- Современные течения ислама – православная оценка свящ. Даниил Сысоев

- Ислам и христианство. Сравнительная таблица вероучений

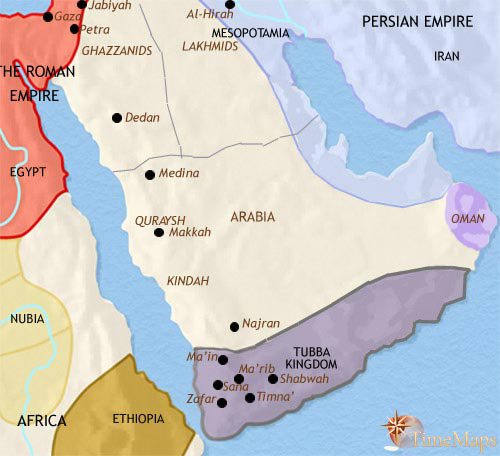

Ислам зародился на юго-западе Аравийского полуострова в начале VII в. в Хиджазе среди племен Западной Аравии. Основатель – Мухаммед (570–632 гг.), провозгласивший себя пророком. Созданная им община стала основой сформировавшегося впоследствии государственного образования – Арабского халифата.

В настоящее время почти половина всех мусульман проживает в Северной Африке, около 30% — в Пакистане и Бангладеш, более 10% в Индии, первое место среди стран по численности мусульман принадлежит Индонезии (см. карту). Подавляющее большинство мусульман в России составляют татары и башкиры.

Мусульмане исповедуют, что «нет никакого божества, кроме Аллаха, а Мухаммед – пророк Аллаха». Некорректно считать Аллаха тем же Единым Богом, что и в христианстве, т. к. представления мусульман о Боге противоречат Божественному Откровению (см. Одному ли Богу поклоняются христиане и мусульмане?). Также как, например, некорректно считать настоящей звездой, сделанную человеческими руками, звёздочку на рождественской ёлке, хотя её и называют звездой.

Слово ислам в переводе с арабского означает покорность. Ислам также называют мусульманством (от арабского «муслим» – «тот, кто покоряется»).

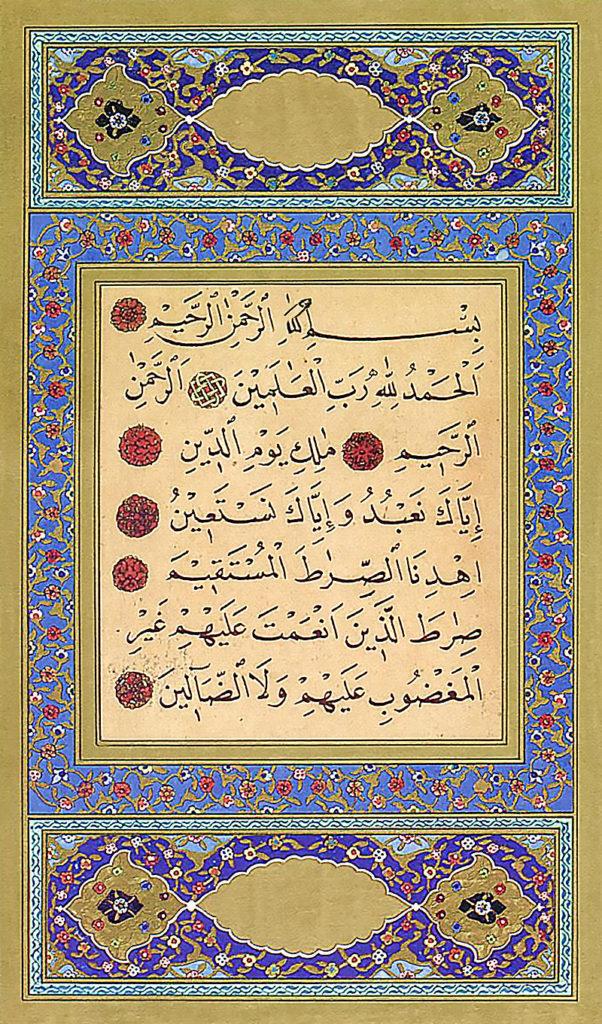

Согласно вере мусульман, Аллах передал Мухаммеду через ангела Коран, который стал священным писанием для мусульман. Мусульмане противоречиво относятся к Библии, поскольку в ней содержится Откровение о Едином Боге, но нет никаких упоминаний о Мухаммеде. Они считают Библию частично искаженной (но в чём точно, они не знают), но не могут отрицать содержащегося в ней монотеистического знания, заимствованного Кораном.

Коран состоит из 114 глав (сур). Название суры, как правило, не отражает ее содержания, а связано с самой запоминающейся фразой или темой. Помимо Корана, источником вероучения является Сунна – рассказы о жизни Мухаммеда и его высказывания в виде хадисов (сказаний).

В настоящее время ислам разделен на два основных течения. Большая часть мусульман мира принадлежит к суннитам. В частности, к ним относятся около 90% мусульман Ближнего Востока. Другое крупное течение ислама – шииты.

Сунниты придерживаются принятого ими свода хадисов, религиозной практики и правил поведения мусульманина во всех жизненных ситуациях, называя этот свод сунной («обычай», «пример», «направление»). Шииты представляют партию (от слова «шиа» – партия), которая утверждает, что власть в общине должна принадлежать только потомкам Мухаммеда (то есть детям Фатимы, его дочери, и Али, его двоюродного брата), а не выборным лицам, как это существует у суннитов. Они не принимают сунну целиком, дополняя ее своими постановлениями, включающими веру в особых посредников между Аллахом и мусульманами – имамов.

Крупное направление современного ислама представлено ваххабитами, выступающими под лозунгом «очищения» ислама, «возвращения» к порядкам времен Мухаммеда.

В исламе можно выделить следующие главные предметы веры:

- вера в Аллаха (таухид)

- вера в ангелов Аллаха (маляикат)

- вера в Писания Аллаха (китаб)

- вера в Пророков и Посланников Аллаха (анбийа)

- вера в предопределение Аллаха (къадр)

- вера в будущую жизнь (ахъират)

Обязательны для мусульманина следующие пять «столпов ислама» (араб. хамсат уль-аркян аль-ислам) — основные предписания, обязательные для всех мусульман:

- чтение шахады («нет никакого божества, кроме Аллаха, а Мухаммед – пророк Аллаха»);

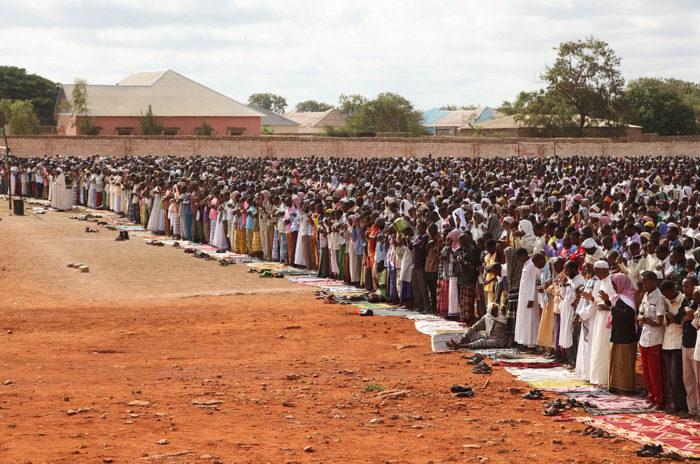

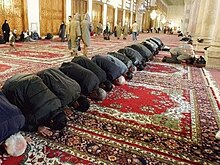

- пять обязательных молитв в сутки («намаз»), выполняемые на арабском языке с соблюдением строго определенного обряда;

- соблюдение постов в течение месяца рамадан, когда мусульмане обязаны воздерживаться от любой пищи и питья от восхода до заката;

- паломничество («хадж») в Мекку по меньшей мере раз в жизни мусульманина;

- пожертвования нуждающимся и на нужды общины (“закят”).

В отличие от христианского Откровения, ислам не учит о том, что Бог есть Любовь, воплотившаяся ради спасения людей, а представляет Аллаха лишь как судью, воздающего и наказывающего за дела, предопределяющего человеческую судьбу. Аллах не любит грешников – это 24 раза повторяется в Коране (2,190), Аллах любит только боящихся его (3,76). Мусульмане никогда точно не знают, определил ли Аллах для них рай или же они пойдут в ад.

Богочеловек Иисус Христос принимается как один из пророков для своего народа и своего времени, но Его Божественность и реальность Боговоплощения отрицается. Мусульмане считают, что перед крестными страданиями Христос чудесным образом заменил Себя другим человеком, а Сам был взят на Небо живым.

Вообще ислам представляет собой нерасторжимое единство веры, государственно-правовых установлений и определенных форм культуры. Исламу не свойственно разделение сферы жизни на светскую и религиозную части. Эта неразделенность привела к появлению Шариата – закона, который основан на интерпретации положений Корана и Сунны и содержит религиозные установления, правовые нормы, нравственные и бытовые предписания.

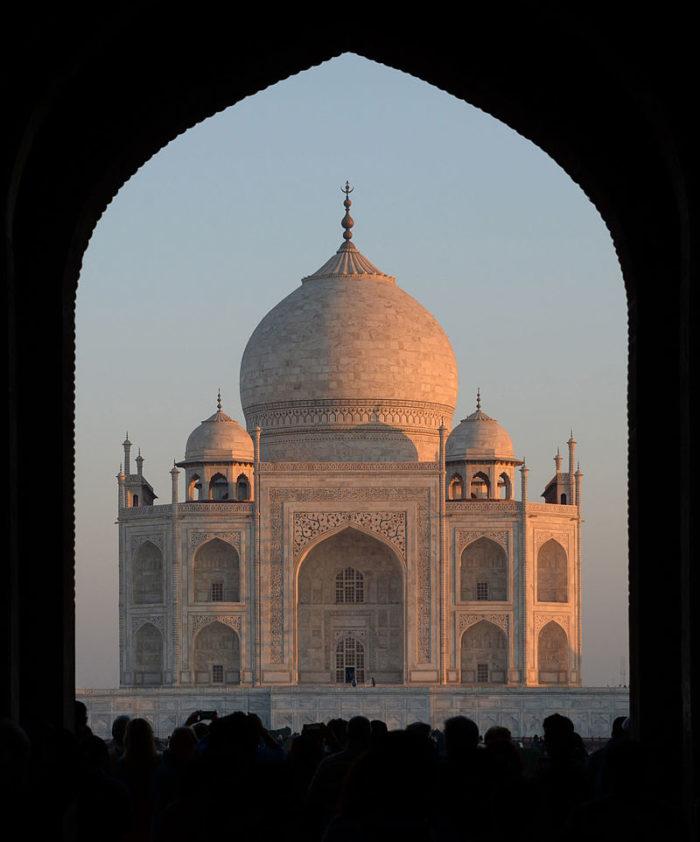

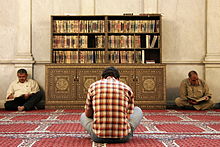

Здание для коллективных молитв мусульман называется мечетью; флигелем к мечети пристраиваются башни-минареты. Согласно шариату, для мусульманской молитвы, в том числе и коллективной, может использоваться любое помещение, кроме бань и туалетов. И если в православном храме совершаются особые таинства, которые мирянин самостоятельно воспроизвести у себя дома не может, то в мечети мусульмане совершают точно такой же ритуал намаза, как и дома. Ритуалы бракосочетания и похорон традиционно в исламе совершаются вне мечети, что предусмотрено и шариатом.

