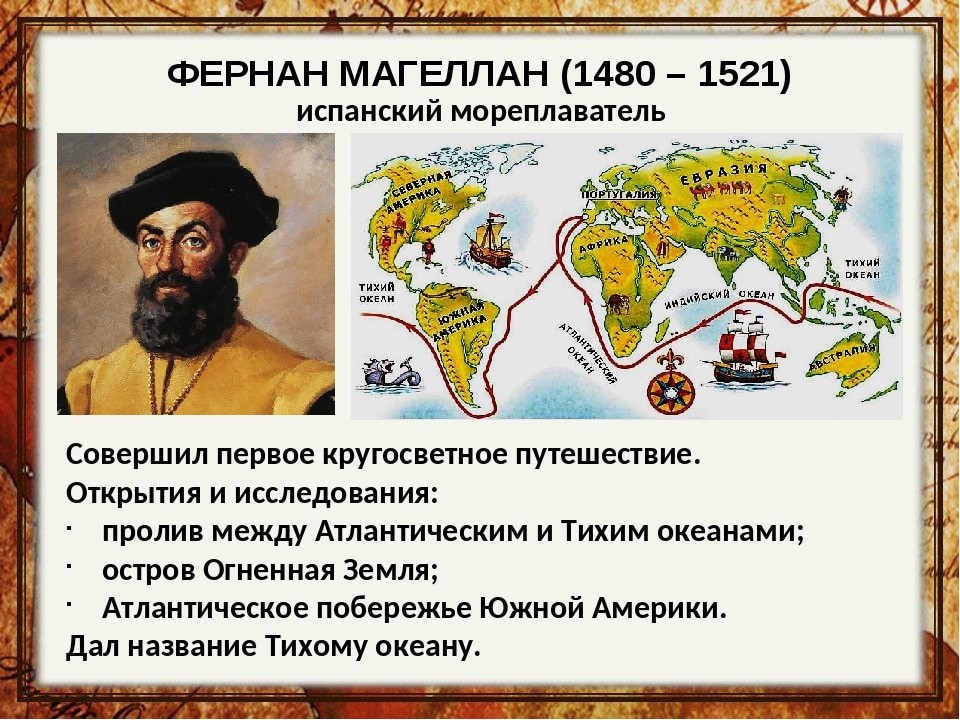

Фернан Магеллан ((1480)–(1)(521)) — португальский мореплаватель, совершивший первое кругосветное плавание.

Фернан Магеллан родился в местечке Саброза (Португалия) в бедной дворянской семье. Он с детства любил море, с которым связал всю свою жизнь. В (1492)–(1504) годах он служил пажом при дворе португальской королевы. Одновременно изучал астрономию, навигацию и космографию.

С (1505) года в течение восьми лет служил в военно-морском флоте Португалии, воевал в Северной Африке. Затем, вернувшись на родину, он просил у короля повышение по службе, но получил отказ.

Оскорблённый и отвергнутый, Фернан Магеллан уехал в Испанию. Там он заключил договор, по которому король Испании Карл (I) снарядил первое кругосветное плавание и руководителем его назначил Фернана Магеллана.

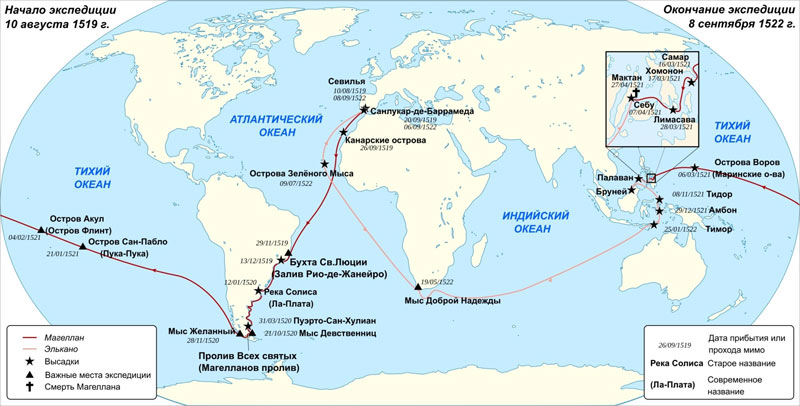

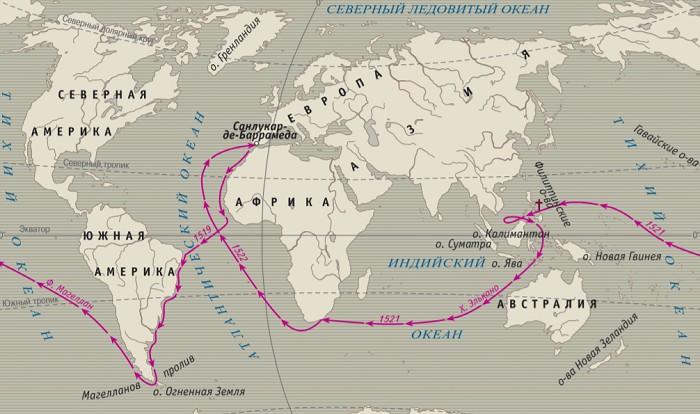

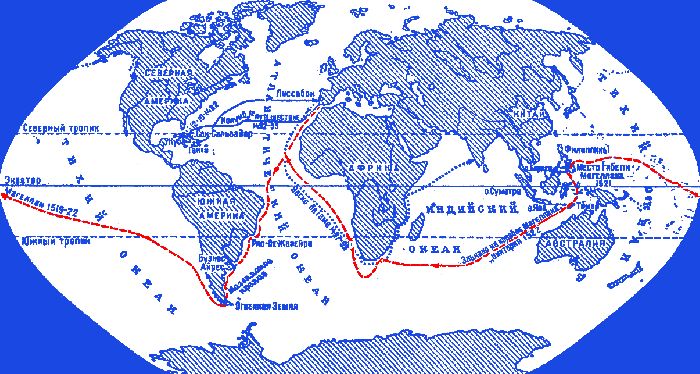

(20) сентября (1519) года на пяти небольших кораблях Магеллан покинул испанский порт Санлукар. С самого начала плавания он не был уверен в его счастливом завершении, поскольку в те времена мысль о шарообразной форме Земли была лишь предположением.

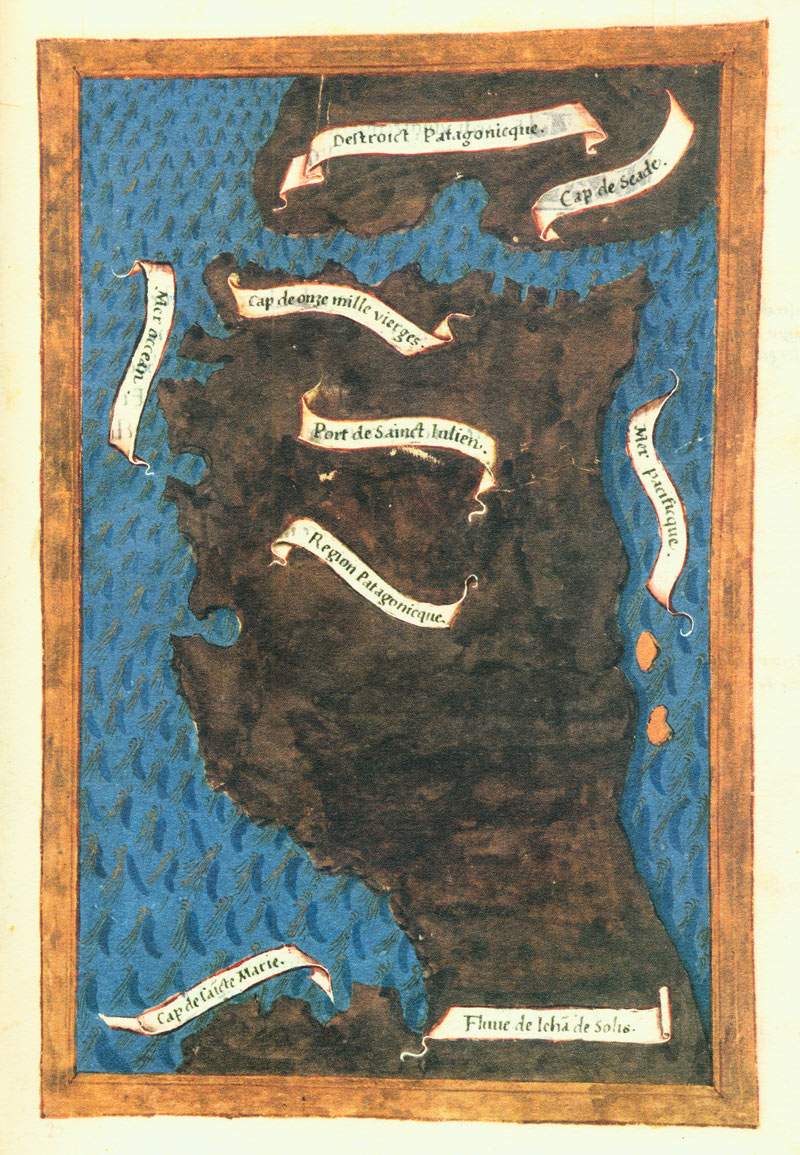

Обогнув южную оконечность Америки, он обнаружил пролив, названный позже Магеллановым, и архипелаг, который назвал Огненной Землёй. Пролив пересекли уже только три судна из пяти, так как одно погибло, а другое оставило Магеллана и вернулось в Испанию. В последующие (4) месяца экспедиция путешествовала по водам неведомого тогда океана. Поскольку в течение всего плавания океан был очень спокойным, мореплаватели назвали его Тихим. Океан оказался не просто большим, а огромным. Во время путешествия начался голод, моряки страдали от цинги.

Гибель Ф. Магеллана

Путешествие закончилось удачно: было доказано, что Земля имеет форму шара. Однако Фернан Магеллан не дожил до возвращения на родину: он погиб в пути. Путешественник был убит в стычке с туземцами на острове Мактан (Филиппины), где позднее ему был поставлен памятник в виде двух кубов, увенчанных шаром.

Хуан Себастьян де Элькано

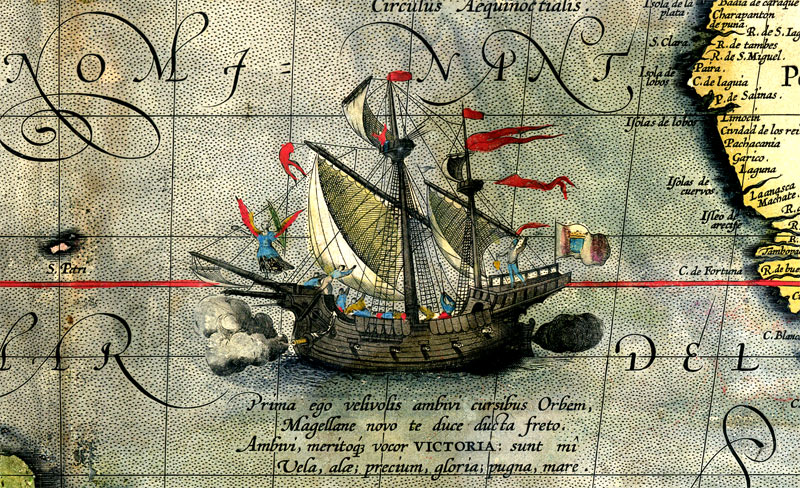

В итоге в Испанию вернулась только одна каракка — «Виктория» ((18) человек из (270)), которую возглавил Хуан Себастьян де Элькано. Так завершилось первое в истории кругосветное путешествие.

