К типу Плоских червей относятся более (25) тысяч видов.

Плоские черви имеют двустороннюю (билатеральную) симметрию.

Рис. (1). Двусторонняя симметрия

Тело Плоских червей формируется из трёх слоёв клеток: эктодермы, энтодермы и мезодермы (т. е. они трёхслойные животные). У них впервые появляется третий слой клеток — мезодерма.

Мезодерма — средний слой клеток, который залегает между эктодермой и энтодермой.

Рис. (2). Слои клеток

Внутреннее строение плоских червей

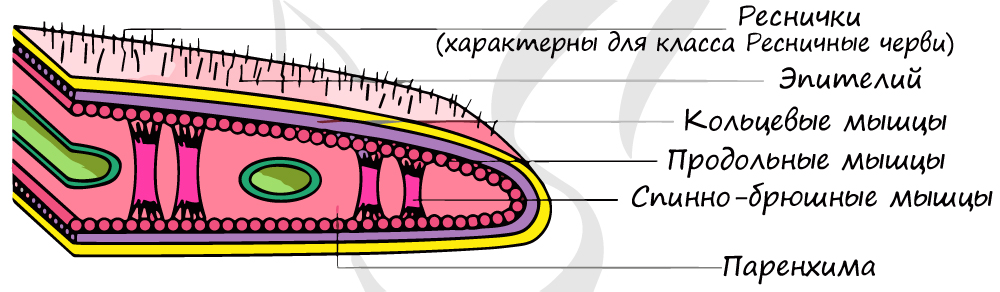

Само тело представляет собой кожно-мускульный мешок, который состоит из покровного эпителия и трёх слоёв мышц — кольцевых, косых и продольных. Кожно-мускульный мешок позволяет животному сохранять постоянную форму тела.

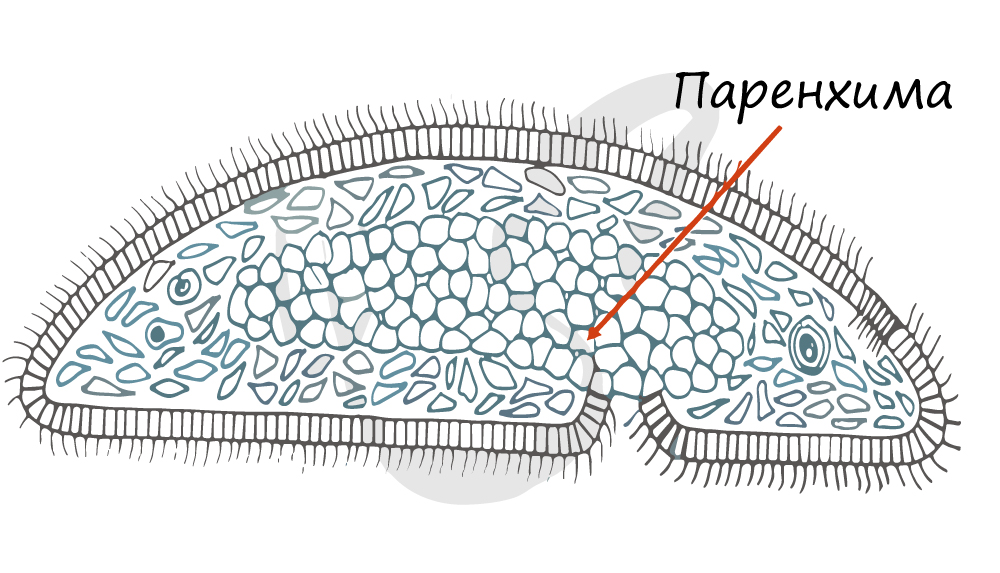

Под кожно-мускульным мешком расположены внутренние органы, пространство между которыми заполнено паренхимой. Внутренней полости тела у плоских червей нет!

Паренхима — группа клеток, имеющих отростки, которая заполняет пространство между органами.

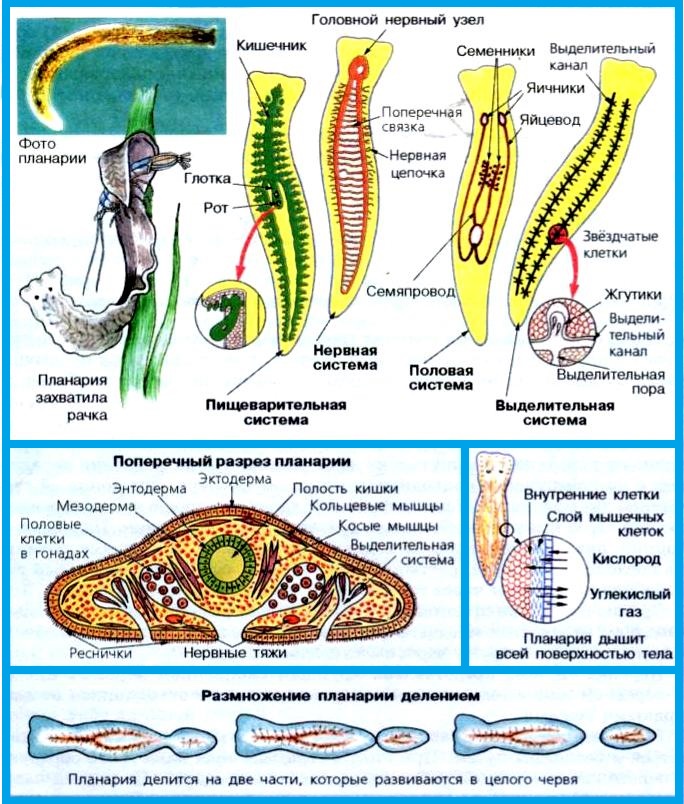

Рис. (3). Строение тела планарии

Тело свободноживущих червей сверху покрыто ресничками, обеспечивающих передвижение червя (у паразитических червей ресничек нет).

У представителей типа имеются системы органов: пищеварительная, выделительная, нервная и репродуктивная(половая).

Рис. (4). Системы органов плоских червей

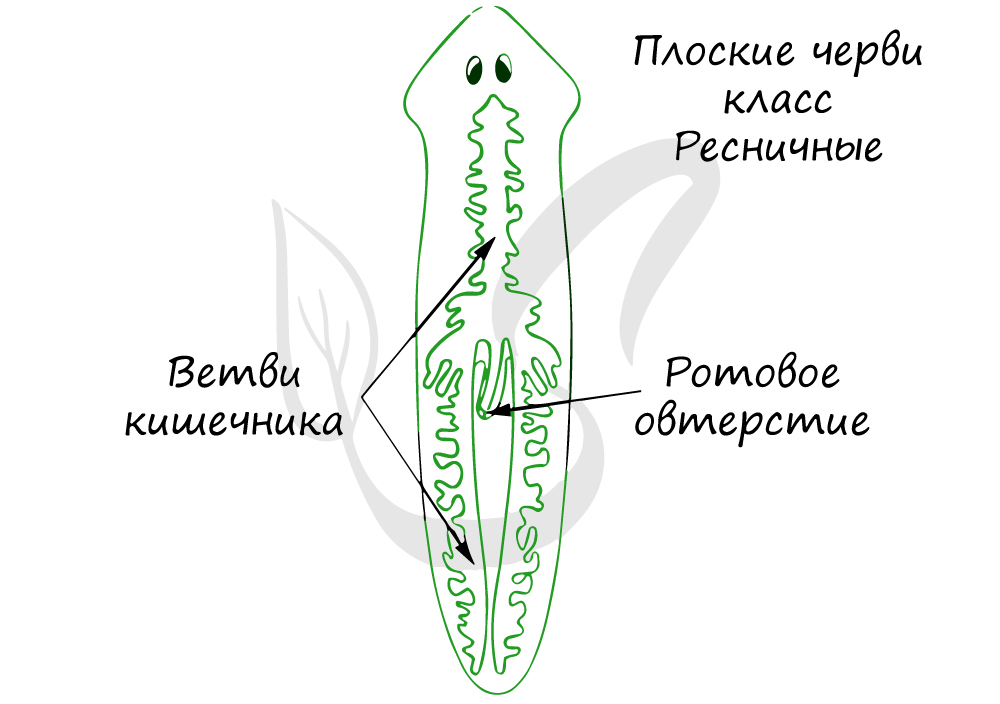

Пищеварительная система примитивная, начинается ртом, расположенным посредине тела на брюшной стороне. Далее идут глотка и кишечник, который слепо заканчивается (анального отверстия нет). Непереваренные остатки пищи выводятся наружу через рот.

Рис. (5). Пищеварительная система планарии

Выделительная система

Выделительная система представлена протонефридиями, состоящими из канальцев, начинающихся звёздчатыми клетками с пучками ресничек. Пучки ресничек, колеблясь, создают ток жидкости и направляют её к выделительной поре.

Протонефридии — система канальцев, которые пронизывают всё тело животного и открываются снаружи порами.

Рис. (6). Выделительная система

Нервная система

Нервная система состоит из нервных узлов (ганглиев) на передней части тела и нервных стволов, расположенных вдоль тела. Нервные стволы соединены между собой поперечными перемычками. Такой тип нервной системы называют лестничным.

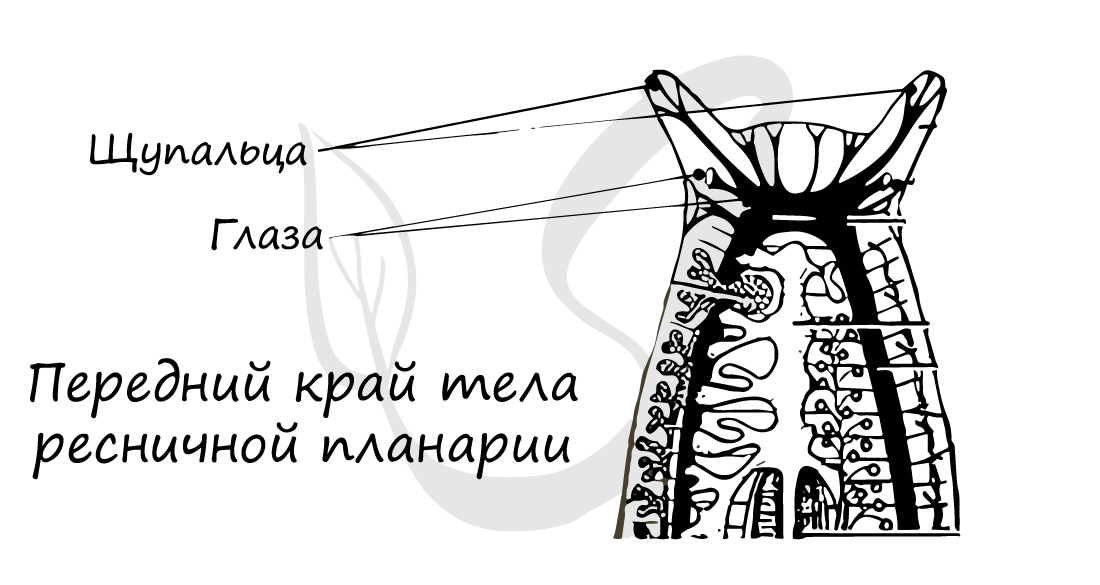

Некоторые плоские черви (свободноживущие) имеют примитивные органы чувств — глаза и статоцисты (органы равновесия).

