First edition, published in 1844

Germany. A Winter’s Tale (German: Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen) is a satirical epic poem by the German writer Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), describing the thoughts of a journey from Paris to Hamburg the author made in winter 1843. The title refers to Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale, similar to his poem Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum («Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night’s Dream»), written 1841–46.

This poem was immediately censored in most of Germany, but ironically it became one of the reasons for Heine’s growing fame.[1]

Original publication[edit]

From the onset of the (Metternich) Restoration in Germany, Heine was no longer secure from the censorship, and in 1831 he finally migrated to France as an exile. In 1835 a decree of the German Federal Convention banned his writings together with the publications of the Young Germany literary group.

At the end of 1843 Heine went back to Germany for a few weeks to visit his mother and his publisher Julius Campe in Hamburg. On the return journey the first draft of Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen took shape. The verse epic appeared in 1844 published by Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg. According to the censorship regulations of the 1819 Carlsbad Decrees, manuscripts of more than twenty folios did not fall under the scrutiny of the censor. Therefore, Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen was published together with other poems in a volume called ‘New Poems’. However, on 4 October 1844 the book was banned and the stock confiscated in Prussia. On 12 December 1844, King Frederick William IV issued a warrant of arrest against Heine. In the period following the work was repeatedly banned by the censorship authorities. In other parts of Germany it was certainly issued in the form of a separate publication, also published by Hoffmann and Campe, but Heine had to shorten and rewrite it.

Ironically, censorship of Heine’s works, particularly of the Winter Tale, became a major reason for Heine’s raising fame.[1]

Contents[edit]

The opening of the poem is the first journey of Heinrich Heine to Germany since his emigration to France in 1831. However it is to be understood that this is an imaginary journey, not the actual journey which Heine made but a literary tour through various provinces of Germany for the purposes of his commentary. The ‘I’ of the narrative is therefore the instrument of the poet’s creative imagination.

Wintermärchen and Winterreise

Heinrich Heine was a master of the natural style of lyrics on the theme of love, like those in the ‘Lyrisches Intermezzo’ of 1822-1823 in Das Buch der Lieder (1827) which were set by Robert Schumann in his Dichterliebe. A few of his poems had been set by Franz Schubert, not least for the great posthumously-collected series of songs known as the Schwanengesang. In such works Heine assumed the manner of Wilhelm Müller, whose son Professor Max Müller later emphasized[2] the fundamentally musical nature of these poems and the absolute congruity of Schubert’s settings of them, which are fully composed duos for voice and piano rather than merely ‘accompaniments’ to tunes. Yet Heine’s work addressed political preoccupations with a barbed and contemporary voice, whereas Müller’s melancholy lyricism and nature-scenery explored more private (if equally universal) human experience. Schubert’s Heine settings hardly portray the poet-philosopher’s full identity.

Schubert was dead by 1828: Heine’s choice of the winter journey theme certainly alludes to the Winterreise, Müller’s cycle of poems about lost love, which in Schubert’s song-cycle of the same name became an immortal work embodying some more final and tragic statement about the human condition. Winterreise is about the exile of the human heart, and its bitter and gloomy self-reconciliation. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen transfers the theme to the international European political scene, his exile as a writer from his own homeland (where his heart is), and his Heimatssehnsucht or longing for the homeland. Thus Heine casts his secret and ‘illegal thoughts’, so that the darts of his satire and humour fly out from the tragic vortex of his own exile. The fact that Heine’s poetry was itself so closely identified with Schubert was part of his armoury of ‘fire and weapons’ mentioned in the closing stanzas: he transformed Müller’s lament into a lament for Germany.

In Section III, full of euphoria he sets foot again on German soil, with only ‘shirts, trousers and pocket handkerchiefs’ in his luggage, but in his head ‘a twittering birds’-nest/ of books liable to be confiscated’. In Aachen Heine first comes in contact again with the Prussian military:

These people are still the same wooden types,

Spout pedantic commonplaces —

All motions right-angled — and priggishness

Is frozen upon their faces.

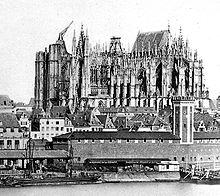

Unfinished Cologne Cathedral in 1856, the year of Heine’s death.

