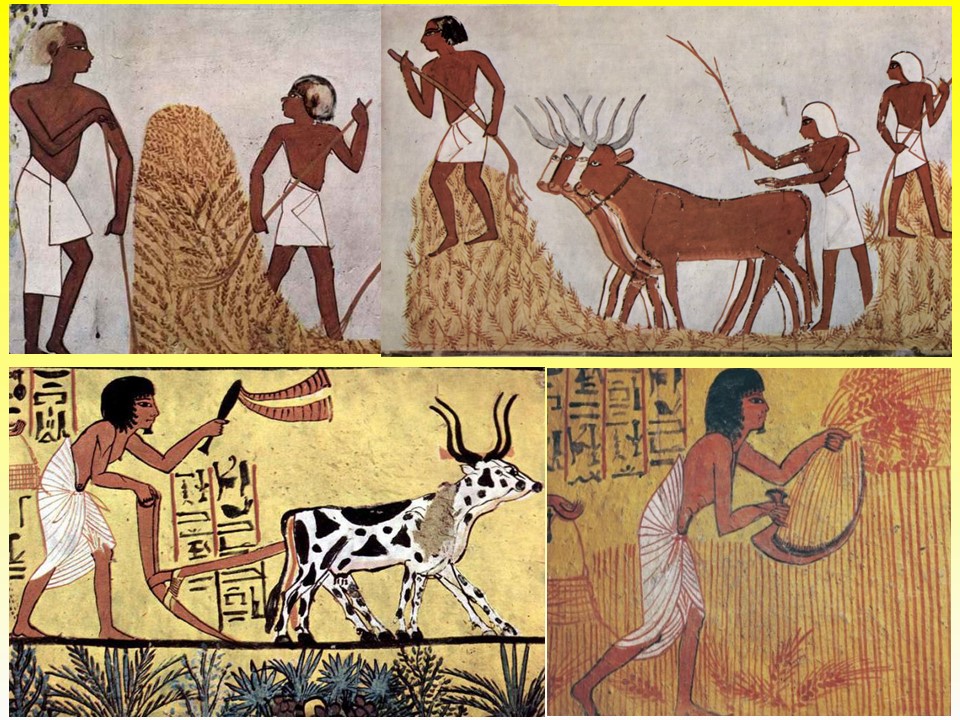

Живопись Древнего Египта отличается плоскостным изображением фигур, чёткими контурами и яркими красками без полутонов. Использовались краски на основе различных вязких веществ и смол. Сверху роспись покрывали лаком или смолой для сохранности. Главной темой живописи были сцены из повседневной жизни египтян.

Литература.

Основными жанрами были заупокойные тексты, сказки, любовная лирика и поучительная литература. Заупокойные тексты должны были обеспечить благополучную жизнь в загробном мире. Сначала их наносили на стены пирамид, потом на саркофаги. В эпоху Нового царства ритуальные тексты, получившие название «Книга мёртвых», стали записывать на папирус.

Театр.

Театра в современном понимании, в Древнем Египте не было. Но во время праздников разыгрывались сценки на религиозные темы с музыкой и танцами.

Музыка.

Распространёнными инструментами были арфа, флейта и тамбурин. Изначально музыка была только аккомпанементом для певцов, но в период Нового царства стала развиваться, как самостоятельный вид искусства.

За время существования Древнего Египта сформировалась богатая, уникальная культура. Сохраняя традиционные основы, искусство развивалось в зависимости от политических и культурных условий. А после потери величия Египта, его традиционное искусство сплелось с греко-римским, чтобы оказать влияние на развитие следующей эпохи.

«Та-Мери – «Возлюбленная страна». Так называли свою землю древние египтяне. И у них были все основания любить свою страну и восхищаться ею. Уникальная природа позволила уже в глубочайшей древности возникнуть на берегах Нила очень ранней цивилизации. Эта цивилизация, развиваясь на протяжении многих веков, создала высочайшую культуру, подарившую человечеству замечательные произведения архитектуры, литературы, искусства».

Исторические, экономические и социальные условия формирования культуры Древнего Египта

Древний Египет! Узкая долина Нила среди безводных пустынь и голых скал. Более 90 % территории Египта занимает пустыня, так называемая «Красная земля». Жизнь там была возможна только в оазисах и в долинах высохших рек. Но благодаря разливам Нила земля эта была одной из плодороднейших в мире. Именно поэтому экономика Древнего Египта основывалась на сельском хозяйстве в плодородной долине Нила. Надо было только уметь задерживать воды и совершенствовать земледелие. Это требовало общих усилий, общей организованности, которые возможны только при сильном централизованном государстве.

В конце 4 тыс. до н.э., в то время когда Европа жила в каменном веке, в Северной Африке, в долине Нила уже созревала высокоразвитая цивилизация.

Древний Египет развивался в нижнем и среднем течении Нила.

Уже во 2 половине 2 тыс. до н.э., в период своего расцвета – в эпоху Нового царства, власть фараонов простиралась до четвертых нильских порогов на юге и распространялась на значительные территории в Восточном Средиземноморье, а также на побережье Красного моря.

Весь Египет с раннединастического периода делился на две больших области: Верхний и Нижний Египет. А эти, в свою очередь, имели по несколько десятков областей, которые греки назвали номами.

Древняя египетская империя в период Нового царства (1450 г. до н.э.)

Верования египтян и их отражение в искусстве.

Древние египтяне, как и многие люди в давние эпохи, и в наше время, верили в то, что у человека есть душа, которая покидает его тело после смерти. Они считали, что душа после смерти летает между двумя мирами – земным и потусторонним. Чтобы душа могла свободно выходить из могилы и затем туда возвращаться, в стене надземной части гробницы устраивался символический выход в виде слегка заглубленной ниши.

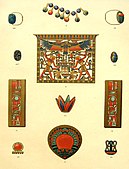

Среди египетских амулетов был широко распространен образ жука-скарабея. Древние египтяне верили, что скарабей обладает животворящей силой. Он был символом вечной жизни. Скарабей, катящий шарик – символ движения солнечного диска по небосклону.

В первую очередь в искусстве Древнего Египта отразилась забота древних египтян о вечной жизни и потустороннем мире. Это – гробницы, саркофаги, заупокойные и ритуальные статуи.

Древние египтяне верили, что для благополучного существования духовного человека в загробном мире необходима сохранность его «материальной оболочки». Отсюда капитальные каменные сооружения — гробницы и появление портретных статуй покойного и его приближенных (заместитель мумии).

Многое делалось для благостной вечной жизни в потустороннем мире.

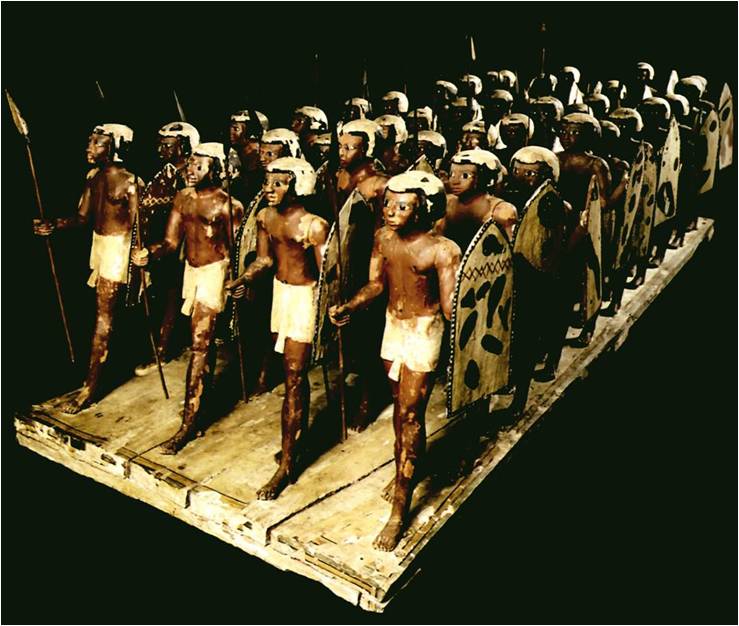

Скульптурная модель египетского воинского отряда.

Модель загородного дома вельможи Мекет-ра из его гробницы около Фив. Фрагмент. Подсчет стада. Среднее царство, 11 династия.

Еще одна важная составляющая египетского искусства: культ фараона – богоравного властителя Египта. Это было необходимо для укрепления власти и единства государства. В искусстве культ фараона отразился в грандиозной монументальности архитектуры и создании многочисленных статуй, колоссов, сфинксов, рельефов и росписей.

Основные черты (особенности) искусства Древнего Египта

Египетская цивилизация явилась создательницей:

— великолепной монументальной каменной архитектуры

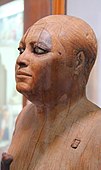

— скульптурного портрета, замечательного своей реалистической правдивостью

— прекрасных изделий художественного ремесла.

1. Монументальность каменной архитектуры.

2. Реализм и правдивость скульптурных портретов сочетается с обобщенностью и стилизацией.

3. Яркой особенностью искусства Древнего Египта явилась преданность традициям в искусстве и соблюдение неких канонов.

Причина этого заключалась в том, что памятники искусства Древнего Египта в своём подавляющем большинстве имели религиозно-культовое назначение. Поэтому создатели этих памятников были обязаны следовать установившимся канонам.

4. Канонизация простейших приемов изображения. Это произошло из-за того, что религиозные воззрения египтян приписали священный смысл художественному облику первых, древнейших памятников египетского искусства.

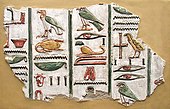

В искусстве Древнего Египта сохранялся ряд условностей, восходящих ещё к первобытному искусству и ставших каноническими:

— изображение предметов и животных, невидимых ни зрителю ни художнику, но которые определённо могут присутствовать в данной сцене (например, рыбы и крокодилы под водой).

— изображение предмета с помощью схематического перечисления его частей (листва деревьев в виде множества условно расположенных листьев или оперение птиц в виде отдельных перьев);

— сочетание в одной и той же сцене изображений предметов, сделанных в разных ракурсах. Например, птица изображалась в профиль, а хвост сверху;

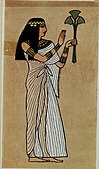

Сочетание разных ракурсов использовалось и при изображении фигуры человека:

— голова в профиль,

— глаз в фас,

— плечи в фас,

— руки и ноги — в профиль.

5. Еще одной особенностью древнеегипетского стиля является подчеркнутая геометричность форм в архитектуре и скульптуре.

