Биография

Мужественный человек и обольститель женщин Гай Юлий Цезарь – великий римский полководец, прославившийся военными подвигами, а также характером, из-за которого имя правителя стало нарицательным. Гай Юлий – один из самых известнейших правителей, бывших при власти в Древнем Риме.

Детство и юность

Точная дата рождения Цезаря неизвестна, историками принято считать, что он родился в 100 г. до нашей эры. По крайней мере, такую дату используют историки большинства стран, хотя во Франции принято считать, что Юлий родился в 101 году. Немецкий историк, живший в начале 19-го века, был уверен, что Цезарь родился в 102 до н. э., однако предположения Теодора Моммзена не используются в современной исторической литературе.

Такие разногласия биографов в годах жизни вызваны античными первоисточниками: древнеримские ученые также расходились во мнении по поводу истинной даты рождения Цезаря.

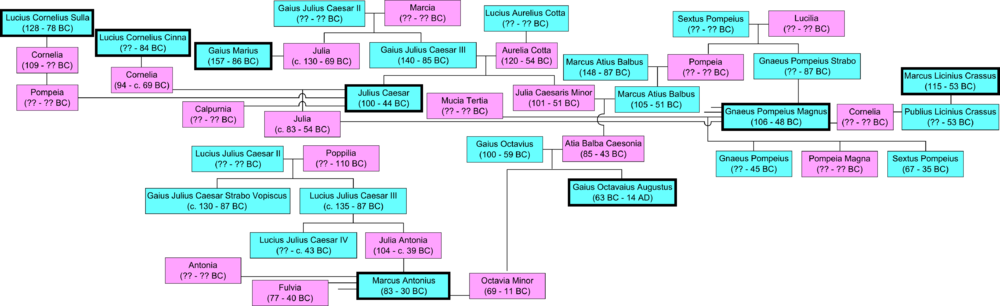

Римский полководец происходил из знатного рода патрициев Юлиев. Легенды повествуют, что эта династия началась с Энея, который, согласно древнегреческой мифологии, прославился в Троянской войне. А родители Энея – выходец из рода дарданских царей Анхис и богиня красоты и любви Афродита (по римской мифологии Венера).

Историю о божественном происхождении Юлия знал римский нобилитет, потому что эта легенда была успешно разнесена родственниками правителя. Сам Цезарь при удобном случае любил вспоминать, что в его роду были боги. Ученые выдвигают гипотезы, что римский правитель происходит из рода Юлиев, которые были правящим сословием в начале основания Римской республики в V–IV веках до н. э.

Ученые также выдвигают различные предположения по поводу прозвища Цезарь. Возможно, один из династии Юлиев родился посредством кесарева сечения. Название процедуры произошло от слова caesarea, что означает «королевский». По другому мнению, кто-то из римского рода родился с длинными и неряшливыми волосами, что обозначалось словом caeserius.

Семья будущего политика жила в достатке. Отец Цезаря Гай Юлий служил на государственной должности, а мать происходила из знатного рода Котт.

Хотя семья полководца была состоятельной, детство Цезарь провел в римском районе Subura. Он был полон женщин легкого поведения, а также там проживали по большему счету бедняки. Античные историки описывают Субуру как грязный и сырой район, лишенный интеллигенции.

Родители Цезаря стремились дать сыну отличное образование: мальчик изучал философию, поэзию, ораторское искусство, а также развивался физически, учился конному спорту. Ученый галл Марк Антоний Гнифон обучал юного Цезаря литературе и этикету. Гай Юлий Цезарь получил римское образование, с детства будущий правитель был патриотом и не подвергался влиянию модной греческой культуры.

Примерно в 85 году до н. э. Юлий потерял отца, поэтому, как единственный мужчина, стал главным кормильцем.

Политика

Когда мальчику было 13 лет, будущего полководца избрали в жрецы главного бога в римской мифологии Юпитера – этот титул один из главных постов иерархии того времени. Однако нельзя назвать сей факт чистыми заслугами юноши, потому что сестра Цезаря, Юлия, была замужем за Марием, древнеримским политическим деятелем.

Но, чтобы стать фламином, по закону Юлий должен был вступить в брак, и военный начальник Корнелий Цинна (он и предложил мальчику роль жреца) выбрал для Цезаря избранницу – собственную дочь Корнелию Циниллу.

В 82 году до н. э. Цезарю пришлось сбежать из Рима. Причиной этому послужила инаугурация Луция Корнелия Суллы Феликса, который начал диктаторскую и кровавую политику. Сулла Феликс велел Цезарю развестись с женой Корнелией, однако тот отказался, чем спровоцировал гнев действующего полководца. Также Гай Юлий был изгнан из Рима, потому что он являлся родственником оппонента Луция Корнелия.

Цезаря лишили титула фламина, а также придания жены и собственного имущества. Переодетому в бедняцкую одежду Юлию пришлось сбежать из республики.

Друзья и родственники просили у Суллы сжалиться над Юлием, и благодаря их ходатайству Цезарь был возвращен на родину. К тому же полководец не видел опасности в лице Юлия и говорил, что Цезарь такой же, как и Марий.

Но жизнь под руководством Суллы Феликса была для римлян невыносимой, поэтому Гай Юлий Цезарь отправился в римскую провинцию, находящуюся в Малой Азии, чтобы обучиться военному ремеслу. Там он стал соратником Марка Минуция Терма, жил в Вифинии и Киликии, а также участвовал в войне против греческого города Метилены. Участвуя во взятии города, Цезарь спас солдата, за что получил вторую по значимости награду – гражданскую корону (дубовый венок).

В 78 году до н. э. несогласные с деятельностью Суллы жители попытались организовать мятеж против кровавого диктатора. Инициатором стал военачальник и консул Марк Эмилий Лепид. Марк приглашал Цезаря поучаствовать в восстании, но Юлий ответил отказом.

После смерти римского диктатора, в 77 году до нашей эры, Цезарь пытался привлечь к судебной ответственности двух приспешников Феликса — Гнея Корнелия Долабеллу и Гая Антония Габриду. Юлий предстал перед судьями с блестящей ораторской речью, однако сулланцам удалось избежать наказания. Обвинения Цезаря были записаны в рукописях и разошлись по Древнему Риму. Однако Юлий посчитал нужным улучшить ораторские навыки и отправился в Родос. На острове жил учитель Цицерона, ритор Аполлоний Молон.

По пути в Родос Цезарь был захвачен местными пиратами, которые потребовали за него выкуп. Находясь в плену, Юлий не боялся разбойников, а, наоборот, шутил с ними и рассказывал поэмы. После освобождения из заложников Юлий снарядил эскадру и отправился пленить пиратов. Суду разбойников предоставить Цезарю не удалось, поэтому он решил казнить обидчиков. Из-за мягкости характера Юлий первоначально велел их убить, а потом уже распять на кресте, чтобы разбойники не мучились.

В 73 году до н. э. Юлий вошел в состав высшей коллегии жрецов, которой раньше управлял брат матери Цезаря Гай Аврелий Котта.

В 68 году до нашей эры Цезарь женится на Помпее, родственнице соратника, а затем злейшего врага Гая Юлия Цезаря Гнея Помпея. Через 2 года он получил должность римского магистрата и занялся благоустройством столицы Италии, организовывал торжества, помогал беднякам. А также, получив звание сенатора, появлялся на политических интригах, чем и завоевывал популярность. Цезарь участвовал в Leges frumentariae («хлебных законах»), по которым население приобретало хлеб по сниженной цене или получало бесплатно, а также в 49–44 годах до н. э. Юлием был проведен ряд реформ

Войны

Галльская война – наиболее известное событие в истории Древнего Рима и биографии Гая Юлия Цезаря.

Цезарь стал проконсулом, к этому времени Италия владела провинцией Нарбонская Галлия (территория нынешней Франции). Юлий отправился на переговоры с вождем кельтского племени в Геневу, так как гельветы начали переселяться из-за нашествия германцев.

Благодаря ораторскому искусству Цезарю удалось уговорить лидера племени не ступать на территорию Римской Республики. Однако гельветы вышли в Среднюю Галлию, где жили эдуи, союзники Рима. Преследовавший кельтское племя Цезарь разбил их войско. В то же время Юлий победил германских свевов, которые напали на галльские земли, находящиеся на территории реки Рейн. После войны он написал сочинение о завоевании Галии «Записки о Галльской войне».

В 55 году до нашей эры римским военачальником были разгромлены пришедшие германские племена, позже и сам Цезарь решил наведаться на территорию германцев.

Цезарь – первый полководец Древнего Рима, который совершил военный поход на территории Рейна: отряд Юлия двигался по специально построенному 400-метровому мосту. Однако в Германии его армия не задержалась, и он предпринял попытку совершить поход на владения Британии. Там военачальник одержал ряд сокрушительных побед, однако положение римской армии было нестабильным, и Цезарю пришлось отступить. К тому же в 54 году до н. э. Юлий вынужден вернуться в Галлию, дабы подавить восстание: галлы превосходили по численности римское войско, но были побеждены.

Во время военных действий Цезарь проявил и стратегические качества, и дипломатическое искусство, он умел манипулировать галльскими вождями и внушать в них противоречия.

Диктатура

После захвата римской власти Юлий стал диктатором и пользовался положением. Цезарь изменил состав сената, а также преобразовал социальный строй: низшие классы перестали гнаться в Рим, потому что диктатором были отменены выплаты дотаций и сокращены раздачи хлеба.

Также Гай Юлий занимался строительством: в Риме было возведено новое здание имени Цезаря, где проходило собрание сената, а на центральной площади столицы Италии был возведен идол покровительницы любви и рода Юлианов, Богини Венеры. Изображения Цезаря и скульптуры украшали храмы и улицы Рима. Каждое слово римского полководца приравнивалось к закону.

