— 1 —

Сериал Hulu — десятая адаптация романа канадской писательницы Маргарет Этвуд, опубликованного в 1985 году. Первый спектакль показали на сцене частного исследовательского университета Тафтса в 1989-м. В 2000 году Пол Рудерс представил в Копенгагене оперу, а в 2002 году Брендон Бернс поставил свой спектакль в лондонском Королевском театре Хеймаркет. Адаптацией произведения для балета занималась Лиа Йорк, премьера состоялась в 2013 году. Роман Этвуд подошел и для моно-спектакля, который придумал и представил в США Джозеф Столленверк в 2015 году.

В 1990 году немецкий кинорежиссер Фолькер Шлендорф экранизировал «Служанку» с Наташей Ричардсон, Фэй Данауэй и Робертом Дювалем. Кроме того, по книге сделаны аудиокнига, музыкальный альбом и два радиоспектакля. Первый — режиссера Джона Драйдена для BBC Radio 4 — слушателям представили в 2000 году. Вторым занималось канадское радио CBC в 2002 году под руководством сценариста и драматурга Майкла О’Брайена.

— 2 —

У романа есть продолжение и оно выйдет осенью 2019 года. Маргарет Этвуд не планировала развивать историю: действие первой книги завершается более чем идеально. Однако в 2018 году стало известно, что Этвуд активно работает над сиквелом, который будет называться The Testaments («Свидетельства»). Читатель вернется в Гилеад спустя 15 лет после событий первой части, а повествование будет вестись от лица трех женщин.

Маргарет Этвуд

© Emma McIntyre/Getty Images for Hammer Museum

Несмотря на то, что действие романа «Рассказ служанки» разворачивается в недалеком будущем в Новой Англии, Этвуд неоднократно приходилось уточнять, что ее произведение не имеет отношения к научной фантастике. Напротив, при создании романа автор старалась привнести в сюжет события, которые происходили в различных обществах в разные времена.

— 3 —

Автор романа получила камео в сериале. В потоке ужасающих сюжетных событий и на фоне яркого актерского выхода Энн Дауд сложно было заметить еще одну строгую надзирательницу над служанками, с седыми волосами и острым взглядом. Это и была Маргарет Этвуд. В пилотном эпизоде ей пришлось наказать непокорную Фредову (Джун) пощечиной. Писательница сама хотела сыграть «тетку», а вот пощечина была идеей создателя сериала — Брюса Миллера.

— 4 —

Движение #MeToo подтолкнуло развитие сюжета, который порвал с книжным первоисточником после финала 1-го сезона. Удел женщин, оказавшихся в плену республики Гилеад, — страдания. Брюс Миллер проводит своих героинь через настоящие пытки — физические и, что страшнее, психологические.

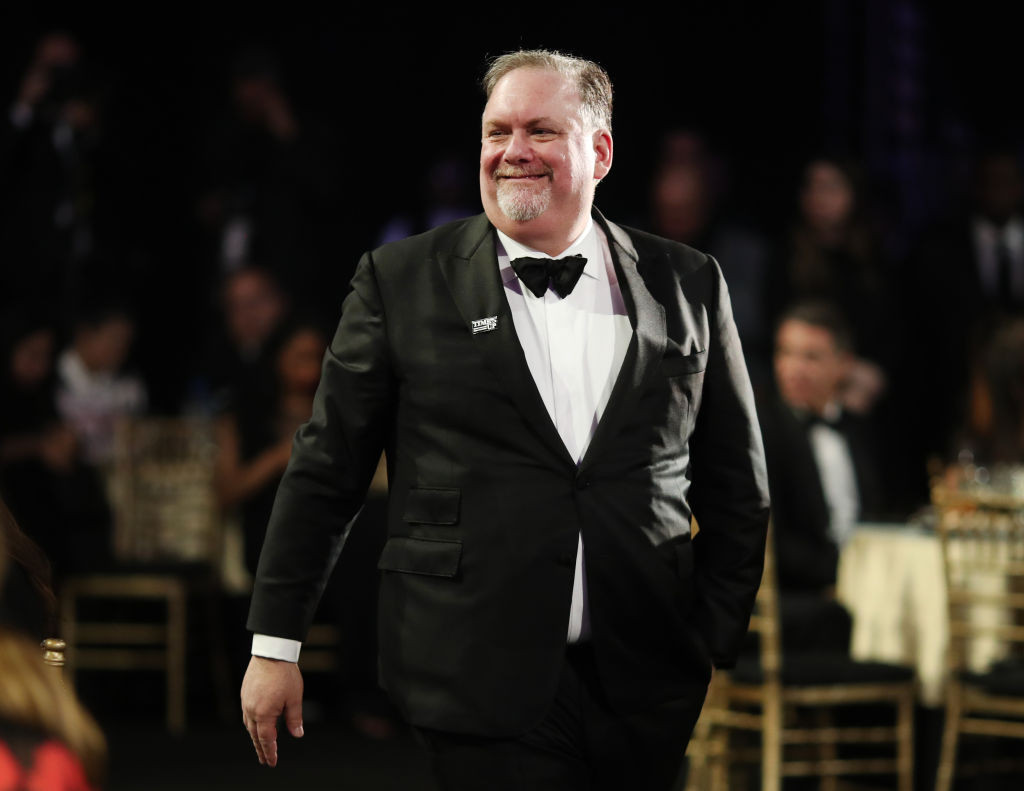

Брюс Миллер

© Christopher Polk/Getty Images for The Critics’ Choice Awards

По словам сценариста, судьба главного персонажа Джун Осборн не получилась бы убедительной, если бы не современные женщины, объединившиеся в движение #MeToo. Вдохновение здесь работает в обе стороны: реальные события вдохновляют и подпитывают Джун в мире сериала. В то же время образ его главной героини давно стал примером мужества для всех поклонниц «Служанки».

— 5 —

«Рассказ служанки» никогда не транслировался на телеканалах. Это целиком продукт стримингового сервиса Hulu, и посмотреть сериал поклонники могут только онлайн. Однако это не помешало организаторам премии «Эмми» отметить достоинства шоу. «Служанка» стала первым стриминговым сериалом, получившим в 2017 году премии в четырех категориях, в том числе как лучшее драматическое произведение. Это уникальный случай, учитывая, что Netflix годами боролся за награды для своих сериалов, а Hulu с его антиутопическим кошмаром моментально удалось получить исключительные привилегии.

— 6 —

Один из центральных персонажей — начальник службы охраны командора Ник — в книге фигурировал без фамилии. Авторы сериала решили это исправить и назвали его Блейн. Внимательный зритель, заметив эту фамилию, вспомнит о Рике Блейне — протагонисте ленты «Касабланка». Герой Хамфри Богарта помогал «пленникам» Касабланки покинуть город, то же самое пытается провернуть и герой Макса Мингеллы в Гилеаде.

— 7 —

Белоснежные «крылышки» — отличительный элемент гардероба служанок наряду с красными плащами и платьями в пол — крайне неудобный головной убор. Актрисы признавались, что он радикально ограничивает угол зрения и практически ослепляет: если хочешь что-то увидеть, смотреть приходится только прямо перед собой.

Художник по костюмам Эн Крэбтри рассказала, что «крылышки» помогают отразить «психологическое, физическое и эмоциональное заключение служанок» Гилеада. Элизабет Мосс, исполняющая роль Джун, провела много времени вместе с партнерами по площадке, разучивая ритм шагов служанок, чтобы в кадре спокойно передвигаться группами и не сталкиваться друг с другом.

— 8 —

Актриса Аманда Бругел, исполняющая роль марфы Риты в доме командора Фреда Уотерфорда, в юности была поклонницей романа Маргарет Этвуд. Бругел прочла книгу в старших классах и испытала нечто вроде шока, оправившись от которого написала итоговую научную работу на основе «Рассказа служанки». Труд о героине романа Рите обеспечил Бругел стипендию на получение высшего образования.

— 9 —

Продюсерам пришлось пренебречь одной из важных деталей романа из-за дайверсити-тренда — требований расового и этнического разнообразия в кино. В книге среди жестокостей правительства Гилеада было изгнание всех представителей «не белой» расы, поэтому население республики было однородным. Однако Брюс Миллер так и не смог представить, как показать подобное положение дел, учитывая современные общественные тенденции.

«Будет ли разница между телешоу о расизме и «расистским сериалом», если в обоих случаях роли не достанутся «цветным» актерам?» — так спрашивал себя продюсер. В итоге зверства сериального Гилеада обошли стороной национальный вопрос и сосредоточились на религиозных и политических аспектах.

— 10 —

Поклонники воспринимают сюжетные повороты в сериале и героев слишком лично. Отчасти это происходит потому, что зрителю не составляет труда отыскать общее между вымыслом — Гилеадом — и реальностью, Америкой эпохи Трампа. Выход нового сезона снова резонирует с общественно-политическими событиями в США. Сопротивление в сериале развернется на фоне борьбы американок за право на аборты и историй о том, как разлучают детей и родителей на границе с Мексикой.

