This article is about the 1835 literary fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. For other uses, see Thumbelina (disambiguation).

| «Thumbelina» | ||

|---|---|---|

| by Hans Christian Andersen | ||

Illustration by Vilhelm Pedersen, |

||

| Original title | Tommelise | |

| Translator | Mary Howitt | |

| Country | Denmark | |

| Language | Danish | |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale | |

| Published in | Fairy Tales Told for Children. First Collection. Second Booklet. 1835. (Eventyr, fortalte for Børn. Første Samling. Andet Hefte. 1835.) | |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection | |

| Publisher | C. A. Reitzel | |

| Media type | ||

| Publication date | 16 December 1835 | |

| Published in English | 1846 | |

| Chronology | ||

|

||

| Full text | ||

Thumbelina (; Danish: Tommelise) is a literary fairy tale written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen first published by C. A. Reitzel on 16 December 1835 in Copenhagen, Denmark, with «The Naughty Boy» and «The Travelling Companion» in the second instalment of Fairy Tales Told for Children. Thumbelina is about a tiny girl and her adventures with marriage-minded toads, moles, and cockchafers. She successfully avoids their intentions before falling in love with a flower-fairy prince just her size.

Thumbelina is chiefly Andersen’s invention, though he did take inspiration from tales of miniature people such as «Tom Thumb». Thumbelina was published as one of a series of seven fairy tales in 1835 which were not well received by the Danish critics who disliked their informal style and their lack of morals. One critic, however, applauded Thumbelina.[1] The earliest English translation of Thumbelina is dated 1846. The tale has been adapted to various media including television drama and animated film.

Plot[edit]

A woman yearning for a child asks a witch for advice, and is presented with a barley which she is told to go home and plant (in the first English translation of 1847 by Mary Howitt, the tale opens with a beggar woman giving a peasant’s wife a barleycorn in exchange for food). After the barleycorn is planted and sprouts, a tiny girl named Thumbelina (Tommelise) emerges from its flower.

One night, Thumbelina, asleep in her walnut-shell cradle, is carried off by a toad who wants her as a bride for her son. With the help of friendly fish and a butterfly, Thumbelina escapes the toad and her son, and drifts on a lily pad until captured by a stag beetle who later discards her when his friends reject her company.

Thumbelina tries to protect herself from the elements. When winter comes, she is in desperate straits. She is finally given shelter by an old field mouse and tends her dwelling in gratitude. Thumbelina sees a swallow who is injured while visiting a mole, a neighbor of the field mouse. She meets the swallow one night and finds out what happened to him. She keeps on visiting the swallow during midnight without telling the field mouse and tries to help him gain strength and she frequently spends time with him singing songs and telling him stories and listening to his stories in the winter until spring arrives. The swallow, after becoming healthy, promises that he would come to that spot again and flies away saying goodbye to Thumbelina.

At the end of winter, the mouse suggests Thumbelina marry the mole, but Thumbelina finds the prospect of being married to such a creature repulsive because he spends all his days underground and never sees the sun or sky, even though he is impressive with his knowledge of ancient history and lots of other topics. The field mouse keeps pushing Thumbelina into the marriage, insisting the mole is a good match for her. Eventually Thumbelina sees little choice but to agree, but cannot bear the thought of the mole keeping her underground and never seeing the sun.

At the last minute, Thumbelina escapes the situation by fleeing to a far land with the swallow. In a sunny field of flowers, Thumbelina meets a tiny flower-fairy prince just her size and to her liking; they eventually wed. She receives a pair of wings to accompany her husband on his travels from flower to flower, and a new name, Maia. In the end, the swallow is heartbroken once Thumbelina marries the flower-fairy prince, and flies off eventually arriving at a small house. There, he tells Thumbelina’s story to a man who is implied to be Andersen himself, who chronicles the story in a book.[2]

Background[edit]

Hans Christian Andersen was born in Odense, Denmark on 2 April 1805 to Hans Andersen, a shoemaker, and Anne Marie Andersdatter.[3] An only child, Andersen shared a love of literature with his father, who read him The Arabian Nights and the fables of Jean de la Fontaine. Together, they constructed panoramas, pop-up pictures and toy theatres, and took long jaunts into the countryside.[4]

Andersen’s father died in 1816,[5] and from then on, Andersen was left on his own. In order to escape his poor, illiterate mother, he promoted his artistic inclinations and courted the cultured middle class of Odense, singing and reciting in their drawing-rooms. On 4 September 1819, the fourteen-year-old Andersen left Odense for Copenhagen with the few savings he had acquired from his performances, a letter of reference to the ballerina Madame Schall, and youthful dreams and intentions of becoming a poet or an actor.[6]

After three years of rejections and disappointments, he finally found a patron in Jonas Collin, the director of the Royal Theatre, who, believing in the boy’s potential, secured funds from the king to send Andersen to a grammar school in Slagelse, a provincial town in west Zealand, with the expectation that the boy would continue his education at Copenhagen University at the appropriate time.

At Slagelse, Andersen fell under the tutelage of Simon Meisling, a short, stout, balding thirty-five-year-old classicist and translator of Virgil’s Aeneid. Andersen was not the quickest student in the class and was given generous doses of Meisling’s contempt.[7] «You’re a stupid boy who will never make it», Meisling told him.[8] Meisling is believed to be the model for the learned mole in «Thumbelina».[9]

Fairy tale and folklorists Iona and Peter Opie have proposed the tale as a «distant tribute» to Andersen’s confidante, Henriette Wulff, the small, frail, hunchbacked daughter of the Danish translator of Shakespeare who loved Andersen as Thumbelina loves the swallow;[10] however, no written evidence exists to support the theory.[9]

Sources and inspiration[edit]

«Thumbelina» is essentially Andersen’s invention but takes inspiration from the traditional tale of «Tom Thumb» (both tales begin with a childless woman consulting a supernatural being about acquiring a child). Other inspirations were the six-inch Lilliputians in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Voltaire’s short story «Micromégas» with its cast of huge and miniature peoples, and E. T. A. Hoffmann’s hallucinatory, erotic tale «Meister Floh», in which a tiny lady a span in height torments the hero. A tiny girl figures in Andersen’s prose fantasy «A Journey on Foot from Holmen’s Canal to the East Point of Amager» (1828),[9][11] and a literary image similar to Andersen’s tiny being inside a flower is found in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s «Princess Brambilla» (1821).[12]

Publication and critical reception[edit]

Andersen published two installments of his first collection of Fairy Tales Told for Children in 1835, the first in May and the second in December. «Thumbelina» was first published in the December installment by C. A. Reitzel on 16 December 1835 in Copenhagen. «Thumbelina» was the first tale in the booklet which included two other tales: «The Naughty Boy» and «The Traveling Companion». The story was republished in collected editions of Andersen’s works in 1850 and 1862.[13]

The first reviews of the seven tales of 1835 did not appear until 1836 and the Danish critics were not enthusiastic. The informal, chatty style of the tales and their lack of morals were considered inappropriate in children’s literature. One critic however acknowledged «Thumbelina» to be «the most delightful fairy tale you could wish for».[14]

The critics offered Andersen no further encouragement. One literary journal never mentioned the tales at all while another advised Andersen not to waste his time writing fairy tales. One critic stated that Andersen «lacked the usual form of that kind of poetry […] and would not study models». Andersen felt he was working against their preconceived notions of what a fairy tale should be, and returned to novel-writing, believing it was his true calling.[15] The critical reaction to the 1835 tales was so harsh that he waited an entire year before publishing «The Little Mermaid» and «The Emperor’s New Clothes» in the third and final installment of Fairy Tales Told for Children.