Современная копия Магелланова парусника «Виктория»

Итоги экспедиции:

- открытие Тихого океана;

- доказано единство Мирового океана;

- доказана шарообразность Земли;

- открытие большого количества островов в Тихом океане;

- уточнены очертания восточного побережья Южной Америки.

Источники:

Изображения:

Фернан Магеллан. Автор: неизвестного автора XVII века — журнал Вокруг света, 10-2007, страница 106, свой скан бумажной версии журнала, Общественное достояние, https://ru.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=873108.

Гибель Ф. Магеллана. Автор: Неизвестен — Laurence Bergreen: Poza krawedz swiata, Rebis, Poznan 2005, ISBN 83-7301-575-2, Общественное достояние, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11360813.

Хуан Себастьян де Элькано. Общественное достояние, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=658022.

Современная копия Магелланова парусника «Виктория». Автор: Gnsin — собственная работа, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=371163.

Отплытие

Идея экспедиции во многом являлась повторением идеи Колумба: достичь Азии, следуя на запад. Колонизация Америки еще не успела принести существенных прибылей в отличие от колоний португальцев в Индии, и испанцам хотелось самим плавать к Островам Пряностей и получать выгоду. К тому времени стало ясно, что Америка — это не Азия, но предполагалось, что Азия лежит сравнительно недалеко от Нового Света.

В марте 1518 года в Севилью в Совет Индии явились Фернан Магеллан и Руй Фалейру, португальский астроном, и заявили, что Молукки — важнейший источник португальского богатства — должны принадлежать Испании, так как находятся в западном, испанском полушарии (по договору 1494 г.), но проникнуть к этим «Островам пряностей» нужно западным путем, чтобы не возбудить подозрений португальцев, через Южное море, открытое и присоединенное Бальбоа к испанским владениям. И Магеллан убедительно доказывал, что между Атлантическим океаном и Южным морем должен быть пролив к югу от Бразилии.

После долгого торга с королевскими советниками, выговорившими себе солидную долю ожидаемых доходов и уступок со стороны португальцев, был заключен договор: Карл 1 обязался снарядить пять кораблей и снабдить экспедицию припасами на два года. Перед отплытием Фалейру отказался от предприятия, и Магеллан стал единоличным начальником экспедиции.

Магеллан сам лично следил за погрузкой и упаковкой продуктов, товаров и снаряжения. В качестве провизии были взяты на борт сухари, вино, оливковое масло, уксус, солёная рыба, вяленая свинина, фасоль и бобы, мука, сыр, мед, миндаль, анчоусы, изюм, чернослив, сахар, айвовое варенье, каперсы, горчица, говядина и рис. На случай столкновений имелось около 70 пушек, 50 аркебуз, 60 арбалетов, 100 комплектов лат и другое вооружение. Для торговли взяли материю, металлические изделия, женские украшения, зеркала, колокольчики и ртуть (ее использовали в качестве лекарства).

Магеллан поднял адмиральский флаг на «Тринидаде». Капитанами остальных судов были назначены испанцы: Хуан Картахена — «Сан-Антонио»; Гаспар Кесада — «Консепсьон»; Луис Мендоса — «Виктория» и Хуан Серрано — «Сантьяго». Штатный состав этой флотилии исчислялся в 293 человека, на борту находились еще 26 внештатных членов экипажа, среди них молодой итальянец Антонио Пигафетга, историк экспедиции. В первое кругосветное плавание отправился интернациональный коллектив: кроме португальцев и испанцев в его состав вошли представители более 10 национальностей из разных стран Западной Европы.

20 сентября 1519 года флотилия во главе с Магелланом вышла из порта Санлукар-де-Баррамеда (устье реки Гвадалквивир).

Конфликт в Атлантическом океане

Вскоре после отплытия на эскадре разгорелся конфликт. Капитаны других кораблей вновь стали требовать, чтобы Магеллан дал им разъяснения о маршруте. Но он отказался, заявив: «Ваша обязанность следовать днем за моим флагом, а ночью за моим фонарем». Вместо прямого пути к Южной Америке Магеллан повел флотилию близко к Африке. Вероятно, он пытался избежать возможной встречи с португальскими кораблями. Этот маршрут был довольно труден для плавания. Магеллан заранее разработал систему сигналов, позволявшую флотилии всегда держаться вместе. Каждый день корабли сходились на близкое расстояние для ежедневного рапорта и получения указаний.

Капитан «Сан-Антонио» Картахена, являвшийся представителем короны в плавании, во время одного из рапортов демонстративно нарушил субординацию и стал называть Магеллана не «капитан-генерал» (адмирал), а просто «капитан». В течение нескольких дней он продолжал это делать, несмотря на замечания Магеллана. После чего капитаны всех кораблей не были созваны на «Тринидад». Картахена снова нарушил дисциплину, но на этот раз он был не на своем судне. Магеллан лично схватил его за шиворот и объявил арестованным. Картахене разрешили находиться не на флагманском корабле, а на кораблях сочувствующих ему капитанов. Командиром «Сан-Антонио» стал родственник Магеллана Алвару Мишкита.

Зимовка

29 ноября флотилия достигла побережья Бразилии, а 26 декабря 1519 года — Ла-Платы, где проводились поиски предполагаемого пролива. «Сантьяго» был послан на запад, но вскоре вернулся с сообщением, что это не пролив, а устье гигантской реки. Эскадра начала медленно продвигаться на юг, исследуя берег. Продвижение на юг шло медленно, кораблям мешали штормы, близилась зима, а пролива все не было. 31 марта 1520 года, дойдя до 49° ю. ш., флотилия встает на зимовку в бухте, названной Сан-Хулиан.

Встав на зимовку, капитан распорядился урезать нормы выдачи продовольствия, что вызвало ропот среди моряков, уже измотанных длительным сложным плаванием. Этим попыталась воспользоваться группа офицеров, недовольных Магелланом.

1 апреля, в Вербное воскресенье, Магеллан пригласил всех капитанов на церковную службу и праздничный обед. Капитан Виктории Мендоса и капитан Консепсьона Кесадо на обед не являются. В ночь на 2 апреля начался мятеж. Бунтовщики освободили находившегося на их кораблях Картахену и решили захватить «Сан-Антонио», чьим капитаном раньше он был. Они подплыли к «Сан-Антонио», захватили спящего капитана Мишкиту и заковали его в цепи. Кормчего Хуана де Элорьягу, пытавшегося оказать сопротивление, Кесадо убил ножом. Командование «Сан-Антонио» было поручено Себастьяну Элькано.

Магеллан узнал про мятеж только утром. В его распоряжении осталось два корабля — «Тринидад» и «Сантьяго», почти не имевший боевой ценности. В руках же заговорщиков три крупных корабля — «Сан-Антонио», «Консепсьон» и «Виктория». Но мятежники не желали дальнейшего кровопролития, опасаясь, что им за это придется отвечать по прибытии в Испанию. К Магеллану была послана шлюпка с письмом в котором говорилось, что их цель — всего лишь заставить Магеллана правильно выполнить приказы короля. Они согласны считать Магеллана капитаном, но он должен советоваться с ними по всем своим решениям и не действовать без их согласия. Для дальнейших переговоров они приглашают Магеллана прибыть к ним для переговоров. Магеллан в ответ приглашает их на свой корабль. Те отказываются.

Усыпив бдительность противника, Магеллан захватил шлюпку, перевозившую письма. Мятежники больше всего опасались удара по «Сан-Антонио», но Магеллан решил напасть на «Викторию», где находилось много португальцев. Шлюпка, в которой находился Гонсало Гомес де Эспиноса и пять надежных людей, отправился «Виктории». Поднявшись на корабль, Эспиноса вручил капитану Мендосе новое приглашение от Магеллана прибыть на переговоры. Капитан начал читать. Но Эспиноса нанес ему удар ножом в шею, а один из прибывших матросов добил мятежника. Пока команда «Виктории» пребывала в полной растерянности, на борт вскочила еще одна, на этот раз хорошо вооруженная группа сторонников Магеллана во главе с Дуарте Барбозой, незаметно подошедшая на другой шлюпке. Экипаж «Виктории» сдался без сопротивления. Три корабля Магеллана — «Тринидад», «Виктория» и «Сантьяго» — встали у выхода из бухты, перекрывая мятежникам путь к бегству. После того, как у них отняли корабль, мятежники не решились вступить в открытое столкновение и, дождавшись ночи, попытались проскользнуть мимо кораблей Магеллана в открытый океан. Это не удалось. «Сан-Антонио» был обстрелян и взят на абордаж. Сопротивления не было, жертв тоже. Вслед за ним сдался и «Консепсьон».

Для суда над мятежниками был создан трибунал. 40 участников мятежа были приговорены к смерти, но тут же помилованы, поскольку экспедиция не могла терять такое количество матросов. Был казнён только совершивший убийство Кесадо. Представителя короля Картахену и одного из священников, активно участвовавшего в мятеже, Магеллан казнить не решился, и они были оставлены на берегу после ухода флотилии. О их дальнейшей судьбе ничего не известно.

Магелланов пролив

В мае Магеллан послал «Сантьяго» во главе с Жуаном Серраном на юг для разведки местности. В 60 милях к югу была найдена бухта Санта-Крус. Ещё через несколько дней в бурю корабль потерял управление и разбился. Моряки, кроме одного человека, спаслись и оказались на берегу без пищи и припасов. Они пытались вернуться к месту зимовки, но из-за усталости и истощения соединились с основным отрядом только через несколько недель. Потеря судна, специально предназначенного для разведки, а также припасов, находящихся на нём, нанесла большой ущерб экспедиции. Магеллан сделал Жуана Серрана капитаном «Консепсьона». В результате все четыре корабля оказались в руках сторонников Магеллана. «Сан-Антонио» командовал Мишкита, «Викторией» — Барбоза.

24 августа 1520 года флотилия вышла из бухты Сан-Хулиан. За время зимовки она лишилась 30 человек. Уже через два дня экспедиция вынуждена была остановиться в бухте Санта-Крус из-за непогоды и повреждений. В путь флотилия вышла только 18 октября. Перед выходом Магеллан объявил, что будет искать пролив вплоть до 75° ю. ш., если же пролив не обнаружится, то флотилия пойдет к Молуккским островам вокруг мыса Доброй Надежды.

