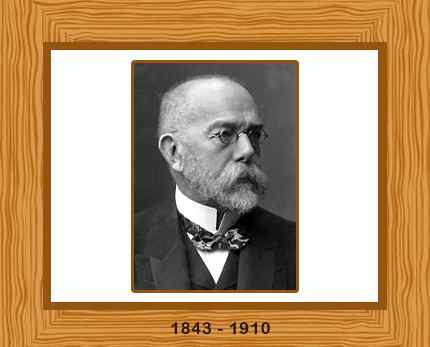

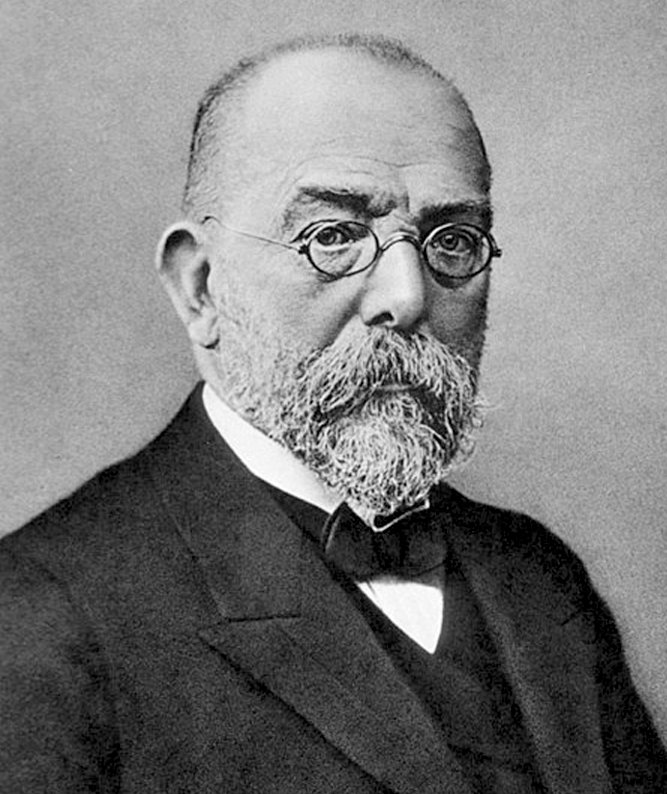

Prussian physician Robert Koch is best known for isolating the bacterium which causes tuberculosis, the cause of numerous deaths in the mid-19th century.

Who Was Robert Koch?

Physician Robert Koch is best known for isolating the tuberculosis bacterium, the cause of numerous deaths in the mid-19th century. He won the Nobel Prize in 1905 for his work. He is considered one of the founders of microbiology and developed criteria, named Koch’s postulates, that were meant to help establish a causal relationship between a microbe and a disease.

Bacterial Discoveries

Robert Koch has been celebrated for his research into the causes of notable diseases and presenting solutions to safeguard public health:

Anthrax

While employed in private practice as a physician in Wollstein, Koch set to work on identifying the root cause of the anthrax that had felled livestock in the region. By inoculating healthy animals with infected

tissue, he determined the ideal environment for the anthrax bacillus to spread, including transmission through soil by spores. Koch became the first to link a specific bacterium with a specific

disease, propelling him to fame with the publication of his findings in 1876.

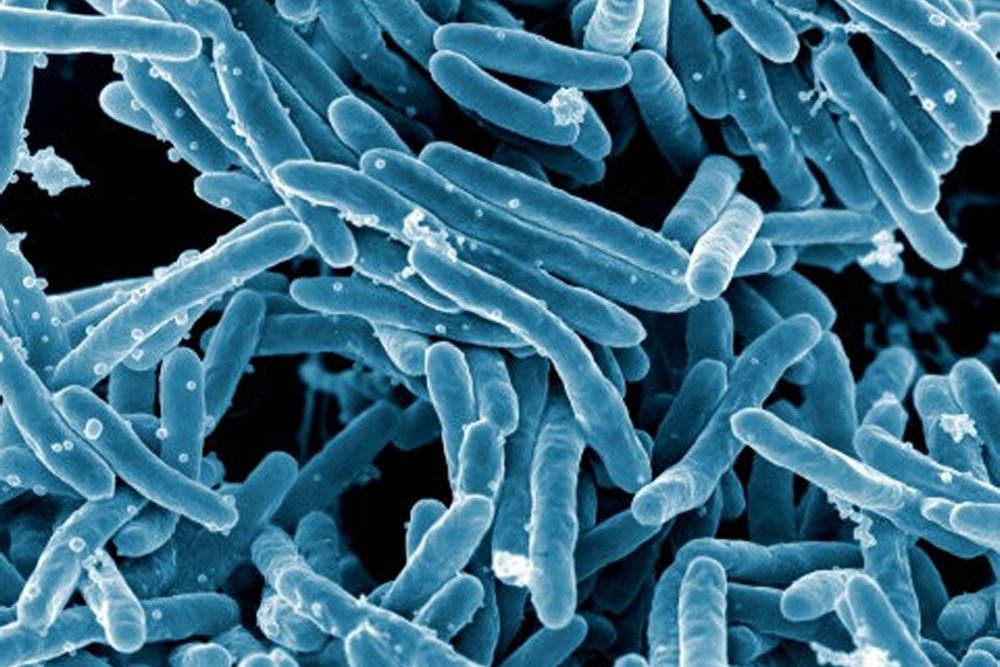

Tuberculosis

After moving to the the Imperial Health Office in Berlin, Koch began his work on discovery of the tubercle bacillus. He painstakingly tried out different stains to reveal the nature of the bacteria,

as well as the ideal media in which to grow colonies for study. Inoculating more than 200 animals with bacilli from pure cultures, he determined that sputum was the principal source of the

disease’s transmission, requiring the sterilization of clothes and bed sheets from infected patients.

Koch’s presentation of his findings, at a meeting of the Berlin Physiological Society in 1882, is considered a watershed moment in medical history. In 1905, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in

Medicine for his work in helping to curb the spread of the deadly disease.

Cholera

Following his resounding success with TB, Koch was sent to Egypt and Calcutta, India, to investigate the outbreak of cholera in those areas. He identified the bacillus and its characteristics,

though its nature as a human-borne disease made it difficult to test his research on animals. Nevertheless, Koch determined that contaminated drinking water was the primary culprit behind the

spread of the disease. He again targeted drinking water as the source of an 1892 outbreak in Germany, leading to a renewed focus on that area of public health.

Pioneering Methodology

Along with his discovery of certain bacteria, Robert Koch pioneered new techniques for conducting laboratory research. He experimented with different dyes for observing bacteria and

collaborated with microscope developers to foster improved resolution, becoming the first physician to use an oil immersion lens and a condenser.

Realizing that solid media was better than liquid for the development of pure cultures, Koch conducted his groundbreaking research on tuberculosis by growing bacterial colonies on sliced

potatoes. He later found improved media for his experiments, with one assistant, Walther Hesse, discovering the favorable properties of agar, and another, Julius Petri, introducing his easy-to-use

Petri dish.

Koch’s Postulates

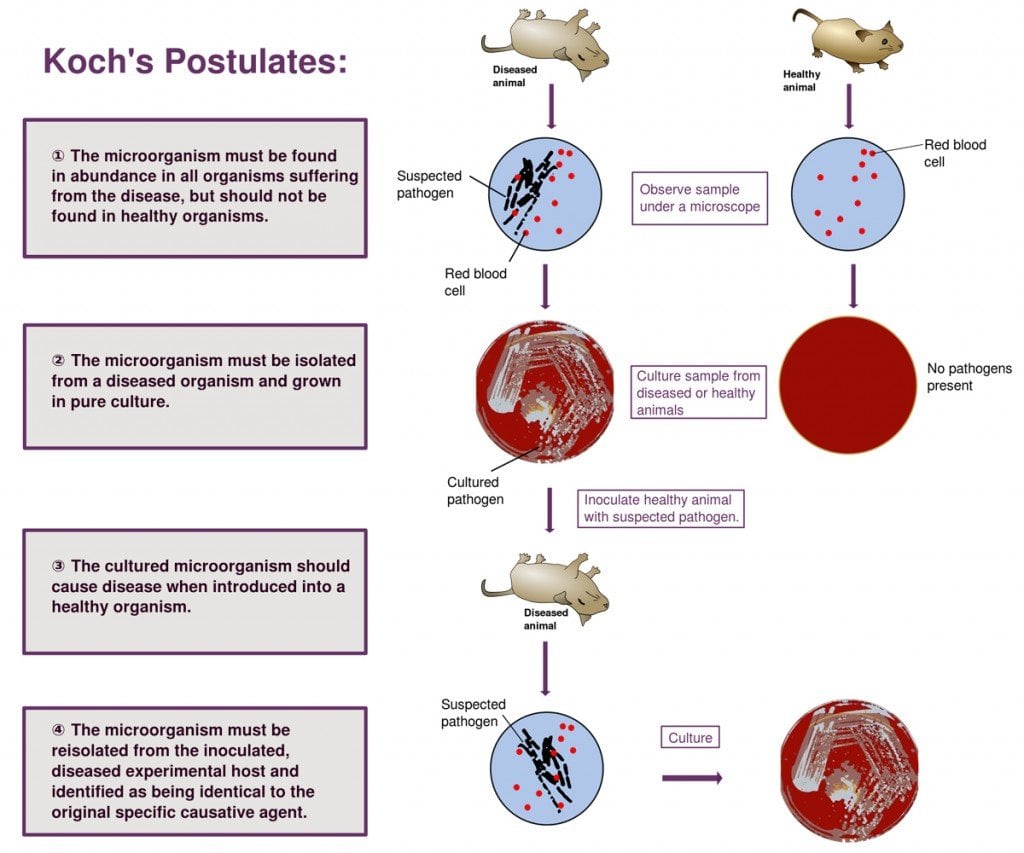

By the 1880s, Koch formed a checklist of conditions to be satisfied for specific bacteria to be accepted as the cause of specific diseases:

1. The microorganism or other pathogen must be present in all cases of the disease, and not in healthy animals.

2. The pathogen must be isolated from the diseased host and grown in pure culture.

3. The pathogen from the pure culture must cause the disease when inoculated into a healthy animal.

Scroll to Continue

4. The pathogen must be reisolated from the new host and shown to be the same as the originally inoculated pathogen.

These postulates were formally approved by the Great Powers in Dresden in 1893.

