- Государство Русь в IX — начале X века

- Киевская Русь во времена правления династии Рюриковичей

- Монголо-татарское иго

- Киевская Русь во времена правления династии Рюриковичей

- Монголо-татарское иго

- Александр Невский и Ливонский орден

- Московское княжество

- Иван Грозный, смутное время, власть династии Романовых

- Российская империя

- Война с Наполеоном

- Декабристы и борьба с самодержавием

- Вторая половина XIX века

- Начало ХХ века

- Великая Отечественная и советско-японская войны

- Эпоха застоя

- Распад Советского Союза

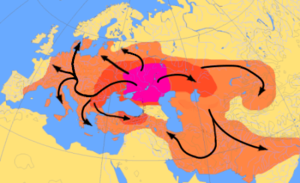

Начальные страницы российской истории связаны с племенами восточных славян, которые заселили Восточно-Европейскую равнину в VI-VII вв. Предки этих племен населяли Центральную и Восточную Европу, античные и византийские источники I-V вв. называли их по-разному: венеды, анты, склавины.

Источником пропитания для славянских племен были земледелие, скотоводство, промыслы: охота, рыболовство, собирательство. Племена восточных славян объединялись в союзы племен. Крупнейшими из них были: поляне, древляне, кривичи, вятичи, ильменские славяне. Древнейшая русская летопись, «Повесть временных лет», называет около десяти таких объединений

Историки долгое время спорили, с какого момента начинается история России как государства? Первая династия, правившая русским государством с IX по конец XVI в, берет свое начало с 862 года, когда согласно той же «Повести временных лет», ильменские славяне призвали на правление в Новгород варяжского князя Рюрика с дружиной.

Государство Русь в IX — начале X века

Возникновение нового государства, Киевской Руси, связано с еще одной летописной легендой. К IX веку на землях, заселенных славянскими племенами, сформировалось несколько политических центров со своими князьями во главе. Между ними постоянно происходили столкновения. К тому же, славянские племена подвергались внешнему давлению: были вынуждены платить дань соседнему государству, Хазарскому каганату. Чтобы прекратить внутренние раздоры и избавиться от хазарской угрозы, новгородцы и призвали варягов во главе с Рюриком, что было распространенной практикой в раннее средневековье.

Закрепившись в Старой Ладоге и Новгороде, Рюрик отправил в Византию двух своих дружинников, Аскольда и Дира. Последние, достигнув Киева, подчинили себе племена полян и стали княжить. Около 879 года умер князь Рюрик, после него остался малолетний сын Игорь, пока мальчик рос, князем и его опекуном стал Олег. В 882 г. он отправился в поход на Киев, убил Аскольда и Дира и объединил под своей властью два крупнейших городских центра восточных славян. Именно эта дата сегодня считается датой возникновения Древнерусского государства.

Киевская Русь во времена правления династии Рюриковичей

Преемником Олега стал Игорь, сын Рюрика, который подчинил славянские племена, обитавшие между Днестром и Дунаем, воевал с Константинополем, печенегами. Игорь был убит древлянами в 945 году, когда пытался во второй раз собрать с них дань.

После смерти Игоря во главе государства встала Ольга, жена князя, которая правила до совершеннолетия сына Святослава и первой среди правителей Руси приняла христианство. Преемник Святослава Владимир прославился обращением всей Руси в христианство, что укрепило княжескую власть и повысило международный статус Древнерусского государства. Наивысшего расцвета Киевская Русь достигла при Ярославе Мудром, правившем с 1016 по 1054 год. При нем был создан первый письменный свод законов, «Русская правда». Благодаря междинастическим бракам удалось укрепить связи с соседними державами.

После смерти Ярослава начались междоусобные войны. Последним князем, которому удавалось сохранять целостность Древнерусского государства, был Владимир Мономах. Современники называли его образцовым князем. Своим детям он оставил своего рода политическое завещание «Поучение», однако те не вняли отцу. Междоусобная борьба вспыхнула с новой силой и к середине XII столетия государство оказалось расколото на самостоятельные княжества.

Монголо-татарское иго

Монголы, населявшие земли Центральной Азии, занимались скотоводством, вели кочевнический образ жизни и для расширения пастбищных территорий совершали набеги на соседние государства. В 1206 году у них возникло государство: на съезде знати Темучин был провозглашен правителем всех монголов и получил имя Чингисхан. Опустошив Азию и Закавказье, в начале XIII века войска кочевников двинулись в направлении Руси. В 1223 году на реке Калка армия, возглавляемая сподвижниками Чингисхана, разбила войско киевского князя Мстислава вместе с его союзниками – половцами. Одержав победу, орда вернулась обратно в степи.

В 1237 году в поход на Русь двинулся внук Чингисхана – хан Батый, которому удалось захватить Рязань, Коломну, Москву, а к 1240-му Чернигов и Киев. Монголо-татарское войско вернулось на приволжские территории, где было основана держава Золотая Орда. Русские города ежегодно платили ордынским ханам дань, отправляли строителей и ремесленников для строительства и обслуживания золотоордынских городов. Русь находилась под игом кочевников вплоть до 1480 года и за это время значительно отстала в экономическом и культурном развитии от европейских государств.

Александр Невский и Ливонский орден

Ослабленная татаро-монгольским нашествием Русь подверглась нападению западных соседей. Шведы и рыцари Ливонского ордена напали почти одновременно, угрожая захватом Новгорода. Атака шведского флота на Неве в 1240 году была отбита русскими воинами во главе с князем Александром Ярославовичем, названным впоследствии Невским. В 1242 году на Чудском озере состоялось Ледовое побоище, в котором рыцари также потерпели полное поражение. После целого ряда последующих побед русского оружия, западные агрессоры отказались от притязаний на русские земли.

Московское княжество

В XIV веке русские земли вновь начали объединяться, центром объединения стала Москва. Рост и процветание Москвы связаны прежде всего с нахождением на пересечении водных и сухопутных торговых путей, а также с грамотной политикой местных князей. В 1301 году к Московскому княжеству был присоединен Переяславль-Рязанский, Коломна, еще через год – Можайск.

В период правления Ивана I Калиты, внука Александра Невского, Москва превратилась в экономический и культурный центр Северо-Восточной Руси. Ее конкурентом выступало Тверское княжество. Важным шагом в этом соперничестве стало перенесение резиденции митрополита из Владимира в Москву. Не менее важна была и готовность московских князей сотрудничать с ордынскими ханами, что приводило к ослаблению гнета со стороны Орды. В княжестве стремительно развивались ремесла и торговля, на московские земли съезжались люди со всех остальных территорий Руси.

В 1380-м Дмитрий Донской, внук Ивана Калиты, разбил монголо-татарское войско на Куликовом поле. Во время правления Ивана III Москва прекратила платить дань ордынцам, в 1480 году была одержана окончательная победа над захватчиками. Им же был присоединен к Москве Новгород, один из крупнейших политических центров того времени.

Завершение объединения русских земель связано с именем Василия III, при нем в состав Московского государства вошли Псков и Рязань.

Иван Грозный, смутное время, власть династии Романовых

Василию III в 1533 г. наследовал его 3-летний сын, Иван IV. До совершеннолетия мальчика, регентом стала его мать, Елена Глинская, которой удалось провести ряд реформ до своей смерти в 1538 году. Реальная власть перешла в руки боярских кланов, приближенных к великокняжескому двору. Только в 1547 Иван IV был венчан на царство и власть вернулась в руки Рюриковичей. При нем был проведен ряд реформ в военной, судебной системах, в сфере государственного правления. К Русскому государству были присоединены: Астраханское, Казанское ханства, Западная Сибирь, Башкирия, территории Ногайской орды, начало зарождаться крепостное право. Однако, называть Ивана IV Грозным стали не за реформы. В его правление была проиграна затяжная Ливонская война и введена опричнина. Царь отличался особой жестокостью к инакомыслящим. Боясь притязаний на власть, царь расправлялся со своими родственниками – удельными князьями.

Последним царем из династии Рюриковичей был сын Ивана Федор, болезненный человек, не способный управлять государством. После его смерти престол занял боярин Борис Годунов. Смутные времена – эпидемия холеры, противостояние с поляками и шведами, неурожаи и народные восстания – ослабили положение государственной власти, чем воспользовался самозванец, выдавший себя за сына Ивана Грозного Дмитрия и пообещавший отдать полякам часть русских земель, за что те помогли ему захватить Москву. Но удержаться в столице долго Лжедмитрий не сумел, его место занял Василий Шуйский. Вскоре появился еще один самозванец, Лжедмитрий II. Шведы и поляки воспользовались внутренними раздорами и оккупировали многие русские территории. Решающую роль в этот критический момент сыграл русский народ. Собрав ополчение, которым руководили князь Дмитрий Пожарский и Кузьма Минин, удалось изгнать самозванца и иностранных интервентов. «Смута» закончилась избранием на престол Михаила Романова в 1613 году.

Российская империя

«Смута» привела к значительному отставанию России от стран Европы. Развитие торговли сдерживалось отсутствием выхода к незамерзающим морям, армия и система управления государством требовали изменений. Выдающимся реформатором, которому удалось радикально изменить государственный уклад стал Петр I. Он был провозглашен царем в 10-летнем возрасте, но до 17 лет он делил престол с братом Иваном под регентством старшей сестры, царевны Софьи.