Руководство религиозной жизнью мусульман в конкретном регионе (государстве) осуществляется наиболее авторитетными лидерами (в исламе нет священства как такового). Это – муфтий у суннитов или шейх-уль-ислам у шиитов; надзор за соответствием шариату ведут шариатские судьи – кази. В настоящее время муфтий утверждает имамов мечетей, в которых они являются полноправными руководителями.

Оценка мусульманской веры

В вере мусульманской, изложенной в Коране, надобно различать две стороны: во-первых истины, заимствованные из священных книг Ветхого и Нового Завета, каковы многие здравые понятия о Боге и Его свойствах, об ангелах, многие нравственные предписания и заповеди, многие исторические сказания, – что подтверждается частыми ссылками на эти книги самого Магомета; и во-вторых – все то, что заимствовано из других источников: частью из древней аравийской веры, частью из иудейского Талмуда, а частью передано самим Магометом и его последователями.

Первого рода истины имеют полное свое достоинство, но они принадлежат Божественному Откровению, а не Магомету или Корану. Корану же принадлежит только то, что здесь эти светлые истины смешаны нередко с такими заблуждениями и баснями, которые почти совершенно затемняют их и подавляют. Так, например, в Коране говорится, будто Авраам и Измаил построили храм в Мекке (сур. 2:121), будто в жертву принесен был Измаил (сур. 38:188), будто Дева Мария, Матерь Господа нашего Иисуса, была сестра Аарона, будто Иисус еще в колыбели изрек о себе: «Я раб Бога, Он дал мне книгу и поставил меня Пророком» (сур. 19:28) и т.п.

Что же касается прочих частей мусульманского учения, которые заимствованы в Коране из человеческих источников, то здесь мы часто встречаем утверждения, явно противоречащие Божественному Откровению.

Так в теоретической части утверждается:

а) что все, происходящее в мире, подчинено безусловному предопределению Аллахом, а иначе происходить не может (17:13; 9:53);

б) что, в частности, и каждый человек имеет свою неизбежную, неотвратимую судьбу (17:13), каждому предназначается известный образ жизни и деятельности, доброй или злой, – чем явно подрывается всякая свобода и нравственность, и Бог становится виновником зла;

в) что Бог сотворил многих людей для геенны, и потому в собственном смысле есть деспот (7:180; 37:163; 3:189);

г) что вечное блаженство праведников в раю будет состоять в самых грубых чувственных удовольствиях (2:25; 37:41; 55:45) и проч.

Неизбежным плодом такого учения выходит то, что вся мусульманская нравственность ограничивается строгим исполнением внешних постановлений, в то время как на исправление сердца не обращается почти никакого внимания (более того, грех понимается, лишь как незнание закона).

Главная слабость исламского вероучения состоит в том, что оно является лишь религиозным законом, сводом правил и предписаний и не даёт прямой связи с Богом (см. сравнительную таблицу). Мусульмане взяли на веру изречения Мухаммеда, который никогда не общался с Творцом напрямую и придали божественные свойства книге с записью этих изречений – Корану. При этом они упорно не желают принимать веру в Живого Бога, Который воплотился, снизошел к падшему человечеству для его спасения, открыл Себя для общения со всеми людьми. Живой Бог отвергает формализм в отношении Себя и говорит: «Сыне, дай Мне твоё сердце!». Ему нужно именно человеческое сердце, а не правильно исполненные законы и обряды. Творец и Спаситель мира открыт для любого человека, который обращается к Нему с искренней молитвой и покаянием. Живой Бог просит любви к Себе, а не мертвых ритуалов, что хорошо видно из Его отношения к фарисейскому благочестию в Евангелиях.

Редакция

***

Современные течения ислама – православная оценка^

cвященник Даниил Сысоев

Массовый террор, развязанный исламистами, застал наше общество совершенно не подготовленным не только к адекватному ответу на новую угрозу, но и не понимающим самой сути проблемы. В представлении рядового обывателя, как атеиста, так и православного, ислам— это достаточно примитивная религия, которая, однако, вполне респектабельна и традиционна. Ко всему прочему утверждается, что, как и все религии (якобы «путь к одной вершине»), ислам учит только хорошему и мирно относится к Православию. Патриоты утверждают, будто ислам и христианство в России изначально жили в мире, и лишь враги пытаются их рассорить, чтобы уничтожить нашу страну. Мы попытаемся дать православную оценку реальному исламу, как он существует сейчас.

Для того чтобы понять эту религию, необходимо помнить, что ислам — не то, что понимается под словом «религия» на Западе. Это не аналог Церкви или секты, чья цель — в преображении души человека. Скорее это некий глобальный социально-религиозный проект построения царства Божия на земле. В этом ислам скорее близок к компартии, национал – социализму или нынешней глобализации. Для мусульман не существует разрыва между политикой и религией — это две стороны одного целого, регулируемого законом (шариатом), приписанным Аллаху. Именно поэтому всякая попытка встроить ислам в неисламский порядок может существовать лишь до тех пор, пока последний достаточно силен, чтобы сдерживать исламский рост.

Общие принципы ислама

Несмотря на то что многие представители ислама из пропагандистских соображений отвергают мусульманство тех или иных лиц (в основном террористов), на самом деле по исламскому вероучению мусульманином является тот, кто соблюдает пять столпов ислама.

- Первый — это исповедание веры (шахада): «Нет бога, кроме Аллаха, и Мухаммед — пророк Его». Произнесение этой формулы в присутствии не менее двух мусульман становится автоматическим.

- Второй столп — исполнение обряда поклонения — намаза.

- Третий столп — обязательный налог на бедных (закят).

- Четвертый столп — хранение поста месяца Рамадан.

- Пятый столп — паломничество в Мекку (хадж).

Очень многие проповедники ислама считают шестым столпом обязанность джихада — священной войны с неверными.

Все, кто хранит эти пять столпов, являются мусульманами. При этом должно помнить, что в исламе не существует духовенства. Из-за того, что Коран отвергает возможность усыновления людей Богу, в исламе нет посредников. Ведь по сравнению с Аллахом все люди букашки. Поэтому никакое высказывание людей не обладает абсолютным авторитетом. Более того, для блага ислама шариат предоставляет мусульманам право на ложь. Поэтому не стоит серьезно подходить к высказываниям религиозных лидеров ислама. Они и сами не относятся серьезно к тому, что вкладывают в доверчивые уши кафиров (неверных), предназначенных к аду. Никакой мулла не властен отлучить мусульманина от уммы (общины). Это может сделать только шариатский суд.

Православная Церковь оценивает эти пять столпов как демоническое заблуждение. Первый столп — вера (акида), включает веру в шесть основ: мусульманин должен верить в Аллаха, его ангелов, его Писание, в его посланников, в последний день и предопределение.

Главным предметом веры в исламе является Аллах — особое существо, похожее на Бога христиан. Главным его атрибутом является единство. Ему приписывается создание мира, ниспослание Писания и пророков и суд в конце времен. Однако в отличие от истинного Бога Аллах не личность. Он не добр, не дает свободы своему творению, ибо определяет все действия (как добрые, так и злые). Он ограничен пространством. Ислам отвергает Триединство. Наряду с Аллахом вечно существует Коран.

Православная Церковь на основании Священного Писания отвергла тождество Аллаха с Богом Творцом, давшим Библию и спасшим нас во Христе. Это учение было официально подтверждено на Константинопольском Соборе 1180 года. Аллах ислама не существует в действительности. Это результат извращения представления об истинном Творце, которое дьявол посеял в уме Мухаммеда. Мы можем назвать его идолом, построенным в уме мусульман, подобно тому как язычники измышляли себе ложных богов.

Вера в ангелов в исламе также отличается от откровения Божия. Ангелы ислама — особые существа, сотворенные из света, исполняющие волю Аллаха. Ислам отвергает грехопадение ангелов (кроме Иблиса — сатаны, чья ангельская природа находится под сомнением). Кроме ангелов есть еще один вид существ — это джинны, созданные из бездымного пламени. Они разделены на джиннов-язычников и джиннов-мусульман. Первые являются причиной бед людей. Джинны могут жениться, рожать детей, даже вступать в половые отношения с людьми.

Такое учение об ангелах крайне далеко от истины. Бог открыл нам существование мира духовных ангелов, расколотого мятежом Денницы. Благие ангелы — наши помощники и старшие братья, входящие в небесную Церковь. Мятежные ангелы— наши враги, изгоняемые силой Божией и знамением креста. В результате искаженного понимания ангельской природы в исламе нет реальной духовной борьбы с демонами. Напротив, очень легко человек подпадает под действие духов зла. В связи с этим весь исламский мир пронизан страхом перед порчей, сглазом и колдовством. Часто встречаются и случаи беснования.

Вера в Писания также отделяет ислам от христианства. Согласно Корану Аллах послал некие «Свитки» Аврааму, «Таврат» (Закон) Моисею, «Забур» (Псалтирь) Давиду, «Инжил» (Евангелие) Иисусу Христу и Коран Мухаммеду. Но, по убеждению мусульман, все Писания, кроме Корана, искажены. Поэтому они отвергают истинное Откровение Божие, признавая только Коран. Мусульмане убеждены, что Коран является копией некоего вечного подлинника, надиктованного Аллахом через ангела Джибрила. Они считают, будто Писание должно быть всегда прямой речью Аллаха на арабском языке. Поэтому реальное слово Божие, где Творец говорит и словом и делом, совершенно неприемлемо для сторонников ислама Коран радикально отличается от Библии. Истории, содержащиеся в нем, выдуманы и противоречат как Писанию, так и истории. (Например, Дева Мария считается сестрой Моисея, а Аман из Книги Есфирь объявляется визирем фараона времен Моисея.)

Богословие радикально отличается от библейского. В отличие от Библии Коран содержит 225 противоречий. Православная Церковь считает Коран выдумкой Мухаммеда, основанной на демоническом внушении. Мусульмане убеждены, что Библия — это человеческое искажение, неузнаваемо извратившее слово Творца.

Вера в посланников также отличает ислам от христианства (и иудаизма). По убеждению мусульман, в принципе сущность послания Аллаха не меняется. Во все времена единственной вестью является утверждение единобожия. Ничего другого Аллах сказать не может. Все, что не сводится к этому, объявляется человеческим измышлением. Похоже, бог мусульман меньше способен к творчеству, чем человек. (Впрочем, мы знаем, что ангелы, в том числе и падшие, не способны к творчеству, в отличие от человека.)

