Стивен Хокинг — биография

Стивен Хокинг известен мировой общественности как физик-теоретик, писатель, космолог, автор научных изданий. Автор космологической теории, которая объединила общую теорию относительности и квантовую механику.

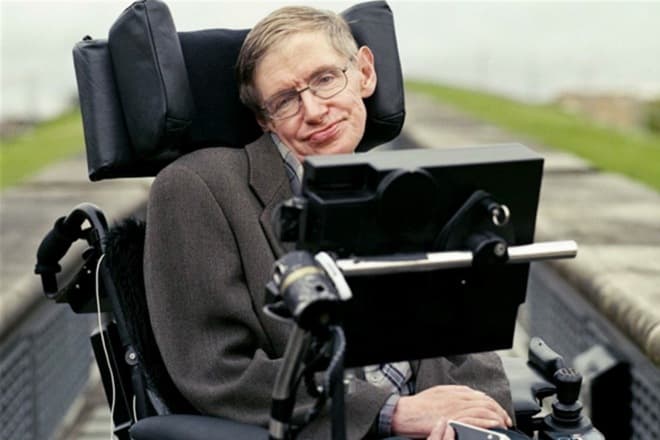

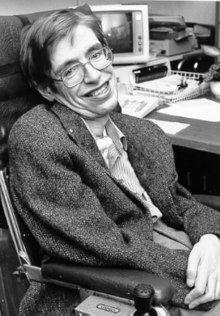

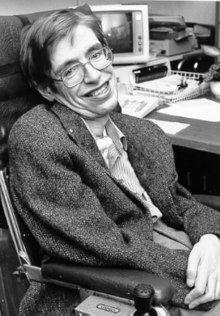

Стивена Хокинга не зря считают человеком-легендой, он оправдывает это звание на все сто. Известный космолог и астрофизик, он всю жизнь исследовал черные дыры, и писал книги, которые становились бестселлерами. Чего стоит только одна «Краткая история времени». Он всю жизнь страдал боковым амиотрофическим склерозом, который приковал его к инвалидному креслу. Но и это не сломило его дух и жажду к жизни, он так хотел заниматься своей любимой космологией. Он читал лекции студентам, писал книги, встречался с поклонниками, и предупреждал наивное человечество о том, что его ждет — развитие искусственного интеллекта, встреча с представителями инопланетных цивилизаций, переселение землян на другие планеты.

Детство

Родился Стивен Хокинг 8 января 1942 года в Оксфорде. Его родители были медиками. Отца звали Фрэнк Хокинг, он вел научно-исследовательскую деятельность. Мама Изабель Хокинг работала секретарем в медицинском учреждении, там же, где и ее супруг. Кроме Стива в семье подрастали две дочери и брат Эдвард, усыновленный Хокингами.

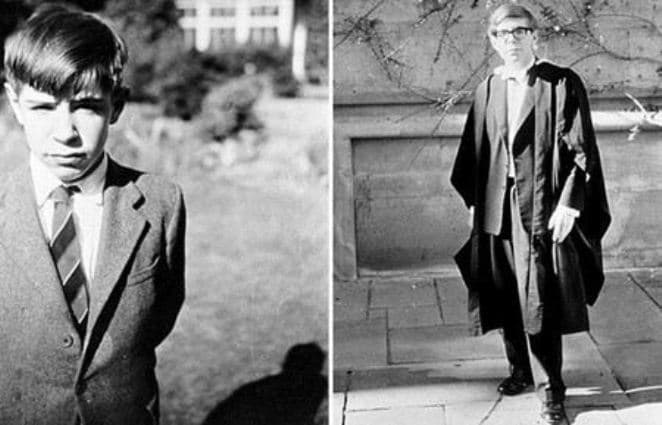

После окончания средней школы Стивен стал студентом Оксфордского университета, который окончил в 1962 году и получил диплом бакалавра. В 1966-м он защитил докторскую диссертацию и стал первым доктором философии в колледже Тринити-Холл в университете Кембриджа.

Болезнь

В детстве Стивен был настоящим крепышом, который практически никогда не болел. В юношеские годы эта тенденция продолжилась, у него абсолютно не было жалоб на здоровье. Тем большей неожиданностью стал диагноз, который доктора поставили ему после окончания университета. После долгих исследований оказалось, что он страдает боковым амиотрофическим склерозом.

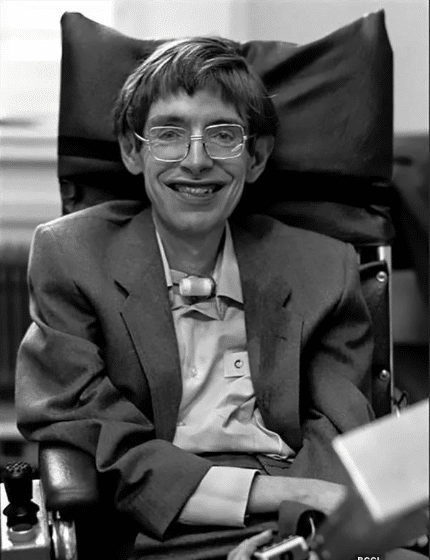

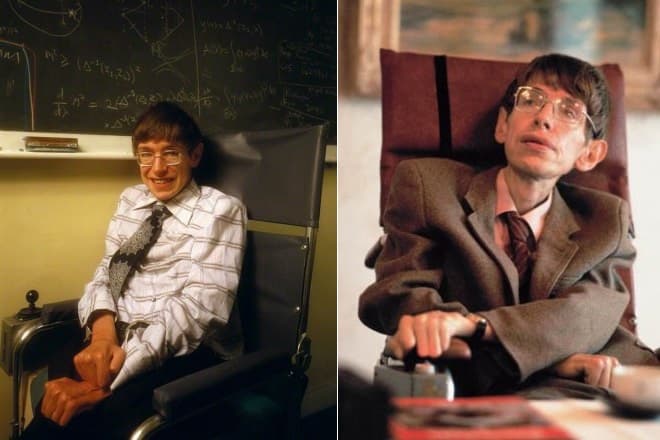

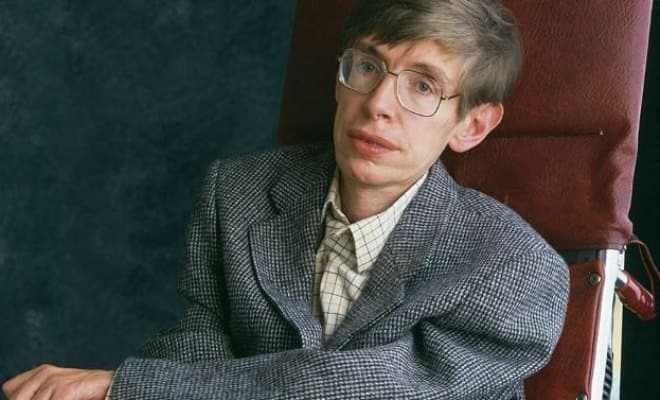

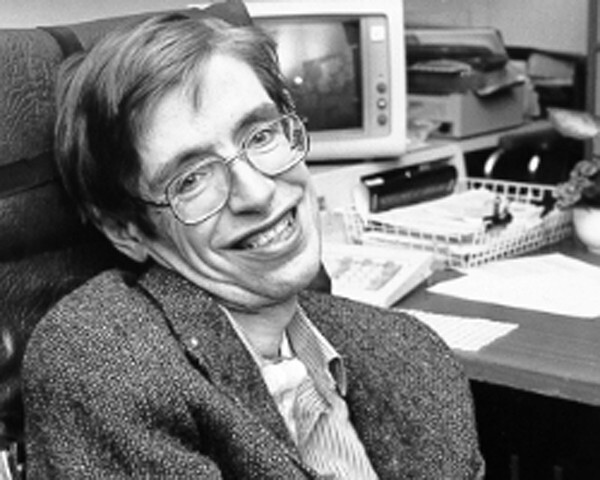

Это было равно приговору, причем болезнь очень быстро прогрессировала. Вскоре из молодого цветущего юноши он оказался в инвалидном кресле полностью парализованный. Но он старался не показывать на людях свои страдания и неуверенность в завтрашнем дне, поэтому на всех фотографиях он улыбался. На удивление, его улыбка была добродушной. Его тело было парализованным, а ум продолжал активно работать, он продолжал учиться, перечитал кучу научной литературы, участвовал в семинарах. Его борьба за жизнь не прекращалась ни на секунду. Благодаря твердости духа и силе воли он сумел стать постоянным членом Лондонского королевского общества. Это свершилось в 1974-м.

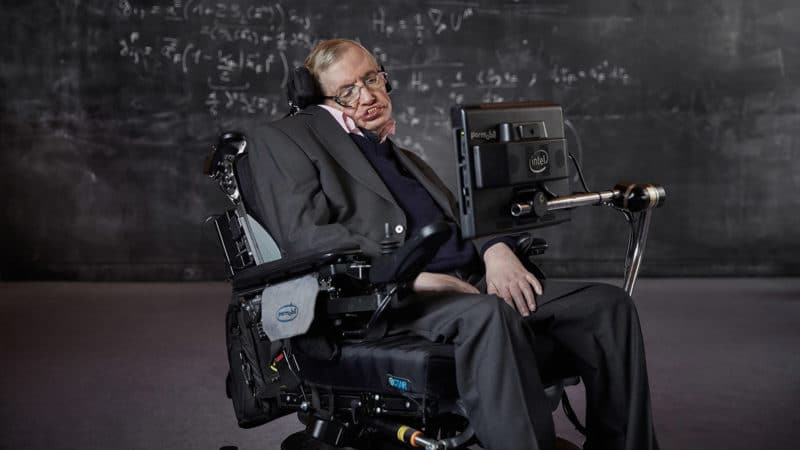

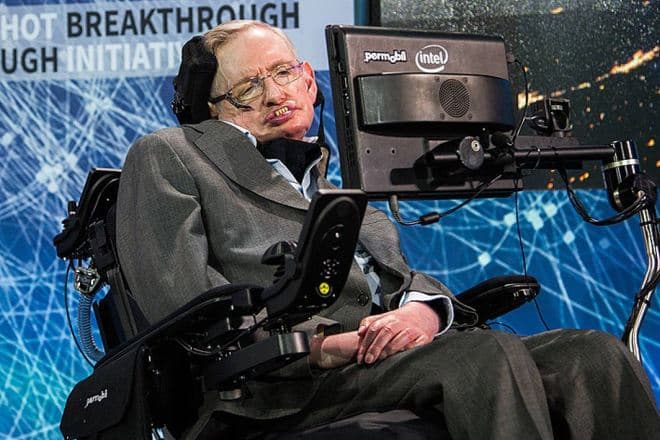

В 1985-м будущему светилу науки прооперировали гортань. Оперативное вмешательство потребовалось из-за того, что у него обострилась пневмония. После выписки из больницы он потерял речь, однако это не мешало ему продолжать общаться с родными и коллегами. Для этого он использовал синтезатор речи, который специально для него был разработан его друзьями из университета Кембриджа.

Поначалу у него шевелился указательный палец на правой руке, однако со временем он перестал чувствовать и его. Чувствительность сохранилась только в единственной мимической мышце на щеке, все остальное тело было неподвижным. Хокингу установили напротив нее сенсор, благодаря которому он мог управлять компьютером и только так общаться с окружением.

