Ночной режим

Новинки

Пропавшая грамота

Красный цветок

Трусишка Вася (М. Зощенко)

Критики (В. Шукшин)

Отчего у верблюда горб (Р. Киплинг)

Стрижонок Скрип

Популярное

Сказка Гулливер в стране лилипутов — Джонатан Свифт

Сказка Чудесное путешествие Нильса с дикими гусями — Сельма Лагерлеф

Сказки про драконов

Миф о рождении Зевса

Домовёнок Кузя — Татьяна Александрова

Сказки про кошек

Сказки для детей любого возраста →

Сказки про Кощея Бессмертного

Сказки про Кощея Бессмертного

Иван Соснович

Пеппи Длинный чулок

Один из могущественных персонажей эпоса всех времен является Кощей Бессмертный, сказки про которого отличаются атмосферой, магией и его всесилием. Мы собрали в отличную подборку интересные сказки про Кощея, которые познакомят вашего ребенка с данным персонажем и его силами.

- Сказка Про славного царя Гороха;

- Сказка о царе Берендее, о сыне его Иване-царевиче, о хитростях Кощея Бессмертного и о премудрости Марьи-царевны, Кощеевой дочери;

- Царевна-лягушка;

- Марья Моревна;

- Руслан и Людмила;

- Иван Утреник;

- Булат-молодец;

- Сказка про чудную игру;

- Кощей-Бессмертный;

- Царевна-змея;

- День рождения Кощея;

- Иван Соснович.

Facebook

ВКонтакте

Комментарии

Рпапм

Абвнвочтвьяьчьвьчьвьчьвовововововововововрврврврврврвововоаалалал

10.10.2022

Ответить

Ночной режим

Категории

Аудиосказки для детей слушать онлайн

— Арабские аудиосказки

— Аудио повести для детей и подростков

— Аудио рассказы Виталия Бианки

— Аудиокниги Андрея Платонова

— Аудиокниги Аркадия Гайдара

— Аудиокниги Бориса Житкова

— Аудиокниги Драгунского

— Аудиокниги Марка Твена

— Аудиокниги Пришвина для детей

— Аудиосказки Аксакова

— Аудиосказки Александра Волкова

— Аудиосказки Андерсена

— Аудиосказки Андрея Усачева

— Аудиосказки Астрид Линдгрен

— Аудиосказки Бажова

— Аудиосказки братьев Гримм

— Аудиосказки Владимира Сутеева

— Аудиосказки Гаршина

— Аудиосказки Гауфа

— Аудиосказки Гофмана

— Аудиосказки Джанни Родари

— Аудиосказки Киплинга

— Аудиосказки Мамина-Сибиряка

— Аудиосказки Маршака

— Аудиосказки Михалкова

— Аудиосказки на ночь

— Аудиосказки Одоевского

— Аудиосказки Остера

— Аудиосказки по мультфильмам

— Аудиосказки Пушкина

— Аудиосказки Салтыкова-Щедрина

— Аудиосказки Толстого

— Аудиосказки Успенского

— Аудиосказки Чуковского

— Аудиосказки Шарля Перро

— Аудиосказки Шварца

— Аудиосказки Юрия Дружкова и Валентина Постникова

— Детская Библия

— Русские народные

— Сборник аудиосказок

— Советские аудиосказки

Басни для детей

— Басни Крылова

— Басни Лафонтена

— Басни Михалкова

— Басни Толстого

— Басни Эзопа

Блог

Диафильмы

Загадки для детей

— Загадки для родителей

— Сборник загадок

Мифы

— Мифы Древнего Китая

— Мифы Древнего Рима

— Мифы Древней Греции

— Мифы Древней Руси

— Мифы и легенды Индии

— Скандинавские мифы

Песни для детей

— Детские песни из мультфильмов

— Звуки природы для детей

— Колыбельные для малышей

— Музыка Моцарта для детей

— Песни для малышей

— Песни про маму

Поделки для детей

Пословицы и поговорки

Раскраски для детей

— Вокруг света

— Времена года

— Развивающие раскраски

— Раскраски Винкс

— Раскраски для взрослых

— Раскраски для девочек

— Раскраски для малышей

— Раскраски для мальчишек

— Раскраски животных

— Раскраски игр и игрушек

— Раскраски из мультфильмов

— Раскраски к праздникам

Сказки для детей любого возраста

— Анализ произведений

— Арабские сказки

— Денискины рассказы Драгунского

— Краткие содержания

— Повести для детей и подростков

— Рассказы Бориса Житкова

— Рассказы Виталия Бианки

— Рассказы Гайдара

— Рассказы Зощенко

— Рассказы Николая Носова

— Рассказы Платонова

— Рассказы Пришвина для детей

— Романы Марка Твена

— Русские народные сказки

— Сказки Аксакова

— Сказки Александра Волкова

— Сказки Алексея Николаевича Толстого

— Сказки Андерсена

— Сказки Андрея Усачева

— Сказки Астрид Линдгрен

— Сказки Бажова

— Сказки братьев Гримм

— Сказки Вильгельма Гауфа

— Сказки Владимира Сутеева

— Сказки Гаршина

— Сказки Гофмана

— Сказки Джанни Родари

— Сказки Евгения Шварца

— Сказки Киплинга

— Сказки Льва Николаевича Толстого

— Сказки Мамин-Сибиряк

— Сказки Маршака

— Сказки народов мира

— Сказки Одоевского

— Сказки Остера

— Сказки Пушкина

— Сказки Салтыкова-Щедрина

— Сказки Чуковского

— Сказки Шарля Перро

— Советские сказки

Стихи для детей

— Анализ стихотворений

— Детские стихи для заучивания

— Сказки в стихах

— Стихи Агнии Барто

— Стихи Берестова для детей

— Стихи Бориса Заходера

— Стихи Бунина

— Стихи Генриха Сапгира

— Стихи для детей 1, 2, 3 лет

— Стихи для детей 10, 11 лет и старше

— Стихи для детей 4, 5, 6 лет

— Стихи для детей 7, 8, 9 лет

— Стихи Елены Благининой для детей

— Стихи Есенина для детей

— Стихи Мандельштама

— Стихи Маршака

— Стихи Маяковского

— Стихи Мецгера

— Стихи Михалкова

— Стихи о девочках

— Стихи о мальчиках

— Стихи про быка

— Стихи про пословицы

— Стихи Пушкина

— Стихи Сурикова для детей

— Стихи Татьяны Гусаровой

— Стихи Успенского для детей

— Стихи Хармса

Мы используем файлы cookies для улучшения работы сайта. Оставаясь на нашем сайте, вы соглашаетесь с условиями использования файлов cookies.