Те посланники, которых упоминает Коран и сунна («священное Предание»), хотя и носят имена, похожие на библейские, чаще всего не имеют почти ничего общего с реальными. Например, Христос объявляется не Богом, а творением. Его чудеса абсурдны (заимствованы чаще всего из апокрифов). К примеру, рассказывается о столе с едой, посланной с неба по просьбе Исы, или воспроизводится рассказ апокрифов об оживлении Им глиняных птичек. Самое страшное, что мусульмане отвергают сам факт распятия и воскресения Христа Спасителя. По их убеждению, Аллах вознес Христа, а на кресте был распят другой человек (Иуда или Симон Киринейский). Это богохульное утверждение противоречит как Евангелию, так и самому характеру Богочеловека. Не случайно мусульмане ненавидят святой Крест, так что утверждают, будто одним из главных дел Христа после Его возвращения на землю будет уничтожение всех крестов. Так дух, действующий в исламе, выдает себя. Думаю, что и запрет на вино на самом деле связан с ненавистью к святому Причастию.

Исламисты доходят до абсурда, объявляя даже идолопоклонников посланниками Аллаха (например Александр Македонский — Зу-ль-Кифль). Поэтому является совершено неверным утверждение, будто мусульмане почитают Моисея, Христа или Давида. Под этими именами выведены совершенно другие персонажи. В этом отношении мусульмане тождественны оккультистам.

Вера в последний день у мусульман также не соответствует слову Божию. По их учению, душа умершего существует в трупе, где грешников мучают ангелы, а праведники пребывают в покое. (Хотя непонятно, какое наслаждение может быть в могиле.) Перед концом мира исламский Иса вернется на землю, уничтожит христиан, женится и умрет в Медине. (Заметим, что для нас данный персонаж исламской мифологии неотличим от антихриста, предсказанного в Библии). Появится антихрист Аль-Джадж. Наконец, ангел Исрафил затрубит в трубу, и все в мире умрет, а затем Аллах всех воскресит. Все люди предстанут перед Аллахом, и он будет судить их. Мусульманам представят их грехи, они признаются в них и будут прощены. Те, кто погиб на джихаде, войдут в рай, минуя суд. В судный день их раны раскроются, но вместо крови из них потечет мускус.

Остальные должны будут перейти через мост ас-Сират, ведущий в рай. Праведники спокойно перейдут через него (мусульмане верят, что переехать этот мост они смогут на жертвенном баране), а грешники (в первую очередь немусульмане) упадут в ад. Обитателей ада ожидает вечное мучение от огня, кипящего железа и сдирания кожи. Осуществлять пытку будут специальные ангелы. Но в конце концов все мусульмане ходатайством Мухаммеда будут выведены из ада. А праведники будут наслаждаться в райском саду множеством различных видов пищи, а также соитием с особыми существами — гуриями. При этом праведники будут наслаждаться созерцанием пыток немусульман. Это представление показывает дьявольскую жестокость исламского лжепророка.

Но и в раю люди не будут видеть Бога (по одному из хадисов, Аллах будет видим в раю, как луна в облачную ночь) и навсегда останутся рабами. Сама возможность усыновления отвергается исламом как злейшая ересь.

Очевидно, что и такое представление является грубейшим искажением Откровения. Главное, на что надеялись и ветхозаветные пророки и святые христианства— соединение с Творцом, — объявляется совершенно невозможным. На наш взгляд, исламский рай вполне может быть одним из отделений настоящего ада. Ведь некоторые святые видели, что развратники после смерти пребывают в состоянии постоянного блуда, вызывающего у них самих отвращение. То, что Мухаммед описывал как идеал, встречается уже на земле как различные формы беснования. В «Достопамятных сказаниях о жизни пустынных отцов» приводится случай, когда бесноватый мог съесть быка и оставался голодным (в медицине такой феномен называется булемией). Чем не описание блаженства мусульман, имеющих на каждый день три миллиона перемен блюд, причем каждому из них дается сила все съесть. А нимфомания и факты нападения блудного беса идентичны ожидаемому совокуплению исламистов с 124 тысячами гурий на каждый день.

Последний пункт веры мусульман — вера в предопределение — является, пожалуй, самым возмутительным пунктом их заблуждений. Согласно этой доктрине, сам Аллах является творцом всех поступков, как злых, так и добрых. Он дает силу убийце убить, прелюбодею — прелюбодействовать. Но при этом он же и накажет за это злодеяние. Неразрешимой является проблема согласования предопределения со свободной волей людей. Большую часть свободы мусульмане отвергают. Они утверждают, что от человека зависит только желание, а реализация его — от Аллаха. Но возникает вопрос: если Аллах творит все, то как и само желание может быть исключением? Сама доктрина предопределения является, пожалуй, одной из самых разлагающих для духовной жизни мусульман. Именно опираясь на нее мусульмане одобряют гибель во время терактов множества невинных людей. По сути, это учение является точным воспроизведением сатанинской лжи, прозвучавшей в раю. Ведь уже тогда Адам попытался объявить Бога источником греха.

Итак, мы видим, что в области вероучения ислам радикально извращает Откровение. И, что самое опасное, он облекает сатанинские идеи в знакомые христианам слова, чтобы сходством оболочки привлечь людей во тьму смерти.

Другие столпы ислама также отделяют его от религии Бога Творца. Второй столп: исполнение обряда поклонения — намаза — многими ошибочно считается аналогом христианской молитвы. Однако это совсем не так. В исламском богословии намаз — это строго регламентированный обряд обожествления Аллаха. Малейшее нарушение ритуала приводит к тому, что намаз считается недействительным. Аллаху не очень интересно состояние сердца молящегося (может быть, потому, что он не знает сердец. Ведь ангелы не властны смотреть на мысли людей). Тут мы видим аналогию с идолопоклонством. И там и тут важнее ритуал, чем состояние сердца. Ты можешь не верить в идола, но обязан соблюсти ритуал.

Третий столп — обязательный налог на бедных (закят) — часто путают с милостыней. Но это скорее ее противоположность. Во-первых, закят не бывает тайным, вопреки слову Господа. Во-вторых, подается закят только мусульманам или тем, кого можно при помощи денег привлечь к исламу. Мы знаем, что так же поступают и сектанты, делающие добрые дела ради проповеди своего заблуждения.

Четвертый столп — хранение поста месяца Рамадан — также имеет мало общего с постом православных. Мало того что распространяется он только на светлое время суток. Он также не связан с борьбой со страстями, действующими внутри человека (вообще неведомой мусульманам, кроме суфиев). Этот пост бесполезен для души, а часто и просто вреден, ибо порождает самоуверенность и гнев.

Пятый столп — паломничество в Мекку (хадж) — вообще является пережитком язычества. Поклонение метеориту (черному камню), ритуальные жертвы, кидание камнями в столбики с уверенностью, будто побиваешь сатану, — все это бессмысленный и суеверный ритуал. Не случайно во время хаджа каждый год погибает множество людей. Так враг издевается над своими несчастными жертвами. Если ветхозаветные обряды готовили людей к приходу Господа и возвещали Его спасение, то обряды хаджа, не основанные на Откровении, совершенно бессмысленны.

Очень многие проповедники ислама считают шестым столпом обязанность джихада — священной войны с неверными. Про человекоубийственную злобу дьявола, стоящую за этим повелением, мы скажем ниже.

Таково православное отношение к тому, что объединяет подавляющее большинство мусульман мира. Мы видим, что нет практически ничего общего в вере между христианами и мусульманами. Под одним и тем же словом подразумеваются совершенно разные реальности. Поэтому все разговоры об «общих авраамических корнях», «двух путях к одному Богу» должны быть оставлены.

Но перейдем к описанию тех особых течений ислама, которые есть в современном мире.

Обиходный ислам тюркских народов

Большая часть тюркских исламских народов России (кроме азербайджанцев) придерживаются суннитского направления ислама ханифитского мазхаба. Эта правовая школа допускает широкое использование обычного права, поэтому она легко приспосабливается к местным условиям. В начале XIX века возникло движение джадидизма, провозгласившее фактический отход от норм шариата. Признавая основные нормы ислама (пять столпов и акида), они утверждают необязательным исполнение шариата и признают необходимость светского образования. «Главное — это иметь шариат в душе», — говорят джадидиты. Многие из них даже перешли к исполнению обряда намаза не на арабском, а на национальном языке. Это движение аналогично обновленчеству в Православии. Так возник «мягкий ислам», воспринявший во многом нормы западного гуманизма.

Как к нему должно относиться христианам? Конечно, отрицательно. Ведь «мягкий ислам» разлагает само понятие абсолютной истины. Не случайно, что адепты этого течения чаще всего придерживаются концепции «все религии — путь к одной вершине». С этой точки зрения практически невозможно вести диалог. Все будет потоплено в мягкой вате соглашательства и пропаганды «терпимости».

При этом, как замечали еще миссионеры XIX века, ислам среди татар, башкир или казахов настолько смешан с язычеством, что трудно отделить одно от другого. С другой стороны, на бытовой почве тюркский ислам испытал влияние и христианства. После советского правления эта ситуация еще усугубилась. Многие муллы почти не знают арабского языка. Все религиозность мусульман часто сводится к празднованиям исламских праздников и приглашению мулл на свадьбы и похороны. Равиль Гайнуддин жалуется, что татары фактически отошли от ислама. При этом очень развиты боязнь порчи и сглаза. Не случайно, что среди мусульман развит оккультизм. Это связано также с сильным влиянием, оказываемым на тюрский ислам суфийской традицией.

Но при этом ислам сочетается у татар и башкир с чувством национальной самотождественности («Если ты татарин, то должен быть мусульманином», — часто говорят представители «мягкого ислама»). А на волне национализма, захватившего тюркские народы, усиливается освоение ислама среди этих народов. Часто ислам используется для обоснования пантюркизма, идеологии создания Великой Турции, включающей всех тюрок. Ведь благодаря идеологии джадидизма тюркский ислам во многом отличается от ислама арабского. (Так что часто сторонники арабского ислама не признают джадидитов полноценными мусульманами.) И, таким образом, несмотря на интернационализм, свойственный мусульманству, появляется возможность утвердить самотождественность татарского и других народов не только среди христиан, но и среди самих мусульман.

Здесь стоит заметить, что сам феномен национализма является проявлением проклятия Вавилонской башни (Быт. 11). Имея частичную правоту в том, что указывает на особые таланты, присущие каждому народу, он греховным образом игнорирует Божие повеление всем людям войти в Единую Вселенскую Церковь. Национализм игнорирует изначальное единство человеческого рода и часто провоцирует междоусобные схватки. Он культивирует многочисленные обиды на другие народы и приводит к сознанию национальной исключительности. По слову архимандрита Софрония (Сахарова), «если национализм нельзя преодолеть, значит, дело Христово не удалось».

