-

-

April 28 2021, 19:03

- История

- Путешествия

- Cancel

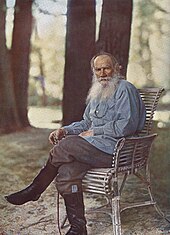

Ответ на этот вопрос даёт ведущий научный сотрудник Института русского языка им. В. В. Виноградова кандидат филологических наук Н. А. Еськова в статье «О каком „мире“ идет речь в „Войне и мире“?», опубликованной в журнале «Наука и жизнь» (2002, № 6). Н. А. Еськова развенчивает один из мифов, согласно которому Л. Н. Толстой под словом «мир» имел в виду народ, общество и даже вселенную.

«Хорошо известно, что два слова-омонима, сейчас пишущиеся одинаково, в дореволюционной орфографии различались: написанию миръ — с и (так называемым «восьмеричным») передавало слово, имеющее значения «отсутствие ссоры, вражды, несогласия, войны; лад, согласие, единодушие, приязнь, дружба, доброжелательство; тишина, покой, спокойствие» (см. Толковый словарь В. И. Даля). Написание мiръ — с i («десятеричным») соответствовало значениям «вселенная, земной шар, род человеческий».

Казалось бы, вопрос о том, какой «мир» фигурирует в названии романа Толстого, не должен и возникать: достаточно выяснить, как печаталось это название в дореволюционных изданиях романа! <…> В комментарии к роману в 90-томном полном собрании сочинений содержится указание на это издание 1913 года под редакцией П. И. Бирюкова — единственное, в котором заглавие было напечатано с i (см. т. 16, 1955, с. 101-102).

Обратившись к этому изданию, я обнаружила, что написание мiръ представлено в нем всего один раз, при том, что в четырех томах заглавие воспроизводится восемь раз: на титульном листе и на первой странице каждого тома. Семь раз напечатано миръ и лишь один раз — на первой странице первого тома – мiръ».

Автор статьи резюмирует: «Издание романа Л. Толстого «Война и мир» (1913) под редакцией П. И. Бирюкова — единственное, в котором на одной странице прошла опечатка в слове «мир»: вместо и было напечатано i».

Кстати, на другие языки название романа переводится как «La guerre et la paix», «War and Peace», «Krieg und Frieden», «Guerre e pace».

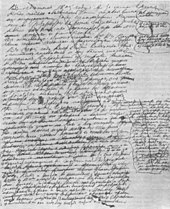

А вот и толстовская рукопись.

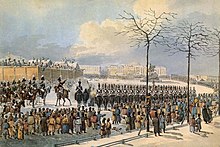

Одно из первых изданий (или первое).

Front page of War and Peace, first edition, 1869 (Russian) |

|

| Author | Leo Tolstoy |

|---|---|

| Original title | Война и миръ |

| Translator | The first translation of War and Peace into English was by American Nathan Haskell Dole, in 1899 |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian, with some French |

| Genre | Novel (Historical novel) |

| Publisher | The Russian Messenger (serial) |

|

Publication date |

Serialised 1865–1867; book 1869 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 1,225 (first published edition) |

| Followed by | The Decembrists (Abandoned and Unfinished) |

|

Original text |

Война и миръ at Russian Wikisource |

| Translation | War and Peace at Wikisource |

War and Peace (Russian: Война и мир, romanized: Voyna i mir; pre-reform Russian: Война и миръ; [vɐjˈna i ˈmʲir]) is a literary work by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy that mixes fictional narrative with chapters on history and philosophy. It was first published serially, then published in its entirety in 1869. It is regarded as Tolstoy’s finest literary achievement and remains an internationally praised classic of world literature.[1][2][3]

The novel chronicles the French invasion of Russia and the impact of the Napoleonic era on Tsarist society through the stories of five Russian aristocratic families. Portions of an earlier version, titled The Year 1805,[4] were serialized in The Russian Messenger from 1865 to 1867 before the novel was published in its entirety in 1869.[5]

Tolstoy said that the best Russian literature does not conform to standards and hence hesitated to classify War and Peace, saying it is «not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less a historical chronicle». Large sections, especially the later chapters, are philosophical discussions rather than narrative.[6] He regarded Anna Karenina as his first true novel.

Composition history[edit]

Tolstoy’s notes from the ninth draft of War and Peace, 1864.

Tolstoy began writing War and Peace in 1863, the year that he finally married and settled down at his country estate. In September of that year, he wrote to Elizabeth Bers, his sister-in-law, asking if she could find any chronicles, diaries or records that related to the Napoleonic period in Russia. He was dismayed to find that few written records covered the domestic aspects of Russian life at that time, and tried to rectify these omissions in his early drafts of the novel.[7] The first half of the book was written and named «1805». During the writing of the second half, he read widely and acknowledged Schopenhauer as one of his main inspirations. Tolstoy wrote in a letter to Afanasy Fet that what he had written in War and Peace is also said by Schopenhauer in The World as Will and Representation. However, Tolstoy approaches «it from the other side.»[8]

The first draft of the novel was completed in 1863. In 1865, the periodical Russkiy Vestnik (The Russian Messenger) published the first part of this draft under the title 1805 and published more the following year. Tolstoy was dissatisfied with this version, although he allowed several parts of it to be published with a different ending in 1867. He heavily rewrote the entire novel between 1866 and 1869.[5][9] Tolstoy’s wife, Sophia Tolstaya, copied as many as seven separate complete manuscripts before Tolstoy considered it ready for publication.[9] The version that was published in Russkiy Vestnik had a very different ending from the version eventually published under the title War and Peace in 1869. Russians who had read the serialized version were eager to buy the complete novel, and it sold out almost immediately. The novel was immediately translated after publication into many other languages.[citation needed]

It is unknown why Tolstoy changed the name to War and Peace. He may have borrowed the title from the 1861 work of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: La Guerre et la Paix («War and Peace» in French).[4] The title may also be a reference to the Roman Emperor Titus, (reigned 79-81 AD) described as being a master of «war and peace» in The Twelve Caesars, written by Suetonius in 119. The completed novel was then called Voyna i mir (Война и мир in new-style orthography; in English War and Peace).[citation needed]

The 1805 manuscript was re-edited and annotated in Russia in 1893 and has been since translated into English, German, French, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Albanian, Korean, and Czech.

Tolstoy was instrumental in bringing a new kind of consciousness to the novel. His narrative structure is noted not only for its god’s eye point of view over and within events, but also in the way it swiftly and seamlessly portrayed an individual character’s view point. His use of visual detail is often comparable to cinema, using literary techniques that resemble panning, wide shots and close-ups. These devices, while not exclusive to Tolstoy, are part of the new style of the novel that arose in the mid-19th century and of which Tolstoy proved himself a master.[10]

The standard Russian text of War and Peace is divided into four books (comprising fifteen parts) and an epilogue in two parts. Roughly the first half is concerned strictly with the fictional characters, whereas the latter parts, as well as the second part of the epilogue, increasingly consist of essays about the nature of war, power, history, and historiography. Tolstoy interspersed these essays into the story in a way that defies previous fictional convention. Certain abridged versions remove these essays entirely, while others, published even during Tolstoy’s life, simply moved these essays into an appendix.[11]

Realism[edit]

The novel is set 60 years before Tolstoy’s day, but he had spoken with people who lived through the 1812 French invasion of Russia. He read all the standard histories available in Russian and French about the Napoleonic Wars and had read letters, journals, autobiographies and biographies of Napoleon and other key players of that era. There are approximately 160 real persons named or referred to in War and Peace.[12]

He worked from primary source materials (interviews and other documents), as well as from history books, philosophy texts and other historical novels.[9] Tolstoy also used a great deal of his own experience in the Crimean War to bring vivid detail and first-hand accounts of how the Imperial Russian Army was structured.[13]

Tolstoy was critical of standard history, especially military history, in War and Peace. He explains at the start of the novel’s third volume his own views on how history ought to be written.

Language[edit]

Cover of War and Peace, Italian translation, 1899.

Although the book is mainly in Russian, significant portions of dialogue are in French. It has been suggested[14] that the use of French is a deliberate literary device, to portray artifice while Russian emerges as a language of sincerity, honesty, and seriousness. It could, however, also simply represent another element of the realistic style in which the book is written, since French was the common language of the Russian aristocracy, and more generally the aristocracies of continental Europe, at the time.[15] In fact, the Russian nobility often knew only enough Russian to command their servants; Tolstoy illustrates this by showing that Julie Karagina, a character in the novel, is so unfamiliar with her country’s native language that she has to take Russian lessons.

The use of French diminishes as the book progresses. It is suggested that this is to demonstrate Russia freeing itself from foreign cultural domination,[14] and to show that a once-friendly nation has turned into an enemy. By midway through the book, several of the Russian aristocracy are eager to find Russian tutors for themselves.

