- Энциклопедия

- Разное

- Свойства воды

Вода – это жизнь. Где нет воды, там нет жизни. Например, в пустыне нет воды, и там почти не растут растения и не живут животные. Караваны в пустынях не смогли бы выжить там без воды. Выходит, она играет очень важную роль в нашей жизни.

Вода окружает нас всюду – она есть и в почве, и в растениях, и в пище. Снег, дождь, град, туман, облака, роса – все состоит из воды.

Вода есть даже в нас самих: ведь человек состоит из нее на 70%. Она находится в клетках нашего тела и в нашей крови. В течение дня нам хочется пить, потому что вода помогает поддерживать жизнь в нашем организме. За день человек расходует примерно 10 стаканов воды, и для поддержания жизнедеятельности ему необходимо восполнять ее запасы в организме. Казалось бы, выпить 10 стаканов воды в течение дня – не такая уж простая задача. Но ведь вода содержится и в пище, которую мы употребляем – в овощах, хлебе и мясе.

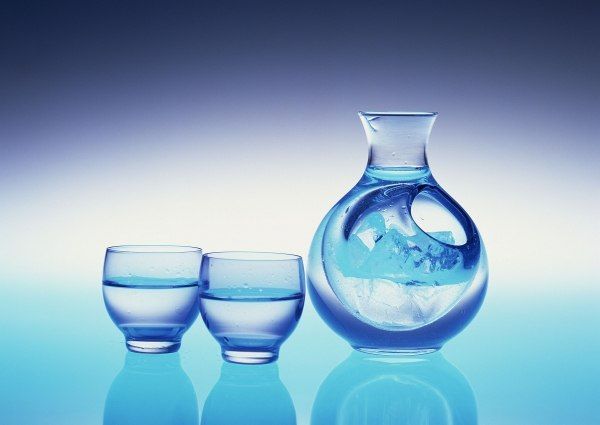

Вода обладает уникальными свойствами, например, у нее нет формы. Мы не можем из нее что-то слепить или подержать ее пальцами. Она приобретает форму сосуда, в котором находится, например форму стакана, чашки или даже наполненной ванны.

Кроме этого, вода текуча. Вода течет, когда мы наливаем ее в кружку или переливаем из кружки в стакан. Если наклонить наполненный стакан с водой, вода будет стекать по его стенкам. Капли воды на ровной поверхности тоже будут растекаться.

А еще вода прозрачна: если поместить чайную ложку в кружку с водой, она будет хорошо видна. А если, к примеру, поместить ложку в стакан молока, то ее уже не будет видно.

В одной поговорке говорится, что вода сладкая. Мы говорим так, когда нам очень хочется пить. Однако в реальности вода не обладает вкусом. Это можно легко проверить, сравнив вкус воды со вкусом яблок или хлеба, например.

А еще, в воде растворяются вещества. Когда добавляют в стакан воды ложку сахара, он начинает растворяться. В воде растворяют различные вещества, которые потом используют в качестве напитков или для лечения ран. И стиральный порошок растворяют в теплой воде, чтобы потом стирать в ней одежду. Вода – хороший растворитель не только для твердых веществ, но и для газов и жидкостей.

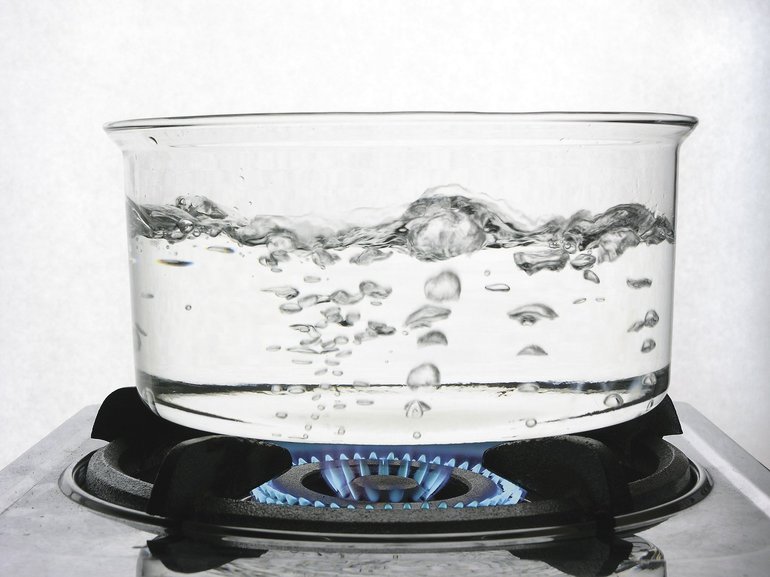

Очень важное свойство воды – изменение ее состояния. При нагревании воды она превращается в пар, а при охлаждении – в лед. Так от кипящей в чайнике воды идет пар, а зимой на улице вокруг нас — снег и лед.

Если взглянуть на нашу планету, то можно увидеть, что большую часть ее поверхности, примерно три четверти, составляет вода. Однако это вовсе не означает, что воду не нужно экономить и беречь. Существует много заводов и фабрик, которые загрязняют озера, реки и моря. От загрязнений страдают и растения, и животные, и люди. Пресная вода может исчезнуть, если ее не беречь. А что произойдет, если на планете не станет пресной воды? Ведь тогда все живое на планете погибнет.

Поэтому и нам следует каждый день помнить о том, что вода – это бесценное сокровище, которое нужно беречь и экономить. Например, когда чистите зубы, не нужно оставлять кран открытым. Ведь каждый раз, когда мы чистим зубы и оставляем кран открытым, мы теряем 4 литра воды. Мы же чистим зубы 2 раза в день, а значит, теряем 8 литров воды в день.

Вода очень полезна для людей. С ее помощью работают электростанции, по ней лодки и корабли перевозят и людей, и грузы. В воде живет множество рыб и моллюсков. Без воды люди не смогли бы сделать ни книги, ни одежду, ни сладости. Люди смогли применять воду везде, узнав о ее удивительных свойствах.

Доклад Свойства воды

Вода играет огромную роль в жизни любого живого существа. Отличить воду от любой другой жидкости помогут ее свойства. Основными свойствами являются:

Прозрачность и бесцветность

Вода состоит из особых веществ — кислорода и водорода. Эти вещества не имеют цвета, а значит, человек не может их увидеть, поэтому причиной прозрачности воды являются её составляющие.

Текучесть

Вода является жидкостью.

Жидкость текуча, то есть она не имеет собственную форму, но зато может принимать вид сосуда, в который она налита. Текучесть свойство жидкости менять свою форму под действием внешних сил, но при этом, не разделяясь на частички. Когда мы наливаем воду в стакан, она льется единой струей, а не кусками.

Отсутствие запаха и вкуса

Озера, реки, моря, океаны могут пахнуть, но испускает аромат не сама жидкость, а определённые компоненты, содержащиеся в воде, которые в свою очередь имеют запах. Но человек не может почувствовать ни вкус, ни запах обычной чистой воды, которая есть в каждом доме.

Растворитель

Вода это универсальный и самый распространенный растворитель на планете Земля. Некоторые вещества вода растворяет, такие вещества называются гидрофильными (соли, сахара, аминокислоты, спирты). А некоторые она не может растворить, такие вещества называются гидрофобными (липиды, жиры, нерастворимые соли, некоторые белки). Например, масло не растворяется в воде, а сахар растворяется, значит, масло — гидрофобное, а сахар — гидрофильное вещества.

Принимает три агрегатных состояния

Жидкое состояние. Это состояние вода принимает, когда ее температура не ниже 0 и не выше 100 градусов по Цельсию при нормальном атмосферном давлении.

Лёд – это твердое состояние воды. Жидкость превращается в лед, когда температура опускается ниже 0 градусов по Цельсию. Вода при процессе этом расширяется, становится больше.

Газообразное состояние. Когда температура достигает отметки выше 100 градусов по Цельсию, тогда вода превращается в водяной пар. Можно увидеть это состояние, посмотрев на облака или туман на улице.

Вариант №3

Самой главной основой для жизни всех живых организмов и человека на Земле является вода. Если на планете нет воды, значит, там нет и жизни. Вода в нашей повседневной жизни встречается достаточно часто, она имеет много полезных свойств. Ни для кого не является секретом, что вода может находиться сразу в трех видах: твердом, жидком и газообразном. Комнатная температура влияет на состояние воды так, что она всегда будет жидкой. При минусовой температуре воде свойственно замерзание. Она быстро превратится в лед и станет намного тверже, чем была до этого. Если же обычную воду налить в кастрюлю и поставить на огонь, после ее кипения начнет образовываться пар, и вся вода может выкипеть. Среди всех главных свойств воды принято выделять следующие. Вода всегда имеет прозрачный цвет, она не имеет запаха, вода всегда текучая и бесцветная. Кроме этого вода обладает удивительной способностью принимать самую разнообразную форму. Если налить воду в квадратную посуду, вода приобретет форму квадрата, и это только один пример. С помощью воды можно отлично растворять различные вещества. Кроме замерзания и испарения вода еще может сжиматься и разжиматься. Как бы там ни было, все свойства, которыми обладает вода, зависят только от ее структуры.

Итак, вода растворяет вещества. В водеможет быть много разных солей. Чем больше в составе воды будет соли, тем солонее она будет. Если соли будет слишком много, то данная вода станет тяжелее. Тяжелая вода быстрее опускается на дно. Многие микроорганизмы, живущие в морях и океанах, давно приспособились к такой воде, в другой они не выживут.

