Уильям Шекспир — биография

Уильям Шекспир – английский драматург, поэт. Автор многочисленных пьес, поэм, сонетов, эпитафий, национальный поэт Англии. Именно его перу принадлежит трагедия Ромео и Джульетты

Сложно найти человека, который бы никогда не слышал имя Уильяма Шекспира – поэта и драматурга, гуманиста и человека Возрождения. Он самый великий англоязычный писатель, национальный поэт Великобритании и лучших драматург среди всех, известных в мире. Его произведения переведены и изданы практически на всех языках, некоторые из них входят в обязательную школьную программу. Фильмы, снятые на основе его пьес, остаются актуальными даже спустя несколько веков после их создания.

Детство

Родился Уильям Шекспир предположительно 23 апреля 1564 года в английском городе Стратфорд-апон-Эйвоне, недалеко от Лондона. Точная дата рождения поэта неизвестна, есть только данные о дне его крещения – 26 апреля.

Отца звали Джон Шекспир, он занимался земледелием, изготавливал перчатки и слыл мелким ростовщиком. Потом занимал должность олдермена, то есть, возглавлял муниципальное собрание, а потом стал во главе совета города. Мама мальчика – Мэри Арден принадлежала к старинному и очень уважаемому саксонскому роду.

Сохранились сведения о том, что Джон придерживался католической веры, за что впоследствии его преследовала церковь. Он был вынужден продать все земли, которые приобрел за свою жизнь. Джон постоянно платил штрафы протестантской церкви за то, что не ходил на службы. У супругов родилось восемь детей, Уильям был третьим из них.

Начальное образование Шекспир получил в родном городе Стратфорд. Он учился в грамматической школе, где основной упор делался на изучение латыни и древнегреческого языка.

В школе постоянно ставили пьесы на латыни, педагоги считали, что только таким образом можно глубоко изучить древние языки.

Есть мнение, что кроме грамматической школы, Уильям учился еще и в королевской школе. Там он впервые прочел труды древнеримских поэтов.

Загадочные семь лет

Поэт принадлежит к тем историческим личностям, биографию которых пришлось складывать как мозаику из мелких частиц. Нет никаких биографических записей о его жизни, поэтому источники сведений о жизни Шекспира были в основном второстепенными. К примеру, записи каких-то административных учреждений или высказывание о нем современников.

Самым загадочным отрезком его жизни стали семь лет, которые прошли между рождением двойняшек и первыми упоминаниями о его деятельности в Лондоне. Для исследователей этот отрезок стал настоящей загадкой.

Говорили, что он поступил на службу к знатному землевладельцу, потом учительствовал, работал в театре в качестве суфлера, рабочего сцены, и некоторое время коневода. Однако насколько эти сведения достоверны, никто сказать не может.

Могут быть знакомы

Лондон

Первое упоминание о Шекспире появляется в 1592 году. Английский поэт Роберт Грин дал свою оценку творчеству Уильяма, и его высказывание появилось в прессе. Аристократ посмеивался над молодым драматургом, потому что понимал, что перед ним достойный конкурент, хотя и без благородного происхождения и достойного образования. Примерно в это время появляются упоминания о первой постановке пьесы «Генрих VI», авторство которой принадлежит Шекспиру. Она вышла на сцене лондонского театра «Роза».

Пьеса написана в жанре хроники, очень модном в те годы в Англии. Это было типичным для эпохи Возрождения, повествование имело эпический характер, и зачастую состояло из разрозненных картин и сценок, не имеющих связи между собой. В хрониках воспевалась государственность страны, порицались междоусобные войны и феодальная раздробленность. В 1594 году Уильям Шекспир вступил в сообщество актеров под названием «Слуги лорда-камергера». Прошло немного времени, и он стал одним из его соучредителей.

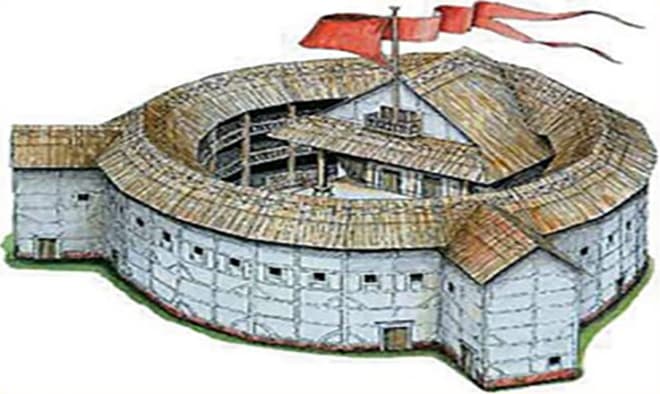

Спектакли пользовались большим успехом, что позволило труппе разбогатеть буквально за короткий промежуток времени. Поэтому было принято решение о строительстве отдельного здания для театра, получившего название «Глобус». Стройка длилась пять лет. В 1608 году сообщество стало владельцем еще и закрытого помещения «Блэкфрайерс».

Такого успеха артисты достигли благодаря благосклонности английских монархов. Елизавета I и ее сын Яков I имели особое отношение к театру. Яков даже разрешил коллективу сменить статус, и в 1603-м труппа стала называться «Слуги Короля».

Уильям был не только автором пьес, он активно участвовал в постановках спектаклей. До наших дней дошли сведения, что всех главных героев своих произведений автор играл сам.

Творчество

Вклад Шекспира в сокровищницу мировой литературы сложно переоценить. Более пяти веков его произведения вдохновляют актеров и композиторов, театральных и кинорежиссеров. Творческая деятельность Уильяма состоит из нескольких периодов, в каждом из которых он полностью менял стиль написания своих шедевров.

Его первые произведения были копиями популярных в те годы сюжетов и жанров – «Укрощение строптивой», «Тит Андроник» реальное тому подтверждение. Первая написана в комедийном жанре, вторая в «трагедии ужаса». Произведения имели громоздкую форму, большое количество ролей и очень сложный в восприятии слог. Это было время учебы, постижения азов написания драматических произведений.

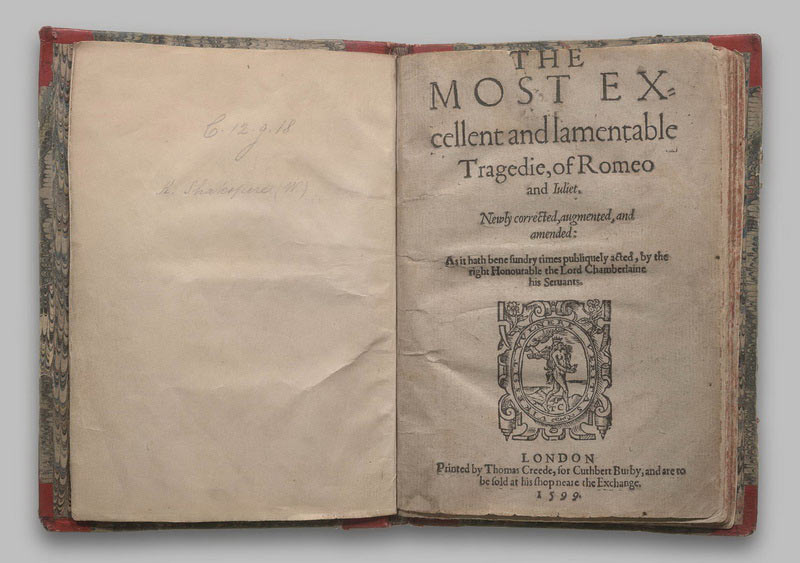

Во второй половине 90-х годов 16 века в драматургии появились сочинения, которые характеризовались отточенными формами и содержанием. Шекспир занялся поисками новой формы, при этом он по-прежнему творит в рамках ренессансной трагедии и комедии. В старых, изживших себя формах, прослеживается новое содержание. Так родились гениальные произведения «Сон в летнюю ночь», «Ромео и Джульетта», «Венецианский купец». Они отличались свежестью повествования, облаченной в запоминающийся своей необычностью сюжет. Пьесы Шекспира набирают популярность у самого разного зрителя.

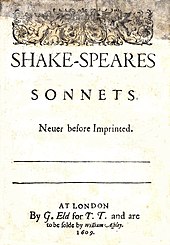

Одновременно с этим, Уильям стал автором цикла сонетов, используя очень популярный жанр любовной лирики в стихах. На протяжении двух столетий об этих сонетах не вспоминали, а когда наступила эпоха романтизма, они снова оказались на вершине славы. В 19-м веке стало модным цитировать именно эти бессмертные строки Шекспира.

Эти стихи стали своеобразным посланием неизвестному молодому человеку, и только 26 последних из ста пятидесяти четырех сочинений обращены к прекрасной брюнетке. По мнению некоторых исследователей, в сонетах можно найти указание на моменты из биографии автора, в том числе и на его нетрадиционную ориентацию. Однако другие историки предполагают, что посредством своих сочинений поэт общается со своим другом и покровителем графом Саутгемптоном. Именно таким образом тогда происходило общение в светском обществе.