Рассказывая о 3-м сезоне, исполнительница главной роли Элизабет Мосс попыталась объяснить поступок своей героини в конце 2-го. Решения Джун раздражают многих поклонников. Весь год, пока велись съемки нового сезона, фанаты «Служанки» пытались простить Джун ее демарш с побегом в Канаду — у нее был шанс завершить свои испытания, но она сознательно его упустила, и теперь будет готовить революцию в Гилеаде. «Она должна быть не только сильнее и умнее своих противников, но и жестче, — объясняла Мосс, призывая поклонников разделить с Джун долгое и мучительное путешествие. — Она немного сходит с ума, но в этом безумии способна делать то, что другие не могут. Она способна совершать поступки ради общего блага».

Cover of the first edition |

|

| Author | Margaret Atwood |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Tad Aronowicz,[1] design; Gail Geltner, collage (first edition, hardback) |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian novel Speculative fiction Tragedy[2][3][4][5] |

| Publisher | McClelland and Stewart Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (ebook) |

|

Publication date |

1985 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 311 |

| ISBN | 0-7710-0813-9 |

| Followed by | The Testaments |

The Handmaid’s Tale is a futuristic dystopian novel[6] by Canadian author Margaret Atwood and published in 1985. It is set in a near-future New England in a patriarchal, totalitarian theonomic state known as the Republic of Gilead, which has overthrown the United States government.[7] Offred is the central character and narrator and one of the «handmaids», women who are forcibly assigned to produce children for the «commanders», who are the ruling class in Gilead.

The novel explores themes of subjugated women in a patriarchal society, loss of female agency and individuality, suppression of women’s reproductive rights, and the various means by which women resist and try to gain individuality and independence. The title echoes the component parts of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, which is a series of connected stories (such as «The Merchant’s Tale» and «The Parson’s Tale»).[8] It also alludes to the tradition of fairy tales where the central character tells her story.[9]

The Handmaid’s Tale won the 1985 Governor General’s Award and the first Arthur C. Clarke Award in 1987; it was also nominated for the 1986 Nebula Award, the 1986 Booker Prize, and the 1987 Prometheus Award. In 2022, The Handmaid’s Tale was included on the «Big Jubilee Read» list of 70 books by Commonwealth authors, selected to celebrate the Platinum Jubilee of Elizabeth II.[10] The book has been adapted into a 1990 film, a 2000 opera, a 2017 television series, and other media. An ebook version was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.[11][12] A sequel novel, The Testaments, was published in 2019.

Plot summary[edit]

After a staged attack that killed the President of the United States and most of Congress, a radical political group called the «Sons of Jacob» uses theonomic ideology to launch a revolution.[7] The United States Constitution is suspended, newspapers are censored, and what was formerly the United States of America is changed into a military dictatorship known as the Republic of Gilead. The new regime moves quickly to consolidate its power, overtaking all other religious groups, including Christian denominations.

The regime reorganizes society using a peculiar interpretation of some Old Testament ideas, and a new militarized, hierarchical model of social and religious fanaticism among its newly created social classes. One of the most significant changes is the limitation of people’s rights. Women become the lowest-ranking class and are not allowed to own money or property, or to read and write. Most significantly, women are deprived of control over their own reproductive functions.

The story is told in first-person narration by a woman named Offred. In this era of environmental pollution and radiation, she is one of the few remaining fertile women. Therefore, she is forcibly assigned to produce children for the «Commanders,» the ruling class of men, and is known as a «Handmaid» based on the biblical story of Rachel and her handmaid Bilhah. She undergoes training to become a handmaid along with other women of her standing at the Rachel and Leah Centre.

Apart from Handmaids, women are classed socially and follow a strict dress code, ranked highest to lowest: the Commanders’ Wives in teal blue, the Handmaids in burgundy with large white bonnets to be easily seen, the Aunts (who train and indoctrinate the Handmaids) in brown, the Marthas (cooks and maids, possibly sterile women past child-bearing years) in green, Econowives (the wives of lower-ranking men who handle everything in the domestic sphere) in blue, red and green stripes, very young girls in pink (often married or «given» to a Commander at 14 to produce offspring), young boys in blue, and widows in black.

Offred details her life starting with her third assignment as a Handmaid to a Commander. Interspersed with her narratives of her present-day experiences are flashbacks of her life before and during the beginning of the revolution, including her failed attempt to escape to Canada with her husband and child, her indoctrination into life as a Handmaid by the Aunts, and the escape of her friend Moira from the indoctrination facility. At her new home, she is treated poorly by the Commander’s wife, Serena Joy, a former Christian media personality who supported women’s domesticity and subordinate role well before Gilead was established.

To Offred’s surprise, the Commander requests to see her outside of the «Ceremony» which is a reproductive ritual obligatory for handmaids (conducted in the presence of the wives) and intended to result in conception. The commander’s request to see Offred in the library is an illegal activity in Gilead, but they meet nevertheless. They mostly play Scrabble and Offred is allowed to ask favours of him, either in terms of information or material items. The Commander asks Offred to kiss him «as if she meant it» and tells her about his strained relationship with his wife. Finally, he gives her lingerie and takes her to a covert, government-run brothel called Jezebel’s. Offred unexpectedly encounters Moira there, with Moira’s will broken, and learns from Moira that those who are found breaking the law are sent to the Colonies to clean up toxic waste or are allowed to work at Jezebel’s as punishment.

In the days between her visits to the Commander, Offred also learns from her shopping partner, a woman called Ofglen, of the Mayday resistance, an underground network working to overthrow the Republic of Gilead. Not knowing of Offred’s criminal acts with her husband, Serena begins to suspect that the Commander is infertile, and arranges for Offred to begin a covert sexual relationship with Nick, the Commander’s personal servant. Serena offers Offred information about her daughter in exchange. She later brings her a photograph of Offred’s daughter which leaves Offred feeling dejected because she senses she has been erased from her daughter’s life.

Nick had earlier tried to talk to Offred and had shown interest in her. After their initial sexual encounter, Offred and Nick begin to meet on their own initiative as well, with Offred discovering that she enjoys these intimate moments despite memories of her husband, and shares potentially dangerous information about her past with him. Offred tells Nick that she thinks she is pregnant.

Offred hears from a new walking partner that Ofglen has disappeared (reported as a suicide). Serena finds evidence of the relationship between Offred and the Commander, which causes Offred to contemplate suicide. Shortly afterward, men arrive at the house wearing the uniform of the secret police, the Eyes of God, known informally as «the Eyes», to take her away. As she is led to a waiting van, Nick tells her to trust him and go with the men. It is unclear whether the men are actually Eyes or members of the Mayday resistance.

Offred is still unsure if Nick is a member of Mayday or an Eye posing as one, and does not know if leaving will result in her escape or her capture. Ultimately, she enters the van with her future uncertain while Commander Fred and Serena are left bereft in the house, each thinking of repercussions of Offred’s capture on their lives.

The novel concludes with a metafictional epilogue, described as a partial transcript of an international historical association conference taking place in the year 2195. The keynote speaker explains that Offred’s account of the events of the novel was recorded onto cassette tapes later found and transcribed by historians studying what is then called «the Gilead Period».

Background[edit]

Fitting with her statements that The Handmaid’s Tale is a work of speculative fiction, not science fiction, Atwood’s novel offers a satirical view of various social, political, and religious trends of the United States in the 1980s. Her motivation for writing the novel was her belief that in the 1980s, the religious right was discussing what they would do with/to women if they took power, including the Moral Majority, Focus on the Family, the Christian Coalition and the Ronald Reagan administration.[13] Atwood questions what would happen if these trends, and especially «casually held attitudes about women» were taken to their logical end.[14]

Atwood argues that all of the scenarios offered in The Handmaid’s Tale have actually occurred in real life—in an interview she gave regarding her later novel Oryx and Crake, Atwood maintains that «As with The Handmaid’s Tale, I didn’t put in anything that we haven’t already done, we’re not already doing, we’re seriously trying to do, coupled with trends that are already in progress… So all of those things are real, and therefore the amount of pure invention is close to nil.»[15] Atwood was known to carry around newspaper clippings to her various interviews to support her fiction’s basis in reality.[16] Atwood has explained that The Handmaid’s Tale is a response to those who say the oppressive, totalitarian, and religious governments that have taken hold in other countries throughout the years «can’t happen here»—but in this work, she has tried to show how such a takeover might play out.[17]