In Section IV on the winter-journey to Cologne he mocks the anachronistic German society, that more readily with archaic skills builds the Cologne Cathedral, unfinished since the Middle Ages, than addressing itself to the Present Age. That the anachronistic building works came to be discontinued in the course of the Reformation indicated for the poet a positive advance: the overcoming of traditional ways of thought and the end of spiritual juvenility or adolescence.

In Section V he comes to the Rhine, as ‘the German Rhine’ and ‘Father Rhine’, icon and memorial of German identity. The River-god however shows himself as a sorrowful old man, disgusted with the babble about Germanic identity. He does not long to go back among the French who, according to Heine, now drink beer and read ‘Fichte’ and Kant.

Section VI introduces the ‘Liktor’, the poet’s demon and ghostly doppelganger, always present, who follows him about carrying a hatchet under his cloak, waiting for a sign to execute the poet’s judicial sentences. The stanzas express Heine’s conviction that an idea once thought can never be lost. He confronts the shadowy figure, and is told:

In Rome an ax was carried before

A consul, may I remind you.

You too have your lictor, but nowadays

The ax is carried behind you.

I am your lictor: in the rear

You always hear the clink of

The headsman’s ax that follows you.

I am the deed you think of.

In Section VII the Execution begins in dream. Followed by his ‘silent attendant’ the poet wanders through Cologne. He marks the doorposts with his heart’s blood, and this gives the Liktor the signal for a death-sentence. At last he reaches the Cathedral with the Three Kings Shrine, and “smashes up the poor skeletons of Superstition.’

In Section VIII he travels further on to Hagen and Mülheim, places which bring to mind his former enthusiasm for Napoleon Bonaparte. His transformation of Europe had called awake in Heine the hope for universal freedom. However: the Emperor is dead. Heine had been an eye-witness in Paris of his burial in 1840 at Les Invalides.

Section IX brings culinary reminiscences of ‘homely Sauerkraut’ seasoned with satirical pointedness: Section X, Greetings to Westphalia.

In Section XI he travels through the Teutoburg Forest and fantasizes about it, what might have happened, if Hermann of the Cherusci had not vanquished the Romans: Roman culture would have permeated the spiritual life of Germany, and in place of the ‘Three Dozen Fathers of the Provinces’ should have been now at least one proper Nero. The Section is – in disguise – also an attack on the Culture-politics of the ‘Romantic on the Throne,’ Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; then pretty well all the significant individuals in this outfit (for example Raumer, Hengstenberg, Birch-Pfeiffer, Schelling, Maßmann, Cornelius) lived in Berlin.

Section XII contains the poet’s address on the theme: ‘Howling with the wolves,’ as the carriage breaks down in the forest at night, and he responds as the denizens of the forest serenade him. This Heine offers as a metaphoric statement of the critical distance occupied by himself as polemic or satirical poet, and of the sheepskin-costume appropriate for much of what was surrounding him.

I am no sheep, I am no dog,

No Councillor, and no shellfish –

I have remained a wolf, my heart

And all my fangs are wolfish.

Section XIII takes the traveller to Paderborn. In the morning mist a crucifix appears. The ‘poor jewish cousin’ had even less good fortune than Heine, since the kindly Censor had at least held back from having him crucified – until now, at any rate …

In Section XIV and Section XV the poet betakes himself in a dream to another memorable place: he visits Friedrich Barbarossa in Kyffhäuser. Not surprisingly the mythic German Emperor presents himself as a man become imbecile through senility, who is above all proud of the fact that his banner has not yet been eaten by moths. Germany in internal need? Pressing need of business for an available Emperor? Wake up, old man, and take your beard off the table! What does the most ancient hero mean by it?

He who comes not today, tomorrow surely comes,

But slowly doth the oak awaken,

And ‘he who goes softly goes well*’, so runs

The proverb in the Roman kingdom.