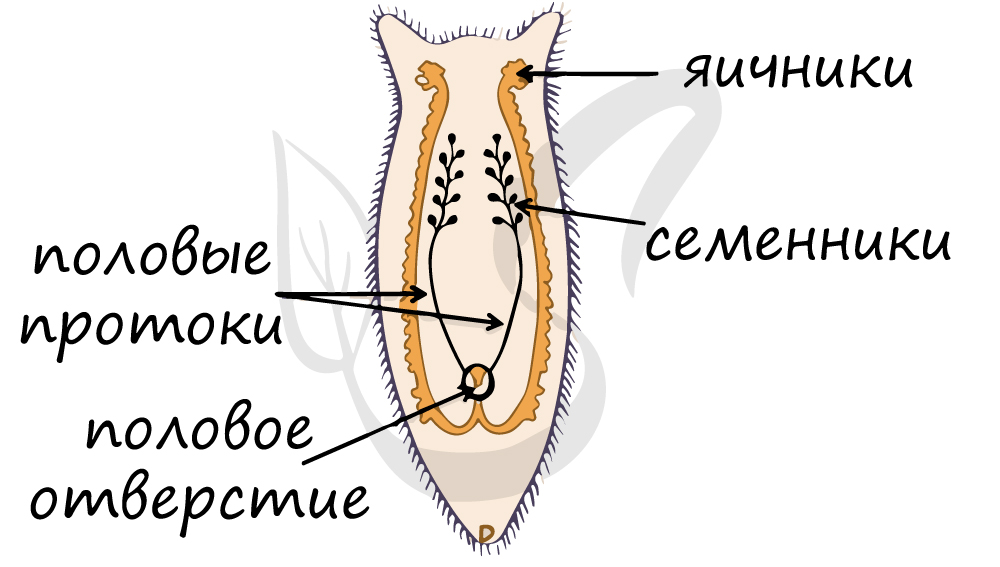

В теле каждого плоского червя есть и мужские, и женские половые органы, т. е. они гермафродиты. Имеются мужские половые железы — семенники и женские — яичники.

В паренхиме расположены многочисленные пузырьки — семенники. От них идут трубчатые семяпроводы, по которым мужские гаметы (сперматозоиды) поступают с к совокупительному органу. Семенники, семяпроводы и совокупительный орган составляют мужскую половую систему.

Женскую половую систему образуют парные яичники и яйцеводы, которые впадают в совокупительную сумку.

Гермафродиты — организмы, которые одновременно имеют как мужские, так и женские половые органы.

Внутреннее оплодотворение — тип оплодотворения, при котором слияние яйцеклетки и сперматозоида происходит внутри женского организма.

Перекрёстное оплодотворение — оплодотворение, при котором яйцеклетка оплодотворяется сперматозоидом другой особи.

Самооплодотворение — оплодотворение, при котором яйцеклетка оплодотворяется сперматозоидом той же особи.

Дыхательная и кровеносная системы

Дыхательная и кровеносная системы отсутствуют. Поглощение кислорода и выделение углекислого газа осуществляется всей поверхностью тела. С целью транспорта питательных веществ к тканям используются многочисленные выросты кишечника.

Плоские черви живут в сырой почве, в водоёмах, могут паразитировать в других организмах.

Гельминты (паразитические черви) вызывают опасные заболевания животных и человека. Эти паразиты приводят к сильным болям, истощению, малокровию. Например, возбудителем болезни описторхоза является кошачья двуустка, которая паразитирует в печени и желчных протоках, желчном пузыре. Этим червём заражаются при употреблении в пищу замороженной карповой рыбы.

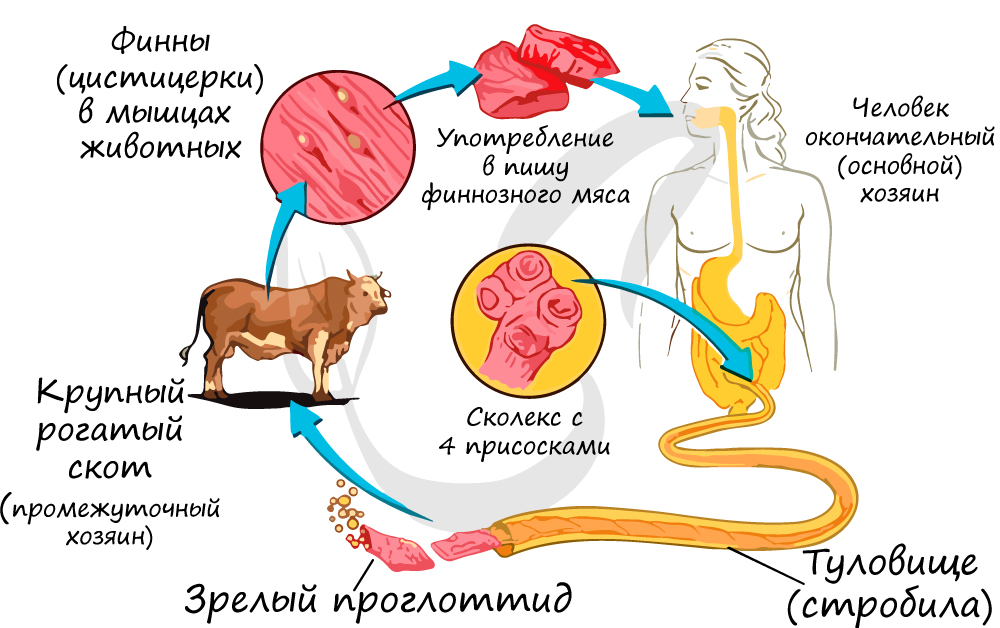

Человек заражается свиным цепнем, употребляя в пищу заражённую свинину, а бычьим цепнем — при употреблении заражённой говядины. Поэтому нельзя употреблять в пищу мясо, которое не прошло санитарный контроль.

Гельминты — паразитические черви.

Гельминтозы — заболевания, вызванные паразитическими червями.

Источники:

Рис. 1. Двусторонняя симметрия. © ЯКласс.

Рис. 2. Слои клеток. © ЯКласс.

Рис. 3. Строение тела планарии. © ЯКласс.

Рис. 4. Системы органов плоских червей. https://image.shutterstock.com/image-illustration/plathelmints-morphology-internal-anatomy-reproduction-600w-2019367178.

Рис. 5. Пищеварительная система планарии. © ЯКласс.

Рис. 6. Выделительная система. © Якласс.

Тип ПЛОСКИЕ ЧЕРВИ

Плоские черви — двусторонне-симметричные животные. Часть из них — свободноживущие хищники, обитающие в морях и пресных водоемах, другие — паразиты позвоночных животных и человека, вызывающие различные заболевания. Размеры тела червей — от долей миллиметра до 10 м. Их тело удлиненное, вытянутое, сплюснутое в спинно-брюшном направлении. Тип включает три класса: Ресничные, Сосальщики и Ленточные.

Характерные черты типа Плоские черви

1. Тело плоское, его форма листовидная (у ресничных и сосальщиков) или лентовидная (у ленточных червей).

2. Двусторонняя симметрия тела, делящая тело на две зеркально подобные части.

3. Кроме эктодермы и энтодермы они имеют еще средний зародышевый листок — мезодерму (трехслойные животные).

4. Стенку тела образует колено-мускульный мешок. Тело плоских червей способно совершать сложные и разнообразные движения.

5. Пространство между стенкой тела и внутренними органами заполнено соединительной тканью (паренхимой). Она выполняет опорную функцию и служит в качестве депо запасных питательных веществ.

6. Пищеварительная система состоит из двух отделов: 1) эктодермальной передней кишки, представленной ртом и мускулистой глоткой, способной у хищных ресничных червей выворачиваться наружу, проникать внутрь жертвы и высасывать ее содержимое, 2) слепо замкнутой энтодермальной средней кишки. Непереваренные остатки нищи выбрасываются через рот.

7. Выделительная система протонефридиального типа (с помощью протонефридиев жидкость из паренхимы направляется в каналы, открывающиеся выделительными порами наружу). Через выделительные поры выводится избыток воды и конечные продукты метаболизма (преимущественно мочевина).

8. Нервная система более концентрирована и представлена парным головным ганглием и отходящими от него продольными нервными стволами, соединенными кольцевыми перемычками. Такой тип организации нервной системы называется стволовым.

9. У всех плоских червей развиты органы осязания, химического чувства, равновесия, а у свободноживущих — и зрения.

10. Плоские черви — гермафродиты (за редким исключением). Оплодотворение внутреннее, перекрестное. Кроме половых желез (яичников и семенников), развита сложная система половых протоков, дополнительных желез. У пресноводных ресничных червей развитие прямое, у морских — с планктонной личиночной стадией. У паразитических червей (сосальщиков и ленточных червей) циклы развития сложные с наличием одной или нескольких личиночных стадий и сменой нескольких хозяев.

Класс Ресничные черви

общая характеристика на примере белой планарии

В классе Ресничные черви около 3000 видов, обитающих в морях, пресных водах, во влажных тропических лесах. Покровы тела червей окрашены в разные цвета — зелёный, жёлтый, розовый, коричневый, чёрный, красный, фиолетовый, серый. Размеры тела тоже разные — от долей миллиметра до 0,5 м. В небольших пресных водоёмах живёт мелкая (длиной 1-2 см) белая планария. Тело планарии как представителя ресничных червей покрыто ресничками, которые крепятся в клетках эпителия, расположенных в один слой. На примере этого животного можно рассмотреть строение ресничных червей.

Опорно-двигательная система. Под эпителием у планарии находится несколько слоёв мышц (мускулатуры). Эпителиальный слой и мышцы вместе образуют кожно-мускульный мешок, который позволяет сохранять постоянную форму тела (рис. 48). В теле планарии кожно-мускульным мешком представлена опорно–двигательная система. Благодаря согласованным движениям ресничек животное плавно скользит по дну водоёма. Крупные черви передвигаются за счёт ресничек и сокращений мускулатуры Свободное пространство под кожно-мускульным мешком за полнено рыхлой соединительной тканью — паренхимой. Она, как и мышцы, образуется из мезодермы. В паренхиме лежат внутренние органы животного.

У плоских червей, в отличие от кишечнополостных, имеется несколько видов тканей — эпителиальная (покровная), мышечная, соединительная и нервная. Из тканей состоят органы, образующие системы органов — опорно-двигательную, пищеварительную, выделительную, нервную и половую. Кровеносная и дыхательная системы отсутствуют.

