Roman numerals on stern of the ship Cutty Sark showing draught in feet. The numbers range from 13 to 22, from bottom to top.

Roman numerals are a numeral system that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers are written with combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet, each letter with a fixed integer value, modern style uses only these seven:

| I | V | X | L | C | D | M |

| 1 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 500 | 1000 |

The use of Roman numerals continued long after the decline of the Roman Empire. From the 14th century on, Roman numerals began to be replaced by Arabic numerals; however, this process was gradual, and the use of Roman numerals persists in some applications to this day.

One place they are often seen is on clock faces. For instance, on the clock of Big Ben (designed in 1852), the hours from 1 to 12 are written as:

I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII

The notations IV and IX can be read as «one less than five» (4) and «one less than ten» (9), although there is a tradition favouring representation of «4» as «IIII» on Roman numeral clocks.[1]

Other common uses include year numbers on monuments and buildings and copyright dates on the title screens of movies and television programs. MCM, signifying «a thousand, and a hundred less than another thousand», means 1900, so 1912 is written MCMXII. For the years of this century, MM indicates 2000. The current year is MMXXIII (2023).

Description

Roman numerals use different symbols for each power of ten and no zero symbol, in contrast with the place value notation of Arabic numerals (in which place-keeping zeros enable the same digit to represent different powers of ten).

This allows some flexibility in notation, and there has never been an official or universally accepted standard for Roman numerals. Usage in ancient Rome varied greatly and became thoroughly chaotic in medieval times. Even the post-renaissance restoration of a largely «classical» notation has failed to produce total consistency: variant forms are even defended by some modern writers as offering improved «flexibility».[2] On the other hand, especially where a Roman numeral is considered a legally binding expression of a number, as in U.S. Copyright law (where an «incorrect» or ambiguous numeral may invalidate a copyright claim, or affect the termination date of the copyright period)[3] it is desirable to strictly follow the usual style described below.

Standard form

The following table displays how Roman numerals are usually written:[4]

| Thousands | Hundreds | Tens | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | C | X | I |

| 2 | MM | CC | XX | II |

| 3 | MMM | CCC | XXX | III |

| 4 | CD | XL | IV | |

| 5 | D | L | V | |

| 6 | DC | LX | VI | |

| 7 | DCC | LXX | VII | |

| 8 | DCCC | LXXX | VIII | |

| 9 | CM | XC | IX |

The numerals for 4 (IV) and 9 (IX) are written using «subtractive notation»,[5] where the first symbol (I) is subtracted from the larger one (V, or X), thus avoiding the clumsier IIII and VIIII.[a] Subtractive notation is also used for 40 (XL), 90 (XC), 400 (CD) and 900 (CM).[6] These are the only subtractive forms in standard use.

A number containing two or more decimal digits is built by appending the Roman numeral equivalent for each, from highest to lowest, as in the following examples:

- 39 = XXX + IX = XXXIX.

- 246 = CC + XL + VI = CCXLVI.

- 789 = DCC + LXXX + IX = DCCLXXXIX.

- 2,421 = MM + CD + XX + I = MMCDXXI.

Any missing place (represented by a zero in the place-value equivalent) is omitted, as in Latin (and English) speech:

- 160 = C + LX = CLX

- 207 = CC + VII = CCVII

- 1,009 = M + IX = MIX

- 1,066 = M + LX + VI = MLXVI[7][8]

In practice, Roman numerals for numbers over 1000 [b] are currently used mainly for year numbers, as in these examples:

- 1776 = M + DCC + LXX + VI = MDCCLXXVI (the date written on the book held by the Statue of Liberty).

- 1918 = M + CM + X + VIII = MCMXVIII (the first year of the Spanish flu pandemic)

- 1954 = M + CM + L + IV = MCMLIV (as in the trailer for the movie The Last Time I Saw Paris)[3]

- 2014 = MM + X + IV = MMXIV (the year of the games of the XXII (22nd) Olympic Winter Games (in Sochi, Russia))

The largest number that can be represented in this notation is 3,999 (MMMCMXCIX), but since the largest Roman numeral likely to be required today is MMXXIII (the current year) there is no practical need for larger Roman numerals. Prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals in the West, ancient and medieval users of the system used various means to write larger numbers; see large numbers below.

Other forms

Forms exist that vary in one way or another from the general standard represented above.

Other additive forms

While subtractive notation for 4, 40 and 400 (IV, XL and CD) has been the usual form since Roman times, additive notation to represent these numbers (IIII, XXXX and CCCC)[9] continued to be used, including in compound numbers like XXIIII,[10] LXXIIII,[11] and CCCCLXXXX.[12] The additive forms for 9, 90, and 900 (VIIII,[9] LXXXX,[13] and DCCCC[14]) have also been used, although less often.

The two conventions could be mixed in the same document or inscription, even in the same numeral. For example, on the numbered gates to the Colosseum, IIII is systematically used instead of IV, but subtractive notation is used for XL; consequently, gate 44 is labelled XLIIII.[15][16]

Modern clock faces that use Roman numerals still very often use IIII for four o’clock but IX for nine o’clock, a practice that goes back to very early clocks such as the Wells Cathedral clock of the late 14th century.[17][18][19] However, this is far from universal: for example, the clock on the Palace of Westminster tower (commonly known as Big Ben) uses a subtractive IV for 4 o’clock.[18]

Isaac Asimov once mentioned an «interesting theory» that Romans avoided using IV because it was the initial letters of IVPITER, the Latin spelling of Jupiter, and might have seemed impious.[20] He did not say whose theory it was.

The year number on Admiralty Arch, London. The year 1910 is rendered as

MDCCCCX, rather than the more usual

MCMX

Several monumental inscriptions created in the early 20th century use variant forms for «1900» (usually written MCM). These vary from MDCCCCX for 1910 as seen on Admiralty Arch, London, to the more unusual, if not unique MDCDIII for 1903, on the north entrance to the Saint Louis Art Museum.[21]

Especially on tombstones and other funerary inscriptions 5 and 50 have been occasionally written IIIII and XXXXX instead of V and L, and there are instances such as IIIIII and XXXXXX rather than VI or LX.[22][23]

Other subtractive forms

There is a common belief that any smaller digit placed to the left of a larger digit is subtracted from the total, and that by clever choices a long Roman numeral can be «compressed». The best known example of this is the ROMAN() function in Microsoft Excel, which can turn 499 into CDXCIX, LDVLIV, XDIX, VDIV, or ID depending on the «Form» setting.[24] There is no indication this is anything other than an invention by the programmer, and the universal-subtraction belief may be a result of modern users trying to rationalize the syntax of Roman numerals.

Epitaph of centurion Marcus Caelius, showing «

XIIX«

There is, however, some historic use of subtractive notation other than that described in the above «standard»: in particular IIIXX for 17,[25] IIXX for 18,[26] IIIC for 97,[27] IIC for 98,[28][29] and IC for 99.[30] A possible explanation is that the word for 18 in Latin is duodeviginti, literally «two from twenty», 98 is duodecentum (two from hundred), and 99 is undecentum (one from hundred).[31] However, the explanation does not seem to apply to IIIXX and IIIC, since the Latin words for 17 and 97 were septendecim (seven ten) and nonaginta septem (ninety seven), respectively.

There are multiple examples of IIX being used for 8. There does not seem to be a linguistic explanation for this use, although it is one stroke shorter than VIII. XIIX was used by officers of the XVIII Roman Legion to write their number.[32][33] The notation appears prominently on the cenotaph of their senior centurion Marcus Caelius (c. 45 BC – 9 AD). On the publicly displayed official Roman calendars known as Fasti, XIIX is used for the 18 days to the next Kalends, and XXIIX for the 28 days in February. The latter can be seen on the sole extant pre-Julian calendar, the Fasti Antiates Maiores.[34]

Rare variants

While irregular subtractive and additive notation has been used at least occasionally throughout history, some Roman numerals have been observed in documents and inscriptions that do not fit either system. Some of these variants do not seem to have been used outside specific contexts, and may have been regarded as errors even by contemporaries.

Padlock used on the north gate of the Irish town of Athlone. «1613» in the date is rendered

XVIXIII, (literally «16, 13») instead of

MDCXIII.

- IIXX was how people associated with the XXII Roman Legion used to write their number. The practice may have been due to a common way to say «twenty-second» in Latin, namely duo et vice(n)sima (literally «two and twentieth») rather than the «regular» vice(n)sima secunda (twenty second).[35] Apparently, at least one ancient stonecutter mistakenly thought that the IIXX of «22nd Legion» stood for 18, and «corrected» it to XVIII.[35]

- There are some examples of year numbers after 1000 written as two Roman numerals 1–99, e.g. 1613 as XVIXIII, corresponding to the common reading «sixteen thirteen» of such year numbers in English, or 1519 as XVCXIX as in French quinze-cent-dix-neuf (fifteen-hundred and nineteen), and similar readings in other languages.[37]

- In some French texts from the 15th century and later one finds constructions like IIIIXXXIX for 99, reflecting the French reading of that number as quatre-vingt-dix-neuf (four-score and nineteen).[37] Similarly, in some English documents one finds, for example, 77 written as «iiixxxvii» (which could be read «three-score and seventeen»).[38]

- A medieval accounting text from 1301 renders numbers like 13,573 as «XIII. M. V. C. III. XX. XIII«, that is, «13×1000 + 5×100 + 3×20 + 13».[39]

- Other numerals that do not fit the usual patterns – such as VXL for 45, instead of the usual XLV — may be due to scribal errors, or the writer’s lack of familiarity with the system, rather than being genuine variant usage.

