4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 3738.

Обновлено 30 Марта, 2021

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 3738.

Обновлено 30 Марта, 2021

В начале XIX века во Франции к власти пришел Наполеон, который решил завоевать весь мир. Ему удалось покорить многие страны, но без сломленной России он не мог чувствовать себя полноправным мировым хозяином. Он был уверен, что очень быстро завоюет северное государство, но именно здесь познал поражение. Давайте поговорим кратко о войне 1812 года.

Опыт работы преподавателем — более 48 лет.

Кто такой Наполеон

В 1799 году Францию возглавил генерал Наполеон Бонапарт – человек невероятно амбициозный, трудолюбивый и решительный. В течение десяти лет, что он управлял страной, Франция находилась в череде бесконечных войн. В результате Наполеону удалось покорить всю Европу, но ему этого было мало.

Наполеон – это уникальная личность, человек необычной судьбы. Будучи сыном бедного дворянина, он смог в кратчайшие сроки взобраться на самую верхушку армейской иерархии и в 24 года стать генералом. В возрасте 35 лет этот «выскочка» был провозглашен императором Франции.

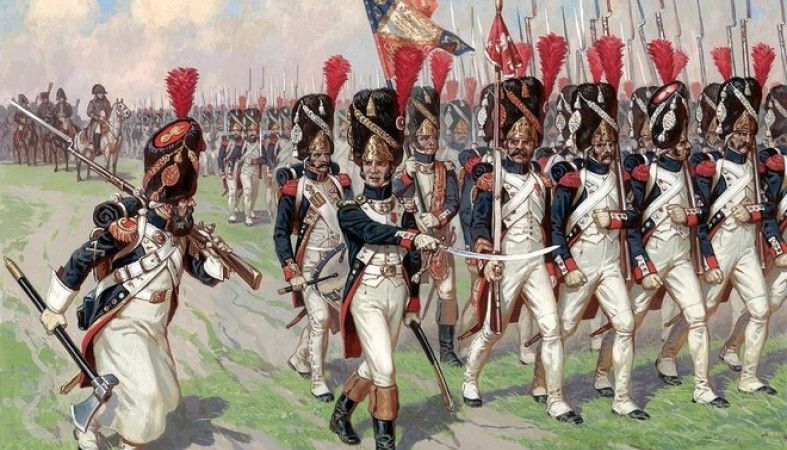

Чтобы покорить себе весь мир, Бонапарту требовалось лишь завоевать Россию. К предстоящей войне он очень серьезно подготовился, собрав прекрасно вооруженное и обученное войско, состоящее из 600 тысяч опытных солдат и толковых военачальников.

На стороне французской армии был численный перевес и опыт в боях, и Бонапарт не сомневался, что ему удастся в короткие сроки поставить на колени российскую империю.

Вторжение в Россию

В июне 1812 года войска Наполеона пересекли границы России и двинулись по направлению к Москве. Общая численность русской армии составляла 590 тыс. человек, однако на момент вторжения французских войск она была рассредоточена в трех разных местах. Бонапарт планировал быстро разгромить русских, пока те были порознь и не успели соединить свои военные части.

ТОП-4 статьи

которые читают вместе с этой

Первый удар на себя приняла небольшая часть русских войск, состоящая из 240 тыс. солдат. Стратегия Бонапарта заключалась в высоком темпе наступления, однако этому помешали:

- огромные расстояния;

- очень плохие дороги;

- прикрытое сопротивление простого люда.

В августе командующим русской армии был назначен опытнейший полководец Михаил Илларионович Кутузов. В одном из сражений он лишился глаза, и с тех пор на его лице всегда была темная повязка. Солдаты очень любили своего командующего, на него возлагала большие надежды вся Россия.

До того, как вступить в Москву, наполеоновской армии пришлось принять участие в девяти крупных сражениях. Потери были велики с обеих сторон, Бонапарт стремился как можно быстрее дать основное, самое важное сражение.

Битва при Бородино

Главная битва русской и французской армий состоялась неподалеку от села Бородино в августе 1812 года. Это сражение, длившееся целый день, оказалось самым кровопролитным за всю историю того времени. Страшные потери несли обе стороны: десятками, сотнями гибли солдаты на поле брани.

Чтобы сохранить хотя бы часть армии, Кутузов был вынужден принять нелегкое решение – оставить Москву противнику. Вместе с русскими войсками столицу покинули и местные жители.

Наполеон въехал со своей армией в пустой город и дал разрешение своим воинам грабить завоеванный город. Отважные солдаты быстро превратились в мародеров – грабителей. В городе начались пожары, которые поглотили древние и очень ценные предметы русской культуры: картины, книги, храмы, дворцы.

Однако ликование французской армии длилось недолго. С приходом суровой зимы закончились все съестные припасы, и среди солдат начался голод. Ситуацию осложняло и активное партизанское движение, состоящее из простых жителей.

Спасаясь от мести партизан, голода и страшного холода, французы бросали награбленное добро и сдавались в плен. В декабре 1812 года, понимая всю бессмысленность пребывания в России, Бонапарт бросил свои войска и бежал на родину.

Так опытный и дальновидный Кутузов выиграл битву у великого французского императора, который до этого не знал ни единого поражения. Но заслуга в долгожданной победе была не только Кутузова, а всего русского народа, сплотившегося на защиту своей Отчизны. Именно поэтому эта война в историю вошла как Отечественная.

Что мы узнали?

При изучении темы «Отечественная война 1812 года» по программе окружающего мира 4 класса мы узнали, кто и почему решил покорить себе Россию. Мы выяснили, как шло продвижение вражеских войск, где произошло важнейшее сражение и чем оно закончилось.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Светлана Горбань

9/10

-

Оксана Батяева

10/10

-

Ольга Прошина

7/10

-

Регина Кичигина

10/10

-

Любовь Кудрина

9/10

-

Заур Гамзаев

10/10

-

Алина Назарова

7/10

-

Алиса Хрустова

8/10

-

Артемий Андреев

10/10

-

Адим Яфаров

8/10

Оценка доклада

4.7

Средняя оценка: 4.7

Всего получено оценок: 3739.

А какая ваша оценка?

Отечественная война 1812 года – это война между Французской и Российской империями, которая проходила на территории России. Несмотря на превосходство французской армии, под руководством Наполеона Бонапарта, русским войскам удалось показать невероятную доблесть и смекалку.

Более того, русским удалось выйти победителями в этом тяжелом противостоянии. До сих пор победа над французами считается одной из самых знаковых в истории России.

Предлагаем вашему вниманию краткую историю Отечественной войны 1812 года. Если вы хотите краткую выжимку об этом периоде нашей истории, рекомендуем к прочтению 17 интересных фактов о войне 1812 года.

Причины и характер войны

Отечественная война 1812 года произошла вследствие стремления Наполеона к мировому господству. До этого ему удавалось с успехом одерживать победу над многими противниками.

Главным и единственным его врагом на территории Европы оставалась Великобритания. Французский император хотел уничтожить Британию посредством континентальной блокады.

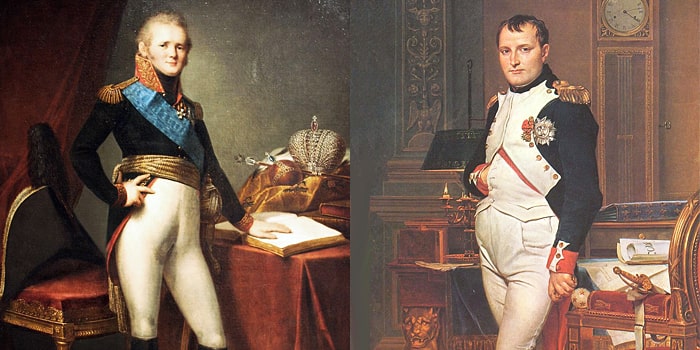

Стоит заметить, что за 5 лет до начала Отечественной войны 1812 года между Францией и Россией был подписан Тильзитский мирный договор. Однако главный пункт этого договора не был тогда опубликован. Согласно ему, Александр 1 обязывался поддерживать Наполеона в блокаде, направленной против Великобритании.

Тем не менее, как французы, так и русские прекрасно понимали, что рано или поздно между ними также начнется война, так как Наполеон Бонапарт не собирался останавливаться на подчинении одной Европы.

Именно поэтому страны начали активно готовиться к будущей войне, наращивая военный потенциал и увеличивая численность своих армий.

Отечественная война 1812 года кратко

В 1812 году Наполеон Бонапарт вторгся на территорию Российской империи. Таким образом, для русского народа эта война стала Отечественной, поскольку в ней принимала участие не только армия, но и большинство простых граждан.

Соотношение сил

Перед началом Отечественной войны 1812 года Наполеону удалось собрать огромную армию, в которой было около 675 тысяч воинов.

Все они были хорошо вооружены и, что самое главное, имели большой боевой опыт, ведь к тому времени Франция подчинила себе почти всю Европу.