Личная жизнь

Помимо Корнелии Циниллы и Помпеи Суллы, у римского политика были еще женщины. Третьей женой Юлия стала Кальпурния Пизонис, которая происходила из знатного плебейского рода и была дальней родственницей матери Цезаря. Замуж за полководца девушка была выдана в 59 году до н. э., причина этого брака объясняется политическими целями, после замужества дочери отец Кальпурнии стал консулом.

Если подробнее говорить о личной жизни Цезаря, то римский диктатор был любвеобилен и имел связи с женщинами на стороне. Также ходили слухи, что Юлий Цезарь был бисексуален и вступал в плотские утехи с мужчинами, например, историки вспоминали юношеские отношения с Никомедом. Возможно, подобные истории имели место быть только потому, что Цезаря пытались оклеветать.

Если говорить о знаменитых любовницах политика, то одной из женщин на стороне военачальника была Сервилия – жена Марка Юния Брута и вторая невеста консула Юния Силана. Цезарь относился снисходительно к любви Сервилии, поэтому пытался выполнять желания ее сына Брута, сделав его одним из первых лиц в Риме.

Но самая знаменитая женщина диктатора – египетская царица Клеопатра. На момент встречи с правительницей, которой исполнился 21 год, Цезарю было за пятьдесят: лавровый венок покрывал лысину, а на лице были морщины. Несмотря на возраст, римский полководец покорил юную красавицу, счастливое существование влюбленных продолжалось 2,5 года и окончилось, когда Цезаря убили.

Известно, что у Юлия Цезаря было двое детей: дочь от первого брака Юлия и сын, родившийся от Клеопатры, Птолемей Цезарион.

Смерть

Умер римский правитель 15 марта 44 года до нашей эры. Причина смерти – заговор сенаторов, которые негодовали из-за четырехлетнего правления диктатора. В заговоре участвовали 14 человек, однако главным считается Марк Юний Брут, сын Сервилии. Цезарь безгранично любил Брута и доверял ему, ставя юношу в высшее положение и ограждая от трудностей. Однако преданный республиканец Марк Юний ради политических целей был готов убить того, кто его безгранично поддерживал.

Некоторые античные историки считали, что Брут приходится сыном Цезаря, так как Сервилия имела любовные отношения с полководцем на момент зачатия будущего заговорщика, но эту теорию нельзя подтвердить достоверными источниками.

По легенде, за день до заговора против Цезаря его жена Кальпурния увидела страшный сон, однако супруг был слишком доверчив, к тому же признавал себя фаталистом – верил в предопределенность событий.

Заговорщики собрались в здании, где проходили собрания сената, возле театра Помпеи. Никто не хотел становиться единоличным убийцей Юлия, поэтому преступниками было решено, что каждый нанесет диктатору по одному единственному удару.

Древнеримский историк Светоний писал, что, когда Юлий Цезарь увидел Брута, он спросил: «И ты, дитя мое?», а в своей книге Уильям Шекспир написал знаменитую цитату: «И ты, Брут?».

Интересные факты

- Месяц июль назван в честь Юлия.

- Современники Цезаря утверждали, что у правителя случались приступы эпилепсии.

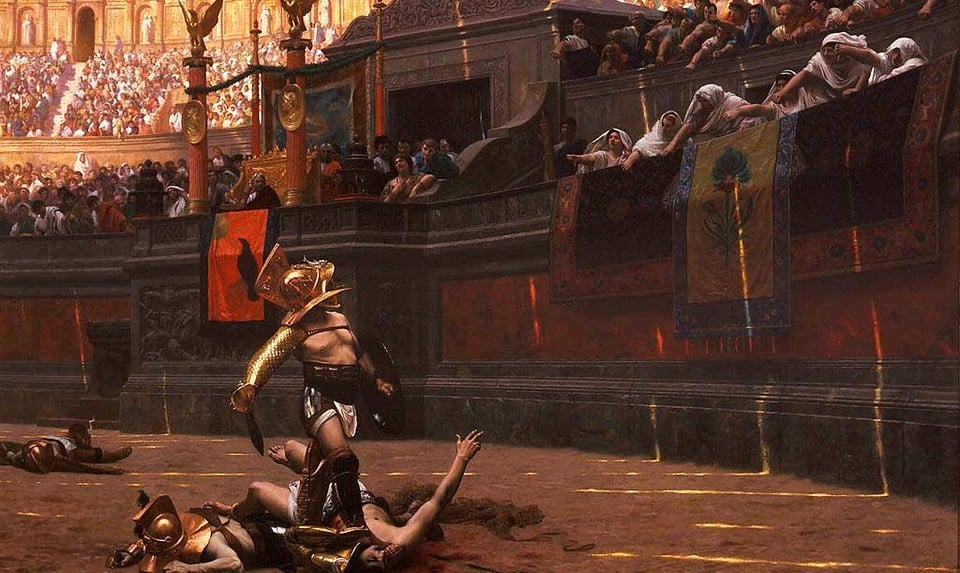

- Во время гладиаторских боев Цезарь постоянно что-то писал на листках бумаги. Однажды правителя спросили, как он умудряется выполнять два дела сразу? На что он ответил: «Цезарь может делать три дела одновременно: и писать, и смотреть, и слушать». Это выражение стало крылатым, иногда Цезарем шутливо называют того человека, который одновременно берется за несколько дел.

- Практически на всех фотографических портретах Гай Юлий Цезарь предстает перед зрителями в лавровом венке. Действительно, в жизни он частенько носил этот триумфальный головной убор, потому что стал рано лысеть.

- Про великого полководца было отснято порядка 10 фильмов, но не все носят биографический характер. Например, в сериале «Рим» правитель вспоминает восстание Спартака, однако некоторые ученые считают, что две легендарные личности связывает только то, что они были современниками.

- Фраза «Пришел, увидел, победил» принадлежит Гаю Юлию Цезарю, он произнес ее после взятия Турции.

- Цезарь использовал шифр для секретной переписки с полководцами. Хотя «шифр Цезаря» примитивен: буква в слове заменялась тем символом, который был левее либо правее в алфавите.

- Знаменитый салат «Цезарь» назван не в честь римского правителя, а в честь повара, придумавшего рецепт.

Цитаты

«Победа зависит от доблести легионов».

«Когда любит один — назови это как хочешь: рабство, привязанность, уважение… Но это не любовь — любовь всегда взаимность!»

«Живи так, чтобы знакомым стало скучно, когда ты умрешь».

«Никакая победа не принесет столько, сколько может отнять одно поражение».

«Война дает право завоевателям диктовать покоренным любые условия».

Римский император Гай Юлий Цезарь (в оригинале «Кáйсар») — один из самых влиятельных лидеров в мировой истории, один из самых выдающихся государственных деятелей всех времён и народов. Этот гениальный полководец, талантливый политик и дипломат был главной фигурой и символом подъёма и расцвета Римской империи.

Молодой Цезарь

Будущий император появился на свет 12 июля 100 г. до н.э. в родовитой семье, которая, по легенде, вела своё начало от богини Венеры.

Мальчик получил классическое образование, как все знатные дети того времени — сначала изучал основные науки в Риме, а потом философию на острове Родос.

В 16 лет юноша отправился на военную службу в Малую Азию и уже там проявил себя отличным воином.

Гай Юлий Цезарь — великий римский император.

Карьера и успехи

После возвращения в Рим 22-летний Гай Юлий включается в борьбу за власть. Он выступает с речами на Форуме — главной площади города — и становится известным оратором.

В возрасте 27 лет Цезарь получает должность военного трибуна (командира в римской армии), в 31 год назначается управляющим Южной Испанией. А в 40 лет становится консулом — государственным чиновником высокого уровня. Он хочет военных подвигов и славы, но Сенат (совет старейшин Рима) не даёт ему разрешения воевать.

Тогда Юлий объединяется с двумя другими политиками Помпеем и Крассом в триумвират («союз троих»). Цезарь без ведома Сената отправляется с походом в Галлию, как раньше называлась Франция, и завоёвывает её, а также часть Британии и Германии. К Риму присоединяется огромная территория в полтора миллиона квадратных километров.

Гражданская война

Помпей напуган успехами бывшего союзника и по приказу Сената идёт против него с войском. Цезарь по закону не имеет права развязывать войну внутри своего государства. Но у него есть верные отряды легионеров и желание стать императором.

У итальянской речки Рубикон он раздумывает, затем начинает битву и побеждает в ней. С тех пор выражение «перейти Рубикон» означает «принять окончательное решение».

Переход через реку Рубикон.

События в Египте

Помпей убегает в Египет, и Цезарь преследует его. Попутно в городе Александрии он вмешивается в борьбу за власть в доме Птолемеев — правящей египетской семьи — и помогает царице Клеопатре получить трон.

Между двумя великими правителями, мужчиной и женщиной, завязывается любовь. Но женой Цезаря Клеопатра так и не стала, более того, позже она была влюблена в другого римского полководца Марка Антония.

Цезарь возводит на трон Клеопатру.

Император

Гай Юлий возвращается в Рим и провозглашает себя императором. Его власть была неограниченной. При этом Цезарь провёл огромное количество реформ:

- устроил и заселил колонии в Европе, Африке и на Востоке;

- увеличил количество чиновников с учётом новых земель;

- отменил многие налоги;

- создал рабочие места за счёт масштабного строительства;

- ввёл законы против роскоши, начал раздачу бесплатного хлеба в городах;

- создал полицию;

- изменил правила на дорогах, например, предложил одностороннее движение на некоторых улицах;

- преобразовал календарь в соответствии с движением Солнца: им мы пользуемся и поныне;

- а также планировал расширить свои территории за счёт завоевания Парфянской империи (нынешние Иран и Ирак).