(*chi va piano va sano, Italian)

Section XVI brings the Emperor to the most recent state of affairs: between the Middle Ages and Modern Times, between Barbarossa and today stands and functions the guillotine. Emperors have worn out their usefulness, and seen in that light Monarchs are also superfluous. Stay up the mountain, Old Man! Best of all, the nobility, along with that ‘gartered knighthood of gothic madness and modern lie,’ should stay there too with you in Kyffhäuser (Section XVII). Sword or noose would do equally good service for the disposal of these superfluous toadies.

Dealings with the police remain unpleasant in Minden, followed by the obligatory nightmare and dream of revenge (Section XVIII).

In Section XIX he visits the house where his grandfather was born in Bückeburg:

At Bückeburg I went up into the town,

To view the old fortress, the Stammburg,

The place where my grandfather was born;

My grandmother came from Hamburg.

From there he went on to a meeting with King Ernest Augustus of Hanover in that place, who, «accustomed to life in Great Britain» detains him for a deadly length of time. The section refers above all to the violation of the constitution by Ernst August in the year 1837, who was opposed by the seven Göttingen professors.

Finally, in Section XX, he is at the limit of his journey: In Hamburg he goes in to visit his mother. She, equally, is in control of her responsibilities:

- 1. Are you hungry?

- 2. Have you got a wife?

- 3. Where would you rather live, here with me or in France?

- 4. Do you always talk about politics?

Section XXI and XXII shows the poet in Hamburg in search of people he knows, and memories, and in Section XXIII he sings the praises of the publisher Campe. Section XXIV describes a meeting with the genius loci of Hamburg, Hammonia. A solemn promise of the greatest secrecy must be made in Old Testament fashion, in which he places his hand under the thigh of the Goddess (she blushes slightly – having been drinking rum!). Then the Goddess promises to show her visitor the future Germany. Universal expectation. Then the Censor makes a cut at the critical place. Disappointment. (Section XXV and XXVI)

With Section XXVII the Winter’s Tale ends:

The Youth soon buds, who understands

The poet’s pride and grandeur

And in his heart he warms himself,

At his soul’s sunny splendour.

In the final stanzas Heine places himself in the tradition of Aristophanes and Dante and speaks directly to the King of Prussia:

Then do not harm your living bards,

For they have fire and arms

More frightful than Jove’s thunderbolt:

Through them the Poet forms.

With a warning to the King, of eternal damnation, the epic closes.

A critic for love of the Fatherland[edit]

Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen shows Heine’s world of images and his folk-song-like poetic diction in a compact gathering, with cutting, ironic criticisms of the circumstances in his homeland. Heine puts his social vision into contrast with the grim ‘November-picture’ of the reactionary homeland which presented itself to his eyes:

A new song, a better song,

O friends, I speak to thee!

Here upon Earth we shall full soon

A heavenly realm decree.

Joyful we on earth shall be

And we shall starve no more;

The rotten belly shall not feed

On the fruits of industry.

Above all Heine criticized German militarism and reactionary chauvinism (i.e. nationalism), especially in contrast to the French, whose revolution he understood as a breaking-off into freedom. He admired Napoleon (uncritically) as the man who achieved the Revolution and made freedom a reality. He did not see himself as an enemy of Germany, but rather as a critic out of love for the Fatherland:

Plant the black, red, gold banner at the summit of the German idea, make it the standard of free mankind, and I will shed my dear heart’s blood for it. Rest assured, I love the Fatherland just as much as you do.

(from the Foreword).

The ‘Winter’s Tale’ today[edit]

Heine’s verse-epic was much debated in Germany right down to our own times. Above all in the century to which it belonged, the work was labelled as the ‘shameful writing’ of a homeless or country-less man, a ‘betrayer of the Fatherland’, a detractor and a slanderer. This way of looking at Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen was carried, especially in the period of Nazism, into a ridiculous antisemitic caricature. Immediately after World War II a cheap edition of the poem with Heine’s Foreword and an introduction by Wolfgang Goetz was published by the Wedding-Verlag in Berlin in 1946.

Modern times see in Heine’s work – rather, the basis of a wider concern with nationalism and narrow concepts of German identity, against the backdrop of European integration – a weighty political poem in the German language: sovereign in its insight and inventive wit, stark in its images, masterly in its use of language. Heine’s figure-creations (like, for example, the ‘Liktor’) are skilful, and memorably portrayed.