Мы используем файлы cookies для улучшения работы сайта. Оставаясь на нашем сайте, вы соглашаетесь с условиями использования файлов cookies.

Рубрика «Сказки про Кощея Бессмертного»

Самый главный злодей множества сказок, страшный и коварный Кощей Бессмертный часто пугает детей. Но зато как приятно, дослушав сказку до конца, узнавать, что и на такого сильного злодея найдется управа! Переживание чувства страха в некоторой мере полезно для ребенка, переживая его при чтении сказок он становится более подготовлен к реальным неприятным ситуациям. Безусловно, увлекаться страшными историями не стоит, но и полностью отказываться от них психологи не советуют. Тем более, что в сказке добро обязательно победит зло!

Булат-молодец4.4 (7)

Жил-был царь, у него был один сын. Когда царевич был мал, то мамки и няньки его прибаюкивали: — Баю-баю, Иван-царевич! Вырастешь большой, найдешь себе невесту: за тридевять земель, в тридесятом государстве сидит в башне Василиса. Минуло царевичу пятнадцать лет, стал у отца проситься поехать поискать свою невесту. — Куда ты поедешь? Ты еще слишком мал! …

Читать далее

Марья Моревна5 (1)

В некотором царстве, в некотором государстве жил-был Иван-царевич; у него было три сестры: одна Марья-царевна, другая Ольга-царевна, третья — Анна-царевна. Отец и мать у них померли; умирая, они сыну наказывали: — Кто первый за твоих сестер станет свататься, за того и отдавай — при себе не держи долго! Царевич похоронил родителей и с горя пошел …

Читать далее

Царевна-лягушка5 (2)

В старые годы у одного царя было три сына. Вот, когда сыновья стали на возрасте, царь собрал их и говорит: — Сынки, мои любезные, покуда я ещё не стар, мне охота бы вас женить, посмотреть на ваших деточек, на моих внучат. Сыновья отцу отвечают: — Так что ж, батюшка, благослови. На ком тебе желательно нас …

Читать далее

Кощей-Бессмертный4 (6)

В некотором царстве, в некотором государстве жил-был царь; у этого царя было три сына, все они были на возрасте. Только мать их вдруг унёс Кощей Бессмертный. Старший сын и просит у отца благословенье искать мать. Отец благословил; он уехал и без вести пропал. Средний сын пождал-пождал, тоже выпросился у отца, уехал, — и этот без …

Читать далее

Koschei (Russian: Коще́й, tr. Koshchey, IPA: [kɐˈɕːej]), often given the epithet «the Immortal«, or «the Deathless» (Russian: Коще́й Бессме́ртный), is an archetypal male antagonist in Russian folklore.

The most common feature of tales involving Koschei is a spell which prevents him from being killed. He hides his soul inside nested objects to protect it. For example, the soul (or in the tales, it is usually called «death») may be hidden in a needle that is hidden inside an egg, the egg is in a duck, the duck is in a hare, the hare is in a chest, the chest is buried or chained up on a far island. Usually he takes the role of a malevolent rival father figure, who competes for (or entraps) a male hero’s love interest.

The origin of the tales is unknown. The archetype may contain elements derived from the 12th-century pagan Cuman-Kipchak (Polovtsian) leader Khan Konchak, who is recorded in The Tale of Igor’s Campaign; over time a balanced view of the non-Christian Cuman Khan may have been distorted or caricatured by Christian Slavic writers.

Historicity and folk origins[edit]

By at least the 18th century, and likely earlier, Koschei’s legend had been appearing in Slavic tales.[1] For a long period no connection was made with any historical character.[2]

Origin in Khan Konchak[edit]

The origin of the tale may be related to the Polovtsian (Cuman) leader Khan Konchak, who dates from the 12th century.[n 1] In The Tale of Igor’s Campaign Konchak is referred to as a koshey (slave).[n 2][3] Konchak is thought to have come/returned from Georgia (the Caucasus) to the steppe c.1126–1130; by c.1172 he is described in Kievan Rus’ chronicles as a leader of the Polovtsi, and as taking part in an uprising. There is not enough information to reconstruct further details of Konchak’s appearance or nature from historical sources; though unusual features or abnormalities were usually recorded (often as epithets) by chroniclers, none are recorded for Konchak.[4]

The legendary love of gold of Koschei is speculated to be a distorted record of Konchak’s role as the keeper of the Kosh’s resources.[5]

Koschei’s epithet «the immortal» may be a reference to Konchak’s longevity. He is last recorded in Russian chronicles during the 1203 capture of Kiev, if the record is correct this gives Konchak an unusually long life – possibly over 100 years – for the time this would have been over six generations.[6]

Koschei’s life-protecting spell may be derived from traditional Turkic amulets, not only were these egg-shaped, but they would often contain arrowheads (cf. the needle in Koschei’s egg).[7]

It is thought that many of the negative aspects of Koschei’s character are distortions of a more nuanced relationship of Khan Konchak with the Christian Slavs, such as his rescuing of Prince Igor from captivity, or the marriage between Igor’s son and Konchak’s daughter. Konchak, as a pagan, could have been demonised over time as a stereotypical villain.[8]

Naming and etymology[edit]

In the dictionary of V. I. Dal, the name Kashchei is derived from the verb «cast» — to harm, to dirty: «probably from the word to cast, but remade into koshchei, from bone, meaning a man exhausted by excessive thinness». Vasmer notes that the word koshchei has two meanings that have different etymologies: «thin, skinny person, walking skeleton» or «miser» — the origin of the word «bone». Old Russian «youth, boy, captive, slave» from the Turkic košči «slave», in turn from koš «camp, parking lot».

Koschei, as the name of the hero of a fairy tale and as a designation for a skinny person, Max Vasmer in his dictionary considers the original Slavic word (homonym) and associates with the word bone (common Slavic * kostь), that is, it is an adjective form koštіі (nominative adjective in the nominative case singular), declining according to the type «God».

Numerous variant names and spellings have been given to Koschei – these include Kashchei, Koshchai, Kashshei, Kovshei, Kosh, Kashch, Kashel, Kostei, Kostsei, Kashshui, Kozel, Koz’olok, Korachun, Korchun bessmertnyi, Kot bezsmertnyi, Kot Bezmertnyi, Kostii bezdushnyi; in bylinas he also appears as Koshcheiushko, Koshcheg, Koshcherishcho, Koshchui, Koshel.[9] Kachtcheï is the standard French transliteration.

