Византия в IV – VII веках

История Византийской империи начинается с 330 года. Тогда император Римской империи Константин перенёс столицу из Рима в город Византий, который позже будет называться Константинополем.

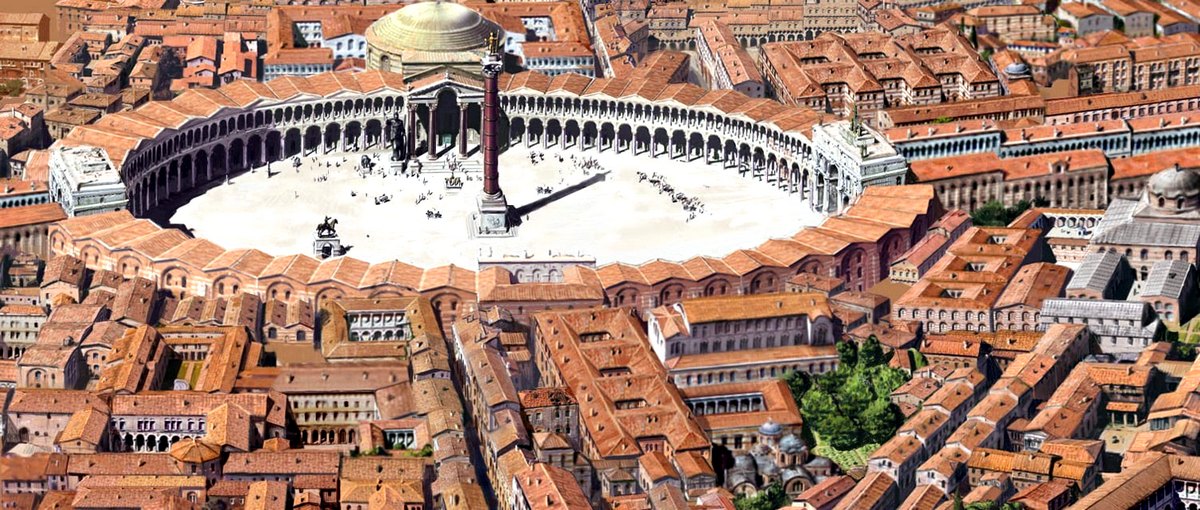

Этот город был выбран по разным причинам. Войны с варварами и внутренние конфликты не так сильно ослабили восточные земли, где находился Византий. Новая столица стояла на берегу пролива Босфор, откуда корабли могли легко выходить в Чёрное и Средиземное моря. Также на востоке имерии было распространено христианство, которое принял император. Теперь христианство станет основной культуры Византии. Константинополь вырос всего за шесть лет, с моря и суши его защищали мощные стены.

В 395 году Римская империя была разделена на Восточную (Византийскую) и Западную части. Но жители Византии по-прежнему называли себя ромеями (римлянами), новое государство – ромейской державой, а Константинополь – «Новым Римом».

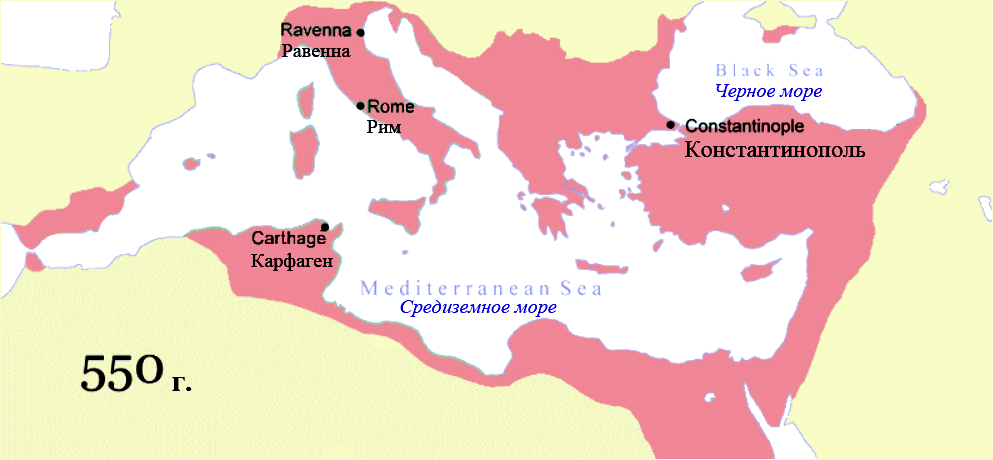

В этот период Византийская империя охватывала Балканский полуостров, Малую Азию, Сирию, Палестину, Египет, часть Месопотамии и Армении, острова Восточного Средиземноморья, земли в Крыму и на Кавказе.

Империя обладала большими ресурсами. Процветало земледелие, скотоводство, добывали железо, медь, олово, золото, серебро и квасцы. Из Египта привозили папирус. Благодаря наличию леса, мрамора и другого строительного камня, византийцы строили корабли.

В Византии было множество городов. В крупных городах (Константинополь, Алексадрия, Антиохия) жили до 300 тысяч человек. Большую часть населения империи составляли греки, но также были сирийцы, копты (египтяне, принявшие христианство), фракийцы, иллирийцы, грузины, армяне и арабы. В больших городах иудеи основывали свои общины. В 537 году был освящён собор Святой Софии.

Империя шла к своему расцвету, начавшемуся при императоре Юстиниане I (527—565). Юстиниан хотел восстановить единую Римскую империю, он завоевал государства варваров в Северной Африке, Италии и области Испании. «Кодекс Юстиниана» («Свод гражданского права») оказал влияние на развитие права в Европе.

Византия вела торговлю с Китаем и Индией. При императоре Юстиниане заняла лидирующие позиции в торговле с западными странами.

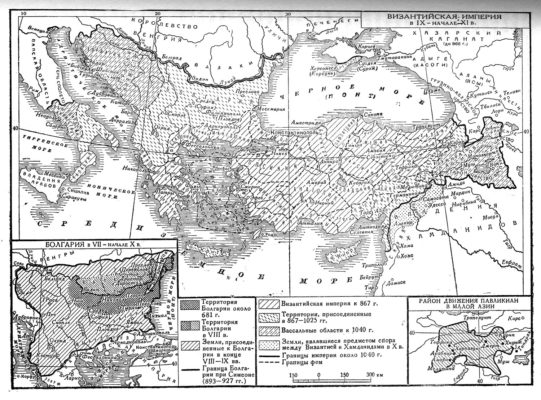

Византийская империя в VII – IX веках

Расцвет империи держался на шаткой основе завоеваний Юстиниана. Он был кратковременным, начались войны с арабами и славянами. В 717 году арабы блокировали Константинополь. Византийцы сожгли арабский флот «греческим огнём» — смесью нефти и серы, огонь который не гасится водой. Сухопутная арабская армия не смогла выдержать необычно холодной зимы. И в 718 году арабы оставили Константинополь. В 740 году император Лев III, возглавлявший оборону Константинополя, нанёс арабам решающее поражение.

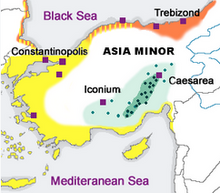

Но всё же византийские владения в Северной Африке и на Ближнем Востоке отошли восточным завоевателям. А на Балканах хозяевами стали славяне. Теперь в состав Византийской империи входили Малая Азия, области Греции и Пелопонесса, остров Крит и острова Эгейского моря.

Количество городов стало сокращаться, лишь Константинополь оставался крупным центром, в котором теперь жили всего 40 тысяч человек. Население становилось греко-славянским. Греческий язык вытеснял латинский в статусе государственного языка.

Обострялись отношения между императорской властью и церковью. В 730 году Лев III начал жестокое преследование почитателей икон. Иконы всех храмов уничтожались, их заменяли изображения креста и узоры из цветов и деревьев.

Византийская империя со второй половины века до середины XI века

Время правления императоров Македонской династии принесло новую волну подъёма Византийской империи.

Был изобретён косой парус, государство поддержало ремесленников и торговлю. Благодаря этому византийские города росли и возглавляли торговлю на Средиземном море. Константинополь стал самым богатым городом Европы.

Император Василий II, правивший в 976 — 1026 годах, вернул империи Северную Сирию, часть Месопотамии, установил контроль над Грузией и Арменией. На момент его смерти Византия была ведущим государством в Европе.

В конце XI века византийские проповедники отправились с миссиями к болгарам и сербам. Кирилл и Мефодий создали славянскую письменность, перевели на славянский язык Библию и другие церковные книги.

Император Роман IV проиграл в войне с мусульманскими завоевателями турками-сельджуками. В 1071 году после сражения при Манцикерте Византийская империя потеряла земли в Малой Азии.

Византия во второй половине XI века – первой половине XIII века

В 1054 году христианский мир раскололся на православную и католическую церкви. Но императоры династии Комнинов заключали соглашения с католическими европейскими королевствами для того, чтобы получить помощь в борьбе с турками. Комнины прекратили внутренние конфликты, отвоевали у турков побережье Малой Азии и установили власть в дунайских государствах.

В 1204 году европейские рыцари готовили поход на Египет. Но внезапно они напали на Византийскую империю и завоевали Константинополь. Теперь крестоносцы утвердили свою Латинскую империю.

Но островки Византийской империи оставались. Это были Эпирское царство, Трапезундская империя и Никейская империя, которая считалась наследницей Византийской империи.

Византийская империя в 1261 – 1453 годах

В 1261 году вошли в Константинополь, не встретив сопротивления. 15 августа император Никейской империи Михаил Палеолог вернулся в Константинополь. Византийская империя возобновила своё существование, а Михаил Палеолог коронован в Софийском соборе.

Государство было экономически ослаблено, византийские купцы и ремесленники не могли противостоять итальянцам. Но при этом династия Палеологов сохранила культуру Византии. Она повлияла на другие народы Европы, этот период назвали «палеологовским возрождением».

Возросло значение Афонского монастыря, основанного ещё в X веке. Константинопольский патриарх руководил церквями Болгарии, Сербии и Руси.

Падение Византийской империи

Конфликт с турками вынудил Палеологов снова обратиться за помощью к странам Европы. За это им пришлось пообещать, что православная церковь подчинится Папе Римскому. Первым такую попытку предпринял Михаил Палеолог в 1274 году, что вызвало сильное возмущение среди православного населения империи.