Non-numeric combinations

As Roman numerals are composed of ordinary alphabetic characters, there may sometimes be confusion with other uses of the same letters. For example, «XXX» and «XL» have other connotations in addition to their values as Roman numerals, while «IXL» more often than not is a gramogram of «I excel», and is in any case not an unambiguous Roman numeral.[40]

Zero

As a non-positional numeral system, Roman numerals have no «place-keeping» zeros. Furthermore, the system as used by the Romans lacked a numeral for the number zero itself (that is, what remains after 1 is subtracted from 1). The word nulla (the Latin word meaning «none») was used to represent 0, although the earliest attested instances are medieval. For instance Dionysius Exiguus used nulla alongside Roman numerals in a manuscript from 525 AD.[41][42] About 725, Bede or one of his colleagues used the letter N, the initial of nulla or of nihil (the Latin word for «nothing») for 0, in a table of epacts, all written in Roman numerals.[43]

The use of N to indicate «none» long survived in the historic apothecaries’ system of measurement: used well into the 20th century to designate quantities in pharmaceutical prescriptions.[44]

Fractions

A triens coin (1⁄3 or

4⁄12 of an as). Note the four dots (····) indicating its value.

A semis coin (

1⁄2 or

6⁄12 of an as). Note the

S indicating its value.

The base «Roman fraction» is S, indicating 1⁄2.

The use of S (as in VIIS to indicate 71⁄2) is attested in some ancient inscriptions[45]

and also in the now rare apothecaries’ system (usually in the form SS):[44] but while Roman numerals for whole numbers are essentially decimal S does not correspond to 5⁄10, as one might expect, but 6⁄12.

The Romans used a duodecimal rather than a decimal system for fractions, as the divisibility of twelve (12 = 22 × 3) makes it easier to handle the common fractions of 1⁄3 and 1⁄4 than does a system based on ten (10 = 2 × 5). Notation for fractions other than 1⁄2 is mainly found on surviving Roman coins, many of which had values that were duodecimal fractions of the unit as. Fractions less than 1⁄2 are indicated by a dot (·) for each uncia «twelfth», the source of the English words inch and ounce; dots are repeated for fractions up to five twelfths. Six twelfths (one half), is S for semis «half». Uncia dots were added to S for fractions from seven to eleven twelfths, just as tallies were added to V for whole numbers from six to nine.[46] The arrangement of the dots was variable and not necessarily linear. Five dots arranged like (⁙) (as on the face of a die) are known as a quincunx, from the name of the Roman fraction/coin. The Latin words sextans and quadrans are the source of the English words sextant and quadrant.

Each fraction from 1⁄12 to 12⁄12 had a name in Roman times; these corresponded to the names of the related coins:

| Fraction | Roman numeral | Name (nominative and genitive) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1⁄12 | · | Uncia, unciae | «Ounce» |

| 2⁄12 = 1⁄6 | ·· or : | Sextans, sextantis | «Sixth» |

| 3⁄12 = 1⁄4 | ··· or ∴ | Quadrans, quadrantis | «Quarter» |

| 4⁄12 = 1⁄3 | ···· or ∷ | Triens, trientis | «Third» |

| 5⁄12 | ····· or ⁙ | Quincunx, quincuncis | «Five-ounce» (quinque unciae → quincunx) |

| 6⁄12 = 1⁄2 | S | Semis, semissis | «Half» |

| 7⁄12 | S· | Septunx, septuncis | «Seven-ounce» (septem unciae → septunx) |

| 8⁄12 = 2⁄3 | S·· or S: | Bes, bessis | «Twice» (as in «twice a third») |

| 9⁄12 = 3⁄4 | S··· or S∴ | Dodrans, dodrantis or nonuncium, nonuncii |

«Less a quarter» (de-quadrans → dodrans) or «ninth ounce» (nona uncia → nonuncium) |

| 10⁄12 = 5⁄6 | S···· or S∷ | Dextans, dextantis or decunx, decuncis |

«Less a sixth» (de-sextans → dextans) or «ten ounces» (decem unciae → decunx) |

| 11⁄12 | S····· or S⁙ | Deunx, deuncis | «Less an ounce» (de-uncia → deunx) |

| 12⁄12 = 1 | I | As, assis | «Unit» |

Other Roman fractional notations included the following:

| Fraction | Roman numeral | Name (nominative and genitive) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1⁄1728=12−3 | 𐆕 | Siliqua, siliquae | |

| 1⁄288 | ℈ | Scripulum, scripuli | «scruple» |

| 1⁄144=12−2 | 𐆔 | Dimidia sextula, dimidiae sextulae | «half a sextula» |

| 1⁄72 | 𐆓 | Sextula, sextulae | «1⁄6 of an uncia» |

| 1⁄48 | Ↄ | Sicilicus, sicilici | |

| 1⁄36 | 𐆓𐆓 | Binae sextulae, binarum sextularum | «two sextulas» (duella, duellae) |

| 1⁄24 | Σ or 𐆒 or Є | Semuncia, semunciae | «1⁄2 uncia» (semi- + uncia) |

| 1⁄8 | Σ· or 𐆒· or Є· | Sescuncia, sescunciae | «1+1⁄2 uncias» (sesqui- + uncia) |

Large numbers

During the centuries that Roman numerals remained the standard way of writing numbers throughout Europe, there were various extensions to the system designed to indicate larger numbers, none of which were ever standardised.

Apostrophus

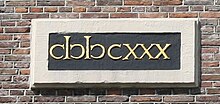

«1630» on the Westerkerk in Amsterdam. «

M» and «

D» are given archaic «apostrophus» form.

One of these was the apostrophus,[47] in which 500 was written as IↃ, while 1,000 was written as CIↃ.[20] This is a system of encasing numbers to denote thousands (imagine the Cs and Ↄs as parentheses), which has its origins in Etruscan numeral usage.

Each additional set of C and Ↄ surrounding CIↃ raises the value by a factor of ten: CCIↃↃ represents 10,000 and CCCIↃↃↃ represents 100,000. Similarly, each additional Ↄ to the right of IↃ raises the value by a factor of ten: IↃↃ represents 5,000 and IↃↃↃ represents 50,000. Numerals larger than CCCIↃↃↃ do not occur.[48]

Page from a 16th-century manual, showing a mixture of apostrophus and vinculum numbers (see in particular the ways of writing 10,000).

Sometimes CIↃ was reduced to ↀ for 1,000. Similarly, IↃↃ for 5,000 was reduced to ↁ; CCIↃↃ for 10,000 to ↂ; IↃↃↃ for 50,000 to ↇ (ↇ); and CCCIↃↃↃ (ↈ) for 100,000 to ↈ.

[49]

IↃ and CIↃ most likely preceded, and subsequently influenced, the adoption of «D» and «M» in Roman numerals.

John Wallis is often credited for introducing the symbol for infinity ⟨∞⟩, and one conjecture is that he based it on ↀ, since 1,000 was hyperbolically used to represent very large numbers.

Vinculum

Another system was the vinculum, in which conventional Roman numerals were multiplied by 1,000 by adding a «bar» or «overline».[49] It was a common alternative to the apostrophic ↀ during the Imperial era: both systems were in simultaneous use around the Roman world (M for ‘1000’ was not in use until the Medieval period).[50]

[51]

The use of vinculum for multiples of 1,000 can be observed, for example, on the milestones erected by Roman soldiers along the Antonine Wall in the mid-2nd century AD.[52] The vinculum for marking 1,000s continued in use in the Middle Ages, though it became known more commonly as titulus.[53]

Some modern sources describe the vinculum as if it were a part of the current «standard».[54] However, this is largely hypothetical, since no common modern usage requires numbers larger than the current year (MMXXIII). Nonetheless, here are some examples, to give an idea of how it might be used:

- IV = 4,000

- IVDCXXVII = 4,627

- XXV = 25,000

- XXVCDLIX = 25,459

Use of Roman numeral «

I» (with exaggerated serifs) contrasting with the upper case letter «I».

This use of lines is distinct from the custom, once very common, of adding both underline and overline (or very large serifs) to a Roman numeral, simply to make it clear that it is a number, e.g.

for 1967. There is some scope for confusion when an overline is meant to denote multiples of 1,000, and when not. The Greeks and Romans often overlined letters acting as numerals to highlight them from the general body of the text, without any numerical significance. This stylistic convention was, for example, also in use in the inscriptions of the Antonine Wall,[55] and the reader is required to decipher the intended meaning of the overline from the context.

Another medieval usage was the addition of vertical lines (or brackets) before and after the numeral to multiply it by 10:[citation needed] thus M for 10,000 as an alternative form for X. In combination with the overline the bracketed forms might be used to raise the multiplier to ten thousand, thus:

- VIII for 80,000

- XX for 200,000

This same syntax may also have indicated multiplication by 100[citation needed] so the above two examples are 800,000 and 2,000,000.

Origin

The system is closely associated with the ancient city-state of Rome and the Empire that it created. However, due to the scarcity of surviving examples, the origins of the system are obscure and there are several competing theories, all largely conjectural.

Etruscan numerals

Rome was founded sometime between 850 and 750 BC. At the time, the region was inhabited by diverse populations of which the Etruscans were the most advanced. The ancient Romans themselves admitted that the basis of much of their civilization was Etruscan. Rome itself was located next to the southern edge of the Etruscan domain, which covered a large part of north-central Italy.