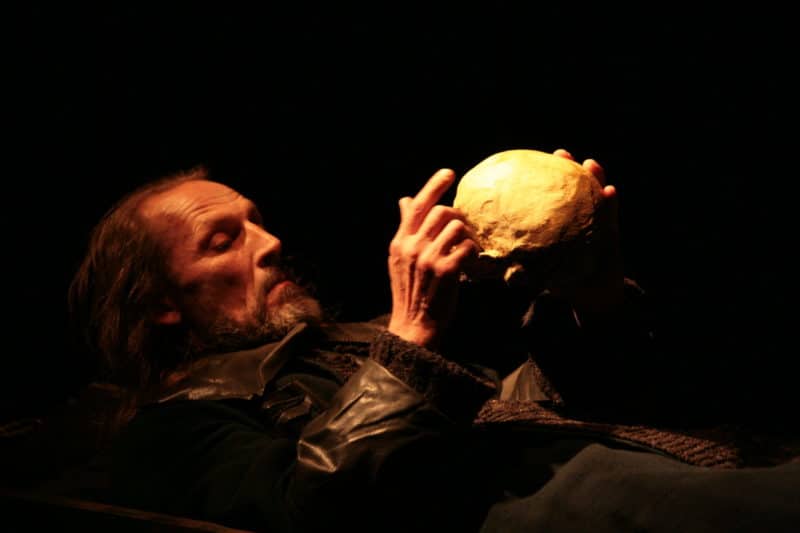

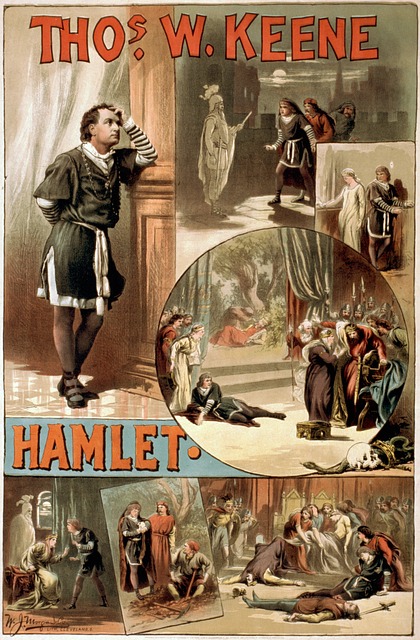

На границе двух веков Уильям создал свои бессмертные произведения, увековечившие его имя в истории литературы и театра. В это время он уже был состоявшимся и успешным литератором, достаточно обеспеченным в финансовом плане. Он пишет пьесы, принесшие ему известность далеко за пределами родной Англии. Одна за одной выходят трагедии «Макбет», «Гамлет», «Отелло», «Король Лир». Благодаря этим произведениям театр «Глобус» приобрел невероятную популярность и стал самым посещаемым увеселительным заведением в Лондоне. Вскоре владельцы театра прочувствовали эту славу на собственном финансовом состоянии – они стали в несколько раз богаче.

Третий период творчества великого драматурга начался уже на закате его профессиональной деятельности. Он стал автором произведений, которые имели совершенно новую форму, где трагедия вплотную переплетается с комедийным жанром, а сказка соседствует с повседневной жизнью. Среди них стоит отметить «Зимнюю сказку», «Бурю», «Антония и Клеопатру», «Кориолана». Эти шедевры мастера лишний раз подтверждают, что он стал настоящим знатоком драматического жанра, с легкостью собирающего в одном месте трагедийные и сказочные черты, высокий слог и обычную речь.

Многие произведения Шекспира увидели свет еще при жизни автора. А вот до издания полного собрания сочинений дело дошло только в 1623-м. Сборник вышел только благодаря участию ближайших друзей драматурга – Генри Кондела и Джона Хеминга, артистов труппы театра «Глобус». В книгу вошло тридцать шесть пьес Шекспира, и ее назвали «Первое фолио».

На протяжении 17 века удалось напечатать еще три таких фолио, некоторые из них содержали изменения в тексте в сравнении с первоисточником.

Личная жизнь

Поэт очень рано устроил свою личную жизнь. Ему исполнилось всего 18, когда он завел романтические отношения с соседской девушкой Энн Хататуй. Ей на тот момент исполнилось 26, и вскоре влюбленные поженились. Такая спешка была вызвана беременностью Энн. В те годы добрачная беременность считалась чем-то закономерным, очень часто молодые люди женились, когда невеста уже находилась в интересном положении. Важно было только успеть обвенчаться до того, как родится малыш. В 1583-м Уильям стал отцом дочери Сьюзен, которую любил больше остальных своих детей. Спустя два года супруга подарила Шекспиру двойню – сына Хемнета и дочь Джудит.

Детей у них больше не было, скорее всего, по причине тяжелейших вторых родов Энн. В 1556-м семью постигло несчастье – Хемнет заболел дизентерией, и доктора не смогли спасти единственного наследника поэта. Вскоре Шекспир переехал в Лондон, а жена и дети остались жить в родном городе. Уильям регулярно навещал семью, хотя эти посещения были достаточно редкими.

О том, как устроилась личная жизнь Шекспира в Лондоне, точно ничего неизвестно. Ходило много слухов и пересудов о том, что он коротал ее не в полном одиночестве. По мнению исследователей биографии Шекспира, он имел любовные связи, причем, не только с женщинами. Однако проверить достоверность этой информации не представляется возможным.

Смерть

За несколько лет до смерти Уильям мучился от серьезного заболевания, в результате которого у него сильно изменился почерк. По этой же причине он не мог самостоятельно писать, и свои последние сочинения создал вместе с Джоном Флетчером, драматургом театра «Глобус».

В 1613 году Шекспир окончательно уезжает из Лондона, однако продолжает заниматься некоторыми делами театра. Он стал свидетелем со стороны защиты на суде у своего приятеля, успевает стать владельцем еще одного роскошного особняка в Блэкфриарском приходе. Несколько недель драматург живет у своего зятя – Джона Холла, супруга старшей дочери.

В том же, 1613-м, поэт составил завещание, по которому все нажитое имущество отписывает старшей дочери. Днем смерти Шекспира принято считать 23 апреля 1616 года, хотя эти сведения тоже ничем не подтверждены. Супруга скончалась через семь лет после его смерти.

На тот момент старшая дочь Сьюзен уже родила Шекспиру внучку Элизабет. Она потом дважды была замужем, но в 1867 году умерла, так и оставшись бездетной. Младшая дочь поэта – Джудит вышла замуж за Томаса Куини, вскоре после смерти Уильяма. В этом браке родилось три мальчика, однако они все умерли молодыми. Таким образом, прервался род гениального поэта, ни одного прямого наследника у него не осталось.

Состояние

Существуют некоторые свидетельства приличного состояния Шекспира. Судя по приобретенной недвижимости, поэт хорошо зарабатывал, и его финансовые дела шли отлично. Поговаривали, что он занимался ростовщичеством.

Значительные накопления драматурга помогли приобретению шикарного особняка в родном городе Стратфорде. Помимо этого, после смерти для Уильяма уже было готово место упокоения – алтарь церкви Святой Троицы, тоже в родном городе. И все это не благодаря особым заслугам перед городом, а потому, что он заранее оплатил приличную сумму за это место.

Факты

- Точную дату рождения Шекспира выяснить не удалось никому. Историки располагают только церковной записью об обряде его крещения, состоявшемся 26 апреля 1564 года. Биографы приходят к выводу, что мальчика крестили спустя три дня после рождения, поэтому ориентировочно ставят дату рождения 23 апреля, точно так же, что и дату смерти.

- Шекспир имел феноменальную память, обладал энциклопедическими знаниями. Он говорил на двух древних языках, помимо этого свободно общался на современном итальянском, французском, испанском языках, хотя дальше Англии никогда не выезжал. Уильям был знатоком истории и политики, музыки и живописи, досконально разбирался в ботанике.

- Историки постоянно обсуждают нетрадиционную ориентацию поэта, мотивируя тем, что он слишком долго жил без семьи и поддерживал тесную связь с графом Саутгемптоном. Последний был большим оригиналом, его часто видели в женской одежде и с накрашенным лицом. Хотя найти прямые доказательства этому пока никому не удалось.

- Много вопросов возникает и по поводу протестантского вероисповедания драматурга и его родных. Его отец был католиком, хотя прямых доказательств этому нет, да и во времена правления Елизаветы I эта вера была практически под запретом. Многим католикам приходилось откупаться и таким образом иметь возможность тайно бывать на католических богослужениях.

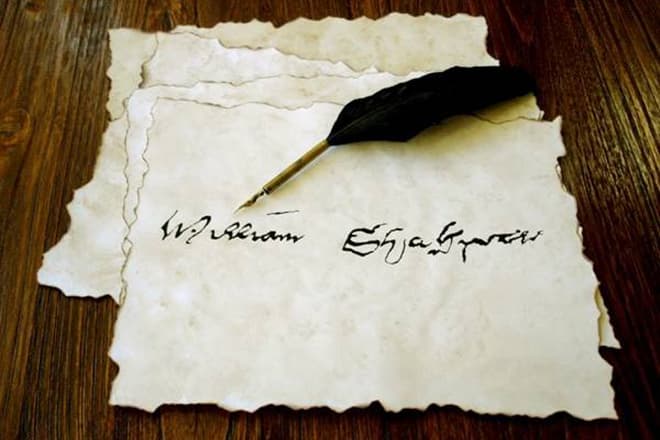

- Единственным автографом Шекспира, сохранившимся для потомков, стало его завещание. Там перечислено все состояние поэта, вплоть до незначительных мелочей, однако о литературных работах нет ни слова.

- На протяжении жизни Шекспир успел сменить множество профессий. Он охранял конюшню в театре, в качестве актера выходил на сцену, был одним из соучредителей и главным постановщиком «Глобуса». Кроме этого занимался ростовщичеством, варил пиво и даже сдавал в аренду жилье.

- Существует версия, по которой был некий неизвестный писатель, который использовал Шекспира в качестве подставного лица. В Британской энциклопедии написано, что автором пьес, подписанных от имени Шекспира, мог стать граф Эдуард де Вер. Некоторые приписывают авторство произведений Уильяма лорду Фрэнсису Бэкону и даже королеве Елизавете I.

- Благодаря поэтическому слогу драматурга сформировалась современная английская грамматика, обогатилась литературная речь жителей туманного Альбиона. В ней часто встречаются фразы, взятые из произведений великого Шекспира. После себя поэт оставил огромное наследие – свыше 1700 новых слов.

Цитаты великого драматурга

В популярных фразах поэта и драматурга встречаются настоящие философские выражения, причем очень лаконичные и точные. В основном, они касаются любовной сферы.

Каждый читающий эти крылатые выражения находит именно то, что касается лично его. Классик призывал не судить других за грехи, лучше обратить внимание на свои, тогда и до чужих не будет дела.

Труды

Трагедии

- Ромео и Джульетта

- Кориолан

- Тит Андроник

- Тимон Афинский

- Юлий Цезарь

- Макбет

- Гамлет

- Троил и Крессида

- Король Лир

- Отелло

- Антоний и Клеопатра

- Цимбелин

Поэмы

- Сонеты Уильяма Шекспира

- Венера и Адонис

- Обесчещенная Лукреция

- Страстный пилигрим

- Феникс и голубка

- Жалоба влюблённой

Комедии

- Всё хорошо, что хорошо кончается

- Как вам это понравится

- Комедия ошибок

- Бесплодные усилия любви

- Мера за меру

- Венецианский купец

- Виндзорские насмешницы

- Сон в летнюю ночь

- Много шума из ничего

- Перикл

- Укрощение строптивой

- Буря

- Двенадцатая ночь

- Два веронца

- Два знатных родича

- Зимняя сказка

Ссылки

- Страница в Википедии

Для нас важна актуальность и достоверность информации. Если вы обнаружили ошибку или неточность, пожалуйста, сообщите нам. Выделите ошибку и нажмите сочетание клавиш Ctrl+Enter.