Трудно представить, сколько открытий мог совершить этот человек, будучи здоровым, если в таком незавидном положении сумел сделать многочисленные открытия в науке. Другой на его месте скорее всего сломился бы под тяжестью недуга, но только не Стивен. Его биография круто изменилась, но это пошло только на пользу научному сообществу. Будучи полностью парализованным, он не старался зацикливаться на недуге, у него была полноценная, насыщенная жизнь ученого, совершавшего одно открытие за другим.

Нашлось в его жизни место настоящему подвигу. Хокинг дал согласие на испытание своего немощного тела в условиях невесомости, он отправился в полет в кабине специально оборудованного под него летательного аппарата.

Этот полет состоялся в 2007-м и перевернул представление Стивена о мире, который находится вокруг него. У него появилась цель — во что бы то ни стало покорить космическое пространство до 2009-го года.

Могут быть знакомы

Физика

Стивен Хокинг был специалистом по космологии и квантовой гравитации. Он занимался исследованием термодинамических процессов, которыми характерны кротовы норы, черные дыры и темная материя. Его имя носит явление, которое описывает и характеризует так называемое испарение из черных дыр. Его назвали «излучением Хокинга».

В 1974-г между Стивеном и Кипом Торном возник научный спор, объектом которого был космический объект Лебедь «Х-1» и его излучение. Тогда Стивен в противоречие собственным исследованиям, придерживался точки зрения, что этот объект никакого отношения к черным дырам не имеет. Но он оказался не прав, поэтому в 1990-м ему пришлось отдать свой выигрыш Корну. А спорили они по серьезному, ставки были достаточно приличными.

В случае проигрыша Стивену пришлось бы расстаться с годовой подпиской на эротический глянец «Пентхаус» (что он и сделал в итоге), а Торну довелось бы распрощаться с четырехлетней подпиской на издание «Private eye».

В 1997-м Хокинг снова принимал участие в научном споре. Только теперь он был по одну сторону с Торном, а против них выступал Джон Филипп Прескил. Предметом спора стали исследования Хокинга, которые он представил в 2004 году участникам специальной конференции. Джон Прескилл утверждал, что волны, которые исходят из черных дыр, несут в себе информацию, не поддающуюся расшифровке.

Стивен был против такого утверждения, он аргументировал это результатами исследований, которые проводились в 1975 году. По его мнению, информация не расшифровывается потому, что она по пути оказывается во Вселенной, расположенной параллельно к нашей галактике.

Гораздо позже, в 2004-м, Стивен представил новые исследования природы черной дыры. Этими разработками он поделился с участниками пресс-конференции по космологии, состоявшейся в Дублине. Согласно этого заключения Хокинга снова ждало поражение, потому что по всему выходило, что его оппонент прав. Физик сумел доказать, что информация не теряется, а когда-то уйдет из черной дыры в сопровождении термического излучения.

Хокинг был не только выдающимся ученым, он сумел создать несколько документальных проектов о Вселенной.

В 2015-м на экраны вышла художественная лента под названием «Вселенная Стивена Хокинга», где роль главного героя досталась начинающему актеру из Голливуда Эдди Редмэйну. Продюсеры сошлись во мнении, что этот артист органичнее всего впишется в образ Хокинга. После проката картину буквально разобрали на цитаты, которые нашли отклик среди британской молодежи.

Режиссером фильма стал Джеймс Марш, он сумел достоверно передать биографию талантливого ученого, его достижения в науке и трудности в личной жизни. После премьерного показа молодого артиста наградили «Оскаром», как лучшего исполнителя мужской роли первого плана.

Книги

Помимо занятий наукой, Хокинг сумел проявить себя и в других сферах деятельности. Он стал автором нескольких книг, которые разлетелись по миру баснословными тиражами. Свою первую книгу он выпустил в 1988-м, под названием «Краткая история времени». Жанр ее художественно-научный, она вызывает интерес и сейчас.

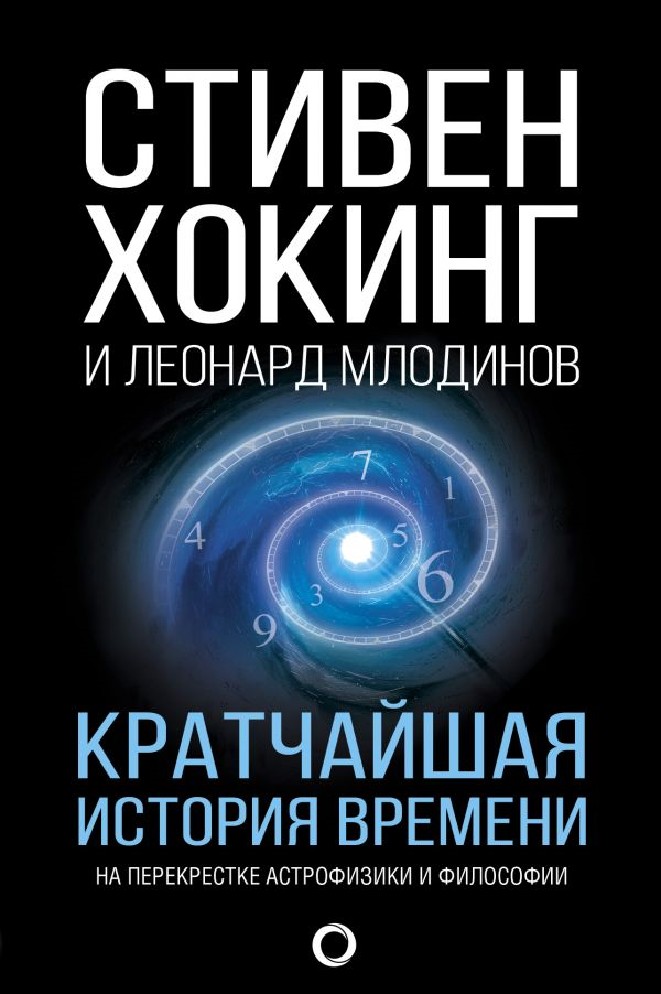

Потом вышла еще одна книга ученого, получившая название «Черные дыры и молодые вселенные», вслед за ней вышел еще один труд Стивена — «Мир в ореховой скорлупе». В 2005-м Хокинг и его соавтор — писатель Леонард Млодинов представили на суд читателей «Кратчайшую историю времени». В соавторстве с собственной дочерью ученый опубликовал свое новое детище — детскую книжку «Джорж и тайны Вселенной». Книга вышла в 2006 году.

Ближе к концу 1998-го Стивен стал автором подробного научного прогноза, о том, что ждет человечество в ближайшие тысячу лет. С докладом на эту тему он выступил в доме правительства. Тогда его прогноз был достаточно оптимистичным. Но в 2003-м он перестал питать радужные надежды и дал совет землянам серьезно задуматься о переселении на другие планеты, причем как можно дальше, чтобы спастись от вирусов, которые могут погубить цивилизацию.

Личная жизнь

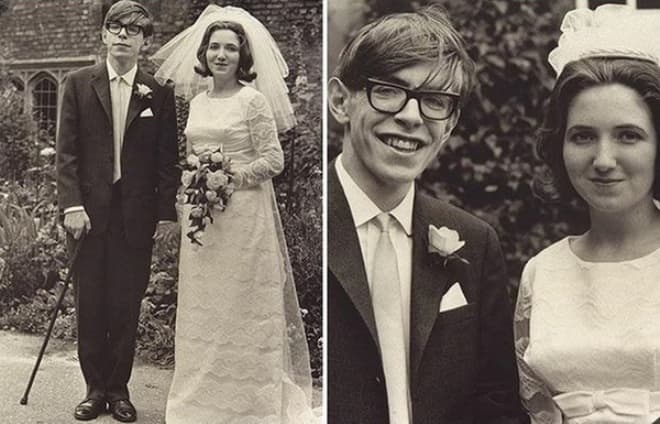

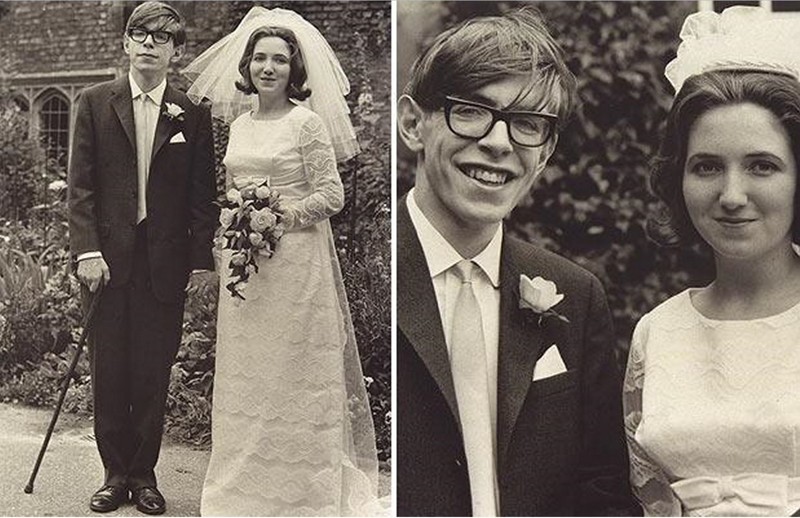

Первой женой Стивена Хокинга стала Джейн Уайльд, знакомство с которой состоялось во время благотворительного вечера. Они поженились в 1965 году, а спустя два года стали родителями сына Роберта. В 1970 году у них родилась дочь Люси, спустя девять лет еще один сын — Тимоти. Постепенно в их отношениях наметилось охлаждение, а потом они и вовсе сошли на нет. С 1990 года они стали жить отдельно, а через пять лет официально развелись. Что послужило поводом для развода, так и осталось тайной, об этом не было ни одной публикации в СМИ.

Буквально сразу после развода ученый женился снова. На этот раз его избранницей стала сиделка Элайн Мэйсон, которая проводила с ним много времени. Этот брак длился одиннадцать лет и тоже распался.

Дети великого ученого стали для отца настоящей поддержкой и опорой. Они делили с ним все его радости и печали. Помимо них Стивен постоянно ощущал дружеское плечо Джима Керри, известного комедийного голливудского актера.

Они были настоящими друзьями, вместе посещали публичные мероприятия и участвовали в фотосессиях для модного глянца.

Отношение к религии

Стивен всегда был приверженцем атеизма. Он не верил в Бога и отвергал любую теорию о его существовании. Но, несмотря на это, он получил благословение папы римского Франциска во время проведения специального симпозиума, проходившего в папской резиденции. Свои политические предпочтения Хокинг называл лейбористскими.

В 1968 году Стивен, общественный деятель Тарик Али и актриса Ванесса Редгрейв стали активными участниками акции против вьетнамской войны.

В 80-х Хокинг вместе с коллегами выступал в поддержку ядерного разоружения, сохранения здоровья и нормализации климатического состояния планеты Земля.

В 2003-м, когда президент США объявил о своем решении воевать в Ираке, Стивен Хокинг назвал его преступником, впрочем как и всех военных чиновников.

В том же 2003-м ученый выступил с поддержкой бойкота, который объявили участники конференции в Израиле. Они осуждали политическую власть, которая применялась в отношении палестинских граждан.

Перед смертью ученый много времени уделял новым исследованиям Вселенной, выступал с лекциями в институте, проводил активную исследовательскую деятельность.

Смерть

Стивен Хокинг всю жизнь стремился убежать от смерти. С самого начала он знал, что обречен, потому что от его болезни человечество пока не придумало лекарств. Он ушел скоропостижно, 14 марта 2018-го, у себя дома. Наследники Хокинга подтвердили достоверность информации, в свою очередь процитировав отца: » Вселенная не имела бы никакого смысла, если бы не представляла собой дом, где живут самые любимые и близкие люди».