Background and historical context[edit]

The novel spans the period from 1805 to 1820. The era of Catherine the Great was still fresh in the minds of older people. Catherine had made French the language of her royal court.[16] For the next 100 years, it became a social requirement for the Russian nobility to speak French and understand French culture.[16]

The historical context of the novel begins with the execution of Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien in 1805, while Russia is ruled by Alexander I during the Napoleonic Wars. Key historical events woven into the novel include the Ulm Campaign, the Battle of Austerlitz, the Treaties of Tilsit, and the Congress of Erfurt. Tolstoy also references the Great Comet of 1811 just before the French invasion of Russia.[17]: 1, 6, 79, 83, 167, 235, 240, 246, 363–364

Tolstoy then uses the Battle of Ostrovno and the Battle of Shevardino Redoubt in his novel, before the occupation of Moscow and the subsequent fire. The novel continues with the Battle of Tarutino, the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, the Battle of Vyazma, and the Battle of Krasnoi. The final battle cited is the Battle of Berezina, after which the characters move on with rebuilding Moscow and their lives.[17]: 392–396, 449–481, 523, 586–591, 601, 613, 635, 638, 655, 640

Principal characters[edit]

War and Peace simple family tree.

War and Peace detailed family tree.

The novel tells the story of five families—the Bezukhovs, the Bolkonskys, the Rostovs, the Kuragins, and the Drubetskoys.

The main characters are:

- The Bezukhovs

- Count Kirill Vladimirovich Bezukhov: the father of Pierre

- Count Pyotr Kirillovich («Pierre») Bezukhov: The central character and often a voice for Tolstoy’s own beliefs or struggles. Pierre is the socially awkward illegitimate son of Count Kirill Vladimirovich Bezukhov, who has fathered dozens of illegitimate sons. Educated abroad, Pierre returns to Russia as a misfit. His unexpected inheritance of a large fortune makes him socially desirable.

- The Bolkonskys

- Prince Nikolai Andreich Bolkonsky: The father of Andrei and Maria, the eccentric prince possesses a gruff exterior and displays great insensitivity to the emotional needs of his children. Nevertheless, his harshness often belies hidden depth of feeling.

- Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky: A strong but skeptical, thoughtful and philosophical aide-de-camp in the Napoleonic Wars.

- Princess Elisabeta «Lisa» Karlovna Bolkonskaya (also Lise) – née Meinena. Wife of Andrei. Also called «little princess».

- Princess Maria Nikolayevna Bolkonskaya: Sister of Prince Andrei, Princess Maria is a pious woman whose father attempted to give her a good education. The caring, nurturing nature of her large eyes in her otherwise plain face is frequently mentioned. Tolstoy often notes that Princess Maria cannot claim a radiant beauty (like many other female characters of the novel) but she is a person of very high moral values and of high intelligence.

- The Rostovs

- Count Ilya Andreyevich Rostov: The pater-familias of the Rostov family; hopeless with finances, generous to a fault. As a result, the Rostovs never have enough cash, despite having many estates.

- Countess Natalya Rostova: The wife of Count Ilya Rostov, she is frustrated by her husband’s mishandling of their finances, but is determined that her children succeed anyway

- Countess Natalya Ilyinichna «Natasha» Rostova: A central character, introduced as «not pretty but full of life», romantic, impulsive and highly strung. She is an accomplished singer and dancer.

- Count Nikolai Ilyich «Nikolenka» Rostov: A hussar, the beloved eldest son of the Rostov family.

- Sofia Alexandrovna «Sonya» Rostova: Orphaned cousin of Vera, Nikolai, Natasha, and Petya Rostov and is in love with Nikolai.

- Countess Vera Ilyinichna Rostova: Eldest of the Rostov children, she marries the German career soldier, Berg.

- Pyotr Ilyich «Petya» Rostov: Youngest of the Rostov children.

- The Kuragins

- Prince Vasily Sergeyevich Kuragin: A ruthless man who is determined to marry his children into wealth at any cost.

- Princess Elena Vasilyevna «Hélène» Kuragina: A beautiful and sexually alluring woman who has many affairs, including (it is rumoured) with her brother Anatole.

- Prince Anatole Vasilyevich Kuragin: Hélène’s brother, a handsome and amoral pleasure seeker who is secretly married yet tries to elope with Natasha Rostova.

- Prince Ippolit Vasilyevich (Hippolyte) Kuragin: The younger brother of Anatole and perhaps most dim-witted of the three Kuragin children.

- The Drubetskoys

- Prince Boris Drubetskoy: A poor but aristocratic young man driven by ambition, even at the expense of his friends and benefactors, who marries Julie Karagina for money and is rumored to have had an affair with Hélène Bezukhova.

- Princess Anna Mihalovna Drubetskaya: The impoverished mother of Boris, whom she wishes to push up the career ladder.

- Other prominent characters

- Fyodor Ivanovich Dolokhov: A cold, almost psychopathic officer, he ruins Nikolai Rostov by luring him into an outrageous gambling debt after unsuccessfully proposing to Sonya Rostova. He is also rumored to have had an affair with Hélène Bezukhova and he provides for his poor mother and hunchbacked sister.

- Adolf Karlovich Berg: A young German officer, who desires to be just like everyone else and marries the young Vera Rostova.

- Anna Pavlovna Scherer: Also known as Annette, she is the hostess of the salon that is the site of much of the novel’s action in Petersburg and schemes with Prince Vasily Kuragin.

- Maria Dmitryevna Akhrosimova: An older Moscow society lady, good-humored but brutally honest.

- Amalia Evgenyevna Bourienne: A Frenchwoman who lives with the Bolkonskys, primarily as Princess Maria’s companion and later at Maria’s expense.

- Vasily Dmitrich Denisov: Nikolai Rostov’s friend and brother officer, who unsuccessfully proposes to Natasha.

- Platon Karataev: The archetypal good Russian peasant, whom Pierre meets in the prisoner-of-war camp.

- Osip Bazdeyev: a Freemason who convinces Pierre to join his mysterious group.

- Bilibin: A diplomat with a reputation for cleverness, an acquaintance of Prince Andrei Bolkonsky.

In addition, several real-life historical characters (such as Napoleon and Prince Mikhail Kutuzov) play a prominent part in the book. Many of Tolstoy’s characters were based on real people. His grandparents and their friends were the models for many of the main characters; his great-grandparents would have been of the generation of Prince Vassily or Count Ilya Rostov.

Plot summary[edit]

Book One[edit]

The novel begins in July 1805 in Saint Petersburg, at a soirée given by Anna Pavlovna Scherer, the maid of honour and confidante to the dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna. Many of the main characters are introduced as they enter the salon. Pierre (Pyotr Kirilovich) Bezukhov is the illegitimate son of a wealthy count, who is dying after a series of strokes. Pierre is about to become embroiled in a struggle for his inheritance. Educated abroad at his father’s expense following his mother’s death, Pierre is kindhearted but socially awkward, and finds it difficult to integrate into Petersburg society. It is known to everyone at the soirée that Pierre is his father’s favorite of all the old count’s illegitimate progeny. They respect Pierre during the soiree because his father, Count Bezukhov, is a very rich man, and as Pierre is his favorite, most aristocrats think that the fortune of his father will be given to him even though he is illegitimate.

Also attending the soirée is Pierre’s friend, Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky, husband of Lise, a charming society favourite. He is disillusioned with Petersburg society and with married life; feeling that his wife is empty and superficial, he comes to hate her and all women, expressing patently misogynistic views to Pierre when the two are alone. Pierre does not quite know what to do with this, and is made uncomfortable witnessing the marital discord. Pierre had been sent to St Petersburg by his father to choose a career for himself, but he is quite uncomfortable because he cannot find one and everybody keeps on asking about this. Andrei tells Pierre he has decided to become aide-de-camp to Prince Mikhail Ilarionovich Kutuzov in the coming war (The Battle of Austerlitz) against Napoleon in order to escape a life he cannot stand.

The plot moves to Moscow, Russia’s former capital, contrasting its provincial, more Russian ways to the more European society of Saint Petersburg. The Rostov family is introduced. Count Ilya Andreyevich Rostov and Countess Natalya Rostova are an affectionate couple but forever worried about their disordered finances. They have four children. Thirteen-year-old Natasha (Natalia Ilyinichna) believes herself in love with Boris Drubetskoy, a young man who is about to join the army as an officer. The mother of Boris is Anna Mikhaylovna Drubetskaya who is a childhood friend of the countess Natalya Rostova. Boris is also the godson of Count Bezukhov (Pierre’s father). Twenty-year-old Nikolai Ilyich pledges his love to Sonya (Sofia Alexandrovna), his fifteen-year-old cousin, an orphan who has been brought up by the Rostovs. The eldest child, Vera Ilyinichna, is cold and somewhat haughty but has a good prospective marriage to a Russian-German officer, Adolf Karlovich Berg. Petya (Pyotr Ilyich) at nine is the youngest; like his brother, he is impetuous and eager to join the army when of age.