Биография Шекспира

23 Апреля 1564 – 23 Апреля 1616 гг. (52 года)

4.1

Средняя оценка: 4.1

Всего получено оценок: 3910.

Уильям Шекспир (1564–1616) – всемирно известный драматург, поэт и писатель. Многие произведения Шекспира переведены на русский язык. Уильям Шекспир, биография которого содержит много тайн и загадок, является автором многих пьес, таких, как «Гамлет», «Ромео и Джульетта», «Отелло» и другие.

Опыт работы учителем русского языка и литературы — 27 лет.

Детские годы

Не сохранилась точная дата появления на свет будущего талантливого писателя. Считают, что он родился в Стратфорд-на-Эйвоне в апреле 1564 года. Доподлинно известно, что 26 апреля он был окрещён в местной церкви. Его детство прошло в многодетной состоятельной семье, он был третьим ребёнком среди семи братьев и сестёр.

Юношеская пора

Исследователи жизни и творчества Шекспира предполагают, что своё образование он получал сначала в грамматической школе Стратфорда, а потом продолжал обучение в школе короля Эдуарда Шестого. В восемнадцатилетнем возрасте он обзаводится семьёй. Его избранницей становится девушка по имени Энн. В семье писателя было трое детей.

Жизнь в Лондоне

В 20-летнем возрасте Шекспир покидает родной город, перебирается в Лондон. Там его жизнь складывается нелегко: чтобы заработать средства, он вынужден соглашаться на любую работу в театре. Затем ему доверяют играть небольшие роли. В 1603 году на сцене театра появляются его пьесы и Шекспир становится совладельцем труппы под названием «Слуги короля». Позже театр получает название «Глобус», перебирается в новое здание. Материальное состояние Уильяма Шекспира становится гораздо лучше.

Литературная деятельность

Первая книга писателя была издана в 1594 году. Она принесла ему успех, деньги и признание. Несмотря на это, писатель продолжает работу в театре.

Литературное творчество Шекспира можно условно разделить на четыре периода.

На раннем этапе он создаёт комедии и поэмы. В это время им написаны такие произведения, как «Два веронца», «Укрощение строптивой», «Комедия ошибок».

Позже появляются романтические произведения: «Сон в летнюю ночь», «Венецианский купец».

Самые глубокие философские книги появляются в третьем периоде его творчества. Именно в эти годы Шекспир создаёт пьесы «Гамлет», «Отелло», «Король Лир».

Последние произведения мастера характеризуются отточенным слогом и изящным поэтическим мастерством. «Антоний и Клеопатра», «Кориолан» являются вершиной поэтического искусства.

Оценка критиков

Интересным фактом является оценка произведений Уильяма Шекспира критиками. Так Бернард Шоу считал Шекспира устаревшим писателем по сравнению с Ибсеном. Лев Толстой неоднократно выражал сомнение в драматургическом таланте Шекспира. И всё-таки талант и гениальность великого классика – неоспоримый факт. Как говорил известный поэт Т. С. Элиот: «Пьесы Шекспира всегда будут современными».

В рамках краткой биографии Шекспира невозможно подробно рассказать о жизни писателя и проанализировать его произведения. Для того чтобы оценить личность и творческое наследие, необходимо читать произведения и знакомиться с трудами литературоведов о жизни и творчестве Уильяма Шекспира.

Хронологическая таблица

Другие варианты биографии

Более сжатая для доклада или сообщения в классе

Вариант 2

Интересные факты

- Будущий поэт появился на свет в небольшом английском городе Стратфорде, расположенном на реке Эйвон. Событие это произошло в семье Джона Шекспира и Мари Арден, которые принадлежали к ограниченному числу состоятельных граждан. Глава семейства зарабатывал на хлеб изготовлением перчаток. Его безмерно уважали и несколько раз приглашали в совет правления города.

Все интересные факты из жизни Шекспира

Тест по биографии

После прочтения биографии попробуйте пройти тест:

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

София Менглебей

9/12

-

Андрей Бекетов

8/12

-

Нурдана Нурбек-Кызы

11/12

-

Fatima Soldatbekova

10/12

-

Максим Николаев

9/12

-

Захар Одырейко

11/12

-

Любовь Савченко

12/12

-

Tatyana Yartseva

11/12

-

Наталья Разживина

8/12

-

Вафина Наталия

10/12

Оценка по биографии

4.1

Средняя оценка: 4.1

Всего получено оценок: 3910.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Национальная гордость Англии, один из лучших поэтов в мире – так говорят об этом авторе.

Уильям Шекспир (William Shakespeare, англ.) – знаменитый британский поэт и драматург, талант которого признан критиками и ценителями поэзии во всем мире.

Произведения автора переведены на множество языков. Некоторые литературные шедевры поэта включены в школьную программу. Их в обязательном порядке изучают дети.

Кроме того, по пьесам Шекспира ставят спектакли во многих театрах мира. И доказано, что произведения английского автора выбирают для театральных постановок чаще, чем работы других драматургов.

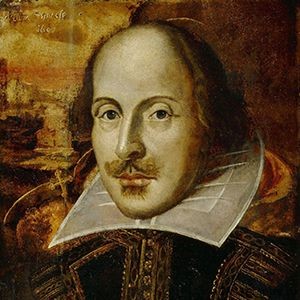

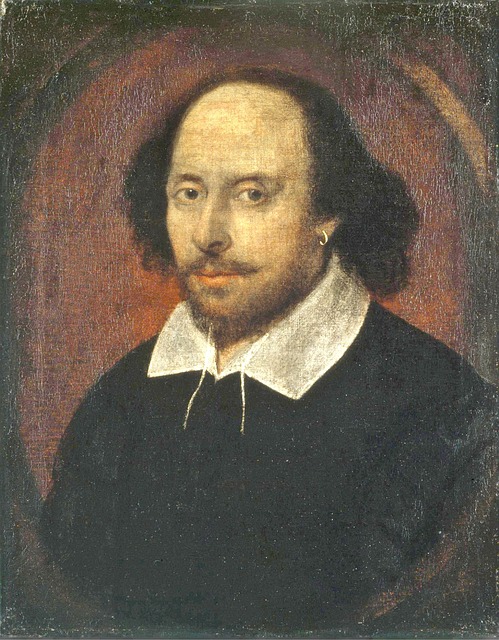

Фото У. Шекспира

Годы жизни и место рождения драматурга

Дата рождения Шекспира – 26 апреля 1564 года.

Дата смерти – 23 апреля 1616.

Город, где родился и вырос поэт − Стратфорд-апон-Эйвон.

Родился поэт в состоятельной семье. Его родители были уважаемыми людьми. Мать драматурга принадлежала к одной из старых саксонских семей. Отец был ремесленником, но при этом видным общественным деятелем. Он неоднократно занимал серьезные общественные должности – был членом муниципального собрания, главой городского совета. Интересный факт из биографии отца – он отказывался посещать церковь, за что ему приходилось платить немалые штрафы.

Семья и детские годы

Семья у Шекспира была большая. Кроме Уильяма, было еще 7 детей. Но, благодаря тому, что торговые предприятия отца приносили неплохую прибыль, у будущего поэта была возможность посещать местную школу и получить базовое образование.

Основным предметом в школе была латынь, но также ученикам преподавали основы риторики и грамматики. В учебную программу входило изучение великих философов и поэтов. И это наложило отпечаток на творчество Шекспира.

Работать Вильям Шекспир начал рано. К тому времени, когда ему исполнилось 16 лет, дела отца шли уже не так блестяще, как ранее. Поэтому ему пришлось начать работать, чтобы помогать семье.

Кем работал будущий поэт, достоверно неизвестно. По разным источникам он мог быть учителем в деревенской школе или подмастерьем в небольшой лавке.

Личная жизнь поэта

Женился драматург, когда ему исполнилось 18 лет. Это произошло в 1582 году.

Его избранницей стала Энн Хатауэй из семьи землевладельцев. Супруга была старше Вильяма на восемь лет.

На момент свадьбы Хатауэй была беременна, и в 1583 году у Шекспира родилась первая дочь, которую назвали Сьюзен. Через два года у пары родились двойняшки – мальчик и девочка, которых назвали Хемнет и Джудит.

К сожалению, Хемнет прожил всего 11 лет и скончался в августе 1596 года (точная дата смерти неизвестна).

Биография Шекспира имеет немало белых пятен. Историки до сих пор не могут восстановить ее полностью.

Так, известно, что из города, где родился Шекспир, он через 3 года после свадьбы переехал в Лондон. Но причины этого переезда достоверно неизвестны. Некоторые исследователи утверждают, что это произошло из-за того, что будущий драматург бежал из родного города из-за гнева помещика, который выяснил, что Вильям занимается браконьерством на его угодьях.

Начало творческой карьеры

С переезда в Лондон началась новая глава биографии Уильяма Шекспира. Но и про эти годы жизни поэта достоверно известно далеко не все.

Считается, что сразу после приезда он устроился работать в театр на самую низшую должность – в его обязанность входило присматривать за лошадьми господ, посещающих храм Мельпомены.

Есть информация, что он занимался не лошадьми, а переработкой старых пьес на современный лад. Также имеются предположения, что Шекспир попытался стать актером, но потерпел неудачу.

Что из краткой биографии поэта известно достоверно – Уильям входил в театральную труппу «Слуги лорда-камергера». И он был не только актером, выступавшим на сцене, но и одним из соучредителей.

Также он писал для труппы пьесы. Поставленные на основе произведений автора спектакли пользовались невероятным успехом у лондонских жителей из всех слоев общества – аристократии, простых горожан.

Благодаря быстрорастущей популярности к поэту пришел и финансовый успех. В 1599 год участники труппы основали свой театр под названием «Глобус», который находился на левом берегу реки Темза. Еще через несколько лет (1608 г.) ими был выкуплен театр «Блэкфрайер».

С этого времени поэт стал считаться одним из самых богатых людей Лондона.

Судя по отчетам, свидетельствующим о покупке недвижимости, финансовое благополучие действительно пришло к драматургу после вхождения в труппу «Слуги лорда-камергера». В качестве доказательства этого приводится тот факт из биографии автора, что он в 1597 году приобрел один из самых больших по площади домов в Стратфорде.