A great deal of the attraction which the verse-epic holds today is grounded in this, that its message is not one-dimensional, but rather brings into expression the many-sided contradictions or contrasts in Heine’s thought. The poet shows himself as a man who loves his homeland and yet can only be a guest and visitor to it. In the same way that Antaeus needed contact with the Earth, so Heine drew his skill and the fullness of his thought only through intellectual contact with the homeland.

This exemplified the visible breach which the French July Revolution of 1830 signifies for intellectual Germany: the fresh breeze of freedom suffocated in the reactionary exertions of the Metternich Restoration, the soon-downtrodden ‘Spring’ of freedom yielded to a new winter of censorship, repression, persecution and exile; the dream of a free and democratic Germany was for a whole century dismissed from the realm of possibility.

Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen is a high-point of political poetry of the Vormärz period before the March Revolution of 1848, and in Germany is part of the official educational curriculum. The work taken for years and decades as the anti-German pamphlet of the ‘voluntary Frenchman’ Heine, today is for many people the most moving poem ever written by an emigrant.

Recently, reference to this poem has been made by director Sönke Wortmann for his football documentary on the German male national team during the 2006 FIFA world cup. The movie is entitled «Deutschland. Ein Sommermärchen». The world cup in 2006 is often mentioned as a point in time which had a significant positive impact on modern Germany, reflecting a changed understanding of national identity which has been evolving continuously over the 50 years prior to the event.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Amey, L. J. (1997-01-01). Censorship: Gabler, Mel, and Norma Gabler-President’s Commission on Obscenity and Pornography. Salem Press. p. 350. ISBN 9780893564469.

Ironically, Heine became famous because of censorship, particularly after he wrote a political cycle of poems entitled Germany. A Winter’s Tale in 1 844 that was immediately banned throughout the confederation

- ^ Franz Schubert, Sammlung der Lieder kritisch revidirt von Max Friedlaender, Vol 1., Preface by F. Max Müller (Edition Peters, Leipzig)

Sources[edit]

Translation into English

- Deutschland: A Not So Sentimental Journey by Heinrich Heine. Translated (into English) with an Introduction and Notes by T. J. Reed (Angel Books, London 1986). ISBN 0-946162-58-1

- Germany. A Winter’s Tale in: Hal Draper: The Complete Poems of Heinrich Heine. A Modern English Version (Suhrkamp/Insel Publishers Boston Inc. 1982). ISBN 3-518-03062-0

German Editions

- Heinrich Heine. Historico-critical complete edition of the Works. Edited by Manfred Windfuhr. Vol. 4: Atta Troll. Ein Sommernachtstraum / Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Revised by Winfried Woesler. (Hoffmann und Campe, Hamburg 1985).

- H. H. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Edited by Joseph Kiermeier-Debre. (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1997.) (Bibliothek der Erstausgaben.) ISBN 3-423-02632-4

- H. H. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Edited by Werner Bellmann. Revised Edition. (Reclam, Stuttgart 2001.) ISBN 3-15-002253-3

- H. H. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Edited by Werner Bellmann. Illustrations by Hans Traxler.(Reclam, Stuttgart 2005.) ISBN 3-15-010589-7 (Paperback: Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-020236-4)

Research literature, Commentaries (German)

- Werner Bellmann: Heinrich Heine. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Illustrations and Documents. Revised Edition. (Reclam, Stuttgart 2005.) ISBN 3-15-008150-5

- Karlheinz Fingerhut: Heinrich Heine: Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. (Diesterweg, Frankfurt am Main 1992). (Grundlagen und Gedanken zum Verständnis erzählender Literatur) ISBN 3-425-06167-4

- Jost Hermand: Heines Wintermärchen – On the subject of the ‘deutsche Misere’. In: Diskussion Deutsch 8 (1977) Heft 35. p 234-249.

- Joseph A. Kruse: Ein neues Lied vom Glück? (A new song of happiness?) Heinrich Heines Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. In: J. A. K.: Heine-Zeit. (Stuttgart/München 1997) p 238-255.