English translations[edit]

In 1861, Alfred Wehnert translated the tale into English in Andersen’s Tales for Children under the title Little Thumb.[16] Mary Howitt published the story as «Tommelise» in Wonderful Stories for Children in 1846. However, she did not approve of the opening scene with the witch, and, instead, had the childless woman provide bread and milk to a hungry beggar woman who then rewarded her hostess with a barleycorn.[10] Charles Boner also translated the tale in 1846 as «Little Ellie» while Madame de Chatelain dubbed the child ‘Little Totty’ in her 1852 translation. The editor of The Child’s Own Book (1853) called the child throughout, ‘Little Maja’.

H. W. Dulcken was probably the translator responsible for the name, ‘Thumbelina’. His widely published volumes of Andersen’s tales appeared in 1864 and 1866.[10] Mrs. H.B. Paulli translated the name as ‘Little Tiny’ in the late-nineteenth century.[17]

In the twentieth century, Erik Christian Haugaard translated the name as ‘Inchelina’ in 1974,[18] and Jeffrey and Diane Crone Frank translated the name as ‘Thumbelisa’ in 2005. Modern English translations of «Thumbelina» are found in the six-volume complete edition of Andersen’s tales from the 1940s by Jean Hersholt, and Erik Christian Haugaard’s translation of the complete tales in 1974.[19]

[edit]

For fairy tale researchers and folklorists Iona and Peter Opie, «Thumbelina» is an adventure story from the feminine point of view with its moral being people are happiest with their own kind. They point out that Thumbelina is a passive character, the victim of circumstances; whereas her male counterpart Tom Thumb (one of the tale’s inspirations) is an active character, makes himself felt, and exerts himself.[10]

Folklorist Maria Tatar sees «Thumbelina» as a runaway bride story and notes that it has been viewed as an allegory about arranged marriages, and a fable about being true to one’s heart that upholds the traditional notion that the love of a prince is to be valued above all else. She points out that in Hindu belief, a thumb-sized being known as the innermost self or soul dwells in the heart of all beings, human or animal, and that the concept may have migrated to European folklore and taken form as Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, both of whom seek transfiguration and redemption. She detects parallels between Andersen’s tale and the Greek myth of Demeter and her daughter, Persephone, and, notwithstanding the pagan associations and allusions in the tale, notes that «Thumbelina» repeatedly refers to Christ’s suffering and resurrection, and the Christian concept of salvation.[20]

Andersen biographer Jackie Wullschlager indicates that «Thumbelina» was the first of Andersen’s tales to dramatize the sufferings of one who is different, and, as a result of being different, becomes the object of mockery. It was also the first of Andersen’s tales to incorporate the swallow as the symbol of the poetic soul and Andersen’s identification with the swallow as a migratory bird whose pattern of life his own traveling days were beginning to resemble.[21]

Roger Sale believes Andersen expressed his feelings of social and sexual inferiority by creating characters that are inferior to their beloveds. The Little Mermaid, for example, has no soul while her human beloved has a soul as his birthright. In «Thumbelina», Andersen suggests the toad, the beetle, and the mole are Thumbelina’s inferiors and should remain in their places rather than wanting their superior. Sale indicates they are not inferior to Thumbelina but simply different. He suggests that Andersen may have done some damage to the animal world when he colored his animal characters with his own feelings of inferiority.[22]

Jacqueline Banerjee views the tale as a success story. «Not surprisingly,» she writes, «”Thumbelina» is now often read as a story of specifically female empowerment.»[23] Susie Stephens believes Thumbelina herself is a grotesque, and observes that «the grotesque in children’s literature is […] a necessary and beneficial component that enhances the psychological welfare of the young reader». Children are attracted to the cathartic qualities of the grotesque, she suggests.[24] Sidney Rosenblatt in his essay «Thumbelina and the Development of Female Sexuality» believes the tale may be analyzed, from the perspective of Freudian psychoanalysis, as the story of female masturbation. Thumbelina herself, he posits, could symbolize the clitoris, her rose petal coverlet the labia, the white butterfly «the budding genitals», and the mole and the prince the anal and vaginal openings respectively.[25]

Adaptations[edit]

Animation[edit]

The earliest animated version of the tale is a silent black-and-white release by director Herbert M. Dawley in 1924.[citation needed] Lotte Reiniger released a 10-minute cinematic adaptation in 1954 featuring her «silhouette» puppets.[26]

In 1964 Soyuzmultfilm released Dyuymovochka, a half-hour Russian adaptation of the fairy tale directed by Leonid Amalrik.[citation needed] Although the screenplay by Nikolai Erdman stayed faithful to the story, it was noted for satirical characters and dialogues (many of them turned into catchphrases).[27]

In 1992, Golden Films released Thumbelina (1992),[citation needed] and Tom Thumb Meets Thumbelina afterwards. A Japanese animated series adapted the plot and made it into a movie, Thumbelina: A Magical Story (1992), released in 1993.[28]

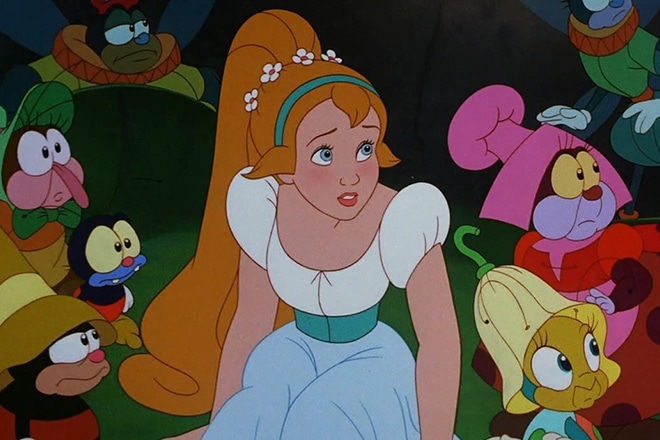

On March 30, 1994, Warner Brothers released the animated film Thumbelina (1994),[29] directed by Don Bluth and Gary Goldman, with Jodi Benson as the voice of Thumbelina.

Live action[edit]

On June 11, 1985, a television dramatization of the tale was broadcast as the 12th episode of the anthology series Faerie Tale Theatre. The production starred Carrie Fisher.[30]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 165.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 221–9

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 9

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 13

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 25–26

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 32–33

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 60–61

- ^ Frank & Frank 2005, p. 77

- ^ a b c Frank & Frank 2005, p. 76

- ^ a b c d Opie & Opie 1974, p. 219

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 162.

- ^ Frank & Frank 2005, pp. 75–76

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen: Thumbelina». Hans Christian Andersen Center. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 165

- ^ Andersen 2000, p. 335

- ^ Andersen, Hans Christian (1861). Andersen’s Tales for Children. Bell and Daldy.

- ^ Eastman, p. 258

- ^ Andersen 1983, p. 29

- ^ Classe 2000, p. 42

- ^ Andersen 2008, pp. 193–194, 205

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 163

- ^ Sale 1978, pp. 65–68

- ^ Banerjee, Jacqueline (2008). «The Power of «Faerie»: Hans Christian Andersen as a Children’s Writer». The Victorian Web: Literature, History, & Culture in the Age of Victoria. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Stephens, Susie. «The Grotesque in Children’s Literature». Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Siegel 1992, pp. 123, 126

- ^ «Däumlienchen». IMDb.

- ^ Petr Bagrov. Swine-herd and Stableman. From Hans Christian to Christian Hans article from Seance № 25/26, 2005 ISSN 0136-0108 (in Russian)

- ^ Clements, Jonathan; Helen McCarthy (2001-09-01). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (1st ed.). Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. p. 399. ISBN 1-880656-64-7. OCLC 47255331.

- ^ «Thumbelina — Character Designs, Cornelius, Thumbelina, and Bumble Bee». SCAD Libraries. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ «DVD Verdict Review — Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre: The Complete Collection». dvdverdict.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17.

References[edit]

- Andersen, Hans Christian (1983) [1974]. The Complete Fairy Tales and Stories. Translated by Haugaard, Erik Christian. New York, NY: Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-18951-6.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2000) [1871]. The Fairy Tale of My Life. New York, NY: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1105-7.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2008). Tatar, Maria (ed.). The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393060812.