При Петре I окончательно сформировалось дворянское сословие. Был основан Санкт-Петербург, ставший новой столицей государства. Систему приказов сменили коллегии, которые служили прообразом современных министерств, церковь была поставлена в зависимость от государства. Придворные, военные и гражданские звания были разделены на 14 рангов. В стране появились школы первой ступени, профессиональные училища, была открыта академия наук, появилась сеть типографий. Победа в Северной войне, длившейся около 20 лет, позволила России не только вернуть ранее захваченные шведами территории, получить выход к Балтийскому морю, но и значительно повысить свой международный статус. После нее, в 1721 году Российское государство было провозглашено империей, а сам Петр I стал именоваться императором и самодержцем Всероссийским.

После смерти императора началась эпоха дворцовых переворотов, продолжавшаяся почти сорок лет.

В 1762 на престол взошла Екатерина II, которая правила государством 30 лет. Императрица покровительствовала развитию науки и искусства, но в то же время способствовала укреплению крепостного права. Эксплуатация крестьян и существенное ограничение их прав привели к массовым восстаниям крестьян, работников, казаков. Наиболее масштабное событие – крестьянская война под предводительством казака Емельяна Пугачева. Стихийность войны, неорганизованность, предательство атамана зажиточными соратниками привели к подавлению восстания, сам Пугачев был казнен в Москве.

Екатерине II удалось присоединить к России Крым, Кубань, Грузию, отвоевать у Турции выход к Черному морю. После распада Речи Посполитой к России отошли земли теперешних Украины и Беларуси, Литвы, Курляндии (западная часть Латвии).

Война с Наполеоном

После смерти Екатерины государством стал управлять ее сын Павел I, который освободил узников, лишенных свободы его матерью, попытался ограничить барщину для крепостных крестьян тремя днями в неделю. В 1799 году армии под командованием Александра Суворова перешли через Альпы и освободили итальянскую Ломбардию от французов. Неуравновешенность и вспыльчивость Павла, его попытки ограничения дворянских прав и разрыв отношений с Англией привели к возникновению заговора против императора. Он был убит 11 марта 1801 г.

Наследник Павла, Александр I, частично разделял взгляды бабушки. Он снял ограничения на торговые отношения с англичанами, амнистировал заключенных не угодных Павлу. Император принял Указ о вольных хлебопашцах, дававший возможность выхода работников на волю и выкупа земель.

Во внешней политике Александр колебался в выборе союзника между Англией и Францией. Проиграв битву под Аустерлицем (Австрия) в 1805 году, правитель через два года подписал с французами мирный договор.

Тем не менее, войны избежать не удалось. В 1812-м наполеоновские солдаты вторглись в Россию. Русским армиям приходилось отступать на восток, в августе российским войскам удалось объединиться под Смоленском, но отступление продолжалось. Судьба Москвы решалась в Бородинском сражении. Несмотря на огромные потери французской армии, Москву все же пришлось сдать неприятелю. Но пожары в Москве, голод и мародерство заставили захватчиков оставить город. После поражения французов под Малоярославцем им оставалось только бежать из России. Возвращение по разоренной дороге и нападения партизан полностью обескровили наполеоновскую армию. Окончательно наполеоновские войска были разбиты в сражении у реки Березины. Вслед за французами русская армия прошла по Восточной и Центральной Европе и в 1814 году достигла Парижа.

Декабристы и борьба с самодержавием

Во время заграничного похода многие русские дворяне-офицеры увлеклись революционными идеями. Вернувшись на родину, они стали объединяться, чтобы способствовать их воплощению в жизнь. Первое тайное общество появилось в 1816 году и называлось «Союз спасения». Его участники, будущие декабристы, выступали за принятие конституции и отмену крепостного права. Организация была малочисленной и быстро распалась.

В 1821 году были сформированы «Северное общество» в России (основатели – Никита Муравьев, Николай Тургенев), «Южное общество» – на территории Украины (во главе – Павел Пестель). Общества разработали конституционные проекты «Конституцию» и «Русскую правду». В обоих документах провозглашались свержение самодержавия и отмена крепостничества.

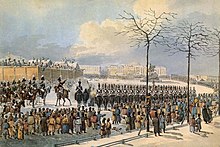

14 декабря 1825 года «Северное общество» устроило восстание в Петербурге, воспользовавшись неожиданной смертью Александра I и отказом от власти его брата, Константина. 29 декабря на юге восстал Черниговский полк. Оба бунта были жестоко подавлены, руководители восстания были казнены, а большая часть декабристов сослана в Сибирь.

Вторая половина XIX века

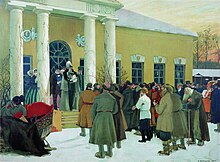

Поражение в Крымской войне 1853–1856 годов показало отсталость России и подорвало авторитет страны на мировой арене. Государство нуждалось в переменах. Император Александр II во время своего правления провел ряд важных реформ: в 1861-м отменил крепостное право, создал органы местного самоуправления – земства, расширил полномочия городских властей, ввел суд присяжных, реформировал систему образования и военное дело. Однако крестьяне по-прежнему платили подать и несли рекрутскую повинность. В обществе росло недовольство, усилились революционные настроения. Александр II был убит 1 марта 1881 г.

Начало ХХ века

В январе 1905 года вспыхнуло восстание рабочих в Петербурге, его участники были расстреляны. Это, в совокупности с неудачами в ходе русско-японской войны, привело к началу революции 1905-1906 годов.

В дальнейшем ситуацию в стране ухудшило участие в Первой мировой войне, в которой Россия понесла огромные потери. В результате Февральской революции 1917 года царь Николай II отрекся от престола, уже осенью к власти пришли большевики. В 1918–1922 годах на территории государства шла гражданская война между большевиками, сторонниками временного правительства и бандами анархистов. Постепенно, большевикам удалось установить свою власть на большей части территорий бывшей Российской империи. В 1922 году был образован СССР. В 1920-е годы произошло непродолжительное возвращение к элементам рыночной экономики и сотрудничеству с европейскими государствами, получившее название новой экономической политики. Начиная с конца 1920-х годов, государственная политика в довоенные годы была направлена на коллективизацию сельского хозяйства и индустриализацию.

Великая Отечественная и советско-японская войны

22 июня 1941 года немецкие войска вторглись в Советский Союз. Несмотря на героическое сопротивление советских солдат за первый месяц войны пришлось оставить почти всю Прибалтику, Белоруссию и большую часть Украины, Молдавию. Двухмесячное Смоленское сражение задержало продвижение врага и нарушило план молниеносного разгрома СССР. Положение становилось все тяжелее, в августе в осаде оказался Ленинград. К началу декабря 1941 года фашистские позиции располагались на ближайших подступах к Москве. 5-6 декабря, благодаря героическому упорству советских солдат, удалось начать контрнаступление от Калинина (Тверь) до Ельца. Это было первое крупное поражение гитлеровских войск после 1939 года. Война приняла затяжной характер.

Героизм, проявленный советскими войсками в сражениях 1942-1943 годов позволил совершить коренной перелом в ходе войны. Сталинградская битва, Курская дуга, освобождение Кавказа: несмотря на огромные потери красноармейцы продолжали отстаивать свободу своей Родины. Огромный вклад в дело победы над врагом внесли и партизанские отряды, действовавшие на оккупированных территориях.

В январе 1944 года была снята блокада Ленинграда, а летом удалось освободить территорию Белоруссии. 7 ноября последние немецкие солдаты покинули пределы СССР и начался освободительный поход советских войск по Восточной и Центральной Европе. 9 мая 1945 года в 0:43 по московскому времени был подписан акт о капитуляции Германии, завершивший Великую отечественную войну.

В августе 1945 года, выполняя союзные обязательства, СССР вступил в войну с Японией, поддерживавшей Гитлера. Капитуляция Японии 2 сентября 1945 года положила конец Второй мировой войне.

Эпоха застоя

После победы над фашизмом в сферу влияния СССР попали Польша, Чехословакия, ГДР, Венгрия, Румыния, Болгария. Отношения с Западной Европой и США после кратковременного потепления вновь стали натянутыми. Особенно сильной была конфронтация с Соединенными Штатами. Противоборство социалистического и капиталистического лагеря достигло пика в начале 60-х и чуть не дошло до открытого конфликта осенью 1962 года. К 1970-м отношения с Западом нормализовались. Во второй половине 70-х Советский Союз был на первый взгляд благополучной стабильной державой, однако в своем развитии значительно отставал от капиталистических стран.

Распад Советского Союза

В 1985 году генеральным секретарем ЦК КПСС был избран Михаил Горбачев, который объявил курс на «перестройку» – ускорение экономического развития, утверждение свободы слова. Рыночные реформы не были восприняты советским населением, финансовое положение народа ухудшилось, усилилась инфляция, ощущался дефицит продуктов и промтоваров. Непоследовательная политика Горбачева в итоге привела к распаду СССР в 1991 году. Россия наряду с другими союзными республиками вошла в состав Содружества независимых государств. Конституция РФ была принята в 1993 году.

Конспекты «ИСТОРИЯ РОССИИ»

Изучение Истории России шаг за шагом. Онлайн-учебник.

