Vasilisa the Beautiful (Russian: Василиса Прекрасная) or Vasilisa the Fair is a Russian fairy tale collected by Alexander Afanasyev in Narodnye russkie skazki.[1]

Synopsis[edit]

By his first wife, a merchant had a single daughter, who was known as Vasilisa the Beautiful. When the girl was eight years old, her mother died; when it became clear that she was dying, she called Vasilisa to her bedside, where she gave Vasilisa a tiny, wooden, one-of-a-kind doll talisman (a Motanka doll), with explicit instructions; Vasilisa must always keep the doll somewhere on her person and never allow anyone (not even her father) to see it or even know of its existence; whenever Vasilisa should find herself in need of help, whenever overcoming evil, obstacles, or just be in need of advice or just some comfort, all that she needs to do is to offer it a little to eat and a little to drink, and then, whatever Vasilisa’s need, it would help her. Once her mother had died, Vasilisa offered it a little to drink and a little to eat, and it comforted her in her time of grief.

After the mourning period, Vasilisa’s father, in need of a mother for Vasilisa and to keep house, decided he needed to remarry; for his new wife, he chose a widow with two daughters of her own from her previous marriage, thinking that she would make the perfect new mother figure for his daughter. However, Vasilisa’s step-mother, when not in the presence of her new husband, was very cruel to her, as were Vasilisa’s step-sisters, but with the help of the doll, Vasilisa was always able to perform all the household tasks imposed on her. When Vasilisa came of age and young men came trying to woo her, the step-mother rejected them all on the pretence that it was not proper for younger girls to marry before the older girls, and none of the suitors wished to marry Vasilisa’s step-sisters.

One day, the merchant had to embark on an extended journey out of town for business. His wife, seeing an opportunity to dispose of Vasilisa, sold the house on the same day he left and moved them all away to a gloomy hut by a forest where rumour said that Baba Yaga resided. When not over-working Vasilisa with housework, the step-mother would also send her out deep into the woods on superfluous errands, with the intentions of either marring her step-daughter’s enduring beauty or increasing the chances of Baba Yaga discovering her and eating her, keeping the step-mother’s hands clean of any perceived culpability. Only thanks to the doll was Vasilisa able to keep completing the scores of housework and remain safe whenever out of the house, always returning unharmed. The step-mother, only becoming frustrated with how her step-daughter’s continued luck, not only in remaining alive, but also in how Vasilisa’s beauty continued to grow, decided to change tactics. One night, before bed, she gave each of the girls a task and put out all the fires except a single candle. Her older daughter then put out the candle (as instructed by her mother), whereupon the step-sisters bodily forced Vasilisa out of the house and demanded that she go to fetch light from Baba Yaga’s hut.

The doll advised her to go, and she went. While she was walking, a mysterious man rode by her in the hours before dawn, dressed in white, riding a white horse whose equipment was all white; then a similar rider in red. She came to a house that stood on chicken legs and was walled by a fence made of human bones. A black rider, like the white and red riders, rode past her, and night fell, whereupon the eye sockets of the skulls began to glow, like lanterns. Vasilisa was too frightened to run away, and so Baba Yaga found her when she arrived in her giant, flying mortar. Once she learned why the girl was there, Baba Yaga said that Vasilisa must perform tasks to earn the fire, or be killed; she was to clean the house and yard, wash Baba Yaga’s laundry, and cook her a meal enough for a dozen (which Baba Yaga eats all by herself). She was also required to separate grains of rotten corn from sound corn, and separate poppy seeds from grains of soil. Baba Yaga left the hut for the day and Vasilisa despaired, as she worked herself into exhaustion. When all hope of completing the tasks seemed lost, the doll whispered that she would complete the tasks for Vasilisa, and that the girl should sleep.

At dawn, the white rider passed; at or before noon, the red. As the black rider rode past, Baba Yaga returned and could complain of nothing. She bade three pairs of disembodied hands seize the corn to squeeze the oil from it, then asked Vasilisa if she had any questions.

Vasilisa asked about the riders’ identities and was told that the white one was Day, the red one the Sun, and the black one Night. But when Vasilisa thought of asking about the disembodied hands, the doll quivered in her pocket. Vasilisa realized she should not ask, and told Baba Yaga she had no further questions. In return, Baba Yaga enquired as to the cause of Vasilisa’s success. On hearing the answer «by my mother’s blessing», Baba Yaga, who wanted nobody with any kind of blessing in her presence, threw Vasilisa out of her house, and sent her home with a skull-lantern full of burning coals, to provide light for her step-family.