The Roman numerals, in particular, are directly derived from the Etruscan number symbols: ⟨𐌠⟩, ⟨𐌡⟩, ⟨𐌢⟩, ⟨𐌣⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩ for 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 (They had more symbols for larger numbers, but it is unknown which symbol represents which number). As in the basic Roman system, the Etruscans wrote the symbols that added to the desired number, from higher to lower value. Thus the number 87, for example, would be written 50 + 10 + 10 + 10 + 5 + 1 + 1 = 𐌣𐌢𐌢𐌢𐌡𐌠𐌠 (this would appear as 𐌠𐌠𐌡𐌢𐌢𐌢𐌣 since Etruscan was written from right to left.)[56]

The symbols ⟨𐌠⟩ and ⟨𐌡⟩ resembled letters of the Etruscan alphabet, but ⟨𐌢⟩, ⟨𐌣⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩ did not. The Etruscans used the subtractive notation, too, but not like the Romans. They wrote 17, 18, and 19 as 𐌠𐌠𐌠𐌢𐌢, 𐌠𐌠𐌢𐌢, and 𐌠𐌢𐌢, mirroring the way they spoke those numbers («three from twenty», etc.); and similarly for 27, 28, 29, 37, 38, etc. However, they did not write 𐌠𐌡 for 4 (nor 𐌢𐌣 for 40), and wrote 𐌡𐌠𐌠, 𐌡𐌠𐌠𐌠 and 𐌡𐌠𐌠𐌠𐌠 for 7, 8, and 9, respectively.[56]

Early Roman numerals

The early Roman numerals for 1, 10, and 100 were the Etruscan ones: ⟨𐌠⟩, ⟨𐌢⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩. The symbols for 5 and 50 changed from ⟨𐌡⟩ and ⟨𐌣⟩ to ⟨V⟩ and ⟨ↆ⟩ at some point. The latter had flattened to ⟨⊥⟩ (an inverted T) by the time of Augustus, and soon afterwards became identified with the graphically similar letter ⟨L⟩.[48]

The symbol for 100 was written variously as ⟨𐌟⟩ or ⟨ↃIC⟩, and was then abbreviated to ⟨Ↄ⟩ or ⟨C⟩, with ⟨C⟩ (which matched the Latin letter C) finally winning out. It might have helped that C was the initial letter of CENTUM, Latin for «hundred».

The numbers 500 and 1000 were denoted by V or X overlaid with a box or circle. Thus 500 was like a Ↄ superimposed on a Þ. It became D or Ð by the time of Augustus, under the graphic influence of the letter D. It was later identified as the letter D; an alternative symbol for «thousand» was a CIↃ, and half of a thousand or «five hundred» is the right half of the symbol, IↃ, and this may have been converted into D.[20]

The notation for 1000 was a circled or boxed X: Ⓧ, ⊗, ⊕, and by Augustinian times was partially identified with the Greek letter Φ phi. Over time, the symbol changed to Ψ and ↀ. The latter symbol further evolved into ∞, then ⋈, and eventually changed to M under the influence of the Latin word mille «thousand».[48]

According to Paul Kayser, the basic numerical symbols were I, X, C and Φ (or ⊕) and the intermediate ones were derived by taking half of those (half an X is V, half a C is L and half a Φ/⊕ is D).[57]

Entrance to section

LII (52) of the Colosseum, with numerals still visible

Classical Roman numerals

The Colosseum was constructed in Rome in CE 72–80,[58] and while the original perimeter wall has largely disappeared, the numbered entrances from XXIII (23) to LIIII (54) survive,[59] to demonstrate that in Imperial times Roman numerals had already assumed their classical form: as largely standardised in current use. The most obvious anomaly (a common one that persisted for centuries) is the inconsistent use of subtractive notation — while XL is used for 40, IV is avoided in favour of IIII: in fact gate 44 is labelled XLIIII.

Use in the Middle Ages and Renaissance

Lower case, or minuscule, letters were developed in the Middle Ages, well after the demise of the Western Roman Empire, and since that time lower-case versions of Roman numbers have also been commonly used: i, ii, iii, iv, and so on.

13th century example of

iiij.

Since the Middle Ages, a «j» has sometimes been substituted for the final «i» of a «lower-case» Roman numeral, such as «iij» for 3 or «vij» for 7. This «j» can be considered a swash variant of «i«. Into the early 20th century, the use of a final «j» was still sometimes used in medical prescriptions to prevent tampering with or misinterpretation of a number after it was written.[60]

Numerals in documents and inscriptions from the Middle Ages sometimes include additional symbols, which today are called «medieval Roman numerals». Some simply substitute another letter for the standard one (such as «A» for «V«, or «Q» for «D«), while others serve as abbreviations for compound numerals («O» for «XI«, or «F» for «XL«). Although they are still listed today in some dictionaries, they are long out of use.[61]

| Number | Medieval abbreviation |

Notes and etymology |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | A | Resembles an upside-down V. Also said to equal 500. |

| 6 | ↅ | Either from a ligature of VI, or from digamma (ϛ), the Greek numeral 6 (sometimes conflated with the στ ligature).[48] |

| 7 | S, Z | Presumed abbreviation of septem, Latin for 7. |

| 9.5 | X̷ | Scribal abbreviation, an x with a slash through it. Likewise, IX̷ represented 8.5 |

| 11 | O | Presumed abbreviation of onze, French for 11. |

| 40 | F | Presumed abbreviation of English forty. |

| 70 | S | Also could stand for 7, with the same derivation. |

| 80 | R | |

| 90 | N | Presumed abbreviation of nonaginta, Latin for 90. (Ambiguous with N for «nothing» (nihil)). |

| 150 | Y | Possibly derived from the lowercase y’s shape. |

| 151 | K | Unusual, origin unknown; also said to stand for 250.[62] |

| 160 | T | Possibly derived from Greek tetra, as 4 × 40 = 160. |

| 200 | H | Could also stand for 2 (see also 𐆙, the symbol for the dupondius). From a barring of two I‘s. |

| 250 | E | |

| 300 | B | |

| 400 | P, G | |

| 500 | Q | Redundant with D; abbreviates quingenti, Latin for 500. Also sometimes used for 500,000.[63] |

| 800 | Ω | Borrowed from Gothic. |

| 900 | ϡ | Borrowed from Gothic. |

| 2000 | Z |

Chronograms, messages with dates encoded into them, were popular during the Renaissance era. The chronogram would be a phrase containing the letters I, V, X, L, C, D, and M. By putting these letters together, the reader would obtain a number, usually indicating a particular year.

Modern use

By the 11th century, Arabic numerals had been introduced into Europe from al-Andalus, by way of Arab traders and arithmetic treatises. Roman numerals, however, proved very persistent, remaining in common use in the West well into the 14th and 15th centuries, even in accounting and other business records (where the actual calculations would have been made using an abacus). Replacement by their more convenient «Arabic» equivalents was quite gradual, and Roman numerals are still used today in certain contexts. A few examples of their current use are:

Spanish Real using

IIII instead of

IV as regnal number of Charles

IV of Spain.

- Names of monarchs and popes, e.g. Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Pope Benedict XVI. These are referred to as regnal numbers and are usually read as ordinals; e.g. II is pronounced «the second». This tradition began in Europe sporadically in the Middle Ages, gaining widespread use in England during the reign of Henry VIII. Previously, the monarch was not known by numeral but by an epithet such as Edward the Confessor. Some monarchs (e.g. Charles IV of Spain and Louis XIV of France) seem to have preferred the use of IIII instead of IV on their coinage (see illustration).

- Generational suffixes, particularly in the U.S., for people sharing the same name across generations, for example William Howard Taft IV. These are also usually read as ordinals.

- In the French Republican Calendar, initiated during the French Revolution, years were numbered by Roman numerals – from the year I (1792) when this calendar was introduced to the year XIV (1805) when it was abandoned.

- The year of production of films, television shows and other works of art within the work itself. Outside reference to the work will use regular Arabic numerals.

The year of construction of the Cambridge Public Library, (USA) 1888, displayed in «standard» Roman numerals on its facade.

- Hour marks on timepieces. In this context, 4 is often written IIII.

- The year of construction on building façades and cornerstones.

- Page numbering of prefaces and introductions of books, and sometimes of appendices and annexes, too.

- Book volume and chapter numbers, as well as the several acts within a play (e.g. Act iii, Scene 2).

- Sequels to some films, video games, and other works (as in Rocky II, Grand Theft Auto V).

- Outlines that use numbers to show hierarchical relationships.

- Occurrences of a recurring grand event, for instance:

- The Summer and Winter Olympic Games (e.g. the XXI Olympic Winter Games; the Games of the XXX Olympiad).

- The Super Bowl, the annual championship game of the National Football League (e.g. Super Bowl XLII; Super Bowl 50 was a one-time exception[64]).

- WrestleMania, the annual professional wrestling event for the WWE (e.g. WrestleMania XXX). This usage has also been inconsistent.

Specific disciplines

In astronautics, United States rocket model variants are sometimes designated by Roman numerals, e.g. Titan I, Titan II, Titan III, Saturn I, Saturn V.

In astronomy, the natural satellites or «moons» of the planets are traditionally designated by capital Roman numerals appended to the planet’s name. For example, Titan’s designation is Saturn VI.

In chemistry, Roman numerals are often used to denote the groups of the periodic table. They are also used in the IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, for the oxidation number of cations which can take on several different positive charges. They are also used for naming phases of polymorphic crystals, such as ice.

In education, school grades (in the sense of year-groups rather than test scores) are sometimes referred to by a Roman numeral; for example, «grade IX» is sometimes seen for «grade 9».