Русская армия почти не уступала французам в численности войск, которых насчитывалось порядка 600 тысяч. К тому же в войне участвовало еще около 400 тысяч русских ополченцев.

К тому же, в отличие от французов, преимущество русских было в том, что они были патриотически настроены и сражались за освобождение своей земли, благодаря чему поднимался национальный дух.

В армии же Наполеона с патриотизмом дела обстояли ровным счетом наоборот, ведь там присутствовало немало наемных солдат, которым было все равно за что или против чего воевать.

Более того, Александр 1 (см. интересные факты об Александре 1) сумел неплохо вооружить свое войско и серьезно усилить артиллерию, которая, как выяснится вскоре, превзошла французскую.

Кроме этого русскими войсками командовали такие опытные военачальники, как Багратион, Раевский, Милорадович и знаменитый Кутузов.

Также следует понимать, что по численности людей и продовольственному запасу Россия, находящаяся на своей земле, превосходила Францию.

Планы сторон

В самом начале Отечественной войны 1812 года, Наполеон планировал совершить на Россию молниеносную атаку, захватив значительную ее территорию.

После этого он намерен был заключить с Александром 1 новый договор, согласно которому Российская империя должна была подчиниться Франции.

Имея большой опыт в сражениях, Бонапарт зорко следил за тем, чтобы разделенные русские войска не соединились вместе. Он считал, что ему будет значительно проще победить противника, когда он будет разделен на части.

Еще до начала войны Александр 1 публично заявил о том, что ни он, ни его армия не должны идти на какие-либо компромиссы с французами. Более того, он планировал воевать с армией Бонапарта не на своей территории, а за ее пределами, где-нибудь в западной части Европы.

В случае неудачи русский император готов был отступить на север, и уже оттуда продолжать сражаться с Наполеоном. Интересен факт, что на тот момент у России не было ни одного четко продуманного плана ведения войны.

Этапы войны

Отечественная война 1812 года проходила в 2 этапа. На первом этапе русские планировали намерено отступать назад, чтобы заманить французов в ловушку, а также сорвать тактический план Наполеона.

Следующим шагом должно было быть контрнаступление, которое позволило бы вытеснить противника за пределы Российской империи.

История Отечественной войны 1812 года

12 июня 1812 года наполеоновская армия перешла через Неман, после чего вошла в Россию. Навстречу им вышли 1-я и 2-я русские армии, сознательно не вступавшее в открытый бой с врагом.

Они вели арьергардные сражения, целью которых было изматывание противника с нанесением ему значительных потерь.

Александр 1 отдал приказ, чтобы его войска избегали разобщенности и не давали врагу разбить себя на отдельные части. В конечном счете, благодаря хорошо спланированной тактике, им удалось этого добиться. Таким образом первый план Наполеона остался нереализованным.

8 августа Главнокомандующим русской армией был назначен Михаил Кутузов. Он также продолжил тактику общего отступления.

И хотя русские отходили назад целенаправленно, они, как и весь народ, ждали главной битвы, которая рано или поздно все равно должна была состояться.

В скором времени это сражение произойдет вблизи села Бородино, расположенного неподалеку от Москвы.

Сражения Отечественной войны 1812 года

В разгар Отечественной войны 1812 года Кутузов избрал оборонительную тактику. На левом фланге войсками командовал Багратион, в центре располагалась артиллерия Раевского, а на правом фланге находилась армия Барклая де Толли.

Наполеон же предпочитал больше атаковать, чем защищаться, поскольку эта тактика неоднократно помогала ему выходить победителем из военных кампаний.

Он понимал, что рано или поздно русские прекратят отступление и им придется принять сражение. На тот момент времени французский император был уверен в своей победе и, надо сказать, на то были веские причины.

До 1812 года он уже успел показать всему миру мощь французской армии, которая смогла завоевать не одну европейскую страну. Талант же самого Наполеона, как выдающегося полководца, был признан всеми.

Бородинская битва

Бородинская битва (см. интересные факты о Бородинской битве), которую воспел Михаил Лермонтов в поэме «Бородино», состоялось 26 августа (7 сентября) 1812 года у деревни Бородино, в 125 км к западу от Москвы.

Наполеон зашел слева и провел несколько атак на противника, вступив в открытое сражение с русской армией. В тот момент обе стороны начали активно применять артиллерию, неся серьезные потери.

В конечном счете, русские организованно отступили назад, однако это ничего не дало Наполеону.

Затем французы начали атаковать центр русских войск. В связи с этим Кутузов (см. интересные факты из жизни Кутузова) приказал казакам обойти противника с тыла и нанести по нему удар.

Несмотря на то, что план не принес никакой пользы русским, он вынудил Наполеона на несколько часов остановить атаку. Благодаря этому Кутузов успел подтянуть к центру дополнительные силы.

В конечном счете, Наполеону все-таки удалось взять русские укрепления, однако, как и раньше, это не принесло ему никакой существенной выгоды. Из-за постоянных атак он терял много солдат, поэтому скоро бои начали затихать.

Обе стороны потеряли большое количество людей и орудий. Однако битва при Бородино подняла моральный дух русских, которые поняли, что могут весьма успешно сражаться с великой армией Наполеона. Французы же наоборот были деморализованы, удручены неудачей и находились в полной растерянности.

Подробнее о Бородинском сражении читайте здесь.

От Москвы до Малоярославца

Отечественная война 1812 года продолжалась. После Бородинской битвы армия Александра 1 продолжила отступление, все ближе и ближе подходя к Москве.

Французы шли следом, однако уже не стремились вступать в открытый бой. 1 сентября на военном совете русских генералов Михаил Кутузов принял сенсационное решение, с которым многие были не согласны.

Он настоял на том, чтобы Москва была оставлена, а все имущество в ней – уничтожено. В результате все так и произошло.

14 сентября Наполеон без боя занял Москву.

Французская армия, измотанная физически и морально, нуждалась в пополнении запасов продовольствия и отдыхе. Однако их ждало горькое разочарование.

Оказавшись в Москве, Наполеон не увидел ни одного жителя или даже животного. Оставляя Москву, русские подожгли все постройки, чтобы враг не смог ничем воспользоваться. Это был небывалый в истории случай.

Когда французы осознали всю плачевность своего глупого положения, они были окончательно деморализованы и разбиты. Многие солдаты перестали подчиняться командирам и превратились в шайки грабителей, бегавших по окрестностям города.

Русские войска напротив, смогли оторваться от Наполеона и зайти в Калужскую и Тульскую губернии. Там у них были спрятаны продовольственные запасы и боеприпасы. Кроме этого солдаты могли отдохнуть от тяжелого похода и пополнить ряды армии.

Лучшим разрешением этой нелепой для Наполеона ситуации было заключение с Россией мира, однако все его предложения о перемирии были отвергнуты Александром 1 и Кутузовым.

Через месяц французы с позором начали покидать Москву. Бонапарт был в ярости от такого исхода событий и делал все возможное, чтобы вступить с русскими в сражение.

Дойдя до Калуги 12 октября, у города Малоярославец, произошло крупное сражение, в котором обе стороны потеряли множество людей и военной техники. Однако окончательная победа не досталась никому.

Победа в Отечественной войне 1812 года

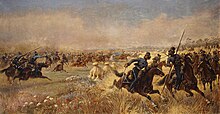

Дальнейшее отступление Наполеоновской армии скорее напоминало хаотичное бегство, чем организованный выход из России. После того, как французы начали мародерствовать, местные жители стали объединяться в партизанские отряды и вступать в сражения с врагом.

В это время Кутузов осторожно преследовал армию Бонапарта, избегая с ней открытых столкновений. Он мудро берег своих воинов, прекрасно осознавая, что силы противника тают на глазах.

Французы понесли серьезные потери в битве под городом Красный. В этом сражении погибли десятки тысяч захватчиков. Отечественная война 1812 года подходила к своему завершению.

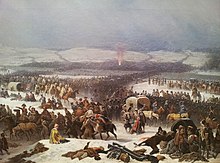

Когда Наполеон пытался спасти остатки армии и переправить их через реку Березину, он в очередной раз понес тяжелое поражение от русских. При этом следует понимать, что французы не были готовы к необычайно сильным морозам, которые ударили в самом начале зимы.

Очевидно, что перед нападением на Россию Наполеон не планировал задерживаться в ней так долго, вследствие чего не позаботился о теплом обмундировании для своего войска.

В результате бесславного отступления, Наполеон бросил солдат на произвол судьбы и тайно сбежал во Францию.

25 декабря 1812 года Александр 1 издал манифест, в котором говорилось о завершении Отечественной войны.

Причины поражения Наполеона

Среди причин поражения Наполеона в его русском походе наиболее часто называют:

- всенародное участие в войне и массовый героизм русских солдат и офицеров;

- протяжённость территории России и суровые климатические условия;

- полководческое дарование главнокомандующего русской армией Кутузова и других генералов.

Главной причиной поражения Наполеона стал общенациональный подъём русских на защиту Отечества. В единении русской армии с народом надо искать источник её мощи в 1812 году.