Upon her return, Vasilisa found that, since sending her out on her task, her step-family had been unable to light any candles or fire in their home. Even lamps and candles that might be brought in from outside were useless for the purpose, as all were snuffed out the second they were carried over the threshold. The coals brought in the skull-lantern burned Vasilisa’s stepmother and stepsisters to ashes, and Vasilisa buried the skull according to its instructions, so no person would ever be harmed by it.[2]

Later, Vasilisa became an assistant to a maker of cloth in Russia’s capital city, where she became so skilled at her work that the Tsar himself noticed her skill; he later married Vasilisa.

Variants[edit]

In some versions, the tale ends with the death of the stepmother and stepsisters, and Vasilisa lives peacefully with her father after their removal. This lack of a wedding is unusual in a tale with a grown heroine, although some, such as Jack and the Beanstalk, do feature it.[3]

According to Jiří Polívka, in a Slovak tale from West Hungary, the heroine meets a knight or lord clad in all red, riding a red horse, with a red bird on his hand and red dog by his side. She also meets two similarly dressed lords: one in all white, and the other in all black. The heroine’s stepmother explains that the red lord was the Morning, the white lord the Day and the black lord the Night.[4]

Interpretations[edit]

The white, red, and black riders appear in other tales of Baba Yaga and are often interpreted to give her a mythological significance.

In common with many folklorists of his day, Alexander Afanasyev regarded many tales as primitive ways of viewing nature. In such an interpretation, he regarded this fairy tale as depicting the conflict between the sunlight (Vasilisa), the storm (her stepmother), and dark clouds (her stepsisters).[5]

Clarissa Pinkola Estés interprets the story as a tale of female liberation, Vasilisa’s journey from subservience to strength and independence. She interprets Baba Yaga as the «wild feminine» principle that Vasilisa has been separated from, which, by obeying and learning how to nurture, she learns and grows from.[6]

Related and eponymous works[edit]

Edith Hodgetts included an English translation of this story in her 1890 collection Tales and Legends from the Land of the Tzar.

Aleksandr Rou made a film entitled Vasilisa the Beautiful in 1940, however, it was based on a different tale – The Frog Tsarevna.[7] American author Elizabeth Winthrop wrote a children’s book – Vasilissa the Beautiful: a Russian Folktale (HarperCollins, 1991), illustrated by Alexander Koshkin. There is also a Soviet cartoon – Vasilisa the Beautiful, but it is also based on the Frog Tsarevna tale.

The story is also part of a collection of Russian fairy tales titled Vasilisa The Beautiful: Russian Fairy Tales published by Raduga Publishers first in 1966. The book was edited by Irina Zheleznova, who also translated many of the stories in the book from the Russian including Vasilisa The Beautiful. The book was also translated in Hindi and Marathi.

The 1998 feminist fantasy anthology Did You Say Chicks?! contains two alternate reimaginings of «Vasilisa the Beautiful». Laura Frankos’ «Slue-Foot Sue and the Witch in the Woods» humorously supplants Vasilisa with the American explorer Slue-Foot Sue, wife of Pecos Bill. «A Bone to Pick» by Marina Frants and Keith R.A. DeCandido is somewhat more serious in tone, reimagining Yaga as a firm but benevolent mentor and Vasilisa as her fiercely loyal protégé, who is also described as ugly rather than beautiful. Frants’ and DeCandido’s story was followed up in the succeeding volume Chicks ‘n Chained Males (1999) with the sequel «Death Becomes Him,» which is credited to Frants alone and features Koschei the Deathless as the antagonist.

Vasilisa appears in the 2007 comic book Hellboy: Darkness Calls to assist Hellboy against Koschei the Deathless with her usual story of the Baba Yaga. The book also includes other characters of Slavic folklore, such as a Domovoi making an appearance.

A graphic version of the Vasilisa story, drawn by Kadi Fedoruk (creator of the webcomic Blindsprings), appears in Valor: Swords, a comic anthology of re-imagined fairy tales that pays homage to the strength, resourcefulness, and cunning of female heroines in fairy tales through recreations of time-honored tales and brand new stories, published by Fairylogue Press in 2014 following a successful Kickstarter campaign.