At Bald Hills, the Bolkonskys’ country estate, Prince Andrei departs for war and leaves his terrified, pregnant wife Lise with his eccentric father Prince Nikolai Andreyevich and devoutly religious sister Maria Nikolayevna Bolkonskaya, who refuses to marry the son of a wealthy aristocrat on account of her devotion to her father and suspicion that the young man would be unfaithful to her.

The second part opens with descriptions of the impending Russian-French war preparations. At the Schöngrabern engagement, Nikolai Rostov, now an ensign in the hussars, has his first taste of battle. Boris Drubetskoy introduces him to Prince Andrei, whom Rostov insults in a fit of impetuousness. He is deeply attracted by Tsar Alexander’s charisma. Nikolai gambles and socializes with his officer, Vasily Dmitrich Denisov, and befriends the ruthless Fyodor Ivanovich Dolokhov. Bolkonsky, Rostov and Denisov are involved in the disastrous Battle of Austerlitz, in which Prince Andrei is badly wounded as he attempts to rescue a Russian standard.

The Battle of Austerlitz is a major event in the book. As the battle is about to start, Prince Andrei thinks the approaching «day [will] be his Toulon, or his Arcola»,[18] references to Napoleon’s early victories. Later in the battle, however, Andrei falls into enemy hands and even meets his hero, Napoleon. But his previous enthusiasm has been shattered; he no longer thinks much of Napoleon, «so petty did his hero with his paltry vanity and delight in victory appear, compared to that lofty, righteous and kindly sky which he had seen and comprehended».[19] Tolstoy portrays Austerlitz as an early test for Russia, one which ended badly because the soldiers fought for irrelevant things like glory or renown rather than the higher virtues which would produce, according to Tolstoy, a victory at Borodino during the 1812 invasion.

Book Two[edit]

Book Two begins with Nikolai Rostov returning on leave to Moscow accompanied by his friend Denisov, his officer from his Pavlograd Regiment. He spends an eventful winter at home. Natasha has blossomed into a beautiful young woman. Denisov falls in love with her and proposes marriage, but is rejected. Nikolai meets Dolokhov, and they grow closer as friends. Dolokhov falls in love with Sonya, Nikolai’s cousin, but as she is in love with Nikolai, she rejects Dolokhov’s proposal. Nikolai meets Dolokhov some time later. The resentful Dolokhov challenges Nikolai at cards, and Nikolai loses every hand until he sinks into a 43,000 ruble debt. Although his mother pleads with Nikolai to marry a wealthy heiress to rescue the family from its dire financial straits, he refuses. Instead, he promises to marry his childhood crush and orphaned cousin, the dowry-less Sonya.

Pierre Bezukhov, upon finally receiving his massive inheritance, is suddenly transformed from a bumbling young man into the most eligible bachelor in Russian society. Despite knowing that it is wrong, he is convinced into marriage with Prince Kuragin’s beautiful and immoral daughter Hélène (Elena Vasilyevna Kuragina). Hélène, who is rumored to be involved in an incestuous affair with her brother Anatole, tells Pierre that she will never have children with him. Hélène is also rumored to be having an affair with Dolokhov, who mocks Pierre in public. Pierre loses his temper and challenges Dolokhov to a duel. Unexpectedly (because Dolokhov is a seasoned dueller), Pierre wounds Dolokhov. Hélène denies her affair, but Pierre is convinced of her guilt and leaves her. In his moral and spiritual confusion, Pierre joins the Freemasons. Much of Book Two concerns his struggles with his passions and his spiritual conflicts. He abandons his former carefree behavior and enters upon a philosophical quest particular to Tolstoy: how should one live a moral life in an ethically imperfect world? The question continually baffles Pierre. He attempts to liberate his serfs, but ultimately achieves nothing of note.

Pierre is contrasted with Prince Andrei Bolkonsky. Andrei recovers from his near-fatal wound in a military hospital and returns home, only to find his wife Lise dying in childbirth. He is stricken by his guilty conscience for not treating her better. His child, Nikolai, survives.

Burdened with nihilistic disillusionment, Prince Andrei does not return to the army but remains on his estate, working on a project that would codify military behavior to solve problems of disorganization responsible for the loss of life on the Russian side. Pierre visits him and brings new questions: where is God in this amoral world? Pierre is interested in panentheism and the possibility of an afterlife.

Pierre’s wife, Hélène, begs him to take her back, and trying to abide by the Freemason laws of forgiveness, he agrees. Hélène establishes herself as an influential hostess in Petersburg society.

Prince Andrei feels impelled to take his newly written military notions to Saint Petersburg, naively expecting to influence either the Emperor himself or those close to him. Young Natasha, also in Saint Petersburg, is caught up in the excitement of her first grand ball, where she meets Prince Andrei and briefly reinvigorates him with her vivacious charm. Andrei believes he has found purpose in life again and, after paying the Rostovs several visits, proposes marriage to Natasha. However, Andrei’s father dislikes the Rostovs and opposes the marriage, insisting that the couple wait a year before marrying. Prince Andrei leaves to recuperate from his wounds abroad, leaving Natasha distraught. Count Rostov takes her and Sonya to Moscow in order to raise funds for her trousseau.

Natasha visits the Moscow opera, where she meets Hélène and her brother Anatole. Anatole has since married a Polish woman whom he abandoned in Poland. He is very attracted to Natasha and determined to seduce her, and conspires with his sister to do so. Anatole succeeds in making Natasha believe he loves her, eventually establishing plans to elope. Natasha writes to Princess Maria, Andrei’s sister, breaking off her engagement. At the last moment, Sonya discovers her plans to elope and foils them. Natasha learns from Pierre of Anatole’s marriage. Devastated, Natasha makes a suicide attempt and is left seriously ill.

Pierre is initially horrified by Natasha’s behavior but realizes he has fallen in love with her. As the Great Comet of 1811–12 streaks across the sky, life appears to begin anew for Pierre. Prince Andrei coldly accepts Natasha’s breaking of the engagement. He tells Pierre that his pride will not allow him to renew his proposal.

Book Three[edit]

The Battle of Borodino, fought on September 7, 1812, and involving more than a quarter of a million troops and seventy thousand casualties was a turning point in Napoleon’s failed campaign to defeat Russia. It is vividly depicted through the plot and characters of War and Peace.

Painting by Louis-François, Baron Lejeune, 1822.

With the help of her family, and the stirrings of religious faith, Natasha manages to persevere in Moscow through this dark period. Meanwhile, the whole of Russia is affected by the coming confrontation between Napoleon’s army and the Russian army. Pierre convinces himself through gematria that Napoleon is the Antichrist of the Book of Revelation. Old Prince Bolkonsky dies of a stroke knowing that French marauders are coming for his estate. No organized help from any Russian army seems available to the Bolkonskys, but Nikolai Rostov turns up at their estate in time to help put down an incipient peasant revolt. He finds himself attracted to the distraught Princess Maria.

Back in Moscow, the patriotic Petya joins a crowd in audience of Tzar Alexander and manages to snatch a biscuit thrown from the balcony window of the Cathedral of the Assumption by the Tzar. He is nearly crushed by the throngs in his effort. Under the influence of the same patriotism, his father finally allows him to enlist.

Napoleon himself is the main character in this section, and the novel presents him in vivid detail, both personally and as both a thinker and would-be strategist. Also described are the well-organized force of over four hundred thousand troops of the French Grande Armée (only one hundred and forty thousand of them actually French-speaking) that marches through the Russian countryside in the late summer and reaches the outskirts of the city of Smolensk. Pierre decides to leave Moscow and go to watch the Battle of Borodino from a vantage point next to a Russian artillery crew. After watching for a time, he begins to join in carrying ammunition. In the midst of the turmoil he experiences first-hand the death and destruction of war; Eugène’s artillery continues to pound Russian support columns, while Marshals Ney and Davout set up a crossfire with artillery positioned on the Semyonovskaya heights. The battle becomes a hideous slaughter for both armies and ends in a standoff. The Russians, however, have won a moral victory by standing up to Napoleon’s reputedly invincible army. The Russian army withdraws the next day, allowing Napoleon to march on to Moscow. Among the casualties are Anatole Kuragin and Prince Andrei. Anatole loses a leg, and Andrei suffers a grenade wound in the abdomen. Both are reported dead, but their families are in such disarray that no one can be notified.