The term Koshey appears in Slavic chronicles as early as the 12th century to refer to an officer or official during a military campaign. Similar terms include the Ukrainian Кошовий (Koshovyi) for the head of the ‘Kish’ (military)[10] (see also Kish otaman.) In Old Russian ‘Kosh’ means a camp, while in Belarusian a similar term means ‘to camp’ and in Turkic languages a similar term means ‘a wanderer’.[11] The use as a personal name is recorded as early as the 15th century on Novogrodian birch bark manuscripts.[12]

In The Tale of Igor’s Campaign a similar sounding term is used, recorded being inscribed on coins, deriving from the Turkic for ‘captive’ or ‘slave’. The same term also appears in the Ipatiev Chronicle, meaning ‘captive’.[13] A second mention of the term is made in The Tale of Igor’s Campaign when Igor is captured by the Polovtsi; this event is recorded as a riddle: «And here Prince Igor exchanged his golden saddle of a prince for the saddle of a Koshey (slave).»[14]

Nikolai Novikov also suggested the etymological origin of koshchii meaning «youth» or «boy» or «captive», «slave», or «servant». The interpretation of «captive» is interesting because Koschei appears initially as a captive in some tales.[12]

In folk tales[edit]

Koschei is a common antihero in east-Slavic folk tales. Often tales involving him are of the type AT 302 «The Giant Without A Heart» (see Aarne–Thompson classification systems); and he also appears in tales resembling type AT 313 «The Magic Flight».[15]

He usually functions as the antagonist or rival to a hero.[16] Love rivalry and related themes are common.[17]

The typical feature of tales concerning Koschei is his protection against being killed (AT 302) – to do so he has hidden his soul inside an egg, and further nested the egg inside various animals, and then in protective containers and places.[18]

In other tales, Koschei can cast a sleep spell that can be broken by playing an enchanted gusli. Depending on the tale he has different characteristics: he may ride a three- or seven-legged horse; may have tusks or fangs; and may possess a variety of different magic objects (like cloaks and rings) that a hero is sent to obtain; or he may have other magic powers.[19] In one tale he has eyelids so heavy he requires servants to lift them[19] (cf. the Celtic Balor or Ysbaddaden, or Serbian Vy).

Psychologically, Koschei can represent an initially benevolent, but later malevolent, father (to a bride) figure.[20] The parallel female figure, Baba Yaga, as a rule does not appear in the same tale with Koschei, though exceptions exists where both appear together as a married couple, or as siblings.[15] Sometimes, Baba Yaga, as an old woman figure appears in tales along with Koschei as his mother or aunt.[21]

«Marya Morevna»[edit]

In a tale also known as «The Death of Koschei the Deathless», Ivan Tsarevitch encounters Koschei chained in his wife’s (Marya Morevna’s) dungeon. He releases and revives Koschei, but Koschei abducts Marya. Ivan goes to rescue Marya several times, but Koschei’s swift horse allows him to easily catch up with the escaping lovers; each time the magical horse informs Koschei that he will be able to carry out several activities first and still be able to catch up. After the third unsuccessful escape, Koschei cuts up Ivan and throws his parts into the sea in a barrel. Ivan is revived with the aid of the water of life. He seeks Baba Yaga for a suitably swift horse. After trials he steals a horse and rescues Marya.[22]

«Tsarevich Petr and the Wizard»[edit]

Tsar Bel-Belianin’s wife the Tzaritza is abducted by Koschei (the wizard). The Tsar’s three sons attempt to rescue her. The first two fail to reach the wizard’s palace, but the third, Petr, succeeds. He reaches the Tzaritza, conceals himself, and learns how the wizard hides his life. Initially he lies, but the third time he reveals it is in an egg, in a duck, in a hare, that nests in a hollow log, that floats in a pond, found in a forest on the island of Bouyan. Petr seeks the egg, freeing animals along the way – on coming to Bouyan the freed animals help him catch the wizard’s creatures and obtain the egg. He returns to the wizard’s domain and kills him by squeezing the egg – every action on the egg is mirrored on the wizard’s body.[23]

«The Snake Princess»[edit]

In «The Snake Princess» (Russian «Царевна-змея»), Koschei turns a princess who does not want to marry him into a snake.

Ivan Sosnovich[edit]

Koschei hears of three beauties in a kingdom. He kills two and wounds a third, puts the kingdom to sleep (petrifies), and abducts the princesses. Ivan Sosnovich (Russian Иван Соснович) learns of Koschei’s weakness: an egg in a box hidden under a mountain, so he digs up the whole mountain, finds the egg box and smashes it, and rescues the princess.

He also appears as a miser in Pushkin’s Ruslan and Ludmila, though this interpretation does not reflect previous folk tale representations.[12]

[edit]

The Serbian Baš Čelik (Head of Steel); Hungarian ‘Lead-Headed Monk’; and Slovak ‘Iron Monk’ also all hide their weakness inside a series of nested animals.[12]

In popular culture[edit]

Film[edit]

- Kashchey the Immortal, Russian Кащей Бессмертный, 1945 B&W fantasy directed by Alexander Rou, with Georgy Millyar as Koschei.

- Fire, Water, and Brass Pipes, Russian Огонь, вода и… медные трубы, Ogon, 1968 fantasy directed by Alexander Rou, with Georgy Millyar as Koschei.

- Beloved Beauty, Russian Краса́ ненагля́дная, 1958 stop-animated film.

- Sitting on the golden porch (На златом крыльце сидели), 1986 fairy tale directed by Boris Rytsarev

Opera and ballet[edit]

- The villain in Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Firebird.

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov wrote an opera involving Koschei, titled Кащей бессмертный, or Kashchey the Deathless.

Derivative works[edit]

Film[edit]

- The Book of Masters, Russian Книга Мастеров, 2009 fantasy

- Lilac Ball, Russian Лиловый шар, 1987 science fiction

- After the Rain, on Thursday, Russian После дождичка в четверг, 1985 musical children’s fantasy

- Along Unknown Paths, Russian Там, на неведомых дорожках, 1982 children’s fantasy

- New Year Adventures of Masha and Vitya, Russian Новогодние приключения Маши и Вити, 1975 children’s film

Television[edit]

- In Little Einsteins, Koschei is a nesting doll named Katschai tried to steal the music power from the magical Firebird. Katschai used animal nesting dolls to try and stop the Little Einsteins team from getting to the Firebird which Katschai had locked up at the top of a building in Russia.

- In the US television series «Grimm», in episode 9 of season 3, Koschei is the main guest character. (see Red Menace (Grimm))

Novels and comics[edit]

- In Sarah J Maas’s A Court of Silver Flames, Koschei the Deathless is the name given to an ancient being trapped by a spell in a lake and is believed to be a death god like his siblings mentioned in the previous books.

- In Jessica Rubinkowski’s The Bright and The Pale, the Pale God is named Koschei.