Видный государственный и политический деятель, талантливый полководец.

Последние годы и смерть

Диктаторское правление Юлия укреплялось. Он даже стал печатать монеты со своим профилем и придумал для себя несколько новых титулов.

Сенаторы были недовольны всем этим и подготовили заговор, чтобы убить Цезаря прямо на заседании Сената. Причём в число заговорщиков вошли его соратники, и даже близкий друг Брут. 56-летнему императору нанесли 23 ножевые раны, от которых он скончался.

Личность. Наследие

По сообщениям из исторических источников, Цезарь был личностью волевой, сильной, с проницательным умом, и при этом весьма нравственной и духовной.

Он отличался особой памятью и наблюдательностью. Всегда имел в голове логичный план действий, но мог гибко изменить его в случае необходимости.

Говорят, что этот человек умел делать несколько разных дел сразу. Существует даже поговорка «как Юлий Цезарь», что означает умение заниматься одновременно многими вещами.

Джереми Систо в роли Юлия Цезаря.

Знаменитые цитаты императора:

- «Жребий брошен» — сказано у речки Рубикон;

- «Пришёл, увидел, победил» — характеристика одной из быстрых побед;

- «И ты, Брут?» — изумление от предательства друга.

В наследие человечеству осталось несколько автобиографических книг, усовершенствованный календарь, а также название месяца «июль», которое было дано в честь Цезаря.

Юлий Цезарь был известным полководцем, политиком и ученым в Древнем Риме , который завоевал обширный регион Галлии и помог начать конец Римской республики, когда он стал диктатором Римской империи. Несмотря на его блестящую военную доблесть, его политические навыки и его популярность среди низшего и среднего класса Рима, его правление было прервано, когда противники, которым угрожала его возрастающая власть, жестоко убили его.

Ранняя жизнь Гая Юлия Цезаря

Гай Юлий Цезарь родился примерно 13 июля 100 г. до н.э. у своего отца, которого также звали Гай Юлий Цезарь, и его матери Аурелии Котта. Он также был племянником известного римского полководца Гая Мариуса.

Цезарь проследил свою родословную до истоков Рима и утверждал, что является потомком богини Венеры через троянского принца Энея и его сына Юла. Однако, несмотря на его якобы благородное происхождение, семья Цезаря не была богатой или особенно влиятельной в римской политике.

После внезапной смерти отца в 85 г. до н. э. Цезарь стал главой семьи в возрасте 16 лет — прямо в разгар гражданской войны между его дядей Марием и римским правителем Луцием Корнелием Суллой. В 84 г. до н.э. он женился на Корнелии, дочери союзника Мариуса. У Цезаря и Корнелии был один ребенок, дочь по имени Юлия.

В 82 г. до н.э. Сулла выиграл гражданскую войну и приказал Цезарю развестись с Корнелией. Цезарь отказался и скрылся. Его семья вмешалась и убедила Суллу пощадить Цезаря; однако Сулла лишил Цезаря наследства.

Несмотря на отсрочку, Цезарь покинул Рим, присоединился к армии и заслужил престижную гражданскую корону за мужество при осаде Митилены в 80 г. до н.э. После смерти Суллы в 78 г. до н.э. Цезарь вернулся в Рим и стал успешным прокурором, широко известным своими ораторскими способностями. .

Политический подъем

Вскоре Цезарь всерьез начал свою политическую карьеру. Он стал военным трибуном, а затем квестором римской провинции в 69 г. до н.э., в том же году, когда умерла его жена Корнелия. В 67 г. до н.э. он женился на Помпее, внучке Суллы и родственнице Гнея Помпея Великого (Помпея Великого), с которой заключил важный союз.

В 65 г. до н.э. Цезарь стал эдилом — важным римским магистратом — и устраивал роскошные игры в Большом цирке, которые понравились публике, но ввергли его в большие долги. Два года спустя он был избран понтификом Максимусом.

Цезарь развелся с Помпеей в 62 г. до н.э. после того, как политик спровоцировал крупный скандал, переодевшись женщиной и пробравшись на священный женский праздник, устроенный Помпеей.

Первый Триумвират

Через год Цезарь стал губернатором Испании. Ряд успешных военных и политических маневров, наряду с поддержкой Помпея и Марка Лициния Красса (известного как самый богатый человек в Риме), помогли Цезарю быть избранным старшим римским консулом в 59 г. до н.э.

Цезарь, Красс и Помпей вскоре сформировали неформальный союз (укрепленный браком дочери Цезаря Юлии с Помпеем), известный как Первый Триумвират. Союз напугал римский сенат, который знал, что партнерство между тремя такими влиятельными людьми не остановить. Они были правы, и триумвират вскоре стал контролировать Рим.

Цезарь в Галлии

Цезарь был назначен губернатором обширной области Галлии (северо-центральная Европа) в 58 г. до н.э., где он командовал большой армией. Во время последующих галльских войн Цезарь провел серию блестящих кампаний по завоеванию и стабилизации региона, заработав репутацию грозного и безжалостного полководца.

Цезарь построил мост через реку Рейн на германские территории и пересек Ла-Манш в Британию. Но его большие успехи в регионе вызвали недовольство Помпея и усложнили и без того натянутые отношения между Помпеем и Крассом.

По мере завоевания Цезарем Галлии политическая ситуация в Риме становилась все более нестабильной, а Помпей оставался единственным консулом. После смерти жены Помпея (и дочери Цезаря) Юлии в 54 г. до н.э. и Красса в 53 г. до н.э. Помпей присоединился к противникам Цезаря и приказал ему бросить свою армию и вернуться в Рим.

Цезарь отказался и смелым и решительным маневром направил свою армию через реку Рубикон в Италию, что спровоцировало гражданскую войну между его сторонниками и сторонниками Помпея. Цезарь и его войска преследовали Помпея в Испании, Греции и, наконец, в Египте.

Юлий Цезарь и Клеопатра

Надеясь предотвратить вторжение Цезаря в Египет, фараон-ребенок Птолемей VIII убил Помпея 28 сентября 48 г. до н.э. Когда Цезарь вошел в Египет, Птолемей подарил ему отрубленную голову Помпея.

Вскоре Цезарь оказался в центре гражданской войны между Птолемеем и его египетским соправителем Клеопатрой . Цезарь стал ее любовником и стал ее партнером, чтобы свергнуть Птолемея и сделать ее правительницей Египта. Пара никогда не была замужем, но их многолетний роман произвел на свет сына, Птолемея XV Цезаря, известного как Цезарион.

Диктатура

Следующие несколько лет Цезарь провел, уничтожая своих врагов и то, что осталось от сторонников Помпея на Ближнем Востоке, в Африке и Испании.

В 46 г. до н.э. он стал диктатором Рима на десять лет, возмутив своих политических противников и подготовив почву для возможного конца Римской республики. Цезарь начал проводить несколько радикальных реформ в интересах низшего и среднего класса Рима, в том числе:

- регулирование распределения субсидированного зерна

- увеличение размера Сената, чтобы представлять больше людей

- сокращение государственного долга

- поддержка ветеранов боевых действий

- предоставление римского гражданства людям на обширных территориях Рима

- реформирование римских налоговых кодексов

Юлий Цезарь Цитаты

Многие до сих пор считают Цезаря великим правителем, хорошо понимающим человеческую природу. На протяжении веков многие его слова стали известными цитатами, например:

Пришел, увидел, победил.

В конце концов, невозможно стать тем, кем тебя считают другие

Какая смерть предпочтительнее любой другой? Неожиданная

Убийство

Цезарь объявил себя пожизненным диктатором в 44 г. до н.э. Однако его крестовый поход за абсолютной властью не понравился многим римским политикам. Опасаясь, что он станет королем, группа сенаторов сговорилась покончить с ним.

В мартовские иды (15 марта 44 г. до н. э.) сенаторы во главе с Гаем Кассием Лонгином, Децимом Юнием Брутом Альбином и Марком Юнием Брутом нанесли Цезарю 23 удара ножом, положив конец как его правлению, так и его жизни, когда он истек кровью упал на Сенат. пол у ног статуи Помпея .

Убийство Цезаря в возрасте 55 лет сделало его мучеником и спровоцировало цикл гражданских войн, приведших к падению Римской республики и приходу к власти его внучатого племянника и наследника Гая Октавия (Октавиана), позже известного как Август Цезарь , императором Рима. Римская империя.

Спасибо за внимание !

Источники :

-Хронология жизни Юлия Цезаря. Государственный университет Сан-Хосе.

-Юлий Цезарь. Энциклопедия древней истории.

-Tom Stevenson. Julius Caesar and the Transformation of the Roman Republic

-Утченко С. Л. Юлий Цезарь

-Грант М. Юлий Цезарь

Юлий Цезарь самый известный правитель Древнего Рима. Описание его деятельности, с трудом умещается в краткую биографию, ведь его жизнь была полна интересных событий.

Детство и юность

Полное имя при рождении Гай Юлий Цезарь, произошел из знатного рода Юлиев. В его родстве были даже Боги Рима. Точной даты его рождения неизвестно, есть только предположительная дата, это 100 год до нашей эры. Его семья жила в достатке, отец был государственным служителем, а мать произошла из древнего знатного рода. Его детство прошло в шикарном родительском доме, который находился в одном из бедных районов Рима. Родители Юлия уделяли особое внимание образованию сына. Он обучался философии, ораторскому искусству, поэзией, а также увлекался конным спортом. Благодаря ему, он находился в хорошей физической форме и имел достаточно крепкое телосложение. Свои первые политические успехи Юлий Цезарь достиг в 13 лет. Тогда его избрали жрецом. После чего он вступил в свой первый брак с дочерью военного начальника, Корнелией. Благодаря этому браку, он приобрел себе новый титул — фламино. А в возрасте 15 лет, Юлий лишился отца. Тогда он, как единственный мужчина стал главой семьи.

