Жуть. Оригиналы известных сказок

Автор:

09 сентября 2015 19:44

Что скрывают знаменитые детские сказки

Мы привыкли к тому, что сказки — это для сопливых детишек. Однако, когда-то давно, веке в XVI, сказки были вполне взрослым развлечением.

Гензель и Гретель

Еще один небезызвестный сказочный сюжет, повествующий о брате и сестре, которые попадают в лапы к ведьме-каннибалу, живущей в лесном доме, построенном из сладостей.

От первого до последнего слова в этой сказке веет ужасом. Во-первых, фигура отца, отправляющего родных детей в лес на верную погибель под давлением своей жены, мачехи Гензеля и Гретель. Во-вторых, образ старухи, заставляющей сестру откармливать своего брата. В-третьих, сами дети. В этой сказке они не являются жертвами в традиционном понимании этого слова: брат и сестра оказываются весьма находчивыми малышами, а в жестокости отчасти не уступают своей тюремщице. Гретель обманом заманивает ведьму в печь и дотла сжигает ее. После этого дети грабят дом старухи. Они возвращаются к отцу и на вырученные от награбленного деньги живут в достатке.

Кстати, по сюжету к моменту из возвращения в отчий дом мачеха по неизвестной причине умирает. Исследователи полагают, что это свидетельствует о том, что по своей сути мачеха и ведьма — одна и та же женщина

Красная шапочка

История о девочке и голодном волке известна в Европе с XIV века. Содержимое корзинки менялось в зависимости от местности, а вот сама история была гораздо более неудачной для Красной шапочки. Убив бабушку, волк не просто ее съедает, а готовит из ее тела вкусняшку, а из крови — некий напиток. Спрятавшись в кровати, он наблюдает, так Красная Шапочка с аппетитом уплетает свою же бабушку. Предупредить девочку пытается бабушкина кошка, но и она умирает страшной смертью (волк бросает в нее тяжелые деревянные башмаки). Красную Шапочку это, по-видимому, не смущает, и после сытного обеда она послушно раздевается и ложится в кровать, где ее поджидает волк. В большинстве версий на этом все заканчивается — мол, поделом глупой девчонке!

Впоследствии Шарль Перро сочинил для этой истории оптимистичный финал и добавил мораль для всех, кого всякие незнакомцы зазывают к себе в кровать:

(А уж особенно девицам,

Красавицам и баловницам),

В пути встречая всяческих мужчин,

Нельзя речей коварных слушать, —

Иначе волк их может скушать.

Сказал я: волк! Волков не счесть,

Но между ними есть иные

Плуты, настолько продувные,

Что, сладко источая лесть,

Девичью охраняют честь,

Сопутствуют до дома их прогулкам,

Проводят их бай-бай по темным закоулкам…

Но волк, увы, чем кажется скромней,

Тем он всегда лукавей и страшней!

Спящая красавица

Современная версия о поцелуе, разбудившем красавицу, — просто детский лепет по сравнению с оригинальным сюжетом, который записал для потомков все тот же Джамбаттиста Базиле. Красавицу из его сказки по имени Талия тоже настигло проклятье в виде укола веретена, после которого принцесса заснула беспробудным сном. Безутешный король-отец оставил в маленьком домике в лесу, но никак не мог предположить, что произойдет дальше. Спустя годы мимо проезжал еще один король, зашел в домик и увидел Спящую Красавицу. Недолго думая, он перенес ее на постель и, так сказать, воспользовался ситуацией, а потом уехал и забыл обо всем на долгое время. А изнасилованная во сне красавица через девять месяцев родила близнецов — сына по имени Солнце и дочку Луну. Именно они разбудили Талию: мальчик в поисках материнской груди принялся сосать ее палец и случайно высосал отравленный шип. Дальше — больше. Похотливый король снова приехал в заброшенный домик и обнаружил там потомство.

Пообещал девушке золотые горы и вновь уехал в свое королевство, где его, между прочим, ждала законная жена. Супруга короля, узнав о разлучнице, решила ее истребить вместе со всем выводком и заодно наказать неверного мужа. Она приказала убить малышей и приготовить из них мясные пироги для короля, а принцессу — сжечь. Уже перед самым огнем крики красавицы услышал король, который прибежал и сжег не ее, а надоевшую злобную королеву. И напоследок хорошая новость: близнецов не съели, потому что повар оказался нормальным человеком и спас детишек, заменив их ягненком.

Защитник девичьей чести Шарль Перро, конечно, сказку сильно изменил, но не удержался от «морали» в конце истории. Его напутствие гласит:

Немножко обождать,

Чтоб подвернулся муж,

Красавец и богач к тому ж,

Вполне возможно и понятно.

Но сотню долгих лет,

В постели лежа, ждать

Для дам настолько неприятно,

Что ни одна не сможет спать….

Белоснежка

Сказку про Белоснежку братья Гримм наводнили интересными деталями, которые в наше гуманное время кажутся дикими. Первая версия была опубликована в 1812 году, в 1854 году дополнена. Начало сказки уже не предвещает ничего хорошего: «В один зимний снежный день королева сидит и шьёт у окна с рамой из чёрного дерева. Случайно она колет иголкой палец, роняет три капли крови и думает: „Ах, если бы у меня родился ребёночек, белый как снег, румяный как кровь и чернявый как чёрное дерево“». Но по-настоящему жуткой здесь предстает колдунья: она ест (как сама думает) сердце убитой Белоснежки, а потом, поняв, что ошиблась, придумывает все новые изощренные способы ее убить. В их числе — удушающий шнурок для платья, ядовитый гребень и отравленное яблоко, которое, как мы знаем, подействовало. Интересен и финал: когда все становится хорошо у Белоснежки, приходит черед колдуньи. В наказание за свои грехи она пляшет в раскаленных железных башмаках, до тех пор, пока не падает замертво.

Золушка

Считается, что самый ранний вариант «Золушки» придумали в Древнем Египте: пока прекрасная проститутка Фодорис купалась в реке, орёл украл её сандалию и унес фараону, который восхитился маленьким размером обуви и в итоге на блуднице женился.

У итальянца Джамбаттиста Базиле, записавшего сборник народных легенд «Сказка сказок», все гораздо хуже. Его Золушка, точнее Зезолла, вовсе не та несчастная девочка, которую мы знаем по диснеевским мультикам и детским спектаклям. Терпеть унижения от мачехи ей не хотелось, поэтому она крышкой сундука сломала мачехе шею, взяв в сообщницы свою няню. Няня тут же подсуетилась и стала для девушки второй мачехой, вдобавок у нее оказалось шесть злобных дочерей, перебить всех девушке, конечно, не светило. Спас случай: однажды девушку увидел король и влюбился. Зезоллу быстро нашли слуги Его величества, но она сумела сбежать, обронив — нет, не хрустальную туфельку! — грубую пианеллу с подошвой из пробки, какие носили женщины Неаполя. Дальнейшая схема ясна: общенациональный розыск и свадьба. Так убийца мачехи стала королевой.

Спустя 61 год после итальянской версии свою сказку выпустил Шарль Перро. Именно она стала основой для всех «ванильных» современных интерпретаций. Правда, в версии Перро девочке помогает не крестная, а мать-покойница: на ее могиле живет белая птичка, исполняющая желания.

Братья Гримм тоже по-своему интерпретировали сюжет Золушки: по их мнению, вредные сестры бедной сиротки должны были получить по заслугам. Пытаясь втиснуться в заветную туфельку, одна из сестер отрубила себе палец, а вторая — пятку. Но жертва оказалась напрасной — принца предупредили голуби:

Погляди-ка, посмотри,

А башмачок-то весь в крови…

Эти же летающие воины справедливости в итоге выклевали сестрам глаза — тут и сказочке конец.

Рапунцель

Рапунцель, Рапунцель, распусти свои косоньки! Скорее всего, в детстве, родители не читали вам эту сказку братьев Гримм, и вы узнали ее только благодаря вездесущему слюнявому Диснею. У Гримм девушка с длинными волосами действительно жила у ведьмы в высокой башне, ее увидел принц, позвал ее так же, как делала ведьма, обманом поднялся по волосам в комнату Рапунцель, поимел девушку, и она забеременела. Само собой, для ведьмы это недолго оставалось тайной, она отрезала волосы Рапунцель и волшебным образом заслала ее в Тмутаракань, где та стала бродяжкой-побирушкой с ребенком на руках. А потом ведьма дождалась принца, которому снова засвербело в одном месте, свесила вниз волосы Рапунцель, и, когда принц забрался до середины башни, просто разжала руки, и принц свалился прямиком в терновник. Это, с одной стороны, смягчило его падение, и он не убился насмерть, с другой — терновник выколол ему глаза. Все остались живы, что можно считать хэппи-эндом.