- In James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice, and in Robert A Heinlein’s retelling of the story Job: a Comedy of Justice, Koshchei the Deathless appears as the most supreme being who made things as they are and is therefore universally unappreciated before Jurgen’s kind words are spoken.

- In Alexander Veltman’s Koshchei bessmertny: Bylina starogo vremeni (Koshchei the Immortal: A Bylina of Old Times, 1833), a parody of historical adventure novels, the hero, Iva Olelkovich, imagines that his bride has been captured by Koschei.

- Mercedes Lackey’s novel of Stravinsky’s Firebird features Katschei as the main villain, retelling the classic tale for a modern audience.

- Catherynne Valente’s novel Deathless is a retelling of the Koschei story set against a backdrop of 20th-century Russian history.[24]

- In the 1965 science-fiction Monday Begins on Saturday by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, he is one of the creatures held in the NIIChaVo institute.

- Koschei appears as a character in John C. Wright’s «War of the Dreaming» novels. He offers to save the hero’s wife, if the hero will agree to take the life of a stranger.

- Koschei appears as a slave to Baba Yaga in the Hellboy comic book series, first appearing in Hellboy: Darkness Calls. Koschei’s origin story is later revealed in backup stories to single issues of Hellboy: The Wild Hunt. The story is also collected in Hellboy: Weird Tales and expanded upon in Koshchei the Deathless.

- Koschei also appears in DC Comics The Sandman: Fables and Reflections.

- In the webcomic PS238 by Aaron Williams, the child hero 84 is currently trapped in Koschei’s egg, trying to find the «eye», and in doing so, will become his new Champion of Earth to battle from now on.

- Koschei is the primary antagonist in Marina Frants’ short fiction piece «Death Becomes Him», the sequel to «A Bone to Pick».

- Katherine Arden’s novel, The Girl in the Tower, features Kaschei as the main antagonist. It is the second book in the Winternight trilogy, which is inspired by various Russian folktales.

- In Alix E. Harrow‘s novel, The Once and Future Witches, Koschei the Deathless appears as a wicked witch in an old Russian witch tale.

Games[edit]

- In the fantasy tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, he is the inspiration for the demon lord Kostchtchie, published 1983 in Monster Manual II.

- Koschei appears as a character in the MMORPG RuneScape, under the name «Koschei the Deathless».

- In the video game series The Incredible Adventures of Van Helsing, the Death of Koschei is a key plot item in the second game. In the third game, recurring supporting character Prisoner Seven is revealed to be Koschei the Deathless, and becomes the main antagonist.

- In the videogame Shadowrun: Hong Kong, the supporting character Racter has a drone named ‘Koschei’, which later in the game can gain an upgrade named «Deathless» that makes the drone unkillable.

- In the computer game Dominions 4: Thrones of Ascension, Koschei appears as a hero character for Bogarus, a faction inspired by medieval Russia and Slavic mythology.

- The legend of Koschei the Deathless serves as an inspiration for the narrative of Rise of the Tomb Raider.[25]

- In the digital card game Mythgard, «Koschei, the Deathless» appears as a mythic minion in the Dreni faction.

- In the videogame Arknights, the duke of Ursus (a fictional country based on Russia) is named Koschei, and is hinted to possess the main antagonist after being killed by them.

- Koschei is a playable piece in Mantic Games’ Hellboy: The Board Game.

- In the MMORPG Tibia (video game), there is a Lich boss named «Koshei The Deathless» who hides his soul in 4 pieces of an amulet that are scattered around the gameworld.

See also[edit]

- Erlik, Chernobog – gods of the underworld in Turkic and Slavic myth respectively

- Lich

Notes[edit]

- ^ Konchak is an important antagonist in the Tale of Igor’s Campaign

- ^ In Leonard A. Magnus’s translation : «Shoot, my liege, the heathen Konctik the slave»

References[edit]

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 5:10-.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 1. A dossier of the fairy villain. 2:05–2:20.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 7:40–8:00.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 3. Konchuk’s personal file 7:58–11:00.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 3. Konchuk’s personal file 11:00–12:30.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 3. Konchuk’s personal file 12:20–13:15.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 3. Konchuk’s personal file 13:10–13:40.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 4. Say a word about the poor Koshey 13:40–15:02.

- ^ Johns 2004, Note 1, p.230.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 5:10–5:50.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 5:50–6:10.

- ^ a b c d Johns 2004, p. 233.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 6:05–6:58.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 6:50–7:20.

- ^ a b Johns 2004, p. 230.

- ^ Johns 2004, pp. 231–2.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 232.

- ^ Johns 2004, pp. 230–1.

- ^ a b Johns 2004, p. 231.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 141.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija; Miriam Robbins Dexter (1999). The Living Goddesses. University of California Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-520-22915-0.

- ^ Lang, Andrew, ed. (1890), «The Death of Koschei the Deathless», The Red Fairy Book

- ^ Wheeler, Post, ed. (1917), «Tzarevich Petr and the Wizard», Russian wonder tales, pp. 309-

- ^ Heller, Jason (7 Apr 2011). «Catherynne M. Valente: Deathless». www.avclub.com.

- ^ Corrie, Alexa Ray (August 4, 2015). «Rise of the Tomb Raider’s Myths Explained». GameSpot. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

Sources[edit]

- «Turkic roots of Koshey The Immortal», Reflections on History (documentary), Kazakh TV, no. 5, 4 Apr 2018

- Johns, Andreas (2004), Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale, Peter Lang

Further reading[edit]

- Johns, Andreas. 2000. “The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore”. In: FOLKLORICA – Journal of the Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Folklore Association 5 (1): 7–24. https://doi.org/10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

External links[edit]

Media related to Koschei at Wikimedia Commons

Koschei (Russian: Коще́й, tr. Koshchey, IPA: [kɐˈɕːej]), often given the epithet «the Immortal«, or «the Deathless» (Russian: Коще́й Бессме́ртный), is an archetypal male antagonist in Russian folklore.

The most common feature of tales involving Koschei is a spell which prevents him from being killed. He hides his soul inside nested objects to protect it. For example, the soul (or in the tales, it is usually called «death») may be hidden in a needle that is hidden inside an egg, the egg is in a duck, the duck is in a hare, the hare is in a chest, the chest is buried or chained up on a far island. Usually he takes the role of a malevolent rival father figure, who competes for (or entraps) a male hero’s love interest.

The origin of the tales is unknown. The archetype may contain elements derived from the 12th-century pagan Cuman-Kipchak (Polovtsian) leader Khan Konchak, who is recorded in The Tale of Igor’s Campaign; over time a balanced view of the non-Christian Cuman Khan may have been distorted or caricatured by Christian Slavic writers.

