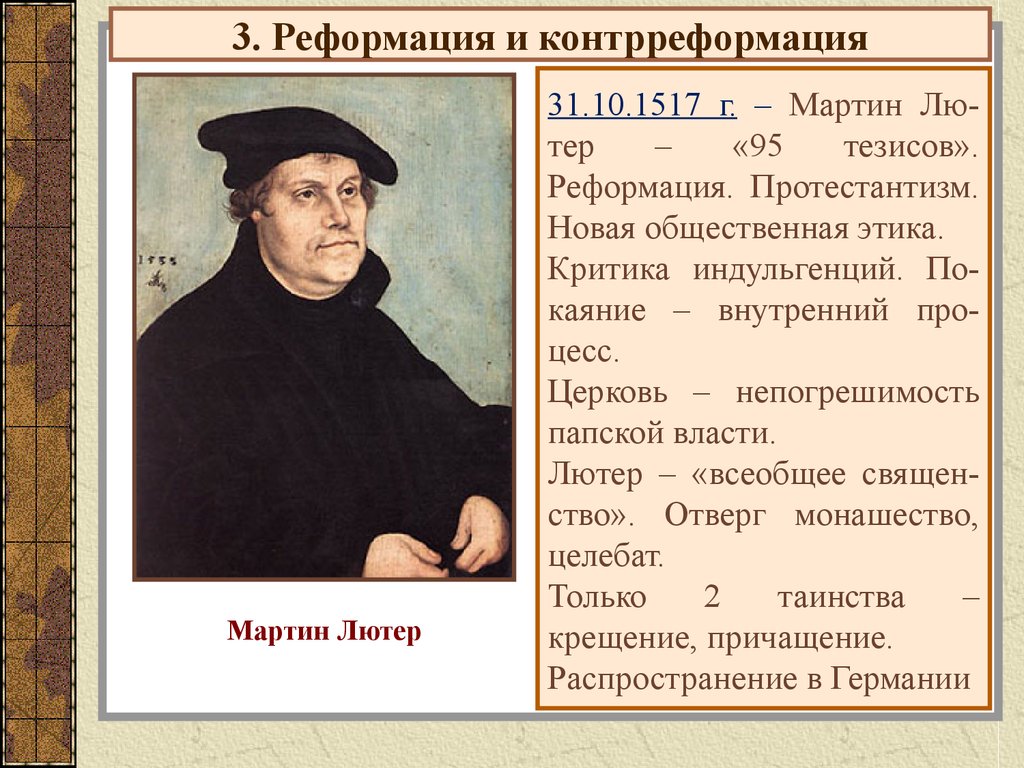

Мартин Лютер — биография

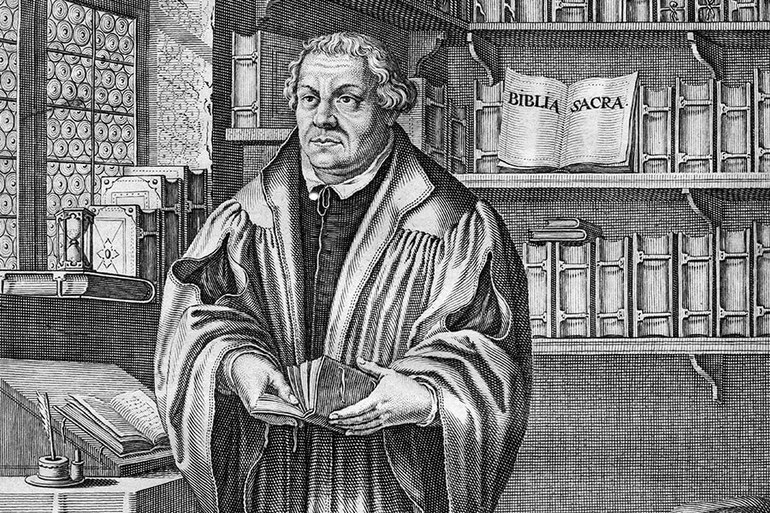

Мартин Лютер – богослов, инициировавший Реформацию. Перевел Библию на немецкий язык, его имя носит одно из религиозных направлений – лютеранство. Создал немецкий литературный язык.

Мартин Лютер оказал большое влияние на мировую историю, можно даже сказать, что он изменил вектор ее развития. Он заставил усомниться в мощи католической церкви, и стал создателем новой религии – протестантизма. Хотя всю жизнь не переставал причислять себя к грешникам.

Детство

Родился Мартин Лютер 10 ноября 1483 года в германском городке Айслебен, куда его отец, простой саксонский рудокоп Ганс Лютер переехал в поисках лучшей судьбы. Ганс был очень трудолюбивым, и, несмотря на это, материальное положение семьи оставалось достаточно трудным. Вначале семья жила в деревеньке Мера, отец вел обычный крестьянский образ жизни. После переезда в Айслебен он нашел работу в местных рудниках, где добывалась медь. Когда Мартину исполнилось полгода, семья снова переезжает. На этот раз они осели в Мансфельде, где Ганса уже считали зажиточным бюргером.

С первыми житейскими трудностями Мартин столкнулся в семилетнем возрасте, когда его отправили на учебу в обычную школу. Там он узнал, что такое постоянные наказания и унижения. Обучение в этом заведении было поставлено так, что талантливый ребенок за семь лет пребывания в его стенах, научился только письму, чтению, нескольким молитвам и десятку заповедей.

В 1497-м, когда Мартину исполнилось 14, он стал учеником францисканской школы Магдебурга, а через год начал посещать школу в Эйзенахе. У него абсолютно не было денег даже на самое необходимое. Вместе с друзьями он пытался заработать пением под окнами богатых горожан. Тогда он решает начать самостоятельно работать в руднике по примеру отца, но у судьбы были на него совсем другие планы.

Однажды они пели возле дома зажиточного горожанина, и Мартина заметила его жена Урсула. Женщине стало жаль этого мальчишку, она решила помочь ему, и предложила переехать в их дом на некоторое время. Этот переезд стал для Лютера дорогой в новую жизнь.

В 1501-м школа осталась позади, и Мартин становится студентом философского факультета Эрфуртского университета. Молодого человека отличала прекрасная память, он стремился к новым знаниям, буквально впитывал их во время лекций. Самый сложный материал давался ему легко, и благодаря этому Лютер занял в вузе лидирующие позиции.

В 1503 году Мартин получил степень бакалавра, и приглашение учить студентов философии. Одновременно с этим он изучает юриспруденцию, потому что такова была воля его отца. Развитие Лютера можно назвать разносторонним, однако больше всего его привлекало богословие, он интересовался трудами великих отцов церкви.

Мартин частенько посещал университетскую библиотеку, и в один из дней он взял в руки Библию. Молодой человек прочел ее полностью, а до этого он был знаком только с отрывками Писания. В те времена считалось, что миряне не должны читать ее полностью, это не обязательно и даже очень вредно. Эта книга перевернула внутренний мир впечатлительного Лютера.

После окончания университета Мартин совершил поступок, неожиданный для всех и в первую очередь для его родителей. Он решил отказаться от мирской жизни и посвятить себя служению Богу. Дело в том, что у него умер близкий друг, и Мартин почему-то решил, что он виновен в его смерти, что он грешен и нужно отмаливать у Господа прощение.

Монастырь

В монастыре Мартин брался за любую работу. В его обязанности входило заводить часы на башне, помогать старшим, подметать церковный двор, подменять привратника.

Чтобы помочь Лютеру победить человеческую гордыню, монахи изредка отправляли молодого богослова в город, просить милостыню. Он подчинялся безропотно, в точности соблюдая все их распоряжения. В 1506-м Мартин стал монахом, спустя год – священником. Теперь его звали брат Августин.

Пребывая в статусе священника, Лютер продолжал и дальше учиться и развиваться. В 1508-м он получил рекомендацию от генерального викария и стал преподавателем в Виттенбергском университете. Он преподавал студентам диалектику и физику. Прошло немного времени, Лютер удостоился степени библейского бакалавра, и имел право читать еще богословие. Лютеру позволялось заниматься толкованием библейских писаний, а для этого ему понадобилось знание иностранных языков. Упорный богослов принялся за их изучение.

В 1511-м Мартин побывал в Риме, куда был отправлен представителями священного ордена. Там он впервые открыл противоречивые факты в католицизме. В 1512 году Лютер занял место профессора теологии, выступал с проповедями, был смотрителем одиннадцати монастырей.

Могут быть знакомы

Реформации

Несмотря на то, что вся жизнь Мартина Лютера была посвящена служению Богу, он постоянно комплексовал, считал себя грешным и несовершенным в своих деяниях перед лицом Всевышнего. Душевные муки привели богослова к переосмыслению духовного мира и к началу реформаций.

В 1518-м Лютер раскритиковал вышедшую папскую буллу, он полностью разочаровался в католицизме. Мартин пишет свои 95 тезисов, разбивающие в прах учения Римской церкви.

Мартин утверждал, что духовенство не должно влиять на государство, равно как и выступать посредником между Богом и человеком. Лютер протестовал против безбрачия представителей духовенства, которое было принято декретами Папы. С подобными реформаторскими действиями церковь сталкивалась и раньше, но до Лютера никто так категорично и смело не высказывал свою позицию.

Тезисы смелого богослова достаточно быстро стали популярными, о новом учении узнал сам Папа Римский. В 1519 году он позвал Лютера к себе на суд. Мартин проявил упрямство и не поехал в Рим, после чего по указанию понтифика его предали анафеме – отлучили от святых таинств.

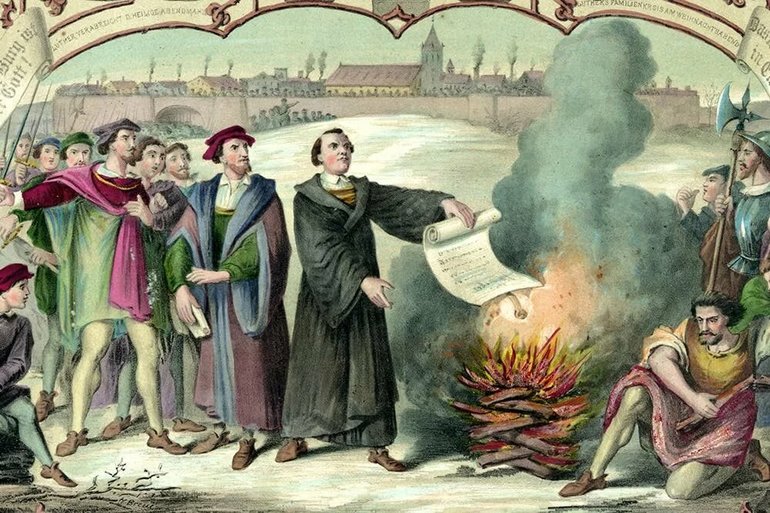

В 1520-м Лютер при народе сжег папскую буллу, призвал всех бороться с засильем папских законов, и лишился католического сана. На основании Вормсского эдикта от 26 мая 1521 года, Лютер обвинен в ереси. И только благодаря помощи сторонников лютеранства ему удалось спастись от расправы. Они инсценировали его похищение, а в действительности Мартин пребывал в замке Вартбург, где начал переводить Библию на немецкий.