Итоги Отечественной войны 1812 года

Отечественная война 1812 года является одним из знаковых событий в истории России. Русским войскам удалось остановить непобедимую армию Наполеона Бонапарта и проявить невиданный героизм.

Война нанесла серьезный ущерб экономике Российской империи, который оценивался в сотни миллионов рублей. На полях битвы полегло более 200 тысяч человек.

Немало населенных пунктов были полностью или частично уничтожены, а на их восстановление требовались не только большие суммы, но и человеческие ресурсы.

Однако несмотря на это победа в Отечественной войне 1812 года, укрепила моральный дух всего русского народа. После нее, многие европейские страны начали с уважением относиться к армии Российской империи.

Главным итогом Отечественной войны 1812 года стало практически полное уничтожение Великой Армии Наполеона.

Если вам понравилась краткая история Отечественной войны 1812 года, – поделитесь ею в социальных сетях и подпишитесь на сайт InteresnyeFakty.org. С нами всегда интересно!

Понравился пост? Нажми любую кнопку:

«Second Polish War» redirects here. For the 1794 uprising, see Kościuszko Uprising.

| French invasion of Russia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars | ||||||

Clockwise from top left:

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||

|

Supported by: |

|||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||

|

|

|||||

| Strength | ||||||

|

450,000[2] – 685,000[3] total:

|

508,000 – 723,000 total:[2]

|

|||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||

|

400,000–484,000

|

410,000

|

|||||

|

Total military and civilian deaths: c. 1,000,000[17] |

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign, the Second Polish War, the Army of Twenty nations, and the Patriotic War of 1812 was launched by Napoleon Bonaparte to force the Russian Empire back into the continental blockade of the United Kingdom. Napoleon’s invasion of Russia is one of the best studied military campaigns in history and is listed among the most lethal military operations in world history.[18] It is characterized by the massive toll on human life: in less than six months nearly a million soldiers and civilians died.[19][17]

On 24 June 1812 and the following days, the first wave of the multinational Grande Armée crossed the Niemen into Russia. Through a series of long forced marches, Napoleon pushed his army of almost half a million people rapidly through Western Russia, now Belarus, in an attempt to destroy the separated Russian armies of Barclay de Tolly and Pyotr Bagration who amounted to around 180,000–220,000 at this time.[20][21] Within six weeks, Napoleon lost half of the men because of the extreme weather conditions, disease and hunger, winning just the Battle of Smolensk. The Russian Army continued to retreat, under its new Commander in Chief Mikhail Kutuzov, employing attrition warfare against Napoleon forcing the invaders to rely on a supply system that was incapable of feeding their large army in the field.

The fierce Battle of Borodino, seventy miles (110 km) west of Moscow, was a narrow French victory that resulted in a Council at Fili. There Kutuzov decided not to defend the city but to a general withdrawal to save the Russian army.[22] (At the time, Moscow was a very important city, but not the capital of Russia; from 1732 to 1918, Saint Petersburg served as a capital). On 14 September, Napoleon and his army of about 100,000 men occupied Moscow, only to find it abandoned, and the city was soon ablaze, instigated by its military governor. Napoleon stayed in Moscow for five weeks, waiting for a peace offer that never came.[23] Because of the nice weather he left late, hoping to reach the magazines in Smolensk by a detour. Losing the Battle of Maloyaroslavets he was forced to take the same route as he came. In early November it began to snow, which complicated the retreat. Lack of food and winter clothes for the men and fodder for the horses, and guerilla warfare from Russian peasants and Cossacks led to greater losses. Again more than half of the men died on the roadside of exhaustion, typhus and the harsh continental climate. The Grande Armée had deteriorated into a disorganized mob, and the Russians could not conclude otherwise.

In the Battle of Krasnoi Napoleon was able to avoid a complete defeat. Meanwhile, he was almost without cavalry and artillery, and deployed the Old Guard for the first time.[24] Although several retreating French corps united with the main army, when the Berezina was reached, Napoleon had only about 49,000 troops and 40,000 stragglers of little military value. On 5 December, Napoleon left the army at Smorgonie in a sledge and returned to Paris. Within a few days, 20,000 more perished from the bitter cold and louse-borne diseases.[25] Murat and Ney, the new commanders, continued, leaving more than 20,000 men behind in the hospitals of Vilnius. What was left of the main armies crossed the frozen Niemen and the Bug disillusioned.

Although estimates vary because precise records were not kept,[26] numbers were exaggerated and auxiliary troops were not always counted, Napoleon’s army entered Russia with more than 450,000 men,[27] more than 150,000 horses,[28] around 25,000 wagons and almost 1,400 pieces of artillery. Only 120,000 men survived (excluding early deserters);[a] as many as 380,000 died in the campaign.[30] Perhaps most importantly, Napoleon’s reputation of invincibility was shattered.[31]

Background[edit]

French invasion of Russia

Prussian corps

Napoleon

Austrian corps

The French Empire in 1812

From 1792 and onwards, France had been at a near constant state of war with the major European powers, a consequence of the French Revolution. Napoleon, who seized power in 1799 and ruled France as an autocrat, conducted several military campaigns which resulted in the creation of the first French empire. Starting in 1803, the Napoleonic Wars had proven Napoleon’s abilities.[32] He emerged victorious in the War of the Third Coalition (1803–1806, which dissolved the thousand-year-old Holy Roman Empire), the War of the Fourth Coalition (1806–1807), and the War of the Fifth Coalition (1809).

In 1807, Napoleon and Alexander I of Russia had signed the Treaty of Tilsit on the Neman River after a French victory at Friedland. The treaties had gradually strengthened Russia’s alliance with France and made Napoleon dominate all their neighbors. The agreement made Russia a French ally and they adopted the Continental System, which was a blockade on the United Kingdom.[33] But the treaty was economically hard on Russia, and Tsar Alexander left the Continental blockade on 31 December 1810. Napoleon was now deprived of his chief foreign policy tool against the United Kingdom.[34]

The Treaty of Schönbrunn, which ended the 1809 war between Austria and France had a clause removing Western Galicia from Austria and annexing it to the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. Russia viewed this as against its interests as they considered the territory to be a potential launching point for a French invasion.[35]

Napoleon had tried to get better Russian cooperation through an alliance by seeking to marry Anna Pavlovna, the youngest sister of Alexander. But finally, he married Marie Louise, the daughter of the Austrian emperor instead. France and Austria signed an alliance treaty on 14 March 1812.

Napoleon himself was not in the same physical and mental state as in years past. He had become overweight and increasingly prone to various maladies.[36]

Declaration of war[edit]

Committed to the expansion policy of Catherine the Great, Alexander I had issued an ultimatum demanding that France evacuate its troops from Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw in April 1812. Napoleon chose war over retreat.

Officially Napoleon announced the following proclamation:

Soldiers, the second Polish war is begun. The first terminated at Friedland, and at Tilsit, Russia vowed an eternal alliance with France, and war with the English. She now breaks her vows and refuses to give any explanation of her strange conduct until the French eagles have repassed the Rhine, and left our allies at her mercy. Russia is hurried away by a fatality: her destinies will be fulfilled. Does she think us degenerated? Are we no more the soldiers who fought at Austerlitz? She places us between dishonour and war—our choice cannot be difficult. Let us then march forward; let us cross the Niemen and carry the war into her country. This second Polish war will be as glorious for the French arms as the first has been, but the peace we shall conclude shall carry with it its own guarantee, and will terminate the fatal influence which Russia for fifty years past has exercised in Europe.[37]

Between the 8th and the 20th of June, the troops had been in perpetual motion and daily had to undertake the most arduous marches in the most abominable heat.[38] Napoleon’s objective was to rout the Imperial Russian army and force Czar Alexander I to return to the Continental System.[39]

Logistics[edit]

French attack by infantry

The invasion of Russia clearly and dramatically demonstrates the importance of logistics in military planning, especially when the land will not provide for the number of troops deployed in an area of operations far exceeding the experience of the invading army.[40] Napoleon made extensive preparations for provisioning his army.[41] The French supply effort was far greater than in any of the previous campaigns.[42] Twenty train battalions, comprising 7,848 vehicles, were to provide a 40-day supply for the Grande Armée and its operations, and a large system of magazines were established in towns and cities in Poland and East Prussia.[43] The Vistula river valley was built up in 1811–1812 as a supply base.[41] Intendant General Guillaume-Mathieu Dumas established five lines of supply from the Rhine to the Vistula.[42] French-controlled Germany and Poland were organized into three arrondissements with their own administrative headquarters.[42] The logistical buildup that followed was a critical test of Napoleon’s administrative and logistical skill, who devoted his efforts during the first half of 1812 largely to the provisioning of his invasion army.[41] Napoleon studied Russian geography and the history of Charles XII’s invasion of 1708–1709 and understood the need to bring forward as many supplies as possible.[41] The French Army already had previous experience of operating in the lightly populated and underdeveloped conditions of Poland and East Prussia during the War of the Fourth Coalition in 1806–1807.[41]

