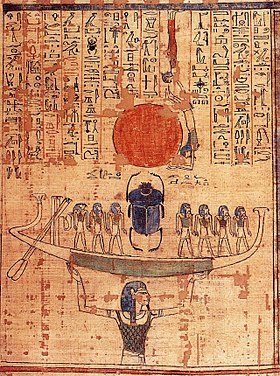

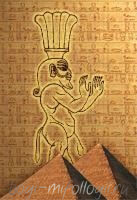

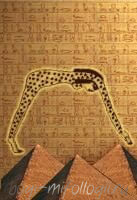

Nun, the embodiment of the primordial waters, lifts the barque of the sun god Ra into the sky at the moment of creation.

Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the world around them. The beliefs that these myths express are an important part of ancient Egyptian religion. Myths appear frequently in Egyptian writings and art, particularly in short stories and in religious material such as hymns, ritual texts, funerary texts, and temple decoration. These sources rarely contain a complete account of a myth and often describe only brief fragments.

Inspired by the cycles of nature, the Egyptians saw time in the present as a series of recurring patterns, whereas the earliest periods of time were linear. Myths are set in these earliest times, and myth sets the pattern for the cycles of the present. Present events repeat the events of myth, and in doing so renew maat, the fundamental order of the universe. Amongst the most important episodes from the mythic past are the creation myths, in which the gods form the universe out of primordial chaos; the stories of the reign of the sun god Ra upon the earth; and the Osiris myth, concerning the struggles of the gods Osiris, Isis, and Horus against the disruptive god Set. Events from the present that might be regarded as myths include Ra’s daily journey through the world and its otherworldly counterpart, the Duat. Recurring themes in these mythic episodes include the conflict between the upholders of maat and the forces of disorder, the importance of the pharaoh in maintaining maat, and the continual death and regeneration of the gods.

The details of these sacred events differ greatly from one text to another and often seem contradictory. Egyptian myths are primarily metaphorical, translating the essence and behavior of deities into terms that humans can understand. Each variant of a myth represents a different symbolic perspective, enriching the Egyptians’ understanding of the gods and the world.

Mythology profoundly influenced Egyptian culture. It inspired or influenced many religious rituals and provided the ideological basis for kingship. Scenes and symbols from myth appeared in art in tombs, temples, and amulets. In literature, myths or elements of them were used in stories that range from humor to allegory, demonstrating that the Egyptians adapted mythology to serve a wide variety of purposes.

Origins[edit]

The development of Egyptian myth is difficult to trace. Egyptologists must make educated guesses about its earliest phases, based on written sources that appeared much later.[1] One obvious influence on myth is the Egyptians’ natural surroundings. Each day the sun rose and set, bringing light to the land and regulating human activity; each year the Nile flooded, renewing the fertility of the soil and allowing the highly productive farming that sustained Egyptian civilization. Thus the Egyptians saw water and the sun as symbols of life and thought of time as a series of natural cycles. This orderly pattern was at constant risk of disruption: unusually low floods resulted in famine, and high floods destroyed crops and buildings.[2] The hospitable Nile valley was surrounded by harsh desert, populated by peoples the Egyptians regarded as uncivilized enemies of order.[3] For these reasons, the Egyptians saw their land as an isolated place of stability, or maat, surrounded and endangered by chaos. These themes—order, chaos, and renewal—appear repeatedly in Egyptian religious thought.[4]

Another possible source for mythology is ritual. Many rituals make reference to myths and are sometimes based directly on them.[5] But it is difficult to determine whether a culture’s myths developed before rituals or vice versa.[6] Questions about this relationship between myth and ritual have spawned much discussion among Egyptologists and scholars of comparative religion in general. In ancient Egypt, the earliest evidence of religious practices predates written myths.[5] Rituals early in Egyptian history included only a few motifs from myth. For these reasons, some scholars have argued that, in Egypt, rituals emerged before myths.[6] But because the early evidence is so sparse, the question may never be resolved for certain.[5]

In private rituals, which are often called «magical», the myth and the ritual are particularly closely tied. Many of the myth-like stories that appear in the rituals’ texts are not found in other sources. Even the widespread motif of the goddess Isis rescuing her poisoned son Horus appears only in this type of text. The Egyptologist David Frankfurter argues that these rituals adapt basic mythic traditions to fit the specific ritual, creating elaborate new stories (called historiolas) based on myth.[7] In contrast, J. F. Borghouts says of magical texts that there is «not a shred of evidence that a specific kind of ‘unorthodox’ mythology was coined… for this genre.»[8]

Much of Egyptian mythology consists of origin myths, explaining the beginnings of various elements of the world, including human institutions and natural phenomena. Kingship arises among the gods at the beginning of time and later passed to the human pharaohs; warfare originates when humans begin fighting each other after the sun god’s withdrawal into the sky.[9] Myths also describe the supposed beginnings of less fundamental traditions. In a minor mythic episode, Horus becomes angry with his mother Isis and cuts off her head. Isis replaces her lost head with that of a cow. This event explains why Isis was sometimes depicted with the horns of a cow as part of her headdress.[10]

Some myths may have been inspired by historical events. The unification of Egypt under the pharaohs, at the end of the Predynastic Period around 3100 BC, made the king the focus of Egyptian religion, and thus the ideology of kingship became an important part of mythology.[11] In the wake of unification, gods that were once local patron deities gained national importance, forming new relationships that linked the local deities into a unified national tradition. Geraldine Pinch suggests that early myths may have formed from these relationships.[12] Egyptian sources link the mythical strife between the gods Horus and Set with a conflict between the regions of Upper and Lower Egypt, which may have happened in the late Predynastic era or in the Early Dynastic Period.[13][Note 1]

After these early times, most changes to mythology developed and adapted preexisting concepts rather than creating new ones, although there were exceptions.[14] Many scholars have suggested that the myth of the sun god withdrawing into the sky, leaving humans to fight among themselves, was inspired by the breakdown of royal authority and national unity at the end of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – 2181 BC).[15] In the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC), minor myths developed around deities like Yam and Anat who had been adopted from Canaanite religion. In contrast, during the Greek and Roman eras (332 BC–641 AD), Greco-Roman culture had little influence on Egyptian mythology.[16]

Definition and scope[edit]

Scholars have difficulty defining which ancient Egyptian beliefs are myths. The basic definition of myth suggested by the Egyptologist John Baines is «a sacred or culturally central narrative». In Egypt, the narratives that are central to culture and religion are almost entirely about events among the gods.[17] Actual narratives about the gods’ actions are rare in Egyptian texts, particularly from early periods, and most references to such events are mere mentions or allusions. Some Egyptologists, like Baines, argue that narratives complete enough to be called «myths» existed in all periods, but that Egyptian tradition did not favor writing them down. Others, like Jan Assmann, have said that true myths were rare in Egypt and may only have emerged partway through its history, developing out of the fragments of narration that appear in the earliest writings.[18] Recently, however, Vincent Arieh Tobin[19] and Susanne Bickel have suggested that lengthy narration was not needed in Egyptian mythology because of its complex and flexible nature.[20] Tobin argues that narrative is even alien to myth, because narratives tend to form a simple and fixed perspective on the events they describe. If narration is not needed for myth, any statement that conveys an idea about the nature or actions of a god can be called «mythic».[19]

Content and meaning[edit]

Like myths in many other cultures, Egyptian myths serve to justify human traditions and to address fundamental questions about the world,[21] such as the nature of disorder and the ultimate fate of the universe.[20] The Egyptians explained these profound issues through statements about the gods.[20]

Egyptian deities represent natural phenomena, from physical objects like the earth or the sun to abstract forces like knowledge and creativity. The actions and interactions of the gods, the Egyptians believed, govern the behavior of all of these forces and elements.[22] For the most part, the Egyptians did not describe these mysterious processes in explicit theological writings. Instead, the relationships and interactions of the gods illustrated such processes implicitly.[23]

Most of Egypt’s gods, including many of the major ones, do not have significant roles in any mythic narratives,[24] although their nature and relationships with other deities are often established in lists or bare statements without narration.[25] For the gods who are deeply involved in narratives, mythic events are very important expressions of their roles in the cosmos. Therefore, if only narratives are myths, mythology is a major element in Egyptian religious understanding, but not as essential as it is in many other cultures.[26]