Традиционный ислам народов Кавказа

Резко отличается от тюркского ислама. Большая часть мусульман на Кавказе придерживаются шафиитского мазхаба, придающего особое место согласию исламских ученых. Среди кавказских мусульман огромную роль имеют не только нормы шариата (которые все же исполняется строже, нежели среди тюрок), но требования адата — обычного права, в основах своих языческого. Поэтому среди мусульман Кавказа так распространен обычай кровной мести и многие другие обычаи, не соответствующие нормам шариата. Кроме того, из-за распространения суфизма среди кавказцев распространен культ святых мест, культ святых и некоторые другие обычаи, не согласующиеся с духом ислама. Впрочем, это свойственно не только кавказскому исламу. В самом арабском мире под воздействием суфизма в народе существует глубокое убеждение, что свет Мухаммеда предсуществует миру. Так невольно душа людей показывает необходимость в Боговоплощении.

С православной точки зрения заслуживает внимания сохранение тех обычаев, которые, противореча Корану, тем не менее сохраняются в народном благочестии. Ведь если Бог не стал человеком, то обожение невозможно, люди не могут стать сынами Божиими. Поэтому, строго говоря, никакая святость в исламе невозможна. Человек может стать покорным рабом, но никогда не станет причастником славы Божией. Однако душа не может с этим смириться, и потому появляется культ святых, показывающий, что ислам чужд человечности и не отвечает на глубочайшие запросы человеческого духа.

Что же касается сохранения элементов язычества в среде мусульман, то это свидетельствует об отсутствии в исламе внутренней преображающей силы, способной изгнать дьявола из сердец людей и из народной жизни.

Русский ислам

Новым явлением, появившимся впервые в конце XX века, надо назвать факт перехода некоторых русских в ислам. Связан он и с Афганской и Чеченскими войнами, когда многие безбожники, проникнувшись комплексом вины, принимали веру своих врагов. С другой стороны, до России докатилась волна с Запада, где многие, увлекшиеся идеями Рене Генона и других традиционалистов, стали искать в исламе (особенно в его суфийском направлении) древнейшую духовную традицию. В России их идеологом является Гейдар Джемаль. Часто в ислам переходят те, кто вступает в брак с мусульманами (формально по шариату для женщины-христианки это не обязательно, но очень желательно, а христианин может жениться на мусульманке только приняв ислам). Также ведется активная работа исламских миссионеров по совращению христиан в мусульманство. Особенно усердствуют здесь представители чеченской диаспоры и арабские проповедники. Учитывая эту неоднородность новообращенных, невозможно однозначно охарактеризовать это направление. Те, кто перешел в ислам из-за женитьбы, обычно придерживаются того направления ислама, к которому принадлежат новые родственники. А те, кто присоединился к исламу сам, обычно принимают ислам в наиболее радикальной форме — ваххабизм. Традиционалисты придерживаются суфизма, густо перемешанного с оккультизмом.

При этом большинство новообращенных являются антиглобалистами и социалистами. Они считают своим величайшим врагом иудео-христианскую цивилизацию, которую они отождествляют с Америкой. Не случайно, что многие патриоты симпатизируют исламу, хотя он и поставил перед собой задачу уничтожения России и превращения ее в Московский Халифат. Именно среди русских мусульман возникла эта идея. Обычно называется 2032 год как дата окончательного превращения России в шариатское государство. Если это произойдет, то Православие в России испытает гонения, по суровости сравнимые с коммунистическими. Думаю, что всякий, кто пропагандирует союз с исламом, должен быть готов ответить за кровь тех, кого убьют агаряне. Ведь уже сейчас именно русские мусульмане отличаются необычайной ненавистью ко Христу, апостолам, Евангелию и Церкви. Несмотря на официальное почитание Исы, они собирают как можно больше компромата, желая унизить Господа. Особую же ненависть вызывает у них, как и у евреев, апостол Павел, которого они обзывают самыми отвратительными словами. Особо отличается этим бывший протоиерей Али Полосин.

Какова православная оценка русского ислама? Это гнусное предательство Христа Спасителя. Если совращенные были крещеными, то они подпадают церковной анафеме. За их беззаконие они будут наказаны вечным огнем.

Ваххабизм

Основным «козлом отпущения», которой должен отвечать за террористический облик ислама, стал ваххабизм. Некоторые авторы (как исламские, так и светские) назвали ваххабизм псевдоисламской сектой. Но так ли? Что это за страшная секта? Ваххабизм — это движение суннитского ислама ханбалитского мазхаба, государственная идеология Саудовской Аравии. Основателем ваххабизма был Мухаммед ибн Абд аль Ваххаб (1703–1787). Он провозгласил возвращение к изначальному исламу и верность только Корану и Сунне. Аль Ваххаб выступил против культа святых, пережитков язычества. Он, как и западные проповедники в духе Уэсли и пуритан, выступал против пышности и роскоши и призывал к скромной жизни. Под влиянием его проповеди и основываясь на авторитете «пророка» Мухаммеда, он и его последователи создали агрессивное государство саудидов. Они завоевали большую часть Аравийского полуострова (включая священную Мекку, где они очистили от всех украшений камень Каабы) и организовали ряд завоевательных походов против Сирии и Ирака. С ваххабизмом были связаны мюриды Шамиля на Кавказе.

Ваххабиты были разгромлены турками. В XX веке ваххабиты воссоздали королевство Саудовскую Аравию. В этом движении возродились все особенности раннего ислама, в особенности практика перманентной священной войны (джихада). Именно поэтому все террористы обычно в СМИ называются ваххабитами. Хотя, например, иранская революция по определению не может быть ваххабитской, ибо Иран — шиитское государство.

Некоторых «мягких» мусульман (джадидитов) возмущает в ваххабитах отождествление всех, кто не придерживается этого учения, как кафиров (неверных), что приводит к тому, что на джихаде убивают не только христиан, но и мусульман. Впрочем, истребительные войны и против своих сопровождают ислам практически с самого начала, с раскола между суннитами и шиитами.

Современный ваххабизм часто высказывает себя как движение социальной справедливости, наподобие социализма. Впрочем, социалистическая идеология всегда вызывала особый отклик к сердцах мусульман. Не случайно, что в очень многих странах арабского мира до сих пор правят социалистические режимы.

Ваххабизм является чистым законничеством. В нем нет места для исправления сердца. Это попытка достигнуть спасения при помощи внешних дел. А так как это сделать невозможно, то, чтобы затушить голос совести, мусульмане разжигают в себе фанатизм. Тот же источник и социалистических доктрин. Не видя в себе действия Царства Божия, не желая преображать свою плоть и дух, мусульмане наивно пытаются создать на земле царство справедливости. Но попытка эта глупа. Она порождает только зависть и растрачивает силы в погоне за недостижимым идеалом. Да и как он может быть достигнут, если смерть пожрет все достижения людей. В непреображенном мире нельзя избавиться от тенет зла иначе, как только получив от Бога исцеление сердца. А дает его только Христос Спаситель.

Шиизм

Особым направлением ислама является шиизм, возникший в результате раскола исламской уммы по вопросу о том, кто должен возглавлять общину. В СНГ шиизма придерживаются азербайджанцы. Шиитским государством является Иран и, видимо, скоро станет Ирак. Шииты были сторонниками родственника Мухаммеда — Али. Они были убеждены, что духовный лидер имам должен был нести некий духовный свет. Шиизм признает двенадцать имамов, начиная с Али, последний из которых исчез в X веке, но должен вернуться (его называют Махди). Ряд шиитов принимает Коран в расширенной версии (с 115 сурой).

В шиизме развит культ мучеников, особенно Али и его внука Хасана, в день убийства которого многие шииты занимаются самоистязаниями.

Для православных представление о неких хранителях духовного света и знания, не имеющих благодати Святого Духа, близко к магии и шаманизму. Не случайно представление об имамах как посвященных генетически связано с иудейским гностицизмом. Именно тайным обществам свойственно представление, что есть разные типы людей, отличающихся уровнем знания. В Церкви, по слову Господа, нет такого знания, которое бы сообщалась только посвященным. Все Евангелие одинаково принадлежит всем христианам.

Что же касается шиитского культа мучеников, то он также отличен от христианского. Для православных мученик — свидетель Христовой победы над смертью, а для мусульман — просто страдавший за Аллаха человек, который желает получить хорошую награду. Само же самоистязание бессмысленно и бесполезно, ибо не приносит никакой пользы душе человека. Какой смысл в том, что ты изувечишь себя, а потом пойдешь к проститутке (у шиитов это «временный брак»)? Это самомучение тождественно тому самобичеванию, которое делали с собой жрецы Ваала, посрамленные пророком Ильей. Лишь демоны радуются пролитию человеческой крови в честь того, кто убивал христиан (Али — один из первых мусульман-гонителей).

Исламский расизм

Нельзя пройти мимо того, что в исламе существует проблема расизма. В Америке целое движение «Черных мусульман» (самый известный из них — Мухаммед Али) выступает с идеологией, будто людьми являются только негры. По их мнению, все пророки (в том числе и Христос, и Мухаммед) были неграми. Белые объявляются недочеловеками, извратившими откровение Аллаха.

Но это явление не является чем-то выдающимся. Подобным образом и для арабов-мусульман (особенно ваххабитов) исламисты-неарабы — люди низшей категории. В России новообращенные мусульмане стараются копировать арабов. И это не случайно. Ведь согласно шариату идеалом поведения являются поступки Мухаммеда, который освятил своим примером арабский быт VII века. Тем более арабский язык считается вечным (как язык Корана), на котором будут говорить в раю. Так что на самом деле любой последовательный мусульманин рано или поздно скатывается к клону дикого кочевника полуторатысячелетней давности.

Одним из плодов расизма является работорговля, широко распространенная и до сих пор в странах ислама. В большинстве исламских стран работорговля официально была запрещена под жестким давлением Запада (о жестокая глобализация, разрушающая основы национальной культуры!) только в 1970–1980 годах. Но несмотря на это, никто этого запрета не соблюдает. В 2001 году западные правозащитные организации выкупили из рабства в шариатском Судане более четырех тысяч человек. Причем выяснилось, что три четверти женщин (в том числе и замужних) подвергались регулярным изнасилованиям. И это не какое-то нарушение. Ведь согласно Корану любая невольница является сексуальной собственностью господина. Сам Мухаммед не одобрял освобождения рабов, считая, что этим мусульманин подорвет свое благосостояние. Именно в исламе корень рабства, распространенного на Кавказе.

Ислам и насилие

Одной из главных примет ислама, его «визитной карточкой» является священная война — «джихад». Беслан и Нальчик, Москва и Лондон, Нью-Йорк и Волгодонск свидетельствуют о чудовищной жестокости исламистов. Эта ситуация сопровождает всю историю мусульманской религии, начиная с Мухаммеда.

