Общая информация

Площадь 14,75 млн. кв. км, средняя глубина 1225 м, наибольшая глубина 5527 м в Гренландском море. Объём воды 18,07 млн. км³.

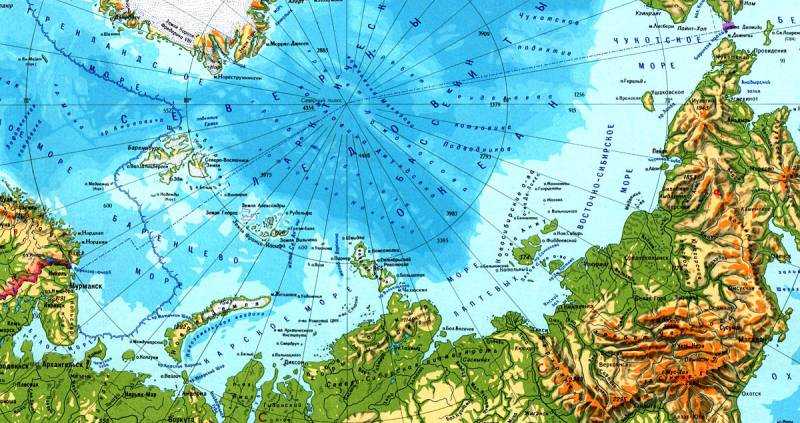

Берега на западе Евразии преимущественно высокие, фьордные, на востоке — дельтовидные и лагунные, в Канадском Арктическом архипелаге — преимущественно низкие, ровные. Берега Евразии омывают моря: Норвежское, Баренцево, Белое, Карское, Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирское и Чукотское; Северной Америки — Гренландское, Бофорта, Баффина, Гудзонов залив, заливы и проливы Канадского Арктического архипелага.

По количеству островов Северный Ледовитый океан занимает второе место после Тихого океана. Крупнейшие острова и архипелаги материкового происхождения: Канадский Арктический архипелаг, Гренландия, Шпицберген, Земля Франца-Иосифа, Новая Земля, Северная Земля, Новосибирские острова, остров Врангеля.

Северный Ледовитый океан принято делить на 3 обширные акватории: Арктический бассейн, включающий глубоководную центральную часть океана, Северо-Европейский бассейн (моря Гренландское, Норвежское, Баренцево и Белое) и моря, расположенные в пределах материковой отмели (Карское, море Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирское, Чукотское, Бофорта, Баффина), занимающие более 1/3 площади океана.

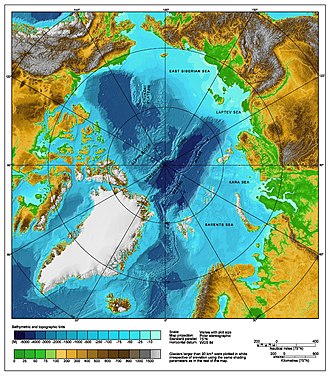

Ширина материковой отмели в Баренцевом море достигает 1300 км. За материковой отмелью дно резко понижается, образуя ступень с глубиной у подножия до 2000—2800 м, окаймляющую центральную глубоководную часть океана — Арктический бассейн, который подводными хребтами Гаккеля, Ломоносова и Менделеева делится на ряд глубоководных котловин: Нансена, Амундсена, Макарова, Канадскую, Подводников и др.

Пролив Фрама между островами Гренландия и Шпицберген Арктического бассейна соединяется с Северо-Европейским бассейном, который в Норвежском и Гренландском морях пересекается с севера на юг подводными хребтами Исландским, Мона и Книповича, составляющими вместе с хребтом Гаккеля самый северный сегмент мировой системы срединно-океанических хребтов.

Зимой 9/10 площади Северного Ледовитого океана покрыто дрейфующими льдами, преимущественно многолетними (толщина около 4,5 м), и припаем (в прибрежной зоне). Общий объём льда составляет около 26 тыс. км3. В морях Баффина и Гренландском обычны айсберги. В Арктическом бассейне дрейфуют (по 6 и более лет) так называемые ледяные острова, образующиеся из шельфовых ледников Канадского Арктического архипелага; их толщина достигает 30—35 м, вследствие чего их удобно использовать для работы многолетних дрейфующих станций.

Растительный и животный мир Северного Ледовитого океана представлен арктическими и атлантическими формами. Число видов и особей организмов убывает в направлении к полюсу. Однако во всём Северном Ледовитом океане интенсивно развивается фитопланктон, в том числе и среди льдов Арктического бассейна. Животный мир более разнообразен в Северо-Европейском бассейне, главным образом рыбы: сельдь, треска, морской окунь, пикша; в Арктическом бассейне — белый медведь, морж, тюлень, нарвал, белуха и др.

В течение 3—5 месяцев Северный Ледовитый океан используется для морских перевозок, которые осуществляются Россией по Северному морскому пути, США и Канадой по Северо-Западному проходу.

Важнейшие порты: Черчилл (Канада); Тромсё, Тронхейм (Норвегия); Архангельск, Беломорск, Диксон, Мурманск, Певек, Тикси (Россия).

Северный Ледовитый океан — самый маленький из океанов по площади. Расположен в центре Арктики и практически полностью окружён сушей. Исключение составляет лишь широкий выход в северную часть Атлантического океана и узкий Берингов пролив, соединяющий Северный Ледовитый океан с Тихим.

В его состав входит девять морей, которые вместе с заливами и проливами занимают 70 % площади океана. Многочисленность окраинных шельфовых морей — отличительная особенность Северного-Ледовитого океана. Самое большое по площади море — Норвежское, а самое маленькое — внутреннее Белое.

Общая информация о Северном Ледовитом океане

Площадь 14,75 млн. км², средняя глубина 1225 м, наибольшая глубина 5527 м в восточной части Гренландском море. Объём воды 18,07 млн. км³.

Моря, входящее в состав Северного Ледовитого океана:

- Баренцево море

- Море Баффина

- Белое море

- Море Бофорта

- Море Ванделя

- Восточно-Сибирское море

- Гренландское море

- Море Густава-Адольфа

- Карское море

- Бассейн Кейна

- Море Лаптевых

- Море Линкольна

- Норвежское море

- Печорское море

- Чукотское море

Моря Северного Ледовитого океана лежат в основном на территории шельфа, поэтому в основном не отличаются значительными глубинами. Все моря этого океана (кроме Белого моря) являются окраинными.

Самый большой залив — Гудзонов.

Самый большой остров — Гренландия (самый крупный остров земного шара. Его площадь насчитывает около 2 млн. км2).

Точный возраст океана ученым не известен. Исследования показали, что еще 55 млн лет назад океана в этом районе не было, а было большое пресноводное озеро. Температура воды в этом озере была примерна похожа не температуру, которая сегодня в субтропических морях.

Что находится на берегу Северного Ледовитого океана?

Берега на западе Евразии преимущественно высокие, фьордные, на востоке — дельтовидные и лагунные, в Канадском Арктическом архипелаге — преимущественно низкие, ровные.

По количеству островов Северный Ледовитый океан занимает второе место после Тихого океана. Все острова Северного Ледовитого океана – материкового происхождения и расположены на материковой отмели. Крупнейшие острова и архипелаги материкового происхождения:

- Канадский Арктический архипелаг,

- Гренландия,

- Шпицберген,

- Земля Франца-Иосифа,

- Новая Земля,

- Северная Земля,

- Новосибирские острова,

- остров Врангеля.

На границе с Атлантическим океаном расположен остров Исландия.

Северный Ледовитый океан не лежит в зоне активной вулканической деятельности, поэтому островов вулканического происхождения здесь нет.

Северный Ледовитый океан принято делить на 3 обширные акватории:

- Арктический бассейн, включающий глубоководную центральную часть океана,

- Северо-Европейский бассейн (моря Гренландское, Норвежское, Баренцево и Белое),

- моря, расположенные в пределах материковой отмели (Карское, море Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирское, Чукотское, Бофорта, Баффина), занимающие более 1/3 площади океана.

Какие заливы входят в Северный Ледовитый океан?

Залив Бутия, залив Холла, залив Мелвилл, залив Фокс. Пролив Барроу, пролив Вайкаунт-Мелвилл, Гудзонов пролив, Гыданский пролив, пролив Ланкастер, пролив Лонга, пролив Малыгина, пролив Нэрса, пролив Парри, пролив Кеннеди, пролив Робесона, пролив Смита, пролив Хинлопена, пролив Радзеевского, пролив Стерлегова и пролив Этерикан.

Кто живёт в северо Ледовитом океане?

Самые крупные обитатели Северного Ледовитого океана – огромные киты. В северные воды заходят нагулять жир синие, серые, горбатые и японские киты, финвалы, нарвалы, кашалоты.

Органический мир

Суровый климат и географическое положение оказали большое влияние на органический мир Северного Ледовитого океана. Pимой здесь полярная ночь (солнца нет), а летом — полярный день (солнце не садиться). Если сравнивать органический мир Арктического океана с любым другим океанам, то мы вынуждены констатировать скудность этого мира. Основная часть всех организмов здешних вод приходится на водоросли.

Климат

Северный Ледовитый океан расположен в двух климатических поясах:

Арктический. Океан практически полностью покрыт дрейфующими льдами. Эта часть практически непригодна для жизни организмов.

Субарктический. Здесь уже сравнительное разнообразие. Много видов рыбы: морской окунь, палтус, треска, сельдь и другие. Здесь проживают моржи, тюлени, белые медведи. На берегах очень много птиц.

Климат в акватории океана оценивается как арктический. Здесь долгая полярная зима, которая длится 9 месяцев. В зимние месяцы (с ноября по апрель) температура опускается до -38°C, а летом (с июня по сентябрь) поднимается всего до +9°C. Осень и весна короткие, почти не отличаются температурным колебанием и определяются только по смене дующих ветров.