The sky depicted as a cow goddess supported by other deities. This image combines several coexisting visions of the sky: as a roof, as the surface of a sea, as a cow, and as a goddess in human form.[27]

The true realm of the gods is mysterious and inaccessible to humans. Mythological stories use symbolism to make the events in this realm comprehensible.[28] Not every detail of a mythic account has symbolic significance. Some images and incidents, even in religious texts, are meant simply as visual or dramatic embellishments of broader, more meaningful myths.[29][30]

Few complete stories appear in Egyptian mythological sources. These sources often contain nothing more than allusions to the events to which they relate, and texts that contain actual narratives tell only portions of a larger story. Thus, for any given myth the Egyptians may have had only the general outlines of a story, from which fragments describing particular incidents were drawn.[24] Moreover, the gods are not well-defined characters, and the motivations for their sometimes inconsistent actions are rarely given.[31] Egyptian myths are not, therefore, fully developed tales. Their importance lay in their underlying meaning, not their characteristics as stories. Instead of coalescing into lengthy, fixed narratives, they remained highly flexible and non-dogmatic.[28]

So flexible were Egyptian myths that they could seemingly conflict with each other. Many descriptions of the creation of the world and the movements of the sun occur in Egyptian texts, some very different from each other.[32] The relationships between gods were fluid, so that, for instance, the goddess Hathor could be called the mother, wife, or daughter of the sun god Ra.[33] Separate deities could even be syncretized, or linked, as a single being. Thus the creator god Atum was combined with Ra to form Ra-Atum.[34]

One commonly suggested reason for inconsistencies in myth is that religious ideas differed over time and in different regions.[35] The local cults of various deities developed theologies centered on their own patron gods.[36] As the influence of different cults shifted, some mythological systems attained national dominance. In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC) the most important of these systems was the cults of Ra and Atum, centered at Heliopolis. They formed a mythical family, the Ennead, that was said to have created the world. It included the most important deities of the time but gave primacy to Atum and Ra.[37] The Egyptians also overlaid old religious ideas with new ones. For instance, the god Ptah, whose cult was centered at Memphis, was also said to be the creator of the world. Ptah’s creation myth incorporates older myths by saying that it is the Ennead who carry out Ptah’s creative commands.[38] Thus, the myth makes Ptah older and greater than the Ennead. Many scholars have seen this myth as a political attempt to assert the superiority of Memphis’ god over those of Heliopolis.[39] By combining concepts in this way, the Egyptians produced an immensely complicated set of deities and myths.[40]

Egyptologists in the early twentieth century thought that politically motivated changes like these were the principal reason for the contradictory imagery in Egyptian myth. However, in the 1940s, Henri Frankfort, realizing the symbolic nature of Egyptian mythology, argued that apparently contradictory ideas are part of the «multiplicity of approaches» that the Egyptians used to understand the divine realm. Frankfort’s arguments are the basis for much of the more recent analysis of Egyptian beliefs.[41] Political changes affected Egyptian beliefs, but the ideas that emerged through those changes also have deeper meaning. Multiple versions of the same myth express different aspects of the same phenomenon; different gods that behave in a similar way reflect the close connections between natural forces. The varying symbols of Egyptian mythology express ideas too complex to be seen through a single lens.[28]

Sources[edit]

The sources that are available range from solemn hymns to entertaining stories. Without a single, canonical version of any myth, the Egyptians adapted the broad traditions of myth to fit the varied purposes of their writings.[42] Most Egyptians were illiterate and may therefore have had an elaborate oral tradition that transmitted myths through spoken storytelling. Susanne Bickel suggests that the existence of this tradition helps explain why many texts related to myth give little detail: the myths were already known to every Egyptian.[43] Very little evidence of this oral tradition has survived, and modern knowledge of Egyptian myths is drawn from written and pictorial sources. Only a small proportion of these sources has survived to the present, so much of the mythological information that was once written down has been lost.[25] This information is not equally abundant in all periods, so the beliefs that Egyptians held in some eras of their history are more poorly understood than the beliefs in better documented times.[44]

Religious sources[edit]

Many gods appear in artwork from the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt’s history (c. 3100–2686 BC), but little about the gods’ actions can be gleaned from these sources because they include minimal writing. The Egyptians began using writing more extensively in the Old Kingdom, in which appeared the first major source of Egyptian mythology: the Pyramid Texts. These texts are a collection of several hundred incantations inscribed in the interiors of pyramids beginning in the 24th century BC. They were the first Egyptian funerary texts, intended to ensure that the kings buried in the pyramid would pass safely through the afterlife. Many of the incantations allude to myths related to the afterlife, including creation myths and the myth of Osiris. Many of the texts are likely much older than their first known written copies, and they therefore provide clues about the early stages of Egyptian religious belief.[45]

During the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), the Pyramid Texts developed into the Coffin Texts, which contain similar material and were available to non-royals. Succeeding funerary texts, like the Book of the Dead in the New Kingdom and the Books of Breathing from the Late Period (664–323 BC) and after, developed out of these earlier collections. The New Kingdom also saw the development of another type of funerary text, containing detailed and cohesive descriptions of the nocturnal journey of the sun god. Texts of this type include the Amduat, the Book of Gates, and the Book of Caverns.[42]

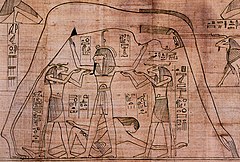

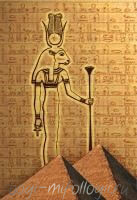

Temple decoration at Dendera, depicting the goddesses Isis and Nephthys watching over the corpse of their brother Osiris

Temples, whose surviving remains date mostly from the New Kingdom and later, are another important source of myth. Many temples had a per-ankh, or temple library, storing papyri for rituals and other uses. Some of these papyri contain hymns, which, in praising a god for its actions, often refer to the myths that define those actions. Other temple papyri describe rituals, many of which are based partly on myth.[46] Scattered remnants of these papyrus collections have survived to the present. It is possible that the collections included more systematic records of myths, but no evidence of such texts has survived.[25] Mythological texts and illustrations, similar to those on temple papyri, also appear in the decoration of the temple buildings. The elaborately decorated and well-preserved temples of the Ptolemaic and Roman periods (305 BC–AD 380) are an especially rich source of myth.[47]

The Egyptians also performed rituals for personal goals such as protection from or healing of illness. These rituals are often called «magical» rather than religious, but they were believed to work on the same principles as temple ceremonies, evoking mythical events as the basis for the ritual.[48]

Information from religious sources is limited by a system of traditional restrictions on what they could describe and depict. The murder of the god Osiris, for instance, is never explicitly described in Egyptian writings.[25] The Egyptians believed that words and images could affect reality, so they avoided the risk of making such negative events real.[49] The conventions of Egyptian art were also poorly suited for portraying whole narratives, so most myth-related artwork consists of sparse individual scenes.[25]

Other sources[edit]

References to myth also appear in non-religious Egyptian literature, beginning in the Middle Kingdom. Many of these references are mere allusions to mythic motifs, but several stories are based entirely on mythic narratives. These more direct renderings of myth are particularly common in the Late and Greco-Roman periods when, according to scholars such as Heike Sternberg, Egyptian myths reached their most fully developed state.[50]

The attitudes toward myth in nonreligious Egyptian texts vary greatly. Some stories resemble the narratives from magical texts, while others are more clearly meant as entertainment and even contain humorous episodes.[50]

A final source of Egyptian myth is the writings of Greek and Roman writers like Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, who described Egyptian religion in the last centuries of its existence. Prominent among these writers is Plutarch, whose work De Iside et Osiride contains, among other things, the longest ancient account of the myth of Osiris.[51] These authors’ knowledge of Egyptian religion was limited because they were excluded from many religious practices, and their statements about Egyptian beliefs are affected by their biases about Egypt’s culture.[25]

Cosmology[edit]

Maat[edit]

Main article: Maat

The Egyptian word written m3ˁt, often rendered maat or ma’at, refers to the fundamental order of the universe in Egyptian belief. Established at the creation of the world, maat distinguishes the world from the chaos that preceded and surrounds it. Maat encompasses both the proper behavior of humans and the normal functioning of the forces of nature, both of which make life and happiness possible. Because the actions of the gods govern natural forces and myths express those actions, Egyptian mythology represents the proper functioning of the world and the sustenance of life itself.[52]

To the Egyptians, the most important human maintainer of maat is the pharaoh. In myth the pharaoh is the son of a variety of deities. As such, he is their designated representative, obligated to maintain order in human society just as they do in nature, and to continue the rituals that sustain them and their activities.[53]

Shape of the world[edit]

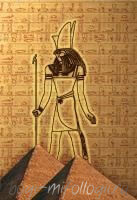

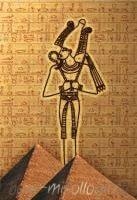

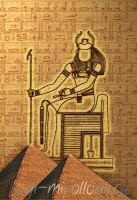

The air god Shu, assisted by other gods, holds up Nut, the sky, as Geb, the earth, lies beneath.