История России – это очень длительный период становления великой державы, который берет свое начало, тогда когда еще не было самого государства, как такового, и продолжается, по сей день. В настоящее время Российская Федерация является исторической преемницей предшествующих форм непрерывной государственности с 862 года: Древнерусского государства (862—1240), Великого княжества Владимирского (1157—1389), Московского княжества (1263—1547), Русского царства (1547—1721), Российской империи (1721—1917), Российской республики (1917), Российской Советской Федеративной Социалистической Республики (1917—1922, с 1922 года республика в составе СССР) и Союза Советских Социалистических Республик (1922—1991).

Не понимая прошлое — нельзя понять настоящее

и спрогнозировать будущее!

Исторические события — не хаос, ничего не происходит просто так, большая часть процессов истории имеет вполне закономерную природу. Простой пример: классическая схема революционной ситуации, «верхи не могут, а низы не хотят». Или другой пример: «тяжёлые времена создают сильных людей, сильные люди — хорошие времена, хорошие времена порождают слабых людей, слабые люди — тяжёлые времена».

Конечно же, история не движется по какому-то одному и тому же пути, по одной и той же «спирали», циклично возвращаясь на прежние точки графика по мере хода лет и веков. История — это несколько разных спиралей, составляющих общий исторический процесс. Выражение «история движется по спирали» означает, что событиям в ней свойственно повторяться, но уже на новом историческом витке, в новых условиях и обстоятельствах. Французскую революцию 1789 года часто сопоставляют с Октябрьской революцией 1917 года в России. В них историки находят много общего. И в судьбе убитых монархов, и в их последовательном развитии от революционной романтики — к террору, а затем — к зарождению имперского сознания.

Изучение истории похоже на изучение шахмат: люди изучают огромный массив сыгранных когда-либо партий, потому что все ситуации уже когда-то были, и разные решения игроков в них давали какие-то результаты, поддающиеся анализу и способные стать основой для текущей тактики и стратегии.

Кодификатор ОГЭ

Проверь свои знания

Кодификатор ЕГЭ

Часть 1. С древнейших времен до конца XVI века .

Часть 2. С конца XVI до конца XVIII века.

Часть 3. С XIX до начала XX века.

Часть 4. С XX до начала XXI века.

(другие конспекты готовятся к публикации)

Кодификатор ОГЭ

Проверь свои знания

Кодификатор ЕГЭ

Источники идей и источники цитат для конспектов по «Истории России»:

- Новый полный справочник для подготовки к ЕГЭ/ П.А.Баранов, С.В.Шевченко — М.: АСТ: Астрель, 2014

- Кацва Л.А. «История Отечества: справочник для старшеклассников и поступающих в ВУЗы»/ под н/р В.Р.Лещинера — М.: АСТ-ПРЕСС КНИГА, 2012

- Гильда Нагаева: Памятка по истории России — Феникс, 2014

- Головко А.В. «ОГЭ. История: универсальный справочник» — Москва: Эксмо, 2016

- МГУ им. М.В.Ломоносова. Исторический факультет: А.С.Орлов, В.А.Георгиев, Н.Г.Георгиева, Т.А.Сивохина «История России с древнейших времен до наших дней. Учебник» — М.: ПБОЮЛ Л.В.Рожников, 2001.

- История/ С.И.Кужель — Москва: Эксмо (Наглядный школьный курс: удобно и понятно).

- История: полный курс в таблицах и схемах: 6-9 классы / П.А. Баранов — Москва: АСТ (Подготовка к ОГЭ).

- Хуторской Владимир Яковлевич / История России (IX-XX века). Пособие для подготовки к ЕГЭ: Причины и следствия. Анализ событий с учетом новейшие научных данных.

- Полный курс истории для учителей, преподавателей и студентов. В 4-х книгах / Е.Ю. Спицын. – М.: Концептуал

- История России. Пособие для абитуриентов МГИМО МИД РФ в 3-х книгах/ Т.Черникова, Я. Вишняков, О. Обичкин. – М.: Р.Валент

(с) Цитаты из вышеуказанных учебных пособий использованы на сайте в незначительных объемах, исключительно в учебных и информационных целях (пп. 1 п. 1 ст. 1274 ГК РФ).

Восточные славяне

Предки славян — праславяне — издавна жили на территории Центральной и Восточной Европы. По языку они относятся к индоевропейской группе народов, которые населяют Европу и часть Азии вплоть до Индии. Первые упоминания о праславянах относятся к I—II вв. Римские авторы Тацит, Плиний, Птолемей называли предков славян венедами и считали, что они населяли бассейн реки Вислы. Более поздние авторы — Прокопий Кесарийский и Иордан (VI век) разделяют славян на три группы: склавины, жившие между Вислой и Днестром, венеды, населявшие бассейн Вислы, и анты, расселившиеся между Днестром и Днепром. Именно анты считаются предками восточных славян.

Подробные сведения о расселении восточных славян дает в своей знаменитой «Повести временных лет» монах Киево-Печерского монастыря Нестор, живший в начале XII века. В своей летописи Нестор называет около 13 племен (ученые считают, что это были племенные союзы) и подробно описывает их места расселения.

Около Киева, на правом берегу Днепра, жили поляне, по верхнему течению Днепра и Западной Двине — кривичи, по берегам Припяти — древляне. На Днестре, Пруте, в нижнем течении Днепра и на северном побережье Черного моря жили уличи и тиверцы. Севернее их жили волыняне. От Припяти до Западной Двины расселились дреговичи. По левому берегу Днепра и вдоль Десны жили северяне, по реке Сож — притоку Днепра — радимичи. Вокруг озера Ильмень проживали ильменские словене.

Соседями восточных славян на западе были прибалтийские народы, западные славяне (поляки, чехи), на юге — печенеги и хазары, на востоке — волжские болгары и многочисленные угро-финские племена (мордва, марийцы, мурома).

Основными занятиями славян были земледелие, которое в зависимости от почвы было подсечно-огневым или переложным, скотоводство, охота, рыболовство, бортничество (сбор меда диких пчел).

В VII-VIII веках в связи с улучшением орудий труда, переходу от залежной или переложной системы земледелия к двухпольной и трехпольной системе севооборота, у восточных славян происходит разложение родового строя, рост имущественного неравенства.

Развитие ремесла и его отделение от земледелия в VIII-IX веках привело к возникновению городов — центров ремесла и торговли. Обычно города возникали при слиянии двух рек или на возвышенности, поскольку такое расположение позволяло гораздо лучше защищаться от врагов. Древнейшие города часто образовывались на важнейших торговых путях или на их пересечении. Главным торговым путем, проходившим через земли восточных славян, был путь «из варяг в греки », из Балтийского моря в Византию.

В VIII — начале IX веков у восточных славян выделяется родо-племенная и военно-дружинная знать, устанавливается военная демократия. Вожди превращаются в племенных князей, окружают себя личной дружиной. Выделяется знать. Князь и знать захватывают племенную землю в личную наследственную долю, подчиняют своей власти бывшие родо-племенные органы управления.

Накапливая ценности, захватывая земли и угодья, создавая мощную военную дружинную организацию, совершая походы с целью захвата военной добычи, собирая дань, торгуя и занимаясь ростовщичеством, знать восточных славян превращается в силу, стоящую над обществом и подчинившую себе ранее свободных общинников. Таков был процесс классообразования и формирования ранних форм государственности у восточных славян. Этот процесс постепенно привел к образованию на Руси в конце IX века раннефеодального государства.

Государство Русь в IX — начале X века

На территории, занятой славянскими племенами, образовалось два русских государственных центра: Киев и Новгород, каждый из которых контролировал определенную часть торгового пути «из варяг в греки».

В 862 г., согласно «Повести временных лет», новгородцы, желая прекратить начавшуюся междоусобную борьбу, пригласили варяжских князей управлять Новгородом. Прибывший по просьбе новгородцев варяжский князь Рюрик стал основателем русской княжеской династии.

Датой образования древнерусского государства условно считается 882 г., когда князь Олег, захвативший после смерти Рюрика власть в Новгороде, предпринял поход на Киев. Убив правящих там Аскольда и Дира, он объединил северные и южные земли в составе единого государства.

Легенда о призвании варяжских князей послужила основанием для создания так называемой норманнской теории возникновения древнерусского государства. Согласно этой теории, русские обратились к норманнам (так тогда называ-

ли выходцев из Скандинавии) для того, чтобы те навели порядок на русской земле. В ответ на Русь пришли трое князей: Рюрик, Синеус и Трувор. После смерти братьев Рюрик объединил под своей властью всю новгородскую землю.

Основанием для подобной теории стало укоренившееся в трудах немецких историков положение об отсутствии предпосылок для образования государства у восточных славян.

Последующие исследования опровергли эту теорию, поскольку определяющим фактором в процессе образования любого государства являются объективные внутренние условия, без наличия которых никакими внешними силами его создать невозможно. С другой стороны, рассказ об иноземном происхождении власти достаточно типичен для средневековых хроник и встречается в древних историях многих европейских государств.

После объединения новгородских и киевских земель в единое раннефеодальное государство киевский князь стал называться «великим князем». Он правил при помощи совета, состоящего из других князей и дружинников. Сбор дани осуществлялся самим великим князем при помощи старшей дружины (так называемые бояре, мужи). Была у князя младшая дружина (гриди, отроки). Древнейшей формой сбора дани было «полюдье». Поздней осенью князь объезжал подвластные ему земли, собирая дань и верша суд. Четко установленной нормы сдачи дани не было. Всю зиму князь проводил, объезжая земли и собирая дань. Летом же князь со своей дружиной обычно совершал военные походы, подчиняя славянские племена и воюя с соседями.