Book Four[edit]

The Rostovs have waited until the last minute to abandon Moscow, even after it became clear that Kutuzov had retreated past Moscow. The Muscovites are being given contradictory instructions on how to either flee or fight. Count Fyodor Rostopchin, the commander in chief of Moscow, is publishing posters, rousing the citizens to put their faith in religious icons, while at the same time urging them to fight with pitchforks if necessary. Before fleeing himself, he gives orders to burn the city. However, Tolstoy states that the burning of an abandoned city mostly built of wood was inevitable, and while the French blame the Russians, these blame the French. The Rostovs have a difficult time deciding what to take with them, but in the end, Natasha convinces them to load their carts with the wounded and dying from the Battle of Borodino. Unknown to Natasha, Prince Andrei is amongst the wounded.

When Napoleon’s army finally occupies an abandoned and burning Moscow, Pierre takes off on a quixotic mission to assassinate Napoleon. He becomes anonymous in all the chaos, shedding his responsibilities by wearing peasant clothes and shunning his duties and lifestyle. The only people he sees are Natasha and some of her family, as they depart Moscow. Natasha recognizes and smiles at him, and he in turn realizes the full scope of his love for her.

Pierre saves the life of a French officer who enters his home looking for shelter, and they have a long, amicable conversation. The next day Pierre goes into the street to resume his assassination plan, and comes across two French soldiers robbing an Armenian family. When one of the soldiers tries to rip the necklace off the young Armenian woman’s neck, Pierre intervenes by attacking the soldiers, and is taken prisoner by the French army. He believes he will be executed, but in the end is spared. He witnesses, with horror, the execution of other prisoners.

Pierre becomes friends with a fellow prisoner, Platon Karataev, a Russian peasant with a saintly demeanor. In Karataev, Pierre finally finds what he has been seeking: an honest person of integrity, who is utterly without pretense. Pierre discovers meaning in life simply by interacting with him. After witnessing French soldiers sacking Moscow and shooting Russian civilians arbitrarily, Pierre is forced to march with the Grand Army during its disastrous retreat from Moscow in the harsh Russian winter. After months of tribulation—during which the fever-plagued Karataev is shot by the French—Pierre is finally freed by a Russian raiding party led by Dolokhov and Denisov, after a small skirmish with the French that sees the young Petya Rostov killed in action.

Meanwhile, Andrei has been taken in and cared for by the Rostovs, fleeing from Moscow to Yaroslavl. He is reunited with Natasha and his sister Maria before the end of the war. In an internal transformation, he loses the fear of death and forgives Natasha in a last act before dying.

Nikolai becomes worried about his family’s finances, and leaves the army after hearing of Petya’s death. There is little hope for recovery. Given the Rostovs’ ruin, he does not feel comfortable with the prospect of marrying the wealthy Marya Bolkonskaya, but when they meet again they both still feel love for each other. As the novel draws to a close, Pierre’s wife Hélène dies from an overdose of an abortifacient (Tolstoy does not state it explicitly but the euphemism he uses is unambiguous). Pierre is reunited with Natasha, while the victorious Russians rebuild Moscow. Natasha speaks of Prince Andrei’s death and Pierre of Karataev’s. Both are aware of a growing bond between them in their bereavement. With the help of Princess Maria, Pierre finds love at last and marries Natasha.

Epilogue in two parts[edit]

First part[edit]

Karl Kollmann depicting the Decembrist uprising in St. Petersburg, 1825.

The first part of the epilogue begins with the wedding of Pierre and Natasha in 1813. Count Rostov dies soon after, leaving his eldest son Nikolai to take charge of the debt-ridden estate. Nikolai finds himself with the task of maintaining the family on the verge of bankruptcy. Although he finds marrying women for money repugnant, Nikolai gives in to his love for Princess Maria and marries her.

Nikolai and Maria then move to her inherited estate of Bald Hills with his mother and Sonya, whom he supports for the rest of their lives. Nikolai and Maria have children together, and also raise Prince Andrei’s orphaned son, Nikolai Andreyevich (Nikolenka) Bolkonsky.

As in all good marriages, there are misunderstandings, but the couples – Pierre and Natasha, Nikolai and Maria – remain devoted. Pierre and Natasha visit Bald Hills in 1820. There is a hint in the closing chapters that the idealistic, boyish Nikolenka and Pierre would both become part of the Decembrist Uprising. The first epilogue concludes with Nikolenka promising he would do something with which even his late father «would be satisfied» (presumably as a revolutionary in the Decembrist revolt).

Second part[edit]

The second part of the epilogue contains Tolstoy’s critique of all existing forms of mainstream history. The 19th-century Great Man Theory claims that historical events are the result of the actions of «heroes» and other great individuals; Tolstoy argues that this is impossible because of how rarely these actions result in great historical events. Rather, he argues, great historical events are the result of many smaller events driven by the thousands of individuals involved (he compares this to calculus, and the sum of infinitesimals). He then goes on to argue that these smaller events are the result of an inverse relationship between necessity and free will, necessity being based on reason and therefore explicable through historical analysis, and free will being based on consciousness and therefore inherently unpredictable. Tolstoy also ridicules newly emerging Darwinism as overly simplistic, comparing it to plasterers covering over icons with plaster.

Philosophical chapters[edit]

War and Peace is Tolstoy’s longest work, consisting of 361 chapters. Of those, 24 are philosophical chapters with the author’s comments and views, rather than narrative:

- Book 3:

Part 10 — Chapters 19, 20 and 33

Part 11 — Chapter 1

- Book 4:

Part 13 — Chapter 8

Part 14 — Chapters 1, 2 and 18

- Epilogue:

Part 1 — Chapters 1 to 4

Part 2

Reception[edit]

The novel that made its author «the true lion of the Russian literature» (according to Ivan Goncharov)[20][21] enjoyed great success with the reading public upon its publication and spawned dozens of reviews and analytical essays, some of which (by Dmitry Pisarev, Pavel Annenkov, Dragomirov and Strakhov) formed the basis for the research of later Tolstoy scholars.[21] Yet the Russian press’s initial response to the novel was muted, with most critics unable to decide how to classify it. The liberal newspaper Golos (The Voice, April 3, #93, 1865) was one of the first to react. Its anonymous reviewer posed a question later repeated by many others: «What could this possibly be? What kind of genre are we supposed to file it to?.. Where is fiction in it, and where is real history?»[21]

Writer and critic Nikolai Akhsharumov, writing in Vsemirny Trud (#6, 1867) suggested that War and Peace was «neither a chronicle, nor a historical novel», but a genre merger, this ambiguity never undermining its immense value. Annenkov, who praised the novel too, was equally vague when trying to classify it. «The cultural history of one large section of our society, the political and social panorama of it in the beginning of the current century», was his suggestion. «It is the [social] epic, the history novel and the vast picture of the whole nation’s life», wrote Ivan Turgenev in his bid to define War and Peace in the foreword for his French translation of «The Two Hussars» (published in Paris by Le Temps in 1875).

In general, the literary left received the novel coldly. They saw it as devoid of social critique, and keen on the idea of national unity. They saw its major fault as the «author’s inability to portray a new kind of revolutionary intelligentsia in his novel», as critic Varfolomey Zaytsev put it.[22] Articles by D. Minayev, Vasily Bervi-Flerovsky [ru] and N. Shelgunov in Delo magazine characterized the novel as «lacking realism», showing its characters as «cruel and rough», «mentally stoned», «morally depraved» and promoting «the philosophy of stagnation». Still, Mikhail Saltykov-Schedrin, who never expressed his opinion of the novel publicly, in private conversation was reported to have expressed delight with «how strongly this Count has stung our higher society».[23] Dmitry Pisarev in his unfinished article «Russian Gentry of Old» (Staroye barstvo, Otechestvennye Zapiski, #2, 1868), while praising Tolstoy’s realism in portraying members of high society, was still unhappy with the way the author, as he saw it, ‘idealized’ the old nobility, expressing «unconscious and quite natural tenderness towards» the Russian dvoryanstvo. On the opposite front, the conservative press and «patriotic» authors (A. S. Norov and P. A. Vyazemsky among them) were accusing Tolstoy of consciously distorting 1812 history, desecrating the «patriotic feelings of our fathers» and ridiculing dvoryanstvo.[21]

One of the first comprehensive articles on the novel was that of Pavel Annenkov, published in #2, 1868 issue of Vestnik Evropy. The critic praised Tolstoy’s masterful portrayal of man at war, marveled at the complexity of the whole composition, organically merging historical facts and fiction. «The dazzling side of the novel», according to Annenkov, was «the natural simplicity with which [the author] transports the worldly affairs and big social events down to the level of a character who witnesses them.» Annekov thought the historical gallery of the novel was incomplete with the two «great raznotchintsys», Speransky and Arakcheyev, and deplored the fact that the author stopped at introducing to the novel «this relatively rough but original element». In the end the critic called the novel «the whole epoch in the Russian fiction».[21]