The novel Vassa in the Night by Sarah Porter is based on this folktale with a modern twist.[8]

The book Vasilisa the Terrible: A Baba Yaga Story flips the script by painting Vasilisa as a villain and Baba Yaga as an elderly woman who is framed by the young girl.[9][10]

In Annie Baker’s 2017 play The Antipodes, one of the characters, Sarah, tells a story from her childhood that is reminiscent of the story of Vasilisa.

The book series Vampire Academy by Richelle Mead features a supporting character named Vasilisa, and is mentioned that she was named after Vasilisa from Vasilisa the Beautiful.

See also[edit]

- Fairer-than-a-Fairy

- Folklore of Russia

- Vasilisa (name)

- The Two Caskets

- Cinderella

References[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- ^ Alexander Afanasyev, Narodnye russkie skazki, «Vasilissa the Beautiful»

- ^ Santo, Suzanne Banay (2012). Returning: A Tale of Vasilisa and Baba Yaga. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Red Butterfly Publications. p. 24. ISBN 9781475236019.

- ^ Maria Tatar, Off with Their Heads! p. 199 ISBN 0-691-06943-3

- ^ Polívka, Georg. «Personifikationen von Tag und Nacht im Volkmärchen». In: Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 26 (1916): 315.

- ^ Maria Tatar, p 334, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^

Estés, Clarissa Pinkola (1992). Women Who Run with the Wolves. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40987-4. - ^ James Graham, «Baba Yaga in Film[Usurped!]«

- ^ Porter, Sarah (2016). Vassa in the Night. Tor Teen, New York. ISBN 9780765380548.

- ^ Taylor, April A. (2018). Vasilisa the Terrible: A Baba Yaga Story. ISBN 9781980441618.

- ^ «Goodreads».

Vasilisa the Beautiful (Russian: Василиса Прекрасная) or Vasilisa the Fair is a Russian fairy tale collected by Alexander Afanasyev in Narodnye russkie skazki.[1]

Synopsis[edit]

By his first wife, a merchant had a single daughter, who was known as Vasilisa the Beautiful. When the girl was eight years old, her mother died; when it became clear that she was dying, she called Vasilisa to her bedside, where she gave Vasilisa a tiny, wooden, one-of-a-kind doll talisman (a Motanka doll), with explicit instructions; Vasilisa must always keep the doll somewhere on her person and never allow anyone (not even her father) to see it or even know of its existence; whenever Vasilisa should find herself in need of help, whenever overcoming evil, obstacles, or just be in need of advice or just some comfort, all that she needs to do is to offer it a little to eat and a little to drink, and then, whatever Vasilisa’s need, it would help her. Once her mother had died, Vasilisa offered it a little to drink and a little to eat, and it comforted her in her time of grief.

After the mourning period, Vasilisa’s father, in need of a mother for Vasilisa and to keep house, decided he needed to remarry; for his new wife, he chose a widow with two daughters of her own from her previous marriage, thinking that she would make the perfect new mother figure for his daughter. However, Vasilisa’s step-mother, when not in the presence of her new husband, was very cruel to her, as were Vasilisa’s step-sisters, but with the help of the doll, Vasilisa was always able to perform all the household tasks imposed on her. When Vasilisa came of age and young men came trying to woo her, the step-mother rejected them all on the pretence that it was not proper for younger girls to marry before the older girls, and none of the suitors wished to marry Vasilisa’s step-sisters.

One day, the merchant had to embark on an extended journey out of town for business. His wife, seeing an opportunity to dispose of Vasilisa, sold the house on the same day he left and moved them all away to a gloomy hut by a forest where rumour said that Baba Yaga resided. When not over-working Vasilisa with housework, the step-mother would also send her out deep into the woods on superfluous errands, with the intentions of either marring her step-daughter’s enduring beauty or increasing the chances of Baba Yaga discovering her and eating her, keeping the step-mother’s hands clean of any perceived culpability. Only thanks to the doll was Vasilisa able to keep completing the scores of housework and remain safe whenever out of the house, always returning unharmed. The step-mother, only becoming frustrated with how her step-daughter’s continued luck, not only in remaining alive, but also in how Vasilisa’s beauty continued to grow, decided to change tactics. One night, before bed, she gave each of the girls a task and put out all the fires except a single candle. Her older daughter then put out the candle (as instructed by her mother), whereupon the step-sisters bodily forced Vasilisa out of the house and demanded that she go to fetch light from Baba Yaga’s hut.