Что за годы творчества написал Шекспир

За годы творческой деятельности из-под пера автора вышло немало литературных шедевров. Но британский поэт не зацикливался на каком-то одном жанре.

Его произведения можно условно разделить на 4 категории. Что написал Шекспир:

- легкие комедии;

- античные пьесы и сонеты;

- трагедии;

- драматические сказки.

Первые литературные произведения Шекспира отличались легкостью, обилием иронии. Но с течением времени его пьесы становятся более серьезными, глубокими, содержательными.

В XVI веке в Англии были популярны произведения, в основе которых лежит исторический сюжет. И Шекспир не упустил этот момент.

В начале 1590-х годов он создал пьесы «Ричард III» и «Генрих VI» в трех частях. Это были одни из его ранних работ. И их хорошо встретила местная публика.

К сожалению, с датированием выхода произведений британского автора у ученых были и до сих пор возникают сложности. Слишком мало сохранилось достоверных источников, чтобы определить точный год выхода работ драматурга. Но исследователи, изучающие, жизнь и творчество великого мастера классической английской литературы, все же постарались выделить годы, в которые могла быть написано та или иная работа.

Например, трагедию «Тит Андроник», пьесы «Два венца» и «Укрощение строптивой», комедию «Комедия ошибок» принято относить к периоду раннего творчества Шекспира.

Середина 1590-х – годы изменения стиля работ автора. Оставив в прошлом легкие и ироничные комедии, он начинает писать романтические произведения.

Именно в это время появляются такие шедевры, как «Сон в летнюю ночь», «Венецианский купец», «Много шума из ничего», «Как вам это понравится», «Двенадцатая ночь».

В начале XVII века драматург создает несколько ставших знаменитыми пьес и трагедий. В это время свет увидели «Мера за меру», «Все хорошо, что хорошо кончается», «Троил и Крессида». Также в этот период Шекспир написал ставшего на весь мир знаменитого «Гамлета», «Отелло».

Всего за годы жизни Шекспиром было написано 154 сонета, 38 пьес, 3 эпитафии, 4 поэмы.

Список всех произведений

Трагедии:

- Макбет;

- Ромео и Джульетта;

- Король Лир;

- Кориолан;

- Король Лир;

- Отелло;

- Тит Андроник;

- Антоний и Клеопатра;

- Гамлет;

- Тимон Афинский;

- Троил и Крессида;

- Юлий Цезарь;

- Цимбелин.

Комедии:

- Как вам это понравится;

- Комедия ошибок;

- Буря;

- Мера за меру;

- Зимняя сказка;

- Два веронца;

- Много шума из ничего;

- Бесплодные усилия любви;

- Венецианский купец;

- Все хорошо, что хорошо кончается;

- Сон в летнюю ночь;

- Виндзорские насмешницы;

- Укрощение строптивой;

- Перикл;

- Двенадцатая ночь;

- Два знатных родича.

Поэмы:

- Жалоба влюбленной;

- Венера и Адонис;

- Сонеты Уильяма Шекспира;

- Феникс и голубка;

- Обесчещенная Лукреция;

- Страстный пилигрим.

Исторические хроники:

- Ричард II;

- Ричард III;

- Генрих IV, часть 1, 2;

- Генрих V;

- Генрих VI, часть 1, 2, 3;

- Генрих VIII;

- Король Иоанн.

Последние годы жизни и кончина поэта

Последние годы жизни английский поэт провел в своем родном городе. По предположениям историков, возвращение из Лондона произошло по причине вспышки чумы, из которой театрам приходилось останавливать деятельность, а у актеров резко снизилось количество работы.

Но Шекспир не осел полностью в родном городе, ему часто приходилось ездить в Лондон по делам.

За 3 – 5 лет до смерти Шекспир перестал заниматься творчеством. Кроме того, по мнению ученых, в 1612 – 1613 гг. драматург был чем-то серьезно болен. Такие выводы исследователи сделали при внимательном изучении почерка автора, который незадолго до его смерти значительно изменился.

Жена Шекспира пережила его на 7 лет, Энн Хатауэй скончалась в 1623 году.

Некоторое замешательство исследователей жизни драматурга вызвало оставленное им завещание. Согласно наследному документу, большую часть имущества получала старшая дочь Сьюзен и ее прямые потомки. Но удивление вызвало не то, что Уильям решил оставить почти все состояние дочери, а то, что он передал по наследству своей жене.

Драматург завещал Энн Хатауэй «мою вторую по качеству кровать». Эта формулировка вызвала среди историков немалые споры. Некоторые ученые считают, что таким заявлением поэт оскорбил свою жену. У других – мнение иное, противоположное. Некоторые историки считают, что драматург, когда составлял завещание, имел в виду супружеское ложе, поэтому причин говорить об оскорблении жены нет.

Похоронен Шекспир в церкви Святой Троицы в Стратфорде.

На надгробии поэта нанесена эпитафия, которая в переводе на русский язык звучит так:

Друг, ради Господа, не рой

Останков, взятых сей землей;

Нетронувший блажен в веках,

И проклят — тронувший мой прах.

Перевод выполнен Александром Величанским.

Репутация Шекспира и влияние его творчества на культуру

Хотя всемирно прославился Шекспир уже после своей смерти, при жизни его произведения находили отклик не только у зрителей, но и у критиков.

Так, Френсис Мерис (писатель-священнослужитель) отзывается о поэте как о самом превосходном английском писателе в жанрах комедии и трагедии. Немало похвал получает драматург у критиков XVIII века, а к 1800 году за ним надежно закрепляется звание национального английского поэта.

Еще позже, в XIX веке, известность драматурга выходит за пределы Англии. Восхищение талантом У. Шекспира высказывают такие знаменитые авторы, как Гете, Вольтер и Гюго.

Но не все готовы согласиться с тем, что Шекспир – великий поэт. Есть критики, которые высказывали о его творчестве негативное мнение.

Одним из них был русский писатель Лев Толстой. Он подверг критике талант британского поэта как драматурга.

Некоторые критики высказывают свое неприятие таланта поэта из-за того, что часть из своих знаменитых произведений он писал в соавторстве с другими литературными деятелями.

Есть даже гипотеза, что Шекспир – это не один человек, а псевдоним, под которым создавали пьесы несколько писателей. На чем базируется подобное заявление – не сохранилось ни одной рукописи, которая была бы написана рукой самого драматурга.

Кроме того, противников Шекспира удивляет его богатый словарный запас, хотя не сохранилось источников, подтверждающих получения им серьезного образования.

Что бы ни говорили о Шекспире критики, он уже несколько веков – один из самых популярных поэтов не только Англии, но и мира.

Практически в каждом театре ставят хотя бы одно его произведение. И это неудивительно. Творчество автора оказало серьезное воздействие на культуру и искусство. Под воздействием таланта Шекспира в мире появлялись новые произведения, герои которых имели те же черты, что и персонажи пьес драматурга.

По подсчетам ученых, примерно 20 тысяч музыкальных произведений связаны с творениями английского поэта. Кроме того, считается, что слог языка драматурга послужил основой для формирования современного английского языка.

Внешность драматурга

Изображение с гравюры

О том, насколько достоверными можно назвать растиражированные фото Шекспира, тоже идут споры между специалистами. Дело в том, что точных описаний внешности драматурга не сохранилось. Поэтому отражающим истинный облик поэта принято считать Друшаутский портрет (гравюра), созданный Мартином Друшаутом.

Шекспир – один из авторов, успех которого трудно повторить, хотя его литературная деятельность продолжалась всего 20 лет. Но, в каком веке жил Шекспир? В 16, а это значит, что уже целых 500 лет люди читают его произведения и находят их интересными.

Роль и место в литературе

Роль и место в литературе

Творчество Уильяма Шекспира – это значимая страница в большой книге мировой Литературы. Созданные драматургом образы пополнили ряды вечных художественных образов. Гамлет, Ромео и Джульетта, Отелло, Король Лир – герои, которые давно вышли за пределы сочинений Шекспира и до сих пор живут в искусстве.

Происхождение

Дом в Стратфорде, где родился Шекспир. Сейчас музей

Великий драматург Уильям Шекспир появился на свет в 1564 году. Точные данные о дне рождения не сохранились. Город Стратфорд-апон-Эйвон (Англия) считается местом его рождения.

Отец – Джон Шекспир, зажиточный ремесленник. Он принимал активное участие в жизни города, был не единожды избранным на разные общественные должности. Так же о нем известно, что он не ходил на церковные собрания, за что платил большие штрафы. Это послужило поводом предположить, что Джон Шекспир был тайным католиком.

Мать – Мэри Шекспир (в девичестве Арден), представительница одного из старейших саксонских родов. Вышла замуж за Джона и родила ему восьмерых детей. Уильям стал третьим.

Детство будущего драматурга прошло в состоятельной многодетной семье.

Образование

Грамматическая школа

Принято считать, что начальное образование Шекспир получил в Стратфордской грамматической школе. Там делали уклон на изучение латыни, учитель даже писал стихи по латыни. Есть версия, что продолжил учебу Вильям в школе короля Эдуарда Шестого. К сожалению, школьные журналы этой школы не сохранились, поэтому нельзя это утверждать.

Юношеская пора

Шекспир обзаводится собственной семьей в довольно юном возрасте – в 18 лет. Его избранницей стала Энн Хатауэй, дочь землевладельца. Девушка была старше Уильяма на 8 лет. В 1582 году состоялась их женитьба. На момент регистрации брака Энн уже ждала ребенка.

Когда Уильяму было 20 лет, он вместе с семьей переезжает в Лондон. Молодой мужчина устраивается разнорабочим в театр. Чтобы нормально жить, ему приходилось соглашаться там на любую работу. Со временем, заметив рвение молодого Уильяма, ему все же стали доверять играть небольшие роли.

Творчество

Литературный дебют Шекспира состоялся в 1594 году, когда была издана его первая книга. С этого момента он становится известным. Но, несмотря на успех, Уильям продолжает работать в театре.

Семья Шекспира

В 1599 году Вильям Шекспир становится одним из совладельцев театра «Глобус».

Творчество Шекспира принято делить на четыре периода:

- Первый – ранний период. В это время он создает свои первые комедии и поэмы. Известными стали такие сочинения: «Комедия ошибок», «Укрощение строптивой» и т. д.

