This article is about the Christian Bible. For the related Jewish text, see Hebrew Bible.

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites.[1] The second division of Christian Bibles is the New Testament, written in the Koine Greek language.

The Old Testament consists of many distinct books by various authors produced over a period of centuries.[2] Christians traditionally divide the Old Testament into four sections: the first five books or Pentateuch (corresponds to the Jewish Torah); the history books telling the history of the Israelites, from their conquest of Canaan to their defeat and exile in Babylon; the poetic and «Wisdom books» dealing, in various forms, with questions of good and evil in the world; and the books of the biblical prophets, warning of the consequences of turning away from God.

The books that compose the Old Testament canon and their order and names differ between various branches of Christianity. The canons of the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches comprise up to 49 books; the Catholic canon comprises 46 books; and the most common Protestant canon comprises 39 books.[3]

There are 39 books common to essentially all Christian canons. They correspond to the 24 books of the Tanakh, with some differences of order, and there are some differences in text. The additional number reflects the splitting of several texts (Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra–Nehemiah, and the Twelve Minor Prophets) into separate books in Christian Bibles. The books that are part of the Christian Old Testament but that are not part of the Hebrew canon are sometimes described as deuterocanonical. In general, Catholic and Orthodox churches include these books in the Old Testament. Most Protestant Bibles do not include the deuterocanonical books in their canon, but some versions of Anglican and Lutheran Bibles place such books in a separate section called apocrypha. These books are ultimately derived from the earlier Greek Septuagint collection of the Hebrew scriptures and are also Jewish in origin. Some are also contained in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Content[edit]

The Old Testament contains 39 (Protestant), 46 (Catholic), or more (Orthodox and other) books, divided, very broadly, into the Pentateuch (Torah), the historical books, the «wisdom» books and the prophets.[4]

The table below uses the spellings and names present in modern editions of the Christian Bible, such as the Catholic New American Bible Revised Edition and the Protestant Revised Standard Version and English Standard Version. The spelling and names in both the 1609–F10 Douay Old Testament (and in the 1582 Rheims New Testament) and the 1749 revision by Bishop Challoner (the edition currently in print used by many Catholics, and the source of traditional Catholic spellings in English) and in the Septuagint differ from those spellings and names used in modern editions which are derived from the Hebrew Masoretic text.[a]

For the Orthodox canon, Septuagint titles are provided in parentheses when these differ from those editions. For the Catholic canon, the Douaic titles are provided in parentheses when these differ from those editions. Likewise, the King James Version references some of these books by the traditional spelling when referring to them in the New Testament, such as «Esaias» (for Isaiah).

In the spirit of ecumenism more recent Catholic translations (e.g. the New American Bible, Jerusalem Bible, and ecumenical translations used by Catholics, such as the Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition) use the same «standardized» (King James Version) spellings and names as Protestant Bibles (e.g. 1 Chronicles as opposed to the Douaic 1 Paralipomenon, 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings instead of 1–4 Kings) in those books which are universally considered canonical, the protocanonicals.

The Talmud (the Jewish commentary on the scriptures) in Bava Batra 14b gives a different order for the books in Nevi’im and Ketuvim. This order is also cited in Mishneh Torah Hilchot Sefer Torah 7:15. The order of the books of the Torah is universal through all denominations of Judaism and Christianity.

The disputed books, included in most canons but not in others, are often called the Biblical apocrypha, a term that is sometimes used specifically to describe the books in the Catholic and Orthodox canons that are absent from the Jewish Masoretic Text and most modern Protestant Bibles. Catholics, following the Canon of Trent (1546), describe these books as deuterocanonical, while Greek Orthodox Christians, following the Synod of Jerusalem (1672), use the traditional name of anagignoskomena, meaning «that which is to be read.» They are present in a few historic Protestant versions; the German Luther Bible included such books, as did the English 1611 King James Version.[b]

Empty table cells indicate that a book is absent from that canon.

Pentateuch, corresponding to the Hebrew Torah

Historical books, most closely corresponding to the Hebrew Nevi’im (Prophets)

Wisdom books, most closely corresponding to the Hebrew Ketuvim (Writings)

Major Prophets

Twelve Minor Prophets

| Hebrew Bible(Tanakh)(24 books)[c] | ProtestantOld Testament(39 books) | CatholicOld Testament(46 books) | Eastern OrthodoxOld Testament(49 books) | Original language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torah (Law) |

Pentateuch or the Five books of Moses |

|||

| Bereshit | Genesis | Genesis | Genesis | Hebrew |

| Shemot | Exodus | Exodus | Exodus | Hebrew |

| Vayikra | Leviticus | Leviticus | Leviticus | Hebrew |

| Bamidbar | Numbers | Numbers | Numbers | Hebrew |

| Devarim | Deuteronomy | Deuteronomy | Deuteronomy | Hebrew |

| Nevi’im (Prophets) |

Historical books |

|||

| Yehoshua | Joshua | Joshua (Josue) | Joshua (Iesous) | Hebrew |

| Shoftim | Judges | Judges | Judges | Hebrew |

| Rut (Ruth)[d] | Ruth | Ruth | Ruth | Hebrew |

| Shmuel | 1 Samuel | 1 Samuel (1 Kings)[e] | 1 Samuel (1 Kingdoms)[f] | Hebrew |

| 2 Samuel | 2 Samuel (2 Kings)[e] | 2 Samuel (2 Kingdoms)[f] | Hebrew | |

| Melakhim | 1 Kings | 1 Kings (3 Kings)[e] | 1 Kings (3 Kingdoms)[f] | Hebrew |

| 2 Kings | 2 Kings (4 Kings)[e] | 2 Kings (4 Kingdoms)[f] | Hebrew | |

| Divrei Hayamim (Chronicles)[d] | 1 Chronicles | 1 Chronicles (1 Paralipomenon) | 1 Chronicles (1 Paralipomenon) | Hebrew |

| 2 Chronicles | 2 Chronicles (2 Paralipomenon) | 2 Chronicles (2 Paralipomenon) | Hebrew | |

| 1 Esdras[g][h] | Greek | |||

| Ezra–Nehemiah[d] | Ezra | Ezra (1 Esdras) | Ezra (2 Esdras)[f][i][j] | Hebrew and Aramaic |

| Nehemiah | Nehemiah (2 Esdras) | Nehemiah (2 Esdras)[f][i] | Hebrew | |

| Tobit (Tobias) | Tobit[g] | Aramaic and Hebrew | ||

| Judith | Judith[g] | Hebrew | ||

| Ester (Esther)[d] | Esther | Esther[k] | Esther[k] | Hebrew |

| 1 Maccabees (1 Machabees)[l] | 1 Maccabees[g] | Hebrew and Greek[m] | ||

| 2 Maccabees (2 Machabees)[l] | 2 Maccabees[g] | Greek | ||

| 3 Maccabees[g] | Greek | |||

| 3 Esdras[g] | Greek | |||

| 4 Maccabees[n] | Greek | |||

| Ketuvim (Writings) | Wisdom books | |||

| Iyov (Job)[d] | Job | Job | Job | Hebrew |

| Tehillim (Psalms)[d] | Psalms | Psalms | Psalms[o] | Hebrew |

| Prayer of Manasseh[p] | Greek | |||

| Mishlei (Proverbs)[d] | Proverbs | Proverbs | Proverbs | Hebrew |

| Qohelet (Ecclesiastes)[d] | Ecclesiastes | Ecclesiastes | Ecclesiastes | Hebrew |

| Shir Hashirim (Song of Songs)[d] | Song of Solomon | Song of Songs (Canticle of Canticles) | Song of Songs (Aisma Aismaton) | Hebrew |

| Wisdom | Wisdom[g] | Greek | ||

| Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) | Sirach[g] | Hebrew | ||

| Nevi’im (Latter Prophets) | Major Prophets | |||

| Yeshayahu | Isaiah | Isaiah (Isaias) | Isaiah | Hebrew |

| Yirmeyahu | Jeremiah | Jeremiah (Jeremias) | Jeremiah | Hebrew |

| Eikhah (Lamentations)[d] | Lamentations | Lamentations | Lamentations | Hebrew |

| Baruch[q] | Baruch[q][g] | Hebrew[7] | ||

| Letter of Jeremiah[r][g] | Greek (majority view)[s] | |||

| Yekhezqel | Ezekiel | Ezekiel (Ezechiel) | Ezekiel | Hebrew |

| Daniyyel (Daniel)[d] | Daniel | Daniel[t] | Daniel[t] | Aramaic and Hebrew |

| Twelve Minor Prophets | ||||

| The TwelveorTrei Asar | Hosea | Hosea (Osee) | Hosea | Hebrew |

| Joel | Joel | Joel | Hebrew | |

| Amos | Amos | Amos | Hebrew | |

| Obadiah | Obadiah (Abdias) | Obadiah | Hebrew | |

| Jonah | Jonah (Jonas) | Jonah | Hebrew | |

| Micah | Micah (Michaeas) | Micah | Hebrew | |

| Nahum | Nahum | Nahum | Hebrew | |

| Habakkuk | Habakkuk (Habacuc) | Habakkuk | Hebrew | |

| Zephaniah | Zephaniah (Sophonias) | Zephaniah | Hebrew | |

| Haggai | Haggai (Aggaeus) | Haggai | Hebrew | |

| Zechariah | Zechariah (Zacharias) | Zechariah | Hebrew | |

| Malachi | Malachi (Malachias) | Malachi | Hebrew |

Several of the books in the Eastern Orthodox canon are also found in the appendix to the Latin Vulgate, formerly the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church.