Их утрата невосполнима, им будет его не хватать

Стивена Хокинга похоронили 15 июня того же года. Местом упокоения великого ученого стало Вестминстерское аббатство в Лондоне. Во время его похорон, в космос был отправлен сигнал, в котором было послание мира и надежды.

Его автором был сам Хокинг, слова которого звучали в музыкальном сопровождении, написанном греческим композитором Вангелисом к картине «Огненные колесницы». Радиосигнал отправила в космос спутниковая антенна, установленная на Европейском космическом агентстве. Сигнал направили к ближайшей черной дыре под именем 1А 0620-00. Дочь ученого Люси Хокинг сказала, что это послание станет символическим жестом, соединившим в себе земную жизнь ученого, его непреодолимое желание побывать в космосе и его исследования бесконечных просторов Вселенной.

Книги

- Крупномасштабная структура пространства-времени

- Чёрные дыры

- Общая теория относительности

- Геометрические идеи в физике

- Край Вселенной

- Краткая история времени: от Большого взрыва до чёрных дыр

- Чёрные дыры и молодые вселенные

- Кратчайшая история времени

- Мир в ореховой скорлупке

- Природа пространства и времени

- Джордж и тайны Вселенной

- Джордж и сокровища Вселенной

- Теория всего

- Большое, малое и человеческий разум

- Будущее пространства — времени

- Высший замысел

- Джордж и Большой взрыв

- Джордж и код, который не взломать

- Джордж и ледяной спутник

Фильмография

- «A Brief History of Time»

- «Stephen Hawking’s Universe»

- «Хокинг»

- «Стивен Хокинг.Моя история времени»

- «Теория всего»

- «Настоящий гений со Стивеном Хокингом»

- «Вселенная Стивена Хокинга»

- Теория Большого взрыва

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Стивен Уильям Хокинг (Stephen William Hawking, годы жизни: 08.01.1942 — 14.03.2018) – английский профессор, ученый, астрофизик, космолог, специалист по прикладной математике, писатель, преподаватель.

Хокингу принадлежит авторство крупных открытий в теории «черных дыр», создание теории квантовой гравитации. Помимо множества официальных наград, медалей и премий, Хокинг — владелец титулов «самый известный ученый после Эйнштейна», «величайший физик современности» и «основоположник квантовой космологии».

Одна из его книг, под название «Краткая история времени», в которой рассказывается о происхождении Вселенной — 237 недель входила в список бестселлеров (продано более 10 млн экземпляров) по версии газеты The Sunday Times. Коллеги восхищаются его вкладом в популяризацию научной деятельности.

Особо стоить отметить его непреодолимое стремление к жизни и борьба с боковым амиотрофическим склерозом. Это редкое неизлечимое заболевание, медленно развивающееся и приводящее к параличу. Оно настигло его в возрасте 21 года, после чего врачи отмерили гению всего два года жизни. Но вместо двух лет, он прожил 55 лет, да еще каких! Свою болезнь он смог сделать союзником и использовал ее для лучшей концентрации на своей деятельности.

Содержание

- 1 Семья и детские годы

- 2 Школьные годы

- 3 Университетские годы

- 4 Его болезнь

- 5 Личная жизнь

- 5.1 Первая жена

- 5.2 Вторая жена

- 6 Работа

- 7 Основные научные достижения

- 8 Роль Хокинга в популяризации научных сведений

- 9 Влияние на культуру

- 10 Личностные качества

- 11 Смерть ученого

Какие испытания судьбы выпали на долю ученого? Какой личностью был гений в инвалидной коляске? Об этом расскажет биография Стивена Хокинга.

Семья и детские годы

Стивен Уильям Хокинг (Stephen William Hawking) появился на свет во время войны, 8 января 1942 года в Оксфорде. В этот город переехали из Лондона его родители, поскольку там было безопаснее, чем в столице (с немцами существовала договоренность, что они не будут бомбить Оксфорд и Кембридж, взамен отказа англичан от авианалетов на Гейдельберг и Геттинген).

Родился Стивен ровно 300 лет спустя после смерти Галилея, о чем упоминал в автобиографии, добавляя, впрочем, что свое первое «агу» тогда же сказали «еще 200 000 младенцев».

Прадед Стивена Джон Хокинг был фермером, который обанкротился во времена сельскохозяйственной депрессии (начало ХХ века); дед Роберт Хокинг также не преуспел на ниве фермерства. Зато бабушка Стивена владела домом, в котором организовала школу. Благодаря этому Хокинги смогли оплатить высшее образование своего сына Фрэнка, отца Стивена.

Фрэнк Хокинг изучал в Оксфордском университете медицину, специализировался на тропических болезнях. Для их дальнейшего исследования в 1937 он переехал в восточный регион Африки.

Когда началась война, ученый вернулся на Родину и изъявил желание служить. Когда ему отказали («ваше место в медицине»), Фрэнк Хокинг начал работать в медицинском центре.

Мать Стивена Изабель Хокинг работала в том же центре секретарем. Она была родом из семьи доктора, где, кроме нее, было еще семеро детей. Несмотря на бедность, ее родители сумели оплатить обучение дочери в Оксфорде. Встреча Изабель с Фрэнком произошла в самом начале войны.

В 1942-м у пары появляется первенец – Стивен.

1,5 года спустя после появления сына, рождается дочь Мэри, а после – Филиппа, у которой со старшим братом была 5-летняя разница в возрасте. Когда Стивену было 14, родители взяли в семью приемного ребенка, так у Хокинга появился сводный брат Эдвард.

Одним из первых своих воспоминаний будущий гений называет «выход в свет»: в возрасте 2,5 лет родители впервые оставили его одного на детсадовской площадке. Опыт был плачевным в прямом и переносном смыслах: малыш испугался и расплакался. Хокинги, удивленные неготовностью сына к социализации, увели Стивена и еще 1,5 года держали на домашнем воспитании.

Так выглядел дом Хокингов в Хайгейте, где Стивен провел детские годы.

В детстве игрушки вызывали у Стивена желание понять, как работают системы, нравилось все разбирать. Он увлекался моделями кораблей, возился с заводным поездом.

Хокинг-старший брал сына к себе в лабораторию, где мальчугану нравилось смотреть в микроскоп. Правда, Стивен боялся, что инфицированные тропическими болезнями москиты могут выбраться и укусить его. Папа поощрял увлечение сына точными науками, занимался с ним математикой, пока тот не стал разбираться в предмете лучше него.

В 1950 семейство переезжает в городок Сент-Олбанс, расположенный в 30 км от Лондона.

Все отпуска, вплоть до 16-летия Стивена, семья проводила в цыганской повозке в окрестностях ОсмингтонМиллз, городка на морском побережье. Детям Хокинги из армейских носилок смастерили двухэтажные кровати, а сами ночевали в палатке.

Школьные годы

В 1-й класс Стивен пошел в 1952, в школу Сент-Олбанса для девочек, куда также брали и мальчиков. Интересно, что первая жена Стивена Джейн также обучалась в этом заведении. По ее воспоминаниям, описанным в книге «Быть Хокингом» (2007), детей Хокингов в школу привозили «на допотопном лондонском такси».

Поскольку это свидетельствовало про большую бедность, чтобы избежать насмешек сверстников, дети прятались на полу наемной машины.

Семейство Хокингов получило от Джейн следующие характеристики: «высокий, седовласый, представительный» (Хокинг-ст.), «маленькая, с поджарой фигуркой» (мать), «полная, неопрятная, рассеянная» (Мэри), «яркоглазая, легкая на подъем» (Филиппа). Стивена Джейн назвала «мальчиком с непослушными золотисто-каштановыми волосами».

Позже Стивен переходит в частную школу неподалеку. Самым скучным предметом для него становится физика: для мальчугана она слишком понятна и очевидна. Химию ученик считает более интересной, ведь на уроке часто что-то взрывается! Еще школьником Стивена начинает интересовать вопрос «откуда мы произошли?».

В 13 лет Хокинг-старший захотел перевести сына в частную Вестминстерскую школу, одну из престижнейших в стране. Из-за бедности, единственным для Стивена шансом там обучаться, был выигрыш гранта. Но во время проверки знаний на получение стипендии, мальчик заболел. Позже ученый утверждал, что получил в школе Сент-Олбанса отличное образование, которое, возможно, «даже лучше, чем в Вестминстере».

В 17 лет Стивен получает аттестат об окончании школы. Забавный факт: кроме данного документа у Хокинга не было ни одной официальной бумаги, подтверждающей, что он изучал математику. Когда в Кембридже он стал преподавать математику студентам-третьекурсникам, то опережал их в материале на неделю (по данным автобиографии; в Википедии приведен другой период «на две недели»).

Университетские годы

Юноше приходится самому сдавать выпускные и вступительные экзамены, поскольку его семья на год уезжает в Индию. В это время он живет у д-ра Джона Хамфри, коллеги отца. Для поступления Хокинг выбирает альма-матер родителей – Оксфордский университет. После сдачи в марте 1959-го экзаменов на получение стипендии, Хокинг был убежден, что не поступил. Для подавленного Стивена телеграмма о приеме в универ была полной неожиданностью.

На 1 и 2-м курсах Хокинг чувствовал себя довольно одиноко. Невысокого роста (1,65 м), он являлся одним из самых юных студентов, ведь многие его сокурсники уже успели отслужить в армии. На 3-м курсе для большей социализации и расширения круга общения, парень вступил в студенческий Гребной клуб и стал рулевым.

Курс физики в Оксфорде в те годы не требовал чрезмерных усилий, Хокинг «безмятежно изучал предмет в атмосфере полнейшей скуки». Прилежание вообще было не престижным, старательность и трудолюбие в стенах одного из старейших университетов страны расценивались как признак «посредственности». Светило науки признавался, что только его болезнь смогла переломить подобное отношение; поставленный диагноз дал стимул сделать для развития науки все, что в его силах.

Опасаясь, что шансы получить в Оксфорде степень с отличием малы, Хокинг разорвал недописанную работу и швырнул ее в мусорную корзину преподавателя. Комиссии, пряча неуверенность, он заявил, что если получит степень с отличием, то отправится писать диссертацию в Кембридж, а если не получит – то останется в Оксфорде. Экзаменаторы поставили ему высший балл, и в 1962-м, со степенью бакалавра (B.A.), Хокинг действительно прибывает в Кембридж как аспирант.

Его болезнь

В возрасте 21 года Стивен начинает замечать скованность в движениях: он спотыкается, не справляется с завязыванием шнурков. С тревожными симптомами молодой парень попадает в больницу, где после ужасных анализов ему сообщают, что у него неизлечимое заболевание — «боковой амиотрофический склероз». Это болезнь моторного нейрона, приводящая к параличу. Диагноз звучал, как приговор: в 1963-м врачи «отмерили» парню чуть больше 2 лет жизни.

На протяжении жизни болезнь парализовала Хокинга. С конца 1960-х он начинает постоянно пользоваться коляской.

Речь его постепенно ухудшалась, становилась невнятной. В 1985 году он заболел пневмонией. Срочная трахеостомия (операция на горле) обеспечила поступление воздуха в дыхательные пути, но после нее Хокинг потерял способность говорить.

Друзья презентовали ему синтезатор речи. Указательным пальцем правой руки, сохранившем подвижность, с помощью ручного манипулятора профессор осуществлял навигацию по синтезатору. Мысли Хокинга озвучивались механическим голосом, но ученый признавался, что он ему нравится, хоть и имеет американский акцент. Когда палец утратил подвижность, Хокинг смог общаться с окружающими благодаря подвижной мимической мышцы на щеке, где был установлен датчик, управляющий компьютером.