However, nothing was to go as planned, because Napoleon had failed to take into account conditions that were totally different from what he had known so far.[44]

Napoleon and the Grande Armée were used to living off the land, which had worked well in the densely populated and agriculturally rich central Europe with its dense network of roads.[45] Rapid forced marches had dazed and confused old-order Austrian and Prussian armies and much use had been made of foraging.[45] Forced marches in Russia often made troops do without supplies as the supply wagons struggled to keep up;[45] furthermore, horse-drawn wagons and artillery were stalled by lack of roads which often turned to mud due to rainstorms.[46] Lack of food and water in thinly populated, much less agriculturally dense regions led to the death of troops and their mounts by exposing them to waterborne diseases from drinking from mud puddles and eating rotten food and forage. The front of the army received whatever could be provided while the formations behind starved.[47]

The most advanced magazine in the operations area during the attack phase was Vilna, beyond that point, the army was on its own.[44]

Ammunition[edit]

A massive arsenal was established in Warsaw.[41] Artillery was concentrated at Magdeburg, Danzig, Stettin, Küstrin and Glogau.[48] Magdeburg contained a siege artillery train with 100 heavy guns and stored 462 cannons, two million paper cartridges and 300,000 pounds/135 tonnes of gunpowder; Danzig had a siege train with 130 heavy guns and 300,000 pounds of gunpowder; Stettin contained 263 guns, a million cartridges and 200,000 pounds/90 tonnes of gunpowder; Küstrin contained 108 guns and a million cartridges; Glogau contained 108 guns, a million cartridges and 100,000 pounds/45 tonnes of gunpowder.[48] Warsaw, Danzig, Modlin, Thorn and Marienburg became ammunition and supply depots as well.[41] Polish legions, including Lithuanians formed the largest foreign contingent.

Provisions and transportation[edit]

Danzig contained enough provisions to feed 400,000 men for 50 days.[48] Breslau, Plock and Wyszogród were turned into grain depots, milling vast quantities of flour for delivery to Thorn, where 60,000 biscuits were produced every day.[48] A large bakery was established at Villenberg (Braniewo County).[42] 50,000 cattle were collected to follow the army.[42] After the invasion began, large magazines were constructed at Kovno (Kaunas), Vilna (Vilnius), and Minsk, with the Vilna base having enough rations to feed 100,000 men for 40 days.[42] It also contained 27,000 muskets, 30,000 pairs of shoes along with brandy and wine.[42] Medium-sized depots were established at Vitebsk, Orsha, and Smolensk, and several small ones throughout the Russian interior.[42] The French also captured numerous intact Russian supply dumps, which the Russians had failed to destroy or empty, and Moscow itself was filled with food.[42] Twenty train battalions provided most of the transportation, with a combined load of 8,390 tons.[48] Twelve of these battalions had a total of 3,024 heavy wagons drawn by four horses each, four had 2,424 one-horse light wagons and four had 2,400 wagons drawn by oxen.[48] Auxiliary supply convoys were formed on Napoleon’s orders in early June 1812, using vehicles requisitioned in East Prussia.[49] Marshal Nicolas Oudinot’s IV Corps alone took 600 carts formed into six companies.[50] The wagon trains were supposed to carry enough bread, flour and medical supplies for 300,000 men for two months.[50]

The standard heavy wagons, well-suited for the dense and partially paved road networks of Germany and France, proved too cumbersome for the sparse and primitive Russian dirt tracks.[51] The supply route from Smolensk to Moscow was therefore entirely dependent on light wagons with small loads.[50] Central to the problem were the expanding distances to supply magazines and the fact that no supply wagon could keep up with a forced marched infantry column.[46] The weather itself became an issue, where, according to historian Richard K. Riehn:

The thunderstorms of the 29th [of June] turned into other downpours, turning the tracks—some diarists claim there were no roads in Lithuania—into bottomless mires. Wagons sank up to their hubs; horses dropped from exhaustion; men lost their boots. Stalled wagons became obstacles that forced men around them and stopped supply wagons and artillery columns. Then came the sun which would bake the deep ruts into canyons of concrete, where horses would break their legs and wagons their wheels.[46]

The heavy losses to disease, hunger and desertion in the early months of the campaign were in large part due to the inability to transport provisions quickly enough to the troops.[51] The Intendance administration failed to distribute with sufficient rigor the supplies that were built up or captured.[42] By that, despite all these preparations, the Grande Armée was not self-sufficient logistically and still depended on foraging to a significant extent.[49]

Inadequate supplies played a key role in the losses suffered by the army as well. Davidov and other Russian campaign participants record wholesale surrenders of starving members of the Grande Armée even before the onset of the frosts.[52] Caulaincourt describes men swarming over and cutting up horses that slipped and fell, even before the horse had been killed.[53] The French simply were unable to feed their army. Starvation led to a general loss of cohesion.[54] Constant harassment of the French Army by Cossacks added to the losses during the retreat.[52]

Though starvation caused horrendous casualties in Napoleon’s army, losses arose from other sources as well. The main body of Napoleon’s Grande Armée diminished by a third in just the first eight weeks of the campaign, before the major battle was fought. This loss in strength was in part due to diseases such as diphtheria, dysentery and typhus and the need for garrison supply centres.[52][55] There are eyewitness reports of cannibalism in November 1812.[56]

Combat service and support and medicine[edit]

Nine pontoon companies, three pontoon trains with 100 pontoons each, two companies of marines, nine sapper companies, six miner companies and an engineer park were deployed for the invasion force.[48] Large-scale military hospitals were created at Warsaw, Thorn, Breslau, Marienburg, Elbing and Danzig,[48] while hospitals in East Prussia had beds for 28,000.[42]

Invasion[edit]

Crossing the Russian border[edit]

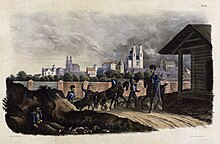

Anonymous, «Grande Armée» crossing the river

Italian corps of Eugene de Beauharnais crossing the Niemen on 30 June 1812. Oil and gouache on paper by Albrecht Adam who travelled with IV Corps. In: Hermitage Museum

After a whole day of preparation, the invasion commenced on Wednesday, 24 June [O.S. 12 June] 1812 with Napoleon’s army crossing the border.[b] The army was split up into five columns:

1. The left wing under Macdonald with the X corps of 30,000 men (half of them Prussians) crossed the Niemen at Tilsit on the 24th.[59] He moved north in Courland but did not succeed in occupying Riga. Early August he occupied Dunaburg; early September he returned to Riga with his entire force.[60] On 18 December, a few days after the French left the Russian Empire, he drew back to Königsberg, followed by Peter Wittgenstein. On 25 December one of his generals Yorck von Wartenburg found himself isolated because the Russian army blocked the road. After five days he was urged by his officers (and in the presence of Carl von Clausewitz), at least to neutralization of his troops and an armistice. Yorck’s resolution had enormous consequences.[61]

2. In the evening of 23 June Morand accompanied by sappers occupied the other side of the Niemen. The next morning Napoleon followed by the Imperial Guard (47,000) crossed the river on one of the three pontoon bridges nearby Napoleon’s Hill. Afterwards, Murat’s cavalry and three corps crossed the river destined for Vilnius. Then they followed Barclay de Toll’s First Army of the West to Drissa and Polotsk.[62]

- Cavalry corps of Murat (32,000) advanced to Vilnius and Polotsk in the vanguard.

- I corps of Davout (72,000), the strongest corps, left Vilnius on 1 July and occupied Minsk a week later. His goal was to cut off Bagration from Barclay de Tolly. He already had lost a third of his men but beat Bagration at Mogilev and then went to Smolensk, where he joined the main army.

- II corps of Oudinot (37,000) crossed the Niemen and the Viliya to combat Peter Wittgenstein, who protected the road to St Petersburg. Oudinot didn’t succeed in joining up with Macdonald and joined the VIth corps. For two months these corps kept Wittgenstein at a distance until the Second Battle of Polotsk.

- III corps of Ney (39,000) defended downstream the 4th pontoon bridge at Aleksotas which could be used to escape; he then went to Polotsk.

Second Central force crossed at Pilona 20 km upstream.

- IV corps of Beauharnais (45,000 Italians) crossed the Niemen near Pilona.[63][64][65] Napoleon’s stepson had orders to avoid Vilnius on his way to Vitebsk.

- VI corps of St. Cyr (25,000 Bavarians) crossed at Pilona.[66] He was to throw himself between the two Russian armies and cut off all communication between them.[67] He followed the II corps to Polotsk, forming the northern flank.[68] Both corps never saw Moscow.

With French forces moving through different routes in the direction of Polotsk and Vitebsk, the first major engagement took place on 25 July at the Battle of Ostrowno.