Пищеварительная система. Органы, участвующие в захвате пищи, её передвижении и переваривании, формируют пищеварительную систему. У планарии она состоит из рта, глотки и кишечника. Глотка у планарии — это орган захвата пищи, а кишечник — орган переваривания. Глотка образована эктодермой, а кишечник — энтодермой. Рот расположен на брюшной стороне тела. Планария — хищник. Она нападает на мелких животных, например рачков и червей. Планария прижимается к пойманной жертве, а затем с помощью выдвижной глотки заглатывает её.

Дыхание. Поглощение кислорода и удаление углекислого газа происходит через покровы тела. Плоская форма червя облегчает газообмен. Как и другие водные животные, планария дышит кислородом, растворённым в воде.

Нервная система. В отличие от кишечнополостных, у плоских червей нервные клетки не разбросаны по телу в виде сети, а собраны в нервные узлы и нервные стволы. У планарии пара нервных узлов расположена в головном конце, и от них отходят два продольных нервных ствола, соединённых поперечными перемычками. От нервных стволов ко всем органам идут нервы. У других видов плоских червей имеется более одной пары нервных узлов и стволов.

Хорошо развиты органы чувств. У поверхности тела расположены чувствительные клетки, воспринимающие механические воздействия. Если к телу червя прикоснуться, чувствительные клетки передадут по нервам сигнал в нервные узлы, которые по другим нервам пошлют сигнал к нужным мышцам, заставляя их работать. На переднем конце тела находятся особые органы осязания — парные щупальца, орган равновесия, а также парные глаза. С помощью глаз планария определяет степень освещённости.

Выделительная система. Органами выделения, образующими выделительную систему. у планарии служат разветвлённые трубочки, пронизывающие тело. Они сливаются в два продольных канала. Трубочки начинаются в паренхиме клетками, несущими пучок длинных ресничек. Реснички постоянно колеблются и создают ток жидкости, содержащей вредные продукты жизнедеятельности. Продольные каналы открываются наружу несколькими отверстиями на спинной стороне тела.

Размножение и развитие. Планария способна размножаться бесполым путём за счёт поперечного деления пополам. Из каждой половинки восстанавливается целая особь. Поскольку эти животные гермафродиты, в их теле имеются и мужские половые органы — семенники, и женские — яичники. В мужской половой систем от парных семенников отходят трубочки семяпроводов. По ним сперматозоиды продвигаются к совокупительному органу. Женская половая система состоит из парных яичников, от которых отходят трубочки яйцеводов.

Оплодотворение у планарий внутреннее. Две особи соприкасаются брюшными сторонами и обмениваются мужскими половыми клетками. Сперматозоиды достигают яичников и сливаются со зрелыми яйцеклетками. Зиготы движутся по яйцеводам, по пути зиготы превращаются в яйца, содержащие запас питательных веществ и покрытые оболочкой. Яйца, запакованные в кокон, выводятся наружу. Спустя несколько недель из них появляются маленькие черви.

Класс Сосальщики

Внешнее и внутреннее строение. Сосальщики — плоские черви, паразитирующие во внутренних органах других животных. Например, взрослые особи печёночного сосальщика обитают в жёлчных протоках овец, коз, крупного рогатого скота, буйволов, верблюдов, свиней, лошадей, зайцев, некоторых грызунов и человека. Сосальщики произошли, вероятно, от ресничных червей, и поэтому у них много общих черт с планариями. Так, у печёночного сосальщика листовидное тело длиной до 3 см, сильно сплющенное в спинно-брюшном направлении, постепенно сужающееся к заднему концу. Окраска червя серовато-желтоватая.

Паразитические плоские черви живут в бескислородной среде. Поэтому превращения сложных органических веществ в менее сложные идут без участия кислорода. В ходе этих превращений высвобождается необходимая организму энергия. В связи с паразитическим образом жизни у печёночного сосальщика появились две присоски — ротовая на переднем конце тела и брюшная на брюшной стороне. Присоски помогают малоподвижным сосальщикам удерживаться в жёлчных протоках.

В отличие от планарии у печёночного сосальщика нет эпителия с ресничками. Покровы его тела представлены многослойной плотной оболочкой — кутикулой, которая защищает паразита от воздействия пищеварительных соков животного хозяина.

Внутреннее строение сосальщика во многом такое же, как у планарии. Преобразования систем органов связаны с паразитическим образом жизни. Так, органы чувств у сосальщика развиты слабо и представлены в основном органами осязания, разбросанными в покровах тела. Рот находится на дне передней присоски, а не на нижней стороне тела, как у планарии. Кишечник сильно разветвлён. Питается сосальщик кровью и другими тканями своих хозяев, затягивая пищу сосательными движениями глотки.

Размножение и развитие. Сосальщики, как и планарии, являются гермафродитами. Обычно у сосальщиков, как и у планарий, происходит взаимное оплодотворение двух спаривающихся червей. Но если паразит живет один в организме хозяина, может происходить и самооплодотворение.

Жизненный цикл у печеночного сосальщика сложный: в нем происходит чередование поколений бесполого и полового, как у кишечнополостных. Паразит меняет хозяев: личинка, вылупившаяся из яйца, плавает в воде, потом проникает в тело улитки – малого прудовика, где дает новое поколение личинок, а они попадают в организм овцы, коровы или человека.

Яйца печёночного сосальщика попадают из жёлчных протоков хозяина-млекопитающего в его кишечник, а оттуда — во внешнюю среду. Если яйцо оказывается в воде, из него выходит покрытая ресничками личинка. Она плавает, потом проникает в тело малого прудовика. Здесь личинка превращается в бесформенный неподвижный мешок, в котором происходит бесполое размножение и формируется несколько поколений зародышей.

Личинки выходят из тела прудовика в воду, сначала активно плавают, а потом оседают в прибрежной растительности, отбрасывают хвостик, выделяют вокруг себя оболочку и превращаются в цисту. В такой стадии они сохраняют жизнеспособность длительное время, перенося неблагоприятные условия. Домашние животные, поедая прибрежную траву, заглатывают паразитов. В кишечнике циста растворяется, паразит через стенку кишечника попадает в кровь, а оттуда — в печень и в жёлчные протоки.

Человек может заразиться печёночным сосальщиком, если пьёт сырую воду из мелких водоёмов, берёт в рот травинки, сорванные в болотистых местах.

В организме млекопитающего печёночный сосальщик размножается половым путём, а в организме прудовика — бесполым путём. Организм, в теле которого происходит половое размножение паразита, называется окончательным хозяином, а организм, в теле которого половое размножение не происходит, называется промежуточным хозяином.

Класс Ленточные черви

Внешнее и внутреннее строение. Все ленточные черви — паразиты, обитающие в кишечнике животных и человека. Приспособления к паразитическому образу жизни у них более совершенны, чем у сосальщиков. К ленточным червям относится свиной цепень. Тело этого червя сильно вытянутое, лентовидное, состоит из многочисленных члеников и напоминает цепь, поэтому паразита и называют цепнем. Свиные цепни бывают длиной до 3 м. Окраска тела у них белая или желтоватая. На переднем конце тела имеется маленькая головка. На ней расположены четыре присоски и хоботок с двумя рядами крючьев. Крючьями и присосками паразит закрепляется в кишечнике животного-хозяина. Новые членики образуются только за головкой, там они небольшие, а удалённые от головки — более крупные. Членики на заднем конце тела периодически отрываются и с испражнениями хозяина попадают наружу.

Изменения в строении по сравнению с белой планарией у ленточных червей связаны с приспособлением к особенностям среды жизни. Как и у сосальщиков, тело их покрыто прочной кутикулой. Опорно-двигательная система представлена кожно-мускульным мешком, пространство между внутренними органами заполнено паренхимой. Сходно с сосальщиками и строение выделительной системы. Для дыхания ленточные черви не используют кислород. Нервная система развита слабо, органы чувств отсутствуют.

В отличие от сосальщиков, пищеварительная система у цепня полностью отсутствует, и пища всасывается всей поверхностью тела через покровы.

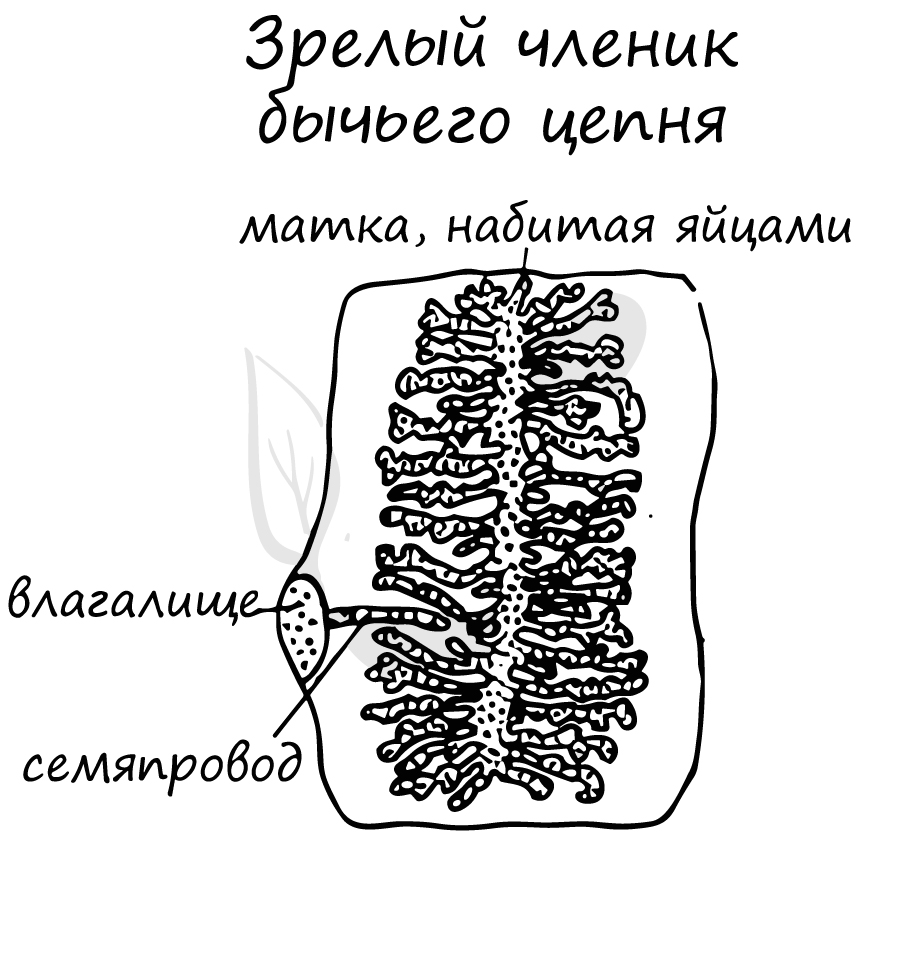

Размножение и развитие. У свиного цепня в каждом членике имеются женская и мужская половые системы: этот червь — гермафродит. Обычно сначала развиваются органы мужской половой системы, а затем — женской. При оплодотворении членики разных особей соприкасаются друг с другом, но может происходить и самооплодотворение.

