Первой опубликованной работой Канта был трактат “Мысли к истинной оценке живых сил”. Эта работа, посвященная одной физической проблеме, была представлена на цензуру декану философского факультета еще весной 1746 г., но из-за ряда причин опубликована только в 1749 г. на деньги его дяди сапожника Рихтера.

Следующая важная работа Канта – “Всеобщая естественная история и теория неба”, которую он публикует в 1755 г. вскоре после возвращения в университет. В этой работе Кантом была выдвинута знаменитая гипотеза, объясняющая образование Солнечной системы из первоначальной газо-пылевой туманности при помощи только сил притяжения и отталкивания. В том же 1755 г. Кант представляет философскому факультету латинскую диссертацию “Новое освещение первых принципов метафизического познания” – первую собственно философскую работу.

Далее Кант публикует ряд естественнонаучных сочинений, а в 1762 году появляется его большая работа “О единственно возможном доказательстве бытия Бога” а также небольшой трактат по логике «Ложное мудрствование в четырех фигурах силлогизма».

В 1763 г. он в качестве работы, представленной на соискание премии Берлинской академии наук, публикует “Исследование степени ясности принципов естественной теологии и морали”. Правда, работа не получила первой премии, зато была опубликована в числе лучших.

В конце 1763 г. или в начале 1764 г. выходит чисто философская работа, к тому же написанная в блестящем, “легком” стиле “Наблюдения над чувством прекрасного и возвышенного”. В 1766 г. появляется работа Канта “Грезы духовидца, поясненные грезами метафизики”, содержащая критику теософических взглядов шведского ученого и духовидца Эммануэля Сведенборга (1688-1772).

В 1770 г. в связи с вступлением в должность ординарного профессора логики и метафизики Кант готовит еще одну латинскую диссертацию “О форме и принципах чувственного и умопостигаемого мира”. Эта работа имела важное значение в философской эволюции Канта, поскольку в ней впервые могут быть ясно прослежены идеи философии, составившей эпоху в развитии человеческой мысли – “критической философии” Канта.

С 1770 г. по 1781 г. наступает практически полное молчание. За это время было опубликовано всего лишь три небольших работы. Главной задачей Канта становится выработка собственной философской концепции, которая и была сформулирована в знаменитой работе Канта, совершившей коперниканский переворот в философии, – “Критике чистого разума”(1781). Наступает эпоха критической философии. Вскоре Канту понадобилось разъяснить более популярно идеи своей новой философии, и он издает “Пролегомены ко всякой будущей метафизике, которая может рассматриваться как наука”.

В середине восьмидесятых годов были также опубликованы небольшие, но важные работы, знаменующие переход Канта к проблемам, связанным с рассмотрением общественных процессов “Идея всеобщей истории с всемирно-гражданской точки зрения” (1784) и “Ответ на вопрос: Что такое просвещение?” (1784). За ними следует первая работа, посвященная собственно морали – “Основы метафизики нравов” (1785), подготовившая почву для второй критики Канта – “Критики практического разума” (1788), в которой в полном объеме рассмотрены проблемы практической философии, включающей в себя философское обоснование морали.

Вскоре следует третья критика – “Критика способности суждения” (1790), в которой Кант рассматривает учение о целесообразности в природе и человеке и тем самым закладывает основы критической эстетики. В 1793 г. выходит книга “Религия в пределах только разума”, где Кант попытался дать теорию религии, основанную на его критической философии. В 1795 г. появляется небольшая, но важная работа “К вечному миру”, в которой Кант попытался сформулировать философские принципы, принятие которых могло бы способствовать установлению на земле вечного мира.

В 1797 г. появляется “Метафизика нравов”, состоящих из двух частей: “Метафизических начал учения о праве” и “Метафизических начал учения о добродетели”, в этой книге Кант не только развивает свое учение о морали, но и строит философскую теорию права.

В 1798 г. появляется большая последняя работа Канта “Антропология с прагматической точки зрения”. В 1800 г., возможно, с участием Канта появляется изданная Йеше “Логика. Пособие к лекциям”. В 1802-1803 гг. появляется “Физическая география”, изданная Ринком, а в 1803 г. “О педагогике” под редакцией того же Ринка.

На этом заканчивается прижизненная история издания сочинений Канта.

Кант считал, что философия обязана ответить человечеству, по крайней мере, на четыре вопроса:

Что я могу знать?

Что я должен делать?

На что я могу надеяться?

Что такое человек?

Три вопроса сформулированы в “Критике чистого разума” (3, 661), а в лекциях по логике добавлен четвертый. Они последовательно охватывают область возможного для нас знания и способов познания того, что находится за пределами знания, область нашего практического действия и той части этих действий, которые относятся к должному, а также область будущего, которое может проистечь из наших должных (или не должных) действий, а, следовательно, определяет то, на что мы можем, а на что не можем надеяться.

В дальнейшем мы последовательно разберем кантовские ответы на эти вопросы.

Первой опубликованной работой Канта был трактат «Мысли к истинной оценке живых сил». Эта работа, посвященная одной физической проблеме, была представлена на цензуру декану философского факультета еще весной 1746 г., но из-за ряда причин опубликована только в 1749 г. на деньги его дяди сапожника Рихтера.

Следующая важная работа Канта — «Всеобщая естественная история и теория неба», которую он публикует в 1755 г. вскоре после возвращения в университет. В этой работе Кантом была выдвинута знаменитая гипотеза, объясняющая образование Солнечной системы из первоначальной газо-пылевой туманности при помощи только сил притяжения и отталкивания. В том же 1755 г. Кант представляет философскому факультету латинскую диссертацию «Новое освещение первых принципов метафизического познания» — первую собственно философскую работу.

Далее Кант публикует ряд естественнонаучных сочинений, а в 1762 году появляется его большая работа «О единственно возможном доказательстве бытия Бога» а также небольшой трактат по логике «Ложное мудрствование в четырех фигурах силлогизма».

В 1763 г. он в качестве работы, представленной на соискание премии Берлинской академии наук, публикует «Исследование степени ясности принципов естественной теологии и морали». Правда, работа не получила первой премии, зато была опубликована в числе лучших.

В конце 1763 г. или в начале 1764 г. выходит чисто философская работа, к тому же написанная в блестящем, «легком» стиле «Наблюдения над чувством прекрасного и возвышенного». В 1766 г. появляется работа Канта «Грезы духовидца, поясненные грезами метафизики», содержащая критику теософических взглядов шведского ученого и духовидца Эммануэля Сведенборга (1688-1772).

В 1770 г. в связи с вступлением в должность ординарного профессора логики и метафизики Кант готовит еще одну латинскую диссертацию «О форме и принципах чувственного и умопостигаемого мира». Эта работа имела важное значение в философской эволюции Канта, поскольку в ней впервые могут быть ясно прослежены идеи философии, составившей эпоху в развитии человеческой мысли — «критической философии» Канта.

С 1770 г. по 1781 г. наступает практически полное молчание. За это время было опубликовано всего лишь три небольших работы. Главной задачей Канта становится выработка собственной философской концепции, которая и была сформулирована в знаменитой работе Канта, совершившей коперниканский переворот в философии, — «Критике чистого разума» (1781). Наступает эпоха критической философии. Вскоре Канту понадобилось разъяснить более популярно идеи своей новой философии, и он издает «Пролегомены ко всякой будущей метафизике, которая может рассматриваться как наука».

В середине восьмидесятых годов были также опубликованы небольшие, но важные работы, знаменующие переход Канта к проблемам, связанным с рассмотрением общественных процессов «Идея всеобщей истории с всемирно-гражданской точки зрения» (1784) и «Ответ на вопрос: Что такое просвещение?» (1784). За ними следует первая работа, посвященная собственно морали — «Основы метафизики нравов» (1785), подготовившая почву для второй критики Канта — «Критики практического разума» (1788), в которой в полном объеме рассмотрены проблемы практической философии, включающей в себя философское обоснование морали.