Значимая роль отводится круговороту воды в природе. В одном месте она испаряется, а в другом возникает. При испарении обычная вода не имеет токсичных добавок. Этого нельзя сказать о других видах жидкости. Почти все эфиры и спирты считаются токсичными. На всякий случай специалисты ставят на воду разнообразные фильтры для воды, чтобы на всякий случай очистить ее еще лучше. Вода в природе отличная жидкость, которая может поглощать много тепла. Это защищает не только человека, но и многих животных от перегрева на солнце.

У воды есть еще множество других свойств. К примеру, вода хорошо отмывает грязь. Если в нее добавить краситель, она поменяет свой цвет. Наверное, самое главное, что нужно запомнить – нельзя использовать воду в тех местах, где проходит электричество. Если вода нечаянно попадет на электроприбор, случится замыкание и начнется пожар. Вода и электричество – это очень опасно.

Вариант №4 Доклад-сообщение Свойства воды

В природе существует особое и уникальное вещество, без которого не сможет существовать не одно живое существо – это вода.

И когда ученые разных стран осуществляют поиск жизни на других планетах они, ищут сначала именно воду. И если она вдруг там существует, то эта планета причисляется к планете земного типа, на которой может быть жизнь.

Вода по своему составу не имеет не цвета не запаха, формы. В жидком состоянии текучая. При нагревании она расширяется при охлаждении сжимается. Отличительной особенностью этого вещества является, что при охлаждении она снова расширяется. Это можно наблюдать зимой, когда сильные морозы вода в водопроводе замерзает и расширяется, поэтому лопаются водопроводные трубы.

Благодаря тому, что вода плохо проводит тепло, долго нагревается и охлаждается, обитателям различных водоемов не угрожает не сильное перегревание летом не сильное переохлаждение зимой. Лед образовываясь зимой, предохраняет водоемы от сильного переохлаждения.

Также вода хороший растворитель. В окружающей среде нет абсолютно чистой воды без посторонних веществ. Если например рассмотреть дождевую каплю которая на первый взгляд кажется кристально чистой обнаружится огромное количество различных органических веществ.

Так в морях, озерах реках, океанах растворено огромное количество различных веществ. Так в морях растворено всем известное нам вещество это соль. Ее можно определить по вкусовым качествам морской воды. Поэтому вода в морях считается раствором. Употреблять в пищу такую воду нельзя.

Известен очень интересный факт, человек состоит на 90 процентов из воды. Из этого можно сделать уникальный вывод – все, что влияет на человека так или иначе влияет и на воду. Другими словами, вода основа нашего физического существования, подвержена влиянию из вне, это определенно влияет и на наше духовное состояние. Самый интересный факт, что без еды человек может просуществовать несколько недель, а без воды всего несколько дней.

Вариант №5

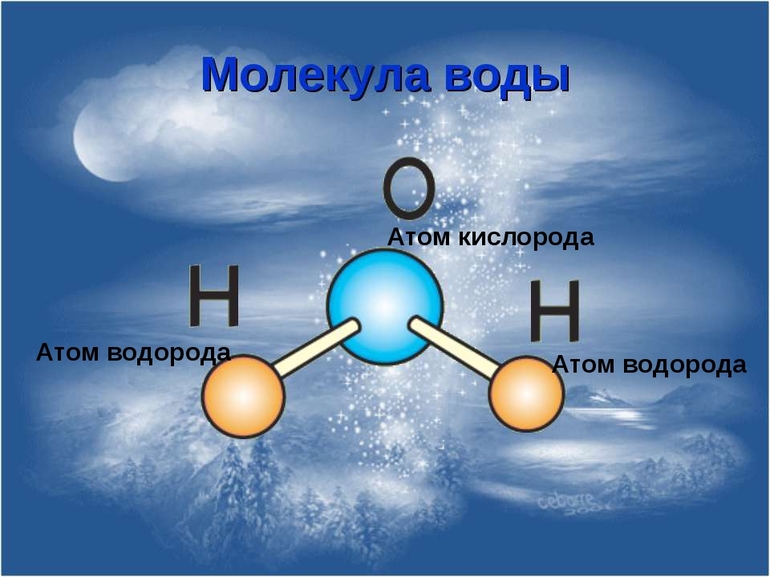

Вода — наиболее известное, самое распространенное и узнаваемое вещество на нашей планете. Она имеет множество названий: оксид водорода, гидроксид водорода и другие. Значит, что вода имеет в своем составе один атом кислорода и два атома водорода, а именно 88,91% водорода и 11,19 % кислорода. При комнатных условиях вода находится в жидком состоянии, не имеет цвета, вкуса и запаха.

На нашей планете вода представлена во всех трех состояниях: жидком (реки, озера, моря, океаны), твердом (лед) и газообразном (пар). Почти 70% Земли покрыто водой. Основная ее часть 97 % приходится на долю соленой воды (моря и океаны), значит, она не пригодна для употребления живыми организмами.

Вода – является главным источником жизни для всех живых существ на нашей планете Земля. Всем известно, что человек на 80% состоит именно из этой «универсальной жидкости». Большинство ученых в наше время приходят к мнению, что жизнь на планете Земля зародилась нигде-то, а именно в воде.

Главные качество воды:

- не имеет запаха;

- прозрачная;

- текучая;

- бесцветная;

- замерзает (при 0 ° С);

- испаряется (при 100 °С);

- расширяется (при нагревании) и сжимается (при охлаждении);

- способна принять любую форму, в которую ее налить;

- растворяет многие вещества.

Виды воды:

Помимо своих основных видов (жидкого, твердого и газообразного состояния), вода также может быть мягкой и жесткой это обусловлено наличием в воде так5их веществ как кальций (Са) и натрий (Na).

Любая вода имеет в своем составе множество примесей, например, растворенные соли и в зависимости от этого вода, может быть:

- минеральной (имеет самое большое содержание соли — 35%);

- солоноватая (среднее содержание соли — от 2% до 25%);

- пресная (минимальное содержание соли, которое не превышает 0,1%).

Напрямую от состава растворенных солей в воде будет изменяться ее вкус. Сульфат-магния дает горький привкус, соли железа вкус ржавчины, а хлористый натрий (соль) дает солоноватый вкус, вода, имеющая в своем составе множество органических веществ – сладкая, а свежесть воде придает угольная кислота.

Цвет воды зависит от ее состава и примесей в ней. Вода в своем нормальном состоянии не имеет цвета, но если в ее составе появляются гуминовые кислоты, она становится желтой, ярко-зеленой – наличие сероводорода.

Прозрачность, так же как и цвет обусловлена наличием в составе воды механических примесей и растворенных в ней минеральных веществ, в зависимости от этого вода может быть:

- мутной;

- сильно мутной;

- опалесцирующей;

- слегка мутной;

- прозрачной;

- слабо опалесцирующей.

Практически всегда у воды полностью отсутствует запах. Но если он есть, это свидетельствует о наличие в воде органических веществ, которые подверглись процессу разложения и вызывают гниение. Запах воды может быть: плесневелым, болотным, гнилостным, сероводородный и без запаха.

Вода, находящаяся в жидком состоянии течет. Вода течет отовсюду, из бутылки, из крана, течет в реках и ручьях. Свойство воды принимать форму любого сосуда, куда она налита – текучесть.

Также всем известно, что вода очень хорошо проводит электрический ток. Значит, нельзя ни в коем случае допускать попадания воды на любой электрический прибор. Принимать ванну с подключенным к зарядке телефоном категорический запрещено! В то время, как электрический ток течет по проводам и встречается с водой происходит сильнейший удар током и это смертельно опасно для человека!

При замерзании вода сжимается, но увеличивается в объеме. По этой причине не рекомендуется замораживать бутылки с водой в морозилке. При замерзании вода разрывает бутылку большим объемом, пластиковая бутылка при этом лопается, а стеклянная трескается и разбивается.

Мы подробно рассказали о каждом свойстве воды, но это только самые основные свойства этой удивительной жидкости, с которыми мы сталкиваемся каждый день.

2, 3, 5, 6 класс, окружающий мир кратко по химии

Свойства воды

Популярные темы сообщений

- Планеты гиганты

Газовые планеты Солнечной системы и их особенности. Планеты в Солнечной системе возникли не сразу. Это случилось примерно 4,6 миллиарда лет назад. Они сформировались из материала, оставшегося после рождения Солнца:

- Дерево Ель

Ель. Что может быть обычнее, чем это дерево? Оно встречается везде: по дороге в детский сад, в школу, на работу, на любой прогулке, а у кого-то даже растёт на дачном участке. Люди настолько привыкли к этому дереву, что даже не замечают его,

- Дерево Секвойя

Гигантская сосна или секвойя является самым большим деревом на планете. Стоя рядом с этим деревом, человек кажется карликом. В древние времена секвойи были распространены во всём северном полушарии.

- Маргаритка

Маргаритка – многолетнее растение, представитель семейства Астровые. Всего в данный род входит 14 видов, из которых лишь немногие растут на территории России (западная часть и Кавказ); большинство видов произрастает на территории Европы,

- Творчество Габриэля Маркеса

Гарсиа Маркес Габриэль – известный журналист, писатель, политический деятель. Гарсия является отцовской фамилией, Маркес, в свою очередь – это материнская фамилия. Родился в 1927 году в Колумбии.

Вода — самая удивительная и загадочная из всех жидкостей, существующих на Земле.

Учёные на протяжении многих столетий продолжают проводить исследования, находя новые интересные факты. Каждый человек знает, что без воды жизнь невозможна.

Вода участвует в формировании климата, для многих живых организмов является средой обитания. Её важность сложно недооценить. Не случайно, нашу планету называют голубой, именно вода покрывает 71 % поверхности земного шара.

