Несколько тысяч лет назад человечество узнало такой нужный металл как железо. Раньше железо применялось в основном для орудий труда. Сейчас этот металл нашёл более широкое применение. В природе в чистом виде железа не существует. Его добывают из горной породы, которая называется железная руда. Железная руда относится к полезным ископаемым.

Где добывают железную руду

Больше всего этого полезного ископаемого добывается в России: в Курской области, Хакассии, в Красноярском крае, в Томской области. От общего мирового запаса железной руды, в России находится около 20%.

На географической карте залежи этой горной породы обозначают чёрным треугольником.

Состав и виды железной руды

Железную руду разделяют по содержанию в ней железа. Количество железа в руде может колебаться от 16% до 70%. Чем меньше железа, тем больше побочных примесей. Руда с большим количеством примесей требует большей переработки и процесс получения из неё железа слишком трудоёмкий.

В зависимости от количества железа, руда бывает очень богатая, богатая, средняя и бедная.

Среди побочных примесей могут встречаться очень опасные. Это сера, мышьяк, фосфор.

Существует несколько видов этого полезного ископаемого.

Самый богатый по количеству железа – красный железняк. Своё название порода получила из-за красноватого цвета. В красном железняке содержится 70% железа и очень мало различных примесей. В нём мало вредных веществ.

Бурый железняк содержит около 25% железа. Эту породу часто используют в производстве чугуна потому, что его легко перерабатывать.

Большое количество железа содержится в магнитной руде, но это очень редкая горная порода.

Самые бедные по составу железа сидериты. Их запасы также невелики.

Как добывают железную руду

Существует несколько способов добычи железной руды.

— Карьерный. Его используют в том случае, когда порода залегает не очень глубоко, не больше 300 м. Горную породу сначала дробят специальными установками, а потом экскаваторами вытягивают наружу.

— Шахтный. Если пласты породы залегают глубже 300 м, используют шахтный метод. Для этого делают глубокие шахты и в них выдалбливают породы. Затем горную породу подают на верх.

Для чего нужна железная руда

Железную руду используют как для получения железа, так и для получения более твёрдых сплавов: чугуна и стали.

Применяют сплавы для производства станков, ракет, вертолётов, самолётов, различной военной техники, при изготовлении деталей автомобилей, в строительстве, в добывающей промышленности.

Железная руда

4.1

Средняя оценка: 4.1

Всего получено оценок: 69.

Обновлено 5 Июля, 2021

4.1

Средняя оценка: 4.1

Всего получено оценок: 69.

Обновлено 5 Июля, 2021

Ранняя история железных изделий относится к VI–IV тысячелетиям до н. э., однако только в начале I тысячелетия до н. э. придумали способ выплавки железа. Для современной промышленности сплавы железа — это основной металл многих производств. Расскажем о составе руды, способе её добычи и переработки на примере Курской магнитной аномалии, перечислим основные месторождения России.

Что такое железная руда

Железной рудой называют горную породу с включениями определённых минералов железа в достаточном количестве. По содержанию железа руда делится на богатую (более 50 % железа), обычную (25–50 %), бедную (менее 25 %).

В состав наиболее ценных железных руд входят минералы магнетит, гематит, магнетит с примесью титана, ильменит (содержит железо и титан).

Ценность железной руды повышают примеси других металлов, так как при переплавке дополнительно получают ванадий, палладий, платину, золото.

Как добывают железную руду

Добыча железной руды возможна карьерным и шахтным способом. Карьерный способ безопасен для работников, но нарушает окружающую среду. Карьеры обычно имеют глубину до 200–500 м и более.

В карьере регулярно производятся взрывы для откалывания руды от монолитных стенок. Экскаватор грузит обломки в самосвал, который отвозит породу к железнодорожной ветке.

Карьерная техника очень мощная. Так, ковш экскаватора захватывает 23 куб. м. породы, в кузов самосвала можно загрузить 180–220 т руды.

Из карьера руда перевозится на горно-обогатительный комбинат (ГОК), построенный недалеко от места добычи. Продукция ГОКа — брикеты, содержащие не менее 70 % железа.

Самый крупный ГОК России — Лебединский на территории Курской магнитной аномалии. Его карьер, где добывают железную руду, признан крупнейшим в мире.

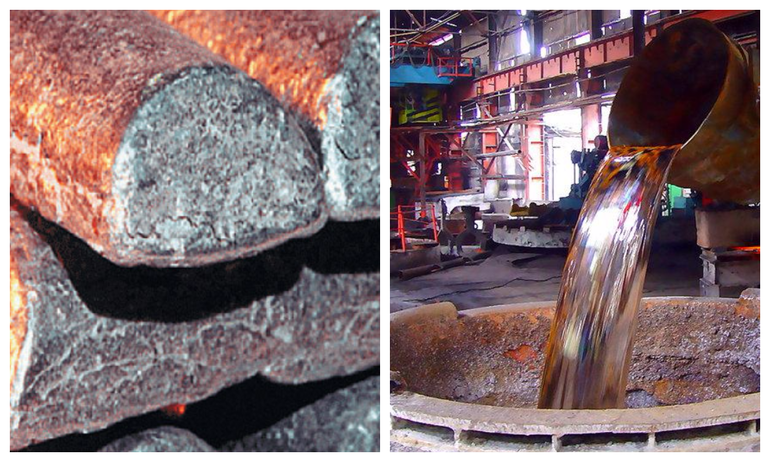

Как плавят руду

Брикеты отправляются дальше, на Оскольский электрометаллургический комбинат (ОЭМК). Здесь в специальной печи брикеты переплавляют, получая сталь нужного состава.

Отсюда сталь поступает на предприятия машиностроения, производства различных металлических изделий, подшипников.

Комбинат поставляет продукцию в США, Германию, Италию, Францию, Норвегию и другие страны.

На ОЭМК применяются современные технологии, что обеспечивает выпуск высококачественной стали и минимальные выбросы в воздух.

Месторождения железных руд России

Россия занимает 5 место в мировом списке стран, добывающих железную руду.

- Крупнейшее в стране и мире месторождение — Курская магнитная аномалия (Курская, Белгородская, Орловская области). Разрабатываются руды с содержанием железа от 32 до 62 %.

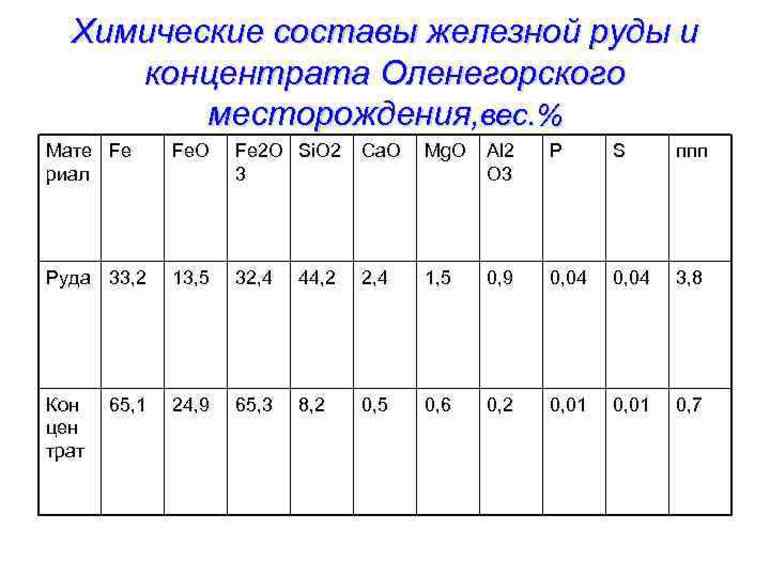

- Месторождения Мурманской области — Оленегорское и Ковдорское железорудные поля.

- В республике Карелия — месторождение Костомукша.

- Качканарское месторождение (Свердловская область) — большие запасы бедных руд.

- Бакчарское месторождение (Томская область) содержит богатые руды, пока не разрабатывается. Предполагается скважинный способ добычи, планируемое начало работ — 2020–2021 год.

Что мы узнали?

Россия богата железной рудой. Разрабатываются несколько крупных месторождений, одно пока в резерве. В докладе для детей по окружающему миру в 4 классе можно кратко описать путь руды от карьера до производства стали.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

Пока никого нет. Будьте первым!

Оценка доклада

4.1

Средняя оценка: 4.1

Всего получено оценок: 69.

А какая ваша оценка?

Образование породы

Если рассматривать железо в качестве химического элемента, то оно входит в состав различных горных пород. Однако не все они используются в качестве сырья для добычи. Железной рудой принято называть лишь те минеральные образования, в которых содержится определенное количество минерала и его извлечение оправдано с экономической точки зрения. В природе железо распространено в виде соединений с различными веществами.

Впервые люди начали заниматься добычей железной руды более двух тысячелетий назад. Благодаря этому появилась возможность производить более прочные металлические изделия в сравнении с медными. В зависимости от происхождения, все минералы, содержащие железо, принято классифицировать на 3 группы:

- Метаморфогенные образования. Появились на месте старых осадочных месторождений под воздействием высокой температуры и давления.

- Экзогенные. Сформировались в долинах рек, благодаря воздействию ветра и воды на горные породы.

- Магматогенные. Были созданы в результате высокотемпературного воздействия.

Следует заметить, что эти группы делятся на большое количество подвидов.