В мае, когда температура воздуха поднимается до 0°C, над океаном и береговой линией скапливаются плотные слои тумана. Осадки выпадают в виде редкого дождя или мокрого снега. Их количество невелико: от 75 до 200 мм в год.

В холодные зимние месяцы над океаном стоит ясная холодная погода с высокой облачностью.

Рельеф дна океана

Океан имеет рельеф, не типичный для мирового дна. Его особенности связаны с развитием шельфа и изрезанных окраин материков. Шельф занимает более половины океанского дна, а его средняя глубина не превышает 200 м.

Исследователи выделяют глубокую центральную котловину, которая окружена морями.

Эта котловина имеет вытянутую форму, и через нее проходит подводный хребет Ломоносова, который начинается у Берегов Канады и заканчивается возле островов Анжу.

Полезные ископаемые

Берега океана богаты на рудные месторождения:

- на Таймыре добывают ильменит;

- олово на Чаунской губе;

- на Кольском полуострове — апатит, флогопит и железную руду;

- на Чукотке — золото;

- свинец и цинк на Аляске;

- на Баффиновой земле — серебро.

В Гренландии 10 лет назад обнаружены большие запасы урана, но разработка месторождения пока не началась. На мелководных шельфах северной Аляски и в подводной цепи хребта Ломоносова открыты нефтяные месторождения. Претендовать на их разработку могут Россия, США, Дания и Норвегия.

Суровые погодные условия затрудняют добычу полезных ископаемых, и, пока не созданы технологии работы за полярным кругом, эти залежи составляют мировой неразрабатываемый запас.

Хозяйственное использование

Северный Ледовитый океан, как и все остальные, имеет большое значение в хозяйственной деятельности человека. Океан имеет наибольшее значение для России, Канады и стран Северной Европы, которые находятся в его акватории.

В акватории океана ведётся добыча полезных ископаемых, он имеет большое промысловое и транспортное значение. Разведку и освоение месторождений полезных ископаемых в океане затрудняют суровые природные условия. Но некоторые обнаруженные месторождения нефти и природного газа уже начинают разрабатываться, так как экономический и технический уровень прибрежных стран позволяет осваивать эти месторождения.

В нашей стране важную роль играют работы по освоению Северного морского пути, который позволяет осуществлять доставку грузов в отдалённые районы Сибири и Дальнего Востока. Для прохода судов в таких суровых условиях используются ледоколы, как дизельные, так и атомные.

Северный морской путь по сравнению с проходом через Индийский океан занимает существенно меньше времени. В связи с постепенным изменением климата планеты и уменьшением общей площади арктических льдов, судоходный период на Северном морском пути увеличивается (сейчас с июня по ноябрь), что делает его всё более востребованным.

СЕ́ВЕРНЫЙ ЛЕДОВИ́ТЫЙ ОКЕА́Н (на рус. картах с 17 в. встречаются названия: Ледовитое м., Северный ок., Северное, или Ледовитое, м., Ледовитый ок.), часть Мирового ок., наименьший и самый мелкий из океанов Земли, расположенный в сев. полярной области. Занимает приполюсное пространство между Евразией и Сев. Америкой. Характеризуется частичным покрытием поверхности морским льдом в течение всего года. Впервые выделен как самостоят. океан в 1650 нидерл. картографом Б. Варениусом под назв. Гиперборейского ок., в 1845 Лондонским географич. об-вом назван С. Л. о.; в СССР это название официально принято в 1935.

Физико-географический очерк

Общие сведения

С. Л. о. хорошо изолирован от др. районов Мирового ок., сообщается с Тихим ок. через узкий и мелководный Берингов прол., граница проходит по параллели мыса Уникын (Чукотский п-ов) до пересечения с берегом п-ова Сьюард (Аляска); с Атлантическим ок. – через проливы Девисов, Датский, Фарерско-Исландский, Фарерско-Шетландский, граница – по вост. входу в Гудзонов прол., по параллели 70° с. ш. и далее по юж. окраинам Гренландского и Норвежского морей. Пл. 14,75 млн. км2, объём 18,07 млн. км3 (ок. 4% площади Мирового ок., 1,35% его объёма), ср. глубина 1225 м, наибольшая – 5527 м (в сев.-вост. части Гренландского м.). Мелководная шельфовая зона океана (глубины до 200 м) занимает 39,6% его площади (ср. значение для Мирового ок. 7,3%).

Моря

По физико-географич. особенностям и гидрологич. режиму в пределах С. Л. о. выделяют: Северо-Европейский бассейн (С.-Е. б.) – моря Гренландское, Норвежское, Баренцево и Белое; Арктический бассейн (А. б.) – глубоководная центр. часть С. Л. о. и моря азиат. и амер. материковой отмели – Карское, Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирское, Чукотское, Бофорта, Баффина, Линкольна, Гудзонов зал. А. б. делится подводным Ломоносова хребтом на суббассейны: Евразийский (Е. с.) и Амеразийский (А. с.). Некоторые географы выделяют как отд. часть – Канадский Арктический бассейн (моря Канадского Арктического архипелага – Баффина м., Линкольна м. и Гудзонов зал.), а моря Норвежское и Гренландское иногда выделяют как Норвежско-Гренландский бассейн (Н.-Г. б.), некоторые зарубежные географы не включают в границы С. Л. о. Норвежское море. Моря, заливы и проливы занимают б. ч. площади С. Л. о. – почти 70% (10,28 млн. км2); на моря, омывающие берега России, приходится св. 50% их площади.

Острова

Остров Элсмир (Канада).

Фото Michael Studinger/NASA

По количеству островов С. Л. о., по некоторым оценкам, занимает 2-е место после Тихого ок. Общая площадь островов ок. 4 млн. км2. Насчитывается ок. 250 островов с площадью более 100 км2. Они расположены преим. на материковой отмели и имеют материковое происхождение. Крупнейшие – Гренландия (самый большой в Мировом ок.), Исландия (на границе с Атлантическим ок.), Врангеля остров; среди архипелагов – Канадский Арктический архипелаг, Новая Земля, Шпицберген, Новосибирские острова, Северная Земля, Франца-Иосифа Земля и др. Большинство арктич. островов и архипелагов покрыты ледниками. В условиях совр. потепления климата отмечается сокращение площади арктич. ледников, являющихся источниками айсбергов.

Берега

Побережье острова Шпицберген.

Фото Wenche Nag

В Скандинавии, Исландии и Гренландии преим. высокие, фьордовые берега; у Белого, Баренцева и Карского морей – абразионные, изрезанные заливами, частично низкие, ровные, местами дельтовые. В районе морей Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирского, Чукотского и Бофорта берега на отд. участках дельтовые, местами лагунные, в Канадском Арктическом архипелаге – преим. низкие, ровные. Осн. причинами изменений береговой линии являются морозное выветривание, мор. абразия, термоабразия (скорости разрушения термоабразионных берегов в м. Лаптевых достигают в год 12 м). Влияние плавучих мор. льдов на формирование береговой линии оценивается как слабое.

Рельеф дна

С. Л. о. отличается от др. океанов меньшими глубинами и сильно развитым шельфом, занимающим половину его площади. Внешняя граница шельфа расположена в ср. на глубинах ок. 200 м (иногда до 500 м и более). Ширина арктич. шельфа от 500 до 1200 км; в С.-Е. б. шельфы относительно узкие – от 50 до 300 км.

Гл. структурным элементом рельефа дна в А. с. является обширная Канадская котловина с достаточно ровным дном с глубинами до 3900 м, окружённая поднятиями Бофорта, Чукотским и хребтами Альфа и Менделеева, соединяющаяся с мелководным сибирским шельфом; между хребтами Альфа, Менделеева и Ломоносова, пересекающим С. Л. о. через приполюсный район (миним. глубины менее 1000 м), расположены котловины Макарова (макс. глубина 4030 м) и Подводников; с др. стороны хребта Ломоносова в Е. с. расположены 2 продолговатые котловины (Амундсена – макс. глубина 4485 м и Нансена – 3975 м), разделённые хребтом Гаккеля, простирающиеся от прол. Фрама (между о. Гренландия и архипелагом Шпицберген) и берегов Гренландии в генеральном направлении с запада на восток; в С.-Е. б., отделённом на юге от Атлантического ок. цепочкой подводных порогов, выделяются 2 зоны – сравнительно мелководное Баренцево м. и глубоководные моря Гренландское (макс. глубина 5527 м) и Норвежское, разделённые цепью хребтов – Исландским, Мона и Книповича, последний смыкается на севере с хребтом Гаккеля; в Норвежском м. доминируют 2 котловины – Норвежская (макс. глубина 3970 м) и Лофотенская (3717 м). Глубина С. Л. о. в районе Сев. полюса составляет 4225 м, по данным Воздушной высокоширотной экспедиции Арктич. и Антарктич. НИИ 1970-х гг. [по др. данным, 4261 м – по измерениям глубоководного аппарата «Мир» в 2007 или 4087 м – по измерениям амер. ПЛ «Наутилус» («Nautilus») в 1958]. В целом более глубокими являются моря С.-Е. б., шельфовые моря частично захватывают океанский склон на севере, где их глубоководные районы имеют вид желобов.