После оплодотворения мужская половая система постепенно исчезает, а весь членик наполняется яйцами. Членики со зрелыми яйцами отрываются и выводятся из организма хозяина наружу с испражнениями. Один червь может продуцировать огромное число яиц — до сотен миллионов 1 год. Живут цепни несколько лет.

Окончательный хозяин свиного цепня — человек, а промежуточный хозяин — свинья.

Свиньи заражаются цепнем, поедая нечистоты и заглатывая яйца паразита. В кишечнике свиньи оболочка яиц разрушается, из них выходят личинки, похожие на маленький шарик с шестью крючьями. С их помощью личинка вбуравливается в стенки желудка или кишки, проникает в кровь, а оттуда в печень, сердце, лёгкие, мозг, мышцы.

В этих органах личинка превращается в следующую личиночную стадию – финну. Финна растет и становится размером с крупную горошину. Её тело напоминает пузырь, наполненный жидкостью. Для продолжения развития финна должна попасть в организм человека. Это случается, когда человек употребляет в пищу непроваренную, непрожаренную или непросоленную свинину, содержащую паразита.

Печёночный сосальщик и свиной цепень чрезвычайно плодовиты, что связано с паразитическим образом жизни. Вероятность попасть в организм окончательного хозяина очень невелика, поэтому для выживания паразиты вынуждены производить огромное число потомков. Этому же способствует и бесполое размножение в организме промежуточного хозяина.

Сравнительная характеристика классов

у типа Плоские черви (таблица)

Сравнительная характеристика классов у типа Плоские черви (таблица)

Конспект урока «Тип Плоские черви«. Следующая тема: Тип Круглые черви

Плоские черви (Platyhelminthes) представляют собой группу двусторонние симметричных беспозвоночных животных с мягким телом, встречающихся в морской, пресноводной, а также влажной наземной среде. Некоторые виды плоских червей являются свободноживущими, но около 80% всех плоских червей являются паразитическими, то есть живут на или в другом организме и получают от него питание.

Происхождение вида и описание

Фото: Плоский червь

Происхождение плоских червей и эволюция различных классов остаются неясными. Однако есть два основных направления. Согласно более общепринятому мнению, турбеллярии представляют предков всех других животных с тремя слоями ткани. Однако другие согласились, что плоские черви могут быть вторично упрощены, то есть они могли выродиться из более сложных животных в результате эволюционной потери или уменьшения сложности.

Интересный факт: Продолжительность жизни плоского червя неопределенная, но в неволе представители одного вида жили от 65 до 140 дней.

Плоские черви подпадают под царство животных, которое характеризуется многоклеточными эукариотическими организмами. В некоторых классификациях они также классифицируются как базовая группа животных эуметазои, так как они являются метазоями, которые подпадают под царство животных.

Видео: Плоские черви

Плоские черви также подпадают под двусторонне-симетричные среди эуметазоев. Эта классификация включает животных с двусторонней симметрией, состоящей из головы и хвоста (а также дорсальной части и живота). Как члены подвида протосом, плоские черви состоят из трех зародышевых слоев. Как таковые, они также часто упоминаются как протостомы.

Помимо этих более высоких классификаций, тип делится на следующие классы:

- ресничные черви;

- моногенеи;

- цестоды;

- трематоды.

Класс ресничные черви состоит из около 3000 видов организмов, распространенных по крайней мере в 10 отрядах. Класс моногенеи, хотя и сгруппированы в другом классе с трематодами, имеют с ними много сходных черт.

Однако их легко отличить от трематод и цестод по тому факту, что они обладают задним органом, известным как хаптор. Моногенеи различаются по размеру и форме. Например, в то время как более крупные виды могут выглядеть сплюснутыми и иметь форму листа (в форме листа), более мелкие виды более цилиндрические.

Класс цестода состоит из более чем 4000 видов, широко известных как ленточные черви. По сравнению с другими типами плоских червей цестоды характеризуются своими длинными плоскими телами, которые могут вырастать до 18 метров в длину и состоять из множества репродуктивных единиц (проглоттид). Все члены класса трематода паразитируют по своей природе. В настоящее время выявлено около 20 000 видов класса трематода.

Внешний вид и особенности

Фото: Как выглядит плоский червь

Признаки представителей ресничных червей следующие:

- корпус имеет коническую форму на обоих концах с уменьшенной толщиной по сравнению с центральной частью корпуса;

- со сжатым дорсо-вентральным разрезом тела ресничные черви имеют высокое отношение площади поверхности к объему;

- передвижение достигается с помощью хорошо скоординированных ресничек, которые многократно колеблются в одном направлении;

- они не сегментированы;

- у ресничных червей отсутствует целом (полость тела, расположенная между стенкой тела и кишечным каналом у большинства животных);

- у них субэпидермальные рабдиты в ресничном эпидермисе, которые отличают этот класс от других плоских червей;

- им не хватает анального отверстия. В результате пищевой материал всасывается через глотку и выбрасывается через рот;

- в то время как большинство видов в этом классе являются хищниками мелких беспозвоночных, другие живут как травоядные, падальщики и эктопаразиты;

- пигментные клетки и фоторецепторы, присутствующие в их точках зрения, используются вместо формирующих изображение глаз;

- в зависимости от вида, периферическая нервная система ресничных червей варьируется от очень простых до сложных переплетенных нервных сетей, которые контролируют движение мышц.

Некоторые из характеристик моногенеев включают в себя такие:

- все представители класса моногенеи являются гермафродитами;

- у моногенеев нет промежуточных хозяев в их жизненном цикле;

- хотя у них есть определенные формы тела в зависимости от вида, было показано, что они способны удлинять и укорачивать свои тела, когда они движутся в окружающей среде;

- они не имеют анального отверстия и поэтому используют протонефридиальную систему для выведения отходов;

- у них нет дыхательной и кровеносной системы, но есть нервная система, состоящая из нервного кольца и нервов, которые распространяются на заднюю и переднюю части тела;

- как паразиты, моногенеи часто питаются клетками кожи, слизью, а также кровью хозяина, что вызывает повреждение слизистой оболочки и кожи, защищающей животное (рыбу).

Характеристики класса цестода:

- сложный жизненный цикл;

- у них нет пищеварительной системы. Вместо этого поверхность их тел покрыта маленькими микроворсиноподобными выступами, подобными тем, которые обнаруживаются в тонкой кишке многих позвоночных;

- через эти структуры ленточные черви эффективно поглощают питательные вещества через внешнее покрытие (тегмент);

- у них хорошо развитые мышцы;

- модифицированные реснички на их поверхности используются в качестве сенсорных окончаний;

- нервная система состоит из пары боковых нервных связок.

Характеристики трематод:

- у них есть ротовые присоски, а также вентральные присоски, которые позволяют организмам прикрепляться к хозяину. Это облегчает кормление организмов;

- взрослые особи могут быть обнаружены в печени или кровеносной системе хозяина;

- у них хорошо развитый пищеварительный тракт и выделительная система;

- у них хорошо развита мышечная система.

Где обитают плоские черви?

Фото: Плоские черви в воде

В общем, свободно живущие плоские черви (турбеллярии) могут встречаться везде, где есть влага. За исключением темноцефалидов, плоские черви являются космополитическими по распространению. Они встречаются как в пресной, так и в соленой воде, а иногда и во влажных земных местах обитания, особенно в тропических и субтропических регионах. Темноцефалиды, которые паразитируют на пресноводных ракообразных, встречаются главным образом в Центральной и Южной Америке, на Мадагаскаре, в Новой Зеландии, Австралии и на островах южной части Тихого океана.

В то время как большинство видов плоских червей обитают в морской среде, есть много других, которые можно найти в пресноводных средах, а также в тропической наземной и влажной умеренной среде. Таким образом, они требуют, по крайней мере, влажных условий, чтобы выжить.

В зависимости от вида представители класса ресничных червей существуют либо как свободноживущие организмы, либо как паразиты. Например, представители отряда темноцифалиды существуют как полностью комменсалы или паразиты.

Интересный факт: Некоторые виды плоских червей занимают очень широкий круг мест обитания. Один из самых космополитических и наиболее терпимых к различным экологическим условиям – турбеллярный Gyratrix hermaphroditus, который встречается в пресной воде на высоте от уровня моря до 2000 метров, а также в бассейнах с морской водой.

Моногенеи – это одна из самых больших групп плоских червей, члены которой являются почти исключительно паразитами водных позвоночных (эктопаразитами). Они используют адгезивные органы для прикрепления к хозяину. Эта конструкция также состоит из присосок. Цестоды, как правило – это внутренние черви (эндопаразиты), которым требуется более одного хозяина для их сложных жизненных циклов.

Теперь Вы знаете где водятся плоские черви. Давайте же посмотрим, что они употребляют в пищу.

Чем питаются плоские черви?

Фото: Плоский кольчатый червь

Свободноживущие плоские черви в основном плотоядные, особенно приспособлены для поимки добычи. Их встречи с добычей кажутся в значительной степени случайными, за исключением некоторых видов, которые выделяют слизистые нити. Пищеварение является как внеклеточным, так и внутриклеточным. Пищеварительные ферменты (биологические катализаторы), которые смешиваются с пищевыми продуктами в кишечнике, уменьшают размер частиц пищи. Этот частично переваренный материал затем поглощается (фагоцитируется) клетками или абсорбируется; пищеварение затем завершается в клетках кишечника.

В паразитических группах происходит как внеклеточное, так и внутриклеточное пищеварение. Степень, в которой эти процессы происходят, зависит от характера пищи. Когда паразит воспринимает фрагменты пищи или тканей хозяина, кроме жидкостей или полужидкостей (например, кровь и слизь), в качестве питательных веществ, пищеварение оказывается в значительной степени внеклеточным. У тех, кто питается кровью, пищеварение в основном внутриклеточное, что часто приводит к отложению гематина, нерастворимого пигмента, образующегося в результате распада гемоглобина.

Хотя некоторые плоские черви являются свободноживущими и неразрушающими, многие другие виды (в частности, трематоды и ленточные черви) паразитируют на людях, домашних животных или на обоих. В Европе, Австралии, Северной и Южной Америке введения ленточных червей у людей были значительно снижены в результате обычного осмотра мяса. Но там, где санитарные условия плохие, а мясо съедено недоваренным, частота заражений ленточными червями высока.

Интересный факт: Тридцать шесть или более видов были зарегистрированы как паразитирующие у людей. Эндемические (локальные) очаги инфекции встречаются практически во всех странах, но широко распространенные инфекции возникают на Дальнем Востоке, в Африке и в тропической Америке.