Вскоре следует третья критика — «Критика способности суждения» (1790), в которой Кант рассматривает учение о целесообразности в природе и человеке и тем самым закладывает основы критической эстетики. В 1793 г. выходит книга «Религия в пределах только разума», где Кант попытался дать теорию религии, основанную на его критической философии. В 1795 г. появляется небольшая, но важная работа «К вечному миру», в которой Кант попытался сформулировать философские принципы, принятие которых могло бы способствовать установлению на земле вечного мира.

В 1797 г. появляется «Метафизика нравов», состоящих из двух частей: «Метафизических начал учения о праве» и «Метафизических начал учения о добродетели», в этой книге Кант не только развивает свое учение о морали, но и строит философскую теорию права.

В 1798 г. появляется большая последняя работа Канта «Антропология с прагматической точки зрения». В 1800 г., возможно, с участием Канта появляется изданная Йеше «Логика. Пособие к лекциям». В 1802-1803 гг. появляется «Физическая география», изданная Ринком, а в 1803 г. «О педагогике» под редакцией того же Ринка.

На этом заканчивается прижизненная история издания сочинений Канта.

|

Immanuel Kant |

|

|---|---|

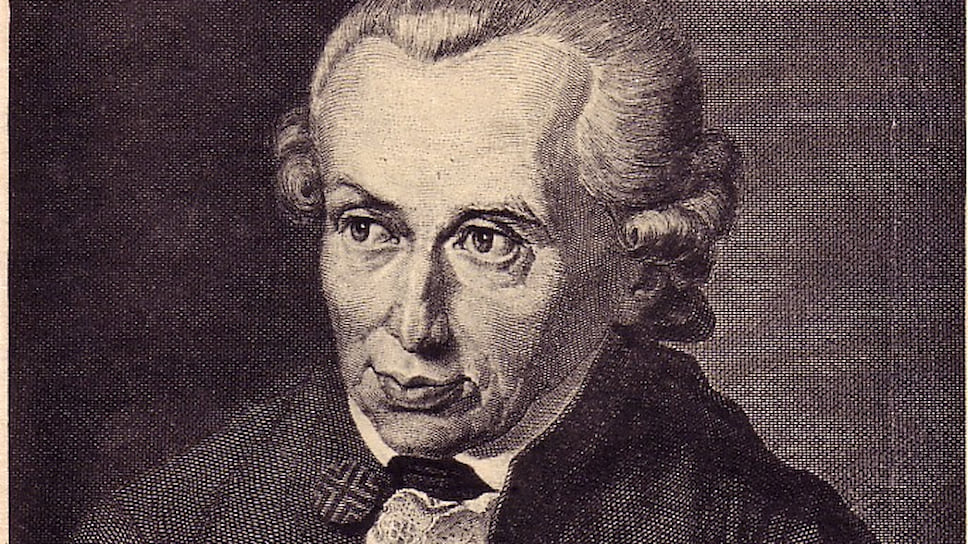

Portrait by Johann Gottlieb Becker, 1768 |

|

| Born | 22 April 1724

Königsberg, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died | 12 February 1804 (aged 79)

Königsberg, East Prussia, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Education | Collegium Fridericianum University of Königsberg (B.A.; M.A., April 1755; PhD, September 1755; PhD,[1] August 1770) |

| Era | Age of Enlightenment |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

Other schools

|

| Institutions | University of Königsberg |

| Theses |

|

| Academic advisors | Martin Knutzen, Johann Gottfried Teske (M.A. advisor), Konrad Gottlieb Marquardt[11] |

| Notable students | Jakob Sigismund Beck, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Johann Gottfried Herder, Karl Leonhard Reinhold (epistolary correspondent)[19] |

|

Main interests |

Aesthetics, cosmogony, epistemology, ethics, metaphysics, systematic philosophy |

|

Notable ideas |

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

Immanuel Kant (,[20][21] ,[22][23] German: [ɪˈmaːnu̯eːl ˈkant];[24][25] 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers.[26][27] Born in Königsberg, Kant’s comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics have made him one of the most influential figures in modern Western philosophy.[26][28]

In his doctrine of transcendental idealism, Kant argued that space and time are mere «forms of intuition» which structure all experience, and therefore that, while «things-in-themselves» exist and contribute to experience, they are nonetheless distinct from the objects of experience. From this it follows that the objects of experience are mere «appearances», and that the nature of things as they are in themselves is unknowable to us.[29][30] In an attempt to counter the skepticism he found in the writings of philosopher David Hume,[31] he wrote the Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787),[32] one of his most well-known works. In it, he developed his theory of experience to answer the question of whether synthetic a priori knowledge is possible, which would in turn make it possible to determine the limits of metaphysical inquiry. Kant drew a parallel to the Copernican revolution in his proposal to think of the objects of the senses as conforming to our spatial and temporal forms of intuition, so that we have a priori cognition of those objects.[b]

Kant believed that reason is also the source of morality, and that aesthetics arise from a faculty of disinterested judgment. Kant’s views continue to have a major influence on contemporary philosophy, especially the fields of epistemology, ethics, political theory, and post-modern aesthetics.[28] He attempted to explain the relationship between reason and human experience and to move beyond what he believed to be the failures of traditional philosophy and metaphysics. He wanted to put an end to what he saw as an era of futile and speculative theories of human experience, while resisting the skepticism of thinkers such as Hume. He regarded himself as showing the way past the impasse between rationalists and empiricists,[34] and is widely held to have synthesized both traditions in his thought.[35]

Kant was an exponent of the idea that perpetual peace could be secured through universal democracy and international cooperation, and that perhaps this could be the culminating stage of world history.[36] The nature of Kant’s religious views continues to be the subject of scholarly dispute, with viewpoints ranging from the impression that he shifted from an early defense of an ontological argument for the existence of God to a principled agnosticism, to more critical treatments epitomized by Schopenhauer, who criticized the imperative form of Kantian ethics as «theological morals» and the «Mosaic Decalogue in disguise»,[37] and Nietzsche, who claimed that Kant had «theologian blood»[38] and was merely a sophisticated apologist for traditional Christian faith.[c] Beyond his religious views, Kant has also been criticized for the racism presented in some of his lesser-known papers, such as «On the Use of Teleological Principles in Philosophy» and «On the Different Races of Man».[40][41][42][43] Although he was a proponent of scientific racism for much of his career, Kant’s views on race changed significantly in the last decade of his life, and he ultimately rejected racial hierarchies and European colonialism in Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch (1795).[44]

Kant published other important works on ethics, religion, law, aesthetics, astronomy, and history during his lifetime. These include the Universal Natural History (1755), the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), the Critique of Judgment (1790), Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason (1793), and the Metaphysics of Morals (1797).[27]

Biography[edit]

Kant was born on 22 April 1724 into a Prussian German family of Lutheran Protestant faith in Königsberg, East Prussia (since 1946 the city of Kaliningrad, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia). His mother, Anna Regina Reuter[45] (1697–1737), was born in Königsberg to a father from Nuremberg.[citation needed] Her surname is sometimes erroneously given as Porter. Kant’s father, Johann Georg Kant (1682–1746), was a German harness maker from Memel, at the time Prussia’s most northeastern city (now Klaipėda, Lithuania). Kant believed that his paternal grandfather Hans Kant was of Scottish origin.[46] While scholars of Kant’s life long accepted the claim, modern scholarship challenges it. It is possible that Kants got their name from the village of Kantvainiai (German: Kantwaggen – today part of Priekulė) and were of Kursenieki origin.[47][48] Kant was the fourth of nine children (six of whom reached adulthood).[49]

Baptized Emanuel, he later changed the spelling of his name to Immanuel[50] after learning Hebrew. He was brought up in a Pietist household that stressed religious devotion, humility, and a literal interpretation of the Bible.[51][citation needed] His education was strict, punitive and disciplinary, and focused on Latin and religious instruction over mathematics and science.[52] In his Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, he reveals a belief in immortality as the necessary condition of humanity’s approach to the highest morality possible.[53][54] However, as Kant was skeptical about some of the arguments used prior to him in defence of theism and maintained that human understanding is limited and can never attain knowledge about God or the soul, various commentators have labelled him a philosophical agnostic,[55][56][57][58][59][60] even though it has also been suggested that Kant intends other people to think of him as a «pure rationalist», who is defined by Kant himself as someone who recognizes revelation but asserts that to know and accept it as real is not a necessary requisite to religion.[61]