The doll advised her to go, and she went. While she was walking, a mysterious man rode by her in the hours before dawn, dressed in white, riding a white horse whose equipment was all white; then a similar rider in red. She came to a house that stood on chicken legs and was walled by a fence made of human bones. A black rider, like the white and red riders, rode past her, and night fell, whereupon the eye sockets of the skulls began to glow, like lanterns. Vasilisa was too frightened to run away, and so Baba Yaga found her when she arrived in her giant, flying mortar. Once she learned why the girl was there, Baba Yaga said that Vasilisa must perform tasks to earn the fire, or be killed; she was to clean the house and yard, wash Baba Yaga’s laundry, and cook her a meal enough for a dozen (which Baba Yaga eats all by herself). She was also required to separate grains of rotten corn from sound corn, and separate poppy seeds from grains of soil. Baba Yaga left the hut for the day and Vasilisa despaired, as she worked herself into exhaustion. When all hope of completing the tasks seemed lost, the doll whispered that she would complete the tasks for Vasilisa, and that the girl should sleep.

At dawn, the white rider passed; at or before noon, the red. As the black rider rode past, Baba Yaga returned and could complain of nothing. She bade three pairs of disembodied hands seize the corn to squeeze the oil from it, then asked Vasilisa if she had any questions.

Vasilisa asked about the riders’ identities and was told that the white one was Day, the red one the Sun, and the black one Night. But when Vasilisa thought of asking about the disembodied hands, the doll quivered in her pocket. Vasilisa realized she should not ask, and told Baba Yaga she had no further questions. In return, Baba Yaga enquired as to the cause of Vasilisa’s success. On hearing the answer «by my mother’s blessing», Baba Yaga, who wanted nobody with any kind of blessing in her presence, threw Vasilisa out of her house, and sent her home with a skull-lantern full of burning coals, to provide light for her step-family.

Upon her return, Vasilisa found that, since sending her out on her task, her step-family had been unable to light any candles or fire in their home. Even lamps and candles that might be brought in from outside were useless for the purpose, as all were snuffed out the second they were carried over the threshold. The coals brought in the skull-lantern burned Vasilisa’s stepmother and stepsisters to ashes, and Vasilisa buried the skull according to its instructions, so no person would ever be harmed by it.[2]

Later, Vasilisa became an assistant to a maker of cloth in Russia’s capital city, where she became so skilled at her work that the Tsar himself noticed her skill; he later married Vasilisa.

Variants[edit]

In some versions, the tale ends with the death of the stepmother and stepsisters, and Vasilisa lives peacefully with her father after their removal. This lack of a wedding is unusual in a tale with a grown heroine, although some, such as Jack and the Beanstalk, do feature it.[3]

According to Jiří Polívka, in a Slovak tale from West Hungary, the heroine meets a knight or lord clad in all red, riding a red horse, with a red bird on his hand and red dog by his side. She also meets two similarly dressed lords: one in all white, and the other in all black. The heroine’s stepmother explains that the red lord was the Morning, the white lord the Day and the black lord the Night.[4]

Interpretations[edit]

The white, red, and black riders appear in other tales of Baba Yaga and are often interpreted to give her a mythological significance.

In common with many folklorists of his day, Alexander Afanasyev regarded many tales as primitive ways of viewing nature. In such an interpretation, he regarded this fairy tale as depicting the conflict between the sunlight (Vasilisa), the storm (her stepmother), and dark clouds (her stepsisters).[5]

Clarissa Pinkola Estés interprets the story as a tale of female liberation, Vasilisa’s journey from subservience to strength and independence. She interprets Baba Yaga as the «wild feminine» principle that Vasilisa has been separated from, which, by obeying and learning how to nurture, she learns and grows from.[6]

Related and eponymous works[edit]

Edith Hodgetts included an English translation of this story in her 1890 collection Tales and Legends from the Land of the Tzar.

Aleksandr Rou made a film entitled Vasilisa the Beautiful in 1940, however, it was based on a different tale – The Frog Tsarevna.[7] American author Elizabeth Winthrop wrote a children’s book – Vasilissa the Beautiful: a Russian Folktale (HarperCollins, 1991), illustrated by Alexander Koshkin. There is also a Soviet cartoon – Vasilisa the Beautiful, but it is also based on the Frog Tsarevna tale.