В 1439 году во Флоренции византийский император Иоанн VIII Палеолог был вынужден заключить унию с Папой Римским, то есть подчиниться католической церкви. Унию отвергли жители Константинополя, ведь теперь они теряли статус хранителей православной традиции и отрекались от истории всей империи. Византийцы стали готовиться к обороне Константинополя.

Помощь католических королевств Западной Европы оказалась слабой. Войско крестоносцев поначалу побеждало турков, но в итоге было разбито в битве при Варне в 1444 году.

В 1452 году турки построили Румелийскую крепость у пролива Босфор. Теперь Византия потеряла контроль над выходом к морю. В помощь Константинополю прибыли сухопутные силы и корабли из Генуи и Венеции. Неожиданно претендент на султанский престол Шехзаде Орхан Челеби привёл своё войско в поддержку византийцам.

29 мая 1453 года после долгой борьбы турки-османы взяли штурмом Константинополь. Поддержки со стороны западноевропейских армий оказалось недостаточно. Последний император Константин XI Палеолог погиб, а Константинополь получил название Стамбул и стал столицей Османской империи. Собор Святой Софии был преобразован в мечеть.

Через несколько лет турки захватили последние осколки Византийской империи – Морейский деспотат (1460 год) и Трапезундскую империю (1461 год). Правитель Морейского деспотата Фома Палеолог бежал в Италию, где считался законным наследником византийских императоров.

Константинопольский Софийский собор стал «вечным» символом православия. Древнейшие русские соборы в Киеве и Великом Новгороде тоже были названы в честь Святой Софии. В начале XX века по образу константинопольского собора был построен Морской Никольский собор в Кронштадте. Нынешнее здание в Стамбуле носит статус музея, это не христианский храм и не мечеть. Но появляются предложения снова преобразовать его в православный Софийский собор.

В XVI веке возникла идея «перехода империи», которая звучала как «Москва – Третий Рим». То есть Древний Рим считался центром цивилизации – «первым Римом». После падения Римской империи «вторым» Римом стал Константинополь. После захвата Константинополя на роль «третьего Рима» претендовали Белград, Великое Тырново, но они находились под властью Османской империи. Единственным мощным православным центром оставалась Москва, а московский князь Иван III женился на племяннице последнего византийского императора Софье Палеолог.

Византийская империя

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 1101.

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 1101.

После падения Западной Римской империи в 476 году под ударами германских племён, Восточная империя была единственной уцелевшей державой сохранившей традиции Античного мира. Восточная или Византийская империя сумела сберечь традиции римской культуры и государственности за годы своего существования.

Опыт работы учителем истории и обществознания — 11 лет.

Основание Византии

Историю Византийской империи принято вести с года основания римским императором Константином Великим города Константинополя в 330 году. Его ещё называли Новым Римом.

Византийская империя оказалась куда прочнее Западной Римской империи по ряду причин:

- Рабовладельческий строй в Византии в эпоху раннего средневековья был развит слабее, чем в Западной Римской империи. Население Восточной империи было на 85% свободным.

- В Византийской империи по-прежнему сохранялась крепкая связь между деревней и городом. Было развито мелкое земельное хозяйство, которое моментально приспосабливалось к меняющемуся рынку.

- Если посмотреть какую территорию занимала Византия, то можно увидеть, что в состав государства входили чрезвычайно развитые экономически, по тем временам, регионы: Греция, Сирия, Египет.

- Благодаря сильной армии и флоту Византийская империя довольно успешно выдерживала натиск варварских племён.

- В крупных городах империи сохранились торговля и ремесло. Основной производительной силой были свободные крестьяне, ремесленники и мелкие торговцы.

- Византийская империя приняло христианство в качестве основной религии. Это позволило быстрее наладить взаимоотношение с соседними странами.

Внутреннее устройство политической системы Византии не сильно отличалось от раннесредневековых варварских королевств на Западе: власть императора опиралась на крупных феодалов, состоявших из военачальников, знати славян, бывших рабовладельцев и чиновников.

Хронология Византийской империи

Историю Византийской империи принято делить на три основных периода: Ранневизантийский (IV-VIII вв), Средневизантийский (IX-XII вв) и Поздневизантийский (XIII-XV вв).

ТОП-5 статей

которые читают вместе с этой

Говоря кратко о столице Византийской империи Константинополе, нужно отметить, что главный город Византии ещё более возвысился после поглощения варварскими племенами римских провинций. Вплоть до IX века строятся здания античной архитектуры, развиваются точные науки. В Константинополе открылась первая в Европе высшая школа. Настоящим чудом творения человеческих рук стал храм Святой Софии.

Ранневизантийский период

В конце IV-начале V веков границы Византийской империи охватывали Палестину, Египет, Фракию, Балканы и Малую Азию. Восточная империя значительно опережала западные варварские королевства по строительству крупных городов, а также по развитию ремёсел и торговли. Наличие торгового и военного флота сделали Византию крупнейшей морской державой. Расцвет империи продолжался вплоть до XII века.

- 527-565 гг. правление императора Юстиниана I.

Император провозгласил идею или реконкисту:”Восстановления Римской державы”. Ради достижения этой цели Юстиниан вёл завоевательные войны с варварскими королевствами. Под ударами византийских войск пали государства вандалов в Северной Африке, были побеждены остготы в Италии.

На захваченных территориях Юстинианом I вводились новые законы носившие название “Кодекс Юстиниана”, рабы и колонны передавались прежним хозяевам. Это вызывало крайнее недовольство населения и стало в дальнейшем одной из причин заката Восточной империи.

- 610-641 гг. Правление императора Ираклия.

В результате нашествия арабов, Византия утратила Египет в 617 году. На востоке Ираклий отказался от борьбы со славянскими племенами, дав им возможность расселиться вдоль границ, используя их в качестве естественного щита против кочевых племён. Одна из главных заслуг этого императора – это возвращение в Иерусалим Животворящего Креста, который был отбит у персидского царя Хосрова II. - 717 год. Осада арабами Константинополя.

Почти целый год арабы безуспешно штурмовали столицу Византии, но в итоге так и не взяв город и откатившись с большими потерями. Во многом осада была отбита благодаря так называемому “греческому огню”. - 717-740 гг. Правление Льва III.

Годы правления этого императора отмечены тем, что Византия не только успешно вела войны с арабами, но и тем, что византийские монахи пытались распространять православную веру среди иудеев и мусульман. При императоре Льве III запрещалось почитание икон. Были уничтожены сотни ценнейших икон и других произведений искусства связанных с христианством. Иконоборчество продолжалось вплоть до 842 года.

В конце VII-начале VIII веков в Византии прошла реформа органов самоуправления. Империя стала делиться не на провинции, а на фемы. Так стали называться административные округа, которые возглавляли стратеги. Они обладали властью и самостоятельно вершили суд. Каждая фема была обязана выставлять ополчение-стратию.

Средневизантийский период

Несмотря на потерю Балканских земель Византию, по-прежнему, считают могучей державой, ведь её военный флот продолжал господствовать на Средиземном море. Период наивысшего могущества империи продолжался с 850 до 1050 годов и считается эпохой ” классической Византии”.

- 886-912 годы Правление Льва VI Мудрого.

Император проводил политику предыдущих императоров, Византия во время правления этого императора продолжает обороняться от внешних врагов. Внутри политической системы назрел кризис, который выразился в противостоянии Патриарха и императора. - 1018 год присоединение Болгарии к Византии.

Северные границы удаётся укрепит благодаря крещению болгар и славян Киевской Руси. - 1048 год турки-сельджуки под руководством Ибрагима Инала вторглись в Закавказье и взяли византийский город Эрзерум.

У Византийской империи не хватало сил для защиты юго-восточных границ. Вскоре армянские и грузинские правители признали себя зависимыми от турок. - 1046 год. Мирный договор между Киевской Русью и Византией.

Император Византии Владимир Мономах выдал замуж свою дочь Анну за киевского князя Всеволода. Не всегда отношения Руси с Византией были дружественными, было много завоевательных походов древнерусских князей против Восточной империи. Вместе с тем нельзя не отметить огромное влияние, которое оказывала византийская культура на Киевскую Русь. - 1054 год. Великая схизма.

Произошёл окончательный раскол Православной и Католической Церквей. - 1071 год. Норманнами был взят город Бари в Апулии.

Пал последний опорный пункт Византийской империи в Италии. - 1086-1091 гг. Война Византийского императора Алексея I с союзом племён печенегов и куман.

Благодаря хитрой политике императора союз племён кочевников распался, а печенегам было нанесено решительное поражение в 1091 году.

С XI века начинается постепенный упадок Византийской империи. Деление на фемы изжило себя из-за растущего числа крупных земледельцев. Государство постоянно подвергалось ударам извне, не в силах уже вести борьбу с многочисленными врагами. Главную опасность представляли сельджуки. В ходе столкновений византийцам удалось очистить от них южный берег Малой Азии.

Поздневизантийский период

С XI века увеличилась активность западноевропейских стран. Войска крестоносцев, подняв флаг “защитников Гроба Господня”, напали на Византию. Не в силах вести борьбу с многочисленными врагами, византийские императоры используют армии наёмников. На море Византия использовала флот Пизы и Венеции.

- 1122 год. Войсками императора Иоанна II Комнина было отражено вторжение печенегов.

На море ведутся непрерывные войны с Венецией. Однако, главную опасность представляли сельджуки. В ходе столкновений византийцам удалось очистить от них южный берег Малой Азии. В борьбе с крестоносцами византийцам удалось очистить Северную Сирию. - 1176 год. Поражение византийских войск при Мириокефале от турок-сельджуков.

После этого поражения Византия окончательно переходит к оборонительным войнам. - 1204 год. Константинополь пал под ударами крестоносцев.

Основу войска крестоносцев составляли французы и генуэзцы. Центральная Византия оккупированная латинянами образуется в отдельную автономию и именуется Латинской Империей. После падения столицы Византийская церковь находилась под юрисдикцией папы, верховным патриархом был назначен Томаззо Морозини. - 1261 год.

Латинская империя полностью очищена от крестоносцев, а Константинополь освобождён никейским императором Михаилом VIII Палеологом.