Early Life and Career

Robert Heinrich Hermann Koch was born on December 11, 1843, in Clausthal, Germany. The son of a mining engineer, he demonstrated a gifted mind at an early age, reportedly announcing to

his parents at age 5 that he had taught himself to read by using newspapers.

In 1862, Koch enrolled at the University of Gottingen to study medicine. Among his influential professors was Jacob Henle, a leading anatomist and proponent of the germ theory of disease.

After earning his medical degree in 1866, Koch worked as a hospital assistant. He passed the district medical officer’s examination, and by 1870 he began volunteering for medical service in the

Franco-Prussian war. In 1872, he became district medical officer for Wollstein, where he began compiling the research on bacteria that would make him famous.

Tubercilin and Bovine TB Missteps

In 1890, Koch announced that he had developed a cure for tuberculosis, called tubercilin. This prompted patients and physicians alike to travel to Berlin, and for Koch to take on a new role as

director of the new Institute for Infectious Diseases. However, the so-called cure was soon revealed to have little therapeutic value, damaging Koch’s reputation in the medical

community.

In 1901, Koch attended the International Tuberculosis Congress in Washington, D.C., where he argued that bovine tuberculosis was of a separate nature from the form that afflicted humans and

as such was relatively harmless to men. While correct that the bacilli causing bovine TB was different, he was ultimately proven wrong in his belief that it had little effect on humans and that no

public measures were needed to purge infected livestock.

Later Travels and Death

Long harboring a love for travel, Koch spent much of the remaining 15 years of his life visting foreign countries to embark on new research. In the late 1890s he traveled to Rhodesia (South

Africa) to help stem an outbreak of rinderpest, and he followed with stops in other parts of Africa and India to study malaria, surra and other diseases.

After stepping down as director of the Institute for Infectious Disease — later renamed the Koch Institute — in 1904, Koch returned to Africa to study trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) and

visited relatives in the U.S. He died of heart disease on May 27, 1910, in Baden-Baden, Germany.

Legacy

One of the founders of microbiology, Koch helped usher in a «golden age» of scientific discovery which uncovered the principal bacterial pathogens behind many of the deadliest diseases known

to mankind, and directly prompted the implementation of life-saving public health measures. Additionally, his postulates and laboratory techniques served as a bedrock for medicinal

developments that lasted well into the 20th century.

Koch’s most influential scientific papers were finally published in English in 1987, and the following year, Thomas Brock delivered an acclaimed biography, Robert Koch: A Life in Medicine and

Bacteriology.

On December 10, 2017, Google celebrated the 112th anniversary of Koch’s Nobel Prize win with one of its celebrated «Google Doodles.»

Text B.Robert Koch

Robert Koch is a prominent German bacteriologist,the founder of modern microbiology.He was born in 1843,died in 1910.When Koch became a doctor he carried on many experiments on mice(мышах)in a small laboratory.In 1882 Koch discovered tuberculosis bacilli.In his report made in the Berlin Physiological Society Koch described in detail the morphology of tuberculosis bacilli and the ways to reveal them.

Due to his discovery Koch became known all over the world.In 1884 Koch published his book on cholera.This book included the investigations of his research work carried out during the cholera epidemic in Egypt and India.From the intestines of the men with cholera Koch isolated a small comma-shaped (в виде запятой)bacterium.He determined that these bacteria spread through drinking water.In 19905 Koch got the Nobel prize for his important scientific discoveries.

Роберт Кох — известный немецкий бактериолог, основоположник современной микробиологии. Он родился в 1843 году, умер в 1910 году. Когда Кох стал врачом, он провел множество экспериментов на мышах (мышах) в небольшой лаборатории. В 1882 году Кох открыл туберкулезную палочку. В своем докладе, сделанном в Берлинском физиологическом обществе, Кох подробно описал морфологию туберкулезных бацилл и способы их выявления.

Благодаря своему открытию Кох стал известен во всем мире. В 1884

году Кох опубликовал свою книгу о холере, в которую вошли

исследования его исследовательской работы, проведенной во

время эпидемии холеры в Египте и Индии. Из кишечника больных

холерой Кох. изолировал небольшую бактерию в форме запятой (в

виде запятой). Он определил, что эти бактерии распространяются

через питьевую воду. В 19905 году Кох получил Нобелевскую

премию за свои важные научные открытия.

Соседние файлы в предмете Английский язык

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

|

Robert Koch |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch 11 December 1843 Clausthal, Kingdom of Hanover, German Confederation |

| Died | 27 May 1910 (aged 66)

Baden-Baden, Grand Duchy of Baden, German Empire |

| Nationality | German |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen |

| Known for | Bacterial culture method Koch’s postulates Germ theory Discovery of anthrax bacillus Discovery of tuberculosis bacillus Discovery of cholera bacillus |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Microbiology |

| Institutions | Imperial Health Office, Berlin University of Berlin |

| Doctoral advisor | Georg Meissner |

| Other academic advisors | Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle Karl Ewald Hasse Rudolf Virchow |

| Influenced | Friedrich Loeffler |

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( KOKH,[1][2] German: [ˈʁoːbɛʁt ˈkɔx] (listen); 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the bacterium itself was discovered by Filippo Pacini in 1854), and anthrax, he is regarded as one of the main founders of modern bacteriology. As such he is popularly nicknamed the father of microbiology (with Louis Pasteur[3]), and as the father of medical bacteriology.[4][5] His discovery of the anthrax bacterium (Bacillus anthracis) in 1876 is considered as the birth of modern bacteriology.[6] His discoveries directly provided proofs for the germ theory of diseases, and the scientific basis of public health.[7]

While working as a private physician, Koch developed many innovative techniques in microbiology. He was the first to use the oil immersion lens, condenser, and microphotography in microscopy. His invention of the bacterial culture method using agar and glass plates (later developed as the Petri dish by his assistant Julius Richard Petri) made him the first to grow bacteria in the laboratory. In appreciation of his work, he was appointed to government advisor at the Imperial Health Office in 1880, promoted to a senior executive position (Geheimer Regierungsrat) in 1882, Director of Hygienic Institute and Chair (Professor of hygiene) of the Faculty of Medicine at Berlin University in 1885, and the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases (later renamed Robert Koch Institute after his death) in 1891.

The methods Koch used in bacteriology led to establishment of a medical concept known as Koch’s postulates, four generalized medical principles to ascertain the relationship of pathogens with specific diseases. The concept is still in use in most situations and influences subsequent epidemiological principles such as the Bradford Hill criteria.[8] A major controversy followed when Koch discovered tuberculin as a medication for tuberculosis which was proven to be ineffective, but developed for diagnosis of tuberculosis after his death. For his research on tuberculosis, he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905.[9] The day he announced the discovery of the tuberculosis bacterium, 24 March, has been observed by the World Health Organization as «World Tuberculosis Day» every year since 1982.

Early life and education[edit]

Koch was born in Clausthal, Germany, on 11 December 1843, to Hermann Koch (1814–1877) and Mathilde Julie Henriette (née Biewend; 1818–1871).[10] His father was a mining engineer. He was the third of thirteen siblings.[11] He excelled academically from an early age. Before entering school in 1848, he had taught himself how to read and write.[12] He completed secondary education in 1862, having excelled in science and math.[13]

At the age of 19, in 1862, Koch entered the University of Göttingen to study natural science.[14] He took up mathematics, physics and botany. He was appointed assistant in the university’s Pathological Museum.[15] After three semesters, he decided to change his area of study to medicine, as he aspired to be a physician. During his fifth semester at the medical school, Jacob Henle, an anatomist who had published a theory of contagion in 1840, asked him to participate in his research project on uterine nerve structure. This research won him a research prize from the university and enabled him to briefly study under Rudolf Virchow, who was at the time considered as «Germany’s most renowned physician.»[11] In his sixth semester, Koch began to research at the Physiological Institute, where he studied the secretion of succinic acid, which is a signaling molecule that is also involved in the metabolism of the mitochondria. This would eventually form the basis of his dissertation.[9] In January 1866, he graduated from the medical school, earning honours of the highest distinction, maxima cum laude.[16][17]

Career[edit]

After graduation in 1866, Koch briefly worked as an assistant in the General Hospital of Hamburg. In October that year he moved to Idiot’s Hospital of Langenhagen, near Hanover, as a general physician. In 1868, he moved to Neimegk and then to Rakwitz in 1869. As the Franco-Prussian War started in 1870, he enlisted in the German army as a volunteer surgeon in 1871 to support the war effort.[15] He was discharged a year later and was appointed as a district physician (Kreisphysikus) in Wollstein in Prussian Posen (now Wolsztyn, Poland). As his family settled there, his wife gave him a microscope as a birthday gift. With the microscope, he set up a private laboratory and started his career in microbiology.[16][17]

