В жанрах церковной музыки Моцарт ориентировался свободно: по долгу службы или на заказ он написал множество месс, мотетов, гимнов, антифонов и т.д. Большинство из них создано в зальцбургский период. К венскому десятилетию относятся только 2 больших сочинения, причем оба не закончены. Это Месса c-moll и Реквием, хотя была и масонская музыка (тоже религиозная по смыслу).

История создания

Реквием завершает творческий путь Моцарта, будучи последним произведением композитора. Одно это заставляет воспринимать его музыку совершенно по-особому, как эпилог всей жизни, художественное завещание. Моцарт писал его на заказ, который получил в июле 1791 года, однако он не сразу смог взяться за работу – ее пришлось отложить ради «Милосердия Тита» и «Волшебной флейты». Только после премьеры своей последней оперы композитор целиком сосредоточился на Реквиеме.

Для тяжело больного Моцарта работа над траурной мессой была не просто сочинением. Он сам умирал и знал, что дни его сочтены. Он работал с быстротой, невиданной даже для него, и всё же гениальное создание осталось незавершенным: из 12 задуманных номеров было закончено неполных 9. При этом многое было выписано с сокращениями или осталось в черновых набросках. Завершил Реквием ученик Моцарта Ф.Кс. Зюсмайр, который был в курсе моцартовского замысла. Он проделал кропотливую работу, по крупицам собрав всё, что относилось к Реквиему.

Реквием породил многочисленные легенды и дискуссии. Один из главных вопросов – что написано самим Моцартом, а что привнесено Зюсмайром? Авторитетные музыковеды склоняются к мнению, что подлинный моцартовский текст идет с самого начала до первых 8 тактов «Lacrimosа». Далее за дело взялся Зюсмайр, опираясь на черновые наброски, предварительные эскизы, отдельные устные указания Моцарта.

Характеристика жанра

Реквием – это траурная, заупокойная месса. От обычной мессы реквием отличается отсутствием таких частей, как«Gloria» и «Credo», вместо которых включались особые, связанные с погребальным обрядом. Текст реквиема был каноническим. После вступительной молитвы «Даруй им вечный покой» (Requiem aeternam dona eis») шла обычная часть мессы «Kyrie», а затем средневековая секвенция «Dies irae» (День гнева). Следующие молитвы – «Domine Jesu» (Господи Иисусе) и «Hostia» (Жертвы тебе, Господи) – подводили к обряду над усопшим. С этого момента мотивы скорби отстранялись, поэтому завершалась заупокойная католическая обедня обычными частями «Sanctus» и «Agnus Dei».

Такая последовательность молитв образует 4 традиционных раздела:

- вступительный (т.н. «интроитус») – «Requiem aeternam» и «Kyrie»;

- основной – «Dies irae»;

- «офферториум» (обряд приношения даров) – «Domine Jesu» и «Hostia»;

- заключительный – «Sanctus» и «Agnus Dei».

В своей трактовке формы траурной мессы Моцарт соблюдал эти сложившиеся традиции. В его Реквиеме тоже 4 раздела. В I разделе – один номер, во II – 6 (№№ 2 – 7), в III – два (№№ 8 и 9), в IV – три (№№ 10–12). Музыка последнего раздела в значительной мере принадлежит Зюсмайру, хотя и здесь использованы моцартовские темы. В заключительном номере повторен материал первого хора (средний раздел и реприза).

В чередовании номеров ясно прослеживается единая драматургическая линия со вступлением и экспозицией (№ 1), кульминационной зоной (№№ 6 и 7), переключением в контрастную образную сферу (№ 10 – «Sanctus» и № 11 – «Benedictus») и заключением (№ 12 – «Agnus Dei»). Из 12 номеров Реквиема девять хоровых, три (№№ 3, 4, 11) звучат в исполнении квартета солистов.

Основная тональность Реквиема d-moll (у Моцарта – трагическая, роковая). В этой тональности написаны важнейшие в драматургическом плане номера – 1, 2, 7 и 12.

Всю музыку Реквиема скрепляют интонационные связи. Сквозную роль играют секундовые обороты и опевание тоники вводными тонами (появляются в первой же теме).

Исполнительский состав

4-х голосный хор, квартет солистов, орган, большой оркестр: обычный состав струнных, в группе дер-духовых отсутствуют флейты и гобои, зато введены бассетгорны (разновидность кларнета с несколько сумрачным тембром); в группе медных нет валторн, только трубы с тромбонами; литавры.

Таким образом, оркестровка несколько темная, сумрачная, но вместе с тем, обладающая большой мощью.

Содержание

Содержание Реквиема предопределено самим жанром траурной мессы. Оно перекликается с содержанием пассионов. Реквием пронизывает мысль о смерти, ее трагической неотвратимости. Этот образ не раз будил творческое воображение Моцарта («Дон Жуан»). Но если в «Дон Жуане» образ потустороннего мира, загадочного небытия постоянно противопоставлялся бурному кипению жизни с ее сложностями, то здесь всё обыденное отступает на второй план. Остается главное: безысходная боль прощания с жизнью, понятная каждому человеку, и раскрытая с потрясающей искренностью. При этом тон моцартовского Реквиема очень далек от традиционной сдержанности, объективности церковной музыки.

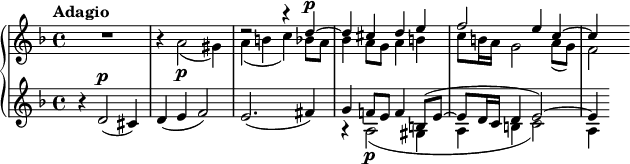

№ 1 состоит из двух частей, соотношение которых отчасти напоминает полифонические циклы Баха. Плавная медленная музыка I–й, вступительной части, в целом проникнута трагически-скорбным настроением. Однако в ней есть и моменты просветления (связанные с содержанием текста).

В сопровождении совсем простого аккомпанемента струнных (с запаздывающими аккордами) у бассетгорнов и фаготов раздается тема «Requiem» – одна из важнейших в произведении: тоника с нижним вводным тоном и постепенное восхождение к терции – в традиционном церковном стиле. Основное настроение – сдержанная скорбь, которая заметно нарастает с 3 такта (неравномерные вступления голосов и восходящая устремленность мелодической линии). Хоровые голоса вступают в восходящей последовательности начиная от баса. При этом тема «Requiem» проводится стреттно. Вся манера имитационного ведения темы явно обнаруживает влияние Баха.

II-я – центральная часть – представляет собой стремительную драматическую фугу на две темы. Обе темы, звучащие одновременно, трактованы в духе Баха и Генделя, опираются на типичные для эпохи барокко интонация (ум.7). Но на основе совсем обычного, типического материала создается в высшей степени индивидуальное творение. В фуге нет длинных интермедий, вместо них – краткие переходы (в основном на второй теме). Фуга стремится таким неудержимым потоком, что ее структура не позволяет совершить хотя бы одну остановку.

Музыка № 2 рисует картину светопреставления. Моцарт близок здесь к громовым хорам Генделя. Тремоло струнных, сигналы труб и дробь литавр создают впечатление грандиозной силы. Партия хора, за единственным исключением, трактуется как монолитная масса: все голоса соединяются в обрывочные аккордовые фразы. На фоне мощных аккордов выделяются широкие скачки верхнего голоса, подобные исступленным возгласам отчаяния. На долю оркестра приходится отображение внешних ужасов (тремоло струнных, сигналы труб и дробь литавр делают картину особенно зловещей, усиливают впечатление смертельного страха, лихорадочной тревоги, леденящего ужаса). Связь с темой «Requiem» – такты 4-6. Развитие музыки идет на «одном дыхании».

Лишь в самом конце хор впервые делится на две группы: звучит своеобразный диалог между грозными восклицаниями басов (мотив, в котором звук «а» окружается вводными тонами) и стонущими, полными смятения, ответными интонациями женских голосов и теноров.

После этого неистового возбуждения в № 3 наступает тишина. Хор уступает место солистам. Торжественный сигнал тромбона возвещает начало Божьего суда. Инструментальную мелодию подхватывает солирующий бас, затем поочередно тенор, альт и сопрано (восходящая последовательность)

№ 4 – прозрачный, светлый лирический квартет солистов.

№ 6 – своим драматизмом перекликается с № 2 и № 4. Изображение мучений обреченных. На фоне бурлящего сопровождения канонически вступают басы и тенора. Им противопоставляются молящие фразы высоких голосов («Voca me» – «призови меня»).

Конец номера – уникальный для XVIII века образец гармонического новаторства. Это ряд энгармонических модуляций a-moll → as-moll → g-moll → ges-moll → F-dur. Музыкальная символика – впечатление погружения в бездну.