|

Books in the Appendix to the Vulgate Bible |

|

| Name in Vulgate | Name in Eastern Orthodox use |

|---|---|

| 3 Esdras | 1 Esdras |

| 4 Esdras | 2 Esdras |

| Prayer of Manasseh | Prayer of Manasseh |

| Psalm of David when he slew Goliath (Psalm 151) | Psalm 151 |

Historicity[edit]

Early scholarship[edit]

Some of the stories of the Pentateuch may derive from older sources. American science writer Homer W. Smith points out similarities between the Genesis creation narrative and that of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, such as the inclusion of the creation of the first man (Adam/Enkidu) in the Garden of Eden, a tree of knowledge, a tree of life, and a deceptive serpent.[8] Scholars such as Andrew R. George point out the similarity of the Genesis flood narrative and the Gilgamesh flood myth.[9][u] Similarities between the origin story of Moses and that of Sargon of Akkad were noted by psychoanalyst Otto Rank in 1909[13] and popularized by 20th century writers, such as H. G. Wells and Joseph Campbell.[14][15] Jacob Bronowski writes that, «the Bible is … part folklore and part record. History is … written by the victors, and the Israelis, when they burst through [Jericho (c. 1400 BC)], became the carriers of history.»[16]

Recent scholarship[edit]

In 2007, a scholar of Judaism Lester L. Grabbe explained that earlier biblical scholars such as Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918) could be described as ‘maximalist’, accepting biblical text unless it has been disproven. Continuing in this tradition, both «the ‘substantial historicity’ of the patriarchs» and «the unified conquest of the land» were widely accepted in the United States until about the 1970s. Contrarily, Grabbe says that those in his field now «are all minimalists – at least, when it comes to the patriarchal period and the settlement. … [V]ery few are willing to operate [as maximalists].»[17]

Composition[edit]

The first five books—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, book of Numbers and Deuteronomy—reached their present form in the Persian period (538–332 BC), and their authors were the elite of exilic returnees who controlled the Temple at that time.[18] The books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings follow, forming a history of Israel from the Conquest of Canaan to the Siege of Jerusalem c. 587 BC. There is a broad consensus among scholars that these originated as a single work (the so-called «Deuteronomistic History») during the Babylonian exile of the 6th century BC.[19]

The two Books of Chronicles cover much the same material as the Pentateuch and Deuteronomistic history and probably date from the 4th century BC.[20] Chronicles, and Ezra–Nehemiah, was probably finished during the 3rd century BC.[21] Catholic and Orthodox Old Testaments contain two (Catholic Old Testament) to four (Orthodox) Books of Maccabees, written in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC.

These history books make up around half the total content of the Old Testament. Of the remainder, the books of the various prophets—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the twelve «minor prophets»—were written between the 8th and 6th centuries BC, with the exceptions of Jonah and Daniel, which were written much later.[22] The «wisdom» books—Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Psalms, Song of Solomon—have various dates: Proverbs possibly was completed by the Hellenistic time (332–198 BC), though containing much older material as well; Job completed by the 6th century BC; Ecclesiastes by the 3rd century BC.[23]

Themes[edit]

Throughout the Old Testament, God is consistently depicted as the one who created the world. Although the God of the Old Testament is not consistently presented as the only God who exists, he is always depicted as the only God whom Israel is to worship, or the one «true God», that only Yahweh (or YHWH) is Almighty.[24]

The Old Testament stresses the special relationship between God and his chosen people, Israel, but includes instructions for proselytes as well. This relationship is expressed in the biblical covenant (contract)[25][26][27][28][29][30] between the two, received by Moses. The law codes in books such as Exodus and especially Deuteronomy are the terms of the contract: Israel swears faithfulness to God, and God swears to be Israel’s special protector and supporter.[24] However, The Jewish Study Bible denies that the word covenant (brit in Hebrew) means «contract»; in the ancient Near East, a covenant would have been sworn before the gods, who would be its enforcers. As God is part of the agreement, and not merely witnessing it, The Jewish Study Bible instead interprets the term to refer to a pledge.[31]

Further themes in the Old Testament include salvation, redemption, divine judgment, obedience and disobedience, faith and faithfulness, among others. Throughout there is a strong emphasis on ethics and ritual purity, both of which God demands, although some of the prophets and wisdom writers seem to question this, arguing that God demands social justice above purity, and perhaps does not even care about purity at all. The Old Testament’s moral code enjoins fairness, intervention on behalf of the vulnerable, and the duty of those in power to administer justice righteously. It forbids murder, bribery and corruption, deceitful trading, and many sexual misdemeanours. All morality is traced back to God, who is the source of all goodness.[32]

The problem of evil plays a large part in the Old Testament. The problem the Old Testament authors faced was that a good God must have had just reason for bringing disaster (meaning notably, but not only, the Babylonian exile) upon his people. The theme is played out, with many variations, in books as different as the histories of Kings and Chronicles, the prophets like Ezekiel and Jeremiah, and in the wisdom books like Job and Ecclesiastes.[32]

Formation[edit]

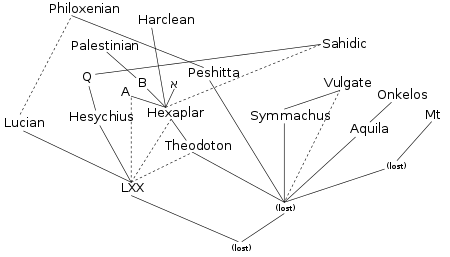

The interrelationship between various significant ancient manuscripts of the Old Testament, according to the Encyclopaedia Biblica (1903). Some manuscripts are identified by their siglum. LXX here denotes the original Septuagint.

The process by which scriptures became canons and Bibles was a long one, and its complexities account for the many different Old Testaments which exist today. Timothy H. Lim, a professor of Hebrew Bible and Second Temple Judaism at the University of Edinburgh, identifies the Old Testament as «a collection of authoritative texts of apparently divine origin that went through a human process of writing and editing.»[2] He states that it is not a magical book, nor was it literally written by God and passed to mankind. By about the 5th century BC, Jews saw the five books of the Torah (the Old Testament Pentateuch) as having authoritative status; by the 2nd century BC, the Prophets had a similar status, although without quite the same level of respect as the Torah; beyond that, the Jewish scriptures were fluid, with different groups seeing authority in different books.[33]

Greek[edit]

Hebrew texts began to be translated into Greek in Alexandria in about 280 and continued until about 130 BC.[34] These early Greek translations – supposedly commissioned by Ptolemy Philadelphus – were called the Septuagint (Latin for ‘Seventy’) from the supposed number of translators involved (hence its abbreviation «LXX»). This Septuagint remains the basis of the Old Testament in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[35]

It varies in many places from the Masoretic Text and includes numerous books no longer considered canonical in some traditions: 1 and 2 Esdras, Judith, Tobit, 3 and 4 Maccabees, the Book of Wisdom, Sirach, and Baruch.[36] Early modern biblical criticism typically explained these variations as intentional or ignorant corruptions by the Alexandrian scholars, but most recent scholarship holds it is simply based on early source texts differing from those later used by the Masoretes in their work.

The Septuagint was originally used by Hellenized Jews whose knowledge of Greek was better than Hebrew. However, the texts came to be used predominantly by gentile converts to Christianity and by the early Church as its scripture, Greek being the lingua franca of the early Church. The three most acclaimed early interpreters were Aquila of Sinope, Symmachus the Ebionite, and Theodotion; in his Hexapla, Origen placed his edition of the Hebrew text beside its transcription in Greek letters and four parallel translations: Aquila’s, Symmachus’s, the Septuagint’s, and Theodotion’s. The so-called «fifth» and «sixth editions» were two other Greek translations supposedly miraculously discovered by students outside the towns of Jericho and Nicopolis: these were added to Origen’s Octapla.[37]

In 331, Constantine I commissioned Eusebius to deliver fifty Bibles for the Church of Constantinople. Athanasius[38] recorded Alexandrian scribes around 340 preparing Bibles for Constans. Little else is known, though there is plenty of speculation. For example, it is speculated that this may have provided motivation for canon lists and that Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus are examples of these Bibles. Together with the Peshitta and Codex Alexandrinus, these are the earliest extant Christian Bibles.[39] There is no evidence among the canons of the First Council of Nicaea of any determination on the canon. However, Jerome (347–420), in his Prologue to Judith, claims that the Book of Judith was «found by the Nicene Council to have been counted among the number of the Sacred Scriptures».[40]

Latin[edit]