- Второй – романтический период. Наиболее значимые произведения этого периода – «Венецианский купец», «Сон в летнюю ночь».

- Третий – философский период. Именно в этот период рождаются самые глубокие произведения автора, такие как: «Отелло» и «Гамлет».

- Четвертый – вершина творчества. Автор уже был на этот момент опытным мастером слова и создавал такие изящные произведения, как «Антоний и Клеопатра».

Основные произведения

Рождение шедевра

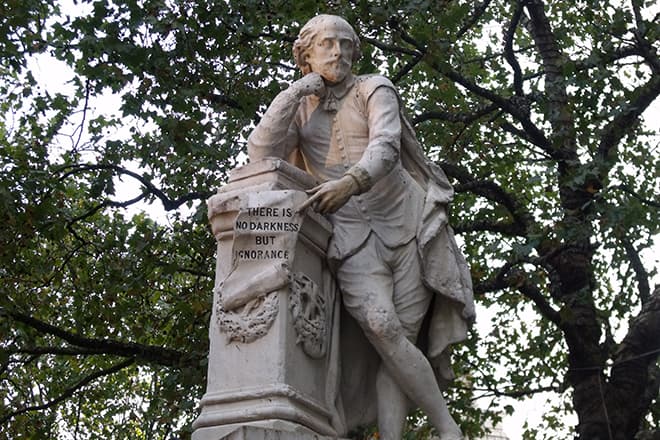

Памятник поэту

К основным произведениям Шекспира относят такие его трагедии: «Гамлет», «Ромео и Джульетта», «Король Лир», «Отелло». Их читатели изучают еще со школьных лет. Именно эти произведения до сих пор на пике популярности в театре, музыке и кино.

Чем же они так привлекают сердца и умы поклонников? «Гамлет» заставляет нас задуматься о смысле человеческой жизни, о сложных противоречивых моментах, о том, что порой сложно понять: «быть или не быть»? А история Ромео и Джульетты навсегда останется примером настоящей любви!

Последние годы

Есть мнение, что последние годы жизни драматург проводил в родном городе, Стратфорде. Скорее всего, его мучила какая-то болезнь, потому что на всех его последних документах стоит неразборчивая подпись. После 1613 года автор не создает пьес. В 1616 году его не стало.

Хронологическая таблица

| Год (годы) | Событие |

| 1564 | Год рождения Уильяма Шекспира |

| 1571-1578 | Годы обучения в Стратфордской грамматической школе |

| 1582 | Брак с Энн Хатауэй |

| 1584(5) | Переезд в Лондон |

| Конец 80-ых годов | Начало работы в театре |

| 1594 | Выход первой книги |

| 1599 | Открылся театр «Глобус» |

| 1601-1602 | Работа над трагедией «Гамлет» |

| 1605 | Работа над трагедией «Король Лир» |

| 1613 | Переезд в родной город Стратфорд |

| 1616 | Не стало драматурга |

Интересные факты

- Кроме литературного таланта, у Шекспира была способность к иностранным языкам и отменная память. Он знал французский, итальянский и испанский языки.

- Шекспир был человеком с разносторонними интересами: варил пиво, занимался арендой квартир.

- Точно неизвестно, кем был Вильям Шекспир: католиком или протестантом. Он это скрывал, как и его отец.

Музей писателя

Дом, в котором провел детство Уильям Шекспир, сейчас является музеем и одним из достояний Великой Британии. Дом-музей находится в городе Стратфорде на улице Хенли.

Ирина Зарицкая | Просмотров: 9.9k

Уильям Шекспир – один из самых великих драматургов и поэтов в истории. Его произведения изучают во всех школах мира, а пьесы переведены на все основные языки и ставятся на сценах театров чаще, чем пьесы каких-либо других авторов.

Работы Шекспира состоят из 38 пьес, 154 сонетов, 4 поэм и 3 эпитафий. Шекспир именуется национальным поэтом Англии, а его фамилия с английского языка переводится как «потрясающий копьём».

В биографии Шекспира много темных пятен, которые едва ли когда-то прояснятся. Однако это делает фигуру величайшего драматурга еще более загадочной, таинственной и привлекательной.

Итак, вашему вниманию предлагается биография Уильяма Шекспира. К слову, самые интересные факты про Шекспира читайте здесь.

Биография Шекспира

Биографы Уильяма Шекспира до сих пор спорят об истинной дате его рождения. Считается, что он родился 23 апреля 1564 г. в небольшом английском городе Стратфорд-на-Эйвоне.

Однако эта дата точно соответствует дню его смерти, отчего ее корректность еще больше подвергается сомнению.

Более того, 23 апреля отмечается день святого Георгия, покровителя Англии, поэтому вполне возможно, что благодарные потомки попросту приурочили к этому дню рождение величайшего национального поэта.

Любопытно происхождение фамилии «Шекспир», которая переводится с английского языка как «потрясающий копьём».

Детство и юность

Уильям Шекспир рос в обеспеченной семье. Его отец, Джон, занимался изготовлением перчаток. Благодаря этому он нажил неплохое состояние и неоднократно избирался на разные государственные должности.

Интересен факт, что отец Шекспира намеренно не ходил в храмы во время богослужений официальной Англиканской церкви, вследствие чего ему приходилось платить большие штрафы. Биографы считают, что возможно он был тайным католиком.

Мать Шекспира, Мэри Арден, являлась урожденной саксонкой, принадлежавшей к древнему роду. Кроме Уильяма в семье Шекспиров родилось еще 7 детей.

Образование

О том где учился Уильям Шекспир также точно неизвестно. Считается, что он ходил в грамматическую школу, находящуюся в его родном городе. Он хорошо учился и глубоко изучал латинский язык.

Существует мнение, что будущий драматург продолжил учебу в королевской школе, где ему удалось познакомиться с трудами древних римских поэтов.

Так или иначе, но судя по произведениям Шекспира можно смело утверждать, что он был чрезвычайно образованным человеком.

Личная жизнь

В 18 лет в биографии Шекспира произошло знаковое событие. Он женился на дочке землевладельца Энн Хатауэй, с которой жил по соседству. Интересен факт, что избранница Уильяма была старше его на 8 лет.

Исследователи Шекспира считают, что этот брак был вынужденным, по причине беременности Энн. Через несколько месяцев после женитьбы у них родилась дочка Сьюзен, а через 2 года у пары появились двойняшки – мальчик Хемнет, и девочка Джудит.

При этом стоит заметить, что ряд биографов Шекспира считают, что он вообще никогда не был женат.

Существует даже предположение, будто драматург имел отношения с мужчинами, однако такая версия не подтверждена никакими серьезными фактами.

Театральная карьера в Лондоне

Любопытно, что о семи годах (1585-1592) биографии Шекспира вообще ничего не известно. Только в 1592 г. появляется первое свидетельство о том, что он занимается театральной деятельностью.

Поэтому достоверно узнать о том, в каком возрасте Шекспир начал писать свои пьесы – не представляется возможным.

На сегодняшний день известно, что он состоял в труппе «Слуги лорда-камергера», будучи одним из ее соучредителей. Шекспир писал для труппы пьесы, и сам же выступал на сцене в качестве актера.

Постановки имели невероятный успех у публики, которая с интересом смотрела на игру артистов. Интересно, что на спектакли ходили не только простые люди, но и вся королевская знать.

Благодаря этому актеры стали очень хорошо зарабатывать и смогли построить собственный театр, который был назван «Глобус».

Спустя несколько лет они выкупили театр «Блэкфрайер», а Уильям Шекспир стал одним из самых богатых людей Лондона.

Литературная деятельность

Принято считать, что Шекспир одновременно занимался, как актерской, так и литературной деятельностью. Его первое произведение было опубликовано в 1594 г.

Творческий период драматурга можно условно разделить на 4 части:

- Написание легких комедий, «трагедий ужаса», хроник и двух поэм. В это время его произведения были еще достаточно сырыми и отличались наличием большого количества персонажей.

- Появление зрелой драматургии, хроник с драматическим повествованием, античных пьес и сонетов.

- Написание античных и мрачных трагедий.

- Сочинение драматических сказок.

Драматургия

Уильям Шекспир по праву считается самым великим драматургом всех времен и народов. В конце 16 века многие литераторы стремились писать исторические драмы.

В связи с этим в биографии Шекспира появились пьесы «Ричард 3» и «Генрих 6».

Как уже говорилось, первые произведения Шекспира отличались легкостью и ироничностью. В поздний период его пьесы становятся уже более интересными и содержательными.

Одними из самых известных его трагедий являются «Гамлет», «Отелло» и «Король Лир».

С каждым годом его произведения становились все лучше и содержательнее. Ему удавалось в тонкостях передавать детали разных исторических событий, а также мастерски описывать характеры своих героев.

Шекспировские драмы «Антоний и Клеопатра» и «Кориолан» считаются эталоном совершенства.

Интересно, что некоторые биографы Шекспира убеждены в том, что несколько своих пьес он написал в соавторстве с другими писателями.

Но даже если предположить, что это действительно так было, в этом нет ничего удивительного, поскольку такая практика была вполне распространенной в то время.

Поэмы и сонеты

В 1593 г. в Англии свирепствовала эпидемия чумы, унесшая десятки тысяч жизней. На протяжении 2 лет люди умирали в страшных мучениях думая, что их постигла кара Божья. Само собой разумеется, что театральное искусство в то время было не очень актуальным.

В связи с этим Уильям Шекспир какое-то время не участвовал в спектаклях. Вместо этого он много читал. После прочтения «Метаморфоз» Овидия из-под его пера вышло 2 эротических поэмы.

Однако больше всего драматург прославился, как автор сонетов. За свою биографию Шекспир написал 154 сонета, каждый из которых состоит из 14 строк.

Стиль Шекспира

Изначально творчество Шекспира сильно не отличалась от литераторов того времени.

Однако почувствовав уверенность в собственных силах, ему захотелось достичь больших успехов на писательском поприще, поэтому он часто экспериментировал с различными стилями написания пьес и сонетов.

В своих произведениях Уильям Шекспир нередко прибегал к так называемым анжамбеманам, когда автор использует нестандартные конструкции и меняет длину предложений.

Кроме этого, он неоднократно предлагал читателю самостоятельно додумывать окончание той или иной фразы.