Kant apparently lived a very strict and disciplined life; it was said that neighbors would set their clocks by his daily walks. He never married,[62] but seems to have had a rewarding social life—he was a popular teacher, as well as a modestly successful author even before starting on his major philosophical works. He had a circle of friends with whom he frequently met—among them Joseph Green, an English merchant in Königsberg, whom reportedly he first spoke to in an argument in 1763 or before. According to the story, Kant was strolling in the Dänhofscher Garten when he saw one of his acquaintances speaking to a group of men he did not know. He joined the conversation, which soon turned to unusual current events in the world. The topic of the disagreement between the British and the Americans came up. Kant took the side of the Americans, and this upset Green. He challenged Kant to a fight. Kant reportedly explained that patriotism did not get in the way of his view, and that any cosmopolitan citizen could take his position if he held Kant’s political principles, which Kant explained to Green. Green was so stunned by Kant’s ability to express his views, that Green offered to become friends with Kant, and invited him to his apartment that evening.[63]

Between 1750 and 1754 Kant worked as a tutor (Hauslehrer) in the Lithuanian village of Jučiai (German: Judtschen;[64] approximately 20 km east of Königsberg, and in Groß-Arnsdorf[65] (now Jarnołtowo near Morąg (German: Mohrungen), Poland), approximately 145 km east of Königsberg.

Many myths grew up about Kant’s personal mannerisms; these are listed, explained, and refuted in Goldthwait’s introduction to his translation of Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime.[66]

Young scholar[edit]

Kant showed a great aptitude for study at an early age. He first attended the Collegium Fridericianum from which he graduated at the end of the summer of 1740. In 1740, aged 16, he enrolled at the University of Königsberg, where he spent his whole career.[67] He studied the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz and Christian Wolff under Martin Knutzen (Associate Professor of Logic and Metaphysics from 1734 until his death in 1751), a rationalist who was also familiar with developments in British philosophy and science and introduced Kant to the new mathematical physics of Isaac Newton. Knutzen dissuaded Kant from the theory of pre-established harmony, which he regarded as «the pillow for the lazy mind».[68] He also dissuaded Kant from idealism, the idea that reality is purely mental, which most philosophers in the 18th century regarded in a negative light. The theory of transcendental idealism that Kant later included in the Critique of Pure Reason was developed partially in opposition to traditional idealism.

His father’s stroke and subsequent death in 1746 interrupted his studies. Kant left Königsberg shortly after August 1748[69]—he would return there in August 1754.[70] He became a private tutor in the towns surrounding Königsberg, but continued his scholarly research. In 1749, he published his first philosophical work, Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces (written in 1745–47).[71]

Early work[edit]

Kant is best known for his work in the philosophy of ethics and metaphysics,[26] but he made significant contributions to other disciplines. In 1754, while contemplating on a prize question by the Berlin Academy about the problem of Earth’s rotation, he argued that the Moon’s gravity would slow down Earth’s spin and he also put forth the argument that gravity would eventually cause the Moon’s tidal locking to coincide with the Earth’s rotation.[d][73] The next year, he expanded this reasoning to the formation and evolution of the Solar System in his Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens.[73] In 1755, Kant received a license to lecture in the University of Königsberg and began lecturing on a variety of topics including mathematics, physics, logic and metaphysics. In his 1756 essay on the theory of winds, Kant laid out an original insight into the Coriolis force.

In 1756 Kant also published three papers on the 1755 Lisbon earthquake.[74] Kant’s theory, which involved shifts in huge caverns filled with hot gases, though inaccurate, was one of the first systematic attempts to explain earthquakes in natural rather than supernatural terms. According to Walter Benjamin, Kant’s slim early book on the earthquake «probably represents the beginnings of scientific geography in Germany. And certainly the beginnings of seismology».

In 1757, Kant began lecturing on geography making him one of the first lecturers to explicitly teach geography as its own subject.[75][76] Geography was one of Kant’s most popular lecturing topics and in 1802 a compilation by Friedrich Theodor Rink of Kant’s lecturing notes, Physical Geography, was released. After Kant became a professor in 1770, he expanded the topics of his lectures to include lectures on natural law, ethics, and anthropology, along with other topics.[75]

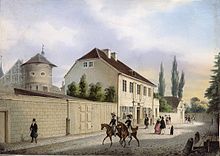

Kant’s house in Königsberg

In the Universal Natural History, Kant laid out the Nebular hypothesis, in which he deduced that the Solar System had formed from a large cloud of gas, a nebula. Kant also correctly deduced that the Milky Way was a large disk of stars, which he theorized formed from a much larger spinning gas cloud. He further suggested that other distant «nebulae» might be other galaxies. These postulations opened new horizons for astronomy, for the first time extending it beyond the Solar System to galactic and intergalactic realms.[77] According to Thomas Huxley (1867), Kant also made contributions to geology in his Universal Natural History.[78][79]

From then on, Kant turned increasingly to philosophical issues, although he continued to write on the sciences throughout his life. In the early 1760s, Kant produced a series of important works in philosophy. The False Subtlety of the Four Syllogistic Figures, a work in logic, was published in 1762. Two more works appeared the following year: Attempt to Introduce the Concept of Negative Magnitudes into Philosophy and The Only Possible Argument in Support of a Demonstration of the Existence of God. By 1764, Kant had become a notable popular author, and wrote Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime;[80] he was second to Moses Mendelssohn in a Berlin Academy prize competition with his Inquiry Concerning the Distinctness of the Principles of Natural Theology and Morality (often referred to as «The Prize Essay»). In 1766 Kant wrote Dreams of a Spirit-Seer which dealt with the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. The exact influence of Swedenborg on Kant, as well as the extent of Kant’s belief in mysticism according to Dreams of a Spirit-Seer, remain controversial. On the face of it, Dreams of a Spirit-Seer argued against the ideas of Swedenborg. Kant poked holes in the logic of Swedenborg’s view of the nature of spirits,[81] but also communicated his curiosity about Swedenborg’s mysticism.[82] On 31 March 1770, aged 45, Kant was finally appointed Full Professor of Logic and Metaphysics (Professor Ordinarius der Logic und Metaphysic) at the University of Königsberg. In defense of this appointment, Kant wrote his inaugural dissertation (Inaugural-Dissertation) De Mundi Sensibilis atque Intelligibilis Forma et Principiis (On the Form and Principles of the Sensible and the Intelligible World).[1] This work saw the emergence of several central themes of his mature work, including the distinction between the faculties of intellectual thought and sensible receptivity. To miss this distinction would mean to commit the error of subreption, and, as he says in the last chapter of the dissertation, only in avoiding this error does metaphysics flourish.

The issue that vexed Kant was central to what 20th-century scholars called «the philosophy of mind». The flowering of the natural sciences had led to an understanding of how data reaches the brain. Sunlight falling on an object is reflected from its surface in a way that maps the surface features (color, texture, etc.). The reflected light reaches the human eye, passes through the cornea, is focused by the lens onto the retina where it forms an image similar to that formed by light passing through a pinhole into a camera obscura. The retinal cells send impulses through the optic nerve and then they form a mapping in the brain of the visual features of the object. The interior mapping is not the exterior object, and our belief that there is a meaningful relationship between the object and the mapping in the brain depends on a chain of reasoning that is not fully grounded. But the uncertainty aroused by these considerations, by optical illusions, misperceptions, delusions, etc., is not the end of the problem.

Kant saw that the mind could not function as an empty container that simply receives data from outside. Something must be giving order to the incoming data. Images of external objects must be kept in the same sequence in which they were received. This ordering occurs through the mind’s intuition of time. The same considerations apply to the mind’s function of constituting space for ordering mappings of visual and tactile signals arriving via the already described chains of physical causation.