In Western Christianity or Christianity in the Western half of the Roman Empire, Latin had displaced Greek as the common language of the early Christians, and in 382 AD Pope Damasus I commissioned Jerome, the leading scholar of the day, to produce an updated Latin Bible to replace the Vetus Latina, which was a Latin translation of the Septuagint. Jerome’s work, called the Vulgate, was a direct translation from Hebrew, since he argued for the superiority of the Hebrew texts in correcting the Septuagint on both philological and theological grounds.[41] His Vulgate Old Testament became the standard Bible used in the Western Church, specifically as the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate, while the Churches in the East continued, and continue, to use the Septuagint.[42]

Jerome, however, in the Vulgate’s prologues describes some portions of books in the Septuagint not found in the Hebrew Bible as being non-canonical (he called them apocrypha);[43] for Baruch, he mentions by name in his Prologue to Jeremiah and notes that it is neither read nor held among the Hebrews, but does not explicitly call it apocryphal or «not in the canon».[44] The Synod of Hippo (in 393), followed by the Council of Carthage (397) and the Council of Carthage (419), may be the first council that explicitly accepted the first canon which includes the books that did not appear in the Hebrew Bible;[45] the councils were under significant influence of Augustine of Hippo, who regarded the canon as already closed.[46]

Protestant canon[edit]

In the 16th century, the Protestant reformers sided with Jerome; yet although most Protestant Bibles now have only those books that appear in the Hebrew Bible, the order is that of the Greek Bible.[47]

Rome then officially adopted a canon, the Canon of Trent, which is seen as following Augustine’s Carthaginian Councils[48] or the Council of Rome,[49][50] and includes most, but not all, of the Septuagint (3 Ezra and 3 and 4 Maccabees are excluded);[51] the Anglicans after the English Civil War adopted a compromise position, restoring the 39 Articles and keeping the extra books that were excluded by the Westminster Confession of Faith, both for private study and for reading in churches but not for establishing any doctrine, while Lutherans kept them for private study, gathered in an appendix as biblical apocrypha.[47]

Other versions[edit]

While the Hebrew, Greek and Latin versions of the Hebrew Bible are the best known Old Testaments, there were others. At much the same time as the Septuagint was being produced, translations were being made into Aramaic, the language of Jews living in Palestine and the Near East and likely the language of Jesus: these are called the Aramaic Targums, from a word meaning «translation», and were used to help Jewish congregations understand their scriptures.[52]

For Aramaic Christians there was a Syriac translation of the Hebrew Bible called the Peshitta, as well as versions in Coptic (the everyday language of Egypt in the first Christian centuries, descended from ancient Egyptian), Ethiopic (for use in the Ethiopian church, one of the oldest Christian churches), Armenian (Armenia was the first to adopt Christianity as its official religion), and Arabic.[52]

Christian theology[edit]

Christianity is based on the belief that the historical Jesus is also the Christ, as in the Confession of Peter. This belief is in turn based on Jewish understandings of the meaning of the Hebrew term Messiah, which, like the Greek «Christ», means «anointed». In the Hebrew Scriptures, it describes a king anointed with oil on his accession to the throne: he becomes «The LORD‘s anointed» or Yahweh’s Anointed.

By the time of Jesus, some Jews expected that a flesh and blood descendant of David (the «Son of David») would come to establish a real Jewish kingdom in Jerusalem, instead of the Roman province of Judaea.[53] Others stressed the Son of Man, a distinctly other-worldly figure who would appear as a judge at the end of time. Some expounded a synthesised view of both positions, where a messianic kingdom of this world would last for a set period and be followed by the other-worldly age or World to Come.

Some[who?] thought the Messiah was already present, but unrecognised due to Israel’s sins; some[who?] thought that the Messiah would be announced by a forerunner, probably Elijah (as promised by the prophet Malachi, whose book now ends the Old Testament and precedes Mark’s account of John the Baptist). However, no view of the Messiah as based on the Old Testament predicted a Messiah who would suffer and die for the sins of all people.[53] The story of Jesus’ death, therefore, involved a profound shift in meaning from the Old Testament tradition.[54]

The name «Old Testament» reflects Christianity’s understanding of itself as the fulfilment of Jeremiah’s prophecy of a New Covenant (which is similar to «testament» and often conflated) to replace the existing covenant between God and Israel (Jeremiah 31:31)[55].[1] The emphasis, however, has shifted from Judaism’s understanding of the covenant as a racially- or tribally-based pledge between God and the Jewish people, to one between God and any person of faith who is «in Christ».[56]

See also[edit]

- Abrogation of Old Covenant laws

- Biblical and Quranic narratives

- Book of Job in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

- Criticism of the Bible

- Expounding of the Law

- Law and Gospel

- List of ancient legal codes

- List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts

- Marcion of Sinope

- Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible

- Quotations from the Hebrew Bible in the New Testament

- Timeline of Genesis patriarchs

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Generally due to derivation from transliterations of names used in the Latin Vulgate in the case of Catholicism, and from transliterations of the Greek Septuagint in the case of the Orthodox (as opposed to the derivation of translations, instead of transliterations, of Hebrew titles) such Ecclesiasticus (DRC) instead of Sirach (LXX) or Ben Sira (Hebrew), Paralipomenon (Greek, meaning «things omitted») instead of Chronicles, Sophonias instead of Zephaniah, Noe instead of Noah, Henoch instead of Enoch, Messias instead of Messiah, Sion instead of Zion, etc.

- ^ The foundational Thirty-Nine Articles of Anglicanism, in Article VI, asserts these disputed books are not used «to establish any doctrine», but «read for example of life.» Although the Biblical Apocrypha are still used in Anglican Liturgy,[5] the modern trend is to not even print the Old Testament Apocrypha in editions of Anglican-used Bibles

- ^ The 24 books of the Hebrew Bible are the same as the 39 books of the Protestant Old Testament, only divided and ordered differently: the books of the Minor Prophets are in Christian Bibles twelve different books, and in Hebrew Bibles, one book called «The Twelve». Likewise, Christian Bibles divide the Books of Kingdoms into four books, either 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings or 1–4 Kings: Jewish Bibles divide these into two books. The Jews likewise keep 1–2 Chronicles/Paralipomenon as one book. Ezra and Nehemiah are likewise combined in the Jewish Bible, as they are in many Orthodox Bibles, instead of divided into two books, as per the Catholic and Protestant tradition.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k This book is part of the Ketuvim, the third section of the Jewish canon. There is a different order in Jewish canon than in Christian canon.

- ^ a b c d The books of Samuel and Kings are often called First through Fourth Kings in the Catholic tradition, much like the Orthodox.

- ^ a b c d e f Names in parentheses are the Septuagint names and are often used by the Orthodox Christians.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k One of 11 deuterocanonical books in the Russian Synodal Bible.

- ^ 2 Esdras in the Russian Synodal Bible.

- ^ a b Some Eastern Orthodox churches follow the Septuagint and Hebrew Bibles by considering the books of Ezra and Nehemiah as one book.

- ^ 1 Esdras in the Russian Synodal Bible.

- ^ a b The Catholic and Orthodox Book of Esther includes 103 verses not in the Protestant Book of Esther.

- ^ a b The Latin Vulgate, Douay–Rheims, and Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition place First and Second Maccabees after Malachi; other Catholic translations place them after Esther.

- ^ 1 Maccabees is hypothesized by most scholars to have been originally written in Hebrew; however, if it was, the original Hebrew has been lost. The surviving Septuagint version is in Greek.[6]

- ^ In Greek Bibles, 4 Maccabees is found in the appendix.

- ^ Eastern Orthodox churches include Psalm 151 and the Prayer of Manasseh, not present in all canons.

- ^ Part of 2 Paralipomenon in the Russian Synodal Bible.

- ^ a b In Catholic Bibles, Baruch includes a sixth chapter called the Letter of Jeremiah. Baruch is not in the Protestant Bible or the Tanakh.

- ^ Eastern Orthodox Bibles have the books of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah separate.

- ^ Hebrew (minority view); see Letter of Jeremiah for details.

- ^ a b In Catholic and Orthodox Bibles, Daniel includes three sections not included in Protestant Bibles. The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children are included between Daniel 3:23–24. Susanna is included as Daniel 13. Bel and the Dragon is included as Daniel 14. These are not in the Protestant Old Testament.

- ^ The latter flood myth appears in a Babylonian copy dating to 700 BC,[10] though many scholars believe that this was probably copied from the Akkadian Atra-Hasis, which dates to the 18th century BC.[11] George points out that the modern version of the Epic of Gilgamesh was compiled by Sîn-lēqi-unninni, who lived sometime between 1300 and 1000 BC.[12]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Jones 2000, p. 215.

- ^ a b Lim, Timothy H. (2005). The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 41.

- ^ Barton 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Boadt 1984, pp. 11, 15–16.

- ^ The Apocrypha, Bridge of the Testaments (PDF), Orthodox Anglican, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-05,

Two of the hymns used in the American Prayer Book office of Morning Prayer, the Benedictus es and Benedicite, are taken from the Apocrypha. One of the offertory sentences in Holy Communion comes from an apocryphal book (Tob. 4: 8–9). Lessons from the Apocrypha are regularly appointed to be reason Sunday, Sunday, and the special services of Morning and Evening Prayer. There are altogether 111 such lessons in the latest revised American Prayer Book Lectionary [Books used are: II Esdras, Tobit, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, Three Holy Children, and I Maccabees.]