3. Right flank force under Napoleon’s brother Jérôme Bonaparte, King of Westphalia (62,000). He crossed the Niemen near Grodno on 1 July,[65] and moved towards Bagration’s (second western) army. It seems he was advancing slowly so the stragglers could catch up. On the order of Napoleon Davout secretly took over the command on 6 July.[69] The Battle of Mir was a tactical victory for the Russians; Jerome let Platov escape by deploying too few of Poniatowki’s troops.[70] Jérôme left the army after being criticised by Davout.[71] He went home at the end of July,[72] taking a small battalion of guards with him.[73]

- IV Cavalry corps of Latour Maubourg (8,000) joined Davout.

- V corps (36,000 (Polish) soldiers) under Poniatowski joined Davout and went to Mogilev and Smolensk.

- VIII Corps (17,000 Westphalians) under Vandamme who was sent home in early July. Jérôme Bonaparte took over but resigned on 15 July when he found out Davout had been secretly given the command.[73][74] Early August the command was given to Junot.[75] In the Battle of Smolensk (1812) Junot was sent to bypass the left flank of the Russian army, but he got lost and was unable to carry out this operation.[76] Junot, a heavy drinker, was blamed for allowing the Russian army to retreat arriving too late at the Battle of Valutino.[77] After the Battle of Borodino he had only 2,000 men left.[78] Junot committed suicide in 1813?

4. The right or southern wing under Schwarzenberg (34,000) crossed the Western Bug on a pontoon bridge at Drohiczyn on 2 July. Tormasow’s third army prevented him from joining up with Davout. When Tormassov occupied Brest (Belarus) at the end of July, Schwarzenberg and Reynier were cut off from supplies.[79] On 18 September the Austrians withdrew when Pavel Chichagov arrived from the south and seized Minsk on 18 November.[80] On 14 December 1812 Schwarzenberg crossed the border.[81]

- VII corps of Reynier (17,000 Saxons) stayed in the Grodno region and cooperated with Schwarzenberg to protect the Duchy of Warsaw against Tormassov.

5. During the campaign reinforcements of 80,000 and the baggage trains with 30,000 men were sent on different dates. In November, the division of Durutte assisted Reynier. In December Loison was sent to help extricate the remnants of the Grand Army in its retreat.[82] Within a few days many of Loison’s unexperienced soldiers died of the extreme cold.

[83] Napoleon arrested him for not marching with his division to the front.

- IX corps of Victor (33,000). The majority was sent to Smolensk in early September;[78] he took over the command from St. Cyr. At the end of October, he retreated, losing significant supplies in Vitebsk to Wittgenstein. Victor and H.W. Daendels were ordered to cover the retreat to the Berezina.

- XI corps of Augerau was part of the reserve. It was created later in the late summer.[84] It contained an entire division of reformed deserters.[85] This corps, based in Poland did not participate in military operations in Russia until November/December. Augereau never left Berlin; his younger brother general Jean-Pierre and his troops were compelled to surrender to the partisans Aleksandr Figner and Denis Davydov on 9 November.[86]

March on Vilna[edit]

Eugene’s tent in Rykantai on 3 July 1812 when he received orders to avoid the Vilnius by Albrecht Adam.

Halšany by Albrecht Adam, on 11 July 1812

Napoleon initially met little resistance and moved quickly into the enemy’s territory in spite of the transport of more than 1,100 cannons, being opposed by the Russian armies with more than 900 cannons. But the roads in this area of Lithuania were actually small dirt tracks through areas of birched woodland and marshes. At the beginning of the war supply lines already simply could not keep up with the forced marches of the corps and rear formations always suffered the worst privations.[87]

On the 25th of June Murat’s reserve cavalry provided the vanguard with Napoleon, the Imperial guard and Davout’s 1st corps following behind. Napoleon spent the night and the next day in Kaunas, allowing only his guards, not even the generals to enter the city.[58] The next day he rushed towards the capital Vilna, pushing the infantry forward in columns that suffered from stifling heat, heavy rain and more heat.[88] The central group marched 70 miles (110 km) in two days.[89] Ney’s III Corps marched down the road to Sudervė, with Oudinot marching on the other side of the Viliya river.

Since the end of April, the Russian headquarters was centred in Vilna but on June 24 couriers rushed news about the crossing of the Niemen to Barclay de Tolley. Before the night had passed, orders were sent out to Bagration and Platov, who commanded the Cossacks, to take the offensive. Alexander left Vilna on June 26 and Barclay assumed overall command.

Napoleon reached Vilna on 28 June with only light skirmishing but leaving more than 5,000 dead horses in his wake. These horses were vital to bringing up further supplies to an army in desperate need; he was forced to leave up to 100 guns and up to 500 artillery wagons. Napoleon had supposed that Alexander would sue for peace at this point and was to be disappointed; it would not be his last disappointment.[90] Balashov demanded that the French returned across the Niemen before negotiations.[91] Barclay continued to retreat to Drissa, deciding that the concentration of the 1st and 2nd armies was his first priority.[92]

Several days after crossing the Niemen, a number of soldiers began to develop high fevers and a red rash on their bodies. Typhus had made its appearance. On 29/30 June, a violent thunderstorm struck Lithuania during the night and continued for several hours or a day.[93][94]

The results were most disastrous to the French forces. The movement of troops was impeded or absolutely checked and the vast troop and supply trains on the Vilnius-Kaunas Road became disorganized. The existing roads became little better than quagmires causing the horses to break down under the additional strain. The delay and frequent loss of these supply trains caused both troops and horses to suffer. Napoleon’s forces traditionally were well supplied by his transportation corps, but they proved inadequate during the invasion.

[95][96]

The foraging in Lithuania proved hard as the land was mostly barren and forested. The supplies of forage were less than that of Poland, and two days of forced marching made a bad supply situation worse.[97] Some 50,000 stragglers and deserters became a lawless mob warring with the local peasantry in all-out guerrilla war, which further hindered supplies reaching the Grande Armée. Central to the problem were the expanding distances to supply magazines and the fact that no supply wagon could keep up with a forced marched infantry column.[46] The weather itself became an issue.

A Lieutenant Mertens—a Württemberger serving with Ney’s III corps—reported in his diary that oppressive heat followed by cold nights and rain left them with dead horses and camping in swamp-like conditions with dysentery and fever raging through the ranks with hundreds in a field hospital that had to be set up for the purpose. He reported the times, dates and places of events, reporting new thunderstorms on 6 July and men dying of sunstroke a few days later.[46] Rapid forced marches quickly caused desertion, suicide and starvation, and exposed the troops to filthy water and disease, while the logistics trains lost horses by the thousands, further exacerbating the problems.

March on Vitebsk and Minsk[edit]

Mid July; the IV corps struggling with fatigue and heat by Albrecht Adam

Although Barclay wanted to give battle, he assessed it as a hopeless situation and ordered Vilna’s magazines burned and its bridge dismantled. Wittgenstein moved his command to Klaipeda, passing beyond Macdonald and Oudinot’s operations with Wittgenstein’s rear guard clashing with Oudinout’s forward elements.[98] Barclay continued his retreat and, with the exception of the occasional rearguard clash, remained unhindered in his movements ever further east.[99]

The operation intended to split Bagration’s forces from Barclay’s forces by driving to Vilna had cost the French forces 25,000 losses from all causes in a few days.[100] Strong probing operations were advanced from Vilna towards Nemenčinė,[101] Molėtai in the north and Ashmyany in the east, the location of Bagration on his way to Minsk. Bagration ordered Platov and Dokhturov to distract the enemy.

Murat advanced to Nemenčinė on July 1, running into elements of Dmitry Dokhturov’s III Russian Cavalry Corps. Napoleon assumed this was Bagration’s 2nd Army and rushed out, before being told it was not. Napoleon then attempted to use Davout, Jerome, and Eugene out on his right in a hammer and anvil to catch Bagration and to destroy the 2nd Army in an operation before reaching Minsk. This operation had failed to produce results on his left.

Conflicting orders and lack of information had almost placed Bagration in a bind marching into Davout; however, Jerome could not arrive in time over the same mud tracks, supply problems, and weather, that had so badly affected the rest of the Grande Armée. Command disputes between Jerome, General Vandamme and Davout would not help the situation.[102]

In the first two weeks of July, the Grande Armée lost 100,000 men due to sickness and desertion.[103] On 8 July Dirk van Hogendorp was appointed as Governor of Lithuania organizing hospitals for the wounded in Vilnius and supplies for the army; Louis Henri Loison was appointed in Königsberg.[104] The main problem was forage from East Prussia. For three weeks, the Dutch soldiers had hardly seen bread and only eaten soup.[105] Desertion was high among Spanish and Portuguese formations. The deserters proceeded to terrorize the population, looting whatever lay to hand. The areas in which the Grande Armée passed were devastated and depopulated.