№ 7 – лирический центр произведения, выражение чистой, возвышенной скорби. На смену страшным угрозам и гневу приходят предельно искренние, благодатные слезы. После краткого вступления (без басов), основанного на интонациях вздоха, вступает проникновенно-простая мелодия в вальсообразном ритме на 12/8. Все хоровые партии объединяются в стройный квартет голосов, выражающих одно настроение. Выделяется верхний – самый песенный голос. Такой материал – единственный раз во всем реквиеме. Мотивы вздохов лежат в основе и вокальных партий, и в оркестровом сопровождении. Тембр тромбонов.

Последующие части Реквиема завершают «драму». Среди них есть и умиротворенные, просветленные («Benedictus»), и торжественно-ликующие («Sanctus» и «Osanna»).

Текст реквиема

|

№ 1 Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis, te decet hymnus, Deus in Sion, et tibi reddetur votum in Jerusalem, exaudi orationem meam, ad te omnis caro veniet, Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis. Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison, Kyrie eleison. |

Вечный покой даруй им Господи, вечный свет да воссияет им. Тебе подобают гимны, Господь, в Сионе, тебе возносят молитвы в Иерусалиме, внемли молениям моим, к тебе всякая плоть приходит, Вечный покой даруй им, Господи, вечный свет да воссияет им. Господи, помилуй, Христе, помилуй, Господи, помилуй. |

|

№ 2 Dies irae, dies illa solvet saectum in favilla, teste David cum Sybilla. Quantus tremor est futurus, quando judex est venturus, cuncta stricte discussurus. |

День гнева, тот день расточит вселенную во прах, так свидетельствует Давид и Сивилла. Как велик будет трепет, как придет судья, чтобы всех подвергнуть суду. |

|

№ 3 Tuba mirum spargens sonum per sepulchra regionum, coget omnes ante thronum. Mors stupebit et natura, cum resurget creatura, judicanti resposura. Liber scriptus proferetur, in quo totum continetur, unde mundus judicetur. Judex ergo cum sedebit, quidquid later apparebit, nil inultum remanebit. Quit sum miser tunc dicturus? Quem patronum rogaturus, cum vix Justus sit securus? |

Труба чудесная, разнося клич по гробницам всех стран, всех соберет к трону. Смерть и природа застынут в изумлении, когда восстанет творение, чтобы дать ответ судии. Принесут записанную книгу, в которой заключено всё, по которой будет вынесен приговор. Итак, судия воссядет и все тайное станет явным и ничто не останется без отмщения. Что я, жалкий, буду говорить тогда? К какому заступнику обращусь, когда лишь праведный будет избавлен от страха? |

|

№ 4 Rex tremendae mjestatis, qui salvandos salvas gratis, salva me, fons pietatis. |

Царь грозного величия, спасающий тех, кто достоин спасения, спаси меня, источник милосердия. |

|

№ 5 Recordare Jesu pie, quod sum causa tuae viae, ne me perdas illa die. Quaerens me sedisti lassus, redemisti crucem passus, tantus labor non sit cassus. Juste judex ultionis, donum fac remissionis ante diem rationis. Ingemisco tanquam reus, culpa rubet vultus meus, supplicanti parce, Deus. Qui Mariam absolvisti, et latronem exaudisti, mihi quoque spem dedisti. Preces meae non sunt dignae, sed tu, bonus, fac benigne, ne perenni cremer igne. Inter oves locum praestra, et ab hoedis me sequestra, statuens in parte dextra. |

Вспомни, милостивый Иисусе, ты прошел свой путь, чтобы я не погиб в этот день. Меня, сидящего в унынии, искупил крестным страданием, пусть же эти муки не будут тщетными. Праведный судия возмездия, даруй мне прощение перед лицом судного дня. Я стенаю, как осужденный, от вины пылает лицо мое, пощади, Боже, молящего! Простивший Марию, выслушавший разбойника, ты и мне подал надежду. Недостойны мои мольбы, но ты, справедливый, сотвори благость, не дай мне вечно гореть в огне. Среди агнцев дай мне место, и от козлищ меня отдели, поставив в сторону правую. |

|

№ 6 Confutatis maledictis, flammis acribus addicis, voca me cum benedictis. Oro supplex et acclinis, cor contritum quasi cinis, gere curam mei finis. |

Сокрушив отверженных, приговоренных гореть в огне, призови меня с благословенными. Я молю, преклонив колени и чело, мое сердце в смятении подобно праху. Осени заботой мой конец. |

|

№ 7 Lacrymosa deis illa, qua resurget ex favilla judicandus homo reus. Huic ergo parce Deus, pie Jesu Domine, dona eis requiem! Amen! |

Слезный будет тот день, когда восстанет из пепла человек, судимый за его грехи. Пощади же его, Боже, милостивый Господи Иисусе, даруй ему покой! Аминь! |

|

№ 8 Domine Jesu Christe! Rex gloriae! Libera animas omnium fidelium defunctorum de poenis inferni et de pofundo lacu! Libera eas de ore leonis, ne absorbeat eas Tartarus, ne cadant in obscurum: sed signifier sanctus Michael repraesentet eas in lucem sanctam, quam olim Abrahae promisisti, et semini ejus. |

Господи Иисусе! Царь славы! Избавь души всех верных усопших от мук ада и глубины бездны! Избавь их от пасти льва, не поглотит их преисподняя, не попадут во тьму: знаменосец святого воинства Михаил представит их в свету святому, ибо так ты обещал Аврааму и потомству его. |

|

№ 9 Hostias et precet tibi, Domine, laudis offerimus. Tu suscipe pro animabus illis, quarum hodie memoriam facimus: face eas, Domine, de morte transire ad vitam, quam olim Abrahae promisisti, et semini ejus. |

Жертвы и молитвы тебе, Господи, восхваляя приносим. Прими их ради душ тех, которых поминаем ныне. Дай им, Господи, от смерти перейти к жизни, ибо так ты обещал Аврааму и потомству его. |

|

№ 10 Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus Dominus Deus Sabaoth! Pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua. Osanna in excelsis. |

Свят, свят, свят, Господь Бог Саваоф! Небо и земля полны славы твоей! Осанна в вышних! |

|

№ 11 Benedictus, qui venit in nominee Domini. Osanna in excelsis. |

Благословен, грядущий во имя Господне! Осанна в вышних. |

|

№ 12 Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem. Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona eis requiem sempiternam. Lux aeterna luceat eis, Domine, cum sanctis in aeternum, quia pius es. Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domini, et lux perpetua luceat eis. |

Агнец Божий, взявший на себя грехи мира, даруй им покой! Агнец Божий, взявший на себя грехи мира, даруй им покой на веки! Свет навсегда воссияет им, Господи, со святыми в вечности, ибо милосерден ты. Вечный покой даруй им, Господи, свет вечный да воссияет им. |

Где купить

| Николаус Арнонкур. (Mozart. Requiem K626 / Coronation Mass, K317) | Сборник 2009 г. Warner Classics | Купить |

| Requiem | |

|---|---|

| by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart completed by Franz Xaver Süssmayr |

|

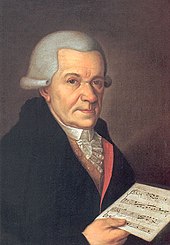

Mozart in 1781 |

|

| Key | D minor |

| Catalogue | K. 626 |

| Text | Requiem |

| Language | Latin |

| Composed | 1791 (Süssmayr completion finished 1792) |

| Scoring |

|

The Requiem in D minor, K. 626, is a requiem mass by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791). Mozart composed part of the Requiem in Vienna in late 1791, but it was unfinished at his death on 5 December the same year. A completed version dated 1792 by Franz Xaver Süssmayr was delivered to Count Franz von Walsegg, who commissioned the piece for a requiem service on 14 February 1792 to commemorate the first anniversary of the death of his wife Anna at the age of 20 on 14 February 1791.

The autograph manuscript shows the finished and orchestrated Introit in Mozart’s hand, and detailed drafts of the Kyrie and the sequence Dies irae as far as the first eight bars of the Lacrymosa movement, and the Offertory. It cannot be shown to what extent Süssmayr may have depended on now lost «scraps of paper» for the remainder; he later claimed the Sanctus and Benedictus and the Agnus Dei as his own.

Walsegg probably intended to pass the Requiem off as his own composition, as he is known to have done with other works. This plan was frustrated by a public benefit performance for Mozart’s widow Constanze. She was responsible for a number of stories surrounding the composition of the work, including the claims that Mozart received the commission from a mysterious messenger who did not reveal the commissioner’s identity, and that Mozart came to believe that he was writing the requiem for his own funeral.

In addition to the Süssmayr version, a number of alternative completions have been developed by composers and musicologists in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Instrumentation[edit]

The Requiem is scored for 2 basset horns in F, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets in D, 3 trombones (alto, tenor, and bass), timpani (2 drums), violins, viola, and basso continuo (cello, double bass, and organ). The basset horn parts are sometimes played on conventional clarinets, even though this changes the sonority.