Таким образом египтяне достигали обобщенности или

стилизации, которая требовалась каноном. Существуют

предположения, что геометризация и

особая пропорциональность были

обусловлены работой древних египтян

преимущественно с камнем, а не глиной,

как это было, к примеру в Месопотамии.

В Древнем Египте ваятель назывался «санх», что значит «творящий жизнь». Воссоздавая образ умершего, он как бы воссоздавал двойника на случай, если мумия истлеет…

Египетское искусство воссоздавалось во славу царей и идей божественности царя (фараона). Важно, что оно мыслилось не как источник эстетического наслаждения, а прежде всего как утверждение в поражающих воображение формах и образах самих этих идей и той власти, которой был наделен фараон – «бог благой», согласно его официальному титулу.

Периодизация

(по Матье М.Э. Искусство Древнего Египта.)

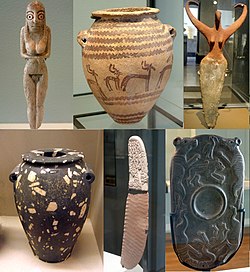

1. Додинастический период. Кон. 5 — 4 тыс. до н.э. Объединение Верхнего и Нижнего Египта. Ок. 3000 г. до н.э.

2. Раннее царство. Нач. 3 тыс.до н.э. (с 3000 по 2800 гг.до н.э.)

3. Древнее царство. 3-е тыс. до н.э.

4. Среднее царство. 21 в. – 18 в. до н.э.

5. Новое царство. Ок. 1600 г. – 11 в. до н.э.

6. Позднее время. 11 в. – 9 в. до н.э.

7. Эллинистический Египет. 332 г. до н.э.(завоевание Александром Македонским) – 30 г. до н.э.

Додинастический период

Кон. 5 — 4 тыс. до н.э.

Уже во времена додинастического периода древние египтяне, жившие родовыми общинами, особенно тщательно оформляли могилу вождя, так как считалось, что «вечное» существование его обеспечивало благоденствие всей общине.

В изобразительном искусстве этой поры постепенно начинает складываться система определенных способов передачи окружающей действительности – древнеегипетский стиль. Это хорошо прослеживается по важной для истории искусства группе памятников – плиткам с рельефными изображениями. Небольшие плоские каменные пластины служили для растирания и перемешивания красок, применявшихся во время культовых обрядов.

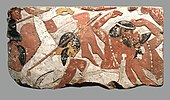

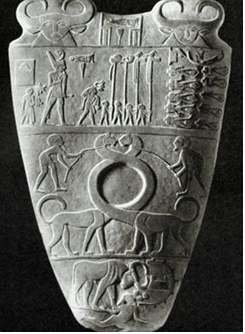

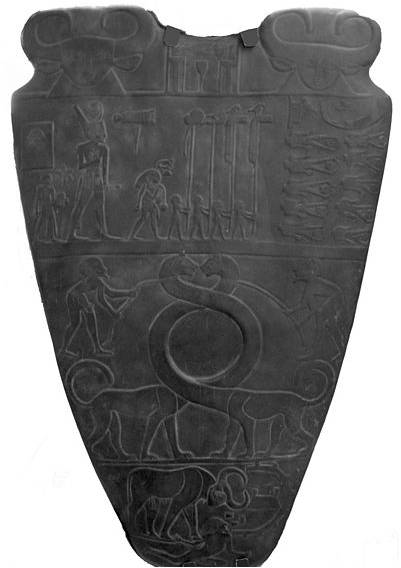

Первый памятник, очень ясно показывающий сложение древнеегипетского стиля, и имеющий общегосударственное значение – плита Нармера.

Плита (палетка) фараона Нармера.

Ок. 3000 г. до н. э. Шифер. Высота — 64 см.

Она относится к важному времени формирования египетской цивилизации и возникновению первого древнеегипетского государства.

Плита сделана в ознаменование объединения Верхнего (южного) и Нижнего (северного) Египта в единое государство.

После победы царь Менес основал новую столицу в Мемфисе, на границе двух стран, что позволяло ему успешнее править объединенным государством.

Плита дошла до нас от его преемника Нармера.

Содержание:

На одной стороне царь в короне южного Египта убивает северянина, внизу — убегающие северяне.

На другой стороне наверху — торжество по случаю победы: царь в короне побеждённого Севера идёт с приближёнными смотреть на обезглавленные трупы врагов, а внизу — царь в образе быка, разрушающего вражескую крепость и топчущего врага; средняя часть этой стороны занята символической культовой сценой неясного содержания.

В этом памятнике уже можно проследить основные черты складывающегося древнеегипетского стиля:

— Построчное изображение

— Сложение законченной композиции с композиционным центром (принцип доминанты и соподчинения)

— Выразительность силуэтов.

— Последовательность и симметрия в изображении фигур.

— Отдельные фигуры делаются большими, чем остальные, чтобы подчеркнуть их важную роль.

Раннее царство

С 3000 по 2800 гг. до н.э.Архитектура

Ведущее положение в египетском искусстве уже с самых ранних времен заняла архитектура.

Жилая архитектура из дерева и кирпича-сырца (из необожженной глины) не сохранилась.

В области архитектуры гробниц к концу Раннего царства сформировался облик погребений египетских царей и знати.

Здание из кирпича и камня включало в себя подземные погребальные камеры и прямоугольное сооружение над поверхностью земли. Стены его были наклонены внутрь, а сверху завершалось плоской крышей.

В надземной части устраивали культовые помещения для статуй богов и владельца гробницы с жертвенником перед так называемой ложной дверью, то есть перед изображением двери, как бы ведущей в «вечное жилище» умершего.

Название этих построек – мастаба (от арабского скамья).

Древнее царство

28 – 23 вв. до н.э.

Время окончательного сложения всех основных форм египетского искусства.

Архитектура

Именно в период Древнего царства складывается самый известный египетский тип гробницы – пирамида.

Перед древнеегипетскими зодчими стояла задача произвести впечатление подавляющей мощи и силы власти фараона. С этой целью для увеличения надземной части гробницы была изобретена форма пирамиды.

Ступенчатая пирамида Джосера в Саккара. Древнее царство, середина 27 в. до н.э. Зодчий Имхотеп. Скорее всего, замысел архитектора был поставить несколько мастаб уменьшающегося размера друг на друга.

Переходный вид – ломаная пирамида Снофру в Дашуре. Начало 26 в. до н.э. Древнее царство.

Пирамида Снофру в Медуме. 27 в. до н.э.

Египетские некрополи всегда располагались на западном берегу Нила.

Фараоны IV династии избрали для своих погребений место недалеко от Саккары — в современной Гизе.

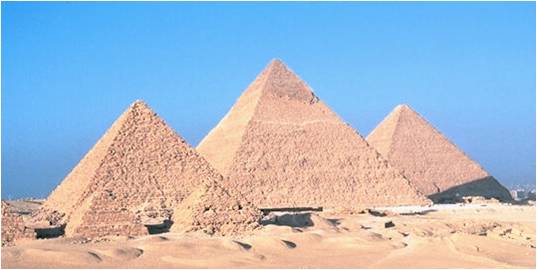

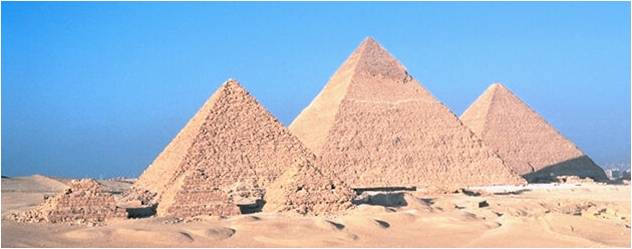

Ансамбль пирамид в Гизе.

Три великие классические пирамиды фараонов Хеопса (Хуфу), Хефрена (Хафра) и Микерина (Менкаура). Сложены из гигантских блоков известняка, средним весом 2,5 тонны, которые держаться силой собственной тяжести.

Ансамбль включает в себя малые пирамиды цариц и заупокойные храмы, примыкавшие к пирамиде с восточной стороны.

Рядом с нижним заупокойным храмом нередко помещали сфинкса.

Сфинкс — лежащий лев с человеческим лицом. Он воплощал сверхчеловеческую сущность фараона.

У нижнего заупокойного храма Хефрена помещён Большой Сфинкс. Считается, что он имеет портретное изображение фараона. Высечен из монолитной известковой скалы.

У статуи отсутствует нос, повреждение шириной в один метр.

Версии: эту деталь статуи отшибло пушечным ядром во время битвы Наполеона с турками (1798); на ложность этого мнения указывают рисунки датского путешественника, видевшего безносого сфинкса уже в 1737 г. — в других версиях легенды место Наполеона занимают англичане или мамелюки.

Великая пирамида Хеопса. Фотография XIX века. Зодчий Хемиун. Вторая четверть 26 в. до н.э. Одно из «семи чудес света». Построена на массивном природном скальном возвышении, которое оказалось в самой середине основания пирамиды, его высота около 9 метров. Была сделана облицовка пирамиды, отчего она сияла на солнце.

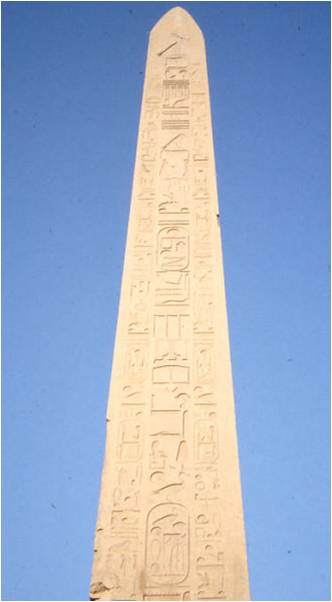

К концу периода Древнего царства появляется новый тип здания — солнечный храм. Его строили на возвышении и обносили стеной. В центре просторного двора с молельнями ставили колоссальный каменный обелиск с позолоченной медной верхушкой и огромным жертвенником у подножья.

Обелиски — «Каменные иглы». Обелиск с египетскими письменами.

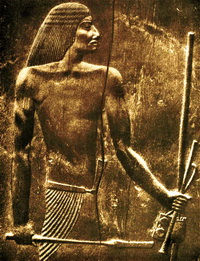

Скульптура

Скульптура как и все египетское искусство имела ритуальное значение.

В пирамидах, в специальном помещении обязательно помещали статую умершего на случай, если что-то случится с мумией.