- Classe, O., ed. (2000). Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English; v.2. Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-884964-36-2.

- Eastman, Mary Huse (ed.). Index to Fairy Tales, Myths and Legends. BiblioLife, LLC.

- Frank, Diane Crone; Frank, Jeffrey (2005). The Stories of Hans Christian Andersen. Durham, NC and London, UK: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3693-6.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211559-6.

- Sale, Roger (1978). Fairy Tales and After: From Snow White to E.B. White. New Haven, CT: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-29157-3.

- Siegel, Elaine V., ed. (1992). Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Women. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel, Inc. ISBN 0-87630-655-5.

- Wullschlager, Jackie (2002). Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-91747-9.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thumbelina.

- Thumbelina English translation by Jean Hersholt

- Thumbelina: The Musical Musical of Thumbelina by Chris Seed and Maxine Gallagher

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

This article is about the 1835 literary fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen. For other uses, see Thumbelina (disambiguation).

| «Thumbelina» | ||

|---|---|---|

| by Hans Christian Andersen | ||

Illustration by Vilhelm Pedersen, |

||

| Original title | Tommelise | |

| Translator | Mary Howitt | |

| Country | Denmark | |

| Language | Danish | |

| Genre(s) | Literary fairy tale | |

| Published in | Fairy Tales Told for Children. First Collection. Second Booklet. 1835. (Eventyr, fortalte for Børn. Første Samling. Andet Hefte. 1835.) | |

| Publication type | Fairy tale collection | |

| Publisher | C. A. Reitzel | |

| Media type | ||

| Publication date | 16 December 1835 | |

| Published in English | 1846 | |

| Chronology | ||

|

||

| Full text | ||

Thumbelina (; Danish: Tommelise) is a literary fairy tale written by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen first published by C. A. Reitzel on 16 December 1835 in Copenhagen, Denmark, with «The Naughty Boy» and «The Travelling Companion» in the second instalment of Fairy Tales Told for Children. Thumbelina is about a tiny girl and her adventures with marriage-minded toads, moles, and cockchafers. She successfully avoids their intentions before falling in love with a flower-fairy prince just her size.

Thumbelina is chiefly Andersen’s invention, though he did take inspiration from tales of miniature people such as «Tom Thumb». Thumbelina was published as one of a series of seven fairy tales in 1835 which were not well received by the Danish critics who disliked their informal style and their lack of morals. One critic, however, applauded Thumbelina.[1] The earliest English translation of Thumbelina is dated 1846. The tale has been adapted to various media including television drama and animated film.

Plot[edit]

A woman yearning for a child asks a witch for advice, and is presented with a barley which she is told to go home and plant (in the first English translation of 1847 by Mary Howitt, the tale opens with a beggar woman giving a peasant’s wife a barleycorn in exchange for food). After the barleycorn is planted and sprouts, a tiny girl named Thumbelina (Tommelise) emerges from its flower.

One night, Thumbelina, asleep in her walnut-shell cradle, is carried off by a toad who wants her as a bride for her son. With the help of friendly fish and a butterfly, Thumbelina escapes the toad and her son, and drifts on a lily pad until captured by a stag beetle who later discards her when his friends reject her company.

Thumbelina tries to protect herself from the elements. When winter comes, she is in desperate straits. She is finally given shelter by an old field mouse and tends her dwelling in gratitude. Thumbelina sees a swallow who is injured while visiting a mole, a neighbor of the field mouse. She meets the swallow one night and finds out what happened to him. She keeps on visiting the swallow during midnight without telling the field mouse and tries to help him gain strength and she frequently spends time with him singing songs and telling him stories and listening to his stories in the winter until spring arrives. The swallow, after becoming healthy, promises that he would come to that spot again and flies away saying goodbye to Thumbelina.

At the end of winter, the mouse suggests Thumbelina marry the mole, but Thumbelina finds the prospect of being married to such a creature repulsive because he spends all his days underground and never sees the sun or sky, even though he is impressive with his knowledge of ancient history and lots of other topics. The field mouse keeps pushing Thumbelina into the marriage, insisting the mole is a good match for her. Eventually Thumbelina sees little choice but to agree, but cannot bear the thought of the mole keeping her underground and never seeing the sun.

At the last minute, Thumbelina escapes the situation by fleeing to a far land with the swallow. In a sunny field of flowers, Thumbelina meets a tiny flower-fairy prince just her size and to her liking; they eventually wed. She receives a pair of wings to accompany her husband on his travels from flower to flower, and a new name, Maia. In the end, the swallow is heartbroken once Thumbelina marries the flower-fairy prince, and flies off eventually arriving at a small house. There, he tells Thumbelina’s story to a man who is implied to be Andersen himself, who chronicles the story in a book.[2]

Background[edit]

Hans Christian Andersen was born in Odense, Denmark on 2 April 1805 to Hans Andersen, a shoemaker, and Anne Marie Andersdatter.[3] An only child, Andersen shared a love of literature with his father, who read him The Arabian Nights and the fables of Jean de la Fontaine. Together, they constructed panoramas, pop-up pictures and toy theatres, and took long jaunts into the countryside.[4]

Andersen’s father died in 1816,[5] and from then on, Andersen was left on his own. In order to escape his poor, illiterate mother, he promoted his artistic inclinations and courted the cultured middle class of Odense, singing and reciting in their drawing-rooms. On 4 September 1819, the fourteen-year-old Andersen left Odense for Copenhagen with the few savings he had acquired from his performances, a letter of reference to the ballerina Madame Schall, and youthful dreams and intentions of becoming a poet or an actor.[6]

After three years of rejections and disappointments, he finally found a patron in Jonas Collin, the director of the Royal Theatre, who, believing in the boy’s potential, secured funds from the king to send Andersen to a grammar school in Slagelse, a provincial town in west Zealand, with the expectation that the boy would continue his education at Copenhagen University at the appropriate time.

At Slagelse, Andersen fell under the tutelage of Simon Meisling, a short, stout, balding thirty-five-year-old classicist and translator of Virgil’s Aeneid. Andersen was not the quickest student in the class and was given generous doses of Meisling’s contempt.[7] «You’re a stupid boy who will never make it», Meisling told him.[8] Meisling is believed to be the model for the learned mole in «Thumbelina».[9]

Fairy tale and folklorists Iona and Peter Opie have proposed the tale as a «distant tribute» to Andersen’s confidante, Henriette Wulff, the small, frail, hunchbacked daughter of the Danish translator of Shakespeare who loved Andersen as Thumbelina loves the swallow;[10] however, no written evidence exists to support the theory.[9]

Sources and inspiration[edit]

«Thumbelina» is essentially Andersen’s invention but takes inspiration from the traditional tale of «Tom Thumb» (both tales begin with a childless woman consulting a supernatural being about acquiring a child). Other inspirations were the six-inch Lilliputians in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Voltaire’s short story «Micromégas» with its cast of huge and miniature peoples, and E. T. A. Hoffmann’s hallucinatory, erotic tale «Meister Floh», in which a tiny lady a span in height torments the hero. A tiny girl figures in Andersen’s prose fantasy «A Journey on Foot from Holmen’s Canal to the East Point of Amager» (1828),[9][11] and a literary image similar to Andersen’s tiny being inside a flower is found in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s «Princess Brambilla» (1821).[12]

Publication and critical reception[edit]

Andersen published two installments of his first collection of Fairy Tales Told for Children in 1835, the first in May and the second in December. «Thumbelina» was first published in the December installment by C. A. Reitzel on 16 December 1835 in Copenhagen. «Thumbelina» was the first tale in the booklet which included two other tales: «The Naughty Boy» and «The Traveling Companion». The story was republished in collected editions of Andersen’s works in 1850 and 1862.[13]

The first reviews of the seven tales of 1835 did not appear until 1836 and the Danish critics were not enthusiastic. The informal, chatty style of the tales and their lack of morals were considered inappropriate in children’s literature. One critic however acknowledged «Thumbelina» to be «the most delightful fairy tale you could wish for».[14]

The critics offered Andersen no further encouragement. One literary journal never mentioned the tales at all while another advised Andersen not to waste his time writing fairy tales. One critic stated that Andersen «lacked the usual form of that kind of poetry […] and would not study models». Andersen felt he was working against their preconceived notions of what a fairy tale should be, and returned to novel-writing, believing it was his true calling.[15] The critical reaction to the 1835 tales was so harsh that he waited an entire year before publishing «The Little Mermaid» and «The Emperor’s New Clothes» in the third and final installment of Fairy Tales Told for Children.