Koch began conducting research on microorganisms in a laboratory connected to his patient examination room.[14] His early research in this laboratory yielded one of his major contributions to the field of microbiology, as he developed the technique of growing bacteria.[18] Furthermore, he managed to isolate and grow selected pathogens in a pure laboratory culture.[18] His discovery of the anthrax bacillus (later named Bacillus anthracis) hugely impressed Ferdinand Julius Cohn, professor at the University of Breslau (now the University of Wrocław), who helped him publish the discovery in 1876.[15] Cohn had established the Institute of Plant Physiology[19] and invited Koch to demonstrate his new bacterium there in 1877.[20] Koch was transferred to Breslau as district physician in 1879. A year after, he left for Berlin when he was appointed a government advisor at the Imperial Health Office, where he worked from 1880 to 1885.[21] Following his discovery of the tuberculosis bacterium, he was promoted to Geheimer Regierungsrat, a senior executive position, in June 1882.[22]

In 1885, Koch received two appointments as an administrator and professor at Berlin University. He became Director of Hygienic Institute and Chair (Professor of hygiene) of the Faculty of Medicine.[15] In 1891, he relinquished his professorship and became a director of the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases (now the Robert Koch Institute) which consisted of a clinical division and beds for the division of clinical research. For this he accepted harsh conditions. The Prussian Ministry of Health insisted after the 1890 scandal with tuberculin, which Koch had discovered and intended as a remedy for tuberculosis, that any of Koch’s inventions would unconditionally belong to the government and he would not be compensated. Koch lost the right to apply for patent protection.[23] In 1906, he moved to East Africa to research a cure for trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). He established the Bugula research camp where up to 1000 people a day were treated with the experimental drug Atoxyl.[24]

Scientific contributions[edit]

Techniques in bacteria study[edit]

Robert Koch made two important developments in microscopy; he was the first to use an oil immersion lens and a condenser that enabled smaller objects to be seen.[11] In addition, he was also the first to effectively use photography (microphotography) for microscopic observation. He introduced the «bedrock methods» of bacterial staining using methylene blue and Bismarck (Vesuvin) brown dye.[7] In an attempt to grow bacteria, Koch began to use solid nutrients such as potato slices.[18] Through these initial experiments, Koch observed individual colonies of identical, pure cells.[18] He found that potato slices were not suitable media for all organisms, and later began to use nutrient solutions with gelatin.[18] However, he soon realized that gelatin, like potato slices, was not the optimal medium for bacterial growth, as it did not remain solid at 37 °C, the ideal temperature for growth of most human pathogens.[18] And also many bacteria can hydrolyze gelatin making it a liquid. As suggested to him by his post-doctoral assistant Walther Hesse, who got the idea from his wife Fanny Hesse, in 1881, Koch started using agar to grow and isolate pure cultures.[25] Agar is a polysaccharide that remains solid at 37 °C, is not degraded by most bacteria, and results in a stable transparent medium.[18][26]

Development of Petri dish[edit]

Koch’s booklet published in 1881 titled «Zur Untersuchung von Pathogenen Organismen» (Methods for the Study of Pathogenic Organisms)[27] has been known as the «Bible of Bacteriology.»[28][29] In it he described a novel method of using glass slide with agar to grow bacteria. The method involved pouring a liquid agar on to the glass slide and then spreading a thin layer of gelatin over. The gelatin made the culture medium solidify, in which bacterial samples could be spread uniformly. The whole bacterial culture was then put in a glass plate together with a small wet paper. Koch named this container as feuchte Kammer (moist chamber). The typical chamber was a circular glass dish 20 cm in diameter and 5 cm in height and had a lid to prevent contamination. The glass plate and the transparent culture media made observation of the bacterial growth easy.[30]

Koch publicly demonstrated his plating method at the Seventh International Medical Congress in London in August 1881. There, Louis Pasteur exclaimed, «C’est un grand progrès, Monsieur!» («What a great progress, Sir!»)[16] It was using Koch’s microscopy and agar-plate culture method that his students discovered new bacteria. Friedrich Loeffler discovered the bacteria of glanders (Burkholderia mallei) in 1882 and diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae) in 1884; and Georg Theodor August Gaffky, the bacterium of typhoid (Salmonella enterica) in 1884.[31] Koch’s assistant Julius Richard Petri developed an improved method and published it in 1887 as «Eine kleine Modification des Koch’schen Plattenverfahrens» (A minor modification of the plating technique of Koch).[32] The culture plate was given an eponymous name Petri dish.[33] It is often asserted that Petri developed a new culture plate,[11][34][35] but this was not so. He simply discarded the use of glass plate and instead used the circular glass dish directly, not just as moist chamber, but as the main culture container. This further reduced chances of contaminations.[25] It would also have been appropriate if the name «Koch dish» had been given.[30]

Anthrax[edit]

Robert Koch is widely known for his work with anthrax, discovering the causative agent of the fatal disease to be Bacillus anthracis.[36] He published the discovery in a booklet as «Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, Begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis» (The Etiology of Anthrax Disease, Based on the Developmental History of Bacillus Anthracis) in 1876 while working at in Wöllstein.[37] His publication in 1877 on the structure of anthrax bacterium[38] marked the first photography of a bacterium.[11] He discovered the formation of spores in anthrax bacteria, which could remain dormant under specific conditions.[14] However, under optimal conditions, the spores were activated and caused disease.[14] To determine this causative agent, he dry-fixed bacterial cultures onto glass slides, used dyes to stain the cultures, and observed them through a microscope.[39] His work with anthrax is notable in that he was the first to link a specific microorganism with a specific disease, rejecting the idea of spontaneous generation and supporting the germ theory of disease.[36]

Tuberculosis[edit]

Koch’s drawing of tuberculosis bacilli in 1882 (from Die Ätiologie der Tuberkulose)

During his time as the government advisor with the Imperial Health Agency in Berlin in the 1880s, Koch became interested in tuberculosis research. At the time, it was widely believed that tuberculosis was an inherited disease. However Koch was convinced that the disease was caused by a bacterium and was infectious. In 1882, he published his findings on tuberculosis, in which he reported the causative agent of the disease to be the slow-growing Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[18] He published the discovery as «Die Ätiologie der Tuberkulose» (The Etiology of Tuberculosis),[26] and presented before the German Physiological Society at Berlin on 24 March 1882. Koch said,

When the cover-glasses were exposed to this staining fluid [methylene blue mixed with potassium hydroxide] for 24 hours, very fine rod-like forms became apparent in the tubercular mass for the first time, having, as further observations showed, the power of multiplication and of spore formation and hence belonging to the same group of organisms as the anthrax bacillus… Microscopic examination then showed that only the previously blue-stained cell nuclei and detritus became brown, while the tubercle bacilli remained a beautiful blue.[16][17]

There was no particular reaction to this announcement. Eminent scientists such as Rudolf Virchow remained skeptical. Virchow clung to his theory that all diseases are due to faulty cellular activities.[40] On the other hand, Paul Ehrlich later recollected that this moment was his «single greatest scientific experience.»[5] Koch expanded the report and published under the same title as a booklet in 1884, in which he concluded that the discovery of tuberculosis bacterium fulfilled the three principles, eventually known as Koch’s postulates, which were formulated by his assistant Friedrich Loeffler in 1883, saying:

All these factors together allow me to conclude that the bacilli present in the tuberculous lesions do not only accompany tuberculosis, but rather cause it. These bacilli are the true agents of tuberculosis.[40]

Cholera[edit]

In August 1883, the German government sent a medical team led by Koch to Alexandria, Egypt, to investigate a cholera epidemic there.[41] Koch soon found that the intestinal mucosa of people who died of cholera always had bacterial infection, yet could not confirm whether the bacteria were the causative pathogens. As the outbreak in Egypt declined, he was transferred to Calcutta (now Kolkata) India, where there was a more severe outbreak. He soon found that the river Ganges was the source of cholera. He performed autopsies of almost 100 bodies, and found in each bacterial infection. He identified the same bacteria from water tanks, linking the source of the infection.[11] He isolated the bacterium in pure culture on 7 January 1884. He subsequently confirmed that the bacterium was a new species, and described as «a little bent, like a comma.»[42] His experiment using fresh blood samples indicated that the bacterium could kill red blood cells, and he hypothesized that some sort of poison was used by the bacterium to cause the disease.[11] In 1959, Indian scientist Sambhu Nath De discovered this poison, the cholera toxin.[43] Koch reported his discovery to the German Secretary of State for the Interior on 2 February, and published it in the Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (German Medical Weekly) the following month.[44]

Although Koch was convinced that the bacterium was the cholera pathogen, he could not entirely establish a critical evidence the bacterium produced the symptoms in healthy subjects (following Koch’s postulates). His experiment on animals using his pure bacteria culture did not cause the disease, and correctly explained that animals are immune to human pathogen. The bacterium was then known as «the comma bacillus», and scientifically as Bacillus comma.[45] It was later realised that the bacterium was already described by an Italian physician Filippo Pacini in 1854,[46] and was also observed by the Catalan physician Joaquim Balcells i Pascual around the same time.[47][48] But they failed to identify the bacterium as the causative agent of cholera. Koch’s colleague Richard Friedrich Johannes Pfeiffer correctly identified the comma bacillus as Pacini’s vibrioni and renamed it as Vibrio cholera in 1896.[49]