Химический состав

Ценности и свойства руды во многом зависят от количества входящих в ее состав примесей. Именно от этого зависит ценность минерала и принимается решение о целесообразности его добычи. В соответствии с процентным содержанием посторонних веществ руду принято делить на несколько групп:

- Максимально богатая — содержание железа составляет более 65%.

- Богатая — 60−65%.

- Средняя — более 45%.

- Бедная — менее 45%.

Вполне очевидно, что при высоком содержании посторонних веществ для переработки руды требуется затратить больше энергии. Это в свою очередь негативно отражается на стоимости готовых изделий. Добываемая руда является совокупностью всевозможных минералов, посторонних примесей и пустой породы. Соотношение всех этих компонентов во многом зависит от месторождения.

В пустой породе также может содержаться железо, но ее переработка экономически невыгодна. Чаще всего в природе встречаются силикаты, оксиды и карбонаты железа. Кроме этого, порода может содержать и различные вредные примеси, например, фосфор, серу и т. д.

Виды и характеристики руды

Кроме химического состава породы, с экономической точки зрения, важное значение имеет и место, где планируется добывать железо. Самыми богатыми месторождениями являются линейные. Кроме этого, они содержат максимально чистую породу. А также в природе есть плоскоподобные месторождения, сформировавшиеся на поверхности железосодержащих кварцитов.

Чаще всего встречается красный железняк, основанный на оксиде гематита. В этом веществе наблюдается высокое содержание железа, а количество вредных примесей сравнительно невелико. Широко используется еще несколько типов породы:

- Бурый железняк. Это вещество представляет собой оксид и имеет грязно-желтый оттенок.

- Магнитный железняк. Формула вещества — Fe3O4. Встречается реже в сравнении с красным, но нередко содержит свыше 70% полезного минерала. Порода может быть плотной либо зернистой с вкраплениями комочков тёмно-синего оттенка. При добыче эта руда обладает магнитными свойствами, которые исчезают после высокотемпературной обработки.

- Глинистый железняк. Встречается сравнительно редко и, как правило, содержит мало полезного ископаемого.

- Шпатовый железняк. Эта порода содержит сидериты и встречается довольно редко. Из-за низкого содержания полезного минерала ее добыча не выглядит экономически выгодной.

В природе также нередко встречаются карбонаты и силикаты.

Запасы в стране и мире

Крупнейшее месторождение железной руды в России расположено на территории Орловской, Курской и Белгородской области. Следует заметить, что Курская магнитная аномалия является самым мощным источником железа не только в стране, но и во всем мире. Это природное творение столь грандиозно, что обнаружить его смогли еще в XVI столетии. Запас руды в месторождении исчисляется миллиардами тонн.

Бакчарское месторождение — еще один крупный железорудный бассейн в мире. Его местонахождение — междуречье рек Икса и Андорма, протекающих на территории Томской области. Оно было открыто в 60-х годах прошлого столетия во время поиска новых мест для добычи нефти. Площадь бассейна составляет около 16 тыс км2. Порода залегает на глубине 190−220 м.

В среднем добываемая руда содержит около 57% железа, а в обогащенной породе — до 97%. Специалисты оценивают запас руды более, чем в 27 миллиардов тонн. Сегодня в бассейне внедряются новые технологии, и вместо добычи карьерным способом планируется использовать скважинную.

В Красноярском крае находится Абагасское месторождение, открытие которого произошло в далеком 1933 году, однако активная разработка началась лишь в 60-х годах. Главным минералом, добываемым в этом бассейне, является магнетит. Кроме этого, встречается пирит, мушкетовит и гематит. Добыча породы ведется открытым способом, а предполагаемые запасы руды составляют более 70 миллионов тонн.

После Курской магнитной аномалии на мировой карте второе место занимает Криворожское месторождение, расположенное на территории Украины. В Западной Европе мощным источником железа является Лотарингский железорудный бассейн. Он расположен на территории Франции, Бельгии и Люксембурга. Разработка бассейна ведется с XIX столетия, и бо́льшая часть добываемой руды приходится на долю Франции. Общий запас руды предположительно составляет около 15 миллиардов тонн.

Добыча породы ведется подземным способом. По данным геологической службы Соединенных Штатов, основные месторождения железа находятся в России, Украине, Китае, Бразилии и Австралии.

Особенности добычи

Разработка месторождений может проводиться открытым или подземным способом. Второй метод наносит меньший ущерб природе, но при этом является более трудоемким. Добытую породу доставляют на комбинат, где сырье необходимо предварительно измельчить. Затем руда обогащается, железо отделяется от других элементов.

Эта процедура может проводиться несколькими способами:

- Гравитационная сепарация. Куски породы обладают различной плотностью и распадаются под механическим воздействием, например, в результате вибрации.

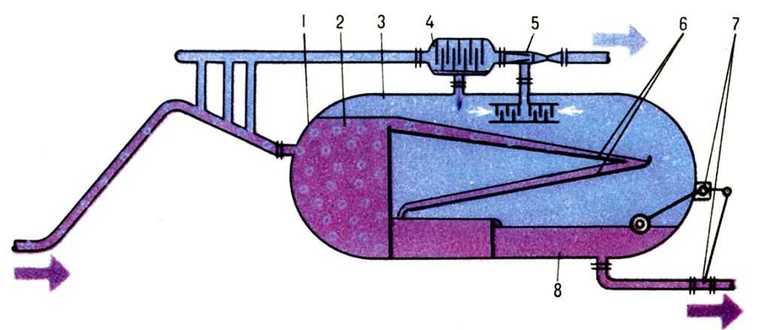

- Флотация. Мелкоизмельченное сырье помещается в специальную камеру, в которую затем подается воздух и рабочая жидкость. Частички железа соединяются с воздушными пузырьками и поднимаются.

- Магнитная сепарация. Полезный минерал оттягивается с помощью магнитов.

- Комбинированный. Для отделения железа от пустой породы используется сразу несколько способов.

Полученный рудной концентрат затем отправляется на металлургический комбинат.

Область использования

Сфера применения руды ограничена металлургическим производством. Она является основным сырьем для производства чугуна и различных сплавов. Таким образом, из руды делают различные металл. Однако еще 2 тысячи лет назад люди поняли, что в чистом виде железо незначительно превосходит бронзу в твердости. В результате был открыт сплав железа и углерода, который называется сталь или чугун. В первом типе материала содержится 0,1−2,14% углерода.

Следует заметить, что длительное время чугун не использовался для производства предметов. Металлурги прошлого считали его браком из-за низкой пластичности. Лишь после изобретения пушек этот материал начали применять для производства ядер. Сегодня ситуация серьезно изменилась, и чугун используется в различных областях. Лидером в черной металлургии является Китай. Эта страна значительно превосходит другие государства в производстве чугуна и сталей. При этом ведущими экспортерами являются Австралия и Бразилия.

Мировой экономике требуется все больше сырья, и во многих странах месторождения железной руды активно разрабатываются. Однако развитые государства зачастую предпочитают сократить объем собственного производства, предпочитая экспортировать относительно недорогой материал. Хотя мировые запасы железа и кажутся огромными, они все же не являются неисчерпаемыми.

- Энциклопедия

- Разное

- Железная руда

Железо — это прочный металл, использовать который, люди начали еще много веков назад. Но найти его в чистом виде невозможно. Оно содержится во многих горных породах в виде соединения с другими минералами. Так вот, самое большое содержание железа находится в железной руде. Поэтому получение железа из руды считается самым экономически выгодным.

Вся железная руда, в зависимости от ее месторождения, очень сильно отличается по своему химическому составу. В ней содержится разное количество вредных и полезных примесей. И доля железа в ней очень разная. Следуя из этого, руду разделяют на несколько видов. Та горная порода, содержание железа в которой превышает более 57- 65% называется богатой железной рудой. Если в ее составе примерно половина железа эта руда является рядовой или средней. Ну, а если руда содержит совсем мало железа то ее называют бедной. Самой богатой горной породой, является красный железняк. В его составе насчитывается более семидесяти процентов содержания железа и минимальное количество примесей.

Залежей железной руды на нашей планете очень много. Но ее начинают добывать только в том случае, если она содержит большое количество железа. Что бы добыча была экономически выгодна. Добывают это полезное ископаемое, как правило, открытым способом. Для этого разрабатывают карьеры, где на глубине примерно пол километра и происходит добыча. С помощью специального оборудования отделяют руду от ненужной породы. Грузят на машины и отправляют на дальнейшую переработку. Если месторождение находится на большой глубине, добычу ведут в специально построенных шахтах. Но это дорогой и очень опасный вид получения руды.

Металлургия — это основная отрасль промышленности, где применяют железную руду. Она является сырьем для производства чугуна. Который производят в доменных печах. Затем чугун поступает в мартеновские печи, где соединяясь с углеродом получается сталь.

На сегодняшний день чугун и сталь используется во многих сферах жизни и деятельности человека, в том числе и во всех видах промышленного производства. Машиностроение, легкая и пищевая промышленность, строительство — это очень маленькая часть отраслей, которые вообще не могут существовать без этих металлов. Поэтому мировая добыча железной руды интенсивно возрастает с каждым годом. Основными на рынке добычи этого полезного ископаемого есть такие страны как Россия, Украина, Бразилия, Австралия, Индия и Китай.