Геологическое строение

По геологическому (тектоническому) строению и истории геологич. развития впадина С. Л. о. разделяется на Арктический и Норвежско-Гренландский океанич. бассейны (А. б. и Н.-Г. б.) и область материковых окраин. В А. б. хребет Ломоносова разграничивает Е. с. и А. с. С. Л. о. представляет собой ансамбль тектонич. структур, определяемых взаимным расположением древних литосферных плит: Северо-Американской (Лаврентии), Восточно-Европейской (Балтии) и Сибирской. Продолжением срединно-океанических хребтов Атлантического ок. в С. Л. о. является система спрединговых (см. Спрединг) хребтов Кольбейнсей, Mона, Книповича и Гаккеля (общая длина ок. 4500 км). Хребет Гаккеля переходит в систему рифтов на шельфе м. Лаптевых (сопровождающий пояс землетрясений протягивается до дельты p. Лена и далее в глубь Евразии, маркируя границу литосферных плит). По обе стороны от хребтов Кольбейнсей, Mона, Книповича располагаются глубоководные котловины Н.-Г. б.; хребет Гаккеля разделяет котловины Амундсена и Нансена в Е. с. Бо́льшую часть А. с. занимает обширная Канадская котловина. В А. б. выделяется трансокеанич. система поднятий: хребет Aльфа – Менделеева хребет (поднятие) и Ломоносова хребет. В А. с. между хребтом Ломоносова и системой хребтов Альфа – Менделеева располагаются котловины Макарова и Подводников. Для С. Л. о. характерны окраинно-шельфовые плато: Воринг в H.-Г. б., Ермак и Моррис-Джесуп в Е. с., Чукотское и Нортвинд (Нортуинд) в А. с.

По типу земной коры выделяют океанические, субокеанические и континентальные структуры. В Н.-Г. б. и Е. с. океанич. тип земной коры характерен для спрединговых хребтов и расположенных по обе стороны от них глубоководных котловин. Симметрично рифтовым долинам хребтов Кольбейнсей, Мона и Гаккеля установлены линейные магнитные аномалии (по 24 включительно); в секторе Н.-Г. б. с хребтом Книповича чёткие линейные аномалии отсутствуют. В А. с. по типу земной коры к океанич. структурам относятся котловины Канадская и Макарова; котловина Подводников подстилается субокеанич. корой (или континентальной корой сокращённой мощности). Континентальный тип земной коры имеет трансокеанич. система поднятий А. б. (хребет Ломоносова и хребты Aльфа и Менделеева), а также все окраинно-шельфовые плато С. Л. о. (Воринг, Ермак, Моррис-Джесуп, Чукотское, Нортвинд).

Наиболее древняя из глубоководных котловин С. Л. о. – Канадская, начало её образования относят к поздней юре. Котловины Макарова и Подводников образовались в раннем мелу; котловины Амундсена и Нансена и Н.-Г. б. – на рубеже мела и палеогена. Формирование океанич. структур сопровождалось мощными излияниями базальтов в районе вост. побережья Гренландии, на плато Bоринг и в пределах системы хребтов Альфа – Менделеева.

B области материковых окраин С. Л. о. развита земная кора континентального типа макс. мощностью до 40 км. B отд. частях Баренцево-Карского шельфа земная кора утонена, гранитометаморфич. слой отсутствует, резко увеличивается мощность осадочного чехла. Шельф морей Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирского и Чукотского подстилается континентальной корой сокращённой мощности. На шельфе выделяются блоки с разл. строением континентальной земной коры – платформенные области и складчатые зоны. Плиты древних платформ (Восточно-Европейской, Гиперборейской) образуют фрагменты Баренцево-Карского шельфа; в юж. часть этого шельфа продолжаются эпибайкальская Баренцево-Тиманская и эпипалеозойская Западно-Сибирская плиты. Эпимезозойская плита является основанием прогибов Лаптево-Чукотского шельфа. Местами шельфы С. Л. о. пересекаются складчатыми стуктурами байкальского, каледонского, герцинского и мезозойского возрастов, выступающими на побережьях и в архипелагах островов (см. в ст. Арктика). Желоба и троги Баренцево-Карского шельфа (Медвежинский, Стурфьордренна, Франц-Bиктория, Святая Анна, Воронина) отвечают молодым грабенам. На шельфе морей Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирского и Чукотского широко развиты ориентированные в сев.-зап. и меридиональном направлениях рифтогенные прогибы.

По особенностям строения и развития в четвертичном периоде в евразийской части арктич. шельфа выделяются 2 сектора – западный и восточный (граница секторов проходит к востоку от архипелага Северная Земля, по жёлобу Старокадомского). Более глубоководный зап. сектор (Баренцево и Карское моря) с контрастным рельефом отличался активной неотектоникой; он подвергался активному воздействию плейстоценовых ледниковых покровов (установлены затопленные краевые морены оледенений). В пределах мелководного вост. сектора (моря Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирское и Чукотское) с выровненным рельефом новейшие тектонич. движения проявились мало; следы ледникового воздействия отсутствуют. В обоих секторах в позднеплейстоценовое время происходило промерзание прибрежных, осушенных при понижении уровня моря участков шельфа, что сопровождалось формированием подземных льдов. В процессе последующего затопления шельфа наблюдалось частичное таяние подземных льдов (их фрагменты вскрыты буровыми скважинами в морях Баренцевом, Карском, Лаптевых; предполагаются в зап. части Восточно-Сибирского моря).

Донные осадки

Донные осадки С. Л. о. имеют преим. терригенное происхождение. На мелководьях шельфа развиты гл. обр. галечные и песчаные алевритовые илы. В открытой части шельфа более распространены алевритово-глинистые илы. B глубоководных океанич. бассейнах хребты и относительные поднятия покрыты песчанистыми илами (мощность 400–600 м), в котловинах залегают глинистые илы (мощность 1500–2500 м). У континентальных подножий широко представлены турбидиты (мощность 1500 м). Существенную роль в осадконакоплении в С. Л. о. играет разнос песчаного и крупнообломочного материала дрейфующими льдами и айсбергами.

Климат

Северный Ледовитый океан летом.

Фото Д. В. Соловьёва

Характерные особенности климата определяются высокоширотным положением С. Л. о., обусловливающим преобладание радиационного выхолаживания над поступлением тепла (см. Арктика, Арктический климат). Важную роль в формировании климата С. Л. о. играют также тёплые Северо-Атлантическое течение и Тихоокеанское течение; привнос ими тепла в С. Л. о. составляет 60% от переноса тепла в атмосфере (по данным М. И. Будыко). В зимние месяцы (январь – апрель) над А. б. располагается Арктический антициклон. Циклоны из Атлантики перемещаются на север через моря Баффина и Гренландское и на восток через моря Норвежское, Баренцево и Карское; нередко проникают в приполюсный район. Летом устойчивые, но менее мощные, чем зимой, антициклоны наблюдаются в А. б. к северу от Аляски и Чукотского м. и над Гренландией. Циклонич. деятельность развивается гл. обр. над севером Канады и Сибири, распространяясь на прилежащие районы С. Л. о. Над С.-Е. б. в течение всего года господствует ложбина Исландского минимума, а над Гренландией – максимум атмосферного давления. Поэтому над зап. частью С.-Е. б. преобладают ветры сев. и сев.-зап. направлений, обусловливая суровый арктич. климат, а в вост. части отмечаются преим. юж. и юго-зап. ветры, вследствие этого, а также под влиянием тёплого Норвежского течения климат здесь более мягкий. Через С.-Е. б. проходит большое количество глубоких циклонов, вызывающих резкие перемены погоды, обильные осадки и туманы. Осенью и в особенности зимой сильное волнение, большая влажность и низкие темп-ры воздуха часто приводят к сильному обледенению судов, создавая опасность для мореплавания. Ветровой режим неустойчив (ср. скорость ветра 4–6 м/с), сильные ветры (более 15 м/с) бывают редко. В прибрежных районах заметно выражен сезонный (муссонный) ход направления ветра, его скорость и число дней со штормами здесь значительно возрастают, особенно зимой. Ср. темп-ра воздуха зимой в разл. районах С. Л. о. колеблется от –2 до –40 °C (в районе Сев. полюса), летом от 0 до 6 °C. Повторяемость облачности достигает 90% летом и 50% зимой. Атмосферные осадки выпадают в виде снега; дожди, чаще всего со снегом, бывают редко. Количество осадков в А. б. не превышает 150, в С.-Е. б. – 250–300 мм в год. Толщина снежного покрова невелика, её распределение крайне неравномерно. Летом снежный покров почти повсеместно стаивает.

По оценкам одних исследователей, совр. изменения климата заключаются в повышении темп-ры воздуха, сопровождаются отступанием ледников, уменьшением толщины и площади дрейфующих льдов (особенно летом). Отмечена связь этих явлений с изменениями характера атмосферной циркуляции и солнечной активности. Прогностич. оценки, полученные на основе моделирования, показывают устойчивые тенденции в уменьшении ледовитости и возможное исчезновение ледяного покрова С. Л. о. летом уже к сер. 21 в. По мнению другой группы учёных, изменения климата носят полициклич. характер, поэтому возможно изменение тенденции и восстановление ледяного покрова до среднемноголетних значений.

Гидрологический режим

Осн. особенности циркуляции вод, льдов и гидрологич. режима С. Л. о. определяют: рельеф дна и конфигурация берегов, распределение островов и гл. архипелагов, высокая степень изолированности С. Л. о. от др. районов Мирового ок., водообмен с Тихим и Атлантическим океанами, изменения в структуре атмосферной циркуляции, материковый сток.

Ледниковый покров на Карском море.

Фото Д. В. Соловьёва

Шельфовые моря б. ч. подвержены сильному влиянию материкового пресноводного стока, создающего положительный пресноводный баланс. Крупнейшие реки, впадающие в них: Сев. Двина, Обь, Енисей, Хатанга, Лена, Колыма, Маккензи и др., приносят ежегодно ок. 5000 км3 пресной воды. С. Л. о. по объёму пресноводного стока рек занимает 1-е место среди океанов; условная (распределённая по всей площади) толщина слоя пресных вод составляет 35 см/год, что в 3 раза превышает этот показатель для Мирового ок. По объёму поступающих пресных вод Карское м. занимает 1-е место в мире (слой 150 см/год), м. Лаптевых – 2-е место (120). А. б. является источником распреснённых вод по отношению к С.-Е. б., а С. Л. о. в целом по отношению к Сев. Атлантике. Сильно охлаждённые (с темп-рой ниже –1 °C) и распреснённые (солёность менее 32‰) воды вследствие меньшей плотности не опускаются на глубину, а вытекают из С. Л. о. в виде холодных поверхностных течений (Восточно-Гренландское течение и Лабрадорское течение) в Атлантику. Общий сток этих течений ок. 250 тыс. км3 в год. Восстановление балансов осуществляется потоками водо- и солеобменов через проливы. Осн. приток тёплой (до 10 °C) и солёной воды (34,9–35,2‰) в С. Л. о., затем в А. б. происходит через юж. проливы из Атлантического ок. ветвями Северо-Атлантического течения – Норвежским течением (135 тыс. км3) и Ирмингера течением, а также частично через Берингов прол. из Тихого ок. водами Тихоокеанского течения, которое приносит в С. Л. о. ок. 30 тыс. км3 в год.