Atwood was also inspired by the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1978–79 that saw a theocracy established that drastically reduced the rights of women and imposed a strict dress code on Iranian women, very much like that of Gilead.[18] In The Handmaid’s Tale, a reference is made to the Islamic Republic of Iran in the form of the history book Iran and Gilead: Two Late Twentieth Century Monotheocracies mentioned in the endnotes describing the historians’ convention in 2195.[18] Atwood’s picture of a society ruled by men who professed high moral principles, but are in fact self-interested and selfish was inspired by observing Canadian politicians in action, especially in her hometown of Toronto, who frequently profess in a very sanctimonious manner to be acting from the highest principles of morality while in reality the opposite is the case.[18]

During the Second World War, Canadian women took on jobs in the place of men serving in the military that they were expected to yield to men once the war was over. After 1945, not all women wanted to return to their traditional roles as housewives and mothers, leading to a male backlash.[19] Atwood was born in 1939, and while growing up in the 1950s she saw first-hand the complaints against women who continued to work after 1945 and of women who unhappily gave up their jobs, which she incorporated into her novel.[19] The way in which the narrator is forced into becoming an unhappy housewife after she loses her job, in common with all the other women of Gilead, was inspired by Atwood’s memories of the 1950s.[19]

Atwood’s inspiration for the Republic of Gilead came from her study of early American Puritans while at Harvard, which she attended on a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship.[14] Atwood argues that the modern view of the Puritans—that they came to America to flee religious persecution in England and set up a religiously tolerant society—is misleading, and that instead, these Puritan leaders wanted to establish a monolithic theonomy where religious dissent would not be tolerated.[14][20]

Atwood has a personal connection to the Puritans, and she dedicates the novel to her own ancestor Mary Webster, who was accused of witchcraft in Puritan New England but survived her hanging.[21] Due to the totalitarian nature of Gileadean society, Atwood, in creating the setting, drew from the «utopian idealism» present in 20th-century régimes, such as Cambodia and Romania, as well as earlier New England Puritanism.[22] Atwood has argued that a coup, such as the one depicted in The Handmaid’s Tale, would misuse religion in order to achieve its own ends.[22][23]

Atwood, in regards to those leading Gilead, further stated:[24]

I don’t consider these people to be Christians because they do not have at the core of their behaviour and ideologies what I, in my feeble Canadian way, would consider to be the core of Christianity … and that would be not only love your neighbours but love your enemies. That would also be «I was sick and you visited me not» and such and such …And that would include also concern for the environment, because you can’t love your neighbour or even your enemy, unless you love your neighbour’s oxygen, food, and water. You can’t love your neighbour or your enemy if you’re presuming policies that are going to cause those people to die. … Of course faith can be a force for good and often has been. So faith is a force for good particularly when people are feeling beleaguered and in need of hope. So you can have bad iterations and you can also have the iteration in which people have got too much power and then start abusing it. But that is human behaviour, so you can’t lay it down to religion. You can find the same in any power situation, such as politics or ideologies that purport to be atheist. Need I mention the former Soviet Union? So it is not a question of religion making people behave badly. It is a question of human beings getting power and then wanting more of it.

In the same vein, Atwood also declared that «In the real world today, some religious groups are leading movements for the protection of vulnerable groups, including women.»[8] Atwood draws connections between the ways in which Gilead’s leaders maintain their power and other examples of actual totalitarian governments. In her interviews, Atwood offers up Afghanistan as an example of a religious theocracy forcing women out of the public sphere and into their homes,[25] as in Gilead.[16][14]

The «state-sanctioned murder of dissidents» was inspired by the Philippines under President Ferdinand Marcos, and the last General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party Nicolae Ceaușescu’s obsession with increasing the birth rate (Decree 770) led to the strict policing of pregnant women and the outlawing of birth control and abortion.[16] However, Atwood clearly explains that many of these actions were not just present in other cultures and countries, «but within Western society, and within the ‘Christian’ tradition itself».[22]

The Republic of Gilead struggles with infertility, making Offred’s services as a Handmaid vital to producing children and thus reproducing the society. Handmaids themselves are «untouchable», but their ability to signify status is equated to that of slaves or servants throughout history.[22] Atwood connects their concerns with infertility to real-life problems our world faces, such as radiation, chemical pollution, and sexually transmitted disease (HIV/AIDS is specifically mentioned in the «Historical Notes» section at the end of the novel, which was a relatively new disease at the time of Atwood’s writing whose long-term impact was still unknown). Atwood’s strong stance on environmental issues and their negative consequences for our society has presented itself in other works such as her MaddAddam trilogy, and refers back to her growing up with biologists and her own scientific curiosity.[26]

Characters[edit]

Offred[edit]

Offred is the protagonist and narrator who takes the readers through life in Gilead. She was labeled a «wanton woman» when Gilead was established because she had married a man who was divorced. All divorces were nullified by the new government, meaning her husband was now considered still married to his first wife, making Offred an adulteress. In trying to escape Gilead, she was separated from her husband and daughter.[27]

She is part of the first generation of Gilead’s women, those who remember pre-Gilead times. Proved fertile, she is considered an important commodity and has been placed as a «handmaid» in the home of «the Commander» and his wife Serena Joy, to bear a child for them (Serena Joy is believed to be infertile).[27] Readers are able to see Offred’s resistance to the Republic of Gilead on the inside through her thoughts.

Offred is a slave name that describes her function: she is «of Fred» (i.e., she belongs to Fred – presumed to be the name of the Commander – and is considered a concubine). In the novel, Offred says that she is not a concubine, but a tool; a «two-legged womb». The Handmaids’ names say nothing about who the women really are; their only identity is as the Commander’s property. «Offred» is also a pun on the word «offered», as in «offered as a sacrifice», and «of red» because the red dress assigned for the handmaids in Gilead.[8]

In Atwood’s original novel, Offred’s real name is never revealed. In Volker Schlöndorff’s 1990 film adaptation Offred was given the real name Kate,[28] while the television series gave her the real name June.

The women in training to be Handmaids whisper names across their beds at night. The names are «Alma. Janine. Dolores. Moira. June,» and all are later accounted for except June. In addition, one of the Aunts tells the handmaids-in-training to stop «mooning and June-ing».[29] From this and other references, some readers have inferred that her birth name could be «June».[30] Miner suggests that «June» is a pseudonym. As «Mayday» is the name of the Gilead resistance, June could be an invention by the protagonist. The Nunavit conference covered in the epilogue takes place in June.[31]

When the Hulu TV series chose to state outright that Offred’s real name is June, Atwood wrote that it was not her original intention to imply that Offred’s real name is June «but it fits, so readers are welcome to it if they wish».[8] The revelation of Offred’s real name serves only to humanize her in the presence of the other Handmaids.

The Commander[edit]

The Commander says that he was a scientist and was previously involved in something similar to market research before Gilead’s inception. Later, it is hypothesized, but not confirmed, that he might have been one of the architects of the Republic and its laws. Presumably, his first name is «Fred», though that, too, may be a pseudonym. He engages in forbidden intellectual pursuits with Offred, such as playing Scrabble, and introduces her to a secret club that serves as a brothel for high-ranking officers.

He shows his softer side to Offred during their covert meetings and confesses of being «misunderstood» by his wife. Offred learns that the Commander carried on a similar relationship with his previous handmaid, who later killed herself when his wife found out.

In the epilogue, Professor Pieixoto speculates that one of two figures, both instrumental in the establishment of Gilead, may have been the Commander, based on the name «Fred». It is his belief that the Commander was a man named Frederick R. Waterford who was killed in a purge shortly after Offred was taken away, charged with harbouring an enemy agent.

Serena Joy[edit]

Serena Joy is a former televangelist and the Commander’s wife in the fundamentalist theonomy. Her real name is Pam and she is fond of gardening and knitting. The state took away her power and public recognition, and she tries to hide her past as a television figure. Offred identifies Serena Joy by recalling seeing her on TV when she was a little girl early on Saturday mornings while waiting for the cartoons to air.

Believed to be sterile (although the suggestion is made that the Commander is sterile, Gileadean laws attribute sterility only to women), she is forced to accept that he has use of a Handmaid. She resents having to take part in «The Ceremony», a monthly fertility ritual. She strikes a deal with Offred to arrange for her to have sex with Nick in order to become pregnant. According to Professor Pieixoto in the epilogue, «Serena Joy» or «Pam» are pseudonyms. The character’s real name is implied to be Thelma.

Ofglen[edit]

Ofglen is a neighbour of Offred’s and a fellow Handmaid. She is partnered with Offred to do the daily shopping. Handmaids are never alone and are expected to police each other’s behaviour. Ofglen is a secret member of the Mayday resistance. In contrast to Offred, she is daring. She knocks out a Mayday spy who is to be tortured and killed in order to save him the pain of a violent death. Offred is told that when Ofglen vanishes, it is because she has committed suicide before the government can take her into custody due to her membership in the resistance, possibly to avoid giving away any information.