Tuberculosis treatment and tuberculin[edit]

Koch gave much of his research attention on tuberculosis throughout his career. After medical expeditions to various parts of the world, he again focussed on tuberculosis from the mid-1880s. By that time the Imperial Health Office was carrying out a project for disinfection of sputum of tuberculosis patients. Koch experimented with arsenic and creosote as possible disinfectants. These chemicals and other available drugs did not work.[11] His report in 1883 also mentioned a failed experiment on an attempt to make tuberculosis vaccine.[22] By 1888, Koch turned his attention to synthetic dyes as antibacterial chemicals. He developed a method for examining antibacterial activity by mixing the gelatin-based culture media with a yellow dye, auramin. His notebook indicates that by February 1890, he tested hundreds of compounds.[5] In one of such tests, he found that an extract from the tuberculosis bacterium culture dissolved in glycerine could cure tuberculosis in guinea pigs. Based on a series of experiments from April to July 1891, he could conclude that the extract did not kill the tuberculosis bacterium, but destroyed (by necrosis) the infected tissues, thereby depriving bacterial growth. He made a vague announcement in August 1890 at the Tenth International Medical Congress in Berlin,[40] saying,

In a communication which I made a few months ago to the International Medical Congress [in London in 1881], I described a substance of which the result is to make laboratory animals insensitive to inoculation of tubercle bacilli, and in the case of already infected animals, to bring the tuberculous process to a halt.[16][17]

I can tell […] that much, that guinea pigs, which are highly susceptible to the disease [tuberculosis], no longer react upon inoculation with tubercle virus [bacterium] when treated with that substance and that in guinea pigs, which are sick (with tuberculosis), the pathological process can be brought to a complete standstill.[5]

By November 1890, Koch was able to show that the extract was effective in humans as well.[50] Many patients and doctors went to Berlin to get Koch’s remedy.[11] But his experiments showed that tuberculosis infected guinea pigs developed severe symptoms when the substance was inoculated. The severity was more so in humans.[40] This development of severe immune response, which is now known to be due to hypersensitivity, is known as the «Koch phenomenon.»[51] The chemical nature was not known, and among several independent experiments done by the next year, only his son-in-law, Eduard Pfuhl, was able to reproduce similar results.[5] It nevertheless became a medical sensation, and the unknown substance was referred to as «Koch’s Lymph.» Koch published his experiments in the 15 January 1891 issue of Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift,[52][53] and The British Medical Journal immediately published the English version simultaneously.[54] The English version was also reproduced in Nature,[55] and The Lancet in the same month.[56] The Lancet presented it as «glad tidings of great joy.»[50] Koch simply referred to the medication as «brownish, transparent fluid.»[12] Josephs Pohl-Pincus had used the name tuberculin in 1844 for tuberculosis culture media,[57] and Koch subsequently adopted as «tuberkulin.»[58]

The first report on the clinical trial in 1891 was disappointing. By then 1061 patients with tuberculosis of internal organs and of 708 patients with tuberculosis of external tissues were given the treatment. An attempt to use tuberculin as a therapeutic drug is regarded as Koch’s «greatest failure.»[40] With it his reputation greatly waned. But he devoted the rest of his life trying to make tuberculin as a usable medication.[50] His discovery was not a total failure, the substance is today used for hypersensitivity test for tuberculosis patients.[11]

Acquired immunity[edit]

Koch observed the phenomenon of acquired immunity. On 26 December 1900, he arrived as part of an expedition to German New Guinea, which was then a protectorate of the German Reich. Koch serially examined the Papuan people, the indigenous inhabitants, and their blood samples and noticed they contained Plasmodium parasites, the cause of malaria, but their bouts of malaria were mild or could not even be noticed, i.e. were subclinical. On the contrary, German settlers and Chinese workers, who had been brought to New Guinea, fell sick immediately. The longer they had stayed in the country, however, the more they too seemed to develop a resistance against it.[59]

Koch’s postulates[edit]

During his time as government advisor, Koch published a report on how he discovered and experimentally showed tuberculosis bacterium as the pathogen of tuberculosis. He described the importance of pure cultures in isolating disease-causing organisms and explained the necessary steps to obtain these cultures, methods which are summarized in Koch’s four postulates.[60] Koch’s discovery of the causative agent of anthrax led to the formation of a generic set of postulates which can be used in the determination of the cause of most infectious diseases.[36] These postulates, which not only outlined a method for linking cause and effect of an infectious disease but also established the significance of laboratory culture of infectious agents, became the «gold standard» in infectious diseases.[61]

Although Koch worked out the principles, he did not formulate the postulates, which were introduced by his assistant Friedrich Loeffler. Loeffler, reporting his discovery of diphtheria bacillus in 1883, stated three postulates as follows:[62]

- 1. The organism must always be present in every case of the disease, but not in healthy individuals.

- 2. The organism must be isolated from a diseased individual and grown in pure culture.

- 3. The pure culture must cause the same disease when inoculated into a healthy, susceptible individuals.[31][63]

The fourth postulate was added by an American plant pathologist Erwin Frink Smith in 1905, and is stated as:[64]

- 4. The same pathogen must be isolated from the experimentally infected individuals.[65]

Personal life[edit]

In July 1867, Koch married Emma (Emmy) Adolfine Josephine Fraatz, and the two had a daughter, Gertrude, in 1868.[9] Their marriage ended after 26 years in 1893, and later that same year, he married actress Hedwig Freiberg (1872–1945).[9]

On 9 April 1910, Koch suffered a heart attack and never made a complete recovery.[39] On 27 May, three days after giving a lecture on his tuberculosis research at the Prussian Academy of Sciences, Koch died in Baden-Baden at the age of 66.[14] Following his death, the Institute named its establishment after him in his honour. He was irreligious.[66]

Awards and honors[edit]

Koch’s name as it appears on the LSHTM frieze in Keppel Street, Bloomsbury, London

Statue of Koch at Robert-Koch-Platz (Robert Koch square) in Berlin

Koch was made a Knight Grand Cross in the Prussian Order of the Red Eagle on 19 November 1890,[67] and was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1897.[68] In 1905, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine «for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis.»[69] In 1906, research on tuberculosis and tropical diseases won him the Order Pour le Merite and in 1908, the Robert Koch Medal, established to honour the greatest living physicians.[39] Emperor Wilhelm I awarded him the Order of the Crown, 100,000 marks and appointment as Privy Imperial Councillor,[7][12] Surgeon-General of Health Service, and Fellow of the Science Senate of Kaiser Wilhelm Society.[15]

Koch established the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases in Berlin 1891. After his death it was renamed Robert Koch Institute in his honour.[7]

The World Health Organization observes «World Tuberculosis Day» every 24 March since 1982 to commemorate the day Koch discovered tuberculosis bacterium.[12]

Koch’s name is one of 23 from the fields of hygiene and tropical medicine featured on the frieze of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine building in Keppel Street, Bloomsbury.[70]

A large marble statue of Koch stands in a small park known as Robert Koch Platz, just north of the Charity Hospital, in the Mitte section of Berlin. His life was the subject of a 1939 German produced motion picture that featured Oscar winning actor Emil Jannings in the title role. On 10 December 2017, Google showed a Doodle in celebration of Koch’s birthday.[71][72]

Koch and his relationship to Paul Ehrlich, who developed a mechanism to diagnose TB, were portrayed in the 1940 movie Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet.

Controversies[edit]

Louis Pasteur[edit]

At their first meeting at the Seventh International Medical Congress in London in August 1881, Koch and Pasteur were friendly towards each other. But the rest of their careers followed with scientific disputes. The conflict started when Koch interpreted his discovery of anthrax bacillus in 1876 as causality, that is, the germ caused the anthrax infections. Although his postulates were not yet formulated, he did not establish the bacterium as the cause of the disease: it was an inference. Pasteur therefore argued that Koch’s discovery was not the full proof of causality, but Pasteur’s anthrax vaccine developed in 1881 was.[73] Koch published his conclusion in 1881 with a statement: «anthrax never occurs without viable anthrax bacilli or spores. In my opinion no more conclusive proof can be given that anthrax bacilli are the true and only cause of anthrax,» and that vaccination such as claimed by Pasteur would be impossible.[74] To prove his vaccine, Pasteur sent his assistant Louis Thuillier to Germany for demonstration and disproved Koch’s idea.[75] They had a heated public debate at the International Congress for Hygiene in Geneva in 1882, where Koch criticised Pasteur’s methods as «unreliable,» and claimed they «are false and [as such ] they inevitably lead to false conclusions.»[12] Koch later continued to attack Pasteur, saying, «Pasteur is not a physician, and one cannot expect him to make sound judgments about pathological processes and the symptoms of disease.»[11]

Tuberculin[edit]

When Koch discovered tuberculin in 1890 as a medication for tuberculosis, he kept the experiment secret and avoided disclosing the source. It was only after a year under public pressure that he publicly announced the experiment and the source.[5] Clinical trials with tuberculin were disastrous and complete failures. Rudolf Virchow’s autopsy report of 21 subjects treated with tuberculin to the Berlin Medical Society on 7 January 1891 revealed that instead of healing tuberculosis, the subjects died because of the treatment.[76] One week later, Koch publicised that the drug was a glycerine extract of a pure cultivation of the tuberculosis bacilli.[5] The German official report in late 1891 declared that tuberculosis was not cured with tuberculin.[40] From this moment onwards, Koch’s prestige fell apart. The reason for his initial secrecy was due to an ambition for monetary benefits for the new drug, and with that establishment of his own research institute.[13] Since 1885, he had tried to leave government service and create an independent state-run institute of his own.[12] Following the disappointment, he was released from the University of Berlin and forced to work as Director of the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases, a newly established institute, in 1891. He was prohibited from working on tuberculin and from claim for patent rights in any of his subsequent works.[23]

Human and cattle tuberculosis[edit]

Koch initially believed that human (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and cattle tuberculosis bacilli (now called Mycobacterium bovis) were different pathogens when he made the discovery in 1882. Two years later, he revoked that position and asserted that the two bacilli were the same type.[77] This later assumption was taken as a fact in veterinary practice. Based on it, legislations were made in US for inspection of meat and milk.[78] In 1898, an American veterinarian Theobald Smith published a detailed comparative study and found that the tuberculosis bacteria are different based on their structure, growth patterns, and pathogenicity. In addition he also discovered that there were variations in each type. In his conclusion, he made two important points:

- Human tuberculosis bacillus cannot infect cattle.