Historicity and folk origins[edit]

By at least the 18th century, and likely earlier, Koschei’s legend had been appearing in Slavic tales.[1] For a long period no connection was made with any historical character.[2]

Origin in Khan Konchak[edit]

The origin of the tale may be related to the Polovtsian (Cuman) leader Khan Konchak, who dates from the 12th century.[n 1] In The Tale of Igor’s Campaign Konchak is referred to as a koshey (slave).[n 2][3] Konchak is thought to have come/returned from Georgia (the Caucasus) to the steppe c.1126–1130; by c.1172 he is described in Kievan Rus’ chronicles as a leader of the Polovtsi, and as taking part in an uprising. There is not enough information to reconstruct further details of Konchak’s appearance or nature from historical sources; though unusual features or abnormalities were usually recorded (often as epithets) by chroniclers, none are recorded for Konchak.[4]

The legendary love of gold of Koschei is speculated to be a distorted record of Konchak’s role as the keeper of the Kosh’s resources.[5]

Koschei’s epithet «the immortal» may be a reference to Konchak’s longevity. He is last recorded in Russian chronicles during the 1203 capture of Kiev, if the record is correct this gives Konchak an unusually long life – possibly over 100 years – for the time this would have been over six generations.[6]

Koschei’s life-protecting spell may be derived from traditional Turkic amulets, not only were these egg-shaped, but they would often contain arrowheads (cf. the needle in Koschei’s egg).[7]

It is thought that many of the negative aspects of Koschei’s character are distortions of a more nuanced relationship of Khan Konchak with the Christian Slavs, such as his rescuing of Prince Igor from captivity, or the marriage between Igor’s son and Konchak’s daughter. Konchak, as a pagan, could have been demonised over time as a stereotypical villain.[8]

Naming and etymology[edit]

In the dictionary of V. I. Dal, the name Kashchei is derived from the verb «cast» — to harm, to dirty: «probably from the word to cast, but remade into koshchei, from bone, meaning a man exhausted by excessive thinness». Vasmer notes that the word koshchei has two meanings that have different etymologies: «thin, skinny person, walking skeleton» or «miser» — the origin of the word «bone». Old Russian «youth, boy, captive, slave» from the Turkic košči «slave», in turn from koš «camp, parking lot».

Koschei, as the name of the hero of a fairy tale and as a designation for a skinny person, Max Vasmer in his dictionary considers the original Slavic word (homonym) and associates with the word bone (common Slavic * kostь), that is, it is an adjective form koštіі (nominative adjective in the nominative case singular), declining according to the type «God».

Numerous variant names and spellings have been given to Koschei – these include Kashchei, Koshchai, Kashshei, Kovshei, Kosh, Kashch, Kashel, Kostei, Kostsei, Kashshui, Kozel, Koz’olok, Korachun, Korchun bessmertnyi, Kot bezsmertnyi, Kot Bezmertnyi, Kostii bezdushnyi; in bylinas he also appears as Koshcheiushko, Koshcheg, Koshcherishcho, Koshchui, Koshel.[9] Kachtcheï is the standard French transliteration.

The term Koshey appears in Slavic chronicles as early as the 12th century to refer to an officer or official during a military campaign. Similar terms include the Ukrainian Кошовий (Koshovyi) for the head of the ‘Kish’ (military)[10] (see also Kish otaman.) In Old Russian ‘Kosh’ means a camp, while in Belarusian a similar term means ‘to camp’ and in Turkic languages a similar term means ‘a wanderer’.[11] The use as a personal name is recorded as early as the 15th century on Novogrodian birch bark manuscripts.[12]

In The Tale of Igor’s Campaign a similar sounding term is used, recorded being inscribed on coins, deriving from the Turkic for ‘captive’ or ‘slave’. The same term also appears in the Ipatiev Chronicle, meaning ‘captive’.[13] A second mention of the term is made in The Tale of Igor’s Campaign when Igor is captured by the Polovtsi; this event is recorded as a riddle: «And here Prince Igor exchanged his golden saddle of a prince for the saddle of a Koshey (slave).»[14]

Nikolai Novikov also suggested the etymological origin of koshchii meaning «youth» or «boy» or «captive», «slave», or «servant». The interpretation of «captive» is interesting because Koschei appears initially as a captive in some tales.[12]

In folk tales[edit]

Koschei is a common antihero in east-Slavic folk tales. Often tales involving him are of the type AT 302 «The Giant Without A Heart» (see Aarne–Thompson classification systems); and he also appears in tales resembling type AT 313 «The Magic Flight».[15]

He usually functions as the antagonist or rival to a hero.[16] Love rivalry and related themes are common.[17]

The typical feature of tales concerning Koschei is his protection against being killed (AT 302) – to do so he has hidden his soul inside an egg, and further nested the egg inside various animals, and then in protective containers and places.[18]

In other tales, Koschei can cast a sleep spell that can be broken by playing an enchanted gusli. Depending on the tale he has different characteristics: he may ride a three- or seven-legged horse; may have tusks or fangs; and may possess a variety of different magic objects (like cloaks and rings) that a hero is sent to obtain; or he may have other magic powers.[19] In one tale he has eyelids so heavy he requires servants to lift them[19] (cf. the Celtic Balor or Ysbaddaden, or Serbian Vy).

Psychologically, Koschei can represent an initially benevolent, but later malevolent, father (to a bride) figure.[20] The parallel female figure, Baba Yaga, as a rule does not appear in the same tale with Koschei, though exceptions exists where both appear together as a married couple, or as siblings.[15] Sometimes, Baba Yaga, as an old woman figure appears in tales along with Koschei as his mother or aunt.[21]

«Marya Morevna»[edit]

In a tale also known as «The Death of Koschei the Deathless», Ivan Tsarevitch encounters Koschei chained in his wife’s (Marya Morevna’s) dungeon. He releases and revives Koschei, but Koschei abducts Marya. Ivan goes to rescue Marya several times, but Koschei’s swift horse allows him to easily catch up with the escaping lovers; each time the magical horse informs Koschei that he will be able to carry out several activities first and still be able to catch up. After the third unsuccessful escape, Koschei cuts up Ivan and throws his parts into the sea in a barrel. Ivan is revived with the aid of the water of life. He seeks Baba Yaga for a suitably swift horse. After trials he steals a horse and rescues Marya.[22]

«Tsarevich Petr and the Wizard»[edit]

Tsar Bel-Belianin’s wife the Tzaritza is abducted by Koschei (the wizard). The Tsar’s three sons attempt to rescue her. The first two fail to reach the wizard’s palace, but the third, Petr, succeeds. He reaches the Tzaritza, conceals himself, and learns how the wizard hides his life. Initially he lies, but the third time he reveals it is in an egg, in a duck, in a hare, that nests in a hollow log, that floats in a pond, found in a forest on the island of Bouyan. Petr seeks the egg, freeing animals along the way – on coming to Bouyan the freed animals help him catch the wizard’s creatures and obtain the egg. He returns to the wizard’s domain and kills him by squeezing the egg – every action on the egg is mirrored on the wizard’s body.[23]

«The Snake Princess»[edit]

In «The Snake Princess» (Russian «Царевна-змея»), Koschei turns a princess who does not want to marry him into a snake.