A new Handmaid, also called Ofglen, takes Ofglen’s place, and is assigned as Offred’s shopping partner. She threatens Offred against any thought of resistance. In addition, she breaks protocol by telling her what happened to the first Ofglen.

Nick[edit]

Nick is the Commander’s chauffeur, who lives above the garage. Right from the start, Nick comes across as a daring character as he smokes and tries to engage with Offred, both forbidden activities. By Serena Joy’s arrangement, he and Offred start a sexual relationship to increase her chance of getting pregnant. If she were unable to bear the Commander a child, she would be declared sterile and shipped to the ecological wastelands of the Colonies. Offred begins to develop feelings for him. Nick is an ambiguous character, and Offred does not know if he is a party loyalist or part of the resistance, though he identifies himself as the latter. The epilogue suggests that he really was part of the resistance, and aided Offred in escaping the Commander’s house.

Moira[edit]

Moira has been a close friend of Offred’s since college. In the novel, their relationship represents a female friendship that the Republic of Gilead tries to block. A lesbian, she has resisted the homophobia of Gileadean society. Moira is taken to be a Handmaid soon after Offred. She finds the life of a handmaid unbearably oppressive and risks engaging with the guards just to defy the system. She escapes by stealing an Aunt’s pass and clothes, but Offred later finds her working as a prostitute in a party-run brothel. She was caught and chose the brothel rather than to be sent to the Colonies. Moira exemplifies defiance against Gilead by rejecting every value that is forced onto the citizens.

Luke[edit]

Luke was Offred’s husband before the formation of Gilead. He was married when he first started a relationship with Offred and had divorced his first wife to marry her. Under Gilead, all divorces were retroactively nullified, resulting in Offred being considered an adulteress and their daughter illegitimate. Offred was forced to become a Handmaid and her daughter was given to a loyalist family. Since their attempt to escape to Canada, Offred has heard nothing of Luke. She wavers between believing him dead or imprisoned.

Professor Pieixoto[edit]

Pieixoto is the «co-discoverer [with Professor Knotly Wade] of Offred’s tapes». In his presentation at an academic conference set in 2195, he talks about «the ‘Problems of Authentication in Reference to The Handmaid’s Tale‘«.[27]

Pieixoto is the person who is retelling Offred’s story, and so makes the narration even more unreliable than it was originally.

Aunt Lydia[edit]

Aunt Lydia appears in flashbacks where her instructions frequently haunt Offred. Aunt Lydia works at the ‘Red Center’ where women receive instructions for a life as a Handmaid. Throughout the narrative, Aunt Lydia’s pithy pronouncements on code of conduct for the Handmaids shed light on the philosophy of subjugation of women practiced in Gilead. Aunt Lydia appears to be a true believer of Gilead’s religious philosophy and seems to take her job as a true calling.

Cora[edit]

A servant who works at the Commander’s house because she is infertile. She hopes that Offred will get pregnant as she desires to help raise a child. She is friendly towards Offred and even covers up for her when she finds her lying on the floor one morning; a suspicious occurrence by Gilead’s standards worthy of being reported.

Rita[edit]

Rita is a Martha at Commander Fred’s house. Her job is cooking and housekeeping and is one of the members of the «household». At the start of the novel, Rita has a contempt for Offred and though she is responsible for keeping Offred well fed, she believes a handmaid should prefer going to the colonies over working as a sexual slave.

Setting[edit]

The novel is set in an indeterminate dystopian future, speculated to be around the year 2005,[32] with a fundamentalist theonomy ruling the territory of what had been the United States but is now the Republic of Gilead. The fertility rates in Gilead have diminished due to environmental toxicity and fertile women are a valuable commodity owned and enslaved by the powerful elite. Individuals are segregated by categories and dressed according to their social functions. Complex dress codes play a key role in imposing social control within the new society and serve to distinguish people by sex, occupation, and caste.

The action takes place in what once was the Harvard Square neighbourhood of Cambridge, Massachusetts;[33][34] Atwood studied at Radcliffe College, located in this area. As a researcher, Atwood spent a lot of time in the Widener Library at Harvard which in the novel serves as a setting for the headquarters of the Gilead Secret Service.[9]

Gilead society[edit]

Religion[edit]

Bruce Miller, the executive producer of The Handmaid’s Tale television serial, declared with regard to Atwood’s book, as well as his series, that Gilead is «a society that’s based kind of in a perverse misreading of Old Testament laws and codes».[35] The author explains that Gilead tries to embody the «utopian idealism» present in 20th-century regimes, as well as earlier New England Puritanism.[22] Both Atwood and Miller stated that the people running Gilead are «not genuinely Christian».[36][35]

The group running Gilead, according to Atwood, is «not really interested in religion; they’re interested in power.»[24] In her prayers to God, Offred reflects on Gilead and prays «I don’t believe for an instant that what’s going on out there is what You meant…. I suppose I should say I forgive whoever did this, and whatever they’re doing now. I’ll try, but it isn’t easy.»[37] Margaret Atwood, writing on this, says that «Offred herself has a private version of the Lord’s Prayer and refuses to believe that this regime has been mandated by a just and merciful God.»[8]

Christian churches that do not support the actions of the Sons of Jacob are systematically demolished, and the people living in Gilead are never seen attending church.[35] Christian denominations, including Quakers, Baptists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Roman Catholics, are specifically named as enemies of the Sons of Jacob.[24][35] Nuns who refuse conversion are considered «Unwomen» and banished to the Colonies, owing to their reluctance to marry and refusal (or inability) to bear children. Priests unwilling to convert are executed and hanged from the Wall. Atwood pits Quaker Christians against the regime by having them help the oppressed, something she feels they would do in reality: «The Quakers have gone underground, and are running an escape route to Canada, as—I suspect—they would.»[8]

Jews are named an exception and classified Sons of Jacob. Offred observes that Jews refusing to convert are allowed to emigrate from Gilead to Israel, and most choose to leave. However, in the epilogue, Professor Pieixoto reveals that many of the emigrating Jews ended up being dumped into the sea while on the ships ostensibly tasked with transporting them to Israel, due to privatization of the «repatriation program» and capitalists’ effort to maximize profits. Offred mentions that many Jews who chose to stay were caught secretly practicing Judaism and executed.

Legitimate women[edit]

- Wives

- The top social level permitted to women, achieved by marriage to higher-ranking officers. Wives always wear blue dresses and cloaks, suggesting traditional depictions of the Virgin Mary in historic Christian art. When a Commander dies, his Wife becomes a Widow and must dress in black.

- Daughters

- The natural or adopted children of the ruling class. They wear white until marriage, which is arranged by the government. The narrator’s daughter may have been adopted by an infertile Wife and Commander and she is shown in a photograph wearing a long white dress.

- Handmaids

The bonnets that Handmaids wear are modelled on Old Dutch Cleanser’s faceless mascot, which Atwood in childhood found frightening.[8]

- Fertile women whose social function is to bear children for infertile Wives. Handmaids dress in ankle-length red dresses, white caps, and heavy boots. In summer, they change into lighter-weight (but still ankle-length) dresses and slatted shoes. When in public, in winter, they wear ankle-length red cloaks, red gloves, and heavy white bonnets, which they call «wings» because the sides stick out, blocking their peripheral vision and shielding their faces from view. Handmaids are women of proven fertility who have broken the law. The law includes both gender crimes, such as lesbianism, and religious crimes, such as adultery (redefined to include sexual relationships with divorced partners since divorce is no longer legal). The Republic of Gilead justifies the use of the handmaids for procreation by referring to two biblical stories: Genesis 30:1–13 and Genesis 16:1–4. In the first story, Jacob’s infertile wife Rachel offers up her handmaid Bilhah to be a surrogate mother on her behalf, and then her sister Leah does the same with her own handmaid Zilpah (even though Leah has already given Jacob many sons). In the other story, which appears earlier in Genesis but is cited less frequently, Abraham has sex with his wife’s handmaid, Hagar. Handmaids are assigned to Commanders and live in their houses. When unassigned, they live at training centers. Handmaids who successfully bear children continue to live at their commander’s house until their children are weaned, at which point they are sent to a new assignment. Those who produce children will never be declared «Unwomen» or sent to the Colonies, even if they never have another baby.

- Aunts

- Trainers of the Handmaids. They dress in brown. Aunts promote the role of Handmaid as an honorable way for a sinful woman to redeem herself. They police the Handmaids, beating some and ordering the maiming of others. The aunts have an unusual amount of autonomy, compared to other women of Gilead. They are the only class of women permitted to read, although this is only to fulfil the administrative aspect of their role.