В статье мы собрали самую важную и интересную информацию про воду: гипотезы её появления на нашей планете, особенности строения молекулы, агрегатные состояния, уникальные и необычные свойства.

Содержание

- Что такое вода, химические названия

- Агрегатные состояния

- Строение в различных агрегатных состояниях

- Свойства

- Круговорот воды в природе

- Происхождение воды на планете

- Наука о воде

- Значение на Земле

- Применение

- Сколько жидкости в теле человека

- Основные функции

- Польза чистой питьевой воды

- Сколько нужно пить воды в день

- Процентное содержание в органах

- Признаки обезвоживания

- Виды

- Запасы пресной воды

- Показатели качества

- 25 интересных фактов

- Заключение

Что такое вода, химические названия

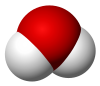

Вода — это бинарное неорганическое соединение, химическая формула H2O.

При нормальных условиях представляет собой прозрачную, бесцветную жидкость, которая не имеет вкуса и запаха, текуча (принимает форму сосуда).

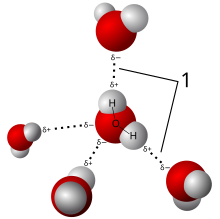

Молекула воды состоит из одного атома кислорода и двух атомов водорода, которые соединены между собой ковалентной связью. Никакие другие элементы таблицы Менделеева при соединении не образуют жидкости. Рассмотрим строение молекулы H2O на изображении.

Вода имеет несколько химических названий:

- оксид водорода;

- гидроксид водорода;

- монооксид дигидрогена;

- дигидромонооксид;

- гидроксильная кислота.

Агрегатные состояния

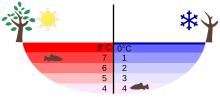

Из всех веществ, существующих на Земле, только вода может иметь три принципиально разных агрегатных состояния: жидкое, газообразное и твердое. Благодаря трём агрегатным состояниям происходит круговорот воды в природе и жизнь на Земле. Рассмотрим подробнее каждое агрегатное состояние.

- Жидкое (вода). В нормальных условиях вода является жидкостью. Образует мировой океан, реки, ручьи и т.д.

- Газообразное (водяной пар) — это бесцветный газ, не имеет вкуса и запаха. Испаряется с поверхности океанов, рек, болот, почвы, растений и поступает в воздух или образуется путём кипения жидкой воды или сублимации из льда. Сублимация — переход вещества из твёрдого состояния сразу в газообразное, минуя стадию плавления (перехода в жидкое состояние).

- Твердое (лёд). При температуре от нуля и ниже вода превращается в лёд. В холодное время года он сковывает реки и лужи, выпадает в виде осадков: снежинок, града, инея, образует ледяные облака. Встречается в виде ледников и айсбергов.

Строение в различных агрегатных состояниях

Жидкая вода, лёд и водяной пар имеют один и тот же состав, но разные состояния.

Рассмотрим строение молекулы на изображении.

Многочисленные исследования ученых подтверждают, что по структуре вода и лед близки друг к другу. Структура льда – это решетчатый каркас. Структура воды зависит от содержания разных веществ, которые в ней растворяются, а также от нерастворимых соединений и некоторых других факторов.

В воде возникают структуры, которые стали называть «кластерами» — группа атомов или молекул, которые представляют собой единую структуру, но внутри имеют свои индивидуальные особенности.

При температуре близкой к точке замерзания, молекулы жидкой воды собираются в небольшие группы, практически так, как в кристаллах. При температуре близкой к точке кипения они располагаются более свободно.

Свойства

Вода — уникальный природный компонент, который обладает рядом свойств. Рассмотрим основные:

- не имеет цвета, запаха и вкуса;

- распространенный растворитель;

- обладает высоким поверхностным натяжением, уступая в этом только ртути;

- имеет большую теплоту испарения (используется для терморегуляции);

- чистая вода — хороший изолятор;

- обладает большой теплоёмкостью (увеличение тепловой энергии вызывает лишь сравнительно небольшое повышение ее температуры);

- плотность в разных диапазонах температур меняется неодинаково.

Существуют необычные свойства. Например, в твердом виде вода легче, чем в жидком. Лёд не тонет в воде. В твёрдом состоянии частички воды располагаются по порядку, между ними остается много свободного пространства. Когда лёд тает, активность частичек повышается, свободное пространство заполняется. Жидкая форма становится более тяжелой, нежели твердая.

Такая уникальная способность даёт возможность любому водоёму не замерзать по всей глубине. Даже при самом сильном морозе температура воды у дна не опускается ниже +4 ᵒС. Все живые существа (рыбы и другие) могут спокойно пережить самую суровую зиму подо льдом.

Когда лёд тает, плотность увеличивается, и становится максимальной при температуре +4 ᵒС. В диапазоне от +4 ᵒС до +40 ᵒС плотность снижается, потом снова увеличивается. При понижении температуры ниже +4 ᵒС плотность уменьшается, т.е. при замерзании вода расширяется.

Горячая вода замерзает быстрее, чем холодная. Это связано с большей скоростью испарения и излучения тепла.

Теплоемкость и некоторые другие физические свойства воды тоже зависят от температуры неодинаково. Другие виды жидкостей не имеют таких особенностей – чтобы какой-то один параметр менялся по-разному на разных порогах температуры.

Круговорот воды в природе

Вода образует водную оболочку нашей планеты – гидросферу.

Её делят на Мировой океан, континентальные поверхностные воды и ледники, а также подземные водоёмы. Переходы H2O из одних частей гидросферы в другие составляют сложный круговорот воды на Земле

Круговорот воды в природе — это непрерывное движение воды в гидросфере Земли. В процессе этого обмена водная масса меняет агрегатное состояние: из жидкой или твердой превращается в газообразную и обратно.

Рассмотрим на примере.

- С поверхности океанов, морей, рек и суши вода в виде пара поднимается вверх.

- Высоко над землей он охлаждается и образует множество водяных капелек и льдинок. Из них образуются облака.

- В виде осадков вода возвращается на Землю.

Происхождение воды на планете

Возникновение воды на нашей планете является предметом научных споров. Существует 2 основные гипотезы:

- Космическое происхождение. Часть учёных считают, что вода появилась вследствие падающих метеоритов, астероидов, которые содержали воду.

- Земное происхождение. Другие учёные считают, что вода образовалась на Земле во время формирования, а не занесена с космоса.

Наука о воде

Изучением природных вод, явлений и процессов занимается наука Гидрология.

Первые упоминания о гидрологии появились на заре истории человечества около 6000 лет назад.

Начало гидрологических наблюдений в России относится к XV–XVI вв.: в записях русских летописцев сохранились сведения о свойствах воды, наводнениях, паводках, замерзании.

Значение на Земле

Без воздуха человек может прожить несколько секунд, без еды – несколько месяцев, без воды – максимум несколько суток. Снижение содержания воды в организме всего лишь на 2% может вызвать сильную слабость. При нехватке 8% уже может возникнуть серьезное недомогание, а при 12% – смерть.

Каждая клетка живого организма состоит из жидкости и нуждается в регулярном пополнении. Без воды не проживут ни люди, ни растения, ни животные.

Вода формирует климат, участвует в круговороте воды в природе, для многих живых организмов является средой обитания.

Применение

Все люди на планете прекрасно знают, что жизнь без воды невозможна. Любое начало жизни изначально зарождается в воде.

Человек применяет воду:

- для поддержании жизни (приготовления пищи, обеспечения организма водой);

- для бытовых нужд (гигиены, уборки и т. д);

- в сельском хозяйстве и животноводстве;

- промышленности (используется при производстве продуктов питания, чугуна, стали, резины и т. д);

- медицине;

- химии (в качестве реагента для химических реакций, опытов, исследований);

- рыболовстве;

- для транспортировки людей и грузов;

- для спорта;

- в земледелии;

- для пожаротушения;

- служит источником энергии (электростанции).

Сколько жидкости в теле человека

Эмбрион человека состоит из жидкости не менее, чем на 97%. Когда ребенок рождается, вода составляет около 80% его тела. В первые несколько суток после рождения этот показатель существенно снижается.

В дальнейшем содержание воды в организме человека постоянно уменьшается. В пожилом возрасте в теле человека доля воды не превышает 50-60%.

Как определить, сколько воды в теле человека?

Массу тела необходимо разделить на 3 и умножить на 2.

Стоит отметить, что расчет считается приблизительным (может отличаться на 5-10%) Так как количество воды зависит от возраста, пола, физической активности, состояния здоровья.

Основные функции

Вода необходима каждому живому существу. Каждый живой организм состоит из клеток. Ключевую роль выполняет вода. Она составляет около 70 процентов от её массы. Рассмотрим кратко основные функции.

- Растворитель. Большинство химических реакций протекают только в водной среде.

- Транспортная функция. Переносит питательные вещества из одной части в другую.

- Функция регенерации. С помощью воды удаляются ненужные продукты жизнедеятельности.

- Регулирует терморегуляцию. Защищает организм от перегрева и обеспечивает равномерное распределение тепла по организму.

- Все обменные процессы в организме регулируются водой.

Польза чистой питьевой воды

Врачи, диетологи и другие специалисты часто совершают ошибку, когда слишком много внимания уделяют разным продуктам питания и забывают про воду. Любые вещества, даже самые питательные и полезные, могут оказаться совершенно неэффективными, если нет растворителя, способного доставить их в нужные части тела. На Земле есть только один простой, надежный и распространенный растворитель – вода.