Византия в период правления Палеологов

В период правления Палеологов в Византии наблюдается полный упадок городов. Полуразрушенные города выглядели особенно убого на фоне цветущих деревень. Сельское хозяйство переживало подъём, вызванный высоким спросом на продукцию феодальных вотчин.

Династические браки Палеологов с королевскими дворами Западной и Восточной Европы и постоянный тесный контакт между ними, стали причиной появления собственной геральдики у византийских правителей. Род Палеологов самым первым стал иметь собственный герб.

- В 1265 году Венеция монополизировала почти всю торговлю в Константинополе.

Между Генуей и Венецией развернулась торговая война. Нередко поножовщина между иноземными купцами происходила на глазах местных зевак на городских площадях. Задушив отечественный рынок сбыта император византийские правители вызвали новую волну ненависти к себе. - 1274 год. Заключение Михаила VIII Палеолога в Лионе новой унии с папой.

Уния носила условия верховенства Папы Римского над всем христианским миром. Это окончательно раскололо общество и вызвало ряд волнений в столице. - 1341 год. Восстание в Адрианополе и Фессалониках населения против магнатов.

Восстание возглавили зилоты (ревнители). Они хотели отобрать землю и имущество у церкви и магнатов для неимущих. - 1352 год. Турками-османами захвачен Адрианополь.

Из него они сделали свою столицу. Ими была взята крепость Цимпе на Галлиполийском полуострове. Дальнейшему продвижению турок на Балканы ничего не мешало.

К началу XV века территория Византии ограничивалась Константинополем с округами, частью Центральной Греции и островами в Эгейском море.

В 1452 году турки-османы начали осаду Константинополя. 29 мая 1453 года город пал. Последний византийский император Константин II Палеолог погиб в бою.

Несмотря на заключенный союз Византии с рядом стран Западной Европы, на военную помощь рассчитывать не приходилось. Так, во время осады Константинополя турками в 1453 году, Венеция и Генуя прислали шесть военных судов и несколько сотен человек. Естественно, никакой существенной помощи оказать они не могли.

Что мы узнали?

Византийская империя оставалась единственной древней державой сохранившей свой политический и социальный строй, несмотря на Великое переселение народов. С падением Византии начинается новая эпоха в истории средних веков. Из этой статьи мы узнали сколько лет просуществовала Византийская империя и какое влияние оказало это государство на страны Западной Европы и Киевскую Русь.

Тест по теме

Доска почёта

Чтобы попасть сюда — пройдите тест.

-

Lol Lol

10/10

-

Саша Дорофеев

9/10

-

Некая Мадам

7/10

-

Наталия Пискарева

8/10

-

Геннадий Кононенко

8/10

-

Евгения Марченкова

10/10

-

Марина Загинай

10/10

-

Мария Петруша

7/10

-

Станислав Березовский

9/10

-

Ella Krug

7/10

Оценка доклада

4.5

Средняя оценка: 4.5

Всего получено оценок: 1101.

А какая ваша оценка?

Благодаря Византии достижения древнего Рима не пропали в темные века раннего Средневековья.

Содержание статьи

- Византийская империя: начало

- История Византийской империи

- Константинополь

- Расцвет Византийской империи

- Кто жил в Византийской империи?

- Исторические периоды Византийской империи

- Императоры

- Упадок Византийской империи

- Кризис и падение

Византийская империя: начало

Термин «Византийская империя» был введен в 1557 году немецким историком Иеронимом Вольфом для обозначения грекоязычной Римской империи с центром в Константинополе.

В некоторых исторических текстах Византийскую империю называют Восточной Римской империей. Начало истории Византийской империи обычно связывают с основанием в 330 году Константином Великим крупного города-крепости на Босфоре. Этот город вырос на месте маленького городка Византий и получил название Константинополь по имени своего основателя.

История Византийской империи

В 395 году, незадолго до своей смерти император Феодосий I поделил территорию Римской империи между двумя сыновьями. Таким образом появились Восточная и Западная Римские империи, окончательно освободившиеся друг от друга. Впрочем, люди того времени продолжали считать Рим единым государством.

В 476 году Западная империя, управляемая сыном Феодосия I Гонорием, прекратила свое существование из-за набегов варваров. А Восточная империя, доставшаяся старшему брату Феодосия I Аркадию, начала свой тысячелетний путь, на котором будут падения и взлеты. Именно Византийской империи предстоит стать оплотом христианства. Город Константинополь займет место Рима, его даже будут называть Новым Римом.

Константинополь

Уже в VI веке Константинополь, благодаря своему удачному расположению на пересечении морских и сухопутных путей между Западом и Востоком, Севером и Югом, станет крупнейшим торговым и культурным центром Восточного Средиземноморья.

Кроме того, Константинополь был надежно защищен от внешних врагов, находясь на полуострове, окруженным морем с трех сторон. Лишь дважды за всю историю этот город был взят внешними врагами:

- В 1204 году — крестоносцами.

- В 1453 году — османами.

Наличие плодородных равнин способствовало развитию в Византии хлебопашества, возделыванию таких злаковых культур, как пшеница, рожь, ячмень, овес, полба. В приморских районах выращивали оливу. Оливковое масло входило в ежедневный рацион жителей Византии. На юге выращивали хлопок. Также развито было виноградарство. В высокогорных районах Балкан и Малой Азии, а также на плоскогорьях — разводили скот. Рыболовство было очень распространено и рыба, наряду с хлебом, оливками и вином, входила в ежедневный рацион питания жителей Византии.

Расцвет Византийской империи

Расцвет империи пришелся на середину VI века. Побережье Средиземного моря входило в состав Византии. И, даже после территориальных потерь, когда площадь империи ограничивалась лишь двумя полуостровами — Балканами и Малой Азией и островами Эгейского моря, Византийская империя оставалась крупнейшим государством Средневековья. Это длилось и в VII-XII веках.

Кто жил в Византийской империи?

На территории Византийской империи, наряду с греками, жили

- славяне,

- евреи,

- албанцы,

- сирийцы,

- грузины,

- и другие народы.

Подавляющее большинство жителей говорило на греческом языке и только в VII веке государственным языком Византийской империи стала латынь. Византия эпохи Средневековья была цивилизованным государством с высокой плотностью населения. Византийцы отличались высоким культурным уровнем, они были прекрасными земледельцами, ремесленниками, активного участвовали в общественной жизни. Византия была империей с сильной централизованной властью.

Исторические периоды Византийской империи

Западноевропейские историки выделяют три периода в истории Византии, в то время как их российские коллеги говорят о пяти.

- 330-717 г.г. — В этот период Византия формируется и укрепляется в качестве крупного и сильного экономического государства. В это время империя борется с германскими племенами и персами.

- 717-867 г.г. — Возникает иконоборчество, борьба за уменьшение роли и влияния Церкви.

- 867-1081 г.г. — Период правления Македонской династии. Усиление империи. Завоевание Крита, Иберии, Болгарского царства и Армении.

- 1081-1261 г.г. — Крестовые походы, направленные первоначально против мусульман перерастают в войну с Византийской империей. Захват Константинополя крестоносцами.

- 1261-1453 г.г. — Война с турками-османами. Падение Византийской империи.

Императоры

С именем одного из самых известных византийских императоров Юстиниана I, который вступил на престол в 527 году, связаны судьбоносные моменты в истории Византии. В период его правления территория Византийской империи увеличилась почти в два раза. Были завоеваны новые территории:

- Италия,

- Часть Пиренейского полуострова,

- Северная Африка

Правление Юстиниана ознаменовалось войнами со славянами, аварами, персами. Хоть им и не удалось захватить больших территорий Византии, некоторые города Византийской империи были разрушены. Юстиниан, которому нужны были средства на ведение войны, обложил население высокими налогами, что привело к бунту. В то же время разразилась эпидемия чумы. Кроме того, при Юстиниане гражданская и церковная власти объединились. Все это привело к ослаблению Византийской империи.

На этом фоне для укрепления монархической власти, Юстиниан ввел понятие «Божьего помазанника». Утверждение о том, что монарх получает власть от Бога легло в основу теории, принятой впоследствии в будущих империях.

В период VI-VII веков многие территории Византийской империи были потеряны из-за войн с персами, славянами, лангобардами и аварами. Даже завоевании Армении византийским императором Ираклием I не спасло ситуацию.

В этот период Византии пришлось воевать с арабами. Угроза нависла над Константинополем, который с 673 по 678 г.г. находился в осаде. Однако применение так называемого «греческого огня» помогло правившему тогда императору Константину IV отстоять столицу Византийской империи.

В этот период греческий язык заменил латинский в качестве государственного языка.

VIII век: с именем правившего в этот период императора Льва III связана победа над арабами и предотвращение дальнейшего распада государства. Кроме того, Лев III известен в истории политикой иконоборчества. Люди, уставшие от войны с арабами возносили молитвы перед иконами в поисках выхода из кризисной ситуации. Лев III стремился ограничить влияние Церкви на государство и общество, проводя политику борьбы с иконопочитанием. Лишь в 787 году императрица Ирина вновь положила конец этой политике.

IX-X века: этот период ознаменовался напряженной ситуацией внутри страны, где из-за возрождения иконоборчества в 821-823 г.г. шла гражданская война между сторонниками и противниками этой политики. На внешних границах империи также было неспокойно. Карл Великий (король Франков) угрожал с Запада. У Восточной границы Византии угрожал Багдадский халифат, захвативший Сицилию и Крит. Не прекращались столкновения с болгарами. В этот трудный период, согласно историческим источникам, Византия впервые стала контактировать с племенами русов. Начавшееся в 867 году правления новой Македонской династии вновь принесло империи могущество и процветание.

Известные имена правителей этой династии:

- Василий I,

- Василий II,

- Иоанн I,

- Роман I,

- Константин VII,

- Никифор II.

В этот период к Византийской империи вновь был присоединен Крит, а также Юг Аппенинского полуострова и Болгарии.

XI-XIX века: в этот период произошло много событий, которые в начале привели к усилению государства, а затем к феодальной раздробленности и в конечном счете к упадку империи.

Упадок Византийской империи

Процесс феодальной раздробленности особенно усилился во время правления династии Ангелов. От империи отпадали провинции, отказываясь от Константинопольской власти. В 1187 году независимости добилась Болгария, а в 1190 — Сербия.