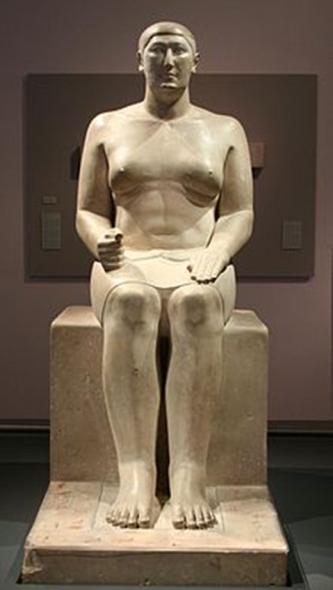

В эпоху Древнего царства сложились основные черты скульптуры:

— симметрия и фронтальность в построении фигур

— четкость и спокойствие поз.

— геометризм и обобщенность формы.

— обязательное сохранение портретных черт.

Изображение фигуры целиком:

1. стоящей с выдвинутой вперёд левой ногой — поза движения в вечности.

2. Сидящей на кубообразном троне.

3. В позе «писца» со скрещенными ногами на земле.

Триада Микерина (Каир).

Фараон Микерин в сопровождении богинь. Скульптурная группа из заупокойного храма Микерина в Гизе. Древнее царство.

Поза движения в вечности. Тема единения богоравного фараона с богинями-покровительницами. Безукоризненно прекрасные формы.

Хефрен. Древнее царство. Симметрия и фронтальность в построении фигуры.

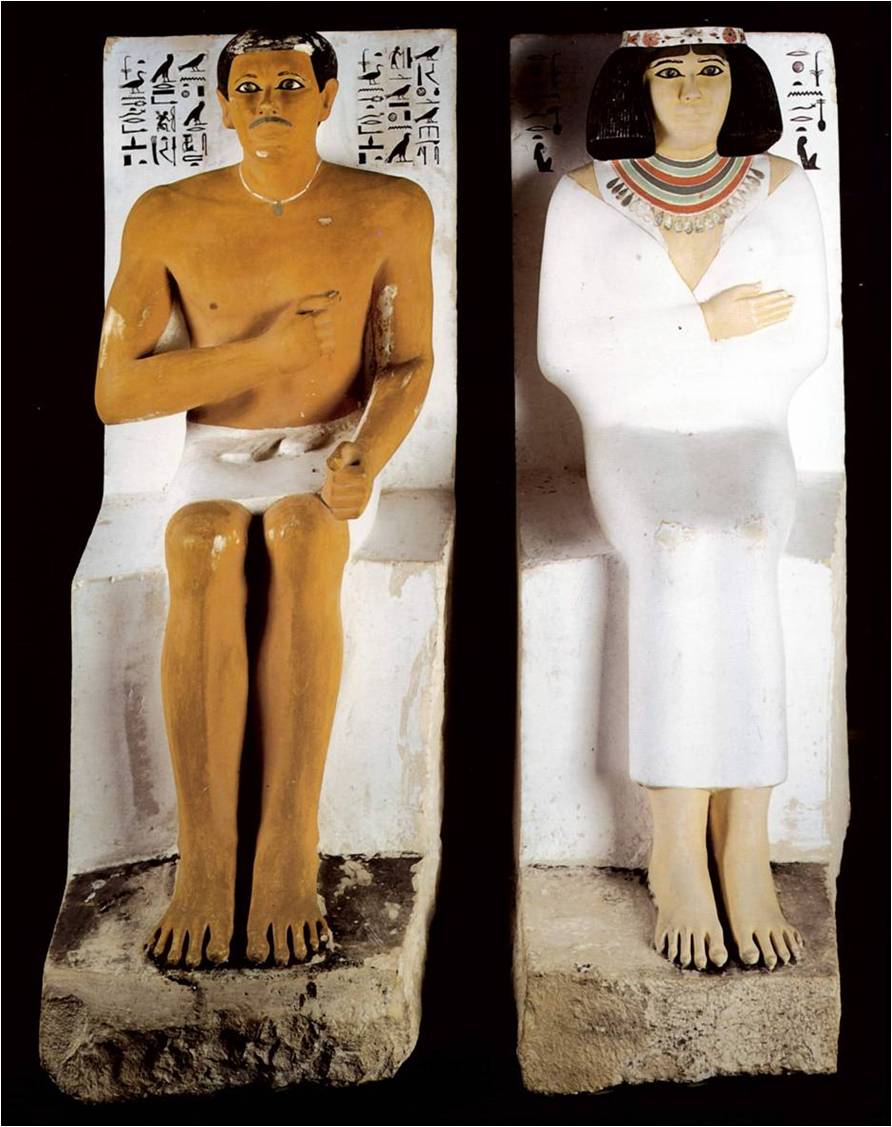

Статуи царевича Рахотепа и Нофрет. 27 век до н. э. Древнее царство. Каирский музей.

Торжественно восседают перед нами знатные супруги. По канону мужская фигура окрашена в кирпично-красный цвет, женская — в желтый. Волосы на прямо поставленных головах всегда были черными, а одежды белыми. Нет полутонов, декоративность.

Писец Каи. Из его гробницы в Саккара. Известняк с раскраской, инкрустация глаз. 25 – 1 пол. 24 в. до н.э. Н — всего 53 см. Тело тонировано в традиционный для мужских фигур «цвет загара». Изображен без парика. Пристальный, внимательный взгляд, готов записывать.

Статуя найдена во время раскопок в кон. 19 в. Когда рабочие пробились в гробницу, глаза изваяния сверкнули так ярко, что бедняги в ужасе разбежались. А потом, приняв ее за воплощение дьявола, захотели разбить. Начальнику раскопок пришлось защищать древнее изваяние с пистолетом в руках. Так статуя Каи едва не погибла благодаря силе художественного эффекта инкрустированных глаз.

Белки делались из непрозрачного кварца; роговица – из хрусталя, покрытого коричневой смолой, которая просвечивая сквозь хрусталь, создавала иллюзию карих глаз. Зрачком служила капелька черной смолы, заполнявшая небольшое углубление на задней стороне «роговицы».

Среднее царство

21 – 18 вв. до н.э.

С 23 по 21 вв. в результате воин, упадка идеи о божественной власти фараона произошел распад страны. Это повлияло на развитие индивидуализма в искусстве.

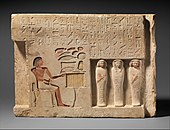

Индивидуализм проявился в том, что каждый стал заботиться о собственном бессмертии — не только фараон и вельможная знать, но и простые люди. Культ умерших очень упростился. Гробницы типа мастаба стали излишней роскошью. Для обеспечения вечной жизни стало достаточно одной стелы — каменной плиты, на которой были написаны магические тексты.

Фараоны продолжали строить гробницы в виде пирамид, но размеры их значительно уменьшились. Материалом для строительства служили уже не каменные блоки, а кирпич-сырец, поэтому в настоящее время эти пирамиды представляют собой груды развалин.

С новым этапом централизации власти в период Среднего царства вновь активизировалось строительство.

Наряду с пирамидами появился новый тип погребальных сооружений — полускальный храм. Он сочетал в себе традиционную форму пирамиды и скальную гробницу.

Заупокойный храм фараона Ментухотепа II в Дейр-эль-Бахри (Долине царей). Среднее царство.

Скульптура

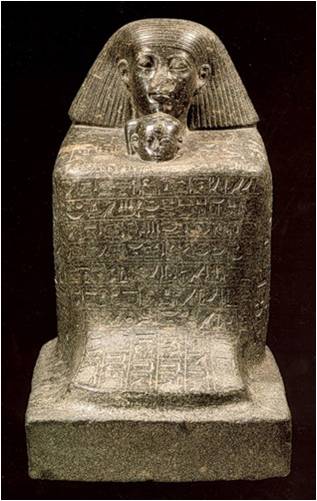

Статуя фараона Аменемхета III. Черный гранит. Эрмитаж.

На голове – убор фараонов: полосатый платок с выпуклым изображением священной змеи надо лбом. Царственно восседает на троне. Более индивидуален, чем предшествующие скульптуры (например, статуя ф.Хефрена, Древнее царство).

Бюст Аменемхета III. Пристальный взгляд, энергичное выражение лица с широкими скулами выдают крутой нрав этого царя.

Новое царство

Ок. 1600 г. – 11 в. до н.э.

После раскола Среднего царства объединенный Египет восстал с новой силой в Новом царстве. Это период наивысшего расцвета, торжество египетской мощи.

Царь мощного тогда государства Митанни свидетельствовал о том, что в державе фараона «золото все равно, что пыль».

Строительство по-прежнему имеет целью утверждение божественного характера царской власти. Но вместо пирамид теперь возводятся храмы.

Усыпальницы фараонов сооружаются в так называемой «Долине царей» — Дейр-эль-Бахри напротив Фив.

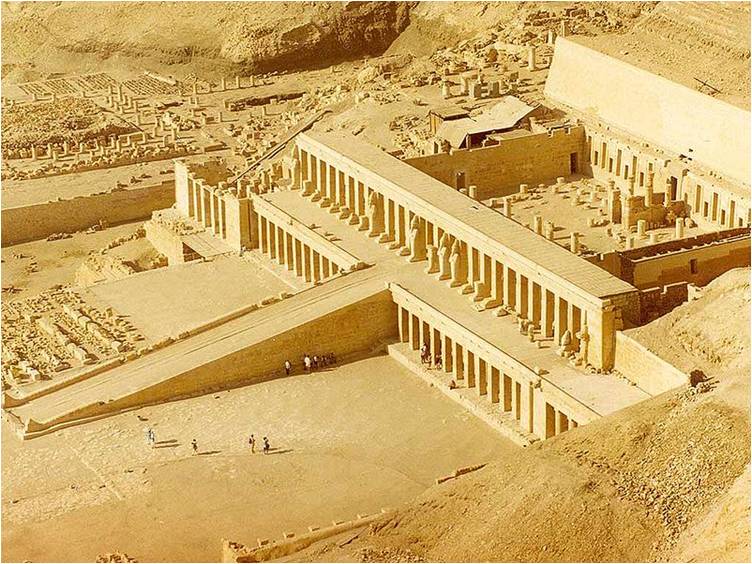

Примером полускального заупокойного храма может служить храм царицы Хатшепсут в Дейр-эль-Бахри.

Храм царицы Хатшепсут. Ок. 1500 г. до н.э. Зодчий Сенмут.