Davout had lost 10,000 men marching to Minsk, which he reached on the 8th and would not attack Bagration without Jerome joining him. He ordered Polish cavalry to search for the thousands of looting soldiers who stayed behind. Davout left the city after four days where a Polish governor was appointed; Joseph Barbanègre had to organize the logistics. Davout crossed the Berezina and ran into the Battle of Mogilev with Bagration; he went to Orsha, and crossed the Dniepr on his way to Smolensk. Davout thought Bagration had some 60,000 men and Bagration thought Davout had 70,000. Bagration was getting orders from both Alexander’s staff and Barclay (which Barclay didn’t know) and left Bagration without a clear picture of what was expected of him and the general situation. This stream of confused orders to Bagration had him upset with Barclay, which would have repercussions later.[106]

After five weeks, the loss of troops from disease and desertion had reduced Napoleon’s effective fighting strength to about half.[107] Ney and his corps were given ten days to recover and search for food.

[108]

March on Smolensk[edit]

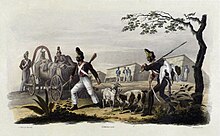

French troops leaving Polotsk (Faber du Faur, 25.07.1812)

Liozna: French soldiers between Vitebsk and Smolensk organizing something to eat. (Faber du Faur, 4.08.1812)

Napoleon and Poniatowski with the burning city of Smolensk

The total length of the city wall around the Smolensk Kremlin was 6.5 kilometres, with a height of up to 19 metres and a width of up to 5.2 metres, and a total of 38 watchtowers. The Kremlin lost nine towers because of the bombardment and fire.

Exactly at midnight, on July 16, Napoleon left Vilnius. On 19 July the Tsar left the army in Polotsk and headed for Moscow, taking the discredited Von Phull with him.[109][c] Barclay, the Russian commander-in-chief, refused to fight despite Bagration’s urgings. Several times he attempted to establish a strong defensive position, but each time the French advance was too quick for him to finish preparations and he was forced to retreat once more. When the French Army progressed further (under conditions of extreme heat and drought, rivers and wells filled with carrion) it encountered serious problems in foraging, aggravated by the scorched earth tactics of the Russian forces.[110][111] After the battle of Vitebsk Napoleon discovered that the Russians were able to slip away during the night. The city, at the intersection of important trade routes, and the palace of Alexander of Württemberg would be his base for the next two weeks. His army needed to recover and rest, but Napoleon asked himself what to do next.

According to Antoine-Henri Jomini, the governor of Vilnius, Napoleon planned not to go further than Smolensk and make Vilnius his headquarter for the winter. However, he could not go back at the end of July. His position was unfavourable according to Adam Zamoyski. There was the heat — also at night — and the lack of supplies. He had lost a third of his army due to sickness and straggling.[112] The Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812) had come to an end as Kutuzov signed the Treaty of Bucharest and the Russian general Pavel Chichagov headed north-west. His former ally Bernadotte broke off relations with France and entered into an alliance with Russia (Treaty of Örebro). Mid-July Napoleon’s brother Jérome resigned and decided to go home. (For Napoleon he lost the opportunity to destroy the Russian armies separately.)

On 4 August the corps of Barclay and Bagration finally succeeded to unite in Smolensk.[113][114] On 5 August they held a council of war. Under pressure, Barclay de Tolly decided to launch an offensive. A Russian force was sent west. Napoleon hoped that the Russian advance would lead to the long-desired battle and the unification of the Russian armies forced Napoleon to change his plans. On 15 August, Napoleon celebrated his 43rd birthday with a review of the army. In the late afternoon, Murat’s cavalry and Ney’s infantry closed up to the western side of Smolensk. The main body of the army did not come up until late the next day.[115]

The Battle of Smolensk (1812) on August 16–18 became the first real confrontation. Napoleon surrounded the southern bank of the Dniepr, while the northern bank was guarded by Barclay’s army. When Bagration moved further east, to prevent the French from crossing the river and attacking the Russians from behind, Napoleon began the attack on the Smolensk Kremlin in the evening. In the middle of the night Barclay de Tolly withdrew his troops from the burning city to avoid a big battle with no chance of victory. When the French army moved in the Russians left on the east side. Ney, Junot and Oudinot tried to halt their army. The Battle of Valutino could have been decisive but the Russians succeeded to escape via a diversion on the road to Moscow. The French discussed their options or prepare for a new attack after winter. Napoleon pressed his army on after the Russians.[116] Murat implored him to stop, but Napoleon could see nothing but Moscow.[76] On 24 August, the Grande Armée marched out of Smolensk; Eugene on the left, Poniatowski on the right and Murat in the centre, with the Emperor, the Guard, I Corps and III Corps in the second line. Joseph Barbanègre was appointed commander of the devastated city and had to organise new supplies.

- Kutuzov in command

Meanwhile, Wittgenstein was forced to retreat to the north after the First Battle of Polotsk. Bagration asked Aleksey Arakcheyev to organize the militia, as Barclay had led the French right into the capital.[115] Political pressure on Barclay to give battle and the general’s continuing reluctance to do so led to his removal after the defeat. On 20 August he was replaced in his position as commander-in-chief by the popular veteran Mikhail Kutuzov. The former head of the St. Petersburg militia and a member of the State Council arrived on the 29th at Tsaryovo-Zaymishche, a border village.[117] [d] The weather was still unbearably hot and Kutuzov went on with Barclay’s successful strategy, using attrition warfare instead of risking the army in an open battle. Napoleon’s superiority in numbers was almost eliminated. The Russian Army fell back ever deeper into Russia’s interior as he continued to move east. Unable because of political pressure to give up Moscow without a fight, Kutuzov took up a defensive position some 75 miles (121 km) before Moscow at Borodino.

The Battle of Borodino[edit]

Napoleon and his staff at Borodino by Vasily Vereshchagin

The Battle of Borodino, fought on 7 September 1812, was the largest battle of the French invasion of Russia, involving more than 250,000 troops and resulting in at least 70,000 casualties.[118] The French Grande Armée under Emperor Napoleon I attacked the Imperial Russian Army of General Mikhail Kutuzov near the village of Borodino, west of the town of Mozhaysk, and eventually captured the main positions on the battlefield but failed to destroy the Russian army. About a third of Napoleon’s soldiers were killed or wounded; Russian losses, while heavier, could be replaced due to Russia’s large population, since Napoleon’s campaign took place on Russian soil.

The battle ended with the Russian Army, while out of position, still offering resistance.[119] The state of exhaustion of the French forces and the lack of recognition of the state of the Russian Army led Napoleon to remain on the battlefield with his army, instead of engaging in the forced pursuit that had marked other campaigns that he had conducted.[120] The entirety of the Guard was still available to Napoleon, and in refusing to use it he lost this singular chance to destroy the Russian Army.[121] The battle at Borodino was a pivotal point in the campaign, as it was the last offensive action fought by Napoleon in Russia. By withdrawing, the Russian Army preserved its combat strength, eventually allowing it to force Napoleon out of the country.

The Battle of Borodino on September 7 was the bloodiest day of battle in the Napoleonic Wars. The Russian Army could only muster half of its strength on September 8. Kutuzov chose to act in accordance with his scorched earth tactics and retreat, leaving the road to Moscow open. Kutuzov also ordered the evacuation of the city.

By this point the Russians had managed to draft large numbers of reinforcements (volunteers) into the army, bringing total Russian land forces to their peak strength in 1812 of 904,000, with perhaps 100,000 in the vicinity of Moscow—the remnants of Kutuzov’s army from Borodino partially reinforced.

Both armies began to move and rebuild. The Russian retreat was significant for two reasons: firstly, the move was to the south and not the east; secondly, the Russians immediately began operations that would continue to deplete the French forces. Platov, commanding the rear guard on September 8, offered such strong resistance that Napoleon remained on the Borodino field.[119] On the following day, Miloradovich assumed command of the rear guard, adding his forces to the formation.

On 8 September the Russian army began retreating east from Borodino.[119] They camped outside Mozhaysk.[122][123] When the village of Mozhaysk was captured by the French on the 9th, the Grande Armée rested for two days to recover.[124] Napoleon asked Berthier to send reinforcements from Smolensk to Moscow and from Minsk to Smolensk. The French Army began to move out on September 10 with the still ill Napoleon not leaving until the 12th. Some 18,000 men were ordered in from Smolensk, and Marshal Victor’s corps supplied another 25,000.[125]

Capture of Moscow[edit]

Kutuzov on the far left, with his generals at the talks deciding to surrender Moscow to the French

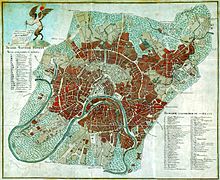

Areas of Moscow destroyed by the fire in red

Moscow 1812 (Faber du Faur)

Russian prisoners of war in 1812. (Faber du Faur)

On 10 September the main quarter of the Russian army was situated at Bolshiye Vyazyomy.[126] Kutuzov settled in a Vyazyomy Manor on the high road to Moscow. The owner was Dmitry Golitsyn, who entered military service again. The next day Tsar Alexander signed a document that Kutuzov was promoted General Field Marshall, the highest military rank. Russian sources suggest Kutuzov wrote a number of orders and letters to Rostopchin, the Moscow military governor, about saving the city or the army.[127][128] On 12 September [O.S. 31 August] 1812, the main forces of Kutuzov departed from the village, now Golitsyno and camped near Odintsovo, 20 km to the west, followed by Mortier and Joachim Murat’s vanguard.[129] Napoleon Bonaparte, who suffered from a cold and lost his voice, spent the night at Vyazyomy Manor (on the same sofa in the library) within 24 hours.[130] On Sunday afternoon the Russian military council at Fili discussed the risks and agreed to abandon Moscow without fighting. Leo Tolstoy wrote Fyodor Rostopchin was invited also and explained the difficult decision in quite a few remarkable chapters in his book War and Peace. This came at the price of losing Moscow, whose population was evacuated. Miloradovich would not give up his rearguard duties until September 14, allowing Moscow to be evacuated. Miloradovich finally retreated under a flag of truce.[131] Kutuzov withdrew to the southeast of Moscow.