The vocal forces consist of soprano, contralto, tenor, and bass soloists and an SATB mixed choir.

Structure[edit]

The first page of Mozart’s autograph score

Süssmayr’s completion divides the Requiem into eight sections:

- Introitus

-

- Requiem aeternam

- Kyrie

- Sequentia

-

- Dies irae

- Tuba mirum

- Rex tremendae

- Recordare

- Confutatis

- Lacrymosa

- Offertorium

-

- Domine Jesu

- Hostias

- Sanctus

- Benedictus

- Agnus Dei

- Communio

-

- Lux aeterna

- Cum sanctis tuis

All sections from the Sanctus onwards are not present in Mozart’s manuscript fragment. Mozart may have intended to include the Amen fugue at the end of the Sequentia, but Süssmayr did not do so in his completion.

The following table shows for the eight sections in Süssmayr’s completion with their subdivisions: the title, vocal parts (solo soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T) and bass (B) [in bold] and four-part choir SATB), tempo, key, and meter.

-

Section Title Vocal Tempo Key Meter I. Introitus Requiem aeternam SSATB Adagio D minor 4

4II. Kyrie Kyrie eleison SATB Allegro D minor 4

4III. Sequentia Dies irae SATB Allegro assai D minor 4

4Tuba mirum SATB Andante B♭ major 2

2Rex tremendae SATB – G minor – D minor 4

4Recordare SATB – F major 3

4Confutatis SATB Andante A minor – F major 4

4Lacrymosa SATB Larghetto D minor 12

8IV. Offertorium Domine Jesu SATBSATB Andante con moto G minor 4

4Hostias SATB Andante – Andante con moto E♭ major – G minor 3

4 – 4

4V. Sanctus Sanctus SATB Adagio D major 4

4Hosanna Allegro 3

4VI. Benedictus Benedictus SATB Andante B♭ major 4

4Hosanna SATB Allegro VII. Agnus Dei Agnus Dei SATB D minor – B♭ major 3

4VIII. Communio Lux aeterna SSATB – B♭ major – D minor 4

4Cum sanctis tuis SATB Allegro

Music[edit]

I. Introitus[edit]

The Requiem begins with a seven-measure instrumental introduction, in which the woodwinds (first bassoons, then basset horns) present the principal theme of the work in imitative counterpoint. The first five measures of this passage (without the accompaniment) are shown below.

This theme is modeled after Handel’s The ways of Zion do mourn, HWV 264. Many parts of the work make reference to this passage, notably in the coloratura in the Kyrie fugue and in the conclusion of the Lacrymosa.

The trombones then announce the entry of the choir, which breaks into the theme, with the basses alone for the first measure, followed by imitation by the other parts. The chords play off syncopated and staggered structures in the accompaniment, thus underlining the solemn and steady nature of the music. A soprano solo is sung to the Te decet hymnus text in the tonus peregrinus. The choir continues, repeating the psalmtone while singing the Exaudi orationem meam section.[1] Then, the principal theme is treated by the choir and the orchestra in downward-gliding sixteenth-notes. The courses of the melodies, whether held up or moving down, change and interlace amongst themselves, while passages in counterpoint and in unison (e.g., Et lux perpetua) alternate; all this creates the charm of this movement, which finishes with a half cadence on the dominant.

II. Kyrie[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Kyrie follows without pause (attacca). It is a double fugue also on a Handelian theme: the subject is based on «And with his stripes we are healed» from Messiah, HWV 56 (with which Mozart was familiar given his work on a German-language version) and the counter-subject comes from the final chorus of the Dettingen Anthem, HWV 265. The first three measures of the altos and basses are shown below.

The contrapuntal motifs of the theme of this fugue include variations on the two themes of the Introit. At first, upward diatonic series of sixteenth-notes are replaced by chromatic series, which has the effect of augmenting the intensity. This passage shows itself to be a bit demanding in the upper voices, particularly for the soprano voice. A final portion in a slower (Adagio) tempo ends on an «empty» fifth, a construction which had during the classical period become archaic, lending the piece an ancient air.

III. Sequentia[edit]

a. Dies irae[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Dies irae («Day of Wrath») opens with a show of orchestral and choral might with tremolo strings, syncopated figures and repeated chords in the brass. A rising chromatic scurry of sixteenth-notes leads into a chromatically rising harmonic progression with the chorus singing «Quantus tremor est futurus» («what trembling there will be» in reference to the Last Judgment). This material is repeated with harmonic development before the texture suddenly drops to a trembling unison figure with more tremolo strings evocatively painting the «Quantus tremor» text.

b. Tuba mirum[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

Mozart’s textual inspiration is again apparent in the Tuba mirum («Hark, the trumpet») movement, which is introduced with a sequence of three notes in arpeggio, played in B♭ major by a solo tenor trombone, unaccompanied, in accordance with the usual German translation of the Latin tuba, Posaune (trombone). Two measures later, the bass soloist enters, imitating the same theme. At m. 7, there is a fermata, the only point in all the work at which a solo cadence occurs. The final quarter notes of the bass soloist herald the arrival of the tenor, followed by the alto and soprano in dramatic fashion.

On the text Cum vix justus sit securus («When only barely may the just one be secure»), there is a switch to a homophonic segment sung by the quartet at the same time, articulating, without accompaniment, the cum and vix on the «strong» (1st and 3rd), then on the «weak» (2nd and 4th) beats, with the violins and continuo responding each time; this «interruption» (which one may interpret as the interruption preceding the Last Judgment) is heard sotto voce, forte and then piano to bring the movement finally into a crescendo into a perfect cadence.

c. Rex tremendae[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

A descending melody composed of dotted notes is played by the orchestra to announce the Rex tremendae majestatis («King of tremendous majesty», i.e., God), who is called by powerful cries from the choir on the syllable Rex during the orchestra’s pauses. For a surprising effect, the Rex syllables of the choir fall on the second beats of the measures, even though this is the «weak» beat. The choir then adopts the dotted rhythm of the orchestra, forming what Wolff calls baroque music’s form of «topos of the homage to the sovereign»,[2] or, more simply put, that this musical style is a standard form of salute to royalty, or, in this case, divinity. This movement consists of only 22 measures, but this short stretch is rich in variation: homophonic writing and contrapuntal choral passages alternate many times and finish on a quasi-unaccompanied choral cadence, landing on an open D chord (as seen previously in the Kyrie).

d. Recordare[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

At 130 measures, the Recordare («Remember») is the work’s longest movement, as well as the first in triple meter (3

4); the movement is a setting of no fewer than seven stanzas of the Dies irae. The form of this piece is somewhat similar to sonata form, with an exposition around two themes (mm. 1–37), a development of two themes (mm. 38–92) and a recapitulation (mm. 93–98).

In the first 13 measures, the basset horns are the first the present the first theme, clearly inspired by Wilhelm Friedemann Bach’s Sinfonia in D Minor,[3] the theme is enriched by a magnificent counterpoint by cellos in descending scales that are reprised throughout the movement. This counterpoint of the first theme prolongs the orchestral introduction with chords, recalling the beginning of the work and its rhythmic and melodic shiftings (the first basset horn begins a measure after the second but a tone higher, the first violins are likewise in sync with the second violins but a quarter note shifted, etc.). The introduction is followed by the vocal soloists; their first theme is sung by the alto and bass (from m. 14), followed by the soprano and tenor (from m. 20). Each time, the theme concludes with a hemiola (mm. 18–19 and 24–25). The second theme arrives on Ne me perdas, in which the accompaniment contrasts with that of the first theme. Instead of descending scales, the accompaniment is limited to repeated chords. This exposition concludes with four orchestral measures based on the counter-melody of the first theme (mm. 34–37).

The development of these two themes begins in m. 38 on Quaerens me; the second theme is not recognizable except by the structure of its accompaniment. At m. 46, it is the first theme that is developed beginning from Tantus labor and concludes with two measures of hemiola at mm. 50–51. After two orchestral bars (mm. 52–53), the first theme is heard again on the text Juste Judex and ends on a hemiola in mm. 66–67. Then, the second theme is reused on ante diem rationis; after the four measures of orchestra from 68 to 71, the first theme is developed alone.

The recapitulation intervenes in m. 93. The initial structure reproduces itself with the first theme on the text Preces meae and then in m. 99 on Sed tu bonus. The second theme reappears one final time on m. 106 on Sed tu bonus and concludes with three hemiolas. The final measures of the movement recede to simple orchestral descending contrapuntal scales.

e. Confutatis[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Confutatis («From the accursed») begins with a rhythmic and dynamic sequence of strong contrasts and surprising harmonic turns. Accompanied by the basso continuo, the tenors and basses burst into a forte vision of the infernal, on a dotted rhythm. The accompaniment then ceases alongside the tenors and basses, and the sopranos and altos enter softly and sotto voce, singing Voca me cum benedictis («Call upon me with the blessed») with an arpeggiated accompaniment in strings.