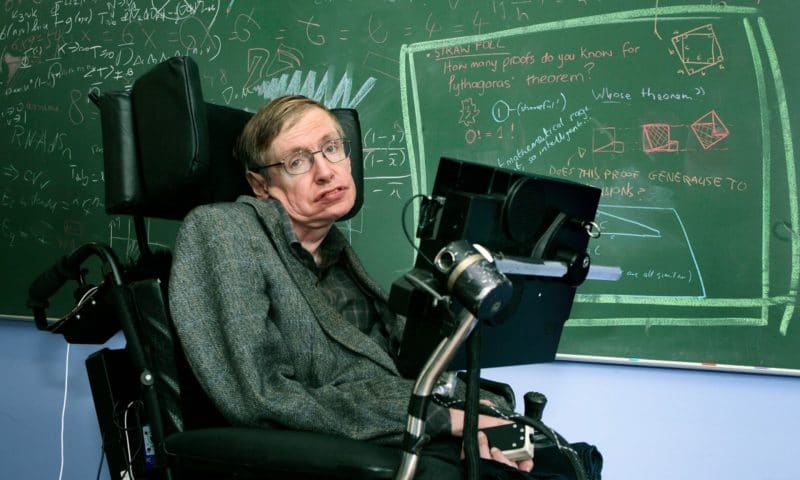

Хокинг сохранял чувство юмора, иронизировал по поводу своего состояния. Перед началом лекции, к примеру, мог сообщить: «Может, я не так хорошо выгляжу, как вам хотелось бы, но постараюсь компенсировать это интересными научными новостями».

Прогнозируемые врачами 2 года жизни он превратил в 55, наполненных плодотворной работой. Он стал настоящим медицинским феноменом.

Личная жизнь

Первая жена

Первой женой Хокинга становится Джейн Уайлд, та самая девочка, которая запомнила его, будучи в 1-м классе. Но то было лишь мимолетное детское воспоминание. Их первая осознанная встреча произошла на вечеринке, посвященной празднованию нового года, 1 января 1963. По словам Джейн, Стивена так смешили собственные истории, что иногда поток его речи прерывался приступами смеха, которые доходили до икоты.

Спустя пару дней, от нового знакомого пришло приглашение на вечеринку, планируемую 8 января. Подруга Джейн сообщила ей, что праздник приурочен к 21-летию Стивена (о чем не говорилось в приглашении). Джейн купила Стивену грампластинку, поскольку другой подарок для человека, с которым она только познакомилась, было трудно придумать.

После праздника Джейн на время утратила с приятелем связь, пока ее подружка не «огорошила» новостью, что Стивен уже 2 недели, как лежит на обследованиях в больнице.

Через неделю после известия Джейн встретила Хокинга на перроне, и согласилась, когда он пригласил ее в театр. После спектакля им пришлось вернуться в театр, потому что Джейн забыла кошелек. Когда в это время в театре погасили свет, девушку восхитило, как Стивен властно приказал ей «возьми меня за руку» и повел в темноте к выходу. Позже Хокинг пригласил Джейн на Майский бал в Кембридже. Девушка вспоминала, насколько опасно он вел тогда машину; позже она поняла, что это был его вызов диагнозу: спешить, чтобы успеть состояться, оставить свой след в жизни.

Их бракосочетание состоялось 14.07.65, а 15 июля они венчались в окрестностях Тринити холла.

Семейная жизнь с самого начала была непростой, но они были молоды и полны надежд: ему исполнилось 23, ей – 21. В аэропорту Кеннеди их даже как-то приняли за 16-летних, путешествующих «без присмотра взрослых».

Они много путешествовали, поскольку Хокинга начали приглашать на конференции. Его жена в шутку отметила, что специализация физиков менялась в зависимости от названия конференции: ученые быстро становились астрофизиками (когда планировалось научное собрание Астрофизического союза) или релятивистами (когда предстояла конференция по общей теории относительности).

Когда в 1967 у супругов появился сын Роберт, Стивен преданно поддерживал супругу, часами просиживая у кровати; и даже, вопреки правилам роддома, пробрался через запасной вход ее навестить. Когда их первенцу исполнилось 6 недель, в аэропорту по дороге в Сиэтл произошел следующий инцидент: Джейн оставила сына на руках у Стивена, сидящего в коляске, а когда вернулась, увидела, что малыш описался. «Лицо Стивена выражало нечеловеческую муку». И хотя брюки были отданы в химчистку, Стивен больше их не одевал.

Супруги привыкли жить одним днем, не планировали будущее, а разбирались с задачами по мере появления. Из юной девушки Джейн быстро превратилась, по своему определению, в «матрону», способную решать проблемы.

У Хокингов два сына и дочь: Роберт Джордж (28.05.1967), Люси (02.11.1970) и Тимоти (15.04.1979).

Физику супруга Хокинга называла «безжалостной соперницей» и «требовательной любовницей», а про коллег мужа говорила, что все они были приятными собеседниками, рассуждающими про «земные материи» поодиночке, однако как только они собирались вместе, начинали бесконечные дискуссии.

Джейн Хокинг понимала, что в ученом обществе Кембриджа ей необходимо состояться как личность, быть «лишь» женой и матерью означало потерпеть фиаско. В напряженном графике она находила время для написания диссертации в области средневековой литературы. Так в семье Хокингов стало два профессора. Джейн Хокинг была рядом с мужем 26 лет. По мнению дочери Люси, благодаря их свадьбе, Хокинг получил большой стимул жить и работать дальше.

Вторая жена

Однако отношения супругов постепенно сходили на нет, чему способствовало и… романтическое увлечение Хокинга собственной сиделкой, Элайн Мэйсон! В начале 80-х Элайн пригласили ухаживать за Хокингом в качестве профессиональной медсестры. Интересно, что ранее г-жа Мэйсон была замужем за инженером, который помогал разрабатывать синтезатор речи для гениального британца.

С 1990 Стивен и Джейн стали проживать в разных домах. В 1995 пара оформила официальный развод, и в том же году 53-летний профессор женился на Элайн. Церемонию бракосочетания не посетили ни Джейн, ни дети профессора.

После 11-ти лет супружеской жизни осенью 2006 Стивен и Элайн оформили развод, причину которого не стали разглашать.

Бывшая жена Хокинга Джейн тоже вышла замуж, в 1996 ее мужем стал друг семьи Джонатан Джонс.

Работа

Научным руководителем у одаренного аспиранта был Деннис Шама. Он поддерживал Стивена, считая, что тот способен на карьеру ньютоновского значения. В 1966 Хокинг в Trinity College Кембриджа защитил диссертацию и удостоился ученой степени Доктора философии (Ph.D.).

После удачной научной работы «Свойства расширяющихся вселенных» за Хокингом закрепился имидж талантливого новичка.

С 1968 он 4 года работает в Институте теоретической астрономии, после год занимается исследованиями в Институте астрономии. С 1973 в течение 2 лет работает на кафедре Кембриджского университета (прикладная математика и теоретическая физика), после читал студентам теорию гравитации, а с 1977 занимал должность профессора гравитационной физики.

На протяжении 30 лет с 1979 по 2009 со специализацией «теоретическая физика и космология» Хокинг работал в Кембридже лукасовским профессором математики (Lucasian Professor of Mathematics). На этом же почетном, одном из престижнейших в мире, академическом посту 310 лет назад работал и Исаак Ньютон.

В 1973 астрофизик приезжал в СССР и обговаривал с Я. Зельдовичем и А. Старобинским теоретические вопросы черных дыр. Приезжал Хокинг также и на научное мероприятие по квантовой теории гравитации, которое проходило в столице в 1981. Академик В. Рубаков вспоминает, что британец был «светлым человеком, с которым было приятно общаться, хотя и сложно».

В 2007 Хокинг организовал Центр теоретической космологии (Centre for Theoretical Cosmology) при Кембридже. По его словам, центр основан, чтобы «разработать теорию Вселенной, которая будет одновременно математически последовательной и проверяемой с точки зрения наблюдения».

Основные научные достижения

Если выражаться поэтично, то Хокинг стремился знать, «О чем думает Бог», найти ответ на вопрос попроще ему было неинтересно. Ученый посвятил свою жизнь поиску единого уравнения, которое отвечало бы на фундаментальные вопросы: «Почему мы здесь? Как появились? Откуда пришли?».

Космология и квантовая гравитация являлись основными областями научного исследования ученого. Величайшим достижением профессора считается теоретическое исследование излучения элементарных частиц, происходящее в черных дырах. Космологическая теория, представленная общественности в 1995, заявляла о том, что черные дыры «испаряются» и «излучают». Хокинг опроверг существующее мнение о черной дыре, как о «космическом каннибале», всасывающем все в свои недры. Ученый доказал, что черная дыра — не билет в один конец, она испаряет и излучает. Излучение получило имя первооткрывателя — «излучение Хокинга».

Интерес к явлению черных дыр у Хокинга пробудил блестящий математик Роджер Пенроуз. Процесс умирания звезды большой массы, в результате которого бесконечно возрастает ее плотность, увлек юного аспиранта. Хокинг задумался о явлении, противоположном образованию черной дыры: что, если представить процесс, обратный по времени? Не явление сжимания материи в одну микроскопическую точку, а наоборот, процесс появления из нее… всего?

Хокинг внес свой вклад в теорию Большого взрыва – космологической модели возникновения из крохотной точки расширяющейся Вселенной. В середине 60-х Хокинг получает премию Адамса (которую разделил с Пенроузом) за работу по математике «Сингулярности и геометрия пространства-времени».

Но ответив на один вопрос – как появилась Вселенная (из сингулярности), ученый озадачился раскрытием самой тайны сингулярности. Откуда появилась эта крохотная точка, из которой все произошло?

В 1971 ученый предположил понятие микроскопических черных дыр, масса которых составляет триллионы килограмм и не превышает объем элементарной частицы. В 2016 ученый назвал микродыры источником почти неограниченной энергии. Адронный коллайдер при своей работе теоретически способен создавать микродыры.

Появление искусственных черных дыр, пусть и микроскопических, вызывает определенные волнения у жителей планеты: «а не возникнет ли дыра, которая засосет всю Землю?».

Отвечая на вопросы касательно безопасности экспериментов, сотрудники коллайдера ссылаются на открытие Хокинга. Микродыры, утверждают они, являются неустойчивыми из-за «излучения Хокинга» и будут тут же испаряться.

1974-й приносит первое доказательство реального существования черных дыр. Ею оказывается Лебедь Х-1 — объект, где фиксировалось рентгеновское излучение в результате перетекания в нее вещества со звезды.

Факт, но именно Стивен Хокинг настаивал, что Лебедь Х-1 — вовсе не черная дыра! В 1974-м он даже заключил на эту тему шуточное пари с близким другом, американским физиком Кипом Торном. Стивен объяснял спор так – если я разочаруюсь, и Лебедь Х-1 – не черная дыра, я, по крайней мере, выиграю пари! На кону, к слову, стояла подписка на эротическое развлекательное издание Penthouse.

В 1990, после получения доказательств о наличии гравитационной сингулярности в системе, Хокинг признал, что был неправ.