In Egyptian belief, the disorder that predates the ordered world exists beyond the world as an infinite expanse of formless water, personified by the god Nun. The earth, personified by the god Geb, is a flat piece of land over which arches the sky, usually represented by the goddess Nut. The two are separated by the personification of air, Shu. The sun god Ra is said to travel through the sky, across the body of Nut, enlivening the world with his light. At night Ra passes beyond the western horizon into the Duat, a mysterious region that borders the formlessness of Nun. At dawn he emerges from the Duat in the eastern horizon.[54]

The nature of the sky and the location of the Duat are uncertain. Egyptian texts variously describe the nighttime sun as traveling beneath the earth and within the body of Nut. The Egyptologist James P. Allen believes that these explanations of the sun’s movements are dissimilar but coexisting ideas. In Allen’s view, Nut represents the visible surface of the waters of Nun, with the stars floating on this surface. The sun, therefore, sails across the water in a circle, each night passing beyond the horizon to reach the skies that arch beneath the inverted land of the Duat.[55] Leonard H. Lesko, however, believes that the Egyptians saw the sky as a solid canopy and described the sun as traveling through the Duat above the surface of the sky, from west to east, during the night.[56] Joanne Conman, modifying Lesko’s model, argues that this solid sky is a moving, concave dome overarching a deeply convex earth. The sun and the stars move along with this dome, and their passage below the horizon is simply their movement over areas of the earth that the Egyptians could not see. These regions would then be the Duat.[57]

The fertile lands of the Nile Valley (Upper Egypt) and Delta (Lower Egypt) lie at the center of the world in Egyptian cosmology. Outside them are the infertile deserts, which are associated with the chaos that lies beyond the world.[58] Somewhere beyond them is the horizon, the akhet. There, two mountains, in the east and the west, mark the places where the sun enters and exits the Duat.[59]

Foreign nations are associated with the hostile deserts in Egyptian ideology. Foreign people, likewise, are generally lumped in with the «nine bows», people who threaten pharaonic rule and the stability of maat, although peoples allied with or subject to Egypt may be viewed more positively.[60] For these reasons, events in Egyptian mythology rarely take place in foreign lands. While some stories pertain to the sky or the Duat, Egypt itself is usually the scene for the actions of the gods. Often, even the myths set in Egypt seem to take place on a plane of existence separate from that inhabited by living humans, although in other stories, humans and gods interact. In either case, the Egyptian gods are deeply tied to their home land.[58]

Time[edit]

The Egyptians’ vision of time was influenced by their environment. Each day the sun rose and set, bringing light to the land and regulating human activity; each year the Nile flooded, renewing the fertility of the soil and allowing the highly productive agriculture that sustained Egyptian civilization. These periodic events inspired the Egyptians to see all of time as a series of recurring patterns regulated by maat, renewing the gods and the universe.[2] Although the Egyptians recognized that different historical eras differ in their particulars, mythic patterns dominate the Egyptian perception of history.[61]

Many Egyptian stories about the gods are characterized as having taken place in a primeval time when the gods were manifest on the earth and ruled over it. After this time, the Egyptians believed, authority on earth passed to human pharaohs.[62] This primeval era seems to predate the start of the sun’s journey and the recurring patterns of the present world. At the other end of time is the end of the cycles and the dissolution of the world. Because these distant periods lend themselves to linear narrative better than the cycles of the present, John Baines sees them as the only periods in which true myths take place.[63] Yet, to some extent, the cyclical aspect of time was present in the mythic past as well. Egyptians saw even stories that were set in that time as being perpetually true. The myths were made real every time the events to which they were related occurred. These events were celebrated with rituals, which often evoked myths.[64] Ritual allowed time to periodically return to the mythic past and renew life in the universe.[65]

Major myths[edit]

Some of the most important categories of myths are described below. Because of the fragmentary nature of Egyptian myths, there is little indication in Egyptian sources of a chronological sequence of mythical events.[66] Nevertheless, the categories are arranged in a very loose chronological order.

Creation[edit]

Among the most important myths were those describing the creation of the world. The Egyptians developed many accounts of the creation, which differ greatly in the events they describe. In particular, the deities credited with creating the world vary in each account. This difference partly reflects the desire of Egypt’s cities and priesthoods to exalt their own patron gods by attributing creation to them. Yet the differing accounts were not regarded as contradictory; instead, the Egyptians saw the creation process as having many aspects and involving many divine forces.[67]

The sun rises over the circular mound of creation as goddesses pour out the primeval waters around it

One common feature of the myths is the emergence of the world from the waters of chaos that surround it. This event represents the establishment of maat and the origin of life. One fragmentary tradition centers on the eight gods of the Ogdoad, who represent the characteristics of the primeval water itself. Their actions give rise to the sun (represented in creation myths by various gods, especially Ra), whose birth forms a space of light and dryness within the dark water.[68] The sun rises from the first mound of dry land, another common motif in the creation myths, which was likely inspired by the sight of mounds of earth emerging as the Nile flood receded. With the emergence of the sun god, the establisher of maat, the world has its first ruler.[69] Accounts from the first millennium BC focus on the actions of the creator god in subduing the forces of chaos that threaten the newly ordered world.[14]

Atum, a god closely connected with the sun and the primeval mound, is the focus of a creation myth dating back at least to the Old Kingdom. Atum, who incorporates all the elements of the world, exists within the waters as a potential being. At the time of creation he emerges to produce other gods, resulting in a set of nine deities, the Ennead, which includes Geb, Nut, and other key elements of the world. The Ennead can by extension stand for all the gods, so its creation represents the differentiation of Atum’s unified potential being into the multiplicity of elements present within the world.[70]

Over time, the Egyptians developed more abstract perspectives on the creation process. By the time of the Coffin Texts, they described the formation of the world as the realization of a concept first developed within the mind of the creator god. The force of heka, or magic, which links things in the divine realm and things in the physical world, is the power that links the creator’s original concept with its physical realization. Heka itself can be personified as a god, but this intellectual process of creation is not associated with that god alone. An inscription from the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–664 BC), whose text may be much older, describes the process in detail and attributes it to the god Ptah, whose close association with craftsmen makes him a suitable deity to give a physical form to the original creative vision. Hymns from the New Kingdom describe the god Amun, a mysterious power that lies behind even the other gods, as the ultimate source of this creative vision.[71]

The origin of humans is not a major feature of Egyptian creation stories. In some texts the first humans spring from tears that Ra-Atum or his feminine aspect, the Eye of Ra, sheds in a moment of weakness and distress, foreshadowing humans’ flawed nature and sorrowful lives. Others say humans are molded from clay by the god Khnum. But overall, the focus of the creation myths is the establishment of cosmic order rather than the special place of humans within it.[72]

The reign of the sun god[edit]

In the period of the mythic past after the creation, Ra dwells on earth as king of the gods and of humans. This period is the closest thing to a golden age in Egyptian tradition, the period of stability that the Egyptians constantly sought to evoke and imitate. Yet the stories about Ra’s reign focus on conflicts between him and forces that disrupt his rule, reflecting the king’s role in Egyptian ideology as enforcer of maat.[73]