- But cattle bacillus may infect humans since it is very pathogenic.[79]

By that time, there was evidence that cattle tuberculosis was transmitted to humans through meat and milk.[80][81] Upon these reports, Koch conceded that the two bacilli were different but still advocated that cattle tuberculosis was of no health concern. Speaking at the Third International Congress on Tuberculosis, held in London in July 1901, he said that cattle tuberculosis is not dangerous to humans and there is no need for medical attention.[12] He said, «I therefore consider it unnecessary to take any measures against this form of TB. The fight against TB clearly has to concentrate on the human bacillus.«[82] Chair of the congress, Joseph Lister reprimanded Koch and explained the medical evidences of cattle tuberculosis in humans.[83]

The 1902 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine[edit]

The Nobel Committee selected the 1902 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to be awarded for the discovery of the transmission of malaria. But it could not make the final decision on whom to give it to — the British surgeon Ronald Ross or the Italian biologist Giovanni Battista Grassi. Ross had discovered that the human malarial parasite was carried by certain mosquitoes in 1897, and the next year that bird malaria could be transmitted from infected to healthy birds by the bite of a mosquito.[84] Grassi had discovered Plasmodium vivax and the bird malaria parasite, and towards the end of 1898 the transmission of Plasmodium falciparum between humans through mosquitoes Anopheles claviger.[85] To the surprise of the Nobel Committee, the two nominees exchanged polemic arguments against each other publicly justifying the importance of their own works. Robert Koch was then appointed as a «neutral arbitrator» to make the final decision.[86] To his disadvantage, Grassi had criticised Koch on his malaria research in 1898 during an investigation of the epidemic,[85] while Ross had established a cordial relationship with Koch.[87] Ross was selected for the award, as Koch «threw the full weight of his considerable authority in insisting that Grassi did not deserve the honor.»[88]

References[edit]

- ^ «Koch». Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ «Koch». The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- ^ Fleming, Alexander (1952). «Freelance of Science». British Medical Journal. 2 (4778): 269. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4778.269. PMC 2020971.

- ^ Tan, S. Y.; Berman, E. (2008). «Robert Koch (1843-1910): father of microbiology and Nobel laureate». Singapore Medical Journal. 49 (11): 854–855. PMID 19037548.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gradmann, Christoph (2006). «Robert Koch and the white death: from tuberculosis to tuberculin». Microbes and Infection. 8 (1): 294–301. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.004. PMID 16126424.

- ^ Lakhani, S. R. (1993). «Early clinical pathologists: Robert Koch (1843-1910)». Journal of Clinical Pathology. 46 (7): 596–598. doi:10.1136/jcp.46.7.596. PMC 501383. PMID 8157741.

- ^ a b c d Lakhtakia, Ritu (2014). «The Legacy of Robert Koch: Surmise, search, substantiate». Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 14 (1): e37–41. doi:10.12816/0003334. PMC 3916274. PMID 24516751.

- ^ Margo, Curtis E. (2011-04-11). «From Robert Koch to Bradford Hill: Chronic Infection and the Origins of Ocular Adnexal Cancers». Archives of Ophthalmology. 129 (4): 498–500. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.53. ISSN 0003-9950. PMID 21482875.

- ^ a b c d Brock, Thomas. Robert Koch: A life in medicine and bacteriology. ASM Press: Washington DC, 1999. Print.

- ^ Metchnikoff, Elie. The Founders of Modern Medicine: Pasteur, Koch, Lister. Classics of Medicine Library: Delanco, 2006. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Blevins, Steve M.; Bronze, Michael S. (2010). «Robert Koch and the ‘golden age’ of bacteriology». International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 14 (9): e744–751. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.12.003. PMID 20413340.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ligon, B. Lee (2002). «Robert Koch: Nobel laureate and controversial figure in tuberculin research». Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 13 (4): 289–299. doi:10.1053/spid.2002.127205. PMID 12491235.

- ^ a b Akkermans, Rebecca (2014). «Robert Heinrich Herman Koch». The Lancet. 2 (4): 264–265. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70018-9. PMID 24717622.

- ^ a b c d e «Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch.» World of Scientific Discovery. Gale, 2006. Biography in Context. Web. 14 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Ernst, H. C. (1918). «Robert Koch (1843-1910)». Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 53 (10): 825–827. JSTOR 25130022.

- ^ a b c d e Sakula, A. (1982). «Robert Koch: centenary of the discovery of the tubercle bacillus, 1882». Thorax. 37 (4): 246–251. doi:10.1136/thx.37.4.246. PMC 459292. PMID 6180494.

- ^ a b c d Sakula, A. (1983). «Robert koch: centenary of the discovery of the tubercle bacillus, 1882». The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 24 (4): 127–131. PMC 1790283. PMID 17422248.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Madigan, Michael T., et al. Brock Biology of Microorganisms: Thirteenth edition. Benjamin Cummings: Boston, 2012. Print.

- ^ Pick, E. (2001). «Medical luminaries». Nature. 411 (6840): 885. Bibcode:2001Natur.411..885P. doi:10.1038/35082239. PMID 11418826. S2CID 30630349.

- ^ Salomonsen, C. J. (1950). «Reminiscences of the summer semester, 1877, at Breslau». Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 24 (4): 333–351. JSTOR 44443542. PMID 15434544.

- ^ O’Connor, T.M. «Tuberculosis, Overview.» International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008. Web.

- ^ a b Gradmann, C. (2001). «Robert Koch and the pressures of scientific research: tuberculosis and tuberculin». Medical History. 45 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1017/s0025727300000028. PMC 1044696. PMID 11235050.

- ^ a b Christoph Gradmann: Laboratory Disease, Robert Koch’s Medical Bacteriology. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2009, ISBN 978-0-8018-9313-1, p. 111 ff.

- ^ Bonhomme, Edna. «When Africa was a German laboratory». www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2020-10-07.

- ^ a b Hufford, David C. (1988-03-01). «A Minor Modification by R. J. Petri». Laboratory Medicine. 19 (3): 169–170. doi:10.1093/labmed/19.3.169. ISSN 0007-5027.

- ^ a b Koch, Robert (1882-03-24). «Die Ätiologie der Tuberkulose» [The Etiology of Tuberculosis]. Physiologische Gesellschaft zu Berlin/Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift. 19: 221–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-56454-7_4. ISBN 978-3-662-56454-7.

From page 225: «Die Tuberkelbacillen lassen sich auch noch auf anderen Nährsubstraten kultivieren, wenn letztere ähnliche Eigenschaften wie das erstarrte Blutserum besitzen. So wachsen sie beispielsweise auf einer mit Agar-Agar bereiteten, bei Blutwärme hart bleibenden Gallerte, welche einen Zusatz von Fleischinfus und Pepton erhalten hat.« (The tubercule bacilli can also be cultivated on other media, if the latter have properties similar to those of congealed blood serum. Thus they grow, for example, on a gelatinous mass prepared with agar-agar, which remains solid at blood temperature, and which has received a supplement of meat broth and peptone.)

- ^ Koch, Robert (2010) [1881]. Zur Untersuchung von Pathogenen Organismen. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut. doi:10.25646/5071.

- ^ Booss, John; Tselis, Alex C. (2014), «A history of viral infections of the central nervous system», Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Elsevier, 123: 3–44, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53488-0.00001-8, ISBN 978-0-444-53488-0, PMID 25015479, retrieved 2021-04-15

- ^ Hurt, Leslie (2003). «Dr. Robert Koch:: a founding father of biology». Primary Care Update for OB/GYNS. 10 (2): 73–74. doi:10.1016/S1068-607X(02)00167-1.

- ^ a b Shama, Gilbert (2019). «The «Petri» Dish: A Case of Simultaneous Invention in Bacteriology». Endeavour. 43 (1–2): 11–16. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2019.04.001. PMID 31030894. S2CID 139105012.

- ^ a b Weiss, Robin A. (2005). «Robert Koch: the grandfather of cloning?». Cell. 123 (4): 539–542. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.001. PMID 16286000.

- ^ Petri, Julius Richard (1887). «Eine kleine Modification des Koch’schen Plattenverfahrens». Centralblatt für Bacteriologie und Parasitenkunde. 1: 279–280.

- ^ Mahajan, Monika (2021). «Etymologia: Petri Dish». Emerging Infectious Diseases. 27 (1): 261. doi:10.3201/eid2701.ET2701. PMC 7774570.

- ^ Zhang, Shuguang (2004). «Beyond the Petri dish». Nature Biotechnology. 22 (2): 151–152. doi:10.1038/nbt0204-151. PMID 14755282. S2CID 36391864.