Slavophiles declared Tolstoy their «bogatyr» and pronounced War and Peace «the Bible of the new national idea». Several articles on War and Peace were published in 1869–70 in Zarya magazine by Nikolay Strakhov. «War and Peace is the work of genius, equal to everything that the Russian literature has produced before», he pronounced in the first, smaller essay. «It is now quite clear that from 1868 when the War and Peace was published the very essence of what we call Russian literature has become quite different, acquired the new form and meaning», the critic continued later. Strakhov was the first critic in Russia who declared Tolstoy’s novel to be a masterpiece of a level previously unknown in Russian literature. Still, being a true Slavophile, he could not fail to see the novel as promoting the major Slavophiliac ideas of «meek Russian character’s supremacy over the rapacious European kind» (using Apollon Grigoryev’s formula). Years later, in 1878, discussing Strakhov’s own book The World as a Whole, Tolstoy criticized both Grigoriev’s concept (of «Russian meekness vs. Western bestiality») and Strakhov’s interpretation of it.[24]

Among the reviewers were military men and authors specializing in war literature. Most assessed highly the artfulness and realism of Tolstoy’s battle scenes. N. Lachinov, a member of the Russky Invalid newspaper staff (#69, April 10, 1868) called the Battle of Schöngrabern scenes «bearing the highest degree of historical and artistic truthfulness» and totally agreed with the author’s view on the Battle of Borodino, which some of his opponents disputed. The army general and respected military writer Mikhail Dragomirov, in an article published in Oruzheiny Sbornik (The Military Almanac, 1868–70), while disputing some of Tolstoy’s ideas concerning the «spontaneity» of wars and the role of commander in battles, advised all the Russian Army officers to use War and Peace as their desk book, describing its battle scenes as «incomparable» and «serving for an ideal manual to every textbook on theories of military art.»[21]

Unlike professional literary critics, most prominent Russian writers of the time supported the novel wholeheartedly. Goncharov, Turgenev, Leskov, Dostoevsky and Fet have all gone on record as declaring War and Peace the masterpiece of Russian literature. Ivan Goncharov in a July 17, 1878 letter to Pyotr Ganzen advised him to choose for translating into Danish War and Peace, adding: «This is positively what might be called a Russian Iliad. Embracing the whole epoch, it is the grandiose literary event, showcasing the gallery of great men painted by a lively brush of the great master … This is one of the most, if not the most profound literary work ever».[25] In 1879, unhappy with Ganzen having chosen Anna Karenina to start with, Goncharov insisted: «War and Peace is the extraordinary poem of a novel, both in content and execution. It also serves as a monument to Russian history’s glorious epoch when whatever figure you take is a colossus, a statue in bronze. Even [the novel’s] minor characters carry all the characteristic features of the Russian people and its life.»[26] In 1885, expressing satisfaction with the fact that Tolstoy’s works had by then been translated into Danish, Goncharov again stressed the immense importance of War and Peace. «Count Tolstoy really mounts over everybody else here [in Russia]», he remarked.[27]

Fyodor Dostoevsky (in a May 30, 1871 letter to Strakhov) described War and Peace as «the last word of the landlord’s literature and the brilliant one at that». In a draft version of The Raw Youth he described Tolstoy as «a historiograph of the dvoryanstvo, or rather, its cultural elite». «The objectivity and realism impart wonderful charm to all scenes, and alongside people of talent, honour and duty he exposes numerous scoundrels, worthless goons and fools», he added.[28] In 1876 Dostoevsky wrote: «My strong conviction is that a writer of fiction has to have most profound knowledge—not only of the poetic side of his art, but also the reality he deals with, in its historical as well as contemporary context. Here [in Russia], as far as I see it, only one writer excels in this, Count Lev Tolstoy.»[29]

Nikolai Leskov, then an anonymous reviewer in Birzhevy Vestnik (The Stock Exchange Herald), wrote several articles praising highly War and Peace, calling it «the best ever Russian historical novel» and «the pride of the contemporary literature». Marveling at the realism and factual truthfulness of Tolstoy’s book, Leskov thought the author deserved the special credit for «having lifted up the people’s spirit upon the high pedestal it deserved». «While working most elaborately upon individual characters, the author, apparently, has been studying most diligently the character of the nation as a whole; the life of people whose moral strength came to be concentrated in the Army that came up to fight mighty Napoleon. In this respect the novel of Count Tolstoy could be seen as an epic of the Great national war which up until now has had its historians but never had its singers», Leskov wrote.[21]

Afanasy Fet, in a January 1, 1870 letter to Tolstoy, expressed his great delight with the novel. «You’ve managed to show us in great detail the other, mundane side of life and explain how organically does it feed the outer, heroic side of it», he added.[30]

Ivan Turgenev gradually re-considered his initial skepticism as to the novel’s historical aspect and also the style of Tolstoy’s psychological analysis. In his 1880 article written in the form of a letter addressed to Edmond Abou, the editor of the French newspaper Le XIXe Siècle, Turgenev described Tolstoy as «the most popular Russian writer» and War and Peace as «one of the most remarkable books of our age».[31] «This vast work has the spirit of an epic, where the life of Russia of the beginning of our century in general and in details has been recreated by the hand of a true master … The manner in which Count Tolstoy conducts his treatise is innovative and original. This is the great work of a great writer, and in it there’s true, real Russia», Turgenev wrote.[32] It was largely due to Turgenev’s efforts that the novel started to gain popularity with the European readership. The first French edition of the War and Peace (1879) paved the way for the worldwide success of Leo Tolstoy and his works.[21]

Since then many world-famous authors have praised War and Peace as a masterpiece of world literature. Gustave Flaubert expressed his delight in a January 1880 letter to Turgenev, writing: «This is the first class work! What an artist and what a psychologist! The first two volumes are exquisite. I used to utter shrieks of delight while reading. This is powerful, very powerful indeed.»[33] Later John Galsworthy called War and Peace «the best novel that had ever been written». Romain Rolland, remembering his reading the novel as a student, wrote: «this work, like life itself, has no beginning, no end. It is life itself in its eternal movement.»[34] Thomas Mann thought War and Peace to be «the greatest ever war novel in the history of literature.»[35] Ernest Hemingway confessed that it was from Tolstoy that he had been taking lessons on how to «write about war in the most straightforward, honest, objective and stark way.» «I don’t know anybody who could write about war better than Tolstoy did», Hemingway asserted in his 1955 Men at War. The Best War Stories of All Time anthology.[21]

Isaac Babel said, after reading War and Peace, «If the world could write by itself, it would write like Tolstoy.»[36] Tolstoy «gives us a unique combination of the ‘naive objectivity’ of the oral narrator with the interest in detail characteristic of realism. This is the reason for our trust in his presentation.»[37]

English translations[edit]

War and Peace has been translated into many languages. It has been translated into English on several occasions, starting with Clara Bell working from a French translation. The translators Constance Garnett and Aylmer and Louise Maude knew Tolstoy personally. Translations have to deal with Tolstoy’s often peculiar syntax and his fondness for repetitions. Only about 2 percent of War and Peace is in French; Tolstoy removed the French in a revised 1873 edition, only to restore it later.[14] Most translators follow Garnett retaining some French; Briggs and Shubin use no French, while Pevear-Volokhonsky and Amy Mandelker’s revision of the Maude translation both retain the French fully.[14]

List of English translations[edit]

(Translators listed.)

Translation of draft of 1863:

- Andrew Bromfield (HarperCollins, 2007). Approx. 400 pages shorter than English translations of the finished novel

Full translations:

- Clara Bell (New York: Gottsberger, 1886). Translated from a French version

- Nathan Haskell Dole (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1889)

- Leo Wiener (Boston: Dana Estes & Co., 1904)

- Constance Garnett (London: Heinemann, 1904)

- Aylmer and Louise Maude (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1922–23)

- Revised by George Gibian (Norton Critical Edition, 1966)

- Revised by Amy Mandelker (Oxford University Press, 2010)

- Rosemary Edmonds (Penguin, 1957; revised 1978)

- Ann Dunnigan (New American Library, 1968)

- Anthony Briggs (Penguin, 2005)

- Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Random House, 2007)

- Daniel H. Shubin (self-published, 2020)

Abridged translation:

- Princess Alexandra Kropotkin (Doubleday, 1949)[17]

Comparing translations[edit]

In the Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, academic Zoja Pavlovskis-Petit has this to say about the translations of War and Peace available in 2000: «Of all the translations of War and Peace, Dunnigan’s (1968) is the best. … Unlike the other translators, Dunnigan even succeeds with many characteristically Russian folk expressions and proverbs. … She is faithful to the text and does not hesitate to render conscientiously those details that the uninitiated may find bewildering: for instance, the statement that Boris’s mother pronounced his name with a stress on the o – an indication to the Russian reader of the old lady’s affectation.»