- Renate Stauf: Heinrich Heine. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. In: Renate Stauf/Cord Berghahn (Editors): Weltliteratur II. Eine Braunschweiger Vorlesung. (Bielefeld 2005). p 269-284.

- Jürgen Walter: Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. In: Heinrich Heine. Epoche — Werk — Wirkung. Edited by Jürgen Brummack. (Beck, München 1980). p 238-254.

External links[edit]

- German text at German Wikisource [1]

- German text at Project Gutenberg [2]

First edition, published in 1844

Germany. A Winter’s Tale (German: Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen) is a satirical epic poem by the German writer Heinrich Heine (1797–1856), describing the thoughts of a journey from Paris to Hamburg the author made in winter 1843. The title refers to Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale, similar to his poem Atta Troll: Ein Sommernachtstraum («Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night’s Dream»), written 1841–46.

This poem was immediately censored in most of Germany, but ironically it became one of the reasons for Heine’s growing fame.[1]

Original publication[edit]

From the onset of the (Metternich) Restoration in Germany, Heine was no longer secure from the censorship, and in 1831 he finally migrated to France as an exile. In 1835 a decree of the German Federal Convention banned his writings together with the publications of the Young Germany literary group.

At the end of 1843 Heine went back to Germany for a few weeks to visit his mother and his publisher Julius Campe in Hamburg. On the return journey the first draft of Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen took shape. The verse epic appeared in 1844 published by Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg. According to the censorship regulations of the 1819 Carlsbad Decrees, manuscripts of more than twenty folios did not fall under the scrutiny of the censor. Therefore, Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen was published together with other poems in a volume called ‘New Poems’. However, on 4 October 1844 the book was banned and the stock confiscated in Prussia. On 12 December 1844, King Frederick William IV issued a warrant of arrest against Heine. In the period following the work was repeatedly banned by the censorship authorities. In other parts of Germany it was certainly issued in the form of a separate publication, also published by Hoffmann and Campe, but Heine had to shorten and rewrite it.

Ironically, censorship of Heine’s works, particularly of the Winter Tale, became a major reason for Heine’s raising fame.[1]

Contents[edit]

The opening of the poem is the first journey of Heinrich Heine to Germany since his emigration to France in 1831. However it is to be understood that this is an imaginary journey, not the actual journey which Heine made but a literary tour through various provinces of Germany for the purposes of his commentary. The ‘I’ of the narrative is therefore the instrument of the poet’s creative imagination.

Wintermärchen and Winterreise

Heinrich Heine was a master of the natural style of lyrics on the theme of love, like those in the ‘Lyrisches Intermezzo’ of 1822-1823 in Das Buch der Lieder (1827) which were set by Robert Schumann in his Dichterliebe. A few of his poems had been set by Franz Schubert, not least for the great posthumously-collected series of songs known as the Schwanengesang. In such works Heine assumed the manner of Wilhelm Müller, whose son Professor Max Müller later emphasized[2] the fundamentally musical nature of these poems and the absolute congruity of Schubert’s settings of them, which are fully composed duos for voice and piano rather than merely ‘accompaniments’ to tunes. Yet Heine’s work addressed political preoccupations with a barbed and contemporary voice, whereas Müller’s melancholy lyricism and nature-scenery explored more private (if equally universal) human experience. Schubert’s Heine settings hardly portray the poet-philosopher’s full identity.

Schubert was dead by 1828: Heine’s choice of the winter journey theme certainly alludes to the Winterreise, Müller’s cycle of poems about lost love, which in Schubert’s song-cycle of the same name became an immortal work embodying some more final and tragic statement about the human condition. Winterreise is about the exile of the human heart, and its bitter and gloomy self-reconciliation. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen transfers the theme to the international European political scene, his exile as a writer from his own homeland (where his heart is), and his Heimatssehnsucht or longing for the homeland. Thus Heine casts his secret and ‘illegal thoughts’, so that the darts of his satire and humour fly out from the tragic vortex of his own exile. The fact that Heine’s poetry was itself so closely identified with Schubert was part of his armoury of ‘fire and weapons’ mentioned in the closing stanzas: he transformed Müller’s lament into a lament for Germany.