Бегство из Рима

82 год до нашей эры стал для Юлия вторым переломным моментом в жизни, после смерти отца. В этот год в Риме правил император Домициан с очень кровавой политикой. Юлий не исполнил требования императора, из-за чего он разозлил его. Вдобавок он являлся родственником его заклятого оппонента. И тогда император лишил Юлия его титула и имущества. Разоренному Юлию, в обычной одежде бедняков, пришлось переехать жить в другое место.

Новая жизнь после бегства

После бегства из центра Рима, он с семьей поселился в его провинции, где стал изучать военное дело. Он даже был участником войны против Греции. А за спасение солдата, Юлий даже был удостоен почетной награды — венок из дуба. В то время в Риме погибает кровавый диктатор, и у Юлия появился шанс вернуться на родину и в свой дом. Он добился суда над помощниками диктатора, где блестяще показал все свои ораторские способности.

Политические успехи

В 73 году до нашей эры Юлий пополнил ряды высшей коллегии жрецов. А в 66 году он получил должность магистра. Его дальнейшая политика была направлена благоустройство столицы, благотворительность и помощь бедному народу. Им было проведено несколько реформ для бедняков, например для них, были снижены цены на хлеб, или вовсе он раздавался бесплатно. Своими благими действиями он завоевал большую популярность и признание жителей Рима.

Участие в войнах

Юлий Цезарь ещё славился как полководец. В его биографии есть несколько воин, победы, поражения и отступления. Самая успешно проведенная им война — это Галльская война (58 г. до н.э. 51 г. до н.э.). Во время этой войны Цезарю удалось предотвратить вступление вражеских кельтских племен в Рим и отвоевать некоторую часть их территории. Войско во главе с Юлием одержали несколько побед и на Британской территории. Он был отличным полководцем, умел правильно использовать все свои навыки, как стратегические, так и дипломатические.

Приход к власти

Стабильность римской власти пошатнулась, чем Цезарь и воспользовался. Он стал новым диктатором Рима. И в городе сразу же произошло много значительных перемен. Изменения претерпел состав Сената и социальный строй общества. А улицы города все больше стали обустраиваться. Во время его правления было построено новое здание для заседания Сената, памятник богине Венере, и много других сооружений. Изображения и скульптуры императора цезаря были на каждой улице Рима, а его слово было как закон.

Личная жизнь

На личном фронте у Юлия было больше побед, чем на боевом фронте. За свою жизнь, а прожил он 56 лет, был женат три раза. Первый и третий брак был скорее для политических выгод, а вот второй возможно и по любви. Помимо официальных супруг, у Юлия было много любовниц. Самая его известная любовница это правительница Египта — Клеопатра. Их отношения начались когда ей было 21 год а ему 53 года, и несмотря на такую внушительную разницу, они были замечательной парой и у них даже родился сын. Также у него была и дочь, от первого брака.

Предательство и смерть

15 марта в 44 году произошел трагический случай, в результате заговора, было совершено убийство. Всё произошло в здании Сената, перед началом заседания. Каждый из заговорщиков, а их было 14, нанес Юлию удар острым предметом. После всех ударов, окровавленный Цезарь скончался на холодном полу здания Сената. В последние дни перед смертью, он подозревал о заговоре против себя, но до последнего верил, что никто не посмеет нанести вред императору, но Его близкий друг Брут оказался организатором заговора. Так предательски и печально закончилась жизнь великого политического деятеля. Его смерть только усугубила положение Великой Империи.

Гай Юлий Цезарь биография

– гг.

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 233.

Гай Юлий Цезарь (100 год до н. э. — 44 год до н. э.) — древнеримский государственный и политический деятель, писатель, полководец. На протяжении многих лет возглавлял великую Римскую республику. Гай Юлий Цезарь, биография которого полна интересных фактов и героических подвигов, вошёл в историю как один из величайших полководцев Древнего Рима. Доклад на тему его жизни и деятельности будет особенно полезен для учеников 5 класса.

Ранние годы

Точная дата рождения будущего полководца неизвестна. Согласно традиционной версии, Гай Юлий Цезарь появился на свет в 100 году до н. э. в патрицианском семействе Юлиев с богатой родословной. Представители этой семьи неизменно играли значительную роль в жизни Рима. Сам Юлий любил повторять, что его род имеет божественное происхождение.

Семья будущего политика была состоятельной: отец занимал высокую государственную должность, мать принадлежала к богатому знатному роду. Родители стремились дать сыну приличное образование, и Юлий с ранних лет прилежно изучал литературу, греческий язык, риторику. Кроме того, он немало времени уделял физическому развитию: хорошо плавал, уверенно держался в седле.

Когда Юлию исполнилось 15 лет, внезапно скончался его отец, и юноша, будучи единственным представителем мужской половины Юлиев, возглавил всё семейство.

Военная и политическая карьера

В 82 году до н. э., когда Римом стал править кровавый диктатор Луций Корнелий Сулла, Цезарь был вынужден покинуть родину. Он нашёл приют в одной из провинций Малой Азии, где стал обучаться военному искусству.

В 77 году до н. э. римский диктатор скончался, и Цезарь увидел перед собой большие перспективы для политической карьеры. Желая усовершенствовать своё ораторское мастерство, он отправился в Родос, чтобы брать уроки у известного ритора. Однако по дороге на Юлия Цезаря напали киликийские пираты, потребовавшие большой выкуп. Получив его, пираты отпустили Юлия на свободу, в ответ же он снарядил эскадру и жестоко покарал их.

В 73 году до н. э. Цезарь победил на выборах в военные трибуны, а также был назначен жрецом-понтификом. В 65 году до н. э. Юлий Цезарь был избран эдилом и смог быстро завоевать популярность в народе, устраивая хлебные раздачи, различные празднества и торжественные события.

Юлий Цезарь прославился и как полководец, на счету которого было несколько крупных войн. Самой успешной стала Галльская война (58–51 гг. до н. э.), во время которой Цезарю удалось не только остановить продвижение кельтских племён в Рим, но и отвоевать внушительную часть вражеской территории.

Приход к власти

В 60 году до н. э. Цезарь создал первый триумвират, вступив в политический союз с Крассом и Помпеем. На должности консула он провёл множество реформ, содержание которых сводилось к укреплению государственной системы и облегчению жизни простых людей.

После смерти Красса в 53 году до н. э. между Цезарем и Помпеем началось вооружённое противостояние за власть в Риме. Сражения длились не один год и закончились победой Юлия Цезаря. Он с триумфом вернулся в Рим, где был избран диктатором на 10-летний срок. Вскоре он был награждён титулом «император», и, несмотря на республиканскую форму правления, приобрёл неограниченную власть в государстве.

Сторонников республики не устраивало такое положение вещей. Против Цезаря был организован заговор, и 15 марта 44 года до н. э. 14 заговорщиков набросились на диктатора и нанесли смертельные ножевые ранения. Среди них был близкий друг императора, Брут.

Личная жизнь

При изучении краткой биографии Юлия Цезаря стоит отметить его весьма насыщенную личную жизнь. Он был трижды женат, имел множество любовниц, среди которых самой известной была египетская царица Клеопатра. Плодом этого союза стал сын Цезаря, Птолемей Цезарион. Также у диктатора была дочь Юлия от первого брака.

Скончался Юлий Цезарь 15 марта 44 года до н.э., став жертвой заговора. Смерть великого полководца ускорила падение Римской Империи.

Тест по биографии

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Water Melon

10/10

-

Egor Spartack

10/10

-

Яна Валишвили

8/10

-

Владимир Николаев

9/10

-

Галина Короткова

10/10

-

Faina Snigir

9/10

Оценка по биографии

4.6

Средняя оценка: 4.6

Всего получено оценок: 233.

А какая ваша оценка за эту биографию?

Гай Юлий Цезарь (Gaius Iulius Caesar) – полководец, политик, литератор, диктатор, верховный жрец Древнего Рима. Он происходил из древнего Римского рода правящего класса и последовательно добивался всех государственных должностей, вел линию политического противостояния сенаторской аристократии. Был милосерден, но отправил на казнь ряд своих главных противников.

Биография

Род Юлиев вел свое происхождение из знатной семьи, которая, по легенде, произошла от богини Венеры.

Мать Юлия Цезаря – Аврелия Котта (Avrelia Kotta) была из знатного и обеспеченного семейства Аврелиев. Бабушка по отцу происходила от древнеримского рода Марциев (Marcii). Анк Марций (Ancus Marcius) был четвертым царем Древнего Рима с 640 по 616 гг. до н. э.

Детство и юность

До нас не дошли точные данные о времени рождения императора. Сегодня принято считать, что он родился в 100 г. до н. э., однако немецкий историк Теодор Моммзен (Theodor Mommsen) считает, что это был 102 г. до н. э., а французский историк Жером Каркопино (Jerome Carcopino) указывает на 101 г. до н. э. Днем рождения считают как 12, так и 13 июля.

Детство Гая Юлия проходило в бедном древнеримском районе Субура (Subura). Родители дали сыну хорошее образование, он учил греческий, поэзию и ораторское искусство, учился плавать, ездил верхом и развивался физически. В 85 г. до н. э. семья потеряла кормильца и Цезарь после инициации стал главой семьи, так как никого из старших родственников мужского пола в живых не осталось.