Доклад №2

Добывать руду люди стали очень давно. Переход к железному веку от бронзового произошел между II и I тысячелетий до нашей эры.

Железо – это распространенный элемент. В недрах планы его содержание доходит до 5 процентов. Железо в чистом виде не встречается, оно входит в состав железной руды.

Железная руда – это минеральный ресурс, содержащий железо, которое можно извлечь для промышленного применения. Содержание железа в руде неодинаково и имеет достаточно большой диапазон. Если в руде железо составляет меньше половины остальных элементов, то ее называют бедной. А если железа больше 50%, то называют богатой. Содержание железа в руде может доходить до 70%.

Видов железных руд довольно много. Чаще всего встречается красный железняк, содержащий минерал гематит. В нем содержится много железа. Эта руда имеет красный цвет. Она считается лучшей из всех железных руд, так как содержит мало опасных веществ и легко восстанавливается. Богатое месторождение такой руды находится в Кривом Роге. Часто встречается в виде кристаллов. Красные железные руды распространены в природе. Гематитовые руды используются для выплавки чугуна. Гематит может быть получен искусственным путем.

Бурый железняк содержит в составе воду. В его составе меньше железа, чем в красном. Чистый бурый железняк содержат разнообразные опасные примеси, такие как фосфор и сера, мышьяк. Бурый железняк удобен в добыче и легкоплавок, однако железо из него обычно получается невысокого качества. Встречается в форме порошка или плотных кусков.

Магнитная руда имеют в основе оксид, обладающий магнитными свойствами. В ней так же много железа, как и в красном железняке, но по своему количеству в природе она уступает ему. Магнитная руда имеет равномерную структуру. Месторождения таких руд имеют магматическое происхождение. Сначала железистая магма была жидкой, а затем со временем закристаллизовалась. Этот процесс очень сложен.

Сидериты – это бедные по содержанию железа руды. Разновидности этих руд можно встретить на Урале. Запасы сидерита невелики.

Железные руды неоднородно распределены на планете. Обычно железные руды залегают среди древних геологических образований палеозойской и архейской группы. По форме залегания железные руды разнообразны. Встречаются залегания в виде жил, гнезд, пластов, залежей, поверхностных масс. Богатые месторождения есть в США, Канаде, Южной Африке, Индии, Австралии. На территории России тоже есть месторождения железной руды. На долю России приходится 18 процентов мировых запасов железа.

Способ добычи железной руды зависит от глубины ее залегания.

Самый распространенный способ добычи – карьерный. Он используется для добычи залежей с глубины до 300 метров. На карьерах используются экскаваторы и установки для дробления породы.

Шахтный метод применяется при залегании пластов руды на глубине до 900 метров. Из шахты порода подается с помощью транспортера.

Еще есть скважинная гидродобыча железной руды, которая в настоящее время почти не используется.

Железная руда применяется в металлургии. Из железной руды производят такие сплавы как чугун и сталь. Сплавы железа используются в автомобилестроении, военной промышленности, строительстве зданий, пищевой промышленности.

Для 3, 4 класса, по окружающему миру. Краткое содержание

Железная руда

Популярные темы сообщений

- Жесткий диск

Компьютер – незаменимое на сегодняшний день средство для выполнения огромного количества задач. Именно широкий перечень возможностей компьютера обуславливает необходимость хранения большого количества содержимого внутри него.

- Репродуктивное здоровье человека

Здоровье человека в самом широком смысле слова – это не только отсутствие каких-либо ярко выраженных заболеваний, но и гармоничное стабильное развитие психологической, физической, умственной и прочих сфер его жизнедеятельности.

- Мимоза

Одним из самых нежных цветов, которые появляются с наступлением тепла, является мимоза. Большинство считают ее цветком, а в сущности это кустарник. Зовут ее — акация серебристая, а еще по-другому – акация австралийская,

- Закон спроса и предложения

Данный закон является экономическим рыночным законом, утверждающим, что между объемом предложения и спроса на товары, а также установленными на них ценами, существует прямая зависимость.

- Пшеница

Пшеница – травянистое, однолетнее растение, относится к семейству злаковых культур. Ее начали выращивать более 10 тысяч лет назад. В Древнем Египте, при раскопках гробниц были найдены зерна пшеницы.

Содержание

- Железная руда

- Что такое железная руда

- Как добывают железную руду

- Как плавят руду

- Месторождения железных руд России

- Что мы узнали?

Железная руда

Ранняя история железных изделий относится к VI–IV тысячелетиям до н. э., однако только в начале I тысячелетия до н. э. придумали способ выплавки железа. Для современной промышленности сплавы железа — это основной металл многих производств. Расскажем о составе руды, способе её добычи и переработки на примере Курской магнитной аномалии, перечислим основные месторождения России.

Что такое железная руда

Железной рудой называют горную породу с включениями определённых минералов железа в достаточном количестве. По содержанию железа руда делится на богатую (более 50 % железа), обычную (25–50 %), бедную (менее 25 %).

В состав наиболее ценных железных руд входят минералы магнетит, гематит, магнетит с примесью титана, ильменит (содержит железо и титан).

Рис. 1. Магнетит.

Ценность железной руды повышают примеси других металлов, так как при переплавке дополнительно получают ванадий, палладий, платину, золото.

Как добывают железную руду

Добыча железной руды возможна карьерным и шахтным способом. Карьерный способ безопасен для работников, но нарушает окружающую среду. Карьеры обычно имеют глубину до 200–500 м и более.

В карьере регулярно производятся взрывы для откалывания руды от монолитных стенок. Экскаватор грузит обломки в самосвал, который отвозит породу к железнодорожной ветке.

Карьерная техника очень мощная. Так, ковш экскаватора захватывает 23 куб. м. породы, в кузов самосвала можно загрузить 180–220 т руды.

Из карьера руда перевозится на горно-обогатительный комбинат (ГОК), построенный недалеко от места добычи. Продукция ГОКа — брикеты, содержащие не менее 70 % железа.

Самый крупный ГОК России — Лебединский на территории Курской магнитной аномалии. Его карьер, где добывают железную руду, признан крупнейшим в мире.

Рис. 2. Лебединский ГОК, карьер.

Как плавят руду

Брикеты отправляются дальше, на Оскольский электрометаллургический комбинат (ОЭМК). Здесь в специальной печи брикеты переплавляют, получая сталь нужного состава.

Отсюда сталь поступает на предприятия машиностроения, производства различных металлических изделий, подшипников.

Комбинат поставляет продукцию в США, Германию, Италию, Францию, Норвегию и другие страны.

На ОЭМК применяются современные технологии, что обеспечивает выпуск высококачественной стали и минимальные выбросы в воздух.

Рис. 3. ОЭМК, выплавка стали.

Месторождения железных руд России

Россия занимает 5 место в мировом списке стран, добывающих железную руду.

- Крупнейшее в стране и мире месторождение — Курская магнитная аномалия (Курская, Белгородская, Орловская области). Разрабатываются руды с содержанием железа от 32 до 62 %.

- Месторождения Мурманской области — Оленегорское и Ковдорское железорудные поля.

- В республике Карелия — месторождение Костомукша.

- Качканарское месторождение (Свердловская область) — большие запасы бедных руд.

- Бакчарское месторождение (Томская область) содержит богатые руды, пока не разрабатывается. Предполагается скважинный способ добычи, планируемое начало работ — 2020–2021 год.

Что мы узнали?

Россия богата железной рудой. Разрабатываются несколько крупных месторождений, одно пока в резерве. В докладе для детей по окружающему миру в 4 классе можно кратко описать путь руды от карьера до производства стали.

Предыдущая

Окружающий мирОхрана воздуха от загрязнения – сообщение кратко (3 класс, окружающий мир)

Следующая

Окружающий мирПесец – чем питается зверь, среда обитания, рассказ для сообщения для детей

В учебниках по окружающему миру и в первом, и во втором, и в третьем, и в четвертом классе изучаю камни, руды и минералы. Часто учитель задает на дом подготовить сообщение, доклад или презентацию о какой-нибудь руде на выбор ученика. Одна из самых популярных и необходимых в жизни людей — железная руда. О ней и поговорим.

Железная руда

Я расскажу о железной руде. Железная руда — основной источник получения железа. Она, как правило, черного цвета, слегка блестит, со временем рыжеет, очень твердая, притягивает металлические предметы.

Почти все основные месторождения железной руды находятся в породах, которые образовались больше миллиарда лет назад. В то время земля была покрыта океанами. В составе планеты было много железа и в воде находилось растворенное железо. Когда в воде появились первые организмы, создающие кислород, он стал вступать в реакцию с железом. Получившиеся вещества оседали в большом количестве на морском дне, спрессовывались, превращались в руду. Со временем вода ушла, и теперь человек добывает эту железную руду.

Так же железная руда образуется при высоких температурах, например при извержении вулкана. Именно поэтому ее залежи находят и в горах.

Бывают разные виды руды: магнитный железняк, красный и бурый железняк, железный шпат.

Железная руда есть повсеместно, но добывают ее обычно только там, где в составе руды хотя бы половина — это соединения железа. В России месторождения железной руды находятся на Урале, Кольском полуострове, на Алтае, в Карелии, но самое большое в России и в мире месторождение железной руды — Курская магнитная аномалия.