On September 14, 1812, Napoleon moved into Moscow. However, he was surprised to have received no delegation from the city.[132] Before the order was received to evacuate Moscow, the city had a population of approximately 270,000 people. 48 hours later three quarters of Moscow was reduced to ashes by arson.[23] Although Saint Petersburg was the political capital at that time, Napoleon had occupied Moscow, the spiritual capital of Russia, but Tsar Alexander I decided that there could not be peaceful coexistence with Napoleon. There would be no appeasement.[133] On 19 September Murat lost sight of Kutuzov who changed direction and turned west to Podolsk and Tarutino where he would be more protected by the surrounding hills and the Nara river.[134][135][136] On 3 October Kutuzov and his entire staff arrived at Tarutino and camped there for two weeks. He controlled the three-pronged roads from Obninsk to Kaluga and Medyn so that Napoleon could not turn south or southwest. This position not only allowed him to harass the French lines of communication but also stay in contact with the Russian forces under Tormasov and Chichagov, commander of the Army of the Danube. He was also well placed to watch over the workshops and arms factories in nearby Tula and Briansk.[137]

Kutuzov’s food supplies and reinforcements were mostly coming up through Kaluga from the fertile and populous southern provinces, his new deployment gave him every opportunity to feed his men and horses and rebuild their strength. He refused to attack; he was happy for Napoleon to stay in Moscow for as long as possible, avoiding complicated movements and manoeuvres.[138][139]

Kutuzov avoided frontal battles involving large masses of troops in order to reinforce his Russian army and to wait there for Napoleon’s retreat.[140] This tactic was sharply criticised by Chief of Staff Bennigsen and others, but also by Emperor Alexander.[141] Barclay de Tolly interrupted his service for five months and settled in Nizhny Novgorod.[142][143] Each side avoided the other and seemed no longer to wish to get into a fight. On 5 October, on order of Napoleon, the French ambassador Jacques Lauriston left Moscow to meet Kutuzov at his headquarters. Kutuzov agreed to meet, despite the orders of the Tsar.[144] On 10 October Murat complained to Belliard about the lack of food and fodder; each day he lost 200 men captured by Russians. On 18 October, at dawn during breakfast, Murat’s camp in a forest was surprised by an attack by forces led by Bennigsen, known as Battle of Winkovo. Bennigsen was supported by Kutuzov from his headquarters at distance. Bennigsen asked Kutuzov to provide troops for the pursuit. However, the General Field Marshal refused.[145]

Retreat[edit]

Napoleon and his marshals struggling to manage the deteriorating situation in the retreat

The night bivouac of Napoleon’s army during the retreat from Russia by Vasily Vereshchagin. Oil on canvas. Historical Museum, Moscow, Russia.

As the Tsar refused to respond, and because of the beautiful weather, Napoleon stayed too long. On 19 October, after five weeks of occupation, the army left Moscow. The army still numbered 108,000 men, but his cavalry had been nearly destroyed. With horses exhausted or dead, commanders redirected cavalrymen into infantry units, leaving French forces helpless against Cossack fighters intensifying the guerilla warfare. With little direction or supplies, the army turned to leave the region, struggling on toward worse disaster.[146] Napoleon followed the old Kaluga road southwards towards unspoilt, richer parts of Russia to use other roads for retreat westwards to Smolensk than the one being scorched by his own army for the march eastwards.[147] Napoleon’s goal was to get around Kutuzov, but he was stopped at Maloyaroslavets on his way to Medyn in the West.

At the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, Kutuzov was able to force the French Army into using the same Smolensk road on which they had earlier moved east, the corridor of which had been stripped of food by both armies. This is often presented as an example of scorched earth tactics. Continuing to block the southern flank to prevent the French from returning by a different route, Kutuzov employed partisan tactics to repeatedly strike at the French train where it was weakest. As the retreating French train broke up and became separated, Cossack bands and light Russian cavalry assaulted isolated French units.[148]

Supplying the army in full became an impossibility because of the continuous forests. The lack of grass and feed weakened the remaining horses, almost all of which died or were killed for food by starving soldiers. Without horses, the French cavalry ceased to exist; cavalrymen had to march on foot. Lack of horses meant many cannons and wagons had to be abandoned. The loss of thousands of wagons and trained horses weakened Napoleon’s armies for the remainder of his wars. Starvation and disease took their toll, and desertion soared. Many of the deserters were taken prisoner or killed by Russian peasants. In early November 1812, when Napoleon arrived at Dorogobuzh Napoleon learned that General Claude de Malet had attempted a coup d’état in France. Badly weakened by these circumstances, the French military position collapsed. Further, defeats were inflicted on elements of the Grande Armée at Vyazma, Polotsk and Krasny. Russian armies captured the French supply depots at Polotsk, Vitebsk and Minsk, inflicting a logistical disaster on Napoleon’s fast collapsing Russian operation. However, the union with Victor, Oudinot and Dombrowski at the Bobr brought the numerical strength of the Grande Armée back up to some 49,000 French combatants as well as about 40,000 stragglers.[149] All the French corps went on to Borisov where a strategic bridge to cross the Berezina was destroyed by the Russian army. The crossing of the river Berezina was a final French calamity: two Russian armies inflicted heavy casualties on the remnants of the Grande Armée. Because of an incursion of thaw the ice on the Berezina river started to melt during the last major battle of the campaign. In military terms the escape can be considered as French tactical victory. It was a missed opportunity for the Russians who blamed Pavel Chichagov.

On 3 December Napoleon published the 29th Bulletin in which he informed the outside world for the first time of the catastrophic state of his army. He abandoned the army on 5 December and returned home on a sleigh,[150] leaving Marshal Joachim Murat in command. In the following weeks, the Grande Armée shrank further, and on 14 December 1812, it left Russian territory.

Cold weather[edit]

Following the campaign a saying arose that General Winter defeated Napoleon, alluding to the Russian Winter. Minard’s map shows that the opposite is true as the French losses were highest in the summer and autumn, due to inadequate preparation of logistics resulting in insufficient supplies, while many troops were also killed by disease. Thus the outcome of the campaign was decided long before the weather became a factor.

When winter arrived in November, the army was still equipped with summer clothing and did not have the means to protect themselves from the cold or snow.[151] It had also failed to forge caulkin shoes for the horses to enable them to traverse roads that had become iced over. The most devastating effect of the cold weather upon Napoleon’s forces occurred during their retreat. Starvation and gangrene coupled with hypothermia led to the loss of tens of thousands of men. Heavy loot was thrown away; much of the artillery was left behind. In his memoir, Napoleon’s close adviser Armand de Caulaincourt recounted scenes of massive loss, and offered a vivid description of mass death through hypothermia:

The cold was so intense that bivouacking was no longer supportable. Bad luck to those who fell asleep by a campfire! Furthermore, disorganization was perceptibly gaining ground in the Guard. One constantly found men who, overcome by the cold, had been forced to drop out and had fallen to the ground, too weak or too numb to stand. Ought one to help them along—which practically meant carrying them. They begged one to let them alone. There were bivouacs all along the road—ought one to take them to a campfire? Once these poor wretches fell asleep they were dead. If they resisted the craving for sleep, another passer-by would help them along a little farther, thus prolonging their agony for a short while, but not saving them, for in this condition the drowsiness engendered by cold is irresistibly strong. Sleep comes inevitably, and sleep is to die. I tried in vain to save a number of these unfortunates. The only words they uttered were to beg me, for the love of God, to go away and let them sleep. To hear them, one would have thought sleep was their salvation. Unhappily, it was a poor wretch’s last wish. But at least he ceased to suffer, without pain or agony. Gratitude, and even a smile, was imprinted on his discoloured lips. What I have related about the effects of extreme cold, and of this kind of death by freezing, is based on what I saw happen to thousands of individuals. The road was covered with their corpses.[152]