Finally, in the following stanza (Oro supplex et acclinis), there is a striking modulation from A minor to A♭ minor.

This spectacular descent from the opening key is repeated, now modulating to the key of F major. A final dominant seventh chord leads to the Lacrymosa.

f. Lacrymosa[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The chords begin piano on a rocking rhythm in 12

8, intercut with quarter rests, which will be reprised by the choir after two measures, on Lacrimosa dies illa («This tearful day»). Then, after two measures, the sopranos begin a diatonic progression, in disjointed eighth-notes on the text resurget («will be reborn»), then legato and chromatic on a powerful crescendo. The choir is forte by m. 8, at which point Mozart’s contribution to the movement is interrupted by his death.

Süssmayr brings the choir to a reference of the Introit and ends on an Amen cadence. Discovery of a fragmentary Amen fugue in Mozart’s hand has led to speculation that it may have been intended for the Requiem. Indeed, many modern completions (such as Levin’s) complete Mozart’s fragment. Some sections of this movement are quoted in the Requiem mass of Franz von Suppé, who was a great admirer of Mozart. Ray Robinson, the music scholar and president (from 1969 to 1987) of the Westminster Choir College, suggests that Süssmayr used materials from Credo of one of Mozart’s earlier masses, Mass in C major, K. 220 «Sparrow» in completing this movement.[4]

IV. Offertorium[edit]

a. Domine Jesu[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The first movement of the Offertorium, the Domine Jesu, begins on a piano theme consisting of an ascending progression on a G minor triad. This theme will later be varied in various keys, before returning to G minor when the four soloists enter a canon on Sed signifer sanctus Michael, switching between minor (in ascent) and major (in descent). Between these thematic passages are forte phrases where the choir enters, often in unison and dotted rhythm, such as on Rex gloriae («King of glory») or de ore leonis («[Deliver them] from the mouth of the lion»). Two choral fugues follow, on ne absorbeat eas tartarus, ne cadant in obscurum («may Tartarus not absorb them, nor may they fall into darkness») and Quam olim Abrahae promisisti et semini eius («What once to Abraham you promised and to his seed»). The movement concludes homophonically in G major.

b. Hostias[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Hostias opens in E♭ major in 3

4, with fluid vocals. After 20 measures, the movement switches to an alternation of forte and piano exclamations of the choir, while progressing from B♭ major towards B♭ minor, then F major, D♭ major, A♭ major, F minor, C minor and E♭ major. An overtaking chromatic melody on Fac eas, Domine, de morte transire ad vitam («Make them, O Lord, cross over from death to life») finally carries the movement into the dominant of G minor, followed by a reprise of the Quam olim Abrahae promisisti et semini eius fugue.

The words «Quam olim da capo» are likely to have been the last Mozart wrote; this portion of the manuscript has been missing since it was stolen at 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels by a person whose identity remains unknown.

Süssmayr’s additions[edit]

V. Sanctus[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Sanctus is the first movement written entirely by Süssmayr, and the only movement of the Requiem to have a key signature with sharps: D major, generally used for the entry of trumpets in the Baroque era. After a succinct glorification of the Lord follows a short fugue in 3

4 on Hosanna in excelsis («Glory [to God] in the highest»), noted for its syncopated rhythm, and for its motivic similarity to the Quam olim Abrahae fugue.

VI. Benedictus[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Benedictus, a quartet, adopts the key of the submediant, B♭ major (which can also be considered the relative of the subdominant of the key of D minor). The Sanctus’s ending on a D major cadence necessitates a mediant jump to this new key.

The Benedictus is constructed on three types of phrases: the (A) theme, which is first presented by the orchestra and reprised from m. 4 by the alto and from m. 6 by the soprano. The word benedictus is held, which stands in opposition with the (B) phrase, which is first seen at m. 10, also on the word benedictus but with a quick and chopped-up rhythm. The phrase develops and rebounds at m. 15 with a broken cadence. The third phrase, (C), is a solemn ringing where the winds respond to the chords with a staggering harmony, as shown in a Mozartian cadence at mm. 21 and 22, where the counterpoint of the basset horns mixes with the line of the cello. The rest of the movement consists of variations on this writing. At m. 23, phrase (A) is reprised on a F pedal and introduces a recapitulation of the primary theme from the bass and tenor from mm. 28 and 30, respectively. Phrase (B) follows at m. 33, although without the broken cadence, then repeats at m. 38 with the broken cadence once more. This carries the movement to a new Mozartian cadence in mm. 47 to 49 and concludes on phrase (C), which reintroduces the Hosanna fugue from the Sanctus movement, in the new key of the Benedictus.

VII. Agnus Dei[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

Homophony dominates the Agnus Dei. The text is repeated three times, always with chromatic melodies and harmonic reversals, going from D minor to F major, C major, and finally B♭ major. According to the musicologist Simon P. Keefe, Süssmayr likely referenced one of Mozart’s earlier masses, Mass in C major, K. 220 «Sparrow» in completing this movement.[5]

VIII. Communio[edit]

Süssmayr here reuses Mozart’s first two movements, almost exactly note for note, with wording corresponding to this part of the liturgy.

History[edit]

Composition[edit]

The beginning of the Dies irae in the autograph manuscript, with Eybler’s orchestration. In the upper right, Nissen has left a note: «All which is not enclosed by the quill is of Mozart’s hand up to page 32.» The first violin, choir and figured bass are entirely Mozart’s.

At the time of Mozart’s death on 5 December 1791, only the first movement, Introitus (Requiem aeternam) was completed in all of the orchestral and vocal parts. The Kyrie, Sequence and Offertorium were completed in skeleton, with the exception of the Lacrymosa, which breaks off after the first eight bars. The vocal parts and continuo were fully notated. Occasionally, some of the prominent orchestral parts were briefly indicated, such as the first violin part of the Rex tremendae and Confutatis, the musical bridges in the Recordare, and the trombone solos of the Tuba Mirum.

What remained to be completed for these sections were mostly accompanimental figures, inner harmonies, and orchestral doublings to the vocal parts.

Completion by Mozart’s contemporaries[edit]

The eccentric count Franz von Walsegg commissioned the Requiem from Mozart anonymously through intermediaries. The count, an amateur chamber musician who routinely commissioned works by composers and passed them off as his own,[6][7] wanted a Requiem Mass he could claim he composed to memorialize the recent passing of his wife. Mozart received only half of the payment in advance, so upon his death his widow Constanze was keen to have the work completed secretly by someone else, submit it to the count as having been completed by Mozart and collect the final payment.[8] Joseph von Eybler was one of the first composers to be asked to complete the score, and had worked on the movements from the Dies irae up until the Lacrymosa. In addition, a striking similarity between the openings of the Domine Jesu Christe movements in the requiems of the two composers suggests that Eybler at least looked at later sections.[further explanation needed] After this work, he felt unable to complete the remainder and gave the manuscript back to Constanze Mozart.

The task was then given to another composer, Franz Xaver Süssmayr. Süssmayr borrowed some of Eybler’s work in making his completion, and added his own orchestration to the movements from the Kyrie onward, completed the Lacrymosa, and added several new movements which a Requiem would normally comprise: Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei. He then added a final section, Lux aeterna by adapting the opening two movements which Mozart had written to the different words which finish the Requiem mass, which according to both Süssmayr and Mozart’s wife was done according to Mozart’s directions. Some people[who?] consider it unlikely, however, that Mozart would have repeated the opening two sections if he had survived to finish the work.

Other composers may have helped Süssmayr. The Agnus Dei is suspected by some scholars[9] to have been based on instruction or sketches from Mozart because of its similarity to a section from the Gloria of a previous mass (Sparrow Mass, K. 220) by Mozart,[10] as was first pointed out by Richard Maunder. Others have pointed out that at the beginning of the Agnus Dei, the choral bass quotes the main theme from the Introitus.[11] Many of the arguments dealing with this matter, though, center on the perception that if part of the work is high quality, it must have been written by Mozart (or from sketches), and if part of the work contains errors and faults, it must have been all Süssmayr’s doing.[12]

Another controversy is the suggestion (originating from a letter written by Constanze) that Mozart left explicit instructions for the completion of the Requiem on «a few scraps of paper with music on them… found on Mozart’s desk after his death.»[13] The extent to which Süssmayr’s work may have been influenced by these «scraps» if they existed at all remains a subject of speculation amongst musicologists to this day.

The completed score, initially by Mozart but largely finished by Süssmayr, was then dispatched to Count Walsegg complete with a counterfeited signature of Mozart and dated 1792. The various complete and incomplete manuscripts eventually turned up in the 19th century, but many of the figures involved left ambiguous statements on record as to how they were involved in the affair. Despite the controversy over how much of the music is actually Mozart’s, the commonly performed Süssmayr version has become widely accepted by the public. This acceptance is quite strong, even when alternative completions provide logical and compelling solutions for the work.