Критика

Бесспорно, Шекспир считается литературным гением мирового значения. Его творчеством восхищались такие русские поэты и писатели, как Пушкин, Лермонтов, Тургенев, Достоевский, Некрасов и многие другие.

Интересен факт, что при жизни талант драматурга не был оценен по достоинству. Лишь столетие спустя Шекспир станет национальным героем Англии, после чего его книги начнут переводить на все языки мира.

Однако были и те, кто скептически относился к творчеству английского писателя. Одним из самых авторитетных его критиков являлся Лев Толстой. Он публично критиковал способности Шекспира, как драматурга.

При этом великий русский драматург Антон Чехов называл Шекспира «объективным поэтом» и очень восхищался им. Станиславский считал Чехова продолжателем шекспировских традиций.

Смерть

В последние годы жизни Уильям Шекспир жил в родном городе, где продолжал писать пьесы. Чем он занимался еще невозможно сказать по причине отсутствия какой-либо достоверной исторической информации.

Биографы, изучающие рукописи Шекспира, отмечали, что в конце жизни его почерк стал более размашистым и неуверенным. На основании этого некоторые из них выдвинули версию о том, что драматург был серьезно болен.

23 апреля 1616 г. Уильям Шекспир умер в возрасте 52 лет.

После смерти все его имущество перешло дочерям. Интересен факт, что на том месте, где Шекспир прожил свои последние годы, ему был позже установлен памятник.

Если вам понравилась биография Шекспира – поделитесь ею в социальных сетях. Если же вам нравятся биографии великих людей вообще, и интересные истории из их жизни в частности – подписывайтесь на сайт InteresnyeFakty.org. С нами всегда интересно!

Понравился пост? Нажми любую кнопку:

Уильям Шекспир (1564-1616) – великий английский поэт и драматург, входит в число лучших писателей мира, национальный поэт Англии. Произведения Шекспира имеют переводы на все основные языки мира и наибольшее количество театральных постановок по сравнению со всеми другими драматургами.

Рождение и семья

Уильям родился в 1564 году в небольшом местечке Стратфорд-апон-Эйвон. Точно неизвестен день его рождения, есть только запись о крещении малыша, которая прошла 26 апреля. Так как в то время младенцев крестили на третий день после рождения, предполагается, что поэт появился на свет 23 апреля.

Отец будущего гения, Джон Шекспир (1530-1601), – зажиточный горожанин, занимался торговлей мясом, шерстью и зерном, имел перчаточное ремесло, позднее увлёкся политикой. Он часто избирался на значимые в обществе должности: в 1565 году олдерменом (членом муниципального собрания), в 1568 году бальи (мэром города). В Стратфорде отец имел много домов, так что семья далеко не бедствовала. Отец никогда не ходил на службу в церковь, за это на него возлагались немалые штрафы, предполагается, что он тайно исповедовал католицизм.

Мама поэта, Мэри Арден (1537-1608), вышла из старейшего дворянского рода Саксонии. Уильям был третьим из восьми детей, родившихся в семье Шекспиров.

Учёба

Маленький Шекспир посещал местную «грамматическую» школу, где занимался риторикой, латынью и грамматикой. Дети в подлиннике знакомились с произведениями знаменитых древних мыслителей и поэтов: Сенеки, Виргилия, Цицерона, Горация, Овидия. Это раннее изучение лучших умов отложило отпечаток на дальнейшее творчество Уильяма.

Провинциальный городок Стратфорд был маленький, все люди знали там друг друга в лицо, общались независимо от сословия. Шекспир играл с детьми обычных горожан и знакомился с их жизнью. Он познавал фольклор и впоследствии списывал со стратфордских жителей многих героев своих произведений. В его пьесах появятся хитрые слуги, высокомерные вельможи, простые люди, страдающие из-за рамок условностей, все эти образы он черпал в детских воспоминаниях.

Молодые годы

Шекспир был очень трудолюбивым, тем более что жизнь заставила его рано начать работать. Когда Уильяму было 16 лет, отец совсем запутался в своих торговых делах, обанкротился и не мог содержать семью. Будущий поэт пробовал себя в качестве сельского учителя и подмастерья в мясной лавке. Уже тогда проявлялась его творческая натура, перед тем, как забить животное, он произносил торжественную речь.

Когда Шекспиру было 18 лет, он сочетался браком с 26-летней Энн Хатауэй. Отец Энн был местным землевладельцем, на момент бракосочетания девушка ждала ребёнка. В 1583 году Энн родила девочку Сьюзен, в 1585 году в семье появилась двойня – девочка Джудит и мальчик Хемнет (умер в 11 лет).

Спустя три года после женитьбы семья уехала в Лондон, потому что Уильяму пришлось скрываться от местного помещика Томаса Люси. В те времена считалось особой доблестью убить оленя в поместье местного богача. Этим занимался Шекспир, и Томас начал его преследование.

Творчество

В английской столице Шекспир устроился работать в театр. Сначала его работа заключалась в присмотре за лошадьми посетителей театра. Потом ему доверили «штопать пьесы», на современный лад он был рерайтером, то есть переделывал старые произведения для новых спектаклей. Пробовал играть на сцене, но знаменитого актёра из него не вышло.

Со временем Уильяму предложили работу театрального драматурга. Его комедии и трагедии играла труппа «Слуги лорда-камергера», которая занимала одну из ведущих позиций среди театральных лондонских коллективов. В 1594 году Уильям стал совладельцем этой труппы. В 1603 году после кончины королевы Елизаветы коллектив переименовали в «Слуги Короля».

В 1599 году на южном берегу реки Темзы Уильям с партнёрами выстроил новый театр, получивший название «Глобус». К 1608 году относится приобретение закрытого театра «Блэкфрайерс». Шекспир стал довольно состоятельным человеком и приобрёл дом Нью-Плэйс, в родном городке Стратфорде это строение было вторым по величине.

С 1589 по 1613 годы Уильям сочинил основную часть своих произведений. Его раннее творчество состоит в большей степени из хроник и комедий:

- «Всё хорошо, что хорошо кончается»;

- «Виндзорские насмешницы»;

- «Комедия ошибок»;

- «Много шума из ничего»;

- «Венецианский купец»;

- «Двенадцатая ночь»;

- «Сон в летнюю ночь»;

- «Укрощение строптивой».

Позднее у драматурга наступил период трагедий:

- «Ромео и Джульетта»;

- «Юлий Цезарь»;

- «Гамлет»;

- «Отелло»;

- «Король Лир»;

- «Антоний и Клеопатра».

Всего Шекспиром написано 4 поэмы, 3 эпитафии, 154 сонета и 38 пьес.

Смерть и наследие

Начиная с 1613 года, Уильям больше не писал, а три последние его произведения были созданы уже в творческом союзе с другим автором.

Шекспир умер 3 мая 1616 года. Супруга пережила его на семь лет.

Свою недвижимость поэт завещал старшей дочке Сьюзен, а после неё уже прямым наследникам. Сьюзен в 1607 году сочеталась браком с Джоном Холлом, у них родилась девочка Элизабет, которая потом два раза выходила замуж, но оба брака были бездетными.

Младшая дочь Шекспира Джудит вступила в брак с виноделом Томасом Куини вскоре после смерти отца. У них было трое детей, но все они умерли, не успев создать семьи и родить наследников.

Всё творческое наследие великого драматурга досталось благодарным потомкам. В мире установлено огромное количество монументов, памятников и статуй, посвящённых Уильяму. Сам он захоронен в церкви Святой Троицы города Стратфорда.

Биография

Великий драматург Англии эпохи Ренессанса, национальный поэт, получивший мировое признание, Уильям Шекспир появился на свет в городке Стратфорде, который находится севернее Лондона. В истории сохранились только сведения о его крещении 26 апреля 1564 года.

Родителями мальчика были Джон Шекспир и Мэри Арден. Они входили в число зажиточных граждан города. Отец мальчика помимо земледелия занимался изготовлением перчаток, а также мелким ростовщичеством. Его несколько раз выбирали в совет правления города, он был констеблем и даже мэром.

По некоторым данным, Джон принадлежал к католическому вероисповеданию, за что в конце жизни подвергся преследованиям, заставившим его распродать все свои земли. В течение своей жизни он выплачивал большие суммы протестантской церкви за непосещение службы. Мать Уильяма была урожденной саксонкой, она принадлежала к древней уважаемой фамилии. Мэри родила 8 детей, третьим из которых был Уильям.

В Стратфорде маленький Уильям Шекспир получил по тем временам хорошее образование. В детстве он поступил в грамматическую школу, где изучали латынь и древнегреческий язык. Для более глубокого и полного освоения древних языков предполагалось участие учеников в школьных постановках пьес на латыни.

По некоторым данным, помимо этого учебного заведения Уильям Шекспир в юношестве посещал ещё и королевскую школу, которая также находилась в родном городке. Там у него была возможность ознакомиться с древнеримскими поэтическими трудами.

Личная жизнь

В 18 лет у молодого Уильяма завязался роман с 26-летней дочерью соседа Энн Хатауэй, с которой они вскоре поженились. Причиной поспешной женитьбы стала беременность девушки. В те времена добрачные связи в Англии считались нормой, женитьба часто проходила после зачатия первенца. Единственным условием таких связей было обязательное венчание до рождения ребёнка. Когда в 1583 году у молодой четы родилась дочь Сьюзен, Уильям был счастлив. Всю жизнь он был особенно привязан к ней, даже после рождения через два года двойняшек сына Хемнета и второй дочери Джудит.

Больше в семье поэта детей не было, скорее всего из-за вторых тяжёлых родов его жены Энн. В 1596 году чета Шекспиров переживёт личную трагедию: во время эпидемии дизентерии умрёт их единственный наследник. После переезда Уильяма в Лондон его семья осталась в родном городке. Нечасто, но регулярно Уильям посещал своих родных.

О его личной жизни в Лондоне историки строят много загадок. Вполне возможно, что драматург жил один. Некоторые исследователи биографии поэта приписывают ему любовные связи, в том числе и с мужским полом. Но эта информация так и остаётся недоказанной.

Неизвестные семь лет

Уильям Шекспир — один из немногих авторов, о котором сведения собирались буквально по крупицам. Осталось очень мало прямых свидетельств о его жизни. В основном все сведения об Уильяме Шекспире извлекали из второстепенных источников, таких как высказывания современников или административные записи. Поэтому о семи годах после рождения его двойни и до первых упоминаний о его работе в Лондоне, исследователи строят загадки.