In Section III, full of euphoria he sets foot again on German soil, with only ‘shirts, trousers and pocket handkerchiefs’ in his luggage, but in his head ‘a twittering birds’-nest/ of books liable to be confiscated’. In Aachen Heine first comes in contact again with the Prussian military:

These people are still the same wooden types,

Spout pedantic commonplaces —

All motions right-angled — and priggishness

Is frozen upon their faces.

Unfinished Cologne Cathedral in 1856, the year of Heine’s death.

In Section IV on the winter-journey to Cologne he mocks the anachronistic German society, that more readily with archaic skills builds the Cologne Cathedral, unfinished since the Middle Ages, than addressing itself to the Present Age. That the anachronistic building works came to be discontinued in the course of the Reformation indicated for the poet a positive advance: the overcoming of traditional ways of thought and the end of spiritual juvenility or adolescence.

In Section V he comes to the Rhine, as ‘the German Rhine’ and ‘Father Rhine’, icon and memorial of German identity. The River-god however shows himself as a sorrowful old man, disgusted with the babble about Germanic identity. He does not long to go back among the French who, according to Heine, now drink beer and read ‘Fichte’ and Kant.

Section VI introduces the ‘Liktor’, the poet’s demon and ghostly doppelganger, always present, who follows him about carrying a hatchet under his cloak, waiting for a sign to execute the poet’s judicial sentences. The stanzas express Heine’s conviction that an idea once thought can never be lost. He confronts the shadowy figure, and is told:

In Rome an ax was carried before

A consul, may I remind you.

You too have your lictor, but nowadays

The ax is carried behind you.

I am your lictor: in the rear

You always hear the clink of

The headsman’s ax that follows you.

I am the deed you think of.

In Section VII the Execution begins in dream. Followed by his ‘silent attendant’ the poet wanders through Cologne. He marks the doorposts with his heart’s blood, and this gives the Liktor the signal for a death-sentence. At last he reaches the Cathedral with the Three Kings Shrine, and “smashes up the poor skeletons of Superstition.’

In Section VIII he travels further on to Hagen and Mülheim, places which bring to mind his former enthusiasm for Napoleon Bonaparte. His transformation of Europe had called awake in Heine the hope for universal freedom. However: the Emperor is dead. Heine had been an eye-witness in Paris of his burial in 1840 at Les Invalides.

Section IX brings culinary reminiscences of ‘homely Sauerkraut’ seasoned with satirical pointedness: Section X, Greetings to Westphalia.

In Section XI he travels through the Teutoburg Forest and fantasizes about it, what might have happened, if Hermann of the Cherusci had not vanquished the Romans: Roman culture would have permeated the spiritual life of Germany, and in place of the ‘Three Dozen Fathers of the Provinces’ should have been now at least one proper Nero. The Section is – in disguise – also an attack on the Culture-politics of the ‘Romantic on the Throne,’ Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; then pretty well all the significant individuals in this outfit (for example Raumer, Hengstenberg, Birch-Pfeiffer, Schelling, Maßmann, Cornelius) lived in Berlin.

Section XII contains the poet’s address on the theme: ‘Howling with the wolves,’ as the carriage breaks down in the forest at night, and he responds as the denizens of the forest serenade him. This Heine offers as a metaphoric statement of the critical distance occupied by himself as polemic or satirical poet, and of the sheepskin-costume appropriate for much of what was surrounding him.

I am no sheep, I am no dog,

No Councillor, and no shellfish –

I have remained a wolf, my heart

And all my fangs are wolfish.

Section XIII takes the traveller to Paderborn. In the morning mist a crucifix appears. The ‘poor jewish cousin’ had even less good fortune than Heine, since the kindly Censor had at least held back from having him crucified – until now, at any rate …

In Section XIV and Section XV the poet betakes himself in a dream to another memorable place: he visits Friedrich Barbarossa in Kyffhäuser. Not surprisingly the mythic German Emperor presents himself as a man become imbecile through senility, who is above all proud of the fact that his banner has not yet been eaten by moths. Germany in internal need? Pressing need of business for an available Emperor? Wake up, old man, and take your beard off the table! What does the most ancient hero mean by it?