XIII век: в 1204 году Константинополь был захвачен крестоносцами. Византийская империя распалась на пять государств:

- Латинскую империю,

- Ахейское княжество,

- Трапезундскую империю,

- Эпирское царство,

- Никейскую империю.

15 августа 1261 года — важнейшая дата в истории Византии. В этот день монарх Никейской империи Михаил VIII Палеолог разгромил крестоносцев и вошел в Константинополь. В 1337 к восстановленной Византийской империи присоединилось Эпирское царство.

Кризис и падение

В XIV и XV веках Византия постоянно воевала с турками-османами. Византийские монархи Иоанн V и Мануил II пытались не допустить крушения империи. Они даже пошли на подписание унии, которая объединила Церкви Византии и Рима, чтобы получить от Рима военную поддержку. Это была очень непопулярная среди населения мера. В дальнейшем она привела к ослаблению государства. В XIV веке турки одержали ряд важных побед, которые привели к утрате Византийской империей значительных территорий. Византия была уже небольшим государством и не могла больше сопротивляться захватническим планам Османской империи.

30 мая 1453 года, несмотря на мужественное сопротивление защитников Константинополя во главе с Константином XI, султан Мехмед II вошел в Константинополь. Историки считают эту дату днем падения Византийской империи.

Византийскую империю называют «золотым мостом», соединившим античность и новую историю. Благодаря Византии достижения древнего Рима не пропали в темные века раннего Средневековья. Византийцы сумели не только сохранить античную культуру, но и соединить ее с христианскими ценностями. Именно благодаря византийцам, сохранились рукописи античных философов. Это помогло Европе познакомилась с культурой, которой мы обязаны возникновению Ренессанса. Древняя Русь не знала бы христианской веры без Византии. В 988 году произошло Крещение Руси.

Читайте также:

- Апостол Петр в византийском богословии

- Литургия, или введение в духовность Византии

Поскольку вы здесь…

У нас есть небольшая просьба. Эту историю удалось рассказать благодаря поддержке читателей. Даже самое небольшое ежемесячное пожертвование помогает работать редакции и создавать важные материалы для людей.

Сейчас ваша помощь нужна как никогда.

ВИЗАНТИ́Я (Восточная Римская империя, Византийская империя), государство в Средиземноморье в 4 – сер. 15 вв. со столицей в Константинополе.

Одна из крупнейших цивилизаций в мировой истории, В. сыграла величайшую историч. роль как связующее звено между античной культурой и христианским миром, между Востоком и Западом, став главнейшим центром распространения православия.

План Константинополя. 1-я треть 15 в. Художник К. Буондельмонте. Библиотека Лауренциана (Флоренция).

Визант. империя возникла в результате обособления вост. части Рим. империи (см. в ст. Рим Древний). В 330 Константин Великий основал на месте небольшого городка Визáнтий на Босфоре крупный город-крепость, дав ему своё имя. В 5 в. Константинополь окончательно занял место Рима в качестве новой столицы империи (её также именовали Новым Римом). Назв. «Византи́я» (от г. Визáнтий) условно – его ввели в оборот зап.-европ. учёные 16 в. Сами жители В. называли своё гос-во Романией, продолжая считать её (вплоть до османского завоевания) Рим. империей, а себя – ромеями (т. е. римлянами). Расположение новой столицы на пересечении морских и сухопутных путей между Западом и Востоком, Севером и Югом обусловило её превращение уже в 6 в. в самый крупный и благоустроенный город Европы и Ближнего Востока, в важнейший торговый и культурный центр всего Вост. Средиземноморья. Выгодным было и стратегич. расположение новой столицы – на полуострове, защищённом с трёх сторон морем. Внешние враги брали Константинополь за его 11-вековую историю только дважды: крестоносцы в 1204 и османы в 1453.

Территория и население

«Константин и Елена». Миниатюра из Евангелия. 15 в. Российская национальная библиотека (С.-Петербург).

В кон. 4 в. в пределы Вост. Рим. империи входили: Малая Азия, Сирия, Сев. Месопотамия, часть арм. и груз. земель, Палестина, Египет, Киренаика, Кипр, Родос, Крит, юж. берег Крыма, Балканский п-ов (кроме Далмации и Паннонии). В период расцвета В. в сер. 6 в. её территория (ок. 1 млн. км2) охватывала почти всё побережье Средиземного м. (которое было фактически её внутр. морем). Крупнейшим гос-вом Средневековья В. оставалась и в 7–12 вв. – после значит. территориальных потерь, когда её владения ограничивались двумя полуостровами (Балканами и Малой Азией) и островами Эгейского м. Протяжённая береговая линия со множеством бухт способствовала мореплаванию, развитию контактов провинций с центром и между собой, обмену информацией, облегчала быструю переброску по морю войск и грузов. Плодородные равнины в долинах рек во Фракии, юж. Македонии, Фессалии, на Пелопоннесе, в Вифинии, в приморских районах Малой Азии перемежались горными хребтами и плоскогорьями (Балканский хребет, Динарское нагорье, Родопы, Пинд, Тайгет – на Балканах, Понтийские и Армянские горы и Тавр – в Малой Азии).

Территория В. была богата полезными ископаемыми (золото, серебро, руды железа, меди и др., а также крупные месторождения мрамора). Экономич. устойчивости гос-ва способствовало многообразие климатич. условий – от среднеевропейского климата на севере Балкан до субтропического на юге ближневосточных провинций. Повсеместным на плодородных равнинах было хлебопашество (особенно в Египте, игравшем до сер. 7 в. роль главной житницы империи). Возделывались все известные тогда злаки: пшеница, рожь, ячмень, овёс, полба. Недород в одной части империи компенсировался урожаем в других. В некоторых регионах собирали два урожая в год. На юге, в засушливых районах, функционировала налаженная веками система ирригации. Культивирование оливы было высоко развито в приморских районах (т. н. оливковый пояс проходил на Балканах через юж. Фракию, юж. Македонию и Сев. Грецию). Оливки и оливковое масло, наряду с хлебом и вином, входили в ежедневный рацион значит. части жителей империи. Выращивали на юге и хлопок. Широко распространены были также виноградарство, садоводство и огородничество. На высокогорьях и плоскогорьях Балкан и Малой Азии было развито скотоводство: разводили крупный и мелкий (особенно в Каппадокии) рогатый скот, лошадей, ослов и мулов (в Вифинии, на Пелопоннесе, к северу от Балканского хребта), а также свиней. Тягловой силой в земледелии и для перевозки грузов служили быки и буйволы. Положение морской державы обусловило повсеместное развитие рыболовства (рыба была одним из гл. продуктов питания жителей столицы).

Гостиница в Дейр-Симъане, близ монастыря Святого Симеона Столпника (Северная Сирия). 479.

Территории более 20 совр. стран в разное время частично или полностью входили в состав В., и визант. период – часть их нац. истории. В период раннего Средневековья В. была, в сущности, единственным цивилизованным гос-вом в Европе и одним из двух (наряду с Ираном) на Ближнем Востоке. В В. были выше плотность населения, его культурный уровень и производственные навыки в земледелии и ремесле, византийцев отличало активное участие в обществ. жизни и в культурном взаимодействии с окружающим миром. Многообразным был и этнич. состав (греки составляли не более половины подданных империи, на Балканах жили также славяне, влахи, албанцы, в вост. провинциях – армяне, грузины, сирийцы, евреи, копты и др.). Ведущая роль принадлежала грекам. Сохраняя родные языки в своей этнич. среде, большинство подданных-негреков владели греч. языком, который с 7 в. сменил латинский в качестве гос. языка империи.

Объединяющим фактором служили прежде всего единство гос. строя, сильная центр. власть, конфессиональная и церковная общность, единое право и судопроизводство, культурное единство (выработанные веками обществ. порядки, ритм жизни, обычаи, нормы поведения), вера в незыблемость имперских порядков (т. н. таксис). Содействовали сплочению также служба крестьян в фемном ополчении, общие нормы и методы взыскания гос. налогов (в т. ч. круговая порука перед фиском), континуитет городской жизни, имперская служба почты и казённых дорог, удобные мор. коммуникации. Огромным было нивелирующее влияние Константинополя – гигантского центра управления, средоточия верховной власти, законов, источника идей, стандартов, критериев и т. п.

Исторический очерк

Офиц. раздел Рим. империи на Западную и Восточную в 395 завершил обособление вост. провинций. После падения в 476 Зап. Рим. империи В. оказалась единственной продолжившей самостоят. существование частью быв. единой Рим. империи (поэтому мн. учёные считают началом истории В. не 330, а кон. 5 в. или кон. 6 – сер. 7 вв.).

В историч. науке наиболее распространено деление истории В. на три периода: ранневизантийский (4 – 1-я пол. 7 вв.), средневизантийский (сер. 7 – кон. 12 вв.) и поздневизантийский (13 – сер. 15 вв.).

Ранневизантийский период (4 – 1-я пол. 7 вв.)

«Византийский император». Мрамор. 12 в. Афродисий(?) (Малая Азия). Дамбартон-Окс (Вашингтон).

Архив «Православной энциклопедии»

Государственное устройство. Особенностью раннего периода явилось разложение позднеантичного воен.-бюрократич. режима и начало становления В. как ср.-век. феод. монархии. Между Рим. империей и Вост. Рим. империей существовала непосредственная преемственность в системе гос. устройства, в осн. сохранявшаяся в В. на протяжении нескольких веков. В нач. 6 в. империя была разделена на две префектуры (Иллирик с центром в г. Фессалоники и Восток с центром в Константинополе); префектуры – на диоцезы (в Иллирике их было 2, в префектуре Восток – 5); диоцезы – на провинции. Сам Константинополь, кроме того, являлся особой префектурой во главе с эпархом, который ведал хозяйств. жизнью столицы, организацией суда и полицией. Его власть в Константинополе уподобляли царской, «только без порфиры».

Верховной властью (законодательной, исполнительной, судебной) обладал император. Император «христианского царства» (βασιλεία τῶν Χριστιανῶν; одно из названий В.) как теоретически единственный повелитель ойкумены – всего христианского мира – претендовал также в эпоху становления европ. варварских королевств и на высший авторитет среди них. Однако, в отличие от варварских стран, принцип наследственности высшей власти в самой В. не был признан официально. Переход власти к новому государю во многом зависел от синклита (сената, греч. ή σύγϰλητος, лат. senatus), армии, высшего духовенства, а иногда – и от жителей Константинополя. Поэтому императоры прибегали к соимператорству, коронуя при жизни близких родственников (чаще всего сыновей).