It is often claimed that Kant was a late developer, that he only became an important philosopher in his mid-50s after rejecting his earlier views. While it is true that Kant wrote his greatest works relatively late in life, there is a tendency to underestimate the value of his earlier works. Recent Kant scholarship has devoted more attention to these «pre-critical» writings and has recognized a degree of continuity with his mature work.[83]

Critique of Pure Reason[edit]

At age 46, Kant was an established scholar and an increasingly influential philosopher, and much was expected of him. In correspondence with his ex-student and friend Markus Herz, Kant admitted that, in the inaugural dissertation, he had failed to account for the relation between our sensible and intellectual faculties.[84] He needed to explain how we combine what is known as sensory knowledge with the other type of knowledge—i.e. reasoned knowledge—these two being related but having very different processes.

Kant also credited David Hume with awakening him from a «dogmatic slumber» in which he had unquestioningly accepted the tenets of both religion and natural philosophy.[85][86] Hume in his 1739 Treatise on Human Nature had argued that we only know the mind through a subjective—essentially illusory—series of perceptions.[85] Ideas such as causality, morality, and objects are not evident in experience, so their reality may be questioned. Kant felt that reason could remove this skepticism, and he set himself to solving these problems. Although fond of company and conversation with others, Kant isolated himself, and resisted friends’ attempts to bring him out of his isolation.[e] When Kant emerged from his silence in 1781, the result was the Critique of Pure Reason. Kant countered Hume’s empiricism by claiming that some knowledge exists inherently in the mind, independent of experience.[85] He drew a parallel to the Copernican revolution in his proposal that worldly objects can be intuited a priori (‘beforehand’), and that intuition is consequently distinct from objective reality.[b] He acquiesced to Hume somewhat by defining causality as a «regular, constant sequence of events in time, and nothing more.»[88]

Although now uniformly recognized as one of the greatest works in the history of philosophy, this Critique disappointed Kant’s readers upon its initial publication.[89] The book was long, over 800 pages in the original German edition, and written in a convoluted style. It received few reviews, and these granted it no significance.[citation needed] Kant’s former student, Johann Gottfried Herder criticized it for placing reason as an entity worthy of criticism instead of considering the process of reasoning within the context of language and one’s entire personality.[90] Similar to Christian Garve and Johann Georg Heinrich Feder, he rejected Kant’s position that space and time possessed a form that could be analyzed. Additionally, Garve and Feder also faulted Kant’s Critique for not explaining differences in perception of sensations.[91] Its density made it, as Herder said in a letter to Johann Georg Hamann, a «tough nut to crack», obscured by «all this heavy gossamer».[92] Its reception stood in stark contrast to the praise Kant had received for earlier works, such as his Prize Essay and shorter works that preceded the first Critique. These well-received and readable tracts include one on the earthquake in Lisbon that was so popular that it was sold by the page.[93] Prior to the change in course documented in the first Critique, his books had sold well.[80] Kant was disappointed with the first Critique’s reception. Recognizing the need to clarify the original treatise, Kant wrote the Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics in 1783 as a summary of its main views. Shortly thereafter, Kant’s friend Johann Friedrich Schultz (1739–1805) (professor of mathematics) published Erläuterungen über des Herrn Professor Kant Critik der reinen Vernunft (Königsberg, 1784), which was a brief but very accurate commentary on Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason.

Engraving of Immanuel Kant

Kant’s reputation gradually rose through the latter portion of the 1780s, sparked by a series of important works: the 1784 essay, «Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?»; 1785’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (his first work on moral philosophy); and, from 1786, Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. But Kant’s fame ultimately arrived from an unexpected source. In 1786, Karl Leonhard Reinhold published a series of public letters on Kantian philosophy.[94] In these letters, Reinhold framed Kant’s philosophy as a response to the central intellectual controversy of the era: the pantheism controversy. Friedrich Jacobi had accused the recently deceased Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (a distinguished dramatist and philosophical essayist) of Spinozism. Such a charge, tantamount to atheism, was vigorously denied by Lessing’s friend Moses Mendelssohn, leading to a bitter public dispute among partisans. The controversy gradually escalated into a debate about the values of the Enlightenment and the value of reason.

Reinhold maintained in his letters that Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason could settle this dispute by defending the authority and bounds of reason. Reinhold’s letters were widely read and made Kant the most famous philosopher of his era.

Later work[edit]

Kant published a second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason in 1787, heavily revising the first parts of the book. Most of his subsequent work focused on other areas of philosophy. He continued to develop his moral philosophy, notably in 1788’s Critique of Practical Reason (known as the second Critique) and 1797’s Metaphysics of Morals. The 1790 Critique of Judgment (the third Critique) applied the Kantian system to aesthetics and teleology.

In 1792, Kant’s attempt to publish the Second of the four Pieces of Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason,[95] in the journal Berlinische Monatsschrift, met with opposition from the King’s censorship commission, which had been established that same year in the context of the French Revolution.[96] Kant then arranged to have all four pieces published as a book, routing it through the philosophy department at the University of Jena to avoid the need for theological censorship.[96] This insubordination earned him a now famous reprimand from the King.[96] When he nevertheless published a second edition in 1794, the censor was so irate that he arranged for a royal order that required Kant never to publish or even speak publicly about religion.[96] Kant then published his response to the King’s reprimand and explained himself, in the preface of The Conflict of the Faculties.[96]

He also wrote a number of semi-popular essays on history, religion, politics and other topics. These works were well received by Kant’s contemporaries and confirmed his preeminent status in 18th-century philosophy. There were several journals devoted solely to defending and criticizing Kantian philosophy. Despite his success, philosophical trends were moving in another direction. Many of Kant’s most important disciples and followers (including Reinhold, Beck and Fichte) transformed the Kantian position into increasingly radical forms of idealism. The progressive stages of revision of Kant’s teachings marked the emergence of German idealism. Kant opposed these developments and publicly denounced Fichte in an open letter in 1799.[97] It was one of his final acts expounding a stance on philosophical questions. In 1800, a student of Kant named Gottlob Benjamin Jäsche (1762–1842) published a manual of logic for teachers called Logik, which he had prepared at Kant’s request. Jäsche prepared the Logik using a copy of a textbook in logic by Georg Friedrich Meier entitled Auszug aus der Vernunftlehre, in which Kant had written copious notes and annotations. The Logik has been considered of fundamental importance to Kant’s philosophy, and the understanding of it. The great 19th-century logician Charles Sanders Peirce remarked, in an incomplete review of Thomas Kingsmill Abbott’s English translation of the introduction to Logik, that «Kant’s whole philosophy turns upon his logic.»[98] Also, Robert Schirokauer Hartman and Wolfgang Schwarz, wrote in the translators’ introduction to their English translation of the Logik, «Its importance lies not only in its significance for the Critique of Pure Reason, the second part of which is a restatement of fundamental tenets of the Logic, but in its position within the whole of Kant’s work.»[99]

Death and burial[edit]

Kant’s health, long poor, worsened and he died at Königsberg on 12 February 1804, uttering «Es ist gut» (It is good) before expiring.[100] His unfinished final work was published as Opus Postumum. Kant always cut a curious figure in his lifetime for his modest, rigorously scheduled habits, which have been referred to as clocklike. However, Heinrich Heine noted the magnitude of «his destructive, world-crushing thoughts» and considered him a sort of philosophical «executioner», comparing him to Robespierre with the observation that both men «represented in the highest the type of provincial bourgeois. Nature had destined them to weigh coffee and sugar, but Fate determined that they should weigh other things and placed on the scales of the one a king, on the scales of the other a god.»[101]

When his body was transferred to a new burial spot, his skull was measured during the exhumation and found to be larger than the average German male’s with a «high and broad» forehead.[102] His forehead has been an object of interest ever since it became well-known through his portraits: «In Döbler’s portrait and in Kiefer’s faithful if expressionistic reproduction of it—as well as in many of the other late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century portraits of Kant—the forehead is remarkably large and decidedly retreating. Was Kant’s forehead shaped this way in these images because he was a philosopher, or, to follow the implications of Lavater’s system, was he a philosopher because of the intellectual acuity manifested by his forehead? Kant and Johann Kaspar Lavater were correspondents on theological matters, and Lavater refers to Kant in his work «Physiognomic Fragments, for the Education of Human Knowledge and Love of People» (Leipzig & Winterthur, 1775–1778).[103]

Kant’s mausoleum adjoins the northeast corner of Königsberg Cathedral in Kaliningrad, Russia. The mausoleum was constructed by the architect Friedrich Lahrs and was finished in 1924 in time for the bicentenary of Kant’s birth. Originally, Kant was buried inside the cathedral, but in 1880 his remains were moved to a neo-Gothic chapel adjoining the northeast corner of the cathedral. Over the years, the chapel became dilapidated and was demolished to make way for the mausoleum, which was built on the same location.