Постепенно все большая часть княжеских дружинников становилась земельными собственниками. Они вели собственное хозяйство, эксплуатируя труд закабаляемых ими крестьян. Постепенно такие дружинники усиливались и уже могли в дальнейшем противостоять великому князю как своими собственными дружинами, так и своей экономической силой.

Социальная и классовая структура раннефеодального государства Русь была нечеткой. Класс феодалов был пестр по своему составу. Это были великий князь с его приближенными, представители старшей дружины, ближайшее окружение князя — бояре, местные князья.

К числу зависимого населения принадлежали холопы (люди, утратившие свободу в результате продажи, долгов и т.п.), челядь (те, кто потерял свободу в результате плена), закупы (крестьяне, получившие от боярина «купу» — ссуду деньгами, зерном или тягловой силой) и др. Основную массу сельского населения составляли свободные общинники-смерды. По мере захвата их земель они превращались в феодально-зависимых людей.

Княжение Олега

После захвата Киева в 882 г. Олег подчинил себе древлян, северян, радимичей, хорватов, тиверцев. Успешно воевал Олег с хазарами. В 907 г. он осадил столицу Византии Константинополь, а в 911 г. заключил с ней выгодный торговый договор.

Княжение Игоря

После смерти Олега великим князем киевским стал сын Рюрика Игорь. Он подчинил восточных славян, живших между Днестром и Дунаем, воевал с Константинополем, первым из русских князей столкнулся с печенегами. В 945 г. он был убит в земле древлян при попытке вторично собрать с них дань.

Княгиня Ольга, княжение Святослава

Вдова Игоря Ольга жестоко подавила восстание древлян. Но при этом она определила фиксированный размер дани, организовала места для сбора дани — становища и погосты. Так была установлена новая форма сбора дани — так называемый «повоз». Ольга посетила Константинополь, где приняла христианство. Она правила в период малолетства своего сына Святослава.

В 964 г. в правление Русью вступает достигший совершеннолетия Святослав. При нем до 969 г. государством в значительной мере правила сама княгиня Ольга, так как ее сын почти всю жизнь провел в походах. В 964-966 гг. Святослав освободил вятичей от власти хазар и подчинил их Киеву, разгромил Волжскую Булгарию, Хазарский каганат и взял столицу каганата город Итиль. В 967 г. он вторгся в Болгарию и

обосновался в устье Дуная, в Переяславце, а в 971 г. в союзе с болгарами и венграми начал воевать с Византией. Война была неудачной для него, и он был вынужден заключить мир с византийским императором. На обратном пути в Киев Святослав Игоревич у днепровских порогов погиб в бою с печенегами, предупрежденными византийцами о его возвращении.

Князь Владимир Святославович

После смерти Святослава между его сыновьями началась борьба за правление в Киеве. Победителем из нее вышел Владимир Святославович. Походами на вятичей, литовцев, радимичей, болгар Владимир укрепил владения Киевской Руси. Для организации обороны от печенегов он установил несколько оборонительных рубежей с системой крепостей.

Для укрепления княжеской власти Владимир предпринял попытку превратить народные языческие верования в государственную религию и для этого установил в Киеве и Новгороде культ главного славянского дружинного бога Перуна. Однако эта попытка оказалась неудачной, и он обратился к христианству. Эта религия была объявлена единственной общерусской религией. Сам Владимир принял христианство из Византии. Принятие христианства не только уравняло Киевскую Русь с соседними государствами, но и оказало огромное влияние на культуру, быт и нравы древней Руси.

Ярослав Мудрый

После смерти Владимира Святославовича между его сыновьями началась ожесточенная борьба за власть, завершившаяся победой в 1019 г. Ярослава Владимировича. При нем Русь стала одним из сильнейших государств Европы. В 1036 г. русские войска нанесли крупное поражение печенегам, после чего их набеги на Русь прекратились.

При Ярославе Владимировиче, прозванном Мудрым, начал оформляться единый для всей Руси судебный кодекс — «Русская Правда». Это был первый документ, регулирующий взаимоотношения княжеских дружинников между собой и с жителями городов, порядок разрешения различных споров и возмещения ущерба.

Важные реформы при Ярославе Мудром были проведены в церковной организации. В Киеве, Новгороде, Полоцке были построены величественные соборы святой Софии, что должно было показать церковную самостоятельность Руси. В 1051 г. киевский митрополит был избран не в Константинополе, как прежде, а в Киеве собором русских епископов. Была определена церковная десятина. Появляются первые монастыри. Канонизированы первые святые — братья князья Борис и Глеб.

Киевская Русь при Ярославе Мудром достигла своего наивысшего могущества. Поддержки, дружбы и родства с ней искали многие крупнейшие государства Европы.

Феодальная раздробленность на Руси

Однако наследники Ярослава — Изяслав, Святослав, Всеволод — не смогли сохранить единства Руси. Междоусобицы братьев привели к ослаблению Киевской Руси, чем воспользовался новый грозный враг, объявившийся на южных границах государства, — половцы. Это были кочевники, вытеснившие живших здесь ранее печенегов. В 1068 г. объединенные войска братьев Ярославичей были разбиты половцами, что привело к восстанию в Киеве.

Новое восстание в Киеве, вспыхнувшее после смерти киевского князя Святополка Изяславича в 1113 г., вынудило киевскую знать призвать на княжение Владимира Мономаха, внука Ярослава Мудрого, властного и авторитетного князя. Владимир был вдохновителем и непосредственным руководителем военных походов против половцев в 1103, 1107 и 1111 гг. Став киевским князем, он подавил восстание, но в то же время был вынужден законодательным путем несколько смягчить положение низов. Так возник устав Владимира Мономаха, который, не покушаясь на основы феодальных отношений, стремился несколько облегчить положение крестьян, попавших в долговую кабалу. Тем же духом проникнуто и «Поучение» Владимира Мономаха, где он выступал за установление мира между феодалами и крестьянами.

Княжение Владимира Мономаха было временем усиления Киевской Руси. Он сумел объединить под своей властью значительные территории древнерусского государства и прекратить княжеские междоусобицы. Однако после его смерти феодальная раздробленность на Руси вновь усилилась.

Причина этого явления заключалась в самом ходе экономического и политического развития Руси как феодального государства. Укрепление крупного землевладения — вотчин, в которых господствовало натуральное хозяйство, привело к тому, что они стали самостоятельными производственными комплексами, связанными с их ближайшим окружением. Города становились экономическими и политическими центрами вотчин. Феодалы превратились в полных хозяев на своей земле, независимых от центральной власти. Победы Владимира Мономаха над половцами, временно устранившие военную угрозу, также способствовали разобщению отдельных земель.

Киевская Русь распалась на самостоятельные княжества, каждое из которых по размерам территории можно было сравнить со средним западноевропейским королевством. Это были Черниговское, Смоленское, Полоцкое, Переяславское, Галицкое, Волынское, Рязанское, Ростово-Суздальское, Киевское княжества, Новгородская земля. В каждом из княжеств не только существовал свой внутренний порядок, но и проводилась самостоятельная внешняя политика.

Процесс феодальной раздробленности открыл дорогу для упрочения системы феодальных отношений. Однако у него оказалось несколько отрицательных последствий. Разделение на самостоятельные княжества не прекратило княжеские усобицы, а сами княжества начали дробиться между наследниками. Кроме того, внутри княжеств началась борьба между князьями и местными боярами. Каждая из сторон стремилась к наибольшей полноте власти, призывая на свою сторону для борьбы с противником иностранные войска. Но самое главное — была ослаблена обороноспособность Руси, чем вскоре воспользовались монгольские завоеватели.

Монголо-татарское нашествие

К концу XII — началу XIII века монгольское государство занимало обширную территорию от Байкала и Амура на востоке до верховий Иртыша и Енисея на западе, от Великой китайской стены на юге до границ южной Сибири на севере. Основным занятием монголов было кочевое скотоводство, поэтому главным источником обогащения служили постоянные набеги для захвата добычи и рабов, пастбищных территорий.

Войско монголов представляло собой мощную организацию, состоящую из пеших дружин и конных воинов, являвшихся главной наступательной силой. Все подразделения были скованы жестокой дисциплиной, хорошо была налажена разведка. В распоряжении монголов была осадная техника. В начале XIII века монгольские орды завоевывают и разоряют крупнейшие среднеазиатские города — Бухару, Самарканд, Ургенч, Мерв. Пройдя через Закавказье, превращенное ими в развалины, монгольские войска выходят в степи северного Кавказа, и, разбив половецкие племена, орды монголо-татар во главе с Чингисханом продвинулись по причерноморским степям в направлении Руси.

Против них выступило объединенное войско русских князей, которым командовал киевский князь Мстислав Романович. Решение об этом было принято на княжеском съезде в Киеве, после того, как половецкие ханы обратились к русским за помощью. Сражение произошло в мае 1223 г. на реке Калке. Половцы почти с самого начала боя бросились в бегство. Русские же войска оказались лицом к лицу с пока еще незнакомым противником. Они не знали ни организации монгольского войска, ни приемов ведения боя. В русских полках отсутствовало единство и согласованность действий. Одна часть князей повела свои дружины в бой, другая предпочла ожидать. Следствием такого поведения стало жестокое поражение русских войск.