Ivan Sosnovich[edit]

Koschei hears of three beauties in a kingdom. He kills two and wounds a third, puts the kingdom to sleep (petrifies), and abducts the princesses. Ivan Sosnovich (Russian Иван Соснович) learns of Koschei’s weakness: an egg in a box hidden under a mountain, so he digs up the whole mountain, finds the egg box and smashes it, and rescues the princess.

He also appears as a miser in Pushkin’s Ruslan and Ludmila, though this interpretation does not reflect previous folk tale representations.[12]

[edit]

The Serbian Baš Čelik (Head of Steel); Hungarian ‘Lead-Headed Monk’; and Slovak ‘Iron Monk’ also all hide their weakness inside a series of nested animals.[12]

In popular culture[edit]

Film[edit]

- Kashchey the Immortal, Russian Кащей Бессмертный, 1945 B&W fantasy directed by Alexander Rou, with Georgy Millyar as Koschei.

- Fire, Water, and Brass Pipes, Russian Огонь, вода и… медные трубы, Ogon, 1968 fantasy directed by Alexander Rou, with Georgy Millyar as Koschei.

- Beloved Beauty, Russian Краса́ ненагля́дная, 1958 stop-animated film.

- Sitting on the golden porch (На златом крыльце сидели), 1986 fairy tale directed by Boris Rytsarev

Opera and ballet[edit]

- The villain in Igor Stravinsky’s ballet The Firebird.

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov wrote an opera involving Koschei, titled Кащей бессмертный, or Kashchey the Deathless.

Derivative works[edit]

Film[edit]

- The Book of Masters, Russian Книга Мастеров, 2009 fantasy

- Lilac Ball, Russian Лиловый шар, 1987 science fiction

- After the Rain, on Thursday, Russian После дождичка в четверг, 1985 musical children’s fantasy

- Along Unknown Paths, Russian Там, на неведомых дорожках, 1982 children’s fantasy

- New Year Adventures of Masha and Vitya, Russian Новогодние приключения Маши и Вити, 1975 children’s film

Television[edit]

- In Little Einsteins, Koschei is a nesting doll named Katschai tried to steal the music power from the magical Firebird. Katschai used animal nesting dolls to try and stop the Little Einsteins team from getting to the Firebird which Katschai had locked up at the top of a building in Russia.

- In the US television series «Grimm», in episode 9 of season 3, Koschei is the main guest character. (see Red Menace (Grimm))

Novels and comics[edit]

- In Sarah J Maas’s A Court of Silver Flames, Koschei the Deathless is the name given to an ancient being trapped by a spell in a lake and is believed to be a death god like his siblings mentioned in the previous books.

- In Jessica Rubinkowski’s The Bright and The Pale, the Pale God is named Koschei.

- In James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice, and in Robert A Heinlein’s retelling of the story Job: a Comedy of Justice, Koshchei the Deathless appears as the most supreme being who made things as they are and is therefore universally unappreciated before Jurgen’s kind words are spoken.

- In Alexander Veltman’s Koshchei bessmertny: Bylina starogo vremeni (Koshchei the Immortal: A Bylina of Old Times, 1833), a parody of historical adventure novels, the hero, Iva Olelkovich, imagines that his bride has been captured by Koschei.

- Mercedes Lackey’s novel of Stravinsky’s Firebird features Katschei as the main villain, retelling the classic tale for a modern audience.

- Catherynne Valente’s novel Deathless is a retelling of the Koschei story set against a backdrop of 20th-century Russian history.[24]

- In the 1965 science-fiction Monday Begins on Saturday by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, he is one of the creatures held in the NIIChaVo institute.

- Koschei appears as a character in John C. Wright’s «War of the Dreaming» novels. He offers to save the hero’s wife, if the hero will agree to take the life of a stranger.

- Koschei appears as a slave to Baba Yaga in the Hellboy comic book series, first appearing in Hellboy: Darkness Calls. Koschei’s origin story is later revealed in backup stories to single issues of Hellboy: The Wild Hunt. The story is also collected in Hellboy: Weird Tales and expanded upon in Koshchei the Deathless.

- Koschei also appears in DC Comics The Sandman: Fables and Reflections.

- In the webcomic PS238 by Aaron Williams, the child hero 84 is currently trapped in Koschei’s egg, trying to find the «eye», and in doing so, will become his new Champion of Earth to battle from now on.

- Koschei is the primary antagonist in Marina Frants’ short fiction piece «Death Becomes Him», the sequel to «A Bone to Pick».

- Katherine Arden’s novel, The Girl in the Tower, features Kaschei as the main antagonist. It is the second book in the Winternight trilogy, which is inspired by various Russian folktales.

- In Alix E. Harrow‘s novel, The Once and Future Witches, Koschei the Deathless appears as a wicked witch in an old Russian witch tale.

Games[edit]

- In the fantasy tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons, he is the inspiration for the demon lord Kostchtchie, published 1983 in Monster Manual II.

- Koschei appears as a character in the MMORPG RuneScape, under the name «Koschei the Deathless».

- In the video game series The Incredible Adventures of Van Helsing, the Death of Koschei is a key plot item in the second game. In the third game, recurring supporting character Prisoner Seven is revealed to be Koschei the Deathless, and becomes the main antagonist.

- In the videogame Shadowrun: Hong Kong, the supporting character Racter has a drone named ‘Koschei’, which later in the game can gain an upgrade named «Deathless» that makes the drone unkillable.

- In the computer game Dominions 4: Thrones of Ascension, Koschei appears as a hero character for Bogarus, a faction inspired by medieval Russia and Slavic mythology.

- The legend of Koschei the Deathless serves as an inspiration for the narrative of Rise of the Tomb Raider.[25]

- In the digital card game Mythgard, «Koschei, the Deathless» appears as a mythic minion in the Dreni faction.

- In the videogame Arknights, the duke of Ursus (a fictional country based on Russia) is named Koschei, and is hinted to possess the main antagonist after being killed by them.

- Koschei is a playable piece in Mantic Games’ Hellboy: The Board Game.