В 1529-м общество официально приняло протестантизм Лютера, который стал одним из направлений католицизма. Но спустя некоторое время его приверженцы разделились на два лагеря – кальвинизм и лютеранство.

Кальвинизм получил свое название от имени Жана Кальвина, который продолжил реформаторское дело Лютера. Он считал, что судьба человека полностью предопределена Богом.

Отношение к евреям

На протяжении своей жизни Лютер несколько раз менял отношение к евреям. Вначале он осуждал тех, кто преследует людей этой национальности, призывал к терпимости и здравомыслии.

Мартин почему-то был уверен, что после посещения его проповедей, евреи согласятся пройти обряд крещения. Он написал памфлет под названием «О том, что Христос родился евреем», в котором отметил, что Христос тоже еврей, и что он поддерживает сопротивление древнего народа по отношению к папскому произволу.

Потом он понял, что евреи не реагируют на его учения, и его отношение к ним сменилось на враждебное. Под влиянием новых настроений, он пишет книги явно антиеврейского характера – «Застольные беседы», «О евреях и их лжи».

После этого еврейский народ полностью разочаровался в немецком философе, и не принял реформации, предложенные им. Позже в лютеранской церкви черпали свое вдохновение антисемиты, постулаты этой церкви послужили основой пропагандистской кампании против евреев, развернувшейся в Германии.

Личная жизнь

Мартин придерживался мнения, что Бог не запрещает никому жениться с целью продления своего рода. Биография богослова содержит сведения, что он устроил свою личную жизнь с бывшей монашкой, родившей ему шестерых детей.

Девушку завали Катарина фон Бора, в монастырь ее отдали родители, обнищавшие дворяне. В возрасте восьми лет она приняла обет безбрачия, строго соблюдала дисциплину, приняла аскезы. Воспитанная церковью, девушка отличалась строгостью и суровостью, и это впоследствии отразилось на ее отношениях с супругом.

Они обвенчались 13 июня 1525 года. Жениху на тот момент исполнилось 42, молодой жене 26. Молодожены поселились в заброшенном монастыре августинцев, жили они просто, без всяких излишеств и богатства. Двери их дома были открыты для всех, кому нужна была любая помощь.

Смерть

Мартин Лютер не переставал трудиться вплоть до самой смерти. Он выступал с лекциями, проповедями, трудился над созданием книг. Богослов отличался невероятной работоспособностью и энергичностью, он мало спал и скудно питался. С возрастом его начали мучить головокружения, частые обмороки без видимых причин. У Лютера обнаружили так называемую каменную болезнь, которая доставляла ему невероятные мучения.

Немалую роль в плохом самочувствии сыграли и внутренние сомнения и противоречия. Лютер рассказывал, что ночами видит Дьявола, который обращается к нему со странными вопросами. Богослов просил у Всевышнего послать ему смерть, так как болезненное состояние длилось долгие годы, доставляя ему невероятные мучения.

Он скончался внезапно 18 февраля 1546 года. Местом упокоения Лютера стала дворцовая церковь, на дверях которой он когда-то прибил свои тезисы.

Памяти Мартина Лютера посвящена автобиографическая картина режиссера Эрика Тилля «Лютер», в которой нашла отражение вся его жизнь.

Труды

- Берлебургская библия

- Лекции о Послании к Римлянам

- 95 тезисов об индульгенциях

- К христианскому дворянству немецкой нации

- О вавилонском пленении церкви

- О свободе христианина

- О рабстве воли

- О войне против турок

- Большой и малый Катехизис

- Похвала музыке

- О евреях и их лжи

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Мартин Лютер (1483-1546) был немецким священником, который наиболее известен тем, что играл ведущую роль в протестантской Реформации, религиозном и политическом движении XVI века в Европе, которое считается одним из самых влиятельных событий в истории западного христианства. Лютер прославился как лидер Реформации, подняв свой голос против индульгенций, практики в римском католицизме, в которой духовенство прощало грехи людей в обмен на деньги. Есть много интересных инцидентов в жизни Мартина Лютера, включая момент с его похищением, дабы обеспечить ему безопасность. Кроме того, есть поразительное сходство между Лютером и святым, в честь которого он был назван. А ещё было удивительное пророчество другого революционного монаха, предсказавшего успех Лютера в его стремлении реформировать христианство.

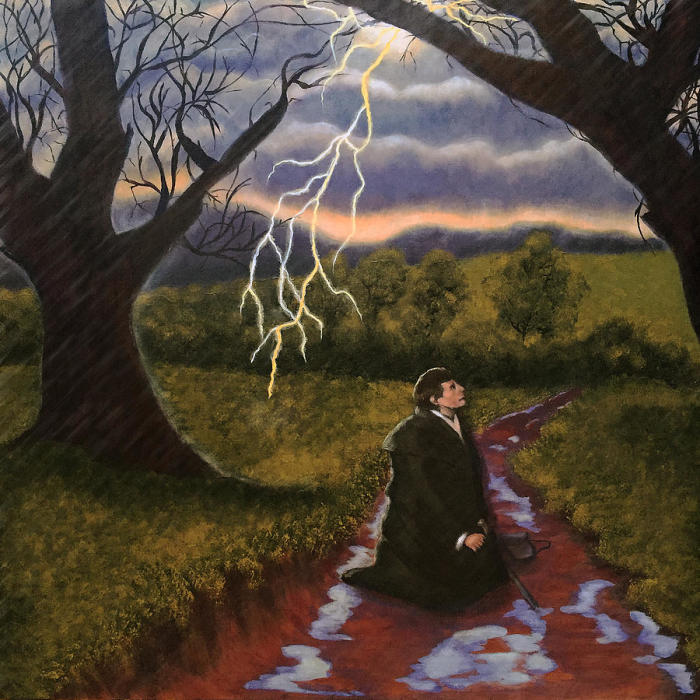

1. Гроза изменила его судьбу

Реформация Мартина Лютера «Буря» — это картина Тами Далтона, продемонстрированная 5 ноября 2015 года. Фото: fineartamerica.com.

В 1505 году Мартин Лютер получил степень магистра в Эрфуртском университете. Теперь он имел право заниматься одной из трёх «высших» дисциплин: юриспруденцией, медициной или теологией. Поскольку его отец хотел, чтобы он стал адвокатом, он поступил на юридический факультет. Примерно в это же время произошёл случай, изменивший ход жизни Лютера. Возвращаясь в университет после поездки домой, он попал в сильную грозу недалеко от деревни Стотернхайм и был почти поражён молнией. Погода так напугала его, что Лютер закричал Святой Анне: «Спаси меня, св. Анна, а я стану монахом!». Когда ему удалось благополучно сбежать, Мартин решил выполнить своё обещание. Многие историки, однако, считают, что этот инцидент был лишь катализатором, и идея стать монахом уже была сформулирована в уме Лютера. Более того, его друзья полагали, что недавняя смерть двух друзей также могла сыграть определённую роль в том, что он стал монахом.

2. Девяносто пять тезисов

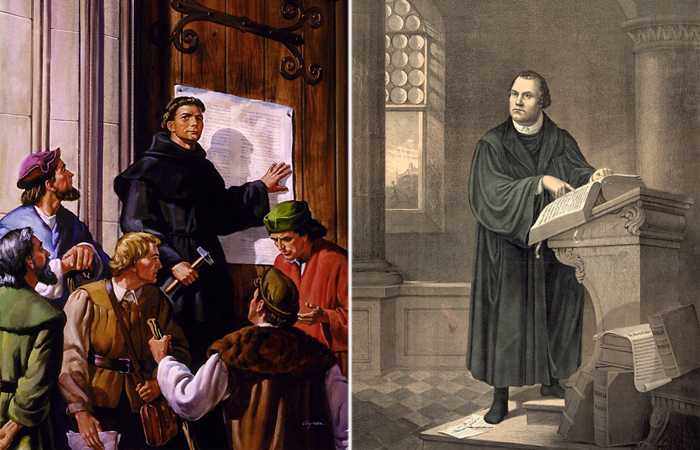

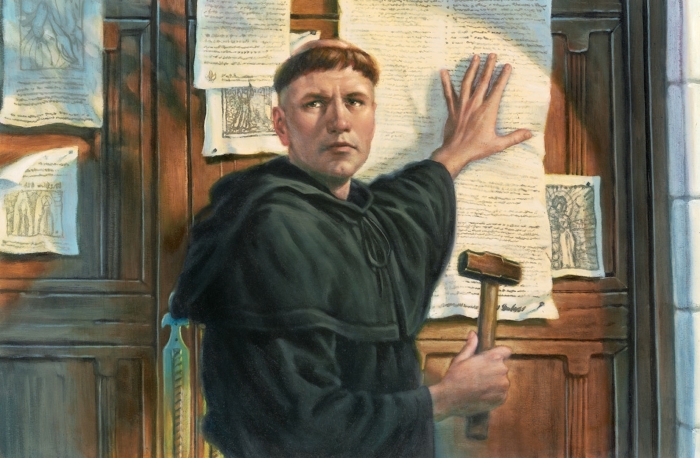

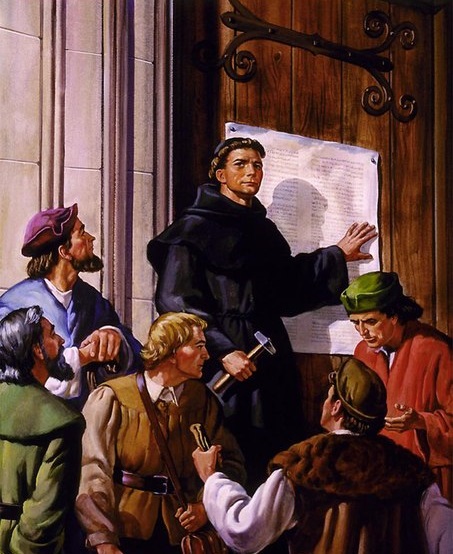

Изображение Мартина Лютера, прибивающего свои 95 тезисов к двери церкви. Фото: tinlanh.ru.

В 1516 году Альбрехт фон Бранденбург, архиепископ Майнца, который был глубоко в долгах, получил разрешение от Папы Льва X провести продажу особой пленарной индульгенции, которая давала бы отпущение временного наказания за грех. В ответ на это 31 октября 1517 года Мартин Лютер написал письмо Альберту Бранденбургскому, в котором приложил копию своего «диспута Мартина Лютера о силе и действенности индульгенций», ставшего впоследствии известным как Девяносто пять тезисов. Согласно популярной легенде, Лютер прибил копию своих девяносто пяти тезисов к двери церкви Виттенбергского замка. Тем не менее, многие учёные теперь считают, что он не прибивал тезисы, а скорее повесил их, как это было принято, чтобы начать академическую дискуссию о своей работе. Как бы то ни было, 31 октября 1517 года, день, когда он совершил этот акт, считается началом протестантской Реформации, а 31 октября ежегодно отмечается как День Реформации.