On the Garnett translation Pavlovskis-Petit writes: «her …War and Peace is frequently inexact and contains too many anglicisms. Her style is awkward and turgid, very unsuitable for Tolstoi.» On the Maudes’ translation she comments: «this should have been the best translation, but the Maudes’ lack of adroitness in dealing with Russian folk idiom, and their style in general, place this version below Dunnigan’s.» She further comments on Edmonds’s revised translation, formerly on Penguin: «[it] is the work of a sound scholar but not the best possible translator; it frequently lacks resourcefulness and imagination in its use of English. … a respectable translation but not on the level of Dunnigan or Maude.»[38]

Adaptations[edit]

Film[edit]

- The first Russian adaptation was Война и мир (Voyna i mir) in 1915, which was directed by Vladimir Gardin and starred Gardin and the Russian ballerina Vera Karalli. Fumio Kamei produced a version in Japan in 1947.

- The 208-minute-long American 1956 version was directed by King Vidor and starred Audrey Hepburn (Natasha), Henry Fonda (Pierre) and Mel Ferrer (Andrei). Audrey Hepburn was nominated for a BAFTA Award for best British actress and for a Golden Globe Award for best actress in a drama production.

- The critically acclaimed, four-part and 431-minutes long Soviet War and Peace, by director Sergei Bondarchuk, was released in 1966 and 1967. It starred Ludmila Savelyeva (as Natasha Rostova) and Vyacheslav Tikhonov (as Andrei Bolkonsky). Bondarchuk himself played the character of Pierre Bezukhov. It involved thousands of extras and took six years to finish the shooting, as a result of which the actors’ age changed dramatically from scene to scene. It won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film for its authenticity and massive scale.[citation needed] Bondarchuk’s film is considered to be the best screen version of the novel. It attracted some controversy due to the number of horses killed during the making of the battle sequences and screenings were actively boycotted in several US cities by the ASPCA.[39]

Television[edit]

- War and Peace (1972): The BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) made a television serial based on the novel, broadcast in 1972–73. Anthony Hopkins played the lead role of Pierre. Other lead characters were played by Rupert Davies, Faith Brook, Morag Hood, Alan Dobie, Angela Down and Sylvester Morand. This version faithfully included many of Tolstoy’s minor characters, including Platon Karataev (Harry Locke).[40][41]

- La guerre et la paix (2000): French TV production of Prokofiev’s opera War and Peace, directed by François Roussillon. Robert Brubaker played the lead role of Pierre.[42]

- War and Peace (2007): produced by the Italian Lux Vide, a TV mini-series in Russian & English co-produced in Russia, France, Germany, Poland and Italy. Directed by Robert Dornhelm, with screenplay written by Lorenzo Favella, Enrico Medioli and Gavin Scott. It features an international cast with Alexander Beyer playing the lead role of Pierre assisted by Malcolm McDowell, Clémence Poésy, Alessio Boni, Pilar Abella, J. Kimo Arbas, Ken Duken, Juozapas Bagdonas and Toni Bertorelli.[43]

- On 8 December 2015, Russian state television channel Russia-K began a four-day broadcast of a reading of the novel, one volume per day, involving 1,300 readers in over 30 cities.[44]

- War & Peace (2016): The BBC aired a six-part adaptation of the novel scripted by Andrew Davies on BBC One in 2016, with Paul Dano playing the lead role of Pierre.[45][46]

Music[edit]

- English progressive rock band Yes’s song «The Gates of Delirium» from their 1974 album Relayer was inspired by War and Peace.

Opera[edit]

- Initiated by a proposal of the German director Erwin Piscator in 1938, the Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev composed his opera War and Peace (Op. 91, libretto by Mira Mendelson) based on this epic novel during the 1940s. The complete musical work premièred in Leningrad in 1955. It was the first opera to be given a public performance at the Sydney Opera House (1973).[47]

Theatre[edit]

- The first successful stage adaptations of War and Peace were produced by Alfred Neumann and Erwin Piscator (1942, revised 1955, published by Macgibbon & Kee in London 1963, and staged in 16 countries since) and R. Lucas (1943).

- A stage adaptation by Helen Edmundson, first produced in 1996 at the Royal National Theatre with Richard Hope as Pierre and Anne-Marie Duff as Natasha, was published that year by Nick Hern Books, London. Edmundson added to and amended the play[48] for a 2008 production as two 3-hour parts by Shared Experience, again directed by Nancy Meckler and Polly Teale.[49] This was first put on at the Nottingham Playhouse, then toured in the UK to Liverpool, Darlington, Bath, Warwick, Oxford, Truro, London (the Hampstead Theatre) and Cheltenham.

- A musical adaptation by OBIE Award-winner Dave Malloy, called Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 premiered at the Ars Nova theater in Manhattan on October 1, 2012. The show is described as an electropop opera, and is based on Book 8 of War and Peace, focusing on Natasha’s affair with Anatole.[50] The show opened on Broadway in the fall of 2016, starring Josh Groban as Pierre and Denée Benton as Natasha. It received twelve Tony Award nominations including Best Musical, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Original Score, and Best Book of a Musical.

- A stage adaptation by Carlos Be in Spanish, first produced by LaJoven and directed by José Luis Arellano. Its premiere is scheduled for January 2023 at the Círculo de Bellas Artes of Madrid.[51]

Radio[edit]

- The BBC Home Service broadcast an eight-part adaptation by Walter Peacock from 17 January to 7 February 1943 with two episodes on each Sunday. All but the last instalment, which ran for one and a half hours, were one hour long. Leslie Banks played Pierre while Celia Johnson was Natasha.

- In December 1970, Pacifica Radio station WBAI broadcast a reading of the entire novel (the 1968 Dunnigan translation) read by over 140 celebrities and ordinary people.[52]

- A dramatised full-cast adaptation in 20 parts, edited by Michael Bakewell, was broadcast by the BBC between 30 December 1969 and 12 May 1970, with a cast including David Buck, Kate Binchy and Martin Jarvis.

- A dramatised full-cast adaptation in ten parts was written by Marcy Kahan and Mike Walker in 1997 for BBC Radio 4. The production won the 1998 Talkie award for Best Drama and was around 9.5 hours in length. It was directed by Janet Whitaker and featured Simon Russell Beale, Gerard Murphy, Richard Johnson, and others.[53]

- On New Year’s Day 2015, BBC Radio 4[54] broadcast a dramatisation over 10 hours. The dramatisation, by playwright Timberlake Wertenbaker, was directed by Celia de Wolff and starred Paterson Joseph and John Hurt. It was accompanied by a Tweetalong: live tweets throughout the day that offered a playful companion to the book and included plot summaries and entertaining commentary. The Twitter feed also shared maps, family trees and battle plans.[55]

See also[edit]

- Leo Tolstoy bibliography

- List of historical novels

- Volkonsky House

- War and Peas

- Mir

References[edit]

- ^ Moser, Charles. 1992. Encyclopedia of Russian Literature. Cambridge University Press, pp. 298–300.

- ^ Thirlwell, Adam «A masterpiece in miniature». The Guardian (London, UK) October 8, 2005

- ^ Briggs, Anthony. 2005. «Introduction» to War and Peace. Penguin Classics.

- ^ a b Pevear, Richard (2008). «Introduction». War and Peace. Trans. Pevear; Volokhonsky, Larissa. New York: Vintage Books. pp. VIII–IX. ISBN 978-1-4000-7998-8.

- ^ a b Knowles, A. V. Leo Tolstoy, Routledge 1997.

- ^ «Introduction?». War and Peace. Wordsworth Editions. 1993. ISBN 978-1-85326-062-9. Retrieved 2009-03-24.

- ^ Hare, Richard (1956). «Tolstoy’s Motives for Writing «War and Peace»«. The Russian Review. 15 (2): 110–121. doi:10.2307/126046. ISSN 0036-0341. JSTOR 126046.

- ^ Thompson, Caleb (2009). «Quietism from the Side of Happiness: Tolstoy, Schopenhauer, War and Peace». Common Knowledge. 15 (3): 395–411. doi:10.1215/0961754X-2009-020.

- ^ a b c Kathryn B. Feuer; Robin Feuer Miller; Donna Tussing Orwin (2008). Tolstoy and the Genesis of War and Peace. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7447-7. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ Emerson, Caryl (1985). «The Tolstoy Connection in Bakhtin». PMLA. 100 (1): 68–80 (68–71). doi:10.2307/462201. JSTOR 462201. S2CID 163631233.

- ^ Hudspith, Sarah. «Ten Things You Need to Know About War And Peace». BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Pearson and Volokhonsky, op. cit.

- ^ Troyat, Henri. Tolstoy, a biography. Doubleday, 1967.