- Советуем почитать про самых крутых римских императоров

Начало карьеры политика

В Азии

В 80-х годах до н. э. военачальник Луций Корнелий Цинна (Lucius Cornelius Cinna) предложил персону Гая Юлия на место фламина (flamines), жреца бога Юпитера. Но для этого ему необходимо было женится по торжественному древнему обряду конфарреация (confarreatio) и Луций Корнелий выбрал Цезарю в жены свою дочку Корнелию Циниллу (Cornelia Cinilla). В 76 г. до н. э. у супругов родилась дочь Юлия (Ivlia).

Сегодня историки уже не уверены в проведении обряда инаугурации Юлия. С одной стороны, это помешало бы ему заниматься политикой, но, с другой – назначение стало хорошим способом упрочить положение Цезарей.

После обручения Гая Юлия и Корнелии, в войсках случился бунт и военные напали на Цинну, он был убит. Установилась диктатура Луция Корнелии Суллы (Lucius Cornelius Sulla), после чего Цезаря, как родственника оппонента нового правителя объявили вне закона. Он ослушался Суллу, отказался развестись с супругой и уехал из Рима. Диктатор долго разыскивал ослушника, но, по прошествии времени, помиловал его по просьбе родственников.

Скоро Цезарь присоединился к Марку Минуцию Терму (Marcus Minucius Thermus), наместнику римской провинции в Малой Азии – Асии (Asia).

Десять лет назад на этой должности был его отец. Юлий стал всадником (equites) Марка Минуция, сражавшимся верхом патрицианцем. Первое задание, которое дал Терм своему контуберналу – провести переговоры с вифинским (Bithynia) царем Никомедом IV (Nycomed IV). В результате успешных переговоров правитель передает Терму флотилию для взятия города Митилены (Mytlene) на острове Лесбос (Lesvos), который не принял результатов Первой Митридатовой войны (89-85 гг. до н. э.) и оказывал сопротивление римскому народу. Город был успешно захвачен.

За операцию на Лесбосе Гай Юлий получил гражданскую корону – воинскую награду, а Марк Минуций сложил полномочия. В 78 г. до н. э. в Италии умирает Луций Сулла и Цезарь принимает решение вернуться на родину.

Римские события

В 78 г. до н. э. военачальник Марк Лепид (Marcus Lepidus) организовал бунт италийцев (Italici) против законов Луция. Цезарь тогда не принял приглашение стать его участником. В 77-76 гг. до н. э Гай Юлий пытался засудить сторонников Суллы: политика Корнелия Долабеллу (Cornelius Dolabella) и полководца Антония Гибриду (Antonius Hybrida). Но это ему не удалось, не смотря на блистательные обвинительные речи.

После этого Юлий решил посетить остров Родос (Rhodus) и школу риторики Аполлония Молона (Apollonius Molon), но по пути туда попал в плен к пиратам, откуда впоследствии был вызволен азиатскими послами за пятьдесят талантов. Желая отомстить, бывший пленник снарядил несколько кораблей и сам взял пиратов в плен, казнив их распятием. В 73 г до н. э. Цезаря включили в состав коллегиального органа управления понтификов, где ранее правил его дядя Гай Аврелий Котта (Gaius Aurelius Cotta).

В 69 г. до н. э. скончалась при родах второго ребенка супруга Цезаря – Корнелия, младенец тоже не выжил. В это же время погибает и тетя Цезаря – Юлия Мария (Ivlia Maria). Вскоре Гай Юлий становится римским ординарным магистратом (magistratus), что дает ему возможность войти в сенат. Он был отправлен в Дальнюю Испанию (Hispania Ulterior), где взял на себя решение финансовых вопросов и выполнение поручений пропретора Антистия Вета (Antistius Vetus).

В 67 г. до н. э. Цезарь сочетался браком с Помпеей Сулла (Pompeia Sulla), внучкой Суллы. В 66 г. до н. э. Гай Юлий становится смотрителем самой значимой общественной дороги Рима – Аппиевой дороги (Via Appia) и финансирует ее ремонт.

Коллегия магистратов и выборы

В 66 г. до н. э. Гая Юлия выбирают в магистраты Рима. В круг его обязанностей входит расширение строительства в городе, поддержание торговли и общественных мероприятий. В 65 г. до н. э. он провел такие запоминающиеся Римские игры с участием гладиаторов, что сумел изумить своих искушенных горожан.

В 64 г. до н. э. Гай Юлий был главой судебной комиссии (Quaestiones perpetuae) по уголовным процессам, что позволило ему призвать к ответу и наказать многих приспешников Суллы.

В 63 г. до н. э. умер Квинт Метелл Пий (Quintus Metellus Pius), освобождая пожизненное место Великого понтифика (Pontifex Maximus). Цезарь принимает решение выдвинуть на нее собственную кандидатуру. Оппонентами Гая Юлия становятся консул Квинт Катул Капитолин (Quintus Catulus Capitolinus) и полководец Публий Ватия Исаврик (Publius Vatia Isauricus). После многочисленных подкупов Цезарь выигрывает выборы с большим перевесом и переезжает жить на Священную дорогу (via Sacra) в казенное жилье понтифика.

Участие в заговоре

В 65 и 63 гг. до н. э. один из политических заговорщиков Луций Сергий Катилина (Lucius Sergius Catilina) дважды делал попытки совершить государственный переворот. Марк Туллий Цицерон (Marcus Tullius Cicero), будучи оппонентом Цезаря, попытался обвинить того в участии в заговорах, но не смог предоставить необходимых доказательств и потерпел неудачу. Марк Порций Катон (Marcus Porcius Cato), неформальный лидер римского сената, также свидетельствовал против Цезаря и добился того, что из сената Гай Юлий выходил преследуемый угрозами.

Первый триумвират

Претура

В 62 г. до н. э., пользуясь полномочиями претора, Цезарь хотел передать реконструкцию плана Юпитера Капитолийского (Iuppiter Optimus Maximus Capitolinus) от Квинта Катула Капитолина (Quintus Catulus Capitolinus) Гнею Помпею Магну (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus), но сенат не поддержал этот законопроект.

После поддержанного Цезарем предложения трибуна Квинта Цецилия Метелла Непота (Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos) отправить Помпея с войсками в Рим для усмирения Катилины, сенат отстранил и Квинта Цицелия и Гая Юлия от должностей, но второй быстро был восстановлен.

Осенью над заговорщиками Катилины прошел суд. Один из его участников – Луций Юлий Веттий (Lucius Iulius Vettius), выступишвий против Цезаря, был арестован, как и судья Новер Нигер (Novius Nigerus), принявший донесение.

В 62 г. до н. э. супруга Цезаря Помпея устроила в их доме празднество, посвященное Доброй Богине (Bona Dea), на котором могли присутствовать только женщины. Но на праздник попал один из политиков – Публий Клодий Пульхр (Publius Clodius Pulcher), он переоделся в женщину и хотел встретиться с Помпеей. Сенаторы узнали о произошедшем, сочли это позором и потребовали суда. Гай Юлий не стал ждать итогов процесса и развелся с Помпеей, чтобы не выносить на всеобщее обозрение свою личную жизнь. Тем более, у супругов так и не родились наследники.

В Дальней Испании

В 61 г. до н. э. поездка Гая Юлия в Дальнюю Испанию в качестве пропретора (propraetor) откладывалась долгое время в связи с наличием большого количества долгов. Полководец Марк Лициний Красс (Marcus Licinius Crassus) поручился за Гая Юлия и оплатил часть его кредитов.

Когда новый пропретор прибыл к месту назначения, ему пришлось столкнуться с недовольством жителями римской властью. Цезарь собрал отряд ополченцев и начал борьбу с “бандитами”. Полководец с двенадцатитысячной армией подошел к горному хребту Серра-да-Эштрела (Serra da Estrela) и приказал местным жителям уйти оттуда. Они отказались переселяться и Гай Юлий атаковал их. Горцы через Атлантический океан ушли на острова Берленга (Berlenga), перебив всех своих преследователей.

Но Цезарь, после ряда продуманных операций и стратегических маневров все-таки покоряет народное сопротивление, после чего ему был присвоен почетный воинский титул императора (imperator), победителя.

Гай Юлий развернул активную деятельность и в повседневных делах подчиненных земель. Он председательствовал в судебных заседаниях, ввел реформы в налогообложение, искоренил практику жертвоприношений.

За период деятельности в Испании Цезарь смог расплатиться с большинством своих долгов благодаря богатым подаркам и взяткам жителей обеспеченного юга. В начале 60 г. до н. э. Гай Юлий досрочно снимает с себя возложенные полномочия и возвращается в Рим.

Триумвират

Слухи о победах пропретора вскоре дошли до сената и его члены посчитали, что возвращение Цезаря должно сопровождаться триумфом (triumphus) – торжественным вступлением в столицу. Но тогда, до свершения триумфального события Гаю Юлию не разрешалось, по закону, входить в город. А так как он планировал еще и принять участие в предстоящих выборах на пост консула, где для регистрации требовалось его личное присутствие, то полководец отказывается от триумфа и начинает борьбу за новую должность.

Путем подкупа избирателей Цезарь все-таки становится консулом, вместе с ним выборы выигрывает и военачальник Марк Кальпурний Бибул (Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus).

В целях укрепления собственного политического положения и имеющейся власти, Цезарь вступает в тайный сговор с Помпеем и Крассом, объединяя двух влиятельных политиков с противоположными взглядами. В результате сговора появляется мощный союз военачальников и политиков, получивший название Первый триумвират (triumviratus — «союз трёх мужей»).