Часто, используя свое «право на ложь», мусульманские агитаторы говорят, будто ислам запрещает убийство, а «терроризм не имеет ни религии, ни национальности». Исходя из этого, приведем ряд цитат Корана, прямо призывающих от имени Аллаха к массовым убийствам:

«А когда закончатся месяцы запретные, то избивайте многобожников, где их найдете, захватывайте их, осаждайте, устраивайте засаду против них во всяком скрытом месте… Но если они обратились, исполняли молитву и давали очищение, то освободите им дорогу» (сура 9, 5);

«О, пророк! Борись с неверными и лицемерами. Будь жесток к ним! Их убежище — геенна, и скверно это возвращение!» (сура 9, 73);

«И убивайте их, где встретите, и изгоняйте их оттуда, откуда они изгнали вас: ведь соблазн — хуже, чем убиение!» (сура 2, 191);

«А когда вы встретите тех, которые не уверовали, то — удар мечом по шее. А те, кто убиты на пути Аллаха — никогда Он не собьет с пути их деяний и введет их в рай, который дал им узнать» (сура 47, 4–5);

«И сражайтесь с ними, пока не будет более искушения, а вся религия будет принадлежать Аллаху» (сура 2, 193).

Подсчитано, что Коран содержит более пятидесяти призывов к джихаду. Шариат четко описывает нормы священной войны. Вся планета делится на две части— «земля мира», где исполняются нормы шариата, и «земля войны», где эти нормы не исполняются. С государствами «земли войны» нельзя заключать мирного договора, а только перемирие, которое будет нарушено, как только будет удобно мусульманам. Во время джихада можно использовать все способы убийства, включая отравление колодцев. Все многобожники должны быть уничтожены, а их женщины и дети — обращены в рабство. Мухаммед установил таксу на выкуп заложника. Христиане и иудеи уничтожаются как многобожники в том случае, если мешают мусульманам завоевывать их земли. Но после завоевания они могут существовать в том случае, если будут платить специальный налог (джизву). Его размер колебался от 80 до 150 процентов дохода. В Турции существовал особый налог на христиан — налог на мальчиков, которых забирали и насильно обращали в ислам. В том случае, если немусульмане публично выскажут сомнения в посланничестве Мухаммеда, они подлежат смертной казни.

Как с православной точки зрения оценить эти зверства? Ответом может быть только одно: это страшное действие древнего врага — сатаны. Он изначальный человекоубица, услаждающийся пролитием человеческой крови. Христовы ученики донесли Евангелие, опираясь лишь на силу Божию, и проливали не чужую, а собственную кровь. Творец, создавший людей свободными, не желает, чтобы люди служили Ему под угрозой смерти.

Часто мусульмане пытаются доказать, будто джихад аналогичен священной войне пророка Моисея и св. Иисуса Навина. Но разница очевидна. Во-первых, полномочия Моисея и Иисуса были подтверждены великими чудесами, а Мухаммед — очевидный самозванец, не представивший никаких свидетельств своего посланничества. Во-вторых, война в Ханаане должна была истребить только хананеев. Бог специально оговорил ряд народов, с которыми евреями было запрещено воевать. Так был поставлен предел попыткам истолковать Божию волю расширительно. Лишь опустившиеся в глубины зла хананеи должны были быть уничтожены (как Сам Бог истребил жителей Содома). Напротив, пришельцы имели те же права, что и коренные жители. Никто из язычников не должен был по Закону насильно обращаем в иудаизм. Так что джихад— это не повеление Бога, а внушение дьявола, губящего обманутых им. Именно в этом страшном внутреннем разрешении на убийство корень той резни, которая сопровождает всю исламскую историю. «Мужей крови и льсти гнушается Господь» (Пс. 5:7), — сказал пророк Давид.

Ислам и Православие

При таких принципиальных расхождениях между исламом и православным христианством не удивительно, что мирное сосуществование этих религий было возможно только при сильной христианской или хотя бы светской власти. Память христиан хранит страшные преследования, перенесенные ими от рук мусульман в течение многих столетий. Страшный геноцид XX века в Турции только укрепил страшные опасения православных. Множество молитв нашего богослужения просят Бога, Богородицу, архистратига Михаила и святых избавить нас от мусульманского владычества. До Октябрьской революции в молитвословах печаталось прошение об избавлении от «богомерзкого агарянского царства».

Но наше время создало новые перспективы в деле взаимоотношения ислама и христианства. Исламское общество разрушается Промыслом Бога. В результате впервые за много веков появилась возможность широкой миссии среди мусульман, не осложненной всей системой шариата. Если мы пренебрежем этой возможностью, будь то из-за терпимости или боязни, то Бог не простит нам этого. Ведь у Него и до сих пор есть овцы и среди мусульман, а наша трусость мешает им войти во двор Небесного Отца. Недаром же Давид предсказывал, что Христу «цари Аравии и Сава дары приведут» (Пс. 71:10). Разве не являются эти слова ободрением нам в надежде на Божие решение исламского вопроса?

ИСЛА́М (от араб. – покорность, предание себя [Единому] Богу), одна из мировых религий, вторая по численности после христианства. Вместе с иудаизмом и христианством относится к монотеистическим, т. н. авраамическим религиям. Основатель И. – Пророк Мухаммед. Он создал первую общину последователей И., получивших имя мусульман («покорных [Единому] Богу»). Гл. священным текстом служит Коран – Божественное учение, ниспосланное Мухаммеду в Откровении через ангела Джибрила. Второй важнейший источник вероучения, права и религ. обрядности И. – Сунна, представляющая совокупность преданий (хадисов) об изречениях и деяниях Пророка.

Возникновение

И. появился в 7 в. в условиях общего кризиса языческого мировоззрения кочевых и земледельческо-торговых обществ Сев. Аравии при переходе от древности к Средневековью. Быстрой исламизации региона способствовали распад к 5 – нач. 7 вв. древних государств [Набатеи, Пальмиры, Сабы, Химьяра (Химйара), царств Киндитов, Лахмидов и Гассанидов], захват кочевниками-скотоводами пограничных оазисов, появление союзов оседлых жителей и кочевников, в которых росло влияние прорицателей (кахин), известных ещё в доисламской Аравии. Мн. языческие культы пришли в упадок, вместе с тем некоторые племенные божества приобрели общеаравийское значение (Аллах, аль-Лат, Манат, аль-Узза). В разделённой между племенами Внутренней Аравии особую роль стали играть «заповедные территории» (харам), сочетавшие функции святилища и места проведения ярмарок (мавасим) и обладавшие правом убежища. Одним из таких центров была родина И. Мекка.

Архив БРЭ

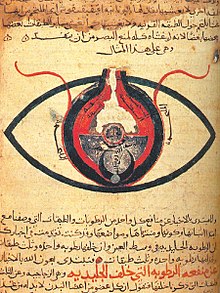

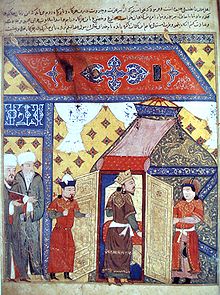

«Пророк Мухаммед у Каабы». Миниатюра кон. 16 в. Музей дворца Топкапы (Стамбул).

Наряду с разными сектами христианства и иудаизма в доисламской Аравии была развита автохтонная монотеистич. традиция. На северо-западе уже в 6 в. она была представлена ханифами, отрицавшими многобожие и поклонение идолам. Среди иудаизированного населения Йемена и Йамамы возникло течение рахманитов, противопоставлявших языческим племенным божествам единого Бога Рахмана. К нач. 7 в. оба течения слились в аравийском пророческом движении. При жизни Мухаммеда в Аравии было не менее пяти пророков. Пророческая деятельность Мухаммеда, приведшая к возникновению И., была закономерным следствием этих общих тенденций.

Вероучение

Мечеть Омейядов в Дамаске с ракой Иоанна Крестителя. 706–715.

Фото В. М. Паппе

Осн. положений исламского вероучения (см. Акида) пять: вера в Бога, ангелов, в божественные Писания, пророков и Судный день (Коран, 1:3/4; 2:285; 4:135/136). Сунниты присоединяют к ним веру в божественное предопределение (см. Бог в исламе). Важнейшей особенностью разных толков шиизма является учение об имамах – преемниках Мухаммеда.

И. настаивает на строгом единобожии (таухид). Приравниваемое к неверию многобожие (араб. «ширк», букв. – предание Богу соучастников) объявлено в Коране величайшим и непростительным грехом (112). В христианских догматах Троицы и Боговоплощения И. видит отступление от монотеизма. По Корану, Бог – Творец всего сущего. Запредельный миру, вместе с тем Он присутствует всюду. Бог непрестанно промышляет о своих творениях и постоянно опекает их как Всемилостивый и Милосердный Владыка. С непокорными, особенно с неверующими (куффар, араб. мн. ч. от кяфир), Он грозен и суров.

И. учит, что Бог сотворил мир, где каждая вещь свидетельствует о Его абсолютном единстве, премудрости и совершенстве. Из Ветхого Завета в исламское вероучение перешёл ряд важнейших сюжетов и понятий [семь дней творения, человек как его венец (Коран, 41:8–11/9–12), изгнание «прародителя человечества» Адама и его жены Евы (Хаввы) из рая за нарушение заповеди вкушать от Райского древа и пр. При этом, согласно Корану, Господь принял покаяние прародителей и простил им прегрешение (2:36/38; 20:115/114)].

Ангелы (малаик) в мусульм. космологии служат хранителями божественного Престола и вестниками Аллаха, через которых Он обращается к людям. К старшим в небесной иерархии принадлежат четыре ангела, перешедшие в И. из иудаизма, но наделённые некоторыми новыми функциями: Джибрил хранит и несёт пророкам божественное Откровение; Микаил печётся о пропитании всех тварей; ангел смерти Израил изымает души умерших; ангел Небесной трубы Исрафил возвещает о наступлении Судного дня и воскресении из мёртвых. К каждому человеку приставлены ангелы-хранители и ангелы, записывающие его деяния. Грозные ангелы Мункар и Накир допрашивают умерших в могилах, определяя грешников на загробные мучения, а праведникам уготавливая вечное райское блаженство. Раем ведает ангел Ридван, адом – ангел Малик.

Мир духов, помимо ангелов, составляют джинны и демоны. Наряду с людьми Откровение Корана обращено к ним (55:12/13–15/16, 18, 21, 23, 25, 28, 31–77). Прародитель-предводитель демонов Сатана, или Иблис, в Коране выступает как падший джинн. Он отказался преклониться перед созданным Богом Адамом, за что проклят Богом, но получил власть искушать людей до Судного дня. Кроме Иблиса, Коран упоминает двух других падших ангелов – Харута и Марута (2:96/102), как и в книге Бытие (6:4), бравших себе в жёны дочерей человеческих.