3. Печатная пресса

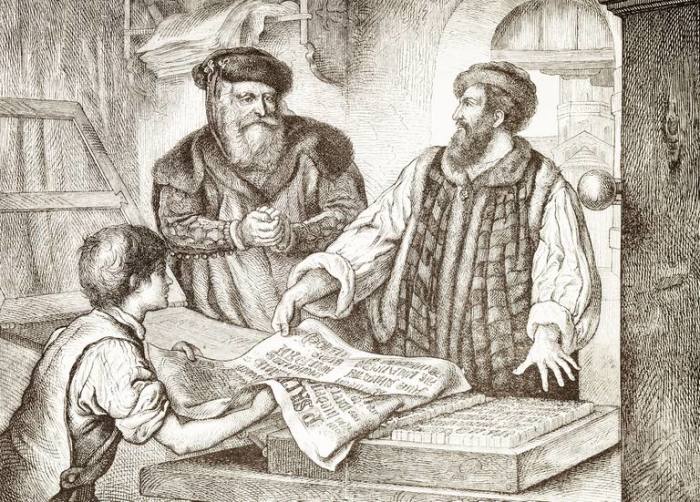

Иоганн Гутенберг — человек, который изобрёл первый печатный станок. Фото: thoughtco.com.

Учение Мартина Лютера распространилось, как лесной пожар, по всей Германии и за рубежом, поскольку оно обращалось к простым людям, которые были сыты по горло коррумпированными практиками католической церкви. Однако это стало возможным в первую очередь благодаря изобретению печатного станка Иоганном Гутенбергом в 1440 году. С помощью печатного станка Лютер начал печатать брошюры, которые печатались всего за один день и занимали от шестнадцати до восемнадцати страниц. Его первая немецкая брошюра была напечатана в 1518 году и была известна как «Проповедь об индульгенциях и благодати». Из-за скорости печатного станка, по крайней мере четырнадцать тысяч экземпляров проповеди были напечатаны в один год. Это позволило Лютеру распространить своё послание далеко и широко. Фактически, за первые десять лет реформационного движения было напечатано около шести миллионов брошюр. Удивительно, но целых двадцать пять процентов из них были написаны Мартином Лютером.

4. Лютер был похищен

Вормсский рейхстаг: Лютер на Диете червей — картина 1877 года Антона фон Вернера. Фото: ethikapolitika.org.

15 июня 1520 года Папа Лев X издал публичный указ, который предупреждал Мартина Лютера, что он рискует быть отлученным от церкви, если не отречётся от сорока одного приговора, взятых из его сочинений в течение шестидесяти дней. Лютер вместо этого публично поджёг декрет 10 декабря. Таким образом, он был отлучен от церкви Папой 3 января 1521 года. Затем, 18 апреля, строптивый и справедливый монах появился на заседании Сейма (ассамблеи) Священной Римской Империи, состоявшемся в Вормсе, Германия. На Вормсском рейхстаге (Диета Червей) Лютера снова попросили отречься от своих писаний. Однако, он подчеркнул, что будет поколеблен только разумом или если это будет написано иначе в Священном Писании. Лютер закончил своё свидетельство вызывающим заявлением: «Вот я стою. Боже, помоги мне. Я не могу поступить иначе». Учитывая напряжённую ситуацию, защитник Лютера, Фридрих Мудрый, понял, что его нужно спрятать, пока напряжённость с Церковью не спадёт. Поэтому он приказал группе рыцарей «похитить» Лютера, который затем был доставлен в замок в Эйзенахе, где он скрывался в течение десяти месяцев.

5. Предшественники

Проповедь Яна Гуса на Козим Градку (na Kozim hradku). Фото: pragagid.ru.

Попытки подавить Лютера и его последователей римско-католическими правителями оказались безуспешными, и в течение двух лет стало очевидно, что движение за реформу было очень сильным. В мае 1522 года Лютер вернулся в церковь Виттенбергского замка в Эйзенахе. К этому времени Реформация приобрела более политический характер, и другие реформаторы, в том числе Томас Мюнцер, Халдрих Цвингли и Мартин Бюсер, собрали массу последователей. Благодаря этому, после 1522 года, Мартин стал несколько менее влиятельным лидером движения. Кроме того, следует отметить, что у него было несколько предшественников, которые также недвусмысленно критиковали коррупционные практики римского католицизма. Джон Уиклифф и Ян Гус были самыми известными из этих критиков. Уиклифф был английским интеллектуалом, учёным и теологом. Он критиковал церковную практику индульгенций, а также показные церемонии и пышный образ жизни духовенства. Ян Гус был чешским священником, который также критиковал учение Церкви, произнося проповедь в своей собственной церкви. Он был казнён в 1415 году за своё восстание. Его работа, однако, привела к движению под названием Гуситы — до-протестантское христианское движение против Римско-Католической Церкви.

6. Его брак с бывшей монахиней создал огромный скандал

Катарина фон Бора и Мартин Лютер. Фото: mtzionlutheran.org.

Катарина фон Бора провела свою раннюю жизнь в монастырских школах, а затем стала монахиней. Однако после нескольких лет религиозной жизни она стала недовольна своей жизнью в монастыре и вместо этого заинтересовалась движением Реформации. Катарина вступила в сговор с другими заинтересованными монахинями и написала Мартину с просьбой о помощи. В канун Пасхи 1523 года Лютер послал Леонарда Коппе, торговца, который регулярно доставлял сельдь в монастырь, чтобы помочь монахиням бежать. Они сделали это, спрятавшись среди бочек с рыбой в его крытом фургоне. В течение двух лет Мартин устраивал дома, браки или работу для всех сбежавших монахинь, кроме Катарины, которая настаивала на том, чтобы выйти замуж за самого Мартина. 13 июня 1525 года Мартин Лютер женился на Катарине фон Бора. Это вызвало огромный скандал среди католиков и в то же время позволило другим священнослужителям в лютеранских церквях жениться. У пары родилось шестеро детей. Катарина считается влиятельным членом протестантского движения, поскольку она помогла определить протестантскую семейную жизнь и установить тон для браков духовенства.

7. Антисемитские взгляды

Антисемитские взгляды Мартина Лютера. Фото: evangelisch.de.

Одними из наиболее тревожных аспектов учения Мартина Лютера являются его глубоко антисемитские взгляды. В своё время он был более мягким и даже критиковал Католическую Церковь за её жестокое обращение с евреями. Со временем, однако, он стал гораздо более агрессивным и резким по отношению к евреям. Мартин утверждал, что иудаизм был ложной религией, и он также известен тем, что сказал: «еврейское сердце так же твердо, как палка, камень, железо, как дьявол». Его жестокие фантазии и оскорбительная риторика с каждым годом становились всё более опасными. Основные труды Лютера о евреях включали «О евреях и их лжи» и «Vom Schem Hamphoras und vom Geschlecht Christi» (о святом имени и происхождении Христа). Обе эти работы были опубликованы в 1543 году, всего за три года до его смерти. В этих работах Лютер утверждал, что евреи больше не были избранными, а были «народом дьявола». Более того, он даже использовал жестокие, оскорбительные выражения, чтобы ссылаться на евреев в этих текстах.

8. Его назвали в честь святого

Слева: «Святой Мартин отказывается от меча» — картина Симоне Мартини. Справа: Мартин Лютер. Фото: artchive.ru.

Святой Мартин Турский был солдатом в римской армии в IV веке, который отказался убивать людей, потому что он сказал, что это противоречит христианству. Он сделал это как раз перед битвой в галльских провинциях при Борбетомаге (ныне Вормс, Германия). Впоследствии его обвинили в трусости и посадили в тюрьму. В конце концов, он был освобождён и решил стать монахом. Святой Мартин стал одним из самых известных христианских святых в западной традиции. Мартин Лютер был назван в честь Святого Мартина, поскольку он был крещён в День Святого Мартина (11 ноября). Сходство между Мартином Турским и святым Мартином поразительно, поскольку оба оставили другой путь, чтобы стать монахами. Более того, Мартин Турский устроил свой протест в городе Вормс, там же, где проходила знаменитая Диета Червей Лютера.

9. Его имя носил один из величайших лидеров ХХ века

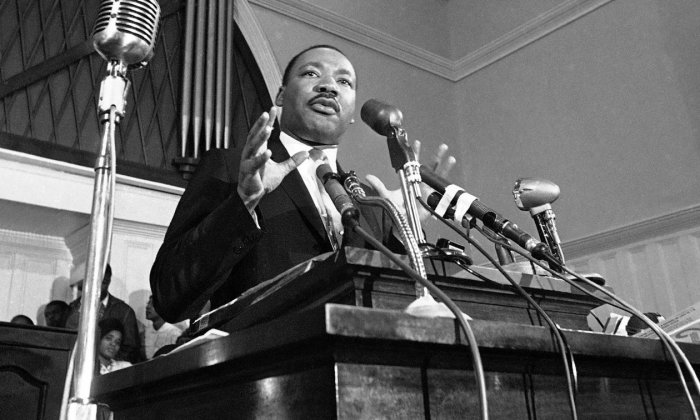

Мартин Лютер Кинг. Фото: eurotopics.net.

В 1934 году Майкл Дж. Кинг, пастор из Атланты в американском штате Джорджия, отправился в Германию. Посещая места, связанные с Мартином Лютером, он был настолько вдохновлён Лютером и историей Реформации, что решил изменить своё имя на Мартин Лютер Кинг. Следовательно, он также изменил имя своего пятилетнего сына на Мартина Лютера Кинга младшего. Как мы все знаем, Мартин Лютер Кинг-младший стал одним из самых известных лидеров XX века. Он боролся против дискриминации афроамериканцев в Соединенных Штатах и был самым видным лидером американского движения «За гражданские права». Он организовал и возглавил множество маршей за избирательное право чернокожих, десегрегацию, трудовые права и другие основные гражданские права. Его усилия принесли свои плоды, когда были приняты «Закон о гражданских правах 1964 года» и «Закон об избирательных правах 1965 года», и большинство из этих прав были введены в законную силу. 14 октября 1964 года Кинг получил Нобелевскую премию мира за руководство ненасильственным сопротивлением расовым предрассудкам в США. В возрасте тридцати пяти лет он был самым молодым получателем премии в то время.

10. Пророчество

Казнь Яна Гуса. Фото: spiritualpilgrim.net.