Дойдя после битвы при Калке до Днепра, монгольские орды не пошли на север, а, повернув на восток, вернулись обратно в монгольские степи. После смерти Чингисхана его внук Батый зимой 1237 г. двинул войско теперь уже против

Руси. Лишенное помощи со стороны других русских земель Рязанское княжество стало первой жертвой захватчиков. Опустошив Рязанскую землю, войска Батыя двинулись на Владимиро-Суздальское княжество. Монголы разорили и сожгли Коломну и Москву. В феврале 1238 г. они подошли к столице княжества — городу Владимиру — и взяли его после ожесточенного штурма.

Разорив Владимирскую землю, монголы двинулись на Новгород. Но из-за весенней распутицы они вынуждены были повернуть в сторону приволжских степей. Лишь в следующем году Батый вновь двинул войска на завоевание южной Руси. Овладев Киевом, они прошли через Галицко-Волынское княжество в Польшу, Венгрию и Чехию. После этого монголы вернулись в приволжские степи, где образовали государство Золотая Орда. В результате этих походов монголы завоевали все русские земли, за исключением Новгорода. Над Русью нависло татарское иго, продолжавшееся до конца XIV века.

Иго монголо-татар заключалось в использовании экономического потенциала Руси в интересах завоевателей. Ежегодно Русь выплачивала огромную дань, причем Золотая Орда жестко контролировала деятельность русских князей. В культурной области монголы использовали труд русских мастеров для строительства и украшения золотоордынских городов. Завоеватели расхищали материальные и художественные ценности русских городов, истощая жизненные силы населения многочисленными набегами.

Вторжение крестоносцев. Александр Невский

Русь, ослабленная монголо-татарским игом, оказалась в очень тяжелом положении, когда над ее северо-западными землями нависла угроза со стороны шведских и немецких феодалов. После захвата прибалтийских земель рыцари Ливонского ордена приблизились к границам Новгородско-Псковской земли. В 1240 г. состоялась Невская битва — сражение между русскими и шведскими войсками на реке Неве. Новгородский князь Александр Ярославович наголову разбил противника, за что и получил прозвище Невский.

Александр Невский возглавил объединенное русское войско, с которым выступил весной 1242 г. для освобождения Пскова, захваченного к тому времени немецкими рыцарями. Преследуя их войско, русские дружины вышли к Чудскому озеру, где 5 апреля 1242 г. произошла знаменитая битва, получившая название Ледового побоища. В результате ожесточенной битвы не-мецкие рыцари были наголову разбиты.

Значение побед Александра Невского с агрессией крестоносцев трудно переоценить. В случае успеха крестоносцев могла бы произойти насильственная ассимиляция народов Руси во многих областях их жизни и культуры. Этого не могло случиться за почти три столетия ордынского ига, так как общая культура степняков-кочевников была намного ниже, чем культура немцев и шведов. Поэтому монголо-татары так и не смогли навязать русскому народу свою культуру и образ жизни.

Возвышение Москвы

Родоначальником московской княжеской династии и первым самостоятельным московским удельным князем стал младший сын Александра Невского Даниил. В то время Москва являлась небольшим и небогатым уделом. Однако Даниил Александрович сумел значительно расширить его границы. Для того чтобы получить контроль над всей рекой Москвой, в 1301 г. он отнял у рязанского князя Коломну. В 1302 г. к Москве был присоединен Переяславский удел, на следующий год — Можайск, входивший в состав Смоленского княжества.

Рост и возвышение Москвы были связаны прежде всего с ее расположением в центре той части славянских земель, где складывалась русская народность. Экономическому развитию Москвы и Московского княжества способствовало их местонахождение на перекрестке как водных, так и сухопутных торговых путей. Торговые пошлины, которые платили московским князьям проезжие купцы, являлись важным источником роста княжеской казны. Не менее важно было и то, что город находился в центре

русских княжеств, которые прикрывали его от набегов захватчиков. Московское княжество стало своего рода убежищем для многих русских людей, что также способствовало развитию хозяйства и быстрому росту населения.

В XIV веке Москва выдвигается как центр Московского великого княжества — одного из сильнейших в Северо-восточной Руси. Умелая политика московских князей способствовала возвышению Москвы. Со времени Ивана I Даниловича Калиты Москва становится политическим центром Владимиро-Суздальского великого княжества, резиденцией русских митрополитов, церковной столицей Руси. Борьба между Москвой и Тверью за главенство на Руси завершается победой московского князя.

Во второй половине XIV века при внуке Ивана Калиты Дмитрии Ивановиче Донском Москва стала организатором вооруженной борьбы русского народа против монголо-татарского ига, свержение которого началось с Куликовской битвы 1380 г., когда Дмитрий Иванович разбил стотысячное войско хана Мамая на Куликовом поле. Золотоордынские ханы, понимая значение Москвы, не раз пытались ее уничтожить (сожжение Москвы ханом Тохтамышем в 1382 г.). Однако ничто уже не могло остановить консолидацию русских земель вокруг Москвы. В последней четверти XV века при великом князе Иване III Васильевиче Москва превращается в столицу Русского централизованного государства, в 1480 г. навсегда сбросившего монголо-татарское иго (стояние на реке Угре).

Правление Ивана IV Грозного

После смерти Василия III в 1533 г. на престол вступил его трехлетний сын Иван IV. Из-за его малолетства правительницей была объявлена Елена Глинская, его мать. Так начинается период печально знаменитого «боярского правления» — время боярских заговоров, дворянских волнений, городских восстаний. Участие Ивана IV в государственной деятельности начинается с создания Избранной Рады — особого совета при молодом царе, в составе которого были лидеры дворянства, представители крупнейшей знати. Состав Избранной Рады как бы отразил компромисс между различными слоями господству-ющего класса.

Несмотря на это, обострение взаимоотношений Ивана IV с определенными кругами боярства стало назревать еще в середине 50-х годов XVI века. Особенно острый протест вызвал курс Ивана IV «открыть большую войну» за Ливонию. Некоторые члены правительства считали войну за Прибалтику преждевременной и требовали направить все силы на освоение южных и восточных рубежей России. Раскол между Иваном IV и большинством членов Избранной Рады толкнул бояр на выступление против нового политического курса. Это подтолкнуло царя перейти к более решительным мерам — полной ликвидации боярской оппозиции и созданию особых карательных органов власти. Новый порядок управления государством, введенный Иваном IV в конце 1564 г., получил название опричнины.

Страна была разделена на две части: опричнину и земщину. В опричнину царь включил наиболее важные земли — экономически развитые районы страны, важные в стратегическом отношении пункты. На этих землях поселились дворяне, входившие в опричное войско. Содержать его входило в обязанность земщины. Бояр с опричных территорий выселяли.

В опричнине создавалась параллельная система управления государством. Ее главой стал сам Иван IV. Опричнина была создана для устранения тех, кто выражал недовольство самодержавием. Это была не только административная и земельная реформа. Стремясь уничтожить остатки феодального дробления в России, Иван Грозный не останавливался ни перед какими жестокостями. Начался опричный террор, казни и ссылки. Особенно жестокому разгрому подверглись центр и северо-запад русской земли, где боярство было особенно сильным. В 1570 г. Иван IV предпринял поход на Новгород. По дороге опричное войско разгромило Клин, Торжок и Тверь.

Опричнина не уничтожила княжеско-боярского землевладения. Однако она сильно ослабила его мощь. Была подорвана политическая роль боярской аристократии, выступавшей против

политики централизации. В то же время опричнина ухудшила положение крестьян и способствовала их массовому закрепощению.

В 1572 г., вскоре после похода на Новгород, опричнина была отменена. Причиной этого было не только то, что основные силы оппозиционного боярства были к этому времени сломлены и само оно было физически истреблено почти полностью. Основная причина отмены опричнины заключается в явно назревшем недовольстве этой политикой самых различных слоев населения. Но, отменив опричнину и даже вернув некоторым боярам их старые вотчины, Иван Грозный не изменил общего направления своей политики. Многие опричные учреждения продолжали существовать после 1572 г. под названием Государева двора.

Опричнина могла дать лишь временный успех, так как она представляла собой попытку грубой силой сломить то, что было порождено экономическими законами развития страны. Необходимость борьбы с удельной стариной, укрепление централизации и власти царя были объективно необходимы в то время для России. Правление Ивана IV Грозного предопределило дальнейшие события — установление крепостного права в государственном масштабе и так называемое «смутное время» на рубеже XVI-XVII веков.

«Смутное время»

После Ивана Грозного русским царем в 1584 г. стал его сын Федор Иванович, последний царь из династии Рюриковичей. Его правление стало началом того периода в отечественной истории, который принято обозначать как «смутное время». Федор Иванович был слабым и болезненным человеком, неспособным управлять огромным Российским государством. Среди его приближенных постепенно выделяется Борис Годунов, который после смерти Федора в 1598 г. был избран Земским собором на царство. Сторонник жесткой власти, новый царь продолжил активную политику закрепощения крестьянства. Был издан указ о кабальных холопах, тогда же увидел свет указ об установлении «урочных лет», то есть срок, в течение которого владельцы крестьян могли бы возбудить иск о возвращении им беглых крепостных. В правление Бориса Годунова была продолжена раздача земель служилым людям за счет владений, отобранных в казну у монастырей и опальных бояр.