In an episode known in different versions from temple texts, some of the gods defy Ra’s authority, and he destroys them with the help and advice of other gods like Thoth and Horus the Elder.[74][Note 2] At one point he faces dissent even from an extension of himself, the Eye of Ra, which can act independently of him in the form of a goddess. The Eye goddess becomes angry with Ra and runs away from him, wandering wild and dangerous in the lands outside Egypt. Weakened by her absence, Ra sends one of the other gods—Shu, Thoth, or Anhur, in different accounts—to retrieve her, by force or persuasion. Because the Eye of Ra is associated with the star Sothis, whose heliacal rising signaled the start of the Nile flood, the return of the Eye goddess to Egypt coincides with the life-giving inundation. Upon her return, the goddess becomes the consort of Ra or of the god who has retrieved her. Her pacification restores order and renews life.[76]

As Ra grows older and weaker, humanity, too, turns against him. In an episode often called «The Destruction of Mankind», related in The Book of the Heavenly Cow, Ra discovers that humanity is plotting rebellion against him and sends his Eye to punish them. She slays many people, but Ra apparently decides that he does not want her to destroy all of humanity. He has beer dyed red to resemble blood and spreads it over the field. The Eye goddess drinks the beer, becomes drunk, and ceases her rampage. Ra then withdraws into the sky, weary of ruling on earth, and begins his daily journey through the heavens and the Duat. The surviving humans are dismayed, and they attack the people among them who plotted against Ra. This event is the origin of warfare, death, and humans’ constant struggle to protect maat from the destructive actions of other people.[77]

In The Book of the Heavenly Cow, the results of the destruction of mankind seem to mark the end of the direct reign of the gods and of the linear time of myth. The beginning of Ra’s journey is the beginning of the cyclical time of the present.[63] Yet in other sources, mythic time continues after this change. Egyptian accounts give sequences of divine rulers who take the place of the sun god as king on earth, each reigning for many thousands of years.[78] Although accounts differ as to which gods reigned and in what order, the succession from Ra-Atum to his descendants Shu and Geb—in which the kingship passes to the male in each generation of the Ennead—is common. Both of them face revolts that parallel those in the reign of the sun god, but the revolt that receives the most attention in Egyptian sources is the one in the reign of Geb’s heir Osiris.[79]

Osiris myth[edit]

The collection of episodes surrounding Osiris’ death and succession is the most elaborate of all Egyptian myths, and it had the most widespread influence in Egyptian culture.[80] In the first portion of the myth, Osiris, who is associated with both fertility and kingship, is killed and his position usurped by his brother Set. In some versions of the myth, Osiris is actually dismembered and the pieces of his corpse scattered across Egypt. Osiris’ sister and wife, Isis, finds her husband’s body and restores it to wholeness.[81] She is assisted by funerary deities such as Nephthys and Anubis, and the process of Osiris’ restoration reflects Egyptian traditions of embalming and burial. Isis then briefly revives Osiris to conceive an heir with him: the god Horus.[82]

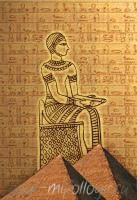

Statues of Osiris and of Isis nursing the infant Horus

The next portion of the myth concerns Horus’ birth and childhood. Isis gives birth to and raises her son in secluded places, hidden from the menace of Set. The episodes in this phase of the myth concern Isis’ efforts to protect her son from Set or other hostile beings, or to heal him from sickness or injury. In these episodes Isis is the epitome of maternal devotion and a powerful practitioner of healing magic.[83]

In the third phase of the story, Horus competes with Set for the kingship. Their struggle encompasses a great number of separate episodes and ranges in character from violent conflict to a legal judgment by the assembled gods.[84] In one important episode, Set tears out one or both of Horus’ eyes, which are later restored by the healing efforts of Thoth or Hathor. For this reason, the Eye of Horus is a prominent symbol of life and well-being in Egyptian iconography. Because Horus is a sky god, with one eye equated with the sun and the other with the moon, the destruction and restoration of the single eye explains why the moon is less bright than the sun.[85]

Texts present two different resolutions for the divine contest: one in which Egypt is divided between the two claimants, and another in which Horus becomes sole ruler. In the latter version, the ascension of Horus, Osiris’ rightful heir, symbolizes the reestablishment of maat after the unrighteous rule of Set. With order restored, Horus can perform the funerary rites for his father that are his duty as son and heir. Through this service Osiris is given new life in the Duat, whose ruler he becomes. The relationship between Osiris as king of the dead and Horus as king of the living stands for the relationship between every king and his deceased predecessors. Osiris, meanwhile, represents the regeneration of life. On earth he is credited with the annual growth of crops, and in the Duat he is involved in the rebirth of the sun and of deceased human souls.[86]

Although Horus to some extent represents any living pharaoh, he is not the end of the lineage of ruling gods. He is succeeded first by gods and then by spirits that represent dim memories of Egypt’s Predynastic rulers, the souls of Nekhen and Pe. They link the entirely mythical rulers to the final part of the sequence, the lineage of Egypt’s historical kings.[62]

Birth of the royal child[edit]

Several disparate Egyptian texts address a similar theme: the birth of a divinely fathered child who is heir to the kingship. The earliest known appearance of such a story does not appear to be a myth but an entertaining folktale, found in the Middle Kingdom Westcar Papyrus, about the birth of the first three kings of Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty. In that story, the three kings are the offspring of Ra and a human woman. The same theme appears in a firmly religious context in the New Kingdom, when the rulers Hatshepsut, Amenhotep III, and Ramesses II depicted in temple reliefs their own conception and birth, in which the god Amun is the father and the historical queen the mother. By stating that the king originated among the gods and was deliberately created by the most important god of the period, the story gives a mythical background to the king’s coronation, which appears alongside the birth story. The divine connection legitimizes the king’s rule and provides a rationale for his role as intercessor between gods and humans.[87]

Similar scenes appear in many post-New Kingdom temples, but this time the events they depict involve the gods alone. In this period, most temples were dedicated to a mythical family of deities, usually a father, mother, and son. In these versions of the story, the birth is that of the son in each triad.[88] Each of these child gods is the heir to the throne, who will restore stability to the country. This shift in focus from the human king to the gods who are associated with him reflects a decline in the status of the pharaoh in the late stages of Egyptian history.[87]

The journey of the sun[edit]

Ra’s movements through the sky and the Duat are not fully narrated in Egyptian sources,[89] although funerary texts like the Amduat, Book of Gates, and Book of Caverns relate the nighttime half of the journey in sequences of vignettes.[90] This journey is key to Ra’s nature and to the sustenance of all life.[30]

In traveling across the sky, Ra brings light to the earth, sustaining all things that live there. He reaches the peak of his strength at noon and then ages and weakens as he moves toward sunset. In the evening, Ra takes the form of Atum, the creator god, oldest of all things in the world. According to early Egyptian texts, at the end of the day he spits out all the other deities, whom he devoured at sunrise. Here they represent the stars, and the story explains why the stars are visible at night and seemingly absent during the day.[91]

At sunset Ra passes through the akhet, the horizon, in the west. At times the horizon is described as a gate or door that leads to the Duat. At others, the sky goddess Nut is said to swallow the sun god, so that his journey through the Duat is likened to a journey through her body.[92] In funerary texts, the Duat and the deities in it are portrayed in elaborate, detailed, and widely varying imagery. These images are symbolic of the awesome and enigmatic nature of the Duat, where both the gods and the dead are renewed by contact with the original powers of creation. Indeed, although Egyptian texts avoid saying it explicitly, Ra’s entry into the Duat is seen as his death.[93]

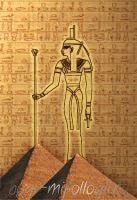

Ra (at center) travels through the underworld in his barque, accompanied by other gods[94]