Promotion by Constanze Mozart[edit]

The confusion surrounding the circumstances of the Requiem’s composition was created in a large part by Mozart’s wife, Constanze. Constanze had a difficult task in front of her: she had to keep secret the fact that the Requiem was unfinished at Mozart’s death, so she could collect the final payment from the commission. For a period of time, she also needed to keep secret the fact that Süssmayr had anything to do with the composition of the Requiem at all, in order to allow Count Walsegg the impression that Mozart wrote the work entirely himself. Once she received the commission, she needed to carefully promote the work as Mozart’s so that she could continue to receive revenue from the work’s publication and performance. During this phase of the Requiem’s history, it was still important that the public accept that Mozart wrote the whole piece, as it would fetch larger sums from publishers and the public if it were completely by Mozart.[14]

It is Constanze’s efforts that created the flurry of half-truths and myths almost instantly after Mozart’s death. According to Constanze, Mozart declared that he was composing the Requiem for himself and that he had been poisoned. His symptoms worsened, and he began to complain about the painful swelling of his body and high fever. Nevertheless, Mozart continued his work on the Requiem, and even on the last day of his life, he was explaining to his assistant how he intended to finish the Requiem.

With multiple levels of deception surrounding the Requiem’s completion, a natural outcome is the mythologizing which subsequently occurred. One series of myths surrounding the Requiem involves the role Antonio Salieri played in the commissioning and completion of the Requiem (and in Mozart’s death generally). While the most recent retelling of this myth is Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus and the movie made from it, it is important to note that the source of misinformation was actually a 19th-century play by Alexander Pushkin, Mozart and Salieri, which was turned into an opera by Rimsky-Korsakov and subsequently used as the framework for the play Amadeus.[15]

Conflicting accounts[edit]

Source materials written soon after Mozart’s death contain serious discrepancies, which leave a level of subjectivity when assembling the «facts» about Mozart’s composition of the Requiem. For example, at least three of the conflicting sources, all dated within two decades following Mozart’s death, cite Constanze as their primary source of interview information.

Friedrich Rochlitz[edit]

In 1798, Friedrich Rochlitz, a German biographical author and amateur composer, published a set of Mozart anecdotes that he claimed to have collected during his meeting with Constanze in 1796.[16] The Rochlitz publication makes the following statements:

- Mozart was unaware of his commissioner’s identity at the time he accepted the project.

- He was not bound to any date of completion of the work.

- He stated that it would take him around four weeks to complete.

- He requested, and received, 100 ducats at the time of the first commissioning message.

- He began the project immediately after receiving the commission.

- His health was poor from the outset; he fainted multiple times while working.

- He took a break from writing the work to visit the Prater with his wife.

- He shared the thought with his wife that he was writing this piece for his own funeral.

- He spoke of «very strange thoughts» regarding the unpredicted appearance and commission of this unknown man.

- He noted that the departure of Leopold II to Prague for the coronation was approaching.

The most highly disputed of these claims is the last one, the chronology of this setting. According to Rochlitz, the messenger arrives quite some time before the departure of Leopold for the coronation, yet there is a record of his departure occurring in mid-July 1791. However, as Constanze was in Baden during all of June to mid-July, she would not have been present for the commission or the drive they were said to have taken together.[16] Furthermore, The Magic Flute (except for the Overture and March of the Priests) was completed by mid-July. La clemenza di Tito was commissioned by mid-July.[16] There was no time for Mozart to work on the Requiem on the large scale indicated by the Rochlitz publication in the time frame provided.

Franz Xaver Niemetschek[edit]

1857 lithograph by Franz Schramm, titled Ein Moment aus den letzten Tagen Mozarts («Moment from the Last Days of Mozart»). Mozart, with the score of the Requiem on his lap, gives Süssmayr last-minute instructions. Constanze is to the side and the messenger is leaving through the main door.[17]

Also in 1798, Constanze is noted to have given another interview to Franz Xaver Niemetschek,[18] another biographer looking to publish a compendium of Mozart’s life. He published his biography in 1808, containing a number of claims about Mozart’s receipt of the Requiem commission:

- Mozart received the commission very shortly before the Coronation of Emperor Leopold II and before he received the commission to go to Prague.

- He did not accept the messenger’s request immediately; he wrote the commissioner and agreed to the project stating his fee but urging that he could not predict the time required to complete the work.

- The same messenger appeared later, paying Mozart the sum requested plus a note promising a bonus at the work’s completion.

- He started composing the work upon his return from Prague.

- He fell ill while writing the work

- He told Constanze «I am only too conscious… my end will not be long in coming: for sure, someone has poisoned me! I cannot rid my mind of this thought.»

- Constanze thought that the Requiem was overstraining him; she called the doctor and took away the score.

- On the day of his death, he had the score brought to his bed.

- The messenger took the unfinished Requiem soon after Mozart’s death.

- Constanze never learned the commissioner’s name.

This account, too, has fallen under scrutiny and criticism of its accuracy. According to letters, Constanze most certainly knew the name of the commissioner by the time this interview was released in 1800.[18] Additionally, the Requiem was not given to the messenger until some time after Mozart’s death.[16] This interview contains the only account from Constanze herself of the claim that she took the Requiem away from Wolfgang for a significant duration during his composition of it.[16] Otherwise, the timeline provided in this account is historically probable.

Georg Nikolaus von Nissen[edit]

However, the most highly accepted text attributed to Constanze is the interview to her second husband, Georg Nikolaus von Nissen.[16] After Nissen’s death in 1826, Constanze released the biography of Wolfgang (1828) that Nissen had compiled, which included this interview. Nissen states:

- Mozart received the commission shortly before the coronation of Emperor Leopold and before he received the commission to go to Prague.

- He did not accept the messenger’s request immediately; he wrote the commissioner and agreed to the project stating his fee but urging that he could not predict the time required to complete the work.

- The same messenger appeared later, paying Mozart the sum requested plus a note promising a bonus at the work’s completion.

- He started composing the work upon his return from Prague.

The Nissen publication lacks information following Mozart’s return from Prague.[16]

Influences[edit]

Mozart esteemed Handel and in 1789 he was commissioned by Baron Gottfried van Swieten to rearrange Messiah (HWV 56). This work likely influenced the composition of Mozart’s Requiem; the Kyrie is based on the «And with His stripes we are healed» chorus from Handel’s Messiah, since the subject of the fugato is the same with only slight variations by adding ornaments on melismata.[19] However, the same four-note theme is also found in the finale of Haydn’s String Quartet in F minor (Op. 20 No. 5) and in the first measure of the A minor fugue from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier Book 2 (BWV 889b) as part of the subject of Bach’s fugue,[20] and it is thought that Mozart transcribed some of the fugues of the Well-Tempered Clavier for string ensemble (K. 404a Nos. 1–3 and K. 405 Nos. 1–5),[21] but the attribution of these transcriptions to Mozart is not certain.

Some musicologists believe that the Introitus was inspired by Handel’s Funeral Anthem for Queen Caroline, HWV 264. Another influence was Michael Haydn’s Requiem in C minor; Mozart and his father were viola and violin players respectively at its first three performances in January 1772. Some have noted that Michael Haydn’s Introitus sounds rather similar to Mozart’s, and the theme for Mozart’s «Quam olim Abrahae» fugue is a direct quote of the fugue theme from Haydn’s Offertorium and Versus from his aforementioned requiem. In Introitus m. 21, the soprano sings «Te decet hymnus Deus in Zion». It is quoting the Lutheran hymn «Meine Seele erhebt den Herren«. The melody is used by many composers e.g. in Bach’s cantata Meine Seel erhebt den Herren, BWV 10 but also in Michael Haydn’s Requiem.[22]

Felicia Hemans’ poem «Mozart’s Requiem» was first published in The New Monthly Magazine in 1828.[23]

Timeline[edit]

Modern completions[edit]

In the 1960s, a sketch for an Amen Fugue was discovered, which some musicologists (Levin, Maunder) believe belongs to the Requiem at the conclusion of the sequence after the Lacrymosa. H. C. Robbins Landon argues that this Amen Fugue was not intended for the Requiem, rather that it «may have been for a separate unfinished mass in D minor» to which the Kyrie K. 341 also belonged.[24]

There is, however, compelling evidence placing the Amen Fugue in the Requiem[25] based on current Mozart scholarship. First, the principal subject is the main theme of the Requiem (stated at the beginning, and throughout the work) in strict inversion. Second, it is found on the same page as a sketch for the Rex tremendae (together with a sketch for the overture of his last opera The Magic Flute), and thus surely dates from late 1791. The only place where the word ‘Amen’ occurs in anything that Mozart wrote in late 1791 is in the sequence of the Requiem. Third, as Levin points out in the foreword to his completion of the Requiem, the addition of the Amen Fugue at the end of the sequence results in an overall design that ends each large section with a fugue.