In entomology, the broods of the thirteen and seventeen year periodical cicadas are identified by Roman numerals.

In graphic design stylised Roman numerals may represent numeric values.

In law, Roman numerals are commonly used to help organize legal codes as part of an alphanumeric outline.

In advanced mathematics (including trigonometry, statistics, and calculus), when a graph includes negative numbers, its quadrants are named using I, II, III, and IV. These quadrant names signify positive numbers on both axes, negative numbers on the X axis, negative numbers on both axes, and negative numbers on the Y axis, respectively. The use of Roman numerals to designate quadrants avoids confusion, since Arabic numerals are used for the actual data represented in the graph.

In military unit designation, Roman numerals are often used to distinguish between units at different levels. This reduces possible confusion, especially when viewing operational or strategic level maps. In particular, army corps are often numbered using Roman numerals (for example the American XVIII Airborne Corps or the WW2-era German III Panzerkorps) with Arabic numerals being used for divisions and armies.

In music, Roman numerals are used in several contexts:

- Movements are often numbered using Roman numerals.

- In Roman Numeral Analysis, harmonic function is identified using Roman Numerals.

- Individual strings of stringed instruments, such as the violin, are often denoted by Roman numerals, with higher numbers denoting lower strings.

In pharmacy, Roman numerals were used with the now largely obsolete apothecaries’ system of measurement: including SS to denote «one half» and N to denote «zero».[44][65]

In photography, Roman numerals (with zero) are used to denote varying levels of brightness when using the Zone System.

In seismology, Roman numerals are used to designate degrees of the Mercalli intensity scale of earthquakes.

In sport the team containing the «top» players and representing a nation or province, a club or a school at the highest level in (say) rugby union is often called the «1st XV«, while a lower-ranking cricket or American football team might be the «3rd XI«.

In tarot, Roman numerals (with zero) are used to denote the cards of the Major Arcana.

In theology and biblical scholarship, the Septuagint is often referred to as LXX, as this translation of the Old Testament into Greek is named for the legendary number of its translators (septuaginta being Latin for «seventy»).

Modern use in European languages other than English

Some uses that are rare or never seen in English speaking countries may be relatively common in parts of continental Europe and in other regions (e.g. Latin America) that use a European language other than English. For instance:

Capital or small capital Roman numerals are widely used in Romance languages to denote centuries, e.g. the French XVIIIe siècle[66] and the Spanish siglo XVIII mean «18th century». Slavic languages in and adjacent to Russia similarly favor Roman numerals (xviii век). On the other hand, in Slavic languages in Central Europe, like most Germanic languages, one writes «18.» (with a period) before the local word for «century».

Boris Yeltsin’s signature, dated 10 November 1988, rendered as 10.

XI.’88.

Mixed Roman and Arabic numerals are sometimes used in numeric representations of dates (especially in formal letters and official documents, but also on tombstones). The month is written in Roman numerals, while the day is in Arabic numerals: «4.VI.1789″ and «VI.4.1789″ both refer unambiguously to 4 June 1789.

Business hours table on a shop window in Vilnius, Lithuania.

Roman numerals are sometimes used to represent the days of the week in hours-of-operation signs displayed in windows or on doors of businesses,[67] and also sometimes in railway and bus timetables. Monday, taken as the first day of the week, is represented by I. Sunday is represented by VII. The hours of operation signs are tables composed of two columns where the left column is the day of the week in Roman numerals and the right column is a range of hours of operation from starting time to closing time. In the example case (left), the business opens from 10 AM to 7 PM on weekdays, 10 AM to 5 PM on Saturdays and is closed on Sundays. Note that the listing uses 24-hour time.

Sign at 17.9 km on route SS4 Salaria, north of Rome, Italy.

Roman numerals may also be used for floor numbering.[68][69] For instance, apartments in central Amsterdam are indicated as 138-III, with both an Arabic numeral (number of the block or house) and a Roman numeral (floor number). The apartment on the ground floor is indicated as 138-huis.

In Italy, where roads outside built-up areas have kilometre signs, major roads and motorways also mark 100-metre subdivisionals, using Roman numerals from I to IX for the smaller intervals. The sign IX/17 thus marks 17.9 km.

Certain romance-speaking countries use Roman numerals to designate assemblies of their national legislatures. For instance, the composition of the Italian Parliament from 2018 to 2022 (elected in the 2018 Italian general election) is called the XVIII Legislature of the Italian Republic (or more commonly the «XVIII Legislature»).

A notable exception to the use of Roman numerals in Europe is in Greece, where Greek numerals (based on the Greek alphabet) are generally used in contexts where Roman numerals would be used elsewhere.

Unicode

The «Number Forms» block of the Unicode computer character set standard has a number of Roman numeral symbols in the range of code points from U+2160 to U+2188.[70] This range includes both upper- and lowercase numerals, as well as pre-combined characters for numbers up to 12 (Ⅻ or XII). One justification for the existence of pre-combined numbers is to facilitate the setting of multiple-letter numbers (such as VIII) on a single horizontal line in Asian vertical text. The Unicode standard, however, includes special Roman numeral code points for compatibility only, stating that «[f]or most purposes, it is preferable to compose the Roman numerals from sequences of the appropriate Latin letters».[71]

The block also includes some apostrophus symbols for large numbers, an old variant of «L» (50) similar to the Etruscan character, the Claudian letter «reversed C», etc.

| Symbol | ↀ | ↁ | ↂ | ↅ | ↆ | ↇ | ↈ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1,000 | 5,000 | 10,000 | 6 | 50 | 50,000 | 100,000 |

See also

- Biquinary

- Egyptian numerals

- Etruscan numerals

- Greek numerals

- Hebrew numerals

- Kharosthi numerals

- Maya numerals

- Roman abacus

- Proto-writing

- Roman numerals in Unicode

References

Notes

- ^ Without theorising about causation, it may be noted that IV and IX not only have fewer characters than IIII and VIIII, but are less likely to be confused (especially at a quick glance) with III and VIII.

- ^ For numbers over 3,999 see large numbers

Citations

- ^ Judkins, Maura (4 November 2011). «Public clocks do a number on Roman numerals». The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

Most clocks using Roman numerals traditionally use IIII instead of IV… One of the rare prominent clocks that uses the IV instead of IIII is Big Ben in London.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (23 February 1990). «What is the proper way to style Roman numerals for the 1990s?». The Straight Dope.

- ^ a b Hayes, David P. «Guide to Roman Numerals». Copyright Registration and Renewal Information Chart and Web Site.

- ^ Reddy, Indra K.; Khan, Mansoor A. (2003). «1 (Working with Arabic and Roman numerals)». Essential Math and Calculations for Pharmacy Technicians. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-203-49534-6.

Table 1-1 Roman and Arabic numerals (table very similar to the table here, apart from inclusion of Vinculum notation.

- ^ Stanislas Dehaene (1997): The Number Sense : How the Mind Creates Mathematics. Oxford University Press; 288 pages. ISBN 9780199723096

- ^ Ûrij Vasilʹevič Prokhorov and Michiel Hazewinkel, editors (1990): Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Volume 10, page 502. Springer; 546 pages. ISBN 9781556080050

- ^ Dela Cruz, M. L. P.; Torres, H. D. (2009). Number Smart Quest for Mastery: Teacher’s Edition. Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 9789712352164.

- ^ Martelli, Alex; Ascher, David (2002). Python Cookbook. O’Reilly Media Inc. ISBN 978-0-596-00167-4.

- ^ a b Julius Caesar (52–49 BC): Commentarii de Bello Gallico. Book II, Section 4: «… XV milia Atrebates, Ambianos X milia, Morinos XXV milia, Menapios VII milia, Caletos X milia, Veliocasses et Viromanduos totidem, Atuatucos XVIIII milia; …» Section 8: «… ab utroque latere eius collis transversam fossam obduxit circiter passuum CCCC et ad extremas fossas castella constituit…» Book IV, Section 15: «Nostri ad unum omnes incolumes, perpaucis vulneratis, ex tanti belli timore, cum hostium numerus capitum CCCCXXX milium fuisset, se in castra receperunt.» Book VII, Section 4: «…in hiberna remissis ipse se recipit die XXXX Bibracte.»

- ^ Angelo Rocca (1612) De campanis commentarius. Published by Guillelmo Faciotti, Rome. Title of a Plate: «Campana a XXIIII hominibus pulsata» («Bell to be sounded by 24 men»).

- ^ Gerard Ter Borch (1673): Portrait of Cornelis de Graef. Date on painting: «Out. XXIIII Jaer. // M. DC. LXXIIII».

- ^ Pliny the Elder (77–79 AD): Naturalis Historia, Book III: «Saturni vocatur, Caesaream Mauretaniae urbem CCLXXXXVII p[assum]. traiectus. reliqua in ora flumen Tader … ortus in Cantabris haut procul oppido Iuliobrica, per CCCCL p. fluens …» Book IV: «Epiri, Achaiae, Atticae, Thessalia in porrectum longitudo CCCCLXXXX traditur, latitudo CCLXXXXVII.» Book VI: «tam vicinum Arsaniae fluere eum in regione Arrhene Claudius Caesar auctor est, ut, cum intumuere, confluant nec tamen misceantur leviorque Arsanias innatet MMMM ferme spatio, mox divisus in Euphraten mergatur.»

- ^ Thomas Bennet (1731): Grammatica Hebræa, cum uberrima praxi in usum tironum … Editio tertia. Published by T. Astley, copy in the British Library; 149 pages. Page 24: «PRÆFIXA duo sunt viz. He emphaticum vel relativum (de quo Cap VI Reg. LXXXX.) & Shin cum Segal sequente Dagesh, quod denotat pronomen relativum…»

- ^ Pico Della Mirandola (1486) Conclusiones sive Theses DCCCC («Conclusions, or 900 Theses»).