Красавица и Чудовище

Первоисточник сказки — это ни много ни мало древнегреческий миф о прекрасной Психее, красоте которой завидовали все, начиная от старших сестер, заканчивая богиней Афродитой. Девушку приковали к скале в надежде скормить чудовищу, но чудесным образом ее спасло «незримое существо». Оно, конечно, было мужского пола, потому что сделало Психею своей женой при условии, что она не будет мучать его расспросами. Но, конечно, женское любопытство взяло верх, и Психея узнала, что ее муж вовсе не чудовище, а прекрасный Амур. Супруг Психеи обиделся и улетел, не обещая вернуться. Тем временем свекровь Психеи Афродита, которая с самого начала была против этого брака, решила вконец извести невестку, заставляя ее выполнять разные сложные задачи: например, принести золотое руно с бешеных овец и водички из реки мертвых Стикс. Но Психея все выполнила, а там и Амур вернулся в семью, и жили они долго и счастливо. А глупые завистливые сестры кинулись с утеса, тщетно надеясь, что и на них найдется «незримый дух».

Более близкая к современной истории версия была написана Габриэль-Сюзанн Барбот де Вильнев в 1740 году. В ней все сложно: Чудовище, по сути, несчастный сирота. Его отец погиб, а мать была вынуждена защищать свое королевство от врагов, поэтому воспитание сына доверила чужой тете. Та оказалась злой колдуньей, вдобавок хотела соблазнить мальчика, а получив отказ, превратила его в ужасного зверя. У Красавицы тоже в шкафу свои скелеты: она на самом деле не родная, а приемная дочь купца. Ее настоящий отец — король, согрешивший с залетной доброй феей. Но на короля претендует и злая колдунья, так что дочку ее соперницы решено было отдать купцу, у которого как раз погибла младшая дочь. Ну, и любопытный факт о сестрах Красавицы: когда зверь отпускает ее погостить у родных, «добрые» девицы специально заставляют ее задержаться в надежде, что чудище озвереет и съест ее. Кстати, этот тонкий родственный момент показан в последней киноверсии «Красавицы и Чудовища» с Венсаном Касселем и Леей Сейду.

Еще крутые истории!

Забудьте все, что вы знали об этой знаменитой истории. В ее первоначальной версии принца заменяет уже женатый король. Думаете, он целовал красавицу? Отнюдь… надругался над ней, воспользовавшись ее беспомощным положением. Вот вам суровая правда, очень далекая от слащавых мультиков Диснея.

Давным-давно…

На самом деле, большинство сказочников и басенников являются простыми пересказчиками. Мало у кого из них хватало фантазии придумать что-то свое. Так получилось и со сказкой «Спящая красавица». Эта история, известная как «Солнце, Луна и Талия», была написана или, по крайней мере, переработана итальянским поэтом Джамбаттистой Базиле.

Текст опубликован в 1634 году в сборнике сказок «Пентамерон». Там же, кстати, присутствуют и самые ранние известные версии «Золушки» и «Кота в сапогах».

Для современников Джамбаттиста Базиле был «Шарлем Перро» того времени. Один из братьев Гримм, в частности, признает следующее: «Пентамерон Базиля был самым богатым собранием сказок. Автор проявил большой талант, собирая все эти истории и пересказывая их».

Хотя сегодня существует множество вариаций «Солнца, Луны и Талии», первоначальная версия рассказывает нам грустную историю девушки, дочери могущественного лорда. При ее рождении лорд вызывает умнейших людей королевства, дабы предсказать будущее наследницы. Звездочеты поведали, что льняное семя вызовет смерть принцессы.

Тогда лорд решает убрать из королевства все, что близко или отдаленно напоминает лен. Однако когда Талия стала молодой девушкой, она заметила прядущую старуху и решила ей помочь. В ходе этого эксперимента льняное семя застряло под ногтем, и Талия упала замертво. В отчаянии отец одел ее в лучшие одежды, усадил на бархатное кресло и покинул дворец.

Спустя многие годы уже другой король наткнулся на заброшенный замок, оказавшийся посреди леса. Дело происходило во время охоты, когда сокол проскользнул внутрь здания. Король долгое время барабанил по дверям, но ему, разумеется, никто не ответил и не открыл. Королю ничего не оставалось, кроме как взобраться на стены и влезть в окно.

Пока, похоже, ничто не отличает эту историю от версии господина Перро. За исключением того, что король был заменен очаровательным принцем. Но именно здесь сказка принимает совершенно иной оборот.

Небольшой флирт?

Войдя в заброшенное поместье, король блуждает, обнаруживая пустые и пыльные комнаты. В конечном итоге он отыскивает красивую молодую женщину, которую, несмотря на все усилия, невозможно разбудить. Теперь из первоисточника:

«Опьяненный желанием, король несет ее в постель. И, пожав плоды любви, оставляет лежать там. Затем возвращается в свое королевство, надолго забывая об этом романе».

Каково? Роман, видите ли, у короля. Где тут невинные поцелуи? Впрочем, дальше еще забористей.

Талия забеременела, так и не проснувшись. Ее дети появились на свет, и о них заботились феи. Сказочные персонажи, по всей видимости, обслуживали и спящую мать, не защитив ее, впрочем, от негодяя.

Итак, феи несут младенцев к Талии, чтобы покормить. Ребенок путает грудь с пальцем, начинает сосать. Льняное семя выпадает из-под ногтя, красавица просыпается. С добрым утром, как говорится…

Любовь-морковь

Спустя некоторое время король вспоминает о молодой девушке и решает наведаться в замок во второй раз. Видимо, захотел повторить блуд. Когда он прибыл на место происшествия, нашел Талию бодрствующей, да еще с двумя младенцами на руках. Она назвала их «Солнцем» и «Луной», из-за «загадочной» природы рождения.

Король утверждает, что безумно любит Талию, попутно объясняя, как она забеременела. Несмотря на явный факт гнусного поступка, красавица отвечает взаимностью. Любовь зла…

Тут появляется другая проблема: король женат. Мало того, его жена что-то заподозрила. Царственный муж, оказывается, имел привычку болтать во сне. Вот и произносил имена Талии и двух ее детей, когда супруга подслушивала.

Королева требует, чтобы слуга раскрыл ей всю правду. Поняв, что происходит, она посылает повара замка, наказав похитить детей и расправиться с ними. И ладно просто расправиться, королева поручает повару сварить бедолаг, накормив этим блюдом своего мужа. Добрая сказка, не находите?

В то же время, саму Талию планируется бросить на костер. Хотя красавица объясняет, что она-де подверглась жестокому насилию, будучи без сознания… Но похоже, ничто не может унять гнев разъяренной королевы.

«Счастливый» конец

Талия просит разрешения полностью раздеться, прежде чем окажется на костре. Зачем, интересно? Именно в этот момент король врывается во двор замка, обнаружив неприглядные поступки своей жены. В конце концов, он спасает Талию, приказывая отправить на костер супругу и слугу, который рассказал, про гламурные делишки венценосного. Сжечь, умертвить, съесть… Похоже, у них вся семейка была ненормальная.

Та же участь ждала и повара. К счастью, тот признался, что пощадил детей, спрятав их от гнева королевы. Один вменяемый человек нашелся. Повара простили, и даже назначили камергером. Сам же монарх женится на женщине, над бесчувственным телом которой ранее надругался. И жили они вместе долго и счастливо, пока не умерли…

Еще одна деталь. Сказка заканчивается особенно сомнительной моралью: «Удачливые получат добро. Даже будучи во сне». Понравилась сказка?

Ответ на загадку: «Чем массовая культура заменила изнасилование девушки находящейся в невменяемом состоянии в этой истории, записанной итальянским колониальным чиновником четыре века назад?»

Речь идет о сказке: «Спящая красавица». Первым записал её граф Джамбаттиста Базиле (1575—1632). Вышла она под псевдонимом Джан Алесио Аббаттутисом весной 1634 года в Неаполе, в издательстве Бельтрамо, в сборнике «Сказка Сказок».

«У итальянцев есть «Сказка Сказок», или «Пентамерон»,— самое богатое и самое изысканное из всех сказочных собраний мира«,— писал в 1822 г. Якоб Гримм. Так же оценивали книгу французы, англичане, испанцы…

«Базиле прожил жизнь, обычную для бедного литератора XVII в. В юности военная служба (венецианский гарнизон на Крите), затем — возвращение на родину, более хлебное и тихое место литературного секретаря князя Стильяно. Сменив добровольное служение независимому государству — Венеции — на карьеру феодального чиновника в одной из колоний Испании, какой была в то время неаполитанская провинция, Базиле разделил участь безродной челяди, зависимой от случайностей и не защищенной от произвола. И, продвигаясь по службе (к концу жизни он был удостоен графского титула и земельного владения), он, подобно другим поэтам века, культивировал в себе ту раздвоенность, которая позволяла быть на службе осторожным дипломатом, а в частной жизни — повесой, служителем муз, душой литературных клубов — академий. Еще на Крите он стад членом академии Чудаков, в Неаполе вошел в среду Досужих, состоял заочным членом венецианской академии Неизвестных. Всюду он числился под кличкой «Лентяй», данной за феноменальную работоспособность» — так описывает его филолог переводчик Елена Костюкович.