Унаследовала Вост. Рим. империя от Римской и саму теорию власти, основанную на античной традиции и рим. имперских идеалах и дополненную в 5–6 вв. христианским монархическим принципом (император считался избранником Божиим и отцом подданных). Оформилось к 7 в. и учение об идеальном государе – обладателе высших добродетелей (за образец был взят Константин Великий). Под влиянием традиций античных полисов и греко-рим. демократии императора В. воспринимали как служителя общества (магистрат) – не как господина всех граждан, а как лучшего из них. Этой теорией нередко оправдывали и низложение императоров, как не отвечавших по моральным качествам своему высокому назначению. Обожествлялся скорее не сам император, а его трон, т. е. сама империя, её гос. и обществ. строй, основанный на незыблемых принципах, менять которые (вводить новшества) не полагалось и самим императорам.

«Феодосий I с сыновьями и придворными на ипподроме Константинополя». Рельеф на основании обелиска Феодосия I на площади Ат-Мейдан в Стамбуле. Ок. 390.

Архив «Православной энциклопедии»

Важной особенностью обществ. жизни В. была т. н. вертикальная социальная подвижность – следствие непрерывных войн, которые В. вела чаще, чем любое др. государство Европы и Ближнего Востока. Слой высших сановников нуждался в постоянном пополнении. Значит. количество лиц низкого происхождения вливалось в состав знати: путь наверх вёл зачастую не от богатства к власти, а от власти к богатству. Центр. управление по-прежнему осуществлялось в имп. дворце. Главными среди ведомств были налоговое, военное, внешних сношений и имп. имуществ. Суд был основан на писаном законе (см. раздел Право). Чиновные лица делились на строго соподчинённые ранги и разряды, иерархия которых дополнялась иерархией почётных титулов. Жалованье (руга, или рога) высших сановников в десятки и сотни раз превосходило плату рядовым чиновникам. В 4–6 вв. жители столицы объединялись в неформальные организации – димы (от греч. δῇμος, демос – народ). Димы примыкали к спортивным «партиям» ипподрома, которые различались по цвету одежд возниц, правивших колесницами в состязаниях. Самыми влиятельными были венеты и прасины. Димы обладали правом выражать возгласами одобрение или неодобрение зачитываемым в цирке указам и политике императора в целом.

Вост. Рим. империя унаследовала формы земельных отношений, сформировавшиеся в поздней Рим. империи. В Вост. Рим. империи по сравнению с Западной гораздо меньше было развито рабство, шире – слой свободного крестьянства, значит. часть которого была объединена в соседские общины. Частная собственность на пахотные участки сочеталась в них с общинной собственностью на угодья.

Главным источником пополнения казны были налоги, сбор которых являлся важнейшей функцией аппарата власти. Большинство чиновников были служащими фиска. Основу налогообложения составлял учёт размеров имущества (прежде всего пахотной земли), внесённого в налоговые описи-кадастры. Круговая порука плательщиков налога перед фиском была важной особенностью податной системы. Крупные собственники перекладывали уплату налогов на плечи зависимых крестьян. Помимо торговых пошлин и сборов со всех иных доходных объектов (мастерских, лавок), с горожан – обладателей пригородных участков взимался и поземельный налог.

Армия состояла из внутренних и пограничных частей. Б. ч. пограничных войск была размещена на р. Евфрат в Азии и на р. Дунай в Европе. Армию, насчитывавшую при полных сборах 240–300 тыс. воинов, рекрутировали из крестьян и наёмников. До сер. 7 в. воен. флот В. не имел соперников в Средиземном море.

«Патриарх Никифор I венчает на царство Михаила I Рангаве». Миниатюра из Мадридской рукописи Хроники Иоанна Скилицы. Палермо (Сицилия). 1150–75. Национальная библиотека (Мадрид).

Архив «Православной энциклопедии»

Архив «Православной энциклопедии»

Карта Иерусалима. Фрагмент напольной мозаики церкви Святого Георгия в Мадабе (Иордания). 2-я пол. 6 в.

Церковь. С сер. 4 в. христианство стало гос. религией. Возникали монастыри, широко распространилось монашество, ставшее вскоре серьёзным фактором жизни общества. К сер. 5 в. в острой борьбе была выработана православная догматика – офиц. Символ веры – и преданы анафеме др. толки и ереси в христианстве, служившие знаменем сепаратизма (арианство, несторианство, монофизитство и др.). Оформлялись иерархически соподчинённые церковные диоцезы (епископии и митрополии). В соответствии с адм.-терр. устройством происходило становление церковной организации. К сер. 4 в. большое влияние приобрели 3 крупнейшие кафедры – Рим, Александрия и Антиохия. В кон. 4 в. епископ Константинополя получил ранг патриарха и занял почётное 2-е место (после папы Римского) в иерархии. Халкидонский собор 451 (IV Вселенский, см. Вселенские соборы) утвердил за предстоятелем столичной кафедры церковную власть над епархиями трёх диоцезов: Понта, Азии и Фракии. На этом соборе был учреждён и Иерусалимский патриархат, получивший 5-е место в иерархии. Сформировалась система пяти патриархатов (пентархия): Рим. церковь (см. Римско-католическая церковь), Константинопольская православная церковь, Александрийская православная церковь, Антиохийская православная церковь, Иерусалимская православная церковь. Уже в 4 в. возникли постепенно нараставшие различия между Вост. и Зап. церквами в догматике, организации церковных учреждений и обрядности. В Вост. церкви господствовал соборный принцип – участие, помимо патриархов, высшего духовенства в решении принципиальных вопросов. Зап. церковь была строго централизованной – её глава, папа Римский, обладал непререкаемым духовным авторитетом, он также с 8 в. был правителем Рима и Папской области и оказывал серьёзное влияние на политику стран Зап. Европы. Важное отличие Вост. церкви от Западной состояло также в её большей зависимости от верховной светской власти. Выборы патриарха (а порой и епископов) целиком зависели от императора. Имел место союз империи и церкви (симфония светской и духовной власти): император обеспечивал материальное благополучие духовенства и господство в гос-ве ортодоксального христианства, а Церковь освящала его власть как боговенчанного правителя. В сер. 6 в. по размерам земельных владений Церковь мало уступала короне. За немногими исключениями, патриархи не претендовали на главенство духовной власти над светской. По сравнению с Западной, Церковь В. была более демократичной. Многовековая борьба за верховенство развернулась между папой Римским и патриархом Константинополя.

Внутренняя и внешняя политика. В 4–6 вв. в отношениях с варварами (прежде всего с готами) решалась судьба Рим. империи. На востоке внутр. кризис гос-ва был менее тяжёлым, чем на западе. Поэтому Вост. Рим. империя, в отличие от Западной, устояла в борьбе с нашествием варваров.

«Юстиниан I». Фрагмент мозаики в апсиде церкви Сан-Витале в Равенне. 546–547.

Церковь (слева) и дворец в пограничной крепости на восточной границе Византийской империи (ныне Каср-ибн-Вардан, Сирия). Ок. 560.

Со времени правления Анастасия I, а особенно при Юстиниане I, центр. власть, преследуя фискальные цели, прикрепляла крестьян к податному тяглу и упрочивала коллективную податную ответственность общин перед фиском. Казна накопила большие богатства, которые позволили Юстиниану начать войны с целью восстановления Рим. империи в её старых границах. Города в Вост. Рим. империи не переживали того упадка, что на Западе; в В. было гораздо больше городов, в т. ч. крупных. Визант. купцы господствовали в средиземноморской торговле. Главной производственной ячейкой была ремесленная мастерская, служившая также лавкой. Запросы знати, нужды армии, царского двора и церкви стимулировали произ-во высококачественных изделий. В. слыла мастерской великолепия, её золотая монета (солид, или номисма) имела хождение в Европе и на Ближнем Востоке. Юстиниан содействовал прокладке новых (в обход Ирана) торговых путей на Восток. После овладения тайной шёлкоткачества (по легенде, шелковичные коконы в посохах вынесли из Китая монахи) произ-во шёлка ещё при жизни Юстиниана было налажено в Сирии, Палестине и на Пелопоннесе и приносило казне большие доходы.

В период 30-летнего царствования Юстиниана I Вост. Рим. империя достигла наибольшего расцвета. Он укрупнил провинции, повысил налоги, ограничил крупное землевладение, запретил сановникам приобретать недвижимость в местах службы, отменил продажу должностей, заменял представителей знати на высоких постах всецело преданными ему простолюдинами.

При Юстиниане I была осуществлена кодификация римского права, был создан «Свод гражданского права» («Corpus juris civilis», см. Кодекс Юстиниана), в котором было отобрано и систематизировано богатое наследие рим. юристов. Свою программу отвоеваний Юстиниан начал с разгрома в 533–534 королевства вандалов в Сев. Африке. После 20-летних войн 535–555 пало Остготское королевство, захвачены Италия и Сицилия и юго-вост. часть Испании. Длительные войны истощали материальные и людские ресурсы. В янв. 532 в ответ на рост налогов, введение казённой монополии на торговлю продуктами и произвол имп. фаворитов вспыхнуло восстание в Константинополе, названное по кличу повстанцев «Ника» (греч. «Побеждай!»). Неспокойно было и в Сев. Африке, в Сирии и Палестине, на Балканах, в Италии. Войны на западе и борьба с повстанцами ослабили позиции империи на вост. границе. В 540 персы вторглись в Месопотамию и Сирию. В. трижды заключала мир с Ираном, платила ему дань и только в 562 добилась мира. В. удалось не допустить персов к Чёрному и Средиземному морям и удержать Лазику.