Шекспиру приписывают и службу у знатного землевладельца в качестве учителя, и работу в лондонских театрах суфлером, рабочим сцены и даже коневодом. Но по-настоящему достоверных сведений об этом периоде жизни поэта нет.

Лондонский период

В 1592 году в прессе появляется высказывание английского поэта Роберта Грина о творчестве молодого Уильяма. Это первое упоминание о Шекспире, как об авторе. Аристократ в своём памфлете постарался высмеять молодого драматурга, так как видел в нем сильного конкурента, но который, не отличался благородным происхождением и хорошим образованием. В это же время упоминается о первых постановках пьесы Шекспира «Генрих VI» в лондонском театре «Роза».

Это произведение было написано в духе популярного английского жанра хроники. Такой тип представлений был распространен в эпоху Возрождения в Англии, он носил эпический характер повествования, сцены и картины часто были не связаны между собой. Хроники были призваны воспевать государственность Англии в противовес феодальной раздробленности и междоусобным войнам.

Известно, что Уильям с 1594 года входит в крупное актерское сообщество «Слуги лорда-камергера» и становится вскоре его соучредителем. Постановки приносили большой успех, и труппа за короткое время настолько разбогатела, что позволила себе построить в течение следующих пяти лет знаменитое здание театра «Глобус». А к 1608 году театралы приобрели себе ещё и закрытое помещение, которое назвали «Блэкфрайерс».

Во многом успеху способствовало благоволение правителей Англии: Елизаветы I и её наследника Якова I, у которого театральный коллектив приобрёл себе разрешение на смену статуса. С 1603 года труппа получила название «Слуги Короля». Шекспир не только занимался написанием пьес, он также принимал активное участие в постановках своих произведений. В частности, сохранились сведения о том, что Уильям играл во всех своих пьесах главные роли.

Состояние

По некоторым свидетельствам, в частности, о сделанных покупках недвижимости Уильямом Шекспиром, он зарабатывал достаточно и был успешен в финансовых делах. Драматургу приписывают занятия ростовщичеством.

Благодаря своим накоплениям в уже 1597 году Уильям смог позволить себе купить просторный особняк в Стратфорде. Кроме того, Шекспир после смерти был сразу же захоронен в алтаре церкви Святой Троицы родного города. Такая честь была оказана ему не за особые заслуги, а за то, что он ещё при жизни заплатил положенную сумму за место своего погребения.

Периоды творчества

Великий драматург создал бессмертную сокровищницу, которая питает мировую культуру вот уже более пяти веков подряд. Сюжеты его пьес стали вдохновением не только для артистов драматических театров, но и для многих композиторов, а также для кинорежиссеров. За всю свою творческую жизнь Шекспир неоднократно менял характер написания своих произведений.

Первые его пьесы по своей структуре часто копировали популярные в то время жанры и сюжеты, такие как хроники, комедии Возрождения («Укрощение строптивой»), «трагедии ужаса» («Тит Андроник»). Это были громоздкие произведения с большим количеством героев и неестественным для восприятия слогом. На классических для того времени формах молодой Шекспир постигал азы написания драмы.

Вторая половина 90- х годов XVI столетия ознаменовалась появлением драматургически отточенных по форме и содержанию сочинений для театра. Поэт ищет новую форму, не отходя от заданных рамок ренессансной комедии и трагедии. Он наполняет старые изжившие формы новым содержанием. Так на свет появляется гениальная трагедия «Ромео и Джульетта», комедии «Сон в летнюю ночь», «Венецианский купец». Свежесть стиха в новых сочинениях Шекспира сочетается с необычным и запоминающимся сюжетом, что делает эти пьесы популярными у публики всех слоёв населения.

В это же время Шекспир создаёт цикл сонетов, знаменитого в то время жанра любовной стихотворной лирики. Почти на два столетия были забыты эти поэтические шедевры мастера, но с возникновением романтизма они вновь обрели славу. В XIX веке появилась мода на цитирование бессмертных строк, написанных на исходе ренессанса английским гением.

Тематически стихи представляют собой любовные послания к неизвестному юноше, и лишь последние 26 сонетов из 154 — это обращение к черноволосой даме. Многие исследователи усматривают в этом цикле автобиографические черты, предполагая нетрадиционную ориентацию драматурга. Но некоторые историки склоняются к мысли, что в этих сонетах используется обращение Уильяма Шекспира к своему покровителю и другу графу Саутгемптону в принятой тогда светским обществом форме.

На рубеже веков в творчестве Уильяма Шекспира появляются произведения, которые сделали его имя бессмертным в истории мировой литературы и театра. Практически состоявшийся, успешный творчески и финансово драматург создаёт ряд трагедий, принесших ему славу не только в Англии. Это пьесы «Гамлет», «Макбет», «Король лир», «Отелло». Данные произведения подняли популярность театра «Глобус» до высот одного из самых посещаемых увеселительных заведений Лондона. При этом состояние его владельцев, в том числе и Шекспира, за короткий период неоднократно возросло.

На закате своего творчества Шекспир сочиняет ряд бессмертных произведений, которые удивили современников своей новой формой. В них трагедия сочетается с комедией, а сказочные сюжеты вплетены в канву описания ситуаций из повседневной жизни. Прежде всего это пьесы-фантазии «Буря», «Зимняя сказка», а также драмы на античные сюжеты — «Кориолан», «Антоний и Клеопатра». В этих произведениях Шекспир выступил в качестве большого знатока законов драмы, который легко и изящно собирает воедино черты трагедии и сказки, сложный высоких слог и понятные речевые обороты.

По отдельности многие из драматических произведений Шекспира были изданы ещё при его жизни. Но полное собрание сочинений, в которой вошли практически все канонические пьесы драматурга, появилось лишь в 1623 году. Сборник напечатан был по инициативе друзей Шекспира Уильяма Джона Хеминга и Генри Кондела, которые работали в труппе «Глобуса». Книга, состоящая из 36 пьес английского автора, увидела свет под названием «Первое фолио».

В течение XVII столетия было издано ещё три фолио, которые выходили с некоторыми изменениями и с добавлениями ранее неизданных пьес.

Смерть

Так как последние годы своей жизни Уильям Шекспир страдал серьёзным недугом, свидетельством чему является его измененный почерк, некоторые из последних пьес он создавал в соавторстве с другим драматургом труппы, которого звали Джон Флетчер.

После 1613 года Шекспир окончательно покидает Лондон, но не бросает ведения некоторых дел. Он ещё успевает поучаствовать в судебном процессе своего друга в качестве свидетеля защиты, а также приобретает ещё один особняк в бывшем Блэкфриарском приходе. Некоторое время Уильям Шекспир живёт в поместье своего зятя Джона Холла.

За три года до смерти Уильям Шекспир пишет своё завещание, в котором практически все имущество оставляет за своей старшей дочерью. Скончался английский литератор в конце апреля 1616 года в собственном доме. Его жена Энн пережила своего мужа на 7 лет.

В семье старшей дочери Сьюзен к этому моменту уже была рождена внучка гения Элизабет, но умерла она бездетной. В семье младшей дочери Шекспира Джудит, которая вышла замуж буквально через два месяца после смерти отца за Томаса Куини, было трое мальчиков, но все они умерли в юности. Поэтому прямых потомков у Шекспира не осталось.

Интересные факты

- Точной даты появления на свет Уильяма Шекспира никто не знает. В арсенале историков есть лишь церковная запись о крещении малыша, которое пришлось на 26 апреля 1564 года. Исследователи предполагают, что обряд был совершен на третий день после рождения. Соответственно невероятным образом дата рождения и смерти драматурга пришлись на одно и то же число — 23 апреля.

- Великий английский поэт обладал феноменальной памятью, его познания можно было сравнить с энциклопедическими. Помимо владения двумя древними языками он также знал современные диалекты Франции, Италии и Испании, хотя сам никогда не покидал пределов Английского государства. Шекспир разбирался как в тонких исторических вопросах, так и в текущей политической обстановке. Его познания затрагивали музыку и живопись, он досконально изучил целый пласт ботаники.

- Многие историки склоняются к мысли о нетрадиционной ориентации поэта, ссылаясь на факт отдельного проживания драматурга от семьи, а также на его долгую дружбу с графом Саутгемптоном, который имел привычку одеваться в женскую одежду и наносить большое количество краски на лицо. Но никаких прямых доказательств этому нет.

- Под сомнением остаётся протестантское вероисповедание Шекспира и его семьи. Есть косвенные доказательства о принадлежности его отца к католической конфессии. Но во времена правления Елизаветы I запрещено было быть открытым католиком, поэтому многие приверженцы этого ответвления просто откупались от реформаторов и посещали католическое богослужение тайно.

- Единственный автограф писателя, дошедший до наших дней — это его завещание. В нем он перечисляет все своё имущество до мелочей, но ни разу не упоминает о своих литературных трудах.

- За всю жизнь, предположительно, Шекспир сменил около 10 профессий. Он был сторожем на конюшне театра, актером, соучредителем театра и постановщиком спектаклей. Параллельно с актерской деятельностью Уильям вел ростовщические дела, а в конце жизни занимался пивоварением и сдавал жильё.

- Современные историки поддерживают версию о неизвестном писателе, который сделал Шекспира своим подставным лицом. Даже Британская энциклопедия не отказывается от версии, что создавать пьесы под псевдонимом Шекспир мог граф Эдуард де Вер. Ещё по ряду догадок это могли быть лорд Фрэнсис Бэкон, Королева Елизавета I и даже целая группа лиц аристократического происхождения.

- Поэтический слог Шекспира оказал большое влияние на развитие английского языка, сформировав основу современной грамматики, а также обогатив литературную речь англичан новыми фразами, в качестве которых использовались цитаты из произведений классика. Шекспир оставил в наследие соотечественникам более 1700 новых слов.