Базиле, который оставил после себя и сборники мадригалов, од и пасторалей, и поэму «Феоген», и ряд филологических работ, и комментированные издания классиков Ренессанса, как и Шарль Перро постеснялся выпустить записи сказок (которые обеспечили ему литературное бессмертие) под своим именем. «Джан Алесио Аббаттутис» — это псевдоним, которым он подписывал книги, написанные не на литературном языке, а на диалекте. А «Сказка Сказок», или «Пентамерон» не только была написанна на диалекте, но и переполнена площадной речью, пересыпанной уличными присловьями, отчаянной бранью, божбой и проклятиями, жаргоном казармы и игорного дома, сочными шутками на тему виселицы… В сказках Базиле вообще торжествует расхожая мораль здравого смысла, довольно далекая от христианской. Книга, вообще была выпущена только после смерти автора, который при жизни смешил своими рассказиками близких друзей, но не торопился их печатать.

Так вот, именно в коллекции сказок 1634 года итальянского сказочника Джамбаттиста Базиле впервые была опубликована сказка о спящей красавице. Героиню у Базиле зовут Талия. Начинается сказка достаточно традиционно – со злого проклятия колдуньи и снотворного укола веретена.

Правда, далее с принцессой особо не возятся, а помещают в заброшенную лесную избушку. Спустя время, как и положено, на избушку натыкается охотящийся чужеземный король, но обнаружив спящую красотку, он…

Многие из нас слышали пошловатый анекдот про то как принц в который раз залезал на спящую красавицу, а целовать не спешил. Так вот, фольклор не обманешь. Анекдот как современная форма устного народного творчества приближается к оригиналу больше, чем литературная обработка сказки.

В оригинале поцелуй вовсе не является терапевтическим способом пробуждения от вечного сна. И правильно, что не является.

Отчего заснула Спящая красавица? От занозы. Укололась веретеном. Следовательно, пока занозу не вытащишь — принцесса не проснется.

А ваш благопристойный поцелуй, прошу прощения, тут не функционален.

В оригинале рассказывается как король приехав воспользовался невменяемым состоянием Спящей красавицы и овладел её телом, девушка, не приходя в сознание, забеременела и спустя положенный срок разродилась двойней. Она родила мальчика и девочку, которые лежали рядом с ней и сосали её грудь.

Неизвестно, сколько бы это продолжалось, если бы однажды мальчик не потерял материнскую грудь и не принялся бы сосать её палец — тот самый, уколотый веретеном. И высосал занозу (если кто-то искал доказательств того, что отсос лучше поцелуя…).

Шип выскочил, и принцесса очнулась, обнаружив себя в заброшенном домике в полном одиночестве, если не считать откуда ни возьмись взявшихся прелестных младенцев.

А тут и король решил вновь за «плодами любви» наведаться.Увидев Талию с детьми, он наконец-то… влюбился, и стал проведывать их чаще.

Даже в сказке бывают обычные трудности. Король — был мужчиной женатым. И жена его, представьте себе, плохо относилась к связям на стороне…

Тем более, что каждую ночь венценосный любовник во сне поминал проснувшуюся красавицу и её деток, называл во сне жену другим именем. Или покидал своё царственное ложе и уходил в сад грустить, вспоминая о прекрасной Талии и её детях — мальчике по имени Солнце и девочке по имени Луна.

И супруга что-то заподозрила. Сначала она допросила одного из королевских сокольничих, а потом перехватила гонца с письмом короля к Талии.

Королева приказала схватить всех троих, малышей убить, приготовить из них несколько блюд и подать их королю на обед.

За обедом, когда король нахваливал мясные пироги, королева всё время бормотала: «Ты ешь своё!» Королю надоело слушать бормотания супруги, и он резко оборвал её: «Конечно, я ем свое — ведь ты была бесприданницей!»

Но у повара было доброе сердце, и как только он увидел двух ангелочков, то его охватила жалость, и он передал их своей жене, чтобы та спрятала детей, сам же взял двух козлят, приготовил их на разный манер…

А королева, думая, что она уже расправилась с малышами, решила разделаться и с экс-Спящей красавицей. Она приказала привести к ней Талию, чтобы разделаться с «потаскушкой»…

Талия уверяла, что король взял её, когда она спала, без её ведома. Но королева была непреклонна, не хотела слышать никаких извинений и оправданий. Она приказала сложить во внутреннем дворике замка огромный костёр и бросить туда Талию.

Та же увидев, какая грозит ей опасность, упала на колени и стала умолять дать ей отсрочку хотя бы на то, чтобы снять одежду. Королева, не столько из сочувствия к несчастной, сколько позарившись на её вышитое жемчугом и золотом старинное одеяние, ответила : « — Что ж, раздевайся», и Талия начала раздеваться, и каждую снимаемую вещь сопровождала громким рыданием.

Эти рыдания (наконец!) расслышал король, который вовремя появился, спас Талию, бросил в костер королеву… А далее король женился на Талии, и та жила со своим супругом и детьми долго и счастливо, и сама же признала:

«Тому, к кому небо благоволит — везёт даже во сне».

Этой забавной моралью заканчивается сказка «Спящая красавица» Джамбаттиста Базиле, вышедшая весной 1634 года.

Интересно, что в сборнике Шарля Перро, который сильно пригладил сказку, повествование завершает иной вывод:

«Немножко обождать,

чтоб подвернулся муж,

Красавец и богач к тому ж,

Вполне возможно и понятно.

Но сотню долгих лет,

в постели лежа, ждать

Для дам настолько неприятно,

Что ни одна не сможет спать…«.

Я же, завершая свой пост, предлагаю извлекать мораль и делать выводы читателю.

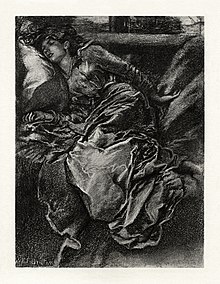

| The Sleeping Beauty | |

|---|---|

The prince finds the Sleeping Beauty, in deep slumber amidst the bushes. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Sleeping Beauty |

| Also known as | La Belle au bois dormant (The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods); Dornröschen (Little Briar Rose) |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 410 (Sleeping Beauty) |

| Region | France (1528) |

| Published in | Perceforest (1528) Pentamerone (1634), by Giambattista Basile Histoires ou contes du temps passé (1697), by Charles Perrault |

| Related | Sun, Moon and Talia |

Sleeping Beauty (French: La belle au bois dormant, or The Beauty in the Sleeping Forest; German: Dornröschen, or Little Briar Rose), also titled in English as The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods, is a fairy tale about a princess cursed by an evil fairy to sleep for a hundred years before being awoken by a handsome prince. A good fairy, knowing the princess would be frightened if alone when she wakes, uses her wand to put every living person and animal in the palace and forest asleep, to waken when the princess does.[1]

The earliest known version of the tale is found in the narrative Perceforest, written between 1330 and 1344. Another was published by Giambattista Basile in his collection titled The Pentamerone, published posthumously in 1634[2] and adapted by Charles Perrault in Histoires ou contes du temps passé in 1697. The version collected and printed by the Brothers Grimm was one orally transmitted from the Perrault.[3]

The Aarne-Thompson classification system for fairy tales lists Sleeping Beauty as a Type 410: it includes a princess who is magically forced into sleep and later woken, reversing the magic.[4] The fairy tale has been adapted countless times throughout history and retold by modern storytellers across a variety of media.

Origin[edit]

Early contributions to the tale include the medieval courtly romance Perceforest (published in 1528).[5] In this tale, a princess named Zellandine falls in love with a man named Troylus. Her father sends him to perform tasks to prove himself worthy of her, and while he is gone, Zellandine falls into an enchanted sleep. Troylus finds her and rapes her in her sleep; when their child is born, the child draws from her finger the flax that caused her sleep. She realizes from the ring Troylus left her that he was the father, and Troylus later returns to marry her.[6] Another early literary predecessor is the Provençal versified novel Fraire de Joi e sor de Plaser [ca] (c. 1320-1340).[7][8]

The second part of the Sleeping Beauty tale, in which the princess and her children are almost put to death but instead are hidden, may have been influenced by Genevieve of Brabant.[9] Even earlier influences come from the story of the sleeping Brynhild in the Volsunga saga and the tribulations of saintly female martyrs in early Christian hagiography conventions. Following these early renditions, the tale was first published by Italian poet Giambattista Basile who lived from 1575 to 1632.