В 70-х гг Хокинг осмысливал явление черных дыр перед сном, и однажды вечером его посетило озарение. Он решил применить квантовую механику к черной дыре и представил, как поведут себя маленькие элементарные частицы на ее границе.Термодинамические процессы упрощенно выглядят так: частицы с отрицательной массой поглощаются дырой, и тем самым уменьшают ее массу (со временем черная дыра «испаряется»), а частицы с положительной массой избегают поглощения и становятся источником излучения (черная дыра «излучает»). В поисках «единой теории всего», Хокинг в своем открытии сумел объединить «теорию малого» и «теорию большого» (квантовую механику и теорию относительности Эйнштейна).

Другой вопрос, над которым в последние годы трудился Хокинг – поглощение черной дырой информации. По его гипотезе, озвученной в 2015, информация не исчезает в области большого гравитационного притяжения, а оказывается на поверхности горизонта событий, принимая вид голограммы. Зная о том, что происходит на границе черной дыры, можно описать и ее состояние внутри.

Видео: Познавательный фильм «Стивен Хокинг и теория всего» доступно информирует, в чем заключаются основные научные открытия ученого

Стивен Хокинг был удостоен ряда престижных премий и наград: в 1978 получил премию Эйнштейна, 4 года спустя — Орден Британской империи, в 1989 удостоился Ордена Кавалеров Почета и др. С 1974 он входил в Лондонское королевское общество, был членом Папской академии наук (1986) и Национальной академии наук США (1992).

По опросу ВВС в 2002 Хокинг занял 25-е место среди «100 величайших британцев всех времен». Сам себя ученый гением не считал – «возможно, я неплох в чем-то, но я не Эйнштейн». Он называл себя «счастливчиком, который получает деньги за то, что занимается тем, что ему по душе».

Роль Хокинга в популяризации научных сведений

Стивен Хокинг не только занимался фундаментальной наукой, но и активно ее популяризовал. Его первое научно-популярное произведение «Краткая история времени» (1988) разошлось более 10 млн. экземплярами. Книга была переведена на 40 языков и входила в список наиболее популярных книг по версии The Sunday Times более 4,5 лет!

Свой успех автор комментировал так: «Я не хвастаюсь, я хочу отметить, насколько нам интересна наша Вселенная».

Далее последовали книги, также ставшие бестселлерами: «Черные дыры и молодые вселенные» (1993), «Мир в ореховой скорлупке» (2001), «Теория всего» (2006) и др., всего 17 книг. В соавторстве с дочкой Люси британец сочинил истории о приключениях непоседы Джорджа.

Хокинг обладал талантом переводить с языка ученого на простой человеческий, доходчиво освещал научные темы, знакомил читателей со строением и организацией Макрокосмоса.

Он также являлся автором фильмов: «Вселенная Стивена Хокинга» (1997), «Во Вселенную со Стивеном Хокингом» (2010), «Наука будущего Стивена Хокинга» (2014) и др.

Даже будучи в преклонном возрасте, чтобы удовлетворить спрос на свои выступления, Хокинг принимал приглашения на лекции. В 1998 на встрече в Белом доме, ученый дал человечеству на ближайшую тысячу лет вполне радужный прогноз. А вот уже в 2003 его заявления приобрели угрожающий характер: Хокинг посоветовал человечеству без промедления переселяться в другие миры.

О важности выйти за пределы Земли говорит и Илон Маск, мечтающий о колонизации Марса.

В декабре 2015 в Лондоне была представлена «Медаль Стивена Хокинга за научную коммуникацию». В рамках фестиваля STARMUS награда ежегодно вручается за существенный вклад в распространение знаний в науке, искусстве и кинематографе.

Влияние на культуру

Образ астрофизика уже давно стал культовым, а его имя является синонимом мужества и таланта. Ученый упоминается в литературе, музыке и фильмах. Голос профессора, который подарил ему синтезатор речи, присутствует и в песнях группы Pink Floyd, и в озвучке мультсериала «Симпсоны». А вот кадр из фильма про Гарри Поттера, где узник Азкабана увлечен «Краткой историей времени».

Хокинг появлялся в сериале «Теория большого взрыва»(в эпизоде «Возбуждение Хокинга»).

Видео: Для рекламы Jaguar ученый примерил на себя роль злодея

Об английском профессоре сняли несколько документальных лент: «Stephen Hawking: A Brief History Of Mine» (2013), «Настоящий гений со Стивеном Хокингом» (2016) и др.

Из художественных фильмов стоит отметить «Hawking» (2004, ВВС), ставший в 2005 номинантом академии BAFTA в категории «Лучший драматический фильм». В ленте сыграл Бенедикт Камбербэтч, которому и в дальнейшем будут удаваться роли ученых: Алана Тьюринга (в «Игре в имитацию» 2014), и Томаса Эдисона (в 2017 вышел трейлер нового фильма).

Еще один фильм «Theory of Everything» (2014) для российских зрителей известен как «Вселенная Стивена Хокинга». Актеры, сыгравшие супругов Хокинг, передают не только внешнюю схожесть, но и характеры прототипов.

В 2015 фильм получил «Оскар» за лучшую мужскую роль. Эдди Редмэйн, удачно воплотивший образ Хокинга, позже будет удостоен сказать прощальную речь на похоронах профессора.

Лента номинировалась в категории «лучший фильм», «лучшая женская роль» и «лучший адаптированный сценарий» (фильм базируется на книге Джейн Хокинг).

Личностные качества

Стивен Хокинг, несмотря на болезнь, оставался большим жизнелюбом. В 2012 на открытии Паралимпийских игр в Лондоне он заявил: «Нет такого понятия, как ничем непримечательное человеческое существование. Какой бы сложной ни казалась жизнь, всегда есть то, что вы можете сделать и преуспеть в этом».

Он старался вести, насколько это было возможным, активный образ жизни. В 2007 компания Zero Gravity подарила ему шанс испытать отсутствие земного притяжения. Пока Boeing-727, переоснащенный для этих целей, совершал виражи, скользя вниз по кривой, находящиеся на борту испытывали состояние невесомости. Стивен говорил, что полет стал для него настоящей свободой, а знающие его люди утверждали, что у него была самая большая, которую они когда-либо видели, улыбка. «Это было замечательно», — заверил профессор. Полеты манили Хокинга, он признался, что если бы он был кем-то типа Билла Гейтса, то арендовал бы космический корабль.

Видео: Видео полета

Профессор Кар Бернар утверждал, что способность преодолевать трудности Хокингу была дана от природы.

Хокинг был настойчивым и решительным во многих вопросах. Выступал за ядерное разоружение, борьбу с изменениями климата и всеобщее здравоохранение. Профессор поддерживал пацифистское движение: участвовал в 1968-м в антивоенном марше против конфликта во Вьетнаме, в 2003 войну в Ираке называл «военным преступлением» и т.д.

Астрофизик был любимцем СМИ. Способность видеть светлую сторону жизни и настойчивость перед лицом невзгод были важными аспектами его теплой и открытой личности.

Стивен Хокинг был любящим отцом, при жизни успел обзавестись внуком Уильямом Смитом (1997) от дочери Люси.

Ученый был атеистом, и про Бога высказывался так: «Я верю в Бога, если под ним подразумевается воплощение сил, управляющих Вселенной».

Его мемуары «Моя краткая история» (My Brief History, 2013) полны откровенных описаний его неординарной жизни.

Смерть ученого

Стивен Хокинг скончался на 76 году жизни 14 марта 2018 года в Кембридже. Причиной смерти стали осложнения, вызванные его болезнью. Похороны состоялись в церкви Св. Марии в центре Кембриджа 31 марта. Почтить память ученого собралось более полутысячи людей.

Его научная деятельность всегда была направлена на постижение основ Вселенной. В раскрытии загадок мироздания он внес существенный вклад.

Автор книги «Стивен Хокинг» Х. Мания назвал британца «абсолютным воплощением свободного духа и огромного ума».Тяжелая болезнь, почти на полвека приковавшая Хокинга к инвалидному креслу, не заставила его отступиться от своей мечты – разгадать Божий замысел. Гениальный ум, заключенный в теле с ограниченными возможностями, он стал живой демонстрацией того, что для человеческой деятельности не должно существовать границ.

Список использованных источников

- Стивен Хокинг. Моя краткая история (Stephen Hawking. My Brief History)

- Джейн Хокинг. Быть Хокингом (Jane Hawking. Travelling to infinity)

- Китти Фергюсон. Стивен Хокинг: жизнь и наука (Stephen Hawking: An Unfettered Mind)

- Стивен Хокинг и теория всего https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmcj2cRTCpg

- фильмы и сериалы про Хокинга https://24tv.ua/ru/umer_stiven_hoking_film_i_serialy_o_fizike_stivene_hokinge_n938302

- сайт Центра теоретической космологии http://www.ctc.cam.ac.uk/

- черная дыра в системе Лебедь https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/chandra/multimedia/cygnusx1.html

- 100 величайших британцев https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/100_величайших_британцев

и др.

Видео на десерт: Cлон прогнал надоедливых туристов

В когорту известных ученых-физиков входит Стивен Хокинг, биография которого связана с изучением глобальных проблем человечества. Научные труды космолога пополнили сокровищницу мировой науки. Перелистаем страницы жизни Стивена Хокинга, чтобы понять роль этого неординарного человека в развитии современной науки.

Стивен Хокинг: биография, личная жизнь

В биографии знаменитого ученого есть много интересных фактов. Астрофизик Стивен Хокинг (годы жизни — 1942–2018) известен всему миру как популяризатор научных исследований в космической сфере, астрофизике, социологии, а также как автор бестселлера «Краткая история времени».

Вот как сложился жизненный путь великого ученого:

Детство, отрочество и молодые годы

Семье британского медика Фрэнка Хокинга в годы Второй мировой войны пришлось переехать в Оксфорд, спасаясь от бомбежек Лондона. Здесь 8 января 1942 года у них появился крепкий и здоровый первенец, которого назвали Стивеном.

Стивен Хокинг в детстве сразу попал в научную среду. Отец и мать после окончания Оксфордского университета работали в медицинской сфере. Отец серьезно занимался исследованиями тропических болезней. У Стивена было две сестры, Мэри и Филиппа, а также брат Эдвард (приемный ребенок).

Окончив курс школьного обучения, будущий ученый поступил на физический факультет в Оксфордский университет. Получив степень бакалавра в 1962 году, продолжил учебу по специальности в Кембридже. В конечном итоге в 1966-м талантливый студент защитил магистерскую диссертацию по философии.

Молодой Хокинг занимался спортом, был душой компании, но судьба обошлась с ним жестоко. Тяжелая болезнь, разрушающая нервную систему, приковала ученого к инвалидному креслу. Сильный духом, он не стал поддаваться унынию, утвердив свою дееспособность стремлением к новым открытиям. Многих людей по всему миру поражало и вдохновляло его мужество и настойчивость.

Ученый постоянно занимался научными разработками, много читал и сотрудничал со знаменитыми людьми. Заслуги Хокинга оценили по достоинству:

- В 1974 году он получил постоянное членство в Лондонском королевском обществе.

- В 1979-м пополнил когорту профессуры, получив самую престижную академическую должность — Лукасовский профессор математики. Такой чести еще в XVII веке удостоился Исаак Ньютон.

Мировое научное сообщество отметило гениальные открытия выдающегося ученого новыми званиями, десятками наград и премий.

Семья и дети

Болезнь забирала у молодого ученого физические силы, но не могла сломить силу духа. Стивен Хокинг, личная жизнь которого имеет яркие и темные страницы, смотрел в будущее с оптимизмом.

Хокинг был дважды женат. Впервые он женился в 1965 году, когда страшный вердикт врачебной комиссии — боковой амиотрофический склероз — уже был вынесен. Женой будущего научного светила стала студентка Кембриджского университета Джейн Уайлд, которая родила ему троих детей.