Особенности характера и образа жизни

Фото: Плоский червь

Способность подвергаться регенерации тканей, помимо простого заживления ран, встречается у двух классов плоских червей: турбелярия и цестода. Турбеллярии, особенно планария, широко используются в исследованиях регенерации. Наибольшая регенеративная способность существует у видов, способных к бесполому размножению. Например, кусочки практически любой части турбулентного стеностума могут перерасти в совершенно новых червей. В некоторых случаях регенерация очень маленьких кусочков может привести к образованию несовершенных (например, безголовых) организмов.

Регенерация, хотя и редка у паразитических червей в целом, происходит у цестод. Большинство ленточных червей могут регенерировать из головы (сколекс) и области шеи. Это свойство часто затрудняет лечение людей от инфекций ленточных червей. Лечение может устранить только тело, или стробилу, оставляя сколекс все еще прикрепленным к кишечной стенке хозяина и, таким образом, способным производить новую стробилу, которая восстанавливает инвазию.

Личинки цестод из нескольких видов могут регенерировать себя из вырезанных областей. Разветвленная личиночная форма Sparganum prolifer, человеческого паразита, может подвергаться как бесполому размножению, так и регенерации.

Социальная структура и размножение

Фото: Зеленый плоский червь

За очень немногими исключениями, гермафродиты и их репродуктивные системы, как правило, сложны. В этих плоских червях обычно присутствуют многочисленные яички, но только один или два яичника. Женская система необычна тем, что она разделена на две структуры: яичники и вителлярию, часто известные как желточные железы. Клетки вителлярии образуют компоненты желтка и яичной скорлупы.

У ленточных червей лентообразное тело обычно делится на серию сегментов или проглоттид, каждая из которых развивает полный набор мужских и женских гениталий. Довольно сложный копулятивный аппарат состоит из вечного (способного поворачиваться наружу) полового члена у мужчины и канала или влагалища у женщины. Вблизи своего отверстия женский канал может дифференцироваться в различные трубчатые органы.

Размножение ресничных червей достигается с помощью ряда методов, которые включают половое размножение (одновременный гермафродит) и бесполое размножение (поперечное деление). При половом размножении яйца производятся и связываются в коконы, из которых вылупляются и развиваются молодые особи. При бесполом размножении некоторые виды разделяются на две половины, которые восстанавливаются, образуя недостающую половину, таким образом превращаясь в целый организм.

Тело настоящих ленточных червей – цестод – состоит из множества сегментов, известных как проглоттиды. Каждая из проглоттид содержит как мужские, так и женские репродуктивные структуры (как гермафродиты), которые способны к размножению независимо. Учитывая, что один ленточный червь может производить до тысячи проглоттид, это позволяет ленточным червям продолжать процветать. Например, одна проглоттида способна производить тысячи яиц, их жизненный цикл может продолжаться у другого хозяина, когда яйца проглатываются.

Хозяин, который глотает яйца, известен как промежуточный хозяин, учитывая, что именно в этом конкретном хозяине яйца выводятся, чтобы произвести личинок (корацидий). Личинки, однако, продолжают развиваться у второго хозяина (окончательного хозяина) и созревают на взрослой стадии.

Естественные враги плоских червей

Фото: Как выглядит плоский червь

Хищники имеют доступ к свободно перемещающимся плоским червям из класса турбелярия – в конце концов, они никоим образом не ограничиваются телами животных. Эти плоские черви живут в самых разных условиях, включая ручьи, ручьи, озера и пруды.

Чрезвычайно влажная среда — абсолютная необходимость для них. Они имеют тенденцию болтаться под камнями или в кучах листвы. Водяные клопы являются одним из примеров разнообразных хищников этих плоских червей — особенно жуки, ныряющие в воду, и молодняк стрекоз. Ракообразные, крошечные рыбы и головастики также обычно обедают этими видами плоских червей.

Если у вас есть рифовый аквариум и вы заметили внезапное присутствие надоедливых плоских червей, они могут вторгаться в ваши морские кораллы. Некоторые владельцы аквариумов предпочитают использовать определенные виды рыб для биологического управления плоскими червями. Примерами конкретных рыб, которые часто с энтузиазмом питаются плоскими червями, являются шестиструнные грызуны (Pseudocheilinus hexataenia), желтые грызуны (Halichoeres chrysus) и пятнистые мандарины (Synchiropus picturatus).

Многие плоские черви являются паразитами невольных хозяев, но некоторые из них также являются настоящими хищниками. Морские плоские черви — по большей части хищники. Крошечные беспозвоночные являются особенно любимой едой для них, включая червей, ракообразных и коловраток.

Популяция и статус вида

Фото: Плоский червь

В настоящее время идентифицировано более 20 000 видов, тип плоские черви составляет один из крупнейших типов после хордовых, моллюсков и членистоногих. Приблизительно 25-30% людей в настоящее время заражены по крайней мере одним видом паразитических червей. Заболевания, которые они вызывают, могут быть разрушительными. Глистные инфекции могут привести к различным и хроническим заболеваниям, таким как рубцевание глаз и слепота, отечность конечностей и неподвижность, блокирование пищеварения и недоедания, анемия и усталость.

Не так давно считалось, что заболевания людей, вызываемые паразитическими плоскими червями, ограничены бедными ресурсами по всей Африке, Азии и Южной Америке. Но в наш век глобальных путешествий и изменения климата, паразитические черви медленно, но верно перемещаются в некоторые части Европы и Северной Америки.

Долгосрочные последствия увеличения распространения паразитических червей трудно предсказать, но вред, который наносит инфекция, подчеркивает необходимость разработки стратегий борьбы, которые могут смягчить эту угрозу для здоровья населения в XXI веке. Инвазивные плоские черви могут также вызвать серьезные нарушения в экосистемах. Исследователи из Университета Нью-Гемпшира обнаружили, что плоские черви в устьях могут указывать на здоровье экосистемы, разрушая ее.

Плоские черви — двусторонне симметричные организмы с многоклеточными телами, которые демонстрируют организацию органов. Плоские черви, как правило, являются гермафродитными – функциональные репродуктивные органы обоих полов встречающиеся у одной особи. Некоторые современные данные свидетельствуют о том, что по крайней мере некоторые виды плоских червей могут быть вторично упрощены от более сложных предков.

Дата публикации: 05.10.2019 года

Дата обновления: 11.11.2019 года в 12:10

Теги:

- Двусторонне-симметричные

- Животные Австралии

- Животные Азии

- Животные Африки

- Животные Дальнего востока

- Животные долгожители

- Животные Евразии

- Животные Европы

- Животные Мадагаскара

- Животные на букву П

- Животные на букву Ч

- Животные Новой Зеландии

- Животные Субтропического пояса Северного полушария

- Животные Субтропического пояса Южного полушария

- Животные Тихого океана

- Животные Тропического пояса Северного полушария

- Животные Тропического пояса Южного полушария

- Животные Умеренного пояса Северного полушария

- Животные Умеренного пояса Южного полушария

- Животные Экваториального пояса

- Животные Южной Америки

- Интересные животные

- Необычные животные

- Опасные животные

- Первичноротые

- Плотоядные животные

- Эукариоты

- Эуметазои

Плоские черви — древняя группа многоклеточных двусторонне-симметричных животных. На настоящий момент тип плоские черви включает около 18 тысяч видов.

Представлен тремя классами: ресничные черви — наиболее высокоорганизованные, свободноживущие формы, ленточные черви и сосальщики — ведут паразитический образ

жизни.

Паразитические представители данного типа имеют медицинское значение, вызывают различные заболевания у человека и животных. Их жизненные циклы сложны, но

осознав их, вам легко будет сделать вывод о методах профилактики гельминтозов (заболеваний, вызванных гельминтами) и о способах заражения паразитом. Рекомендую по мере изучения паразитов сосредотачиваться именно на

их жизненных циклах, я уделю этой теме особое внимание.

Ароморфозы плоских червей

Чтобы отлично знать зоологию нужно помнить ароморфозы. Это те прогрессивные черты, которые ставят плоских червей на более высокий уровень организации, черты,

которые мы не найдем у предыдущего, изученного нами типа Кишечнополостные.

- Двусторонняя симметрия

- Кожно-мускульный мешок

- Третий зародышевый листок — мезодерма

- Появление переднего конца тела с комплексом органов чувств

- Нервная система лестничного типа

- Выделительная система

- Половые железы

- Дифференцировка пищеварительной системы

Плоские черви — двусторонне-симметричные (билатерально симметричные) животные, у которых органы расположены слева и справа от срединной плоскости,

при этом возможны несущественные отличия во внешнем строении и расположении внутренних органов.

У плоских червей впервые возникает кожно-мускульный мешок, который представляет собой единую систему покровных и мышечных тканей.

Плоские черви могут полноправно называться трехслойными животными. В отличие от кишечнополостных (двухслойных, у которых есть только эктодерма и энтодерма),

у плоских червей, между эктодермой и энтодермой возникает третий зародышевый листок — мезодерма (от греч. mesos — средний + derma — кожа).

Появление мезодермы приводит к развитию мышечного аппарата, который образует мышечный мешок, состоящий из нескольких слоев мышц.

У плоских червей клетки наружного мышечного слоя (кольцевая мускулатура) расположены поперек передне-задней оси тела,

клетки внутреннего мышечного слоя (продольная мускулатура) — вдоль передне-задней оси тела. Мышечные клетки также могут

объединяться в косые и спинно-брюшные мышцы.

Это очень важное приобретение для свободноживущих форм. Органы осязания, зрения, обоняния помогают лучше ориентироваться в пространстве,

что позволяет совершать целенаправленные движения.

Лестничный тип нервной системы (ортогон), называемый также — стволовой тип, заключается в объединении нервных клеток в нервные стволы.

Такая конфигурация напоминает лестницу, в связи с чем и называется — лестничная.

Состоит из парных мозговых ганглиев (нервных узлов — от греч. ganglion — узел) от которых отходят два продольных нервных ствола (коннективы),

соединяющиеся между собой поперечными нервными стволами (комиссурами).

Головной отдел несколько обособляется за счет большей концентрации

нервных клеток в мозговых ганглиях: постепенно начинается цефализация (от греч. kephalē — голова) — процесс обособления головы.

У простейших и кишечнополостных выделение осуществлялось всей поверхностью тела. У плоских червей в этой области происходит колоссальный прорыв —

впервые появляются специализированные органы выделения, называемые протонефридиями.

Протонефридии представляют собой систему простых или

ветвящихся канальцев эктодермального происхождения, расположенных в паренхиме (мезенхиме). Протонефридии объединяются в трубочки,

открывающиеся порами на поверхности тела.

Протонефридий состоит из большого числа ветвящихся канальцев, оканчивающихся клетками с просветом внутри. Если в этот просвет выступает

много ресничек, то такая клетка называется пламенной (звездчатой, мерцательной). Реснички пламенной клетки колеблются,

и это напоминает колебания пламени свечи, отсюда и название. Эти движения создают непрерывный ток жидкости.