Certain themes appear repeatedly in depictions of the journey. Ra overcomes numerous obstacles in his course, representative of the effort necessary to maintain maat. The greatest challenge is the opposition of Apep, a serpent god who represents the destructive aspect of disorder, and who threatens to destroy the sun god and plunge creation into chaos.[95] In many of the texts, Ra overcomes these obstacles with the assistance of other deities who travel with him; they stand for various powers that are necessary to uphold Ra’s authority.[96] In his passage Ra also brings light to the Duat, enlivening the blessed dead who dwell there. In contrast, his enemies—people who have undermined maat—are tormented and thrown into dark pits or lakes of fire.[97]

The key event in the journey is the meeting of Ra and Osiris. In the New Kingdom, this event developed into a complex symbol of the Egyptian conception of life and time. Osiris, relegated to the Duat, is like a mummified body within its tomb. Ra, endlessly moving, is like the ba, or soul, of a deceased human, which may travel during the day but must return to its body each night. When Ra and Osiris meet, they merge into a single being. Their pairing reflects the Egyptian vision of time as a continuous repeating pattern, with one member (Osiris) being always static and the other (Ra) living in a constant cycle. Once he has united with Osiris’ regenerative power, Ra continues on his journey with renewed vitality.[65] This renewal makes possible Ra’s emergence at dawn, which is seen as the rebirth of the sun—expressed by a metaphor in which Nut gives birth to Ra after she has swallowed him—and the repetition of the first sunrise at the moment of creation. At this moment, the rising sun god swallows the stars once more, absorbing their power.[91] In this revitalized state, Ra is depicted as a child or as the scarab beetle god Khepri, both of which represent rebirth in Egyptian iconography.[98]

End of the universe[edit]

Egyptian texts typically treat the dissolution of the world as a possibility to be avoided, and for that reason they do not often describe it in detail. However, many texts allude to the idea that the world, after countless cycles of renewal, is destined to end. This end is described in a passage in the Coffin Texts and a more explicit one in the Book of the Dead, in which Atum says that he will one day dissolve the ordered world and return to his primeval, inert state within the waters of chaos. All things other than the creator will cease to exist, except Osiris, who will survive along with him.[99] Details about this eschatological prospect are left unclear, including the fate of the dead who are associated with Osiris.[100] Yet with the creator god and the god of renewal together in the waters that gave rise to the orderly world, there is the potential for a new creation to arise in the same manner as the old.[101]

Influence in Egyptian culture[edit]

In religion[edit]

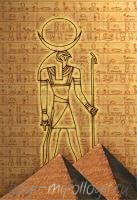

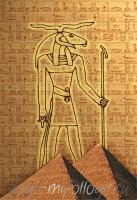

Set and Horus support the pharaoh. The reconciled rival gods often stand for the unity of Egypt under the rule of its king.[102]

Because the Egyptians rarely described theological ideas explicitly, the implicit ideas of mythology formed much of the basis for Egyptian religion. The purpose of Egyptian religion was the maintenance of maat, and the concepts that myths express were believed to be essential to maat. The rituals of Egyptian religion were meant to make the mythic events, and the concepts they represented, real once more, thereby renewing maat.[64] The rituals were believed to achieve this effect through the force of heka, the same connection between the physical and divine realms that enabled the original creation.[103]

For this reason, Egyptian rituals often included actions that symbolized mythical events.[64] Temple rites included the destruction of models representing malign gods like Set or Apophis, private magical spells called upon Isis to heal the sick as she did for Horus,[104] and funerary rites such as the Opening of the mouth ceremony[105] and ritual offerings to the dead evoked the myth of Osiris’ resurrection.[106] Yet rituals rarely, if ever, involved dramatic reenactments of myths. There are borderline cases, like a ceremony alluding to the Osiris myth in which two women took on the roles of Isis and Nephthys, but scholars disagree about whether these performances formed sequences of events.[107] Much of Egyptian ritual was focused on more basic activities like giving offerings to the gods, with mythic themes serving as ideological background rather than as the focus of a rite.[108] Nevertheless, myth and ritual strongly influenced each other. Myths could inspire rituals, like the ceremony with Isis and Nephthys; and rituals that did not originally have a mythic meaning could be reinterpreted as having one, as in the case of offering ceremonies, in which food and other items given to the gods or the dead were equated with the Eye of Horus.[109]

Kingship was a key element of Egyptian religion, through the king’s role as link between humanity and the gods. Myths explain the background for this connection between royalty and divinity. The myths about the Ennead establish the king as heir to the lineage of rulers reaching back to the creator; the myth of divine birth states that the king is the son and heir of a god; and the myths about Osiris and Horus emphasize that rightful succession to the throne is essential to the maintenance of maat. Thus, mythology provided the rationale for the very nature of Egyptian government.[110]

In art[edit]

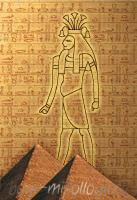

Funerary amulet in the shape of a scarab

Illustrations of gods and mythical events appear extensively alongside religious writing in tombs, temples, and funerary texts.[42] Mythological scenes in Egyptian artwork are rarely placed in sequence as a narrative, but individual scenes, particularly depicting the resurrection of Osiris, do sometimes appear in religious artwork.[111]

Allusions to myth were very widespread in Egyptian art and architecture. In temple design, the central path of the temple axis was likened to the sun god’s path across the sky, and the sanctuary at the end of the path represented the place of creation from which he rose. Temple decoration was filled with solar emblems that underscored this relationship. Similarly, the corridors of tombs were linked with the god’s journey through the Duat, and the burial chamber with the tomb of Osiris.[112] The pyramid, the best-known of all Egyptian architectural forms, may have been inspired by mythic symbolism, for it represented the mound of creation and the original sunrise, appropriate for a monument intended to assure the owner’s rebirth after death.[113] Symbols in Egyptian tradition were frequently reinterpreted, so that the meanings of mythical symbols could change and multiply over time like the myths themselves.[114]

More ordinary works of art were also designed to evoke mythic themes, like the amulets that Egyptians commonly wore to invoke divine powers. The Eye of Horus, for instance, was a very common shape for protective amulets because it represented Horus’ well-being after the restoration of his lost eye.[115] Scarab-shaped amulets symbolized the regeneration of life, referring to the god Khepri, the form that the sun god was said to take at dawn.[116]

In literature[edit]

Themes and motifs from mythology appear frequently in Egyptian literature, even outside of religious writings. An early instruction text, the «Teaching for King Merykara» from the Middle Kingdom, contains a brief reference to a myth of some kind, possibly the Destruction of Mankind; the earliest known Egyptian short story, «Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor», incorporates ideas about the gods and the eventual dissolution of the world into a story set in the past. Some later stories take much of their plot from mythical events: «Tale of the Two Brothers» adapts parts of the Osiris myth into a fantastic story about ordinary people, and «The Blinding of Truth by Falsehood» transforms the conflict between Horus and Set into an allegory.[117]

A fragment of a text about the actions of Horus and Set dates to the Middle Kingdom, suggesting that stories about the gods arose in that era. Several texts of this type are known from the New Kingdom, and many more were written in the Late and Greco-Roman periods. Although these texts are more clearly derived from myth than those mentioned above, they still adapt the myths for non-religious purposes. «The Contendings of Horus and Seth», from the New Kingdom, tells the story of the conflict between the two gods, often with a humorous and seemingly irreverent tone. The Roman-era «Myth of the Eye of the Sun» incorporates fables into a framing story taken from myth. The goals of written fiction could also affect the narratives in magical texts, as with the New Kingdom story «Isis, the Rich Woman’s Son, and the Fisherman’s Wife», which conveys a moral message unconnected to its magical purpose. The variety of ways that these stories treat mythology demonstrates the wide range of purposes that myth could serve in Egyptian culture.[118]

See also[edit]

- Index of Egyptian mythology articles

- Kemetism

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Horus and Set, portrayed together, often stand for the pairing of Upper and Lower Egypt, although either god can stand for either region. Both of them were patrons of cities in both halves of the country. The conflict between the two deities may allude to the presumed conflict that preceded the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt at the start of Egyptian history, or it may be tied to an apparent conflict between worshippers of Horus and Set near the end of the Second Dynasty.[13]

- ^ Horus the Elder is often treated as a separate deity from Horus, the child born to Isis.[75]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Anthes 1961, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b David 2002, pp. 1–2.

- ^ O’Connor 2003, pp. 155, 178–179.