- ^ Goldstein, Jonathan A. (1976). I Maccabees. The Anchor Bible Series. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. p. 14. ISBN 0-385-08533-8.

- ^ Driver, Samuel Rolles (1911). «Bible» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 849–894, see page 853, third para.

Jeremiah…..were first written down in 604 B.C. by his friend and amanuensis Baruch, and the roll thus formed must have formed the nucleus of the present book. Some of the reports of Jeremiah’s prophecies, and especially the biographical narratives, also probably have Baruch for their author. But the chronological disorder of the book, and other indications, show that Baruch could not have been the compiler of the book

- ^ Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 117.

- ^ George, A. R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-927841-1.

- ^ Cline, Eric H. (2007). From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. National Geographic. pp. 20–27. ISBN 978-1-4262-0084-7.

- ^ Tigay, Jeffrey H. (2002) [1982]. The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. pp. 23, 218, 224, 238. ISBN 9780865165465.

- ^ The Epic of Gilgamesh. Translated by Andrew R. George (reprinted ed.). London: Penguin Books. 2003 [1999]. pp. ii, xxiv–v. ISBN 0-14-044919-1.

- ^ Otto Rank (1914). The myth of the birth of the hero: a psychological interpretation of mythology. English translation by Drs. F. Robbins and Smith Ely Jelliffe. New York: The Journal of nervous and mental disease publishing company.

- ^ Wells, H. G. (1961) [1937]. The Outline of History: Volume 1. Doubleday. pp. 206, 208, 210, 212.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph (1964). The Masks of God, Vol. 3: Occidental Mythology. p. 127.

- ^ Bronowski, Jacob (1990) [1973]. The Ascent of Man. London: BBC Books. pp. 72–73, 77. ISBN 978-0-563-20900-3.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (2007-10-25). «Some Recent Issues in the Study of the History of Israel». Understanding the History of Ancient Israel. British Academy. pp. 57–58. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197264010.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-726401-0.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 1998, p. 184.

- ^ Rogerson 2003, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Coggins 2003, p. 282.

- ^ Grabbe 2003, pp. 213–14.

- ^ Miller 1987, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Crenshaw 2010, p. 5.

- ^ a b Barton 2001, p. 9: «4. Covenant and Redemption. It is a central point in many OT texts that the creator God YHWH is also in some sense Israel’s special god, who at some point in history entered into a relationship with his people that had something of the nature of a contract. Classically this contract or covenant was entered into at Sinai, and Moses was its mediator.»

- ^ Coogan 2008, p. 106.

- ^ Ferguson 1996, p. 2.

- ^ Ska 2009, p. 213.

- ^ Berman 2006, p. unpaginated: «At this juncture, however, God is entering into a «treaty» with the Israelites, and hence the formal need within the written contract for the grace of the sovereign to be documented.30 30. Mendenhall and Herion, «Covenant,» p. 1183.»

- ^ Levine 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Hayes 2006.

- ^ Berlin & Brettler 2014, p. PT194: 6.17-22: Further introduction and a pledge. 18: This v. records the first mention of the covenant («brit») in the Tanakh. In the ancient Near East, a covenant was an agreement that the parties swore before the gods, and expected the gods to enforce. In this case, God is Himself a party to the covenant, which is more like a pledge than an agreement or contract (this was sometimes the case in the ancient Near East as well). The covenant with Noah will receive longer treatment in 9.1-17.

- ^ a b Barton 2001, p. 10.

- ^ Brettler 2005, p. 274.

- ^ Gentry 2008, p. 302.

- ^ Würthwein 1995.

- ^ Jones 2000, p. 216.

- ^ Cave, William. A complete history of the lives, acts, and martyrdoms of the holy apostles, and the two evangelists, St. Mark and Luke, Vol. II. Wiatt (Philadelphia), 1810. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ^ Apol. Const. 4

- ^ The Canon Debate, pp. 414–15, for the entire paragraph

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Book of Judith» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Canonicity: «…» the Synod of Nicaea is said to have accounted it as Sacred Scripture» (Praef. in Lib.). No such declaration indeed is to be found in the Canons of Nicaea, and it is uncertain whether St. Jerome is referring to the use made of the book in the discussions of the council, or whether he was misled by some spurious canons attributed to that council».

- ^ Rebenich, S., Jerome (Routledge, 2013), p. 58. ISBN 9781134638444

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 91–99.

- ^ «The Bible». www.thelatinlibrary.com.

- ^ Kevin P. Edgecomb, Jerome’s Prologue to Jeremiah, archived from the original on 2013-12-31, retrieved 2015-11-30

- ^ McDonald & Sanders, editors of The Canon Debate, 2002, chapter 5: The Septuagint: The Bible of Hellenistic Judaism by Albert C. Sundberg Jr., page 72, Appendix D-2, note 19.

- ^ Everett Ferguson, «Factors leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon», in The Canon Debate. eds. L. M. McDonald & J. A. Sanders (Hendrickson, 2002) p. 320; F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Intervarsity Press, 1988) p. 230; cf. Augustine, De Civitate Dei 22.8

- ^ a b Barton 1997, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Philip Schaff, «Chapter IX. Theological Controversies, and Development of the Ecumenical Orthodoxy», History of the Christian Church, CCEL

- ^ Lindberg (2006). A Brief History of Christianity. Blackwell Publishing. p. 15.

- ^ F.L. Cross, E.A. Livingstone, ed. (1983), The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 232

- ^ Soggin 1987, p. 19.

- ^ a b Würthwein 1995, pp. 79–90, 100–4.

- ^ a b Farmer 1991, pp. 570–71.

- ^ Juel 2000, pp. 236–39.

- ^ Jeremiah 31:31

- ^ Herion 2000, pp. 291–92.

General and cited references[edit]

- Bandstra, Barry L (2004), Reading the Old Testament: an introduction to the Hebrew Bible, Wadsworth, ISBN 978-0-495-39105-0

- Barton, John (1997), How the Bible Came to Be, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 978-0-664-25785-9

- ——— (2001), «Introduction to the Old Testament», in Muddiman, John; Barton, John (eds.), Bible Commentary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-875500-5

- Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi, eds. (2014-10-17). The Jewish Study Bible: Second Edition. Oxford University Press. p. PT194. ISBN 978-0-19-939387-9.

- Berman, Joshua A. (Summer 2006). «God’s Alliance with Man». Azure: Ideas for the Jewish Nation (25). ISSN 0793-6664. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1998), «The Pentateuch», in Barton, John (ed.), The Cambridge companion to biblical interpretation, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48593-7

- Boadt, Lawrence (1984), Reading the Old Testament: an introduction, Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0-8091-2631-6

- Brettler, Marc Zvi (2005), How to read the Bible, Jewish Publication Society, ISBN 978-0-8276-1001-9

- Bultman, Christoph (2001), «Deuteronomy», in Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.), Oxford Bible Commentary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-875500-5

- Coggins, Richard J (2003), «1 and 2 Chronicles», in Dunn, James DG; Rogerson, John William (eds.), Commentary on the Bible, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0

- Coogan, Michael David (2008-11-01). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context. Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-19-533272-8..

- Crenshaw, James L (2010), Old Testament wisdom: an introduction, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 978-0-664-23459-1

- Davies, GI (1998), «Introduction to the Pentateuch», in Barton, John (ed.), Oxford Bible Commentary, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-875500-5

- Dines, Jennifer M (2004), «The Septuagint», Continuum, ISBN 978-0-567-08464-4

- Farmer, Ron (1991), «Messiah/Christ», in Mills, Watson E; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.), Mercer dictionary of the Bible, Mercer University Press, ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7

- Ferguson, Everett (1996). The Church of Christ: A Biblical Ecclesiology for Today. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8028-4189-6.

- Gentry, Peter R (2008), «Old Greek and Later Revisors», in Sollamo, Raija; Voitila, Anssi; Jokiranta, Jutta (eds.), Scripture in transition, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-16582-3

- Grabbe, Lester L (2003), «Ezra», in Dunn, James DG; Rogerson, John William (eds.), Commentary on the Bible, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0

- Hasel, Gerhard F (1991), Old Testament theology: basic issues in the current debate, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-0537-9

- Hayes, Christine (2006). «Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible): Lecture 6 Transcript». Open Yale Courses. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- Herion, Gary A (2000), «Covenant», in Freedman, David Noel (ed.), Dictionary of the Bible, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2

- Jobes, Karen H; Silva, Moises (2005), Invitation to the Septuagint, Baker Academic

- Jones, Barry A (2000), «Canon of the Old Testament», in Freedman, David Noel (ed.), Dictionary of the Bible, William B Eerdmans, ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2

- Juel, Donald (2000), «Christ», in Freedman, David Noel (ed.), Dictionary of the Bible, William B Eerdmans, ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2001). «Covenant and Law, Part I (Exodus 19–40, Leviticus, Deuteronomy). Lecture 10» (PDF). The Old Testament. Course Guidebook. The Great Courses. p. 46.