Залежи руды на её территории оцениваются в 200 миллиардов тонн. Это составляет около половины всех запасов железной руды на планете. Она располагается на территории Курской, Белгородской и Орловской областей. Там находится самый большой в мире карьер для добычи железной руды — Лебединский ГОК. Это огромная яма. Карьер достигает 450 метров в глубину и около 5 км в ширину.

Сначала руду взрывают, чтобы раздробить на куски. Экскаваторы на дне карьера набирают эти куски в огромные самосвалы. Самосвалы загружают железную руду в специальные вагоны поездов, которые вывозят ее из карьера и везут на переработку на комбинат.

На комбинате руду измельчают, потом отправляют на магнитный барабан. Все железное прилипает к барабану, а не железное – смывается водой. Железо собирают и переплавляют в брикеты. Теперь из него можно плавить сталь и делать изделия.

Сообщение подготовил

ученик 4Б класса

Максим Егоров

Железная руда – важный ископаемый продукт, который человечество стало добывать много столетий назад. С давних времён железо нашло широкое применение в бытовых и прочих условиях жизни человеческого общества. Одно из ключевых преимуществ и свойств железной руды – возможность изготовления стали, получаемой в процессе её плавки.

Содержание

- 1 Как выглядит руда железа и что собой представляет?

- 2 Характер происхождения

- 2.1 Основные свойства и типы. Из какой руды получают железо?

- 2.2 Географическое расположение ключевых месторождений

- 3 Значение железной руды и сферы, в которых она используется

- 4 Способы добычи

- 5 Как обогащаются железорудные материалы?

Руда железа может иметь различные свойства, минеральный состав, а также процентное соотношение примесей и металлов в зависимости от типа и места её разработки. Найти места добычи железорудных минералов с соответствующим техническим оснащением не представляется сложной задачей, поскольку железо составляет более 5% твёрдых залежей земной коры по всей поверхности планеты. Согласно Википедии и другим достоверным источникам, железная руда занимает четвёртое место по распространённости среди полезных ископаемых, добываемых в окружающем мире.

Тем не менее, найти этот металл в природе в чистом виде не представляется возможным – отыскать его можно в определённых количествах в большинстве известных типов и вида камня (горных пород). Минералы (железорудные) одни из наиболее выгодных в плане добычи. От характера происхождения железной руды зависит количественное содержание в ней железа.

Как выглядит руда железа и что собой представляет?

В качестве ключевого химического элемента железо входит в состав множества горных пород. Тем не менее, далеко не каждая такая порода может быть потенциальным сырьевым продуктом для добычи и разработки. Целесообразность разработки железных руд, как таковых, во многом зависит от процентного состава.

Его добычей плотно занялись более 3 тысяч лет назад, что обусловлено возможностью изготавливать на основе железа более качественных и прочных изделий в сравнении с бронзой и медью, которые стали добываться ещё раньше. Уже в те времена, мастера, работавшие с плавильнями, могли точно различать виды железной руды.

В настоящее время принято выделять несколько типов сырья, пригодного для последующей выплавки полезного металла:

- магнетиновый;

- магнетино-апатитный;

- магнетино-титановый;

- гидрогетит-гетитовый;

- гематито-магнетиновый.

Богатым считается месторождение железной руды с процентным составным содержанием железа 57%. Но, как уже было сказано выше, целесообразными могут быть разработки залежей, в которых руда содержит 26% этого полезного металла. В составе горных пород железо преобладает в виде оксидов. Остальные составляющие представляют собой фосфор, серу и кремнезёмы.

Существуют таблицы железной руды, в которых отражен её сырьевой, химический состав и процентное содержание железа. Если руководствоваться численными показателями большинства таких таблиц, то условно можно разделить ценные руды по степени их богатства и свойствам на 4 категории

- очень богатые – содержание основного металла более 65%;

- умеренно богатые – средний процент железа 60-65%;

- умеренные – от 45% и более;

- бедные – менее 45% добываемых полезных элементов в целом.

В зависимости от количества побочных примесей, входящих в состав разрабатываемого месторождения железа, требуется большее или меньшее количество энергии на переработку. От этого во многом зависит эффективность производства готовой продукции на основе железа.

Характер происхождения

Большая часть известных рудниковых типов была сформирована под влиянием трёх основных факторов. От них, собственно, зависят особенности и характеристики руды железа.

Магматическое формирование. Магматические составы формировались под воздействием высоких температур магмы либо при условии высокой активности древних вулканов. По сути, имели место естественные процессы перемешивания и переплавки горных пород.

Эта разновидность полезных ископаемых представляет собой кристаллические минеральные ископаемые соединения, отличающиеся высоким процентом содержания железа. Залежи магматических ископаемых, как правило, можно обнаружить в зонах старинного образования гористых местностей. Именно в этих местах расплавленные вещества подходили максимально близко к поверхностным слоям почвы.

Метаморфическое формирование. В процессе такого формирования образуются минералы осадочного типа. Суть этого процесса сводится к передвижению отдельных участков коры Земли при котором определённые пласты, богатые определёнными элементами, попадают под породы, залёгшие выше.

Полезные ископаемые, которые образовались при очередном перемещении, мигрируют ближе к земляной поверхности. Железная руда, которая образуется в процессе метаморфического формирования, как правило, имеет высокое процентное содержание полезных металлических соединений и располагается не слишком глубоко от поверхности. Один из наиболее распространённых примеров – железняк магнитный, содержащий в своём составе до 75% железа.

Осадочное формирование. В данном случае основные факторы этого типа формирования рудников – естественные силы природы, в частности ветры и вода. Пласты породы подвергаются разрушению и перемещению в низины – именно здесь они скапливаются, формируя отдельные слои. В качестве реагента выступает вода, которая выщелачивает исходные материалы. В ходе таких процессов формируются залежи бурого железняка, представляющего собой рассыпчатую, разрыхлённую массу с высоким содержанием минеральных примесей и процентным содержанием железа до 35-40%.

За счёт различной специфики образования метаморфических пород сырьё часто перемешивается внутри пластов с магматической породой, известняком и глиной. В одном и том же месторождении, обозначенном соответствующим знаком на карте, обнаруживаются различные по происхождению залежки, которые перемешаны между собой. Места, предположительно богатые осадочными железными рудами в этом случае определяются в ходе геологических разведочных мероприятий.

Основные свойства и типы. Из какой руды получают железо?

К наиболее распространённому типу принято относить красный железняк, основой которого служит гематитовый оксид. В его составе содержится минимум побочных примесей и свыше 70% железа.

Следующий по распространённости – бурый железняк (лимонит), представляющий собой оксид железа, содержащий в своём составе H2O. Как правило, в состав лимонита входит порядка четверти процентного содержания железа. В природе бурый железняк можно встретить в форме пористых, рыхлых пород, содержащих фосфор и марганец. В качестве пустой породы в руде содержится глина.

Магнитная руда железа содержит в своём составе магнитный оксид, свойства которого теряются в условиях сильного нагрева. В природе встречается намного реже вышеперечисленных пород и по процентному соотношению железа в некоторых случаях не уступает красному железняку.

Железняк шпатовый – рудная порода, содержащая сидерит с высоким содержанием глины в составе. Это весьма редкая порода, а за счёт малого содержания железа добывают его намного реже, особенно если речь идёт о промышленном применении.

Помимо оксидов существуют другие железорудные типы, в основу которых входят карбонаты и силикаты.

Географическое расположение ключевых месторождений

Все основные месторождения принято делить на:

- Метаморфогенные – кварцитовые залежи;

- Экзогенные – бурый железняк и прочие осадочные породы;

- Эндогенные – преимущественно титаномагнетитовые составы.

Подобные рудные залежи встречаются практически на каждом континенте. Большая часть железорудных залежей находится на территории стран СНГ, в частности это территория Казахстана, России и Украины. Достаточно большими запасами железорудных скоплений могут похвастать такие государства, как ЮАР, Индия, США, Австралия, Канада и Бразилия. Существуют карты месторождений железной руды, как в мировых масштабах, так и с более подробным указанием залежей на территории конкретного государства.

Значение железной руды и сферы, в которых она используется

По преимуществу все отрасли, в которых задействованы эти полезные ископаемые, связаны с металлургической сферой. По большей части руду железа используют при выплавке чугуна с использованием конверторной или мартеновской печи. В свою очередь чугун широко применим во многих промышленных отраслях.

Сегодня крайне популярен и активно изготавливается и другой сверхпрочный, антикоррозийный сплав – сталь, для чего также используются железорудные ископаемые. Это наиболее популярный промышленный сплав, который славится устойчивостью к коррозии и высокой прочностью.

Стальные и чугунные материалы применяют в следующих отраслях:

- ракетостроительная и военная промышленность, производство специальной техники;

- машиностроение, включая изготовление станков и прочих заводских механизмов;

- автомобильное производство (изготавливаются автомобильные рамы, элементы двигателей, корпуса и прочие механические узлы);

- добывающая промышленность (производство тяжёлого добывающего оборудования и прочей спецтехники);

- строительство – армирующие материалы, создание несущего каркаса.

Способы добычи

Методы и способы извлечения рудных ископаемых ресурсов из недр зависят от глубины, на которой залегает искомый материал. В этом контексте принято выделять три основных способа:

Скважинный метод (гидродобыча) – для работы таким способом специалисты бурят скважины, достигающие пластов пород. В образовавшиеся створы помещаются трубчатые конструкции, через которые мощной водной струёй производится дробление материала и её извлечение. Это наименее эффективный, косный и устаревший метод, который в наши дни используется достаточно редко.