Учение о божественном Откровении через пророков (нубувва) составляет одно из центр. положений догматики И. Бог шлёт людям посланников, открывая через них свои таинства и волю, направляя на ведущий к спасению в раю истинный путь (ас-сырат аль-мустакым). Пророчество касается всего мира людей и духов. Согласно Корану, каждому народу был дарован хотя бы один посланник. Миссия основателя И., Пророка Мухаммеда, обращена ко всем племенам и народам. Пророчество едино, но отличается нравственно-правовыми и культово-обрядовыми нормами. В Коране упоминается ок. 30 пророков, первым из которых был Адам, а последним – «печать пророков» Мухаммед. В их число И. включает осн. персонажей Ветхого и Нового Завета: Адама, Еноха (Эздра), Ноя (Нух), Авраама (Ибрахима), Исмаила, Исаака, Иакова (Якуб), Иосифа (Юсуф), Моисея (Муса), Давида (Дауд), Соломона (Сулейман), Захарию, Иоанна Крестителя (Яхйа). Среди пророков – также герои доисламской аравийской мифологии Худ и Салих. Ряд доисламских пророков венчает часто фигурирующий в Коране Иисус Христос (Иса ибн Марйам).

Божественное Откровение пророкам обычно получает форму Писаний, общий оригинал которых, по учению И., вечно хранится на небесах в «Святохранимой скрижали». Мусе была ниспослана Тора, Дауду – Псалтирь, Исе – Евангелие, Мухаммеду – Коран. Согласно мусульм. богословской доктрине, все прежние Писания не сохранили своей исконной чистоты, со временем подверглись искажениям. Только Коран, восстанавливающий и довершающий их, оберегаем Богом от подобной участи.

За концом света, согласно Корану, последует Судный день. Среди свидетельств его приближения мусульм. эсхатологич. предание называет исчезновение святилища Каабы в Мекке, забвение Корана, появление Даджжаля, с которым вступит в бой «ведомый Аллахом» Махди, второе пришествие Исы и пр. Бог будет допрашивать людей, каждого в отдельности, а для подсчёта добрых и дурных деяний человека установят Весы. После этого все судимые пройдут по переброшенному над адом мосту Сырат, который «тоньше волоса и острей меча». Его образ пришёл в И. из зороастризма. Грешники низвергнутся в огонь ада, праведники перейдут его и отправятся в сады рая.

В аду (араб. «ан-Нар», букв. – огонь) отверженные скованы цепями, терпят муки от раскалённой смолы и огня. Пищей им служат плоды отвратительного дерева Заккум, а питьём – прожигающий внутренности кипяток. Обитатели рая (араб. «аль-Джанна», букв. – сад) наслаждаются всеми желанными благами, в т. ч. изысканными яствами (включая вино, от которого не пьянеют), обществом собственных жён и райских дев-гурий. Телесные удовольствия венчаются духовными, высочайшим из которых является созерцание лика Божия. Освобождению от адских мук или облегчению их поможет заступничество праведников и особенно пророков. После более или менее продолжительного пребывания в аду, милостью Божией, осуждённые перейдут в рай. Это относится прежде всего к грешникам из числа мусульман, а за ними – к последователям и др. монотеистич. религий.

Религиозные практики

Архив БРЭ

Мечеть Селимие в Эдирне. Архитектор Синан. 1569–75.

Пяти основным принципам вероучения соответствуют пять главных религ. обязанностей правоверного мусульманина – исповедание веры, молитва, очистительная милостыня в пользу бедных, пост и паломничество, – известные в мусульм. традиции как пять столпов веры.

Исповедание веры

Исповедание веры, или шахада (араб., букв. – свидетельство), заключается в произнесении сакральной формулы: «Свидетельствую, что нет божества, кроме Бога, и Мухаммед – посланник Божий». По значению это действие аналогично христианскому крещению и служит средством обращения в И. Чтобы стать мусульманином, по букве шариата, взрослому достаточно с верой в сердце вслух произнести шахаду. Шахада входит в состав повторяющихся по несколько раз формул пятикратной ежедневной молитвы. К ней рекомендуется часто прибегать и вне обязательных молитв. При рождении ребёнка и перед кончиной следует произнести шахаду.

Молитва

Архив БРЭ

Медресе Улугбека в Самарканде. 1417–20.

Молитва (араб. – салят, перс. – намаз) – главная обязанность человека перед Богом. Её положено совершать пять раз в день: на рассвете, в полдень, перед наступлением вечера, после заката и перед сном. Она состоит из ряда поклонов (ракат), сопровождаемых произнесением на араб. яз. молитвенных формул, прежде всего вводной суры Корана Фатиха. Перед молитвой верующие разуваются и совершают ритуальное омовение рук, лица и ног. В некоторых случаях (после месячных у женщин, супружеского акта и пр.) требуется полное омовение всего тела. Намаз рекомендуется совершать совместно, предпочтительно в мечети. Но его можно отправлять в любом ритуально чистом месте, символически отделившись от внешнего мира при помощи коврика, на который встаёт верующий (араб. – саджжада, тюрк. – намазлык). При совместной молитве один из собравшихся руководит ею как имам.

Каждую пятницу мусульмане совершают особую совместную полуденную молитву в мечети. Богослужение сопровождается проповедью (хутба), обычно морального, социального или политич. содержания, читаемой как на арабском, так и на местных языках. Кроме обязательных молитв, в И. имеется целый ряд необязательных.

Средоточием религ. жизни в И. служит мечеть, представлявшая собой в первые века существования И. также центр культурной и общественно-политич. жизни мусульм. общины, совмещая функции молельного дома, религ. школы, кафедры для обращений властей к народу, зала заседаний шариатского суда, денежной кассы, клуба и гостиницы. Собственно храмом мечеть стала позднее, постепенно лишившись светских (политич. и юридич.) функций. В отд. учреждение обособились высшие религ. школы (медресе), хотя местами сохранилось обыкновение основывать школу при мечети. Мусульм. традиция не выработала обряда освящения здания мечети, но сакральный характер её пространства подчёркивает ряд устоявшихся обрядов: ритуальное очищение верующих перед посещением мечети, снятие перед входом в неё обуви. В крупных населённых пунктах действуют неск. мечетей, из которых главной – соборной или пятничной – называют мечеть, где община собирается на пятничную молитву.

Милостыня

Милостыня (закят) – главная обязанность верующего мусульманина перед ближним. Она представляет собой своего рода ежегодный налог в пользу малоимущих с любого имущества и плодов земледелия, не предназначенных для удовлетворения личных нужд или ведения хозяйства. Помимо обязательного закята, И. поощряет добровольную милостыню (садака). Система исламской благотворительности включает также пожертвования на нужды богоугодных заведений – мечетей, школ и медресе, госпиталей, сиротских и странноприимных домов в форме вакфов.

Пост

Пост (араб. – саум, тюрк. – ураза) предписан верующим в течение месяца рамадан, священный характер которого в И. связан с тем, что в ночь 27 рамадана (Лейлят аль-кадр) началось ниспослание Корана Пророку Мухаммеду. На уразу следует воздерживаться от любой пищи, питья, курения и иных чувственных наслаждений (включая супружеские отношения) в течение светлого времени суток. Кроме общеобязательного поста в рамадан, у мусульман имеются разл. индивидуальные посты – по обету (назр), во искупление грехов (каффара) или из благочестия.

Паломничество

Архив БРЭ

Кааба во время хаджа.

Паломничество (хадж) в Мекку предписано хотя бы раз в жизни тем, кто в состоянии совершить его, обладая здоровьем и необходимыми материальными средствами (включая обеспечение семьи на время своего отсутствия). Другим обязательным условием, без которого мусульманин может отказаться от паломничества, считается безопасность пути. Между 7 и 10 зу-ль-хиджа паломники совершают очистительные обряды у святынь И. в Мекке. В число рекомендуемых, но не обязательных действий входит посещение могилы Пророка в Медине. До арабо-израильских войн устойчивой традицией мусульм. пилигримов было включение в маршрут паломничества «святого города» Иерусалима (аль-Кудс). Совершивший хадж пользуется в мусульм. обществе особым уважением, получая почётное звание хаджи, а в некоторых регионах – право носить особую одежду, напр. зелёную чалму. Наряду с коллективным хаджем рекомендуется индивидуальное паломничество – умра, которое можно совершить в любое время года и которое включает в себя семикратный обход Каабы и пробежку между холмами Сафа и Марва в Мекке.

Религиозные запреты

В средневековом И. не было чёткой грани, разделяющей религию и право. Коран и Сунна содержат целый ряд нормативных предписаний, впоследствии развитых мусульманским правом (фикх), которое регулирует не только отношения между людьми, подданными и государством (муамалят), но также этические, религиозные и обрядовые обязательства верующего по отношению к Богу (ибадат). Вместе они составляют шариат, понимаемый как исламский образ жизни.

Детально разработаны обрядовые и правовые запреты. И. не дозволяет своим последователям употреблять в пищу свинину и мясо павших животных, алкогольные напитки и др. одурманивающие средства. Запрещены (харам) азартные игры, роскошь и ростовщичество. Как безусловное тяжкое преступление рассматривается распространённый в доисламской Аравии обычай заживо хоронить новорождённых девочек (Коран, 81:8). Коран ограничивает кровомщение, запрещает самоубийство и убийство (2:173/178; 4:33/29; 5:37/33 и др.), карает воровство отсечением кисти руки (5:42/38).

Религиозная этика и ритуал

Нравственное учение Корана родственно библейскому. Наряду с верой (иман) и признанием воли Божией (ислам) добродетель (ихсан) считается неотъемлемой составляющей религии (дин).

Мусульм. семейная этика не приемлет безбрачия, возводя брак в религ. обязанность и призывая наслаждаться радостями семейной жизни. Коран разрешает мужчине иметь до четырёх жён, если он будет «ровным» с ними, в частности если будет одинаково хорошо содержать их. Многожёнство встречается редко, а в ряде мусульм. стран ограничено законом (напр., взять вторую жену можно лишь с согласия первой). Брак в И. – договор, а не религ. таинство, откуда следует и относительная лёгкость развода. Заключение брака обычно совершается в присутствии духовных лиц (в доме невесты) и закрепляется чтением из Корана, но это не является непременным условием действительности брака.

Архив БРЭ

Мечеть Пророка в Медине. 630-е гг. Перестраивалась в 707–709, 1853/54, в кон. 20 в.

Мусульм. обряды перехода, связанные с рождением и смертью, различаются в зависимости от региона и эпохи, однако имеют общие черты: на 7-й день новорождённого нарекают именем, ему остригают волосы, раздают за него милостыню и приносят жертву. В тот же день или позднее (вплоть до 15-летия) над мальчиком совершают обряд обрезания. Происходящий из аравийского доисламского обычая, этот обряд выполняет роль инициации в мусульм. общество, равно как и женское обрезание, распространённое в отд. традиц. регионах И. (Африка, Вост. Кавказ). Тело умершего обмывают и заворачивают в саван. Над ним читают молитву в мечети (либо в её дворе). Как правило, хоронят усопшего в день его кончины, тело опускают в могилу без гроба и укладывают лицом по направлению к Каабе.