Plot[edit]

The folktale begins with a princess whose parents are told by a wicked fairy that their daughter will die when she pricks her finger on a particular item. In Basile’s version, the princess pricks her finger on a piece of flax. In Perrault’s and the Grimm Brothers’ versions, the item is a spindle. The parents rid the kingdom of these items in the hopes of protecting their daughter, but the prophecy is fulfilled regardless. Instead of dying, as was foretold, the princess falls into a deep sleep. After some time, she is found by a prince and is awakened. In Giambattista Basile’s version of Sleeping Beauty, Sun, Moon, and Talia, the sleeping beauty, Talia, falls into a deep sleep after getting a splinter of flax in her finger. She is discovered in her castle by a wandering king, who «carrie[s] her to a bed, where he gather[s] the first fruits of love.»[10] He leaves her there and she later gives birth to twins.[11]

According to Maria Tatar, there are versions of the story that include a second part to the narrative that details the couple’s troubles after their union; some folklorists believe the two parts were originally separate tales.[12]

The second part begins after the prince and princess have had children. Through the course of the tale, the princess and her children are introduced in some way to another woman from the prince’s life. This other woman is not fond of the prince’s new family, and calls a cook to kill the children and serve them for dinner. Instead of obeying, the cook hides the children and serves livestock. Next, the other woman orders the cook to kill the princess. Before this can happen, the other woman’s true nature is revealed to the prince and then she is subjected to the very death that she had planned for the princess. The princess, prince, and their children live happily ever after.[13]

Basile’s narrative[edit]

In Giambattista Basile’s dark version of Sleeping Beauty, Sun, Moon, and Talia, the sleeping beauty is named Talia. By asking wise men and astrologers to predict her future after her birth, her father who is a great Lord learns that Talia will be in danger from a splinter of flax. The splinter later causes what appears to be Talia’s death; however, it is later learned that it is a long, deep sleep. After Talia falls into deep sleep, she is seated on a velvet throne and her father, to forget his misery of what he thinks is her death, closes the doors and abandons the house forever. One day, while a king is walking by, one of his falcons flies into the house. The king knocks, hoping to be let in by someone, but no one answers and he decides to climb in with a ladder. He finds Talia alive but unconscious, and «…gathers the first fruits of love.»[14] Afterwards, he leaves her in the bed and goes back to his kingdom. Though Talia is unconscious, she gives birth to twins — one of whom keeps sucking her fingers. Talia awakens because the twin has sucked out the flax that was stuck deep in Talia’s finger. When she wakes up, she discovers that she is a mother and has no idea what happened to her. One day, the king decides he wants to go see Talia again. He goes back to the palace to find her awake and a mother to his twins. He informs her of who he is, what has happened, and they end up bonding. After a few days, the king has to leave to go back to his realm, but promises Talia that he will return to take her to his kingdom.

When he arrives back in his kingdom, his wife hears him saying «Talia, Sun, and Moon» in his sleep. She bribes and threatens the king’s secretary to tell her what is going on. After the queen learns the truth, she pretends she is the king and writes to Talia asking her to send the twins because he wants to see them. Talia sends her twins to the «king» and the queen tells the cook to kill the twins and make dishes out of them. She wants to feed the king his children; instead, the cook takes the twins to his wife and hides them. He then cooks two lambs and serves them as if they were the twins. Every time the king mentions how good the food is, the queen replies, «Eat, eat, you are eating of your own.» Later, the queen invites Talia to the kingdom and is going to burn her alive, but the king appears and finds out what’s going on with his children and Talia. He then orders that his wife be burned along with those who betrayed him. Since the cook actually did not obey the queen, the king thanks the cook for saving his children by giving him rewards. The story ends with the king marrying Talia and living happily ever after.[10]

Perrault’s narrative[edit]

Perrault’s narrative is written in two parts, which some folklorists believe were originally separate tales, as they were in the Brothers Grimm’s version, and were later joined together by Giambattista Basile and once more by Perrault.[12] According to folklore editors Martin Hallett and Barbara Karasek, Perrault’s tale is a much more subtle and pared down version than Basile’s story in terms of the more immoral details. An example of this is depicted in Perrault’s tale by the prince’s choice to instigate no physical interaction with the sleeping princess when the prince discovers her.[2]

At the christening of a king and queen’s long-wished-for child, seven good fairies are invited to be godmothers to the infant princess. The fairies attend the banquet at the palace. Each fairy is presented with a golden plate and drinking cups adorned with jewels. Soon after, an old fairy enters the palace and is seated with a plate of fine china and a crystal drinking glass. This old fairy is overlooked because she has been within a tower for many years and everyone had believed her to be deceased. Six of the other seven fairies then offer their gifts of beauty, wit, grace, dance, song, and goodness to the infant princess. The evil fairy is very angry about having been forgotten, and as her gift, curses the infant princess so that she will one day prick her finger on a spindle of a spinning wheel and die. The seventh fairy, who has not yet given her gift, attempts to reverse the evil fairy’s curse. However, she can only do so partially. Instead of dying, the Princess will fall into a deep sleep for 100 years and be awakened by a king’s son («elle tombera seulement dans un profond sommeil qui durera cent ans, au bout desquels le fils d’un Roi viendra la réveiller«). This is her gift of protection.

The King orders that every spindle and spinning wheel in the kingdom be destroyed, to try to save his daughter from the terrible curse. Fifteen or sixteen years pass and one day, when the king and queen are away, the Princess wanders through the palace rooms and comes upon an old woman (implied to be the evil fairy in disguise), spinning with her spindle. The princess, who has never seen anyone spin before, asks the old woman if she can try the spinning wheel. The curse is fulfilled as the princess pricks her finger on the spindle and instantly falls into a deep sleep. The old woman cries for help and attempts are made to revive the princess. The king attributes this to fate and has the Princess carried to the finest room in the palace and placed upon a bed of gold and silver embroidered fabric. The king and queen kiss their daughter goodbye and depart, proclaiming the entrance to be forbidden. The good fairy who altered the evil prophecy is summoned. Having great powers of foresight, the fairy sees that the Princess will awaken to distress when she finds herself alone, so the fairy puts everyone in the castle to sleep. The fairy also summons a forest of trees, brambles and thorns that spring up around the castle, shielding it from the outside world and preventing anyone from disturbing the Princess.

A hundred years pass and a prince from another family spies the hidden castle during a hunting expedition. His attendants tell him differing stories regarding the castle until an old man recounts his father’s words: within the castle lies a beautiful princess who is doomed to sleep for a hundred years until a king’s son comes and awakens her. The prince then braves the tall trees, brambles and thorns which part at his approach, and enters the castle. He passes the sleeping castle folk and comes across the chamber where the Princess lies asleep on the bed. Struck by the radiant beauty before him, he falls on his knees before her. The enchantment comes to an end, the princess awakens and bestows upon the prince a look “more tender than a first glance might seem to warrant” (in Perrault’s original French tale, the prince does not kiss the princess to wake her up) then converses with the prince for a long time. Meanwhile, the rest of the castle awakens and go about their business. The prince and princess are later married by the chaplain in the castle chapel.

After wedding the Princess in secret, the Prince continues to visit her and she bears him two children, Aurore (Dawn) and Jour (Day), unbeknownst to his mother, who is of an ogre lineage. When the time comes for the Prince to ascend the throne, he brings his wife, children, and the talabutte («Count of the Mount»).

The Ogress Queen Mother sends the young Queen and the children to a house secluded in the woods and directs her cook to prepare the boy with Sauce Robert for dinner. The kind-hearted cook substitutes a lamb for the boy, which satisfies the Queen Mother. She then demands the girl but the cook this time substitutes a kid, which also satisfies the Queen Mother. When the Ogress demands that he serve up the young Queen, the latter offers to slit her throat so that she may join the children that she imagines are dead. While the Queen Mother is satisfied with a hind prepared with Sauce Robert in place of the young Queen, there is a tearful secret reunion of the Queen and her children. However, the Queen Mother soon discovers the cook’s trick and she prepares a tub in the courtyard filled with vipers and other noxious creatures. The King returns in the nick of time and the Ogress, her true nature having been exposed, throws herself into the tub and is fully consumed. The King, young Queen, and children then live happily ever after.

Grimm Brothers’ version[edit]

Sleeping Beauty and the palace dwellers under a century-long sleep enchantment (The Sleeping Beauty by Sir Edward Burne-Jones).