The tomb and its mausoleum are among the few artifacts of German times preserved by the Soviets after they captured the city.[104] Today, many newlyweds bring flowers to the mausoleum. Artifacts previously owned by Kant, known as Kantiana, were included in the Königsberg City Museum. However, the museum was destroyed during World War II. A replica of the statue of Kant that in German times stood in front of the main University of Königsberg building was donated by a German entity in the early 1990s and placed in the same grounds.

After the expulsion of Königsberg’s German population at the end of World War II, the University of Königsberg where Kant taught was replaced by the Russian-language Kaliningrad State University, which appropriated the campus and surviving buildings. In 2005, the university was renamed Immanuel Kant State University of Russia. The name change was announced at a ceremony attended by President Vladimir Putin of Russia and Chancellor Gerhard Schröder of Germany, and the university formed a Kant Society, dedicated to the study of Kantianism. The university was again renamed in the 2010s, to Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University.[105]

In 2018, his tomb and statue were vandalized with paint by unknown assailants, who also scattered leaflets glorifying Rus’ and denouncing Kant as a «traitor». The incident was apparently connected with a recent vote to rename Khrabrovo Airport, where Kant was in the lead for a while, prompting Russian nationalist resentment.[106]

Philosophy[edit]

In Kant’s essay «Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?», he defined the Enlightenment as an age shaped by the Latin motto Sapere aude («Dare to be wise»). Kant maintained that one ought to think autonomously, free of the dictates of external authority. His work reconciled many of the differences between the rationalist and empiricist traditions of the 18th century. He had a decisive impact on the Romantic and German Idealist philosophies of the 19th century. His work has also been a starting point for many 20th century philosophers.

Kant asserted that, because of the limitations of argumentation in the absence of irrefutable evidence, no one could really know whether there is a God and an afterlife or not. For the sake of morality and as a ground for reason, Kant asserted, people are justified in believing in God, even though they could never know God’s presence empirically.

Thus the entire armament of reason, in the undertaking that one can call pure philosophy, is in fact directed only at the three problems that have been mentioned [God, the soul, and freedom]. These themselves, however, have in turn their more remote aim, namely, what is to be done if the will is free, if there is a God, and if there is a future world. Now since these concern our conduct in relation to the highest end, the ultimate aim of nature which provides for us wisely in the disposition of reason is properly directed only to what is moral.[33]: 674–5 (A 800–1/B 828–9)

The sense of an enlightened approach and the critical method required that «If one cannot prove that a thing is, he may try to prove that it is not. If he fails to do either (as often occurs), he may still ask whether it is in his interest to accept one or the other of the alternatives hypothetically, from the theoretical or the practical point of view. Hence the question no longer is as to whether perpetual peace is a real thing or not a real thing, or as to whether we may not be deceiving ourselves when we adopt the former alternative, but we must act on the supposition of its being real.»[107] The presupposition of God, soul, and freedom was then a practical concern, for

Morality in itself constitutes a system, but happiness does not, except insofar as it is distributed precisely in accordance with morality. This, however, is possible only in the intelligible world, under a wise author and regent. Reason sees itself as compelled either to assume such a thing, together with life in such a world, which we must regard as a future one, or else to regard the moral laws as empty figments of the brain …[33]: 680 (A 811/B 839)

Kant drew a parallel between the Copernican revolution and the epistemology of his new transcendental philosophy, involving two interconnected foundations of his «critical philosophy»:

- the epistemology of transcendental idealism and

- the moral philosophy of the autonomy of practical reason.

These teachings placed the active, rational human subject at the center of the cognitive and moral worlds. Kant argued that the rational order of the world as known by science was not just the accidental accumulation of sense perceptions.

Conceptual unification and integration is carried out by the mind through concepts or the «categories of the understanding» operating on the perceptual manifold within space and time. The latter are not concepts,[108] but are forms of sensibility that are a priori necessary conditions for any possible experience. Thus the objective order of nature and the causal necessity that operates within it depend on the mind’s processes, the product of the rule-based activity that Kant called «synthesis». There is much discussion among Kant scholars about the correct interpretation of this train of thought.

The ‘two-world’ interpretation regards Kant’s position as a statement of epistemological limitation, that we are not able to transcend the bounds of our own mind, meaning that we cannot access the «thing-in-itself». However, Kant also speaks of the thing in itself or transcendental object as a product of the (human) understanding as it attempts to conceive of objects in abstraction from the conditions of sensibility. Following this line of thought, some interpreters have argued that the thing in itself does not represent a separate ontological domain but simply a way of considering objects by means of the understanding alone—this is known as the two-aspect view.

The notion of the «thing in itself» was much discussed by philosophers after Kant. It was argued that, because the «thing in itself» was unknowable, its existence must not be assumed. Rather than arbitrarily switching to an account that was ungrounded in anything supposed to be the «real», as did the German Idealists, another group arose who asked how our (presumably reliable) accounts of a coherent and rule-abiding universe were actually grounded. This new kind of philosophy became known as Phenomenology, and its founder was Edmund Husserl.

With regard to morality, Kant argued that the source of the good lies not in anything outside the human subject, either in nature or given by God, but rather is only the good will itself. A good will is one that acts from duty in accordance with the universal moral law that the autonomous human being freely gives itself. This law obliges one to treat humanity – understood as rational agency, and represented through oneself as well as others – as an end in itself rather than (merely) as means to other ends the individual might hold. This necessitates practical self-reflection in which we universalize our reasons.

These ideas have largely framed or influenced all subsequent philosophical discussion and analysis. The specifics of Kant’s account generated immediate and lasting controversy. Nevertheless, his theses – that the mind itself necessarily makes a constitutive contribution to its knowledge, that this contribution is transcendental rather than psychological, that philosophy involves self-critical activity, that morality is rooted in human freedom, and that to act autonomously is to act according to rational moral principles – have all had a lasting effect on subsequent philosophy.

Epistemology[edit]

Theory of perception[edit]

Kant defines his theory of perception in his very influential 1781 work the Critique of Pure Reason, which has often been cited as the most significant volume of metaphysics and epistemology in modern philosophy.[109] Kant maintains that understanding of the external world had its foundations not merely in experience, but in both experience and a priori concepts, thus offering a non-empiricist critique of rationalist philosophy, which is what has been referred to as his Copernican revolution.[110]

Firstly, Kant distinguishes between analytic and synthetic propositions:

- Analytic proposition: a proposition whose predicate concept is contained in its subject concept; e.g., «All bachelors are unmarried,» or, «All bodies take up space.»

- Synthetic proposition: a proposition whose predicate concept is not contained in its subject concept; e.g., «All bachelors are alone,» or, «All bodies have weight.»

An analytic proposition is true by nature of the meaning of the words in the sentence—we require no further knowledge than a grasp of the language to understand this proposition. On the other hand, a synthetic statement is one that tells us something about the world. The truth or falsehood of synthetic statements derives from something outside their linguistic content. In this instance, weight is not a necessary predicate of the body; until we are told the heaviness of the body we do not know that it has weight. In this case, experience of the body is required before its heaviness becomes clear. Before Kant’s first Critique, empiricists (cf. Hume) and rationalists (cf. Leibniz) assumed that all synthetic statements required experience to be known.

Kant contests this assumption by claiming that elementary mathematics, like arithmetic, is synthetic a priori, in that its statements provide new knowledge not derived from experience. This becomes part of his over-all argument for transcendental idealism. That is, he argues that the possibility of experience depends on certain necessary conditions—which he calls a priori forms—and that these conditions structure and hold true of the world of experience. His main claims in the «Transcendental Aesthetic» are that mathematic judgments are synthetic a priori and that space and time are not derived from experience but rather are its preconditions.