Знаменитые цитаты Шекспира

Известные фразы классика часто содержат философские мысли, которые выражены очень точно и лаконично. Большое количество тонких наблюдений посвящено любовной сфере. Вот некоторые из них:

«Грехи других судить Вы так усердно рвётесь – начните со своих и до чужих не доберётесь»;

«Клятвы, данные в бурю, забываются в тихую погоду»;

«Одним взглядом можно убить любовь, одним же взглядом можно воскресить её»;

«Что значит имя? Роза пахнет розой, хоть розой назови ее, хоть нет»;

«Любовь бежит от тех, кто гонится за нею, а тем, кто прочь бежит, кидается на шею».

|

William Shakespeare |

|

|---|---|

The Chandos portrait (held by the National Portrait Gallery, London) |

|

| Born |

Stratford-upon-Avon, England |

| Baptised | 26 April 1564 |

| Died | 23 April 1616 (aged 52)[a]

Stratford-upon-Avon, England |

| Resting place | Church of the Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | c. 1585–1613 |

| Era |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | English Renaissance |

| Spouse |

Anne Hathaway (m. 1582) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

William Shakespeare (bapt. 26 April[b] 1564 – 23 April 1616)[c] was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world’s pre-eminent dramatist.[2][3][4] He is often called England’s national poet and the «Bard of Avon» (or simply «the Bard»).[5][d] His extant works, including collaborations, consist of some 39 plays,[e] 154 sonnets, three long narrative poems, and a few other verses, some of uncertain authorship. His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[7] He remains arguably the most influential writer in the English language, and his works continue to be studied and reinterpreted.

Shakespeare was born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Sometime between 1585 and 1592, he began a successful career in London as an actor, writer, and part-owner of a playing company called the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, later known as the King’s Men. At age 49 (around 1613), he appears to have retired to Stratford, where he died three years later. Few records of Shakespeare’s private life survive; this has stimulated considerable speculation about such matters as his physical appearance, his sexuality, his religious beliefs and whether the works attributed to him were written by others.[8][9][10]

Shakespeare produced most of his known works between 1589 and 1613.[11][12][f] His early plays were primarily comedies and histories and are regarded as some of the best works produced in these genres. He then wrote mainly tragedies until 1608, among them Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth, all considered to be among the finest works in the English language.[2][3][4] In the last phase of his life, he wrote tragicomedies (also known as romances) and collaborated with other playwrights.

Many of Shakespeare’s plays were published in editions of varying quality and accuracy in his lifetime. However, in 1623, John Heminges and Henry Condell, two fellow actors and friends of Shakespeare’s, published a more definitive text known as the First Folio, a posthumous collected edition of Shakespeare’s dramatic works that included all but two of his plays.[13] Its Preface was a prescient poem by Ben Jonson, a former rival of Shakespeare, that hailed Shakespeare with the now famous epithet: «not of an age, but for all time».[13]

Life

Early life

Shakespeare was the son of John Shakespeare, an alderman and a successful glover (glove-maker) originally from Snitterfield in Warwickshire, and Mary Arden, the daughter of an affluent landowning family.[14] He was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, where he was baptised on 26 April 1564. His date of birth is unknown, but is traditionally observed on 23 April, Saint George’s Day.[15] This date, which can be traced to William Oldys and George Steevens, has proved appealing to biographers because Shakespeare died on the same date in 1616.[16][17] He was the third of eight children, and the eldest surviving son.[18]

Although no attendance records for the period survive, most biographers agree that Shakespeare was probably educated at the King’s New School in Stratford,[19][20][21] a free school chartered in 1553,[22] about a quarter-mile (400 m) from his home. Grammar schools varied in quality during the Elizabethan era, but grammar school curricula were largely similar: the basic Latin text was standardised by royal decree,[23][24] and the school would have provided an intensive education in grammar based upon Latin classical authors.[25]

At the age of 18, Shakespeare married 26-year-old Anne Hathaway. The consistory court of the Diocese of Worcester issued a marriage licence on 27 November 1582. The next day, two of Hathaway’s neighbours posted bonds guaranteeing that no lawful claims impeded the marriage.[26] The ceremony may have been arranged in some haste since the Worcester chancellor allowed the marriage banns to be read once instead of the usual three times,[27][28] and six months after the marriage Anne gave birth to a daughter, Susanna, baptised 26 May 1583.[29] Twins, son Hamnet and daughter Judith, followed almost two years later and were baptised 2 February 1585.[30] Hamnet died of unknown causes at the age of 11 and was buried 11 August 1596.[31]

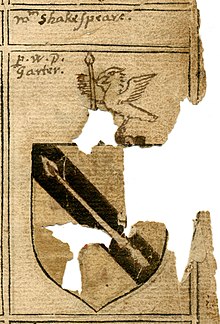

Shakespeare’s coat of arms, from the 1602 book The book of coates and creasts. Promptuarium armorum. It features spears as a pun on the family name.[g]

After the birth of the twins, Shakespeare left few historical traces until he is mentioned as part of the London theatre scene in 1592. The exception is the appearance of his name in the «complaints bill» of a law case before the Queen’s Bench court at Westminster dated Michaelmas Term 1588 and 9 October 1589.[32] Scholars refer to the years between 1585 and 1592 as Shakespeare’s «lost years».[33] Biographers attempting to account for this period have reported many apocryphal stories. Nicholas Rowe, Shakespeare’s first biographer, recounted a Stratford legend that Shakespeare fled the town for London to escape prosecution for deer poaching in the estate of local squire Thomas Lucy. Shakespeare is also supposed to have taken his revenge on Lucy by writing a scurrilous ballad about him.[34][35] Another 18th-century story has Shakespeare starting his theatrical career minding the horses of theatre patrons in London.[36] John Aubrey reported that Shakespeare had been a country schoolmaster.[37] Some 20th-century scholars suggested that Shakespeare may have been employed as a schoolmaster by Alexander Hoghton of Lancashire, a Catholic landowner who named a certain «William Shakeshafte» in his will.[38][39] Little evidence substantiates such stories other than hearsay collected after his death, and Shakeshafte was a common name in the Lancashire area.[40][41]

London and theatrical career

It is not known definitively when Shakespeare began writing, but contemporary allusions and records of performances show that several of his plays were on the London stage by 1592.[42] By then, he was sufficiently known in London to be attacked in print by the playwright Robert Greene in his Groats-Worth of Wit:

… there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger’s heart wrapped in a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country.[43]

Scholars differ on the exact meaning of Greene’s words,[43][44] but most agree that Greene was accusing Shakespeare of reaching above his rank in trying to match such university-educated writers as Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Nashe, and Greene himself (the so-called «University Wits»).[45] The italicised phrase parodying the line «Oh, tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide» from Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 3, along with the pun «Shake-scene», clearly identify Shakespeare as Greene’s target. As used here, Johannes Factotum («Jack of all trades») refers to a second-rate tinkerer with the work of others, rather than the more common «universal genius».[43][46]

Greene’s attack is the earliest surviving mention of Shakespeare’s work in the theatre. Biographers suggest that his career may have begun any time from the mid-1580s to just before Greene’s remarks.[47][48][49] After 1594, Shakespeare’s plays were performed only by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, a company owned by a group of players, including Shakespeare, that soon became the leading playing company in London.[50] After the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603, the company was awarded a royal patent by the new King James I, and changed its name to the King’s Men.[51]

«All the world’s a stage,

and all the men and women merely players:

they have their exits and their entrances;

and one man in his time plays many parts …»

—As You Like It, Act II, Scene 7, 139–142[52]

In 1599, a partnership of members of the company built their own theatre on the south bank of the River Thames, which they named the Globe. In 1608, the partnership also took over the Blackfriars indoor theatre. Extant records of Shakespeare’s property purchases and investments indicate that his association with the company made him a wealthy man,[53] and in 1597, he bought the second-largest house in Stratford, New Place, and in 1605, invested in a share of the parish tithes in Stratford.[54]

Some of Shakespeare’s plays were published in quarto editions, beginning in 1594, and by 1598, his name had become a selling point and began to appear on the title pages.[55][56][57] Shakespeare continued to act in his own and other plays after his success as a playwright. The 1616 edition of Ben Jonson’s Works names him on the cast lists for Every Man in His Humour (1598) and Sejanus His Fall (1603).[58] The absence of his name from the 1605 cast list for Jonson’s Volpone is taken by some scholars as a sign that his acting career was nearing its end.[47] The First Folio of 1623, however, lists Shakespeare as one of «the Principal Actors in all these Plays», some of which were first staged after Volpone, although one cannot know for certain which roles he played.[59] In 1610, John Davies of Hereford wrote that «good Will» played «kingly» roles.[60] In 1709, Rowe passed down a tradition that Shakespeare played the ghost of Hamlet’s father.[35] Later traditions maintain that he also played Adam in As You Like It, and the Chorus in Henry V,[61][62] though scholars doubt the sources of that information.[63]

Throughout his career, Shakespeare divided his time between London and Stratford. In 1596, the year before he bought New Place as his family home in Stratford, Shakespeare was living in the parish of St. Helen’s, Bishopsgate, north of the River Thames.[64][65] He moved across the river to Southwark by 1599, the same year his company constructed the Globe Theatre there.[64][66] By 1604, he had moved north of the river again, to an area north of St Paul’s Cathedral with many fine houses. There, he rented rooms from a French Huguenot named Christopher Mountjoy, a maker of women’s wigs and other headgear.[67][68]

Later years and death

Nicholas Rowe was the first biographer to record the tradition, repeated by Samuel Johnson, that Shakespeare retired to Stratford «some years before his death».[69][70] He was still working as an actor in London in 1608; in an answer to the sharers’ petition in 1635, Cuthbert Burbage stated that after purchasing the lease of the Blackfriars Theatre in 1608 from Henry Evans, the King’s Men «placed men players» there, «which were Heminges, Condell, Shakespeare, etc.».[71] However, it is perhaps relevant that the bubonic plague raged in London throughout 1609.[72][73] The London public playhouses were repeatedly closed during extended outbreaks of the plague (a total of over 60 months closure between May 1603 and February 1610),[74] which meant there was often no acting work. Retirement from all work was uncommon at that time.[75] Shakespeare continued to visit London during the years 1611–1614.[69] In 1612, he was called as a witness in Bellott v Mountjoy, a court case concerning the marriage settlement of Mountjoy’s daughter, Mary.[76][77] In March 1613, he bought a gatehouse in the former Blackfriars priory;[78] and from November 1614, he was in London for several weeks with his son-in-law, John Hall.[79] After 1610, Shakespeare wrote fewer plays, and none are attributed to him after 1613.[80] His last three plays were collaborations, probably with John Fletcher,[81] who succeeded him as the house playwright of the King’s Men. He retired in 1613, before the Globe Theatre burned down during the performance of Henry VIII on 29 June.[80]