Тройная цепь крепостей на Дунае не смогла сдержать натиск варваров: тюрок – протоболгар (с 540-х гг.), аваров (с 560-х гг.), славян (с сер. 6 в.). Уже в последние годы правления Юстиниана I население было разорено, для армии не хватало рекрутов, а для наёмного войска – денег. На Балканах хозяйничали варвары. Придя в 558 из Приазовья, авары основали Аварский каганат в Паннонии, ставший до 626 главным противником В. в Европе. Особенно опасными были вторжения славян. В отличие от др. варваров, они после набегов не уходили в места своих расселений или дальше на запад, а стали заселять земли империи. В Италию в 568 вторглись лангобарды и за неск. лет покорили б. ч. Сев. Италии. Для укрепления обороны Равенны имп. Маврикий создал Равеннский экзархат, объединив гражд. и воен. власть в руках одного наместника – экзарха (экзархат стал прообразом будущей системы фем). Вскоре экзархатом с центром в Карфагене стала и Сев. Африка (Карфагенский экзархат). В 602 посланные против славян на левобережье Дуная войска восстали и ушли с границы, открыв её для переселений славян. Славяне колонизировали огромные территории Балкан. К сер. 7 в. они стали вторым по численности после греков этносом на полуострове. Многие их объединения (славинии) сохраняли свои племенные названия (известны ок. 30 из них). Стремление славян к созданию собств. государств увенчалось успехом лишь на севере Балкан. На прочих визант. землях славинии в течение 2–3 столетий были интегрированы в состав империи. Архаичная земледельч. община славян превращалась в соседскую. В свою очередь, под их влиянием окрепла и местная соседская община. Упрочившееся свободное крестьянское землевладение стало в последующем основой возрождения империи.

Поднявшие в 602 мятеж дунайские легионы посадили на трон сотника Фоку, который обрушил террор на сановную знать, что вызвало гражд. войну в Малой Азии. Спасение для неё пришло из Африки. Сын экзарха Карфагена Ираклий подошёл в 610 с карфагенским флотом к Константинополю и взял его. Фока был казнён. Став императором, Ираклий I укрепил армию. В 626 были разгромлены авары, вместе со славянами и персами осадившие столицу В. Авары перестали быть угрозой для империи, исчезла вскоре и перс. опасность: в 627–628 Иран был разгромлен В., а в 637–651 завоёван арабами.

Арабы надолго стали новым опасным врагом В. В кон. 630-х – нач. 640-х гг. они захватили Сирию, Палестину, Верхнюю Месопотамию, Египет, а ещё через полвека – Карфагенский экзархат. Лазика и Армения стали независимыми от империи. Территория империи сократилась втрое. Произошли перемены и в этнич. составе В.: натиск персов и арабов вызвал в Малой Азии отток в её внутр. районы армян и сирийцев. Арабы положили конец и господству В. на море.

Средневизантийский период (сер. 7 – кон. 12 вв.)

Средневизантийский период (сер. 7 – кон. 12 вв.) характеризуется окончат. оформлением В. как ср.-век. феод. монархии. Хотя в её обществ.-политич. строе по-прежнему сохранялись некоторые институты поздней Рим. империи, более существенным стало сходство В. с феод. государствами Зап. Европы. В 12 в. большинство визант. крестьян оказалось в зависимости от земельных собственников, развивалось условное землевладение, сложилась сословная структура общества. Данный период обычно делят на три этапа. Рубежом между двумя первыми считают сер. 9 в., между вторым и третьим – кон. 11 в.

«Кузница». Изображение на пластине. Слоновая кость. 10–11 вв. Константинополь. Музей Метрополитен (Нью-Йорк).

Первый этап (сер. 7 – сер. 9 вв.). В этот период в осн. был преодолён кризис, вызванный варварскими нашествиями, и началось оформление новых гос. и обществ. структур В. Свободное крестьянское землевладение стало осн. формой земельной собственности и с.-х. произ-ва. Сохранились лишь отд. крупные имения – они принадлежали в осн. гос-ву, храмам и монастырям. Наиболее важные сведения о жизни визант. деревни содержит Земледельческий закон (нач. 8 в.). Подобно зап. Варварским правдам, он был записью обычного права. Согласно данным этого памятника, соседская община переживала тогда время интенсивного развития, среди общинников шёл процесс имущественной дифференциации. Однако в 8 – сер. 9 вв. община ещё сохраняла устойчивость.

Существенно иным было положение в городах. Нашествия варваров, разрыв торговых связей, сокращение спроса поредевшей знати ударили прежде всего по экономике городов. Мелкие и средние города аграризировались, ремёсла переживали упадок, торговля замерла. Только в крупных городах (Константинополе, Фессалониках, Никее, Трапезунде, Эфесе) нужды властей и церкви, спрос иноземцев на предметы роскоши не дали ремеслу угаснуть. Возрождение товарно-денежных отношений началось в 9 в. прежде всего в столице В., обретавшей прежнюю славу центра произ-ва высококачественных изделий. После потери вост. провинций с негреческим населением вырос удельный вес греков в гос-ве. К сер. 7 в. главу гос-ва стали обозначать греч. титулом «василевс» вместо лат. «император». Его статус уже не связывался с идеей выборности государя на главную должность (магистрат). Василевс (император) становился ср.-век. монархом. Компромисс с рим. традицией выразился в прибавлении к его титулу определения «римский» (официальной стала формула «василевс ромеев»).

«Греческий огонь». Миниатюраиз Мадридской рукописи Хроники Иоанна Скилицы. Палермо (Сицилия). 1150–75. Национальная библиотека (Мадрид).

Архив «Православной энциклопедии»

Три главных врага угрожали империи в этот период: протоболгары, славяне и арабы. Последние оставались самым опасным врагом В. на востоке вплоть до сер. 9 в. Захватив б. ч. вост. провинций, арабы не раз осаждали Константинополь с суши и с моря. В 678 византийцы впервые с успехом применили против них греческий огонь, уничтожив флот врага. В 717–718 арабы в последний раз безуспешно попытались захватить столицу В., после чего до 1-й пол. 9 в. борьба с арабами шла с переменным успехом. Слав. племена в 7 в. расселились на значит. территориях В., сохраняя свой быт и культуру. В 681 между р. Дунай и Балканским хребтом, где уже расселились славяне, возникло новое гос-во – Болгария. Его основало пришедшее из Приазовья племя протоболгар, которые частью привлекли к себе в союзники, а частью подчинили местных славян. Болгария в течение трёх с половиной веков враждовала с В. на Балканах. В 811 в борьбе с ханом Крумом погиб имп. Никифор I.

Критическое положение В. в 7 в. снова потребовало концентрации всей полноты воен. и гражд. власти в провинциях в одних руках. Эту власть над новыми воен.-адм. округами (фемами) получили стратиги (военачальники). Ополчение фемы составляли стратиоты – военнообязанные крестьяне, внесённые вместе с их участками в воен. каталоги. С интеграцией славян в состав подданных империи они становились налогоплательщиками и также вносились в воинские каталоги фем. Первые фемы возникли при Ираклии в Малой Азии. Во 2-й пол. 9 в. фемный строй в целом утвердился на территории империи. Он позволил реформировать и усилить армию, отразить врагов и начать отвоёвывать потерянные земли.

«Распятие Христа на Голгофе» (внизу – два иконоборца замазывают известью образ Христа). Миниатюра из Хлудовской Псалтири. 2-я пол. 9 в. Исторический музей (Москва).

Архив «Православной энциклопедии»

В ходе этих войн стратиги малоазийских фем обрели огромную власть, уходя из-под контроля центра. В нач. 8 в. императоры стали дробить фемы. На гребне недовольства стратигов к власти пришёл один из них – стратиг фемы Анатолики Лев III Исавр. Он видел задачу в том, чтобы подавить сепаратизм, не ослабив при этом войско и не нанеся ущерба чиновной знати. Он счёл возможным удовлетворить интересы тех и других за счёт сокровищ монастырей, приобретших огромные богатства и влияние. В 726 Лев III объявил почитание икон и мощей святых идолопоклонством. Иконоборчество длилось более столетия. В него были вовлечены все слои населения. Монастыри подвергались погромам, монахов принуждали к вступлению в брак. Сокровища монастырей переходили в казну и к воен. верхушке. С кон. 8 в. иконоборчество стало ослабевать. И социальная внутр. напряжённость, и междунар. обстановка требовали от правящих кругов единения сил. Два года (821–823) столицу осаждал узурпатор, один из мятежных военачальников в Малой Азии, славянин по происхождению, Фома Славянин. Он был разбит и казнён. Иконоборчество не нашло поддержки у населения империи. Первоначально в 787 на 7-м Вселенском соборе в Никее, а затем окончательно 11.3.843 на Поместном соборе в Константинополе иконопочитание было восстановлено. Иконоборцев, живых и мёртвых, предали анафеме. Немало сил отняла и борьба с приверженцами дуалистич. ереси павликиан. Они создали на востоке империи своебразное объединение с центром в г. Тефрика. Армия империи уничтожила неск. десятков тысяч еретиков. Только в 879 Тефрика была взята, а вождь павликиан Хрисохир убит.

Второй этап (сер. 9 – кон. 11 вв.). В этот период произошло утверждение в В. феодализма и окончат. оформление визант. ср.-век. монархии. В ходе отвоевания земель у варваров и подавления оппозиц. движений императоры упрочили право своей собственности на все земли империи, не входившие в состав частных и общинных. На части гос. земель создавались доходные имения короны и учреждений правительства, а остальные составили гигантский фонд, который император использовал в качестве могущественного средства своей социальной политики.

Юридич. и социальное положение крестьянина зависело от особенностей его землепользования. Свободные собственники своих участков платили в казну гл. поземельный налог, помимо др. налогов и повинностей в пользу гос-ва. Строго соблюдался принцип «солидарной ответственности» перед фиском за налог с заброшенных участков соседей. Общинники были обязаны также в складчину вооружать обедневших стратиотов. С правления Никифора I в деревне стал взиматься «капникон» («подымное»), т. е. подворная подать, независимо от имущественного состояния домохозяев. Среди зависимых крестьян ведущую роль играли парики (безземельные крестьяне, получившие от землевладельца участок с обязательством поселиться на земле господина и ежегодно платить ему ренту частью урожая, деньгами или отработками на домене). В 10–11 вв. размер ренты в В. определял обычай, приравнивавший взносы париков к арендной плате, более чем вдвое превышавшей поземельный налог. Поскольку господин перекладывал на зависимых крестьян также казённые платежи со своей земли, платежи париков втрое превышали налог с крестьян – собственников своих участков. Когда же господин получал налоговую льготу, присваиваемый им казённый налог становился, т. о., по своему социальному содержанию (вместе с парическим взносом за участок) частью феод. ренты. Хотя парик юридически был полноправным подданным империи, оказавшись в сфере частного права, он попадал и в личную зависимость.