Once we have grasped the functions of basic arithmetic, we do not need empirical experience to know that 100 + 100 = 200, and so it appears that arithmetic is analytic. However, that it is analytic can be disproved by considering the calculation 5 + 7 = 12: there is nothing in the numbers 5 and 7 by which the number 12 can be inferred.[111] Thus «5 + 7» and «the cube root of 1,728» or «12» are not analytic because their reference is the same but their sense is not—the statement «5 + 7 = 12» tells us something new about the world. It is self-evident, and undeniably a priori, but at the same time it is synthetic. Thus Kant argued that a proposition can be synthetic and a priori. This statement is synthetic because it supposes both quantity in general which is a conceit from our understanding and succession which is a mode of time that belongs to our sensibility. To produce 12 from 5, one needs to add unity to unity seven time. Thus to add is not an operation of pure reason but a process that needs time : one and then one, and again one, etc.[112]

Kant asserts that experience is based on the perception of external objects and a priori knowledge.[113] The external world, he writes, provides those things that we sense. But our mind processes this information and gives it order, allowing us to comprehend it. Our mind supplies the conditions of space and time to experience objects. According to the «transcendental unity of apperception», the concepts of the mind (Understanding) and perceptions or intuitions that garner information from phenomena (Sensibility) are synthesized by comprehension. Without concepts, perceptions are nondescript; without perceptions, concepts are meaningless. Thus the famous statement: «Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions [perceptions] without concepts are blind.»[33]: 193–194 (A 51/B 75)

Kant also claims that an external environment is necessary for the establishment of the self. Although Kant would want to argue that there is no empirical way of observing the self, we can see the logical necessity of the self when we observe that we can have different perceptions of the external environment over time. By uniting these general representations into one global representation, we can see how a transcendental self emerges. «I am therefore conscious of the identical self in regard to the manifold of the representations that are given to me in an intuition because I call them all together my representations, which constitute one.»[33]: 248 (B 135)

According to Guillaume Pigeard de Gurbert, Kant’s philosophy has its unity in the conceit of time, which different uses – speculative, practical, pragmatical, historical or teleogical – is crucial.[114]

Time and space[edit]

The Kantian revolution breaks with previous conceptions of time, either metaphysical (Leibniz) or empirical ones (Hume), in its relation to space. Against metaphysical time and space Kant explains they are not things in themselves but mere shape of the way we feel things. Against empiricism he says that these subjective shapes are a priori—are not given by experience, since any experience of such or such time and space supposes that we are feeling things in the way of time and space. The word «transcendental» qualifies this space and this time lying within the subject that make possible any sensible experience. Kant adds that space itself depends on time, because nothing can be in space without being within time. This crucial idea is settled in 1770, when Kant writes that time includes «absolument tout dans ses rapports, y compris l’espace.»[115] Kant divides time into three modes: permanency, succession, and simultaneity. Many subsequent philosophers inspired by Kant (Heidegger, Hermann Cohen, Béatrice Longuenesse, Bergson, Deleuze, Philonenko) have been accused of missing this triple partition of time.[116]

Categories of the Faculty of Understanding[edit]

Kant statue in the School of Philosophy and Human Sciences (FAFICH) in the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Kant deemed it obvious that we have some objective knowledge of the world, such as, say, Newtonian physics. But this knowledge relies on synthetic, a priori laws of nature, like causality and substance. How is this possible? Kant’s solution was that the subject must supply laws that make experience of objects possible, and that these laws are synthetic, a priori laws of nature that apply to all objects before we experience them. To deduce all these laws, Kant examined experience in general, dissecting in it what is supplied by the mind from what is supplied by the given intuitions. This is commonly called a transcendental deduction.[117]

To begin with, Kant’s distinction between the a posteriori being contingent and particular knowledge, and the a priori being universal and necessary knowledge, must be kept in mind. If we merely connect two intuitions together in a perceiving subject, the knowledge is always subjective because it is derived a posteriori, when what is desired is for the knowledge to be objective, that is, for the two intuitions to refer to the object and hold good of it for anyone at any time, not just the perceiving subject in its current condition. What else is equivalent to objective knowledge besides the a priori (universal and necessary knowledge)? Before knowledge can be objective, it must be incorporated under an a priori category of understanding.[117][118]

For example, if one says «The sun shines on the stone; the stone grows warm», all that one perceives is phenomena. One’s judgment is contingent and holds no necessity. But, if one says «The sunshine causes the stone to warm», one subsumes the perception under the category of causality, which is not found in the perception, and one necessarily synthesizes the concept sunshine with the concept heat, producing a necessarily universally true judgment.[117]

To explain the categories in more detail, they are the preconditions of the construction of objects in the mind. Indeed, to even think of the sun and stone presupposes the category of subsistence, that is, substance. For the categories synthesize the random data of the sensory manifold into intelligible objects. This means that the categories are also the most abstract things one can say of any object whatsoever, and hence one can have an a priori cognition of the totality of all objects of experience if one can list all of them. To do so, Kant formulates another transcendental deduction.[117]

Judgments are, for Kant, the preconditions of any thought. Man thinks via judgments, so all possible judgments must be listed and the perceptions connected within them put aside, so as to make it possible to examine the moments when the understanding is engaged in constructing judgments. For the categories are equivalent to these moments, in that they are concepts of intuitions in general, so far as they are determined by these moments universally and necessarily. Thus by listing all the moments, one can deduce from them all of the categories.[117]

One may now ask: How many possible judgments are there? Kant believed that all the possible propositions within Aristotle’s syllogistic logic are equivalent to all possible judgments, and that all the logical operators within the propositions are equivalent to the moments of the understanding within judgments. Thus he listed Aristotle’s system in four groups of three: quantity (universal, particular, singular), quality (affirmative, negative, infinite), relation (categorical, hypothetical, disjunctive) and modality (problematic, assertoric, apodeictic). The parallelism with Kant’s categories is obvious: quantity (unity, plurality, totality), quality (reality, negation, limitation), relation (substance, cause, community) and modality (possibility, existence, necessity).[117]

The fundamental building blocks of experience, i.e. objective knowledge, are now in place. First there is the sensibility, which supplies the mind with intuitions, and then there is the understanding, which produces judgments of these intuitions and can subsume them under categories. These categories lift the intuitions up out of the subject’s current state of consciousness and place them within consciousness in general, producing universally necessary knowledge. For the categories are innate in any rational being, so any intuition thought within a category in one mind is necessarily subsumed and understood identically in any mind. In other words, we filter what we see and hear.[117]

Transcendental schema doctrine[edit]

Kant ran into a problem with his theory that the mind plays a part in producing objective knowledge. Intuitions and categories are entirely disparate, so how can they interact? Kant’s solution is the (transcendental) schema: a priori principles by which the transcendental imagination connects concepts with intuitions through time. All the principles are temporally bound, for if a concept is purely a priori, as the categories are, then they must apply for all times. Hence there are principles such as substance is that which endures through time, and the cause must always be prior to the effect.[117][119] In the context of transcendental schema the concept of transcendental reflection is of a great importance.[120]

Ethics[edit]

Kant developed his ethics, or moral philosophy, in three works: Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals (1785), Critique of Practical Reason (1788), and Metaphysics of Morals (1797).

In Groundwork, Kant tries to convert our everyday, obvious, rational[121] knowledge of morality into philosophical knowledge. The latter two works used «practical reason», which is based only on things about which reason can tell us, and not deriving any principles from experience, to reach conclusions which can be applied to the world of experience (in the second part of The Metaphysics of Morals).