Вода участвует абсолютно во всех обменных процессах. И чтобы они протекали нормально, необходимо пить достаточное количество чистой воды. Именно воды, не чая, не напитков. Содержание разных примесей, консервантов и прочих веществ существенно меняют структуру, нормальное молекулярное состояние воды.

Изначально природой заложено употреблять чистую воду. Когда в организм вносится некая смесь, то пищеварительной системе приходится прикладывать много усилий, растрачивать много энергии, чтобы отделить все лишнее и получить воду. Кроме этого, высокое содержание сахара неизбежно провоцирует нарушение нормального обмена веществ.

Питьевая вода должна быть чистая, свежая, качественная, «живая». Т.е. это должна быть натуральная природная вода, которая при попадании в организм легко проникает во все клетки, служит эффективным растворителем. Она быстро доставляет все питательные вещества к тканям и органам.

Сколько нужно пить воды в день

Рекомендуется употреблять чистую воду без примесей 30-40 мл на 1 кг веса.

Средние показатели:

для женщины: 1,5 – 2 литра ежедневно;

для мужчины: 2,5 – 5 литров ежедневно.

Количество рекомендуемой нормы зависит от физической активности, климата и веса.

Процентное содержание в органах

Вода в теле человека находится в разных субстанциях и никогда не смешивается в единое целое.

Жидкости больше в тех клетках, в которых обмен веществ протекает более интенсивно. Рассмотрим таблицу № 1.

Таблица № 1. Процент содержания в органах человека

| Органы | Процент содержания |

| Мозг | 90 |

| Лёгкие | 86 |

| Печень | 86 |

| Кровь | 83 |

| Яйцеклетки | 90 |

| Кости | 72 |

| Кожа | 72 |

| Сердце | 75 |

| Желудок | 75 |

| Селезёнка | 77 |

| Почки | 83 |

| Мышцы | 75 |

Признаки обезвоживания

Если содержание воды резко меняется в одну или другую сторону, то это сразу сказывается на общем состоянии здоровья. Чрезмерное количество воды организм переносит намного легче, чем ее нехватку. Рассмотрим основные симптомы проявления нехватки воды в организме человека.

- Жажда – первый сигнал нехватки жидкости в организме.

- У человека возникают твердые каловые массы и запоры.

- Появляется усталость и слабость.

- Возникают головные боли и головокружения.

- Кожа становится сухой.

- Состояние может сопровождаться сильным упадком настроения (вплоть до тяжелой депрессии).

При длительном сохранении такого состояния могут возникнуть проблемы:

- с артериальным давлением;

- нарушением пищеварения;

- заболеваниями органов ЖКТ;

- может появиться диабет, ожирение (или наоборот – истощение, дистрофия);

- появляются зрительные и слуховые галлюцинации (при потери воды 10%);

- сильное обезвоживание может привести к смерти.

Виды

Проходя гидрологический цикл, вода может дополняться химическими элементами: ионами, растворенными газами, микроэлементами и т.д.

Воду квалифицируют по следующим признакам:

- по наличию и составу изотопов в молекуле;

- по степени растворения частиц солей и других примесей;

- по источнику;

- по взаимодействию с другими элементами и компонентами;

- по воздействию человека;

- по индивидуальным параметрам.

Рассмотрим некоторые виды на рисунке.

Запасы пресной воды

Несмотря на то, что Земля более, чем на 70% покрыта водой, лишь 1% является пресной (её солёность не превышает 0,5 ‰).

Более 2/3 запасов пресной воды на Земле хранится в ледниках. Крупнейшим водоёмом пресной воды считается озеро Байкал в России.

Показатели качества

В воде, которая течет из кранов современных городских квартир, могут содержаться вредные примеси. Такую воду стали называть словом «техногенная». В ней содержатся металлы, песок, глина, хлор и много чего еще.

Современные нормы очистки водопроводной питьевой воды предполагают использование хлорсодержащих реагентов, которые избавляют воду от инфекций. В дополнение рекомендуется использовать дополнительные методы очистки. Например, фильтры.

Большой популярностью в развитых странах пользуется бутилированная питьевая вода. Она является экологически чистым продуктом. Реализуется в гигиенически чистой ёмкости и соответствует всем установленным требованиям.

Ученые постоянно исследуют оксид водорода, находя интересные факты.

- Лёд не тонет в воде. Дело в том, что плотность льда меньше чем, воды в жидком состоянии. Поэтому морские обитатели продолжают жизнедеятельность. Другие вещества увеличивают плотность при замерзании.

- Большинство загрязнений вымораживаются при образовании льда.

- Более 2/3 запасов пресной воды на Земле хранится в ледниках.

- Вёдра для воды изготавливают в форме конуса для того, чтобы их не разорвало при случайном замерзании воды.

- Теплоёмкость и некоторые другие физические свойства воды зависят от температуры не одинаково.

- Жидкая вода регулирует температуру Земли, водяной пар — влажность воздуха.

- Снег способен отражать лучи света на 75%, а вода только на 5%, поэтому снежные ночи такие светлые.

- В Антарктиде есть озеро с водой, в 11 раз солёнее морской. В нем настолько соленая вода, что не замерзает даже при — 50 С.

- Горячая вода имеет способность замерзать быстрее, чем холодная. Этот факт легко проверить самостоятельно.

- Лёд встречается на полюсах Луны, а также на полюсах Марса и Меркурия.

- В Антарктике находится самый холодный лёд, а вот самым теплым льдом считается Альпийский, так как его температура составляет 0 градусов по Цельсию.

- Температура кипения воды не всегда составляет 100 градусов по Цельсию. Показатель зависит от атмосферного давления. Например, на Эльбрусе — самой высокой вершине Европы (5642 м), — вода закипит при 80,8 °С.

- Примерно на каждые 100 метров вглубь к центру Земли температура кипения увеличивается на 3°C.

- Озеро Байкал — самое большое пресное озеро в мире.

- Для производства 1 тонны стали требуется 300 тонн воды.

- Учёные считают, что мировой океан изучен только на 2-7%.

- На 1 кг тела коровы приходится 600 грамм жидкости.

- В теле рыбы 70-80 процентов.

- В медузе больше 95 процентов.

- Растения на 50-90 процентов состоят из жидкости.

- Вода участвует в фотосинтезе растений.

- Бегемот употребляет около 250 литров воды в сутки.

- Древесное растение Эвкалипт в сутки поглощает из почвы и испаряет 320 л влаги.

- Верблюд способен выпить больше 100 литров воды менее, чем за 15 минут.

- Скалистая белка может жить без воды до 100 дней.

Заключение

Вода – удивительное вещество, обладающее химическими и физическими свойствами. Она формирует климат на планете, для многих живых организмов является средой обитания, необходима для фотосинтеза растений и жизнедеятельности всех живых организмов.

Свойства воды

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 962.

Обновлено 30 Марта, 2021

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 962.

Обновлено 30 Марта, 2021

Вода – это основа жизни на Земле, без живительной влаги ни одно живое существо в природе не способно долго прожить. Свойства воды очень разнообразны, благодаря чему она смогла найти самое широкое применение на нашей планете. Давайте познакомимся с самыми важными качествами воды.

Опыт работы преподавателем — более 48 лет.

Состояния воды

Все привыкли, что вода – это прозрачная жидкость, без цвета и вкуса. Однако она может находиться в трех состояниях:

- жидком;

- твердом (лед);

- газообразном (водяные пары).

Состояние воды напрямую зависит от температуры. Если на улице тепло, то вода – жидкая, при сильном холоде (меньше 0С) вода замерзает и превращается в лед, а при закипании (больше 100С) она начинает испаряться в воздух. Но в природе при любой погоде происходит испарение воды.

Способность воды менять свое состояние под воздействием температуры объясняет такой важный процесс как круговорот воды в природе.

Одно из важных свойств воды в жидком состоянии – способность растворять в себе многие вещества. В воде с легкостью растворяются различные кристаллы (соль, сахар), щелочь (мыло). А вот, скажем, с маслом или камнями ей никак не справиться.

Прозрачность воды

Степень прозрачности может быть самой разной. К примеру, в чистой горной речке можно увидеть дно с песком и камнями, в аквариуме можно наблюдать за разноцветными рыбками. И даже если заварить чай, то вода все равно сохранит свою прозрачность, и в чашке можно будет увидеть дно.

ТОП-4 статьи

которые читают вместе с этой

Но если в воде находится слишком много посторонних примесей, она становится мутной. Пробежав по песчаному дну мелкой речки или добавив в чай варенье или молоко, от былой прозрачности ничего не останется.

Это значит, что прозрачность воды напрямую зависит от ее чистоты.

Цвет и запах воды

Каков цвет чистой воды? Этот простой вопрос может многих поставить в тупик. Но на самом деле у воды совершенно нет никакого цвета – она бесцветна.

Но как же быть с морями и океанами, реками и озерами, ведь вода в них отливает всеми оттенками синего, голубого и зеленого. На самом деле чистая прозрачная вода просто отражает те цвета, которые ее окружают. Если зачерпнуть пригоршню лазурной морской воды, она окажется бесцветной.

Вода абсолютно нейтральна и в плане ароматов чистая вода ничем не пахнет.

Вода и электричество

Каждый ребенок должен знать, что там, где есть вода, не место электрическим приборам! Вода очень хорошо проводит ток, и при ее попадании в розетку или на включенный электроприбор может произойти несчастный случай – сильный удар током. В некоторых случаях это может даже привести к смерти.

Именно поэтому нужно быть очень осторожным и следить за тем, чтобы электроприборы находились как можно дальше от воды.

Текучесть воды

В жидком состоянии вода способна течь. Течет она в реках и ручьях, из-под крана или перевернутой вниз бутылки.