21 октября под 52° ю. ш. корабли оказались у узкого пролива ведущего в глубь материка. «Сан-Антонио» и «Консепсьон» посылаются на разведку. Вскоре налетела буря, длившаяся два дня. Моряки опасались, что посланные на разведку корабли погибли. И они действительно чуть не погибли, но когда их понесло к берегу, перед ними открылся узкий проход, в который они вошли. Они оказались в широкой бухте, за которой последовали еще проливы и бухты. Вода все время оставалась соленой, а лот очень часто не доставал дна. Оба судна вернулись с радостной вестью о том, что, возможно, пролив найден.

Флотилия вошла в пролив и много дней шла по настоящему лабиринту скал и узких проходов. Пролив впоследствии был назван Магеллановым. Южную землю, на которой ночами часто виделись огни, назвали Огненной Землей. У «реки Сардин» был созван совет. Кормчий «Сан-Антонио» Эстебан Гомиш высказался за возвращение домой из-за малого количества провианта и полной неизвестности впереди. Другие офицеры не поддержали его. Магеллан объявил, что корабли пойдут вперёд.

У острова Доусон пролив делится на два канала, и Магеллан снова разделяет флотилию. «Сан-Антонио» и «Консепсьон» идут на юго-восток, два других корабля остаются для отдыха, а на юго-запад отправляется лодка. Через три дня лодка вернулась и моряки сообщили, что видели открытое море. Вскоре вернулся «Консепсьон», но от «Сан-Антонио» не было известий. Пропавший корабль искали несколько дней, но безрезультатно. Позже выяснилось, что кормчий «Сан-Антонио» Эстебан Гомеш поднял мятеж, заковал в цепи капитана Мишкиту и ушёл домой в Испанию. В марте он вернулся в Севилью, где обвинил Магеллана в измене.

28 ноября 1520 года корабли Магеллана вышли в океан. Путь по проливу занял 38 дней.

Тихий океан

Итак, Магеллан вышел из пролива и повел оставшиеся три корабля сначала на север, стараясь поскорее покинуть холодные высокие широты и держась примерно в 100 км от скалистого побережья. 1 декабря он прошел близ п-ова Тайтао (у 47° ю. ш.), а затем суда удалились от материка — 5 декабря максимальное расстояние составило 300 км. 12— 15 декабря Магеллан вновь довольно близко подошел к берегу у 40° и 38°30′ ю. ш., т. е. не менее чем в трех точках видел высокие горы — Патагонскую Кордильеру и южную часть Главной Кордильеры. От о. Моча (38°30′ ю. ш.) суда повернули на северо-запад, а 21 декабря, находясь у 30° ю. ш. и 80° з. д.,—на запад-северо-запад.

Нельзя, конечно, говорить, что во время своего 15-дневного плавания на север от пролива Магеллан открыл побережье Южной Америки на протяжении 1500 км, но он по крайней мере доказал, что в диапазоне широт от 53° 15′ до 38°30′ ю. ш. западный берег материка имеет почти меридиональное направление.

Флотилия прошла по Тихому океану не менее 17 тыс. км. Такие огромные размеры нового океана оказались неожиданными для моряков. При планировании экспедиции исходили из предположения, что Азия находится сравнительно близко от Америки. Кроме того, в то время считалось, что основную часть Земли занимает суша, и только сравнительно небольшую — море. Во время пересечения Тихого океана стало ясно, что это не так. Океан казался бескрайним. Не готовая к такому переходу, экспедиция испытывала огромные лишения. На кораблях свирепствовала цинга. Погибло, по разным источникам, от одиннадцати до двадцати девяти человек. К счастью для моряков, за все время плавания не было ни одной бури и они назвали новый океан Тихим.

Во время плавания экспедиция дошла до 10° с. ш. и оказалась заметно севернее Молуккских островов, к которым стремилась. Возможно, Магеллан хотел убедиться, что открытое Бальбоа Южное море является частью этого океана, а, возможно, он опасался встречи с португальцами, которая для его потрепанной экспедиции закончилась бы плачевно. 24 января 1521 года моряки увидели необитаемый остров (из архипелага Туамоту). Высадиться на него не представлялось возможности. Через 10 дней был обнаружен еще один остров (в архипелаге Лайн). Высадиться тоже не удалось, но экспедиция наловила акул для пропитания.

Воровские острова и остров Хомонхом

6 марта 1521 года флотилия увидела остров Гуам из группы Марианских островов. Он был населен. Лодки окружили флотилию, началась торговля. Вскоре выяснилось, что местные жители воруют с кораблей все, что попадется под руку. Когда они украли шлюпку, европейцы не выдержали. Они высадились на остров и сожгли селение островитян, убив при этом 7 человек. После этого они забрали лодку и захватили свежие продукты. Острова были названы Воровскими (Ландронес). При уходе флотилии местные жители преследовали корабли на лодках, забрасывая их камнями, но без особого успеха.

Через несколько дней испанцы первыми из европейцев достигли Филиппинских островов, которые Магеллан назвал архипелагом Святого Лазаря. Опасаясь новых столкновений, он нашел необитаемый остров. 17 марта испанцы высадились на острове Хомонхом. Переход через Тихий океан закончился.

На острове Хомонхом был устроен лазарет, куда перевезли всех больных. Свежая пища быстро вылечила моряков, и флотилия отправилась в дальнейший путь среди островов. На одном из них раб Магеллана Энрике, родившийся на Суматре, встретил людей, говорящих на его языке.

Битва при Мактане. Смерть Магеллана

7 апреля 1521 года экспедиция вошла в порт Себу на одноименном острове. Там они встретили порядки настоящего «цивилизованного» мира. Местный правитель, раджа Хумабон, начал с того, что потребовал от них уплаты пошлины. Платить Магеллан отказался, но предложил ему дружбу и военную помощь, если тот признает себя вассалом испанского короля. Правитель Себу принял предложение и через неделю даже крестился вместе со своей семьей и несколькими сотнями подданных.

В роли покровителя новых христиан Магеллан вмешался в междоусобную войну правителей островка Мактан, расположенного против города Себу. В ночь на 27 апреля 1521 года он отправился туда с 60 людьми на лодках, но они из-за рифов не могли подойти близко к берегу. Магеллан, оставив в лодках арбалетчиков и мушкетеров, с 50 людьми переправился вброд на островок. Там, у селения, их ожидали и атаковали три отряда. С лодок начали стрельбу по ним, но стрелы и даже мушкетные пули на таком расстоянии не могли пробить деревянных щитов нападающих. Магеллан приказал поджечь селение. Это разъярило мактанцев, и они стали осыпать чужеземцев стрелами и камнями и кидать в них копья. «…Наши, за исключением шести или восьми человек, оставшихся при капитане, немедленно бросились в бегство… Узнав капитана, на него накинулось множество людей… но все же он продолжал стойко держаться. Пытаясь вытащить меч, он обнажил его только до половины, так как был ранен в руку… Один ранил его в левую ногу… Капитан упал лицом вниз, и тут его закидали… копьями и начали наносить удары тесаками, до тех пор, пока не погубили… Он все время оборачивался назад, чтобы посмотреть, успели ли мы все погрузиться в лодки» (Пигафетта). Кроме Магеллана, погибли восемь испанцев и четверо союзных островитян. Среди моряков имелось немало раненых.

В результате поражения погибло девять европейцев, но ущерб репутации был огромен. Кроме того, сразу же дала себя знать потеря опытного руководителя. Вставшие во главе экспедиции Жуан Серран и Дуарте Барбоза вступили в переговоры с Лапу-Лапу, предлагая ему выкуп за тело Магеллана, но тот ответил, что тело не будет выдано ни при каких условиях. Неудача переговоров окончательно подорвала престиж испанцев, и вскоре их союзник Хумабон заманил их на обед и устроил резню, убив несколько десятков человек, в том числе почти весь командный состав. Кораблям пришлось срочно отплыть.

Молуккские острова

Флотилия достигла Молуккских островов лишь 8 ноября. Малайский моряк привел суда к рынку пряностей на о. Тидоре, у западного берега Хальмахеры, самого большого из Молуккских островов. Здесь испанцы дешево закупили пряности — корицу, мускатный орех, гвоздику.

На островах испанцы узнали, что португальский король объявил Магеллана дезертиром, поэтому его суда подлежали взятию в плен. Суда обветшали. «Консепсьон» был ранее оставлен командой и сожжён. Оставалось только два корабля. «Тринидад» был отремонтирован и отправился на восток к испанским владениям в Панаме, а «Виктория» — на запад в обход Африки. «Тринидад» попал в полосу встречных ветров, был вынужден возвратиться к Молуккским островам и был захвачен в плен португальцами. Большинство его экипажа погибло на каторге в Индии.

Острова Зелёного мыса

«Виктория» под командованием Хуана Себастьяна Элькано продолжила маршрут. Экипаж был пополнен некоторым числом островитян-малайцев (почти все из них погибли в дороге). На корабле вскоре стало не хватать провизии, и часть экипажа стала требовать от капитана взять курс на принадлежащий португальской короне Мозамбик и сдаться в руки португальцев. Однако большинство моряков и сам капитан Элькано решили любой ценой попытаться доплыть до Испании. «Виктория» с трудом обогнула мыс Доброй Надежды и затем два месяца без остановок шла на северо-запад вдоль африканского побережья.

9 июля 1522 года изношенный корабль с измождённым экипажем подошёл к островам Зелёного мыса, португальскому владению. Не сделать здесь остановки было невозможно по причине крайнего недостатка питьевой воды и провизии. Им удалось получить две груженные рисом лодки. Однако португальцы все-таки задержали тринадцать человек экипажа, и «Виктория» ушла без них.

Возвращение в Испанию

6 сентября 1522 года «Виктория» добралась до Испании, став, таким образом, единственным кораблём флотилии Магеллана, победно вернувшимся в Севилью. На корабле было восемнадцать выживших. Но «Виктория» привезла столько пряностей, что продажа их с лихвой покрыла затраты на экспедицию, а Испания получила «право первого открытия» на Марианские и Филиппинские о-ва и предъявила претензии на Молукки.

Позже, в 1525 году, ещё четверо из 55 членов команды корабля «Тринидад» были доставлены в Испанию. Также были выкуплены из португальского плена те члены команды «Виктории», которые были схвачены португальцами во время вынужденной стоянки на островах Зелёного Мыса.

Фернан Магеллан

Краткая биография

Португальский и испанский мореплаватель Фернан Магеллан (Магальяйнш) родился в португальской дворянской семье в 1480 г. Известно, что Фернан рано стал сиротой и мальчиком служил пажом при дворе королевы Элеоноры. Затем Фернан учился в знаменитой мореходной школе, основанной принцем Энрике Мореплавателем, а после ее окончания принимал участие в португальских морских разведывательных экспедициях в Индийском океане.

Фернан Магеллан возглавлял экспедицию, которая совершила первое кругосветное плавание. Корабль под его командованием первым из европейских кораблей проследовал из Атлантического в Тихий океан по ранее неизвестному европейцам проливу между южной оконечностью материка Южная Америка и архипелагом Огненная Земля. Позже этот пролив был назван именем Магеллана. 27 апреля 1521 г. на острове Мактан в архипелаге Филиппинских островов Магеллан был убит аборигенами.