Kant is known for his theory that there is a single moral obligation, which he called the «Categorical Imperative», and is derived from the concept of duty. Kant defines the demands of moral law as «categorical imperatives». Categorical imperatives are principles that are intrinsically valid; they are good in and of themselves; they must be obeyed in all situations and circumstances, if our behavior is to observe the moral law. The Categorical Imperative provides a test against which moral statements can be assessed. Kant also stated that the moral means and ends can be applied to the categorical imperative, that rational beings can pursue certain «ends» using the appropriate «means». Ends based on physical needs or wants create hypothetical imperatives. The categorical imperative can only be based on something that is an «end in itself», that is, an end that is not a means to some other need, desire, or purpose.[122] Kant believed that the moral law is a principle of reason itself, and is not based on contingent facts about the world, such as what would make us happy, but to act on the moral law which has no other motive than «worthiness to be happy».[33]: 677 (A 806/B 834) Accordingly, he believed that moral obligation applies only to rational agents.[123]

Unlike a hypothetical imperative, a categorical imperative is an unconditional obligation; it has the force of an obligation regardless of our will or desires[124] In Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals (1785) Kant enumerated three formulations of the categorical imperative that he believed to be roughly equivalent.[125] In the same book, Kant stated:

- Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.[126]

According to Kant, one cannot make exceptions for oneself. The philosophical maxim on which one acts should always be considered to be a universal law without exception. One cannot allow oneself to do a particular action unless one thinks it appropriate that the reason for the action should become a universal law. For example, one should not steal, however dire the circumstances—because, by permitting oneself to steal, one makes stealing a universally acceptable act. This is the first formulation of the categorical imperative, often known as the universalizability principle.

Kant believed that, if an action is not done with the motive of duty, then it is without moral value. He thought that every action should have pure intention behind it; otherwise, it is meaningless. The final result is not the most important aspect of an action; rather, how the person feels while carrying out the action is the time when value is attached to the result.

In Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, Kant also posited the «counter-utilitarian idea that there is a difference between preferences and values, and that considerations of individual rights temper calculations of aggregate utility», a concept that is an axiom in economics:[127]

Everything has either a price or a dignity. Whatever has a price can be replaced by something else as its equivalent; on the other hand, whatever is above all price, and therefore admits of no equivalent, has a dignity. But that which constitutes the condition under which alone something can be an end in itself does not have mere relative worth, i.e., price, but an intrinsic worth, i.e., a dignity. (p. 53, italics in original).

A phrase quoted by Kant, which is used to summarize the counter-utilitarian nature of his moral philosophy, is Fiat justitia, pereat mundus («Let justice be done, though the world perish»), which he translates loosely as «Let justice reign even if all the rascals in the world should perish from it». This appears in his 1795 Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch («Zum ewigen Frieden. Ein philosophischer Entwurf«), Appendix 1.[128][129][130]

First formulation[edit]

In his Metaphysics, Immanuel Kant introduced the categorical imperative: «Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.»

The first formulation (Formula of Universal Law) of the moral imperative «requires that the maxims be chosen as though they should hold as universal laws of nature».[125] This formulation in principle has as its supreme law the creed «Always act according to that maxim whose universality as a law you can at the same time will» and is the «only condition under which a will can never come into conflict with itself [….]»[131]

One interpretation of the first formulation is called the «universalizability test».[132] An agent’s maxim, according to Kant, is his «subjective principle of human actions»: that is, what the agent believes is his reason to act.[133] The universalisability test has five steps:

- Find the agent’s maxim (i.e., an action paired with its motivation). Take, for example, the declaration «I will lie for personal benefit». Lying is the action; the motivation is to fulfill some sort of desire. Together, they form the maxim.

- Imagine a possible world in which everyone in a similar position to the real-world agent followed that maxim.

- Decide if contradictions or irrationalities would arise in the possible world as a result of following the maxim.

- If a contradiction or irrationality would arise, acting on that maxim is not allowed in the real world.

- If there is no contradiction, then acting on that maxim is permissible, and is sometimes required.

(For a modern parallel, see John Rawls’ hypothetical situation, the original position.)

Second formulation[edit]

The second formulation (or Formula of the End in Itself) holds that «the rational being, as by its nature an end and thus as an end in itself, must serve in every maxim as the condition restricting all merely relative and arbitrary ends».[125] The principle dictates that you «[a]ct with reference to every rational being (whether yourself or another) so that it is an end in itself in your maxim», meaning that the rational being is «the basis of all maxims of action» and «must be treated never as a mere means but as the supreme limiting condition in the use of all means, i.e., as an end at the same time».[134]

Third formulation[edit]

The third formulation (i.e. Formula of Autonomy) is a synthesis of the first two and is the basis for the «complete determination of all maxims». It states «that all maxims which stem from autonomous legislation ought to harmonize with a possible realm of ends as with a realm of nature».[125]

In principle, «So act as if your maxims should serve at the same time as the universal law (of all rational beings)», meaning that we should so act that we may think of ourselves as «a member in the universal realm of ends», legislating universal laws through our maxims (that is, a universal code of conduct), in a «possible realm of ends».[135] No one may elevate themselves above the universal law, therefore it is one’s duty to follow the maxim(s).

Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason[edit]

Commentators, starting in the 20th century, have tended to see Kant as having a strained relationship with religion, though this was not the prevalent view in the 19th century. Karl Leonhard Reinhold, whose letters first made Kant famous, wrote «I believe that I may infer without reservation that the interest of religion, and of Christianity in particular, accords completely with the result of the Critique of Reason.»[136] Johann Schultz, who wrote one of the first Kant commentaries, wrote «And does not this system itself cohere most splendidly with the Christian religion? Do not the divinity and beneficence of the latter become all the more evident?»[137] This view continued throughout the 19th century, as noted by Friedrich Nietzsche, who said «Kant’s success is merely a theologian’s success.»[138] The reason for these views was Kant’s moral theology, and the widespread belief that his philosophy was the great antithesis to Spinozism, which had been convulsing the European academy for much of the 18th century. Spinozism was widely seen as the cause of the Pantheism controversy, and as a form of sophisticated pantheism or even atheism. As Kant’s philosophy disregarded the possibility of arguing for God through pure reason alone, for the same reasons it also disregarded the possibility of arguing against God through pure reason alone. This, coupled with his moral philosophy (his argument that the existence of morality is a rational reason why God and an afterlife do and must exist), was the reason he was seen by many, at least through the end of the 19th century, as a great defender of religion in general and Christianity in particular.[citation needed]

Kant articulates his strongest criticisms of the organization and practices of religious organizations to those that encourage what he sees as a religion of counterfeit service to God.[139] Among the major targets of his criticism are external ritual, superstition and a hierarchical church order. He sees these as efforts to make oneself pleasing to God in ways other than conscientious adherence to the principle of moral rightness in choosing and acting upon one’s maxims. Kant’s criticisms on these matters, along with his rejection of certain theoretical proofs grounded in pure reason (particularly the ontological argument) for the existence of God and his philosophical commentary on some Christian doctrines, have resulted in interpretations that see Kant as hostile to religion in general and Christianity in particular (e.g., Walsh 1967). Nevertheless, other interpreters consider that Kant was trying to mark off defensible from indefensible Christian belief.[140] Kant sees in Jesus Christ the affirmation of a «pure moral disposition of the heart» that «can make man well-pleasing to God».[139] Regarding Kant’s conception of religion, some critics have argued that he was sympathetic to deism.[141] Other critics have argued that Kant’s moral conception moves from deism to theism (as moral theism), for example Allen W. Wood[142] and Merold Westphal.[143] As for Kant’s book Religion within the Bounds of Bare Reason,[95] it was emphasized that Kant reduced religiosity to rationality, religion to morality and Christianity to ethics.[144] However, many interpreters, including Allen W. Wood[145] and Lawrence Pasternack,[146] now agree with Stephen Palmquist’s claim that a better way of reading Kant’s Religion is to see him as raising morality to the status of religion.[147]

Idea of freedom[edit]

In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant distinguishes between the transcendental idea of freedom, which as a psychological concept is «mainly empirical» and refers to «whether a faculty of beginning a series of successive things or states from itself is to be assumed»[33]: 486 (A 448/B 467) and the practical concept of freedom as the independence of our will from the «coercion» or «necessitation through sensuous impulses». Kant finds it a source of difficulty that the practical idea of freedom is founded on the transcendental idea of freedom,[33]: 533 (A 533–4/B 561–2) but for the sake of practical interests uses the practical meaning, taking «no account of… its transcendental meaning,» which he feels was properly «disposed of» in the Third Antinomy, and as an element in the question of the freedom of the will is for philosophy «a real stumbling block» that has embarrassed speculative reason.[33]: 486 (A 448/B 467)