- ^ «360:12 tables, 24 chairs, and plenty of chalk». Roman Numerals…not quite so simple. 2 January 2011.

- ^ «Paul Lewis». Roman Numerals…How they work. 13 November 2021.

- ^ Milham, W.I. (1947). Time & Timekeepers. New York: Macmillan. p. 196.

- ^ a b Pickover, Clifford A. (2003). Wonders of Numbers: Adventures in Mathematics, Mind, and Meaning. Oxford University Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-19-534800-2.

- ^ Adams, Cecil; Zotti, Ed (1988). More of the straight dope. Ballantine Books. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-345-35145-6.

- ^ a b c Asimov, Isaac (1966). Asimov on Numbers (PDF). Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 12.

- ^ «Gallery: Museum’s North Entrance (1910)». Saint Louis Art Museum. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

The inscription over the North Entrance to the Museum reads: «Dedicated to Art and Free to All MDCDIII.» These roman numerals translate to 1903, indicating that the engraving was part of the original building designed for the 1904 World’s Fair.

- ^ Reynolds, Joyce Maire; Spawforth, Anthony J. S. (1996). «numbers, Roman». In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Anthony (eds.). Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- ^ Kennedy, Benjamin Hall (1923). The Revised Latin Primer. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- ^ «ROMAN function». support.microsoft.com.

- ^ Michaele Gasp. Lvndorphio (1621): Acta publica inter invictissimos gloriosissimosque&c. … et Ferdinandum II. Romanorum Imperatores…. Printed by Ian-Friderici Weissii. Page 123: «Sub Dato Pragæ IIIXX Decemb. A. C. M. DC. IIXX». Page 126, end of the same document: «Dabantur Pragæ 17 Decemb. M. DC. IIXX».

- ^ Raphael Sulpicius à Munscrod (1621): Vera Ac Germana Detecto Clandestinarvm Deliberationvm. Page 16, line 1: «repertum Originale Subdatum IIIXXX Aug. A. C. MDC.IIXX». Page 41, upper right corner: «Decemb. A. C. MDC.IIXX». Page 42, upper left corner: «Febr. A. C. MDC.XIX». Page 70: «IIXX. die Maij sequentia in consilio noua ex Bohemia allata….». Page 71: «XIX. Maij».

- ^ Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel (1699): Als Ihre Königl. Majestät in Pohlen und …. Page 39: «… und der Umschrifft: LITHUANIA ASSERTA M. DC. IIIC [1699].»

- ^ Joh. Caspar Posner (1698): Mvndvs ante mvndvm sive De Chao Orbis Primordio, title page: «Ad diem jvlii A. O. R. M DC IIC».

- ^ Wilhelm Ernst Tentzel (1700): Saxonia Nvmismatica: Das ist: Die Historie Des Durchlauchtigsten…. Page 26: «Die Revers hat eine feine Inscription: SERENISSIMO DN.DN… SENATUS.QVERNF. A. M DC IIC D. 18 OCT [year 1698 day 18 oct].»

- ^ Enea Silvio Piccolomini (1698): Opera Geographica et Historica. Helmstadt, J. M. Sustermann. Title page of first edition: «Bibliopolæ ibid. M DC IC».

- ^ Kennedy, Benjamin H. (1879). Latin grammar. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 150. ISBN 9781177808293.

- ^ Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A (2004). Handbook to life in ancient Rome (2 ed.). p. 270. ISBN 0-8160-5026-0.

- ^ Boyne, William (1968). A manual of Roman coins. p. 13.

- ^ Degrassi, Atilius, ed. (1963). Inscriptiones Italiae. Vol. 13: Fasti et Elogia. Rome: Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato. Fasciculus 2: Fasti anni Numani et Iuliani.

- ^ a b Stephen James Malone, (2005) Legio XX Valeria Victrix…. PhD thesis. On page 396 it discusses many coins with «Leg. IIXX» and notes that it must be Legion 22. The footnote on that page says: «The form IIXX clearly reflecting the Latin duo et vicensima ‘twenty-second’: cf. X5398, legatus I[eg II] I et vicensim(ae) Pri[mi]g; VI 1551, legatus leg] IIXX Prj; III 14207.7, miles leg IIXX; and III 10471-3, a vexillation drawn from four German legions including ‘XVIII PR’ – surely here the stonecutter’s hypercorrection for IIXX PR.

- ^ L’ Atre périlleux et Yvain, le chevalier au lion . 1301–1350.

- ^ a b M. Gachard (1862): «II. Analectes historiques, neuvième série (nos CCLXI-CCLXXXIV)». Bulletin de la Commission royale d’Historie, volume 3, pages 345–554. Page 347: Lettre de Philippe le Beau aux échevins…, quote: «Escript en nostre ville de Gand, le XXIIIIme de febvrier, l’an IIIIXXXIX [quatre-vingt-dix-neuf = 99].» Page 356: Lettre de l’achiduchesse Marguerite au conseil de Brabant…, quote: «… Escript à Bruxelles, le dernier jour de juing anno XVcXIX [1519].» Page 374: Letters patentes de la rémission … de la ville de Bruxelles, quote: «… Op heden, tweentwintich [‘twenty-two’] daegen in decembri, anno vyfthien hondert tweendertich [‘fifteen hundred thirty-two’] … Gegeven op ten vyfsten dach in deser jegewoirdige maent van decembri anno XV tweendertich [1532] vorschreven.» Page 419: Acte du duc de Parme portant approbation…, quote»: «Faiet le XVme de juillet XVc huytante-six [1586].» doi:10.3406/bcrh.1862.3033.

- ^ Herbert Edward Salter (1923) Registrum Annalium Collegii Mertonensis 1483–1521 Oxford Historical Society, volume 76; 544 pages. Page 184 has the computation in pounds:shillings:pence (li:s:d) x:iii:iiii + xxi:viii:viii + xlv:xiiii:i = iiixxxvii:vi:i, i.e. 10:3:4 + 21:8:8 + 45:14:1 = 77:6:1.

- ^ Johannis de Sancto Justo (1301): «E Duo Codicibus Ceratis» («From Two Texts in Wax»). In de Wailly, Delisle (1865): Contenant la deuxieme livraison des monumens des regnes de saint Louis,… Volume 22 of Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France. Page 530: «SUMMA totalis, XIII. M. V. C. III. XX. XIII. l. III s. XI d. [Sum total, 13 thousand 5 hundred 3 score 13 livres, 3 sous, 11 deniers].

- ^ «Our Brand Story». SPC Ardmona. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ^ Faith Wallis, trans. Bede: The Reckoning of Time (725), Liverpool, Liverpool Univ. Pr., 2004. ISBN 0-85323-693-3.

- ^ Byrhtferth’s Enchiridion (1016). Edited by Peter S. Baker and Michael Lapidge. Early English Text Society 1995. ISBN 978-0-19-722416-8.

- ^ C. W. Jones, ed., Opera Didascalica, vol. 123C in Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina.

- ^ a b c Bachenheimer, Bonnie S. (2010). Manual for Pharmacy Technicians. ISBN 978-1-58528-307-1.

- ^ «RIB 2208. Distance Slab of the Sixth Legion». Roman Inscriptions in Britain. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Maher, David W.; Makowski, John F., «Literary Evidence for Roman Arithmetic with Fractions Archived 27 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine», Classical Philology 96 (2011): 376–399.

- ^ «Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary».

- ^ a b c d Perry, David J. Proposal to Add Additional Ancient Roman Characters to UCS Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Ifrah, Georges (2000). The Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer. Translated by David Bellos, E. F. Harding, Sophie Wood, Ian Monk. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Chrisomalis, Stephen (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–109. ISBN 978-0-521-87818-0.

- ^ Gordon, Arthur E. (1982). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 0-520-05079-7.

- ^ «RIB 2208. Distance Slab of the Twentieth Legion». Roman Inscriptions in Britain. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ Chrisomalis, Stephen (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-521-87818-0.

- ^ «What is Vinculum Notation?». Numerals Converter. 4 March 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ «RIB 2171. Building Inscription of the Second and Twentieth Legions». Roman Inscriptions in Britain. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ a b Gilles Van Heems (2009)> «Nombre, chiffre, lettre : Formes et réformes. Des notations chiffrées de l’étrusque» («Between Numbers and Letters: About Etruscan Notations of Numeral Sequences»). Revue de philologie, de littérature et d’histoire anciennes, volume LXXXIII (83), issue 1, pages 103–130. ISSN 0035-1652.

- ^ Keyser, Paul (1988). «The Origin of the Latin Numerals 1 to 1000». American Journal of Archaeology. 92 (4): 529–546. doi:10.2307/505248. JSTOR 505248. S2CID 193086234.

- ^ Hopkins, Keith (2005). The Colosseum. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01895-2.

- ^ Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (First ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-288003-1.

- ^ Bastedo, Walter A. Materia Medica: Pharmacology, Therapeutics and Prescription Writing for Students and Practitioners, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders, 1919) p582. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ Capelli, A. Dictionary of Latin Abbreviations. 1912.

- ^ Bang, Jørgen. Fremmedordbog, Berlingske Ordbøger, 1962 (Danish)

- ^ Gordon, Arthur E. (1983). Illustrated Introduction to Latin Epigraphy. University of California Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780520038981. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ NFL won’t use Roman numerals for Super Bowl 50 Archived 1 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Football League. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Reddy, Indra K.; Khan, Mansoor A. (2003). Essential Math and Calculations for Pharmacy Technicians. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-203-49534-6.