Шахтенный метод – используется при условии, что пласты залегают более глубоко (до 900 метров). Прежде всего прорубаются шахтенные створы – от них по пласту разрабатываются штреки. Порода дробится и поступает на поверхность по специальным транспортёрам.

Карьерный метод – в отличие от скважинного, считается наиболее распространённым. Его используют для работы на средней глубине (до 300 метров). Для разработки применяются мощные экскаваторы и механизмы, дробящие породу. После дробления материал отгружают и транспортируют прямиком на обогатительный комбинат.

Как обогащаются железорудные материалы?

В силу существования различных типов руд по степени того, сколько железа содержится в руде, менее обогащённые материалы отправляются на специальные комбинаты, где они подвергаются сортировке, дроблению, сепарации и агломерации.

В целом можно выделить 4 основных метода рудного обогащения:

Флотация. Специально подготовленная пылеобразная масса погружается в H2O с добавлением воздуха и веществ, которые называются флотационными реагентами. Отсюда и название самого процесса – флотация. Они соединяют частицы железа с пузырьками воздуха и поднимает их на поверхность в пенистом виде. Пустые породы оседают на дне.

Магнитная сепарация. Самый распространённый способ, основанный на разнице воздействия магнетизма на различные составляющие рудной массы. Сепарация может проводиться в случае с мокрыми и сухими породами. В ходе переработки используются барабанные механизмы, оснащённые мощными электромагнитными элементами.

Гравитационная очистка. Для её проведения используются специальные суспензии с плотностью ниже плотности железа и выше плотности пустых пород. Естественные силы гравитации выталкивают побочные составляющие кверху, а суспензия вбирает в себя частицы железа и оставляет их снизу.

Промывка. Используется для устранения из добываемых материалов песков и глины – для их отделения достаточно использовать водную струю под большим напором. Процесс происходит под высоким давлением и обеспечивает до 5% обогащения. Это сравнительно малый показатель, потому этот метод всегда используется в паре с другими способами.

Hematite: the main iron ore in Brazilian mines.

Stockpiles of iron ore pellets like this one are used in steel production.

Iron ore being unloaded at docks in Toledo, Ohio.

Iron ores[1] are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the form of magnetite (Fe

3O

4, 72.4% Fe), hematite (Fe

2O

3, 69.9% Fe), goethite (FeO(OH), 62.9% Fe), limonite (FeO(OH)·n(H2O), 55% Fe) or siderite (FeCO3, 48.2% Fe).

Ores containing very high quantities of hematite or magnetite (greater than about 60% iron) are known as «natural ore» or «direct shipping ore», meaning they can be fed directly into iron-making blast furnaces. Iron ore is the raw material used to make pig iron, which is one of the main raw materials to make steel—98% of the mined iron ore is used to make steel.[2] In 2011 the Financial Times quoted Christopher LaFemina, mining analyst at Barclays Capital, saying that iron ore is «more integral to the global economy than any other commodity, except perhaps oil».[3]

Sources[edit]

Metallic iron is virtually unknown on the surface of the Earth except as iron-nickel alloys from meteorites and very rare forms of deep mantle xenoliths. Some iron meteorites are thought to have originated from accreted bodies 1,000 km in diameter or larger[4] The origin of iron can be ultimately traced to the formation through nuclear fusion in stars, and most of the iron is thought to have originated in dying stars that are large enough to collapse or explode as supernovae.[5] Although iron is the fourth-most abundant element in the Earth’s crust, composing about 5%, the vast majority is bound in silicate or, more rarely,x carbonate minerals (for more information, see iron cycle). The thermodynamic barriers to separating pure iron from these minerals are formidable and energy-intensive; therefore, all sources of iron used by human industry exploit comparatively rarer iron oxide minerals, primarily hematite.

Prior to the industrial revolution, most iron was obtained from widely available goethite or bog ore, for example, during the American Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. Prehistoric societies used laterite as a source of iron ore. Historically, much of the iron ore utilized by industrialized societies has been mined from predominantly hematite deposits with grades of around 70% Fe. These deposits are commonly referred to as «direct shipping ores» or «natural ores». Increasing iron ore demand, coupled with the depletion of high-grade hematite ores in the United States, led after World War II to the development of lower-grade iron ore sources, principally the utilization of magnetite and taconite.

Iron ore mining methods vary by the type of ore being mined. There are four main types of iron ore deposits worked currently, depending on the mineralogy and geology of the ore deposits. These are magnetite, titanomagnetite, massive hematite and pisolitic ironstone deposits.

Banded iron formations[edit]

2.1-billion-year-old rock showing banded iron formation.

Processed taconite pellets with reddish surface oxidation as used in the steelmaking industry, with a U.S. quarter (diameter: 24 mm [0.94 in]) shown for scale.

Banded iron formations (BIFs) are sedimentary rocks containing more than 15% iron composed predominantly of thinly bedded iron minerals and silica (as quartz). Banded iron formations occur exclusively in Precambrian rocks, and are commonly weakly to intensely metamorphosed. Banded iron formations may contain iron in carbonates (siderite or ankerite) or silicates (minnesotaite, greenalite, or grunerite), but in those mined as iron ores, oxides (magnetite or hematite) are the principal iron mineral.[6] Banded iron formations are known as taconite within North America.

The mining involves moving tremendous amounts of ore and waste. The waste comes in two forms: non-ore bedrock in the mine (overburden or interburden locally known as mullock), and unwanted minerals, which are an intrinsic part of the ore rock itself (gangue). The mullock is mined and piled in waste dumps, and the gangue is separated during the beneficiation process and is removed as tailings. Taconite tailings are mostly the mineral quartz, which is chemically inert. This material is stored in large, regulated water settling ponds.

Magnetite ores[edit]

The key parameters for magnetite ore being economic are the crystallinity of the magnetite, the grade of the iron within the banded iron formation host rock, and the contaminant elements which exist within the magnetite concentrate. The size and strip ratio of most magnetite resources is irrelevant as a banded iron formation can be hundreds of meters thick, extend hundreds of kilometers along strike, and can easily come to more than three billion or more tonnes of contained ore.

The typical grade of iron at which a magnetite-bearing banded iron formation becomes economic is roughly 25% iron, which can generally yield a 33% to 40% recovery of magnetite by weight, to produce a concentrate grading in excess of 64% iron by weight. The typical magnetite iron ore concentrate has less than 0.1% phosphorus, 3–7% silica and less than 3% aluminium.

Currently magnetite iron ore is mined in Minnesota and Michigan in the U.S., Eastern Canada and Northern Sweden.[7] Magnetite-bearing banded iron formation is currently mined extensively in Brazil, which exports significant quantities to Asia, and there is a nascent and large magnetite iron ore industry in Australia.

Direct-shipping (hematite) ores[edit]

Direct-shipping iron ore (DSO) deposits (typically composed of hematite) are currently exploited on all continents except Antarctica, with the largest intensity in South America, Australia and Asia. Most large hematite iron ore deposits are sourced from altered banded iron formations and rarely igneous accumulations.

DSO deposits are typically rarer than the magnetite-bearing BIF or other rocks which form its main source or protolith rock, but are considerably cheaper to mine and process as they require less beneficiation due to the higher iron content. However, DSO ores can contain significantly higher concentrations of penalty elements, typically being higher in phosphorus, water content (especially pisolite sedimentary accumulations) and aluminium (clays within pisolites). Export-grade DSO ores are generally in the 62–64% Fe range.[8]

Magmatic magnetite ore deposits[edit]

Occasionally granite and ultrapotassic igneous rocks segregate magnetite crystals and form masses of magnetite suitable for economic concentration.[9] A few iron ore deposits, notably in Chile, are formed from volcanic flows containing significant accumulations of magnetite phenocrysts.[10] Chilean magnetite iron ore deposits within the Atacama Desert have also formed alluvial accumulations of magnetite in streams leading from these volcanic formations.

Some magnetite skarn and hydrothermal deposits have been worked in the past as high-grade iron ore deposits requiring little beneficiation. There are several granite-associated deposits of this nature in Malaysia and Indonesia.

Other sources of magnetite iron ore include metamorphic accumulations of massive magnetite ore such as at Savage River, Tasmania, formed by shearing of ophiolite ultramafics.