The story is also part of a collection of Russian fairy tales titled Vasilisa The Beautiful: Russian Fairy Tales published by Raduga Publishers first in 1966. The book was edited by Irina Zheleznova, who also translated many of the stories in the book from the Russian including Vasilisa The Beautiful. The book was also translated in Hindi and Marathi.

The 1998 feminist fantasy anthology Did You Say Chicks?! contains two alternate reimaginings of «Vasilisa the Beautiful». Laura Frankos’ «Slue-Foot Sue and the Witch in the Woods» humorously supplants Vasilisa with the American explorer Slue-Foot Sue, wife of Pecos Bill. «A Bone to Pick» by Marina Frants and Keith R.A. DeCandido is somewhat more serious in tone, reimagining Yaga as a firm but benevolent mentor and Vasilisa as her fiercely loyal protégé, who is also described as ugly rather than beautiful. Frants’ and DeCandido’s story was followed up in the succeeding volume Chicks ‘n Chained Males (1999) with the sequel «Death Becomes Him,» which is credited to Frants alone and features Koschei the Deathless as the antagonist.

Vasilisa appears in the 2007 comic book Hellboy: Darkness Calls to assist Hellboy against Koschei the Deathless with her usual story of the Baba Yaga. The book also includes other characters of Slavic folklore, such as a Domovoi making an appearance.

A graphic version of the Vasilisa story, drawn by Kadi Fedoruk (creator of the webcomic Blindsprings), appears in Valor: Swords, a comic anthology of re-imagined fairy tales that pays homage to the strength, resourcefulness, and cunning of female heroines in fairy tales through recreations of time-honored tales and brand new stories, published by Fairylogue Press in 2014 following a successful Kickstarter campaign.

The novel Vassa in the Night by Sarah Porter is based on this folktale with a modern twist.[8]

The book Vasilisa the Terrible: A Baba Yaga Story flips the script by painting Vasilisa as a villain and Baba Yaga as an elderly woman who is framed by the young girl.[9][10]

In Annie Baker’s 2017 play The Antipodes, one of the characters, Sarah, tells a story from her childhood that is reminiscent of the story of Vasilisa.

The book series Vampire Academy by Richelle Mead features a supporting character named Vasilisa, and is mentioned that she was named after Vasilisa from Vasilisa the Beautiful.

See also[edit]

- Fairer-than-a-Fairy

- Folklore of Russia

- Vasilisa (name)

- The Two Caskets

- Cinderella

References[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- ^ Alexander Afanasyev, Narodnye russkie skazki, «Vasilissa the Beautiful»

- ^ Santo, Suzanne Banay (2012). Returning: A Tale of Vasilisa and Baba Yaga. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Red Butterfly Publications. p. 24. ISBN 9781475236019.

- ^ Maria Tatar, Off with Their Heads! p. 199 ISBN 0-691-06943-3

- ^ Polívka, Georg. «Personifikationen von Tag und Nacht im Volkmärchen». In: Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 26 (1916): 315.

- ^ Maria Tatar, p 334, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^

Estés, Clarissa Pinkola (1992). Women Who Run with the Wolves. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40987-4. - ^ James Graham, «Baba Yaga in Film[Usurped!]«

- ^ Porter, Sarah (2016). Vassa in the Night. Tor Teen, New York. ISBN 9780765380548.

- ^ Taylor, April A. (2018). Vasilisa the Terrible: A Baba Yaga Story. ISBN 9781980441618.

- ^ «Goodreads».

КАК ВАСИЛИСЫ ПРЕМУДРАЯ

И ПРЕКРАСНАЯ ПОЯВИЛИСЬ

В РУССКОМ ФОЛЬКЛОРЕ

И БЫЛИ ЛИ У НИХ ПРОТОТИПЫ?

КАК ВАСИЛИСЫ ПРЕМУДРАЯ

И ПРЕКРАСНАЯ ПОЯВИЛИСЬ

В РУССКОМ ФОЛЬКЛОРЕ

И БЫЛИ ЛИ У НИХ ПРОТОТИПЫ?

Во многих сказках Василиса испытывает потенциального жениха самыми странными и даже пугающими способами вроде прыжка в котел с кипятком.