Протонефридии представляют собой

каналы, слепо начинающиеся в мезенхиме от пламенных (звездчатых) клеток с ресничками, обращенными в полость канала. Каждая пламенная клетка захватывает из

паренхимы (мезенхимы) жидкие продукты распада и транспортирует их в систему каналов.

Мелкие выделительные каналы сливаются в большие, которые открываются на поверхности тела выделительными порами.

Мужские половые органы представлены семенниками, женские — яичниками.

Оплодотворение

внутреннее — сперматозоид и яйцеклетка сливаются внутри организма (гермафродита), в женских половых органах. Оплодотворение перекрестное — между двумя особями.

У плоских червей впервые появляются специализированные органы размножения, которые относятся к наиболее сложно устроенным среди всех организмов царства животные.

Мужская половая система включает один или несколько семенников, семяпровод и семяизвергательный канал. Женская половая система состоит из яичников,

желточников, семяприемников, матки. У зиготы впервые появляется запас питательных веществ и скорлуповая оболочка.

В желточниках накапливаются запасы питательных веществ, энергия которых используются развивающимися яйцеклетками. В скорлуповой железе (по-другому называется —

оотип) происходит

оплодотворение яйцеклетки сперматозоидом, после чего образовавшаяся зигота покрывается твердой оболочкой — скорлупой.

В пищеварительной системе выделяются передний и средний отделы. Передний отдел представлен ртом, продолжающимся в глотку. Средний отдел представлен

слепо заканчивающимися каналами, доставляющими питательные вещества к органам и тканям.

Общая характеристика

- Опорно-двигательная система, покровы тела

- Пищеварительная система

- Дыхание

- Выделительная систем

- Нервная система

- Половая система

Тело листовидное, вытянутое в длину. Имеется кожно-мускульный мешок, образованный однослойным эпителием и несколькими слоями мышечных волокон.

Клетки эпителия выделяют слизь,

снижающую трение и облегчающую движения. У свободноживущих имеется 3 слоя мышц: кольцевые, продольные и косые (диагональные). У паразитических

особей выделяют только 2 слоя мышц: кольцевые и продольные. Также у плоских червей имеются спинно-брюшные мышцы. Сокращение мышц изменяет форму тела.

У свободноживущих форм покровы тела представлены однослойным эпителием, чего не скажешь про паразитические формы. Паразиты в организме-хозяине

часто сталкиваются с агрессивной средой желудочных и кишечных соков, в которых они могли бы перевариться, не будь у них — тегумента. Тегумент —

это плотный, особый вид эпителия, выполняющий барьерную и секреторную функции. Он отделен от нижележащих мышц базальной пластинкой.

Именно тегумент препятствует перевариванию червя, благодаря чему он может

жить в организме человека и животных долгие годы.

Особо хочу отметить, что во многих устаревших руководствах написано вместо тегумента — «кутикула». На данный момент с помощью электронного микроскопа

установлено, что наружный покров является именно тегументом — слоем слипшихся между собой клеток, а не кутикулой. Эти ошибки будут кочевать

по пособиям и руководствам еще долгие годы, поэтому, к сожалению, приходится уделять им внимание.

Полость тела у плоских червей отсутствует. Внутри находится паренхима мезодермального происхождения (мезенхима) — рыхлая соединительная ткань, заполняющая промежутки между органами. Выполняет

опорную и запасающую функции, участвует в обмене веществ. При голодании организма паренхима постепенно истончается.

Плоские черви обладают выраженной способности к регенерации. Они могут восстановить 6/7 утраченных частей своего тела.

Замкнутая, анальное отверстие отсутствует. Непереваренные остатки пищи удаляются через ротовое отверстие. Имеется дифференцировка пищеварительной

системы на передней и средний отделы.

Отметьте, что у представителей класса ленточные черви пищеварительная система отсутствует полностью, они

всасывают расщепленные вещества всей поверхностью тела.

У свободноживущих форм дыхание аэробное, дышат они всей поверхностью тела растворенным в воде кислородом. У паразитических форм дыхание

анаэробное (бескислородное), это менее продуктивный тип дыхания, но адаптированный для условий их обитания, в частности кишечника, где

по большей части среда бескислородная.

Специализированные органы выделения — протонефридии.

Нервная система лестничного (ортогонального) типа.

Подавляющее большинство плоских червей — гермафродиты (обоеполые), то есть на одном организме находятся и мужские, и женские половые органы.

Половая система устроена сложно. Мужские половые органы представлены семенниками, семяпроводом и семяизвергательным каналом. Женская половая

система включает в себя влагалище, яичники, яйцеводы, протоки которых впадают в оотип (скорлуповую железу), слепо замкнутой матки.

Запомните, что такое прогрессивное развитие половой системы в целом характерно для паразитов. Их основная задача — размножиться, заразить другой организм,

а вероятность такого события относительно небольшая. И, чтобы ее увеличить, они выделяют огромное количество яиц. В матке одного зрелого членика бычьего цепня

в среднем содержится около 150 тысяч яиц, в день отделяется 6-8 члеников — около миллиона яиц. За год бычий цепень выделяет около 300-500 миллионов яиц.

Смена хозяев в жизненном цикле

В качестве приспособления к паразитическому образу жизни у плоских червей в жизненном цикле выработалась смена хозяев. У сосальщиков

наблюдается сложное чередование поколений.

Изучая жизненные циклы, вы часто будете сталкиваться с экологическим понятием «хозяин». Хозяин — организм, используемый паразитом для обитания,

размножения, собственной защиты. Выделяют несколько типов хозяев:

- Основной

- Промежуточный

- Дополнительный

- Тупиковый

Вид, на котором обычно паразитирует данная категория паразитов. В организме основного хозяина происходит половое размножение

паразита.

Вид, в котором паразит обитает в личиночном виде. В организме промежуточного хозяина происходит бесполое размножение паразита.

Вид, обычно не страдающий от нападения паразита, но заражаемый им чаще всего при массовом размножении паразитов.

Вид, случайно заражающийся данной категорией паразитов. Паразиты, оказавшись в таком организме, чаще всего не имеют возможности

для размножения и продолжения своего рода.

Человек для эхинококка является тупиковым хозяином, так как человека никто не ест.

© Беллевич Юрий Сергеевич 2018-2022

Данная статья написана Беллевичем Юрием Сергеевичем и является его интеллектуальной собственностью. Копирование, распространение

(в том числе путем копирования на другие сайты и ресурсы в Интернете) или любое иное использование информации и объектов

без предварительного согласия правообладателя преследуется по закону. Для получения материалов статьи и разрешения их использования,

обратитесь, пожалуйста, к Беллевичу Юрию.

Тип Плоские черви

3.9

Средняя оценка: 3.9

Всего получено оценок: 3044.

3.9

Средняя оценка: 3.9

Всего получено оценок: 3044.

В типе “Плоские черви”объединены 15 тыс. видов примитивных животных, большинство из которых ведёт паразитический образ жизни.

Признаки типа Плоские черви

Как следует из названия типа, эти черви имеют уплощённое тело. Также для них характерно:

- отсутствие полости тела;

- замкнутый кишечник;

- отсутствие органов дыхания;

- сложный жизненный цикл со сменой хозяев.

Все пустоты внутри тела плоских червей заполнены соединительной тканью – паренхимой.

Кишечник замкнут, анального отверстия нет. Выделение осуществляется специальными каналами – протонефридиями, которые выводят ненужные вещества из паренхимы во внешнюю среду.

Дыхание

Свободноживущие виды дышат через кожу. Паразиты приспособлены к жизни в бескислородной среде кишечника или печени хозяина.

ТОП-1 статья

которые читают вместе с этой

Размножение

Плоские черви – гермафродиты, т. е. развитие мужских и женских гамет, а также последующее оплодотворение происходит внутри каждой особи.

Систематика

Тип Плоские черви разделяется на девять классов. Важнейшими классами являются:

- ресничные черви (планарии);

- сосальщики (трематоды);

- ленточные черви (цестоды).

Планарии

Насчитывают 3500 видов. Практически все они являются свободноживущими водными организмами.

Имеют глаза, органы осязания и равновесия, а также реснички, с помощью которых плавают.

Трематоды

Класс включает 4 тыс. видов паразитов.

В тропических районах трематодами заражено более 900 млн человек. Заражение происходит при проглатывании личинок червей с водой.

Жизненный цикл печёночного сосальщика

Взрослая особь живёт чаще всего в печени коров. Яйца через коровий кишечник попадают на пастбища. Если они оказываются в водоёме или луже, то из них выходят плавающие личинки – мирацидии.

Это второе поколение, поисковая фаза развития. Мирацидии находят моллюсков прудовиков и проникают в них. В прудовике мирацидий превращается в спороцисту.

Из неё выходят личинки – редии, питающиеся тканями прудовика. Это третье поколение, паразитирующее внутри тела промежуточного хозяина.

В теле редий образуются новые организмы – церкарии, которые выходят из прудовика и прикрепляются к растениям, после чего превращаются в цисту, стадию покоя. Такими цистами вновь заражаются коровы. Фактически, цисты – это зачаточные сосальщики, первое поколение.

Цестоды

Все представители класса – внутренние паразиты животных и человека (3 тыс. видов). Тело состоит из множества одинаковых члеников и головки.

Головкой червь прикрепляется к кишечнику хозяина. Это происходит с помощью специальных:

- присосок;

- крючьев.

В паренхиме члеников находятся органы:

- нервной;

- половой;

- выделительной системы.

Кишечник отсутствует, питательные вещества всасываются кожей.

Основной путь заражения людей плоскими червями – употребление в пищу недостаточно проваренного или прожаренного мяса и рыбы.

Таблица “Тип Плоские черви”

|

Классы |

Особенности |

Представители |

|

Планарии |

Органы чувств, кишечник, активно двигаются |

Молочная планария |

|

Трематоды |

2 присоски, одна из них – со ртом, обитают во внутренних органах животных |

Кошачья двуустка; ланцетовидный сосальщик; шизостомы |

|

Цестоды |

Членистое строение тела, длина до 15 м, отсутствие кишечника |

Эхинококк, разные виды цепней |

Что мы узнали?

Изучая данную тему по биологии 7 класса, мы дали общую характеристику типа Плоские черви. Паразитические виды типа значительно более примитивны, чем свободноживущие. Животные и человек являются хозяевами сосальщиков и цестод.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Варя Старикова

8/10

-

Кирилл Быков

10/10

-

Оптимус Прайм

10/10

-

Александр Кузнецов

10/10

-

Мудуркат Лачинова

10/10

-

Габриэлла Шульгина

10/10

-

Жаргал Гатапов

10/10

-

Кирилл Ковалев

10/10

-

Валентин Муравьёв

7/10

Оценка доклада

3.9

Средняя оценка: 3.9

Всего получено оценок: 3044.

А какая ваша оценка?