English translations[edit]

In 1861, Alfred Wehnert translated the tale into English in Andersen’s Tales for Children under the title Little Thumb.[16] Mary Howitt published the story as «Tommelise» in Wonderful Stories for Children in 1846. However, she did not approve of the opening scene with the witch, and, instead, had the childless woman provide bread and milk to a hungry beggar woman who then rewarded her hostess with a barleycorn.[10] Charles Boner also translated the tale in 1846 as «Little Ellie» while Madame de Chatelain dubbed the child ‘Little Totty’ in her 1852 translation. The editor of The Child’s Own Book (1853) called the child throughout, ‘Little Maja’.

H. W. Dulcken was probably the translator responsible for the name, ‘Thumbelina’. His widely published volumes of Andersen’s tales appeared in 1864 and 1866.[10] Mrs. H.B. Paulli translated the name as ‘Little Tiny’ in the late-nineteenth century.[17]

In the twentieth century, Erik Christian Haugaard translated the name as ‘Inchelina’ in 1974,[18] and Jeffrey and Diane Crone Frank translated the name as ‘Thumbelisa’ in 2005. Modern English translations of «Thumbelina» are found in the six-volume complete edition of Andersen’s tales from the 1940s by Jean Hersholt, and Erik Christian Haugaard’s translation of the complete tales in 1974.[19]

[edit]

For fairy tale researchers and folklorists Iona and Peter Opie, «Thumbelina» is an adventure story from the feminine point of view with its moral being people are happiest with their own kind. They point out that Thumbelina is a passive character, the victim of circumstances; whereas her male counterpart Tom Thumb (one of the tale’s inspirations) is an active character, makes himself felt, and exerts himself.[10]

Folklorist Maria Tatar sees «Thumbelina» as a runaway bride story and notes that it has been viewed as an allegory about arranged marriages, and a fable about being true to one’s heart that upholds the traditional notion that the love of a prince is to be valued above all else. She points out that in Hindu belief, a thumb-sized being known as the innermost self or soul dwells in the heart of all beings, human or animal, and that the concept may have migrated to European folklore and taken form as Tom Thumb and Thumbelina, both of whom seek transfiguration and redemption. She detects parallels between Andersen’s tale and the Greek myth of Demeter and her daughter, Persephone, and, notwithstanding the pagan associations and allusions in the tale, notes that «Thumbelina» repeatedly refers to Christ’s suffering and resurrection, and the Christian concept of salvation.[20]

Andersen biographer Jackie Wullschlager indicates that «Thumbelina» was the first of Andersen’s tales to dramatize the sufferings of one who is different, and, as a result of being different, becomes the object of mockery. It was also the first of Andersen’s tales to incorporate the swallow as the symbol of the poetic soul and Andersen’s identification with the swallow as a migratory bird whose pattern of life his own traveling days were beginning to resemble.[21]

Roger Sale believes Andersen expressed his feelings of social and sexual inferiority by creating characters that are inferior to their beloveds. The Little Mermaid, for example, has no soul while her human beloved has a soul as his birthright. In «Thumbelina», Andersen suggests the toad, the beetle, and the mole are Thumbelina’s inferiors and should remain in their places rather than wanting their superior. Sale indicates they are not inferior to Thumbelina but simply different. He suggests that Andersen may have done some damage to the animal world when he colored his animal characters with his own feelings of inferiority.[22]

Jacqueline Banerjee views the tale as a success story. «Not surprisingly,» she writes, «”Thumbelina» is now often read as a story of specifically female empowerment.»[23] Susie Stephens believes Thumbelina herself is a grotesque, and observes that «the grotesque in children’s literature is […] a necessary and beneficial component that enhances the psychological welfare of the young reader». Children are attracted to the cathartic qualities of the grotesque, she suggests.[24] Sidney Rosenblatt in his essay «Thumbelina and the Development of Female Sexuality» believes the tale may be analyzed, from the perspective of Freudian psychoanalysis, as the story of female masturbation. Thumbelina herself, he posits, could symbolize the clitoris, her rose petal coverlet the labia, the white butterfly «the budding genitals», and the mole and the prince the anal and vaginal openings respectively.[25]

Adaptations[edit]

Animation[edit]

The earliest animated version of the tale is a silent black-and-white release by director Herbert M. Dawley in 1924.[citation needed] Lotte Reiniger released a 10-minute cinematic adaptation in 1954 featuring her «silhouette» puppets.[26]

In 1964 Soyuzmultfilm released Dyuymovochka, a half-hour Russian adaptation of the fairy tale directed by Leonid Amalrik.[citation needed] Although the screenplay by Nikolai Erdman stayed faithful to the story, it was noted for satirical characters and dialogues (many of them turned into catchphrases).[27]

In 1992, Golden Films released Thumbelina (1992),[citation needed] and Tom Thumb Meets Thumbelina afterwards. A Japanese animated series adapted the plot and made it into a movie, Thumbelina: A Magical Story (1992), released in 1993.[28]

On March 30, 1994, Warner Brothers released the animated film Thumbelina (1994),[29] directed by Don Bluth and Gary Goldman, with Jodi Benson as the voice of Thumbelina.

Live action[edit]

On June 11, 1985, a television dramatization of the tale was broadcast as the 12th episode of the anthology series Faerie Tale Theatre. The production starred Carrie Fisher.[30]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 165.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, pp. 221–9

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 9

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 13

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 25–26

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 32–33

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, pp. 60–61

- ^ Frank & Frank 2005, p. 77

- ^ a b c Frank & Frank 2005, p. 76

- ^ a b c d Opie & Opie 1974, p. 219

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 162.

- ^ Frank & Frank 2005, pp. 75–76

- ^ «Hans Christian Andersen: Thumbelina». Hans Christian Andersen Center. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 165

- ^ Andersen 2000, p. 335

- ^ Andersen, Hans Christian (1861). Andersen’s Tales for Children. Bell and Daldy.

- ^ Eastman, p. 258

- ^ Andersen 1983, p. 29

- ^ Classe 2000, p. 42

- ^ Andersen 2008, pp. 193–194, 205

- ^ Wullschlager 2002, p. 163

- ^ Sale 1978, pp. 65–68

- ^ Banerjee, Jacqueline (2008). «The Power of «Faerie»: Hans Christian Andersen as a Children’s Writer». The Victorian Web: Literature, History, & Culture in the Age of Victoria. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Stephens, Susie. «The Grotesque in Children’s Literature». Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ Siegel 1992, pp. 123, 126

- ^ «Däumlienchen». IMDb.

- ^ Petr Bagrov. Swine-herd and Stableman. From Hans Christian to Christian Hans article from Seance № 25/26, 2005 ISSN 0136-0108 (in Russian)

- ^ Clements, Jonathan; Helen McCarthy (2001-09-01). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (1st ed.). Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. p. 399. ISBN 1-880656-64-7. OCLC 47255331.

- ^ «Thumbelina — Character Designs, Cornelius, Thumbelina, and Bumble Bee». SCAD Libraries. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ «DVD Verdict Review — Shelley Duvall’s Faerie Tale Theatre: The Complete Collection». dvdverdict.com. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17.