Способность воды принимать форму посуды, в которой она находится, называется текучестью. Независимо от того, куда она налита, будь то чашка, замысловатая узкая ваза или канистра, вода всегда идеально повторит контуры емкости.

При замерзании вода увеличивается в объеме. Об этом нужно помнить, прежде чем решить положить в морозильник бутылку с водой. Постепенно превращаясь в лед, вода способна разорвать сосуд: пластиковая бутылка лопнет, а стеклянная – разлетится на множество осколков.

Таблица “Свойства воды”

|

Свойства |

Жидкая |

Твердая |

Газообразная |

|

Цвет |

Бесцветная |

Лед не имеет цвета, снег белый |

Бесцветная |

|

Прозрачность |

Прозрачная |

Лед прозрачный, снег не прозрачный |

Прозрачная |

|

Запах |

Не имеет |

Не имеет |

Не имеет |

|

Вкус |

Не имеет |

Не имеет |

Не имеет |

|

Форма |

Растекается |

Лед имеет форму, снег – нет |

Не имеет формы |

|

Тем-ра кипения |

+100С |

– |

– |

|

Тем-ра замерзания |

0С |

Тает при 0С |

При охлаждении – вода |

Что мы узнали?

При изучении темы «Свойства воды» по программе 3 класса окружающего мира мы выяснили, какими основными свойствами обладает вода. Тщательное их изучение необходимо для улучшения и развития хозяйственной деятельности человека.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Александр Орехов

10/10

-

Галина Синяева

10/10

-

Елена Белоусова

10/10

-

Алексей Беляев

10/10

-

Антон Тетюков

10/10

-

Наира Абдурахманова

9/10

-

Саша Билей

8/10

-

Владислав Сунегин

9/10

-

Светлана Решетникова

9/10

-

Надежда Бойко

10/10

Оценка доклада

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 962.

А какая ваша оценка?

Вода — самое распространённое вещество на нашей планете. Вспомним её свойства.

При комнатной температуре вода жидкая. Она принимает форму сосуда, в котором находится.

Рис. (1). Вода принимает форму сосуда

Вода текучая, как и все жидкости. Поэтому на земле есть реки, ручьи и водопады, а в наш дом она может поступать по водопроводу.

Рис. (2). Вода текучая

Вода бесцветная и прозрачная, и мы хорошо видим обитателей водоёма или аквариума.

Рис.. (3). Вода бесцветная и прозрачная

Вода не имеет запаха и вкуса.

Вода растворяет многие вещества. Если в воду насыпать соль и перемешать, то соль как бы пропадает. Вода остаётся прозрачной, но становится солёной. Это происходит потому, что частицы соли перемешиваются с частицами воды.

Рис. (4). Вода — растворитель

Растворяются в воде и другие вещества: сахар, уксус, спирт.

Но известно много веществ, которые в воде не растворяются. Если смешать с водой песок, то вода станет мутной, а песок через некоторое время осядет на дне сосуда.

Рис. (5). Вода и песок

Не растворяется в воде мел и некоторые жидкости, например, растительное масло и бензин.

Для очистки воды от примесей твёрдых веществ используется фильтрование. Мутную воду пропускают через фильтр (специальную бумагу или ткань). На фильтре оседают твёрдые частицы, а вода становится чистой.

Рис. (6). Фильтрование

При нагревании вода расширяется, а при охлаждении сжимается.

Рис. (7). Сжатие воды при охлаждении

Источники:

Рис. 1. Вода принимает форму сосуда https://image.shutterstock.com/image-photo/water-splash-pitcher-into-glass-600w-158373875.jpg

Рис. 2. Вода текучая https://image.shutterstock.com/image-photo/water-tap-faucet-flow-bathroom-600w-1833087562.jpg

Рис. 3. Вода бесцветная и прозрачная https://www.shutterstock.com/ru/image-photo/goldfish-fishbowl-716133220

Рис. 4. Вода — растворитель https://www.shutterstock.com/ru/image-photo/pouring-sugar-into-saucepan-boiling-water-162244724

Рис. 5. Вода и песок https://www.shutterstock.com/ru/image-photo/science-experiment-heterogeneous-mixture-water-sand-1490431379

Рис. 6. Фильтрование © ЯКласс

Рис. 7. Сжатие воды при охлаждении © ЯКласс

For broader coverage of this topic, see Water.

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Names | ||

|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Water |

||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Oxidane |

||

| Other names

Hydrogen hydroxide (HH or HOH), hydrogen oxide, dihydrogen monoxide (DHMO) (systematic name[1]), dihydrogen oxide, hydric acid, hydrohydroxic acid, hydroxic acid, hydrol,[2] μ-oxido dihydrogen, κ1-hydroxyl hydrogen(0) |

||

| Identifiers | ||

|

CAS Number |

|

|

|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

|

|

Beilstein Reference |

3587155 | |

| ChEBI |

|

|

| ChEMBL |

|

|

| ChemSpider |

|

|

|

Gmelin Reference |

117 | |

|

PubChem CID |

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

|

| UNII |

|

|

|

InChI

|

||

|

SMILES

|

||

| Properties | ||

|

Chemical formula |

H 2O |

|

| Molar mass | 18.01528(33) g/mol | |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid, almost colorless liquid with a hint of blue, colorless gas[3] | |

| Odor | None | |

| Density | Liquid:[4] 0.9998396 g/mL at 0 °C 0.9970474 g/mL at 25 °C 0.961893 g/mL at 95 °C Solid:[5] 0.9167 g/ml at 0 °C |

|

| Melting point | 0.00 °C (32.00 °F; 273.15 K) [b] | |

| Boiling point | 99.98 °C (211.96 °F; 373.13 K)[15][b] | |

| Solubility | Poorly soluble in haloalkanes, aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, ethers.[6] Improved solubility in carboxylates, alcohols, ketones, amines. Miscible with methanol, ethanol, propanol, isopropanol, acetone, glycerol, 1,4-dioxane, tetrahydrofuran, sulfolane, acetaldehyde, dimethylformamide, dimethoxyethane, dimethyl sulfoxide, acetonitrile. Partially miscible with diethyl ether, methyl ethyl ketone, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, bromine. | |

| Vapor pressure | 3.1690 kilopascals or 0.031276 atm at 25 °C[7] | |

| Acidity (pKa) | 13.995[8][9][a] | |

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.995 | |

| Conjugate acid | Hydronium H3O+ (pKa = 0) | |

| Conjugate base | Hydroxide OH– (pKb = 0) | |

| Thermal conductivity | 0.6065 W/(m·K)[12] | |

|

Refractive index (nD) |

1.3330 (20 °C)[13] | |

| Viscosity | 0.890 mPa·s (0.890 cP)[14] | |

| Structure | ||

|

Crystal structure |

Hexagonal | |

|

Point group |

C2v | |

|

Molecular shape |

Bent | |

|

Dipole moment |

1.8546 D[16] | |

| Thermochemistry | ||

|

Heat capacity (C) |

75.385 ± 0.05 J/(mol·K)[17] | |

|

Std molar |

69.95 ± 0.03 J/(mol·K)[17] | |

|

Std enthalpy of |

−285.83 ± 0.04 kJ/mol[6][17] | |

|

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) |

−237.24 kJ/mol[6] | |

| Hazards | ||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | ||

|

Main hazards |

Drowning Avalanche (as snow) Water intoxication |

|

| GHS labelling:[18] | ||

|

Hazard statements |

[?] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

0 0 0 |

|

| Flash point | Non-flammable | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | SDS | |

| Related compounds | ||

|

Other cations |

Hydrogen sulfide Hydrogen selenide Hydrogen telluride Hydrogen polonide Hydrogen peroxide |

|

|

Related solvents |

Acetone Methanol |

|

| Supplementary data page | ||

| Water (data page) | ||

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references |

Water (H2O) is a polar inorganic compound that is at room temperature a tasteless and odorless liquid, which is nearly colorless apart from an inherent hint of blue. It is by far the most studied chemical compound[19] and is described as the «universal solvent»[20] and the «solvent of life».[21] It is the most abundant substance on the surface of Earth[22] and the only common substance to exist as a solid, liquid, and gas on Earth’s surface.[23] It is also the third most abundant molecule in the universe (behind molecular hydrogen and carbon monoxide).[22]

Water molecules form hydrogen bonds with each other and are strongly polar. This polarity allows it to dissociate ions in salts and bond to other polar substances such as alcohols and acids, thus dissolving them. Its hydrogen bonding causes its many unique properties, such as having a solid form less dense than its liquid form,[c] a relatively high boiling point of 100 °C for its molar mass, and a high heat capacity.

Water is amphoteric, meaning that it can exhibit properties of an acid or a base, depending on the pH of the solution that it is in; it readily produces both H+

and OH−

ions.[c] Related to its amphoteric character, it undergoes self-ionization. The product of the activities, or approximately, the concentrations of H+

and OH−

is a constant, so their respective concentrations are inversely proportional to each other.[24]

Physical properties[edit]

Water is the chemical substance with chemical formula H

2O; one molecule of water has two hydrogen atoms covalently bonded to a single oxygen atom.[25] Water is a tasteless, odorless liquid at ambient temperature and pressure. Liquid water has weak absorption bands at wavelengths of around 750 nm which cause it to appear to have a blue colour.[3] This can easily be observed in a water-filled bath or wash-basin whose lining is white. Large ice crystals, as in glaciers, also appear blue.