Температурный режим

В поверхностном слое подо льдом в А. б. и морях сибирского шельфа темп-ра воды в осн. соответствует темп-ре замерзания при данной солёности и зависит от степени распреснённости воды в том или ином районе, она изменяется от –1,0 до –1,9 °С, причём более тёплая вода в Карском м. и м. Лаптевых и более холодная – в м. Бофорта и центр. районах А. б. Летом свободные ото льда районы подвергаются радиац. прогреву и темп-ра воды возрастает; так, в прибрежных районах морей сибирского шельфа она может достигать 5 °С.

В С.-Е. б. в поверхностном слое пространственное распределение темп-ры воды определяется зональным радиац. прогревом, распределением потоков вод из сопредельных районов и ледниковым стоком. Зимой диапазон изменения темп-ры воды составляет от 0 до 5–6 °С, летом от 0 до 12–13 °С, причём более тёплые воды отмечаются у побережья Скандинавии и на границе с Атлантическим ок., а более холодные – у берегов Гренландии.

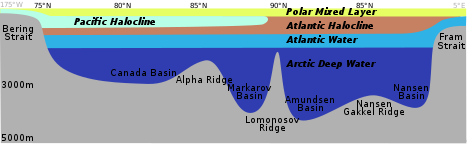

Изменение темп-ры воды по глубине согласуется со структурой водных масс в конкретном районе, самым ярким свойством в её распределении является наличие прослойки тёплых атлантич. вод практически по всей глубоководной части А. б. и относительно тёплой прослойки вод тихоокеанского происхождения в А. с., а также устойчивая разность в темп-ре придонных вод в А. с. и Е. с. (ок. –0,4 °С и –0,8 °С соответственно). Одной из характерных особенностей гидрологич. режима С.-Е. б. является существование купола холодных промежуточных и донных вод в его центр. районе.

Солёность

В поверхностном слое С. Л. о. миним. значения солёности отмечаются в приустьевых областях морей Карского, Лаптевых и Восточно-Сибирского и составляют менее 20‰, здесь наблюдаются хорошо выраженные фронтальные зоны со значит. горизонтальными градиентами. В центр. районах А. б. миним. измеренные значения солёности 30‰, постепенно они повышаются до нормальной океанской солёности (35‰) в С.-Е. б.

Плотность

Пространственное распределение плотности воды в А. б. определяется преим. распределением её солёности, а в С.-Е. б. – темп-ры. Характерной особенностью вертикального распределения плотности воды в А. б. является ярко выраженная стратификация вод в верхнем 250-метровом слое. Выделяют два типа стратификации – с одним и двумя максимумами в вертикальном распределении плотности воды. Первый тип существует на всей площади А. б., он формируется на нижней границе достаточно тонкого (25–50 м) поверхностного перемешанного по вертикали квазиоднородного слоя вод, второй – наблюдается преим. в районе Канадской котловины в А. с. и расположен на глубинах ок. 200 м на вертикальных разделах, между водными массами разл. происхождения. Наличие таких слоёв скачка плотности затрудняет вертикальное перемешивание вод и препятствует, в частности, вертикальному распространению тепла глубинных атлантич. вод в вышележащие слои и к поверхности. Это явление уменьшает влияние тепла атлантич. вод на таяние ледяного покрова океана. В С.-Е. б. доминирующим является слой скачка плотности на нижней границе сезонного пикноклина. Величина плотности воды в поверхностных слоях С.-Е. б. выше, чем в А. б., и составляет зимой 1028,00 и 1024,00 кг/м3 соответственно, а в приустьевых районах Карского м. снижается до 1016,00 кг/м3 (летом 1027,50, 1022,00 и 1010,00 кг/м3 соответственно), в придонном слое повсеместно и круглый год значения плотности приближаются к 1028,10 кг/м3. В районах арктич. островов в период ледообразования в результате выделения из воды солей могут образовываться воды очень высокой солёности и плотности, являющиеся источником, подпитывающим донные воды.

Ледовый режим

Почти все моря С. Л. о. (кроме Норвежского) имеют сезонный ледяной покров, а некоторые части морей бывают покрыты льдом в течение всего года. Среднемноголетняя пл. морского льда в конце зимы (март – апрель) может составлять до 11,4 млн. км2, а в конце летнего гидрологич. сезона, в сентябре, – ок. 7 млн. км2. В течение последних двух десятилетий площадь, занимаемая льдами, уменьшается (преим. в летний сезон), в 2007 и в 2012, который считают рекордным, площадь, занятая льдом в сентябре, была менее 4 млн. км2.

Районы С. Л. о., освобождающиеся летом ото льда, зимой покрыты в осн. однолетними льдами, достигающими на ровных участках толщины 2 м. В прибрежных районах некоторых арктич. морей образуется припай (прикреплённый к берегу неподвижный лёд). Он может простираться на расстояние от нескольких метров до нескольких сотен километров от берега. Остальная часть С. Л. о. (в осн. А. б.) покрыта дрейфующими многолетними льдами, толщина которых на ровных участках может достигать 4,5 м. Размеры отд. льдин изменяются в поперечнике от 2 м до 10 км. В результате неравномерного дрейфа льда в ледяном покрове возникают зоны сжатий, образуются разломы и торосы. В зонах торошения толщина ледяного покрова может быть значительно выше, чем ровного льда. Высота надводной части торосов колеблется от 2 до 3,5 м, достигая на кромке припая 12 м. Общий объём льда в С. Л. о. в зимнее время составляет до 28 тыс. км3, а в конце лета – 16 тыс. км3. В ряде районов С. Л. о. встречаются айсберги, которые существенно меньше антарктических, особенно много их в м. Баффина. В А. б. дрейфуют т. н. ледяные острова, образующиеся из шельфовых ледников Канадского Арктического архипелага; их толщина достигает 30–35 м, на ледяных островах организовывались науч. дрейфующие станции «Северный полюс» (см. Полярные станции). Наличие льдов существенно затрудняет мореплавание по Северному морскому пути и Северо-Западному проходу.

Течения

Циркуляция поверхностных вод и льдов в С. Л. о. определяется в осн. ветром, оказывающим также существенное влияние и на водообмен С. Л. о. с Тихим и Атлантическим океанами. Гл. элементами крупномасштабной структуры поверхностной циркуляции вод являются в А. б. антициклональный круговорот над Канадской котловиной со ср. скоростями 2–5 см/с и Трансарктическое течение, пересекающее А. б. в направлении от Чукотского м. до прол. Фрама, а в С.-Е. б. – циркуляция циклонич. характера со скоростями 10–20 см/с, структурными элементами этой крупномасштабной циркуляции являются холодное Восточно-Гренландское течение, идущее на юг вдоль вост. побережья Гренландии, и тёплое Норвежское течение с его ответвлениями.

Пространственная неоднородность и высокая гидростатич. изолированность промежуточных (преим. тихоокеанских) вод в А. б. обусловливают существование подповерхностных мезомасштабных неоднородностей в поле течений, имеющих, как предполагается, вихревую структуру, что является наиболее яркой особенностью динамики вод А. б. Скорости течений в этих вихревых образованиях могут превышать 60 см/с.

Водные массы

Осн. водными массами С. Л. о. являются поверхностные, промежуточные, глубинные и донные. В А. б. 95% объёма занимают малоизменённые промежуточные водные массы (в т. ч. тихоокеанские, имеющие разл. характеристики летом и зимой), тёплые глубинные – из Атлантического ок. и донные – из Норвежского м. В С.-Е. б. св. 80% объёма составляют воды местного образования: холодные промежуточные и донные (самые холодные, до –1,3 °C, и самые плотные среди донных вод Мирового ок.), тёплые атлантич. воды Норвежского течения и его ветвей занимают не более 8% объёма. В морях Карском, Лаптевых и Восточно-Сибирском постоянно присутствуют сильно распреснённые воды речного происхождения, которые, смешиваясь с морскими, образуют поверхностные воды арктич. морей. Ареал речных вод в Карском м. может занимать до 1/3 его площади. На границе ареала формируется фронтальная зона, характеризующаяся существенными горизонтальными градиентами термохалинных характеристик.

Приливы и волнение

Приливные колебания уровня вод и приливо-отливные течения в С. Л. о. преим. правильные полусуточные. Величина прилива в А. б. 0,5–0,6 м; в С.-Е. б. в среднем ок. 1 м, по районам сильно различается: наибольшая величина прилива у берегов Гренландии и Шпицбергена 1,5 м, Скандинавии ок. 3 м, в узких проливах вдоль юж. берега Баренцева м. до 5 м; макс. приливные колебания уровня наблюдаются: в Иокангской губе Баренцева м. до 6 м, в прол. Горло Белого м. до 7 м, в его Мезенской губе до 10 м. Приливы у берегов Сев. Америки 0,2–0,4 м, между Гренландией и о. Элсмир 2–4 м, в Канадском Арктическом бассейне, в м. Баффина 2–7 м. Приливные течения выражены в районах значит. колебаний уровня и могут достигать 2 м/с (прол. Горло Белого м.).