The Brothers Grimm included a variant of Sleeping Beauty, Little Briar Rose, in their collection (1812).[15] Their version ends when the prince arrives to wake Sleeping Beauty (named Rosamund) and does not include the part two as found in Basile’s and Perrault’s versions.[16] The brothers considered rejecting the story on the grounds that it was derived from Perrault’s version, but the presence of the Brynhild tale convinced them to include it as an authentically German tale. Their decision was notable because in none of the Teutonic myths, meaning the Poetic and Prose Eddas or Volsunga Saga, are their sleepers awakened with a kiss, a fact Jacob Grimm would have known since he wrote an encyclopedic volume on German mythology. His version is the only known German variant of the tale, and Perrault’s influence is almost certain.[17] In the original Brothers Grimm’s version, the fairies are instead wise women.[18]

The Brothers Grimm also included, in the first edition of their tales, a fragmentary fairy tale, «The Evil Mother-in-law». This story begins with the heroine, a married mother of two children, and her mother-in-law who attempts to eat her and the children. The heroine suggests an animal be substituted in the dish, and the story ends with the heroine’s worry that she cannot keep her children from crying and getting the mother-in-law’s attention. Like many German tales showing French influence, it appeared in no subsequent edition.[19]

Variations[edit]

He stands—he stoops to gaze—he kneels—he wakes her with a kiss, woodcut by Walter Crane

The princess’s name has varied from one adaptation to the other. In Sun, Moon, and Talia, she is named Talia (Sun and Moon being her twin children). She has no name in Perrault’s story but her daughter is called «Aurore». The Brothers Grimm named her «Briar Rose» in their 1812 collection.[15] However, some translations of the Grimms’ tale give the princess the name «Rosamond». Tchaikovsky’s ballet and Disney’s version named her Princess Aurora; however, in the Disney version, she is also called «Briar Rose» in her childhood, when she is being raised incognito by the good fairies.[20]

Besides Sun, Moon, and Talia, Basile included another variant of this Aarne-Thompson type, The Young Slave, in his book, The Pentamerone. The Grimms also included a second, more distantly related one titled The Glass Coffin.[21]

Italo Calvino included a variant in Italian Folktales. In his version, the cause of the princess’s sleep is a wish by her mother. As in Pentamerone, the prince rapes her in her sleep and her children are born. Calvino retains the element that the woman who tries to kill the children is the king’s mother, not his wife, but adds that she does not want to eat them herself, and instead serves them to the king. His version came from Calabria, but he noted that all Italian versions closely followed Basile’s.[22][23]

In his More English Fairy Tales, Joseph Jacobs noted that the figure of the Sleeping Beauty was in common between this tale and the Romani tale The King of England and his Three Sons.[24]

The hostility of the king’s mother to his new bride is repeated in the fairy tale The Six Swans,[25] and also features in The Twelve Wild Ducks, where the mother is modified to be the king’s stepmother. However, these tales omit the attempted cannibalism.

Russian Romantic writer Vasily Zhukovsky wrote a versified work based on the theme of the princess cursed into a long sleep in his poem «Спящая царевна» («The Sleeping Tsarevna» [ru]), published in 1832.[26]

Interpretations[edit]

According to Maria Tatar, the Sleeping Beauty tale has been disparaged by modern-day feminists who consider the protagonist to have no agency and find her passivity to be offensive; some feminists have even argued for people to stop telling the story altogether.[27]

Disney has received criticism for depicting both Cinderella and the Sleeping Beauty princess as «naïve and malleable» characters.[28] Time Out dismissed the princess as a «delicate» and «vapid» character.[29] Sonia Saraiya of Jezebel echoed this sentiment, criticizing the princess for lacking «interesting qualities», where she also ranked her as Disney’s least feminist princess.[30] Similarly, Bustle also ranked the princess as the least feminist Disney Princess, with author Chelsea Mize expounding, «Aurora literally sleeps for like three quarters of the movie … Aurora just straight-up has no agency, and really isn’t doing much in the way of feminine progress.»[31] Leigh Butler of Tor.com went on to defend the character writing, «Aurora’s cipher-ness in Sleeping Beauty would be infuriating if she were the only female character in it, but the presence of the Fairies and Maleficent allow her to be what she is without it being a subconscious statement on what all women are.»[32] Similarly, Refinery29 ranked Princess Aurora the fourth most feminist Disney Princess because, «Her aunts have essentially raised her in a place where women run the game.»[33] Despite being featured prominently in Disney merchandise, «Aurora has become an oft-forgotten princess», and her popularity pales in comparison to those of Cinderella and Snow White.[34]

An example of the cosmic interpretation of the tale given by the nineteenth century solar mythologist school[35] appears in John Fiske’s Myths and Myth-Makers: “It is perhaps less obvious that winter should be so frequently symbolized as a thorn or sharp instrument… Sigurd is slain by a thorn, and Balder by a sharp sprig of mistletoe; and in the myth of the Sleeping Beauty, the earth-goddess sinks into her long winter sleep when pricked by the point of the spindle. In her cosmic palace, all is locked in icy repose, naught thriving save the ivy which defies the cold, until the kiss of the golden-haired sun-god reawakens life and activity.”[36]

Media[edit]

«Sleeping Beauty» has been popular for many fairytale fantasy retellings. Some examples are listed below:

In film and television[edit]

- The Sleeping Princess (1939), a Walter Lantz Productions animated short parodying the original fairy tale.[37]

- A loose adaptation can be seen in a scene from the propaganda cartoon Education for Death, where Sleeping Beauty is a valkyrie representing Nazi Germany, and where the prince is replaced with Fuehrer Adolf Hitler in knights’ armor. The short also parodies Richard Wagner’s opera Siegfried.

- Prinsessa Ruusunen (1949), a Finnish film directed by Edvin Laine and scored with Erkki Melartin’s incidental music from 1912.[38]

- Dornröschen (1955), a West German film directed by Fritz Genschow.[39]

- Sleeping Beauty (1959), a Walt Disney animated film based on both Charles Perrault and the Brother’s Grimm’s versions. Featuring the original voices of Mary Costa as Princess Aurora, the Sleeping Beauty and Eleanor Audley as Maleficent.[40]

- Sleeping Beauty (Спящая красавица) (1964), a filmed version of the ballet produced by the Kirov Ballet along with Lenfilm studios, starring Alla Sizova as Princess Aurora.[41]

- Festival of Family Classics (1972-73), episode Sleeping Beauty, produced by Rankin/Bass and animated by Mushi Production.[42]

- Some Call It Loving (also known as Sleeping Beauty) (1973), directed by James B. Harris and starring Zalman King, Carol White, Tisa Farrow, and Richard Pryor, based on a short story by John Collier.[43]

- Manga Sekai Mukashi Banashi (1976-79), 10-minute adaptation.

- Jak se budí princezny (1978), a Czechoslovakian film directed by Václav Vorlíček.[44]

- World Famous Fairy Tale Series (Sekai meisaku dōwa) (1975-83) has a 9-minute adaptation, later reused in the U.S. edit of My Favorite Fairy Tales.

- Goldilocks and the Three Bears/Rumpelstiltskin/Little Red Riding Hood/Sleeping Beauty (1984), direct-to-video featurette by Lee Mendelson Film Productions.[45]

- Sleeping Beauty (1987), a direct-to-television musical film directed by David Irving.[46]

- The Legend of Sleeping Brittany (1989), an episode of Alvin & the Chipmunks based on the fairy tale.[47]

- Briar-Rose or The Sleeping Beauty (1990), a Japanese/Czechoslovakian stop-motion animated featurette directed by Kihachiro Kawamoto.

- Britannica’s Tales Around the World (1990-91), features three variations of the story.[48]

- An episode of the series Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics is dedicated to Princess Briar Rose.[49]

- A 1986 episode of Brummkreisel had Kunibert (Hans-Joachim Leschnitz) demanding that he and his friends Achim (Joachim Kaps), Hops and Mops enact the story of Sleeping Beauty. Achim first compromises by incorporating Sleeping Beauty into his lesson about days of the week, and then finally he allows Kunibert to have his way; Hops played the princess, Kunibert played the prince, Mops played the wicked fairy and Achim played the brambles.

- World Fairy Tale Series (Anime sekai no dōwa) (1995), anime television anthology produced by Toei Animation, has half-hour adaptation.

- Sleeping Beauty (1995), a Japanese-American direct-to-video film by Jetlag Productions.[50]

- Wolves, Witches and Giants (1995-99), episode Sleeping Beauty, season 1 episode 5.

- Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child (1995), episode Sleeping Beauty, the classic story is told with a Hispanic cast, when Rosita is cast into a long sleep by Evelina, and later awakened by Prince Luis.[51]

- The Triplets (Les tres bessones/Las tres mellizas) (1997-2003), catalan animated series, season 1 episode 19.

- Simsala Grimm (1999-2010), episode 9 of season 2.

- Bellas durmientes (Sleeping Beauties) (2001), directed by Eloy Lozano, adapted from the Kawabata novel.[52]

- La belle endormie (The Sleeping Beauty) (2010), a film by Catherine Breillat.[53]

- Sleeping Beauty (2011), directed by Julia Leigh and starring Emily Browning, about a young girl who takes a sleeping potion and lets men have their way with her to earn extra money.[54]

- Once Upon a Time (2011), an ABC TV show starring Sarah Bolger and Julian Morris.[55]

- Sleeping Beauty (2014), a film by Rene Perez.[56]

- Sleeping Beauty (2014), a film by Casper Van Dien.[57]

- Maleficent (2014), a Walt Disney live-action reimagining starring Angelina Jolie as Maleficent and Elle Fanning as Princess Aurora.[58]

- Ever After High, episode Briar Beauty (2015), an animated Netflix series.[59]

- The Curse of Sleeping Beauty (2016), an American horror film directed by Pearry Reginald Teo.[60]

- Archie Campbell satirized the story with «Beeping Sleauty» in several Hee Haw television episodes.

- Maleficent: Mistress of Evil (2019), a Walt Disney live-action sequel to Maleficent (2014).[61]

- Avengers Grimm (2015) portrays an adult Sleeping Beauty with superpowers.