- ^ Tobin 1989, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c Morenz 1973, pp. 81–84.

- ^ a b Baines 1991, p. 83.

- ^ Frankfurter 1995, pp. 472–474.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 113, 115, 119–122.

- ^ Griffiths 2001, pp. 188–190.

- ^ Anthes 1961, pp. 33–36.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Meltzer 2001, pp. 119–122.

- ^ a b Bickel 2004, p. 580.

- ^ Assmann 2001, p. 116.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Baines 1996, p. 361.

- ^ Baines 1991, pp. 81–85, 104.

- ^ a b Tobin 2001, pp. 464–468.

- ^ a b c Bickel 2004, p. 578.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 107–112.

- ^ a b Tobin 1989, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c d e f Baines 1991, pp. 100–104.

- ^ Baines 1991, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Anthes 1961, pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b c Tobin 1989, pp. 18, 23–26.

- ^ Assmann 2001, p. 117.

- ^ a b Tobin 1989, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Assmann 2001, p. 112.

- ^ Hornung 1992, pp. 41–45, 96.

- ^ Vischak 2001, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Anthes 1961, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Allen 1988, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Traunecker 2001, pp. 101–103.

- ^ David 2002, pp. 28, 84–85.

- ^ Anthes 1961, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Allen 1988, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Tobin 1989, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Traunecker 2001, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c Traunecker 2001, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Bickel 2004, p. 379.

- ^ Baines 1991, pp. 84, 90.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 6–11.

- ^ Morenz 1973, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Ritner 1993, pp. 243–249.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 6.

- ^ a b Baines 1996, pp. 365–376.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 35, 39–42.

- ^ Tobin 1989, pp. 79–82, 197–199.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 156.

- ^ Allen 1988, pp. 3–7.

- ^ Allen 2003, pp. 25–29.

- ^ Lesko 1991, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Conman 2003, pp. 33–37.

- ^ a b Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 82–88, 91.

- ^ Lurker 1980, pp. 64–65, 82.

- ^ O’Connor 2003, pp. 155–156, 169–171.

- ^ Hornung 1992, pp. 151–154.

- ^ a b Pinch 2002, p. 85.

- ^ a b Baines 1996, pp. 364–365.

- ^ a b c Tobin 1989, pp. 27–31.

- ^ a b Assmann 2001, pp. 77–80.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 57.

- ^ David 2002, pp. 81, 89.

- ^ Dunand & Zivie-Coche 2004, pp. 45–50.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 19–21.

- ^ Allen 1988, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Allen 1988, pp. 36–42, 60.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 143.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 71–74.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 113–116.

- ^ Uphill 2003, pp. 17–26.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 76–78.

- ^ Assmann 2001, p. 124.

- ^ Hart 1990, pp. 30–33.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 131–134.

- ^ Hart 1990, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Kaper 2001, pp. 480–482.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 129, 141–145.

- ^ a b Assmann 2001, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Feucht 2001, p. 193.

- ^ Baines 1996, p. 364.

- ^ Hornung 1992, p. 96.

- ^ a b Pinch 2002, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Hornung 1992, pp. 96–97, 113.

- ^ Tobin 1989, pp. 49, 136–138.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Hart 1990, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Quirke 2001, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Hornung 1992, pp. 95, 99–101.

- ^ Hart 1990, pp. 57, 61.

- ^ Hornung 1982, pp. 162–165.

- ^ Dunand & Zivie-Coche 2004, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Meeks & Favard-Meeks 1996, pp. 18–19.

- ^ te Velde 2001, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Ritner 1993, pp. 246–249.

- ^ Ritner 1993, p. 150.

- ^ Roth 2001, pp. 605–608.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 49–51.

- ^ O’Rourke 2001, pp. 407–409.

- ^ Baines 1991, p. 101.

- ^ Morenz 1973, p. 84.

- ^ Tobin 1989, pp. 90–95.

- ^ Baines 1991, p. 103.

- ^ Wilkinson 1993, pp. 27–29, 69–70.

- ^ Quirke 2001, p. 115.

- ^ Wilkinson 1993, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Andrews 2001, pp. 75–82.

- ^ Lurker 1980, pp. 74, 104–105.

- ^ Baines 1996, pp. 367–369, 373–374.

- ^ Baines 1996, pp. 366, 371–373, 377.

Works cited[edit]

- Allen, James P. (1988). Genesis in Egypt: The Philosophy of Ancient Egyptian Creation Accounts. Yale Egyptological Seminar. ISBN 0-912532-14-9.

- Allen, James P. (2003). «The Egyptian Concept of the World». In O’Connor, David; Quirke, Stephen (eds.). Mysterious Lands. UCL Press. pp. 23–30. ISBN 1-84472-004-7.

- Andrews, Carol A. R. (2001). «Amulets». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 75–82. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Anthes, Rudolf (1961). «Mythology in Ancient Egypt». In Kramer, Samuel Noah (ed.). Mythologies of the Ancient World. Anchor Books. pp. 16–92.

- Assmann, Jan (2001) [German edition 1984]. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3786-5.

- Baines, John (April 1991). «Egyptian Myth and Discourse: Myth, Gods, and the Early Written and Iconographic Record». Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 50 (2): 81–105. doi:10.1086/373483. JSTOR 545669. S2CID 162233011.

- Baines, John (1996). «Myth and Literature». In Loprieno, Antonio (ed.). Ancient Egyptian Literature: History and Forms. Cornell University Press. pp. 361–377. ISBN 90-04-09925-5.

- Bickel, Susanne (2004). «Myth and Sacred Narratives: Egypt». In Johnston, Sarah Iles (ed.). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 578–580. ISBN 0-674-01517-7.

- Conman, Joanne (2003). «It’s About Time: Ancient Egyptian Cosmology». Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 31.

- David, Rosalie (2002). Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-026252-0.

- Dunand, Françoise; Zivie-Coche, Christiane (2004) [French edition 1991]. Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8853-2.

- Feucht, Erika (2001). «Birth». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 192–193. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Frankfurter, David (1995). «Narrating Power: The Theory and Practice of the Magical Historiola in Ritual Spells». In Meyer, Marvin; Mirecki, Paul (eds.). Ancient Magic and Ritual Power. E. J. Brill. pp. 457–476. ISBN 0-8014-2550-6.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn (2001). «Isis». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 188–191. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Hart, George (1990). Egyptian Myths. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-72076-9.

- Hornung, Erik (1982) [German edition 1971]. Conceptions of God in Egypt: The One and the Many. Translated by John Baines. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-1223-4.

- Hornung, Erik (1992). Idea into Image: Essays on Ancient Egyptian Thought. Translated by Elizabeth Bredeck. Timken. ISBN 0-943221-11-0.

- Kaper, Olaf E. (2001). «Myths: Lunar Cycle». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 480–482. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Lesko, Leonard H. (1991). «Ancient Egyptian Cosmogonies and Cosmology». In Shafer, Byron E. (ed.). Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths, and Personal Practice. Cornell University Press. pp. 89–122. ISBN 0-8014-2550-6.

- Lurker, Manfred (1980) [German edition 1972]. An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Barbara Cummings. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27253-0.

- Meeks, Dimitri; Favard-Meeks, Christine (1996) [French edition 1993]. Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods. Translated by G. M. Goshgarian. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8248-8.

- Meltzer, Edmund S. (2001). «Horus». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 119–122. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Morenz, Siegfried (1973) [German edition 1960]. Egyptian Religion. Translated by Ann E. Keep. Methuen. ISBN 0-8014-8029-9.

- O’Connor, David (2003). «Egypt’s View of ‘Others’«. In Tait, John (ed.). ‘Never Had the Like Occurred’: Egypt’s View of Its Past. UCL Press. pp. 155–185. ISBN 978-1-84472-007-1.

- O’Rourke, Paul F. (2001). «Drama». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 407–410. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517024-5.

- Quirke, Stephen (2001). The Cult of Ra: Sun Worship in Ancient Egypt. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05107-0.

- Ritner, Robert Kriech (1993). The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN 0-918986-75-3.