Быстрое распространение парикии на рубеже 9–10 вв. вело к сокращению налоговых поступлений в казну и к падению численности ополчений; к тому же сама корона, стремясь обеспечить трудом париков собств. поместья, увидела в крупных земельных собственниках своих конкурентов. Зимой 927/928, после катастрофич. недорода, империю поразил жестокий голод. Спасаясь от гибели, крестьяне за бесценок продавали свои участки или отдавали право собственности на них богатым и влиятельным лицам («динатам», т. е. сильным), становясь их париками.

Политика правивших в 867–1056 императоров Македонской династии отражала интересы чиновничьей бюрократии. В течение столетия, с 920-х гг. до 1020-х гг., они издали серию законов (новелл), пытаясь помешать динатам захватывать земли сельских общин. Было утверждено право общинников на преимущественную покупку земли своих односельчан, а затем и земли динатов. Проданную менее 30 лет назад крестьянскую землю безвозмездно возвращали прежнему собственнику. Тогда же были введены детально разработанные инструкции (податные уставы) для чиновников о правилах сбора налогов и методах защиты прав казны. Поскольку стратиоты также становились париками (обычно стратигов), участки стратиотов были объявлены неотчуждаемыми. Менее состоятельных стратиотов принуждали служить в пехоте или на флоте. Но старое фемное ополчение приходило в упадок. Социальный состав армии менялся. Её ударной силой становилась тяжеловооружённая конница, на службу в которой привлекали мелких и средних вотчинников. Т. н. македонское законодательство лишь затормозило процесс оскудения мелкого крестьянского землевладения, но не оградило его от поглощения крупной феод. собственностью. Сравнительно с вотчинами в странах Зап. Европы визант. крупным владениям был присущ ряд особенностей: они обычно намного уступали западным по размерам и не составляли сплошных массивов; крупная земельная собственность в В. не имела иерархич. структуры; вассально-ленные отношения не получили в империи развития, иерархия ограничивалась лишь одной ступенью (император – бенефициарий); условные держания феодалов от короны проистекали из передачи им казённых налогов, т. е. дарования права на взимание в свою пользу налоговых сумм с того или иного податного округа. В сер. 10 в. возник особый вид пожалования – прония. В 11–12 вв. её жаловали на срок жизни (в награду за воен. службу) с правом управления областью, платящей налоги. Даже крупных феодалов в В. не освобождали от всех налогов, не имели они и полного судебного иммунитета: право высшей юрисдикции оставалось у центр. власти. Верный путь к отмене ограничений землевладельч. (гл. обр. военная) знать видела в возведении на престол ставленника из своей среды. Суть конфликта состояла в том, какая из форм эксплуатации возобладает: централизованная (в интересах бюрократии) или частновладельческая (в угоду воен. знати). Борьба этих группировок определяла политич. жизнь В. в 10–11 вв.

Свободное ремесло и торговля в возрождающихся с сер. 9 в. крупных городах были организованы в корпорации – проф. сообщества, созданные не на принудительной (как позднеантичные коллегии), а на добровольной основе. Утверждённые эпархом правила для 22 корпораций столицы были сведены в 10 в. в сб. «Книга эпарха» (предписывались объёмы производства, запасы сырья, время торговли, нормы прибыли). Несмотря на ряд ограничений, ремесло и торговля в В. процветали. Оживились и внешние торговые связи. Крупнейшим торговым центром всего европ. Средневековья оставался Константинополь. Большую роль в торговле играли Фессалоники. В период правления Македонской династии шло укрепление центр. власти. К нач. 10 в. число центр. ведомств достигло 60. Огромное значение сохраняли ведомства налогов, царских имуществ и внешних сношений. Сильным средством политики в руках императоров было пожалование почётных титулов. Синклит играл серьёзную роль лишь во время мятежей и при малолетних императорах. С 1030-х гг. мятежи полководцев участились. В болг., серб. и груз. фемах, входивших ранее в самостоят. гос-ва, усиливалась борьба за независимость, угрожавшая единству страны.

«Обращение болгар к византийскому императору Михаилу III с просьбой о крещении. Крещение болгар». Миниатюра из Радзивилловской летописи. Конец 15 в. Библиотека Российской академии наук (С.-Петербург)….

«Кирилл и Мефодий переводят церковные книги на славянский язык». Миниатюра из Радзивилловской летописи. Конец 15 в. Библиотека Российской академии наук (С.-Петербург).

Главными врагами В. в 9–11 вв. оставались болгары и арабы. В 860–890-х гг. В. стремилась обеспечить мир на сев. границах, активно занимаясь христианизацией языч. народов. Был организован ряд церковных миссий (в 860–861 в Хазарию, в 863 в Великую Моравию, затем на Русь, в Болгарию и в серб. земли). В 865–866 Болгария приняла крещение от В. Протесты папства, претендовавшего здесь на свою церковную супрематию, были отвергнуты. В 870-х гг. были крещены сербы. Миссии в Хазарию и Моравию возглавляли церковные и культурные деятели В., родные братья из Фессалоник Константин (в монашестве Кирилл) и Мефодий (см. Кирилл и Мефодий). В Моравию они прибыли с изобретённой ими слав. грамотой и переводами богослужебных книг. Через 20 лет ученики просветителей принесли слав. азбуку и в Болгарию. Так было положено начало письм. культуре юж. и вост. славян.

«Взятие Алеппо войсками Никифора II Фоки». Миниатюра из Мадридской рукописи Хроники Иоанна Скилицы. Палермо (Сицилия). 1150–75. Национальная библиотека (Мадрид).

На рубеже 9–10 вв., после ряда воен. успехов основателя Македонской династии Василия I Македонянина, ситуация резко изменилась. Царь Болгарии Симеон, приняв титул «василевса болгар и ромеев», претендовал на трон В., ведя с ней упорные войны. Арабы овладели почти всей Сицилией, угрожали Юж. Италии, захватили Кипр и Крит. В 904 они разграбили Фессалоники. Положение В. улучшилось лишь в сер. 10 в. В Болгарии начались смуты. Распался Арабский халифат. Имп. Никифор II Фока, реформировав армию, сумел отвоевать Сев. Месопотамию, значит. часть Сирии, Крит и Кипр, утвердить своё влияние в Армении и Грузии. Победы Иоанна I Цимисхия упрочили положение. Василий II Болгаробойца начал войны за подчинение Болгарии. В 1018 Болгария была завоёвана, а сербы и хорваты признали зависимость от империи.

Наступивший с 1030-х гг. упадок центр. власти и воен. сил был связан с раздорами в правящих кругах и династич. кризисом, начавшимся после смерти (1025) бездетного Василия II Болгаробойцы. Большие поборы с горожан и порча монеты влекли спад ремёсел и торговли. Восставали жители городов на торговых путях, требуя снижения налогов и торговых пошлин. Крупнейшим было восстание в столице в апр. 1042. Восставшие захватили часть дворца и сожгли налоговые списки. С последней четв. 10 в. воен. знать усилила борьбу за престол. В 1030–80-х гг. сменилось 10 императоров, из которых 6 были низложены. Императоры сознательно ослабляли армию и заменяли полководцев гражд. вельможами, что не замедлило дать результаты: на востоке империю теснили турки-сельджуки, на Балканах – вторгшиеся из Причерноморья печенеги. Почти незаметным на этом фоне оказалось событие, имевшее серьёзные последствия для визант. и мировой истории. Летом 1054 в обстановке усиливавшихся распрей между приверженцами зап. и вост. обряда в Юж. Италии в столицу В. прибыли послы (легаты) папы. Острые дебаты между легатами и патриархом Константинополя по вопросам догматики и о пределах супрематии завершились взаимным преданием сторонами анафеме друг друга. Произошло разделение церквей (схизма).

В 1071 сельджуки разбили армию В. при Манцикерте (в Армении). Имп. Роман IV Диоген попал в плен. Сельджуки овладели почти всей Арменией и Малой Азией, основав на земле В., в центре полуострова, своё гос-во – Иконийский султанат. В том же 1071 норманны взяли последний принадлежавший империи в Италии город Бари (в Апулии).

«Погружение в море патриархом Фотием и императором Михаилом III ризы Пресвятой Богородицы во время осады русами Константинополя». Миниатюра из Радзивилловской летописи. Конец 15 в. Библиотека Российск…

С древними русами византийцы сталкивались уже на рубеже 8–9 вв.: русы нападали на владения В. в Крыму (Херсон) и на юж. побережье Чёрного м. В 860 русы осадили Константинополь, опустошив его окрестности. Столкновение завершилось договором. Часть знатной верхушки Руси крестилась (как оказалось, формально, ненадолго; крещение же Руси произошло в 988/989). Летом 907 войска русов снова появились на Босфоре, прибыв частично морем, частично по суше. В. пошла на большие уступки. По договорам 907/911 русы получили право беспошлинной торговли в Константинополе. В. обязалась бесплатно содержать и размещать в столице послов и купцов Руси, прибывавших каждое лето по «пути из варяг в греки». Главными товарами русов были меха и рабы, а особым спросом у них пользовался шёлк. Выгодными для русов были и условия их воен. службы в качестве союзников В. Они совершили ещё неск. походов на В., защищая свои торговые интересы (941, 968–971, 1043). Втянутый империей в 967 в её войну с Болгарией, кн. Святослав Игоревич пытался закрепиться на Балканах, но потерпел поражение от войск В. в 971. В 987, сознавая невозможность одолеть мятежного полководца Варду Фоку, Василий II попросил о срочной помощи кн. Владимира. Князь поставил условие – выдать за него замуж сестру императора царевну Анну. Условие было принято, а Владимир обязался принять христианство до бракосочетания. Отряд русов разгромил узурпатора, но Василий II не спешил отправлять Анну на Русь. Владимир взял визант. г. Херсон в Крыму, побудив императора выполнить договор.

«Крещение Владимира». Миниатюра из Радзивилловской летописи. Конец 15 в. Библиотека Российской академии наук (С.-Петербург).