Since the 1970s several composers and musicologists, dissatisfied with the traditional «Süssmayr» completion, have attempted alternative completions of the Requiem.

Autograph at the 1958 World’s Fair[edit]

Mozart’s manuscript with missing corner

«quam olim d: c» in Mozart’s hand

The autograph of the Requiem was placed on display at the World’s Fair in 1958 in Brussels. At some point during the fair, someone was able to gain access to the manuscript, tearing off the bottom right-hand corner of the second to last page (folio 99r/45r), containing the words «Quam olim d: C:» (an instruction that the «Quam olim» fugue of the Domine Jesu was to be repeated da capo, at the end of the Hostias). The perpetrator has not been identified and the fragment has not been recovered.[26]

If the most common authorship theory is true, then «Quam olim d: C:» were the last words Mozart wrote before he died.

Recordings[edit]

Arrangements[edit]

The Requiem and its individual movements have been repeatedly arranged for various instruments. The keyboard arrangements notably demonstrate the variety of approaches taken to translating the Requiem, particularly the Confutatis and Lacrymosa movements, in order to balance preserving the Requiem’s character while also being physically playable. Karl Klindworth’s piano solo (c.1900), Muzio Clementi’s organ solo, and Renaud de Vilbac’s harmonium solo (c.1875) are liberal in their approach to achieve this. In contrast, Carl Czerny wrote his piano transcription for two players, enabling him to retain the extent of the score, if sacrificing timbral character. Franz Liszt’s piano solo (c.1865) departs the most in terms of fidelity and character of the Requiem, through its inclusion of composition devices used to showcase pianistic technique.[27]

References[edit]

- ^ Wolff, Christoph (1994). Mozart’s Requiem: Historical and Analytical Studies, Documents, Score. Translated by Mary Whittal. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-520-07709-1.

- ^ Wolff, Christoph (2003) [1991]. Mozarts Requiem. Geschichte, Musik, Dokumente. Mit Studienpartitur (in German) (4th ed.). Kassel: Bärenreiter. p. [page needed]. ISBN 3-7618-1242-6.

- ^ Wolff 1998, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Robinson, Ray (1 August 1985). «A New Mozart ‘Requiem’«. Choral Journal. 26 (1): 5–6. ProQuest 1306216012.

- ^ Keefe, Simon P. (2008). ««Die Ochsen am Berge»: Franx Xaver Süssmayr and the Orchestration of Mozart’s Requiem, K. 626″. Journal of the American Musicological Society. 61: 17. doi:10.1525/jams.2008.61.1.1.

- ^ Blom, Jan Dirk (2009). A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer. p. 342. ISBN 9781441912237.

- ^ Gehring, Franz Eduard (1883). Mozart (The Great Musicians). University of Michigan: S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. p. 124.

- ^ Wolff, Christoph (1994). Mozart’s Requiem. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780520077096.

- ^ Leeson, Daniel N. (2004). Opus Ultimum: The Story of the Mozart Requiem. New York: Algora. p. 79.

Mozart might have described specific instrumentation for the drafted sections, or the addition of a Sanctus, a Benedictus, and an Agnus Dei, telling Süssmayr he would be obliged to compose those sections himself.

- ^ Summer, R. J. (2007). Choral Masterworks from Bach to Britten: Reflections of a Conductor. Scarecrow Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8108-5903-6.

- ^ Mentioned in the CD booklet of the Requiem recording by Nikolaus Harnoncourt (2004).

- ^ Wolff 1998, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Keefe 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Moseley, Paul (1989). «Mozart’s Requiem; A Revaluation of the Evidence». Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 114 (2): 211. doi:10.1093/jrma/114.2.203. JSTOR 766531.

- ^ Gregory Allen Robbins. «Mozart & Salieri, Cain & Abel: A Cinematic Transformation of Genesis 4.», Journal of Religion and Film: vol. 1, no. 1, April 1997

- ^ a b c d e f g Landon, H. C. Robbins (1988). 1791: Mozart’s Last Year. New York: Schirmer Books.

- ^ Keefe, Simon P., ed. (2006). Mozart studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0521851025. OCLC 76850387.

- ^ a b Steve Boerner (December 16, 2000). «K. 626: Requiem in D Minor». The Mozart Project. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007.

- ^ «Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s ‘Kyrie Eleison, K. 626’«. WhoSampled.com. Discover the Sample Source. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ^ Dirst, Charles Matthew (2012). Engaging Bach: The Keyboard Legacy from Marpurg to Mendelssohn. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1107376281.

- ^ Köchel, Ludwig Ritter von (1862). Chronologisch-thematisches Verzeichniss sämmtlicher Tonwerke Wolfgang Amade Mozart’s (in German). Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. OCLC 3309798. Alt URL, No. 405, pp. 328–329

- ^ «Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s ‘Requiem in D Minor’«. WhoSampled.com. Discover the Sample Source. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ^ Hemans, Felicia (1828). «Mozart’s Requiem» . The New Monthly Magazine. 22: 325–326 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Wolff 1998, p. 30.

- ^ Moseley, Paul (1989). «Mozart’s Requiem: A Revaluation of the Evidence». Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 114 (2): 203–237. doi:10.1093/jrma/114.2.203. JSTOR 766531.

- ^ Facsimile of the manuscript’s last page, showing the missing corner Archived 2012-01-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Keefe 2012, p. 85.

Sources[edit]

- Keefe, Simon P. (2012). Mozart’s Requiem: Reception, Work, Completion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19837-0. OCLC 804845569.

- Wolff, Christoph (1998). Mozart’s Requiem: Historical and Analytical Studies, Documents, Score. Translated by Mary Whittall (revised, annotated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520213890.

Further reading[edit]

- Brendan Cormican (1991). Mozart’s death – Mozart’s requiem: an investigation. Belfast, Northern Ireland: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-9510357-0-3.

- Heinz Gärtner (1991). Constanze Mozart: after the Requiem. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-39-X.

- C. R. F. Maunder (1988). Mozart’s Requiem: On Preparing a New Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-316413-2.

- Christoph Wolff (1994). Mozart’s Requiem: Historical and Analytical Studies, Documents, Score. Translated by Mary Whittal. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07709-1.

External links[edit]

- Article on the Requiem at h2g2

- Michael Lorenz: «Freystädtler’s Supposed Copying in the Autograph of K. 626: A Case of Mistaken Identity», Vienna 2013

- Mozart’s Requiem, new completion of the score by musicologist Robert D. Levin, live concert

- Requiem: Score and critical report (in German) in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

- Eybler’s and Süssmayr’s amendments: Score in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe

- Free scores of Requiem, K. 626 in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Requiem in D minor, K. 626: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

| Requiem | |

|---|---|

| by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart completed by Franz Xaver Süssmayr |

|

Mozart in 1781 |

|

| Key | D minor |

| Catalogue | K. 626 |

| Text | Requiem |

| Language | Latin |

| Composed | 1791 (Süssmayr completion finished 1792) |

| Scoring |

|

The Requiem in D minor, K. 626, is a requiem mass by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791). Mozart composed part of the Requiem in Vienna in late 1791, but it was unfinished at his death on 5 December the same year. A completed version dated 1792 by Franz Xaver Süssmayr was delivered to Count Franz von Walsegg, who commissioned the piece for a requiem service on 14 February 1792 to commemorate the first anniversary of the death of his wife Anna at the age of 20 on 14 February 1791.

The autograph manuscript shows the finished and orchestrated Introit in Mozart’s hand, and detailed drafts of the Kyrie and the sequence Dies irae as far as the first eight bars of the Lacrymosa movement, and the Offertory. It cannot be shown to what extent Süssmayr may have depended on now lost «scraps of paper» for the remainder; he later claimed the Sanctus and Benedictus and the Agnus Dei as his own.

Walsegg probably intended to pass the Requiem off as his own composition, as he is known to have done with other works. This plan was frustrated by a public benefit performance for Mozart’s widow Constanze. She was responsible for a number of stories surrounding the composition of the work, including the claims that Mozart received the commission from a mysterious messenger who did not reveal the commissioner’s identity, and that Mozart came to believe that he was writing the requiem for his own funeral.

In addition to the Süssmayr version, a number of alternative completions have been developed by composers and musicologists in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Instrumentation[edit]

The Requiem is scored for 2 basset horns in F, 2 bassoons, 2 trumpets in D, 3 trombones (alto, tenor, and bass), timpani (2 drums), violins, viola, and basso continuo (cello, double bass, and organ). The basset horn parts are sometimes played on conventional clarinets, even though this changes the sonority.

The vocal forces consist of soprano, contralto, tenor, and bass soloists and an SATB mixed choir.