In literature[edit]

- Sleeping Beauty (1830) and The Day-Dream (1842), two poems based on Sleeping Beauty by Alfred, Lord Tennyson.[62]

- The Rose and the Ring (1854), a satirical fantasy by William Makepeace Thackeray.

- The Sleeping Beauty (1919), a poem by Mary Carolyn Davies about a failed hero who did not waken the princess, but died in the enchanted briars surrounding her palace.[63]

- The Sleeping Beauty (1920), a retelling of the fairy tale by Charles Evans, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham.[64]

- Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty) (1971), a poem by Anne Sexton in her collection Transformations (1971), in which she re-envisions sixteen of the Grimm’s Fairy Tales.[65]

- The Sleeping Beauty Quartet (1983-2015), four erotic novels written by Anne Rice under the pen name A.N. Roquelaure, set in a medieval fantasy world and loosely based on the fairy tale.[66]

- Beauty (1992), a novel by Sheri S. Tepper.[67]

- Briar Rose (1992), a novel by Jane Yolen.[68]

- Enchantment (1999), a novel by Orson Scott Card based on the Russian version of Sleeping Beauty.

- Spindle’s End (2000), a novel by Robin McKinley.[69]

- Clementine (2001), a novel by Sophie Masson.[70]

- A Kiss in Time (2009), a novel by Alex Flinn.[71]

- The Sleeper and the Spindle (2012), a novel by Neil Gaiman.[72]

- The Gates of Sleep (2012), a novel by Mercedes Lackey from the Elemental Masters series set in Edwardian England.[73]

- Sleeping Beauty: The One Who Took the Really Long Nap (2018), a novel by Wendy Mass and the second book in the Twice Upon a Time series features a princess named Rose who pricks her finger and falls asleep for 100 years.[74]

- The Sleepless Beauty (2019), a novel by Rajesh Talwar setting the story in a small kingdom in the Himalayas.[75]

- Lava Red Feather Blue (2021), a novel by Molly Ringle involving a male/male twist on the Sleeping Beauty story.

- Malice (2021), a novel by Heather Walter told by the Maleficent character’s (Alyce’s) POV and involving a woman/woman love story. [76]

- Misrule (2022), a novel by Heather Walter and sequel to Malice. [77]

In music[edit]

The Sleeping Beauty, ballet Emily Smith

- La Belle au Bois Dormant (1825), an opera by Michele Carafa.

- La belle au bois dormant (1829), a ballet in four acts with book by Eugène Scribe, composed by Ferdinand Hérold and choreographed by Jean-Louis Aumer.

- The Sleeping Beauty (1890), a ballet by Tchaikovsky.

- Dornröschen (1902), an opera by Engelbert Humperdinck.

- Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant (1910), the first movement of Ravel’s Ma mère l’Oye.[78]

- The Sleeping Beauty (1992), song on album Clouds by the Swedish band Tiamat.

- Sleeping Beauty Wakes (2008), an album by the American musical trio GrooveLily.[79]

- There Was A Princess Long Ago, a common nursery rhyme or singing game typically sung stood in a circle with actions, retells the story of Sleeping Beauty in a summarised song.[80]

- Sleeping Beauty The Musical (2019), a two act musical with book and lyrics by Ian Curran and music by Simon Hanson and Peter Vint.[81]

- Hex (2021), an upcoming musical with book by Tanya Ronder, music by Jim Fortune and lyrics by Rufus Norris due to open at the Royal National Theatre in December 2021.

In video games[edit]

- Kingdom Hearts is a video game in which Maleficent is one of the main antagonists and Aurora is one of the Princesses of Heart together with the other Disney princesses.

- Little Briar Rose (2019) is a point-and-click adventure inspired by the Brothers Grimm’s version of the fairy tale.[82]

- SINoALICE (2017) is a mobile Gacha game which features Sleeping Beauty as one of the main player controlled characters and features in her own dark story-line which follows her unending desire to sleep, as well as crossing over with the other fairy-tale characters featured in the game.

- Video game series Dark Parables adapted the tale as the plot of its first game, Curse of Briar Rose (2010).

In art[edit]

-

Perrault’s La Belle au bois dormant (Sleeping Beauty), illustration by Gustave Doré

-

Prince Florimund finds the «Sleeping Beauty»

-

Sleeping Beauty by Jenny Harbour

-

Book cover for a Dutch interpretation of the story by Johann Georg van Caspel

-

Briar Rose

-

-

Louis Sußmann-Hellborn (1828- 1908) Sleeping Beauty,

-

Sleeping Beauty, statue in Wuppertal – Germany

See also[edit]

- The Glass Coffin

- Princess Aubergine

- Rip Van Winkle

- Snow White

- The Sleeping Prince (fairy tale)

References[edit]

- ^ «410: The Sleeping Beauty». Multilingual Folk Tale Database. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Hallett, Martin; Karasek, Barbara, eds. (2009). Folk & Fairy Tales (4 ed.). Broadview Press. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-1-55111-898-7.

- ^ Bottigheimer, Ruth. (2008). «Before Contes du temps passe (1697): Charles Perrault’s Griselidis, Souhaits and Peau«. The Romantic Review, Volume 99, Number 3. pp. 175–189.

- ^ Aarne, Antti; Thompson, Stith. The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1961. pp. 137-138.

- ^ Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p 648, ISBN 0-393-97636-X.

- ^ Camarena, Julio. Cuentos tradicionales de León. Vol. I. Tradiciones orales leonesas, 3. Madrid: Seminario Menéndez Pidal, Universidad Complutense de Madrid; [León]: Diputación Provincial de León, 1991. p. 415.

- ^ Frayre de Joy e Sor de Plaser. Bibilothèque nationale de France.

- ^ Charles Willing, «Genevieve of Brabant»

- ^ a b Basile, Giambattista. «Sun, Moon, and Talia». Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Collis, Kathryn (2016). Not So Grimm Fairy Tales. ISBN 978-1-5144-4689-8.

- ^ a b Maria Tatar, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, 2002:96, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^ Ashliman, D.L. «Sleeping Beauty». pitt.edu.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty».

- ^ a b Jacob and Wilheim Grimm, Grimms’ Fairy Tales, «Little Briar-Rose» Archived 2007-05-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harry Velten, «The Influences of Charles Perrault’s Contes de ma Mère L’oie on German Folklore», p 961, Jack Zipes, ed. The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ Harry Velten, «The Influences of Charles Perrault’s Contes de ma Mère L’oie on German Folklore», p 962, Jack Zipes, ed. The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-97636-X

- ^ «050 Sleeping Beauty – Great Story Reading Project».

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, p 376-7 W. W. Norton & Company, London, New York, 2004 ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, «The Annotated Sleeping Beauty Archived 2010-02-22 at the Wayback Machine»

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, «Tales Similar to Sleeping Beauty» Archived 2010-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 485 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales p 744 ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, More English Fairy Tales, «The King of England and his Three Sons» Archived 2010-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Brothers Grimm, p 230 W. W. Norton & company, London, New York, 2004 ISBN 0-393-05848-4

- ^ Zhukovsky, Vasily. Спящая царевна (Жуковский) (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- ^ Tatar, Maria (2014). «Show and Tell: Sleeping Beauty as Verbal Icon and Seductive Story». Marvels & Tales. 28 (1): 142–158. doi:10.13110/marvelstales.28.1.0142. S2CID 161271883.

- ^ Hugel, Melissa (November 12, 2013). «How Disney Princesses Went From Passive Damsels to Active Heroes». Mic. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty». Time Out. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Saraiya, Sonia (December 7, 2012). «A Feminist Guide to Disney Princesses». Jezebel. Retrieved January 22, 2016.

- ^ Mize, Chelsea (July 31, 2015). «A Feminist Ranking Of All The Disney Princesses, Because Not Every Princess Was Down For Waiting For Anyone To Rescue Her». Bustle. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ Butler, Leigh (November 6, 2014). «How Sleeping Beauty is Accidentally the Most Feminist Animated Movie Disney Ever Made». Tor.com. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Golembewski, Vanessa (September 11, 2014). «A Definitive Ranking Of Disney Princesses As Feminist Role Models». Refinery29. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ «The Evolution of Disney Princesses». Young Writers Society. March 16, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Dorson, Richard M. (1955). «The Eclipse of Solar Mythology». The Journal of American Folklore. 68 (270): 393–416. doi:10.2307/536766. JSTOR 536766.

- ^ «Myths and Myth-makers, by John Fiske».