References[edit]

- Andersen, Hans Christian (1983) [1974]. The Complete Fairy Tales and Stories. Translated by Haugaard, Erik Christian. New York, NY: Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-18951-6.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2000) [1871]. The Fairy Tale of My Life. New York, NY: Cooper Square Press. ISBN 0-8154-1105-7.

- Andersen, Hans Christian (2008). Tatar, Maria (ed.). The Annotated Hans Christian Andersen. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 9780393060812.

- Classe, O., ed. (2000). Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English; v.2. Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-884964-36-2.

- Eastman, Mary Huse (ed.). Index to Fairy Tales, Myths and Legends. BiblioLife, LLC.

- Frank, Diane Crone; Frank, Jeffrey (2005). The Stories of Hans Christian Andersen. Durham, NC and London, UK: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3693-6.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211559-6.

- Sale, Roger (1978). Fairy Tales and After: From Snow White to E.B. White. New Haven, CT: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-29157-3.

- Siegel, Elaine V., ed. (1992). Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Women. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel, Inc. ISBN 0-87630-655-5.

- Wullschlager, Jackie (2002). Hans Christian Andersen: The Life of a Storyteller. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-91747-9.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thumbelina.

- Thumbelina English translation by Jean Hersholt

- Thumbelina: The Musical Musical of Thumbelina by Chris Seed and Maxine Gallagher

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

6

Из какого зернышка появился цветок с Дюймовочкой?

10 ответов:

5

0

Прекрасное творение Ганса Христиана Андерсена «Дюймовочка» повествует нам историю миниатюрной, отзывчивой и милой девочки, которую звали Дюймовочкой.

Девочка появилась на свет из цветка, который в свою очередь вырос из я ч м е н н о г о зёрнышка.

Красота Дюймовочки очаровывала всех. Так после того, как её украли началась её длинная история, в которой ей пришлось встретиться с Жабами, Мотыльком, Майским жуком, Полевой мышью, Кротом и Ласточкой.

Но не стоит переживать, как большинство сказок, история имеет счастливый конец, так как Дюймовочка обрела своё счастье с королём эльфов цветов и стала королевой.

2

0

В сказке Ганса Христиана Андерсена «Дюймовочка» женщина не могла иметь детей, но очень хотела ребенка. Волшебница дала ей ячменное зернышко, которое женщина посадила в обыкновенный цветочный горшок. Из зерна очень быстро вырос красивый цветок, а когда он раскрылся, то в нем оказалась маленькая девочка Дюймовочка.

Ответ: ячменное.

2

0

В сказке «Дюймовочка» колдунья дала бездетной женщине ЯЧМЕННОЕ зернышко, и женщина посадила его в цветочный горшок и увидела настоящее чудо — сразу же из семечка вырос росток, и вырос красивый цветок, похожий на тюльпан.

Очевидно потому, что именно в тюльпане есть немного места, чтобы спрятаться такой миниатюрной девочке. Ведь дюйм = 2,5 см.

Но каждый художник представляет этот волшебный цветок по-своему. Верхние фото — из мультфильмов о Дюймовочки (СССР «Союзмультфильм» — 1954 г и США «Дисней» — 1997 г)

Ну, а в книгах встречаются иллюстрации, где волшебный цветок даже похож больше на ирис или на пион, а не только на тюльпан.

Очевидно. что и зернышко было только похоже на ячменное.

1

0

Вот такое точно бывает только в сказках, ведь Дюймовочка появилась из тюльпана, а любой садовод знает, что тюльпан — растение луковичное и семенами его размножить почти невозможно.

Оказывается, тюльпан для Дюймовочки вырос из ЯЧМЕННОГО семечка.

Так что произошло настоящее сказочное чудо.

1

0

Цветок в котором появилась Дюймовочка вырос из волшебного ячменного зернышка,которое старая колдунья дала женщине.Зернышко действительно было волшебное, потому что из него вырос не ячмень, а тюльпан в котором сидела маленькая девочка.

1

0

Это наверно самый волшебный вопрос про самую волшебную сказку. Что бы дать правильный ответ в этой викторине достаточно вспомнить текст самой сказки. Там сказано о женщине которая посадила ячменное зернышко в результате чего и произошли все дальнейшие сказочные события.

Ответ — ячменное.

1

0

В сказке Дюймовочка появилась из цветка, семя этого цветка колдунья дала женщине, которая очень хотела иметь ребенка, так на свет появилась маленькая девочка Дюймовочка. А появилась малышка из цветка, выросшего из ячменного зернышка.

1

0

В известной сказке Ганса Христиана Андерсена маленькая девочка появилась из цветка. А цветок этот волшебным образом вырос из ячменного зернышка. В сказке все может быть.

Правильный ответ будет ЯЧМЕННОЕ.

1

0

Если вспомнить сказку Х. Андерсена, то колдунья дала одинокой женщине зернышко ячменя, которая та и посадила в цветочный горшок. Из зернышка ячменя вырос цветок(больше похожий на тюльпан), внутри него и оказалась девочка Дюймовочка.

0

0

Согласно сказки Х. Андерсона девочка Дюмовочка, персонаж из одноименной сказки, появилась из ячменного зернышка. Это зернышко дала простой женщине, которая хотела иметь дочку, ведьма и сказала посадить зернышко в цветочный горшочек.

Читайте также

Финал сказки Андерсена «Дюймовочка» великолепный. Эта маленькая девочка, которая перенесла на своих хрупких плечиках все невзгоды, девочка, которую истязали, кому не лень, в конце концов стала счастливой, вышла замуж за принца-эльфа, и они вместе парили над цветами и вкушали все радости мира. Плохо лишь то, что мы уже никогда не узнаем, какие прекрасные дети родились от такой прекрасной любви, но об этом мы можем только предполагать.Редко, когда у Андерсена сказки имеют счастливый конец, но именно эта прекрасная сказка «Дюймовочка» как раз заканчивается тем, что девочка находит свою любовь, устраивает свою жизнь, и все рады этому…

Дюймовочка понравилась Жуку и он готов был взять ее в жены. Но приведя ее в свое общество, ее не оценили и не приняли. Так как она сильно от них отличалась. А Жуку чужое мнение важнее собственного.

Он как джентельмен вернул ее туда, где они и познакомились. Думаю, что у них все равно ничего бы не получилось. Уж больно они разные. Жук по жизни весельчак, ведет разгульный образ жизни. А Дюймовочка полная противоположность данного персонажа.

Составим план пересказа сказки Андерсена «Дюймовочка»:

- Бездетная женщина и старая колдунья.

- Девочка из бутона

- Как жила Дюймовочка у женщины

- Коварная страшная жаба и ее сынок, похищение Дюймовочки.

- Рыбы помогают Дюймовочке бежать

- Дюймовочку берет с собой майский жук.

- Родные майского жука критикуют Дюймовочку и жук ее высаживает на ромашку.

- Дюймовочка живет в лесу до осени.

- Дом полевой мыши и старый крот

- Мертвая ласточка оживает.

- Дюймовочка ухаживает за ласточкой

- Дюймовочка остается на лето у мыши и готовит приданое.

- Дюймовочка плачет и ласточка берет ее с собой

- Дюймовочка выходит заму за короля эльфов и получает крылья.

Мы все привыкли, что эта маленькая девочка из гениальной сказки Андерсена звалась Дюймовочка, так как она ростом была с дюйм (это два с половиной сантиметра),но в конце сказки Дюймовочку назвали другим именем. Это произошло после того, как эльфы подарили ей крылышки, видимо, когда кто-то обретает крылья, имя меняется:).

И не будем забывать, что дело происходило весной, в период цветения трав и деревьев, видимо поэтому, имя Дюймовочке было дано такое

М А Й Я.

Выдать замуж Дюймовочку за своего сынка хотела противная жаба, но бабочки, рыбки и рак спасли её и она уплыла на листе кувшинки.

Затем старая крыса, приютившая её, решила выдать её замуж за своего соседа, жадного слепого крота.