Ян Гус, чьё имя буквально означает «Гусь» на чешском языке, был чешским священником, который был важной фигурой в Богемской Реформации, движении против католической церкви, которое предшествовало протестантской Реформации. За выступление против церкви Гус был отлучён от неё и сожжён на костре 6 июля 1415 года. Перед самым сожжением он сказал: «Сейчас вы сожжёте гуся, но через столетие у вас будет лебедь, которого вы не сможете ни зажарить, ни сварить». Почти ровно столетие спустя (сто два года), 31 октября 1517 года, Мартин Лютер вывесил свои девяносто пять тезисов на двери Замковой церкви в Виттенберге, положив начало протестантской Реформации. Таким образом, многие считают, что пророчество Яна Гуса сбылось. Более того, Мартин Лютер находился под сильным влиянием учения Гуса и называл себя лебедем, о котором Гус пророчествовал. На похоронах Лютера в 1546 году это пророчество было упомянуто в проповеди. Кроме того, благодаря пророчеству Яна Гуса лебедь стал популярным символом, связанным с Мартином Лютером, и поэтому его часто можно увидеть в Лютеранском искусстве.

Читайте также о том, как династические браки разрушили одну из самых могущественных и влиятельных семей в истории.

Понравилась статья? Тогда поддержи нас, жми:

Содержание

- 1 Реформация — Мартин Лютер

- 2 Деятельная и радикальная Реформация — Томас Мюнцер

- 3 Жан Кальвин: божественное предопределение

Реформация — Мартин Лютер

Мартин Лютер (1483—1546) – немецкий теолог, идеолог Реформации (реформация католицизма). Он сформулировал основные тезисы, сплотившие на раннем этапе сторонников Реформации.

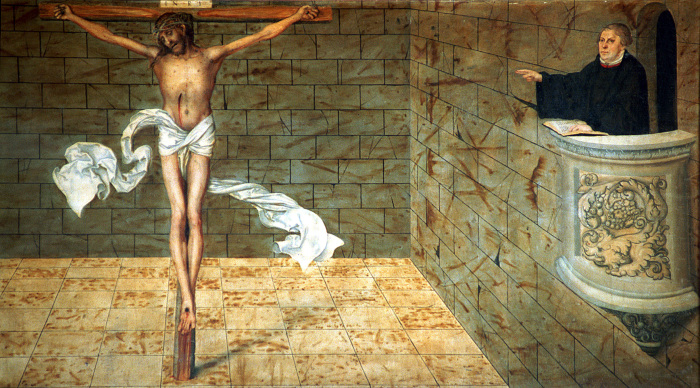

Главный тезис Мартина Лютера – спасение только в вере. Вера человека это его личный священник, только ей можно оправдаться оказавшись перед богом. Отсюда следует, что церковь более не нужна верующему. Бог не знает разграничений между чернью и знатью, между мирянами и церковниками – все равны перед ним. Это утверждение, наверное, одна из ранних идей равноправия.

Такая идея равноправия опирается на естественно-правовую природу, как производная от божьей воли. При этом, естественное право это право светское, то, что помогает правителям управлять внешним – собственностью, поведением людей. Отсюда принцип разумности и целесообразности управления человеческими отношениями государством. Однако, есть и божественное право вне юрисдикции государства – отвечающее за все то, что внутри человека, за его духовный мир.

При этом, такое равноправие в теории Мартина Лютера не является причиной установления демократических принципов. Напротив, деятель Реформации призывал к подчинению монарху и терпению чинимого им произвола.

Мартин Лютер проповедовал отделение церкви от государства. Папская власть в его воззрениях может только помогать укреплять авторитет монарха. Это сработало на укрепление абсолютизма светской власти. Для политического сознания Германии того времени вообще была присуща идея всепроникающей веры в светское государство. А то, что Мартин Лютер ратовал за внутреннюю религиозность только укрепило его позиции.

Таким образом, то, за что выступал первый деятель Реформации, не сыграло на руку его учению. Еще больше стало царить бюргерство, религиозный фанатизм, эксплуатация крестьян.

Деятельная и радикальная Реформация — Томас Мюнцер

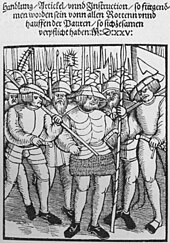

Томас Мюнцер (ок. 1490—1525) напротив, возглавил радикальную реформацию, крестьянско-плебейский её сектор. Это движение вело свою войну против всякой эксплуатации и неравенства.

Кульминацией стала Крестьянская война в Германии (1524—1526).

Требования и идеи крестьян были описаны в «12-ти статьях» и в «Статейном письме». «12 статей» это сборник конкретных и вполне умеренных требований – отмена крепостничества, выборность и сменяемость духовенства, уменьшение налоговой нагрузки, эффективность судопроизводства и прочего. Томас Мюнцер и его ближний круг в свою очередь выпустили «Статейное письмо» с более радикальными положениями. Авторы призывали объединиться в христианский союз и братство и революционными методами сломать существующий порядок, превратить страну в справедливое государство «общей пользы».

По мысли Томаса Мюнцера стоило передать власть простому народу, в коем он видел людей, свободных от эгоизма. Этот деятель яростно осуждал Мартина Лютера в его утверждении светского государства и видел в этом узурпацию власти узкой прослойкой людей. При этом, главной целью виделось сбросить безбожников с трона, воспользоваться силой крестьян.

Томасом Мюнцером точно не описывалось каким должно быть это государство общей пользы. Мы не найдем в его учении ни формы устройства, ни описания процесса управления. Можно просмотреть только зачатки демократических идей. Но отчетливо просматривается необходимость обеспечения охраны основ государства, контроль его населением.

Теологическая составляющая черпалась Томасом Мюнцером из Библии. Отсюда тяга к установлению «царства Божьего» на практике, как государства без классового разделения, частной собственности.

Жан Кальвин: божественное предопределение

Жан Кальвин (1509—1564) еще один видный теоретик Реформации, запомнившийся работой, которую написал уже в Швейцарии — «Наставление в христианской вере» (1536). Основной тезис его учения – божественное предопределение. Бог заранее предопределил все — судьбы людей, в том числе загробные (кому суждено спастись). О таком спасении человек может догадаться уже на земле – если он успешен в миру и покорен властям, то спасется.

Из главного тезиса следует стремление каждого кальвиниста отдавать себя своему профессиональному пути без остатка, бережливо вести хозяйство и отрицать наслаждение. Таким образом, сословные разделения и привилегии не важны.

Этот протестантский тезис, как позднее изложил Макс Вебер в своем труде «Протестантская этика и дух капитализма» (1905) стал причиной экономического подъема протестантских стран и задержки их в топе рейтингов по экономическим показателям.

Немаловажное значение было и у реформы устройства церкви, задуманной Жаном Кальвином. Церковная община стала возглавляться пресвитерами, избираемыми из наиболее успешных людей и проповедниками без церковного сана, которые образовали консисторию.

Именно эта реформа была воспринята политическими деятелями для развития республиканских программ. Однако, рассуждая о власти Жан Кальвин с одной стороны ругал знать за произвол надо подданными и беззаконием, угрожал ей карой с небес, с другой призывал каждого верующего к подчинению.

Конечно, право на сопротивление у народа есть, но с двумя оговорками. Во-первых, творимые насилие и произвол должны стать более нестерпимыми. Во-вторых, должны быть исчерпаны мирные методы борьбы.

Несмотря на все указанное, наихудшая форма правления по Кальвину – демократия, лучшая – олигархическая.

Кроме того, учение Кальвина характеризуется нетерпимостью к другим религиозным взглядам и крестьянским ересям. Рассматриваемый деятель, в период руководства консисторией в Женеве, подчинил ей магистрат города, установил слежку за простыми горожанами, жестко регламентировал все стороны жизни. За отступление от правил следовало жесткое наказание, казни еретиков стали обыденностью.

Оценивая роль этой идеологии в истории стоит упомянуть, что большое значение она имела в первой буржуазной революции, установлению республики в Нидерландах, формированию республиканских партий в Англии. Кальвинизм стал кормом мировоззрения буржуазии.

Библия, а не церковь. Христос, а не папа римский

С таким девизом, в котором переосмысливаются религиозные ценности, выступил в конце XIV века, ещё задолго до Реформации, Джон Виклиф, профессор Оксфордского университета. Он стал человеком, который напомнил католикам о старых идеях, на которых выросло христианство. За что и был сочтён еретиком.

Один из предшественников протестантизма, Джон Уиклиф первым перевёл Библию на английский язык, однако римская церковь не оценила его стараний, поскольку она была наделена абсолютной монополией на толкование Библии. Уилклиф учил, что каждый человек связан с Богом напрямую, и для этого ему не нужны никакие посредники. За эти деяния, а также за то, что клеймил Папу Римского отступником и антихристом, он и был уволен из Оксфорда, его учеников при этом вынудили отречься от его взглядов.

Владислав Муттих. «Ян Гус на костре в Констанце». (Pinterest)

Однако распространению его идей это уже не могло помешать: учение виклифистов стало идейной основой для общины лоллардистов и для проповедей Яна Гуса. Последний за свои идеи был сожжён на костре вместе со своими трудами. Труп Уиклифа был выкопан по решению Констанцского собора и тоже сожжён на костре. Показательные казни надолго отбили у мыслителей желание реформировать церковь.

«На том стою. Не могу иначе. Да поможет мне Бог»

Эту известную фразу Мартин Лютер произнес на Вормсском рейхстаге, стоя перед императором Священной Римской империи, курфюрстами и архиепископами. Слова эти обозначали полный отказ от отречения, после них он был вынужден бегством спасаться от преследующей его инквизиции.

А начиналась эта история довольно безобидно — в октябре 1517 года достопочтенный отец Мартин Лютер, доктор богословия Виттенбергского университета, был вне себя от развращённости римско-католического клира. В то время Папа Римский Лев X, привыкший к роскоши и ощутивший вдруг острую необходимость в средствах, официально от имени церкви разрешил торговлю индульгенциями по всей Европе.

Праведный гнев Лютера вылился в знаменитые 95 тезисов, которые богослов составил в надежде искоренить пороки внутри церкви. Судьбоносную для всей Европы табличку с тезисами, как гласит предание, Мартин Лютер 31 октября 1517 года прибил к воротам дворцовой церкви Виттенберга.

Есть мнение, что вся история с прибитой табличкой — лишь красивая легенда. (Pinterest)

Одним из ключевых событий Реформации стал Лейпцигский диспут, где Мартин Лютер в очередной раз высказал свои идеи в споре с Иоганном Экком. Когда Лютер в своей речи дошёл до того, что стал с некоторых позиций оправдывать Яна Гуса, Герцог Георг, памятуя о дурном наследии гусситов в Саксонии, разразился проклятиями. После этого Мартин Лютер получил первую тревожную весточку — папскую буллу, в которой осуждались его взгляды. Собрав вокруг себя толпу, богослов сжёг буллу за подписью самого Папы Римского, чем полностью разорвал отношения с римской католической церковью.