Structure[edit]

The first page of Mozart’s autograph score

Süssmayr’s completion divides the Requiem into eight sections:

- Introitus

-

- Requiem aeternam

- Kyrie

- Sequentia

-

- Dies irae

- Tuba mirum

- Rex tremendae

- Recordare

- Confutatis

- Lacrymosa

- Offertorium

-

- Domine Jesu

- Hostias

- Sanctus

- Benedictus

- Agnus Dei

- Communio

-

- Lux aeterna

- Cum sanctis tuis

All sections from the Sanctus onwards are not present in Mozart’s manuscript fragment. Mozart may have intended to include the Amen fugue at the end of the Sequentia, but Süssmayr did not do so in his completion.

The following table shows for the eight sections in Süssmayr’s completion with their subdivisions: the title, vocal parts (solo soprano (S), alto (A), tenor (T) and bass (B) [in bold] and four-part choir SATB), tempo, key, and meter.

-

Section Title Vocal Tempo Key Meter I. Introitus Requiem aeternam SSATB Adagio D minor 4

4II. Kyrie Kyrie eleison SATB Allegro D minor 4

4III. Sequentia Dies irae SATB Allegro assai D minor 4

4Tuba mirum SATB Andante B♭ major 2

2Rex tremendae SATB – G minor – D minor 4

4Recordare SATB – F major 3

4Confutatis SATB Andante A minor – F major 4

4Lacrymosa SATB Larghetto D minor 12

8IV. Offertorium Domine Jesu SATBSATB Andante con moto G minor 4

4Hostias SATB Andante – Andante con moto E♭ major – G minor 3

4 – 4

4V. Sanctus Sanctus SATB Adagio D major 4

4Hosanna Allegro 3

4VI. Benedictus Benedictus SATB Andante B♭ major 4

4Hosanna SATB Allegro VII. Agnus Dei Agnus Dei SATB D minor – B♭ major 3

4VIII. Communio Lux aeterna SSATB – B♭ major – D minor 4

4Cum sanctis tuis SATB Allegro

Music[edit]

I. Introitus[edit]

The Requiem begins with a seven-measure instrumental introduction, in which the woodwinds (first bassoons, then basset horns) present the principal theme of the work in imitative counterpoint. The first five measures of this passage (without the accompaniment) are shown below.

This theme is modeled after Handel’s The ways of Zion do mourn, HWV 264. Many parts of the work make reference to this passage, notably in the coloratura in the Kyrie fugue and in the conclusion of the Lacrymosa.

The trombones then announce the entry of the choir, which breaks into the theme, with the basses alone for the first measure, followed by imitation by the other parts. The chords play off syncopated and staggered structures in the accompaniment, thus underlining the solemn and steady nature of the music. A soprano solo is sung to the Te decet hymnus text in the tonus peregrinus. The choir continues, repeating the psalmtone while singing the Exaudi orationem meam section.[1] Then, the principal theme is treated by the choir and the orchestra in downward-gliding sixteenth-notes. The courses of the melodies, whether held up or moving down, change and interlace amongst themselves, while passages in counterpoint and in unison (e.g., Et lux perpetua) alternate; all this creates the charm of this movement, which finishes with a half cadence on the dominant.

II. Kyrie[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Kyrie follows without pause (attacca). It is a double fugue also on a Handelian theme: the subject is based on «And with his stripes we are healed» from Messiah, HWV 56 (with which Mozart was familiar given his work on a German-language version) and the counter-subject comes from the final chorus of the Dettingen Anthem, HWV 265. The first three measures of the altos and basses are shown below.

The contrapuntal motifs of the theme of this fugue include variations on the two themes of the Introit. At first, upward diatonic series of sixteenth-notes are replaced by chromatic series, which has the effect of augmenting the intensity. This passage shows itself to be a bit demanding in the upper voices, particularly for the soprano voice. A final portion in a slower (Adagio) tempo ends on an «empty» fifth, a construction which had during the classical period become archaic, lending the piece an ancient air.

III. Sequentia[edit]

a. Dies irae[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Dies irae («Day of Wrath») opens with a show of orchestral and choral might with tremolo strings, syncopated figures and repeated chords in the brass. A rising chromatic scurry of sixteenth-notes leads into a chromatically rising harmonic progression with the chorus singing «Quantus tremor est futurus» («what trembling there will be» in reference to the Last Judgment). This material is repeated with harmonic development before the texture suddenly drops to a trembling unison figure with more tremolo strings evocatively painting the «Quantus tremor» text.

b. Tuba mirum[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

Mozart’s textual inspiration is again apparent in the Tuba mirum («Hark, the trumpet») movement, which is introduced with a sequence of three notes in arpeggio, played in B♭ major by a solo tenor trombone, unaccompanied, in accordance with the usual German translation of the Latin tuba, Posaune (trombone). Two measures later, the bass soloist enters, imitating the same theme. At m. 7, there is a fermata, the only point in all the work at which a solo cadence occurs. The final quarter notes of the bass soloist herald the arrival of the tenor, followed by the alto and soprano in dramatic fashion.

On the text Cum vix justus sit securus («When only barely may the just one be secure»), there is a switch to a homophonic segment sung by the quartet at the same time, articulating, without accompaniment, the cum and vix on the «strong» (1st and 3rd), then on the «weak» (2nd and 4th) beats, with the violins and continuo responding each time; this «interruption» (which one may interpret as the interruption preceding the Last Judgment) is heard sotto voce, forte and then piano to bring the movement finally into a crescendo into a perfect cadence.

c. Rex tremendae[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

A descending melody composed of dotted notes is played by the orchestra to announce the Rex tremendae majestatis («King of tremendous majesty», i.e., God), who is called by powerful cries from the choir on the syllable Rex during the orchestra’s pauses. For a surprising effect, the Rex syllables of the choir fall on the second beats of the measures, even though this is the «weak» beat. The choir then adopts the dotted rhythm of the orchestra, forming what Wolff calls baroque music’s form of «topos of the homage to the sovereign»,[2] or, more simply put, that this musical style is a standard form of salute to royalty, or, in this case, divinity. This movement consists of only 22 measures, but this short stretch is rich in variation: homophonic writing and contrapuntal choral passages alternate many times and finish on a quasi-unaccompanied choral cadence, landing on an open D chord (as seen previously in the Kyrie).

d. Recordare[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

At 130 measures, the Recordare («Remember») is the work’s longest movement, as well as the first in triple meter (3

4); the movement is a setting of no fewer than seven stanzas of the Dies irae. The form of this piece is somewhat similar to sonata form, with an exposition around two themes (mm. 1–37), a development of two themes (mm. 38–92) and a recapitulation (mm. 93–98).

In the first 13 measures, the basset horns are the first the present the first theme, clearly inspired by Wilhelm Friedemann Bach’s Sinfonia in D Minor,[3] the theme is enriched by a magnificent counterpoint by cellos in descending scales that are reprised throughout the movement. This counterpoint of the first theme prolongs the orchestral introduction with chords, recalling the beginning of the work and its rhythmic and melodic shiftings (the first basset horn begins a measure after the second but a tone higher, the first violins are likewise in sync with the second violins but a quarter note shifted, etc.). The introduction is followed by the vocal soloists; their first theme is sung by the alto and bass (from m. 14), followed by the soprano and tenor (from m. 20). Each time, the theme concludes with a hemiola (mm. 18–19 and 24–25). The second theme arrives on Ne me perdas, in which the accompaniment contrasts with that of the first theme. Instead of descending scales, the accompaniment is limited to repeated chords. This exposition concludes with four orchestral measures based on the counter-melody of the first theme (mm. 34–37).

The development of these two themes begins in m. 38 on Quaerens me; the second theme is not recognizable except by the structure of its accompaniment. At m. 46, it is the first theme that is developed beginning from Tantus labor and concludes with two measures of hemiola at mm. 50–51. After two orchestral bars (mm. 52–53), the first theme is heard again on the text Juste Judex and ends on a hemiola in mm. 66–67. Then, the second theme is reused on ante diem rationis; after the four measures of orchestra from 68 to 71, the first theme is developed alone.

The recapitulation intervenes in m. 93. The initial structure reproduces itself with the first theme on the text Preces meae and then in m. 99 on Sed tu bonus. The second theme reappears one final time on m. 106 on Sed tu bonus and concludes with three hemiolas. The final measures of the movement recede to simple orchestral descending contrapuntal scales.

e. Confutatis[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Confutatis («From the accursed») begins with a rhythmic and dynamic sequence of strong contrasts and surprising harmonic turns. Accompanied by the basso continuo, the tenors and basses burst into a forte vision of the infernal, on a dotted rhythm. The accompaniment then ceases alongside the tenors and basses, and the sopranos and altos enter softly and sotto voce, singing Voca me cum benedictis («Call upon me with the blessed») with an arpeggiated accompaniment in strings.

Finally, in the following stanza (Oro supplex et acclinis), there is a striking modulation from A minor to A♭ minor.