И только спасенная девочкой ласточка, помогла ей улететь в теплую страну, где Дюймовочка встретила похожего на себя короля эльфов. Он влюбился в неё и она СОГЛАСИЛАСЬ сама выйти за него замуж, а на свадьбе и получила прекрасный подарок — волшебные крылышки, с помощью которых и сама научилась летать.

Хрупкое очарование

Героиня андерсеновской сказки — прелестная крошечная девочка ростом не более дюйма. Отсюда и необычное имя — Дюймовочка. Малютка появилась на свет из пёстрого тюльпана. Её мать, одинокая женщина, мечтала о ребёнке и обратилась за помощью к местной колдунье. Та продала клиентке волшебное зерно, из которого вырос диковинный цветок. В его чашечке сидела маленькая девчушка. Так бездетная женщина получила долгожданную дочку — красивую и хрупкую.

Дюймовочка живёт счастливо и беззаботно. Мать мастерит ей колыбельку из ореховой скорлупки, вместо матраца — голубые фиалки, а одеяло крошке заменяет ароматный лепесток розы. Днём девочка играет на столе, где для неё обустроен бассейн — широкая тарелка с водой. Малышка рассекает водную гладь на лодке, сделанной из тюльпанного лепестка и поёт весёлые песни. Голосок у неё очаровательный и нежный — заслушаешься! Мама умиляется — уж очень трогательная картина.

Нелюбимые женихи

Радость маленькой семьи неожиданно обрывается: Дюймовочку похищают. Ночью в открытое окно запрыгивает жаба и уносит скорлупку вместе со спящей девочкой. Она хочет выдать малышку замуж за своего уродливого и глупого сына. Но планам коварного создания не суждено сбыться: стайка рыбок жалеет Дюймовочку и помогает ей сбежать — уплыть от жаб на листе водяной лилии.

Малютка недолго наслаждается свободой: её перехватывает новый «жених» — майский жук. Он уносит девочку на зелёное дерево и знакомит со своими друзьями и родственниками. Но жучки не принимают Дюймовочку, потому что она не соответствует их представлениям о красоте — слишком похожа на человека. Под влиянием общественного мнения, майский жук меняет своё отношение к девчушке — спускает её на землю и улетает прочь. Дюймовочка чувствует себя несчастной и некрасивой, потому что её отвергли.

Всё лето крошка живёт одна, среди травы и цветов, а когда наступают холода, она просит о помощи полевую Мышь. Та оказывается доброй старушкой и пускает бедняжку жить к себе. Девочка помогает хозяйке с домашними делами и развлекает её сказками. Вскоре Мышь надумывает выдать свою подопечную замуж за соседа Крота. Он очень богат, но скуп и скучен. Будучи слепым, Крот равнодушен к красоте окружающего мира и презирает всё, что мило сердцу Дюймовочки — пение птиц, солнечный свет, ароматы цветов. Малютка не хочет становиться женой Крота, но Мышь угрожает ей. Только чудо спасает красавицу от ненавистного брака.

Изображая женихов сказочной героини, Андерсен создаёт яркие и запоминающиеся образы, воплощающие пороки общества. Безобразные жабы олицетворяют алчность, глупость и жестокость. Майский жук — образец ветрености и зависимости от чужого мнения. Крот предстаёт состоятельным и учёным, но духовно мёртвым персонажем. Ему чужды сочувствие, милосердие и щедрость. Приземлённый и ограниченный, Крот не понимает высоких стремлений и благородных порывов.

Ангельский характер

Дюймовочка обладает не только хорошенькой внешностью, но и такими качествами, как доброта и сострадание. Девочка жалеет брошенного мотылька и заботится о раненой ласточке — поит птичку водой и плетёт для неё тёплое покрывало из былинок. Когда выздоровевшая ласточка предлагает улететь вдвоём в зелёный лес, малышка отказывается — ей жалко бросать старушку-мышь. Этот эпизод говорит о том, что Дюймовочка умеет быть благодарной и не поступает эгоистично.

У девочки развито чувство прекрасного. Она замечает красоту природы и наслаждается ей. Солнечные блики на волнах, нежные лепестки цветов и птичьи трели делают малютку счастливой. Жить в тёмном кротовьем лабиринте и никогда не видеть солнышка для Дюймовочки равносильно смерти. Поэтому крошка не отказывается от второго предложения ласточки и улетает с птицей в тёплые края.

Долгая дорога к «своим»

По ходу развития сюжета героиня попадает в разные компании и везде чувствует себя чужой. Сначала она оказывается посреди водной стихии. Жабы внушают ей страх и отвращение — крошка хочет скрыться от похитителей и ей это удаётся.

Затем маленькую красавицу поднимает в воздух майский жук. Галантный ухажёр вводит Дюймовочку в «высшее общество», где высокомерные барышни обсуждают и критикуют её внешность. Девочка покидает жуков, ощущая себя неполноценной и уродливой. Здесь прослеживается параллель со знаменитой сказкой Андерсена «Гадкий утёнок». Её персонаж тоже чувствовал себя безобразным изгоем, попав на птичий двор, где его не принимали и шпыняли из-за необычной наружности.

В подземелье девчушка общается с мышью и кротом. Им нравятся её учтивость, трудолюбие и нежный голосок. Но обитатели нор вершат судьбу героини, не считаясь с её желаниями. Они хотят сделать милую гостью частью своего мира — сытого и безопасного, но тёмного и скучного. Стремясь насильно «причинить добро», благодетели оказываются немногим лучше жаб. Дюймовочка покидает их без сожаления.

Сидя на спине ласточки, девочка вновь попадает в воздушную стихию. Ей радостно, волнительно и интересно. Прилетев в тёплые края, птица сажает Дюймовочку на лепесток крупного белого цветка. Здесь крошка встречается с королём эльфов. Это прекрасное маленькое создание с прозрачными крылышками и золотой короной. Эльф влюбляется в очаровательную незнакомку и она отвечает взаимностью. Жених дарит избраннице драгоценную корону и лёгкие крылья — теперь красавица может порхать подобно бабочке. Юная невеста в восторге. Она получает новое весеннее имя — Майя и становится царицей цветов. Так, после долгих скитаний героиня находит своё место в жизни, обретает любовь и счастье.

Прообраз сказочной крошки

Исследователи андерсеновского творчества считают прототипом Дюймовочки Генриетту Вульф — подругу писателя, дочь начальника Морского кадетского корпуса. Генриетта была доброй, умной и чуткой девушкой, но ей нелегко жилось из-за физического недостатка — она была горбуньей карликового роста. Ганс часто переписывался с Генриеттой и ласково называл её «светлым эльфом». Крохотная девочка из волшебной истории во многом похожа на подругу Андерсена — миниатюрный рост, ангельский характер, ощущение одиночества и неприкаянности во враждебном обществе.

Генриетта временно переезжала в солнечную Италию, где чувствовала себя лучше, а сказочная героиня улетала с ласточкой в тёплые края, где её ждали эльфы. К сожалению, судьба маленькой горбуньи сложилась трагично: она погибла при кораблекрушении. Сказочный мир добрее и справедливее — здесь Дюймовочка получает награду за тяжёлые испытания и радуется жизни.

История персонажа

Однажды в Дании из распустившегося бутона цветка появилась на свет девочка не больше человеческого пальца. В доме своей матери Дюймовочка не прожила и двух дней – вскоре героине предстояло отправиться в невероятное путешествие, в котором произошло знакомство с добром и злом этого мира. Кто написал сказку о крохотной девочке, все знают с детсадовского возраста. Волшебную историю Ганса Христиана Андерсена не только читают малышам, но и ставят с детьми спектакли.

История создания

Сказка о Дюймовочке пришла к датской детворе в 1835 году в составе сборника «Сказки, рассказанные для детей». Когда именно была написана волшебная история о путешествиях маленькой девочки, так и осталось загадкой. Андерсен долго не отдавал в печать новые произведения – откладывал на редактирование.