- ^ Lexique des règles typographiques en usage à l’imprimerie nationale (in French) (6th ed.). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. March 2011. p. 126. ISBN 978-2-7433-0482-9. On composera en chiffres romains petites capitales les nombres concernant : ↲ 1. Les siècles.

- ^ Beginners latin Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Roman Arithmetic Archived 22 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Southwestern Adventist University. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Roman Numerals History Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ «Unicode Number Forms» (PDF).

- ^ «The Unicode Standard, Version 6.0 – Electronic edition» (PDF). Unicode, Inc. 2011. p. 486.

Sources

- Menninger, Karl (1992). Number Words and Number Symbols: A Cultural History of Numbers. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-27096-8.

Further reading

- Aczel, Amir D. 2015. Finding Zero: A Mathematician’s Odyssey to Uncover the Origins of Numbers. 1st edition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Goines, David Lance. A Constructed Roman Alphabet: A Geometric Analysis of the Greek and Roman Capitals and of the Arabic Numerals. Boston: D.R. Godine, 1982.

- Houston, Stephen D. 2012. The Shape of Script: How and Why Writing Systems Change. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Taisbak, Christian M. 1965. «Roman numerals and the abacus.» Classica et medievalia 26: 147–60.

External links

- «Roman Numerals (Totally Epic Guide)». Know The Romans.

Roman numerals on stern of the ship Cutty Sark showing draught in feet. The numbers range from 13 to 22, from bottom to top.

Roman numerals are a numeral system that originated in ancient Rome and remained the usual way of writing numbers throughout Europe well into the Late Middle Ages. Numbers are written with combinations of letters from the Latin alphabet, each letter with a fixed integer value, modern style uses only these seven:

| I | V | X | L | C | D | M |

| 1 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 500 | 1000 |

The use of Roman numerals continued long after the decline of the Roman Empire. From the 14th century on, Roman numerals began to be replaced by Arabic numerals; however, this process was gradual, and the use of Roman numerals persists in some applications to this day.

One place they are often seen is on clock faces. For instance, on the clock of Big Ben (designed in 1852), the hours from 1 to 12 are written as:

I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII

The notations IV and IX can be read as «one less than five» (4) and «one less than ten» (9), although there is a tradition favouring representation of «4» as «IIII» on Roman numeral clocks.[1]

Other common uses include year numbers on monuments and buildings and copyright dates on the title screens of movies and television programs. MCM, signifying «a thousand, and a hundred less than another thousand», means 1900, so 1912 is written MCMXII. For the years of this century, MM indicates 2000. The current year is MMXXIII (2023).

Description

Roman numerals use different symbols for each power of ten and no zero symbol, in contrast with the place value notation of Arabic numerals (in which place-keeping zeros enable the same digit to represent different powers of ten).

This allows some flexibility in notation, and there has never been an official or universally accepted standard for Roman numerals. Usage in ancient Rome varied greatly and became thoroughly chaotic in medieval times. Even the post-renaissance restoration of a largely «classical» notation has failed to produce total consistency: variant forms are even defended by some modern writers as offering improved «flexibility».[2] On the other hand, especially where a Roman numeral is considered a legally binding expression of a number, as in U.S. Copyright law (where an «incorrect» or ambiguous numeral may invalidate a copyright claim, or affect the termination date of the copyright period)[3] it is desirable to strictly follow the usual style described below.

Standard form

The following table displays how Roman numerals are usually written:[4]

| Thousands | Hundreds | Tens | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | C | X | I |

| 2 | MM | CC | XX | II |

| 3 | MMM | CCC | XXX | III |

| 4 | CD | XL | IV | |

| 5 | D | L | V | |

| 6 | DC | LX | VI | |

| 7 | DCC | LXX | VII | |

| 8 | DCCC | LXXX | VIII | |

| 9 | CM | XC | IX |

The numerals for 4 (IV) and 9 (IX) are written using «subtractive notation»,[5] where the first symbol (I) is subtracted from the larger one (V, or X), thus avoiding the clumsier IIII and VIIII.[a] Subtractive notation is also used for 40 (XL), 90 (XC), 400 (CD) and 900 (CM).[6] These are the only subtractive forms in standard use.

A number containing two or more decimal digits is built by appending the Roman numeral equivalent for each, from highest to lowest, as in the following examples:

- 39 = XXX + IX = XXXIX.

- 246 = CC + XL + VI = CCXLVI.

- 789 = DCC + LXXX + IX = DCCLXXXIX.

- 2,421 = MM + CD + XX + I = MMCDXXI.

Any missing place (represented by a zero in the place-value equivalent) is omitted, as in Latin (and English) speech:

- 160 = C + LX = CLX

- 207 = CC + VII = CCVII

- 1,009 = M + IX = MIX

- 1,066 = M + LX + VI = MLXVI[7][8]

In practice, Roman numerals for numbers over 1000 [b] are currently used mainly for year numbers, as in these examples:

- 1776 = M + DCC + LXX + VI = MDCCLXXVI (the date written on the book held by the Statue of Liberty).

- 1918 = M + CM + X + VIII = MCMXVIII (the first year of the Spanish flu pandemic)

- 1954 = M + CM + L + IV = MCMLIV (as in the trailer for the movie The Last Time I Saw Paris)[3]

- 2014 = MM + X + IV = MMXIV (the year of the games of the XXII (22nd) Olympic Winter Games (in Sochi, Russia))

The largest number that can be represented in this notation is 3,999 (MMMCMXCIX), but since the largest Roman numeral likely to be required today is MMXXIII (the current year) there is no practical need for larger Roman numerals. Prior to the introduction of Arabic numerals in the West, ancient and medieval users of the system used various means to write larger numbers; see large numbers below.

Other forms

Forms exist that vary in one way or another from the general standard represented above.

Other additive forms

While subtractive notation for 4, 40 and 400 (IV, XL and CD) has been the usual form since Roman times, additive notation to represent these numbers (IIII, XXXX and CCCC)[9] continued to be used, including in compound numbers like XXIIII,[10] LXXIIII,[11] and CCCCLXXXX.[12] The additive forms for 9, 90, and 900 (VIIII,[9] LXXXX,[13] and DCCCC[14]) have also been used, although less often.

The two conventions could be mixed in the same document or inscription, even in the same numeral. For example, on the numbered gates to the Colosseum, IIII is systematically used instead of IV, but subtractive notation is used for XL; consequently, gate 44 is labelled XLIIII.[15][16]

Modern clock faces that use Roman numerals still very often use IIII for four o’clock but IX for nine o’clock, a practice that goes back to very early clocks such as the Wells Cathedral clock of the late 14th century.[17][18][19] However, this is far from universal: for example, the clock on the Palace of Westminster tower (commonly known as Big Ben) uses a subtractive IV for 4 o’clock.[18]

Isaac Asimov once mentioned an «interesting theory» that Romans avoided using IV because it was the initial letters of IVPITER, the Latin spelling of Jupiter, and might have seemed impious.[20] He did not say whose theory it was.

The year number on Admiralty Arch, London. The year 1910 is rendered as

MDCCCCX, rather than the more usual

MCMX

Several monumental inscriptions created in the early 20th century use variant forms for «1900» (usually written MCM). These vary from MDCCCCX for 1910 as seen on Admiralty Arch, London, to the more unusual, if not unique MDCDIII for 1903, on the north entrance to the Saint Louis Art Museum.[21]

Especially on tombstones and other funerary inscriptions 5 and 50 have been occasionally written IIIII and XXXXX instead of V and L, and there are instances such as IIIIII and XXXXXX rather than VI or LX.[22][23]

Other subtractive forms

There is a common belief that any smaller digit placed to the left of a larger digit is subtracted from the total, and that by clever choices a long Roman numeral can be «compressed». The best known example of this is the ROMAN() function in Microsoft Excel, which can turn 499 into CDXCIX, LDVLIV, XDIX, VDIV, or ID depending on the «Form» setting.[24] There is no indication this is anything other than an invention by the programmer, and the universal-subtraction belief may be a result of modern users trying to rationalize the syntax of Roman numerals.

Epitaph of centurion Marcus Caelius, showing «

XIIX«

There is, however, some historic use of subtractive notation other than that described in the above «standard»: in particular IIIXX for 17,[25] IIXX for 18,[26] IIIC for 97,[27] IIC for 98,[28][29] and IC for 99.[30] A possible explanation is that the word for 18 in Latin is duodeviginti, literally «two from twenty», 98 is duodecentum (two from hundred), and 99 is undecentum (one from hundred).[31] However, the explanation does not seem to apply to IIIXX and IIIC, since the Latin words for 17 and 97 were septendecim (seven ten) and nonaginta septem (ninety seven), respectively.

There are multiple examples of IIX being used for 8. There does not seem to be a linguistic explanation for this use, although it is one stroke shorter than VIII. XIIX was used by officers of the XVIII Roman Legion to write their number.[32][33] The notation appears prominently on the cenotaph of their senior centurion Marcus Caelius (c. 45 BC – 9 AD). On the publicly displayed official Roman calendars known as Fasti, XIIX is used for the 18 days to the next Kalends, and XXIIX for the 28 days in February. The latter can be seen on the sole extant pre-Julian calendar, the Fasti Antiates Maiores.[34]

Rare variants

While irregular subtractive and additive notation has been used at least occasionally throughout history, some Roman numerals have been observed in documents and inscriptions that do not fit either system. Some of these variants do not seem to have been used outside specific contexts, and may have been regarded as errors even by contemporaries.