Все части храма расположены по горизонтальной оси. Три террасы возвышаются одна над другой. Чередующиеся горизонтали олицетворяют бесконечность или вечность. На террасах помещались водоемы, густо обсаженные деревьями. Залы храма высечены в скале.

Зодчий Сенмут (Сененмут, фаворит царицы) с дочерью Хатшепсут маленькой Нефрура.

Дейр-эль-Бахри. Храм Хатшепсут.

Залы храма были украшены великолепной живописью и скульптурами с изображением экспедиций в дальние страны.

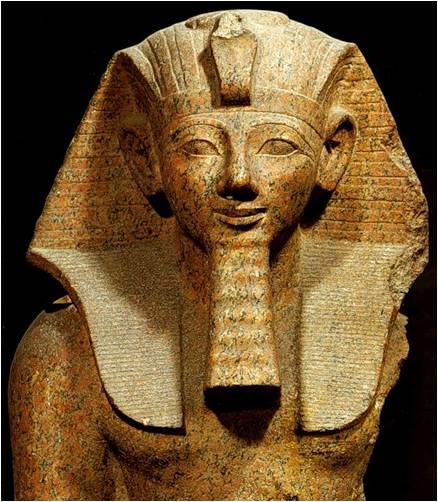

Хатшепсут. Новое царство.

Как и сами храмы все перед ними дышало торжественностью и величием: аллеи сфинксов, гигантские изваяния фараонов – колоссы.

Гигантомания отличает многие памятники эпохи Нового царства.

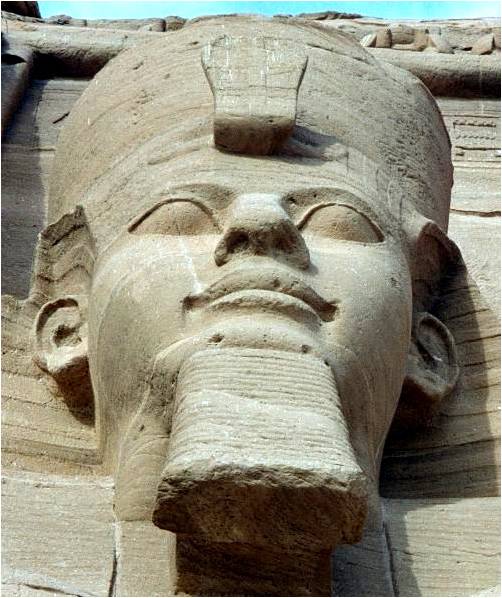

Скальный храм Рамзеса II в Абу-Симбеле. Рамзес II – один из самых могущественных фараонов Нового царства.

Храм Рамзеса.

Статуи фараона у входа в храм поражают своими размерами – 20 м в высоту. Храм посвящен фараону и трём богам: Амону, Ра, и Птаху.

Голова колосса Рамсеса II в Абу-Симбеле

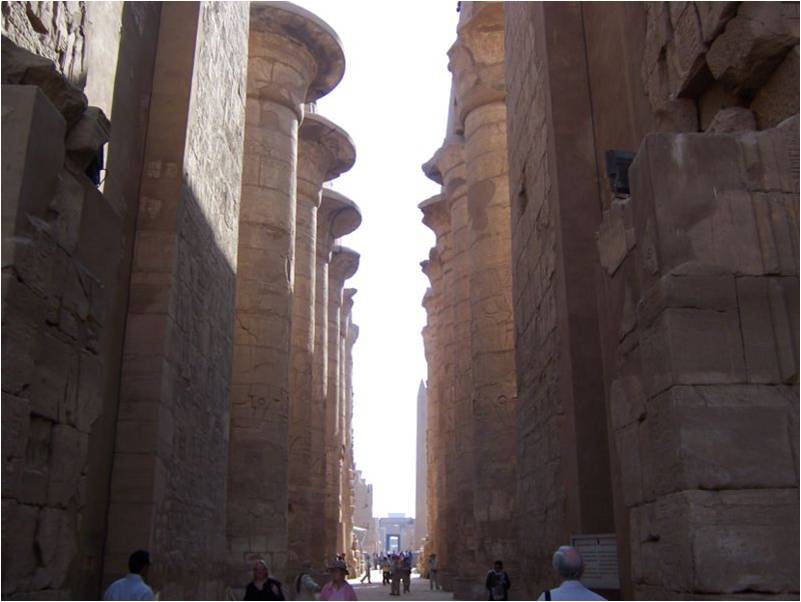

Самыми грандиозными постройками Нового царства считаются Карнакский и Луксорский храмы.

Храм в Карнаке

Архитектор Инени. Посвящен верховному богу – Амону. Строился несколько столетий — от Среднего царства до эпохи Птолемеев. Каждый фараон старался увековечить здесь свое имя.

Храм представлял собой вытянутый в плане прямоугольник, окружённый высокой массивной стеной.

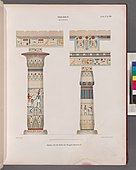

Карнак. План. 1. Аллея сфинксов. 12 в. до н. э. 2. Большой двор с храмами фараонов Сети II и Рамсеса III. 3. Гипостильный зал. 15—13 вв. до н. э. 4. Двор. 5. Главная часть храма бога Амона-Ра (16—12 вв. до н. э.) с руинами храма Среднего царства и храмом фараона Тутмеса III. 6. Храм бога Хонсу. 12 в. до н. э. Римскими цифрами обозначены пилоны.

Храм состоял из комплекса сооружений, расположенных по продольной оси храма:

От Нила к храму вела дорога – аллея сфинксов.

Аллея сфинксов начинается от древней пристани на берегу Нила и ведет к первому пилону. Аллея была создана при Рамсесе II (XIX династия, Новое царство). Сфинксы с телом льва и головой барана. Баран — священное животное бога Амона.

В правление фараона Нектанебо I (30-я династия, Птолемеев, Поздний период) трехкилометровая дорога, соединявшая храмы Луксора и Карнака, была украшена каменными изваяниями сфинксов. Часть аллеи, начинавшаяся в Карнаке, состояла из сфинксов с телом льва и головой барана; от Луксорского храма шла аллея, в которой сфинксы имели человеческие головы.

Вход в храм называется пилоны. Обычно перед ними воздвигали гигантские статуи фараона и позолочённые обелиски.

После пилон следовали несколько внутренних дворов, сменявших друг друга:

обнесенный по периметру колоннадой двор – перистильный (перистиль).

В центре двора располагался жертвенный камень.

Далее шел зал целиком заполненный колоннами – гипостильный (гипостиль).

В Карнаке фараоном Рамзесом II был построен гигантский гипостильный двор (зал).

Его S — 5000 м².

Насчитывает ок. 134 колонн, расположенных в 16 рядов.

Н центральных – 23 м.

На капители каждой из них могло поместиться 100 человек.

Здесь в полумраке подданные с особой силой ощущали величие и непостижимость божественного начала фараона, который создал этот храм.

За внутренними дворами-залами, в глубине храма была молельня, состоящая из нескольких помещений. Центром ее был зал, где на жертвенном камне находилась священная ладья со статуей главного бога — Амона.

В состав храма входили многочисленные хозяйственные помещения.

Обязательно на территории храма устраивались священные пруды.

Карнак. Один из священных прудов.

Храм в Луксоре

Несколько меньше Карнака, но гармоничность и ясность скрашивают «чрезмерности». Посвящен также богу солнца Амону-Ра. Расположен на правом берегу Нила, в южной части Фив, в пределах современного города Луксор.

С Карнаком он был соединен мощёной аллеей сфинксов.

Древнейшая часть — основана при Аменхотепе III. Рамсес Великий пристроил северный перистиль и пилон.

Луксор. Аллея сфинксов и пилоны. У северного входа Луксорского храма — четыре колосса и два обелиска, из которых один перевезен в 1830-е гг. в Париж, на площадь Согласия.

Луксор. Колонный зал Аменхотепа III тёмное время суток

Луксор. Аллея сфинксов и пилоны ночью

Аменхотеп III был одним из величайших фараонов-строителей, которых когда-либо знал Египет. Возле развалин его заупокойного храма в прошлом веке была раскопана аллея из сфинксов, изваянных из розового асуанского гранита.

Два из них стоят ныне на Университетской набережной в Санкт-Петербурге напротив Академии художеств.

Луксор. Рамессеум – гипостильный зал, построенный Рамзесом Великим. Стройность колонн с капителями в виде раскрытых метелок и бутонов папируса производит неизгладимое впечатление.

Луксор. Старинная фотография колонного зала Аменхотепа III.

Искусство середины Нового царства Время правления Аменхотепа IV (Эхнатона)

– Амарнский периодпервая половина 14 в. до н.э.

Искусство второй половины Нового царства

2 пол. 14 – начало 11 вв. до н.э.

Выводы

Основные черты искусства Древнего Египта: каноничность, символичность, геометричность, массивность, сочетание стилизации и натуралистичности в одном изображении, устойчивость традиций и др.

Древнее царство – создание единой державы, искусство выражало прежде всего мощь государства и непостижимость обожествляемой власти.

Среднее царство – колебание устоев, переоценка ценностей.

Новое царство – период расцвета, торжество египетской мощи.

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculptures, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewelry, ivories, architecture, and other art media. It is also very conservative: the art style changed very little over time. Much of the surviving art comes from tombs and monuments, giving more insight into the ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs.

The ancient Egyptian language had no word for «art». Artworks served an essentially functional purpose that was bound with religion and ideology. To render a subject in art was to give it permanence. Therefore, ancient Egyptian art portrayed an idealized, unrealistic view of the world. There was no significant tradition of individual artistic expression since art served a wider and cosmic purpose of maintaining order (Ma’at).

Art of Pre-Dynastic Egypt (6000–3000 BC)

Artifacts of Egypt from the Prehistoric period, 4400–3100 BC: clockwise from top left: a Badarian ivory figurine, a Naqada jar, a Bat figurine, a cosmetic palette, a flint knife, and a diorite vase.

Pre-Dynastic Egypt, corresponding to the Neolithic period of the prehistory of Egypt, spanned from c. 6000 BC to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period, around 3100 BC.