Святыни

Главные и общие для всех мусульман святыни сосредоточены в Мекке. Это прежде всего Кааба в центре Заповедной мечети (аль-Масджид аль-Харам), служащая духовным и культовым центром мусульм. мира. К ней совершают ежегодные паломничества, обращаются лицом во время молитвы. Первым строителем её считается Авраам, по другой версии, Адам. Возле Каабы расположены почитаемые мусульманами святые места, традиционно связываемые с легендарным патриархом арабов Исмаилом и его матерью Агарью. Второй по значению святыней является Медина – столица первого мусульм. гос-ва. Центром паломничества тут служит Мечеть Пророка с его усыпальницей (Масджид ан-Наби). Третьей по святости остаётся мечеть Купол скалы в Иерусалиме. Она отмечает место на скале, которого коснулась нога Пророка при его чудесном путешествии в небесный райский сад (мирадж). Там же находился Иерусалимский храм, в сторону которого обращались мусульмане на молитве, до того как Мухаммед принял Каабу в качестве кыблы. С Иерусалимом мусульм. предание связывает жития нескольких святых для мусульман пророков, от Дауда и Сулеймана до Яхйи и Исы.

Имеется ряд второстепенных святилищ общеисламского значения. В Хевроне, называемом Эль-Халиль в честь патриарха Ибрахима, известного в мусульм. предании как Халиль Аллах (араб. – Друг Божий), паломники посещают мечеть с гробницами Ибрахима, Исаака, Якуба и их жён. Шииты окружают особым почитанием города с гробницами своих имамов-мучеников: Эн-Наджаф и Кербелу (в Ираке), Мешхед и Кум (в Иране) и др. Для широких масс, как суннитов, так и шиитов, святынями служат усыпальницы древних пророков, видных богословов и суфиев. К ним совершают паломничества (зияра), испрашивая милости и благословения (см. Святых культ в исламе).

Календарь

Мусульманский религиозный календарь – лунный. Начало мусульм. летосчисления ведётся от года переселения Мухаммеда из Мекки в Медину в 622 (хиджра). День начинается с заката солнца и продолжается до следующего заката. Одна и та же лунная дата за 36 лет пробегает все дни солнечного года. Самым благословенным месяцем года считается девятый – месяц поста рамадан. В конце года совершается великое паломничество в Мекку, что отражено в названии двенадцатого месяца – зу-ль-хиджа (араб. – месяц хаджа). Четыре месяца – 1-й, 7-й, 11-й и 12-й – запретны для ведения войны. Из дней недели самым благословенным считается пятница – в этот день Бог сотворил Адама и ввёл его в рай; в пятницу укрощается пламя ада. После окончания полуденной пятничной молитвы и проповеди позволено вернуться к будничным занятиям. Пятница не всегда была нерабочим днём, но ныне она стала таковым во многих мусульм. странах. Ночь на пятницу является самой счастливой и благоприятной, особенно для бракосочетания.

Главные памятные даты религ. календаря: Новый год 1 мухаррема; Ашура 10 мухаррема (первая встреча Адама и Хаввы после изгнания из рая, выход Нуха из Ковчега, переход Мусой моря, у шиитов траур по мученической кончине имама Хусейна); День рождения Пророка Мухаммеда (мавлид – у суннитов падающий на 12, у шиитов на 17 раби аль-авваля); Вознесение Мухаммеда (мирадж) и его чудесное путешествие из Мекки в Иерусалим и на небеса в ночь на 27 раджаба; Ночь прощения (араб. – Ляйлят аль-бараа, перс. – Шаба-и барат) в середине месяца шабан; Ночь предопределения на 27 рамадана (Лейлят аль-кадр), определяющая, по мусульм. преданию, судьбы людей на следующий год; Праздник разговения (араб. – Ид аль-фитр, тюрк. – Ураза-байрам) по завершении поста в первые три-четыре дня шавваля; Праздник жертвоприношения (араб. – Ид аль-адха, тюрк. – Курбан-байрам) – три-четыре дня начиная с 10 зу-ль-хиджа (память о благом исходе истории с жертвоприношением сына Ибрахимом, совпадает с концом хаджа). Два последних являются главными праздниками в И., известны также как «большой» и «малый» праздники.

Разные направления и толки в И. имеют также особые памятные даты. Шииты отмечают 18 зу-ль-хиджа Праздник пруда (Ид аль-гадир) в память о дне, когда Пророк, как они полагают, назначил Али своим преемником около пруда Хумм. Торжества происходят и в годовщины смерти шиитских имамов. Памятные даты своих великих шейхов празднуют религ. братства. В некоторых странах эти торжества, как и годовщины местных святых, называют «духовной свадьбой» (урс). У некоторых мусульм. народов имеются праздники, связанные с солнечным календарём. Самый крупный из них – Науруз, иранский Новый год, совпадающий с началом весны 21 марта. В Турции братство Бекташия даёт Наурузу исламское истолкование, почитая его как день рождения Али ибн Аби Талиба.

Распространение и развитие

И. сыграл решающую роль в становлении араб. нац. характера и наднационального религ. сообщества мусульман (умма) в рамках Халифата. Его влияние испытали мн. народы и культуры ср.-век. Евразии. В ходе араб. завоеваний 7–9 вв. были исламизированы обширные территории в Передней Азии, Сев. Африке, Иране, Центр. Азии, Закавказье и на Сев.-Вост. Кавказе. С завоеванием в 1-й пол. 8 в. Пиренейского п-ова был создан очаг исламской цивилизации в Европе (аль-Андалус).

Характерной особенностью развития И. как религ. и идеологич. системы остаётся полемика разл. направлений и школ. В силу отсутствия в нём противопоставления религиозного (дин) и светского (дунйа), споры в равной степени затрагивали вопросы вероучения, права и политики. Политич. проблемы приобретали фундам. религ. значение, а вопросы религ. благочестия рассматривались в правовых категориях. Если на раннем этапе мусульман волновали правовые и обрядовые установления И., то на рубеже 7–8 вв. возник интерес к теоретич. богословским проблемам, прежде всего к истолкованию верховной власти (имам, халиф), веры (иман), смертного греха (кабира). С обсуждением этих понятий связана дискуссия о свободе воли и божественном предопределении (аль-кадар), соотношении божественной сущности и атрибутов, сотворённости Корана как слова Божия.

Расхождения по этим вопросам привели к созданию к сер. 8 в., по крайней мере, пяти религиозно-политич. группировок: суннитов, шиитов, хариджитов, мурджиитов и мутазилитов. Возникновение множества мнений, часто противоположных, служило постоянным поводом для взаимных обвинений в «заблуждении» и «неверии». Вместе с тем в И. не сложилось институтов узаконения догматов, подобных христианским Вселенским соборам, поэтому не возникло и ортодоксии. В нём изначально не было ни сословия духовенства, обладающего божественной благодатью, ни церковной организации. Часто встречающееся в немусульманских источниках понятие «мусульманское духовенство» носит условный характер, означая всю совокупность мусульм. духовной элиты либо её часть, признанную в том или ином государстве.

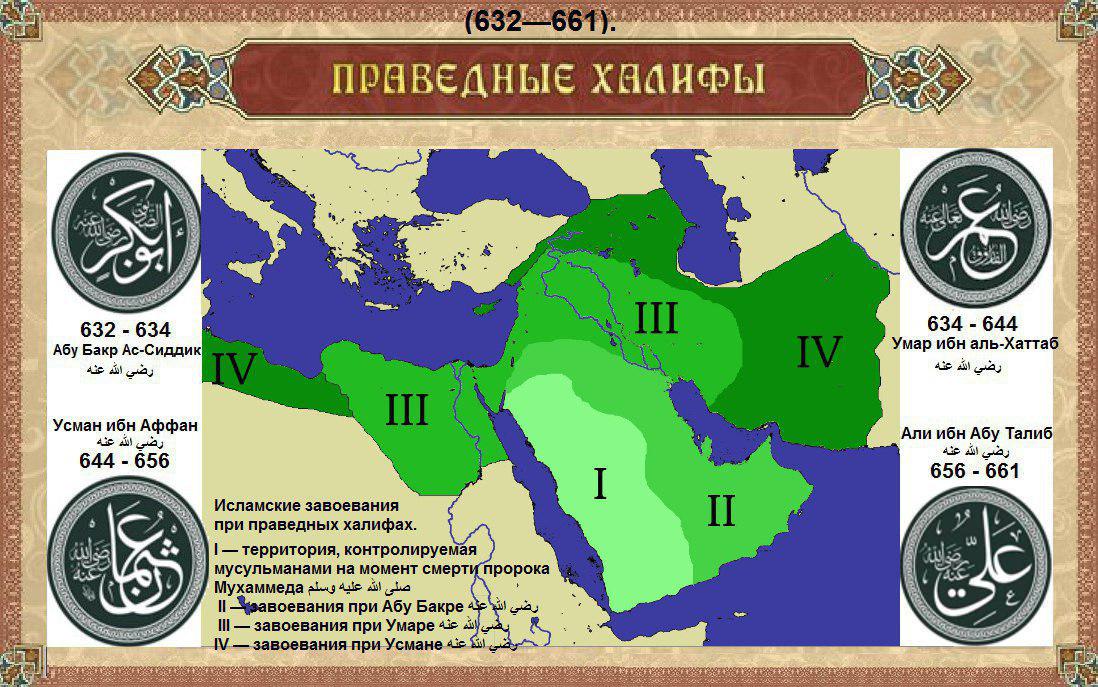

Первый религ.-политич. раскол возник в И. после смерти в 632 Пророка Мухаммеда. Спор о главе мусульм. сообщества и государства вызвал появление двух гл. направлений И. – суннизма и шиизма, и гражд. войну в Халифате. Сунниты считали, что преемника Пророка нужно избирать из его соплеменников Курейшитов, но не обязательно из рода или семейства Мухаммеда (см. Шерифы). Осн. задача халифа – следить, чтобы жизнь мусульм. сообщества Халифата соответствовала установлениям религии. Халиф не обладает высшей законодат. властью в общине и не может вводить новые догматы и обряды или отменять старые, поскольку после смерти Мухаммеда неизменным источником религ. закона служат Коран и Сунна. Правильное толкование этих гл. источников исламского вероучения обеспечивается согласным мнением общины в лице наиболее авторитетных улемов (иджма). Сунниты признают законность власти всех четырёх первых халифов, получивших в мусульм. традиции прозвание «праведных».

Сторонники ближайшего сподвижника и двоюродного брата Мухаммеда Али ибн Аби Талиба образовали шиитскую партию, предлагавшую передать руководство мусульм. уммой потомкам от брака Али с дочерью Мухаммеда Фатимой через их сыновей Хасана и Хусейна. Шииты считали, что только имамы из рода Мухаммеда, унаследовав от него божественную благодать и способность прямого общения с Аллахом, могут по праву руководить мусульманами. В ходе борьбы Али с соперниками появилось течение «восставших» (хариджитов), сочетавших политич. эгалитаризм с религ. ригоризмом. В отличие от суннитов и шиитов они признавали право занять престол халифа за любым верующим, избранным всеми мусульманами. Со временем общины хариджитов, шиитов и суннитов в свою очередь раскололись. В 8 в. от шиитского И. отделилось течение исмаилитов.