- ^ a b c d Figes, Orlando (November 22, 2007). «Tolstoy’s Real Hero». New York Review of Books. 54 (18): 53–56. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Flaitz, Jeffra (1988). The ideology of English: French perceptions of English as a world language. Walter de Gruyter. p. 3. ISBN 978-3-110-11549-9. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

- ^ a b Inna, Gorbatov (2006). Catherine the Great and the French philosophers of the Enlightenment: Montesquieu, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot and Grim. Academica Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-933-14603-4. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Tolstoy, Leo (1949). War and Peace. Garden City: International Collectors Library.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace. p. 317

- ^ Tolstoy p. 340

- ^ Sukhikh, Igor (2007). «The History of XIX Russian literature». Zvezda. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Opulskaya, L.D. War and Peace: the Epic. L.N. Tolstoy. Works in 12 volumes. War and Peace. Commentaries. Vol. 7. Moscow, Khudozhesstvennaya Literatura. 1974. pp. 363–89

- ^ Zaitsev, V., Pearls and Adamants of Russian Journalism. Russkoye Slovo, 1865, #2.

- ^ Kuzminskaya, T.A., My Life at home and at Yasnaya Polyana. Tula, 1958, 343

- ^ Gusev, N.I. Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. Materials for Biography, 1855–1869. Moscow, 1967. pp. 856–57.

- ^ The Literature Archive, vol. 6, Academy of Science of the USSR, 1961, p. 81

- ^ Literary Archive, p. 94

- ^ Literary Archive, p. 104.

- ^ The Beginnings (Nachala), 1922. #2, p. 219

- ^ Dostoyevsky, F.M., Letters, Vol. III, 1934, p. 206.

- ^ Gusev, p. 858

- ^ Gusev, pp. 863–74

- ^ The Complete I.S. Turgenev, vol. XV, Moscow; Leningrad, 1968, 187–88

- ^ Motylyova, T. Of the worldwide significance of Tolstoy. Moscow. Sovetsky pisatel Publishers, 1957, p. 520.

- ^ Literaturnoye Nasledstsvo, vol. 75, book 1, p. 61

- ^ Literaturnoye Nasledstsvo, vol. 75, book 1, p. 173

- ^ «Introduction to War and Peace» by Richard Pevear in Pevear, Richard and Larissa Volokhonsky, War and Peace, 2008, Vintage Classics.

- ^ Greenwood, Edward Baker (1980). «What is War and Peace?». Tolstoy: The Comprehensive Vision. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 83. ISBN 0-416-74130-4.

- ^ Pavlovskis-Petit, Zoja. Entry: Lev Tolstoi, War and Peace. Classe, Olive (ed.). Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, 2000. London, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, pp. 1404–05.

- ^ Curtis, Charlotte (2007). «War-and-Peace». Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- ^ War and Peace. BBC Two (ended 1973) Archived 2009-08-13 at the Wayback Machine. TV.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-29.

- ^ War & Peace (TV mini-series 1972–74) at IMDb

- ^ La guerre et la paix (TV 2000) at IMDb

- ^ War and Peace (TV mini-series 2007) at IMDb

- ^ Flood, Alison (8 December 2015). «Four-day marathon public reading of War and Peace begins in Russia». The Guardian.

- ^ Danny Cohen (2013-02-18). «BBC One announces adaptation of War and Peace by Andrew Davies». BBC. Retrieved 2014-04-20.

- ^ «War and Peace Filming in Lithuania».

- ^ History – highlights. Sydney Opera House. Retrieved on 2012-01-29.

- ^ Cavendish, Dominic (February 11, 2008). «War and Peace: A triumphant Tolstoy». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008.

- ^ «War and Peace». Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2008-12-20.. Sharedexperience.org.uk

- ^ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (October 17, 2012). «Over the Moon for Comet». The NY Post. New York.

- ^ «La Joven. War & Love».

- ^ «The War and Peace Broadcast: 35th Anniversary». Archived from the original on 2006-02-09. Retrieved 2006-02-09.. Pacificaradioarchives.org

- ^ «Marcy Kahan Radio Plays». War and Peace (Radio Dramatization). Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ «War and Peace — BBC Radio 4». BBC.

- ^ Rhian Roberts (17 December 2014). «Is your New Year resolution finally to read War & Peace?». BBC Blogs.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- English Text

- English translation with commentary by the Maudes at the Internet Archive

- English translation at Gutenberg

- War and Peace, from Marxists.org

- War and Peace, from RevoltLib.com

- War and Peace’, from TheAnarchistLibrary.org

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1863-1869). Illustrated by A. Apsit (1911-1912)

- Searchable version of the gutenberg text in multiple formats SiSU

- War and Peace at the Internet Book List

- A searchable online version of Aylmer Maude’s English translation of War and Peace

- English Audio

War and Peace public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Commentaries

- Homage to War and Peace Searchable map, compiled by Nicholas Jenkins, of places named in Tolstoy’s novel (2008).

- Birth, death, balls and battles by Orlando Figes. This is an edited version of an essay found in the Penguin Classics new translation of War and Peace (2005).

- Summaries

- Chapter Summaries for War and Peace

- SparkNotes Study Guide for War and Peace

- In Current Events

- Radio documentary about 1970 marathon reading of War and Peace on WBAI, from Democracy Now! program, December 6, 2005

- Russian Text Online

- Full text of War and Peace in modern Russian orthography

Front page of War and Peace, first edition, 1869 (Russian) |

|

| Author | Leo Tolstoy |

|---|---|

| Original title | Война и миръ |

| Translator | The first translation of War and Peace into English was by American Nathan Haskell Dole, in 1899 |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian, with some French |

| Genre | Novel (Historical novel) |

| Publisher | The Russian Messenger (serial) |

|

Publication date |

Serialised 1865–1867; book 1869 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 1,225 (first published edition) |

| Followed by | The Decembrists (Abandoned and Unfinished) |

|

Original text |

Война и миръ at Russian Wikisource |

| Translation | War and Peace at Wikisource |

War and Peace (Russian: Война и мир, romanized: Voyna i mir; pre-reform Russian: Война и миръ; [vɐjˈna i ˈmʲir]) is a literary work by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy that mixes fictional narrative with chapters on history and philosophy. It was first published serially, then published in its entirety in 1869. It is regarded as Tolstoy’s finest literary achievement and remains an internationally praised classic of world literature.[1][2][3]

The novel chronicles the French invasion of Russia and the impact of the Napoleonic era on Tsarist society through the stories of five Russian aristocratic families. Portions of an earlier version, titled The Year 1805,[4] were serialized in The Russian Messenger from 1865 to 1867 before the novel was published in its entirety in 1869.[5]

Tolstoy said that the best Russian literature does not conform to standards and hence hesitated to classify War and Peace, saying it is «not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less a historical chronicle». Large sections, especially the later chapters, are philosophical discussions rather than narrative.[6] He regarded Anna Karenina as his first true novel.

Composition history[edit]

Tolstoy’s notes from the ninth draft of War and Peace, 1864.

Tolstoy began writing War and Peace in 1863, the year that he finally married and settled down at his country estate. In September of that year, he wrote to Elizabeth Bers, his sister-in-law, asking if she could find any chronicles, diaries or records that related to the Napoleonic period in Russia. He was dismayed to find that few written records covered the domestic aspects of Russian life at that time, and tried to rectify these omissions in his early drafts of the novel.[7] The first half of the book was written and named «1805». During the writing of the second half, he read widely and acknowledged Schopenhauer as one of his main inspirations. Tolstoy wrote in a letter to Afanasy Fet that what he had written in War and Peace is also said by Schopenhauer in The World as Will and Representation. However, Tolstoy approaches «it from the other side.»[8]

The first draft of the novel was completed in 1863. In 1865, the periodical Russkiy Vestnik (The Russian Messenger) published the first part of this draft under the title 1805 and published more the following year. Tolstoy was dissatisfied with this version, although he allowed several parts of it to be published with a different ending in 1867. He heavily rewrote the entire novel between 1866 and 1869.[5][9] Tolstoy’s wife, Sophia Tolstaya, copied as many as seven separate complete manuscripts before Tolstoy considered it ready for publication.[9] The version that was published in Russkiy Vestnik had a very different ending from the version eventually published under the title War and Peace in 1869. Russians who had read the serialized version were eager to buy the complete novel, and it sold out almost immediately. The novel was immediately translated after publication into many other languages.[citation needed]

It is unknown why Tolstoy changed the name to War and Peace. He may have borrowed the title from the 1861 work of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: La Guerre et la Paix («War and Peace» in French).[4] The title may also be a reference to the Roman Emperor Titus, (reigned 79-81 AD) described as being a master of «war and peace» in The Twelve Caesars, written by Suetonius in 119. The completed novel was then called Voyna i mir (Война и мир in new-style orthography; in English War and Peace).[citation needed]

The 1805 manuscript was re-edited and annotated in Russia in 1893 and has been since translated into English, German, French, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Albanian, Korean, and Czech.