В 1601-1602 гг. Россию постигли сильные неурожаи. Ухудшению положения населения способствовала эпидемия холеры, поразившая центральные районы страны. Бедствия и недовольство народа привели к многочисленным восстаниям, наиболее крупным из которых было восстание Хлопка, с трудом подавленное властями лишь осенью 1603 г.

Воспользовавшись сложностями внутреннего положения русского государства, польские и шведские феодалы попытались захватить смоленские и северские земли, которые раньше входили в состав Великого княжества Литовского. Часть русского боярства была недовольна правлением Бориса Годунова, а это было питательной средой для появления оппозиции.

В условиях всеобщего недовольства на западных границах России появляется самозванец, выдававший себя за «чудесно спасшегося» в Угличе царевича Дмитрия, сына Ивана Грозного. «Царевич Дмитрий» обратился за помощью к польским магнатам, а затем и к королю Сигизмунду. Чтобы заручиться поддержкой католической церкви, он тайно принял католичество и обещал подчинить русскую церковь папскому престолу. Осенью 1604 г. Лжедмитрий с небольшим войском перешел русскую границу и двинулся через Северскую Украину на Москву. Несмотря на поражение под Добрыничами в начале 1605 г., ему удалось поднять на восстание многие области страны. Весть о появлении «законного царя Дмитрия» вызывала большие надежды на перемены в жизни, поэтому город за городом заявлял о поддержке самозванца. Не встречая сопротивления на своем пути, Лжедмитрий подошел к Москве, где к тому времени скоропостижно скончался Борис Годунов. Московское бо-ярство, не принявшее в качестве царя сына Бориса Годунова, дало возможность самозванцу утвердиться на российском престоле.

Однако он не торопился выполнить данные им ранее обещания — передать Польше окраинные русские области и тем более обратить русский народ в католичество. Лжедмитрий не оправдал

надежд и крестьянства, поскольку стал проводить ту же политику, что и Годунов, опираясь на дворянство. Бояре, использовавшие Лжедмитрия для свержения Годунова, теперь ждали только повода, чтобы избавиться от него и прийти к власти. Поводом для свержения Лжедмитрия послужила свадьба самозванца с дочерью польского магната Мариной Мнишек. Прибывшие на торжества поляки вели себя в Москве как в завоеванном городе. Воспользовавшись сложившейся обстановкой, бояре во главе с Василием Шуйским 17 мая 1606 г. подняли восстание против самозванца и его польских сторонников. Лжедмитрий был убит, а поляки изгнаны из Москвы.

После убийства Лжедмитрия русский престол занял Василий Шуйский. Его правительству пришлось бороться с крестьянским движением начала XVII века ( восстание под руководством Ивана Болотникова), с польской интервенцией, новый этап которой начался в августе 1607 г. (Лжедмитрий II). После поражения под Волховом правительство Василия Шуйского было осаждено в Москве польско-литовскими интервентами. В конце 1608 г. многие районы страны оказались под властью Лжедмитрия II, чему способствовал новый всплеск классовой борьбы, а также рост противоречий среди русских феодалов. В феврале 1609 г. правительство Шуйского заключило договор со Швецией, по которому за наем шведских войск уступало ей часть русской тер-ритории на севере страны.

С конца 1608 г. началось стихийное народно-освободительное движение, возглавить которое правительство Шуйского сумело только с конца зимы 1609 г. К концу 1610 г. были освобождены Москва и большая часть страны. Но еще в сентябре 1609 г. началась открытая польская интервенция. Поражение войск Шуйского под Клушино от армии Сигизмунда III в июне 1610 г., выступление городских низов против правительства Василия Шуйского в Москве привели к его падению. 17 июля частью боярства, столичного и провинциального дворянства Василий Шуйский был свергнут с престола и насильственно пострижен в монахи. В сентябре 1610 г. он был выдан полякам и увезен в Польшу, где и умер в заключении.

После свержения Василия Шуйского власть оказалась в руках 7 бояр. Это правительство получило название «семибоярщины». Одним из первых решений «семибоярщины» было постановление не избирать царем представителей русских родов. В августе 1610 г. эта группировка заключила со стоящими под Москвой поляками договор, признававший русским царем сына польского короля Сигизмунда III — Владислава. В ночь на 21 сентября польские войска были тайно впущены в Москву.

Агрессивные действия развернула и Швеция. Свержение Василия Шуйского освободило ее от союзнических обязательств по договору 1609 г. Шведские войска оккупировали значительную часть севера России и захватили Новгород. Страна оказалась перед прямой угрозой утраты суверенитета.

В России росло недовольство. Появилась идея создания всенародного ополчения для освобождения Москвы от интервентов. Его возглавил воевода Прокопий Ляпунов. В феврале-марте 1611 г. войска ополченцев осадили Москву. Решающее сражение произошло 19 марта. Однако освободить город пока не удалось. Поляки по-прежнему оставались в Кремле и Китай-городе.

Осенью того же года по призыву нижегородца Кузьмы Минина стало создаваться второе ополчение, руководителем которого был избран князь Дмитрий Пожарский. Первоначально ополчение наступало по восточным и северо-восточным районам страны, где не только образовывались новые районы, но и создавались правительства и администрация. Это помогло войску заручиться поддержкой людьми, финансами и припасами всёх важнейших городов страны.

В августе 1612 г. ополчение Минина и Пожарского вошло в Москву и объединилось с остатками первого ополчения. Польский гарнизон испытывал огромные лишения и голод. После удачного штурма Китай-города 26 октября 1612 г. поляки капитулировали и сдали Кремль. Москва была освобождена от интервентов. Попытка польских войск вновь взять Москву провалилась, и Сигиз-мунд III потерпел поражение под Волоколамском.

В январе 1613 г. собравшийся в Москве Земский собор принял решение об избрании на российский престол 16-летнего Михаила Романова, сына митрополита Филарета, находившегося в это время в польском плену.

В 1618 г. поляки вновь вторглись в Россию, но были разгромлены. Польская авантюра закончилась перемирием в деревне Деулино в том же году. Однако Россия потеряла Смоленск и северские города, которые смогла вернуть только в середине XVII века. На родину вернулись русские пленные, в том числе и Филарет, отец нового русского царя. В Москве он был возведен в патриарший сан и сыграл в истории значительную роль как фактический правитель России.

В жесточайшей и суровой борьбе Россия отстояла свою независимость и вступила в новый этап своего развития. Фактически на этом кончается ее средневековая история.

Россия после смуты

Россия отстояла свою независимость, но понесла серьезные территориальные потери. Следствием интервенции и крестьянской войны под предводительством И.Болотникова (1606-1607 гг.) явилась жестокая хозяйственная разруха. Современники называли ее «великим московским разорением». Почти половина пахотных земель была заброшена. Покончив с интервенцией, Россия начинает медленно и с огромными трудностями восстанавливать свое хозяйство. Это и стало основным содержанием царствования двух первых царей из династии Романовых — Михаила Федоровича (1613-1645 гг.) и Алексея Михайловича (1645-1676 гг.).

Для улучшения работы органов государственного управления и создания более справедливой системы налогообложения по указу Михаила Романова была проведена перепись населения, составлены земельные описи. В первые годы его царствования усиливается роль Земского собора, который сделался своего рода постоянно действующим национальным советом при царе и придавал Русскому государству внешнее сходство с парламентской монархией.

Шведы, хозяйничавшие на севере, потерпели неудачу под Псковом и в 1617 г. заключили Столбовский мир, по которому России был возвращен Новгород. При этом, однако, Россия утратила все побережье Финского залива и выход в Балтийское море. Положение изменилось только через почти сто лет, в начале XVIII века, уже при Петре I.

В правление Михаила Романова также велось интенсивное строительство «засечных черт» против крымских татар, происходила дальнейшая колонизация Сибири.

После смерти Михаила Романова на престол вступил его сын Алексей. Со времени его правления фактически начинается установление самодержавной власти. Прекратилась деятельность Земских соборов, уменьшилась роль Боярской думы. В 1654 г. был создан Приказ тайных дел, который подчинялся непосредственно царю и осуществлял контроль над государственным управлением.

Время правления Алексея Михайловича отмечено целым рядом народных выступлений — городских восстаний, т.н. «медный бунт», крестьянская война под предводительством Степана Разина. В ряде городов России (Москва, Воронеж, Курск и др.) в 1648 г. вспыхнули восстания. Восстание в Москве в июне 1648 г. получило название «соляного бунта». Оно было вызвано недовольством населения грабительской политикой правительства, которое с целью пополнения государственной казны заменило различные прямые налоги единым налогом — на соль, что вызвало ее подорожание в несколько раз. В восстании участвовали горожане, крестьяне и стрельцы. Восставшие подожгли Белый город, Китай-город, разгромили дворы наиболее ненавистных бояр, дьяков, купцов. Царь был вынужден пойти на временные уступки восставшим, а затем, внеся раскол в ряды восставших,

казнил многих руководителей и активных участников восстания.

В 1650 г. восстания произошли в Новгороде и Пскове. Они были вызваны закрепощением посадских людей Соборным уложением 1649 г. Восстание в Новгороде было быстро подавлено властями. В Пскове это не удалось, и правительству пришлось пойти на переговоры и некоторые уступки.