Наряду с приливами, в мелководных арктич. морях отмечаются ветровые сгонно-нагонные колебания уровня воды, в некоторых районах, особенно вдоль материкового побережья, они превышают приливные, составляя 1–2 м.

Волнение в С. Л. о. зависит не только от ветрового режима, но и от ледовых условий: чем больше акватория освобождается ото льда, тем лучшие условия создаются для развития волнения, напр., в С.-Е. б. В арктич. морях в зимнее время волнение практически отсутствует, а значительного развития оно достигает в летний и особенно в осенний период, когда наблюдается наибольшее очищение ото льда, а атмосферные процессы характеризуются интенсивной циклонич. деятельностью, сопровождающейся сильными ветрами. Кроме ветровых волн, наблюдаются и волны зыби, которые, трансформируясь у берегов, формируют мощный накат. Опасность ветрового волнения при наличии льдов вызывает возвратно-поступательное движение льдин и в прибрежной зоне может приводить к разрушению берегов и инж. сооружений – причалов и пр. При совр. уменьшении площади мор. льдов и увеличении площади акваторий с разреженными льдами волнение может представлять существенную опасность при операциях на шельфе и навигации. В арктич. морях высота ветровых волн может достигать 7–8 м, а длина – 120–160 м. Повторяемость волн выше 3 м сравнительно невысока и составляет до 10%. Наибольших значений ветровые волны достигают в незамерзающих районах С.-Е. б., повторяемость волн высотой 5–10 м осенью и зимой составляет 15–20%, летом интенсивность волнения заметно уменьшается.

Флора и фауна

Флора и фауна С. Л. о. по богатству и разнообразию резко различается в тёплых и холодных водах, состоит из более чем 3000 видов, включающих практически все известные виды, населяющие воды Мирового ок., качественное разнообразие жизни снижается с запада на восток от Баренцева м. к Чукотскому м., а в целом плотность биомассы от Атлантики к полюсу уменьшается в 5–10 раз. Донные водоросли, в т. ч. имеющие промысловое значение (ламинариевые, фукусы и др.), в больших количествах распространены в районах влияния тёплых вод у берегов Исландии, Норвегии, Кольского п-ова и в Белом море. В холодных водах А. б. флора значительно беднее, т. к. льды препятствуют развитию жизни в литорали. Однако во всём С. Л. о. интенсивно развивается фитопланктон (в осн. диатомовые), в т. ч. и среди льдов центр. части Арктики. Животный мир более разнообразен в С.-Е. б., где представлено св. 2000 видов животных, включая китов (полосатик и ныне почти истреблённый гренландский), и большое число видов рыб – сельдь, треска, морской окунь, пикша и др. В А. б. среди млекопитающих преобладают криофилы – белый медведь, морж, тюлень, а также нарвал, белуха и др. Видовой состав рыб включает ок. 150 видов морских и пресноводных (преобладают полярная треска, навага, сайка и в устьях рек – лососёвые и сиговые). Эндемизм С. Л. о. относительно невелик, обусловлен своеобразием его характеристик и представлен 36 родами (3% всей фауны и флоры) и 540 видами (18%).

Хозяйственное использование

Транспорт

Транспортное значение С. Л. о. постоянно увеличивается. Перевозки осуществляются в осн. Россией по Северному морскому пути, США и Канадой по Северо-Западному проходу. Судоходные линии на Гренландию, Исландию, север Скандинавии и Шпицберген, как правило, в летний период не зависят от ледовых условий. Важнейшие порты РФ – незамерзающий порт Мурманск (Баренцево м.), Кандалакша, Беломорск, Архангельск (Белое м.), Диксон (Карское м.), Тикси (м. Лаптевых), Певек (Восточно-Сибирское м.); крупнейшие зарубежные порты – Тромсё и Тронхейм (Норвежское м.), Черчилл (Гудзонов зал.). Возд. пространство над С. Л. о. пересекают трассы из Зап. Европы к зап. берегам США (через Гренландию и Канаду).

Рыболовство

Ледоколы в североамериканском секторе Северного Ледовитого океана.

Фото Patrick Kelley

Моря С.-Е. б. и м. Баффина являются традиц. районами рыболовства и зверобойного промысла. В Баренцевом м., у берегов Исландии и в м. Баффина, ежегодно вылавливается св. 12 млн. т сельди, трески, палтуса, морского окуня и др. видов рыб. В др. районах рыболовство, как и зверобойный промысел, осуществляется исключительно в целях удовлетворения потребностей местного населения. Зверобойный промысел остаётся осн. источником существования коренного приморского населения севера Гренландии, Канады и Аляски.

Минеральные ресурсы

В недрах С. Л. о. заключены огромные запасы нефти и природного горючего газа. В пределы шельфовых морей продолжаются крупные нефтегазоносные провинции и бассейны, в их числе: Западно-Сибирская нефтегазоносная провинция, частично расположенная на шельфе Карского м. (Россия), Тимано-Печорская нефтегазоносная провинция, прослеживающаяся на шельфе Баренцева м. (Россия), Северные Арктические нефтегазоносные бассейны Канады, включающие два бассейна – Бофорта и Cвердруп, Северного склона Аляски нефтегазоносный бассейн (США). В акватории рос. и норв. секторов Баренцева м. и в сев. части Карского м. выделяется Баренцево-Северо-Карская нефтегазоносная провинция. Активная добыча нефти и газа идёт на шельфе Норвежского м. (Норвегия). Перспективно нефтегазоносны осадочные бассейны, приуроченные к зонам перехода континент – океан по периметру С. Л. о., а также шельфы морей Лаптевых, Восточно-Сибирского и Чукотского. Самое крупное нефтяное месторождение – Прадхо-Бей (в зал. Прадхо м. Бофорта). На мелководье Новосибирских о-вов (моря Лаптевых и Bосточно-Сибирское) известны россыпные месторождения касситерита. Мор. россыпи золота известны у побережья штата Аляска (США), Чукотского п-ова, архипелага Сев. Земля, п-ова Таймыр (Россия). На шельфах всех морей С. Л. о. – проявления и мелкие месторождения железомарганцевых конкреций. В прибрежной части арктич. морей практически неограниченные запасы строит. песков и галечников.

Историю исследования С. Л. о. см. в статьях Арктика, Северный морской путь, Северо-Западный проход, Северный полюс.

Обновлено: 26 августа 2020 в 12:17

40 530

Самым меньшим по площади океаном на Земле считается Северный Ледовитый. Он расположен в северном полушарии планеты, вода в нем холодная, а водная поверхность покрыта различными ледниками. Эта акватория начала формироваться в меловой период, когда с одной стороны Европа разделилась с Северной Америкой, а с другой было некоторое схождение Америки и Азии. В это время формировались линии крупных островов и полуостровов. Так, произошло деление водного пространства, и котловина Северного океана отделилась от Тихоокеанской. Со временем происходило разрастание океана, поднятие материков, а движение литосферных плит длится по сей день.

История открытия и изучения Северного Ледовитого океана

Долгое время Ледовитый океан считался морем, не очень глубоким, с холодными водами. Осваивали акваторию давно, использовали ее природные ресурсы, в частности добывали водоросли, ловили рыбу и животных. Только в девятнадцатом веке были проведены фундаментальные исследования Ф. Нансеном, благодаря которому удалось подтвердить, что Ледовитый является океаном. Да, он по площади гораздо меньше Тихого или Атлантического, но является полноценным океаном с собственной экосистемой, входит в Мировой океан.

С тех пор проводились комплексные океанографические исследования. Так, Р. Берд и Р. Амундсен в первой четверти двадцатого века провели исследования океана с высоты птичьего полета, их экспедиция была на самолете. Позднее были проведены научные станции, их оборудовали на дрейфующих льдинах. Это позволило изучить дно и рельеф океана. Так были открыты подводные горные хребты.

Одной из примечательных экспедиций была команда англичан, которые с 1968 по 1969 года пересекли океан пешком. Их путь длился из Европы в Америку, целью было изучение мира флоры и фауны, а также режима погоды.

Не раз Ледовитый океан изучали экспедиции на суднах, но это усложняется тем, что акватория покрыта ледниками, встречаются айсберги. Кроме водного режима и подводного мира, изучаются ледники. В перспективе изо льда добывать воду, пригодную для питья, так как в ней невысокое содержание соли.

Северный Ледовитый океан – это удивительная экосистема нашей планеты. Здесь холодно, дрейфуют ледники, но это перспективное место для освоения его людьми. Хоть в данный момент длятся исследования океана, но он еще малоизучен.

«Arctic Sea» redirects here. For the cargo ship, see MV Arctic Sea.

Coordinates: 90°N 0°E / 90°N 0°E

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world’s five major oceans.[1] It spans an area of approximately 14,060,000 km2 (5,430,000 sq mi) and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, although some oceanographers call it the Arctic Mediterranean Sea.[2] It has been described approximately as an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean.[3][4] It is also seen as the northernmost part of the all-encompassing World Ocean.