- Энциклопедия

- Насекомые

- Плоские черви

Плоские черви имеют особый слой-мезодерму, который помогает образовывать им органы системы. Благодаря такой функции плоские черви превосходят любой вид множества животных. У них нет кровеносной системы, а тело довольно уплотненное. Рот обычно находиться впереди либо на брюшной части тела. Также в начале тела у червей расположен мозг. У некоторых форм в начале тела образованы органы чувств, такие как глаза или щупальца. Они являются гермафродитами и имеют как простую, так и сложную фазу развития.

Всего в мире существует 12500 видов плоских червей. У них есть системы органов, но отсутствует полость рта. Существует три вида плоских червей.

Турбеллярии. Черви этого вида живут в канавах и прудах преимущественно в ночное время. Тело червя похоже на слизистый мешок с ресничным покрытием. Ест он мелких червяков различных ракообразных, а также то, что остаётся от крупных обитателей подводного мира. Выделительная система насчитывает два канала. Размножается половым и бесполым путем.

Вид сосальщиков. Обитают представители данного вида в желчи у крупных животных и у человека в желчных протоках. Достигшие полового созревания организмы производят в день около 1000 яиц. Для того чтобы дальше развиваться им необходимо быть в воде. Для того чтобы не подхватить такого пассажира не стоит пить воду из водоемов и хорошо промывать овощи и фрукты.

Вид ленточных червей. В этот вид входит около 3000 червей. Существуют они, как правило, в тонком кишечнике и у них отсутствует система пищеварения. Развиваются они также как и сосальщики когда меняют носителей.

Широкий лентец также очень опасный паразит. Попадает в организм через рыбу. И Эхинококк ,который передает человеку собака.

Вариант №2

На сегодняшний день в мире насчитывается более двадцати пяти тысяч видов плоских червей или так называемых паразитов. Тело у плоского червя состоит из трех слоев клеток (эктодермы, энтодермы и мезодермы).

Плоские черви – это паразиты, которые поражают не только человека, но и животное. Паразиты могут находиться абсолютно везде, в траве, еде, на руках человека, в метро и других местах. Если плоский червь попадет в любой живой организм, то он может вызвать серьезное заболевание или сбой любого органа.

Плоский червь может вызвать у человека в организме сильные боли, резкую потерю веса, и малокровие.

Плоские черви делаться на семь классов:

1) Ленточные;

2) Аспидогастры;

3) Гирокотилиды;

4) Цестодообразные;

5) Ресничные;

6) Моногенеи;

7) Трематоды;

Плоские черви вызывают постоянную тошноту, депрессию, частые поносы, при сильном заражении могут вызвать помутнение разума.

Виды паразитов.

- Острицы – длина червя один сантиметр, живут только в кишечнике, заражение таким паразитом приводит к сильной диарее, бессоннице, потере веса.

- Аскариды – длина червя до тридцати сантиметров, поражают все органы человека, заражение приводит к астме, аллергии и сбой пораженных органов.

- Трихинеллы – длина червя может достигать более одного километра, заражение приводит к отекам конечностей, расстройству желудка и лихорадке.

- Власоглавы – длина этого паразита до пяти сантиметров, заражение приводит к сильной слабости, развивает анемию, отравление токсинами.

- Свиной цепень – червь вырастает до восьми метров в длину, такое поражение может привести к непроходимости кишечника, судорогам, и высокой температуре.

Это малая часть существующих паразитов, все они очень опасны.

Если у человека присутствует хотя бы один симптом, то нужно немедленно обратиться к врачу и сделать диагностику организма. Не всех паразитов можно распознать через калл, иногда приходиться делать УЗИ или томографию.

Чтобы не заразиться плоскими червями нужно постоянно мыть руки, овощи, фрукты, хорошо обжаривать мясо и рыбу и обязательно проводить профилактику от глистов у домашних животных хотя бы один раз в год.

6 класс, 7 класс по биологии

Плоские черви

Популярные темы сообщений

- История развития геометрии

Один из самых сложных предметов, как в школе, так и в университете является геометрия. Все это, потому что эта наука заставляет думать, мыслить логически, доказывать. Геометрия — наука, сведения о которой люди получили еще в самой древности.

- Свойства металлов

Слово «металл» произошло от греческого слова «копь». Соответственно, металлы добывают из земли в виде полезных ископаемых. Сначала необходимо получить руды, из которых потом извлекают металлы. Добычу проводят двумя способами: открытым либо

- Железная руда

Железо — это прочный металл, использовать который, люди начали еще много веков назад. Но найти его в чистом виде невозможно. Оно содержится во многих горных породах в виде соединения с другими минералами. Так вот,

- Грибоедов

Многие русские художники пытались изобразить Грибоедова, и у всех получилось по- разному. Своеобразно обрисовал нам личность писателя Пушкин в книге «Путешествие в Арзрум». Попытаемся прояснить, каким же был на самом деле литератором Грибоедов.

- Сирень

Цветение в весенний период любых растений вызывает у человека самые лучшие эмоции. Любование необыкновенными цветками сирени надолго оставляет в памяти и ее внешний образ, и аромат.

| Flatworm

Temporal range: 270–0 Ma[1] PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N Possible Cambrian, Ordovician and Devonian records[2][3] |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Bedford’s flatworm, Pseudobiceros bedfordi | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| (unranked): | Spiralia |

| Clade: | Rouphozoa |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes Claus, 1887 |

| Classes | |

|

Traditional:

Phylogenetic:

|

|

| Synonyms | |

|

The flatworms, flat worms, Platyhelminthes, or platyhelminths (from the Greek πλατύ, platy, meaning «flat» and ἕλμινς (root: ἑλμινθ-), helminth-, meaning «worm»)[4] are a phylum of relatively simple bilaterian, unsegmented, soft-bodied invertebrates. Unlike other bilaterians, they are acoelomates (having no body cavity), and have no specialized circulatory and respiratory organs, which restricts them to having flattened shapes that allow oxygen and nutrients to pass through their bodies by diffusion. The digestive cavity has only one opening for both ingestion (intake of nutrients) and egestion (removal of undigested wastes); as a result, the food cannot be processed continuously.

In traditional medicinal texts, Platyhelminthes are divided into Turbellaria, which are mostly non-parasitic animals such as planarians, and three entirely parasitic groups: Cestoda, Trematoda and Monogenea; however, since the turbellarians have since been proven not to be monophyletic, this classification is now deprecated. Free-living flatworms are mostly predators, and live in water or in shaded, humid terrestrial environments, such as leaf litter. Cestodes (tapeworms) and trematodes (flukes) have complex life-cycles, with mature stages that live as parasites in the digestive systems of fish or land vertebrates, and intermediate stages that infest secondary hosts. The eggs of trematodes are excreted from their main hosts, whereas adult cestodes generate vast numbers of hermaphroditic, segment-like proglottids that detach when mature, are excreted, and then release eggs. Unlike the other parasitic groups, the monogeneans are external parasites infesting aquatic animals, and their larvae metamorphose into the adult form after attaching to a suitable host.

Because they do not have internal body cavities, Platyhelminthes were regarded as a primitive stage in the evolution of bilaterians (animals with bilateral symmetry and hence with distinct front and rear ends). However, analyses since the mid-1980s have separated out one subgroup, the Acoelomorpha, as basal bilaterians – closer to the original bilaterians than to any other modern groups. The remaining Platyhelminthes form a monophyletic group, one that contains all and only descendants of a common ancestor that is itself a member of the group. The redefined Platyhelminthes is part of the Lophotrochozoa, one of the three main groups of more complex bilaterians. These analyses had concluded the redefined Platyhelminthes, excluding Acoelomorpha, consists of two monophyletic subgroups, Catenulida and Rhabditophora, with Cestoda, Trematoda and Monogenea forming a monophyletic subgroup within one branch of the Rhabditophora. Hence, the traditional platyhelminth subgroup «Turbellaria» is now regarded as paraphyletic, since it excludes the wholly parasitic groups, although these are descended from one group of «turbellarians».

Two planarian species have been used successfully in the Philippines, Indonesia, Hawaii, New Guinea, and Guam to control populations of the imported giant African snail Achatina fulica, which was displacing native snails. However, these planarians are themselves a serious threat to native snails and should not be used for biological control. In northwest Europe, there are concerns about the spread of the New Zealand planarian Arthurdendyus triangulatus, which preys on earthworms.

Description[edit]

Distinguishing features[edit]

Platyhelminthes are bilaterally symmetrical animals: their left and right sides are mirror images of each other; this also implies they have distinct top and bottom surfaces and distinct head and tail ends. Like other bilaterians, they have three main cell layers (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm),[5] while the radially symmetrical cnidarians and ctenophores (comb jellies) have only two cell layers.[6] Beyond that, they are «defined more by what they do not have than by any particular series of specializations.»[7] Unlike most other bilaterians, Platyhelminthes have no internal body cavity, so are described as acoelomates. Although the absence of a coelom also occurs in other bilaterians: gnathostomulids, gastrotrichs, xenacoelomorphs, cycliophorans, entoproctans and the parastic mesozoans.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] They also lack specialized circulatory and respiratory organs, both of these facts are defining features when classifying a flatworm’s anatomy.[5][15] Their bodies are soft and unsegmented.[16]

| Attribute | Cnidarians and Ctenophores[6] | Platyhelminthes (flatworms)[5][15] | More «advanced» bilaterians[17] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral symmetry | No | Yes | |

| Number of main cell layers | Two, with jelly-like layer between them (mesoglea) | Three | |

| Distinct brain | No | Yes | |

| Specialized digestive system | No | Yes | |

| Specialized excretory system | No | Yes | |

| Body cavity containing internal organs | No | Yes | |

| Specialized circulatory and respiratory organs | No | Yes |

Features common to all subgroups[edit]

The lack of circulatory and respiratory organs limits platyhelminths to sizes and shapes that enable oxygen to reach and carbon dioxide to leave all parts of their bodies by simple diffusion. Hence, many are microscopic, and the large species have flat ribbon-like or leaf-like shapes. Because there is no circulatory system which can transport nutrients around, the guts of large species have many branches, allowing the nutrients to diffuse to all parts of the body.[7] Respiration through the whole surface of the body makes them vulnerable to fluid loss, and restricts them to environments where dehydration is unlikely: sea and freshwater, moist terrestrial environments such as leaf litter or between grains of soil, and as parasites within other animals.[5]

The space between the skin and gut is filled with mesenchyme, also known as parenchyma, a connective tissue made of cells and reinforced by collagen fibers that act as a type of skeleton, providing attachment points for muscles. The mesenchyme contains all the internal organs and allows the passage of oxygen, nutrients and waste products. It consists of two main types of cell: fixed cells, some of which have fluid-filled vacuoles; and stem cells, which can transform into any other type of cell, and are used in regenerating tissues after injury or asexual reproduction.[5]

Most platyhelminths have no anus and regurgitate undigested material through the mouth. The genus Paracatenula, tiny flatworms living in symbiosis with bacteria, is even missing a mouth and a gut.[18] However, some long species have an anus and some with complex, branched guts have more than one anus, since excretion only through the mouth would be difficult for them.[15] The gut is lined with a single layer of endodermal cells that absorb and digest food. Some species break up and soften food first by secreting enzymes in the gut or pharynx (throat).[5]