- Lim, Timothy H. (2005). The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McLay, Tim (2003), The use of the Septuagint in New Testament research, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-6091-0

- Miller, John W (2004), How the Bible came to be, Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0-8091-4183-8

- Miller, John W (1987), Meet the prophets: a beginner’s guide to the books of the biblical prophets, Paulist Press, ISBN 978-0-8091-2899-0

- Miller, Stephen R. (1994), Daniel, B&H Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8054-0118-9

- Rogerson, John W (2003), «Deuteronomy», in Dunn, James DG; Rogerson, John William (eds.), Commentary on the Bible, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0

- Sailhamer, John H. (1992), The Pentateuch As Narrative, Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-57421-7

- Schniedewind, William M (2004), How the Bible Became a Book, Cambridge, ISBN 978-0-521-53622-6

- Ska, Jean Louis (2009). The Exegesis of the Pentateuch: Exegetical Studies and Basic Questions. Mohr Siebeck. p. 213. ISBN 978-3-16-149905-0.

- Soggin, J. Alberto (1987), Introduction to the Old Testament, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 978-0-664-22156-0

- Stuart, Douglas (1987), Hosea-Jonah, Thomas Nelson, ISBN 978-0-8499-0230-7

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995), The text of the Old Testament: an introduction to the Biblia Hebraica, William B Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-0788-5

Further reading[edit]

- Anderson, Bernhard. Understanding the Old Testament. ISBN 0-13-948399-3

- Bahnsen, Greg, et al., Five Views on Law and Gospel (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1993).

- Berkowitz, Ariel; Berkowitz, D’vorah (2004), Torah Rediscovered (4th ed.), Shoreshim, ISBN 978-0-9752914-0-5.

- Dever, William G. (2003), Who Were the Early Israelites?, Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-0975-9.

- Driver, Samuel Rolles (1911). «Bible» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 849–894.

- Hill, Andrew; Walton, John (2000), A Survey of the Old Testament (2nd ed.), Grand Rapids: Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-22903-2.

- Kuntz, John Kenneth (1974), The People of Ancient Israel: an introduction to Old Testament Literature, History, and Thought, Harper & Row, ISBN 978-0-06-043822-7.

- Lancaster, D Thomas (2005), Restoration: Returning the Torah of God to the Disciples of Jesus, Littleton : First Fruits of Zion.

- Papadaki-Oekland, Stella (2009), Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts of the Book of Job, ISBN 978-2-503-53232-5.

- von Rad, Gerhard (1982–1984), Theologie des Alten Testaments [Theology of the Old Testament] (in German), vol. Band 1–2, Munich: Auflage.

- Rouvière, Jean-Marc (2006), Brèves méditations sur la Création du monde [Brief meditations on the creation of the World] (in French), Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Salibi, Kamal (1985), The Bible Came from Arabia, London: Jonathan Cape, ISBN 978-0-224-02830-1.

- Schmid, Konrad (2012), The Old Testament: A Literary History, Minneapolis: Fortress, ISBN 978-0-8006-9775-4.

- Silberman, Neil A; et al. (2003), The Bible Unearthed, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-0-684-86912-4 (hardback), ISBN 0-684-86913-6 (paperback).

- Sprinkle, Joseph ‘Joe’ M (2006), Biblical Law and Its Relevance: A Christian Understanding and Ethical Application for Today of the Mosaic Regulations, Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America, ISBN 978-0-7618-3371-0 (clothbound) and ISBN 0-7618-3372-2 (paperback).

External links[edit]

- Bible gateway. Full texts of the Old (and New) Testaments including the full Roman and Orthodox Catholic canons

- Early Jewish Writings, archived from the original on 2018-09-24, retrieved 2018-09-29 — Tanakh

- «Old Testament», Écritures, La feuille d’Olivier, archived from the original on 2010-12-07 Protestant Old Testament on a single page

- «Old Testament», Reading Room, Canada: Tyndale Seminary. Extensive online Old Testament resources (including commentaries)

- Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible), Yale University

- «Old Testament». Encyclopedia.com. The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.

- Bible, X10 host: Old Testament stories and commentary

- Tanakh ML (parallel Bible) – Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia and the King James Version

This article is about the Christian Bible. For the related Jewish text, see Hebrew Bible.

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites.[1] The second division of Christian Bibles is the New Testament, written in the Koine Greek language.

The Old Testament consists of many distinct books by various authors produced over a period of centuries.[2] Christians traditionally divide the Old Testament into four sections: the first five books or Pentateuch (corresponds to the Jewish Torah); the history books telling the history of the Israelites, from their conquest of Canaan to their defeat and exile in Babylon; the poetic and «Wisdom books» dealing, in various forms, with questions of good and evil in the world; and the books of the biblical prophets, warning of the consequences of turning away from God.

The books that compose the Old Testament canon and their order and names differ between various branches of Christianity. The canons of the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches comprise up to 49 books; the Catholic canon comprises 46 books; and the most common Protestant canon comprises 39 books.[3]

There are 39 books common to essentially all Christian canons. They correspond to the 24 books of the Tanakh, with some differences of order, and there are some differences in text. The additional number reflects the splitting of several texts (Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra–Nehemiah, and the Twelve Minor Prophets) into separate books in Christian Bibles. The books that are part of the Christian Old Testament but that are not part of the Hebrew canon are sometimes described as deuterocanonical. In general, Catholic and Orthodox churches include these books in the Old Testament. Most Protestant Bibles do not include the deuterocanonical books in their canon, but some versions of Anglican and Lutheran Bibles place such books in a separate section called apocrypha. These books are ultimately derived from the earlier Greek Septuagint collection of the Hebrew scriptures and are also Jewish in origin. Some are also contained in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Content[edit]

The Old Testament contains 39 (Protestant), 46 (Catholic), or more (Orthodox and other) books, divided, very broadly, into the Pentateuch (Torah), the historical books, the «wisdom» books and the prophets.[4]

The table below uses the spellings and names present in modern editions of the Christian Bible, such as the Catholic New American Bible Revised Edition and the Protestant Revised Standard Version and English Standard Version. The spelling and names in both the 1609–F10 Douay Old Testament (and in the 1582 Rheims New Testament) and the 1749 revision by Bishop Challoner (the edition currently in print used by many Catholics, and the source of traditional Catholic spellings in English) and in the Septuagint differ from those spellings and names used in modern editions which are derived from the Hebrew Masoretic text.[a]

For the Orthodox canon, Septuagint titles are provided in parentheses when these differ from those editions. For the Catholic canon, the Douaic titles are provided in parentheses when these differ from those editions. Likewise, the King James Version references some of these books by the traditional spelling when referring to them in the New Testament, such as «Esaias» (for Isaiah).

In the spirit of ecumenism more recent Catholic translations (e.g. the New American Bible, Jerusalem Bible, and ecumenical translations used by Catholics, such as the Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition) use the same «standardized» (King James Version) spellings and names as Protestant Bibles (e.g. 1 Chronicles as opposed to the Douaic 1 Paralipomenon, 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings instead of 1–4 Kings) in those books which are universally considered canonical, the protocanonicals.

The Talmud (the Jewish commentary on the scriptures) in Bava Batra 14b gives a different order for the books in Nevi’im and Ketuvim. This order is also cited in Mishneh Torah Hilchot Sefer Torah 7:15. The order of the books of the Torah is universal through all denominations of Judaism and Christianity.

The disputed books, included in most canons but not in others, are often called the Biblical apocrypha, a term that is sometimes used specifically to describe the books in the Catholic and Orthodox canons that are absent from the Jewish Masoretic Text and most modern Protestant Bibles. Catholics, following the Canon of Trent (1546), describe these books as deuterocanonical, while Greek Orthodox Christians, following the Synod of Jerusalem (1672), use the traditional name of anagignoskomena, meaning «that which is to be read.» They are present in a few historic Protestant versions; the German Luther Bible included such books, as did the English 1611 King James Version.[b]

Empty table cells indicate that a book is absent from that canon.

Pentateuch, corresponding to the Hebrew Torah

Historical books, most closely corresponding to the Hebrew Nevi’im (Prophets)

Wisdom books, most closely corresponding to the Hebrew Ketuvim (Writings)

Major Prophets

Twelve Minor Prophets

| Hebrew Bible(Tanakh)(24 books)[c] | ProtestantOld Testament(39 books) | CatholicOld Testament(46 books) | Eastern OrthodoxOld Testament(49 books) | Original language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Torah (Law) |