Another, minor, source of iron ores are magmatic accumulations in layered intrusions which contain a typically titanium-bearing magnetite often with vanadium. These ores form a niche market, with specialty smelters used to recover the iron, titanium and vanadium. These ores are beneficiated essentially similar to banded iron formation ores, but usually are more easily upgraded via crushing and screening. The typical titanomagnetite concentrate grades 57% Fe, 12% Ti and 0.5% V

2O

5.[citation needed]

Mine tailings[edit]

For every 1 ton of iron ore concentrate produced approximately 2.5–3.0 tons of iron ore tailings will be discharged. Statistics show that there are 130 million tons of iron ore discharged every year. If, for example, the mine tailings contain an average of approximately 11% iron there would be approximately 1.41 million tons of iron wasted annually.[11] These tailings are also high in other useful metals such as copper, nickel, and cobalt,[12] and they can be used for road-building materials like pavement and filler and building materials such as cement, low-grade glass, and wall materials.[11][13][14] While tailings are a relatively low-grade ore, they are also inexpensive to collect as they don’t have to be mined. Because of this companies such as Magnetation have started reclamation projects where they use iron ore tailings as a source of metallic iron.[11]

The two main methods of recycling iron from iron ore tailings are magnetizing roasting and direct reduction. Magnetizing roasting uses temperatures between 700 and 900 °C for a time of under 1 hour to produce an iron concentrate (Fe3O4) to be used for iron smelting. For magnetizing roasting it is important to have a reducing atmosphere to prevent oxidization and the formation of Fe2O3 because it is harder to separate as it is less magnetic.[11][15] Direct reduction uses hotter temperatures of over 1000 °C and longer times of 2–5 hours. Direct reduction is used to produce sponge iron (Fe) to be used for steel making. Direct reduction requires more energy as the temperatures are higher and the time is longer and it requires more reducing agent than magnetizing roasting.[11][16][17]

[edit]

Lower-grade sources of iron ore generally require beneficiation, using techniques like crushing, milling, gravity or heavy media separation, screening, and silica froth flotation to improve the concentration of the ore and remove impurities. The results, high-quality fine ore powders, are known as fines.

Magnetite[edit]

Magnetite is magnetic, and hence easily separated from the gangue minerals and capable of producing a high-grade concentrate with very low levels of impurities.

The grain size of the magnetite and its degree of commingling with the silica groundmass determine the grind size to which the rock must be comminuted to enable efficient magnetic separation to provide a high purity magnetite concentrate. This determines the energy inputs required to run a milling operation.

Mining of banded iron formations involves coarse crushing and screening, followed by rough crushing and fine grinding to comminute the ore to the point where the crystallized magnetite and quartz are fine enough that the quartz is left behind when the resultant powder is passed under a magnetic separator.

Generally most magnetite banded iron formation deposits must be ground to between 32 and 45 micrometers in order to produce a low-silica magnetite concentrate. Magnetite concentrate grades are generally in excess of 70% iron by weight and usually are low phosphorus, low aluminium, low titanium and low silica and demand a premium price.

Hematite[edit]

Due to the high density of hematite relative to associated silicate gangue, hematite beneficiation usually involves a combination of beneficiation techniques.

One method relies on passing the finely crushed ore over a slurry containing magnetite or other agent such as ferrosilicon which increases its density. When the density of the slurry is properly calibrated, the hematite will sink and the silicate mineral fragments will float and can be removed.[18]

Production and consumption[edit]

Evolution of the extracted iron ore grade in different countries (Canada, China, Australia, Brazil, United States, Sweden, USSR-Russia, world). The recent drop in world ore grade is due to the big consumption of low-grade Chinese ores. The American ore is upgraded between 61% to 64% before being sold.[19]

| Country | Production |

|---|---|

| Australia | 817 |

| Brazil | 397 |

| China | 375* |

| India | 156 |

| Russia | 101 |

| South Africa | 73 |

| Ukraine | 67 |

| United States | 46 |

| Canada | 46 |

| Iran | 27 |

| Sweden | 25 |

| Kazakhstan | 21 |

| Other countries | 132 |

| Total world | 2,280 |

Iron is the world’s most commonly used metal—steel, of which iron ore is the key ingredient, representing almost 95% of all metal used per year.[3] It is used primarily in structures, ships, automobiles, and machinery.

Iron-rich rocks are common worldwide, but ore-grade commercial mining operations are dominated by the countries listed in the table aside. The major constraint to economics for iron ore deposits is not necessarily the grade or size of the deposits, because it is not particularly hard to geologically prove enough tonnage of the rocks exist. The main constraint is the position of the iron ore relative to market, the cost of rail infrastructure to get it to market and the energy cost required to do so.

Mining iron ore is a high-volume, low-margin business, as the value of iron is significantly lower than base metals.[22] It is highly capital intensive, and requires significant investment in infrastructure such as rail in order to transport the ore from the mine to a freight ship.[22] For these reasons, iron ore production is concentrated in the hands of a few major players.

World production averages two billion metric tons of raw ore annually. The world’s largest producer of iron ore is the Brazilian mining corporation Vale, followed by Australian companies Rio Tinto Group and BHP. A further Australian supplier, Fortescue Metals Group Ltd, has helped bring Australia’s production to first in the world.

The seaborne trade in iron ore—that is, iron ore to be shipped to other countries—was 849 million tonnes in 2004.[22] Australia and Brazil dominate the seaborne trade, with 72% of the market.[22] BHP, Rio and Vale control 66% of this market between them.[22]

In Australia iron ore is won from three main sources: pisolite «channel iron deposit» ore derived by mechanical erosion of primary banded-iron formations and accumulated in alluvial channels such as at Pannawonica, Western Australia; and the dominant metasomatically-altered banded iron formation-related ores such as at Newman, the Chichester Range, the Hamersley Range and Koolyanobbing, Western Australia. Other types of ore are coming to the fore recently,[when?] such as oxidised ferruginous hardcaps, for instance laterite iron ore deposits near Lake Argyle in Western Australia.

The total recoverable reserves of iron ore in India are about 9,602 million tonnes of hematite and 3,408 million tonnes of magnetite.[23] Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Odisha, Goa, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu are the principal Indian producers of iron ore. World consumption of iron ore grows 10% per annum[citation needed] on average with the main consumers being China, Japan, Korea, the United States and the European Union.

China is currently the largest consumer of iron ore, which translates to be the world’s largest steel producing country. It is also the largest importer, buying 52% of the seaborne trade in iron ore in 2004.[22] China is followed by Japan and Korea, which consume a significant amount of raw iron ore and metallurgical coal. In 2006, China produced 588 million tons of iron ore, with an annual growth of 38%.

Iron ore market[edit]

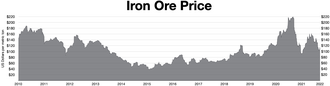

Iron ore prices (monthly)

China import/inbound iron ore spot price[24]

Global iron ore price[25]

Iron ore prices (daily)

25th October 2010 — 4th August 2022

Over the last 40 years, iron ore prices have been decided in closed-door negotiations between the small handful of miners and steelmakers which dominate both spot and contract markets. Traditionally, the first deal reached between these two groups sets a benchmark to be followed by the rest of the industry.[3]

In recent years, however, this benchmark system has begun to break down, with participants along both demand and supply chains calling for a shift to short term pricing. Given that most other commodities already have a mature market-based pricing system, it is natural for iron ore to follow suit. To answer increasing market demands for more transparent pricing, a number of financial exchanges and/or clearing houses around the world have offered iron ore swaps clearing. The CME group, SGX (Singapore Exchange), London Clearing House (LCH.Clearnet), NOS Group and ICEX (Indian Commodities Exchange) all offer cleared swaps based on The Steel Index’s (TSI) iron ore transaction data. The CME also offers a Platts-based swap, in addition to their TSI swap clearing. The ICE (Intercontinental Exchange) offers a Platts-based swap clearing service also. The swaps market has grown quickly, with liquidity clustering around TSI’s pricing.[26] By April 2011, over US$5.5 billion worth of iron ore swaps have been cleared basis TSI prices. By August 2012, in excess of one million tonnes of swaps trading per day was taking place regularly, basis TSI.

A relatively new development has also been the introduction of iron ore options, in addition to swaps. The CME group has been the venue most utilised for clearing of options written against TSI, with open interest at over 12,000 lots in August 2012.

Singapore Mercantile Exchange (SMX) has launched the world first global iron ore futures contract, based on the Metal Bulletin Iron Ore Index (MBIOI) which utilizes daily price data from a broad spectrum of industry participants and independent Chinese steel consultancy and data provider Shanghai Steelhome’s widespread contact base of steel producers and iron ore traders across China.[27] The futures contract has seen monthly volumes over 1.5 million tonnes after eight months of trading.[28]

This move follows a switch to index-based quarterly pricing by the world’s three largest iron ore miners—Vale, Rio Tinto and BHP—in early 2010, breaking a 40-year tradition of benchmark annual pricing.[29]

Abundance by country[edit]

Available world iron ore resources[edit]

Iron is the most abundant element on earth but not in the crust.[30] The extent of the accessible iron ore reserves is not known, though Lester Brown of the Worldwatch Institute suggested in 2006 that iron ore could run out within 64 years (that is, by 2070), based on 2% growth in demand per year.[31]

Australia[edit]

Geoscience Australia calculates that the country’s «economic demonstrated resources» of iron currently amount to 24 gigatonnes, or 24 billion tonnes.[citation needed] Another estimate places Australia’s reserves of iron ore at 52 billion tonnes, or 30 per cent of the world’s estimated 170 billion tonnes, of which Western Australia accounts for 28 billion tonnes.[32] The current production rate from the Pilbara region of Western Australia is approximately 430 million tonnes a year and rising. Gavin Mudd (RMIT University) and Jonathon Law (CSIRO) expect it to be gone within 30–50 years and 56 years, respectively.[33] These 2010 estimates require on-going review to take into account shifting demand for lower-grade iron ore and improving mining and recovery techniques (allowing deeper mining below the groundwater table).