Первая кругосветная экспедиция

В марте 1518 г. перед испанским Советом по делам Индий предстал португальский мореплаватель Фернан Магеллан. Он заявил, что готов отыскать новый путь к желанным Молуккским островам – истинной родине пряностей, пройдя через известный ему пролив из Атлантики в Южное море. Магеллан обещал испанским монархам опередить португальцев, которые приближались к этой земле с востока – из Индийского океана. К этому времени (в 1498 г.) португалец Васко да Гама открыл морской путь в Индию. Теперь, огибая Африку, португальские корабли постепенно продвигались на восток, к архипелагу Зондских и Молуккских островов. Надо сказать, что Магеллан предлагал свой план и португальскому королю Мануэлу, но он показался монарху слишком авантюрным и был отвергнут. А испанцы поверили дерзкому португальцу: испанский король Карл I приказал снарядить флотилию из пяти кораблей.

В инструкции, которую дал испанский король Карл I Магеллану, было сказано: «Поскольку мне доподлинно известно, что на островах Молукко имеются пряности, я посылаю вас главным образом на их поиски, и моя воля такова, чтобы вы направились прямо на эти острова».

20 сентября 1519 г. «Сан-Антонио», «Тринидад», «Виктория», «Сантьяго» и «Консепсьон» с командой из 265 человек вышли из Испании. В январе 1520 г. они достигли устья реки Ла-Платы на южноамериканском континенте и продолжили путь вдоль побережья материка, обследовав около 2000 км. В поисках пролива корабли заходили во все бухты, были открыты заливы Сан-Матиас и Сан-Хорхе на земле, которую Магеллан назвал Патагонией. В марте 1520 г. в бухте Сан-Хулиан, где зазимовала экспедиция, на трех судах вспыхнул мятеж. Испанские моряки опасались предстоящих трудностей и не желали подчиняться португальцу.

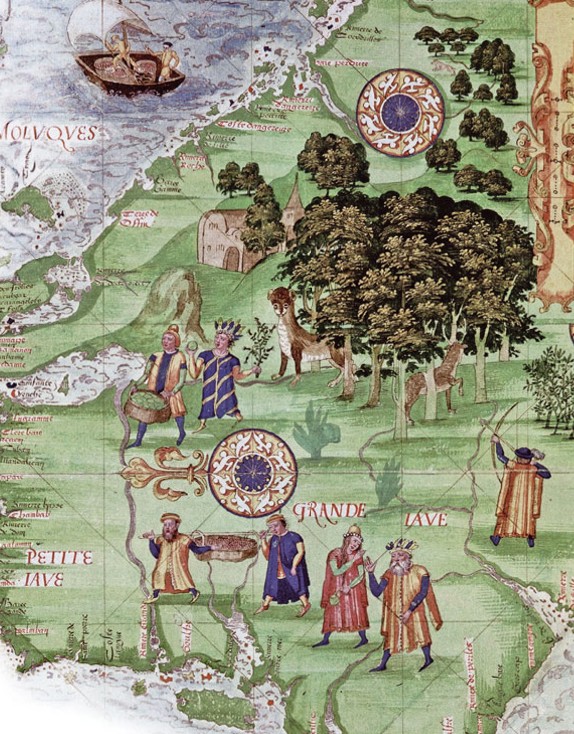

Ф. Галле. Аллегория плавания Магеллана вокруг света. XVI в.

На фрагменте старинной карты изображен Магелланов пролив

Магеллан подавил мятеж и в августе двинулся дальше на юг на четырех кораблях («Сантьяго» разбился). 21 октября 1520 г. корабли вошли в пролив, названный капитаном проливом Всех Святых (позднее его переименовали в Магелланов). Следуя по нему, мореплаватель обнаружил к югу архипелаг Огненная Земля. Маневрировать в узком извилистом проливе оказалось очень непросто, экипаж корабля «Сан-Антонио» взбунтовался и повернул обратно в Испанию.

28 ноября 1520 г. Магеллан на трех оставшихся кораблях вышел в огромный неизвестный океан – Южное море. Плавание, которое продолжалось более трех месяцев, было на удивление спокойным, мореплаватели страдали лишь от недостатка провизии и пресной воды. За «кроткий нрав» океану дали имя «Тихий». Корабли прошли по его водам более 17 000 км. В марте 1521 г. Магеллан открыл три острова из Марианского архипелага, а затем Филиппинские острова (Самар, Минданао и Себу). Все вновь открытые земли он провозглашал владениями испанского короля. 27 апреля 1521 г. Магеллан вмешался в спор двух местных правителей и был убит туземцами на острове Мактан (Филиппины).

Корабль Магеллана «Виктория». Фрагмент карты Ортелия. XVI в.

Маршрут первого кругосветного плавания экспедиции Ф. Магеллана 1519-1521 гг. Крестом обозначено место гибели Ф. Магеллана в 1521 г.

После смерти Магеллана экспедицию возглавил испанец Хуан Себастьян Элькано. Находясь недалеко от конечной цели путешествия, флотилия потратила несколько месяцев, петляя в островном лабиринте. Наконец, «Тринидад» и «Виктория» бросили якорь у Молуккских островов («Консепсьон» обветшал и его сожгли). Ожидания испанцев оправдались: здесь им удалось закупить столько пряностей, что доходы от их продажи в Португалии с лихвой покрыли все издержки экспедиции. Морякам предстоял обратный путь на родину. Решено было отправить «Тринидад» через Тихий океан к Панаме, где находились испанские владения, а «Виктория» взяла курс на запад – к африканскому континенту.

Хуан Себастьян Элькано. Неизвестный художник. XVII в.

Через некоторое время «Тринидад» из-за сильных встречных ветров вынужден был повернуть назад, и был захвачен в плен португальцами. Большинство моряков затем погибли на каторге в Индии. В это время «Виктория» под командованием Элькано упорно следовала в Испанию. Обойдя мыс Доброй Надежды, корабль с голодной измученной командой с большой осторожностью двигался вдоль африканского континента. Испанцы опасались попасть на глаза португальцам, которые контролировали эти воды. Попадись им «Виктория», корабль непременно бы разграбили, а с командой расправились. И все же пресной воды и съестных запасов было так мало, что «Виктория» рискнула остановиться на португальских островах Зеленого Мыса. Для португальцев придумали легенду, что корабль потерпел крушение у экватора и нуждается в пополнении припасов. Однако португальцы заподозрили неладное и задержали испанскую лодку с моряками, тогда «Виктория» спешно отошла от островов.

Обидно было бы теперь, когда до цели осталось несколько месяцев пути, попасть в плен к португальцам и перечеркнуть все замечательные достижения кругосветного плавания. Надо сказать, что Магеллан не планировал плыть вокруг земного шара, он получил от испанского короля приказ возглавить коммерческую экспедицию и собирался после достижения Молуккских островов вернуться тем же путем в Испанию. Элькано же сознательно продолжал путь на запад, выбрав кругосветный маршрут из Юго-Восточной Азии в Испанию.

Навигационные инструменты. XV–XVI вв.

В сентябре 1522 г. «Виктория», единственная из пяти кораблей флотилии Магеллана, добралась до берегов Испании. На борту было всего 18 выживших мореплавателей. Позже четверых из 55 членов команды «Тринидада» освободили и доставили в Испанию, а также выкупили из португальского плена 13 членов команды, которых оставили в лодке у островов Зеленого Мыса.

Капитан «Виктории» Хуан Себастьян Элькано (испанец баскского происхождения) был обласкан испанским монархом. Элькано отправился в экспедицию Магеллана, спасаясь от разорения и тюрьмы, а вернулся настоящим героем. Карл I наградил Элькано личным гербом, на котором был изображен земной шар и начертаны слова: «Ты первый обогнул меня», а также назначил ежегодную пенсию. Участвуя в следующем плавании (в 1526 г.) к «островам пряностей» под командованием адмирала Лоаиса, которое оказалось чрезвычайно изнурительным, Элькано умер.

Молуккские острова выкупил у испанцев португальский король за 350 тысяч золотых дукатов.

Торговля пряностями на Молуккских островах. Фрагмент карты из атласа «Всемирная космография». XVI в.

Вклад в географию

Магеллан и Элькано совершили первое кругосветное путешествие и на практике доказали шарообразность Земли. Открыли западный путь из Европы к восточным берегам Евразии и «островам пряностей». Впервые был пройден Тихий океан.

Читайте также

- Фернан Магеллан и его первое кругосветное путешествие

- Путешествие Васко да Гама в Индию

- Христофор Колумб и его открытие Америки

Поделиться ссылкой

27 апреля 1521 года на крошечном острове Мактан (Филиппинские острова) в ненужной и совершенно бесполезной потасовке с местными туземцами был убит Фернан Магеллан — величайший мореплаватель, задумавший и практически осуществивший первое кругосветное плавание. Произошло это в те времена, когда люди лишь отдаленно представляли себе истинные размеры земного шара, не знали, где расположены материки, сообщаются ли между собой океаны, а ориентировались по Солнцу и звездам. Следующая кругосветка состоялась лишь через 60 лет. Историю Фернана Магеллана, трагически завершившего свой путь ровно 500 лет назад, читайте в материале «Ленты.ру»

Многие представляют себе великих путешественников, мореплавателей и первооткрывателей как упертых романтиков, рискующих собой и товарищами ради прогресса и счастья всего человечества, ну, или из гордости, тщеславия и жажды славы. Ничего подобного. Для того чтобы лично попасть в книгу рекордов, нужно всего лишь съесть больше всех гамбургеров или много лет не бриться. А вот чтобы открыть Америку или первому обойти вокруг света, необходимо сперва убедить приличных размеров государство в финансовой целесообразности такого подвига. А это получается не всегда.

Эпоха великих географических открытий. Колумб объявляет открытую им землю собственностью испанского короля. Иллюстрация 1893 года

Изображение: L. Prang & Co., Boston / Библиотеки Конгресса США

«И последние станут первыми»

Почему король Португалии Жуан II не услышал Христофора Колумба, а 33 года спустя другой португальский монарх Мануэл I так же безразлично отверг Фернана Магеллана? Все очень просто. У Португалии к этому времени все и так было хорошо.

Находящаяся на задворках европейской цивилизации, граничащая по суше лишь с Испанией (а гордые испанцы и тогда, и до сих пор относятся к португальцам с изрядным презрением), маленькая, бедная Португалия была отрезана от Средиземного моря, по которому в течение полутора тысяч лет проходили главные морские и торговые пути человечества. Такой вот парадокс — половину страны занимает океанское побережье, а идти и некуда.

Но что значит некуда, а как же западное побережье Африки? И португальцы начинают вначале робко, а затем все смелее и смелее спускаться на юг. За бесплодными песками Сахары они открывают новые земли, богатые белой слоновой костью и черными невольниками. В 1471 году португальские корабли достигают экватора, в 1484-м устья Конго, а через два года Бартоломеу Диаш добирается до южной оконечности Африки и обнаруживает, что материк не примерз к Южному полюсу, как считал еще Птолемей, а проход в Индийский океан свободен.