- Marthas

- They are older, infertile women who have domestic skills and are compliant, making them suitable as servants within the households of the Commanders and their families. They dress in green. The title of «Martha» is based on the account of Jesus at the home of Martha and Mary (Gospel of Luke 10:38–42), in which Mary listens to Jesus while her sister Martha works at «all the preparations that had to be made». The duties of Marthas may be tasked to Guardians of the Faith, paramilitary officers who police Gilead’s civilian population and guard the Commanders, wherever conflict with Gilead’s laws may arise, such as with cleaning a Commander’s study where Marthas could obtain literature.

- Econowives

- Women married to men of lower-rank, not members of the elite. They are expected to perform all the female functions: domestic duties, companionship, and child-bearing. Their dress is multicoloured red, blue, and green to reflect these multiple roles, and is made of notably cheaper material.

The division of labour among the women generates some resentment. Marthas, Wives and Econowives perceive Handmaids as promiscuous and are taught to scorn them. Offred mourns that the women of the various groups have lost their ability to empathize with each other.

The Ceremony[edit]

«The Ceremony» is a non-marital sexual act sanctioned for reproduction. The ritual requires the Handmaid to lie on her back between the legs of the Wife during the sex act as if they were one person. The Wife has to invite the Handmaid to share her power this way; many Wives consider this both humiliating and offensive. Offred describes the ceremony:

My red skirt is hitched up to my waist, though no higher. Below it the Commander is fucking. What he is fucking is the lower part of my body. I do not say making love, because this is not what he’s doing. Copulating too would be inaccurate because it would imply two people and only one is involved. Nor does rape cover it: nothing is going on here that I haven’t signed up for.[38]

Reception[edit]

Critical reception[edit]

The Handmaid’s Tale received critical acclaim, helping to cement Atwood’s status as a prominent writer of the 20th century. Not only was the book deemed well-written and compelling, but Atwood’s work was notable for sparking intense debates both in and out of academia.[13] Atwood maintains that the Republic of Gilead is only an extrapolation of trends already seen in the United States at the time of her writing, a view supported by other scholars studying The Handmaid’s Tale.[39] Many have placed The Handmaid’s Tale in the same category of dystopian fiction as Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World,[16] a categorization that Atwood has accepted and reiterated in many articles and interviews.[17]

Even today, many reviewers hold that Atwood’s novel remains as foreboding and powerful as ever, largely because of its basis in historical fact.[21][23] Yet when her book was first published in 1985, not all reviewers were convinced of the «cautionary tale» Atwood presented. For example, Mary McCarthy’s 1986 New York Times review argued that The Handmaid’s Tale lacked the «surprised recognition» necessary for readers to see «our present selves in a distorting mirror, of what we may be turning into if current trends are allowed to continue».[26]

The 2017 television series led to debate on whether parallels[clarification needed] could be drawn between the series (and book) and America during the presidency of Donald Trump.[40]

Genre classification[edit]

The Handmaid’s Tale is a feminist dystopian novel,[41][42] combining the characteristics of dystopian fiction: «a genre that projects an imaginary society that differs from the author’s own, first, by being significantly worse in important respects and second by being worse because it attempts to reify some utopian ideal,»[43] with the feminist utopian ideal which: «sees men or masculine systems as the major cause of social and political problems (e.g. war), and presents women as not only at least the equals of men but also as the sole arbiters of their reproductive functions».[44][45]

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction notes that dystopian images are almost invariably images of future society, «pointing fearfully at the way the world is supposedly going in order to provide urgent propaganda for a change in direction.»[46] Atwood’s stated intent was indeed to dramatize potential consequences of current trends.[47]

In 1985, reviewers hailed the book as a «feminist 1984,«[48] citing similarities between the totalitarian regimes under which both protagonists live, and «the distinctively modern sense of nightmare come true, the initial paralyzed powerlessness of the victim unable to act.»[49] Scholarly studies have expanded on the place of The Handmaid’s Tale in the dystopian and feminist traditions.[49][14][50][15][48]

The classification of utopian and dystopian fiction as a sub-genre of the collective term, speculative fiction, alongside science fiction, fantasy, and horror is a relatively recent convention. Dystopian novels have long been discussed as a type of science fiction, however, with publication of The Handmaid’s Tale, Atwood distinguished the terms science fiction and speculative fiction quite intentionally. In interviews and essays, she has discussed why, observing:

I like to make a distinction between science fiction proper and speculative fiction. For me, the science fiction label belongs on books with things in them that we can’t yet do, such as going through a wormhole in space to another universe; and speculative fiction means a work that employs the means already to hand, such as DNA identification and credit cards, and that takes place on Planet Earth. But the terms are fluid.[51]

Atwood acknowledges that others may use the terms interchangeably, but she notes her interest in this type of work is to explore themes in ways that «realistic fiction» cannot do.[51]

Among a few science fiction aficionados, however, Atwood’s comments were considered petty and contemptuous. (The term speculative fiction was indeed employed that way by certain New Wave writers in the 1960s and early 1970s to express their dissatisfaction with traditional or establishment science fiction.) Hugo-winning science fiction critic David Langford observed in a column: «The Handmaid’s Tale won the very first Arthur C. Clarke Award in 1987. She’s been trying to live this down ever since.»[52]

Reception in schools[edit]

Atwood’s novels, and especially her works of speculative fiction, The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake, are frequently offered as examples for the final, open-ended question on the American Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition exam each year.[53] As such, her books are often assigned in high-school classrooms to students taking this Advanced Placement course, despite the mature themes the work presents. Atwood herself has expressed surprise that her books are being assigned to high-school audiences, largely due to her own censored education in the 1950s, but she has assured readers that this increased attention from high-school students has not altered the material she has chosen to write about since.[54]

Challenges[edit]

There has been some criticism of use of The Handmaid’s Tale in schools. Some challenges have come from parents concerned about the explicit sexuality and other adult themes in the book, while others have argued that The Handmaid’s Tale depicts a negative view of religion. This view is supported by some academics who propose that the work satirizes contemporary religious fundamentalists in the United States, offering a feminist critique of the trends this movement to the Right represents.[55][56]

The American Library Association lists The Handmaid’s Tale as number 37 on the «100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–2000».[57] In 2019, The Handmaid’s Tale is still listed as the seventh-most challenged book because of profanity, vulgarity, and sexual overtones.[58] Atwood participated in discussing The Handmaid’s Tale as the subject of an ALA discussion series titled «One Book, One Conference».[59]

Some challenges include,

- A 2009 parent in Toronto accused the book of being anti-Christian and anti-Islamic because the women are veiled and polygamy is allowed.[60][61] Rushowy reports that «The Canadian Library Association says there is ‘no known instance of a challenge to this novel in Canada’ but says the book was called anti-Christian and pornographic by parents after being placed on a reading list for secondary students in Texas in the 1990s.»[62]

- A 2012 challenge as required reading for a Page High School International Baccalaureate class and as optional reading for Advanced Placement reading courses at Grimsley High School in Greensboro, North Carolina because the book is «sexually explicit, violently graphic and morally corrupt». Some parents thought the book is “detrimental to Christian values».[63]

- In November 2012, two parents protested against the inclusion of the book on a required reading list in Guilford County, North Carolina. The parents presented the school board with a petition signed by 2,300 people, prompting a review of the book by the school’s media advisory committee. According to local news reports, one of the parents said «she felt Christian students are bullied in society, in that they’re made to feel uncomfortable about their beliefs by non-believers. She said including books like The Handmaid’s Tale contributes to that discomfort, because of its negative view on religion and its anti-biblical attitudes toward sex.»[64]

- In November 2021 in Wichita, Kansas, «The Goddard school district has removed more than two dozen books from circulation in the district’s school libraries, citing national attention and challenges to the books elsewhere.»[65]

In May 2022, Atwood announced that, in a joint project undertaken with Penguin Random House, an «unburnable» copy of the book would be produced and auctioned off, the project intended to «stand as a powerful symbol against censorship.”[66] On 7 June 2022, the unique, «unburnable» copy was sold through Sotheby’s in New York for $130,000.[67]

In higher education[edit]

In institutions of higher education, professors have found The Handmaid’s Tale to be useful, largely because of its historical and religious basis and Atwood’s captivating delivery. The novel’s teaching points include: introducing politics and the social sciences to students in a more concrete way;[68][69] demonstrating the importance of reading to our freedom, both intellectual and political;[70] and acknowledging the «most insidious and violent manifestations of power in Western history» in a compelling manner.[71]

The chapter entitled «Historical Notes» at the end of the novel also represents a warning to academics who run the risk of misreading and misunderstanding historical texts, pointing to the satirized Professor Pieixoto as an example of a male scholar who has taken over and overpowered Offred’s narrative with his own interpretation.[72]

Academic reception[edit]

Feminist analysis[edit]

Much of the discussion about The Handmaid’s Tale has centred on its categorization as feminist literature. Atwood does not see the Republic of Gilead as a purely feminist dystopia, as not all men have greater rights than women.[22] Instead, this society presents a typical dictatorship: «shaped like a pyramid, with the powerful of both sexes at the apex, the men generally outranking the women at the same level; then descending levels of power and status with men and women in each, all the way down to the bottom, where the unmarried men must serve in the ranks before being awarded an Econowife».[22]