При создании персонажа автор почерпнул вдохновение из легенд о маленьком народце, да еще и персонаж Шарля Перро Мальчик-с-пальчик находился на волне популярности. Но Дюймовочка может похвастать и реальным прототипом – им стала Генриетта Вульф, дочь датского переводчика Шекспира и Байрона. Невысокая горбатая женщина с ангельским характером дружила с Гансом. Прообраз нашелся и у крота: говорят, что этого персонажа сказочник списал со строгого школьного учителя.

Опубликованное произведение не вызвало восхищений у критиков. Литераторы остались недовольны простотой языка изложения и отсутствием нравоучений, ведь в те времена ценились назидательные нотки и ярко выраженная мораль. Зато читатели с восторгом приняли новую сказку Андерсена, а это важнее оценок знатоков литературы.

Десять лет «Дюймовочкой» зачитывались исключительно жители родной страны. Только в 1846 году приключениям маленькой девочки удалось попасть заграницу. Их перевели на английский, а затем и на другие европейские языки.

И всюду персонаж называли по-разному. Например, на родине героиню сказки величали Томмелисе, что в переводе означает «Лисе размером с дюйм», в Англии и во Франции – Тамбелина и Пуселина (и то и другое переводится как большой палец на руке), а в Чехии просто – Маленка.

До российских читателей персонаж дошел, как всегда, с опозданием. В конце 19 века за адаптацию сказок датского писателя взялись супруги Петр и Анна Ганзен, заботливо сохраняя элементы оригиналов. В первом переводе девочку звали Лизок-с-вершок, в Дюймовочку она превратилась позднее.

Биография и сюжет

Одна немолодая одинокая женщина мечтала о детях, но судьба лишила ее радости материнства. Помочь вызвалась фея, вручив ячменное зернышко, из которого вырос прекрасный цветок. В сердцевине бутона оказалась маленькая девочка ростом не больше человеческого пальца. Женщина смастерила дочке колыбельку из скорлупы грецкого ореха, но счастье было недолгим – однажды Дюймовочку приметила жаба и решила выкрасть ее, чтобы выдать замуж за своего сына.

Дорога к жабьему дому пролегала через озеро, по которому несчастную девочку везли на листе кувшинки. Рыбы, пожалевшие невольницу, перегрызли стебель водной лилии, а мотылек помчал прочь импровизированную лодочку. Однако по пути Дюймовочка вновь попала в плен, на сей раз к майскому жуку. На дереве собратья похитителя не оценили внешний вид находки – жукам девочка показалась очень некрасивой, и они решили бросить героиню в лесу на произвол судьбы.

Теплые весна и лето пролетели стремительно. С приходом первых осенних морозов Дюймовочка отправилась на поиски крова и набрела на норку полевой мыши. Хозяйка радушно приютила гостью, правда, заставив работать. А затем и вовсе, приглядевшись, увидела в девочке отличную невесту для старого и слепого, но состоятельного соседа-крота.

Обходя подземные владения жениха, Дюймовочка наткнулась на бездыханную ласточку. Оказалось, что птица не умерла, а просто потеряла силы от морозов. От заботы и ухода девочки ласточка ожила и в день бракосочетания с кротом унесла спасительницу в края, где всегда солнечно и тепло. Здесь крошечная красавица повстречала принца эльфов – такого же роста и приятной внешности. Принц предложил путешественнице руку и сердце. Так Дюймовочка стала королевой в стране эльфов и обрела новое имя – Майя.

Главная мысль, которую вложил в произведение автор, касается поиска предназначения и своего места в жизни. В этом сказка перекликается с еще одним литературным трудом Ганса Христиана Андерсена – «Гадкий утенок».

Характеристика героев проста и понятна. В каждого писатель вложил определенные черты и пороки, и получился целый мир с разношерстными жителями. Жаба становится олицетворением алчности и завистливости, жуки передают мысль о незначительности общественного мнения – у каждого собственное понятие о красоте. Рыбы обладают хитростью и смекалкой, глупая, но добрая мышь – символ бережливости и пуританства, а крот хоть и богат, однако скуп.

Хрупкая и нежная Дюймовочка проявила мужество, терпение, стойко перенесла выпавшие на ее долю испытания. Но среди читателей найдутся и те, кто видит в главном персонаже существо безвольное: девочка не в состоянии повлиять на события, единственный ее самостоятельный поступок – спасение ласточки, за что и получено вознаграждение в виде безмятежной и счастливой жизни. Впрочем, как считают исследователи, во времена создания сказки пассивный тип поведения, роль жертвы обстоятельств для женщин считались естественными.

Экранизации

Сказку Андерсена поэты и писатели перекраивали бесчисленное количество раз, странствия юной красавицы по свету встречаются даже в стихах. И, конечно, главные герои волшебного приключения поселились в десятках мультфильмов, а кинорежиссеры подарили миру четыре телевизионных фильма.

Российский кинематограф отличился двумя картинами, ставшими легендами. Это мультфильм «Дюймовочка», созданный Леонидом Амальриком в 1964 году. Голос девочке подарила Галина Новожилова, мышь озвучивала Елена Понсова, крота — Михаил Яншин. Над озвучкой картины работал даже Георгий Вицин, голосом которого заговорил Кузнечик. Сценарий мультика в некоторых моментах отличается от классической сказки: Дюймовочка в конце повествования не получила новое имя, крот обзавелся многочисленными друзьями, а также появился новый персонаж – рак, который помогает рыбам спасти девочку от жабы.

Любопытную интерпретацию андерсеновского творения представил режиссер Леонид Нечаев – музыкальный фильм 2007 года «Дюймовочка» получил россыпь призов на кинофестивалях. В главной роли выступила Татьяна Василишина. В актерский состав вошли Светлана Крючкова (Жаба), Лия Ахеджакова (Мышь), Леонид Мозговой (Крот), Альберт Филозов (Маэстро).

Авторы мультфильмов дали волю фантазии. Так, в 1994 году Дон Блут снял мультик, в котором отклонился от оригинального сюжета. К примеру, отвратительная жаба все же выдала Дюймовочку замуж за сына и заставляла девочку делать карьеру звезды эстрады, ведь шоу-бизнес – дело доходное.

Интересные факты

Дюймовочка вместе с другими героями сказок появляется на бракосочетании Шрека и Фионы в мультфильме «Шрек-2».

Образ крохотной девочки послужил вдохновением для скульпторов. Главному персонажу сказки Андерсена в Оденсе (Дания) посвящена скульптура, изображающая момент, когда Дюймовочка появляется в цветке. За пределами Дании тоже стоят бронзовые посвящения героине волшебной истории. Так, в 2006 году скульптура Дюймовочки украсила центральную аллею парка в Сочи.

В Англии живет девочка, которую прозвали Дюймовочкой. Шарлотта Гарсайд вошла в «Книгу рекордов Гиннеса» как самая маленькая девочка в мире. Она родилась с редким заболеванием – примордиальный нанизм. Эта форма низкорослости характеризуется еще и задержкой психического развития. В пятилетнем возрасте рост ребенка составлял 68 см, при этом Шарлотта обладала интеллектом трехлетнего малыша.

Цитаты

Советский мультфильм «Дюймовочка» 1964 года выпуска пестрит забавными фразами. Неудивительно, что вскоре после выхода картины на экраны они превратились в крылатые выражения:

«- Сжальтесь надо мной, хозяюшка! Не выдавайте меня замуж за Крота!

— Ты с ума сошла! Лучше нашего соседа тебе мужа не найти! Слепой, богатый – сокровище, а не муж!»

«Половина зернышка в день… В день — это немного. Женюсь! А в год? В году 365 дней. По половине зернышка в день — 182 с половиной зерна в год. В год получается не так-то уж и мало… Нет, не женюсь!»

«Так ведь жену кормить надо, а жены — они, знаете, какие прожорливые».