Continued expansion of the desert forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile and adopt a more sedentary lifestyle during the Neolithic. The period from 9000 to 6000 BC has left very little archaeological evidence, but around 6000 BC, Neolithic settlements began to appear all over Egypt.[1] Studies based on morphological,[2] genetic,[3] and archaeological data[4] have attributed these settlements to migrants from the Fertile Crescent returning during the Neolithic Revolution, bringing agriculture to the region.[5]

Merimde culture (5000–4200 BC)

From about 5000 to 4200 BC, the Merimde culture, known only from a large settlement site at the edge of the Western Nile Delta, flourished in Lower Egypt. The culture has strong connections to the Faiyum A culture as well as the Levant. People lived in small huts, produced simple undecorated pottery, and had stone tools. Cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs were raised, and wheat, sorghum and barley were planted. The Merimde people buried their dead within the settlement and produced clay figurines.[6] The first Egyptian life-size head made of clay comes from Merimde.[7]

Badarian culture (4400–4000 BC)

The Badarian culture, from about 4400 to 4000 BC,[8] is named for the Badari site near Der Tasa. It followed the Tasian culture (c. 4500 BC) but was so similar that many consider them one continuous period. The Badarian culture continued to produce blacktop-ware pottery (albeit much improved in quality) and was assigned sequence dating (SD) numbers 21–29.[9] The primary difference that prevents scholars from merging the two periods is that Badarian sites use copper in addition to stone and are thus chalcolithic settlements, while the Neolithic Tasian sites are still considered Stone Age.[9]

-

A Badarian burial. 4500–3850 BC

-

Mortuary figurine of a woman; 4400–4000 BC; crocodile bone; height: 8.7 cm; Louvre

-

String of beads; 4400–3800 BC; the beads are made of bone, serpentinite and shell; length: 15 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Vase in the shape of a hippopotamus. Early Predynastic, Badarian. 5th millennium BC

Naqada culture (4000–3000 BC)

The Naqada culture is an archaeological culture of Chalcolithic Predynastic Egypt (c. 4400–3000 BC), named for the town of Naqada, Qena Governorate. It is divided into three sub-periods: Naqada I, II and III.

Naqada I

The Amratian (Naqada I) culture lasted from about 4000 to 3500 BC.[8] Black-topped ware continues to appear, but white cross-line ware – a type of pottery which has been decorated with crossing sets of close parallel white lines – is also found at this time. The Amratian period falls between 30 and 39 SD.[10]

-

Ovoid Naqada I (Amratian) black-topped terracotta vase, (c. 3800–3500 BC)

-

Ibex comb; 3800–3500 BC; hippopotamus ivory; 6.5 × 3.8 × 0.2 cm; Louvre

-

White cross-lined bowl with four legs; 3700–3500 BC; painted pottery; height: 15.6 cm, diameter: 19.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Naqada II

The Gerzean culture (Naqada II), from about 3500 to 3200 BC,[8] is named after the site of Gerzeh. It was the next stage in Egyptian cultural development, and it was during this time that the foundation of Dynastic Egypt was laid. Gerzean culture is largely an unbroken development of Amratian culture, starting in the Nile delta and moving south through Upper Egypt, but failing to dislodge Amratian culture in Nubia.[13] Gerzean pottery has been assigned SD values of 40 through 62, and is distinctly different from Amratian white cross-lined wares or black-topped ware.[10] It was painted mostly in dark red with pictures of animals, people, and ships, as well as geometric symbols that appear to have been derived from animals.[13] Wavy handles, which were rare before this period (though occasionally found as early as SD 35), became more common and more elaborate until they were almost completely ornamental.[10]

During this period, distinctly foreign objects and art forms entered Egypt, indicating contact with several parts of Asia, particularly with Mesopotamia. Objects such as the Gebel el-Arak Knife handle, which has patently Mesopotamian relief carvings on it, have been found in Egypt,[14] and the silver which appears in this period can only have been obtained from Asia Minor.[13] In addition, Egyptian objects were created which clearly mimic Mesopotamian forms.[15] Cylinder seals appeared in Egypt, as well as recessed paneling architecture. The Egyptian reliefs on cosmetic palettes were made in the same style as the contemporary Mesopotamian Uruk culture, and ceremonial mace heads from the late Gerzean and early Semainean were crafted in the Mesopotamian «pear-shaped» style, instead of the Egyptian native style.[16]

The route of this trade is difficult to determine, but contact with Canaan does not predate the early dynastic, so it is usually assumed to have been by water.[17] During the time when the Dynastic Race Theory was popular, it was theorized that Uruk sailors circumnavigated Arabia, but a Mediterranean route, probably by middlemen through Byblos, is more likely, as evidenced by the presence of Byblian objects in Egypt.[17]

The fact that so many Gerzean sites are at the mouths of wadis which lead to the Red Sea may indicate some amount of trade via the Red Sea (though Byblian trade potentially could have crossed the Sinai and then taken to the Red Sea).[18] Also, it is considered unlikely that something as complicated as recessed panel architecture could have worked its way into Egypt by proxy, and at least a small contingent of migrants is often suspected.[17]

Despite this evidence of foreign influence, Egyptologists generally agree that the Gerzean Culture is predominantly indigenous to Egypt.

-

Decorated ware jar illustrating boats and trees; 3650–3500 BC; painted pottery; height: 16.2 cm, diameter: 12.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Protodynastic Period (Naqada III)

The Naqada III period, from about 3200 to 3000 BC,[8] is generally taken to be identical with the Protodynastic period, during which Egypt was unified.

Naqada III is notable for being the first era with hieroglyphs (though this is disputed), the first regular use of serekhs, the first irrigation, and the first appearance of royal cemeteries.[19] The art of the Naqada III period was quite sophisticated, exemplified by cosmetic palettes. These were used in predynastic Egypt to grind and apply ingredients for facial or body cosmetics. By the Protodynastic period, the decorative palettes appear to have lost this function and were instead commemorative, ornamental, and possibly ceremonial. They were made almost exclusively from siltstone, which originated from quarries in the Wadi Hammamat. Many of the palettes were found at Hierakonpolis, a center of power in predynastic Upper Egypt. After the unification of the country, the palettes ceased to be included in tomb assemblages.

-

The Davis comb; 3200–3100 BC; ivory; 5.5 × 3.9 × 0.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

The Battlefield palette; 3100 BC; mudstone; width: 28.7 cm, depth: 1 cm; from Abydos (Egypt); British Museum (London)

Art of Dynastic Egypt

Early Dynastic Period (3100–2685 BC)

The Early Dynastic Period of Egypt immediately follows the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, c. 3100 BC. It is generally taken to include the First and Second Dynasties, lasting from the end of the Naqada III archaeological period until about 2686 BC, or the beginning of the Old Kingdom.[8]

Cosmetic palettes reached a new level of sophistication during this period, in which the Egyptian writing system also experienced further development. Initially, Egyptian writing was composed primarily of a few symbols denoting amounts of various substances. In the cosmetic palettes, symbols were used together with pictorial descriptions. By the end of the Third Dynasty, this had been expanded to include more than 200 symbols, both phonograms and ideograms.[20]

-

Bracelet; c. 2650 BC; gold; diameter: 6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Old Kingdom (2686–2181 BC)

The Old Kingdom of Egypt is the period spanning c. 2686–2181 BC. It is also known as the «Age of the Pyramids» or the «Age of the Pyramid Builders», as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid builders of the Fourth Dynasty. King Sneferu perfected the art of pyramid-building and the pyramids of Giza were constructed under the kings Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure.[22] Egypt attained its first sustained peak of civilization, the first of three so-called «Kingdom» periods (followed by the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom) which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley.

-

Wooden statue of the scribe Kaaper; c. 2450 BC; wood, copper and rock crystal; height: 1.1 m; from Saqqara; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

-

Seated portrait statue of a man with his two sons; circa 2400 BC; painted limestone; from Saqqara; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

Seated portrait statue of Dersenedj, scribe and administrator; circa 2400 BC; rose granite; height: 68 cm; from Giza; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

Seated portrait group of Dersenedj and his wife Nofretka; circa 2400 BC; rose granite; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC)

A room from the tomb of Sarenput II, at Aswan (Egypt). The rough translation of the wall is, «Blessed in the service of Satet, mistress of the Elephantine and of Nekhbet, Nabure-Nakht». Nabur-Nakht was another name of Sarenput.

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (a.k.a. «The Period of Reunification») follows a period of political division known as the First Intermediate Period. The Middle Kingdom lasted from around 2050 BC to around 1710 BC, stretching from the reunification of Egypt under the reign of Mentuhotep II of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Twelfth Dynasty. The Eleventh Dynasty ruled from Thebes and the Twelfth Dynasty ruled from el-Lisht. During the Middle Kingdom period, Osiris became the most important deity in popular religion.[24] The Middle Kingdom was followed by the Second Intermediate Period of Egypt, another period of division that involved foreign invasions of the country by the Hyksos of West Asia.

After the reunification of Egypt in the Middle Kingdom, the kings of the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties were able to return their focus to art. In the Eleventh Dynasty, the kings had their monuments made in a style influenced by the Memphite models of the Fifth and early Sixth Dynasties. During this time, the pre-unification Theban relief style all but disappeared. These changes had an ideological purpose, as the Eleventh Dynasty kings were establishing a centralized state, and returning to the political ideals of the Old Kingdom.[25] In the early Twelfth Dynasty, the artwork had a uniformity of style due to the influence of the royal workshops. It was at this point that the quality of artistic production for the elite members of society reached a high point that was never surpassed, although it was equaled during other periods.[26] Egypt’s prosperity in the late Twelfth Dynasty was reflected in the quality of the materials used for royal and private monuments.

-

Coffin of Senbi; 1918–1859 BC; gessoed and painted cedar; overall: 70 x 55 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Jewelry chest of Sithathoryunet; 1887–1813 BC; ebony, ivory, gold, carnelian, blue faience and silver; height: 36.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Mirror with a papyrus-shaped handle; 1810–1700 BC; unalloyed copper, gold and ebony; 22.3 × 11.3 × 2.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Relief from the chapel of the overseer of the troops Sehetepibre; 1802–1640 BC; painted limestone; 30.5 × 42.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

A group of West Asiatic peoples (possibly Canaanites and precursors of the future Hyksos) depicted entering Egypt circa 1900 BC. From the tomb of a 12th dynasty official Khnumhotep II.[27][28][29][30]

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650–1550 BC)

The so-called «Hyksos Sphinxes» are peculiar sphinxes of Amenemhat III which were reinscribed by several Hyksos rulers, including Apepi. Earlier Egyptologists thought these were the faces of actual Hyksos rulers.[31]

The Hyksos, a dynasty of rulers originating from the Levant, do not appear to have produced any court art,[32] instead appropriating monuments from earlier dynasties by writing their names on them. Many of these are inscribed with the name of King Khyan.[33] A large palace at Avaris has been uncovered, built in the Levantine rather than the Egyptian style, most likely by Khyan.[34] King Apepi is known to have patronized Egyptian scribal culture, commissioning the copying of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.[35] The stories preserved in the Westcar Papyrus may also date from his reign.[36]

The so-called «Hyksos sphinxes» or «Tanite sphinxes» are a group of royal sphinxes depicting the earlier Pharaoh Amenemhat III (Twelfth Dynasty) with some unusual traits compared to conventional statuary, for example prominent cheekbones and the thick mane of a lion, instead of the traditional nemes headcloth. The name «Hyksos sphinxes» was given due to the fact that these were later reinscribed by several of the Hyksos kings, and were initially thought to represent the Hyksos kings themselves. Nineteenth-century scholars attempted to use the statues’ features to assign a racial origin to the Hyksos.[37] These sphinxes were seized by the Hyksos from cities of the Middle Kingdom and then transported to their capital Avaris where they were reinscribed with the names of their new owners and adorned their palace.[31] Seven of those sphinxes are known, all from Tanis, and now mostly located in the Cairo Museum.[31][38] Other statues of Amenehat III were found in Tanis and are associated with the Hyksos in the same manner.