Kant calls practical «everything that is possible through freedom», and the pure practical laws that are never given through sensuous conditions but are held analogously with the universal law of causality are moral laws. Reason can give us only the «pragmatic laws of free action through the senses», but pure practical laws given by reason a priori[33]: 486 (A 448/B 467) dictate «what is to be done».[33]: 674–676 (A 800–2/B 828–30) (The same distinction of transcendental and practical meaning can be applied to the idea of God, with the proviso that the practical concept of freedom can be experienced.[148])

Categories of freedom[edit]

In the Critique of Practical Reason, at the end of the second Main Part of the Analytics,[149] Kant introduces the categories of freedom, in analogy with the categories of understanding their practical counterparts. Kant’s categories of freedom apparently function primarily as conditions for the possibility for actions (i) to be free, (ii) to be understood as free and (iii) to be morally evaluated. For Kant, although actions as theoretical objects are constituted by means of the theoretical categories, actions as practical objects (objects of practical use of reason, and which can be good or bad) are constituted by means of the categories of freedom. Only in this way can actions, as phenomena, be a consequence of freedom, and be understood and evaluated as such.[150]

Aesthetic philosophy[edit]

Kant discusses the subjective nature of aesthetic qualities and experiences in Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (1764). Kant’s contribution to aesthetic theory is developed in the Critique of Judgment (1790) where he investigates the possibility and logical status of «judgments of taste.» In the «Critique of Aesthetic Judgment,» the first major division of the Critique of Judgment, Kant used the term «aesthetic» in a manner that, according to Kant scholar W.H. Walsh, differs from its modern sense.[151] In the Critique of Pure Reason, to note essential differences between judgments of taste, moral judgments, and scientific judgments, Kant abandoned the term «aesthetic» as «designating the critique of taste,» noting that judgments of taste could never be «directed» by «laws a priori.»[152] After A. G. Baumgarten, who wrote Aesthetica (1750–58),[153] Kant was one of the first philosophers to develop and integrate aesthetic theory into a unified and comprehensive philosophical system, utilizing ideas that played an integral role throughout his philosophy.[154]

In the chapter «Analytic of the Beautiful» in the Critique of Judgment, Kant states that beauty is not a property of an artwork or natural phenomenon, but is instead consciousness of the pleasure that attends the ‘free play’ of the imagination and the understanding. Even though it appears that we are using reason to decide what is beautiful, the judgment is not a cognitive judgment,[155] «and is consequently not logical, but aesthetical» (§ 1). A pure judgement of taste is subjective since it refers to the emotional response of the subject and is based upon nothing but esteem for an object itself: it is a disinterested pleasure, and we feel that pure judgements of taste (i.e. judgements of beauty), lay claim to universal validity (§§ 20–22). It is important to note that this universal validity is not derived from a determinate concept of beauty but from common sense (§40). Kant also believed that a judgement of taste shares characteristics engaged in a moral judgement: both are disinterested, and we hold them to be universal. In the chapter «Analytic of the Sublime» Kant identifies the sublime as an aesthetic quality that, like beauty, is subjective, but unlike beauty refers to an indeterminate relationship between the faculties of the imagination and of reason, and shares the character of moral judgments in the use of reason. The feeling of the sublime, divided into two distinct modes (the mathematical and the dynamical sublime), describes two subjective moments that concern the relationship of the faculty of the imagination to reason. Some commentators[156] argue that Kant’s critical philosophy contains a third kind of the sublime, the moral sublime, which is the aesthetic response to the moral law or a representation, and a development of the «noble» sublime in Kant’s theory of 1764. The mathematical sublime results from the failure of the imagination to comprehend natural objects that appear boundless and formless, or appear «absolutely great» (§§ 23–25). This imaginative failure is then recuperated through the pleasure taken in reason’s assertion of the concept of infinity. In this move the faculty of reason proves itself superior to our fallible sensible self (§§ 25–26). In the dynamical sublime there is the sense of annihilation of the sensible self as the imagination tries to comprehend a vast might. This power of nature threatens us but through the resistance of reason to such sensible annihilation, the subject feels a pleasure and a sense of the human moral vocation. This appreciation of moral feeling through exposure to the sublime helps to develop moral character.

Kant developed a theory of humor (§ 54) that has been interpreted as an «incongruity» theory. He illustrated his theory of humor by telling three narrative jokes in the Critique of Judgment. He thought that the physiological impact of humor is akin to that of music.[157] His knowledge of music, however, has been reported to be much weaker than his sense of humor: He told many more jokes throughout his lectures and writings.[158]

Kant developed a distinction between an object of art as a material value subject to the conventions of society and the transcendental condition of the judgment of taste as a «refined» value in his Idea of A Universal History (1784). In the Fourth and Fifth Theses of that work he identified all art as the «fruits of unsociableness» due to men’s «antagonism in society»[159] and, in the Seventh Thesis, asserted that while such material property is indicative of a civilized state, only the ideal of morality and the universalization of refined value through the improvement of the mind «belongs to culture».[160]

Political philosophy[edit]

In Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch,[161] Kant listed several conditions that he thought necessary for ending wars and creating a lasting peace. They included a world of constitutional republics.[162] His classical republican theory was extended in the Science of Right, the first part of the Metaphysics of Morals (1797).[163] Kant believed that universal history leads to the ultimate world of republican states at peace, but his theory was not pragmatic. The process was described in «Perpetual Peace» as natural rather than rational:

The guarantee of perpetual peace is nothing less than that great artist, nature…In her mechanical course we see that her aim is to produce a harmony among men, against their will, and indeed through their discord. As a necessity working according to laws we do not know, we call it destiny. But, considering its designs in universal history, we call it «providence,» inasmuch as we discern in it the profound wisdom of a higher cause which predetermines the course of nature and directs it to the objective final end of the human race.[164]

Kant’s political thought can be summarized as republican government and international organization. «In more characteristically Kantian terms, it is doctrine of the state based upon the law (Rechtsstaat) and of eternal peace. Indeed, in each of these formulations, both terms express the same idea: that of legal constitution or of ‘peace through law’. Kant’s political philosophy, being essentially a legal doctrine, rejects by definition the opposition between moral education and the play of passions as alternate foundations for social life. The state is defined as the union of men under law. The state is constituted by laws which are necessary a priori because they flow from the very concept of law. «A regime can be judged by no other criteria nor be assigned any other functions, than those proper to the lawful order as such.»[165]

He opposed «democracy,» which at his time meant direct democracy, believing that majority rule posed a threat to individual liberty. He stated, «…democracy is, properly speaking, necessarily a despotism, because it establishes an executive power in which ‘all’ decide for or even against one who does not agree; that is, ‘all,’ who are not quite all, decide, and this is a contradiction of the general will with itself and with freedom.»[166] As with most writers at the time, he distinguished three forms of government i.e. democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy with mixed government as the most ideal form of it.

Anthropology[edit]

5 DM 1974 D silver coin commemorating the 250th birthday of Immanuel Kant in Königsberg

Kant lectured on anthropology, the study of human nature, for twenty-three and a half years.[167] His Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View was published in 1798. (This was the subject of Michel Foucault’s secondary dissertation for his State doctorate, Introduction to Kant’s Anthropology.) Kant’s Lectures on Anthropology were published for the first time in 1997 in German.[168] Introduction to Kant’s Anthropology was translated into English and published by the Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy series in 2006.[169]

Kant was among the first people of his time to introduce anthropology as an intellectual area of study, long before the field gained popularity, and his texts are considered to have advanced the field. His point of view was to influence the works of later philosophers such as Martin Heidegger and Paul Ricoeur.

Kant was also the first to suggest using a dimensionality approach to human diversity. He analyzed the nature of the Hippocrates-Galen four temperaments and plotted them in two dimensions: (1) «activation», or energetic aspect of behaviour, and (2) «orientation on emotionality».[170] Cholerics were described as emotional and energetic; Phlegmatics as balanced and weak; Sanguines as balanced and energetic, and Melancholics as emotional and weak. These two dimensions reappeared in all subsequent models of temperament and personality traits.

Kant viewed anthropology in two broad categories: (1) the physiological approach, which he referred to as «what nature makes of the human being»; and (2) the pragmatic approach, which explored the things that a human «can and should make of himself.»[171]

Racism[edit]