This befell a Grande Armée that was ill-equipped for cold weather. The French deficiencies in equipment caused by the assumption that their campaign would be concluded before the cold weather set in were a large factor in the number of casualties they suffered.[153] From the Berezina, the retreat was nothing but utter flight. The preservation of war materiel and military positions was no longer considered. When the night-time temperature dropped to minus 35 degrees Celsius it proved catastrophic for Loison’s untried soldiers. Within three days, his division of 15,000 soldiers lost 12,000 men without a battle.[83]

Summary[edit]

In Napoleon’s Russian Campaign, Riehn sums up the limitations of Napoleon’s logistics as follows:

The military machine Napoleon the artilleryman had created was perfectly suited to fight short, violent campaigns, but whenever a long-term sustained effort was in the offing, it tended to expose feet of clay. […] In the end, the logistics of the French military machine proved wholly inadequate. The experiences of short campaigns had left the French supply services completed unprepared for [..] Russia, and this was despite the precautions Napoleon had taken. There was no quick remedy that might have repaired these inadequacies from one campaign to the next. […] The limitations of horse-drawn transport and the road networks to support it were simply not up to the task. Indeed, modern militaries have long been in agreement that Napoleon’s military machine at its apex, and the scale on which he attempted to operate with it in 1812 and 1813, had become an anachronism that could succeed only with the use of railroads and the telegraph. And these had not yet been invented. [154]

Napoleon lacked the apparatus to efficiently move so many troops across such large distances of hostile territory.[155] The supply depots established by the French in the Russian interior were too far behind the main army.[156] The French train battalions tried to move forward huge amounts of supplies during the campaign, but the distances, the speed required, and missing endurance of the requisitioned vehicles that broke down too easily meant that the demands Napoleon placed on them were too great.[157] Napoleon’s demand of a speedy advance by the Grande Armée over a network of dirt roads that dissolved into deep mires resulted in killing already exhausted horses and breaking wagons.[44] As the graph of Charles Joseph Minard, given below, shows, the Grande Armée incurred the majority of its losses during the march to Moscow during the summer and autumn.

Historical assessment[edit]

Grande Armée[edit]

On 24 June 1812, around 400,000–500,000 men of the Grande Armée, the largest army assembled up to that point in European history, crossed the border into Russia and headed towards Moscow.[158][159][160] Anthony Joes wrote in the Journal of Conflict Studies that figures on how many men Napoleon took into Russia and how many eventually came out vary widely. Georges Lefebvre says that Napoleon crossed the Niemen with over 600,000 soldiers, only half of whom were from France, the others being mainly Poles and Germans.[161] Felix Markham thinks that 450,000 crossed the Neman on 25 June 1812.[162] When Ney and the rearguard recrossed the Niemen on December 14, he had barely a thousand men fit for action.[163] James Marshall-Cornwall says 510,000 Imperial troops entered Russia.[164] Eugene Tarle believes that 420,000 crossed with Napoleon and 150,000 eventually followed, for a grand total of 570,000.[165] Richard K. Riehn provides the following figures: 685,000 men marched into Russia in 1812, of whom around 355,000 were French; 31,000 soldiers marched out again in some sort of military formation, with perhaps another 35,000 stragglers, for a total of fewer than 70,000 known survivors.[3] Adam Zamoyski estimated that between 550,000 and 600,000 French and allied troops (including reinforcements) operated beyond the Niemen, of which as many as 400,000 troops died but this includes deaths of prisoners during captivity.[17]

Minard’s famous infographic (see above) depicts the march ingeniously by showing the size of the advancing army, overlaid on a rough map, as well as the retreating soldiers together with temperatures recorded (as much as 30 below zero on the Réaumur scale (−38 °C, −36 °F)) on their return. The numbers on this chart have 422,000 crossing the Neman with Napoleon, 22,000 taking a side trip early on in the campaign, 100,000 surviving the battles en route to Moscow and returning from there; only 4,000 survive the march back, to be joined by 6,000 that survived from that initial 22,000 in the feint attack northward; in the end, only 10,000 crossed the Neman back out of the initial 422,000.[166]

Imperial Russian Army[edit]

Barclay de Tolly the Minister of War and field commander of the First Western Army and General of Infantry served as the Commander in Chief of the Russian Armies. According to Tolstoy in War and Peace (Book X) he was unpopular and regarded as a foreigner by Bagration who was higher in rank but had to follow his orders. Kutuzov replaced Barclay and acted as Commander-in-chief during the retreat following the Battle of Smolensk.

As irregular cavalry, the Cossack horsemen of the Russian steppes were best suited to reconnaissance, scouting and harassing the enemy’s flanks and supply lines.

These forces, however, could count on reinforcements from the second line, which totalled 129,000 men and 8,000 Cossacks with 434 guns and 433 rounds of ammunition.

Of these, about 105,000 men were actually available for the defence against the invasion. In the third line were the 36 recruit depots and militias, which came to a total of approximately 161,000 men of various and highly disparate military values, of which about 133,000 actually took part in the defence.

Thus, the grand total of all the forces was 488,000 men, of which about 428,000 gradually came into action against the Grande Armee. This bottom line, however, includes more than 80,000 Cossacks and militiamen, as well as about 20,000 men who garrisoned the fortresses in the operational area. The majority of the officer corps came from the aristocracy.[167] About 7% of the officer corps came from the Baltic German nobility from the governorates of Estonia and Livonia.[167] Because the Baltic German nobles tended to be better educated than the ethnic Russian nobility, the Baltic Germans were often favoured with positions in high command and various technical positions.[167] The Russian Empire had no universal educational system, and those who could afford it had to hire tutors and/or send their children to private schools.[167] The educational level of the Russian nobility and gentry varied enormously depending on the quality of the tutors and/or private schools, with some Russian nobles being extremely well educated while others were just barely literate. The Baltic German nobility was more inclined to invest in their children’s education than the ethnic Russian nobility, which led to the government favouring them when granting officers’ commissions.[167] Of the 800 doctors in the Russian Army in 1812, almost all of them were Baltic Germans.[167] The British historian Dominic Lieven noted that, at the time, the Russian elite defined Russianness in terms of loyalty to the House of Romanov rather in terms of language or culture, and as the Baltic German aristocrats were very loyal, they were considered and considered themselves to be Russian despite speaking German as their first language.[167]

Sweden, Russia’s only ally, did not send supporting troops, but the alliance made it possible to withdraw the 45,000-man Russian corps Steinheil from Finland and use it in the later battles (20,000 men were sent to Riga and Polotsk).[168]

Losses[edit]

Napoleon’s retreat, surrounded by the Old Guards, by Vasily Vereshchagin

Napoleon lost more than 500,000 men in Russia.[169] Out of an original force of 615,000, only 110,000 frostbitten and half-starved survivors stumbled back.[170]

It is estimated that of the 612,000 combatants who entered Russia only 112,000 returned to the frontier. Among the casualties, 100,000 are thought to have been killed in action, 200,000 to have died from other causes, 50,000 to have been left sick in hospitals, 50,000 to have deserted, and 100,000 to have been taken as prisoners of war. The French themselves lost 70,000 in action and 120,000 wounded, as against the non-French contingents’ 30,000 and 60,000. Russian casualties have been estimated at 200,000 killed, 50,000 dispersed or deserting, and 150,000 wounded.[171]

Recent Russian studies show that Russians captured over 110,000 prisoners during the six-month-long campaign. The harsh winter, as well as popular violence, malnutrition, sickness and hardships during transportation, meant that two-thirds of these men (and women) perished within weeks of captivity. Official reports from forty-eight Russian provinces reveal that 65,503 prisoners had died in Russia by February 1813.[172]

Hay has argued that the destruction of the Dutch contingent (15,000) of the Grande Armée was not a result of the death of most of its members. Rather, its various units disintegrated and the troops scattered. Later, some of its personnel were collected and reorganised into the new Dutch army.[173]

Most of the Prussian contingent survived thanks to the Convention of Tauroggen and almost the whole Austrian contingent under Schwarzenberg withdrew successfully. The Russians formed the Russian-German Legion from other German prisoners and deserters.[168]

Russian casualties in the few open battles are comparable to the French losses, but civilian losses along the devastating campaign route were much higher than the military casualties. In total, despite earlier estimates giving figures of several million dead, around one million were killed, including civilians—fairly evenly split between the French and Russians.[17] Military losses amounted to 300,000 French, about 72,000 Poles,[174] 50,000 Italians, 80,000 Germans, and 61,000 from 16 other nations. As well as the loss of human life, the French also lost some 150,000 horses and over 1,300 artillery pieces.

The losses of the Russian armies are difficult to assess. The 19th-century historian Michael Bogdanovich assessed reinforcements of the Russian armies during the war using the Military Registry archives of the General Staff. According to this, the reinforcements totalled 134,000 men. The main army at the time of capture of Vilna in December had 70,000 men, whereas its number at the start of the invasion had been about 150,000. Thus, total losses would come to 210,000 men. Of these, about 40,000 returned to duty. Losses of the formations operating in secondary areas of operations as well as losses in militia units were about 40,000. Thus, he came up with the number of 210,000 men and militiamen.[175]

Aftermath[edit]