-

Electrum dagger handle of a soldier of Hyksos Pharaoh Apepi, illustrating the soldier hunting with a short bow and sword. Inscriptions: «The perfect god, the lord of the two lands, Nebkhepeshre Apepi» and «Follower of his lord Nehemen», found at a burial at Saqqara.[45] Now at the Luxor Museum.[46][47]

New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069 BC)

The New Kingdom, also referred to as the «Egyptian Empire», is the period between the 16th and 11th centuries BC, covering the 18th, 19th, and 20th dynasties of Egypt. The New Kingdom followed the Second Intermediate Period and was succeeded by the Third Intermediate Period. It was Egypt’s most prosperous time and marked the peak of its power.[48] This tremendous wealth can be attributed to the centralization of bureaucratic power and many successful military campaigns which opened trade routes. With the expansion of the Egyptian Empire, Kings gained access to important commodities such as cedar from Lebanon and luxury materials such as lapis lazuli and turquoise.

The artwork produced during the New Kingdom falls into three broad periods: Pre-Amarna, Amarna, and Ramesside. Although stylistic changes as a result of shifts in power and variation of religious ideals occurred, the statuary and relief work throughout the New Kingdom continued to embody the main principles of Egyptian art: frontality and axiality, hierarchy of scale, and composite composition.

Pre-Amarna

The Pre-Amarna period, the beginning of the eighteenth dynasty of the New Kingdom, was marked by the growing power of Egypt as an expansive empire. The artwork reflects a combination of Middle Kingdom techniques and subjects with the newly accessed materials and styles of foreign lands.[49] A large portion of the art and architecture of the Pre-Amarna period was produced by Queen Hatshepshut, who led a widespread building campaign to all gods during her reign from 1473 to 1458 B.C.E.. The queen made significant additions to the temple at Karnak, undertook the construction of an extensive mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, and produced a prolific amount of statuary and relief work in hard stone. The extent of these building projects was made possible by the centralization of power in Thebes and reopening of trade routes by previous New Kingdom ruler Ahmose I.[50]

The Queen’s elaborate mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri provides many well-preserved examples of the artwork produced during the Pre-Amarna period. The massive three-level, colonnaded temple was built into the cliffs of Thebes and adorned with extensive painted relief. Subjects of these reliefs ranged from traditional funerary images and legitimization of Hatshepsut as the divine ruler of Egypt to battle and expedition scenes in foreign lands. The temple also housed numerous statues of the Queen and gods, particularly Amun-ra, some of which were colossal in scale. The artwork from Hatshepshut’s reign is trademarked by the re-integration of Northern culture and style as a result of the reunification of Egypt. Thutmoses III, the predecessor to the Queen, also commissioned vast amounts of large-scale artwork and by his death Egypt was the most powerful empire in the world.[50]

During the New Kingdom — the 18th Dynasty especially — it was common for Kings to commission large and elaborate temples dedicated to the major gods of Egypt. These structures, built from limestone or sandstone (materials more permanent than the mud brick used for earlier temples) and filled with rare materials and vibrant wall paintings, exemplify the wealth and access to resources that Egyptian Empire enjoyed during the New Kingdom. The temple at Karnak, dedicated to Amun-ra, is one of the largest and best surviving examples of this type of state-sponsored architecture.[49]

-

Gaming board inscribed for Amenhotep III with separate sliding drawer; 1390–1353 BC; glazed faience; 5.5 × 7.7 × 21 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Baboon figurine; 1390–1352 BC; quartzite; 68.5 × 38.5 × 45 cm, 180 kg (estimated); British Museum

-

Amarna art (c. 1350 BC)

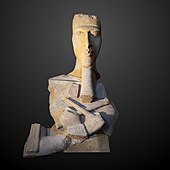

Amarna art is named for the extensive archeological site at Tel el-Amarna, where Pharaoh Akhenaten moved the capital in the late Eighteenth Dynasty. This period, and the years leading up to it, constitute the most drastic interruption in the style of Egyptian art in the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms as a result of the rising prominence of the New Solar Theology and the eventual shift towards Atenism under Akhenaten.[53] Amarna art is characterized by a sense of movement and a «subjective and sensual perception» of reality as it appeared in the world. Scenes often include overlapping figures creating the sensation of a crowd, which was less common in earlier times.

The artwork produced under Akhenaten was a reflection of the dramatic changes in culture, style, and religion that occurred under Akhenaten’s rule. Sometimes called the New Solar Theology, the new religion was a monotheistic worship of the sun, the Aten. Akhenaten placed emphasis on himself as the «co-regent», along with the Aten, as well as the mouthpiece of the Aten himself. Since the sun disk was worshiped at the ultimate life-giving power in this new theology, anything the sun’s rays touched were blessed by this force. As a result, sacrifices and worship were likely conducted in open courtyards and the sunken relief technique which works best for outdoors carvings was also used for indoor works.

Portrayal of the human body shifted drastically under the reign of Akhenaten. For instance, many depictions of Akhenaten’s body give him distinctly feminine qualities, such as large hips, prominent breasts, and a larger stomach and thighs. Facial representations of Akhenaten, such as in the sandstone Statue of Akhenaten, display him with an elongated chin, full lips, and hollow cheeks. These stylistic features extended past representations of Akhenaten and were further employed in the depiction of all figures of the royal family, as observed in the Portrait of Meritaten and Fragment of a queen’s face. This is a divergence from the earlier Egyptian art which emphasized idealized youth and masculinity for male figures.

A notable innovation from the reign of Akhenaten was the religious elevation of the royal family, including Akhenaten’s wife, Nefertiti, and their three daughters.[54] While earlier periods of Egyptian art depicted the king as the primary link between humanity and the gods, the Amarna period extended this power to those of the royal family.[54] As visualized in the relief of a royal family and the different talatat blocks, each figure of the royal family is touched by the rays of the Aten. Nefertiti specifically is believed to have held a significant cultic role during this period.[55]

Not many buildings from this period have survived, partially as they were constructed with standard-sized blocks, known as talatat, which were very easy to remove and reuse. Temples in Amarna, following the trend, did not follow traditional Egyptian customs and were open, without ceilings, and had no closing doors. In the generations after Akhenaten’s death, artists reverted to the traditional Egyptian styles of earlier periods. There were still traces of this period’s style in later art, but in most respects, Egyptian art, like Egyptian religion, resumed its usual characteristics as though the period had never happened. Amarna itself was abandoned and considerable effort was undertaken to deface monuments from the reign, including disassembling buildings and reusing the blocks with their decoration facing inwards, as has recently been discovered in one later building.[56] The last King of the Eighteenth Dynasty, Horemheb, sought to eliminate the influence of Amarna art and culture and reinstate the tradition powerful of the cult of Amun.[57]

-

Portrait of Meritaten; 1351–1332 BC; painted limestone; height: 15.4 cm; Louvre

-

Statue of Akhenaten; c. 1350 BC; painted sandstone; 1.3 × 0.8 × 0.6 m; Louvre

-

Talatat block with relief showing Nefertiti at prayer; circa 1350 BC; painted sandstone; height: 23.4 cm; from Karnak; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

Talatat block with Akhenaton standing to the right, raising his hands in prayer to the rays of the sun god Aten; circa 1350 BC; painted sandstone; from Karnak; Egyptian Museum of Berlin

-

Fragment of a queen’s face; 1353–1336 BC; yellow jasper; height: 13 cm, width: 12.5 cm, depth: 12.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Cosmetic dish in the shape of a trussed duck; 1353-1327 BC; hippopotamus ivory (tinted); duck (left), length: 9.5 cm, width: 4.6 cm; cover (right), length: 7.3 cm, width: 4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ramesside Period

With a concerted effort from Horemheb, the last King of Dynasty Eighteen, to eradicate all Amarna art and influence, the style of the art and architecture of the Empire transitioned into the Ramesside Period for the remainder of the New Kingdom (Nineteen and Twentieth Dynasties).[50] In response to the religious and artistic revolution of the Amarna period, state-commissioned works demonstrate a clear return to tradition forms and renewed dedication to Amun-ra. However, some elements of Amarna bodily proportion persist; the small of the back does not move back to its lower, Middle Kingdom, height and human limbs remain somewhat elongated. With some modifications, 19th and 20th Dynasty Kings continued to build their funerary temples, which were dedicated to Amun-ra and located in Thebes, in their predecessors’ style. The Ramses Kings also continued to build colossal statues such as those commissioned by Hatshepsut.[49]

During the Ramesside period kings made further contributions to the Temple at Karnak. The Great Hypostyle Hall, commissioned by Sety I (19th Dynasty), consisted of 134 sandstone columns supporting a 20-meter-high ceiling, and covering an acre of land. Sety I decorated most surfaces with intricate bas-relief while his successor, Ramses II added sunken relief work to the walls and columns in the southern side of the Great Hall. The interior carvings show king-god interactions, such as traditional legitimization of power scenes, processions, and rituals. Expansive depictions of military campaigns cover the exterior walls of Hypostyle Hall. Battle scenes illustrating chaotic, disordered enemies strewn over the conquered land and the victorious king as the most prominent figure, trademark the Ramesside period.[49]

The last period of the New Kingdom demonstrates a return to traditional Egyptian form and style, but the culture is not purely a reversion to the past. The art of the Ramesside period demonstrates the integration of canonized Egypt forms with modern innovations and materials. Advancements such as adorning all surfaces of tombs with paintings and relief and the addition of new funerary texts to burial chambers demonstrate the non-static nature of this period.[49]

Third Intermediate Period (c.1069–664 BC)

The Third Intermediate Period was one of decline and political instability, coinciding with the Late Bronze Age collapse of civilizations in the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean (including the Greek Dark Ages). It was marked by division of the state for much of the period and conquest and rule by foreigners.[58] After an early period of fracturation, the country was firmly reunited by the Twenty-second Dynasty founded by Shoshenq I in 945 BC (or 943 BC), who descended from Meshwesh immigrants, originally from Ancient Libya. The next period of the Twenty-fourth Dynasty saw the increasing influence of the Nubian kingdom to the south took full advantage of this division and the ensuing political instability. Then around 732 BC, Piye, marched north and defeated the combined might of several native Egyptian rulers: Peftjaubast, Osorkon IV of Tanis, Iuput II of Leontopolis and Tefnakht of Sais. He established the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of «Black Pharaos» originating from Nubia.