- ^ Grzybowski, Andrzej; Pietrzak, Krzysztof (2014). «Robert Koch (1843-1910) and dermatology on his 171st birthday». Clinics in Dermatology. 32 (3): 448–450. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.10.005. PMID 24887990.

- ^ a b c «Germ theory of disease.» World of Microbiology and Immunology. Ed. Brenda Wilmoth Lerner and K. Lee Lerner. Detroit: Gale, 2007. Biography in Context. Web. 14 April 2013.

- ^ Koch, Robert (2010) [1876]. Robert Koch-Institut. «Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis». Cohns Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen (in German). 2 (2): 277 (1–22). doi:10.25646/5064.

- ^ Koch, Robert (2010) [1877]. «Verfahren zur Untersuchung, zum Konservieren und Photographieren der Bakterien». Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen (in German). 2: 399–434. doi:10.25646/5065 – via Robert Koch-Institut.

- ^ a b c «Robert Koch.» World of Microbiology and Immunology. Ed. Brenda Wilmoth Lerner and K. Lee Lerner. Detroit: Gale, 2006. Biography in Context. Web. 14 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaufmann, Stefan H. E.; Schaible, Ulrich E. (2005). «100th anniversary of Robert Koch’s Nobel Prize for the discovery of the tubercle bacillus». Trends in Microbiology. 13 (10): 469–475. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.08.003. PMID 16112578.

- ^ Howard-Jones, N. (1984). «Robert Koch and the cholera vibrio: a centenary». British Medical Journal. 288 (6414): 379–381. doi:10.1136/bmj.288.6414.379. PMC 1444283. PMID 6419937.

- ^ Lippi, D.; Gotuzzo, E. (2014). «The greatest steps towards the discovery of Vibrio cholerae». Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (3): 191–195. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12390. PMID 24191858.

- ^ Nair, G. Balakrish; Takeda, Yoshifumi (2011). «Dr Sambhu Nath De: unsung hero». The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 133 (2): 127. PMC 3089041. PMID 21415484.

- ^ Koch, R. (20 March 1884) «Sechster Bericht der deutschen wissenschaftlichen Commission zur Erforschung der Cholera» (Sixth report of the German scientific commission for research on cholera), Deutsche medizinische Wochenscrift (German Medical Weekly), 10 (12): 191–192. On page 191, he mentions the characteristic comma shape of Vibrio cholerae: «Im letzten Berichte konnte ich bereits gehorsamst mittheilen, dass an den Bacillen des Choleradarms besondere Eigenschaften aufgefunden wurden, durch welche sie mit aller Sicherheit von anderen Bakterien zu unterscheiden sind. Von diesen Merkmalen sind folgende die am meisten charakteristischen: Die Bacillen sind nicht ganz geradlinig, wie die übrigen Bacillen, sondern ein wenig gekrümmt, einem Komma ähnlich.« (In the last report, I could already respectfully report that unusual characteristics were discovered in the bacteria of enteric cholera, by which they are to be distinguished with complete certainty from other bacteria. Of these features, the following are the most characteristic: the bacteria are not quite straight, like the rest of the bacilli, but a little bent, similar to a comma.)

- ^ Winslow, C. E.; Broadhurst, J.; Buchanan, R. E.; Krumwiede, C.; Rogers, L. A.; Smith, G. H. (1920). «The Families and Genera of the Bacteria: Final Report of the Committee of the Society of American Bacteriologists on Characterization and Classification of Bacterial Types». Journal of Bacteriology. 5 (3): 191–229. doi:10.1128/JB.5.3.191-229.1920. PMC 378870. PMID 16558872.

- ^ See:

- Fillipo Pacini (1854) «Osservazioni microscopiche e deduzioni patologiche sul cholera asiatico» (Microscopic observations and pathological deductions on Asiatic cholera), Gazzetta Medica Italiana: Toscana, 2nd series, 4(50):397–401; 4(51):405–12.

- Reprinted (more legibly) as a pamphlet.

- ^ Real Academia de la Historia, ed. (2018). «Joaquín Balcells y Pasqual» (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ Col·legi Oficial de Metges de Barcelona, ed. (2015). «Joaquim Balcells i Pascual» (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ Hugh, Rudolph (1965). «Nomenclature and taxonomy of Vibrio cholerae Pacini 1854 and Vibrio eltor Pribam 1933». Public Health Service Publication. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Environmental Health Service, National Air Pollution Control Administration. pp. 1–4.

- ^ a b c Sakula, Alex (1985). «Robert Koch: The story of his discoveries in tuberculosis». Irish Journal of Medical Science. 154 (S1): 3–9. doi:10.1007/BF02938285. PMID 3897123. S2CID 38056335.

- ^ Hunter, Robert L. (2020). «The Pathogenesis of Tuberculosis-The Koch Phenomenon Reinstated». Pathogens. 9 (10): e813. doi:10.3390/pathogens9100813. PMC 7601602. PMID 33020397.

- ^ Koch, Robert (2010) [1891]. «Fortsetzung der Mitteilungen über ein Heilmittel gegen Tuberkulose». Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 17: 101–102. doi:10.25646/5100 – via Robert Koch-Institut.

- ^ Koch, Robert (1891). «A Further Communication on a Remedy for Tuberculosis». The Indian Medical Gazette. 26 (3): 85–87. PMC 5150357. PMID 29000631.

- ^ Koch, R. (1891). «A Further Communication on a Remedy for Tuberculosis». British Medical Journal. 1 (1568): 125–127. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1568.125. PMC 2196966. PMID 20753227.

- ^ «Dr. Koch’s Remedy for Tuberculosis». Nature. 43 (1108): 281–282. 1891. Bibcode:1891Natur..43..281.. doi:10.1038/043281a0. S2CID 4050612.

- ^ Richmond, W.S. (1891). «Professor Koch’s Remedy for Tuberculosis». The Lancet. 137 (3514): 56–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)15705-9.

- ^ Caspary (1884). «Angioneurotische Dermatosen». Vierteljahresschrift für Dermatologie und Syphilis (in German). 16 (1): 141–155. doi:10.1007/BF02097828. S2CID 33099318.

Pohl-Pincus wrote: Wir werden deshalb alas Tuberculin darzustellen suchen [We shall therefore endeavor to describe it as tuberculin]

- ^ Koch, R. (1891). «Weitere Mittheilung über das Tuberkulin». Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 17 (43): 1189–1192. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1206810.

- ^ Hugo Kronecker: Hygienische Topographie In: A. Pfeiffer (Editor): 21. Jahresbericht über die Fortschritte und Leistungen auf dem Gebiete der Hygiene. 1903. Publisher: Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn, Braunschweig, 1905. p. 68

- ^ Amsterdamska, Olga. «Bacteriology, Historical.» International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008. Web.

- ^ Tabrah, Frank L. (2011). «Koch’s postulates, carnivorous cows, and tuberculosis today». Hawaii Medical Journal. 70 (7): 144–148. PMC 3158372. PMID 21886302.

- ^ Loeffler, Friedrich (1884). «Untersuchungen über die Bedeutung der Mikroorganismen für die Entstehung der Diphtherie beim Menschen, bei der Taube und beim Kalbe» [Investigations of the relevance of microorganisms to the development of diphtheria among humans, among doves, and among heifers]. Mittheilungen aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte (Reports from the Imperial Office of Public Health) (in German). 2: 421–499. From 424: «Wenn nun die Diphtherie eine durch Mikroorganismen bedingte Krankheit ist, so müssen sich auch bei ihr jene drei Postulate erfüllen lassen, deren Erfüllung für den stricten Beweis der parasitäten Natur einer jeden derartigen Krankheit unumgänglich nothwendig ist:

1) Es müssen constant in den local erkrankten Parteien Organismen in typischer Anordnung nachgewiesen werden.

2) Die Organismen, welchen nach ihrem Verhalten zu den erkrankten Theilen eine Bedeutung für das Zustandekommen dieser Veränderungen beizulegen wäre, müssen isolirt und rein gezüchtet werden.

3) Mit den Reinculturen muss die Krankheit experimentell wieder erzeugt werden können.»

(Now if diphtheria is a disease that’s caused by microorganisms, then it must also be able to fulfill those three postulates whose fulfillment is absolutely necessary for the strict proof of the parasitic nature of any such disease:

1) In the given diseased patients, there must always be shown [to be present] organisms in typical disposition.

2) The organisms to which one would attribute — according to their behavior in the diseased parts — a relevance for the occurrence of these changes, must be isolated and cultured in pure form.

3) The disease must be able to be reproduced experimentally via pure cultures.) - ^ Byrd, Allyson L.; Segre, Julia A. (2016). «Adapting Koch’s postulates». Science. 351 (6270): 224–226. Bibcode:2016Sci…351..224B. doi:10.1126/science.aad6753. PMID 26816362. S2CID 29595548.

- ^ Smith, Erwin F. (1905). Bacteria in Relation to Plant Diseases. Vol. 1. Washington. D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 9.

- ^ Hadley, Caroline (2006). «The infection connection». EMBO Reports. 7 (5): 470–473. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400699. PMC 1479565. PMID 16670677.

- ^ Thomas D. Brock (1988). Robert Koch: A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology. ASM Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-55581-143-3. «He loved seeing new things, but showed no interest in politics. Religion never entered his life.»

- ^ «Rother Adler-orden», Königlich Preussische Ordensliste (supp.) (in German), vol. 1, Berlin, 1886, p. 7 – via hathitrust.org

- ^ «Fellows of the Royal Society». London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 2015-03-16.