The Arctic Ocean includes the North Pole region in the middle of the Northern Hemisphere and extends south to about 60°N. The Arctic Ocean is surrounded by Eurasia and North America, and the borders follow topographic features: the Bering Strait on the Pacific side and the Greenland Scotland Ridge on the Atlantic side. It is mostly covered by sea ice throughout the year and almost completely in winter. The Arctic Ocean’s surface temperature and salinity vary seasonally as the ice cover melts and freezes;[5] its salinity is the lowest on average of the five major oceans, due to low evaporation, heavy fresh water inflow from rivers and streams, and limited connection and outflow to surrounding oceanic waters with higher salinities. The summer shrinking of the ice has been quoted at 50%.[1] The US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) uses satellite data to provide a daily record of Arctic sea ice cover and the rate of melting compared to an average period and specific past years, showing a continuous decline in sea ice extent.[6] In September 2012, the Arctic ice extent reached a new record minimum. Compared to the average extent (1979–2000), the sea ice had diminished by 49%.[7]

Decrease of old Arctic Sea ice 1982–2007

History[edit]

North America[edit]

Human habitation in the North American polar region goes back at least 17,000–50,000 years, during the Wisconsin glaciation. At this time, falling sea levels allowed people to move across the Bering land bridge that joined Siberia to northwestern North America (Alaska), leading to the Settlement of the Americas.[8]

Thule archaeological site

Early Paleo-Eskimo groups included the Pre-Dorset (c. 3200–850 BC); the Saqqaq culture of Greenland (2500–800 BC); the Independence I and Independence II cultures of northeastern Canada and Greenland (c. 2400–1800 BC and c. 800–1 BC); and the Groswater of Labrador and Nunavik. The Dorset culture spread across Arctic North America between 500 BC and AD 1500. The Dorset were the last major Paleo-Eskimo culture in the Arctic before the migration east from present-day Alaska of the Thule, the ancestors of the modern Inuit.[9]

The Thule Tradition lasted from about 200 BC to AD 1600, arising around the Bering Strait and later encompassing almost the entire Arctic region of North America. The Thule people were the ancestors of the Inuit, who now live in Alaska, Northwest Territories, Nunavut, northern Quebec, Labrador and Greenland.[10]

Europe[edit]

For much of European history, the north polar regions remained largely unexplored and their geography conjectural. Pytheas of Massilia recorded an account of a journey northward in 325 BC, to a land he called «Eschate Thule», where the Sun only set for three hours each day and the water was replaced by a congealed substance «on which one can neither walk nor sail». He was probably describing loose sea ice known today as «growlers» or «bergy bits»; his «Thule» was probably Norway, though the Faroe Islands or Shetland have also been suggested.[11]

Emanuel Bowen’s 1780s map of the Arctic features a «Northern Ocean».

Early cartographers were unsure whether to draw the region around the North Pole as land (as in Johannes Ruysch’s map of 1507, or Gerardus Mercator’s map of 1595) or water (as with Martin Waldseemüller’s world map of 1507). The fervent desire of European merchants for a northern passage, the Northern Sea Route or the Northwest Passage, to «Cathay» (China) caused water to win out, and by 1723 mapmakers such as Johann Homann featured an extensive «Oceanus Septentrionalis» at the northern edge of their charts.

The few expeditions to penetrate much beyond the Arctic Circle in that era added only small islands, such as Novaya Zemlya (11th century) and Spitzbergen (1596), though, since these were often surrounded by pack-ice, their northern limits were not so clear. The makers of navigational charts, more conservative than some of the more fanciful cartographers, tended to leave the region blank, with only fragments of known coastline sketched in.

19th century[edit]

This lack of knowledge of what lay north of the shifting barrier of ice gave rise to a number of conjectures. In England and other European nations, the myth of an «Open Polar Sea» was persistent. John Barrow, longtime Second Secretary of the British Admiralty, promoted exploration of the region from 1818 to 1845 in search of this.

In the United States in the 1850s and 1860s, the explorers Elisha Kane and Isaac Israel Hayes both claimed to have seen part of this elusive body of water. Even quite late in the century, the eminent authority Matthew Fontaine Maury included a description of the Open Polar Sea in his textbook The Physical Geography of the Sea (1883). Nevertheless, as all the explorers who travelled closer and closer to the pole reported, the polar ice cap is quite thick and persists year-round.

Fridtjof Nansen was the first to make a nautical crossing of the Arctic Ocean, in 1896.

20th century[edit]

The first surface crossing of the ocean was led by Wally Herbert in 1969, in a dog sled expedition from Alaska to Svalbard, with air support.[12] The first nautical transit of the north pole was made in 1958 by the submarine USS Nautilus, and the first surface nautical transit occurred in 1977 by the icebreaker NS Arktika.

Since 1937, Soviet and Russian manned drifting ice stations have extensively monitored the Arctic Ocean. Scientific settlements were established on the drift ice and carried thousands of kilometres by ice floes.[13]

In World War II, the European region of the Arctic Ocean was heavily contested: the Allied commitment to resupply the Soviet Union via its northern ports was opposed by German naval and air forces.

Since 1954 commercial airlines have flown over the Arctic Ocean (see Polar route).

Geography[edit]

The Arctic region; of note, the region’s southerly border on this map is depicted by a red isotherm, with all territory to the north having an average temperature of less than 10 °C (50 °F) in July.

Size[edit]

The Arctic Ocean occupies a roughly circular basin and covers an area of about 14,056,000 km2 (5,427,000 sq mi), almost the size of Antarctica.[14][15] The coastline is 45,390 km (28,200 mi) long.[14][16] It is the only ocean smaller than Russia, which has a land area of 16,377,742 km2 (6,323,482 sq mi).

Surrounding land and exclusive economic zones[edit]

The Arctic Ocean is surrounded by the land masses of Eurasia (Russia and Norway), North America (Canada and the U.S. state of Alaska), Greenland, and Iceland.

| Arctic exclusive economic zones[17] | |

|---|---|

| Country segment | Area (km2) |

| 2,088,075 | |

| 1,058,129 | |

| 1,199,008 | |

| 935,397 | |

| 804,907 | |

| 292,189 | |

| 756,112 | |

| 2,278,113 | |

| 2,276,594 | |

| 3,021,355 | |

| 508,814 | |

| Other | 1,500,000 |

| Arctic Ocean total | 14,056,000 |

Note: Some parts of the areas listed in the table are located in the Atlantic Ocean. Other consists of Gulfs, Straits, Channels and other parts without specific names and excludes Exclusive Economic Zones.

Subareas and connections[edit]

The Arctic Ocean is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Bering Strait and to the Atlantic Ocean through the Greenland Sea and Labrador Sea.[1] (The Iceland Sea is sometimes considered part of the Greenland Sea, and sometimes separate.)

The largest seas in the Arctic Ocean:[18][19][20]

- Barents Sea—1.4 million km2

- Hudson Bay—1.23 million km2 (sometimes not included)

- Greenland Sea—1.205 million km2

- East Siberian Sea—987,000 km2

- Kara Sea—926,000 km2

- Laptev Sea—662,000 km2

- Chukchi Sea—620,000 km2

- Beaufort Sea—476,000 km2

- Amundsen Gulf

- White Sea—90,000 km2

- Pechora Sea—81,263 km2

- Lincoln Sea—64,000 km2

- Prince Gustaf Adolf Sea

- Queen Victoria Sea

- Wandel Sea

Different authorities put various marginal seas in either the Arctic Ocean or the Atlantic Ocean, including: Hudson Bay,[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28]

Baffin Bay, the Norwegian Sea, and Hudson Strait.

Islands[edit]

The main islands and archipelagos in the Arctic Ocean are, from the prime meridian west:

- Jan Mayen (Norway)

- Iceland

- Greenland

- Arctic Archipelago (Canada, includes the Queen Elizabeth Islands and Baffin Island)

- Wrangel Island (Russia)

- New Siberian Islands (Russia)

- Severnaya Zemlya (Russia)

- Novaya Zemlya (Russia, includes Severny Island and Yuzhny Island)

- Franz Josef Land (Russia)

- Svalbard (Norway, including Bear Island))

Ports[edit]

There are several ports and harbours on the Arctic Ocean.[29]

- Alaska

- Utqiaġvik (Barrow)

- Prudhoe Bay

- Canada

- Manitoba: Churchill (Port of Churchill)

- Nunavut: Nanisivik (Nanisivik Naval Facility)[30]

- Tuktoyaktuk and Inuvik in the Northwest Territories

- Greenland: Nuuk (Nuuk Port and Harbour)

- Norway

- Mainland: Kirkenes and Vardø

- Svalbard: Longyearbyen

- Iceland

- Akureyri

- Russia

- Barents Sea: Murmansk in the Barents Sea

- White Sea: Arkhangelsk

- Kara Sea: Labytnangi, Salekhard, Dudinka, Igarka and Dikson

- Laptev Sea: Tiksi in the

- East Siberian Sea: Pevek in the East Siberian Sea

Arctic shelves[edit]

The ocean’s Arctic shelf comprises a number of continental shelves, including the Canadian Arctic shelf, underlying the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, and the Russian continental shelf, which is sometimes called the «Arctic Shelf» because it is larger. The Russian continental shelf consists of three separate, smaller shelves: the Barents Shelf, Chukchi Sea Shelf and Siberian Shelf. Of these three, the Siberian Shelf is the largest such shelf in the world; it holds large oil and gas reserves. The Chukchi shelf forms the border between Russian and the United States as stated in the USSR–USA Maritime Boundary Agreement. The whole area is subject to international territorial claims.

The Chukchi Plateau extends from the Chukchi Sea Shelf.

Underwater features[edit]

An underwater ridge, the Lomonosov Ridge, divides the deep sea North Polar Basin into two oceanic basins: the Eurasian Basin, which is 4,000–4,500 m (13,100–14,800 ft) deep, and the Amerasian Basin (sometimes called the North American or Hyperborean Basin), which is about 4,000 m (13,000 ft) deep. The bathymetry of the ocean bottom is marked by fault block ridges, abyssal plains, ocean deeps, and basins. The average depth of the Arctic Ocean is 1,038 m (3,406 ft).[31] The deepest point is Molloy Hole in the Fram Strait, at about 5,550 m (18,210 ft).[32]

The two major basins are further subdivided by ridges into the Canada Basin (between Beaufort Shelf of North America and the Alpha Ridge), Makarov Basin (between the Alpha and Lomonosov Ridges), Amundsen Basin (between Lomonosov and Gakkel ridges), and Nansen Basin (between the Gakkel Ridge and the continental shelf that includes the Franz Josef Land).