The Third Intermediate Period generally sees a return to archaic Egyptian styles, with particular reference to the art of the Old and Middle Kingdom.[59] The art of the period essentially consists in traditional Egyptian styles, with the inclusion of some foreign characteristics, such as the particular iconography of the statues of the Nubian rulers of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty.[59] Although the Twenty-fifth Dynasty controlled Ancient Egypt for only 73 years, it holds an important place in Egyptian history due to the restoration of traditional Egyptian values, culture, art, and architecture, combined with some original creations such as the monumental column of Taharqa in Karnak.[60][61] During the 25th dynasty Egypt was ruled from Napata in Nubia, now in modern Sudan, and the Dynasty in turn permitted the expansion of Egyptian architectural styles to Lower Egypt and Nubia.[59]

-

Pyramid of Piye, a Nubian king who conquered Upper Egypt and brought it under his control, at El-Kurru (Sudan)

-

Monumental column elevated by the «Black Pharaoh» Taharqa in Karnak[62]

-

Taharqa offering wine jars to Falcon-god Hemen;[62] 690–664 BC; bronze, greywacke, gold and wood; length: 26 cm, height: 19.7 cm, width: 10.3 cm; Louvre

Late Period (c. 664–332 BC)

In 525 BC, the political state of Egypt was taken over by the Persians, almost a century and a half into Egypt’s Late Period. By 404 BC, the Persians were expelled from Egypt, starting a short period of independence. These 60 years of Egyptian rule were marked by an abundance of usurpers and short reigns. The Egyptians were then reoccupied by the Achaemenids until 332 BC with the arrival of Alexander the Great. Sources state that the Egyptians were cheering when Alexander entered the capital since he drove out the immensely disliked Persians. The Late Period is marked with the death of Alexander the Great and the start of the Ptolemaic dynasty.[65] Although this period marks political turbulence and immense change for Egypt, its art and culture continued to flourish.

This can be seen in Egyptian temples starting with the Thirtieth Dynasty, the fifth dynasty in the Late Period, and extending into the Ptolemaic era.[citation needed] These temples ranged from the Delta to the island of Philae.[65] While Egypt underwent outside influences through trade and conquest by foreign states, these temples remained in the traditional Egyptian style with very little Hellenistic influence.[citation needed]

Another relief originating from the Thirtieth Dynasty was the rounded modeling of the body and limbs,[65] which gave the subjects a more fleshy or heavy effect. For example, for female figures, their breasts would swell and overlap the upper arm in painting. In more realistic portrayals, men would be fat or wrinkled.

Another type of art that became increasingly common during this period was the Horus stelae.[65] These originate from the late New Kingdom and intermediate period but were increasingly common during the fourth century to the Ptolemaic era. These statues would often depict a young Horus holding snakes and standing on some kind of dangerous beast. The depiction of Horus comes from the Egyptian myth where a young Horus is saved from a scorpion bite, resulting in his gaining power over all dangerous animals. These statues were used «to ward off attacks from harmful creatures, and to cure snake bites and scorpion stings».[65]

-

Egyptian man in a Persian costume, c. 343–332 BC, accession number 71.139, Brooklyn Museum.[66]

-

Magical stela or cippus of Horus; 332–280 BC; chlorite schist; height: 20.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BC)

Discoveries made since the end of the 19th century surrounding the (now submerged) ancient Egyptian city of Heracleion at Alexandria include a 4th century BC, unusually sensual, detailed and feministic (as opposed to deified) depiction of Isis, marking a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic forms beginning around the time of Egypt’s conquest by Alexander the Great in 332–331 BC. However, this was atypical of Ptolemaic sculpture, which generally avoided mixing Egyptian styles with the Hellenistic style used in the court art of the Ptolemaic dynasty,[67] while temples in the rest of the country continued using late versions of traditional Egyptian formulae.[68] Scholars have proposed an «Alexandrian style» in Hellenistic sculpture, but there is in fact little to connect it with Alexandria.[69]

Marble was extensively used in court art, although it all had to be imported and use was made of various marble-saving techniques, such as using a number of pieces attached with stucco; a head might have the beard, the back of the head and hair in separate pieces.[70] In contrast to the art of other Hellenistic kingdoms, Ptolemaic royal portraits are generalized and idealized, with little concern for achieving an individual portrait, though coins allow some portrait sculpture to be identified as one of the fifteen King Ptolemys.[71] Many later portraits have clearly had the face reworked to show a later king.[72] One Egyptian trait was to give much greater prominence to the queens than other successor dynasties to Alexander, with the royal couple often shown as a pair. This predated the 2nd century, when a series of queens exercised real power.[73]

In the 2nd century, Egyptian temple sculptures began to reuse court models in their faces, and sculptures of a priest often used a Hellenistic style to achieve individually distinctive portrait heads.[74] Many small statuettes were produced, with the most common types being Alexander, a generalized «King Ptolemy», and a naked Aphrodite. Pottery figurines included grotesques and fashionable ladies of the Tanagra figurine style.[68] Erotic groups featured absurdly large phalli. Some fittings for wooden interiors include very delicately patterned polychrome falcons in faience.

-

Ptolemy XII making offerings to Egyptian Gods, in the Temple of Hathor, 54 BC, Dendera, Egypt

-

Statue of the goddess Raet-Tawy; 332–30 BC; limestone; 46 × 13.7 × 23.7 cm; Louvre

-

Ibis coffin; 305–30 BC; wood, silver, gold, and rock crystal; 38.2 × 20.2 × 55.8 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Falcon box with wrapped contents; 332–30 BC; painted and gilded wood, linen, resin and feathers; 58.5 × 24.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Statue of a Ptolemaic king; 1st century BC; basalt; height: 82 cm, width: 39.5 cm; Louvre

Roman Period (30 BC–619 AD)

The Fayum mummy portraits are probably the most famous example of Egyptian art during the Roman period of Egypt. They were a type of naturalistic painted portrait on wooden boards attached to Upper class mummies from Roman Egypt. They belong to the tradition of panel painting, one of the most highly regarded forms of art in the Classical world. The Fayum portraits are the only large body of art from that tradition to have survived.

Mummy portraits have been found across Egypt, but are most common in the Faiyum Basin, particularly from Hawara (hence the common name) and the Hadrianic Roman city Antinoopolis. «Faiyum portraits» is generally used as a stylistic, rather than a geographic, description. While painted cartonnage mummy cases date back to pharaonic times, the Faiyum mummy portraits were an innovation dating to the time of the Roman occupation of Egypt.[76]

The portraits date to the Imperial Roman era, from the late 1st century BC or the early 1st century AD onwards. It is not clear when their production ended, but recent research suggests the middle of the 3rd century. They are among the largest groups among the very few survivors of the panel painting tradition of the classical world, which was continued into Byzantine and Western traditions in the post-classical world, including the local tradition of Coptic iconography in Egypt.

-

Mummy mask of a man; early 1st century AD; stucco, gilded and painted; 51.5 x 33 x 20 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

-

Plaster funerary portrait bust of a man from El Kharga, Upper Egypt Roman Period, 2nd century CE

-

Horus as emperor; 2nd century; bronze; height: 26.5 cm; Louvre

Characteristics of ancient Egyptian art

Egyptian art is known for its distinctive figure convention used for the main figures in both relief and painting, with parted legs (where not seated) and head shown as seen from the side, but the torso seen as from the front. The figures also have a standard set of proportions, measuring 18 «fists» from the ground to the hair-line on the forehead.[78] This appears as early as the Narmer Palette from Dynasty I, but this idealized figure convention is not employed in the use of displaying minor figures shown engaged in some activity, such as captives and corpses.[79] Other conventions make statues of males darker than those of females. Very conventionalized portrait statues appear from as early as the Second Dynasty (before 2,780 BC),[80] and with the exception of the art of the Amarna period of Ahkenaten[81] and some other periods such as the Twelfth Dynasty, the idealized features of rulers, like other Egyptian artistic conventions, changed little until the Greek conquest.[82] Egyptian art uses hierarchical proportions, where the size of figures indicates their relative importance. The gods or the divine pharaoh are usually larger than other figures while the figures of high officials or the tomb owner are usually smaller, and at the smallest scale are any servants, entertainers, animals, trees, and architectural details.[83]

Anonymity

Depiction of craftworkers in ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptian artists rarely left their names. The Egyptian artwork is anonymous also because most of the time it was collective. Diodorus of Sicily, who traveled and lived in Egypt, has written: «So, after the craftsmen have decided the height of the statue, they all go home to make the parts which they have chosen» (I, 98).[84]

Symbolism

Symbolism pervaded Egyptian art and played an important role in establishing a sense of order. The pharaoh’s regalia, for example, represented his power to maintain order. Animals were also highly symbolic figures in Egyptian art. Some colors were expressive.[85]

The ancient Egyptian language had four basic color terms: kem (black), hedj (white/silver), wadj (green/blue) and desher (red/orange/yellow). Blue, for example, symbolized fertility, birth, and the life-giving waters of the Nile.[86][failed verification] Blue and green were the colors of vegetation, and hence of rejuvenation. Osiris could be shown with green skin; in the 26th Dynasty, the faces of coffins were often colored green to assist in rebirth.[87]

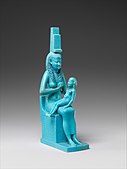

This color symbolism explains the popularity of turquoise and faience in funerary equipment. The use of black for royal figures similarly expressed the fertile alluvial soil[85] of the Nile from which Egypt was born, and carried connotations of fertility and regeneration. Hence statues of the king as Osiris often showed him with black skin. Black was also associated with the afterlife, and was the color of funerary deities such as Anubis.