Pentateuch or the Five books of Moses |

|||

| Bereshit | Genesis | Genesis | Genesis | Hebrew |

| Shemot | Exodus | Exodus | Exodus | Hebrew |

| Vayikra | Leviticus | Leviticus | Leviticus | Hebrew |

| Bamidbar | Numbers | Numbers | Numbers | Hebrew |

| Devarim | Deuteronomy | Deuteronomy | Deuteronomy | Hebrew |

| Nevi’im (Prophets) |

Historical books |

|||

| Yehoshua | Joshua | Joshua (Josue) | Joshua (Iesous) | Hebrew |

| Shoftim | Judges | Judges | Judges | Hebrew |

| Rut (Ruth)[d] | Ruth | Ruth | Ruth | Hebrew |

| Shmuel | 1 Samuel | 1 Samuel (1 Kings)[e] | 1 Samuel (1 Kingdoms)[f] | Hebrew |

| 2 Samuel | 2 Samuel (2 Kings)[e] | 2 Samuel (2 Kingdoms)[f] | Hebrew | |

| Melakhim | 1 Kings | 1 Kings (3 Kings)[e] | 1 Kings (3 Kingdoms)[f] | Hebrew |

| 2 Kings | 2 Kings (4 Kings)[e] | 2 Kings (4 Kingdoms)[f] | Hebrew | |

| Divrei Hayamim (Chronicles)[d] | 1 Chronicles | 1 Chronicles (1 Paralipomenon) | 1 Chronicles (1 Paralipomenon) | Hebrew |

| 2 Chronicles | 2 Chronicles (2 Paralipomenon) | 2 Chronicles (2 Paralipomenon) | Hebrew | |

| 1 Esdras[g][h] | Greek | |||

| Ezra–Nehemiah[d] | Ezra | Ezra (1 Esdras) | Ezra (2 Esdras)[f][i][j] | Hebrew and Aramaic |

| Nehemiah | Nehemiah (2 Esdras) | Nehemiah (2 Esdras)[f][i] | Hebrew | |

| Tobit (Tobias) | Tobit[g] | Aramaic and Hebrew | ||

| Judith | Judith[g] | Hebrew | ||

| Ester (Esther)[d] | Esther | Esther[k] | Esther[k] | Hebrew |

| 1 Maccabees (1 Machabees)[l] | 1 Maccabees[g] | Hebrew and Greek[m] | ||

| 2 Maccabees (2 Machabees)[l] | 2 Maccabees[g] | Greek | ||

| 3 Maccabees[g] | Greek | |||

| 3 Esdras[g] | Greek | |||

| 4 Maccabees[n] | Greek | |||

| Ketuvim (Writings) | Wisdom books | |||

| Iyov (Job)[d] | Job | Job | Job | Hebrew |

| Tehillim (Psalms)[d] | Psalms | Psalms | Psalms[o] | Hebrew |

| Prayer of Manasseh[p] | Greek | |||

| Mishlei (Proverbs)[d] | Proverbs | Proverbs | Proverbs | Hebrew |

| Qohelet (Ecclesiastes)[d] | Ecclesiastes | Ecclesiastes | Ecclesiastes | Hebrew |

| Shir Hashirim (Song of Songs)[d] | Song of Solomon | Song of Songs (Canticle of Canticles) | Song of Songs (Aisma Aismaton) | Hebrew |

| Wisdom | Wisdom[g] | Greek | ||

| Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) | Sirach[g] | Hebrew | ||

| Nevi’im (Latter Prophets) | Major Prophets | |||

| Yeshayahu | Isaiah | Isaiah (Isaias) | Isaiah | Hebrew |

| Yirmeyahu | Jeremiah | Jeremiah (Jeremias) | Jeremiah | Hebrew |

| Eikhah (Lamentations)[d] | Lamentations | Lamentations | Lamentations | Hebrew |

| Baruch[q] | Baruch[q][g] | Hebrew[7] | ||

| Letter of Jeremiah[r][g] | Greek (majority view)[s] | |||

| Yekhezqel | Ezekiel | Ezekiel (Ezechiel) | Ezekiel | Hebrew |

| Daniyyel (Daniel)[d] | Daniel | Daniel[t] | Daniel[t] | Aramaic and Hebrew |

| Twelve Minor Prophets | ||||

| The TwelveorTrei Asar | Hosea | Hosea (Osee) | Hosea | Hebrew |

| Joel | Joel | Joel | Hebrew | |

| Amos | Amos | Amos | Hebrew | |

| Obadiah | Obadiah (Abdias) | Obadiah | Hebrew | |

| Jonah | Jonah (Jonas) | Jonah | Hebrew | |

| Micah | Micah (Michaeas) | Micah | Hebrew | |

| Nahum | Nahum | Nahum | Hebrew | |

| Habakkuk | Habakkuk (Habacuc) | Habakkuk | Hebrew | |

| Zephaniah | Zephaniah (Sophonias) | Zephaniah | Hebrew | |

| Haggai | Haggai (Aggaeus) | Haggai | Hebrew | |

| Zechariah | Zechariah (Zacharias) | Zechariah | Hebrew | |

| Malachi | Malachi (Malachias) | Malachi | Hebrew |

Several of the books in the Eastern Orthodox canon are also found in the appendix to the Latin Vulgate, formerly the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church.

|

Books in the Appendix to the Vulgate Bible |

|

| Name in Vulgate | Name in Eastern Orthodox use |

|---|---|

| 3 Esdras | 1 Esdras |

| 4 Esdras | 2 Esdras |

| Prayer of Manasseh | Prayer of Manasseh |

| Psalm of David when he slew Goliath (Psalm 151) | Psalm 151 |

Historicity[edit]

Early scholarship[edit]

Some of the stories of the Pentateuch may derive from older sources. American science writer Homer W. Smith points out similarities between the Genesis creation narrative and that of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, such as the inclusion of the creation of the first man (Adam/Enkidu) in the Garden of Eden, a tree of knowledge, a tree of life, and a deceptive serpent.[8] Scholars such as Andrew R. George point out the similarity of the Genesis flood narrative and the Gilgamesh flood myth.[9][u] Similarities between the origin story of Moses and that of Sargon of Akkad were noted by psychoanalyst Otto Rank in 1909[13] and popularized by 20th century writers, such as H. G. Wells and Joseph Campbell.[14][15] Jacob Bronowski writes that, «the Bible is … part folklore and part record. History is … written by the victors, and the Israelis, when they burst through [Jericho (c. 1400 BC)], became the carriers of history.»[16]

Recent scholarship[edit]

In 2007, a scholar of Judaism Lester L. Grabbe explained that earlier biblical scholars such as Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918) could be described as ‘maximalist’, accepting biblical text unless it has been disproven. Continuing in this tradition, both «the ‘substantial historicity’ of the patriarchs» and «the unified conquest of the land» were widely accepted in the United States until about the 1970s. Contrarily, Grabbe says that those in his field now «are all minimalists – at least, when it comes to the patriarchal period and the settlement. … [V]ery few are willing to operate [as maximalists].»[17]

Composition[edit]

The first five books—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, book of Numbers and Deuteronomy—reached their present form in the Persian period (538–332 BC), and their authors were the elite of exilic returnees who controlled the Temple at that time.[18] The books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings follow, forming a history of Israel from the Conquest of Canaan to the Siege of Jerusalem c. 587 BC. There is a broad consensus among scholars that these originated as a single work (the so-called «Deuteronomistic History») during the Babylonian exile of the 6th century BC.[19]

The two Books of Chronicles cover much the same material as the Pentateuch and Deuteronomistic history and probably date from the 4th century BC.[20] Chronicles, and Ezra–Nehemiah, was probably finished during the 3rd century BC.[21] Catholic and Orthodox Old Testaments contain two (Catholic Old Testament) to four (Orthodox) Books of Maccabees, written in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC.

These history books make up around half the total content of the Old Testament. Of the remainder, the books of the various prophets—Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the twelve «minor prophets»—were written between the 8th and 6th centuries BC, with the exceptions of Jonah and Daniel, which were written much later.[22] The «wisdom» books—Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Psalms, Song of Solomon—have various dates: Proverbs possibly was completed by the Hellenistic time (332–198 BC), though containing much older material as well; Job completed by the 6th century BC; Ecclesiastes by the 3rd century BC.[23]

Themes[edit]

Throughout the Old Testament, God is consistently depicted as the one who created the world. Although the God of the Old Testament is not consistently presented as the only God who exists, he is always depicted as the only God whom Israel is to worship, or the one «true God», that only Yahweh (or YHWH) is Almighty.[24]

The Old Testament stresses the special relationship between God and his chosen people, Israel, but includes instructions for proselytes as well. This relationship is expressed in the biblical covenant (contract)[25][26][27][28][29][30] between the two, received by Moses. The law codes in books such as Exodus and especially Deuteronomy are the terms of the contract: Israel swears faithfulness to God, and God swears to be Israel’s special protector and supporter.[24] However, The Jewish Study Bible denies that the word covenant (brit in Hebrew) means «contract»; in the ancient Near East, a covenant would have been sworn before the gods, who would be its enforcers. As God is part of the agreement, and not merely witnessing it, The Jewish Study Bible instead interprets the term to refer to a pledge.[31]

Further themes in the Old Testament include salvation, redemption, divine judgment, obedience and disobedience, faith and faithfulness, among others. Throughout there is a strong emphasis on ethics and ritual purity, both of which God demands, although some of the prophets and wisdom writers seem to question this, arguing that God demands social justice above purity, and perhaps does not even care about purity at all. The Old Testament’s moral code enjoins fairness, intervention on behalf of the vulnerable, and the duty of those in power to administer justice righteously. It forbids murder, bribery and corruption, deceitful trading, and many sexual misdemeanours. All morality is traced back to God, who is the source of all goodness.[32]

The problem of evil plays a large part in the Old Testament. The problem the Old Testament authors faced was that a good God must have had just reason for bringing disaster (meaning notably, but not only, the Babylonian exile) upon his people. The theme is played out, with many variations, in books as different as the histories of Kings and Chronicles, the prophets like Ezekiel and Jeremiah, and in the wisdom books like Job and Ecclesiastes.[32]

Formation[edit]

The interrelationship between various significant ancient manuscripts of the Old Testament, according to the Encyclopaedia Biblica (1903). Some manuscripts are identified by their siglum. LXX here denotes the original Septuagint.