Географические открытия, лоции и отчеты об экспедициях держатся в строжайшем секрете. 13 ноября 1504 года король издает указ:

Под страхом смертной казни запрещающий сообщать какие-либо сведения о судоходстве по ту сторону реки Конго, дабы чужестранцы не могли извлечь выгоды из открытий, сделанных Португалией

Король понимает, если все делать правильно, Португалия может стать сказочно богатой. И для этого есть все основания.

В 1453 году пал Константинополь. Под напором турок Византийская империя прекратила существование. Теперь все торговые пути с Востока на Запад контролируются мусульманами. Арабские, египетские, турецкие, да еще и венецианские перекупщики заоблачно поднимают цены на товары, без которых продвинутая Европа уже не представляет своей повседневной жизни. Перец, мускатный орех, имбирь, корица, хина, камфора, опиум, а также индийский жемчуг, китайский шелк и фарфор и другие драгоценные дары Востока многократно растут в цене.

1510 год. Радостные туземцы встречают португальские корабли

Изображение: Hulton Archive / Getty

Но если найти морской путь в Индию, Китай и на Острова пряностей, где перец растет, что нынче борщевик в Тверской области — то есть повсеместно, в изобилии и сам по себе, то можно обогатиться сказочно. Это знает король Португалии Жоан II. И когда к нему приходит неизвестный генуэзец с фантастическим предложением идти в Индию через Атлантику, король ему отказывает. Зачем тратить деньги на сомнительную авантюру, когда путь вокруг Африки уже открыт, секретные карты отпечатаны, флот строится. Более того, предусмотрительные португальцы уже получили у римского папы эксклюзивное право на владение всеми открытыми землями в Африке и на востоке, но не на западе.

Упорный Колумб отправляется в Испанию и находит там спонсоров для своего сумасшедшего предприятия. В 1492 году эскадра из трех судов с запасом продовольствия на год уходит на Запад. Неожиданно Атлантика оказывается не такой уж и бесконечной. Не повстречав кракенов и не сорвавшись с края земли, Колумб достигает суши всего за 36 дней. Он уверен, что это Азия и, если пройти еще немного на запад, то через несколько дней можно будет высадиться в устье Ганга.

Португалия в шоке. Западный путь в Индию оказывается в четыре раза короче и безопаснее. В 1493 году Папа Александр VI Борджиа отдает Испании все земли, которые будут открыты на Западе. Испания лихорадочно строит корабли и отправляет их через Атлантику. Но ни пряностей, ни китайских шелков, ни драгоценных камней во вновь открытых землях нет. Нет даже невольников, потому что тщедушные туземцы слабы и не выдерживают длительных морских переходов. Становится очевидно, что открытая Колумбом земля вовсе не Индия, а новый континент, с которым нужно еще разбираться.

Между тем уже в 1498 году Васко да Гама обходит Африку, достигает Индии и возвращается обратно. Несмотря на значительные потери, выручка от привезенных им товаров в 60 раз превышает расходы на экспедицию. Португальцы оперативно овладевают ключевыми пунктами вдоль африканского побережья и в самой Индии, громят объединенный египетско-индийский флот и устанавливают полный контроль над морскими и торговыми путями через Индийский океан. Крошечная Португалия стремительно становится владычицей морей.

Фернан Магеллан. Портрет работы неизвестного художника XVII века. Галерея Уффици, Флоренция

Человек тяжелый и малосимпатичный

Всего за какие-то 25 лет границы известного европейцам мира раздвигаются на тысячи и тысячи километров на запад, восток, север и юг. В сентябре 1513 года Васко Нуньес де Бальбоа пересекает Панамский перешеек и первым из европейцев видит еще один великий океан. Все это внушает оптимизм. В матросы вербуются целыми деревнями. Но покуда Франсиско Писарро еще не разграбил сокровища инков и не началась разработка Потосийских серебряных рудников, коммерческой ценности открытые испанцами земли не представляют.

Дорогие заморские экспедиции себя не окупают. Нужно двигаться дальше в вожделенную Индию и на Острова пряностей (Молуккские острова). Испанцы тщетно ищут западный морской проход, но натыкаются лишь на огромный материк, который, как кажется, невозможно обойти ни с севера, ни с юга. И тут при дворе испанского короля Карла V появляется португальский дворянин, закаленный в боях солдат и опытный моряк Фернан де Магальянеш.

Фернан де Магальянеш, или, как его принято называть, Фернан Магеллан, происходил из небогатого дворянского рода. В юности, предположительно, был придворным пажом королевы Элеоноры и получил неплохое образование. В 24 года фидальго поступил в военный флот, но всего лишь рядовым воином. В 1505 году принял участие в первом военном походе португальцев в Индию. Во время знаменитого сражения при Диу, когда одиннадцати большим португальским кораблям противостоял объединенный египетско-индийский флот из 200 кораблей, был ранен. В 1509 году проявил завидную храбрость в сражении у Малакки (Малайзия), буквально в последний момент предупредив командующего эскадрой о готовящемся нападении, а затем был единственным, кому удалось прорваться на лодке к берегу и спасти нескольких товарищей.

Был еще дважды ранен и получил младший офицерский чин. После службы на Востоке вернулся в Португалию, где ему положили унизительно малую пенсию. В 1513 году отправился в военную экспедицию в Марокко, вновь был ранен. Копье повредило колено, после чего Магеллан стал заметно хромать.

Вернувшись в Лиссабон, Магеллан добился аудиенции короля Мануэла I. У него уже был план, как доплыть до Молуккских островов западным путем, но прежде чем его озвучить, он попросил об увеличении содержания и принятии на службу во флот. И на обе просьбы получил отказ. После этого испросил разрешения предложить свои услуги другим государям. Мануэл не возражал. Магеллан — опытный воин и один из лучших знатоков морского дела того времени — слыл при дворе человеком тяжелым и малосимпатичным.

Каракка «Виктория». Фрагмент карты Ортелиуса 1590 года

Изображение: деталь карты Ортелиуса

Вот как характеризует Магеллана австрийский писатель Стефан Цвейг в яркой биографии мореплавателя («Подвиг Магеллана», 1938):

«Как ни мало мы о нем знаем, одно остается бесспорным: этот низкорослый, смуглый, малозаметный, молчаливый человек даже в самой малой степени не обладал даром привлечь к себе симпатии (…)»

Неразговорчивый, замкнутый, всегда укутанный пеленой одиночества, этот нелюдим, должно быть, распространял вокруг себя атмосферу ледяного холода, стеснения и недоверия, и мало кому удавалось узнать его даже поверхностно, а во внутреннюю его сущность так никто и не проник

В молчаливом упорстве, с которым он оставался в тени, его товарищи бессознательно чуяли какое-то необычное, непонятное честолюбие, тревожащее их сильнее, чем честолюбие откровенных охотников за выгодными местами, ожесточенно теснящихся у казенной кормушки.

В его глубоких, маленьких, сверлящих глазах, в углах его густо заросшего рта всегда витала какая-то надежно спрятанная тайна, заглянуть в которую он не позволял. А человек, прячущий в себе тайну и достаточно стойкий, чтобы много лет держать ее за зубами, всегда страшит тех, кто от природы доверчив, кому нечего скрывать.

Тайный проход между океанами

А скрывать Магеллану было что. Почти год он, не вызывая подозрения, изучал в Tesoraria — секретном архиве короля Маноэла — отчеты экспедиций в Новый свет, судовые журналы, разбирал и копировал карты, лоции и лаговые записи последних экспедиций в Бразилию. Часами просиживал в кабачках с капитанами и кормчими, побывавшими в южных морях. Свел близкое знакомство с лучшим астрономом своего времени Руйем Фалейро, также не принятым ко двору. Ну а чем еще должен заниматься бывший моряк?!

Рую Фалейро Магеллан открыл свою великую тайну — где-то на 38-м примерно градусе южной широты находится пролив, соединяющий океаны. Об этом он узнал благодаря карте, начертанной знаменитым придворным картографом Мартином Бехаймом и хранившейся в секретном королевском архиве. Эта карта была составлена на основании результатов нескольких португальских экспедиций, обследовавших побережье Бразилии и, возможно, Аргентины. В одной из них принимал участие Америго Веспуччи.

Карта 1561 года, на которой изображен американский континент

Изображение: Wikipedia

Как позже оказалось, за пролив между океанами тогда приняли широкое устье реки Ла-Платы. Но Магеллан этого не знал и был уверен, что его данные верны. Фалейро сделал расчеты (также неверные), и у него вышло, что Острова пряностей находятся в западном полушарии, а значит, исходя из буллы Папы Александра VI, должны по праву принадлежать не Португалии, а Испании.

И вот с таким багажом, за который Магеллана могли бы с полным правом отправить на родине на гарроту, спустя полтора года после неудачной аудиенции у Мануэла упрямый и скрытный португалец отправился к испанскому двору.

Прием у малинового короля

Магеллан умел ждать и терпеть. Португалец понимал, что у него будет не больше одной попытки, и основательно подготовился. Приехав в Севилью, он женился на дочке своего земляка Дього Барбозы, уже давно перебравшегося в Испанию и занимавшего прочное положение при испанском дворе. С помощью тестя Магеллан завел нужные знакомства.

К моменту аудиенции у Карла V члены Casa de Contractacion — Индийской торговой палаты — были уже подготовлены, а ее фактор (управляющий) Хуан де Аранда заключил с просителями личное соглашение на одну восьмую всех будущих доходов с предприятия в обмен за содействие и участие в финансировании.

Магеллан продемонстрировал испанскому королю восторженные письма своего товарища, обосновавшегося на Островах пряностей, одного из тех, кого он в свое время спас в сражении у Малакки, показал слугу — живого малайца Энрике, а на главное блюдо — карты и лоции предполагаемого прохода в Тихий океан, которые он раздобыл в секретных архивах Лиссабона.

Фалейро, со своей стороны, продемонстрировал математические расчеты, из которых следовало, что вожделенные острова расположены в зоне, которую его святейшество папа предоставил Испании. А поскольку португальцы контролируют путь вокруг Африки, единственная возможность воспользоваться своим законным правом на них — это дойти туда западным путем.

Все было решено быстро.

Эскадра Магеллана

Изображение: Álvaro Casanova Zenteno

Королева карта бита

20 сентября 1519 года флотилия из пяти кораблей — адмиральский флагман «Тринидад», «Консепсьон», «Виктория», «Сан-Антонио» и «Сантьяго» — уходят в плавание, которое станет самым протяженным из всех, что были когда-либо.

Переход через Атлантику уже не являлся чем-то необычным, но эскадра попадает в полосу штилей. Неделями корабли стоят без движения под палящим солнцем. Из-за скуки и однообразия возникают первые проблемы. Чванливые испанские капитаны недовольны тем, что ими руководит презренный португалец, да еще и незнатного рода. Происходят мелкие стычки.

Но вот долгожданный ветер наполняет паруса, и общее настроение улучшается. Эскадра идет на юг вдоль побережья Американского континента. 10 января на равнинном берегу мореплаватели замечают холм, который называют Монтевиди (современный Монтевидео — столица Уругвая). Чтобы укрыться от свирепого шторма, корабли заходят в обширный залив, тянущийся далеко на запад вглубь континента. Магеллан ликует, это и есть тот самый проход в другой океан, о котором он знал.