Gold indicated divinity due to its unnatural appearance and association with precious materials.[85] Furthermore, gold was regarded by the ancient Egyptians as «the flesh of the god».[88] Silver, referred to as «white gold» by the Egyptians, was likewise called «the bones of the god».[88]

Red, orange and yellow were ambivalent colors. They were, naturally, associated with the sun; red stones such as quartzite were favored for royal statues which stressed the solar aspects of kingship. Carnelian has similar symbolic associations in jewelry. Red ink was used to write important names on papyrus documents. Red was also the color of the deserts, and hence associated with Set.

Materials

Faience

Egyptian faience is a ceramic material, made of quartz sand (or crushed quartz), small amounts of lime, and plant ash or natron. The ingredients were mixed together, glazed and fired to a hard shiny finish. Faience was widely used from the Predynastic Period until Islamic times for inlays and small objects, especially ushabtis. More accurately termed ‘glazed composition’, Egyptian faience was so named by early Egyptologists after its superficial resemblance to the tin-glazed earthenwares of medieval Italy (originally produced at Faenza). The Egyptian word for it was tjehenet, which means ‘dazzling’, and it was probably used, above all, as a cheap substitute for more precious materials like turquoise and lapis lazuli. Indeed, faience was most commonly produced in shades of blue-green, although a large range of colours was possible.[89]

-

-

Ushabti; 1294–1279 BC; faience; height: 28.1 cm, width: 9.2 cm; Louvre

-

Statuette of Isis and Horus; 332–30 BC; faience; height: 17 cm, width: 5.1 cm, depth: 7.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Bowl; 200–150 BC; faience; 4.8 × 16.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Glass

Although the glassy materials faience and Egyptian blue were manufactured in Egypt from an early period, the technology for making glass itself was only perfected in the early 18th Dynasty. It was probably imported from Levant, since the Egyptian words for glass are of foreign origin. The funerary objects of Amenhotep II included many glass artefacts, demonstrating a range of different techniques. At this period, the material was costly and rare, and may have been a royal monopoly. However, by the end of the 18th Dynasty, Egypt probably made sufficient quantities to export glass to other parts of the Eastern Mediterranean. Glass workshops have been excavated at Amarna and Pi-Ramesses. The raw materials – silica, alkali and lime – were readily available in Egypt, although ready-made ingots of blue glass were also imported from the Levant and have been found in the cargo of the Uluburun shipwreck off the southern coast of Turkey.[90]

-

Bottle; 1295–1070 BC; glass; height: 10 cm (4 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Small amphoriskos; 664–332 BC; glass; height: 7 cm (2.8 in); Metropolitan Museum of Art

Egyptian blue

Egyptian blue is a material related to, but distinct from, faience and glass. Also called «frit», Egyptian blue was made from quartz, alkali, lime and one or more coloring agents (usually copper compounds). These were heated together until they fused to become a crystalline mass of uniform color (unlike faience in which the core and the surface layer are of different colors). Egyptian blue could be worked by hand or pressed into molds, to make statuettes and other small objects. It could also be ground to produce pigment. It is first attested in the Fourth Dynasty, but became particularly popular in the Ptolemaic period and the Roman period, when it was known as caeruleum.[91]

The color blue was used only sparingly even up until as late as Dynasty IV, where the color was found adorning mat-patterns in the Tomb of Saccara, which was constructed during the first Dynasty. Until this discovery was made, the color blue had not been known in Egyptian art.[92]

-

Powder of Egyptian blue

-

Amphora, an example of so-called «Egyptian blue» ceramic ware; 1380–1300 BC; height: 12.6 cm (4.9 in); Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

Metals

While not a leading center of metallurgy, ancient Egypt nevertheless developed technologies for extracting and processing the metals found within its borders and in neighbouring lands.

Copper was the first metal to be exploited in Egypt. Small beads have been found in Badarian graves; larger items were produced in the later Predynastic Period, by a combination of mould-casting, annealing and cold-hammering. The production of copper artifacts peaked in the Old Kingdom when huge numbers of copper chisels were manufactured to cut the stone blocks of pyramids. The copper statues of Pepi I and Merenre from Hierakonpolis are rare survivors of large-scale metalworking.

The golden treasure of Tutankhamun has come to symbolize the wealth of ancient Egypt, and illustrates the importance of gold in pharaonic culture. The burial chamber in a royal tomb was called «the house of gold». According to the Egyptian religion, the flesh of the gods was made of gold. A shining metal that never tarnished, it was the ideal material for cult images of deities, for royal funerary equipment, and to add brilliance to the tops of obelisks. It was used extensively for jewelry, and was distributed to officials as a reward for loyal services («the gold of honour»).

Silver had to be imported from the Levant, and its rarity initially gave it greater value than gold (which, like electrum, was readily available within the borders of Egypt and Nubia). Early examples of silverwork include the bracelets of the Hetepheres. By the Middle Kingdom, silver seems to have become less valuable than gold, perhaps because of increased trade with the Middle East. The treasure from El-Tod consisted of a hoard of silver objects, probably made in the Aegean, while silver jewelry made for female members of the 12th Dynasty royal family was found at Dahshur and Lahun. In the Egyptian religion, the bones of the gods were said to be made of silver.[93]

Iron was the last metal to be exploited on a large scale by the Egyptians. Meteoritic iron was used for the manufacture of beads from the Badarian period. However, the advanced technology required to smelt iron was not introduced into Egypt until the Late Period. Before that, iron objects were imported and were consequently highly valued for their rarity. The Amarna letters refer to diplomatic gifts of iron being sent by Near Eastern rulers, especially the Hittites, to Amenhotep III and Akhenaten. Iron tools and weapons only became common in Egypt in the Roman Period.

-

Amun-Ra figurine; 1069–664 BC; silver and gold; 24 × 6 × 8.5 cm, 0.7 kg; British Museum (London)

Wood

Because of its relatively poor survival in archaeological contexts, wood is not particularly well represented among artifacts from Ancient Egypt. Nevertheless, woodworking was evidently carried out to a high standard from an early period. Native trees included date palm and dom palm, the trunks of which could be used as joists in buildings, or split to produce planks. Tamarisk, acacia and sycamore fig were employed in furniture manufacture, while ash was used when greater flexibility was required (for example in the manufacture of bowls). However, all these native timbers were of relatively poor quality; finer varieties had to be imported, especially from the Levant.[94]

-

Figurine of a female servant carrying provisions; 1981–1975 BC; painted wood and gesso; 112 × 17 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Model of a sailboat; 1981–1975 BC; painted wood, plaster, linen twine and linen fabric; length: 145 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Duck-shaped box; 16th–11th century BC; wood and ivory; Louvre

-

Lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli is a dark blue semi-precious stone highly valued by the ancient Egyptians because of its symbolic association with the heavens. It was imported via long-distance trade routes from the mountains of north-eastern Afghanistan, and was considered superior to all other materials except gold and silver. Coloured glass or faience provided a cheap imitation. Lapis lazuli is first attested in the Predynastic Period. A temporary interruption in supply during the Second and Third Dynasties probably reflects political changes in the ancient Near East. Thereafter, it was used extensively for jewelry, small figurines and amulets.[95]

-

Cult image of Ptah; 945–600 BC; height of the figure: 5.2 cm, height of the dais: 0.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Falcom amulet; 664–332 BC; height: 2.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Child god (Harpokrates?) amulet; 664–30 BC; height: 4.3 cm, width: 1.2 cm, depth: 1.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Other materials

- Jasper is an impure form of chalcedony with bands or patches of red, green or yellow. Red jasper, symbol of life and of positive aspects of the universe, was used above all to make amulets. It was ideal for certain amulets, such as the tit amulet, or tyet (also known as knot of Isis), to be made of red jasper, as specified in Spell 156 of the Book of the Dead. The more rarely used green jasper was especially indicated for making scarabs, particularly heart scarabs.

- Serpentine is the generic term for the hydrated silicates of magnesium. It came mostly from the eastern desert, and occurs in many shades of color, from a pale green to a dark verging on black. Used from the earliest times, it was sought specially for making heart scarabs.

- Steatite (also known as soapstone) is a mineral of the chlorite family; it has the great advantage of being very easy to work. Steatite amulets are found in contexts from the Predynastic Period on, although in subsequent periods it was usually covered in a fine layer of faience and was used in the manufacture of numerous scarabs.

- Turquoise is an opaque stone, sky blue to blue-green. It is a natural aluminium phosphate colored blue by traces of copper. Closely linked to the goddess Hathor, it was extracted mainly from mines in Sinai (at Serabit el-Khadim). The Egyptians were particularly fond of the greenish shades, symbolic of dynamism and vital renewal. In the Late Period, turquoise (like lapis lazuli) was synonymous with joy and delight.

-

Heart scarab of Hatnefer; 1492–1473 BC; serpentine (the scarab) and gold; 5.3 × 2.8 cm; chain: 77.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Head from a spoon in the form of a swimming girl; 1390–1353 BC; travertine (the head) and steatite (the hair); 2.8 × 2.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Amulet; 1295–1070 BC; red jasper; 2.3 × 1.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sculpture

The monumental sculpture of ancient Egypt’s temples and tombs is well known,[96] but refined and delicate small works exist in much greater numbers. The Egyptians used the technique of sunk relief, which is best viewed in sunlight for the outlines and forms to be emphasized by shadows. The distinctive pose of standing statues facing forward with one foot in front of the other was helpful for the balance and strength of the piece. This singular pose was used early in the history of Egyptian art and well into the Ptolemaic period, although seated statues were common as well.

Egyptian pharaohs were always regarded as gods, but other deities are much less common in large statues, except when they represent the pharaoh as another deity; however, the other deities are frequently shown in paintings and reliefs. The famous row of four colossal statues outside the main temple at Abu Simbel each show Rameses II, a typical scheme, though here exceptionally large.[97] Most larger sculptures survived from Egyptian temples or tombs; massive statues were built to represent gods and pharaohs and their queens, usually for open areas in or outside temples. The very early colossal Great Sphinx of Giza was never repeated, but avenues lined with very large statues including sphinxes and other animals formed part of many temple complexes. The most sacred cult image of a god in a temple, usually held in the naos, was in the form of a relatively small boat or barque holding an image of the god, and apparently usually in precious metal – none of these are known to have survived.