Under standard conditions, water is primarily a liquid, unlike other analogous hydrides of the oxygen family, which are generally gaseous. This unique property of water is due to hydrogen bonding. The molecules of water are constantly moving concerning each other, and the hydrogen bonds are continually breaking and reforming at timescales faster than 200 femtoseconds (2 × 10−13 seconds).[26] However, these bonds are strong enough to create many of the peculiar properties of water, some of which make it integral to life.

Water, ice, and vapour[edit]

Within the Earth’s atmosphere and surface, the liquid phase is the most common and is the form that is generally denoted by the word «water». The solid phase of water is known as ice and commonly takes the structure of hard, amalgamated crystals, such as ice cubes, or loosely accumulated granular crystals, like snow. Aside from common hexagonal crystalline ice, other crystalline and amorphous phases of ice are known. The gaseous phase of water is known as water vapor (or steam). Visible steam and clouds are formed from minute droplets of water suspended in the air.

Water also forms a supercritical fluid. The critical temperature is 647 K and the critical pressure is 22.064 MPa. In nature, this only rarely occurs in extremely hostile conditions. A likely example of naturally occurring supercritical water is in the hottest parts of deep water hydrothermal vents, in which water is heated to the critical temperature by volcanic plumes and the critical pressure is caused by the weight of the ocean at the extreme depths where the vents are located. This pressure is reached at a depth of about 2200 meters: much less than the mean depth of the ocean (3800 meters).[27]

Heat capacity and heats of vaporization and fusion[edit]

Heat of vaporization of water from melting to critical temperature

Water has a very high specific heat capacity of 4184 J/(kg·K) at 20 °C (4182 J/(kg·K) at 25 °C) —the second-highest among all the heteroatomic species (after ammonia), as well as a high heat of vaporization (40.65 kJ/mol or 2257 kJ/kg at the normal boiling point), both of which are a result of the extensive hydrogen bonding between its molecules. These two unusual properties allow water to moderate Earth’s climate by buffering large fluctuations in temperature. Most of the additional energy stored in the climate system since 1970 has accumulated in the oceans.[28]

The specific enthalpy of fusion (more commonly known as latent heat) of water is 333.55 kJ/kg at 0 °C: the same amount of energy is required to melt ice as to warm ice from −160 °C up to its melting point or to heat the same amount of water by about 80 °C. Of common substances, only that of ammonia is higher. This property confers resistance to melting on the ice of glaciers and drift ice. Before and since the advent of mechanical refrigeration, ice was and still is in common use for retarding food spoilage.

The specific heat capacity of ice at −10 °C is 2030 J/(kg·K)[29] and the heat capacity of steam at 100 °C is 2080 J/(kg·K).[30]

Density of water and ice[edit]

Density of ice and water as a function of temperature

The density of water is about 1 gram per cubic centimetre (62 lb/cu ft): this relationship was originally used to define the gram.[31] The density varies with temperature, but not linearly: as the temperature increases, the density rises to a peak at 3.98 °C (39.16 °F) and then decreases;[32] the initial increase is unusual because most liquids undergo thermal expansion so that the density only decreases as a function of temperature. The increase observed for water from 0 °C (32 °F) to 3.98 °C (39.16 °F) and for a few other liquids[d] is described as negative thermal expansion. Regular, hexagonal ice is also less dense than liquid water—upon freezing, the density of water decreases by about 9%.[35][e]

These peculiar effects are due to the highly directional bonding of water molecules via the hydrogen bonds: ice and liquid water at low temperature have comparatively low-density, low-energy open lattice structures. The breaking of hydrogen bonds on melting with increasing temperature in the range 0–4 °C allows for a denser molecular packing in which some of the lattice cavities are filled by water molecules.[32][36] Above 4 °C, however, thermal expansion becomes the dominant effect,[36] and water near the boiling point (100 °C) is about 4% less dense than water at 4 °C (39 °F).[35][f]

Under increasing pressure, ice undergoes a number of transitions to other polymorphs with higher density than liquid water, such as ice II, ice III, high-density amorphous ice (HDA), and very-high-density amorphous ice (VHDA).[37][38]

Temperature distribution in a lake in summer and winter

The unusual density curve and lower density of ice than of water is essential for much of the life on earth—if water were most dense at the freezing point, then in winter the cooling at the surface would lead to convective mixing. Once 0 °C are reached, the water body would freeze from the bottom up, and all life in it would be killed.[35] Furthermore, given that water is a good thermal insulator (due to its heat capacity), some frozen lakes might not completely thaw in summer.[35] As it is, the inversion of the density curve leads to a stable layering for surface temperatures below 4 °C, and with the layer of ice that floats on top insulating the water below,[39] even e.g., Lake Baikal in central Siberia freezes only to about 1 m thickness in winter. In general, for deep enough lakes, the temperature at the bottom stays constant at about 4 °C (39 °F) throughout the year (see diagram).[35]

Density of saltwater and ice[edit]

The density of saltwater depends on the dissolved salt content as well as the temperature. Ice still floats in the oceans, otherwise, they would freeze from the bottom up. However, the salt content of oceans lowers the freezing point by about 1.9 °C[40] (see here for explanation) and lowers the temperature of the density maximum of water to the former freezing point at 0 °C. This is why, in ocean water, the downward convection of colder water is not blocked by an expansion of water as it becomes colder near the freezing point. The oceans’ cold water near the freezing point continues to sink. So creatures that live at the bottom of cold oceans like the Arctic Ocean generally live in water 4 °C colder than at the bottom of frozen-over fresh water lakes and rivers.

As the surface of saltwater begins to freeze (at −1.9 °C[40] for normal salinity seawater, 3.5%) the ice that forms is essentially salt-free, with about the same density as freshwater ice. This ice floats on the surface, and the salt that is «frozen out» adds to the salinity and density of the seawater just below it, in a process known as brine rejection. This denser saltwater sinks by convection and the replacing seawater is subject to the same process. This produces essentially freshwater ice at −1.9 °C[40] on the surface. The increased density of the seawater beneath the forming ice causes it to sink towards the bottom. On a large scale, the process of brine rejection and sinking cold salty water results in ocean currents forming to transport such water away from the Poles, leading to a global system of currents called the thermohaline circulation.

Miscibility and condensation[edit]

Red line shows saturation

Water is miscible with many liquids, including ethanol in all proportions. Water and most oils are immiscible usually forming layers according to increasing density from the top. This can be predicted by comparing the polarity. Water being a relatively polar compound will tend to be miscible with liquids of high polarity such as ethanol and acetone, whereas compounds with low polarity will tend to be immiscible and poorly soluble such as with hydrocarbons.

As a gas, water vapor is completely miscible with air. On the other hand, the maximum water vapor pressure that is thermodynamically stable with the liquid (or solid) at a given temperature is relatively low compared with total atmospheric pressure. For example, if the vapor’s partial pressure is 2% of atmospheric pressure and the air is cooled from 25 °C, starting at about 22 °C, water will start to condense, defining the dew point, and creating fog or dew. The reverse process accounts for the fog burning off in the morning. If the humidity is increased at room temperature, for example, by running a hot shower or a bath, and the temperature stays about the same, the vapor soon reaches the pressure for phase change and then condenses out as minute water droplets, commonly referred to as steam.

A saturated gas or one with 100% relative humidity is when the vapor pressure of water in the air is at equilibrium with vapor pressure due to (liquid) water; water (or ice, if cool enough) will fail to lose mass through evaporation when exposed to saturated air. Because the amount of water vapor in the air is small, relative humidity, the ratio of the partial pressure due to the water vapor to the saturated partial vapor pressure, is much more useful. Vapor pressure above 100% relative humidity is called supersaturated and can occur if the air is rapidly cooled, for example, by rising suddenly in an updraft.[g]

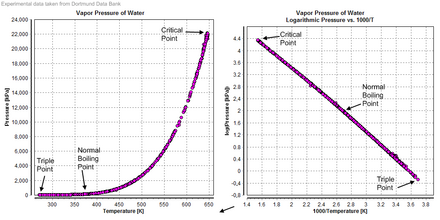

Vapor pressure[edit]

Vapor pressure diagrams of water

Compressibility[edit]

The compressibility of water is a function of pressure and temperature. At 0 °C, at the limit of zero pressure, the compressibility is 5.1×10−10 Pa−1. At the zero-pressure limit, the compressibility reaches a minimum of 4.4×10−10 Pa−1 around 45 °C before increasing again with increasing temperature. As the pressure is increased, the compressibility decreases, being 3.9×10−10 Pa−1 at 0 °C and 100 megapascals (1,000 bar).[41]

The bulk modulus of water is about 2.2 GPa.[42] The low compressibility of non-gasses, and of water in particular, leads to their often being assumed as incompressible. The low compressibility of water means that even in the deep oceans at 4 km depth, where pressures are 40 MPa, there is only a 1.8% decrease in volume.[42]

The bulk modulus of water ice ranges from 11.3 GPa at 0 K up to 8.6 GPa at 273 K.[43] The large change in the compressibility of ice as a function of temperature is the result of its relatively large thermal expansion coefficient compared to other common solids.

Triple point[edit]

The solid/liquid/vapour triple point of liquid water, ice Ih and water vapor in the lower left portion of a water phase diagram.