Но вскоре радость сменяется разочарованием, посланные на разведку корабли с меньшей осадкой возвращаются назад с сообщением, что вода в «проливе» пресная, а его берега сужаются. Магеллан понимает, что карта Бехайма неверна, а то, что моряки приняли за пролив, на самом деле огромная река (Ла-Плата), но другой карты у адмирала нет.

Это был решающий момент экспедиции. Что делать, вернуться с позором назад, признав поражение, и лишиться тем самым всего достигнутого? Или идти вперед в надежде на то, что пролив все же существует? Магеллан выбирает второе.

Бунтовщики умоляют Магеллана пощадить их после неудачного мятежа

Изображение: Stefano Bianchetti / Corbis / Getty

Бунт, казнь и пролив Всех Святых

В апреле флотилия добралась до 49 параллели. Начались морозы. Люди тряслись от холода, недовольство росло. В Севилье, когда они вербовались в плавание к Молуккским островам, им обещали тепло, изобилие и райские земли. Заботами вице-адмирала Картахены пополз слух:

Португальцу заплатили, чтобы погубить корабли нашего короля

Назревал бунт, и он случился. Бунтовщики захватили три корабля из пяти, при этом был убит верный долгу боцман «Сан-Антонио», а его капитан и часть команды связана и посажена в трюм. Бунтовщики решили, что дело сделано. Но они не знали, с кем имеют дело. Закаленный в боях, решительный и бесстрашный Магеллан действовал расчетливо и стремительно.

Бунт был подавлен. Капитан «Консепсьона» Касада, проливший кровь, публично казнен. А Картахена и участвовавший в заговоре священник оставлены на необитаемом берегу. Любопытно, но пройдет почти 60 лет, и во время второго в истории кругосветного плавания в этой же бухте при сходных обстоятельствах англичанин Френсис Дрейк казнит еще одного взбунтовавшегося капитана.

Порядок был восстановлен, а когда потеплело, корабли двинулись дальше на юг, обследуя каждую крупную бухту. Во время одной из таких разведок разбился о скалы «Сантьяго». К счастью, никто не погиб. На 54-м градусе южной широты Магеллан обнаружил проход, названный им проливом Всех Святых. Впоследствии его назовут Магеллановым проливом.

В 2020 году мне довелось проходить там на парусном фрегате. И сейчас это задача не из легких. Пролив представляет собой 600 километров лабиринта из островов, скал, проток и заливов. Даже имея все современные навигационные приборы, пройти его без опытного лоцмана мало кто решится.

Корабли Магеллана прошли пролив за месяц, но один из них, «Сан-Антонио», исчез. В эскадре думали, что он погиб. На самом же деле корабль дезертировал, благополучно вернувшись назад в Испанию.

Февраль 2020 года. Магелланов пролив

Фото: Петр Каменченко

22 ноября 1520 года горы с двух сторон расступились, и перед глазами отважных мореплавателей открылся морской простор с бесконечно далекой линией горизонта. В первый раз корабли сумели пройти из Атлантического океана в Тихий.

Новый огромный и тихий океан

Колумб перешел через Атлантику за 36 дней. Плавание Магеллана уже длилось год. Паруса и такелаж пришли в плачевное состояние. Несмотря на строжайшую экономию, запасов провизии оставалось совсем мало. Моряки вынуждены были есть пингвинов. Но погода благоприятствовала, постоянно дул ровный ветер слабой силы. Тогда Магеллан и дал новому океану название, которое сохранилось за ним навсегда — Тихий океан.

Тихий океан оказался намного больше, чем предполагал Фалейро. Мясо пингвинов было съедено, сухари превратились в пыль пополам с мышиным пометом, вода протухла. Деликатесом считалась пойманная крыса. В отсутствии витаминов началась цинга. Умерли 19 матросов. Заболел и сам Магеллан. В начале похода он объявил, что ни при каких обстоятельствах экспедиция не повернет назад: «Если надо, будем есть кожу на реях». И вот настал день, когда летописец экспедиции записал:

Чтобы не умереть с голоду, мы ели куски кожи, которой обтянут большой рей. Пробыв больше года под дождем и ветрами, кожа так задубела, что ее приходилось вымачивать в морской воде четыре-пять дней, чтобы потом съесть

Наконец 14 января 1521 года моряки увидели остров, но подойти к нему оказалось невозможно из-за рифов. Утром 6 марта, на 110-е сутки после отхода от Южной Америки, показался большой остров с обильной растительностью и пляжами с золотистым песком. Это был Гуам, самый южный из Марианских островов.

Острова пряностей (Молуккские острова)

Фото: Beawiharta / Reuters

Когда корабли подошли к берегу, их окружили пироги с дикарями. Мгновенно забравшись на борт, они принялись хватать все, что попадалось им под руку, украв даже одну из шлюпок. Измученная команда даже не сопротивлялась.

Магеллан отвел корабли от берега, но на следующий день вернулся. Для умиравших от голода и жажды людей было жизненно необходимо добыть воду и продовольствие. На берег высадили десант, моряки вернули украденные вещи и доставили на борт рыбу, свиней, кокосовые орехи и бананы. Но семь дикарей в ходе этой вылазки были убиты. Когда Магеллан отплывал, его сопровождал град стрел и камней. Остров назвали Воровским. Так прошло первое знакомство европейцев с аборигенами Океании.

Железо за золото и новые христиане

28 марта 1521 года флотилия приблизилась к еще одному большому острову. Ее встретили пироги, и тут обнаружилось, что местные аборигены говорят на том же языке, что и слуга Магеллана малаец Энрике. Острова пряностей, к которым стремилась Испания и Магеллан, были достигнуты. А первым человеком, обогнувшим земной шар, стал не мореплаватель-европеец, а раб-малаец.

Через несколько дней испанские корабли вошли в порт Себу на острове того же названия (Филиппинские острова). Правителем острова был хитрый раджа Хумабон. Сразу оценив величину европейских кораблей и мощь их пушек, раджа оказал гостям великолепный прием. Началась меновая торговля, исключительно выгодная для обеих сторон. Наибольший интерес для туземцев представляло железо, твердый металл, который в их глазах был полезнее золота. За 14 фунтов железа они отдали 15 фунтов золота. При этом европейцы вели себя вполне прилично. Магеллан не хотел лишних проблем с местным населением и поддерживал строгую дисциплину.

На радостях раджа пообещал быть верным подданным Испании и даже выразил желание перейти в христианство. Несколько дней подряд священник экспедиции крестил обретших истинную веру язычников, полагавших, что новый бог сделает их такими же сильными и богатыми, как пришельцы. Затем к новой счастливой жизни потянулись и жители других островов.

Смерть Магеллана. Рисунок 1860 года

Изображение: Wikipedia

«Тело не продается»

То ли из зависти, то ли по каким-то своим местным причинам, но столь тесная коллаборация не понравилась царьку крохотного островка Мактан по имени Силапулапу. Силапулапу оскорбил Хумабона и обещал подговорить к этому других царьков. Хумабон должен был грубияна проучить. И вот тут Магеллан совершил ошибку, стоившую ему жизни и едва не погубившую все, чего достигла экспедиция.

Опытный, осторожный, умный Магеллан зачем-то встрял в мелкую междоусобицу дикарей, решив показать мощь европейского оружия. Во главе 60 воинов адмирал лично высадился на мятежный остров, где был встречен несколькими сотнями дикарей. Из-за мелкой воды корабли не смогли подойти к берегу, чтобы поддержать десант огнем, а попасть из мушкета в скачущих по берегу дикарей оказалось непросто. Обнаружив, что ноги и руки испанцев не закрыты броней, туземцы принялись тыкать в них копьями. Магеллан был несколько раз ранен, окружен и убит.

Тело великого мореплавателя дикари с радостными криками таскали по всему острову. А когда испанцы вместо того, чтобы достойно наказать убийц своего адмирала, унизительно предложили обменять тело на выкуп из стеклянных бус, Силапулапу гордо ответил: «Тело нашего врага не продается». Что сделали туземцы с останками великого мореплавателя, осталось загадкой. Вроде каннибалами они не были. Но кто же их знает…

Со смертью Магеллана мгновенно изменилось и отношение островитян к европейцам. Недавние христиане, подданные Хумабона, напали на европейцев, когда те были на берегу. Началась резня, в которой погибли больше двухсот матросов и капитаны двух из трех кораблей. Удиравшие в панике каравеллы провожал горящий на берегу крест.

«Отплыв на запад, мы возвратились с востока»

Оставшейся в живых команды едва хватало, чтобы управлять двумя кораблями. Поэтому «Консепсьон» решили бросить. Без командующего и погибших капитанов экспедиция развалилась. «Тринидад» принялся пиратствовать в Филиппинских водах и в конце концов был захвачен португальцами. А «Виктория», пережив множество трудностей и лишений, вернулась в Испанию 6 сентября 1522 года.

Каракка «Виктория» — первый корабль, обошедший вокруг света. Встречают в Севилье

Изображение: Ipsumpix / Corbis / Getty

К этому моменту в живых осталось 18 моряков. За 1080 суток первого в истории кругосветного путешествия было пройдено 42 280 морских миль, или 85 700 километров. Интересно, что даже тех немногих товаров, что удалось сохранить в трюмах самого маленького из кораблей Магеллана, хватило, чтобы окупить всю экспедицию и даже получить прибыль в четыре процента.

Командир «Виктории» Тидоре Эльконо написал в своем отчете королю Испании:

Довожу до сведения Вашего Величества, что мы нашли камфору, корицу и жемчуг. Покорнейше просим оценить по заслугам тот факт, что мы совершили кругосветное плавание. Отплыв на запад, мы возвратились с востока

Фернан Магеллан — биография

Фернан Магеллан – испанский мореплаватель португальского происхождения, первым за всю историю совершивший кругосветное путешествие. Его именем назван пролив, несколько географических объектов на Земле и в космосе.

Сложно себе представить, как в 16 веке на деревянных кораблях, без высокотехнологичного оборудования и средств связи, человек смог осуществить кругосветное путешествие. Однако Фернану Магеллану это удалось: он не просто воплотил в жизнь мечту Колумба, но и сделал ряд важнейших географических открытий.

Детство и юность

Точных сведений о дате и месте рождения великого мореплавателя нет. Ранняя биография Магеллана до сих пор является предметом дискуссий исследователей истории.

Годом рождения путешественника принято считать 1480-й. А дальше у ученых возникают разногласия: одни называют дату 17 октября, другие же считают, что день его рождения – 20 ноября. Родным городом Фернана мог быть Порт либо Саброза – в этом вопросе единого мнения также нет.

Известно, что родители мальчика были небогатыми людьми, но имели старинные дворянские корни. Отец Руй ди Магальяйнш состоял на военной службе, а мать скорее всего была домохозяйкой: кроме Фернана, в семье подрастало еще четыре наследника.

В подростковом возрасте будущего мореплавателя отдали в услужение жене португальского монарха Жуана II Совершенного Леоноре Ависской. Придворные церемонии и развлечения королевского двора юношу мало интересовали. Он предпочитал ходить в дворцовую библиотеку, где мог часами изучать книги по астрономии и навигации.