Дети Стивена Хокинга родились совершенно здоровыми. С детства им пришлось много путешествовать вместе с отцом и матерью, которая везде сопровождала мужа. Судьбы наследников сложились таким образом:

- Роберт Хокинг — старший сын (родился в 1967 году) — стал инженером-программистом. Сейчас живет с семьей в США и работает с Microsoft.

- Кэтрин Люси Хокинг — дочь ученого (родилась в 1970-м) — занялась литературной и педагогической деятельностью, проживает в Лондоне.

- Тимоти Хокинг — младший сын (1979 год рождения) — получил университетское образование и работает в компании LEGO исполнительным директором.

После 25 лет супружества отношения разладились, а через 5 лет был оформлен развод. Сиделка Элайн Мэйсон — женщина, с которой связал свою жизнь Стивен Уильям Хокинг. Супруга стала главным помощником ученого. Расстались супруги в 2006-м, когда главным смыслом жизни исследователя стала наука.

Путь великого деятеля прервался на 77 году жизни. Стивен Хокинг, дата смерти которого записана на надгробной плите в Вестминстерском аббатстве (Лондон), оставил после себя огромное научное наследие.

Стивен Хокинг: вклад в науку

Работая в Кембридже, ученый успевал путешествовать по миру и заниматься исследованием электромагнитного излучения. Его научные взгляды произвели настоящую революцию в физике и открыли новое направление — квантовую космологию.

Биография Стивена Хокинга полна фактов о его научных открытиях и гипотезах. Рассмотрим их детальнее:

Открытия в науке

Занимаясь изучением космоса и электромагнитных излучений, Стивен Уильям Хокинг сделал несколько важных открытий:

- Опираясь на теоремы, сформулированные известным профессором Роджером Пенроузом, ученый подтвердил существование черных дыр согласно теории гравитационной сингулярности. Большой взрыв во Вселенной, по его мнению, мог произойти в результате появления бесконечно маленькой точки (сингулярности).

- Энергию, излучаемую черными дырами, назвали «излучением Хокинга». За потоком энергии происходит потеря массы черной дыры. Ученый связывал этот процесс с квантовым эффектом вблизи их горизонта событий.

- Космолог выдвинул гипотезу о существовании большого количества маленьких черных дыр в период Большого взрыва. Дыры были сверхгорячими и теряли массу, пока не исчезли. Накапливаемая в них энергия освободилась во время мощного взрыва.

- В 70-е годы ХХ века профессор изучал вопрос о частицах и световых излучениях, попадающих в черные дыры.

- В соавторстве с американским физиком Джеймсом Хартлом астрофизик разрабатывал теорию волновой функции Вселенной, применяя в исследованиях квантовую механику. Но историю космоса не удалось описать одной математической формулой, хотя концепция Хартла — Хокинга допускала существование параллельных вселенных, где есть планеты, похожие на Землю.

В 1990-е годы Стивен Хокинг продолжал изучать черные дыры, руководствуясь принципом космической цензуры. Последние 20 лет жизни ученый сосредоточился на информационном парадоксе черной дыры. Он признал, что информация после испарения черных дыр остается во Вселенной, но для человека она не доступна.

Книги

Особенной страницей в биографии физика-теоретика стала его литературная деятельность. Кроме научных диссертаций и трактатов, профессор создал серию научно-популярных произведений. Самые известные из них:

- «Краткая история времени» (1988);

- «Черные дыры и молодые вселенные» (1980);

- «Мир в ореховой скорлупке» (2001);

- «Кратчайшая история времени» (2005) и «Высший замысел» (2010) в соавторстве с Леонардом Млодиновым;

- «Джордж и тайны Вселенной» (2006) — книга для детей в соавторстве с дочерью Люси;

- «Теория всего» (2006);

- «Моя краткая история. Автобиография» (2013).

Стивен Хокинг, болезнь которого прогрессировала, продолжал вести активный образ жизни до конца своих дней:

- Он выступал с докладами, писал книги, путешествовал, летал в невесомости и даже планировал побывать в космосе.

- Его цифровым голосом (после операции на горле он пользовался синтезатором речи) озвучены мультипликационные герои в «Симпсонах», «Гриффинах».

- Хокинга можно увидеть в эпизодах сериалов «Звездный путь», «Теория Большого взрыва», в которых зрителю открываются достижения всей его жизни.

Стивен Хокинг, биография которого содержит огромное количество интересных событий и фактов, не только великий физик-теоретик XXI века, последователь великого Исаака Ньютона.

Он настоящий гений, олицетворяющий собой стойкость, мужество и принципиальность в изучении тайн Вселенной. Он человек будущего, у которого природа отобрала физическое здоровье, но наделила острым умом, талантом, любовью к жизни.

Оригинал статьи: https://www.nur.kz/family/school/1894505-stiven-hoking-biografia-licnaa-zizn-otkrytia-ucenogo/

Биография

Физик-теоретик и учёный с мировым именем Стивен Уильям Хокинг родился 8 января 1942 года в городе Оксфорд, Великобритания, в семье медиков. Отец Фрэнк занимался научно-исследовательской деятельностью, мать Изабель занимала должность секретаря медицинского учреждения, работая в одном коллективе с супругом. Стив рос в компании двух сестёр и сводного брата Эдварда, которого усыновила семья Хокингов.

Окончив среднюю школу, Стивен поступил в Оксфордский университет, по окончанию которого в 1962 получил степень бакалавра. Спустя два с половиной года, в 1966 году, молодой человек стал одним из первых докторов философии колледжа Тринити-Холл при Кембриджском университете.

Болезнь

С ранних детских лет Стивен был здоровым мальчиком, даже в юности его не беспокоили никакие недуги. Но в молодости с ним случилось несчастье. У молодого Стивена обнаружили страшную болезнь – боковой амиотрофический склероз.

Диагноз прозвучал, как приговор. Симптомы заболевания развивались с огромной скоростью. В результате будущий гений науки остался полностью парализованным. Несмотря на это, на фото Стивен Хокинг всегда предстает с доброй улыбкой. Будучи прикованным к инвалидному креслу, Стивен не останавливался в умственном развитии, занимался самообразованием, штудировал научную литературу, посещал семинары. Парень боролся каждую минуту. Его моральный дух помог в 1974 году получить постоянное членство в Лондонском королевском обществе.

В 1985 году Стивен Хокинг перенес операцию на гортани, которой невозможно было избежать из-за осложнившейся пневмонии. С тех пор Стивен полностью перестал разговаривать, но продолжал активно контактировать с коллегами при помощи синтезатора речи, разработанного его друзьями – инженерами Кембриджского университета — специально для него.

Некоторое время Хокинг мог шевелить указательным пальцем правой руки. Но и эта способность со временем утратилась. Подвижной осталась единственная мимическая мышца щеки. Сенсор, установленный напротив этой мышцы, помог Стивену в управлении компьютером, с помощью которого он мог общаться с окружающими его людьми.

Несмотря на тяжелый недуг, биография Стивена Хокинга наполнена радужными событиями, научными открытиями и достижениями. Страшное заболевание не сломило Стивена, только чуть изменило течение жизни. Практически полностью парализованный Стивен Хокинг не видел преград в собственном недуге, вёл полноценную насыщенную работой жизнь.

Однажды Хокинг совершил настоящий подвиг. Он согласился испытать на себе условия пребывания в невесомом пространстве, совершив полет на специально оборудованном летательном аппарате. Это событие, произошедшее в 2007 году, полностью видоизменило представление Стивена Хокинга об окружающем мире. Ученый поставил себе цель – покорить космос не позднее 2009 года.

Физика

Основная специализация Стивена Хокинга – космология и квантовая гравитация. Учёный исследовал термодинамические процессы, возникающие в кротовых норах, чёрных дырах и тёмной материи. Его именем названо явление, описывающее и характеризирующее «испарение черных дыр» — «излучение Хокинга».

В 1974 году Стивен и еще один известный в то время специалист Кип Корн поспорили о природе космического объекта Лебедь «Х-1» и его излучении. Стивен, умудряясь противоречить собственным исследованиям, доказывал, что этот объект не является черной дырой. Однако, потерпев поражение, отдал в 1990 году выигрыш победителю спора. Следует отметить, что ставки молодых парней были довольно «серьёзными». Стивен Хокинг поставил на кон свою годовую подписку на эротический глянцевый журнал «Penthouse», а Кип Корн – четырехлетнюю подписку на юмористический журнал «Private eye».

В 1997 году Стивен Хокинг заключил еще одно пари, но теперь вместе с Кипом Торном против Джона Филиппа Прескилла. Спорная дискуссия стала отправной точкой в революционном исследовании Стивена Хокинга, с докладом о котором он выступил на специальной пресс конференции 2004 года. По мнению Джона Прескилла, в волнах, которые излучают чёрные дыры, есть некая информация, которую невозможно расшифровать.

Хокинг противоречил данному доводу, опираясь на результаты проведенных исследований 1975 года. Он утверждал, что информацию невозможно подвергнуть расшифровке, поскольку она попадает во Вселенную, параллельную нашей галактике.

Позже, в 2004 году, в рамках пресс-конференции в Дублине на тему космологии Стивен Хокинг выдвинул новую теорию о природе черной дыры. Этим заключением Хокинг снова потерпел поражение в споре, вынужденно признав правоту оппонента. В своей теории физик все-таки доказал, что информация не исчезает бесследно, но однажды покинет чёрную дыру вместе с термическим излучением.

Стивен Хокинг является автором нескольких документальных фильмов о Вселенной.

В 2015 году состоялась премьера полнометражного художественного фильма «Вселенная Стивена Хокинга», в которой молодого учёного исполнил выдающийся голливудский актёр Эдди Редмэйн, по мнению продюсеров, идеально подходящий на эту роль. Фильм разошелся на цитаты, которые активно использует британская молодежь.

Кинокартина в режиссёрской работе Джеймса Марша содержит подлинную историю Стивена, рассказывает о его непростых отношениях с первой женой Джейн Уайльд. Молодой актёр, исполнивший роль легендарного учёного и космолога Стивена Хокинга, после премьеры получил «Оскар» за лучшую мужскую роль первого плана.

Книги

Кроме прочих заслуг и достижений в сфере науки, Стивен Хокинг прославился и в другой области. Он написал несколько книг, разлетевшихся по миру огромным тиражом. Первой его работой стала книга, вышедшая в 1988 году. Художественно-научное произведение под названием «Краткая история времени» доныне остается бестселлером.

Также ученый стал автором книг «Черные дыры и молодые вселенные», «Мир в ореховой скорлупе». В 2005 году он написал ещё одну книгу «Кратчайшая история времени», теперь в соавторстве с писателем Леонардом Млодиновым. Вместе со своей дочерью Стивен Хокинг написал и выпустил книгу для детей «Джорж и тайны Вселенной», которая была выпущена в 2006-ом.

В конце 1998 года учёный составил подробный научный прогноз о судьбе человечества на ближайшее тысячелетие. Соответствующий доклад был сделан в доме правительства. Его доводы звучали достаточно оптимистично. В 2003 заявление исследователя было уже не таким ободряющим, он посоветовал человечеству, не задумываясь, переселяться в другие обитаемые миры подальше от вирусов, которые угрожают нашему выживанию.

Личная жизнь

В 1965 году Стивен Хокинг женился на Джейн Уайльд, с которой познакомился на благотворительном вечере. Девушка родила ученому двоих сыновей и дочь. Личная жизнь Стивена Хокинга с супругой не сложилась, и в 1991 году у них состоялся развод. Официальные причины развода не были преданы огласке.