The process by which scriptures became canons and Bibles was a long one, and its complexities account for the many different Old Testaments which exist today. Timothy H. Lim, a professor of Hebrew Bible and Second Temple Judaism at the University of Edinburgh, identifies the Old Testament as «a collection of authoritative texts of apparently divine origin that went through a human process of writing and editing.»[2] He states that it is not a magical book, nor was it literally written by God and passed to mankind. By about the 5th century BC, Jews saw the five books of the Torah (the Old Testament Pentateuch) as having authoritative status; by the 2nd century BC, the Prophets had a similar status, although without quite the same level of respect as the Torah; beyond that, the Jewish scriptures were fluid, with different groups seeing authority in different books.[33]

Greek[edit]

Hebrew texts began to be translated into Greek in Alexandria in about 280 and continued until about 130 BC.[34] These early Greek translations – supposedly commissioned by Ptolemy Philadelphus – were called the Septuagint (Latin for ‘Seventy’) from the supposed number of translators involved (hence its abbreviation «LXX»). This Septuagint remains the basis of the Old Testament in the Eastern Orthodox Church.[35]

It varies in many places from the Masoretic Text and includes numerous books no longer considered canonical in some traditions: 1 and 2 Esdras, Judith, Tobit, 3 and 4 Maccabees, the Book of Wisdom, Sirach, and Baruch.[36] Early modern biblical criticism typically explained these variations as intentional or ignorant corruptions by the Alexandrian scholars, but most recent scholarship holds it is simply based on early source texts differing from those later used by the Masoretes in their work.

The Septuagint was originally used by Hellenized Jews whose knowledge of Greek was better than Hebrew. However, the texts came to be used predominantly by gentile converts to Christianity and by the early Church as its scripture, Greek being the lingua franca of the early Church. The three most acclaimed early interpreters were Aquila of Sinope, Symmachus the Ebionite, and Theodotion; in his Hexapla, Origen placed his edition of the Hebrew text beside its transcription in Greek letters and four parallel translations: Aquila’s, Symmachus’s, the Septuagint’s, and Theodotion’s. The so-called «fifth» and «sixth editions» were two other Greek translations supposedly miraculously discovered by students outside the towns of Jericho and Nicopolis: these were added to Origen’s Octapla.[37]

In 331, Constantine I commissioned Eusebius to deliver fifty Bibles for the Church of Constantinople. Athanasius[38] recorded Alexandrian scribes around 340 preparing Bibles for Constans. Little else is known, though there is plenty of speculation. For example, it is speculated that this may have provided motivation for canon lists and that Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus are examples of these Bibles. Together with the Peshitta and Codex Alexandrinus, these are the earliest extant Christian Bibles.[39] There is no evidence among the canons of the First Council of Nicaea of any determination on the canon. However, Jerome (347–420), in his Prologue to Judith, claims that the Book of Judith was «found by the Nicene Council to have been counted among the number of the Sacred Scriptures».[40]

Latin[edit]

In Western Christianity or Christianity in the Western half of the Roman Empire, Latin had displaced Greek as the common language of the early Christians, and in 382 AD Pope Damasus I commissioned Jerome, the leading scholar of the day, to produce an updated Latin Bible to replace the Vetus Latina, which was a Latin translation of the Septuagint. Jerome’s work, called the Vulgate, was a direct translation from Hebrew, since he argued for the superiority of the Hebrew texts in correcting the Septuagint on both philological and theological grounds.[41] His Vulgate Old Testament became the standard Bible used in the Western Church, specifically as the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate, while the Churches in the East continued, and continue, to use the Septuagint.[42]

Jerome, however, in the Vulgate’s prologues describes some portions of books in the Septuagint not found in the Hebrew Bible as being non-canonical (he called them apocrypha);[43] for Baruch, he mentions by name in his Prologue to Jeremiah and notes that it is neither read nor held among the Hebrews, but does not explicitly call it apocryphal or «not in the canon».[44] The Synod of Hippo (in 393), followed by the Council of Carthage (397) and the Council of Carthage (419), may be the first council that explicitly accepted the first canon which includes the books that did not appear in the Hebrew Bible;[45] the councils were under significant influence of Augustine of Hippo, who regarded the canon as already closed.[46]

Protestant canon[edit]

In the 16th century, the Protestant reformers sided with Jerome; yet although most Protestant Bibles now have only those books that appear in the Hebrew Bible, the order is that of the Greek Bible.[47]

Rome then officially adopted a canon, the Canon of Trent, which is seen as following Augustine’s Carthaginian Councils[48] or the Council of Rome,[49][50] and includes most, but not all, of the Septuagint (3 Ezra and 3 and 4 Maccabees are excluded);[51] the Anglicans after the English Civil War adopted a compromise position, restoring the 39 Articles and keeping the extra books that were excluded by the Westminster Confession of Faith, both for private study and for reading in churches but not for establishing any doctrine, while Lutherans kept them for private study, gathered in an appendix as biblical apocrypha.[47]

Other versions[edit]

While the Hebrew, Greek and Latin versions of the Hebrew Bible are the best known Old Testaments, there were others. At much the same time as the Septuagint was being produced, translations were being made into Aramaic, the language of Jews living in Palestine and the Near East and likely the language of Jesus: these are called the Aramaic Targums, from a word meaning «translation», and were used to help Jewish congregations understand their scriptures.[52]

For Aramaic Christians there was a Syriac translation of the Hebrew Bible called the Peshitta, as well as versions in Coptic (the everyday language of Egypt in the first Christian centuries, descended from ancient Egyptian), Ethiopic (for use in the Ethiopian church, one of the oldest Christian churches), Armenian (Armenia was the first to adopt Christianity as its official religion), and Arabic.[52]

Christian theology[edit]

Christianity is based on the belief that the historical Jesus is also the Christ, as in the Confession of Peter. This belief is in turn based on Jewish understandings of the meaning of the Hebrew term Messiah, which, like the Greek «Christ», means «anointed». In the Hebrew Scriptures, it describes a king anointed with oil on his accession to the throne: he becomes «The LORD‘s anointed» or Yahweh’s Anointed.

By the time of Jesus, some Jews expected that a flesh and blood descendant of David (the «Son of David») would come to establish a real Jewish kingdom in Jerusalem, instead of the Roman province of Judaea.[53] Others stressed the Son of Man, a distinctly other-worldly figure who would appear as a judge at the end of time. Some expounded a synthesised view of both positions, where a messianic kingdom of this world would last for a set period and be followed by the other-worldly age or World to Come.

Some[who?] thought the Messiah was already present, but unrecognised due to Israel’s sins; some[who?] thought that the Messiah would be announced by a forerunner, probably Elijah (as promised by the prophet Malachi, whose book now ends the Old Testament and precedes Mark’s account of John the Baptist). However, no view of the Messiah as based on the Old Testament predicted a Messiah who would suffer and die for the sins of all people.[53] The story of Jesus’ death, therefore, involved a profound shift in meaning from the Old Testament tradition.[54]

The name «Old Testament» reflects Christianity’s understanding of itself as the fulfilment of Jeremiah’s prophecy of a New Covenant (which is similar to «testament» and often conflated) to replace the existing covenant between God and Israel (Jeremiah 31:31)[55].[1] The emphasis, however, has shifted from Judaism’s understanding of the covenant as a racially- or tribally-based pledge between God and the Jewish people, to one between God and any person of faith who is «in Christ».[56]

See also[edit]

- Abrogation of Old Covenant laws

- Biblical and Quranic narratives

- Book of Job in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

- Criticism of the Bible

- Expounding of the Law

- Law and Gospel

- List of ancient legal codes

- List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts

- Marcion of Sinope

- Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible

- Quotations from the Hebrew Bible in the New Testament

- Timeline of Genesis patriarchs

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Generally due to derivation from transliterations of names used in the Latin Vulgate in the case of Catholicism, and from transliterations of the Greek Septuagint in the case of the Orthodox (as opposed to the derivation of translations, instead of transliterations, of Hebrew titles) such Ecclesiasticus (DRC) instead of Sirach (LXX) or Ben Sira (Hebrew), Paralipomenon (Greek, meaning «things omitted») instead of Chronicles, Sophonias instead of Zephaniah, Noe instead of Noah, Henoch instead of Enoch, Messias instead of Messiah, Sion instead of Zion, etc.