Суфийская обитель (ханака) с медресе Фирдаус в Халебе. 1235/36.

Фото В. М. Паппе

Одновременно с религ.-политич. дроблением мусульм. мира шло формирование осн. толков мусульм. права. Здесь основой расхождений стали методы извлечения правовых норм, а также толкование Корана и Сунны, которые остаются для всех течений гл. источниками И. Во 2-й пол. 8–10 вв. в суннитском И. сложился ряд религиозно-правовых школ (мазхабов), из которых ныне сохранились четыре: ханафитская, преобладающая среди мусульман России; шафиитская, приверженцы которой в России сосредоточены на Сев.-Вост. Кавказе (Дагестан, Чечня, Ингушетия); маликитская – в Магрибе и аль-Андалусе, ханбалитская – в Аравии. Все они считаются одинаково правоверными. Наиболее распространён ханафизм, официально принятый в нач. 16 в. Османской империей. В современном мире его придерживается ок. 1/3 мусульман. В Новейшее время равноправными религиозно-правовыми школами, наряду с суннитскими, были признаны джафаритский мазхаб шиитов-имамитов и школа мусульм. права шиитов-зейдитов.

Архив БРЭ

Мечеть Сулеймание и медресе при ней в Стамбуле. Архитектор Синан. 1550–57.

Потребность в рациональном осмыслении религ. догм вызвала к жизни богословие – калам, сосредоточившееся на вопросах соотношения божественных атрибутов и сущности, предопределения и свободы воли. Наибольшее распространение в суннитском И. получили созданные в 10 в. богословские системы аль-Ашари и аль-Матуриди. В результате ассимиляции античной философии, особенно аристотелизма, появился вост. перипатетизм (см. Фальсафа), крупнейшими представителями которого были аль-Фараби, Ибн Сина и Ибн Рушд. Отдельным мистич. направлением в И. стал суфизм. Возникнув при Омейядах, движение суфиев носило характер индивидуальной аскезы. Оно появилось как реакция на дифференциацию мусульм. общины, протест против роскошной жизни господствующей верхушки. В 8–10 вв. суфизм превратился в идейное течение, противопоставившее схоластике калама и казуистике фикха индивидуальный мистический опыт познания Бога. В 11–12 вв. разрозненные суфийские обители объединяются в братства (тарикаты), каждое из которых имело собственную систему мистической практики, обрядов, внешних знаков отличия. Благодаря деятельности братств суфизм к 13 в. стал осн. формой распространения И. в целом ряде регионов, гл. обр. на границах мусульм. мира. Вместе с организационным оформлением суфизма развивалась его философия, достигшая вершин в «теософии озарения» (ишракизм) ас-Сухраварди и особенно в школе «единства бытия» (вахдат аль-вуджуд) Ибн аль-Араби.

«Классический» средневековый ислам

Под этим условным названием подразумевается совокупность идейных течений И., во взаимодействии и борьбе которых к 10–14 вв. сложилась общая нормативная система религ. знания и власти, доныне остающаяся образцом подражания для мусульм. мыслителей и политиков разных ориентаций. В результате было достигнуто относительное равновесие взглядов и общественных интересов, обеспечивающее устойчивость И. как религии и социальной системы. Одной из характерных черт такого равновесия является существование множества местных интерпретаций И. при сохранении общего культурного единства мусульм. мира (дар аль-ислам).

Благодаря торгово-экономическим и культурным связям И. распространился в эту эпоху в степную зону Центр. Евразии (Дешт-и-Кипчак), некоторые районы Сев.-Зап. Китая (Синьцзян) и Индии. Через торговые пути в Индийском ок., пионерами освоения которого были арабы, с 15 в. И. проник в Юго-Вост. Азию. Позднее мусульм. колонии появились на африканском побережье Индийского ок. и в Юж. Африке. В ходе османских завоеваний возникли современные мусульм. анклавы на Балканах. Уже в Новое время, в 17–18 вв., была завершена исламизация Сев.-Зап. Кавказа, Казахской степи и некоторых пограничных областей Сибири и Сев.-Зап. Китая (Кашгария). Эти регионы вошли в ареал традиционного распространения И. В результате массовых миграций кон. 19–20 вв. мусульм. диаспоры сложились в Европе, Америке и Японии.

Значение региональных форм И. резко выросло после того, как оформилось большинство религиозно-правовых школ суннитского И. и дальнейшее нормотворчество стало возможным только в рамках одного из традиц. мазхабов. «Врата иджтихада» как самостоят. интерпретации Корана и Сунны без опоры на традиц. авторитеты той или иной школы (таклид) с 11–12 вв. в суннизме (но не в шиизме) были «закрыты».

Таклид охранял незыблемость ср.-век. институтов, но вместе с тем помогал развитию общей религиозно-культурной системы И. На протяжении последующих веков одной из центр. проблем идейных споров в И. стало «правоверие». При халифе аль-Мамуне (813–833) была предпринята попытка ввести «сверху» систему гос. вероисповедания на основе мутазилитских догматов. Испытание (михна) в «правоверии» вызвало бурный протест улемов-традиционалистов, претендовавших на роль его хранителей. На рубеже 10–11 вв. обострились отношения между суннитами-традиционалистами, с одной стороны, и шиитами-имамитами, мутазилитами и ашаритами, в свою очередь враждовавшими между собой, – с другой. Попытки халифа аль-Кадира (991–1031) узаконить положения таклида как «правоверия» также не увенчались успехом.

Идейная борьба продолжалась и в последующие века. Одной из наиболее заметных фигур в этой борьбе был Ибн Таймийя, ревностно боровшийся за возрождение «первоначального» ислама времён Пророка Мухаммеда и четырёх праведных халифов (ас-салафия) и за религ. объединение мусульман на основе «правоверия». В Новое время традиционалистские идеи пытались претворить в жизнь ваххабиты. В ходе ср.-век. богословских споров и по мере распространения И. среди народов иных культурных регионов (персов, тюрок и др.) стала отчётливее проявляться его неоднородность. «Теоретический» И. всё дальше отходил от И. «практического», «официальный» – от «простонародного». Внутр. единство И. при многообразии его историч. форм предопределило жизнеспособность исламской духовной культуры.

Новое и новейшее время

Переломным этапом в развитии И. стало Новое и Новейшее время кон. 18–20 вв. В ответ на модернизацию обществ. устройства, секуляризацию и культурные влияния из Европы началось движение за «реформу» (ислах) мусульм. общества, которое мн. исследователи по аналогии с процессами, происходившими в католицизме 16 в., называют «мусульманской реформацией». В действительности между двумя этими явлениями больше различий, чем сходства. В отличие от протестантизма, «мусульманская реформация» не привела к религ. расколу. Она лишь в незначительной степени затрагивала собственно богословские вопросы, ограничиваясь пересмотром религ. мотиваций разл. аспектов светской жизни. Наконец, на характер реформ наложило отпечаток отсутствие в И. церкви и духовенства.

К сер. 19 в. под влиянием реформ Мухаммеда Али в Египте и политики танзимата в Османской империи была ограничена юрисдикция шариата, разграничены сферы действия шариатских и светских судов. Одновременно с этим осуществлялась кодификация норм мусульм. права. В 1869–76 был составлен гражд. свод положений ханафитского права – Маджаллят аль-акхам аль-адлия. В ряде стран введены уголовные кодексы и др. правовые документы, не предусмотренные шариатом. Расширение капиталистического предпринимательства влекло за собой пересмотр шариатских положений (в частности, безусловного запрета ростовщичества), а также оживление некоторых традиц. принципов, имевших широкое распространение в период мусульм. Средневековья, напр. торгового сотрудничества (мушарака и кирад). Нередко новые по содержанию явления воспринимались как развитие мусульм. традиции: таковы, напр., коммерч. объединения в форме религ. общин (торговые дома исмаилитов ходжа и бохра, меманов).

Эти перемены привели к возникновению ряда движений, объединённых идеей отказа от таклида и восстановления иджтихада. Последний стали понимать как свободную интерпретацию совр. религиозно-правовых явлений на основе прямого обращения к Корану и Сунне в обход сложившейся традиции их толкования. Вместе с тем участились призывы к «очищению И.» от «недозволенных новшеств» (бида), возрождению изначальной мусульм. религии. В таком подходе видели универсальное средство, способное вывести из кризиса мусульм. общество, отошедшее от следования «истинному закону». Велись споры о допустимости создания в мусульм. странах исламских банков. Полемика разворачивалась, с одной стороны, вокруг шариатского запрета взимать ссудный процент (риба), а с другой – в связи с требованием шариата «омертвления капитала». В 1899 егип. муфтий Мухаммед Абдо издал фетву, разъяснявшую, что банковские вклады и взимание с них процентов не являются ростовщичеством и, следовательно, дозволены мусульманам.

Мусульм. улемы по-новому переосмыслили мн. традиционные нормы И. Под влиянием роста нац. настроений и национализма новое толкование получило положение о единстве И. Джамаль ад-Дин аль-Афгани сформулировал идею солидарности мусульман в антиколониальной борьбе, вылившуюся затем в концепцию панисламизма и получившую широкое распространение по всему мусульм. миру. Параллельно с панисламизмом, направленным на объединение всех мусульман на основе исламских ценностей, развивался мусульм. национализм, сторонники которого выступали за обособление мусульм. общин от представителей др. конфессий. Влияние национализма заметно почти во всех направлениях мусульм. обществ. мысли кон. 19 – нач. 20 вв. В этот период шло освоение мусульм. странами науч.-технических достижений Запада. Сторонники исламского обновленчества (джадидизма) высказывались за модернизацию предписаний И., тормозивших внедрение достижений Запада. Им противостояли традиционалисты, выступавшие за возрождение норм и ценностей раннего ислама.

И. всегда был связан с политикой, со 2-й трети 19 в. широко использовался в политической борьбе. Сопротивление колониальным завоеваниям нередко проходило под знаменем джихада в защиту И. Особую актуальность приобрели мессианские идеи: некоторые лидеры повстанцев, напр. в Судане 2-й пол. 19 в., объявляли себя Махди. В политическую борьбу включился ряд суфийских братств. На их основе возникли мощные исламские движения и военно-теократические политические образования, напр. гос-во Сенуситов в Сев. Африке. Антиколониальное движение под рук. Абд аль-Кадира в Алжире связано с братством Кадирийя, мусульм. повстанчество на Сев. Кавказе – с братством Накшбандийя, ученик шейхов которого Шамиль встал во главе Имамата. От И. отделились новые синкретичные религ. движения – бабиды и бахаиты в шиитском Иране, ахмадие в суннитской Индии.