United States[edit]

In 2014 mines in the United States produced 57.5 million metric tons of iron ore with an estimated value of $5.1 billion.[34] Iron mining in the United States is estimated to have accounted for 2% of the world’s iron ore output. In the United States there are twelve iron ore mines with nine being open pit mines and three being reclamation operations. There were also ten pelletizing plants, nine concentration plants, two direct-reduced iron (DRI) plants and one iron nugget plant that were operating in 2014.[34] In the United States the majority of iron ore mining is in the iron ranges around Lake Superior. These iron ranges occur in Minnesota and Michigan which combined accounted for 93% of the usable iron ore produced in the United States in 2014. Seven of the nine operational open pit mines in the United States are located in Minnesota as well as two of the three tailings reclamation operations. The other two active open pit mines were located in Michigan, in 2016 one of the two mines shut down.[34] There have also been iron ore mines in Utah and Alabama; however, the last iron ore mine in Utah shut down in 2014[34] and the last iron ore mine in Alabama shut down in 1975.[35]

Canada[edit]

In 2017 Canadian iron ore mines produced 49 million tons of iron ore in concentrate pellets and 13.6 million tons of crude steel. Of the 13.6 million tons of steel 7 million was exported, and 43.1 million tons of iron ore was exported at a value of $4.6 billion. Of the iron ore exported 38.5% of the volume was iron ore pellets with a value of $2.3 billion and 61.5% was iron ore concentrates with a value of $2.3 billion.[36] Forty-six per cent of Canada’s iron ore comes from the Iron Ore Company of Canada mine, in Labrador City, Newfoundland, with secondary sources including, the Mary River Mine, Nunavut.[36][37]

Brazil[edit]

Brazil is the second largest producer of iron ore with Australia being the largest. In 2015 Brazil exported 397 million tons of usable iron ore.[34] In December 2017 Brazil exported 346,497 metric tons of iron ore and from December 2007 to May 2018 they exported a monthly average of 139,299 metric tons.[38]

Ukraine[edit]

According to the US Geological Survey’s 2021 Report on iron ore,[39] Ukraine is estimated to have produced 62 million tons of iron ore in 2020 (2019: 63 million tons), placing it as the seventh largest global centre of iron ore production, behind Australia, Brazil, China, India, Russia and South Africa. Producers of iron ore in Ukraine include: Ferrexpo, Metinvest and ArcelorMittal Kryvyi Rih.

India[edit]

According to the US Geological Survey’s 2021 Report on iron ore,[39] India is estimated to produce 59 million tons of iron ore in 2020 (2019: 52 million tons), placing it as the seventh largest global centre of iron ore production, behind Australia, Brazil, China, Russia and South Africa and Ukraine.

Smelting[edit]

Iron ores consist of oxygen and iron atoms bonded together into molecules. To convert it to metallic iron it must be smelted or sent through a direct reduction process to remove the oxygen. Oxygen-iron bonds are strong, and to remove the iron from the oxygen, a stronger elemental bond must be presented to attach to the oxygen. Carbon is used because the strength of a carbon-oxygen bond is greater than that of the iron-oxygen bond, at high temperatures. Thus, the iron ore must be powdered and mixed with coke, to be burnt in the smelting process.

Carbon monoxide is the primary ingredient of chemically stripping oxygen from iron. Thus, the iron and carbon smelting must be kept at an oxygen-deficient (reducing) state to promote burning of carbon to produce CO not CO

2.

- Air blast and charcoal (coke): 2 C + O2 → 2 CO

- Carbon monoxide (CO) is the principal reduction agent.

- Stage One: 3 Fe2O3 + CO → 2 Fe3O4 + CO2

- Stage Two: Fe3O4 + CO → 3 FeO + CO2

- Stage Three: FeO + CO → Fe + CO2

- Limestone calcining: CaCO3 → CaO + CO2

- Lime acting as flux: CaO + SiO2 → CaSiO3

Trace elements[edit]

The inclusion of even small amounts of some elements can have profound effects on the behavioral characteristics of a batch of iron or the operation of a smelter. These effects can be both good and bad, some catastrophically bad. Some chemicals are deliberately added such as flux which makes a blast furnace more efficient. Others are added because they make the iron more fluid, harder, or give it some other desirable quality. The choice of ore, fuel, and flux determine how the slag behaves and the operational characteristics of the iron produced. Ideally iron ore contains only iron and oxygen. In reality this is rarely the case. Typically, iron ore contains a host of elements which are often unwanted in modern steel.

Silicon[edit]

Silica (SiO

2) is almost always present in iron ore. Most of it is slagged off during the smelting process. At temperatures above 1,300 °C (2,370 °F) some will be reduced and form an alloy with the iron. The hotter the furnace, the more silicon will be present in the iron. It is not uncommon to find up to 1.5% Si in European cast iron from the 16th to 18th centuries.

The major effect of silicon is to promote the formation of grey iron. Grey iron is less brittle and easier to finish than white iron. It is preferred for casting purposes for this reason.Turner (1900, pp. 192–197) reported that silicon also reduces shrinkage and the formation of blowholes, lowering the number of bad castings.

Phosphorus[edit]

Phosphorus (P) has four major effects on iron: increased hardness and strength, lower solidus temperature, increased fluidity, and cold shortness. Depending on the use intended for the iron, these effects are either good or bad. Bog ore often has a high phosphorus content.(Gordon 1996, p. 57)

The strength and hardness of iron increases with the concentration of phosphorus. 0.05% phosphorus in wrought iron makes it as hard as medium carbon steel. High phosphorus iron can also be hardened by cold hammering. The hardening effect is true for any concentration of phosphorus. The more phosphorus, the harder the iron becomes and the more it can be hardened by hammering. Modern steel makers can increase hardness by as much as 30%, without sacrificing shock resistance by maintaining phosphorus levels between 0.07 and 0.12%. It also increases the depth of hardening due to quenching, but at the same time also decreases the solubility of carbon in iron at high temperatures. This would decrease its usefulness in making blister steel (cementation), where the speed and amount of carbon absorption is the overriding consideration.

The addition of phosphorus has a down side. At concentrations higher than 0.2% iron becomes increasingly cold short, or brittle at low temperatures. Cold short is especially important for bar iron. Although bar iron is usually worked hot, its uses[example needed] often require it to be tough, bendable, and resistant to shock at room temperature. A nail that shattered when hit with a hammer or a carriage wheel that broke when it hit a rock would not sell well.[citation needed] High enough concentrations of phosphorus render any iron unusable.(Rostoker & Bronson 1990, p. 22) The effects of cold shortness are magnified by temperature. Thus, a piece of iron that is perfectly serviceable in summer, might become extremely brittle in winter. There is some evidence that during the Middle Ages the very wealthy may have had a high-phosphorus sword for summer and a low-phosphorus sword for winter.(Rostoker & Bronson 1990, p. 22)

Careful control of phosphorus can be of great benefit in casting operations. Phosphorus depresses the liquidus temperature, allowing the iron to remain molten for longer and increases fluidity. The addition of 1% can double the distance molten iron will flow.(Rostoker & Bronson 1990, p. 22). The maximum effect, about 500 °C, is achieved at a concentration of 10.2%(Rostocker & Bronson 1990, p. 194). For foundry work Turner(Turner 1900) felt the ideal iron had 0.2–0.55% phosphorus. The resulting iron filled molds with fewer voids and also shrank less. In the 19th century some producers of decorative cast iron used iron with up to 5% phosphorus. The extreme fluidity allowed them to make very complex and delicate castings. But, they could not be weight bearing, as they had no strength.(Turner 1900, pp. 202–204).

There are two remedies[according to whom?] for high phosphorus iron. The oldest, easiest and cheapest, is avoidance. If the iron that the ore produced was cold short, one would search for a new source of iron ore. The second method involves oxidizing the phosphorus during the fining process by adding iron oxide. This technique is usually associated with puddling in the 19th century, and may not have been understood earlier. For instance Isaac Zane, the owner of Marlboro Iron Works did not appear to know about it in 1772. Given Zane’s reputation[according to whom?] for keeping abreast of the latest developments, the technique was probably unknown to the ironmasters of Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Phosphorus is generally considered to be a deleterious contaminant because it makes steel brittle, even at concentrations of as little as 0.6%. When the Gilchrist–Thomas process allowed to remove bulk amounts of the element from cast iron in the 1870s, it was a major development because most of the iron ores mined in continental Europe at the time were phosphorous. However, removing all the contaminant by fluxing or smelting is complicated, and so desirable iron ores must generally be low in phosphorus to begin with.

Aluminium[edit]

Small amounts of aluminium (Al) are present in many ores including iron ore, sand and some limestones. The former can be removed by washing the ore prior to smelting. Until the introduction of brick lined furnaces, the amount of aluminium contamination was small enough that it did not have an effect on either the iron or slag. However, when brick began to be used for hearths and the interior of blast furnaces, the amount of aluminium contamination increased dramatically. This was due to the erosion of the furnace lining by the liquid slag.

Aluminium is difficult to reduce. As a result, aluminium contamination of the iron is not a problem. However, it does increase the viscosity of the slag.Kato & Minowa 1969, p. 37Rosenqvist 1983, p. 311 This will have a number of adverse effects on furnace operation. The thicker slag will slow the descent of the charge, prolonging the process. High aluminium will also make it more difficult to tap off the liquid slag. At the extreme this could lead to a frozen furnace.