Tolstoy was instrumental in bringing a new kind of consciousness to the novel. His narrative structure is noted not only for its god’s eye point of view over and within events, but also in the way it swiftly and seamlessly portrayed an individual character’s view point. His use of visual detail is often comparable to cinema, using literary techniques that resemble panning, wide shots and close-ups. These devices, while not exclusive to Tolstoy, are part of the new style of the novel that arose in the mid-19th century and of which Tolstoy proved himself a master.[10]

The standard Russian text of War and Peace is divided into four books (comprising fifteen parts) and an epilogue in two parts. Roughly the first half is concerned strictly with the fictional characters, whereas the latter parts, as well as the second part of the epilogue, increasingly consist of essays about the nature of war, power, history, and historiography. Tolstoy interspersed these essays into the story in a way that defies previous fictional convention. Certain abridged versions remove these essays entirely, while others, published even during Tolstoy’s life, simply moved these essays into an appendix.[11]

Realism[edit]

The novel is set 60 years before Tolstoy’s day, but he had spoken with people who lived through the 1812 French invasion of Russia. He read all the standard histories available in Russian and French about the Napoleonic Wars and had read letters, journals, autobiographies and biographies of Napoleon and other key players of that era. There are approximately 160 real persons named or referred to in War and Peace.[12]

He worked from primary source materials (interviews and other documents), as well as from history books, philosophy texts and other historical novels.[9] Tolstoy also used a great deal of his own experience in the Crimean War to bring vivid detail and first-hand accounts of how the Imperial Russian Army was structured.[13]

Tolstoy was critical of standard history, especially military history, in War and Peace. He explains at the start of the novel’s third volume his own views on how history ought to be written.

Language[edit]

Cover of War and Peace, Italian translation, 1899.

Although the book is mainly in Russian, significant portions of dialogue are in French. It has been suggested[14] that the use of French is a deliberate literary device, to portray artifice while Russian emerges as a language of sincerity, honesty, and seriousness. It could, however, also simply represent another element of the realistic style in which the book is written, since French was the common language of the Russian aristocracy, and more generally the aristocracies of continental Europe, at the time.[15] In fact, the Russian nobility often knew only enough Russian to command their servants; Tolstoy illustrates this by showing that Julie Karagina, a character in the novel, is so unfamiliar with her country’s native language that she has to take Russian lessons.

The use of French diminishes as the book progresses. It is suggested that this is to demonstrate Russia freeing itself from foreign cultural domination,[14] and to show that a once-friendly nation has turned into an enemy. By midway through the book, several of the Russian aristocracy are eager to find Russian tutors for themselves.

Background and historical context[edit]

The novel spans the period from 1805 to 1820. The era of Catherine the Great was still fresh in the minds of older people. Catherine had made French the language of her royal court.[16] For the next 100 years, it became a social requirement for the Russian nobility to speak French and understand French culture.[16]

The historical context of the novel begins with the execution of Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien in 1805, while Russia is ruled by Alexander I during the Napoleonic Wars. Key historical events woven into the novel include the Ulm Campaign, the Battle of Austerlitz, the Treaties of Tilsit, and the Congress of Erfurt. Tolstoy also references the Great Comet of 1811 just before the French invasion of Russia.[17]: 1, 6, 79, 83, 167, 235, 240, 246, 363–364

Tolstoy then uses the Battle of Ostrovno and the Battle of Shevardino Redoubt in his novel, before the occupation of Moscow and the subsequent fire. The novel continues with the Battle of Tarutino, the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, the Battle of Vyazma, and the Battle of Krasnoi. The final battle cited is the Battle of Berezina, after which the characters move on with rebuilding Moscow and their lives.[17]: 392–396, 449–481, 523, 586–591, 601, 613, 635, 638, 655, 640

Principal characters[edit]

War and Peace simple family tree.

War and Peace detailed family tree.

The novel tells the story of five families—the Bezukhovs, the Bolkonskys, the Rostovs, the Kuragins, and the Drubetskoys.

The main characters are:

- The Bezukhovs

- Count Kirill Vladimirovich Bezukhov: the father of Pierre

- Count Pyotr Kirillovich («Pierre») Bezukhov: The central character and often a voice for Tolstoy’s own beliefs or struggles. Pierre is the socially awkward illegitimate son of Count Kirill Vladimirovich Bezukhov, who has fathered dozens of illegitimate sons. Educated abroad, Pierre returns to Russia as a misfit. His unexpected inheritance of a large fortune makes him socially desirable.

- The Bolkonskys

- Prince Nikolai Andreich Bolkonsky: The father of Andrei and Maria, the eccentric prince possesses a gruff exterior and displays great insensitivity to the emotional needs of his children. Nevertheless, his harshness often belies hidden depth of feeling.

- Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky: A strong but skeptical, thoughtful and philosophical aide-de-camp in the Napoleonic Wars.

- Princess Elisabeta «Lisa» Karlovna Bolkonskaya (also Lise) – née Meinena. Wife of Andrei. Also called «little princess».

- Princess Maria Nikolayevna Bolkonskaya: Sister of Prince Andrei, Princess Maria is a pious woman whose father attempted to give her a good education. The caring, nurturing nature of her large eyes in her otherwise plain face is frequently mentioned. Tolstoy often notes that Princess Maria cannot claim a radiant beauty (like many other female characters of the novel) but she is a person of very high moral values and of high intelligence.

- The Rostovs

- Count Ilya Andreyevich Rostov: The pater-familias of the Rostov family; hopeless with finances, generous to a fault. As a result, the Rostovs never have enough cash, despite having many estates.

- Countess Natalya Rostova: The wife of Count Ilya Rostov, she is frustrated by her husband’s mishandling of their finances, but is determined that her children succeed anyway

- Countess Natalya Ilyinichna «Natasha» Rostova: A central character, introduced as «not pretty but full of life», romantic, impulsive and highly strung. She is an accomplished singer and dancer.

- Count Nikolai Ilyich «Nikolenka» Rostov: A hussar, the beloved eldest son of the Rostov family.

- Sofia Alexandrovna «Sonya» Rostova: Orphaned cousin of Vera, Nikolai, Natasha, and Petya Rostov and is in love with Nikolai.

- Countess Vera Ilyinichna Rostova: Eldest of the Rostov children, she marries the German career soldier, Berg.

- Pyotr Ilyich «Petya» Rostov: Youngest of the Rostov children.

- The Kuragins

- Prince Vasily Sergeyevich Kuragin: A ruthless man who is determined to marry his children into wealth at any cost.

- Princess Elena Vasilyevna «Hélène» Kuragina: A beautiful and sexually alluring woman who has many affairs, including (it is rumoured) with her brother Anatole.

- Prince Anatole Vasilyevich Kuragin: Hélène’s brother, a handsome and amoral pleasure seeker who is secretly married yet tries to elope with Natasha Rostova.

- Prince Ippolit Vasilyevich (Hippolyte) Kuragin: The younger brother of Anatole and perhaps most dim-witted of the three Kuragin children.

- The Drubetskoys

- Prince Boris Drubetskoy: A poor but aristocratic young man driven by ambition, even at the expense of his friends and benefactors, who marries Julie Karagina for money and is rumored to have had an affair with Hélène Bezukhova.

- Princess Anna Mihalovna Drubetskaya: The impoverished mother of Boris, whom she wishes to push up the career ladder.

- Other prominent characters

- Fyodor Ivanovich Dolokhov: A cold, almost psychopathic officer, he ruins Nikolai Rostov by luring him into an outrageous gambling debt after unsuccessfully proposing to Sonya Rostova. He is also rumored to have had an affair with Hélène Bezukhova and he provides for his poor mother and hunchbacked sister.

- Adolf Karlovich Berg: A young German officer, who desires to be just like everyone else and marries the young Vera Rostova.

- Anna Pavlovna Scherer: Also known as Annette, she is the hostess of the salon that is the site of much of the novel’s action in Petersburg and schemes with Prince Vasily Kuragin.

- Maria Dmitryevna Akhrosimova: An older Moscow society lady, good-humored but brutally honest.

- Amalia Evgenyevna Bourienne: A Frenchwoman who lives with the Bolkonskys, primarily as Princess Maria’s companion and later at Maria’s expense.

- Vasily Dmitrich Denisov: Nikolai Rostov’s friend and brother officer, who unsuccessfully proposes to Natasha.

- Platon Karataev: The archetypal good Russian peasant, whom Pierre meets in the prisoner-of-war camp.

- Osip Bazdeyev: a Freemason who convinces Pierre to join his mysterious group.

- Bilibin: A diplomat with a reputation for cleverness, an acquaintance of Prince Andrei Bolkonsky.

In addition, several real-life historical characters (such as Napoleon and Prince Mikhail Kutuzov) play a prominent part in the book. Many of Tolstoy’s characters were based on real people. His grandparents and their friends were the models for many of the main characters; his great-grandparents would have been of the generation of Prince Vassily or Count Ilya Rostov.

Plot summary[edit]

Book One[edit]