Консульство

В первые дни консульства Цезарь начал выносить на рассмотрение сената новые законопроекты. Первым был принят аграрный закон, согласно которому бедняки могли получить участки земли от государства, которые оно выкупало у крупных землевладельцев. В первую очередь землю давали многодетным семьям. Чтобы не допустить спекуляции, новые землевладельцы не имели права перепродавать наделы в течение следующих двадцати лет. Второй законопроект касался обложения налогами откупщиков провинции Азия, их взносы были снижены на одну треть. Третий закон касался взяток и вымогательства, он был принят единогласно, в отличие от первых двух.

Чтобы укрепить связь с Помпеем, Гай Юлий выдал за него свою дочь Юлию. Сам Цезарь в третий раз решается на брак, на этот раз его женой становится Кальпурния (Calpurnia), дочь Луция Кальпурнии Пизона Цезонина (Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus).

Проконсул

Галльская война

Когда Гай Юлий, по истечении положенного срока, сложил с себя полномочия консула, он продолжил завоевывать земли для Рима. Во время Галльской войны (Bellum Gallicum) Цезарь, проявив необычайную дипломатию и стратегию, искусно воспользовался разногласиями галльских вождей. В 55 г. до н. э. он разбил германцев, переправившихся через Рейн (Rhein), после чего за десять дней построил мост длиной 400 метров и сам напал на них, первый в истории Рима. Первым из римских полководцев вторгся в Великобританию (Great Britain), где провел несколько блестящих военных операций, после чего вынужден был оставить остров.

В 56 г. до н. э. в Лукке (Lucca) состоялось очередное заседание триумвиров, на котором было принято решение продолжать и развивать политическую поддержку друг друга.

К 50 г. до н. э. Гай Юлий подавил все восстания, полностью подчинив Риму его бывшие территории.

Гражданская война

В 53 г. до н. э. Красс умирает и триумвират прекращает свое существование. Между Помпеем и Юлием началась борьба. Помпей стал главой республиканского правления, а сенат не продлил полномочия Гая Юлия в Галлии. Тогда Цезарь принимает решение поднять восстание. Собрав солдат, у которых пользовался огромной популярностью, он переходит через реку приграничную Рубикон (Rubicone) и, не видя сопротивления, захватывает некоторые города. Перепуганный Помпей и его приближенные сенаторы бегут из столицы. Цезарь предлагает остальным членам сената совместно править страной.

В Риме Цезаря назначают диктатором. Попытки Помпея помешать Гаю Юлию потерпели крах, самого беглеца убили в Египте, но Цезарь не принял в дар голову врага, он оплакивал его смерть. Будучи в Египте Цезарь помогает царице Клеопатре (Cleopatra), покоряет Александрию (AIskandariya), в Северной Африке присоединяет к Риму Нумидию (Numidia).

Убийство

Возвращение Гая Юлия в столицу сопровождается пышным триумфом. Он не скупится на награждения своим солдатам и полководцам, устраивает пиры для граждан города, организует игры и массовые зрелища. В течение следующих десяти лет его провозглашают “императором” и “отцом отечества”. Он издает множество законов, среди которых законы о гражданстве, об устройстве государства, против роскоши, о безработице, о выдаче бесплатного хлеба, меняет систему исчисления времени и другие.

Цезаря боготворили и оказывали ему огромные почести, возводя его статуи и рисуя портреты. У него была лучшая охрана, он лично занимался назначением персон на государственные должности и их смещением.

Среди республиканцев росло недовольство политикой и поведением Цезаря. Ему вменяли отношения с царицей Клеопатрой, которая переехала в столицу. Тогда Марк Юний Брут (Marcus Junius Brutus) и Гай Кассий Лонгин (Gaius Cassius Longinus) вступили в заговор чтобы убить диктатора.

15 марта 44 г. до н. э. на заседании сената Брут вонзил кинжал в Цезаря и тот скончался. Единственным наследником Юлия Цезаря стал усыновленный им внучатый племянник Октавиан Август (Octavianus Augustus). Читайте цикл статей про убийство Цезаря и восхождение Октавина.

|

Gaius Julius Caesar |

|

|---|---|

The Tusculum portrait, possibly the only surviving sculpture of Caesar made during his lifetime. Archaeological Museum, Turin, Italy. |

|

| Born | 12 July 100 BC[1]

Rome, Italy |

| Died | 15 March 44 BC (aged 55)

Theatre of Pompey, Rome |

| Cause of death | Assassination (stab wounds) |

| Resting place | Temple of Caesar, Rome 41°53′31″N 12°29′10″E / 41.891943°N 12.486246°E |

| Occupations |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Office |

|

| Spouses |

|

| Partner | Cleopatra |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Awards | Civic Crown |

| Military service | |

| Years of service | 81–45 BC |

| Battles/wars |

|

Gaius Julius Caesar (; Latin: [ˈɡaːiʊs ˈjuːliʊs ˈkae̯sar]; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and subsequently became dictator from 49 BC until his assassination in 44 BC. He played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

In 60 BC, Caesar, Crassus and Pompey formed the First Triumvirate, an informal political alliance that dominated Roman politics for several years. Their attempts to amass power as Populares were opposed by the Optimates within the Roman Senate, among them Cato the Younger with the frequent support of Cicero. Caesar rose to become one of the most powerful politicians in the Roman Republic through a string of military victories in the Gallic Wars, completed by 51 BC, which greatly extended Roman territory. During this time he both invaded Britain and built a bridge across the Rhine river. These achievements and the support of his veteran army threatened to eclipse the standing of Pompey, who had realigned himself with the Senate after the death of Crassus in 53 BC. With the Gallic Wars concluded, the Senate ordered Caesar to step down from his military command and return to Rome. In 49 BC, Caesar openly defied the Senate’s authority by crossing the Rubicon and marching towards Rome at the head of an army.[3] This began Caesar’s civil war, which he won, leaving him in a position of near unchallenged power and influence in 45 BC.

After assuming control of government, Caesar began a program of social and governmental reforms, including the creation of the Julian calendar. He gave citizenship to many residents of far regions of the Roman Republic. He initiated land reform and support for veterans. He centralized the bureaucracy of the Republic and was eventually proclaimed «dictator for life» (dictator perpetuo). His populist and authoritarian reforms angered the elites, who began to conspire against him. On the Ides of March (15 March) 44 BC, Caesar was assassinated by a group of rebellious senators led by Brutus and Cassius, who stabbed him to death.[4][5] A new series of civil wars broke out and the constitutional government of the Republic was never fully restored. Caesar’s great-nephew and adopted heir Octavian, later known as Augustus, rose to sole power after defeating his opponents in the last civil war of the Roman Republic. Octavian set about solidifying his power, and the era of the Roman Empire began.

Caesar was an accomplished author and historian as well as a statesman; much of his life is known from his own accounts of his military campaigns. Other contemporary sources include the letters and speeches of Cicero and the historical writings of Sallust. Later biographies of Caesar by Suetonius and Plutarch are also important sources. Caesar is considered by many historians to be one of the greatest military commanders in history.[6] His cognomen was subsequently adopted as a synonym for «Emperor»; the title «Caesar» was used throughout the Roman Empire, giving rise to modern descendants such as Kaiser and Tsar. He has frequently appeared in literary and artistic works, and his political philosophy, known as Caesarism, has inspired politicians into the modern era.

Early life and career

Gaius Julius Caesar was born into a patrician family, the gens Julia, which claimed descent from Julus, son of the legendary Trojan prince Aeneas, supposedly the son of the goddess Venus.[7] The Julii were of Alban origin, mentioned as one of the leading Alban houses, which settled in Rome around the mid-7th century BC, following the destruction of Alba Longa. They were granted patrician status, along with other noble Alban families.[8] The Julii also existed at an early period at Bovillae, evidenced by a very ancient inscription on an altar in the theatre of that town, which speaks of their offering sacrifices according to the lege Albana, or Alban rites.[9][10][11] The cognomen «Caesar» originated, according to Pliny the Elder, with an ancestor who was born by Caesarean section (from the Latin verb «to cut», caedere, caes-).[12] The Historia Augusta suggests three alternative explanations: that the first Caesar had a thick head of hair («caesaries»); that he had bright grey eyes («oculis caesiis»); or that he killed an elephant («caesai» in Moorish) in battle.[13]

Despite their ancient pedigree, the Julii Caesares were not especially politically influential, although they had enjoyed some revival of their political fortunes in the early 1st century BC.[14] Caesar’s father, also called Gaius Julius Caesar, governed the province of Asia,[15] and his sister Julia, Caesar’s aunt, married Gaius Marius, one of the most prominent figures in the Republic.[16] His mother, Aurelia, came from an influential family. Little is recorded of Caesar’s childhood.[17]

In 85 BC, Caesar’s father died suddenly,[18] making Caesar the head of the family at the age of 16. His coming of age coincided with the civil wars of his uncle Gaius Marius and his rival Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Both sides carried out bloody purges of their political opponents whenever they were in the ascendancy. Marius and his ally Lucius Cornelius Cinna were in control of the city when Caesar was nominated as the new flamen Dialis (high priest of Jupiter),[19] and he was married to Cinna’s daughter Cornelia.[20][21]

Following Sulla’s final victory, however, Caesar’s connections to the old regime made him a target for the new one. He was stripped of his inheritance, his wife’s dowry, and his priesthood, but he refused to divorce Cornelia and was instead forced to go into hiding.[22] The threat against him was lifted by the intervention of his mother’s family, which included supporters of Sulla, and the Vestal Virgins. Sulla gave in reluctantly and is said to have declared that he saw many a Marius in Caesar.[17] The loss of his priesthood had allowed him to pursue a military career, as the high priest of Jupiter was not permitted to touch a horse, sleep three nights outside his own bed or one night outside Rome, or look upon an army.[23]