All animals need to keep the concentration of dissolved substances in their body fluids at a fairly constant level. Internal parasites and free-living marine animals live in environments with high concentrations of dissolved material, and generally let their tissues have the same level of concentration as the environment, while freshwater animals need to prevent their body fluids from becoming too dilute. Despite this difference in environments, most platyhelminths use the same system to control the concentration of their body fluids. Flame cells, so called because the beating of their flagella looks like a flickering candle flame, extract from the mesenchyme water that contains wastes and some reusable material, and drive it into networks of tube cells which are lined with flagella and microvilli. The tube cells’ flagella drive the water towards exits called nephridiopores, while their microvilli reabsorb reusable materials and as much water as is needed to keep the body fluids at the right concentration. These combinations of flame cells and tube cells are called protonephridia.[5][17]

In all platyhelminths, the nervous system is concentrated at the head end. Other platyhelminths have rings of ganglia in the head and main nerve trunks running along their bodies.[5][15]

Major subgroups[edit]

Early classification divided the flatworms in four groups: Turbellaria, Trematoda, Monogenea and Cestoda. This classification had long been recognized to be artificial, and in 1985, Ehlers[19] proposed a phylogenetically more correct classification, where the massively polyphyletic «Turbellaria» was split into a dozen orders, and Trematoda, Monogenea and Cestoda were joined in the new order Neodermata. However, the classification presented here is the early, traditional, classification, as it still is the one used everywhere except in scientific articles.[5][20]

Turbellaria[edit]

These have about 4,500 species,[15] are mostly free-living, and range from 1 mm (0.04 in) to 600 mm (24 in) in length. Most are predators or scavengers, and terrestrial species are mostly nocturnal and live in shaded, humid locations, such as leaf litter or rotting wood. However, some are symbiotes of other animals, such as crustaceans, and some are parasites. Free-living turbellarians are mostly black, brown or gray, but some larger ones are brightly colored.[5] The Acoela and Nemertodermatida were traditionally regarded as turbellarians,[15][21] but are now regarded as members of a separate phylum, the Acoelomorpha,[22] or as two separate phyla.[24] Xenoturbella, a genus of very simple animals,[25] has also been reclassified as a separate phylum.[26]

Some turbellarians have a simple pharynx lined with cilia and generally feed by using cilia to sweep food particles and small prey into their mouths, which are usually in the middle of their undersides. Most other turbellarians have a pharynx that is eversible (can be extended by being turned inside-out), and the mouths of different species can be anywhere along the underside.[5] The freshwater species Microstomum caudatum can open its mouth almost as wide as its body is long, to swallow prey about as large as itself.[15]

Most turbellarians have pigment-cup ocelli («little eyes»); one pair in most species, but two or even three pairs in others. A few large species have many eyes in clusters over the brain, mounted on tentacles, or spaced uniformly around the edge of the body. The ocelli can only distinguish the direction from which light is coming to enable the animals to avoid it. A few groups have statocysts — fluid-filled chambers containing a small, solid particle or, in a few groups, two. These statocysts are thought to function as balance and acceleration sensors, as they perform the same way in cnidarian medusae and in ctenophores. However, turbellarian statocysts have no sensory cilia, so the way they sense the movements and positions of solid particles is unknown. On the other hand, most have ciliated touch-sensor cells scattered over their bodies, especially on tentacles and around the edges. Specialized cells in pits or grooves on the head are most likely smell sensors.[15]

Planarians, a subgroup of seriates, are famous for their ability to regenerate if divided by cuts across their bodies. Experiments show that (in fragments that do not already have a head) a new head grows most quickly on those fragments which were originally located closest to the original head. This suggests the growth of a head is controlled by a chemical whose concentration diminishes throughout the organism, from head to tail. Many turbellarians clone themselves by transverse or longitudinal division, whilst others, reproduce by budding.[15]

The vast majority of turbellarians are hermaphrodites (they have both female and male reproductive cells) which fertilize eggs internally by copulation.[15] Some of the larger aquatic species mate by penis fencing – a duel in which each tries to impregnate the other, and the loser adopts the female role of developing the eggs.[27] In most species, «miniature adults» emerge when the eggs hatch, but a few large species produce plankton-like larvae.[15]

Trematoda[edit]

These parasites’ name refers to the cavities in their holdfasts (Greek τρῆμα, hole),[5] which resemble suckers and anchor them within their hosts.[16] The skin of all species is a syncitium, which is a layer of cells that shares a single external membrane. Trematodes are divided into two groups, Digenea and Aspidogastrea (also known as Aspodibothrea).[15]

Digenea[edit]

These are often called flukes, as most have flat rhomboid shapes like that of a flounder (Old English flóc). There are about 11,000 species, more than all other platyhelminthes combined, and second only to roundworms among parasites on metazoans.[15] Adults usually have two holdfasts: a ring around the mouth and a larger sucker midway along what would be the underside in a free-living flatworm.[5]

Although the name «Digeneans» means «two generations», most have very complex life cycles with up to seven stages, depending on what combinations of environments the early stages encounter – the most important factor being whether the eggs are deposited on land or in water. The intermediate stages transfer the parasites from one host to another. The definitive host in which adults develop is a land vertebrate; the earliest host of juvenile stages is usually a snail that may live on land or in water, whilst in many cases, a fish or arthropod is the second host.[15] For example, the adjoining illustration shows the life cycle of the intestinal fluke metagonimus, which hatches in the intestine of a snail, then moves to a fish where it penetrates the body and encysts in the flesh, then migrating to the small intestine of a land animal that eats the fish raw, finally generating eggs that are excreted and ingested by snails, thereby completing the cycle. A similar life cycle occurs with Opisthorchis viverrini, which is found in South East Asia and can infect the liver of humans, causing Cholangiocarcinoma (bile duct cancer). Schistosomes, which cause the devastating tropical disease bilharzia, also belong to this group.[28]

Adults range between 0.2 mm (0.0079 in) and 6 mm (0.24 in) in length. Individual adult digeneans are of a single sex, and in some species slender females live in enclosed grooves that run along the bodies of the males, partially emerging to lay eggs. In all species the adults have complex reproductive systems, capable of producing between 10,000 and 100,000 times as many eggs as a free-living flatworm. In addition, the intermediate stages that live in snails reproduce asexually.[15]

Adults of different species infest different parts of the definitive host — for example the intestine, lungs, large blood vessels,[5] and liver.[15] The adults use a relatively large, muscular pharynx to ingest cells, cell fragments, mucus, body fluids or blood. In both the adult and snail-inhabiting stages, the external syncytium absorbs dissolved nutrients from the host. Adult digeneans can live without oxygen for long periods.[15]

Aspidogastrea[edit]

Members of this small group have either a single divided sucker or a row of suckers that cover the underside.[15] They infest the guts of bony or cartilaginous fish, turtles, or the body cavities of marine and freshwater bivalves and gastropods.[5] Their eggs produce ciliated swimming larvae, and the life cycle has one or two hosts.[15]

Cercomeromorpha[edit]

These parasites attach themselves to their hosts by means of disks that bear crescent-shaped hooks. They are divided into the Monogenea and Cestoda groupings.[15]

Monogenea[edit]

Of about 1,100 species of monogeneans, most are external parasites that require particular host species — mainly fish, but in some cases amphibians or aquatic reptiles. However, a few are internal parasites. Adult monogeneans have large attachment organs at the rear, known as haptors (Greek ἅπτειν, haptein, means «catch»), which have suckers, clamps, and hooks. They often have flattened bodies. In some species, the pharynx secretes enzymes to digest the host’s skin, allowing the parasite to feed on blood and cellular debris. Others graze externally on mucus and flakes of the hosts’ skins. The name «Monogenea» is based on the fact that these parasites have only one nonlarval generation.[15]

Cestoda[edit]

Life cycle of the eucestode Taenia: Inset 5 shows the scolex, which has four Taenia solium, a disk with hooks on the end. Inset 6 shows the tapeworm’s whole body, in which the scolex is the tiny, round tip in the top left corner, and a mature proglottid has just detached.

These are often called tapeworms because of their flat, slender but very long bodies – the name «cestode» is derived from the Latin word cestus, which means «tape». The adults of all 3,400 cestode species are internal parasites.

Cestodes have no mouths or guts, and the syncitial skin absorbs nutrients – mainly carbohydrates and amino acids – from the host, and also disguises it chemically to avoid attacks by the host’s immune system.[15] Shortage of carbohydrates in the host’s diet stunts the growth of parasites and may even kill them. Their metabolisms generally use simple but inefficient chemical processes, compensating for this inefficiency by consuming large amounts of food relative to their physical size.[5]

In the majority of species, known as eucestodes («true tapeworms»), the neck produces a chain of segments called proglottids via a process known as strobilation. As a result, the most mature proglottids are furthest from the scolex. Adults of Taenia saginata, which infests humans, can form proglottid chains over 20 metres (66 ft) long, although 4 metres (13 ft) is more typical. Each proglottid has both male and female reproductive organs. If the host’s gut contains two or more adults of the same cestode species they generally fertilize each other, however, proglottids of the same worm can fertilize each other and even themselves. When the eggs are fully developed, the proglottids separate and are excreted by the host. The eucestode life cycle is less complex than that of digeneans, but varies depending on the species. For example:

- Adults of Diphyllobothrium infest fish, and the juveniles use copepod crustaceans as intermediate hosts. Excreted proglottids release their eggs into the water where the eggs hatch into ciliated, swimming larvae. If a larva is swallowed by a copepod, it sheds the cilia and the skin becomes a syncitium; the larva then makes its way into the copepod’s hemocoel (an internal cavity which is the central part of the circulatory system) where it attaches itself using three small hooks. If the copepod is eaten by a fish, the larva metamorphoses into a small, unsegmented tapeworm, drills through to the gut and grows into an adult.[15]

- Various species of Taenia infest the guts of humans, cats and dogs. The juveniles use herbivores – such as pigs, cattle and rabbits – as intermediate hosts. Excreted proglottids release eggs that stick to grass leaves and hatch after being swallowed by a herbivore. The larva then makes its way to the herbivore’s muscle tissue, where it metamorphoses into an oval worm about 10 millimetres (0.39 in) long, with a scolex that is kept internally. When the definitive host eats infested raw or undercooked meat from an intermediate host, the worm’s scolex pops out and attaches itself to the gut, when the adult tapeworm develops.[15]

Members of the smaller group known as Cestodaria have no scolex, do not produce proglottids, and have body shapes similar to those of diageneans. Cestodarians parasitize fish and turtles.[5]

Classification and evolutionary relationships[edit]

The relationships of Platyhelminthes to other Bilateria are shown in the phylogenetic tree:[22]

The internal relationships of Platyhelminthes are shown below. The tree is not fully resolved.[30][31][32]