Geology[edit]

The crystalline basement rocks of mountains around the Arctic Ocean were recrystallized or formed during the Ellesmerian orogeny, the regional phase of the larger Caledonian orogeny in the Paleozoic Era. Regional subsidence in the Jurassic and Triassic periods led to significant sediment deposition, creating many of the reservoirs for current day oil and gas deposits. During the Cretaceous period, the Canadian Basin opened, and tectonic activity due to the assembly of Alaska caused hydrocarbons to migrate toward what is now Prudhoe Bay. At the same time, sediments shed off the rising Canadian Rockies built out the large Mackenzie Delta.

The rifting apart of the supercontinent Pangea, beginning in the Triassic period, opened the early Atlantic Ocean. Rifting then extended northward, opening the Arctic Ocean as mafic oceanic crust material erupted out of a branch of Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The Amerasia Basin may have opened first, with the Chukchi Borderland moved along to the northeast by transform faults. Additional spreading helped to create the «triple-junction» of the Alpha-Mendeleev Ridge in the Late Cretaceous epoch.

Throughout the Cenozoic Era, the subduction of the Pacific plate, the collision of India with Eurasia, and the continued opening of the North Atlantic created new hydrocarbon traps. The seafloor began spreading from the Gakkel Ridge in the Paleocene Epoch and the Eocene Epoch, causing the Lomonosov Ridge to move farther from land and subside.

Because of sea ice and remote conditions, the geology of the Arctic Ocean is still poorly explored. The Arctic Coring Expedition drilling shed some light on the Lomonosov Ridge, which appears to be continental crust separated from the Barents-Kara Shelf in the Paleocene and then starved of sediment. It may contain up to 10 billion barrels of oil. The Gakkel Ridge rift is also poorly understand and may extend into the Laptev Sea.[33][34]

Oceanography[edit]

Water flow[edit]

Density structure of the upper 1,200 m (3,900 ft) in the Arctic Ocean. Profiles of temperature and salinity for the Amundsen Basin, the Canadian Basin and the Greenland Sea are sketched.

In large parts of the Arctic Ocean, the top layer (about 50 m [160 ft]) is of lower salinity and lower temperature than the rest. It remains relatively stable because the salinity effect on density is bigger than the temperature effect. It is fed by the freshwater input of the big Siberian and Canadian rivers (Ob, Yenisei, Lena, Mackenzie), the water of which quasi floats on the saltier, denser, deeper ocean water. Between this lower salinity layer and the bulk of the ocean lies the so-called halocline, in which both salinity and temperature rise with increasing depth.

Because of its relative isolation from other oceans, the Arctic Ocean has a uniquely complex system of water flow. It resembles some hydrological features of the Mediterranean Sea, referring to its deep waters having only limited communication through the Fram Strait with the Atlantic Basin, «where the circulation is dominated by thermohaline forcing».[35] The Arctic Ocean has a total volume of 18.07 × 106 km3, equal to about 1.3% of the World Ocean. Mean surface circulation is predominantly cyclonic on the Eurasian side and anticyclonic in the Canadian Basin.[36]

Water enters from both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and can be divided into three unique water masses. The deepest water mass is called Arctic Bottom Water and begins around 900 m (3,000 ft) depth.[35] It is composed of the densest water in the World Ocean and has two main sources: Arctic shelf water and Greenland Sea Deep Water. Water in the shelf region that begins as inflow from the Pacific passes through the narrow Bering Strait at an average rate of 0.8 Sverdrups and reaches the Chukchi Sea.[37] During the winter, cold Alaskan winds blow over the Chukchi Sea, freezing the surface water and pushing this newly formed ice out to the Pacific. The speed of the ice drift is roughly 1–4 cm/s.[36] This process leaves dense, salty waters in the sea that sink over the continental shelf into the western Arctic Ocean and create a halocline.[38]

This water is met by Greenland Sea Deep Water, which forms during the passage of winter storms. As temperatures cool dramatically in the winter, ice forms, and intense vertical convection allows the water to become dense enough to sink below the warm saline water below.[35] Arctic Bottom Water is critically important because of its outflow, which contributes to the formation of Atlantic Deep Water. The overturning of this water plays a key role in global circulation and the moderation of climate.

In the depth range of 150–900 m (490–2,950 ft) is a water mass referred to as Atlantic Water. Inflow from the North Atlantic Current enters through the Fram Strait, cooling and sinking to form the deepest layer of the halocline, where it circles the Arctic Basin counter-clockwise. This is the highest volumetric inflow to the Arctic Ocean, equalling about 10 times that of the Pacific inflow, and it creates the Arctic Ocean Boundary Current.[37] It flows slowly, at about 0.02 m/s.[35] Atlantic Water has the same salinity as Arctic Bottom Water but is much warmer (up to 3 °C [37 °F]). In fact, this water mass is actually warmer than the surface water and remains submerged only due to the role of salinity in density.[35] When water reaches the basin, it is pushed by strong winds into a large circular current called the Beaufort Gyre. Water in the Beaufort Gyre is far less saline than that of the Chukchi Sea due to inflow from large Canadian and Siberian rivers.[38]

The final defined water mass in the Arctic Ocean is called Arctic Surface Water and is found in the depth range of 150–200 m (490–660 ft). The most important feature of this water mass is a section referred to as the sub-surface layer. It is a product of Atlantic water that enters through canyons and is subjected to intense mixing on the Siberian Shelf.[35][39] As it is entrained, it cools and acts a heat shield for the surface layer on account of weak mixing between layers.[40][41]

However, over the past couple of decades a combination of the warming[42] and the shoaling of Atlantic water[43] are leading to the increasing influence of Atlantic water heat in melting sea ice in the eastern Arctic. The most recent estimates, for 2016–2018, indicate the oceanic heat flux to the surface has now overtaken the atmospheric flux in the eastern Eurasian Basin.[44] Over the same period the weakening halocline stratification has coincided with increasing upper ocean currents thought to be associated with declining sea ice, indicate increasing mixing in this region.[45] In contrast direct measurements of mixing in the western Arctic indicate the Atlantic water heat remains isolated at intermediate depths even under the ‘perfect storm’ conditions of the Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012.[46]

Waters originating in the Pacific and Atlantic both exit through the Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard Island, which is about 2,700 m (8,900 ft) deep and 350 km (220 mi) wide. This outflow is about 9 Sv.[37] The width of the Fram Strait is what allows for both inflow and outflow on the Atlantic side of the Arctic Ocean. Because of this, it is influenced by the Coriolis force, which concentrates outflow to the East Greenland Current on the western side and inflow to the Norwegian Current on the eastern side.[35] Pacific water also exits along the west coast of Greenland and the Hudson Strait (1–2 Sv), providing nutrients to the Canadian Archipelago.[37]

As noted, the process of ice formation and movement is a key driver in Arctic Ocean circulation and the formation of water masses. With this dependence, the Arctic Ocean experiences variations due to seasonal changes in sea ice cover. Sea ice movement is the result of wind forcing, which is related to a number of meteorological conditions that the Arctic experiences throughout the year. For example, the Beaufort High—an extension of the Siberian High system—is a pressure system that drives the anticyclonic motion of the Beaufort Gyre.[36] During the summer, this area of high pressure is pushed out closer to its Siberian and Canadian sides. In addition, there is a sea level pressure (SLP) ridge over Greenland that drives strong northerly winds through the Fram Strait, facilitating ice export. In the summer, the SLP contrast is smaller, producing weaker winds. A final example of seasonal pressure system movement is the low pressure system that exists over the Nordic and Barents Seas. It is an extension of the Icelandic Low, which creates cyclonic ocean circulation in this area. The low shifts to centre over the North Pole in the summer. These variations in the Arctic all contribute to ice drift reaching its weakest point during the summer months. There is also evidence that the drift is associated with the phase of the Arctic Oscillation and Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation.[36]

Sea ice[edit]

Sea cover in the Arctic Ocean, showing the median, 2005 and 2007 coverage[47]

On the sea ice of the Arctic Ocean temporary logistic stations may be installed, Here, a Twin Otter is refueled on the pack ice at 86°N, 76°43‘W.

Much of the Arctic Ocean is covered by sea ice that varies in extent and thickness seasonally. The mean extent of the Arctic sea ice has been continuously decreasing in the last decades, declining at a rate of currently 12.85% per decade since 1980 from the average winter value of 15,600,000 km2 (6,023,200 sq mi).[48] The seasonal variations are about 7,000,000 km2 (2,702,700 sq mi), with the maximum in April and minimum in September. The sea ice is affected by wind and ocean currents, which can move and rotate very large areas of ice. Zones of compression also arise, where the ice piles up to form pack ice.[49][50][51]

Icebergs occasionally break away from northern Ellesmere Island, and icebergs are formed from glaciers in western Greenland and extreme northeastern Canada. Icebergs are not sea ice but may become embedded in the pack ice. Icebergs pose a hazard to ships, of which the Titanic is one of the most famous. The ocean is virtually icelocked from October to June, and the superstructure of ships are subject to icing from October to May.[29] Before the advent of modern icebreakers, ships sailing the Arctic Ocean risked being trapped or crushed by sea ice (although the Baychimo drifted through the Arctic Ocean untended for decades despite these hazards).

Climate[edit]

Changes in ice between 1990 and 1999

The Arctic Ocean is contained in a polar climate characterized by persistent cold and relatively narrow annual temperature ranges. Winters are characterized by the polar night, extreme cold, frequent low-level temperature inversions, and stable weather conditions.[52] Cyclones are only common on the Atlantic side.[53] Summers are characterized by continuous daylight (midnight sun), and air temperatures can rise slightly above 0 °C (32 °F). Cyclones are more frequent in summer and may bring rain or snow.[53] It is cloudy year-round, with mean cloud cover ranging from 60% in winter to over 80% in summer.[54]

The temperature of the surface water of the Arctic Ocean is fairly constant at approximately −1.8 °C (28.8 °F), near the freezing point of seawater.