- ^ The foundational Thirty-Nine Articles of Anglicanism, in Article VI, asserts these disputed books are not used «to establish any doctrine», but «read for example of life.» Although the Biblical Apocrypha are still used in Anglican Liturgy,[5] the modern trend is to not even print the Old Testament Apocrypha in editions of Anglican-used Bibles

- ^ The 24 books of the Hebrew Bible are the same as the 39 books of the Protestant Old Testament, only divided and ordered differently: the books of the Minor Prophets are in Christian Bibles twelve different books, and in Hebrew Bibles, one book called «The Twelve». Likewise, Christian Bibles divide the Books of Kingdoms into four books, either 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings or 1–4 Kings: Jewish Bibles divide these into two books. The Jews likewise keep 1–2 Chronicles/Paralipomenon as one book. Ezra and Nehemiah are likewise combined in the Jewish Bible, as they are in many Orthodox Bibles, instead of divided into two books, as per the Catholic and Protestant tradition.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k This book is part of the Ketuvim, the third section of the Jewish canon. There is a different order in Jewish canon than in Christian canon.

- ^ a b c d The books of Samuel and Kings are often called First through Fourth Kings in the Catholic tradition, much like the Orthodox.

- ^ a b c d e f Names in parentheses are the Septuagint names and are often used by the Orthodox Christians.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k One of 11 deuterocanonical books in the Russian Synodal Bible.

- ^ 2 Esdras in the Russian Synodal Bible.

- ^ a b Some Eastern Orthodox churches follow the Septuagint and Hebrew Bibles by considering the books of Ezra and Nehemiah as one book.

- ^ 1 Esdras in the Russian Synodal Bible.

- ^ a b The Catholic and Orthodox Book of Esther includes 103 verses not in the Protestant Book of Esther.

- ^ a b The Latin Vulgate, Douay–Rheims, and Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition place First and Second Maccabees after Malachi; other Catholic translations place them after Esther.

- ^ 1 Maccabees is hypothesized by most scholars to have been originally written in Hebrew; however, if it was, the original Hebrew has been lost. The surviving Septuagint version is in Greek.[6]

- ^ In Greek Bibles, 4 Maccabees is found in the appendix.

- ^ Eastern Orthodox churches include Psalm 151 and the Prayer of Manasseh, not present in all canons.

- ^ Part of 2 Paralipomenon in the Russian Synodal Bible.

- ^ a b In Catholic Bibles, Baruch includes a sixth chapter called the Letter of Jeremiah. Baruch is not in the Protestant Bible or the Tanakh.

- ^ Eastern Orthodox Bibles have the books of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah separate.

- ^ Hebrew (minority view); see Letter of Jeremiah for details.

- ^ a b In Catholic and Orthodox Bibles, Daniel includes three sections not included in Protestant Bibles. The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children are included between Daniel 3:23–24. Susanna is included as Daniel 13. Bel and the Dragon is included as Daniel 14. These are not in the Protestant Old Testament.

- ^ The latter flood myth appears in a Babylonian copy dating to 700 BC,[10] though many scholars believe that this was probably copied from the Akkadian Atra-Hasis, which dates to the 18th century BC.[11] George points out that the modern version of the Epic of Gilgamesh was compiled by Sîn-lēqi-unninni, who lived sometime between 1300 and 1000 BC.[12]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Jones 2000, p. 215.

- ^ a b Lim, Timothy H. (2005). The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 41.

- ^ Barton 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Boadt 1984, pp. 11, 15–16.

- ^ The Apocrypha, Bridge of the Testaments (PDF), Orthodox Anglican, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-05,

Two of the hymns used in the American Prayer Book office of Morning Prayer, the Benedictus es and Benedicite, are taken from the Apocrypha. One of the offertory sentences in Holy Communion comes from an apocryphal book (Tob. 4: 8–9). Lessons from the Apocrypha are regularly appointed to be reason Sunday, Sunday, and the special services of Morning and Evening Prayer. There are altogether 111 such lessons in the latest revised American Prayer Book Lectionary [Books used are: II Esdras, Tobit, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, Three Holy Children, and I Maccabees.]

- ^ Goldstein, Jonathan A. (1976). I Maccabees. The Anchor Bible Series. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. p. 14. ISBN 0-385-08533-8.

- ^ Driver, Samuel Rolles (1911). «Bible» . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 849–894, see page 853, third para.

Jeremiah…..were first written down in 604 B.C. by his friend and amanuensis Baruch, and the roll thus formed must have formed the nucleus of the present book. Some of the reports of Jeremiah’s prophecies, and especially the biographical narratives, also probably have Baruch for their author. But the chronological disorder of the book, and other indications, show that Baruch could not have been the compiler of the book

- ^ Smith, Homer W. (1952). Man and His Gods. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. p. 117.

- ^ George, A. R. (2003). The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-927841-1.

- ^ Cline, Eric H. (2007). From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. National Geographic. pp. 20–27. ISBN 978-1-4262-0084-7.

- ^ Tigay, Jeffrey H. (2002) [1982]. The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. pp. 23, 218, 224, 238. ISBN 9780865165465.

- ^ The Epic of Gilgamesh. Translated by Andrew R. George (reprinted ed.). London: Penguin Books. 2003 [1999]. pp. ii, xxiv–v. ISBN 0-14-044919-1.

- ^ Otto Rank (1914). The myth of the birth of the hero: a psychological interpretation of mythology. English translation by Drs. F. Robbins and Smith Ely Jelliffe. New York: The Journal of nervous and mental disease publishing company.

- ^ Wells, H. G. (1961) [1937]. The Outline of History: Volume 1. Doubleday. pp. 206, 208, 210, 212.

- ^ Campbell, Joseph (1964). The Masks of God, Vol. 3: Occidental Mythology. p. 127.

- ^ Bronowski, Jacob (1990) [1973]. The Ascent of Man. London: BBC Books. pp. 72–73, 77. ISBN 978-0-563-20900-3.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (2007-10-25). «Some Recent Issues in the Study of the History of Israel». Understanding the History of Ancient Israel. British Academy. pp. 57–58. doi:10.5871/bacad/9780197264010.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-726401-0.

- ^ Blenkinsopp 1998, p. 184.

- ^ Rogerson 2003, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Coggins 2003, p. 282.

- ^ Grabbe 2003, pp. 213–14.

- ^ Miller 1987, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Crenshaw 2010, p. 5.

- ^ a b Barton 2001, p. 9: «4. Covenant and Redemption. It is a central point in many OT texts that the creator God YHWH is also in some sense Israel’s special god, who at some point in history entered into a relationship with his people that had something of the nature of a contract. Classically this contract or covenant was entered into at Sinai, and Moses was its mediator.»

- ^ Coogan 2008, p. 106.

- ^ Ferguson 1996, p. 2.

- ^ Ska 2009, p. 213.

- ^ Berman 2006, p. unpaginated: «At this juncture, however, God is entering into a «treaty» with the Israelites, and hence the formal need within the written contract for the grace of the sovereign to be documented.30 30. Mendenhall and Herion, «Covenant,» p. 1183.»

- ^ Levine 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Hayes 2006.

- ^ Berlin & Brettler 2014, p. PT194: 6.17-22: Further introduction and a pledge. 18: This v. records the first mention of the covenant («brit») in the Tanakh. In the ancient Near East, a covenant was an agreement that the parties swore before the gods, and expected the gods to enforce. In this case, God is Himself a party to the covenant, which is more like a pledge than an agreement or contract (this was sometimes the case in the ancient Near East as well). The covenant with Noah will receive longer treatment in 9.1-17.

- ^ a b Barton 2001, p. 10.

- ^ Brettler 2005, p. 274.

- ^ Gentry 2008, p. 302.

- ^ Würthwein 1995.

- ^ Jones 2000, p. 216.

- ^ Cave, William. A complete history of the lives, acts, and martyrdoms of the holy apostles, and the two evangelists, St. Mark and Luke, Vol. II. Wiatt (Philadelphia), 1810. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- ^ Apol. Const. 4

- ^ The Canon Debate, pp. 414–15, for the entire paragraph

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). «Book of Judith» . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Canonicity: «…» the Synod of Nicaea is said to have accounted it as Sacred Scripture» (Praef. in Lib.). No such declaration indeed is to be found in the Canons of Nicaea, and it is uncertain whether St. Jerome is referring to the use made of the book in the discussions of the council, or whether he was misled by some spurious canons attributed to that council».

- ^ Rebenich, S., Jerome (Routledge, 2013), p. 58. ISBN 9781134638444

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 91–99.

- ^ «The Bible». www.thelatinlibrary.com.

- ^ Kevin P. Edgecomb, Jerome’s Prologue to Jeremiah, archived from the original on 2013-12-31, retrieved 2015-11-30

- ^ McDonald & Sanders, editors of The Canon Debate, 2002, chapter 5: The Septuagint: The Bible of Hellenistic Judaism by Albert C. Sundberg Jr., page 72, Appendix D-2, note 19.

- ^ Everett Ferguson, «Factors leading to the Selection and Closure of the New Testament Canon», in The Canon Debate. eds. L. M. McDonald & J. A. Sanders (Hendrickson, 2002) p. 320; F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Intervarsity Press, 1988) p. 230; cf. Augustine, De Civitate Dei 22.8

- ^ a b Barton 1997, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Philip Schaff, «Chapter IX. Theological Controversies, and Development of the Ecumenical Orthodoxy», History of the Christian Church, CCEL

- ^ Lindberg (2006). A Brief History of Christianity. Blackwell Publishing. p. 15.

- ^ F.L. Cross, E.A. Livingstone, ed. (1983), The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 232