Econowives are women married to men that don’t belong to the elite and who are expected to carry out child-bearing, domestic duties, and traditional companionship. When asked about whether her book was feminist, Atwood stated that the presence of women and what happens to them are important to the structure and theme of the book. This aisle of feminism, by default, would make a lot of books feminist. However, she is adamant in her stance that her book did not represent the brand of feminism that victimizes or strips women of moral choice.[73]

Atwood has argued that while some of the observations that informed the content of The Handmaid’s Tale may be feminist, her novel is not meant to say «one thing to one person» or serve as a political message—instead, The Handmaid’s Tale is «a study of power, and how it operates and how it deforms or shapes the people who are living within that kind of regime».[16][17]

Some scholars have offered a feminist interpretation, connecting Atwood’s use of religious fundamentalism in the pages of The Handmaid’s Tale to a condemnation of their presence in current American society.[55][56] Atwood goes on to describe her book as not a critique of religion, but a critique of the use of religion as a «front for tyranny.»[74] Others have argued that The Handmaid’s Tale critiques typical notions of feminism, as Atwood’s novel appears to subvert the traditional «women helping women» ideals of the movement and turn toward the possibility of «the matriarchal network … and a new form of misogyny: women’s hatred of women».[75]

Scholars have analyzed and made connections to patriarchal oppression in The Handmaid’s Tale and oppression of women today. Aisha Matthews tackles the effects of institutional structures that oppress woman and womanhood and connects those to the themes present in The Handmaid’s Tale. She first asserts that structures and social frameworks, such as the patriarchy and societal role of traditional Christian values, are inherently detrimental to the liberation of womanhood. She then makes the connection to the relationship between Offred, Serena Joy, and their Commander, explaining that through this «perversion of traditional marriage, the Biblical story of Rachel, Jacob, and Bilhah is taken too literally.» Their relationship and other similar relationships in The Handmaid’s Tale mirror the effects of patriarchal standards of womanliness.[76]

- Sex and occupation

In the world of The Handmaid’s Tale, the sexes are strictly divided. Gilead’s society values white women’s reproductive commodities over those of other ethnicities. Women are categorized «hierarchically according to class status and reproductive capacity» as well as «metonymically colour-coded according to their function and their labour» (Kauffman 232). The Commander expresses his personal opinion that women are considered inferior to men, as the men are in a position where they have power to control society.

Women are segregated by clothing, as are men. With rare exception, men wear military or paramilitary uniforms. All classes of men and women are defined by the colours they wear, drawing on colour symbolism and psychology. All lower-status individuals are regulated by this dress code. All «non-persons» are banished to the «Colonies». Sterile, unmarried women are considered to be non-persons. Both men and women sent there wear grey dresses.

The women, particularly the handmaids, are stripped of their individual identities as they lack formal names, taking on their assigned commander’s first name in most cases.

- Unwomen

Sterile women, the unmarried, some widows, feminists, lesbians, nuns, and politically dissident women: all women who are incapable of social integration within the Republic’s strict gender divisions. Gilead exiles Unwomen to «the Colonies», areas both of agricultural production and deadly pollution. Joining them are handmaids who fail to bear a child after three two-year assignments.

- Jezebels

Jezebels are women who are forced to become prostitutes and entertainers. They are available only to the Commanders and to their guests. Offred portrays Jezebels as attractive and educated; they may be unsuitable as handmaids due to temperament. They have been sterilized, a surgery that is forbidden to other women. They operate in unofficial but state-sanctioned brothels, unknown to most women.

Jezebels, whose title comes from Jezebel in the Bible, dress in the remnants of sexualized costumes from «the time before», such as cheerleaders’ costumes, school uniforms, and Playboy Bunny costumes. Jezebels can wear make-up, drink alcohol and socialize with men, but are tightly controlled by the Aunts. When they pass their sexual prime or their looks fade, they are discarded without any precision as to whether they are killed or sent to the Colonies in the novel.

Race analysis[edit]

African Americans, the main non-White ethnic group in this society, are called the Children of Ham. A state TV broadcast mentions they have been relocated «en masse» to «National Homelands» in the Midwest, which are suggestive of the apartheid-era homelands (Bantustans) set up by South Africa. Ana Cottle characterized The Handmaid’s Tale as «White feminism», noting that Atwood does away with Black people in a few lines by relocating the «Children of Ham» while borrowing heavily from the African-American experience and applying it to White women.[77][78]

It is implied that Native Americans living in territories under the rule of Gilead are exterminated. Jews are given a choice between converting to the state religion or being «repatriated» to Israel. Converts who were subsequently discovered with any symbolic representations or artifacts of Judaism were executed, and the repatriation scheme was privatized, with the result that many Jews died en route to Israel.

Awards[edit]

- 1985 – Governor General’s Award for English-language fiction (winner)[79]

- 1986 – Booker Prize (nominated)[80]

- 1986 – Nebula Award (nominated)[81]

- 1986 – Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Fiction (winner)[82]

- 1987 – Arthur C. Clarke Award (winner)[83][a]

- 1987 – Prometheus Award (nominated)[84][b]

- 1987 – Commonwealth Writers’ Prize: Best Book (winner of the Canada and the Caribbean region)[85]

In other media[edit]

Audio[edit]

- An audiobook of the unabridged text, read by Claire Danes (ISBN 9781491519110), won the 2013 Audie Award for fiction.[86]

- In 2014, Canadian band Lakes of Canada released their album Transgressions, which is intended to be a concept album inspired by The Handmaid’s Tale.[87]

- On his album Shady Lights from 2017, Snax references the novel and film adaption, specifically the character of Serena Joy, in the song «Make Me Disappear». The first verse reads, «You can call me Serena Joy. Drink in hand, in front of the TV, I’m teary-eyed, adjusting my CC.»

- A full cast audiobook entitled The Handmaid’s Tale: Special Edition was released in 2017, read by Claire Danes, Margaret Atwood, Tim Gerard Reynolds, and others.[88]

- An audiobook of the unabridged text, read by Betty Harris, was released in 2019 by Recorded Books, Inc.[89]

Film[edit]

- The 1990 film The Handmaid’s Tale was based on a screenplay by Harold Pinter and directed by Volker Schlöndorff. It stars Natasha Richardson as Offred, Faye Dunaway as Serena Joy, and Robert Duvall as The Commander (Fred).

Radio[edit]

- A dramatic adaptation of the novel for radio was produced for BBC Radio 4 by John Dryden in 2000.[90]

- In 2002 CBC Radio commissioned Michael O’Brien to adapt Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale for radio.

Stage[edit]

- A stage adaptation written and directed by Bruce Shapiro played at Tufts University in 1989.[91]

- An operatic adaptation, The Handmaid’s Tale, by Poul Ruders, premiered in Copenhagen on 6 March 2000, and was performed by the English National Opera, in London, in 2003.[92] It was the opening production of the 2004–2005 season of the Canadian Opera Company.[93] Boston Lyric Opera mounted a production in May 2019.[94]

- A stage adaptation of the novel, by Brendon Burns, for the Haymarket Theatre, Basingstoke, England, toured the UK in 2002.[95]

- A ballet adaptation choreographed by Lila York and produced by the Royal Winnipeg Ballet premiered on 16 October 2013. Amanda Green appeared as Offred and Alexander Gamayunov as The Commander.[96]

- A one-woman stage show, adapted from the novel, by Joseph Stollenwerk premiered in the U.S. in January 2015.[97]

Television[edit]

- Hulu has produced a television series based on the novel, starring Elisabeth Moss as Offred. The first three episodes were released on 26 April 2017, with subsequent episodes following on a weekly basis. Margaret Atwood served as consulting producer.[98] The series won eight Primetime Emmy Awards in 2017, including Outstanding Drama Series and Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series (Moss).[99] The series was renewed for a second season, which premiered on 25 April 2018, and in May 2018, Hulu announced renewal for a third season. The third season premiered on 5 June 2019. Hulu announced season 4, consisting of 10 episodes, with production set to start in March 2020. This was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[100] Season 4 premiered on 28 April 2021; season 5, on September 14, 2022.

Sequel[edit]

In November 2018, Atwood announced the sequel, titled The Testaments, which was published in September 2019.[101] The novel is set fifteen years after Offred’s final scene, with the testaments of three female narrators from Gilead.[102]

See also[edit]

- Canadian literature

- Feminist science fiction

- Reproduction and pregnancy in speculative fiction

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ The Handmaid’s Tale is the inaugural winner of this award for the best science fiction novel published in the United Kingdom during the previous year.

- ^ The Prometheus Award is an award for libertarian science fiction novels given out annually by the Libertarian Futurist Society, which also publishes a quarterly journal, Prometheus.