- ^ «The Sleeping Princess (1939)». IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty (1949) Prinsessa Ruusunen (original title)». IMDb. 8 April 1949. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty (1955) Dornröschen (original title)». IMDb. 16 November 1955. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty (1959)». IMDb. 30 October 1959. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Dudko, Apollinari; Sergeyev, Konstantin, Spyashchaya krasavitsa (Fantasy, Music, Romance), Lenfilm Studio, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ Bass, Jules; Rankin, Arthur Jr. (1973-01-21), Sleeping Beauty, Festival of Family Classics, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ «Some Call It Loving (1973)». IMDb. 26 October 1973. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Vorlícek, Václav (1978-03-01), Jak se budí princezny (Adventure, Comedy, Family), Deutsche Film (DEFA), Filmové studio Barrandov, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ Melendez, Steven Cuitlahuac, Goldilocks and the Three Bears/Rumpelstiltskin/Little Red Riding Hood/Sleeping Beauty (Animation, Short), On Gossamer Wings Productions, Bill Melendez Productions, retrieved 2022-06-29

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty (1987)». IMDb. 12 June 1987. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Inner Dave/The Legend of Sleeping Brittany». IMDb. 11 November 1989. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Britannica’s Tales Around the World (Animation), Encyclopædia Britannica Films, retrieved 2022-06-29

- ^ Nobara hime, Grimm Masterpiece Theatre, 1988-02-17, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ Hiruma, Toshiyuki; Takashi (1995-03-17), Sleeping Beauty (Animation, Family, Fantasy), Cayre Brothers, Jetlag Productions, retrieved 2022-06-28

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty». IMDb. 23 April 1995. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauties (2001) Bellas durmientes (original title)». IMDb. 9 November 2001. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «The Sleeping Beauty (2010) La belle endormie (original title)». IMDb. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty (2011)». IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Once Upon a Time». IMDb. 23 October 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty (2014)». IMDb. 13 July 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty (2014)». IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Maleficent (2014)». IMDb. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Ever After High». IMDb. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «The Curse of Sleeping Beauty (2016)». IMDb. 2 June 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Maleficent: Mistress of Evil (2019)». IMDb. 20 Oct 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Hill, Robert (1971), Tennyson’s Poetry p. 544. New York: Norton.

- ^ Cook, Howard Willard Our Poets of Today, p. 271, at Google Books

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty, The». David Brass Rare Books. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Transformations by Anne Sexton»

- ^ «The Sleeping Beauty Series». Anne Rice. 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Tepper, Sheri S. (1992). Beauty. ISBN 9780553295276. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Briar Rose». Jane Yolen. 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «Spindle’s End». Penguin Random House Network.

- ^ Clementine. ASIN 0340850698.

- ^ Flinn, Alex (28 April 2009). A Kiss in Time. ISBN 978-0060874193.

- ^ «The Sleeper and the Spindle». Neil Gaiman. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «The Gates of Sleep (Elemental Masters Book 2)». Amazon. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Sleeping Beauty, the One Who Took the Really Long Nap: A Wish Novel (Twice Upon a Time #2): A Wish Novel. ASIN 043979658X.

- ^ «The Sleepless Beauty».

- ^ «Malice».

- ^ «Misrule».

- ^ «Ravel : Ma Mère l’Oye». genedelisa.com.

- ^ «Sleeping Beauty Wakes». bandcamp. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ «There Was A Princess». singalong.org.uk.

- ^ 2019 musical website

- ^ «Little Briar Rose». Nintendo. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

Further reading[edit]

- Artal, Susana. «Bellas durmientes en el siglo XIV». In: Montevideana 10. Universidad de la Republica, Linardi y Risso. 2019. pp. 321–336.

- Starostina, Aglaia. «Chinese Medieval Versions of Sleeping Beauty». In: Fabula, vol. 52, no. 3-4, 2012, pp. 189-206. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabula-2011-0017

- de Vries, Jan. «Dornröschen». In: Fabula 2, no. 1 (1959): 110-121. https://doi.org/10.1515/fabl.1959.2.1.110

External links[edit]

| The Sleeping Beauty | |

|---|---|

The prince finds the Sleeping Beauty, in deep slumber amidst the bushes. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Sleeping Beauty |

| Also known as | La Belle au bois dormant (The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods); Dornröschen (Little Briar Rose) |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 410 (Sleeping Beauty) |

| Region | France (1528) |

| Published in | Perceforest (1528) Pentamerone (1634), by Giambattista Basile Histoires ou contes du temps passé (1697), by Charles Perrault |

| Related | Sun, Moon and Talia |

Sleeping Beauty (French: La belle au bois dormant, or The Beauty in the Sleeping Forest; German: Dornröschen, or Little Briar Rose), also titled in English as The Sleeping Beauty in the Woods, is a fairy tale about a princess cursed by an evil fairy to sleep for a hundred years before being awoken by a handsome prince. A good fairy, knowing the princess would be frightened if alone when she wakes, uses her wand to put every living person and animal in the palace and forest asleep, to waken when the princess does.[1]

The earliest known version of the tale is found in the narrative Perceforest, written between 1330 and 1344. Another was published by Giambattista Basile in his collection titled The Pentamerone, published posthumously in 1634[2] and adapted by Charles Perrault in Histoires ou contes du temps passé in 1697. The version collected and printed by the Brothers Grimm was one orally transmitted from the Perrault.[3]

The Aarne-Thompson classification system for fairy tales lists Sleeping Beauty as a Type 410: it includes a princess who is magically forced into sleep and later woken, reversing the magic.[4] The fairy tale has been adapted countless times throughout history and retold by modern storytellers across a variety of media.

Origin[edit]

Early contributions to the tale include the medieval courtly romance Perceforest (published in 1528).[5] In this tale, a princess named Zellandine falls in love with a man named Troylus. Her father sends him to perform tasks to prove himself worthy of her, and while he is gone, Zellandine falls into an enchanted sleep. Troylus finds her and rapes her in her sleep; when their child is born, the child draws from her finger the flax that caused her sleep. She realizes from the ring Troylus left her that he was the father, and Troylus later returns to marry her.[6] Another early literary predecessor is the Provençal versified novel Fraire de Joi e sor de Plaser [ca] (c. 1320-1340).[7][8]

The second part of the Sleeping Beauty tale, in which the princess and her children are almost put to death but instead are hidden, may have been influenced by Genevieve of Brabant.[9] Even earlier influences come from the story of the sleeping Brynhild in the Volsunga saga and the tribulations of saintly female martyrs in early Christian hagiography conventions. Following these early renditions, the tale was first published by Italian poet Giambattista Basile who lived from 1575 to 1632.

Plot[edit]

The folktale begins with a princess whose parents are told by a wicked fairy that their daughter will die when she pricks her finger on a particular item. In Basile’s version, the princess pricks her finger on a piece of flax. In Perrault’s and the Grimm Brothers’ versions, the item is a spindle. The parents rid the kingdom of these items in the hopes of protecting their daughter, but the prophecy is fulfilled regardless. Instead of dying, as was foretold, the princess falls into a deep sleep. After some time, she is found by a prince and is awakened. In Giambattista Basile’s version of Sleeping Beauty, Sun, Moon, and Talia, the sleeping beauty, Talia, falls into a deep sleep after getting a splinter of flax in her finger. She is discovered in her castle by a wandering king, who «carrie[s] her to a bed, where he gather[s] the first fruits of love.»[10] He leaves her there and she later gives birth to twins.[11]

According to Maria Tatar, there are versions of the story that include a second part to the narrative that details the couple’s troubles after their union; some folklorists believe the two parts were originally separate tales.[12]

The second part begins after the prince and princess have had children. Through the course of the tale, the princess and her children are introduced in some way to another woman from the prince’s life. This other woman is not fond of the prince’s new family, and calls a cook to kill the children and serve them for dinner. Instead of obeying, the cook hides the children and serves livestock. Next, the other woman orders the cook to kill the princess. Before this can happen, the other woman’s true nature is revealed to the prince and then she is subjected to the very death that she had planned for the princess. The princess, prince, and their children live happily ever after.[13]

Basile’s narrative[edit]

In Giambattista Basile’s dark version of Sleeping Beauty, Sun, Moon, and Talia, the sleeping beauty is named Talia. By asking wise men and astrologers to predict her future after her birth, her father who is a great Lord learns that Talia will be in danger from a splinter of flax. The splinter later causes what appears to be Talia’s death; however, it is later learned that it is a long, deep sleep. After Talia falls into deep sleep, she is seated on a velvet throne and her father, to forget his misery of what he thinks is her death, closes the doors and abandons the house forever. One day, while a king is walking by, one of his falcons flies into the house. The king knocks, hoping to be let in by someone, but no one answers and he decides to climb in with a ladder. He finds Talia alive but unconscious, and «…gathers the first fruits of love.»[14] Afterwards, he leaves her in the bed and goes back to his kingdom. Though Talia is unconscious, she gives birth to twins — one of whom keeps sucking her fingers. Talia awakens because the twin has sucked out the flax that was stuck deep in Talia’s finger. When she wakes up, she discovers that she is a mother and has no idea what happened to her. One day, the king decides he wants to go see Talia again. He goes back to the palace to find her awake and a mother to his twins. He informs her of who he is, what has happened, and they end up bonding. After a few days, the king has to leave to go back to his realm, but promises Talia that he will return to take her to his kingdom.