Имя Василиса, означающее в переводе с греческого «жена царя» или «царица», попало на Русь из Византии не позднее XIII века. В Повести временных лет, датированной началом XII столетия, это имя не упоминалось ни разу. А первыми известными Василисами были дочь ростовского князя Василиса Дмитриевна, жившая на рубеже XIII–XIV веков, а также еще одна ростовская княжна — Василиса Константиновна, которая жила в XIV веке.

Вероятно, в русские сказки это имя пришло уже после того, как прочно закрепилось в обиходе. Но сама героиня и сюжеты с ее участием существовали за тысячи лет до этого. Специалисты относят время появления волшебной сказки к эпохе разложения первобытно-общинного строя, когда основным источником пропитания стала не охота, а земледелие.

В волшебных сказках Василиса Премудрая или Прекрасная — лишь одно из имен невесты героя, которую могут звать и по-другому: Елена Прекрасная, Марья-царевна, Царь-девица, Настасья-королевишна, Варвара-краса и так далее. Функция персонажа-невесты в русских сказках не зависит от имени. Например, в известном собрании сказок Александра Афанасьева встречаются разные сюжеты и роли, связанные с именем Василисы. Главная героиня «Василисы Прекрасной» вовсе не царевна, а бедная падчерица, которую отправляют за огнем в избушку Бабы-яги. В сказке «Жар-птица и Василиса-царевна» Василису ловит стрелец-молодец по поручению царя. Царевна на первый взгляд желает своему похитителю смерти: «Не пойду, — говорит царю, — за тебя замуж, пока не велишь ты стрельцу-молодцу в горячей воде искупаться». Волшебный конь стрельца заговаривает воду, и герой выходит из котла краше прежнего. В финале, как и положено в волшебной сказке, старый царь погибает, по примеру стрельца искупавшись в кипятке, а главный герой получает жену и царство в придачу. В сюжете «Морской царь и Василиса Премудрая» Василиса — дочь Водяного, помощница героя-царевича. В разных вариантах известной сказки «Царевна-лягушка» главную героиню зовут то Еленой Прекрасной, то Василисой Премудрой, что подтверждает: имя героини не столь важно — важна лишь функция.

Филолог-фольклорист Владимир Пропп доказал, что жанр волшебной сказки уходит корнями в эпоху первобытной общины, когда мужчины проходили «магические» обряды и получали специальные силы, власть над животным миром, чтобы охотиться успешней. Прохождение обряда было своего рода путешествием в потусторонний мир, где мужчина подвергался жестоким испытаниям: ему могли отрезать пальцы, его могли пытать огнем — и так далее. Позже, когда охотничье общество сменилось земледельческим, эти традиции постепенно ушли из жизни, но их завуалированные описания остались в сказках.

Именно поэтому во многих сказках Василиса испытывает потенциального жениха самыми странными и даже пугающими способами вроде прыжка в котел с кипятком: такие сюжеты — отзвук времен древнейшего матриархата, когда женщина была «держательницей рода и тотемической магии».

Имя Василиса, означающее в переводе с греческого «жена царя» или «царица», попало на Русь из Византии не позднее XIII века. В Повести временных лет, датированной началом XII столетия, это имя не упоминалось ни разу. А первыми известными Василисами были дочь ростовского князя Василиса Дмитриевна, жившая на рубеже XIII–XIV веков, а также еще одна ростовская княжна — Василиса Константиновна, которая жила в XIV веке.

Вероятно, в русские сказки это имя пришло уже после того, как прочно закрепилось в обиходе. Но сама героиня и сюжеты с ее участием существовали за тысячи лет до этого. Специалисты относят время появления волшебной сказки к эпохе разложения первобытно-общинного строя, когда основным источником пропитания стала не охота, а земледелие.

В волшебных сказках Василиса Премудрая или Прекрасная — лишь одно из имен невесты героя, которую могут звать и по-другому: Елена Прекрасная, Марья-царевна, Царь-девица, Настасья-королевишна, Варвара-краса и так далее. Функция персонажа-невесты в русских сказках не зависит от имени. Например, в известном собрании сказок Александра Афанасьева встречаются разные сюжеты и роли, связанные с именем Василисы. Главная героиня «Василисы Прекрасной» вовсе не царевна, а бедная падчерица, которую отправляют за огнем в избушку Бабы-яги. В сказке «Жар-птица и Василиса-царевна» Василису ловит стрелец-молодец по поручению царя. Царевна на первый взгляд желает своему похитителю смерти: «Не пойду, — говорит царю, — за тебя замуж, пока не велишь ты стрельцу-молодцу в горячей воде искупаться». Волшебный конь стрельца заговаривает воду, и герой выходит из котла краше прежнего. В финале, как и положено в волшебной сказке, старый царь погибает, по примеру стрельца искупавшись в кипятке, а главный герой получает жену и царство в придачу. В сюжете «Морской царь и Василиса Премудрая» Василиса — дочь Водяного, помощница героя-царевича. В разных вариантах известной сказки «Царевна-лягушка» главную героиню зовут то Еленой Прекрасной, то Василисой Премудрой, что подтверждает: имя героини не столь важно — важна лишь функция.