Caesar felt that it would be much safer far away from Sulla should the dictator change his mind, so he left Rome and joined the army, serving under Marcus Minucius Thermus in Asia and Servilius Isauricus in Cilicia. He served with distinction, winning the Civic Crown for his part in the Siege of Mytilene. He went on a mission to Bithynia to secure the assistance of King Nicomedes’s fleet, but he spent so long at Nicomedes’ court that rumours arose of an affair with the king, which Caesar vehemently denied for the rest of his life.[24]

Hearing of Sulla’s death in 78 BC, Caesar felt safe enough to return to Rome. He lacked means since his inheritance was confiscated, but he acquired a modest house in Subura, a lower-class neighbourhood of Rome.[25] He turned to legal advocacy and became known for his exceptional oratory accompanied by impassioned gestures and a high-pitched voice,[26] and ruthless prosecution of former governors notorious for extortion and corruption.[citation needed]

On the way across the Aegean Sea,[27] Caesar was captured by pirates and held prisoner.[28][29] He maintained an attitude of superiority throughout his captivity. The pirates demanded a ransom of 20 talents of silver, but he insisted that they ask for 50.[30][31] Caesar was relaxed and familiar with his captors, and (seemingly) joked that after his release he would raise a fleet, pursue and capture the pirates, and crucify them while alive.[32] After his ransom was paid he fulfilled this promise in full, apart from one detail – as a sign of leniency, he first had their throats cut. He was soon called back into military action in Asia, raising a band of auxiliaries to repel an incursion from the east.[33]

On his return to Rome, he was elected military tribune, a first step in a political career. He was elected quaestor in 69 BC,[34] and during that year he delivered the funeral oration for his aunt Julia, including images of her husband Marius, unseen since the days of Sulla, in the funeral procession. His wife Cornelia also died that year.[35] Caesar went to serve his quaestorship in Hispania after his wife’s funeral, in the spring or early summer of 69 BC.[36] While there, he is said to have encountered a statue of Alexander the Great, and realised with dissatisfaction that he was now at an age when Alexander had the world at his feet, while he had achieved comparatively little. On his return in 67 BC,[37] he married Pompeia, a granddaughter of Sulla, whom he later divorced in 61 BC after her embroilment in the Bona Dea scandal.[38] In 65 BC, he was elected curule aedile, and staged lavish games that won him further attention and popular support.[39]

In 63 BC, he ran for election to the post of pontifex maximus, chief priest of the Roman state religion. He ran against two powerful senators. Accusations of bribery were made by all sides. Caesar won comfortably, despite his opponents’ greater experience and standing.[40] Cicero was consul that year, and he exposed Catiline’s conspiracy to seize control of the Republic; several senators accused Caesar of involvement in the plot.[41]

After serving as praetor in 62 BC, Caesar was appointed to govern Hispania Ulterior (the western part of the Iberian Peninsula) as propraetor,[42][43][44] though some sources suggest that he held proconsular powers.[45][46] He was still in considerable debt and needed to satisfy his creditors before he could leave. He turned to Marcus Licinius Crassus, the richest man in Rome. Crassus paid some of Caesar’s debts and acted as guarantor for others, in return for political support in his opposition to the interests of Pompey. Even so, to avoid becoming a private citizen and thus open to prosecution for his debts, Caesar left for his province before his praetorship had ended. In Hispania, he conquered two local tribes and was hailed as imperator by his troops; he reformed the law regarding debts, and completed his governorship in high esteem.[47]

Caesar was acclaimed imperator in 60 BC (and again later in 45 BC). In the Roman Republic, this was an honorary title assumed by certain military commanders. After an especially great victory, army troops in the field would proclaim their commander imperator, an acclamation necessary for a general to apply to the Senate for a triumph. However, Caesar also wished to stand for consul, the most senior magistracy in the Republic. If he were to celebrate a triumph, he would have to remain a soldier and stay outside the city until the ceremony, but to stand for election he would need to lay down his command and enter Rome as a private citizen. He could not do both in the time available. He asked the Senate for permission to stand in absentia, but Cato blocked the proposal. Faced with the choice between a triumph and the consulship, Caesar chose the consulship.[48]

First Consulship, First Triumvirate, Military Campaigns

A denarius depicting Julius Caesar, dated to February–March 44 BC—the goddess Venus is shown on the reverse, holding Victoria and a scepter. Caption: CAESAR IMP. M. / L. AEMILIVS BVCA

In 60 BC, Caesar sought election as consul for 59 BC, along with two other candidates. The election was sordid—even Cato, with his reputation for incorruptibility, is said to have resorted to bribery in favour of one of Caesar’s opponents. Caesar won, along with conservative Marcus Bibulus.[49]

First Triumvirate

Caesar was already in Marcus Licinius Crassus’ political debt, but he also made overtures to Pompey. Pompey and Crassus had been at odds for a decade, so Caesar tried to reconcile them. The three of them had enough money and political influence to control public business. This informal alliance, known as the First Triumvirate («rule of three men»), was cemented by the marriage of Pompey to Caesar’s daughter Julia.[50] Caesar also married again, this time Calpurnia, who was the daughter of another powerful senator.[51]

Caesar proposed a law for redistributing public lands to the poor—by force of arms, if need be—a proposal supported by Pompey and by Crassus, making the triumvirate public. Pompey filled the city with soldiers, a move which intimidated the triumvirate’s opponents. Bibulus attempted to declare the omens unfavourable and thus void the new law, but he was driven from the forum by Caesar’s armed supporters. Bibulus’ lictors had their fasces broken, two high magistrates accompanying him were wounded, and he had a bucket of excrement thrown over him. In fear of his life, he retired to his house for the rest of the year, issuing occasional proclamations of bad omens. These attempts proved ineffective in obstructing Caesar’s legislation. Roman satirists ever after referred to the year as «the consulship of Julius and Caesar».[52]

When Caesar was first elected, the aristocracy tried to limit his future power by allotting the woods and pastures of Italy, rather than the governorship of a province, as his military command duty after his year in office was over.[53] With the help of political allies, Caesar secured passage of the lex Vatinia, granting him governorship over Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy) and Illyricum (northwest Balkans).[54] At the instigation of Pompey and his father-in-law Piso, Transalpine Gaul (southern France) was added later after the untimely death of its governor, giving him command of four legions.[54] The term of his governorship, and thus his immunity from prosecution, was set at five years, rather than the usual one.[55][56] When his consulship ended, Caesar narrowly avoided prosecution for the irregularities of his year in office, and quickly left for his province.[57]

Conquest of Gaul

The extent of the Roman Republic in 40 BC after Caesar’s conquests

Caesar was still deeply in debt, but there was money to be made as a governor, whether by extortion[58] or by military adventurism. Caesar had four legions under his command, two of his provinces bordered on unconquered territory, and parts of Gaul were known to be unstable. Some of Rome’s Gallic allies had been defeated by their rivals at the Battle of Magetobriga, with the help of a contingent of Germanic tribes. The Romans feared these tribes were preparing to migrate south, closer to Italy, and that they had warlike intent. Caesar raised two new legions and defeated these tribes.[59]

In response to Caesar’s earlier activities, the tribes in the north-east began to arm themselves. Caesar treated this as an aggressive move and, after an inconclusive engagement against the united tribes, he conquered the tribes piecemeal. Meanwhile, one of his legions began the conquest of the tribes in the far north, directly opposite Britain.[60] During the spring of 56 BC, the Triumvirs held a conference, as Rome was in turmoil and Caesar’s political alliance was coming undone. The Luca Conference renewed the First Triumvirate and extended Caesar’s governorship for another five years.[61] The conquest of the north was soon completed, while a few pockets of resistance remained.[62] Caesar now had a secure base from which to launch an invasion of Britain.

In 55 BC, Caesar repelled an incursion into Gaul by two Germanic tribes, and followed it up by building a bridge across the Rhine and making a show of force in Germanic territory, before returning and dismantling the bridge. Late that summer, having subdued two other tribes, he crossed into Britain, claiming that the Britons had aided one of his enemies the previous year, possibly the Veneti of Brittany.[63] His knowledge of Britain was poor, and although he gained a beachhead on the coast, he could not advance further. He raided out from his beachhead and destroyed some villages, then returned to Gaul for the winter.[64] He returned the following year, better prepared and with a larger force, and achieved more. He advanced inland, and established a few alliances, but poor harvests led to widespread revolt in Gaul, forcing Caesar to leave Britain for the last time.[65]

Though the Gallic tribes were just as strong as the Romans militarily, the internal division among the Gauls guaranteed an easy victory for Caesar. Vercingetorix’s attempt in 52 BC to unite them against Roman invasion came too late.[66][67] He proved an astute commander, defeating Caesar at the Battle of Gergovia, but Caesar’s elaborate siege-works at the Battle of Alesia finally forced his surrender.[68] Despite scattered outbreaks of warfare the following year,[69] Gaul was effectively conquered. Plutarch claimed that during the Gallic Wars the army had fought against three million men (of whom one million died, and another million were enslaved), subjugated 300 tribes, and destroyed 800 cities.[70] The casualty figures are disputed by modern historians.[71]

Civil war

While Caesar was in Britain his daughter Julia, Pompey’s wife, had died in childbirth. Caesar tried to re-secure Pompey’s support by offering him his great-niece in marriage, but Pompey declined. In 53 BC, Crassus was killed leading a failed invasion of Parthia. Due to uncontrolled political violence in the city, Pompey was appointed sole consul in 52 as an emergency measure.[72] That year, a «Law of the Ten Tribunes» was passed, giving Caesar the right to stand for a consulship in absentia.[73]