Уже в 1995 году Стивен Хокинг женился во второй раз, на своей сиделке Элайн Мэйсон, которая долгое время ухаживала за ученым. После одиннадцатилетнего брака Хокинг также развелся с женой.

Дети Стивена Хокинга поддерживали отца во всех его делах и начинаниях. Кроме них учёного постоянно поддерживал его близкий друг, голливудский артист жанра комедии Джим Керри, с которым он не раз появлялся на вечерах и фотосессиях для журналов.

Политика и религия

Учёный отвергал всякую теорию о существовании Бога и являлся атеистом. Несмотря на этот факт, его благословил папа римский Франциск на специальном симпозиуме, который проходил в стенах научной академии папской резиденции. По политическим предпочтениям Стивен Хокинг относит себя к лейбористам.

Весной 1968 года учёный вместе с общественным деятелем Тариком Али и киноактрисой Ванессой Редгрейв принял участие в акции против войны во Вьетнаме.

Позже, 80-е годы, ученый поддержал идею своих коллег о ядерном разоружении, всеобщем здравоохранении и нормализации глобального климата Земли.

Решение американского президента, приведшее к войне на территории иракской республики в 2003 году, учёный назвал преступлением военных чиновников. В том же году он поддержал бойкот участников израильской конференции по вопросам политической власти в отношении жителей Палестины.

Последние годы Стивен Хокинг работал над новыми вопросами Вселенной, давал лекции по физике в институте, занимался активной исследовательской деятельностью.

Смерть

Британские СМИ сообщили, что рано утром 14 марта 2018 года Стивен Хокинг умер в своем доме. Дети ученого подтвердили данную информацию, заявив:

«Однажды он сказал: «Во вселенной не было бы особенного смысла, если бы она не была домом, в котором живут любимые люди». Мы всегда будем по нему скучать»»

Содержание

- Детские и юношеские годы

- Болезнь

- Стивен Хокинг: кто это и чем он знаменит?

- Выдающиеся достижения ученого

- 4 закона механики черных дыр

- «Излучение Хокинга»

- Изучение сингулярности

- Теория о «нисходящей космологии»

- Расширение теории космической инфляции

- Теоретическая модель «состояние Хартла-Хокинга»

- Политика

- Какие книги Стивена Хокинга стоит почитать каждому?

- Личная жизнь

- Заключение

Стивен Уильям Хокинг – ученый с мировым именем, человек-легенда. Это выдающийся физик-теоретик, космолог и писатель, автор множественных научных работ. Его книги, ставшие бестселлерами сразу после публикации, предупреждают человечество о скором инопланетном вторжении, переселении жителей Земли на другие планеты, а также о развитии искусственного интеллекта и его влиянии на человеческую цивилизацию.

Несмотря на страшное заболевание – амиотрофический склероз, ученый всю жизнь занимался исследованием черных дыр, читал лекции, создавал научные работы, писал книги и проводил встречи с многочисленными поклонниками. Сегодня в каждом уголке планеты знают, кто такой Стивен Хокинг, и какой вклад он внес в развитие космологии, астрологии, физики и литературы.

Детские и юношеские годы

Родился будущий великий физик 8 января 1942 года в Оксфорде. Семья мальчика приехала сюда из Лондона, где в тот момент происходили военные действия. Отец Стивена – Фрэнк Хокинг, занимался исследованиями в области медицины, мать – Изабель Хокинг, работала секретарем в этом же научном центре. У них было еще двое родных детей и один усыновленный.

Уже в детстве Стивен проявлял страсть к науке. Он интересовался устройством Вселенной, читал много литературы на тему космоса и активно изучал физику. В юношеском возрасте его увлечение только усилилось, и Хокинг получил образование в Оксфордском университете, а затем – в Кембриджском.

В 1965 году Хокинг стал исследователем в Кембриджском университете, но вскоре перешел в Институт теоретической астрономии, где проработал с 1968 по 1972 год. Позднее молодой ученый начал преподавать теорию гравитации, получил звание профессора гравитационной физики и математики.

Болезнь

В детстве Стивен был совершенно обычным здоровым ребенком, который редко жаловался на самочувствие. Все знали его как активного, любознательного и жизнерадостного ребенка. Мальчик проявлял страсть к науке с ранних лет и мечтал стать ученым, к чему впоследствии и пришел. Он все свободное время посвящал чтению научной литературы, и вскоре понял, к чему его душа лежит больше всего – Хокинг полюбил космос. Но внезапно для всех и, в первую очередь, для него самого, произошла беда – в возрасте 21 года парень узнал о своем диагнозе – боковом амиотрофическом склерозе.

Страшная неизлечимая болезнь разделила жизнь юноши на «до» и «после». Его состояние ухудшалось с каждым днем, и врачи не могли ничем помочь стремительно увядающему молодому ученому. Вскоре он был вынужден передвигаться на коляске, так как его организм перестал выполнять простейшие двигательные функции.

Однако страшное заболевание никак не отразилось на ясности его ума. Тяжелый инвалид ежедневно занимался наукой и писательством, постоянно пополнял багаж знаний, посещал лекции и семинары выдающихся преподавателей и в целом старался вести обычный образ жизни. Благодаря стойкому моральному духу в 1974 году ученый стал постоянным членом Лондонского королевского общества, а за всю оставшуюся жизнь удостоился множества наград и медалей.

В 1985 году у Хокинга была обнаружена пневмония. Из-за осложнений врачам пришлось провести сложную операцию на гортани, последствием которой стала потеря голоса. С этого момента ученый мог общаться только при помощи синтезатора речи, созданного для него друзьями из Кембриджского университета. Уникальное устройство позволяло ему не только сообщать о своих просьбах, но и усердно заниматься наукой через управление компьютером.

На протяжении нескольких лет Хокинг еще мог совершать движения одним пальцем, но вскоре и он стал парализован. Обладала подвижностью только одна мимическая мышца на лице, за счет которой работал установленный сенсор – единственная возможность ученого взаимодействовать с внешним миром и заниматься наукой. Благодаря поддержке друзей и родных он не чувствовал себя одиноким, находясь в трудном положении.

Несмотря на тяжелейшее заболевание, выдающийся астрофизик никогда не сдавался и по-прежнему совершал важные научные открытия, изучал труды своих коллег и читал много книг. Проблемы со здоровьем не убили в нем желание открывать новое, хоть и значительно изменили ход жизни.

В 2007 великий ученый совершил настоящий подвиг – он испытал на себе условия пребывания в невесомости, после чего у Хокинга появилась цель – успеть побывать в космосе до 2009 года. Однако, эта цель оказалась недостижимой, он так и не смог реализовать желаемое.

Стивен Хокинг: кто это и чем он знаменит?

Хокинг – выдающийся ученый, который работал в области квантовой космологии и является одним из ее создателей. Главным интересом физика на протяжении всей его жизни был космос. Особое внимание он уделял исследованию черных дыр.

Астрофизик изучил черные дыры при помощи законов термодинамики и выяснил, что они «испаряются» из-за излучения, которое вошло в науку под названием «излучение Хокинга».

Одна из самых известных теорий ученого состоит в том, что в космосе есть множество микроскопических черных дыр, которые имеют размер с протон и при этом весят миллиарды тонн. Хокинг утверждал, что черные дыры обладают неограниченной энергией.

Также ученый считал, что черные дыры «проглатывают» информацию, но не разрушают ее полностью. А после испарения эта информация высвобождается. Причем Хокинг отрицал теорию о том, что черная дыра является «коротким путем на другой конец Вселенной», называя эту точку зрения ничем иным, как фантастическими домыслами.

Долгое время известный физик увлекался научными спорами, предметом которых выступали, как правило, какие-либо не до конца изученные вопросы в области черных дыр. Спорил он на годовые подписки эротических печатных изданий, которые в 70-е годы были очень популярны. Что удивительно – инициатор споров почти всегда проигрывал, но полученные знания он сразу же вносил в свои теории.

С 1979 по 2009 г. Хокинг занимал престижную должность Лукасовского профессора в Кембриджском университете. В 2015 году была представлена «Медаль Стивена Хокинга за научную коммуникацию», которая предназначается для награждения выдающихся деятелей за популяризацию научных знаний. Великий ученый получил огромное количество премий и Медалей за вклад в науку, среди которых Медаль Эйнштейна, Золотая медаль Высшего совета по научным исследованиям, Президентская медаль свободы, Премия по фундаментальной физике и др.

Выдающиеся достижения ученого

Великий астрофизик оставил после себя огромное наследие. За свою долгую и нелегкую жизнь он успел сформировать важнейшие фундаментальные предположения и теории, которые многое дали человечеству.

4 закона механики черных дыр

Стивен Хокинг вместе с коллегами открыл четыре закона механики черных дыр, в которых подробно описаны физические свойства этого космического явления.

«Излучение Хокинга»

На протяжении долгих лет считалось, что ни одна материя не способна покинуть черную дыру. Но Хокинг сформировал теоретическое предположение о том, что из черных дыр исходит излучение, которое в дальнейшем совершает движение до момента полного растворения. Это излучение впоследствии было названо «излучением Хокинга».

Изучение сингулярности

В совместной работе с Роджером Пенроузом предложены аргументы о существовании сингулярности и выдвинута теория о том, как появилась Вселенная. Гравитационная сингулярность – это точка с неограниченно большой массой в неограниченно малом пространстве. В сингулярности не действуют законы физики, а гравитация начинает быть бесконечной.

Теория о «нисходящей космологии»

Совместно с Томасом Хертогом была видвинута теория о «нисходящей космологии», которая подразумевает, что Вселенная имела сразу множество исходных состояний. Согласно этой теории, восходящая модель Вселенной становится невозможной, а вместо нее появляется нисходящая модель, так как известно конечное состояние Вселенной – это то, что существует сейчас. У этой теории появилось больше сторонников, чем критиков.

Расширение теории космической инфляции

Теория космической инфляции была выдвинута в 1980 году Аланом Гутом. Согласно этой теории, после Большого Взрыва происходило экспоненциальное расширение Вселенной, но впоследствии этот процесс замедлился. Хокинг сумел рассчитать происходящие при этом квантовые флуктуации и объяснил, какое влияние они могли оказать на расширение галактик во Вселенной. Предложенная согласно этой теории модель Вселенной получила как одобрение научной общественности, так и критику.

Теоретическая модель «состояние Хартла-Хокинга»

Стивен Хокинг совместно с Джеймсом Хартлом выдвинул теорию о том, что до Большого Взрыва временного измерения не существовало. Исходя из этой теории, концепция о начале Вселенной становится бессмысленной. На сегодняшний день идея об отсутствии времени до появления Вселенной имеет больше всего сторонников.

Политика

Стивен Хокинг придерживался лейбористских взглядов. До болезни он активно участвовал в политической жизни своей страны. Всю жизнь ученый поддерживал идею ядерного разоружения, призывал всех вести борьбу с глобальным потеплением и совершенствовать здравоохранение. Хокинг назвал «военным преступлением» вооруженный конфликт в Ираке, был категорически не согласен с израильской политикой в отношении палестинцев.

Какие книги Стивена Хокинга стоит почитать каждому?