25 июня 1662 г. Москву потрясло новое крупное восстание — «медный бунт». Его причинами стало расстройство хозяйственной жизни государства в годы войн России с Польшей и Швецией, резкое увеличение налогов и усиление фе-одально-крепостнической эксплуатации. Выпуск большого количества медных денег, приравненных по стоимости к серебряным, привел к их обесцениванию, массовому изготовлению фальшивых медных денег. В восстании приняло участие до 10 тыс. человек, главным образом жителей столицы. Восставшие направились в село Коломенское, где находился царь, и потребовали выдачи изменников-бояр. Войска жестоко подавили это выступление, однако правительство, напуганное восстанием, в 1663 г. отменило медные деньги.

Усиление крепостного гнета и общее ухудшение жизни народа стали основными причинами крестьянской войны под руководством Степана Разина (1667-1671 гг.). В восстании приняли участие крестьяне, городская беднота, беднейшее казачество. Движение началось с разбойного похода казаков на Персию. На обратном пути разницы подошли к Астрахани. Местные власти решили их пропустить через город, за что получили часть оружия и добычи. Затем отряды Разина заняли Царицын, после чего отправились на Дон.

С весны 1670 г. начался второй период восстания, основным содержанием которого было выступление против бояр, дворян, купцов. Восставшие вновь овладели Царицыном, затем и Астраханью. Самара и Саратов сдались без боя. В начале сентября отряды Разина подошли к Симбирску. К тому времени к ним примкнули народы Поволжья — татары, мордва. Движение вскоре охватило и Украину. Взять Симбирск Разину не удалось. Раненный в бою, с небольшим отрядом Разин отступил на Дон. Там он был схвачен зажиточными казаками и отправлен в Москву, где был казнен.

Неспокойное время правления Алексея Михайловича было отмечено еще одним важным событием — расколом православной церкви. В 1654 г. по инициативе патриарха Никона в Москве собрался церковный собор, на котором было решено сравнить церковные книги с их греческими оригиналами и установить единый и обязательный для всех порядок совершения обрядов.

Многие священники во главе с протопопом Аввакумом выступили против постановления собора и объявили о своем отходе от православной церкви, возглавляемой Никоном. Их стали называть раскольниками или старообрядцами. Возникшая в церковных кругах оппозиция реформе стала своеобразной формой социального протеста.

Осуществляя реформу, Никон ставил теократические цели — создать сильную церковную власть, стоящую над государством. Однако вмешательство патриарха в дела государственного управления вызвало разрыв с царем, результатом которого стало низложение Никона и превращение церкви в часть государственного аппарата. Это стало еще одним шагом к установлению самодержавия.

Воссоединение Украины с Россией

В правление Алексея Михайловича в 1654 г. произошло воссоединение Украины с Россией. В XVII веке украинские земли находились под властью Польши. На них стало насильственно вводиться католичество, появились польские магнаты и шляхта, которые жестоко угнетали украинский народ, что вызвало подъем национально-освободительного движения. Его центром стала Запорожская Сечь, где формировалось вольное казачество. Во главе этого движения стал Богдан Хмельницкий.

В 1648 г. его войска нанесли поражение полякам под Желтыми Водами, Корсунем и Пилявцами. После поражения поляков восстание распространилось на всю Украину и часть Белоруссии. Одновременно Хмельницкий обратился

к России с просьбой принять Украину в состав Российского государства. Он понимал, что только в союзе с Россией можно было избавиться от опасности полного порабощения Украины Польшей и Турцией. Однако в это время правительство Алексея Михайловича удовлетворить его просьбу не могло, так как Россия не была готова к войне. Тем не менее, несмотря на все трудности своего внутриполитического положения, Россия продолжала оказывать Украине дипломатическую, экономическую и военную поддержку.

В апреле 1653 г. Хмельницкий вновь обратился к России с просьбой принять Украину в ее состав. 10 мая 1653 г. Земский собор в Москве решил удовлетворить эту просьбу. 8 января 1654 г. Большая рада в городе Переяславле провозгласила вхождение Украины в состав России. В связи с этим началась война между Польшей и Россией, завершившаяся подписанием в конце 1667 г. Андрусовского перемирия. Россия получила Смоленск, Дорогобуж, Белую Церковь, Северскую землю с Черниговом и Стародубом. Правобережная Украина и Белоруссия по-прежнему оставались в составе Польши. Запорожская Сечь, согласно договору, была под совместным управлением России и Польши. Эти условия были окончательно закреплены в 1686 г. «Вечным миром» России и Польши.

Правление царя Федора Алексеевича и регентство Софьи

В XVII веке становится очевидным заметное отставание России от передовых западных стран. Отсутствие выходов к незамерзающим морям мешало торговле и культурным связям с Европой. Необходимость в регулярной армии диктовалась сложностью внешнеполитического положения России. Стрелецкое войско и дворянское ополчение уже не могли в полной мере обеспечить ее обороноспособность. Не было крупной мануфактурной промышленности, устарела система управления, основанная на приказах. России требовались реформы.

В 1676 г. царский престол перешел к слабому и болезненному Федору Алексеевичу, от которого нельзя было ожидать радикальных преобразований, столь необходимых для страны. И все-таки в 1682 г. ему удалось отменить местничество — систему распределения чинов и должностей по знатности и родовитости, существовавшую еще с XIV века. В области внешней политики России удалось одержать победу в войне с Турцией, которая была вынуждена признать воссоединение Левобережной Украины с Россией.

В 1682 г. Федор Алексеевич скоропостижно скончался, и, поскольку он был бездетен, в России вновь разразился династический кризис, так как на престол могли претендовать два сына Алексея Михайловича — шестнадцатилетний болезненный и слабый Иван и десятилетний Петр. От притязаний на престол не отказывалась и царевна Софья. В результате стрелецкого восстания 1682 г. царями были объявлены оба наследника, а их регентшей — Софья.

В годы ее правления были сделаны небольшие уступки посадскому населению и ослаблен сыск беглых крестьян. В 1689 г. произошел разрыв между Софьей и боярско-дворянской группировкой, поддерживавшей Петра I. Потерпев поражение в этой борьбе, Софья была заточена в Новодевичьем монастыре.

Петр I. Его внутренняя и внешняя политика

В первый период правления Петра I произошли три события, решительно повлиявшие на становление царя-реформатора. Первым из них была поездка молодого царя в Архангельск в 1693-1694 гг., где море и корабли покорили его навсегда. Вторым — Азовские походы против турок с целью поиска выхода к Черному морю. Взятие турецкой крепости Азова стало первой победой русских войск и созданного в России флота, началом превращения страны в морскую державу. С другой стороны, эти походы показали необходимость перемен в русской армии. Третьим событием явилась поездка русской дипло-матической миссии в Европу, в которой участвовал сам царь. Посольство не достигло прямой цели (России пришлось отказаться от борьбы с Турцией), но оно изучило международную обстановку, подготовило почву для борьбы за Прибалтику и за выход в Балтийское море.

В 1700 г. началась тяжелая Северная война со шведами, которая растянулась на 21 год. Эта война во многом обусловила темпы и характер проводимых в России преобразований. Северная война велась за возвращение захваченных шведами земель и за выход России в Балтийское море. В первый период войны (1700-1706 гг.) после поражения русских войск под Нарвой Петр I смог не только собрать новую армию, но и перестроить на военный лад промышленность страны. Овладев ключевыми пунктами в Прибалтике и основав в 1703 г. город Петербург, русские войска закрепились на побережье Финского залива.

Во второй период войны (1707-1709 гг.) шведы через Украину вторглись в пределы России, но, потерпев поражение у деревни Лесной, были окончательно разгромлены в Полтавском сражении в 1709 г. Третий период войны приходится на 1710-1718 гг., когда русские войска овладели многими городами Прибалтики, вытеснили шведов из Финляндии, совместно с поля-ками оттеснили противника в Померанию. Русский флот одержал блестящую победу при Гангуте в 1714 г.

В ходе четвертого периода Северной войны, несмотря на происки Англии, заключившей мир со Швецией, Россия утвердилась на берегах Балтийского моря. Северная война завершилась в 1721 г. подписанием Ништадтского мира. Швеция признавала присоединение к России Лифляндии, Эстляндии, Ижорской земли, части Карелии и ряда островов Балтийского моря. Россия обязалась уплатить Швеции денежную компенсацию за отходящие к ней территории и возвратить Финляндию. Русское государство, вернув себе ранее захваченные Швецией земли, закрепило за собой выход в Балтийское море.

На фоне бурных событий первой четверти XVIII века происходила перестройка всех отраслей жизни страны, а также осуществлялись реформы системы государственного управления и политической системы — власть царя приобретала неограниченный, абсолютный характер. В 1721 г. царь принял титул императора Всероссийского. Таким образом, Россия становилась империей, а ее правитель — императором огромного и могучего государства, ставшего в один ряд с великими мировыми державами того времени.

Создание новых властных структур началось с изменения образа самого монарха и основ его власти и авторитета. В 1702 г. на смену Боярской думе пришла «Консилия министров», а с 1711 г. верховным учреждением в стране стал Сенат. Создание этого органа власти породило и сложную бюрократическую структуру с канцеляриями, отделами и многочисленными штатами сотрудников. Именно со времен Петра I в России сформировался своеобразный культ бюрократических учреждений и административных инстанций.

В 1717-1718 гг. вместо примитивной и давно уже изжившей себя системы приказов были созданы коллегии — прообраз будущих министерств, а в 1721 г. учреждение Синода во главе со светским чиновником полностью поставило церковь в зависимость и на службу государству. Тем самым отныне институт патриаршества в России был отменен.