Папа Римский Лев X к критике отнёсся однозначно — он предал Лютера анафеме, отлучил от церкви и хотел заставить того приехать на Вормсский рейхстаг, чтобы богослов публично отрекся от своих убеждений.

Лютер спрятан, но дело его живёт

После окончания Вормсского рейхстага Мартин Лютер направился домой в Виттенберг. Не успел он как следует отъехать от Вормса, как его похитили люди курфюрста Саксонии… и спрятали в укромном месте, в замке Вартбург. Как оказалось, Фридрих Мудрый, отличавшийся пытливым умом, на собрании рейхстага проникся речами Мартина Лютера и решил сберечь того от неминуемого наказания. Причём для того, чтобы не врать императору Карлу V на допросе, он специально приказал своим людям не предупреждать его о том, где они спрячут богослова-мятежника.

Лютер на Вормсском рейхстаге. (Pinterest)

Мартин Лютер, будучи узником Вартбургского замка, который он не мог покинуть, занялся переводом Библии на немецкий язык. Однако это не помешало распространению его идей: только они стали развиваться совершенно не в том русле, как планировал инициатор Реформации. Так называемый «духовный мятеж», мирный путь Реформации, о котором и проповедовал изначально Лютер, широкой поддержки в народе не получил. Зато в родном для Мартина Лютера Виттенберге начались погромы католических храмов, которые поддерживали последователи богослова — Цвиллинг и Карлштадт.

Римская церковь не готова была терпеть погромы в собственных храмах. Обе стороны взялись за оружие. Религиозный конфликт стал приобретать кровавый характер, и в итоге вылился в грандиозную войну, которую нарекли Тридцатилетней (1618−1648). Эта война привела к тому, что на территории Германии — а за ней и в других европейских странах — католическая и лютеранская церковь стали существовать параллельно.

Мартин Лютер и его реформационные идеи

Мартин Лютер и его реформационные идеи

Реформация (от лат. reformatio — «преобразование») — религиозное и социально-политическое движение в Европе XVI в., выдвигавшее требования реформы католической церкви и преобразования порядков, санкционированных ее учением.

Начало Реформации в Германии связано с именем Мартина Лютера (1483—1546), монаха-августинца и профессора Виттенбергского университета, который в 1517 г. открыто выступил против индульгенций. Его с юношеских лет отличала глубокая религиозность; в 1505 г., получив степень магистра «свободных искусств», он вопреки воле отца, желавшего видеть своего сына юристом, становится монахом августинского монастыря в Эрфурте. В надежде на спасение души будущий реформатор строго выполнял монашеские предписания (посты и молитвы). Однако уже тогда у него зародились сомнения в правильности этого пути. Став в 1507 г. священником, Лютер по настоянию своего ордена продолжил университетское образование на факультете теологии Эрфуртского университета. Поездка в 1511 г. в Рим и впечатления отличного знакомства с развращенными нравами высшего католического клира усилили в Лютере стремление к поиску тех основ христианской догматики, которые должны были отвечать внутренней религиозности, а не обрядовой, внешней Стороне культа.

Лукас Кранах Старший. Портрет Мартина Лютера. 1522 г.

С 1512 г., после получения степени доктора богословия, Лютер начал читать лекции в университете г. Виттенберга. Здесь он обратился к углубленному изучению Библии, к тому же он как лектор вынужден был вырабатывать свои трактовки библейского текста. В 1512—1517 гг. постепенно начинает оформляться его теологическая концепция. 18 октября 1517 г. папа римский Лев X издал буллу об отпущении грехов и продаже индульгенций в целях, как утверждалось, «оказания содействий построению храма св. Петра и спасения душ христианского мира». Этот момент и был избран Лютером для того, чтобы в тезисах против индульгенций изложить свое новое понимание места и роли церкви. 31 октября 1517 г. Лютер прибил к дверям университетской церкви в Виттенберге «95 тезисов» («Диспут о прояснении действенности индульгенций»). Он, конечно, не думал о противостоянии с церковью, а стремился к очищению ее от пороков. В частности, он поставил под сомнение особое право пап на отпущение грехов, призывая верующих к внутреннему раскаянию, которому отводилось главная роль, в обретении «спасающей помощи Божьего милосердия».

«Тезисы» Лютера, переведенные на немецкий язык, за короткий срок обрели феноменальную популярность. Вскоре для опровержения лютеровских тезисов были выставлены опытные католические теологи: распространитель индульгенций в Германии Тецель, доминиканский монах Сильвестр Маззолини да Приерио и известный богослов Иоганн Экк. Все они, критикуя Лютера, исходили из догмата о непогрешимости папы. Против Лютера было составлено обвинение в ереси, а 7 августа 1518 г. ему было передано приказание явиться на суд в Рим. Однако, опираясь на поддержку своих сторонников, в том числе и среди представителей власти, Лютер отказался.

Папскому легату в Германии пришлось согласиться с предложением подвергнуть Лютера допросу в Германии. В октябре 1518 г. Лютер прибыл в Аугсбург, где в то время заседал рейхстаг. Здесь Лютер заявил, что не отречется «ни от единой буквы» своего вероучения. Конец периоду переговоров папской курии с Лютером положил диспут, состоявшийся летом 1519 г. в Лейпциге между ним и Экком. Когда Экк обвинил Лютера в том, что он повторяет ряд положений, близких к учению Гуса, Лютер заявил, что среди положений Гуса имелись «истинно христианские и евангелистские». Это заявление означало не только опровержение «высшей святости» папы, но и авторитета соборов. Только Священное Писание непогрешимо, заявил Лютер, а не папа и вселенские соборы. Таким образом, результатом лейпцигского диспута был открытый разрыв Лютера с Римом.

В трактате «К христианскому дворянству немецкой нации об улучшении христианского состояния» (1520) Лютер обосновал освобождение от папского засилья тезисом о том, что служение Богу рассматривается не как дело одного духовенства, а как функция всех христиан, их мирских учреждений и светской власти. Так была высказана идея «всеобщего священства», которым обладали все христиане. Параллельно с этим Лютер разработал программу борьбы с папством и реформирования церкви. Он призвал немцев прекратить выплаты Риму, сократить число папских представителей в Германии, ограничить вмешательство папы в управление империи. Важным пунктом в национальном развитии немцев стал призыв к чтению мессы на немецком языке. Далее Лютер потребовал закрытия монастырей нищенствующих орденов и роспуска всех духовных братств, отмены церковных иммунитетов, отлучений, многочисленных праздников, целибата духовных лиц.

К этому же моменту можно говорить уже о сложившейся системе богословских взглядов Лютера. Основное положение, выдвинутое им, гласило, что человек достигает спасения души (или «оправдания») не через церковь и ее обряды, а с помощью личной веры, даруемой человеку непосредственно Богом. Смысл этого утверждения заключался, прежде всего, в отрицании посреднической роли духовенства между верующими и Богом. Другой тезис Лютера сводился к утверждению приоритета Священного Писания над Священным Преданием — в виде папских декретов и постановлений вселенских соборов. Это положение Лютера, как и первое, противоречило католической догме о централизованной универсальной церкви, распределяющей по своему усмотрению Божественную благодать, и о непререкаемом авторитете папы как вероучителя.

Однако Лютер не отвергал полностью значения духовенства, без помощи которого человеку трудно достигнуть состояния смирения. Священник в новой церкви Лютера должен был наставлять люден в религиозной жизни, в смирении перед Богом, но не мог давать отпущение грехов (это дело Бога). Лютером отрицалась та сторона католического культа, которая не находила подтверждения и оправдания в букве Священного Писания, поэтому другое название лютеранской церкви — евангелическая церковь. Среди церковной атрибутики, отвергнутой Лютером, оказались поклонение святым, почитание икон, коленопреклонение, алтарь, иконы, скульптуры, учение о чистилище. Из семи таинств было сохранено в конечном итоге только два: крещение и причастие.

Историческое значение выступления Лютера заключалось в том, что оно сделалось центром сложной по своему социальном составу оппозиции. Вокруг Лютера объединились различные элементы германского общества, от умеренных до самых радикальных, выступившие под флагом новой концепции христианского учения против папской власти, католической церкви и их защитников: рыцарство, бюргерство, часть светских князей, рассчитывавших на обогащение путем конфискации церковных имуществ и стремившихся использовать новое вероисповедание для завоевания большей независимости от империи, городские низы. Широкий социальный состав сторонников Лютера обеспечил вскоре ряд значительных успехов лютеранской Реформации. Правда, сам Лютер неоднократно уточнял, что христианская свобода должна пониматься только в смысле духовной свободы, а не телесной. Лютер считал недопустимым аргументировать необходимость политических и социальных изменений ссылками на Священное Писание.

Триумфом Лютера стал Вормский рейхстаг 1521 г., где Лютер категорично заявил об отказе отречься от своих реформационных идей («На том стою и не могу иначе…»). Императорский указ, известный под названием «Вормский эдикт», запрещал на всей территории империи проповедь в духе Лютера и предавал Лютера опале, а его сочинения — сожжению. Однако он не возымел нужного действия и не приостановил распространение лютеровского учения. Найдя пристанище в замке курфюрста Саксонии Фридриха Мудрого (1463—1525), Лютер осуществил перевод на немецкий язык Нового Завета, тем самым дав в руки своих сторонников мощное идеологическое оружие.

Наступившая после Вормского рейхстага дифференциация антиримского движения, выделение из него радикальных группировок, которые в понимании задач реформ расходились с Лютером, заставили его определенно высказаться, прежде всего, по вопросу о способах и методах претворения в жизнь общих принципов Реформации. Лютер упорно отстаивает свою программу «духовного мятежа», центральным моментом которой был тезис о непризнании католической церкви в Германии и борьбе с нею исключительно мирными средствами. Поэтому Лютер не поддержал рыцарское восстание 1522—1523 гг., осудил бюргерство, стремившееся к коренным преобразованиям церкви (в том числе и путем насилия) и проведению социальных реформ.

Чем больше реформационные лозунги привлекали немцев, тем важнее было Лютеру определиться с той политической силой, которая будет осуществлять Реформацию. Реалии Германии того времени вели Лютера к мысли, что такой силой могла стать княжеская власть, представитель которой, саксонский курфюрст Фридрих Мудрый, не раз в 1517—1521 гг. защищал реформатора. Более того, идея о «всеобщем священстве» позволяла рассматривать княжескую власть как подлинно апостольскую, а значит, ей и должна была принадлежать руководящая роль в новой церкви. Окончательно Лютер сформулирует свои взгляды на этот вопрос после попытки в 1522 г. анабаптистов, переселившихся в Виттенберг, осуществить Реформацию в собственной трактовке. Поскольку Лютер не верил в способность церкви на внутреннюю реформу и считал недопустимым проведение преобразований народом, он доказывал, что право осуществлять Реформацию принадлежит только государям и магистратам. Духовная власть, таким образом, подчинялась светской.