- In the MMORPG Tibia (video game), there is a Lich boss named «Koshei The Deathless» who hides his soul in 4 pieces of an amulet that are scattered around the gameworld.

See also[edit]

- Erlik, Chernobog – gods of the underworld in Turkic and Slavic myth respectively

- Lich

Notes[edit]

- ^ Konchak is an important antagonist in the Tale of Igor’s Campaign

- ^ In Leonard A. Magnus’s translation : «Shoot, my liege, the heathen Konctik the slave»

References[edit]

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 5:10-.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 1. A dossier of the fairy villain. 2:05–2:20.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 7:40–8:00.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 3. Konchuk’s personal file 7:58–11:00.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 3. Konchuk’s personal file 11:00–12:30.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 3. Konchuk’s personal file 12:20–13:15.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 3. Konchuk’s personal file 13:10–13:40.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 4. Say a word about the poor Koshey 13:40–15:02.

- ^ Johns 2004, Note 1, p.230.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 5:10–5:50.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 5:50–6:10.

- ^ a b c d Johns 2004, p. 233.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 6:05–6:58.

- ^ KazakhTV 2018, 2. Entertaining etymology. 6:50–7:20.

- ^ a b Johns 2004, p. 230.

- ^ Johns 2004, pp. 231–2.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 232.

- ^ Johns 2004, pp. 230–1.

- ^ a b Johns 2004, p. 231.

- ^ Johns 2004, p. 141.

- ^ Gimbutas, Marija; Miriam Robbins Dexter (1999). The Living Goddesses. University of California Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-520-22915-0.

- ^ Lang, Andrew, ed. (1890), «The Death of Koschei the Deathless», The Red Fairy Book

- ^ Wheeler, Post, ed. (1917), «Tzarevich Petr and the Wizard», Russian wonder tales, pp. 309-

- ^ Heller, Jason (7 Apr 2011). «Catherynne M. Valente: Deathless». www.avclub.com.

- ^ Corrie, Alexa Ray (August 4, 2015). «Rise of the Tomb Raider’s Myths Explained». GameSpot. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

Sources[edit]

- «Turkic roots of Koshey The Immortal», Reflections on History (documentary), Kazakh TV, no. 5, 4 Apr 2018

- Johns, Andreas (2004), Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale, Peter Lang

Further reading[edit]

- Johns, Andreas. 2000. “The Image of Koshchei Bessmertnyi in East Slavic Folklore”. In: FOLKLORICA – Journal of the Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Folklore Association 5 (1): 7–24. https://doi.org/10.17161/folklorica.v5i1.3647.

External links[edit]

Media related to Koschei at Wikimedia Commons

КАК В РУССКИХ СКАЗКАХ ВОЗНИК ОБРАЗ КОЩЕЯ БЕССМЕРТНОГО?

КАК В РУССКИХ СКАЗКАХ ВОЗНИК ОБРАЗ КОЩЕЯ БЕССМЕРТНОГО?

Традиционно злодей крадет девушку, чтобы жениться на ней.

В сказках встречаются два варианта имени этого популярного персонажа: Кащей и Кощей. По одной из версий, такое прозвище происходит от слова «кость». По другой — от слова «касть», родственного «пакости». Но большинство исследователей считает, что имя сказочного злодея восходит к слову с древнетюрскими корнями «кош» — «стан», «поселение».

В самых древних дошедших до нас текстах Кощея называют Кошем, то есть господином. А в «Слове о полку Игореве» «кощеями» называют пленников: «Ту Игорь князь высьдъ из сьдла злата, а в сьдло кощиево», то есть в седло рабское. Специалисты склоняются к тому, что изначально повелитель Тридесятого царства назывался Кошем — господином, а позднее стал Кощеем — тем, кто принадлежит Кошу, то есть рабом.

Некоторые сюжеты сохранили память о временах древнего матриархата. Например, в сказке «Марья Моревна» Иван-царевич впервые повстречал Кощея в плену у своей жены:

В сказках встречаются два варианта имени этого популярного персонажа: Кащей и Кощей. По одной из версий, такое прозвище происходит от слова «кость». По другой — от слова «касть», родственного «пакости». Но большинство исследователей считает, что имя сказочного злодея восходит к слову с древнетюрскими корнями «кош» — «стан», «поселение».

В самых древних дошедших до нас текстах Кощея называют Кошем, то есть господином. А в «Слове о полку Игореве» «кощеями» называют пленников: «Ту Игорь князь высьдъ из сьдла злата, а в сьдло кощиево», то есть в седло рабское. Специалисты склоняются к тому, что изначально повелитель Тридесятого царства назывался Кошем — господином, а позднее стал Кощеем — тем, кто принадлежит Кошу, то есть рабом.

Некоторые сюжеты сохранили память о временах древнего матриархата. Например, в сказке «Марья Моревна» Иван-царевич впервые повстречал Кощея в плену у своей жены:

“

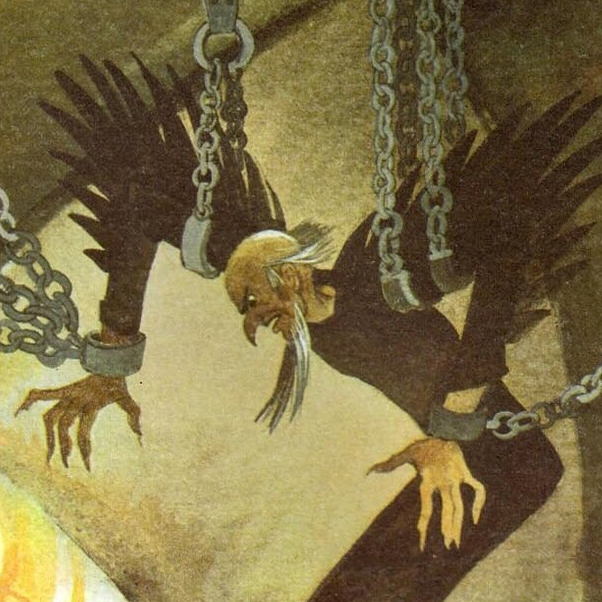

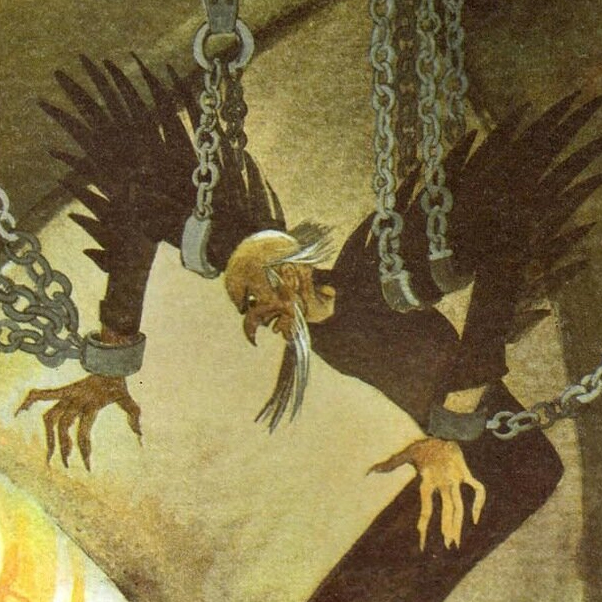

…глянул — а там висит Кощей Бессмертный, на двенадцати цепях прикован.