Padlock used on the north gate of the Irish town of Athlone. «1613» in the date is rendered

XVIXIII, (literally «16, 13») instead of

MDCXIII.

- IIXX was how people associated with the XXII Roman Legion used to write their number. The practice may have been due to a common way to say «twenty-second» in Latin, namely duo et vice(n)sima (literally «two and twentieth») rather than the «regular» vice(n)sima secunda (twenty second).[35] Apparently, at least one ancient stonecutter mistakenly thought that the IIXX of «22nd Legion» stood for 18, and «corrected» it to XVIII.[35]

- There are some examples of year numbers after 1000 written as two Roman numerals 1–99, e.g. 1613 as XVIXIII, corresponding to the common reading «sixteen thirteen» of such year numbers in English, or 1519 as XVCXIX as in French quinze-cent-dix-neuf (fifteen-hundred and nineteen), and similar readings in other languages.[37]

- In some French texts from the 15th century and later one finds constructions like IIIIXXXIX for 99, reflecting the French reading of that number as quatre-vingt-dix-neuf (four-score and nineteen).[37] Similarly, in some English documents one finds, for example, 77 written as «iiixxxvii» (which could be read «three-score and seventeen»).[38]

- A medieval accounting text from 1301 renders numbers like 13,573 as «XIII. M. V. C. III. XX. XIII«, that is, «13×1000 + 5×100 + 3×20 + 13».[39]

- Other numerals that do not fit the usual patterns – such as VXL for 45, instead of the usual XLV — may be due to scribal errors, or the writer’s lack of familiarity with the system, rather than being genuine variant usage.

Non-numeric combinations

As Roman numerals are composed of ordinary alphabetic characters, there may sometimes be confusion with other uses of the same letters. For example, «XXX» and «XL» have other connotations in addition to their values as Roman numerals, while «IXL» more often than not is a gramogram of «I excel», and is in any case not an unambiguous Roman numeral.[40]

Zero

As a non-positional numeral system, Roman numerals have no «place-keeping» zeros. Furthermore, the system as used by the Romans lacked a numeral for the number zero itself (that is, what remains after 1 is subtracted from 1). The word nulla (the Latin word meaning «none») was used to represent 0, although the earliest attested instances are medieval. For instance Dionysius Exiguus used nulla alongside Roman numerals in a manuscript from 525 AD.[41][42] About 725, Bede or one of his colleagues used the letter N, the initial of nulla or of nihil (the Latin word for «nothing») for 0, in a table of epacts, all written in Roman numerals.[43]

The use of N to indicate «none» long survived in the historic apothecaries’ system of measurement: used well into the 20th century to designate quantities in pharmaceutical prescriptions.[44]

Fractions

A triens coin (1⁄3 or

4⁄12 of an as). Note the four dots (····) indicating its value.

A semis coin (

1⁄2 or

6⁄12 of an as). Note the

S indicating its value.

The base «Roman fraction» is S, indicating 1⁄2.

The use of S (as in VIIS to indicate 71⁄2) is attested in some ancient inscriptions[45]

and also in the now rare apothecaries’ system (usually in the form SS):[44] but while Roman numerals for whole numbers are essentially decimal S does not correspond to 5⁄10, as one might expect, but 6⁄12.

The Romans used a duodecimal rather than a decimal system for fractions, as the divisibility of twelve (12 = 22 × 3) makes it easier to handle the common fractions of 1⁄3 and 1⁄4 than does a system based on ten (10 = 2 × 5). Notation for fractions other than 1⁄2 is mainly found on surviving Roman coins, many of which had values that were duodecimal fractions of the unit as. Fractions less than 1⁄2 are indicated by a dot (·) for each uncia «twelfth», the source of the English words inch and ounce; dots are repeated for fractions up to five twelfths. Six twelfths (one half), is S for semis «half». Uncia dots were added to S for fractions from seven to eleven twelfths, just as tallies were added to V for whole numbers from six to nine.[46] The arrangement of the dots was variable and not necessarily linear. Five dots arranged like (⁙) (as on the face of a die) are known as a quincunx, from the name of the Roman fraction/coin. The Latin words sextans and quadrans are the source of the English words sextant and quadrant.

Each fraction from 1⁄12 to 12⁄12 had a name in Roman times; these corresponded to the names of the related coins:

| Fraction | Roman numeral | Name (nominative and genitive) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1⁄12 | · | Uncia, unciae | «Ounce» |

| 2⁄12 = 1⁄6 | ·· or : | Sextans, sextantis | «Sixth» |

| 3⁄12 = 1⁄4 | ··· or ∴ | Quadrans, quadrantis | «Quarter» |

| 4⁄12 = 1⁄3 | ···· or ∷ | Triens, trientis | «Third» |

| 5⁄12 | ····· or ⁙ | Quincunx, quincuncis | «Five-ounce» (quinque unciae → quincunx) |

| 6⁄12 = 1⁄2 | S | Semis, semissis | «Half» |

| 7⁄12 | S· | Septunx, septuncis | «Seven-ounce» (septem unciae → septunx) |

| 8⁄12 = 2⁄3 | S·· or S: | Bes, bessis | «Twice» (as in «twice a third») |

| 9⁄12 = 3⁄4 | S··· or S∴ | Dodrans, dodrantis or nonuncium, nonuncii |

«Less a quarter» (de-quadrans → dodrans) or «ninth ounce» (nona uncia → nonuncium) |

| 10⁄12 = 5⁄6 | S···· or S∷ | Dextans, dextantis or decunx, decuncis |

«Less a sixth» (de-sextans → dextans) or «ten ounces» (decem unciae → decunx) |

| 11⁄12 | S····· or S⁙ | Deunx, deuncis | «Less an ounce» (de-uncia → deunx) |

| 12⁄12 = 1 | I | As, assis | «Unit» |

Other Roman fractional notations included the following:

| Fraction | Roman numeral | Name (nominative and genitive) | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1⁄1728=12−3 | 𐆕 | Siliqua, siliquae | |

| 1⁄288 | ℈ | Scripulum, scripuli | «scruple» |

| 1⁄144=12−2 | 𐆔 | Dimidia sextula, dimidiae sextulae | «half a sextula» |

| 1⁄72 | 𐆓 | Sextula, sextulae | «1⁄6 of an uncia» |

| 1⁄48 | Ↄ | Sicilicus, sicilici | |

| 1⁄36 | 𐆓𐆓 | Binae sextulae, binarum sextularum | «two sextulas» (duella, duellae) |

| 1⁄24 | Σ or 𐆒 or Є | Semuncia, semunciae | «1⁄2 uncia» (semi- + uncia) |

| 1⁄8 | Σ· or 𐆒· or Є· | Sescuncia, sescunciae | «1+1⁄2 uncias» (sesqui- + uncia) |

Large numbers

During the centuries that Roman numerals remained the standard way of writing numbers throughout Europe, there were various extensions to the system designed to indicate larger numbers, none of which were ever standardised.

Apostrophus

«1630» on the Westerkerk in Amsterdam. «

M» and «

D» are given archaic «apostrophus» form.

One of these was the apostrophus,[47] in which 500 was written as IↃ, while 1,000 was written as CIↃ.[20] This is a system of encasing numbers to denote thousands (imagine the Cs and Ↄs as parentheses), which has its origins in Etruscan numeral usage.

Each additional set of C and Ↄ surrounding CIↃ raises the value by a factor of ten: CCIↃↃ represents 10,000 and CCCIↃↃↃ represents 100,000. Similarly, each additional Ↄ to the right of IↃ raises the value by a factor of ten: IↃↃ represents 5,000 and IↃↃↃ represents 50,000. Numerals larger than CCCIↃↃↃ do not occur.[48]

Page from a 16th-century manual, showing a mixture of apostrophus and vinculum numbers (see in particular the ways of writing 10,000).

Sometimes CIↃ was reduced to ↀ for 1,000. Similarly, IↃↃ for 5,000 was reduced to ↁ; CCIↃↃ for 10,000 to ↂ; IↃↃↃ for 50,000 to ↇ (ↇ); and CCCIↃↃↃ (ↈ) for 100,000 to ↈ.

[49]

IↃ and CIↃ most likely preceded, and subsequently influenced, the adoption of «D» and «M» in Roman numerals.

John Wallis is often credited for introducing the symbol for infinity ⟨∞⟩, and one conjecture is that he based it on ↀ, since 1,000 was hyperbolically used to represent very large numbers.

Vinculum

Another system was the vinculum, in which conventional Roman numerals were multiplied by 1,000 by adding a «bar» or «overline».[49] It was a common alternative to the apostrophic ↀ during the Imperial era: both systems were in simultaneous use around the Roman world (M for ‘1000’ was not in use until the Medieval period).[50]

[51]

The use of vinculum for multiples of 1,000 can be observed, for example, on the milestones erected by Roman soldiers along the Antonine Wall in the mid-2nd century AD.[52] The vinculum for marking 1,000s continued in use in the Middle Ages, though it became known more commonly as titulus.[53]

Some modern sources describe the vinculum as if it were a part of the current «standard».[54] However, this is largely hypothetical, since no common modern usage requires numbers larger than the current year (MMXXIII). Nonetheless, here are some examples, to give an idea of how it might be used:

- IV = 4,000

- IVDCXXVII = 4,627

- XXV = 25,000

- XXVCDLIX = 25,459

Use of Roman numeral «

I» (with exaggerated serifs) contrasting with the upper case letter «I».