- Roth, Ann Macy (2001). «Opening of the Mouth». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 605–609. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- te Velde, Herman (2001). «Seth». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. pp. 269–271. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Tobin, Vincent Arieh (1989). Theological Principles of Egyptian Religion. P. Lang. ISBN 0-8204-1082-9.

- Tobin, Vincent Arieh (2001). «Myths: An Overview». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 464–469. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Traunecker, Claude (2001) [French edition 1992]. The Gods of Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3834-9.

- Uphill, E. P. (2003). «The Ancient Egyptian View of World History». In Tait, John (ed.). ‘Never Had the Like Occurred’: Egypt’s View of Its Past. UCL Press. pp. 15–29. ISBN 978-1-84472-007-1.

- Vischak, Deborah (2001). «Hathor». In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 82–85. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (1993). Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-23663-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Armour, Robert A (2001) [1986]. Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 977-424-669-1.

- Ions, Veronica (1982) [1968]. Egyptian Mythology. Peter Bedrick Books. ISBN 0-911745-07-6.

- James, T. G. H (1971). Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt. Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 0-448-00866-1.

- Shaw, Garry J. (2014). The Egyptian Myths: A Guide to the Ancient Gods and Legends. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-25198-0.

- Sternberg, Heike (1985). Mythische Motive and Mythenbildung in den agyptischen Tempeln und Papyri der Griechisch-Romischen Zeit (in German). Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-02497-6.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2010). Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt. Allen Lanes. ISBN 978-1-84614-369-4.

Nun, the embodiment of the primordial waters, lifts the barque of the sun god Ra into the sky at the moment of creation.

Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the world around them. The beliefs that these myths express are an important part of ancient Egyptian religion. Myths appear frequently in Egyptian writings and art, particularly in short stories and in religious material such as hymns, ritual texts, funerary texts, and temple decoration. These sources rarely contain a complete account of a myth and often describe only brief fragments.

Inspired by the cycles of nature, the Egyptians saw time in the present as a series of recurring patterns, whereas the earliest periods of time were linear. Myths are set in these earliest times, and myth sets the pattern for the cycles of the present. Present events repeat the events of myth, and in doing so renew maat, the fundamental order of the universe. Amongst the most important episodes from the mythic past are the creation myths, in which the gods form the universe out of primordial chaos; the stories of the reign of the sun god Ra upon the earth; and the Osiris myth, concerning the struggles of the gods Osiris, Isis, and Horus against the disruptive god Set. Events from the present that might be regarded as myths include Ra’s daily journey through the world and its otherworldly counterpart, the Duat. Recurring themes in these mythic episodes include the conflict between the upholders of maat and the forces of disorder, the importance of the pharaoh in maintaining maat, and the continual death and regeneration of the gods.

The details of these sacred events differ greatly from one text to another and often seem contradictory. Egyptian myths are primarily metaphorical, translating the essence and behavior of deities into terms that humans can understand. Each variant of a myth represents a different symbolic perspective, enriching the Egyptians’ understanding of the gods and the world.

Mythology profoundly influenced Egyptian culture. It inspired or influenced many religious rituals and provided the ideological basis for kingship. Scenes and symbols from myth appeared in art in tombs, temples, and amulets. In literature, myths or elements of them were used in stories that range from humor to allegory, demonstrating that the Egyptians adapted mythology to serve a wide variety of purposes.

Origins[edit]

The development of Egyptian myth is difficult to trace. Egyptologists must make educated guesses about its earliest phases, based on written sources that appeared much later.[1] One obvious influence on myth is the Egyptians’ natural surroundings. Each day the sun rose and set, bringing light to the land and regulating human activity; each year the Nile flooded, renewing the fertility of the soil and allowing the highly productive farming that sustained Egyptian civilization. Thus the Egyptians saw water and the sun as symbols of life and thought of time as a series of natural cycles. This orderly pattern was at constant risk of disruption: unusually low floods resulted in famine, and high floods destroyed crops and buildings.[2] The hospitable Nile valley was surrounded by harsh desert, populated by peoples the Egyptians regarded as uncivilized enemies of order.[3] For these reasons, the Egyptians saw their land as an isolated place of stability, or maat, surrounded and endangered by chaos. These themes—order, chaos, and renewal—appear repeatedly in Egyptian religious thought.[4]

Another possible source for mythology is ritual. Many rituals make reference to myths and are sometimes based directly on them.[5] But it is difficult to determine whether a culture’s myths developed before rituals or vice versa.[6] Questions about this relationship between myth and ritual have spawned much discussion among Egyptologists and scholars of comparative religion in general. In ancient Egypt, the earliest evidence of religious practices predates written myths.[5] Rituals early in Egyptian history included only a few motifs from myth. For these reasons, some scholars have argued that, in Egypt, rituals emerged before myths.[6] But because the early evidence is so sparse, the question may never be resolved for certain.[5]

In private rituals, which are often called «magical», the myth and the ritual are particularly closely tied. Many of the myth-like stories that appear in the rituals’ texts are not found in other sources. Even the widespread motif of the goddess Isis rescuing her poisoned son Horus appears only in this type of text. The Egyptologist David Frankfurter argues that these rituals adapt basic mythic traditions to fit the specific ritual, creating elaborate new stories (called historiolas) based on myth.[7] In contrast, J. F. Borghouts says of magical texts that there is «not a shred of evidence that a specific kind of ‘unorthodox’ mythology was coined… for this genre.»[8]

Much of Egyptian mythology consists of origin myths, explaining the beginnings of various elements of the world, including human institutions and natural phenomena. Kingship arises among the gods at the beginning of time and later passed to the human pharaohs; warfare originates when humans begin fighting each other after the sun god’s withdrawal into the sky.[9] Myths also describe the supposed beginnings of less fundamental traditions. In a minor mythic episode, Horus becomes angry with his mother Isis and cuts off her head. Isis replaces her lost head with that of a cow. This event explains why Isis was sometimes depicted with the horns of a cow as part of her headdress.[10]

Some myths may have been inspired by historical events. The unification of Egypt under the pharaohs, at the end of the Predynastic Period around 3100 BC, made the king the focus of Egyptian religion, and thus the ideology of kingship became an important part of mythology.[11] In the wake of unification, gods that were once local patron deities gained national importance, forming new relationships that linked the local deities into a unified national tradition. Geraldine Pinch suggests that early myths may have formed from these relationships.[12] Egyptian sources link the mythical strife between the gods Horus and Set with a conflict between the regions of Upper and Lower Egypt, which may have happened in the late Predynastic era or in the Early Dynastic Period.[13][Note 1]

After these early times, most changes to mythology developed and adapted preexisting concepts rather than creating new ones, although there were exceptions.[14] Many scholars have suggested that the myth of the sun god withdrawing into the sky, leaving humans to fight among themselves, was inspired by the breakdown of royal authority and national unity at the end of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – 2181 BC).[15] In the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC), minor myths developed around deities like Yam and Anat who had been adopted from Canaanite religion. In contrast, during the Greek and Roman eras (332 BC–641 AD), Greco-Roman culture had little influence on Egyptian mythology.[16]

Definition and scope[edit]

Scholars have difficulty defining which ancient Egyptian beliefs are myths. The basic definition of myth suggested by the Egyptologist John Baines is «a sacred or culturally central narrative». In Egypt, the narratives that are central to culture and religion are almost entirely about events among the gods.[17] Actual narratives about the gods’ actions are rare in Egyptian texts, particularly from early periods, and most references to such events are mere mentions or allusions. Some Egyptologists, like Baines, argue that narratives complete enough to be called «myths» existed in all periods, but that Egyptian tradition did not favor writing them down. Others, like Jan Assmann, have said that true myths were rare in Egypt and may only have emerged partway through its history, developing out of the fragments of narration that appear in the earliest writings.[18] Recently, however, Vincent Arieh Tobin[19] and Susanne Bickel have suggested that lengthy narration was not needed in Egyptian mythology because of its complex and flexible nature.[20] Tobin argues that narrative is even alien to myth, because narratives tend to form a simple and fixed perspective on the events they describe. If narration is not needed for myth, any statement that conveys an idea about the nature or actions of a god can be called «mythic».[19]

Content and meaning[edit]