Князь принял крещение, и брак состоялся; Херсон был возвращён В. 6-тысячный отряд русов остался на службе в империи. В 988/989 с крещения киевлян началась христианизация Руси. Широкий доступ на Русь христианской культуре был открыт. На Русь проникала не только греч., но и слав. грамота. Большую роль в этом сыграла Болгария, где слав. письменность была освоена столетием раньше. Уже в нач. 11 в. на Афоне появились рус. монахи, а в 12 в. был основан рус. Пантелеимонов монастырь, ставший важным центром рус.-визант. культурных связей. Регулярные торговые и культурные связи Руси с В. и её владениями в Крыму прервались на долгий срок только после захвата Константинополя латинянами в 1204 и разорения монголо-татарами Киева в 1240.

Третий этап (кон. 11 – кон. 12 вв.). Новое обострение борьбы за власть завершилось победой воен. аристократии: в 1081 она возвела на престол своего ставленника, основателя новой династии Алексея I Комнина. Комнины сумели отсрочить гибель В., но упрочить надолго её гос. систему не смогли. В аграрном строе в В. в кон. 11–12 вв. появились две противоположные тенденции: подъём с.-х. произ-ва и углубление процесса политич. дезинтеграции. Расцвет экономики феод. вотчин не укреплял гос. систему, но, напротив, ускорял её разложение. В интересах упрочения центр. власти Комнинам необходимо было сохранить контроль над крупным землевладением, но не ущемить при этом интересы воен. знати, которая привела Алексея I к власти. Решая эту проблему, он искал опору прежде всего у членов обширного рода Комнинов и знатных семей, связанных с ними родством. Им в первую очередь давалось освобождение от налогов и делались пожалования; их он назначал и на важнейшие посты в гос-ве, наделяя самыми почётными титулами. Мануил I Комнин (1143–80), нарушая кодифицированное право, стал отдавать в пронию земли свободных крестьян. Условная земельная собственность быстро превращалась в полную наследственную, а свободные крестьяне – в париков. Сближение социальной структуры визант. феод. общества с зап.-европ. отразилось и в нравах знати: в В. проникала западная мода, устраивались турниры, утверждался культ рыцарской чести.

Начавшийся в 9–10 вв. подъём ремесла и торговли привёл к временному расцвету провинц. городов. Монетная реформа Алексея I оздоровила денежное обращение. Укрепились торговые связи сельской округи с городом. Близ крупных вотчин устраивались ярмарки. Положение стало ухудшаться в 11 в. – ранее всего в столице. С падением налоговых поступлений с крестьян росли поборы казны с горожан, которые были лишены каких бы то ни было налоговых, торговых, политич. привилегий. Попытки торгово-ремесленной верхушки защищать свои интересы сурово пресекались. Иноземные негоцианты получали от императоров в обмен на воен. поддержку торговые льготы и платили пошлины в 2–3 раза меньше, чем визант. купцы, или не платили их вовсе. К кон. 12 в. признаки упадка ярко проявились в столице. Мелочная опека, система ограничений, высокие налоги и пошлины душили корпорации. Визант. ремесло и торговля пришли в упадок. Итал. товары стали превосходить визант. по качеству, но были значительно дешевле. Горожанам в В. противостояли и магнаты, и гос-во. Союз центр. власти с городами против феод. знати в империи не сложился.

«Христос, коронующий Иоанна II Комнина и его сына Алексея». Миниатюра из Евангелия Иоанна II Комнина. Константинополь. Ок. 1128. Библиотека Ватикана (Рим).

К началу правления Алексея I В. оказалась зажатой внешним врагом в клещи с востока и с запада: почти вся Малая Азия была в руках турок-сельджуков, а норманны, переправившись из Италии на адриатич. побережье, захватили город-крепость Диррахий, разорили Эпир, Македонию, Фессалию. Печенеги, форсировавшие Дунай, находились у ворот столицы. В 1085 с помощью венецианцев, полученной в обмен за право беспошлинной торговли, норманнов удалось вытеснить с Балкан. Ещё более грозной была опасность, исходившая от кочевников. Печенеги стали обосновываться на землях империи. Сельджуки вступили с ними в сговор о совместном штурме Константинополя. Алексею I удалось разжечь вражду между печенегами и половцами, также вторгшимися на Балканы. С их помощью весной 1091 орда печенегов была почти полностью уничтожена во Фракии. Благодаря дипломатич. искусству Алексея I, после побед рыцарей 1-го крестового похода над сельджуками, погрязшими в междоусобиях, были возвращены Никея, северо-запад Малой Азии и юж. побережье Чёрного м. (1096–1097). Глава Антиохийского кн-ва Боэмунд Тарентский признал себя вассалом визант. императора. Сын Алексея I Иоанн II Комнин в 1122 разгромил новые полчища печенегов, вновь вторгшихся во Фракию и Македонию. Попытка Иоанна II лишить торговых привилегий венецианцев, обосновавшихся в Константинополе и др. городах империи, оказалась неудачной: флот венецианцев в ответ разорил острова и побережье В., и Иоанн II вернул им льготы. Главная опасность по-прежнему исходила от сельджуков. Иоанн II отвоевал у них юж. берег Малой Азии; в борьбе же с крестоносцами за бывшие земли В. на Ближнем Востоке сумел овладеть только сев. Сирией.

В сер. 12 в. центр внешнеполитич. активности В. снова переместился на Балканы. Мануил I отразил новый натиск сицилийских норманнов на адриатич. побережье, Грецию и острова Эгейского м. Ему удалось подчинить Сербию, вернуть Далмацию, поставить в вассальную зависимость Венгрию. Победы стоили огромной затраты сил и средств. Турки-сельджуки возобновили натиск и в 1176 разгромили армию Мануила I при Мириокефале. Империя на всех границах перешла к обороне. Ухудшение положения империи на междунар. арене и смерть Мануила I осложнили и внутриполитич. обстановку. В 1180 власть захватила придворная камарилья во главе с регентшей при малолетнем Алексее II Комнине Марией Антиохийской (женой Мануила I). Казна расхищалась, растаскивались арсеналы и снаряжение воен. флота. Мария открыто благоволила итальянцам. В 1182 вспыхнуло восстание. Повстанцы обратили в руины итал. кварталы. На гребне нар. недовольства в 1183 к власти пришёл Андроник I Комнин. Мария, а затем и Алексей II были убиты. Андроник I стремился обуздать произвол чиновников, снизил налоги, отменил их откуп, искоренял коррупцию, ликвидировал т. н. береговое право. Междунар. положение В. между тем ухудшалось: ещё в 1183 венгры овладели Далмацией, в 1184 отпал Кипр. В 1185 норманны заняли Ионические о-ва. Тогда же враги Андроника I в Константинополе обратились за помощью к норманнам, и те снова вторглись на Балканы, захватили и подвергли беспощадному разгрому Фессалоники. Вельможи разжигали растущее среди жителей столицы недовольство, во всём обвиняя Андроника I. Разразился бунт. Андроника I схватила на улице и растерзала толпа. Троном овладели представители земельной аристократии в лице Исаака II Ангела. Он практически ликвидировал контроль центр. власти над крупными владениями. Земли со свободными крестьянами щедро раздавались в пронии. Имения, конфискованные Андроником I, возвращались прежним хозяевам. Снова были повышены налоги. В правление Исаака II и его брата Алексея III Ангела Комнина, захватившего власть в 1195, процесс разложения аппарата центр. власти быстро прогрессировал. Уже в кон. 12 в. истерзанная внутр. распрями и непрерывными ударами извне В. стала распадаться: некоторые магнаты Пелопоннеса, юж. Македонии, Фессалии и Малой Азии отказывали в повиновении центр. власти. В результате крупного восстания болгар в 1186 была восстановлена болг. государственность, создано Второе Болгарское царство, а в 1190 стали независимыми и сербы. В 1191 крестоносцами был захвачен Кипр.

Бежавший в кон. 1201 в Италию сын свергнутого с престола Исаака II Алексей (IV) прибыл в Венецию, где был назначен сбор войска (4-го крестового похода), готовившегося к войне против султана Египта. На обещания Алексея вождям крестоносцев уплатить за восстановление его (и его отца) на престоле В. колоссальную сумму они выразили полную готовность изменить цели похода: вместо отплытия в Египет – двинуться на штурм Константинополя. Летом 1203 рыцари 4-го крестового похода подступили к его стенам. Алексей III, отказавшись от организации обороны города и оставив трон Исааку II и его сыну Алексею IV Ангелу, бежал из столицы. Уплатить сполна обещанную сумму предводителям похода они не смогли. Восставшие жители столицы свергли их с престола. Вожди рыцарей в марте 1204 приняли решение не только овладеть Константинополем, но также завоевать и разделить территорию самой восточной христианской империи. Лишённый последних сил, дезорганизованный, не получивший никакой помощи извне, Константинополь стал лёгкой добычей крестоносцев. 12.4.1204 они штурмом взяли город, подвергнув его жестокому грабежу.

Поздневизантийский период (13 – сер. 15 вв.)

Децентрализация империи (1204–61). В этот период В., даже временно восстановленная, продолжала слабеть, раздираемая внутр. смутами и тяжёлыми ударами извне. На территории прежней Визант. империи возникло неск. государств, среди них – Латинская империя, управляемая зап.-европ. сеньорами и венецианцами (при формальном сохранении греч. титулов и обычаев визант. двора), с центром в Константинополе. В неё вошли территория Фракии и северо-запад малоазийского п-ова. Её вассалами были Фессалоникское королевство, Афино-Фиванское герцогство и Ахейское (Морейское) кн-во. Венеция получила 3/8 империи, 3/8 Константинополя и множество островов (включая Крит и Эвбею) и приморских городов, заняв ключевые позиции в торговле Востока и Запада. После захвата Константинополя латинянами Вселенским патриархом был объявлен венецианский клирик Томмазо Морозини. Визант. церковь была поставлена под прямую юрисдикцию папы. Не признавшее примат папы греч. духовенство заменялось католическим, отправлялось в изгнание. Православие становилось знаменем сопротивления завоевателям. Резиденцией греч. Вселенского патриарха стала Никея. Полностью завоевать территорию В. крестоносцы не смогли. На не занятых ими землях сложились три греч. государства: в Вифинии – Никейская империя, на юж. берегу Чёрного м., с помощью груз. царицы Тамар, – Трапезундская империя, а на побережье Адриатики (от Диррахия до Коринфского зал.) – Эпирское царство.