Citations[edit]

- ^ Cosstick, Ruth (January 1986). «Book review: The Handmaids Tale«. Canadian Review of Materials. Vol. 14, no. 1. CM Archive. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2016.

Tad Aronowicz’s jaggedly surrealistic cover design is most appropriate.

- ^ Brown, Sarah (15 April 2008). Tragedy in Transition. p. 45. ISBN 9780470691304.

- ^ Taylor, Kevin (21 September 2018). Christ the Tragedy of God: A Theological Exploration of Tragedy. ISBN 9781351607834.

- ^ Kendrick, Tom (2003). Margaret Atwood’s Textual Assassinations: Recent Poetry and Fiction. p. 148. ISBN 9780814209295.

- ^ Stray, Christopher (16 October 2013). Remaking the Classics: Literature, Genre and Media in Britain 1800-2000. p. 78. ISBN 9781472538604.

- ^ «The Handmaid’s Tale Study Guide: About Speculative Fiction». Gradesaver. 22 May 2009.

- ^ a b Isomaa, Saija; Korpua, Jyrki; Teittinen, Jouni (27 August 2020). New Perspectives on Dystopian Fiction in Literature and Other Media. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-5275-5872-4.

Although theonomy originally refers to the Biblical past, in fiction it can be seen as a possible form of futuristic dystopian society, as is evident in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). The theonomic government ruled by Lord Protector Cromwell in The Adventures of Luther Arkwright is quite different from the one in Atwood’s novel because there is a constant power struggle.

- ^ a b c d e f g Atwood, Margaret (10 March 2017). «Margaret Atwood on What ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Means in the Age of Trump». The New York Times. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ a b Atwood, Margaret (2019). The Handmaid’s Tale. Canada: McClelland and Stewart. pp. xi–xviii. ISBN 978-0-7710-0879-5.

- ^ «The Big Jubilee Read: A literary celebration of Queen Elizabeth II’s record-breaking reign». BBC. 17 April 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ «The Handmaid’s Tale». Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Atwood, Margaret (17 February 1986). The Handmaid’s Tale — Margaret Atwood. Google Books. ISBN 0547345666. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ a b Greene, Gayle (July 1986). «Choice of Evils». The Women’s Review of Books. 3 (10): 14–15. doi:10.2307/4019952. JSTOR 4019952.

- ^ a b c d e Malak, Amin (Spring 1997). «Margaret Atwood’s ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ and the Dystopian Tradition». Canadian Literature (112): 9–16.

- ^ a b Neuman, Sally (Summer 2006). «Just a Backlash’: Margaret Atwood, Feminism, and The Handmaid’s Tale». University of Toronto Quarterly. 75 (3): 857–868.

- ^ a b c d e Rothstein, Mervyn (17 February 1986). «No Balm in Gilead for Margaret Atwood». The New York Times. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Atwood, Margaret (May 2004). «The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake «In Context»«. PMLA. 119 (3): 513–517. doi:10.1632/003081204X20578. S2CID 162973994.

- ^ a b c Hammill 2008, p. 525.

- ^ a b c Hammill 2008, p. 527.

- ^ Croteau, David A. (1 February 2010). You Mean I Don’t Have to Tithe?: A Deconstruction of Tithing and a Reconstruction of Post-Tithe Giving. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-60608-405-2.

Theonomists (or, Christian Reconstructionists) view themselves in the tradition of Calvin, the Westminster Confession, and the new england Puritans.

- ^ a b Robertson, Adi (20 December 2014). «Does The Handmaid’s Tale hold up?». The Verge. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Atwood, Margaret (20 January 2012). «Haunted by the Handmaid’s Tale». The Guardian. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b Newman, Charlotte (25 September 2010). «The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood». The Guardian. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Williams, Layton E. (25 April 2017). «Margaret Atwood on Christianity, ‘The Handmaid’s Tale,’ and What Faithful Activism Looks Like Today». Sojourners. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Atwood, Margaret (17 November 2001). «Taking the veil». The Guardian. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Mary (9 February 1986). «Book Review». The New York Times. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ a b c «The Handmaid’s Tale Study Guide: Character List». Gradesaver. 22 May 2009.

- ^ «The Forgotten Handmaid’s Tale». The Atlantic, 24 March 2015.

- ^ Atwood 1986, p. 220.

- ^ Getz, Dana (26 April 2017). «Offred’s Real Name In ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Is The Only Piece Of Power She Still Holds». Bustle.

In Margaret Atwood’s original novel, Offred’s real name is never revealed. Many eagle-eyed readers deduced that it was June based on contextual clues: Of the names the Handmaids trade in hushed tones as they lie awake at night, «June» is the only one that’s never heard again once Offred is narrating.

- ^ Madonne 1991[page needed]

- ^ Oates, Joyce Carol (2 November 2006). «Margaret Atwood’s Tale». The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Atwood 1998, An Interview: ‘Q: We can figure out that the main character lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts’

- ^ McCarthy, Mary (9 February 1986). «Breeders, Wives and Unwomen». The New York Times Book Review. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d O’Hare, Kate (16 April 2017). «The Handmaid’s Tale on Hulu: What Should Catholics Think?». Faith & Family Media Blog. Family Theater Productions. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Lucie-Smith, Alexander (29 May 2017). «Should Catholics watch The Handmaid’s Tale?». The Catholic Herald. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Blondiau, Eloise (28 April 2017). «Reflecting on the frightening lessons of ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’«. America. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ Atwood 1998, p. 94.

- ^ Armbruster, Jane (Fall 1990). «Memory and Politics – A Reflection on «The Handmaid’s Tale»«. Social Justice. 3 (41): 146–152. JSTOR 29766564.

- ^ For articles that attempt to draw parallels between The Handmaid’s Tale and Trump’s election as President, see:

- Nally, Claire (31 May 2017). «How The Handmaid’s Tale is being transformed from fantasy into fact». The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Brooks, Katherine (24 May 2017). «How ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Villains Were Inspired By Trump». Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Robertson, Adi (9 November 2016). «In Trump’s America, The Handmaid’s Tale matters more than ever». The Verge. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- Douthat, Ross (24 May 2017). «The Handmaid’s Tale,’ and Ours». The New York Times. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

For articles that dispute such parallels, see:

- Crispin, Jessa (2 May 2017). «The Handmaid’s Tale is just like Trump’s America? Not so fast». The Guardian. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- Smith, Kyle (28 April 2017). «Sorry: ‘Handmaid’s Tale’ tells us nothing about Trump’s America». New York Post. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Hill, Melissa Sue; Lee, Michelle, eds. (2019). «Themes and Construction: The Handmaid’s Tale». Novels for Students. Vol. 60. Gale. Gale H1430008961.

- ^ «Dystopias in Contemporary Literature». Contemporary Literary Criticism Select. Gale. 2008 – via Literature Resource Center.

- ^ Beauchamp, Gorman (Autumn 2009). «The Politics of The Handmaid’s Tale». The Midwest Quarterly. 51: 11.

- ^ Gearhart, Sally Miller (1984). «Future Visions: Today’s Politics: Feminist Utopias in Review». In Baruch, Elaine Hoffman; Rohrlich, Ruby (eds.). Women in Search of Utopia: Mavericks and Mythmakers. New York: Shocken Books. pp. 296. ISBN 0805239006.

- ^ Barr, Marleen S.; Smith, Nicholas D. (1983). Women and Utopia: Critical Interpretations. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 9780819135599.

- ^ «Dystopias». The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: SFE (3rd ed.). 25 March 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ «An Interview with Margaret Atwood on her novel, The Handmaid’s Tale» (PDF). Nashville Public Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ a b Davidson, Arnold (1988). «Future Tense: Making History in The Handmaid’s Tale». In Van Spanckeren, Kathryn (ed.). Margaret Atwood: Vision and Forms. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 113–121.

- ^ a b Feuer, Lois (Winter 1997). «The Calculus of Love and Nightmare: The Handmaid’s Tale and the Dystopian Tradition». Critique. 38 (2): 83–95.

- ^ Rubenstein, Roberta (1988). «Nature and Nurture in Dystopia: The Handmaid’s Tale». In Van Spanckeren, Kathryn (ed.). Margaret Atwood: Vision and Forms. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 12. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ a b Atwood, Margaret (17 June 2005). «Aliens have taken the place of angels». The Guardian. UK.

If you’re writing about the future and you aren’t doing forecast journalism, you’ll probably be writing something people will call either science fiction or speculative fiction. I like to make a distinction between science fiction proper and speculative fiction. For me, the science fiction label belongs on books with things in them that we can’t yet do, such as going through a wormhole in space to another universe; and speculative fiction means a work that employs the means already to hand, such as DNA identification and credit cards, and that takes place on Planet Earth. But the terms are fluid. Some use speculative fiction as an umbrella covering science fiction and all its hyphenated forms–science fiction fantasy, and so forth–and others choose the reverse… I have written two works of science fiction or, if you prefer, speculative fiction: The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake. Here are some of the things these kinds of narratives can do that socially realistic novels cannot do.