From the period 52 to 49 BC, trust between Caesar and Pompey disintegrated.[74] In 51 BC, the consul Marcellus proposed recalling Caesar, arguing that his provincia (here meaning «task») – due to his victory – in Gaul was complete; the proposal was vetoed.[75][76] That year, it seemed that the conservatives around Cato in the Senate would seek to enlist Pompey to force Caesar to return from Gaul without honours or a second consulship.[77] Pompey, however, at the time intended to go to Spain;[77] Cato, Bibulus, and their allies, however, were successful in winning Pompey over to take a hard line against Caesar’s continued command.[78]

As 50 BC progressed, fears of civil war grew; both Caesar and his opponents started building up troops in southern Gaul and northern Italy, respectively.[79] In the autumn, Cicero and others sought disarmament by both Caesar and Pompey, and on 1 December 50 BC this was formally proposed in the Senate.[80] It received overwhelming support – 370 to 22 – but was not passed when one of the consuls dissolved the Senate meeting.[81] At the start of 49 BC, Caesar’s renewed offer that he and Pompey disarm was read to the Senate, which was rejected by the hardliners.[82] A later compromise given privately to Pompey was also rejected at their insistence.[83] On 7 January, his supportive tribunes were driven from Rome; the Senate then declared Caesar an enemy and it issued its senatus consultum ultimum.[84]

There is scholarly disagreement as to the specific reasons why Caesar marched on Rome. A popular theory is that Caesar was in a position where he was forced to choose between prosecution and exile or civil war.[85] Whether Caesar actually would have been prosecuted and convicted is debated. Some scholars believe the possibility of successful prosecution was extremely unlikely.[86][87] Caesar’s main objectives were to secure a second consulship and a triumph. He feared that his opponents – then holding both consulships for 50 BC – would reject his candidacy or refuse to ratify an election he won.[88] This also was the core of his war justification: that Pompey and his allies were planning, by force if necessary (indicated in the expulsion of the tribunes[89]), to suppress the liberty of the Roman people to elect Caesar and honour his accomplishments.[90]

Around 10 or 11 January 49 BC,[91][92] in response to the Senate’s «final decree»,[93] Caesar crossed the Rubicon – the river defining the northern boundary of Italy – with a single legion, the Legio XIII Gemina, and ignited civil war. Upon crossing the Rubicon, Caesar, according to Plutarch and Suetonius, is supposed to have quoted the Athenian playwright Menander, in Greek, «the die is cast».[94] Erasmus, however, notes that the more accurate Latin translation of the Greek imperative mood would be «alea iacta esto«, let the die be cast.[95] Pompey and many senators fled south, believing that Caesar was marching quickly for Rome.[96] Caesar, after capturing communication routes to Rome, paused and opened negotiations, but they fell apart amid mutual distrust.[97] Caesar responded by advancing south, seeking to capture Pompey to force a conference.[98]

Pompey managed to escape Italy from Brundisium before Caesar could capture him. Heading for Hispania, Caesar left Italy under the control of Mark Antony. After an astonishing 27-day march, Caesar defeated Pompey’s lieutenants, then returned east, to challenge Pompey in Illyria, where, on 10 July 48 BC in the battle of Dyrrhachium, Caesar barely avoided a catastrophic defeat. In an exceedingly short engagement later that year, he decisively defeated Pompey at Pharsalus, Greece, on 9 August 48 BC.[99]

In Rome, Caesar was appointed dictator,[102] with Antony as his Master of the Horse (second in command); Caesar presided over his own election to a second consulship and then, after 11 days, resigned this dictatorship.[102][103] Caesar then pursued Pompey to Egypt, arriving soon after the murder of the general. There, Caesar was presented with Pompey’s severed head and seal-ring, receiving these with tears.[104] He then had Pompey’s assassins put to death.[105]

Caesar then became involved with an Egyptian civil war between the child pharaoh Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator and Cleopatra, his sister, wife, and co-regent queen. Perhaps as a result of the pharaoh’s role in Pompey’s murder, Caesar sided with Cleopatra. He withstood the Siege of Alexandria and later he defeated the pharaoh’s forces at the Battle of the Nile in 47 BC, installing Cleopatra as ruler. Caesar and Cleopatra celebrated their victory with a triumphal procession on the Nile in the spring of 47 BC. The royal barge was accompanied by 400 additional ships, and Caesar was introduced to the luxurious lifestyle of the Egyptian pharaohs.[106]

Caesar and Cleopatra were not married. Caesar continued his relationship with Cleopatra throughout his last marriage – in Roman eyes, this did not constitute adultery – and probably fathered a son called Caesarion. Cleopatra visited Rome on more than one occasion, residing in Caesar’s villa just outside Rome across the Tiber.[106]

Late in 48 BC, Caesar was again appointed dictator, with a term of one year.[103] After spending the first months of 47 BC in Egypt, Caesar went to the Middle East, where he annihilated the king of Pontus; his victory was so swift and complete that he mocked Pompey’s previous victories over such poor enemies.[107] On his way to Pontus, Caesar visited Tarsus from 27 to 29 May 47 BC, where he met enthusiastic support, but where, according to Cicero, Cassius was planning to kill him at this point.[108][109][110] Thence, he proceeded to Africa to deal with the remnants of Pompey’s senatorial supporters. He was defeated by Titus Labienus at Ruspina on 4 January 46 BC but recovered to gain a significant victory at Thapsus on 6 April 46 BC over Cato, who then committed suicide.[111]

After this victory, he was appointed dictator for 10 years.[112] Pompey’s sons escaped to Hispania; Caesar gave chase and defeated the last remnants of opposition in the Battle of Munda in March 45 BC.[113] During this time, Caesar was elected to his third and fourth terms as consul in 46 BC and 45 BC (this last time without a colleague).

Dictatorship and assassination

While he was still campaigning in Hispania, the Senate began bestowing honours on Caesar. Caesar had not proscribed his enemies, instead pardoning almost all, and there was no serious public opposition to him. Great games and celebrations were held in April to honour Caesar’s victory at Munda. Plutarch writes that many Romans found the triumph held following Caesar’s victory to be in poor taste, as those defeated in the civil war had not been foreigners, but instead fellow Romans.[114] On Caesar’s return to Italy in September 45 BC, he filed his will, naming his grandnephew Gaius Octavius (Octavian, later known as Augustus Caesar) as his principal heir, leaving his vast estate and property including his name. Caesar also wrote that if Octavian died before Caesar did, Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus would be the next heir in succession.[115] In his will, he also left a substantial gift to the citizens of Rome.

Between his crossing of the Rubicon in 49 BC, and his assassination in 44 BC, Caesar established a new constitution, which was intended to accomplish three separate goals.[116] First, he wanted to suppress all armed resistance out in the provinces, and thus bring order back to the Republic. Second, he wanted to create a strong central government in Rome. Finally, he wanted to knit together all of the provinces into a single cohesive unit.[116]

The first goal was accomplished when Caesar defeated Pompey and his supporters.[116] To accomplish the other two goals, he needed to ensure that his control over the government was undisputed,[117] so he assumed these powers by increasing his own authority, and by decreasing the authority of Rome’s other political institutions. Finally, he enacted a series of reforms that were meant to address several long-neglected issues, the most important of which was his reform of the calendar.[118]

Dictatorship

When Caesar returned to Rome, the Senate granted him triumphs for his victories, ostensibly those over Gaul, Egypt, Pharnaces, and Juba, rather than over his Roman opponents.[citation needed] When Arsinoe IV, Egypt’s former queen, was paraded in chains, the spectators admired her dignified bearing and were moved to pity.[119] Triumphal games were held, with beast-hunts involving 400 lions, and gladiator contests. A naval battle was held on a flooded basin at the Field of Mars.[120] At the Circus Maximus, two armies of war captives, — each of 2,000 people, 200 horses, and 20 elephants — fought to the death. Again, some bystanders complained, this time at Caesar’s wasteful extravagance. A riot broke out, and stopped only when Caesar had two rioters sacrificed by the priests on the Field of Mars.[120]

After the triumph, Caesar set out to pass an ambitious legislative agenda.[120] He ordered a census be taken, which forced a reduction in the grain dole, and decreed that jurors could come only from the Senate or the equestrian ranks. He passed a sumptuary law that restricted the purchase of certain luxuries. After this, he passed a law that rewarded families for having many children, to speed up the repopulation of Italy. Then, he outlawed professional guilds, except those of ancient foundation, since many of these were subversive political clubs. He then passed a term-limit law applicable to governors. He passed a debt-restructuring law, which ultimately eliminated about a fourth of all debts owed.[120]

The Forum of Caesar, with its Temple of Venus Genetrix, was then built, among many other public works.[121] Caesar also tightly regulated the purchase of state-subsidised grain and reduced the number of recipients to a fixed number, all of whom were entered into a special register.[122] From 47 to 44 BC, he made plans for the distribution of land to about 15,000 of his veterans.[123]

The most important change, however, was his reform of the Roman calendar. The calendar at the time was regulated by the movement of the moon. By replacing it with the Egyptian calendar, based on the sun, Roman farmers were able to use it as the basis of consistent seasonal planting from year to year. He set the length of the year to 365.25 days by adding an intercalary/leap day at the end of February every fourth year.[118]

To bring the calendar into alignment with the seasons, he decreed that three extra months be inserted into 46 BC (the ordinary intercalary month at the end of February, and two extra months after November). Thus, the Julian calendar opened on 1 January 45 BC.[118][120] This calendar is almost identical to the current Western calendar.

Shortly before his assassination, he passed a few more reforms.[120] He appointed officials to carry out his land reforms and ordered the rebuilding of Carthage and Corinth. He also extended Latin rights throughout the Roman world, and then abolished the tax system and reverted to the earlier version that allowed cities to collect tribute however they wanted, rather than needing Roman intermediaries. His assassination prevented further and larger schemes, which included the construction of an unprecedented temple to Mars, a huge theatre, and a library on the scale of the Library of Alexandria.[120]