There are a number of solutions to a high aluminium slag. The first is avoidance; do not use ore or a lime source with a high aluminium content. Increasing the ratio of lime flux will decrease the viscosity.(Rosenqvist 1983, p. 311)

Sulfur[edit]

Sulfur (S) is a frequent contaminant in coal. It is also present in small quantities in many ores, but can be removed by calcining. Sulfur dissolves readily in both liquid and solid iron at the temperatures present in iron smelting. The effects of even small amounts of sulfur are immediate and serious. They were one of the first worked out by iron makers. Sulfur causes iron to be red or hot short.(Gordon 1996, p. 7)

Hot short iron is brittle when hot. This was a serious problem as most iron used during the 17th and 18th centuries was bar or wrought iron. Wrought iron is shaped by repeated blows with a hammer while hot. A piece of hot short iron will crack if worked with a hammer. When a piece of hot iron or steel cracks the exposed surface immediately oxidizes. This layer of oxide prevents the mending of the crack by welding. Large cracks cause the iron or steel to break up. Smaller cracks can cause the object to fail during use. The degree of hot shortness is in direct proportion to the amount of sulfur present. Today iron with over 0.03% sulfur is avoided.

Hot short iron can be worked, but it has to be worked at low temperatures. Working at lower temperatures requires more physical effort from the smith or forgeman. The metal must be struck more often and harder to achieve the same result. A mildly sulfur contaminated bar can be worked, but it requires a great deal more time and effort.

In cast iron sulfur promotes the formation of white iron. As little as 0.5% can counteract the effects of slow cooling and a high silicon content.(Rostoker & Bronson 1990, p. 21) White cast iron is more brittle, but also harder. It is generally avoided, because it is difficult to work, except in China where high sulfur cast iron, some as high as 0.57%, made with coal and coke, was used to make bells and chimes.(Rostoker, Bronson & Dvorak 1984, p. 760) According to Turner (1900, pp. 200), good foundry iron should have less than 0.15% sulfur. In the rest of the world a high sulfur cast iron can be used for making castings, but will make poor wrought iron.

There are a number of remedies for sulfur contamination. The first, and the one most used in historic and prehistoric operations, is avoidance. Coal was not used in Europe (unlike China) as a fuel for smelting because it contains sulfur and therefore causes hot short iron. If an ore resulted in hot short metal, ironmasters looked for another ore. When mineral coal was first used in European blast furnaces in 1709 (or perhaps earlier), it was coked. Only with the introduction of hot blast from 1829 was raw coal used.

Ore roasting[edit]

Sulfur can be removed from ores by roasting and washing. Roasting oxidizes sulfur to form sulfur dioxide (SO2) which either escapes into the atmosphere or can be washed out. In warm climates it is possible to leave pyritic ore out in the rain. The combined action of rain, bacteria, and heat oxidize the sulfides to sulfuric acid and sulfates, which are water-soluble and leached out.(Turner 1900, pp. 77) However, historically (at least), iron sulfide (iron pyrite FeS

2), though a common iron mineral, has not been used as an ore for the production of iron metal. Natural weathering was also used in Sweden. The same process, at geological speed, results in the gossan limonite ores.

The importance attached to low sulfur iron is demonstrated by the consistently higher prices paid for the iron of Sweden, Russia, and Spain from the 16th to 18th centuries. Today sulfur is no longer a problem. The modern remedy is the addition of manganese. But, the operator must know how much sulfur is in the iron because at least five times as much manganese must be added to neutralize it. Some historic irons display manganese levels, but most are well below the level needed to neutralize sulfur.(Rostoker & Bronson 1990, p. 21)

Sulfide inclusion as manganese sulfide (MnS) can also be the cause of severe pitting corrosion problems in low-grade stainless steel such as AISI 304 steel.[40][41] Under oxidizing conditions and in the presence of moisture, when sulfide oxidizes it produces thiosulfate anions as intermediate species and because thiosulfate anion has a higher equivalent electromobility than chloride anion due to its double negative electrical charge, it promotes the pit growth.[42] Indeed, the positive electrical charges born by Fe2+ cations released in solution by Fe oxidation on the anodic zone inside the pit must be quickly compensated / neutralised by negative charges brought by the electrokinetic migration of anions in the capillary pit. Some of the electrochemical processes occurring in a capillary pit are the same than these encountered in capillary electrophoresis. Higher the anion electrokinetic migration rate, higher the rate of pitting corrosion. Electrokinetic transport of ions inside the pit can be the rate-limiting step in the pit growth rate.

See also[edit]

- Bog iron

- Iron ore in Africa

- Ironstone

Citations[edit]

- ^ Ramanaidou and Wells, 2014

- ^ «Iron Ore – Hematite, Magnetite & Taconite». Mineral Information Institute. Archived from the original on 17 April 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2006.

- ^ a b c Iron ore pricing emerges from stone age, Financial Times, October 26, 2009 Archived 2011-03-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Goldstein, J.I.; Scott, E.R.D.; Chabot, N.L. (2009). «Iron meteorites: Crystallization, thermal history, parent bodies, and origin». Geochemistry. 69 (4): 293–325. Bibcode:2009ChEG…69..293G. doi:10.1016/j.chemer.2009.01.002.

- ^ Frey, Perry A.; Reed, George H. (2012-09-21). «The Ubiquity of Iron». ACS Chemical Biology. 7 (9): 1477–1481. doi:10.1021/cb300323q. ISSN 1554-8929. PMID 22845493.

- ^ Harry Klemic, Harold L. James, and G. Donald Eberlein, (1973) «Iron,» in United States Mineral Resources, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 820, p.298-299.

- ^ Troll, Valentin R.; Weis, Franz A.; Jonsson, Erik; Andersson, Ulf B.; Majidi, Seyed Afshin; Högdahl, Karin; Harris, Chris; Millet, Marc-Alban; Chinnasamy, Sakthi Saravanan; Kooijman, Ellen; Nilsson, Katarina P. (2019-04-12). «Global Fe–O isotope correlation reveals magmatic origin of Kiruna-type apatite-iron-oxide ores». Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1712. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1712T. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09244-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6461606. PMID 30979878.

- ^ Muwanguzi, Abraham J. B.; Karasev, Andrey V.; Byaruhanga, Joseph K.; Jönsson, Pär G. (2012-12-03). «Characterization of Chemical Composition and Microstructure of Natural Iron Ore from Muko Deposits». ISRN Materials Science. 2012: e174803. doi:10.5402/2012/174803. S2CID 56961299.

- ^ Jonsson, Erik; Troll, Valentin R.; Högdahl, Karin; Harris, Chris; Weis, Franz; Nilsson, Katarina P.; Skelton, Alasdair (2013-04-10). «Magmatic origin of giant ‘Kiruna-type’ apatite-iron-oxide ores in Central Sweden». Scientific Reports. 3 (1): 1644. Bibcode:2013NatSR…3E1644J. doi:10.1038/srep01644. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3622134. PMID 23571605.

- ^ Guijón, R.; Henríquez, F.; Naranjo, J.A. (2011). «Geological, Geographical and Legal Considerations for the Conservation of Unique Iron Oxide and Sulphur Flows at El Laco and Lastarria Volcanic Complexes, Central Andes, Northern Chile». Geoheritage. 3 (4): 99–315. doi:10.1007/s12371-011-0045-x. S2CID 129179725.

- ^ a b c d e Li, Chao; Sun, Henghu; Bai, Jing; Li, Longtu (2010-02-15). «Innovative methodology for comprehensive utilization of iron ore tailings: Part 1. The recovery of iron from iron ore tailings using magnetic separation after magnetizing roasting». Journal of Hazardous Materials. 174 (1–3): 71–77. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.09.018. PMID 19782467.

- ^ Sirkeci, A. A.; Gül, A.; Bulut, G.; Arslan, F.; Onal, G.; Yuce, A. E. (April 2006). «Recovery of Co, Ni, and Cu from the tailings of Divrigi Iron Ore Concentrator». Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review. 27 (2): 131–141. Bibcode:2006MPEMR..27..131S. doi:10.1080/08827500600563343. ISSN 0882-7508. S2CID 93632258.

- ^ Das, S.K.; Kumar, Sanjay; Ramachandrarao, P. (December 2000). «Exploitation of iron ore tailing for the development of ceramic tiles». Waste Management. 20 (8): 725–729. doi:10.1016/S0956-053X(00)00034-9.

- ^ Gzogyan, T. N.; Gubin, S. L.; Gzogyan, S. R.; Mel’nikova, N. D. (2005-11-01). «Iron losses in processing tailings». Journal of Mining Science. 41 (6): 583–587. doi:10.1007/s10913-006-0022-y. ISSN 1573-8736. S2CID 129896853.

- ^ Uwadiale, G. G. O. O.; Whewell, R. J. (1988-10-01). «Effect of temperature on magnetizing reduction of agbaja iron ore». Metallurgical Transactions B. 19 (5): 731–735. Bibcode:1988MTB….19..731U. doi:10.1007/BF02650192. ISSN 1543-1916. S2CID 135733613.

- ^ Stephens, F. M.; Langston, Benny; Richardson, A. C. (1953-06-01). «The Reduction-Oxidation Process For the Treatment of Taconites». JOM. 5 (6): 780–785. Bibcode:1953JOM…..5f.780S. doi:10.1007/BF03397539. ISSN 1543-1851.

- ^ H.T. Shen, B. Zhou, et al. «Roasting-magnetic separation and direct reduction of a refractory oolitic-hematite ore» Min. Met. Eng., 28 (2008), pp. 30-43