В отечественной историографии преобладала оценка лютеровского реформационного учения как идеологии умеренного бюргерства. Наличие этой более или менее аргументированной точки зрения не отрицает возможности видеть в М. Лютере общенационального идеолога немецкой Реформации. Лютер обращался ко всей немецкой пастве с универсальными (важными для представителей всех социальных и профессиональных групп) религиозными проблемами и обсуждал не менее универсальные христианские ценности. Главное, что волновало его — правильность веры для спасения души. Сам Лютер никогда не говорил определенно о какой-то социальной предпочтительности своего учения, даже его «симпатии» к князьям были связаны не с содержанием Реформации, а с ее осуществлением.

Конечно, реализация некоторых идей Лютера представляла известный интерес для бюргерства — как умеренного, так и радикального, — но в то же время «плодами» Реформации воспользовались и князья, и дворяне, и патрициат, и даже крестьянство.

Простому человеку Лютер отводил крайне пассивную роль как в религиозной, так и в общественной жизни, что противоречило активной позиции бюргерства начала XVI в. Характерно высказывание М. Лютера: «Праведен не тот, кто много делает, а тот, кто без всяких дел глубоко верует в Христа… Закон гласит: сделай это — и ничего не происходит. Милосердие гласит: веруй в этого — и сразу все сделано». Такое видение проблемы резко отличало М. Лютера от настоящих идеологов бюргерства У. Цвингли и Ж. Кальвина. Но обращение Лютера к проблеме человека, внимание к его личным переживаниям, стремление возвести в абсолют религиозной деятельности персональное общение с Богом говорит о том, что реформатор смог найти религиозное выражение ментальным процессам индивидуализации сознания. Неслучайно современные немецкие историки трактуют лютеранское вероучение как «эмансипацию индивидуума», основанную на лучших достижениях человеческой мысли XVI столетия.

Читайте также

Мартин Лютер

Мартин Лютер

Великий немецкий реформатор родился в ноябре 1483 г. в Эйслебене, главном городе тогдашнего графства Мансфельд в Саксонии. Родители его были бедные крестьяне из деревни Мера того же графства, незадолго до того переселившиеся в город, чтобы искать заработка на

Ян Гус, Иероним Пражский и Мартин Лютер

Ян Гус, Иероним Пражский и Мартин Лютер

На всей территории Священной Римской империи в Средние века постоянно вспыхивали восстания против католической церкви и папы римского. В XV веке началась эпоха борьбы за перемены, получившая в истории название эпохи Реформации.

Мартин Лютер и его реформационные идеи

Мартин Лютер и его реформационные идеи

Реформация (от лат. reformatio — «преобразование») — религиозное и социально-политическое движение в Европе XVI в., выдвигавшее требования реформы католической церкви и преобразования порядков, санкционированных ее учением.Начало

7. Мартин Лютер

7. Мартин Лютер

В то время как католическая церковь столь безуспешно сражалась за удержание господства на всех землях, в Европе для нее назревала большая угроза.Несколькими годам раньше Мартин Лютер прикрепил свои знаменитые тезисы к двери Виттенбергской церкви, чем

Мартин Лютер: рождение новой церкви

Мартин Лютер: рождение новой церкви

Мартин Лютер — основатель лютеранской церкви, которая по сей день играет в мире заметную роль. Мыслитель, богослов, филолог, писатель начала XVI века, переводчик «Библии», заложивший основы немецкого литературного языка. Его «95 тезисов»

МАРТИН ЛЮТЕР

МАРТИН ЛЮТЕР

Я тут весь перед вами…

Да поможет мне бог.

Мартин Лютер.

Мартин Лютер был сыном рудокопа из городка Эйслебен на востоке Германии; его отец работал в каменоломнях, а мать собирала в лесу дрова. С трудом, нищенствуя и голодая, ему удалось закончить школу и

Ян Гус, Иероним Пражский и Мартин Лютер

Ян Гус, Иероним Пражский и Мартин Лютер

На всей территории Священной Римской империи в Средние века постоянно вспыхивали восстания против католической церкви и папы Римского. В XV веке началась эпоха борьбы за перемены, получившая в истории название эпохи

Лютер Мартин (Род. в 1483 г. – ум. в 1546 г.)

Лютер Мартин

(Род. в 1483 г. – ум. в 1546 г.)

Немецкий религиозный и общественный деятель, теолог, глава Реформации в Германии, основатель немецкого протестантизма (лютеранства – первого протестантского направления в христианстве), переводчик Библии на немецкий язык.

9.4.5. За какую мечту боролся Мартин Лютер Кинг?

9.4.5. За какую мечту боролся Мартин Лютер Кинг?

Имя Майкл родившийся в 1929 г. мальчик получил от отца, пастора баптистской церкви, в честь основателя протестантизма Мартина Лютера. Кинг стал священником, бакалавром, затем доктором богословия, священником в штате Алабама. Он

Лютер Мартин

Лютер Мартин

1483–1546Деятель Реформации в Германии, основатель немецкого протестантизма.Мартин Лютер родился 10 ноября 1483 года в городе Эйслебене в Тюрингии (Германия). Его родители, Ганс и Маргарита Людер, переехавшие туда из Мёры, вскоре перебрались в Мансфельд, где Ганс

Кинг Мартин Лютер

Кинг Мартин Лютер

1929–1968Лидер Движения за гражданские права чернокожих в США.В семье пастора баптистской церкви в городе Атланта 15 января 1929 года родился первенец, мальчик. Его назвали Майкл. Мать Мартина до замужества преподавала в школе. Детство Кинга пришлось на годы

Мартин Лютер (1483–1546)

Мартин Лютер (1483–1546)

Вернемся к персонажу, об отлучении которого мы рассказали. Сын саксонского крестьянина Мартин Лютер в 1505 г. постригся в монахи, заботясь о спасении души. Эта тревога продолжает его мучить и в духовном сане, он боится, что не сможет устоять перед грехом.

Молодые годы Мартина

Начало XVI века можно назвать эпохой Мартина Лютера — основателя протестантизма и отца Реформации. Его подробная биография полна событий.

Родился Мартин 10 ноября 1483 года в саксонском городе Айслебен. Родители Лютера были бедными крестьянами. Отец — Ганс и мать — Маргарита переехали сюда незадолго до рождения сына из близлежащей деревушки.

Жизнь в городе, вопреки ожиданиям, была не легче деревенской. Отец устроился на медные рудники, а мать на спине носила дрова. Лишь крайняя умеренность спасала семью от полной нищеты. И все же Мартин искренне гордился своим христианским происхождением.

Отец мальчика был очень суров со своим первенцем и однажды наказал сына так, что тот убежал из дома. Не отличалась нежностью и мать семейства. Как-то она избила сына до крови. Строгость воспитания сделала Лютера сдержанным, даже замкнутым.

Главной надеждой в семье был Мартин. Отец мечтал, чтобы сын выучился и стал бургомистром. Мартин был озабочен тем, чтобы заслужить любовь и похвалу родителей.

В 1501 году он стал студентом университета города Эрфурт. Когда через 2 года Мартин получил степень бакалавра, отец, доходы которого теперь уже значительно выросли, стал выплачивать ежемесячное пособие на его содержание.

На юридическом факультете Эрфуртского университета парень научился произносить длинные и серьёзные речи, за что получил прозвище «философ».

По старому студенческому обычаю, молодой человек зарабатывал на жизнь уличным пением и игрой на лютне, в чём достиг немалых успехов.

В 1505 году, окончив университет со степенью магистра, Мартин ушел в Августинский монастырь, и хотя этот шаг казался близким совершенно неожиданным, на тот момент у Мартина была на то причина. Один из университетских друзей Лютера умер от удара молнии. Это событие просто ошеломило молодого человека. Спустя некоторое время молния ударила в землю уже рядом с самим Лютером. Он так испугался, что выкрикнул: «Святая Анна помоги мне, я стану монахом».

И уже через 2 недели Мартин выполнил это обещание. Тогда отец, который после получения юношей ученой степени стал обращаться к сыну исключительно на вы, отрекся от него. Чтобы выполнить обет, он продал свои книги и ушёл в монастырь августинцев, известный особой строгостью устава.

Протест против продажи индульгенций

Единственным грехом новоприбывшего в Августинский монастырь послушника Мартина была неуемная тяга к знаниям. Господь не любит тех, кто крутится рядом с древом познания. В монастыре юноша принялся с остервенением изучать Священные Писания.

Он хотел взять небеса штурмом. Мартин подстегивал ум жесткой аскезой, постился по трое суток, не мылся, не менял одежду, спал без постели, едва не умер от переохлаждения. Его все время тревожило, достаточно ли он хорошо себя ведет, чтобы добиться божественного прощения.

Много физических ограничений он наложил на себя сам, помимо обязательных аскез. За 3 года в монастыре Мартин разрушил свое здоровье. Он стал испытанием для братьев по монастырю. Молодой человек денно и нощно искал в себе пороки, изнурял исповедями священников.

В ноябре 1508 года Лютер, приняв приглашение Фридриха Мудрого, начал преподавать в недавно созданном этим саксонским курфюрстом Виттенбергском университете. В 1510 году он съездил в Рим, где своими глазами увидел роскошь и разврат среди Верховного духовенства. Чувства пламенного католика были оскорблены. Особенно его возмущало, что любой человек мог купить индульгенцию и за деньги получить прощение самых страшных грехов.

В 1512 году молодой священник стал доктором богословия. Эта ученая степень давала ему право толкования Библии. В 1516 году талантливый доктор теологии стал проповедником соборной церкви Виттенберга. Народ слушал его, внимая каждому слову, ведь выходец из крестьянской семьи отлично знал, как общаться с обычными людьми.

Молодой реформатор встряхнул христианский мир до основания. 31 октября 1517 года Лютер дал залп по католической церкви. Свой протест против продажи индульгенций он сформулировал в 95 тезисах, которые прикрепил на дверях Виттенбергской церкви.

Он выступил с критикой роли церкви в спасении души. В своих тезисах он просил отменить продажу индульгенций. Вначале Лютер и не думал ни о какой Реформации. Таким необычным способом, обнародовав свои тезисы, он лишь хотел свободно обсудить проблему.

Но поступок Лютера наделал столько шума, что некоторые папские инквизиторы прямо потребовали сожжения еретика. Нападки противников вынудили Лютера пойти дальше.

Вера — краеугольный камень

Он пишет разъяснения к тезисам, в которых ставит под сомнение непогрешимость Папы, хотя пока еще Лютер согласен ему подчиняться. Тезисы вызвали ожесточенную полемику по всей Германии. От критики индульгенций сторонники Лютера перешли к обсуждению самих католических догматов.

Тогда папа Лев X издает буллу, в которой угрожает отлучить вольнодумца от церкви. 10 декабря 1520 года перед городскими воротами Виттенберга Мартин публично сжигает папское послание. Ответ Папы не заставил себя долго ждать — 37-летний ученый был отлучен от церкви. Так началась Реформация.