«Увы, мы должны расстаться! Потому что кроме меня вы никому не понравились! Желаю успеха!»

«Не хочу учиться, хочу жениться!»

«Ну вот, поели, теперь можно и поспать. Ну вот, поспали, теперь можно и поесть».

«Ничего-ничего! От счастья не умирают!»

«- Какое убожество!

— У нее только две ножки!

— У нее даже нет усиков!

— У нее даже есть талия!»

«Мне жаль вас! Как можно – с вашим художественным вкусом, и вдруг опуститься до такого убожества?! Ах, кружите меня, кружите!»

«- Ну, как, хороша невеста?

— Хороша! Жалко только, что она не зеленая.

— Ничего, поживет с нами — позеленеет».

| Дюймовочка | |

| Tommelise | |

|

|

| Создатель: | Андерсен, Ганс Христиан |

| Произведения: | Дюймовочка |

| Пол: | женский |

Дюймо́вочка (дат. Tommelise) — крохотная девочка, героиня одноимённой сказки датского поэта, путешественника и сказочника Х. К. Андерсена. Единственная девочка — член Клуба весёлых человечков.[1]

Сказка «Дюймовочка» впервые была опубликована в Дании в 1835 в составе второго тома «Сказок, рассказанных для детей». Как и большинство сказок Андерсена, эта сказка выдумана лично автором, а не заимствована «у народа».

Характер

Подобно Гадкому Утёнку и некоторым другим персонажам Андерсена, Дюймовочка является персонажем-«аутсайдером», ищущим своё место в обществе. Такие герои вызывают у автора симпатию.

Сюжет сказки

Одна женщина вырастила у себя в саду прекрасный цветок. Однажды женщина поцеловала бутон, после чего тот лопнул и в цветке оказалась крохотная прекрасная девочка. Женщина нарекла её Дюймовочкой, поскольку девочка была ростом не больше человеческого пальца, и стала опекать её.

Девочка была очень симпатичной. Это однажды заметила Лягушка. Она решила, что Дюймовочка может стать прекрасной парой для её сына. Дождавшись полуночи, лягушка выкрала девочку, чтобы доставить её к своему сыну. Сын лягушки был очарован красотой девочки. Чтобы она не смогла бежать, он поместил Дюймовочку на лист водной лилии. Однако на помощь девочке пришли рыбы, которые перегрызли ствол лилии, а Мотылёк, которому понравилась Дюймовочка, впрягся в её поясок и полетел, потянув за собой лист по воде. Пока Мотылёк тянул лист с Дюймовочкой, Майский жук перехватил её и понёс к себе. Мотылёк остался привязанным к листку. Дюймовочка очень жалела его — ведь он не мог сам освободиться, и ему грозила верная смерть.

Полевая Мышь и Дюймовочка (иллюстрация к сборнику «Young Folks Treasury» (1919))

Жук привёз Дюймовочку, чтобы показать своим знакомым и друзьям. Но девочка им не понравилась, ведь у жуков были свои понятия о красоте. Жук бросил девочку, потому что она ему сразу разонравилась. Бедная Дюймовочка осталась жить в лесу. Так она прожила всё лето, а как настала осень, девочка стала замерзать. К счастью, замёрзшую Дюймовочку обнаружила Полевая мышь, которая приютила её у себя в норке. Затем мышь решила выдать девочку замуж за своего богатого соседа — Крота. Крот был очень состоятелен и настолько же скуп. Но Дюймовочка понравилась ему, и он согласился подумать о женитьбе. Крот показал Дюймовочке свои подземные «дворцы» и богатства. В одной из галерей девочка обнаружила мёртвую ласточку. Однако оказалось, что ласточка была просто очень слаба. Дюймовочка втайне от Мыши и Крота стала заботиться о ней. Настала весна. Ласточка совсем оправилась и, поблагодарив Дюймовочку, вылетела наружу из галерей крота.

В то время, крот окончательно определился с желанием жениться. Мышь приказала девочке шить себе приданое. Дюймовочке было очень грустно и обидно, ведь ей очень не хотелось выходить за Крота. Наступил день свадьбы. Дюймовочка решила выйти в последний раз на свет и попрощаться с солнышком. В этот момент над полями пролетала та самая Ласточка. Она забрала Дюймовочку с собой в тёплые края, спасши её тем самым от скупого и расчётливого Крота.

В тёплых краях Дюймовочка поселилась в цветке. Она познакомилась с королём эльфов цветов, который был таким же маленьким, как и сама Дюймовочка. Эльф и Дюймовочка сразу же полюбили друг друга и стали мужем и женой. Так Дюймовочка стала королевой эльфов.

Экранизации и постановки

- Эндрю Ланг переименовал данную сказку в «Приключения Майи» в его одиннадцатом томе «Сказок оливковой Феи» (опубликована в 1907).

- Первый фильм «Дюймовочка» был черно-белым и выпущен в 1924 режиссёром Гербертом M. Доли.

- Дэнни Кэй исполнила песню «Дюймовочка», написанную Фрэнком Лессером, в фильме 1952 года об Андерсене.

- Лотте Рейнигер в 1954 выпустил короткий 10-минутный фильм о Дюймовочке.

- В 1964 году был снят советский мультфильм «Дюймовочка» Леонида Амальрика.

- Диафильм Дюймовочка, 1972 год

- Японская студия «Toei Animation» выпустила полнометражный аниме-мультфильм в 1978, под названием «Sekai Meisaku Dowa: Oyayubi Hime» (World’s Famous Children’s Stories: The Thumb Princess) с анимацией художника Осаму Тэдзука.

- Сериал про Дюймовочку, для домашнего просмотра, выпустила студия «Faerie Tale Theatre» (Сказочный театр) в 1984, с участием Кэрри Фишер и Уильяма Кэтта.

- История с красочным оформлением в студии «Rabbit Ears Productions» была выпущена в 1989 на видеокассете, аудиодиске, компакт-кассете (с рассказом в исполнении Келли МакГиллис) и в виде книги.

- Японская студия «Enoki Films» выпустила в 1992 26-серийный мультфильм, под названием Oyayubi Hime Monogatari (Рассказы о Дюймовочке).

- Компания Golden Films выпустила мультфильм о Дюймовочке (1993).

- В 1994 Дон Блут выпустил мультфильм о Дюймовочке, который имеет некоторые отклонения от классического авторского сюжета.

- В 2002 на DVD выпущен мультфильм «Приключения Дюймовочки и Мальчика С Пальчик».

- Дюймовочка появлялась в роли гостьи на свадьбе принцессы Фионы в мультфильме «Шрек-2» (2004).

- Hans Christian Andersen’s 200th Anniversary: The Fairy Tales, 2005, Denmark, The Netherlands, Jorgen Bing (Ганс Христиан Андерсен. Сказки, 2005, Дания, Нидерланды, Ёрген Бинг)

- В 2007 году вышел фильм «Дюймовочка» Леонида Нечаева по сценарию Инны Веткиной.

См. также

- Мальчик-с-пальчик

- Веселые человечки

Примечания

- ↑ Сайт журнала «Весёлые картинки»

| |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Клуб весёлых человечков | Карандаш • Самоделкин • Буратино • Чиполлино • Петрушка • Гурвинек • Незнайка • Дюймовочка | ||||||||||

| Произведения в которых встречаются отдельные весёлые человечки | |||||||||||

| Буратино |

|

||||||||||

| Гурвинек |

|

||||||||||

| Дюймовочка |

|

||||||||||

| Карандаш |

|

||||||||||

| Незнайка |

|

||||||||||

| Петрушка |

|

||||||||||

| Самоделкин |

|

||||||||||

| Чиполлино |

|

||||||||||

| Произведения в которых встречаются несколько весёлых человечков | |||||||||||

| Карандаш и Самоделкин |

|

||||||||||

| Все весёлые человечки, кроме Дюймовочки |

|

||||||||||

| Все весёлые человечки |

|