Like myths in many other cultures, Egyptian myths serve to justify human traditions and to address fundamental questions about the world,[21] such as the nature of disorder and the ultimate fate of the universe.[20] The Egyptians explained these profound issues through statements about the gods.[20]

Egyptian deities represent natural phenomena, from physical objects like the earth or the sun to abstract forces like knowledge and creativity. The actions and interactions of the gods, the Egyptians believed, govern the behavior of all of these forces and elements.[22] For the most part, the Egyptians did not describe these mysterious processes in explicit theological writings. Instead, the relationships and interactions of the gods illustrated such processes implicitly.[23]

Most of Egypt’s gods, including many of the major ones, do not have significant roles in any mythic narratives,[24] although their nature and relationships with other deities are often established in lists or bare statements without narration.[25] For the gods who are deeply involved in narratives, mythic events are very important expressions of their roles in the cosmos. Therefore, if only narratives are myths, mythology is a major element in Egyptian religious understanding, but not as essential as it is in many other cultures.[26]

The sky depicted as a cow goddess supported by other deities. This image combines several coexisting visions of the sky: as a roof, as the surface of a sea, as a cow, and as a goddess in human form.[27]

The true realm of the gods is mysterious and inaccessible to humans. Mythological stories use symbolism to make the events in this realm comprehensible.[28] Not every detail of a mythic account has symbolic significance. Some images and incidents, even in religious texts, are meant simply as visual or dramatic embellishments of broader, more meaningful myths.[29][30]

Few complete stories appear in Egyptian mythological sources. These sources often contain nothing more than allusions to the events to which they relate, and texts that contain actual narratives tell only portions of a larger story. Thus, for any given myth the Egyptians may have had only the general outlines of a story, from which fragments describing particular incidents were drawn.[24] Moreover, the gods are not well-defined characters, and the motivations for their sometimes inconsistent actions are rarely given.[31] Egyptian myths are not, therefore, fully developed tales. Their importance lay in their underlying meaning, not their characteristics as stories. Instead of coalescing into lengthy, fixed narratives, they remained highly flexible and non-dogmatic.[28]

So flexible were Egyptian myths that they could seemingly conflict with each other. Many descriptions of the creation of the world and the movements of the sun occur in Egyptian texts, some very different from each other.[32] The relationships between gods were fluid, so that, for instance, the goddess Hathor could be called the mother, wife, or daughter of the sun god Ra.[33] Separate deities could even be syncretized, or linked, as a single being. Thus the creator god Atum was combined with Ra to form Ra-Atum.[34]

One commonly suggested reason for inconsistencies in myth is that religious ideas differed over time and in different regions.[35] The local cults of various deities developed theologies centered on their own patron gods.[36] As the influence of different cults shifted, some mythological systems attained national dominance. In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC) the most important of these systems was the cults of Ra and Atum, centered at Heliopolis. They formed a mythical family, the Ennead, that was said to have created the world. It included the most important deities of the time but gave primacy to Atum and Ra.[37] The Egyptians also overlaid old religious ideas with new ones. For instance, the god Ptah, whose cult was centered at Memphis, was also said to be the creator of the world. Ptah’s creation myth incorporates older myths by saying that it is the Ennead who carry out Ptah’s creative commands.[38] Thus, the myth makes Ptah older and greater than the Ennead. Many scholars have seen this myth as a political attempt to assert the superiority of Memphis’ god over those of Heliopolis.[39] By combining concepts in this way, the Egyptians produced an immensely complicated set of deities and myths.[40]

Egyptologists in the early twentieth century thought that politically motivated changes like these were the principal reason for the contradictory imagery in Egyptian myth. However, in the 1940s, Henri Frankfort, realizing the symbolic nature of Egyptian mythology, argued that apparently contradictory ideas are part of the «multiplicity of approaches» that the Egyptians used to understand the divine realm. Frankfort’s arguments are the basis for much of the more recent analysis of Egyptian beliefs.[41] Political changes affected Egyptian beliefs, but the ideas that emerged through those changes also have deeper meaning. Multiple versions of the same myth express different aspects of the same phenomenon; different gods that behave in a similar way reflect the close connections between natural forces. The varying symbols of Egyptian mythology express ideas too complex to be seen through a single lens.[28]

Sources[edit]

The sources that are available range from solemn hymns to entertaining stories. Without a single, canonical version of any myth, the Egyptians adapted the broad traditions of myth to fit the varied purposes of their writings.[42] Most Egyptians were illiterate and may therefore have had an elaborate oral tradition that transmitted myths through spoken storytelling. Susanne Bickel suggests that the existence of this tradition helps explain why many texts related to myth give little detail: the myths were already known to every Egyptian.[43] Very little evidence of this oral tradition has survived, and modern knowledge of Egyptian myths is drawn from written and pictorial sources. Only a small proportion of these sources has survived to the present, so much of the mythological information that was once written down has been lost.[25] This information is not equally abundant in all periods, so the beliefs that Egyptians held in some eras of their history are more poorly understood than the beliefs in better documented times.[44]

Religious sources[edit]

Many gods appear in artwork from the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt’s history (c. 3100–2686 BC), but little about the gods’ actions can be gleaned from these sources because they include minimal writing. The Egyptians began using writing more extensively in the Old Kingdom, in which appeared the first major source of Egyptian mythology: the Pyramid Texts. These texts are a collection of several hundred incantations inscribed in the interiors of pyramids beginning in the 24th century BC. They were the first Egyptian funerary texts, intended to ensure that the kings buried in the pyramid would pass safely through the afterlife. Many of the incantations allude to myths related to the afterlife, including creation myths and the myth of Osiris. Many of the texts are likely much older than their first known written copies, and they therefore provide clues about the early stages of Egyptian religious belief.[45]

During the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), the Pyramid Texts developed into the Coffin Texts, which contain similar material and were available to non-royals. Succeeding funerary texts, like the Book of the Dead in the New Kingdom and the Books of Breathing from the Late Period (664–323 BC) and after, developed out of these earlier collections. The New Kingdom also saw the development of another type of funerary text, containing detailed and cohesive descriptions of the nocturnal journey of the sun god. Texts of this type include the Amduat, the Book of Gates, and the Book of Caverns.[42]

Temple decoration at Dendera, depicting the goddesses Isis and Nephthys watching over the corpse of their brother Osiris

Temples, whose surviving remains date mostly from the New Kingdom and later, are another important source of myth. Many temples had a per-ankh, or temple library, storing papyri for rituals and other uses. Some of these papyri contain hymns, which, in praising a god for its actions, often refer to the myths that define those actions. Other temple papyri describe rituals, many of which are based partly on myth.[46] Scattered remnants of these papyrus collections have survived to the present. It is possible that the collections included more systematic records of myths, but no evidence of such texts has survived.[25] Mythological texts and illustrations, similar to those on temple papyri, also appear in the decoration of the temple buildings. The elaborately decorated and well-preserved temples of the Ptolemaic and Roman periods (305 BC–AD 380) are an especially rich source of myth.[47]

The Egyptians also performed rituals for personal goals such as protection from or healing of illness. These rituals are often called «magical» rather than religious, but they were believed to work on the same principles as temple ceremonies, evoking mythical events as the basis for the ritual.[48]

Information from religious sources is limited by a system of traditional restrictions on what they could describe and depict. The murder of the god Osiris, for instance, is never explicitly described in Egyptian writings.[25] The Egyptians believed that words and images could affect reality, so they avoided the risk of making such negative events real.[49] The conventions of Egyptian art were also poorly suited for portraying whole narratives, so most myth-related artwork consists of sparse individual scenes.[25]

Other sources[edit]

References to myth also appear in non-religious Egyptian literature, beginning in the Middle Kingdom. Many of these references are mere allusions to mythic motifs, but several stories are based entirely on mythic narratives. These more direct renderings of myth are particularly common in the Late and Greco-Roman periods when, according to scholars such as Heike Sternberg, Egyptian myths reached their most fully developed state.[50]

The attitudes toward myth in nonreligious Egyptian texts vary greatly. Some stories resemble the narratives from magical texts, while others are more clearly meant as entertainment and even contain humorous episodes.[50]