Молодой паж прослужил при дворе около двенадцати лет, после чего ушел добровольцем на королевский флот.

Военные экспедиции

К концу 15 века португальцами уже было налажено морское сообщение с Индией. Фернан присоединился к отважным мореплавателям Франсишку ди Альмейды, и вскоре 25-летний новобранец принял участие в завоевании восточных территорий.

В течение пяти лет Магеллан служил во благо родной страны. После этого он попытался вернуться в Португалию, но определенные обстоятельства заставили его задержаться в Индии. Безупречная служба и доблесть принесли молодому человеку офицерское звание и уважение среди моряков.

В Лиссабон Фернан вернулся в 1512 году. В отличие от военных, гражданские его подвиги не оценили и встретили без особых почестей.

Сражаясь против повстанцев в Марокко, солдат получил серьезное ранение в ногу, из-за чего он до конца жизни хромал. Это обстоятельство вынудило мореплавателя покинуть ряды военного флота.

Могут быть знакомы

Великое кругосветное путешествие

Еще будучи пажом, Магеллан много времени провел в секретных архивах португальского монарха, где наткнулся на несколько интересных документов. Одним из них оказалась старинная карта, составленная путешественником Мартином Бейхемом. На схеме предшественника Фернан увидел пролив между неизведанным Южным морем и Атлантическим океаном. Карта не покидала голову юноши долгие годы, и в конце концов вдохновила его на далекое путешествие.

Добившись личного приема у короля, будущий первооткрыватель стал просить его об организации морской экспедиции. Правитель ответил отказом, припомнив военному его самовольное поведение во время подавления марокканского восстания, которое разгневало португальского короля Мануэла Первого. Кроме того, в этот период все силы флота были брошены на завоевание Индии со стороны Африки. Задумку Магеллана монарх счел нецелесообразной.

Отказ короля и его упреки Фернан перенес тяжело. Он решил покинуть родину и поселиться в Испании, купив собственный дом. В солнечной стране путешественник продолжил развивать идею кругосветной экспедиции.

В 15-16 веках Европа испытывала потребность в восточных специях, которые доставлялись с большим трудом, а поэтому и ценились наравне с золотом. Торговцы пряностями в те времена были весьма состоятельными людьми.

Найти кратчайший путь к индийским сокровищницам со специями было главным смыслом морских кампаний. Находясь в Испании, Магеллан связался с «Палатой контрактов» и предложил осуществить выгодную для всех идею кругосветной экспедиции. Однако и здесь бывший военный наткнулся на стену непонимания и недоверия.

Узнав о планах Фернана, состоятельный человек по имени Хуан де Аранда предложил ему помощь в обмен на 20% от выручки. Разумеется, при условии, что экспедиция окажется удачной. Но тут Магеллану поступило более выгодное предложение, согласно которому он отдавал лишь 1/8 часть прибыли.

В то время документ Папы Римского от 1493 года являлся главным правоустанавливающим законом для мореплавателей. Он гласил, что вновь открытые территории в направлении востока оставались за Португалией, а западные земли отходили Испании. Правитель последней и дал добро на морскую кампанию Магеллана, подписав соответствующий указ в марте 1518 года. Испанский монарх рассчитывал, что в ходе экспедиции удастся доказать принадлежность индийских островов к западу, и все несметные богатства в виде пряностей будут принадлежать его стране.

Мореплавателям король посулил двадцатую часть от всех сокровищ, привезенных из экспедиции. Для осуществления путешествия было подготовлено пять кораблей с двухгодовым запасом провианта. Флагманским судном стал «Тринидад», отправившийся в путь под командованием Фернана Магеллана.

Остальными кораблями управляли испанские аристократы, которые то и дело устраивали конфликты. Они были возмущены тем фактом, что во главе такой масштабной экспедиции стоит португалец и отказывались ему подчиняться. Недовольство усиливалось еще и потому, что Магеллан не делился с ними планом действий. Несмотря на то, что испанский монарх повелел всем капитанам безоговорочно подчиняться Фернану, они продолжали гнуть свою линию и даже сговорились избавиться от португальца при удобном случае.

Единственным человеком, на кого главнокомандующий мог положиться в столь опасном мероприятии, был его друг Руй Фалейра. Но принять участие в экспедиции астроном не смог из-за начавшихся припадком безумия.

Осенью 1519-го корабли под командованием Магеллана вышли из порта Сан-Лукарс и взяли курс на Канарские острова. Так началось великое кругосветное путешествие, подарившее миру несколько грандиозных открытий.

Флотилия медленно продвигалась по восточному побережью Южной Америки: моряки пытались найти то самое Южное море, увиденное Фернаном на карте немецкого географа. Первым открытием стал архипелаг Огненная Земля, обнаруженный на юге континента. Поначалу путешественники решили, что группа островов необитаема. Проплывая мимо архипелага ночью, моряки увидели несколько десятков огоньков. Магеллан предположил, что это действующие вулканы, из-за чего и нарек архипелаг таким именем. Однако вскоре выяснилось, что он заблуждался: огни оказались ничем иным, как разожженными индейцами кострами.

Корабли пересекли участок между Огненной Землей и Патагонией. После преодоления пролива, именуемого теперь Магеллановым, мореплаватели вышли в Тихий океан.

Кругосветное путешествие Магеллана открыло человечеству новые территории и доказало, что Земля имеет шарообразную форму. Из всей флотилии в гавань Севильи вернулся лишь один корабль под командованием Хуана Себастьяна Элькано. На борту находилось 18 изможденных моряков, перенесших за 1081 день путешествия голод, отсутствие воды и гибель товарищей.

Личная жизнь

Хоть Фернан Магеллан и был потомком дворян, внешность его скорее была крестьянской. Путешественник имел невысокий рост, коренастое телосложение и довольно простые черты лица. Сам же мореход говорил, что человека следует судить не по внешности, а по его делам.

Переехав в Испанию, Фернан познакомился с эмигрантом из Португалии Диего Барбозой и его прекрасной дочерью Беатриче. Между молодыми людьми возникла симпатия, и вскоре они поженились. В 1519-м супруга подарила мореплавателю первенца. К сожалению, из-за болезни мальчик скончался. Беатриче забеременела еще раз, но во время тяжелых родов умерла, как и ребенок во чреве. Таким образом, знаменитый мореплаватель потомков после себя не оставил.

Смерть

Несмотря на масштабную подготовку перед плаванием, провиант у путешественников закончился уже через несколько месяцев. Сохранились записи участников экспедиции, рассказывающие о том, что морякам приходилось жевать паруса и другие снасти, хоть как-то похожие на еду. Более двадцати членов команды скончались от голода и цинги.

Наконец путешественники достигли Филиппинских островов, которые Фернан поначалу назвал архипелагом Святого Лазаря. На долгожданной суше мореходы наконец смогли восполнить запасы продовольствия и пресной воды. Можно было продолжать путь, но тут у Магеллана возник конфликт с местным вождем Мактаном Лапу-Лупу, воспротивившимся новым порядкам.

Тогда португалец решил выдвинуть против Мактана военную экспедицию. Таким образом он рассчитывал показать коренным жителям испанскую мощь и бесполезность сопротивления новым хозяевам.

Здесь великий мореплаватель допустил серьезную ошибку. Он переоценил возможности своего недостаточно подготовленного войска и недооценил ловкость аборигенов.

Из-за специфического рельефа побережья кораблям не удалось подойти к острову на расстояние, достаточное для поддержки десанта огнем. Помимо этого, туземцы уже успели изучить оружие европейцев и определить его слабые стороны. Они быстро перемещались по знакомой с детства территории острова, не давая захватчикам прицелиться. Сами же атаковали незащищенные броней ноги солдат. Вскоре перевес оказался на стороне хозяев, и испанские воины были вынуждены предаться бегству. Во время отступления Фернан Магеллан был убит. Это произошло в конце апреля 1521 года.

После потери главнокомандующего и большей части войска судно «Виктория» под управлением Элькано продолжило путь. Капитан и большая часть команды решили во что бы то ни стало достичь берегов Испании. С трудом обогнув мыс Доброй Надежды, корабль почти два месяца следовал вдоль побережья Африки к северо-западу.

В начале июля 1522-го изношенная «Виктория» с полуживыми моряками подошла к Зеленому Мысу, находившемуся в португальских владениях. Избежать остановки здесь не представлялось возможным – экипаж попросту не выдержал бы отсутствия питья и провианта. Задерживаться здесь долго моряки не стали: слишком велика была угроза нападения португальцев. Судно двинулось на запад, таким образом завершая кругосветную экспедицию.

В сентябре капитан Хуан Себастьян Элькано привел «Викторию» в порт Севильи. Восемнадцать обессиленных моряков и полуразвалившееся судно – все, что осталось от мощной флотилии из пяти кораблей.

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Первое кругосветное путешествие Фернандо Магеллана

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 332.

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 332.

Португальский мореплаватель Фернандо (Фернан) Магеллан известен своим кругосветным плаванием. В статье содержится рассказ об этом путешествии.

Цель похода

Целью экспедиции была разведка торговых путей к Молуккским островам (современная Индонезия), которые современники называли Островами пряностей.

Изначально экспедиция планировалась, как коммерческое предприятие, так как маршрут в Индию пролегал в зоне, принадлежащей Португалии. Испания желала узнать альтернативный путь к островам, откуда поступали пряности, приносящие огромный доход владельцу.

Будущее путешествие не считалось трудным, так как по представлению современников Индия находилась недалеко от Америки, а путь в Америку был хорошо известен испанским морякам.

Начало похода

Кругосветное плавание Магеллана началось в сентябре 1519 года и продолжалось 3 года. Были оснащены 5 кораблей, загружены провиантом из расчета двухлетнего похода.

За 2 месяца эскадра пересекла Атлантику, достигнув берегов Бразилии, и двинулась к вдоль берега на юг. При обследовании устья Параны стало ясно, что это часть реки, а не пролив в соседний океан.

Сохраняя южное направление, эскадра продолжила плавание и, не дойдя до оконечности Южной Америки, остановилась на зимовку. Здесь, на 49-й параллели, капитан с трудом подавил мятеж команды 2-х кораблей.

Вперед, через Тихий океан!

С середины мая до конца октября корабли пытались обнаружить пролив в Тихий океан. Наконец, путь был найден, 38 дней эскадра лавировала между островами. В конце ноября 1520 года флотилия вышла в Тихий океан.

Впоследствии извилистый пролив между Огненной Землей и Южной Америкой был назван Магеллановым проливом.

Плавание через океан было спокойным, погода благоприятствовала, не было ни одного шторма. Именно тогда океан получил свое имя. Однако для моряков это было трудное время из-за голода и цинги. Размер океана оказался неожиданным, продуктов не хватило, острова, где можно было пополнить запасы не встретились. Погибло почти 30 человек.

Пройдя более 17 тыс. км за 4 месяца, испанцы высадились на Филлипинских островах.