When he arrives back in his kingdom, his wife hears him saying «Talia, Sun, and Moon» in his sleep. She bribes and threatens the king’s secretary to tell her what is going on. After the queen learns the truth, she pretends she is the king and writes to Talia asking her to send the twins because he wants to see them. Talia sends her twins to the «king» and the queen tells the cook to kill the twins and make dishes out of them. She wants to feed the king his children; instead, the cook takes the twins to his wife and hides them. He then cooks two lambs and serves them as if they were the twins. Every time the king mentions how good the food is, the queen replies, «Eat, eat, you are eating of your own.» Later, the queen invites Talia to the kingdom and is going to burn her alive, but the king appears and finds out what’s going on with his children and Talia. He then orders that his wife be burned along with those who betrayed him. Since the cook actually did not obey the queen, the king thanks the cook for saving his children by giving him rewards. The story ends with the king marrying Talia and living happily ever after.[10]

Perrault’s narrative[edit]

Perrault’s narrative is written in two parts, which some folklorists believe were originally separate tales, as they were in the Brothers Grimm’s version, and were later joined together by Giambattista Basile and once more by Perrault.[12] According to folklore editors Martin Hallett and Barbara Karasek, Perrault’s tale is a much more subtle and pared down version than Basile’s story in terms of the more immoral details. An example of this is depicted in Perrault’s tale by the prince’s choice to instigate no physical interaction with the sleeping princess when the prince discovers her.[2]

At the christening of a king and queen’s long-wished-for child, seven good fairies are invited to be godmothers to the infant princess. The fairies attend the banquet at the palace. Each fairy is presented with a golden plate and drinking cups adorned with jewels. Soon after, an old fairy enters the palace and is seated with a plate of fine china and a crystal drinking glass. This old fairy is overlooked because she has been within a tower for many years and everyone had believed her to be deceased. Six of the other seven fairies then offer their gifts of beauty, wit, grace, dance, song, and goodness to the infant princess. The evil fairy is very angry about having been forgotten, and as her gift, curses the infant princess so that she will one day prick her finger on a spindle of a spinning wheel and die. The seventh fairy, who has not yet given her gift, attempts to reverse the evil fairy’s curse. However, she can only do so partially. Instead of dying, the Princess will fall into a deep sleep for 100 years and be awakened by a king’s son («elle tombera seulement dans un profond sommeil qui durera cent ans, au bout desquels le fils d’un Roi viendra la réveiller«). This is her gift of protection.

The King orders that every spindle and spinning wheel in the kingdom be destroyed, to try to save his daughter from the terrible curse. Fifteen or sixteen years pass and one day, when the king and queen are away, the Princess wanders through the palace rooms and comes upon an old woman (implied to be the evil fairy in disguise), spinning with her spindle. The princess, who has never seen anyone spin before, asks the old woman if she can try the spinning wheel. The curse is fulfilled as the princess pricks her finger on the spindle and instantly falls into a deep sleep. The old woman cries for help and attempts are made to revive the princess. The king attributes this to fate and has the Princess carried to the finest room in the palace and placed upon a bed of gold and silver embroidered fabric. The king and queen kiss their daughter goodbye and depart, proclaiming the entrance to be forbidden. The good fairy who altered the evil prophecy is summoned. Having great powers of foresight, the fairy sees that the Princess will awaken to distress when she finds herself alone, so the fairy puts everyone in the castle to sleep. The fairy also summons a forest of trees, brambles and thorns that spring up around the castle, shielding it from the outside world and preventing anyone from disturbing the Princess.

A hundred years pass and a prince from another family spies the hidden castle during a hunting expedition. His attendants tell him differing stories regarding the castle until an old man recounts his father’s words: within the castle lies a beautiful princess who is doomed to sleep for a hundred years until a king’s son comes and awakens her. The prince then braves the tall trees, brambles and thorns which part at his approach, and enters the castle. He passes the sleeping castle folk and comes across the chamber where the Princess lies asleep on the bed. Struck by the radiant beauty before him, he falls on his knees before her. The enchantment comes to an end, the princess awakens and bestows upon the prince a look “more tender than a first glance might seem to warrant” (in Perrault’s original French tale, the prince does not kiss the princess to wake her up) then converses with the prince for a long time. Meanwhile, the rest of the castle awakens and go about their business. The prince and princess are later married by the chaplain in the castle chapel.

After wedding the Princess in secret, the Prince continues to visit her and she bears him two children, Aurore (Dawn) and Jour (Day), unbeknownst to his mother, who is of an ogre lineage. When the time comes for the Prince to ascend the throne, he brings his wife, children, and the talabutte («Count of the Mount»).

The Ogress Queen Mother sends the young Queen and the children to a house secluded in the woods and directs her cook to prepare the boy with Sauce Robert for dinner. The kind-hearted cook substitutes a lamb for the boy, which satisfies the Queen Mother. She then demands the girl but the cook this time substitutes a kid, which also satisfies the Queen Mother. When the Ogress demands that he serve up the young Queen, the latter offers to slit her throat so that she may join the children that she imagines are dead. While the Queen Mother is satisfied with a hind prepared with Sauce Robert in place of the young Queen, there is a tearful secret reunion of the Queen and her children. However, the Queen Mother soon discovers the cook’s trick and she prepares a tub in the courtyard filled with vipers and other noxious creatures. The King returns in the nick of time and the Ogress, her true nature having been exposed, throws herself into the tub and is fully consumed. The King, young Queen, and children then live happily ever after.

Grimm Brothers’ version[edit]

Sleeping Beauty and the palace dwellers under a century-long sleep enchantment (The Sleeping Beauty by Sir Edward Burne-Jones).

The Brothers Grimm included a variant of Sleeping Beauty, Little Briar Rose, in their collection (1812).[15] Their version ends when the prince arrives to wake Sleeping Beauty (named Rosamund) and does not include the part two as found in Basile’s and Perrault’s versions.[16] The brothers considered rejecting the story on the grounds that it was derived from Perrault’s version, but the presence of the Brynhild tale convinced them to include it as an authentically German tale. Their decision was notable because in none of the Teutonic myths, meaning the Poetic and Prose Eddas or Volsunga Saga, are their sleepers awakened with a kiss, a fact Jacob Grimm would have known since he wrote an encyclopedic volume on German mythology. His version is the only known German variant of the tale, and Perrault’s influence is almost certain.[17] In the original Brothers Grimm’s version, the fairies are instead wise women.[18]

The Brothers Grimm also included, in the first edition of their tales, a fragmentary fairy tale, «The Evil Mother-in-law». This story begins with the heroine, a married mother of two children, and her mother-in-law who attempts to eat her and the children. The heroine suggests an animal be substituted in the dish, and the story ends with the heroine’s worry that she cannot keep her children from crying and getting the mother-in-law’s attention. Like many German tales showing French influence, it appeared in no subsequent edition.[19]

Variations[edit]

He stands—he stoops to gaze—he kneels—he wakes her with a kiss, woodcut by Walter Crane

The princess’s name has varied from one adaptation to the other. In Sun, Moon, and Talia, she is named Talia (Sun and Moon being her twin children). She has no name in Perrault’s story but her daughter is called «Aurore». The Brothers Grimm named her «Briar Rose» in their 1812 collection.[15] However, some translations of the Grimms’ tale give the princess the name «Rosamond». Tchaikovsky’s ballet and Disney’s version named her Princess Aurora; however, in the Disney version, she is also called «Briar Rose» in her childhood, when she is being raised incognito by the good fairies.[20]

Besides Sun, Moon, and Talia, Basile included another variant of this Aarne-Thompson type, The Young Slave, in his book, The Pentamerone. The Grimms also included a second, more distantly related one titled The Glass Coffin.[21]

Italo Calvino included a variant in Italian Folktales. In his version, the cause of the princess’s sleep is a wish by her mother. As in Pentamerone, the prince rapes her in her sleep and her children are born. Calvino retains the element that the woman who tries to kill the children is the king’s mother, not his wife, but adds that she does not want to eat them herself, and instead serves them to the king. His version came from Calabria, but he noted that all Italian versions closely followed Basile’s.[22][23]

In his More English Fairy Tales, Joseph Jacobs noted that the figure of the Sleeping Beauty was in common between this tale and the Romani tale The King of England and his Three Sons.[24]

The hostility of the king’s mother to his new bride is repeated in the fairy tale The Six Swans,[25] and also features in The Twelve Wild Ducks, where the mother is modified to be the king’s stepmother. However, these tales omit the attempted cannibalism.

Russian Romantic writer Vasily Zhukovsky wrote a versified work based on the theme of the princess cursed into a long sleep in his poem «Спящая царевна» («The Sleeping Tsarevna» [ru]), published in 1832.[26]

Interpretations[edit]

According to Maria Tatar, the Sleeping Beauty tale has been disparaged by modern-day feminists who consider the protagonist to have no agency and find her passivity to be offensive; some feminists have even argued for people to stop telling the story altogether.[27]