This use of lines is distinct from the custom, once very common, of adding both underline and overline (or very large serifs) to a Roman numeral, simply to make it clear that it is a number, e.g.

for 1967. There is some scope for confusion when an overline is meant to denote multiples of 1,000, and when not. The Greeks and Romans often overlined letters acting as numerals to highlight them from the general body of the text, without any numerical significance. This stylistic convention was, for example, also in use in the inscriptions of the Antonine Wall,[55] and the reader is required to decipher the intended meaning of the overline from the context.

Another medieval usage was the addition of vertical lines (or brackets) before and after the numeral to multiply it by 10:[citation needed] thus M for 10,000 as an alternative form for X. In combination with the overline the bracketed forms might be used to raise the multiplier to ten thousand, thus:

- VIII for 80,000

- XX for 200,000

This same syntax may also have indicated multiplication by 100[citation needed] so the above two examples are 800,000 and 2,000,000.

Origin

The system is closely associated with the ancient city-state of Rome and the Empire that it created. However, due to the scarcity of surviving examples, the origins of the system are obscure and there are several competing theories, all largely conjectural.

Etruscan numerals

Rome was founded sometime between 850 and 750 BC. At the time, the region was inhabited by diverse populations of which the Etruscans were the most advanced. The ancient Romans themselves admitted that the basis of much of their civilization was Etruscan. Rome itself was located next to the southern edge of the Etruscan domain, which covered a large part of north-central Italy.

The Roman numerals, in particular, are directly derived from the Etruscan number symbols: ⟨𐌠⟩, ⟨𐌡⟩, ⟨𐌢⟩, ⟨𐌣⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩ for 1, 5, 10, 50, and 100 (They had more symbols for larger numbers, but it is unknown which symbol represents which number). As in the basic Roman system, the Etruscans wrote the symbols that added to the desired number, from higher to lower value. Thus the number 87, for example, would be written 50 + 10 + 10 + 10 + 5 + 1 + 1 = 𐌣𐌢𐌢𐌢𐌡𐌠𐌠 (this would appear as 𐌠𐌠𐌡𐌢𐌢𐌢𐌣 since Etruscan was written from right to left.)[56]

The symbols ⟨𐌠⟩ and ⟨𐌡⟩ resembled letters of the Etruscan alphabet, but ⟨𐌢⟩, ⟨𐌣⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩ did not. The Etruscans used the subtractive notation, too, but not like the Romans. They wrote 17, 18, and 19 as 𐌠𐌠𐌠𐌢𐌢, 𐌠𐌠𐌢𐌢, and 𐌠𐌢𐌢, mirroring the way they spoke those numbers («three from twenty», etc.); and similarly for 27, 28, 29, 37, 38, etc. However, they did not write 𐌠𐌡 for 4 (nor 𐌢𐌣 for 40), and wrote 𐌡𐌠𐌠, 𐌡𐌠𐌠𐌠 and 𐌡𐌠𐌠𐌠𐌠 for 7, 8, and 9, respectively.[56]

Early Roman numerals

The early Roman numerals for 1, 10, and 100 were the Etruscan ones: ⟨𐌠⟩, ⟨𐌢⟩, and ⟨𐌟⟩. The symbols for 5 and 50 changed from ⟨𐌡⟩ and ⟨𐌣⟩ to ⟨V⟩ and ⟨ↆ⟩ at some point. The latter had flattened to ⟨⊥⟩ (an inverted T) by the time of Augustus, and soon afterwards became identified with the graphically similar letter ⟨L⟩.[48]

The symbol for 100 was written variously as ⟨𐌟⟩ or ⟨ↃIC⟩, and was then abbreviated to ⟨Ↄ⟩ or ⟨C⟩, with ⟨C⟩ (which matched the Latin letter C) finally winning out. It might have helped that C was the initial letter of CENTUM, Latin for «hundred».

The numbers 500 and 1000 were denoted by V or X overlaid with a box or circle. Thus 500 was like a Ↄ superimposed on a Þ. It became D or Ð by the time of Augustus, under the graphic influence of the letter D. It was later identified as the letter D; an alternative symbol for «thousand» was a CIↃ, and half of a thousand or «five hundred» is the right half of the symbol, IↃ, and this may have been converted into D.[20]

The notation for 1000 was a circled or boxed X: Ⓧ, ⊗, ⊕, and by Augustinian times was partially identified with the Greek letter Φ phi. Over time, the symbol changed to Ψ and ↀ. The latter symbol further evolved into ∞, then ⋈, and eventually changed to M under the influence of the Latin word mille «thousand».[48]

According to Paul Kayser, the basic numerical symbols were I, X, C and Φ (or ⊕) and the intermediate ones were derived by taking half of those (half an X is V, half a C is L and half a Φ/⊕ is D).[57]

Entrance to section

LII (52) of the Colosseum, with numerals still visible

Classical Roman numerals

The Colosseum was constructed in Rome in CE 72–80,[58] and while the original perimeter wall has largely disappeared, the numbered entrances from XXIII (23) to LIIII (54) survive,[59] to demonstrate that in Imperial times Roman numerals had already assumed their classical form: as largely standardised in current use. The most obvious anomaly (a common one that persisted for centuries) is the inconsistent use of subtractive notation — while XL is used for 40, IV is avoided in favour of IIII: in fact gate 44 is labelled XLIIII.

Use in the Middle Ages and Renaissance

Lower case, or minuscule, letters were developed in the Middle Ages, well after the demise of the Western Roman Empire, and since that time lower-case versions of Roman numbers have also been commonly used: i, ii, iii, iv, and so on.

13th century example of

iiij.

Since the Middle Ages, a «j» has sometimes been substituted for the final «i» of a «lower-case» Roman numeral, such as «iij» for 3 or «vij» for 7. This «j» can be considered a swash variant of «i«. Into the early 20th century, the use of a final «j» was still sometimes used in medical prescriptions to prevent tampering with or misinterpretation of a number after it was written.[60]

Numerals in documents and inscriptions from the Middle Ages sometimes include additional symbols, which today are called «medieval Roman numerals». Some simply substitute another letter for the standard one (such as «A» for «V«, or «Q» for «D«), while others serve as abbreviations for compound numerals («O» for «XI«, or «F» for «XL«). Although they are still listed today in some dictionaries, they are long out of use.[61]

| Number | Medieval abbreviation |

Notes and etymology |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | A | Resembles an upside-down V. Also said to equal 500. |

| 6 | ↅ | Either from a ligature of VI, or from digamma (ϛ), the Greek numeral 6 (sometimes conflated with the στ ligature).[48] |

| 7 | S, Z | Presumed abbreviation of septem, Latin for 7. |

| 9.5 | X̷ | Scribal abbreviation, an x with a slash through it. Likewise, IX̷ represented 8.5 |

| 11 | O | Presumed abbreviation of onze, French for 11. |

| 40 | F | Presumed abbreviation of English forty. |

| 70 | S | Also could stand for 7, with the same derivation. |

| 80 | R | |

| 90 | N | Presumed abbreviation of nonaginta, Latin for 90. (Ambiguous with N for «nothing» (nihil)). |

| 150 | Y | Possibly derived from the lowercase y’s shape. |

| 151 | K | Unusual, origin unknown; also said to stand for 250.[62] |

| 160 | T | Possibly derived from Greek tetra, as 4 × 40 = 160. |

| 200 | H | Could also stand for 2 (see also 𐆙, the symbol for the dupondius). From a barring of two I‘s. |

| 250 | E | |

| 300 | B | |

| 400 | P, G | |

| 500 | Q | Redundant with D; abbreviates quingenti, Latin for 500. Also sometimes used for 500,000.[63] |

| 800 | Ω | Borrowed from Gothic. |

| 900 | ϡ | Borrowed from Gothic. |

| 2000 | Z |

Chronograms, messages with dates encoded into them, were popular during the Renaissance era. The chronogram would be a phrase containing the letters I, V, X, L, C, D, and M. By putting these letters together, the reader would obtain a number, usually indicating a particular year.

Modern use

By the 11th century, Arabic numerals had been introduced into Europe from al-Andalus, by way of Arab traders and arithmetic treatises. Roman numerals, however, proved very persistent, remaining in common use in the West well into the 14th and 15th centuries, even in accounting and other business records (where the actual calculations would have been made using an abacus). Replacement by their more convenient «Arabic» equivalents was quite gradual, and Roman numerals are still used today in certain contexts. A few examples of their current use are:

Spanish Real using

IIII instead of

IV as regnal number of Charles

IV of Spain.

- Names of monarchs and popes, e.g. Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Pope Benedict XVI. These are referred to as regnal numbers and are usually read as ordinals; e.g. II is pronounced «the second». This tradition began in Europe sporadically in the Middle Ages, gaining widespread use in England during the reign of Henry VIII. Previously, the monarch was not known by numeral but by an epithet such as Edward the Confessor. Some monarchs (e.g. Charles IV of Spain and Louis XIV of France) seem to have preferred the use of IIII instead of IV on their coinage (see illustration).

- Generational suffixes, particularly in the U.S., for people sharing the same name across generations, for example William Howard Taft IV. These are also usually read as ordinals.

- In the French Republican Calendar, initiated during the French Revolution, years were numbered by Roman numerals – from the year I (1792) when this calendar was introduced to the year XIV (1805) when it was abandoned.

- The year of production of films, television shows and other works of art within the work itself. Outside reference to the work will use regular Arabic numerals.

The year of construction of the Cambridge Public Library, (USA) 1888, displayed in «standard» Roman numerals on its facade.