Просит Кощей у Ивана-царевича:

— Сжалься надо мной, дай мне напиться! Десять лет я здесь мучаюсь, не ел, не пил — совсем в горле пересохло!

<…> …а как выпил третье ведро — взял свою прежнюю силу, тряхнул цепями и сразу все двенадцать порвал.

— Спасибо, Иван-царевич! — сказал Кощей Бессмертный. — Теперь тебе никогда не видать Марьи Моревны, как ушей своих! — И страшным вихрем вылетел в окно, нагнал на дороге Марью Моревну, прекрасную королевну, подхватил ее и унес к себе.

Главная героиня Марья Моревна в сказке предстает могучей воительницей, а Ивану-царевичу помогают его родственники по женской линии — мужья сестер.

Однако чаще всего сказочный Кощей обитает в своем царстве — царстве мертвых. Традиционно злодей крадет девушку, чтобы жениться на ней. Объяснение этому сюжету дал советский фольклорист Владимир Пропп:

“

Умершим… приписывались два сильнейших инстинкта: голод и половой голод. Эти два вида голода иногда ассимилируются, как в русской сказке: «Схватил змей царевну и потащил ее к себе в берлогу, а есть ее не стал; красавица была, так за жену себе взял» <…> Божество избирает себе возлюбленную или возлюбленного среди смертных. Смерть происходит оттого, что дух-похититель возлюбил живого и унес его в царство мертвых для брака.

Пропп, как и многие другие исследователи, считал Кощея своеобразной вариацией сказочного змея, который так же живет в пещере, в горах, в подземелье или в Тридесятом царстве, так же «налетает вихрем» и крадет красавиц. Кощей Бессмертный и Змей Горыныч часто исполняют в сказках одну и ту же функцию. Эти персонажи — повелители загробного мира, куда, по древнейшим представлениям, должен был спуститься человек, чтобы обрести магические способности.

У первобытных племен существовали ритуалы инициации, которые сводились к «путешествию» в потусторонний мир. Юноша, прошедший этот обряд, считался вернувшимся с того света и получал право жениться.

Особую инициацию проходили и девушки, ее отголоски также сохранили волшебные сказки.

“

…Можно возразить, что царевна, похищенная «смертью» в лице дракона и т. д., все же никогда не умирает. В более ранних материалах она отбита у змея женихом. Таким образом она имеет как бы два брака: один насильственный со зверем, другой — с человеком, царевичем. <…> Здесь она получает брачное посвящение через Кощея, после чего переходит в руки человеческого жениха.

До наших дней дошли тексты, в которых похищенную Кощеем женщину выручает ее сын. Например, сказка «Кощей Бессмертный» из сборника Александра Афанасьева начинается так: «В некотором царстве, в некотором государстве жил-был царь; у этого царя было три сына, все они были на возрасте. Только мать их вдруг унес Кош Бессмертный». Все сыновья по очереди отправляются на поиски матери, но вызволить ее удается лишь младшему — Ивану-царевичу. По пути он спасает еще одну пленницу Кощея — царскую дочь, на которой впоследствии женится.

В этом сюжете, как и во многих других, описана смерть Кощея: «У меня смерть, — говорит он, — в таком-то месте; там стоит дуб, под дубом ящик, в ящике заяц, в зайце утка, в утке яйцо, в яйце моя смерть». Иногда в сказке говорится, что внутри яйца находится игла, а смерть Кощея — на конце той иглы.

Исследователи связывали кощееву смерть из ларца с древнейшими представлениями о душе и мире:

“

…Душа мыслится как самостоятельное существо, могущее жить вне человека. Для этого даже не всегда нужно умереть. И живой человек может иметь душу или одну из душ вне себя. Это так называемая внешняя душа, bush soul. Обладателем такой души является Кощей.

Владимир Пропп, «Исторические корни волшебной сказки»

“

Исследователь славянской культуры Борис Рыбаков считал, что местонахождение смерти Кощея соотнесено с моделью вселенной — яйцом — и подчеркивал, что охранителями его являются представители всех разделов мира: вода (море-океан), земля (остров), растения (дуб), животные (заяц), птицы (утка). Тогда в дубе при желании можно увидеть и неизбежное «мировое древо». <…> Игла, булавка в народной культуре является предметом-оберегом и одновременно орудием порчи. По восточнославянским представлениям, ведьма, змора или огненный змей («дублером» которого в сказках выступает иногда Кощей) могут оборачиваться иголкой. Следовало ломать и выбрасывать иглу, которой пользовались в ритуальных действиях.

Наталья Кротова. «Как убить Кощея бессмертного?»

В эпоху Киевской Руси появились былины — значительно позднее, чем зародились сказки. В них тоже фигурировал Кощей, но уже в другом качестве: не как царь потустороннего мира, а как реальный враг, нападающий на Русь. В былине «Иван Годинович» герой прямо называет Кощея «поганым татарином». Возможно, именно в это время Кош-повелитель превратился в Кощея-раба. А его смерть уже была связана не с магическим ритуалом, а с вполне прозаическим случаем:

“

И не попал-то Кощей в Ивана во белы груди,

А пролетела калена стрела в толстый сырой дуб,

От сыра дуба стрелочка отскакивала,

Становилася Кощею во белы груди:

От своих рук Кощею и смерть пришла.

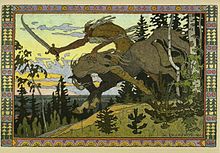

Виктор Васнецов. Марья Моревна и Кащей Бессмертный. 1926

Государственная Третьяковская галерея, Москва

Иван Билибин. Кащей Бессмертный. Иллюстрация к сказке «Марья Моревна». 1901

Частное собрание

Борис Зворыкин. Иллюстрация к сказке «Марья Моревна». 1904

Частное собрание

Тамара Шеварева. Иллюстрация к сказке «Марья Моревна». 1990

Частное собрание

Сергей Малютин. Кощей. 1904

Частное собрание