Энгельс давал сравнительную характеристику Мартину Лютеру. Он ставил его в один ряд с такими титанами, как Леонардо да Винчи, Альбрехтом Дюрером и Никколо Макиавелли. Полное собрание сочинений Лютера насчитывает 38 томов.

Отлученный от церкви, Мартин укрылся в замке саксонского князя, чтобы не попасть в лапы инквизиции. Он занялся разработкой собственного вероучения, которое впоследствии назовут протестантским. Он вошел в историю как идейный лидер протестантского движения, вождь его старейшей конфессии — Лютеранства. Его учение сократило дистанцию между богом и человеком.

Суть учения

Лютер пришёл к мысли, что спасение души лежит в самой вере. Это стало основным постулатом реформаторского учения Мартина Лютера. Вера — краеугольный камень учения, и разгадка его фантастической популярности. Он по-новому осмыслил Новый Завет. На одной чаше весов были католики, на другой лютеране.

Искренняя вера искупает грехи и удерживает от неправедных поступков. В отличие от католичества, которое требовало формального исполнения обрядов, протестантизм был направлен к сердцу каждого верующего.

Учение Лютера «Спасение верой»:

- человек спасается только верой;

- вера обретается только через милость Бога;

- только Священное Писание и слово Божье является авторитетом в делах веры.

Лютер утверждал, что отношения между Богом и человеком имеют личный характер и не нуждаются во вмешательстве церкви, которая должна лишь помочь людям постичь Библию.

Он, как наиболее образованный богослов, перевел Библию на немецкий язык, сделав древние тексты доступными для народного чтения. Лютер заложил основы немецкого языка, на котором будут писать Гете, Шиллер, Кант и другие известные авторы.

Реформация совпала с развитием в Европе книгопечатания. Силой печатного и не печатного слова Лютер изменил религиозную и культурную жизнь миллионов людей на века вперед.

Ученый-богослов хотел реформировать только церковь, но его идеи обрели собственную жизнь и воспламенили весь мир западного христианства.

Крестьянская война

В тот год, когда Мартин ушел в монастырь, астрологи предсказали, что примерно через 20 лет, когда все планеты соберутся в созвездии Рыб, начнутся войны, беды и лишения. Накануне небесного собора в 1521 году было опубликовано более полусотни предупреждающих трактатов. Гравюры изображали великую рыбу на небе и потрясения на Земле.

Лютер не верил астрологам и астрономам. Коперника обзывал дураком. В назначенный срок в 1524 году началась крестьянская война. Лютер был против народных мятежей, и как типичный немецкий бюргер высказывался за расправу над мятежниками и восстановление порядка.

Через 2 года мятеж был подавлен, но Германия к тому времени стала уже совершенно другой страной. Лютеранская церковь приобретала всю большую популярность.

Она становилась более понятной и доступной. Освобождалась от икон и сложных обрядов, во многих городах Германии закрывались католические монастыри и вводилось новое богослужение на немецком языке.

Основные идеи лютеранства:

- оправдание верой;

- отказ от продаж индульгенций;

- секуляризация церковного имущества;

- верховенство Священного Писания;

- доступность Библии для всех слоев населения.

Некоторые исследователи предполагают, что мнимые грехи, в которых каялся Лютер, связаны с бурным воображением юноши, лишенного общения с девушками. Но в списке искушений он отдавал первенство не любовным бесам. Мартин хотел одного — верить, не испытывая сомнений. Он хотел слишком многого. Отныне главным искушением Лютера станет грех уныния.

Значение исследований Лютера

Примерно в это же время Лютер познакомился с Катариной фон Бора. Возраст замужества был уже на исходе, ей исполнилось 24 года, когда неведомым путем к ней попали запрещенные проповеди еретика Мартина Лютера.

Избранница долгое время жила в католическом монастыре, куда ее отдали ещё в детстве. Однако прочитав сочинение Мартина Лютера, она и еще 10 ее подруг решили оттуда сбежать. Организовать побег помог сам Лютер. В 1525 году 42-летний ученый женился на 26-летний Катарине фон Бора.

В своих учениях Лютер во всех бедствиях и муках человечества видел происки дьявола. Он был убежден, что и сам вовлечен в борьбу с ним. Он страдал галлюцинациями, в которых всегда присутствовал дьявол.

Последние годы жизни Лютер страдал от различных хронических недугов. Он умер в Айслебене 18 февраля 1546 года.

Значение учений Лютера:

- совершенно иной взгляд на человека шел вразрез с существующими нормами феодального строя, в котором сословия олицетворяли собой коллективное начало;

- его идеи легли в основу появления протестантизма и протестантской этики, сыгравших ключевую роль в дальнейшем экономическом развитии Европы;

- Реформация подготовила почву для буржуазных революций, борьбы с абсолютистскими режимами, развития рыночных отношений.

Его судьба стала ярким примером идеи Реформации. Человек из крестьянской семьи стал идейным вождем нации и предопределил судьбу Европы.

Читайте также про чайный протест, или Бостонское чаепитие.

- Энциклопедия

- Люди

- Лютер Мартин

10 ноября 1483 года родился необычайный человек, который оставил след в истории, имя которого написано в школьных учебниках. Этого человека до сих пор помнит вся Германия. Зовут его Мартин Лютер.

Отец его был очень трудолюбивый, не боялся работы, стремился к лучшей жизни. Родился Мартин в Германии, но после семья переехала в Айслебен. Как и все дети в 7 лет он пошёл в школу, где постоянно выслушивал унижения. Мартину денег не хватало, чтобы получить знания нужно было переводиться в другие школы. Он пел песни на улицах, пытаясь как-то заработать. В 15 лет он случайно встретил жену богача. Женщина была добродушной, поэтому впустила Мартина в свой дом.

В 18 лет он поступил в Эрфуртский университет, где поражал всех своей великолепной памятью. Мартин развивался в разных направлениях, но больше всего ему было интересно богословие. Прочитав библию, его жизнь полностью поменялась. Случилось то, чего никто не ожидал. Лютер пошёл служить Богу. Он достиг больших успехов и вскоре смог преподавать богословие. Чтобы переводить Библию Лютер стал изучать иностранные языки. Даже когда он служил Богу, Мартин не чувствовал себя чистым.

Лютер стал первым, кто осмелился пойти против церкви. Он считал, что люди не должны зависеть от духовенства. Поступок, который люди считали смелым был то, что Лютер сжёг папскую буллу. 26 мая 1521 года Мартина обвинили в ереси. После он стал заниматься переводом Библии на немецкий. Люди приняли мнение Лютера, но после появился кальвинизм. Жан Кальвин считал, что судьбу человека определяет Бог.

У Мартина была личная жизнь. Он говорил: “ Бог не может запрещать жить в любви…”. Женой Лютера стала монашка. Во время свадьбы Лютеру было 42 года, а его жене 26 лет. В их семье появилось на свет 6 детей. Жили просто, но если люди нуждались в помощи, то всегда им помогали.

Лютер является реформатором. В борьбе с папами Лютер сделал многое для своего народа. Даже сейчас немцы вспоминают Мартина. Ведь он является одним из самых великих немцев. Таким образом появилось одно из направлений протестантизма — лютеранство.

Доклад №2

В конце эпохи Средневековья в странах Западной Европы католическая церковь начала терять свое влияние. Появились отдельные реформистские церкви, которые не подчинялись Папе Римскому. Все это вылилось в грандиознейший со времен отделения православия церковный раскол, а также религиозные войны. Англиканство, кальвинизм, анабаптизм, цвинглианство и лютеранство навсегда раскололи христианство. Инициатором этой Реформации являлся простой немецкий богослов Мартин Лютер.

Мартин Лютер не был благородного происхождения. Он родился 10 ноября 1483-го года в Айслебене, в семье крестьянина Ганса Лютера, который работал на медных рудниках и лишь к концу жизни сумел скопить небольшое состояние, позволившее стать ему зажиточным бюргером. Мама его, Маргарита Лютер, была также выходцем из крестьянок. Оба родителя происходили из Саксонии.

Родители Мартина с ранних лет прививали своим детям любовь к богу, воспитывали их строго и нравственно. Еще в возрасте 14-ти лет его отправили в францисканскую школу, что находилась в Магдебурге. Там он смог получить хорошее образование, что позволило ему в 18 лет поступить в Эрфуртский университет. Там он изучал свободные искусства и юриспруденцию. Все прочили ему хорошую карьеру, однако, неожиданно для всех, в том числе и для его семьи, Мартин Лютер поступает в монастырь августинцев в том же Эрфурте. Там он в 1506-ом году становится монахом, а позже, священником.

Молодое дарование быстро оценили церковные иерархи и 25 летнего священника отправили читать лекции в университет Виттенберга. Там, в университетской библиотеке, он совершенствует свое образование, а также знакомится с трудами блаженного Августина, которые изменили его мировоззрение. Много работая, он получает степень доктора теологии.

Постепенно Мартин Лютер начинает задумываться о благочестии католического духовенства и вообще о римской церкви в целом. Во время служебной поездки в Рим, он увидел развращенность священников, их жадность и жажду власти. Возвратившись, он с усердием начинает изучать Библию, ища в ней ответы на свои вопросы. Каплей, переполнявшей чашу его терпения, стал знаменитый указ папы Льва Х, разрешающий продажу индульгенций и отпущения грехов. Лютер стал открыто критиковать церковь.

По вопросам церковных индульгенций Мартин Лютер пишет обширную статью, состоящую из знаменитых 95 тезисов в 1517-ом году. В ней он критикует католицизм сомневается в праве папы римского отпускать грехи, делает вывод о том, что господствующая церковь на корню губит веру. Свои тезисы Мартин Лютер прибивает к церковным дверям в Виттенберге. Именно эти тезисы и считаются началом церковного раскола, Реформации и зарождением протестантизма.

После такого открытого выступления против господствующей церкви, Мартина Лютера вызывали на церковный суд, а, впоследствии, предали анафеме. Однако папский документ, отлучающий его от церкви, он сжигает. В 1521-ом году Мартина Лютера публично провозглашают еретиком. Его похищает курфюрст Саксонии Фридрих и тайно помещает в свой замок, где Лютер приступает к главному делу своей жизни, переводе библии на немецкий язык. А ведь согласно католицизму, библия должна быть только на латыни. Именно богослужения на национальных языках, а не латинском, и есть основное отличие протестантских течений от католицизма.

В отличии от Яна Гуса, другого проповедника-реформатора, жившего столетием ранее, Мартина Лютера не сожгли на костре и не замуровали в монастырской келье. Он вел свободную жизнь, проповедуя и работая над новыми писаниями и катехизисами. Он даже женился в возрасте 42 лет и воспитывал 6 детей. И умер своей смертью в 1546-ом году в родном Айслебене.