Гибель Магеллана

Стремясь подчинить испанской короне как можно больше островов, испанцы действовали подкупом и хитростью. Однако, не все вожди признали новую власть. Во время вооруженного нападения на один из непокорных островов Магеллан был убит вождем Лапу-Лапу. Сегодня на этом месте сохранился обелиск, установленный испанскими властями. Рядом построен храм с памятником, посвященные Лапу-Лапу, который на Филиппинах считается национальным героем.

После гибели Магеллана единственный уцелевший корабль под командованием испанского мореплавателя Элькано направился на запад и в сентябре 1522 года вернулся в Испанию с грузом пряностей. С ним вернулись 18 человек из 230 моряков, внесенных в списки 3 года назад.

Что мы узнали?

В статье кратко описано первое кругосветное путешествие Фернандо Магеллана, приведена дата начала экспедиции. Мы узнали, в каких трудных условиях находились мореплаватели в XVI веке, как совершались открытия того времени.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Наталья Елуфимова

5/5

-

Ксения Ефременкова

5/5

-

Миша Иванов

5/5

Оценка доклада

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 332.

А какая ваша оценка?

Nao Victoria, the ship accomplishing the circumnavigation and the only to return from the expedition. Detail from a map by Abraham Ortelius. |

|

| Country | |

|---|---|

| Leader | Ferdinand Magellan (succeeded by Juan Sebastián Elcano) |

| Start | Sanlúcar de Barrameda September 20, 1519 |

| End | Sanlúcar de Barrameda September 6, 1522 |

| Goal | Find a western maritime route to the Spice Islands |

| Ships |

|

| Crew | approx. 270 |

| Survivors | 18 arrived with Elcano, 12 were captured by the Portuguese in Cape Verde, 55 returned with the San Antonio in 1521 |

| Achievements |

|

| Route | |

Route taken by the expedition, with milestones marked |

The Magellan expedition, also known as the Magellan–Elcano expedition, was the first voyage around the world in recorded history. It was a 16th century Spanish expedition initially led by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan to the Moluccas, which departed from Spain in 1519, and completed in 1522 by Spanish navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano, after crossing the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, culminating in the first circumnavigation of the world.

The expedition accomplished its primary goal – to find a western route to the Moluccas (Spice Islands). The fleet left Spain on 20 September 1519, sailed across the Atlantic ocean and down the eastern coast of South America, eventually discovering the Strait of Magellan, allowing them to pass through to the Pacific Ocean (which Magellan named). The fleet completed the first Pacific crossing, stopping in the Philippines, and eventually reached the Moluccas after two years. A much-depleted crew led by Juan Sebastián Elcano finally returned to Spain on 6 September 1522, having sailed west across the great Indian Ocean, then around the Cape of Good Hope through waters controlled by the Portuguese and north along the Western African coast to eventually arrive in Spain.

The fleet initially consisted of five ships and about 270 men. The expedition faced numerous hardships including Portuguese sabotage attempts, mutinies, starvation, scurvy, storms, and hostile encounters with indigenous people. Only 30 men and one ship (the Victoria) completed the return trip to Spain.[n 1] Magellan himself died in battle in the Philippines, and was succeeded as captain-general by a series of officers, with Elcano eventually leading the Victoria‘s return trip.

The expedition was funded mostly by King Charles I of Spain, with the hope that it would discover a profitable western route to the Moluccas, as the eastern route was controlled by Portugal under the Treaty of Tordesillas. Though the expedition did find a route, it was much longer and more arduous than expected, and was therefore not commercially useful. Nevertheless, the expedition is regarded as one of the greatest achievements in seamanship, and had a significant impact on the European understanding of the world.[1][2]

Background[edit]

Christopher Columbus’s voyages to the West (1492–1503) had the goal of reaching the Indies and establishing direct commercial relations between Spain and the Asian kingdoms. The Spanish soon realized that the lands of the Americas were not a part of Asia, but another continent. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas reserved for Portugal the eastern routes that went around Africa, and Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese arrived in India in 1498.

Given the economic importance of the spice trade, Castile (Spain) urgently needed to find a new commercial route to Asia. After the Junta de Toro conference of 1505, the Spanish Crown commissioned expeditions to discover a route to the west. Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa reached the Pacific Ocean in 1513 after crossing the Isthmus of Panama, and Juan Díaz de Solís died in Río de la Plata in 1516 while exploring South America in the service of Spain.

Ferdinand Magellan was a Portuguese sailor with previous military experience in India, Malacca, and Morocco. A friend, and possible cousin, with whom Magellan sailed, Francisco Serrão, was part of the first expedition to the Moluccas, leaving from Malacca in 1511.[3] Serrão reached the Moluccas, going on to stay on the island of Ternate and take a wife.[4] Serrão sent letters to Magellan from Ternate, extolling the beauty and richness of the Spice Islands. These letters likely motivated Magellan to plan an expedition to the islands, and would later be presented to Spanish officials when Magellan sought their sponsorship.[5]

Historians speculate that, beginning in 1514, Magellan repeatedly petitioned King Manuel I of Portugal to fund an expedition to the Moluccas, though records are unclear.[6] It is known that Manuel repeatedly denied Magellan’s requests for a token increase to his pay, and that in late 1515 or early 1516, Manuel granted Magellan’s request to be allowed to serve another master. Around this time, Magellan met the cosmographer Rui Faleiro, another Portuguese subject nursing resentment towards Manuel.[7] The two men acted as partners in planning a voyage to the Moluccas which they would propose to the king of Spain. Magellan relocated to Seville, Spain in 1517, with Faleiro following two months later.

On arrival in Seville, Magellan contacted Juan de Aranda, factor of the Casa de Contratación. Following the arrival of his partner Rui Faleiro, and with the support of Aranda, they presented their project to the king Charles I of Castile and Aragon (future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V). Magellan’s project, if successful, would realise Columbus’ plan of a spice route by sailing west without damaging relations with the Portuguese. The idea was in tune with the times and had already been discussed after Balboa’s discovery of the Pacific. On 22 March 1518 the king named Magellan and Faleiro captains so that they could travel in search of the Spice Islands in July. He raised them to the rank of Commander of the Order of Santiago. They reached an agreement with King Charles which granted them, among other things:[8]

- Monopoly of the discovered route for a period of ten years.[9][10]

- Their appointment as governors (adelantado) of the lands and islands found, with 5% of the resulting net gains, inheritable by their partners or heirs.[9][11]

- A fifth of the gains from the expedition.[9]

- The right to ship 1,000 ducats worth of goods from the Mollucas to Spain annually exempt from most taxes.[10]

- In the event that they discovered more than six islands, one fifteenth of the trading profits with two of their choice,[9] and a twenty-fifth from the others.[12]

The expedition was funded largely by the Spanish Crown, which provided ships carrying supplies for two years of travel. Though King Charles V was supposed to pay for the fleet he was deeply in debt, and he turned to the House of Fugger.[citation needed] Through archbishop Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, head of the Casa de Contratación, the Crown obtained the participation of merchant Cristóbal de Haro, who provided a quarter of the funds and goods to barter.

Expert cartographers Jorge Reinel and Diego Ribero, a Portuguese who had started working for King Charles in 1518[13] as a cartographer at the Casa de Contratación, took part in the development of the maps to be used in the travel. Several problems arose during the preparation of the trip, including lack of money, the king of Portugal trying to stop them, Magellan and other Portuguese incurring suspicion from the Spanish, and the difficult nature of Faleiro.[14]

Construction and provisions[edit]

The fleet, consisting of five ships with supplies for two years of travel, was called Armada del Maluco, after the Indonesian name for the Spice Islands.[15] The ships were mostly black, due to the tar covering most of their surface. The official accounting of the expedition put the cost at 8,751,125 maravedis, including the ships, provisions, and salaries.[16]

Food was a hugely important part of the provisioning. It cost 1,252,909 maravedis, almost as much as the cost of the ships. Four-fifths of the food on the ship consisted of just two items – wine and hardtack.[17]

The fleet also carried flour and salted meat. Some of the ships’ meat came in the form of livestock; the ship carried seven cows and three pigs. Cheese, almonds, mustard, and figs were also present.[18] Carne de membrillo,[19] made from preserved quince, was a delicacy enjoyed by captains which may have unknowingly aided in the prevention of scurvy.[20]

Ships[edit]

The fleet initially consisted of five ships, with Trinidad being the flagship. All or most were carracks (Spanish «carraca» or «nao»; Portuguese «nau»).[n 2] The Victoria was the only ship to complete the circumnavigation. Details of the ships’ configuration are not known, as no contemporary illustrations exist of any of the ships.[23] The official accounting of the Casa de Contratación put the cost of the ships at 1,369,808 maravedis, with another 1,346,781 spent on outfitting and transporting them.[24]

| Ship | Captain | Crew | Weight (tons)[25] | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trinidad | Ferdinand Magellan | 62 then 61 after a stop-over in Tenerife[26] | 110 | Departed Seville with other four ships 10 August 1519. Broke down in Moluccas, December 1521 |

| San Antonio | Juan de Cartagena | 55[27] | 120 | Deserted in the Strait of Magellan, November 1520,[28] returned to Spain on 6 May 1521[29] |

| Concepción | Gaspar de Quesada | 44 then 45 after a stop-over in Tenerife[30] | 90 | Scuttled in the Philippines, May 1521 |

| Santiago | João Serrão | 31 then 33 after a stop-over in Tenerife[31] | 75 | Wrecked in storm at Santa Cruz River, on 22 May 1520[32][33] |

| Victoria | Luis Mendoza | 45 then 46 after a stop-over in Tenerife[34] | 85 | Successfully completed circumnavigation, returning to Spain in September 1522, captained by Juan Sebastián Elcano. Mendoza was killed during a mutiny attempt. |

Crew[edit]

The crew consisted of about 270 men,[35] mostly Spaniards. Spanish authorities were wary of Magellan, so that they almost prevented him from sailing, switching his mostly Portuguese crew to mostly men of Spain. In the end, the fleet included about 40 Portuguese,[36] among them Magellan’s brother-in-law Duarte Barbosa, João Serrão, Estêvão Gomes and Magellan’s indentured servant Enrique of Malacca. Crew members of other nations were also recorded, including 29 Italians, 17 French, and a smaller number of Flemish, Greek, Irish, English, Asian, and black sailors.[37] Counted among the Spanish crew members were at least 29 Basques (including Juan Sebastián Elcano), some of whom did not speak Spanish fluently.[37]

Ruy Faleiro, who had initially been named co-captain with Magellan, developed mental health problems prior to departure and was removed from the expedition by the king. He was replaced as the fleet’s joint commander by Juan de Cartagena and as cosmographer/astrologer by Andrés de San Martín.

Juan Sebastián Elcano, a Spanish merchant ship captain living in Seville, embarked seeking the king’s pardon for previous misdeeds. Antonio Pigafetta, a Venetian scholar and traveller, asked to be on the voyage, accepting the title of «supernumerary» and a modest salary. He became a strict assistant of Magellan and kept a journal. The only other sailor to keep a running account during the voyage would be Francisco Albo, who kept a formal nautical logbook.