This spectacular descent from the opening key is repeated, now modulating to the key of F major. A final dominant seventh chord leads to the Lacrymosa.

f. Lacrymosa[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The chords begin piano on a rocking rhythm in 12

8, intercut with quarter rests, which will be reprised by the choir after two measures, on Lacrimosa dies illa («This tearful day»). Then, after two measures, the sopranos begin a diatonic progression, in disjointed eighth-notes on the text resurget («will be reborn»), then legato and chromatic on a powerful crescendo. The choir is forte by m. 8, at which point Mozart’s contribution to the movement is interrupted by his death.

Süssmayr brings the choir to a reference of the Introit and ends on an Amen cadence. Discovery of a fragmentary Amen fugue in Mozart’s hand has led to speculation that it may have been intended for the Requiem. Indeed, many modern completions (such as Levin’s) complete Mozart’s fragment. Some sections of this movement are quoted in the Requiem mass of Franz von Suppé, who was a great admirer of Mozart. Ray Robinson, the music scholar and president (from 1969 to 1987) of the Westminster Choir College, suggests that Süssmayr used materials from Credo of one of Mozart’s earlier masses, Mass in C major, K. 220 «Sparrow» in completing this movement.[4]

IV. Offertorium[edit]

a. Domine Jesu[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The first movement of the Offertorium, the Domine Jesu, begins on a piano theme consisting of an ascending progression on a G minor triad. This theme will later be varied in various keys, before returning to G minor when the four soloists enter a canon on Sed signifer sanctus Michael, switching between minor (in ascent) and major (in descent). Between these thematic passages are forte phrases where the choir enters, often in unison and dotted rhythm, such as on Rex gloriae («King of glory») or de ore leonis («[Deliver them] from the mouth of the lion»). Two choral fugues follow, on ne absorbeat eas tartarus, ne cadant in obscurum («may Tartarus not absorb them, nor may they fall into darkness») and Quam olim Abrahae promisisti et semini eius («What once to Abraham you promised and to his seed»). The movement concludes homophonically in G major.

b. Hostias[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Hostias opens in E♭ major in 3

4, with fluid vocals. After 20 measures, the movement switches to an alternation of forte and piano exclamations of the choir, while progressing from B♭ major towards B♭ minor, then F major, D♭ major, A♭ major, F minor, C minor and E♭ major. An overtaking chromatic melody on Fac eas, Domine, de morte transire ad vitam («Make them, O Lord, cross over from death to life») finally carries the movement into the dominant of G minor, followed by a reprise of the Quam olim Abrahae promisisti et semini eius fugue.

The words «Quam olim da capo» are likely to have been the last Mozart wrote; this portion of the manuscript has been missing since it was stolen at 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels by a person whose identity remains unknown.

Süssmayr’s additions[edit]

V. Sanctus[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Sanctus is the first movement written entirely by Süssmayr, and the only movement of the Requiem to have a key signature with sharps: D major, generally used for the entry of trumpets in the Baroque era. After a succinct glorification of the Lord follows a short fugue in 3

4 on Hosanna in excelsis («Glory [to God] in the highest»), noted for its syncopated rhythm, and for its motivic similarity to the Quam olim Abrahae fugue.

VI. Benedictus[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

The Benedictus, a quartet, adopts the key of the submediant, B♭ major (which can also be considered the relative of the subdominant of the key of D minor). The Sanctus’s ending on a D major cadence necessitates a mediant jump to this new key.

The Benedictus is constructed on three types of phrases: the (A) theme, which is first presented by the orchestra and reprised from m. 4 by the alto and from m. 6 by the soprano. The word benedictus is held, which stands in opposition with the (B) phrase, which is first seen at m. 10, also on the word benedictus but with a quick and chopped-up rhythm. The phrase develops and rebounds at m. 15 with a broken cadence. The third phrase, (C), is a solemn ringing where the winds respond to the chords with a staggering harmony, as shown in a Mozartian cadence at mm. 21 and 22, where the counterpoint of the basset horns mixes with the line of the cello. The rest of the movement consists of variations on this writing. At m. 23, phrase (A) is reprised on a F pedal and introduces a recapitulation of the primary theme from the bass and tenor from mm. 28 and 30, respectively. Phrase (B) follows at m. 33, although without the broken cadence, then repeats at m. 38 with the broken cadence once more. This carries the movement to a new Mozartian cadence in mm. 47 to 49 and concludes on phrase (C), which reintroduces the Hosanna fugue from the Sanctus movement, in the new key of the Benedictus.

VII. Agnus Dei[edit]

1956 Salzburg Festival performance (see above)

Homophony dominates the Agnus Dei. The text is repeated three times, always with chromatic melodies and harmonic reversals, going from D minor to F major, C major, and finally B♭ major. According to the musicologist Simon P. Keefe, Süssmayr likely referenced one of Mozart’s earlier masses, Mass in C major, K. 220 «Sparrow» in completing this movement.[5]

VIII. Communio[edit]

Süssmayr here reuses Mozart’s first two movements, almost exactly note for note, with wording corresponding to this part of the liturgy.

History[edit]

Composition[edit]

The beginning of the Dies irae in the autograph manuscript, with Eybler’s orchestration. In the upper right, Nissen has left a note: «All which is not enclosed by the quill is of Mozart’s hand up to page 32.» The first violin, choir and figured bass are entirely Mozart’s.

At the time of Mozart’s death on 5 December 1791, only the first movement, Introitus (Requiem aeternam) was completed in all of the orchestral and vocal parts. The Kyrie, Sequence and Offertorium were completed in skeleton, with the exception of the Lacrymosa, which breaks off after the first eight bars. The vocal parts and continuo were fully notated. Occasionally, some of the prominent orchestral parts were briefly indicated, such as the first violin part of the Rex tremendae and Confutatis, the musical bridges in the Recordare, and the trombone solos of the Tuba Mirum.

What remained to be completed for these sections were mostly accompanimental figures, inner harmonies, and orchestral doublings to the vocal parts.

Completion by Mozart’s contemporaries[edit]

The eccentric count Franz von Walsegg commissioned the Requiem from Mozart anonymously through intermediaries. The count, an amateur chamber musician who routinely commissioned works by composers and passed them off as his own,[6][7] wanted a Requiem Mass he could claim he composed to memorialize the recent passing of his wife. Mozart received only half of the payment in advance, so upon his death his widow Constanze was keen to have the work completed secretly by someone else, submit it to the count as having been completed by Mozart and collect the final payment.[8] Joseph von Eybler was one of the first composers to be asked to complete the score, and had worked on the movements from the Dies irae up until the Lacrymosa. In addition, a striking similarity between the openings of the Domine Jesu Christe movements in the requiems of the two composers suggests that Eybler at least looked at later sections.[further explanation needed] After this work, he felt unable to complete the remainder and gave the manuscript back to Constanze Mozart.

The task was then given to another composer, Franz Xaver Süssmayr. Süssmayr borrowed some of Eybler’s work in making his completion, and added his own orchestration to the movements from the Kyrie onward, completed the Lacrymosa, and added several new movements which a Requiem would normally comprise: Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei. He then added a final section, Lux aeterna by adapting the opening two movements which Mozart had written to the different words which finish the Requiem mass, which according to both Süssmayr and Mozart’s wife was done according to Mozart’s directions. Some people[who?] consider it unlikely, however, that Mozart would have repeated the opening two sections if he had survived to finish the work.

Other composers may have helped Süssmayr. The Agnus Dei is suspected by some scholars[9] to have been based on instruction or sketches from Mozart because of its similarity to a section from the Gloria of a previous mass (Sparrow Mass, K. 220) by Mozart,[10] as was first pointed out by Richard Maunder. Others have pointed out that at the beginning of the Agnus Dei, the choral bass quotes the main theme from the Introitus.[11] Many of the arguments dealing with this matter, though, center on the perception that if part of the work is high quality, it must have been written by Mozart (or from sketches), and if part of the work contains errors and faults, it must have been all Süssmayr’s doing.[12]

Another controversy is the suggestion (originating from a letter written by Constanze) that Mozart left explicit instructions for the completion of the Requiem on «a few scraps of paper with music on them… found on Mozart’s desk after his death.»[13] The extent to which Süssmayr’s work may have been influenced by these «scraps» if they existed at all remains a subject of speculation amongst musicologists to this day.

The completed score, initially by Mozart but largely finished by Süssmayr, was then dispatched to Count Walsegg complete with a counterfeited signature of Mozart and dated 1792. The various complete and incomplete manuscripts eventually turned up in the 19th century, but many of the figures involved left ambiguous statements on record as to how they were involved in the affair. Despite the controversy over how much of the music is actually Mozart’s, the commonly performed Süssmayr version has become widely accepted by the public. This acceptance is quite strong, even when alternative completions provide logical and compelling solutions for the work.

Promotion by Constanze Mozart[edit]