- ^ «The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1905». NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

- ^ «London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Behind the Frieze».

- ^ «Celebrating Robert Koch». www.google.com.

- ^ «Robert Koch Google Doodle». Archived from the original on 2021-11-11 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Carter, K. C. (1988). «The Koch-Pasteur dispute on establishing the cause of anthrax». Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 62 (1): 42–57. JSTOR 44449292. PMID 3285924.

- ^ Koch, R. (2010) [1881]. «Zur Ätiologie des Milzbrandes» [On the etiology of anthrax]. Mittheilungen aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte (PDF). Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut. pp. 174–206.

- ^ Rietschel, Ernst Th; Cavaillon, Jean-Marc (2002). «Endotoxin and anti-endotoxin. The contribution of the schools of Koch and Pasteur: life, milestone-experiments and concepts of Richard Pfeiffer (Berlin) and Alexandre Besredka (Paris)». Journal of Endotoxin Research. 8 (2): 71–82. doi:10.1179/096805102125000218. PMID 12028747.

- ^ Leibowitz, D. (1993). «Scientific failure in an age of optimism: public reaction to Robert Koch’s tuberculin cure». New York State Journal of Medicine. 93 (1): 41–48. PMID 8429953.

- ^ Packer, R. A. (1987). «Veterinarians challenge Dr. Robert Koch regarding bovine tuberculosis and public health: a chronology of events». Veterinary Heritage. 10 (2): 7–11. PMID 11621492.

- ^ Packer, R. A. (1990). «Veterinarians challenge Dr. Robert Koch regarding bovine tuberculosis and public health». Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 196 (4): 574–575. PMID 2406233.

- ^ Smith, T. (1898). «A comparative study of bovine tubercle bacilli and of human bacilli from sputum». The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 3 (4–5): 451–511. doi:10.1084/jem.3.4-5.451. PMC 2117982. PMID 19866892.

- ^ Bergey, D. H. (1897). «Bovine Tuberculosis in its Relation to the Public Health». Public Health Papers and Reports. 23: 310–320. PMC 2329987. PMID 19600776.

- ^ «Reviews and Notices». British Medical Journal. 2 (1072): 85–86. 1881. PMC 2263995.

- ^ Kaufmann, Stefan H. E. (2003). «A short history of Robert Koch’s fight against tuberculosis: those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it». Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland). 83 (1–3): 86–90. doi:10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00064-1. PMID 12758195.

- ^ Clark, Paul F. (1920). «Joseph Lister, his Life and Work». The Scientific Monthly. 11 (6): 518–539. Bibcode:1920SciMo..11..518C.

- ^ Cox FEG (2010). «History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors». Parasites & Vectors. 3 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-5. PMC 2825508. PMID 20205846.

- ^ a b Capanna E (2012). «Grassi versus Ross: who solved the riddle of malaria?». International Microbiology. 9 (1): 69–74. PMID 16636993.

- ^ Pai-Dhungat, J. V.; Parikh, Falguni (2015). «Battista Grassi (1854-1925) & Malaria Controversy» (PDF). The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 63 (3): 108. PMID 26543977.

- ^ Ross, R. (1925). «The mosquito-theory of malaria and the late Prof. G. B. Grassi». Science Progress in the Twentieth Century (1919-1933). 20 (78): 311–320. JSTOR 43427633.

- ^ Esch GW (2007). Parasites and Infectious Disease: Discovery by Serendipity and Otherwise. Cambridge University Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 9781139464109.

Further reading[edit]

- Brock, Thomas D. (1999). Robert Koch: A Life in Medicine and Bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press. ISBN 978-1-55581-143-3. OCLC 39951653.

- de Kruif, Paul (1926). «ch. IV Koch: The Death Fighter». Microbe Hunters. Blue Ribbon Books. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company Inc. pp. 105–144. Retrieved 2020-10-14.

- Morris, Robert D (2007). The blue death: disease, disaster and the water we drink. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-073089-5. OCLC 71266565.

- Gradmann, Christoph (2009). Laboratory Disease: Robert Koch’s Medical Bacteriology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9313-1.

- Weindling, Paul. «Scientific elites and laboratory organization in fin de siècle Paris and Berlin: The Pasteur Institute and Robert Koch’s Institute for Infectious Diseases compared,» in Andrew Cunningham and Perry Williams, eds. The Laboratory Revolution in Medicine (Cambridge University Press, 1992) pp: 170–88.

- Christoph, Hans Gerhard: Robert Koch » Trias deutschen Forschergeistes » Naturheilpraxis / Pflaum- Verlag / Munich 70.Jahrgang December 2017 pages 90–93

External links[edit]

Robert Koch was a German physician who is widely credited as one of the founders of bacteriology and microbiology. He investigated the anthrax disease cycle in 1876, and studied the bacteria that causes tuberculosis in 1882, and cholera in 1883. He also formulated Koch’s postulates. Koch won the 1905 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Advertisements

Early Life and Education:

Born on 11 December in 1843 in Glausthal, Germany, Robert Koch was a childhood prodigy. He taught himself to read newspapers when he was only 5. He loved to read classical literature and was a chess expert. He gained an interest in science while in high school, and decided to study biology. Koch acquired his medical degree from the University of Göttingen, Germany in 1866.

Contributions and Achievements:

Koch developed a strong interest in pathology and infectious diseases as a medical student. After working as a physician in many small towns throughout Germany, he volunteered as a military surgeon during the Franco-Prussian war (1870-72). He was appointed a district medical officer for Wollstein after the war.

His main duty as a medical officer was investigating the spread of infectious bacterial diseases. Koch was very much interested in the transmission of anthrax from cattle to humans. Not very happy with the prevailing process of confirming the cause of infectious disease, Koch formulated four criteria in 1890 that must be achieved for establishing a cause of an infectious disease. These rules were termed as “Koch’s postulates” or “Henle-Koch postulates”. German pathologist Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle was a collaborator in Koch’s research.

Later Life and Death:

Robert Koch’s brilliant contributions were acknowledged in 1905, and he won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. The medical applications of biotechnology still heavily depend on the Koch’s principles of affirming the causes of infectious diseases. Koch died on 27 May in 1910 in Black Forest region of Germany. He was 66 years old.

Advertisements

Content

- Biography

- Early years

- Background and work on the bacillus

- Finding the endospores

- Stay in Berlin

- Cholera study

- Teaching experience and travel

- Last years and death

- Koch’s postulates

- First postulate

- Second postulate

- Third postulate

- Fourth postulate

- Contributions and discoveries

- Isolation of bacteria

- Diseases caused by germs

- Achievements and awards

- Current awards honoring Robert Koch

- Published works

- References

Robert Koch(1843-1910) was a German microbiologist and physician acclaimed for having discovered the bacillus that causes tuberculosis in 1882. In addition, Koch also found the bacillus that causes cholera and wrote a series of very important postulates about this bacterium. He is currently considered the father of modern medical microbiology.

After the discovery of the bacillus in cholera in 1883, Koch dedicated himself to writing his postulates; thanks to this he obtained the nickname of «founder of bacteriology». These discoveries and investigations led the doctor to receive the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1905.

In general terms, the technical work of Robert Koch consisted in achieving the isolation of the microorganism that caused the disease to force it to grow in a pure culture. This had the purpose of reproducing the disease in the animals used in the laboratory; Koch decided to use a guinea pig.

After infecting the rodent, Koch again isolated the germ from the infected animals to corroborate its identity by comparing it with the original bacteria, which allowed him to recognize the bacillus.

Koch’s postulates served to establish the conditions under which an organism can be considered as the cause of a disease. To develop this research Koch used the Bacillus anthracis and demonstrated that by injecting a little blood from a sick rodent to a healthy one, the latter will suffer from anthrax (a highly contagious disease).

Robert Koch dedicated his life to studying infectious diseases with the aim of establishing that, although many bacteria are necessary for the proper functioning of the human body, others are harmful and even fatal because they cause many diseases.

The researches of this scientist implied a decisive moment in the history of medicine and bacteriology: during the nineteenth century the life expectancy of humans was reduced and few people reached old age. Robert Koch (along with Louis Pasteur) managed to introduce important advances despite the limited technological resources of the time.

Early years

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch was born on December 11, 1843 in Chausthal, specifically in the Harz Mountains, a place that at that time belonged to the kingdom of Hannover.His father was an important engineer in the mines.

In 1866 the hometown of the scientist became Prussia, as a result of the Austro-Prussian warfare.

Koch studied medicine at the University of Göttingen, which was highly regarded for the quality of its scientific teachings. His tutor was Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle, who was a physician, anatomist and zoologist who was widely acclaimed for having discovered the loop of Henle located in the kidney. Koch earned his college degree in 1866.

Upon graduation, Koch participated in the Franco-Prussian War, which ended in 1871. He later became the official physician for Wollstein, a district located in Polish Prussia.

During this period he dedicated himself to working hard in bacteriology, despite the few technical resources of the time. He became one of the founders of this discipline together with Louis Pasteur.

Background and work on the bacillus

Before Koch was dedicated to studying the bacillus, another scientist named Casimir Davaine had succeeded in showing that the anthrax bacillus — also known as anthrax — was transmitted directly between cattle.

From that moment on, Koch became interested in learning more about how the disease spread.

Finding the endospores

To delve into this area, the German scientist decided to extract the bacillus from some blood samples in order to force it to grow in certain pure cultures.

Thanks to this procedure, Koch realized that the bacillus did not have the capacity to survive for long periods in the external part of the host; however, it could manufacture endospores that did manage to survive.