The temperature and pressure at which ordinary solid, liquid, and gaseous water coexist in equilibrium is a triple point of water. Since 1954, this point had been used to define the base unit of temperature, the kelvin,[44][45] but, starting in 2019, the kelvin is now defined using the Boltzmann constant, rather than the triple point of water.[46]

Due to the existence of many polymorphs (forms) of ice, water has other triple points, which have either three polymorphs of ice or two polymorphs of ice and liquid in equilibrium.[45] Gustav Heinrich Johann Apollon Tammann in Göttingen produced data on several other triple points in the early 20th century. Kamb and others documented further triple points in the 1960s.[47][48][49]

| Phases in stable equilibrium | Pressure | Temperature |

|---|---|---|

| liquid water, ice Ih, and water vapor | 611.657 Pa[50] | 273.16 K (0.01 °C) |

| liquid water, ice Ih, and ice III | 209.9 MPa | 251 K (−22 °C) |

| liquid water, ice III, and ice V | 350.1 MPa | −17.0 °C |

| liquid water, ice V, and ice VI | 632.4 MPa | 0.16 °C |

| ice Ih, Ice II, and ice III | 213 MPa | −35 °C |

| ice II, ice III, and ice V | 344 MPa | −24 °C |

| ice II, ice V, and ice VI | 626 MPa | −70 °C |

Melting point[edit]

The melting point of ice is 0 °C (32 °F; 273 K) at standard pressure; however, pure liquid water can be supercooled well below that temperature without freezing if the liquid is not mechanically disturbed. It can remain in a fluid state down to its homogeneous nucleation point of about 231 K (−42 °C; −44 °F).[51] The melting point of ordinary hexagonal ice falls slightly under moderately high pressures, by 0.0073 °C (0.0131 °F)/atm[h] or about 0.5 °C (0.90 °F)/70 atm[i][52] as the stabilization energy of hydrogen bonding is exceeded by intermolecular repulsion, but as ice transforms into its polymorphs (see crystalline states of ice) above 209.9 MPa (2,072 atm), the melting point increases markedly with pressure, i.e., reaching 355 K (82 °C) at 2.216 GPa (21,870 atm) (triple point of Ice VII[53]).

Electrical properties[edit]

Electrical conductivity[edit]

Pure water containing no exogenous ions is an excellent electronic insulator, but not even «deionized» water is completely free of ions. Water undergoes autoionization in the liquid state when two water molecules form one hydroxide anion (OH−

) and one hydronium cation (H

3O+

). Because of autoionization, at ambient temperatures pure liquid water has a similar intrinsic charge carrier concentration to the semiconductor germanium and an intrinsic charge carrier concentration three orders of magnitude greater than the semiconductor silicon, hence, based on charge carrier concentration, water can not be considered to be a completely dielectric material or electrical insulator but to be a limited conductor of ionic charge.[54]

Because water is such a good solvent, it almost always has some solute dissolved in it, often a salt. If water has even a tiny amount of such an impurity, then the ions can carry charges back and forth, allowing the water to conduct electricity far more readily.

It is known that the theoretical maximum electrical resistivity for water is approximately 18.2 MΩ·cm (182 kΩ·m) at 25 °C.[55] This figure agrees well with what is typically seen on reverse osmosis, ultra-filtered and deionized ultra-pure water systems used, for instance, in semiconductor manufacturing plants. A salt or acid contaminant level exceeding even 100 parts per trillion (ppt) in otherwise ultra-pure water begins to noticeably lower its resistivity by up to several kΩ·m.[citation needed]

In pure water, sensitive equipment can detect a very slight electrical conductivity of 0.05501 ± 0.0001 μS/cm at 25.00 °C.[55] Water can also be electrolyzed into oxygen and hydrogen gases but in the absence of dissolved ions this is a very slow process, as very little current is conducted. In ice, the primary charge carriers are protons (see proton conductor).[56] Ice was previously thought to have a small but measurable conductivity of 1×10−10 S/cm, but this conductivity is now thought to be almost entirely from surface defects, and without those, ice is an insulator with an immeasurably small conductivity.[32]

Polarity and hydrogen bonding[edit]

A diagram showing the partial charges on the atoms in a water molecule

An important feature of water is its polar nature. The structure has a bent molecular geometry for the two hydrogens from the oxygen vertex. The oxygen atom also has two lone pairs of electrons. One effect usually ascribed to the lone pairs is that the H–O–H gas-phase bend angle is 104.48°,[57] which is smaller than the typical tetrahedral angle of 109.47°. The lone pairs are closer to the oxygen atom than the electrons sigma bonded to the hydrogens, so they require more space. The increased repulsion of the lone pairs forces the O–H bonds closer to each other. [58]

Another consequence of its structure is that water is a polar molecule. Due to the difference in electronegativity, a bond dipole moment points from each H to the O, making the oxygen partially negative and each hydrogen partially positive. A large molecular dipole, points from a region between the two hydrogen atoms to the oxygen atom. The charge differences cause water molecules to aggregate (the relatively positive areas being attracted to the relatively negative areas). This attraction, hydrogen bonding, explains many of the properties of water, such as its solvent properties.[59]

Although hydrogen bonding is a relatively weak attraction compared to the covalent bonds within the water molecule itself, it is responsible for several of the water’s physical properties. These properties include its relatively high melting and boiling point temperatures: more energy is required to break the hydrogen bonds between water molecules. In contrast, hydrogen sulfide (H

2S), has much weaker hydrogen bonding due to sulfur’s lower electronegativity. H

2S is a gas at room temperature, despite hydrogen sulfide having nearly twice the molar mass of water. The extra bonding between water molecules also gives liquid water a large specific heat capacity. This high heat capacity makes water a good heat storage medium (coolant) and heat shield.

Cohesion and adhesion[edit]

Water molecules stay close to each other (cohesion), due to the collective action of hydrogen bonds between water molecules. These hydrogen bonds are constantly breaking, with new bonds being formed with different water molecules; but at any given time in a sample of liquid water, a large portion of the molecules are held together by such bonds.[60]

Water also has high adhesion properties because of its polar nature. On clean, smooth glass the water may form a thin film because the molecular forces between glass and water molecules (adhesive forces) are stronger than the cohesive forces.[citation needed] In biological cells and organelles, water is in contact with membrane and protein surfaces that are hydrophilic; that is, surfaces that have a strong attraction to water. Irving Langmuir observed a strong repulsive force between hydrophilic surfaces. To dehydrate hydrophilic surfaces—to remove the strongly held layers of water of hydration—requires doing substantial work against these forces, called hydration forces. These forces are very large but decrease rapidly over a nanometer or less.[61] They are important in biology, particularly when cells are dehydrated by exposure to dry atmospheres or to extracellular freezing.[62]

Surface tension[edit]

This paper clip is under the water level, which has risen gently and smoothly. Surface tension prevents the clip from submerging and the water from overflowing the glass edges.

Temperature dependence of the surface tension of pure water

Water has an unusually high surface tension of 71.99 mN/m at 25 °C[63] which is caused by the strength of the hydrogen bonding between water molecules.[64] This allows insects to walk on water.[64]

Capillary action[edit]

Because water has strong cohesive and adhesive forces, it exhibits capillary action.[65] Strong cohesion from hydrogen bonding and adhesion allows trees to transport water more than 100 m upward.[64]

Water as a solvent[edit]

Water is an excellent solvent due to its high dielectric constant.[66] Substances that mix well and dissolve in water are known as hydrophilic («water-loving») substances, while those that do not mix well with water are known as hydrophobic («water-fearing») substances.[67] The ability of a substance to dissolve in water is determined by whether or not the substance can match or better the strong attractive forces that water molecules generate between other water molecules. If a substance has properties that do not allow it to overcome these strong intermolecular forces, the molecules are precipitated out from the water. Contrary to the common misconception, water and hydrophobic substances do not «repel», and the hydration of a hydrophobic surface is energetically, but not entropically, favorable.

When an ionic or polar compound enters water, it is surrounded by water molecules (hydration). The relatively small size of water molecules (~ 3 angstroms) allows many water molecules to surround one molecule of solute. The partially negative dipole ends of the water are attracted to positively charged components of the solute, and vice versa for the positive dipole ends.

In general, ionic and polar substances such as acids, alcohols, and salts are relatively soluble in water, and nonpolar substances such as fats and oils are not. Nonpolar molecules stay together in water because it is energetically more favorable for the water molecules to hydrogen bond to each other than to engage in van der Waals interactions with non-polar molecules.

An example of an ionic solute is table salt; the sodium chloride, NaCl, separates into Na+

cations and Cl−

anions, each being surrounded by water molecules. The ions are then easily transported away from their crystalline lattice into solution. An example of a nonionic solute is table sugar. The water dipoles make hydrogen bonds with the polar regions of the sugar molecule (OH groups) and allow it to be carried away into solution.

Quantum tunneling[edit]

The quantum tunneling dynamics in water was reported as early as 1992. At that time it was known that there are motions which destroy and regenerate the weak hydrogen bond by internal rotations of the substituent water monomers.[68] On 18 March 2016, it was reported that the hydrogen bond can be broken by quantum tunneling in the water hexamer. Unlike previously reported tunneling motions in water, this involved the concerted breaking of two hydrogen bonds.[69] Later in the same year, the discovery of the quantum tunneling of water molecules was reported.[70]

Electromagnetic absorption[edit]

Water is relatively transparent to visible light, near ultraviolet light, and far-red light, but it absorbs most ultraviolet light, infrared light, and microwaves. Most photoreceptors and photosynthetic pigments utilize the portion of the light spectrum that is transmitted well through water. Microwave ovens take advantage of water’s opacity to microwave radiation to heat the water inside of foods. Water’s light blue colour is caused by weak absorption in the red part of the visible spectrum.[3][71]

Structure[edit]

A single water molecule can participate in a maximum of four hydrogen bonds because it can accept two bonds using the lone pairs on oxygen and donate two hydrogen atoms. Other molecules like hydrogen fluoride, ammonia, and methanol can also form hydrogen bonds. However, they do not show anomalous thermodynamic, kinetic, or structural properties like those observed in water because none of them can form four hydrogen bonds: either they cannot donate or accept hydrogen atoms, or there are steric effects in bulky residues. In water, intermolecular tetrahedral structures form due to the four hydrogen bonds, thereby forming an open structure and a three-dimensional bonding network, resulting in the anomalous decrease in density when cooled below 4 °C. This repeated, constantly reorganizing unit defines a three-dimensional network extending throughout the liquid. This view is based upon neutron scattering studies and computer simulations, and it makes sense in the light of the unambiguously tetrahedral arrangement of water molecules in ice structures.