- ^ Langford, David (August 2003). «Bits and Pieces». SFX (107).

- ^ «AP English Literature and Composition Exam». College Board. 10 July 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Perry, Douglas (30 December 2014). «Margaret Atwood and the ‘Four Unwise Republicans’: 12 surprises from the legendary writer’s Reddit AMA». The Oregonian. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ a b Hines, Molly (2006). Margaret Atwood’s «The Handmaid’s Tale»: Fundamentalist religiosity and the oppression of women (MA thesis). Angelo State University. ProQuest 304914133.

- ^ a b Mercer, Naomi (2013). «Subversive Feminist Thrusts»: Feminist Dystopian Writing and Religious Fundamentalism in Margaret Atwood’s «The Handmaid’s Tale», Louise Marley’s «The Terrorists of Irustan», Marge Piercy’s «He, She and It», and Sheri S. Tepper’s «Raising the Stones» (PhD dissertation). University of Wisconsin–Madison. ProQuest 1428851608.

- ^ «The 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–2000». American Library Association. 27 March 2013.

- ^ American Library Association (26 March 2013). «Top 10 Most Challenged Books Lists». Advocacy, Legislation & Issues. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Annual Report 2002–2003: One Book, One Conference». American Library Association. June 2003. Archived from the original on 1 December 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2009. Concerns inaugural program featuring Margaret Atwood held in Toronto, 19–25 June 2003.

- ^ Rushowy 2009: «Committee reviews ‘fictional drivel’ alleged to violate board policy on respect, profanity».

- ^ Toronto District School Board Report in The Toronto Star, 16 January 2009: «Atwood novel too brutal, sexist for school: Parent», by Kristin Rushowy, Education Reporter

- ^ Rushowy 2009b: «Committee to consider objection to book; concern may centre on sexuality, religion.»

- ^ Doyle, Robert P. (2017). Banned Books: Defending Our Freedom to Read. American Library Association. ISBN 978-0-8389-8962-3.

- ^ Carr, Mitch (2 November 2012). «Guilford County moms want reading list criteria changed». Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ «Goddard school district orders 29 books removed from circulation». KMUW. 9 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (24 May 2022). «Atwood responds to book bans with ‘unburnable’ edition of Handmaid’s Tale». The Guardian. New York. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Hills, Megan C. (7 June 2022). «An ‘unburnable’ copy of ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ sells for $130,000 at auction». CNN. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ Burack, Cynthia (Winter 1988–89). «Bringing Women’s Studies to Political Science: The Handmaid in the Classroom». NWSA Journal. 1 (2): 274–283. JSTOR 4315901.

- ^ Laz, Cheryl (January 1996). «Science Fiction and Introductory Sociology: The ‘Handmaid’ in the Classroom». Teaching Sociology. 24 (1): 54–63. doi:10.2307/1318898. JSTOR 1318898.

- ^ Bergmann, Harriet (December 1989). ««Teaching Them to Read»: A Fishing Expedition in the Handmaid’s Tale». College English. 51 (8): 847–854. doi:10.2307/378090. JSTOR 378090.

- ^ Larson, Janet (Spring 1989). «Margaret Atwood and the Future of Prophecy». Religion and Literature.

- ^ Stein, Karen (1996). «Margaret Atwood’s Modest Proposal: The Handmaid’s Tale». University of Rhode Island. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ Berry, Gregory R. (June 2010). «Book Review: Margaret Atwood The Year of the Flood New York, NY: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2009». Organization & Environment. 23 (2): 248–250. doi:10.1177/1086026610368388. ISSN 1086-0266. S2CID 143937316.

- ^ Millard, Scott (19 June 2007). «Literature Resource Center2007229Literature Resource Center. Farmington Hills, MI: Thomson Gale Last visited December 2006. Contact Thomson Gale for pricing information URL: www.gale.com/LitRC/». Reference Reviews. 21 (5): 35–36. doi:10.1108/09504120710755572. ISSN 0950-4125.

- ^ Callaway, Alanna (2008). «Women disunited: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale as a critique of feminism». San Jose State University. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Matthews, Aisha (18 August 2018). «Gender, Ontology, and the Power of the Patriarchy: A Postmodern Feminist Analysis of Octavia Butler’s Wild Seed and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale». Women’s Studies. 47 (6): 637–656. doi:10.1080/00497878.2018.1492403. ISSN 0049-7878. S2CID 150270608.

- ^ «The Handmaid’s Tale: A White Feminist Dystopia». theestablishment.co. 17 May 2017.

- ^ Bastién, Angelica Jade (June 2017). «The Handmaid’s Tale’s Greatest Failing Is How It Handles Race». Vulture.

- ^ «Past Winners and Finalists». GGBooks. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ «1986». Booker Prize. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ «1986». Nebula Award. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ «1986 Los Angeles Times Book Prize — Fiction Winner and Nominees». Awards Archive. 25 March 2020.

- ^ «The Arthur C. Clarke Award». Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ «Libertarian Futurist Society». Libertarian Futurist Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ «Regional Winners 1987-2007.xls» (PDF). Commonwealth Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Gummere, Joe. «2013 Audie Awards® Finalists by category». joeaudio.com. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- ^ «Artists: Lakes of Canada». CBC Music. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ The Handmaid’s Tale: Special Edition.

- ^ «The Handmaid’s Tale». OverDrive. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ Karpf, Ann (15 January 2000). «The squeaks and drips of everyday life». The Guardian. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ «Tufts University: Department of Drama and Dance: Performances & Events». dramadance.tufts.edu. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

- ^ Clements, Andrew (5 April 2003). «Classical music & opera». The Guardian. UK.

- ^ Littler, William (15 December 2004), Opera Canada.

- ^ Allen, David (10 May 2019). «Review: ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Is a Brutal Triumph as Opera». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ «The Handmaid’s tale». UKTW.

- ^ «The Handmaid’s Tale debuts as ballet in Winnipeg». CA: CBC News. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Lyman, David (24 January 2015). «‘Handmaid’s Tale’ offers extreme view of future». Cincinnati.com.

- ^ Hardawar, Devindra (29 April 2016). «Hulu is adapting Margaret Atwood’s ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’«. Engadget. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Otterson, Joe (17 September 2017). «‘Hulu Carried to Emmys Glory by Eight Wins for ‘Handmaid’s Tale’«. Variety. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- ^ Holloway, Daniel (2 May 2018). «‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Renewed for Season 3 at Hulu». Variety. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ «Margaret Atwood announces sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale». CBC News, 28 November 2018.

- ^ Grady, Constance (4 September 2019). «Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale sequel is a giddy thrill ride». Vox. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

General and cited references[edit]

- (17 June 2005), «Aliens Have Taken the Place of Angels», The Guardian

- (14 January 2009), «Complaint Spurs School Board to Review Novel by Atwood», The Toronto Star.

- Alexander, Lynn (22 May 2009), «The Handmaid’s Tale Working Bibliography», Department of English, University of Tennessee at Martin. Hyperlinked to online resources for Alexander, Dr Lynn (Spring 1999), Women Writers: Magic, Mysticism, and Mayhem (course). Includes entry for book chap. by Kauffman.

- An Interview with Margaret Atwood on her novel, The Handmaid’s Tale (n.d.). In Nashville Public Library.

- Armrbuster, J. (1990). «Memory and Politics — A Reflection on ‘The Handmaid’s Tale'». Social Justice 17(3), 146–52.

- Atwood, Margaret (1985). The Handmaid’s Tale. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-0813-9. Atwood, Margaret (1986). The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Anchor Books. Atwood, Margaret (1998). The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Anchor Books (div. of Random House). ISBN 978-0-385-49081-8. Parenthetical page references are to the 1998 ed. Digitized 2 June 2008 by Google Books (311 pp.) (2005), La Servante écarlate [The Handmaid’s Tale] (in French), Rué, Sylviane transl, Paris: J’ai Lu, ISBN 978-2-290-34710-2.

- Atwood, M. (2004). The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake «In Context». PMLA, 119(3), 513–517.

- Atwood, M. (20 January 2012). «Haunted by the Handmaid’s Tale». The Guardian.

- Bergmann, H. F. (1989). «Teaching Them to Read: A Fishing Expedition in the Handmaid’s Tale». College English, 51(8), 847–854.

- Burack, C. (1988–89). «Bringing Women’s Studies to Political Science: The Handmaid in the Classroom». NWSA Journal 1(2), 274–83.

- Callaway, A. A. (2008). «Women disunited: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale as a critique of feminism». San Jose State University.