Likewise, the scientist discovered what was the agent that caused the disease: the endospores found in the soil explained the emergence of spontaneous outbreaks of anthrax.

These discoveries were published in 1876 and earned Koch an award from the Imperial Health Office of the city of Berlin. Koch received the award four years after its discovery.

In this context, in 1881 he decided to promote sterilization -that is, the cleaning of a product in order to eradicate viable microorganisms- of surgical instruments through the application of heat.

Stay in Berlin

During his stay in the city of Berlin, Koch managed to improve the methods that he had been using in Wollstein, so he was able to include certain purification and staining techniques that contributed significantly to his research.

Koch was able to use the agar plates, which consist of a culture medium, to grow small plants or microorganisms.

He also used the Petri dish, made by Julius Richard Petri, who was Koch’s assistant during some of his research. The Petri dish or box consists of a round container that allows you to place the plate on top and close the container, but not hermetically.

Both the agar plate and the Petri dish are devices that are still in use today. With these instruments Koch managed to discover the Mycobacerium tuberculosis in 1882: the announcement of the find was generated on March 24 of that same year.

In the 19th century, tuberculosis was one of the most lethal diseases, since it caused one in every seven deaths.

Cholera study

In 1883 Robert Koch decided to join a French study and research team that had decided to travel to Alexandria with the aim of analyzing the disease of cholera. In addition, he also enrolled to study in India, where he dedicated himself to identifying the bacteria that caused this disease, known as Vibrio.

In 1854 Filippo Pacini had managed to isolate this bacterium; however, this discovery had been ignored due to the popular miasmatic theory of disease, which established that diseases were the product of miasmas (fetid emanations found in impure waters and in soils).

Koch is considered unaware of Pacini’s research, so his discovery came independently. Through his prominence, Robert was able to disseminate the results more successfully, which was of general benefit. However, in 1965 scientists renamed the bacterium as Vibrio cholerae in honor of Pacini.

Teaching experience and travel

In 1885 Koch was selected as a professor of hygiene by the University of Berlin and later became an honorary professor in 1891, specifically in the area of medicine.

He was also rector of the Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases, which was later renamed the Robert Koch Institute as a tribute to his remarkable research.

In 1904 Koch decided to leave his post at the institute in order to undertake trips around the world. This allowed him to analyze different diseases in India, Java and South Africa.

During his journey the scientist visited the Indian Veterinary Research Institute, located in Mukteshwar. This he did at the request of the government of India, as there was a strong plague spread throughout the livestock.

The utensils that Koch used during this research, among which the microscope stands out, are still preserved in the museum of that institute.

Last years and death

Thanks to the methods used by Koch, many of his pupils and apprentices were able to discover the organisms that cause pneumonia, diphtheria, typhus, gonorrhea, leprosy, cerebrospinal meningitis, tetanus, syphilis, and pulmonary plague.

Likewise, this German scientist was not only important for his research on tuberculosis but also for his postulates, which served him to obtain the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1905.

Robert Koch died on May 27, 1910 as a result of a heart attack in the German city Baden-Baden. The scientist was 66 years old.

Koch’s postulates

Koch’s postulates were formulated by the scientist after he carried out his experiments on the Bacillus anthracis.

These precepts were applied to know the etiology of anthrax; however, they can be used to study any infectious disease because these precepts allow identifying the agent that causes the disease.

Taking this into account, the following postulates elaborated by Robert Koch can be established:

First postulate

The pathogen — or harmful agent — must be present only in sick animals, which implies that it is absent in healthy animals.

Second postulate

The pathogen must be grown in a pure axenic culture, which means that it must be grown in a microbial species that comes from a single cell. This must be done on the animal’s body.

Third postulate

The pathogenic agent that was previously isolated in the axenic culture must induce the disease or disease in an animal that is fit when inoculated.

Fourth postulate

Finally, the pathogenic agent has to be isolated again after having produced the lesions in the animals selected for the experiment. Said agent must be the same one that was isolated the first time.

Contributions and discoveries

Isolation of bacteria

In general, the most significant contribution of Robert Koch consisted in isolating the bacteria that cause the emergence of cholera and tuberculosis in order to study them as pathogens.

Thanks to this Koch research, the existence of other diseases later began to be related to the presence of bacteria and microorganisms.

Before Robert Koch’s findings, the progress of research on human diseases during the 19th century was quite slow, as there were many difficulties in obtaining pure cultures containing only one type of microorganism.

In 1880 the scientist managed to simplify these inconveniences by cultivating the bacteria in containers or solid media instead of protecting the bacteria in liquid containers; this prevented the microorganisms from mixing. After this contribution the discoveries began to develop more quickly.

Diseases caused by germs

Before getting the solid cultures, Koch had already managed to show that diseases occur due to the presence of germs and not vice versa.

To test his theory, the German scientist had grown several small rod-shaped or rod-shaped bodies that had been found in the organic tissues of rodents that suffered from the anthrax disease.

If these bacilli were introduced into healthy animals, they caused the disease and ended up dying shortly after.

Achievements and awards

The highest distinction Robert Koch earned for his accomplishments was the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which is awarded to those who have made outstanding contributions or discoveries in the area of life sciences or medicine.

Koch received this distinction as a result of his postulates, since these allowed and facilitated the study of bacteriology.

Current awards honoring Robert Koch

Regarding the prizes awarded in his name, in 1970 the Robert Koch Prize was established in Germany (Robert Koch Preis), which is a prestigious award for scientific innovations made by young Germans.

This award is awarded by the German Ministry of Health every year to those who have excelled in the area of biomedicine. In this way, research related to infectious and carcinogenic diseases is promoted.

Likewise, there is not only the Robert Koch prize but there is also a foundation with his name, which is in charge of granting this recognition along with a sum of 100,000 euros and a gold medal as a distinction for the professional career of scientists .

Published works

Some of Robert Koch’s best known published works include the following:

— Investigations in the etiology of infectious diseases, published in 1880.

– The etiology of tuberculosis, made in 1890.

— Possible remedies for tuberculosis, written in 1890.

– Professor Koch on the Bacteriological Diagnosis of Cholera, Water Leakage and Cholera in Germany during the winter of 1892. (This work was published in 1894 and consists of a compilation of different scientific experiences related to cholera).

References

- Anderson, M. (s.f.) Robert Koch and his discoveries. Retrieved on June 2, 2019 from History and biographies: historiaybiografias.com

- López, A. (2017) Robert Koch, the father of modern medical microbiology. Retrieved on June 2, 2019 from El País: elpais.com

- Pérez, A. (2001) Life and work of Roberto Koch. Retrieved on June 3, 2019 from Imbiomed: imbiomed.com

- S.A. (s.f.) Robert Koch. Retrieved on June 3, 2019 from Wikipedia: es.wikipedia.org

- Vicente, M. (2008) Robert Koch: scientist, traveler and lover. Retrieved on June 3, 2019 from Madrid more: madrimasd.org

- Текст

- Веб-страница

Robert Koch is a prominent German bacteriologist, the founder of modern microbiology. He was born in 1843, died 1910. When Koch became a doctor he carried on many experiments on mice in a small laboratory. In 1882 Koch discovered tuberculosis bacilli. In his report made in the Berlin physiological society Koch described in detail the morphology of tuberculosis bacilli and the ways to reveal them. Due to his discovery Koch became known all over the world. In 1884 Koch published his book on cholera. This book included the inverstigations of his research work carried out during the cholera epidemic in Egypt and India. From the intestines of the men with cholera Koch isolated a small comma-shaped bacterium. He determined that these bacteria spread through drinking water. In 1905 Koch got the Nobel prize for his important scientific discoveries.

0/5000

Результаты (русский) 1: [копия]

Скопировано!

Роберт Кох — выдающийся немецкий бактериолог, основатель современной микробиологии. Он родился в 1843 году, умер в 1910. Когда Кох стал доктором он нес на многие эксперименты на мышах в небольшой лаборатории. В 1882 году Кох открыл микобактерий туберкулеза. В своем докладе в Берлине физиологического общества Кох подробно морфология микобактерий туберкулеза и способы их раскрывать. Из-за его открытие Кох стал известен всему миру. В 1884 году Кох опубликовал свою книгу на холеру. Эта книга включает inverstigations его исследовательской работы, проведенной во время эпидемии холеры в Египте и Индии. Из кишечника мужчин с холерой Кох изолированные небольшие запятая образный бактерии. Он определил, что эти бактерии распространяются через питьевую воду. В 1905 году Кох получил Нобелевскую премию для его важных научных открытий.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 2:[копия]

Скопировано!

Роберт Кох является известный немецкий бактериолог, основоположник современной микробиологии. Он родился в 1843 году, умер 1910. Когда Кох стал доктором он нес на многих экспериментах на мышах в маленькой лаборатории. В 1882 Кох обнаружил туберкулеза микобактерии. В своем докладе, достигнутом в физиологическом обществе Берлин Кох подробно описал морфологию туберкулеза бацилл и способы их выявление. Благодаря его открытию Кох стал известен во всем мире. В 1884 Кох опубликовал свою книгу о холере. Эта книга включала inverstigations его исследовательской работы, проведенной во время эпидемии холеры в Египте и Индии. Из кишечника мужчин с холерой Кох изолировал маленькую форме запятой бактерии. Он определил, что эти бактерии распространяются через питьевую воду. В 1905 Кох получил Нобелевскую премию за его важных научных открытий.

переводится, пожалуйста, подождите..

Результаты (русский) 3:[копия]

Скопировано!