The density of sea water, in contrast to fresh water, increases as it nears the freezing point and thus it tends to sink. It is generally necessary that the upper 100–150 m (330–490 ft) of ocean water cools to the freezing point for sea ice to form.[55] In the winter, the relatively warm ocean water exerts a moderating influence, even when covered by ice. This is one reason why the Arctic does not experience the extreme temperatures seen on the Antarctic continent.

There is considerable seasonal variation in how much pack ice of the Arctic ice pack covers the Arctic Ocean. Much of the Arctic ice pack is also covered in snow for about 10 months of the year. The maximum snow cover is in March or April—about 20–50 cm (7.9–19.7 in) over the frozen ocean.

The climate of the Arctic region has varied significantly during the Earth’s history. During the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum 55 million years ago, when the global climate underwent a warming of approximately 5–8 °C (9–14 °F), the region reached an average annual temperature of 10–20 °C (50–68 °F).[56][57][58] The surface waters of the northernmost[59] Arctic Ocean warmed, seasonally at least, enough to support tropical lifeforms (the dinoflagellates Apectodinium augustum) requiring surface temperatures of over 22 °C (72 °F).[60]

Currently, the Arctic region is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet.[61][62]

Biology[edit]

Due to the pronounced seasonality of 2–6 months of midnight sun and polar night[63] in the Arctic Ocean, the primary production of photosynthesizing organisms such as ice algae and phytoplankton is limited to the spring and summer months (March/April to September).[64] Important consumers of primary producers in the central Arctic Ocean and the adjacent shelf seas include zooplankton, especially copepods (Calanus finmarchicus, Calanus glacialis, and Calanus hyperboreus)[65] and euphausiids,[66] as well as ice-associated fauna (e.g., amphipods).[65] These primary consumers form an important link between the primary producers and higher trophic levels. The composition of higher trophic levels in the Arctic Ocean varies with region (Atlantic side vs. Pacific side) and with the sea-ice cover. Secondary consumers in the Barents Sea, an Atlantic-influenced Arctic shelf sea, are mainly sub-Arctic species including herring, young cod, and capelin.[66] In ice-covered regions of the central Arctic Ocean, polar cod is a central predator of primary consumers. The apex predators in the Arctic Ocean—marine mammals such as seals, whales, and polar bears—prey upon fish.

Endangered marine species in the Arctic Ocean include walruses and whales. The area has a fragile ecosystem, and it is especially exposed to climate change, because it warms faster than the rest of the world. Lion’s mane jellyfish are abundant in the waters of the Arctic, and the banded gunnel is the only species of gunnel that lives in the ocean.

Walruses on Arctic ice floe

Natural resources[edit]

Petroleum and natural gas fields, placer deposits, polymetallic nodules, sand and gravel aggregates, fish, seals and whales can all be found in abundance in the region.[29][51]

The political dead zone near the centre of the sea is also the focus of a mounting dispute between the United States, Russia, Canada, Norway, and Denmark.[67] It is significant for the global energy market because it may hold 25% or more of the world’s undiscovered oil and gas resources.[68]

Environmental concerns[edit]

Arctic ice melting[edit]

The Arctic ice pack is thinning, and a seasonal hole in the ozone layer frequently occurs.[69] Reduction of the area of Arctic sea ice reduces the planet’s average albedo, possibly resulting in global warming in a positive feedback mechanism.[51][70] Research shows that the Arctic may become ice-free in the summer for the first time in human history by 2040.[71][72] Estimates vary for when the last time the Arctic was ice-free: 65 million years ago when fossils indicate that plants existed there to as recently as 5,500 years ago; ice and ocean cores going back 8,000 years to the last warm period or 125,000 during the last intraglacial period.[73]

Warming temperatures in the Arctic may cause large amounts of fresh melt-water to enter the north Atlantic, possibly disrupting global ocean current patterns. Potentially severe changes in the Earth’s climate might then ensue.[70]

As the extent of sea ice diminishes and sea level rises, the effect of storms such as the Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 on open water increases, as does possible salt-water damage to vegetation on shore at locations such as the Mackenzie Delta as stronger storm surges become more likely.[74]

Global warming has increased encounters between polar bears and humans. Reduced sea ice due to melting is causing polar bears to search for new sources of food.[75] Beginning in December 2018 and coming to an apex in February 2019, a mass invasion of polar bears into the archipelago of Novaya Zemlya caused local authorities to declare a state of emergency. Dozens of polar bears were seen entering homes, public buildings and inhabited areas.[76][77]

Clathrate breakdown[edit]

Marine extinction intensity during the Phanerozoic

Millions of years ago

The Permian–Triassic extinction event (the Great Dying) may have been caused by release of methane from clathrates. An estimated 52% of marine genera became extinct, representing 96% of all marine species.

Sea ice, and the cold conditions it sustains, serves to stabilize methane deposits on and near the shoreline,[78] preventing the clathrate breaking down and outgassing methane into the atmosphere, causing further warming. Melting of this ice may release large quantities of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere, causing further warming in a strong positive feedback cycle and marine genera and species to become extinct.[78][79]

Other concerns[edit]

Other environmental concerns relate to the radioactive contamination of the Arctic Ocean from, for example, Russian radioactive waste dump sites in the Kara Sea,[80] Cold War nuclear test sites such as Novaya Zemlya,[81] Camp Century’s contaminants in Greenland,[82] and radioactive contamination from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.[83]

On 16 July 2015, five nations (United States, Russia, Canada, Norway, Denmark/Greenland) signed a declaration committing to keep their fishing vessels out of a 1.1 million square mile zone in the central Arctic Ocean near the North Pole. The agreement calls for those nations to refrain from fishing there until there is better scientific knowledge about the marine resources and until a regulatory system is in place to protect those resources.[84][85]

See also[edit]

- Arctic Bridge

- Arctic cooperation and politics

- Extreme points of the Arctic

- International Arctic Science Committee

- List of rivers of the Americas by coastline

- Nordicity

- Seven Seas

- Subarctic

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Pidwirny, Michael (2006). «Introduction to the Oceans». physicalgeography.net. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ General oceanography : an introduction (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley. 1980. p. 501. ISBN 0471021024. OCLC 6200221.

- ^ Tomczak, Matthias; Godfrey, J. Stuart (2003). Regional Oceanography: an Introduction (2nd ed.). Delhi: Daya Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7035-306-5. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2006.

- ^ «‘Arctic Ocean’ – Encyclopædia Britannica». Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

As an approximation, the Arctic Ocean may be regarded as an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean.

- ^ Some Thoughts on the Freezing and Melting of Sea Ice and Their Effects on the Ocean Archived 8 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine K. Aagaard and R. A. Woodgate, Polar Science Center, Applied Physics Laboratory University of Washington, January 2001. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ «Arctic Sea Ice News and Analysis | Sea ice data updated daily with one-day lag». Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ «Understanding the Arctic sea ice: Polar Portal». polarportal.dk. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Goebel T, Waters MR, O’Rourke DH (2008). «The Late Pleistocene Dispersal of Modern Humans in the Americas» (PDF). Science. 319 (5869): 1497–502. Bibcode:2008Sci…319.1497G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.398.9315. doi:10.1126/science.1153569. PMID 18339930. S2CID 36149744.

- ^ «The Prehistory of Greenland» Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Greenland Research Centre, National Museum of Denmark, accessed 14 April 2010.

- ^ Park, Robert W. «Thule Tradition». Arctic Archaeology. Department of Anthropology, University of Waterloo. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Pytheas Archived 18 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Andre Engels. Retrieved 16 December 2006.

- ^ «Channel 4, «Sir Wally Herbert dies» 13 June 2007″.

- ^ North Pole drifting stations (1930s–1980s) Archived 13 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- ^ a b Wright, John W., ed. (2006). The New York Times Almanac (2007 ed.). New York: Penguin Books. p. 455. ISBN 978-0-14-303820-7.

- ^ «Oceans of the World» (PDF). rst2.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ «Arctic Ocean Fast Facts». wwf.pandora.org (World Wildlife Foundation). Archived from the original on 29 October 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ «Sea Around Us | Fisheries, Ecosystems and Biodiversity». seaaroundus.org.

- ^ June 2010, Remy Melina 04 (4 June 2010). «The World’s Biggest Oceans and Seas». livescience.com.

- ^ «World Map / World Atlas / Atlas of the World Including Geography Facts and Flags — WorldAtlas.com». WorldAtlas.

- ^ «List of seas». listofseas.com.

- ^ Wright, John (30 November 2001). The New York Times Almanac 2002. Psychology Press. p. 459. ISBN 978-1-57958-348-4. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ «IHO Publication S-23 Limits of Oceans and Seas; Chapter 9: Arctic Ocean». International Hydrographic Organization. 2002. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Calow, Peter (12 July 1999). Blackwell’s concise encyclopedia of environmental management. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-632-04951-6. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ Lewis, Edward Lyn; Jones, E. Peter; et al., eds. (2000). The Freshwater Budget of the Arctic Ocean. Springer. pp. 101, 282–283. ISBN 978-0-7923-6439-9. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ McColl, R.W. (2005). Encyclopedia of World Geography. Infobase Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8160-5786-3. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ Earle, Sylvia A.; Glover, Linda K. (2008). Ocean: An Illustrated Atlas. National Geographic Books. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-4262-0319-0. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ Reddy, M. P. M. (2001). Descriptive Physical Oceanography. Taylor & Francis. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-5410-706-4. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ Day, Trevor; Garratt, Richard (2006). Oceans. Infobase Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8160-5327-8. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Arctic Ocean Archived 4 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. CIA World Fact Book

- ^ «Backgrounder – Expanding Canadian Forces Operations in the Arctic». Canadian Armed Forces Arctic Training Centre. 10 August 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ^ «The Mariana Trench – Oceanography». marianatrench.com. 4 April 2003. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 2 December 2006.

- ^ «Five Deeps Expedition is complete after historic dive to the bottom of the Arctic Ocean» (PDF).