Венцом оформления бюрократической структуры абсолютистского государства стала «Табель о рангах», принятая в 1722 г. Согласно ей военные, гражданские и придворные звания были разбиты на четырнадцать рангов — ступеней. Общество не просто упорядочивалось, но и оказывалось под контролем императора и высшей аристократии. Улучшилось функционирование государственных учреждений, каждое из которых получило определенное направление деятельности.

Испытывая острую потребность в деньгах, правительство Петра I ввело подушную подать, заменившую подворное налогообложение. В связи с этим для учета мужского населения в стране, ставшего новым объектом налогообложения, была проведена его перепись — т.н. ревизия. В 1723 г. увидел свет указ о престолонаследии, по которому монарх сам получил право назначать своих преемников, невзирая на родственные связи и первородство.

В период правления Петра I возникло большое количество мануфактур и горных предприятий, было положено начало освоению новых железнорудных месторождений. Содействуя развитию промышленности, Петр I учредил центральные органы, ведавшие торговлей и промышленностью, передавал казенные предприятия в частные руки.

Покровительственный тариф 1724 г. ограждал новые отрасли промышленности от иностранной конкуренции и поощрял ввоз в страну сырья и продуктов, производство которых не обеспечивало потребностей внутреннего рынка, в чем проявилась политика меркантилизма.

Итоги деятельности Петра I

Благодаря энергичной деятельности Петра I в экономике, уровне и формах развития производительных сил, в политическом строе России, в структуре и функциях органов власти, в организации армии, в классовой и сословной структуре населения, в быту и культуре народов произошли огромные изменения. Средневековая московская Русь превратилась в Российскую империю. Коренным образом изменилось место России и ее роль в международных делах.

Сложность и противоречивость развития России в этот период определили и противоречивость деятельности Петра I в осуществлении реформ. С одной стороны, эти реформы имели огромный исторический смысл, так как шли навстречу общенациональным интересам и потребностям страны, способствовали ее прогрессивному развитию, будучи нацелены на ликвидацию ее отсталости. С другой стороны — реформы осуществлялись теми же крепостническими методами и способствовали тем самым укреплению господства крепостников.

Прогрессивные преобразования петровского времени с самого начала несли в себе консервативные черты, которые в ходе развития страны выступали все сильнее и не могли обеспечить ликвидацию ее отсталости в полной мере. Объективно эти реформы носили буржуазный характер, субъективно же — их реализация привела к усилению крепостничества, укреплению феодализма. Другими они быть не могли — капиталистический уклад в России этого времени был еще очень слаб.

Следует отметить и те культурные перемены в российском обществе, которые произошли в петровские времена: возникновение школ первой ступени, училищ по специальностям, Российской Академии наук. В стране возникла сеть типографий для печатания отечественных и переводных изданий. Начала выходить первая в стране газета, возник первый музей. Значительные изменения произошли в быту.

Дворцовые перевороты XVIII века

После смерти императора Петра I в России начался период, когда верховная власть достаточно быстро переходила из рук в руки, причем занимавшие престол не всегда имели на то законные права. Началось это сразу после кончины Петра I в 1725 г. Новая аристократия, сформировавшаяся в период правления императора-реформатора, опасаясь потерять свое благополучие и могущество, способствовала восхождению на престол Екатерины I, вдовы Петра. Это позволило учредить в 1726 г. Верховный Тайный Совет при императрице, который фактически захватил власть.

Наибольшую выгоду от этого извлек первый фаворит Петра I — светлейший князь А.Д.Меншиков. Его влияние было настолько велико, что даже после кончины Екатерины I он смог подчинить себе нового российского императора — Петра II. Однако другая группировка придворных, недовольная действиями Меншикова, лишила его власти, и вскоре он был сослан в Сибирь.

Эти политические перемены не изменили сложившегося порядка. После неожиданной смерти Петра II в 1730 г. наиболее влиятельная группировка приближенных покойного императора, т.н. «верховники», решила пригласить на престол племянницу Петра I — курляндскую герцогиню Анну Ивановну, оговорив ее воцарение условиями («Кондициями»): не выходить замуж, не назначать преемника, не объявлять войну, не вводить новые налоги и др. Принятие таких условий делало Анну послушной игрушкой в руках высшей аристократии. Однако по требованию дворянской депутации при вступлении на престол Анна Ивановна отвергла условия «верховников».

Опасаясь козней со стороны аристократии, Анна Ивановна окружила себя иностранцами, от которых полностью стала зависеть. Государственными делами императрица почти не интересовалась. Это подтолкнуло иностранцев из царского окружения к многим злоупотреблениям, расхищению казны и к оскорблению национального достоинства русского народа.

Незадолго до смерти Анна Ивановна своим наследником назначила внука своей старшей сестры младенца Ивана Антоновича. В 1740 году он в трехмесячном возрасте был провозглашен императором Иваном VI. Его регентом стал герцог курляндский Бирон, пользовавшийся огромным влиянием еще при Анне Ивановне. Это вызвало крайнее недовольство не только среди русского дворянства, но также и в ближайшем окружении покойной императрицы. В результате придворного заговора Бирон был свергнут, и права регентства были переданы матери императора Анне Леопольдовне. Таким образом, засилье иностранцев при дворе сохранилось.

Среди русских дворян и офицеров гвардии возник заговор в пользу дочери Петра I, в результате которого в 1741 г. на российский престол вступила Елизавета Петровна. В ее правление, которое длилось до 1761 г., произошло возвращение к петровским порядкам. Высшим органом государственной власти стал Сенат. Кабинет министров был упразднен, права российского дворянства значительно расширились. Все изменения в управлении государством были в первую очередь направлены на укрепление самодержавия. Однако, в отличие от петровских времен, главную роль в принятии решений стала играть придворно-бюрократическая верхушка. Императрица Елизавета Петровна также, как и ее предшественница, государственными делами интересовалась очень мало.

Своим наследником Елизавета Петровна назначила сына старшей дочери Петра I Карла-Петра-Ульриха, герцога Голштинского, который в православии принял имя Петра Федоровича. Он взошел на престол в 1761 г. под именем Петра III (1761-1762 гг.). Высшим органом власти стал Императорский совет, но новый император был совершенно не готов к управлению государством. Единственное крупное мероприятие, которое он осуществил, был «Манифест о даровании вольнос-ти и свободы всему российскому дворянству», уничтожавший обязательность для дворян как гражданской, так и военной службы.

Преклонение Петра III перед прусским королем Фридрихом II и осуществление политики, противоречившей интересам России, привело к недовольству его правлением и способствовало росту популярности его жены Софьи-Августы Фредерики, принцессы Анхальт-Цербстской, в православии Екатерины Алексеевны. Екатерина, в отличие от своего мужа, с уважением относилась к русским обычаям, традициям, православию, а главное — к русскому дворянству и армии. Заговор против Петра III в 1762 г. возвел Екатерину на императорский престол.

Правление Екатерины Великой

Екатерина II, правившая страной более тридцати лет, была образованной, умной, деловой, энергичной, честолюбивой женщиной. Находясь на престоле, она неоднократно заявляла, что является преемницей Петра I. Ей удалось сосредоточить в своих руках всю законодательную и большую часть исполнительной власти. Первой ее реформой стала реформа Сената, которая ограничила его функции в управлении государством. Она провела изъятие церковных земель, чем лишила церковь экономического могущества. Колоссальное количество монастырских крестьян были переданы государству, благодаря чему пополнилась казна России.

Правление Екатерины II оставило заметный след в российской истории. Как и во многих других государствах Европы, для России в период правления Екатерины II была характерна политика «просвещенного абсолютизма», которая предполагала правителя мудрого, покровительствовавшего искусству, благодетеля всей науки. Екатерина старалась соответствовать этому образцу и даже состояла в переписке с французскими просветителями, отдавая предпочтение Вольтеру и Дидро. Однако это не мешало ей проводить политику усиления крепостного гнета.

И все же проявлением политики «просвещенного абсолютизма» было создание и деятельность комиссии по составлению нового законодательного свода России вместо отжившего Соборного Уложения 1649 г. В работе этой комиссии были заняты представители различных слоев населения: дворяне, горожане, казачество и государственные крестьяне. В документах комиссии закреплялись сословные права и привилегии различных слоев населения России. Однако вскоре комиссия была распущена. Императрица выяснила умонастроения сословных групп и сделала ставку на дворянство. Цель была одна — укрепление государственной власти на местах.

С начала 80-х годов начался период реформ. Основными направлениями были следующие положения: децентрализация управления и повышение роли местного дворянства, увеличение числа губерний почти в два раза, жесткое соподчинение всех структур власти на местах и др. Реформировалась также и система правоохранительных органов. Политические функции пере-давались избираемому дворянским собранием земскому суду во главе с земским исправником, а в уездных городах — городничим. В уездах и губерниях возникла целая система судов, зависящая от администрации. Была введена и частичная избираемость чиновников в губерниях и уездах силами дворянства. Эти реформы создали достаточно совершенную систему местного управления и укрепили связь дворянства и самодержавия.

Положение дворянства еще более укрепилось после появления «Грамоты на права, вольности и преимущества благородного дворянства» , подписанной в 1785 г. В соответствии с этим документом дворяне освобождались от обязательной службы, телесных наказаний, а также могли лишиться своих прав и имущества только по приговору дворянского суда, утвержденному императрицей.