7 класс кратко

Лютер Мартин

Популярные темы сообщений

- Пума (место обитания, чем питаются)

Пума одно из самых красивых и сильных представителей семейства кошачьих. Их еще называют горными львами или кугуарами. Это довольно крупное животное. В длину пума может достичь до двух метров, а высота достигает одного метра.

- Мировой океан

Самую большую часть всей гидросферы отводят мировому океану. Если брать весь мировой океан в целом, то его можно разделить на 4 океана. Он включает в себя воды Индийского, Тихого, Северного Ледовитого и Атлантического океанов.

- Голубь

Голубь – птица, знакомая каждому. Выйдя на улицу, мы обязательно увидим голубя, который греется на солнышке, летит или пьёт воду из лужи. Их называют «птица мира», они являются символом чистоты и невинности души.

- Равнокрылые насекомые

От равнокрылых насекомых не большая польза для человека. Они способны уничтожать сельскохозяйственные культуры и переносить разнообразные, порой даже смертельные болезни. Насчитывается 30 тыс. видов данных насекомых.

- Свойства воды

Вода – это жизнь. Где нет воды, там нет жизни. Например, в пустыне нет воды, и там почти не растут растения и не живут животные. Караваны в пустынях не смогли бы выжить там без воды. Выходит, она играет очень важную роль в нашей жизни.

|

The Reverend Martin Luther OSA |

|

|---|---|

Martin Luther (1529) by Lucas Cranach the Elder |

|

| Born | 10 November 1483

Eisleben, County of Mansfeld, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 18 February 1546 (aged 62)

Eisleben, County of Mansfeld, Holy Roman Empire |

| Education | University of Erfurt University of Wittenberg |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work | Ninety-five Theses (1517) |

| Spouse |

Katharina von Bora (m. 1525) |

| Children |

|

| Theological work | |

| Era | Renaissance |

| Tradition or movement | Lutheranism (Protestantism) |

| Main interests | Prolegomena |

| Notable ideas | Reformation Five solae (Sola fide) Law and Gospel Theology of the Cross Two kingdoms doctrine |

| Signature | |

Martin Luther OSA (;[1] German: [ˈmaʁtiːn ˈlʊtɐ] (listen); 10 November 1483[2] – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and Augustinian friar.[3] He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation who gave his name to Lutheranism.

Luther was ordained to the priesthood in 1507. He came to reject several teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church; in particular, he disputed the view on indulgences. Luther proposed an academic discussion of the practice and efficacy of indulgences in his Ninety-five Theses of 1517. His refusal to renounce all of his writings at the demand of Pope Leo X in 1520 and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521 resulted in his excommunication by the pope and condemnation as an outlaw by the Holy Roman Emperor.

Luther taught that salvation and, consequently, eternal life are not earned by good deeds but are received only as the free gift of God’s grace through the believer’s faith in Jesus Christ as redeemer from sin. His theology challenged the authority and office of the pope by teaching that the Bible is the only source of divinely revealed knowledge,[4] and opposed sacerdotalism by considering all baptized Christians to be a holy priesthood.[5] Those who identify with these, and all of Luther’s wider teachings, are called Lutherans, though Luther insisted on Christian or Evangelical (German: evangelisch) as the only acceptable names for individuals who professed Christ.

His translation of the Bible into the German vernacular (instead of Latin) made it more accessible to the laity, an event that had a tremendous impact on both the church and German culture. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language, added several principles to the art of translation,[6] and influenced the writing of an English translation, the Tyndale Bible.[7] His hymns influenced the development of singing in Protestant churches.[8] His marriage to Katharina von Bora, a former nun, set a model for the practice of clerical marriage, allowing Protestant clergy to marry.[9]

In two of his later works, Luther expressed antisemitic views, calling for the expulsion of Jews and burning of synagogues.[10] In addition, these works also targeted Roman Catholics, Anabaptists, and nontrinitarian Christians.[11] Based upon his significant anti-judaistic teachings,[12][13][14] the prevailing view among historians is that his rhetoric contributed significantly to the development of antisemitism in Germany and of the Nazi Party.[15][16][17] Luther died in 1546 with Pope Leo X’s excommunication still in effect.

Early life

Birth and education

Martin Luther was born to Hans Luder (or Ludher, later Luther)[18] and his wife Margarethe (née Lindemann) on 10 November 1483 in Eisleben, County of Mansfeld, in the Holy Roman Empire. Luther was baptized the next morning on the feast day of St. Martin of Tours. In 1484, his family moved to Mansfeld, where his father was a leaseholder of copper mines and smelters[19] and served as one of four citizen representatives on the local council; in 1492 he was elected as a town councilor.[20][18] The religious scholar Martin Marty describes Luther’s mother as a hard-working woman of «trading-class stock and middling means», contrary to Luther’s enemies, who labeled her a whore and bath attendant.[18]

He had several brothers and sisters and is known to have been close to one of them, Jacob.[21]

Hans Luther was ambitious for himself and his family, and he was determined to see Martin, his eldest son, become a lawyer. He sent Martin to Latin schools in Mansfeld, then Magdeburg in 1497, where he attended a school operated by a lay group called the Brethren of the Common Life, and Eisenach in 1498.[22] The three schools focused on the so-called «trivium»: grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Luther later compared his education there to purgatory and hell.[23]

In 1501, at age 17, he entered the University of Erfurt, which he later described as a beerhouse and whorehouse.[24] He was made to wake at four every morning for what has been described as «a day of rote learning and often wearying spiritual exercises.»[24] He received his master’s degree in 1505.[25]

Luther as a friar, with tonsure

Luther’s accommodation in Wittenberg

In accordance with his father’s wishes, he enrolled in law but dropped out almost immediately, believing that law represented uncertainty.[25] Luther sought assurances about life and was drawn to theology and philosophy, expressing particular interest in Aristotle, William of Ockham, and Gabriel Biel.[25] He was deeply influenced by two tutors, Bartholomaeus Arnoldi von Usingen and Jodocus Trutfetter, who taught him to be suspicious of even the greatest thinkers[25] and to test everything himself by experience.[26]

Philosophy proved to be unsatisfying, offering assurance about the use of reason but none about loving God, which to Luther was more important. Reason could not lead men to God, he felt, and he thereafter developed a love-hate relationship with Aristotle over the latter’s emphasis on reason.[26] For Luther, reason could be used to question men and institutions, but not God. Human beings could learn about God only through divine revelation, he believed, and Scripture therefore became increasingly important to him.[26]

On 2 July 1505, while Luther was returning to university on horseback after a trip home, a lightning bolt struck near him during a thunderstorm. Later telling his father he was terrified of death and divine judgment, he cried out, «Help! Saint Anna, I will become a monk!»[27][28] He came to view his cry for help as a vow he could never break. He left university, sold his books, and entered St. Augustine’s Monastery in Erfurt on 17 July 1505.[29] One friend blamed the decision on Luther’s sadness over the deaths of two friends. Luther himself seemed saddened by the move. Those who attended a farewell supper walked him to the door of the Black Cloister. «This day you see me, and then, not ever again,» he said.[26] His father was furious over what he saw as a waste of Luther’s education.[30]

Monastic life

A posthumous portrait of Luther as an Augustinian friar

Luther dedicated himself to the Augustinian order, devoting himself to fasting, long hours in prayer, pilgrimage, and frequent confession.[31] Luther described this period of his life as one of deep spiritual despair. He said, «I lost touch with Christ the Savior and Comforter, and made of him the jailer and hangman of my poor soul.»[32]

Johann von Staupitz, his superior, concluded that Luther needed more work to distract him from excessive introspection and ordered him to pursue an academic career. On 3 April 1507, Jerome Schultz (lat. Hieronymus Scultetus), the Bishop of Brandenburg, ordained Luther in Erfurt Cathedral. In 1508, he began teaching theology at the University of Wittenberg.[33] He received a bachelor’s degree in biblical studies on 9 March 1508 and another bachelor’s degree in the Sentences by Peter Lombard in 1509.[34] On 19 October 1512, he was awarded his Doctor of Theology and, on 21 October 1512, was received into the senate of the theological faculty of the University of Wittenberg,[35] having succeeded von Staupitz as chair of theology.[36] He spent the rest of his career in this position at the University of Wittenberg.

He was made provincial vicar of Saxony and Thuringia by his religious order in 1515. This meant he was to visit and oversee each of eleven monasteries in his province.[37]

Start of the Reformation

In 1516, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money in order to rebuild St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.[38] Tetzel’s experiences as a preacher of indulgences, especially between 1503 and 1510, led to his appointment as general commissioner by Albrecht von Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz, who, deeply in debt to pay for a large accumulation of benefices, had to contribute the considerable sum of ten thousand ducats[39] toward the rebuilding of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Albrecht obtained permission from Pope Leo X to conduct the sale of a special plenary indulgence (i.e., remission of the temporal punishment of sin), half of the proceeds of which Albrecht was to claim to pay the fees of his benefices.

On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to his bishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, protesting against the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his «Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences»,[a] which came to be known as the Ninety-five Theses. Hans Hillerbrand writes that Luther had no intention of confronting the church but saw his disputation as a scholarly objection to church practices, and the tone of the writing is accordingly «searching, rather than doctrinaire.»[41] Hillerbrand writes that there is nevertheless an undercurrent of challenge in several of the theses, particularly in Thesis 86, which asks: «Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?»[41]

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel that «As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory (also attested as ‘into heaven’) springs.»[42] He insisted that, since forgiveness was God’s alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following Christ on account of such false assurances.

According to one account, Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517. Scholars Walter Krämer, Götz Trenkler, Gerhard Ritter, and Gerhard Prause contend that the story of the posting on the door, although it has become one of the pillars of history, has little foundation in truth.[43][44][45][46] The story is based on comments made by Luther’s collaborator Philip Melanchthon, though it is thought that he was not in Wittenberg at the time.[47] According to Roland Bainton, on the other hand, it is true.[48]

The Latin Theses were printed in several locations in Germany in 1517. In January 1518 friends of Luther translated the Ninety-five Theses from Latin into German.[49] Within two weeks, copies of the theses had spread throughout Germany. Luther’s writings circulated widely, reaching France, England, and Italy as early as 1519. Students thronged to Wittenberg to hear Luther speak. He published a short commentary on Galatians and his Work on the Psalms. This early part of Luther’s career was one of his most creative and productive.[50] Three of his best-known works were published in 1520: To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and On the Freedom of a Christian.

Justification by faith alone

Luther at Erfurt, which depicts Martin Luther discovering the doctrine of sola fide (by faith alone). Painting by Joseph Noel Paton, 1861.

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, and on the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as penance and righteousness by the Catholic Church in new ways. He became convinced that the church was corrupt in its ways and had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity. The most important for Luther was the doctrine of justification—God’s act of declaring a sinner righteous—by faith alone through God’s grace. He began to teach that salvation or redemption is a gift of God’s grace, attainable only through faith in Jesus as the Messiah.[51] «This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification», he writes, «is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness.»[52]