Филолог-фольклорист Владимир Пропп доказал, что жанр волшебной сказки уходит корнями в эпоху первобытной общины, когда мужчины проходили «магические» обряды и получали специальные силы, власть над животным миром, чтобы охотиться успешней. Прохождение обряда было своего рода путешествием в потусторонний мир, где мужчина подвергался жестоким испытаниям: ему могли отрезать пальцы, его могли пытать огнем — и так далее. Позже, когда охотничье общество сменилось земледельческим, эти традиции постепенно ушли из жизни, но их завуалированные описания остались в сказках.

Именно поэтому во многих сказках Василиса испытывает потенциального жениха самыми странными и даже пугающими способами вроде прыжка в котел с кипятком: такие сюжеты — отзвук времен древнейшего матриархата, когда женщина была «держательницей рода и тотемической магии».

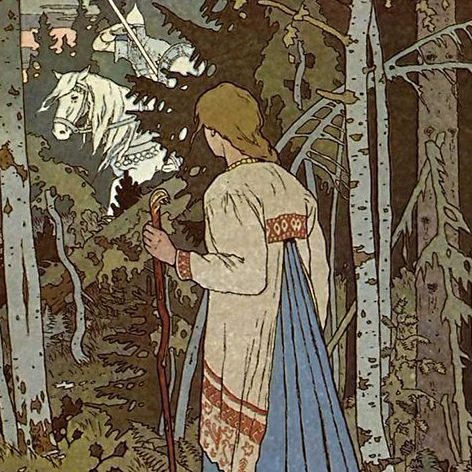

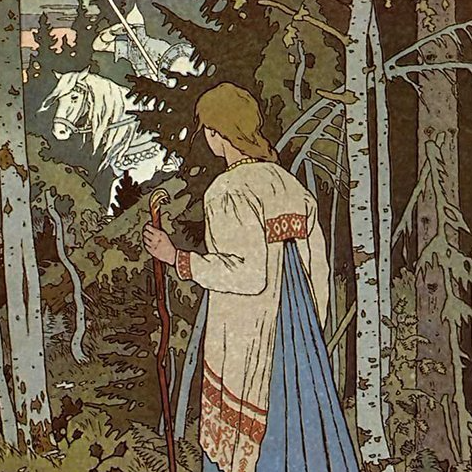

Иван Билибин. Василиса Прекрасная и белый всадник. Иллюстрация к сказке «Василиса Прекрасная». 1900

Частное собрание

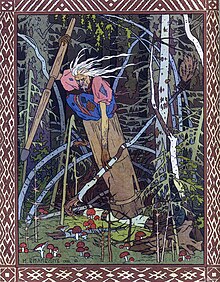

Иван Билибин. Василиса Прекрасная уходит из дома Бабы-яги. Иллюстрация к сказке «Василиса Прекрасная». 1899

Частное собрание

Кинуко Крафт. Василиса Прекрасная. Иллюстрация к сказке «Баба-яга и Василиса Прекрасная». 1994

Частное собрание

Анна Давыдова. Василиса Прекрасная. Иллюстрация к сказке «Василиса Прекрасная». 1948

Частное собрание

Виктор Васнецов. Царевна-лягушка. 1918

Дом-музей В.М. Васнецова, Москва

Николай Рерих. Добрые травы. Василиса Премудрая. 1941

Государственный музей искусства народов Востока, Москва

Валентина Сорогожская в роли Василисы Прекрасной

Кадр из сказки Александра Роу «Василиса Прекрасная» (1939)

Татьяна Аксюта в роли Василисы Прекрасной

Кадр из сказки Михаила Юзовского «Там, на неведомых дорожках…» (1982)