However, there is an alternative theory for the structure of water. In 2004, a controversial paper from Stockholm University suggested that water molecules in the liquid state typically bind not to four but only two others; thus forming chains and rings. The term «string theory of water» (which is not to be confused with the string theory of physics) was coined. These observations were based upon X-ray absorption spectroscopy that probed the local environment of individual oxygen atoms.[72]

Molecular structure[edit]

The repulsive effects of the two lone pairs on the oxygen atom cause water to have a bent, not linear, molecular structure,[73] allowing it to be polar. The hydrogen–oxygen–hydrogen angle is 104.45°, which is less than the 109.47° for ideal sp3 hybridization. The valence bond theory explanation is that the oxygen atom’s lone pairs are physically larger and therefore take up more space than the oxygen atom’s bonds to the hydrogen atoms.[74] The molecular orbital theory explanation (Bent’s rule) is that lowering the energy of the oxygen atom’s nonbonding hybrid orbitals (by assigning them more s character and less p character) and correspondingly raising the energy of the oxygen atom’s hybrid orbitals bonded to the hydrogen atoms (by assigning them more p character and less s character) has the net effect of lowering the energy of the occupied molecular orbitals because the energy of the oxygen atom’s nonbonding hybrid orbitals contributes completely to the energy of the oxygen atom’s lone pairs while the energy of the oxygen atom’s other two hybrid orbitals contributes only partially to the energy of the bonding orbitals (the remainder of the contribution coming from the hydrogen atoms’ 1s orbitals).

Chemical properties[edit]

Self-ionization[edit]

In liquid water there is some self-ionization giving hydronium ions and hydroxide ions.

- 2 H

2O ⇌ H

3O+

+ OH−

The equilibrium constant for this reaction, known as the ionic product of water, ![K_{{{rm {w}}}}=[{{rm {{H_{3}O^{+}}}}}][{{rm {{OH^{-}}}}}]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/86dca39006c4f875cacc14395c7ff6e38a09d990)

) equals that of the (solvated) hydrogen ion (H+

), with a value close to 10−7 mol L−1 at 25 °C.[75] See data page for values at other temperatures.

The thermodynamic equilibrium constant is a quotient of thermodynamic activities of all products and reactants including water:

However for dilute solutions, the activity of a solute such as H3O+ or OH− is approximated by its concentration, and the activity of the solvent H2O is approximated by 1, so that we obtain the simple ionic product ![{displaystyle K_{rm {eq}}approx K_{rm {w}}=[{rm {H_{3}O^{+}}}][{rm {OH^{-}}}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c479a6b2710d07dd3952fcc072550c0e8537e70)

Geochemistry[edit]

The action of water on rock over long periods of time typically leads to weathering and water erosion, physical processes that convert solid rocks and minerals into soil and sediment, but under some conditions chemical reactions with water occur as well, resulting in metasomatism or mineral hydration, a type of chemical alteration of a rock which produces clay minerals. It also occurs when Portland cement hardens.

Water ice can form clathrate compounds, known as clathrate hydrates, with a variety of small molecules that can be embedded in its spacious crystal lattice. The most notable of these is methane clathrate, 4 CH

4·23H

2O, naturally found in large quantities on the ocean floor.

Acidity in nature[edit]

Rain is generally mildly acidic, with a pH between 5.2 and 5.8 if not having any acid stronger than carbon dioxide.[76] If high amounts of nitrogen and sulfur oxides are present in the air, they too will dissolve into the cloud and raindrops, producing acid rain.

Isotopologues[edit]

Several isotopes of both hydrogen and oxygen exist, giving rise to several known isotopologues of water. Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water is the current international standard for water isotopes. Naturally occurring water is almost completely composed of the neutron-less hydrogen isotope protium. Only 155 ppm include deuterium (2

H or D), a hydrogen isotope with one neutron, and fewer than 20 parts per quintillion include tritium (3

H or T), which has two neutrons. Oxygen also has three stable isotopes, with 16

O present in 99.76%, 17

O in 0.04%, and 18

O in 0.2% of water molecules.[77]

Deuterium oxide, D

2O, is also known as heavy water because of its higher density. It is used in nuclear reactors as a neutron moderator. Tritium is radioactive, decaying with a half-life of 4500 days; THO exists in nature only in minute quantities, being produced primarily via cosmic ray-induced nuclear reactions in the atmosphere. Water with one protium and one deuterium atom HDO occur naturally in ordinary water in low concentrations (~0.03%) and D

2O in far lower amounts (0.000003%) and any such molecules are temporary as the atoms recombine.

The most notable physical differences between H

2O and D

2O, other than the simple difference in specific mass, involve properties that are affected by hydrogen bonding, such as freezing and boiling, and other kinetic effects. This is because the nucleus of deuterium is twice as heavy as protium, and this causes noticeable differences in bonding energies. The difference in boiling points allows the isotopologues to be separated. The self-diffusion coefficient of H

2O at 25 °C is 23% higher than the value of D

2O.[78] Because water molecules exchange hydrogen atoms with one another, hydrogen deuterium oxide (DOH) is much more common in low-purity heavy water than pure dideuterium monoxide D

2O.

Consumption of pure isolated D

2O may affect biochemical processes—ingestion of large amounts impairs kidney and central nervous system function. Small quantities can be consumed without any ill-effects; humans are generally unaware of taste differences,[79] but sometimes report a burning sensation[80] or sweet flavor.[81] Very large amounts of heavy water must be consumed for any toxicity to become apparent. Rats, however, are able to avoid heavy water by smell, and it is toxic to many animals.[82]

Light water refers to deuterium-depleted water (DDW), water in which the deuterium content has been reduced below the standard 155 ppm level.

Occurrence[edit]

Water is the most abundant substance on Earth and also the third most abundant molecule in the universe, after H

2 and CO.[22] 0.23 ppm of the earth’s mass is water and 97.39% of the global water volume of 1.38×109 km3 is found in the oceans.[83]

Reactions[edit]

Acid-base reactions[edit]

Water is amphoteric: it has the ability to act as either an acid or a base in chemical reactions.[84] According to the Brønsted-Lowry definition, an acid is a proton (H+

) donor and a base is a proton acceptor.[85] When reacting with a stronger acid, water acts as a base; when reacting with a stronger base, it acts as an acid.[85] For instance, water receives an H+

ion from HCl when hydrochloric acid is formed:

- HCl

(acid) + H

2O

(base) ⇌ H

3O+

+ Cl−

In the reaction with ammonia, NH

3, water donates a H+

ion, and is thus acting as an acid:

- NH

3

(base) + H

2O

(acid) ⇌ NH+

4 + OH−

Because the oxygen atom in water has two lone pairs, water often acts as a Lewis base, or electron-pair donor, in reactions with Lewis acids, although it can also react with Lewis bases, forming hydrogen bonds between the electron pair donors and the hydrogen atoms of water. HSAB theory describes water as both a weak hard acid and a weak hard base, meaning that it reacts preferentially with other hard species:

- H+

(Lewis acid) + H

2O

(Lewis base) → H

3O+

- Fe3+

(Lewis acid) + H

2O

(Lewis base) → Fe(H

2O)3+

6

- Cl−

(Lewis base) + H

2O

(Lewis acid) → Cl(H

2O)−

6

When a salt of a weak acid or of a weak base is dissolved in water, water can partially hydrolyze the salt, producing the corresponding base or acid, which gives aqueous solutions of soap and baking soda their basic pH:

- Na

2CO

3 + H

2O ⇌ NaOH + NaHCO

3

Ligand chemistry[edit]

Water’s Lewis base character makes it a common ligand in transition metal complexes, examples of which include metal aquo complexes such as Fe(H

2O)2+

6 to perrhenic acid, which contains two water molecules coordinated to a rhenium center. In solid hydrates, water can be either a ligand or simply lodged in the framework, or both. Thus, FeSO

4·7H

2O consists of [Fe2(H2O)6]2+ centers and one «lattice water». Water is typically a monodentate ligand, i.e., it forms only one bond with the central atom.[86]

Some hydrogen-bonding contacts in FeSO4.7H2O. This metal aquo complex crystallizes with one molecule of «lattice» water, which interacts with the sulfate and with the [Fe(H2O)6]2+ centers.

Organic chemistry[edit]

As a hard base, water reacts readily with organic carbocations; for example in a hydration reaction, a hydroxyl group (OH−

) and an acidic proton are added to the two carbon atoms bonded together in the carbon-carbon double bond, resulting in an alcohol. When the addition of water to an organic molecule cleaves the molecule in two, hydrolysis is said to occur. Notable examples of hydrolysis are the saponification of fats and the digestion of proteins and polysaccharides. Water can also be a leaving group in SN2 substitution and E2 elimination reactions; the latter is then known as a dehydration reaction.

Water in redox reactions[edit]

Water contains hydrogen in the oxidation state +1 and oxygen in the oxidation state −2.[87] It oxidizes chemicals such as hydrides, alkali metals, and some alkaline earth metals.[88][89] One example of an alkali metal reacting with water is:[90]