За долгие годы жизни (особенно для его диагноза) британский ученый создал множество удивительных литературных изданий, получивших высокие оценки в научном мире. Но не обязательно быть ученым, чтобы понять произведения Хокинга. Тем, кто еще не знаком с творчеством великого физика, стоит начать с таких книг как:

- «Черные дыры и молодые вселенные»

- «Краткая история времени»

- «Джордж и тайны Вселенной» (эта книга создавалась совместно с дочерью ученого, Люси Хокинг).

- Любители науки оценят также удивительный документальный малосерийный фильм «Вселенная Стивена Хокинга».

Прочитал все его работы

3.45%

Прочитал некоторые из них

24.14%

Нет, но обязательно прочитаю

41.38%

Личная жизнь

Хокинг впервые женился в 1965 году на Джен Уайльд, которую он встретил на благотворительном вечере. В браке появилось трое детей, но постепенно чувства между ними остыли и пара рассталась. Официальный развод состоялся в 1995 году, но бывшие супруги начали жить отдельно еще 5 лет назад.

Вскоре после развода с первой женой Стивен официально зарегистрировал отношения со своей сиделкой Элайн Мэйсон, с которой он проводил большую часть своего времени. Несмотря на физическое состояние ученого, второй брак продлился 11 лет, но после тоже распался.

Все трое детей во взрослой жизни стали настоящими друзьями, не забывали они и о больном отце. Стивен всегда чувствовал их поддержку, дети часто навещали отца и помогали в исполнении его просьб.

Хокинг близко общался с известным комедийным актером Джимом Керри. Между ними была настоящая дружба, длившаяся долгие годы. Они вместе бывали на публичных мероприятиях и снимались на обложки модных журналов. У него также было много друзей и товарищей из научной среды.

Стивен Хокинг скончался в возрасте 76 лет в своём доме в Кембридже в ночь на 14 марта 2018 года после осложнений, вызванных его недугом.

Заключение

Сложно даже представить, какие открытия смог бы совершить великий ученый, если бы в его жизнь не внесла коррективы страшная болезнь. В истории человечества нет подобных случаев, когда парализованный человек мог бы вести столь бурную научную деятельность. Стивен Хокинг не сломился перед трудностями и до самой смерти трудился на благо всего человечества, делая открытия одно за другим.

Он никогда не зацикливался на своем недуге и каждый день старался прожить с пользой. Его биография полна удивительных фактов, так как ученый вел очень насыщенную и интересную жизнь. Стивен Хокинг – пример яркой, сильной личности, достойной подражания. Он доказал всему миру, что даже будучи обездвиженным, человек может достигнуть вершин интеллектуального развития.

Высший разум. Подлинная история Стивена Хокинга

Автор:

08 января 2017 08:53

Стивен Хокинг родился 8 января 1942 года. А умереть самый известный в мире учёный, согласно вердикту медиков, должен был 50 лет тому назад.

«Собственный IQ интересует лишь неудачников»

«Мы всего лишь развитые потомки обезьян на маленькой планете с ничем не примечательной звездой. Но у нас есть шансы постичь Вселенную. Это и делает нас особенными». Эти слова принадлежат тому, кого многие уважаемые и авторитетные учёные с разных континентов считают лучшим умом человечества на рубеже второго и третьего тысячелетия.

Британский физик-теоретик не просто занят познанием устройства Вселенной, он, выступая в качестве популяризатора науки, пытается донести знания до широких масс. В апреле 1988 года Хокинг выпустил ставшую бестселлером книгу «Краткая история времени (От Большого Взрыва до чёрных дыр)» — своеобразный учебник об устройстве Вселенной, пространства и времени «для чайников».

«Моя цель очень проста. Я хочу понимать Вселенную, почему она устроена так, как устроена, и зачем мы здесь», — вот как объясняет свои устремления учёный. Если вы думаете, что задача постижения законов мироздания — это удел людей с высоким IQ, то и на это у Стивена Хокинга готов ответ: «Я понятия не имею, какой у меня IQ. Те, кого это интересует, — просто неудачники».

Этот выдающийся учёный с невероятным чувством юмора уже много лет не разговаривает с человечеством привычным нам способом. И дело тут не в гордыне — из-за тяжелейшей болезни единственная возможность общения для Хокинга — это компьютер с синтезатором речи.

Смертный приговор в 21 год.

Он родился в 1942 году в Оксфорде, куда его родители перебрались из Лондона — город регулярно подвергался налётам гитлеровской авиации. Отец Стивена, Фрэнк Хокинг, работал исследователем в медицинском центре в Хампстеде. Его мать, Изабель, трудилась там же секретарём.

Он с детства походил на учёного — не слишком складная фигура, очки и прозвище «Зубрила» за чрезмерный интерес к скучным, с точки зрения ровесников, научным дебатам. При этом первым учеником в школе Стивен не был никогда. Его способности и интересы сводились к математике, физике и химии, а к остальным предметам он был равнодушен.

В 1959 году он стал студентом Оксфордского университета, однако и там не проявлял большого рвения. Учёбе и научной деятельности в ту пору он посвящал час в день. «Я не горжусь этой нехваткой работы, я только описываю своё отношение к учёбе, которое полностью разделяло большинство моих сокурсников. В Кембридже уже предполагалось, что вы блестящий студент, без усилия, в другом случае можно было принять ограниченность своих способностей и закончить учёбу после средней школы», — вспоминал Хокинг.

Он занимался космологией, собираясь открыть тайны мироздания, но не знал, что внутри него самого тикает бомба с часовым механизмом. Стивен вдруг заметил, что стал слишком часто и беспричинно спотыкаться. Обратился к врачам, и те после обследования вынесли вердикт — боковой амиотрофический склероз. Это неизлечимое заболевание центральной нервной системы, которое приводит к параличу и атрофии всех мышц тела. Неизбежная смерть наступает от отказа дыхательных путей.

21-летнему студенту Хокингу было сказано, что в запасе у него два года жизни. Ну, от силы два с половиной.

Инвалидная коляска и трое детей.

На столе лежала начатая диссертация… А нужна ли она теперь? Хокинг решил: обязательна нужна. Он должен успеть сделать хоть что-то из того, что задумал. И началась гонка со временем, когда тело с каждым днём слушалось всё хуже и хуже.

В разгар этой борьбы Хокинг познакомился с очаровательной девушкой Джейн и влюбился. Он захотел не просто прожить дольше, он захотел создать семью. Но разве может красавица ответить взаимностью полностью погружённому в физику очкарику, приговорённому врачами?

Джейн Уайлд не просто ответила, она стала его музой и помощницей. Но чтобы жениться на Джейн, Стивену Хокингу нужно было сделать две вещи — получить работу, для чего нужно было закончить диссертацию, добившись учёной степени, и не умереть.

В 1965 году, согласно вердикту врачей, Стивена Хокинга ждали похороны. Молодой учёный заменил их на свадьбу, на которую пришёл своими ногами, пусть и опираясь на трость. Он не мог победить свою болезнь, но дрался с ней отчаянно. В 1967 году она заставила его взять костыли, Хокинг ответил ей рождением первенца. Он был уже прикован к инвалидной коляске, но у них с Джейн родились дочь и ещё один сын.

Стивен Хокинг путешествовал по всему миру, работал с учёными разных стран. Его научные работы поражали так же, как его мужество. В 1973 году Хокинг приехал в СССР, где обсуждал проблемы чёрных дыр с ведущими советскими специалистами в этой области Яковом Зельдовичем и Алексеем Старобинским.

Синтезатор вместо голоса.

В начале 1980-х годов профессор Хокинг и профессор Джим Хартл предложили модель Вселенной, которая не имеет космических границ и времени. Именно эта модель и описывается в ставшей мировым бестселлером (продано 25 миллионов экземпляров по всему миру) «Краткой истории времени».

Однажды на встрече Королевского сообщества Хокинг прервал лекцию известного астрофизика Фреда Хойла, чтобы указать ему на ошибку в ответе, до того как задача была решена. Когда профессор спросил, каким образом Хокинг заметил ошибку, он сказал: «Просто я уже решил задачу в уме».

Мир признал его гением, но и это признание не могло вернуть ему здоровья. В 1985 году его подкосило воспаление лёгких — болезнь, которая часто становится смертельной при диагнозе Хокинга. Учёный выкарабкался и на этот раз, но из-за проведённой операции навсегда лишился возможности говорить.

«Я поднимал бровь, когда кто-то показывал мне подряд карточки с алфавитом. Это было очень медленно. Я не мог вести беседу и, конечно же, не мог написать научную работу, — вспоминал Хокинг. — К счастью, у меня всё ещё достаточно сил в руке, чтобы нажимать и отпускать маленький выключатель. Этот выключатель соединён с компьютером, на экране которого всё время движется курсор. Он помогает мне выбирать слова из списка, возникающего на экране. Слова, которые я уже выбрал, отображаются в верхней части экрана. Когда я построил фразу полностью, я посылаю её в звуковой синтезатор. Синтезатор, которым я пользуюсь, довольно старый, ему 13 лет. Но я очень привязался к нему».

Как Хокинг проиграл подписку на «Пентхаус».

С годами болезнь оставляла Стивену Хокингу всё меньше возможностей. В последние годы подвижность осталась лишь в мимической мышце щеки, напротив которой закреплён датчик. С его помощью физик управляет компьютером, позволяющим ему общаться с окружающими. После операции в 1985-м и потери речи у Хокинга постепенно ухудшились отношения с супругой. В 1990 году, после четверти века совместной жизни, они стали жить раздельно, а затем развелись. И в 1995 году учёный… женился на своей сиделке. Брак с Элайн Мэсон продлился 11 лет, после чего физик разошёлся и с этой своей пассией.

«А похоже, этот парень парализован только сверху», — с некоторой завистью стали писать о личной жизни Хокинга вполне здоровые мужчины, не имеющие успеха у дам.

Ещё в 1974 году Стивен Хокинг и его коллега Кип Торн сошлись в споре природы объекта Лебедь X-1 и природы его излучения. Хокинг был уверен, что объект не является чёрной дырой, Торн был уверен в обратном. В 1990 году Хокинг признал, что был не прав и вручил Торну его выигрыш — годовую подписку на мужской журнал «Пентхаус».

Для Хокинга, лауреата всех мыслимых и немыслимых наград (за исключением, пожалуй, Нобелевской премии), подобное отношение к науке совершенно нормально.

Модный и неверующий.

Он, пожалуй, самый модный учёный в мире. Прикованный к креслу человек, лишённый речи, согласно опросам английских журналистов, входит в число самых уважаемых людей среди британской молодёжи наряду со спортсменами и звёздами музыки. Его регулярно упоминают в книгах, фильмах и даже мультфильмах. В «Симпсонах» и «Футураме» он сам озвучивал свой мультипликационный образ.

Серьёзные научные работы Хокинг перемежает с научно-популярными книгами и фильмами. В 2010 году Стивен Хокинг выпустил книгу «Великий замысел», где описывает гипотезу, согласно которой существование Бога не необходимо для объяснения происхождения и механизмов Вселенной.

Хокинг — не воинствующий, но определённо самый влиятельный атеист современности. Первая жена уже после развода признавалась, что так и не смогла смириться с этими взглядами Стивена. Но спорить с Хокингом в данном случае несерьёзно — учёный знает о Вселенной столько, что единственным достойным оппонентом в дискуссии по данному вопросу для него может стать только сам Господь. «Главный враг знания — не невежество, а иллюзия знания», — замечает Хокинг.

В апреле 2007 года Стивен Хокинг снова заставил молодых и здоровых людей чесать в затылке, побывав в состоянии невесомости, совершив полёт на специальном самолёте-лаборатории, позволяющем на несколько секунд создавать это состояние в условиях земного притяжения.