He who comes not today, tomorrow surely comes,

But slowly doth the oak awaken,

And ‘he who goes softly goes well*’, so runs

The proverb in the Roman kingdom.

(*chi va piano va sano, Italian)

Section XVI brings the Emperor to the most recent state of affairs: between the Middle Ages and Modern Times, between Barbarossa and today stands and functions the guillotine. Emperors have worn out their usefulness, and seen in that light Monarchs are also superfluous. Stay up the mountain, Old Man! Best of all, the nobility, along with that ‘gartered knighthood of gothic madness and modern lie,’ should stay there too with you in Kyffhäuser (Section XVII). Sword or noose would do equally good service for the disposal of these superfluous toadies.

Dealings with the police remain unpleasant in Minden, followed by the obligatory nightmare and dream of revenge (Section XVIII).

In Section XIX he visits the house where his grandfather was born in Bückeburg:

At Bückeburg I went up into the town,

To view the old fortress, the Stammburg,

The place where my grandfather was born;

My grandmother came from Hamburg.

From there he went on to a meeting with King Ernest Augustus of Hanover in that place, who, «accustomed to life in Great Britain» detains him for a deadly length of time. The section refers above all to the violation of the constitution by Ernst August in the year 1837, who was opposed by the seven Göttingen professors.

Finally, in Section XX, he is at the limit of his journey: In Hamburg he goes in to visit his mother. She, equally, is in control of her responsibilities:

- 1. Are you hungry?

- 2. Have you got a wife?

- 3. Where would you rather live, here with me or in France?

- 4. Do you always talk about politics?

Section XXI and XXII shows the poet in Hamburg in search of people he knows, and memories, and in Section XXIII he sings the praises of the publisher Campe. Section XXIV describes a meeting with the genius loci of Hamburg, Hammonia. A solemn promise of the greatest secrecy must be made in Old Testament fashion, in which he places his hand under the thigh of the Goddess (she blushes slightly – having been drinking rum!). Then the Goddess promises to show her visitor the future Germany. Universal expectation. Then the Censor makes a cut at the critical place. Disappointment. (Section XXV and XXVI)

With Section XXVII the Winter’s Tale ends:

The Youth soon buds, who understands

The poet’s pride and grandeur

And in his heart he warms himself,

At his soul’s sunny splendour.

In the final stanzas Heine places himself in the tradition of Aristophanes and Dante and speaks directly to the King of Prussia:

Then do not harm your living bards,

For they have fire and arms

More frightful than Jove’s thunderbolt:

Through them the Poet forms.

With a warning to the King, of eternal damnation, the epic closes.

A critic for love of the Fatherland[edit]

Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen shows Heine’s world of images and his folk-song-like poetic diction in a compact gathering, with cutting, ironic criticisms of the circumstances in his homeland. Heine puts his social vision into contrast with the grim ‘November-picture’ of the reactionary homeland which presented itself to his eyes:

A new song, a better song,

O friends, I speak to thee!

Here upon Earth we shall full soon

A heavenly realm decree.

Joyful we on earth shall be

And we shall starve no more;

The rotten belly shall not feed

On the fruits of industry.

Above all Heine criticized German militarism and reactionary chauvinism (i.e. nationalism), especially in contrast to the French, whose revolution he understood as a breaking-off into freedom. He admired Napoleon (uncritically) as the man who achieved the Revolution and made freedom a reality. He did not see himself as an enemy of Germany, but rather as a critic out of love for the Fatherland:

Plant the black, red, gold banner at the summit of the German idea, make it the standard of free mankind, and I will shed my dear heart’s blood for it. Rest assured, I love the Fatherland just as much as you do.

(from the Foreword).

The ‘Winter’s Tale’ today[edit]

Heine’s verse-epic was much debated in Germany right down to our own times. Above all in the century to which it belonged, the work was labelled as the ‘shameful writing’ of a homeless or country-less man, a ‘betrayer of the Fatherland’, a detractor and a slanderer. This way of looking at Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen was carried, especially in the period of Nazism, into a ridiculous antisemitic caricature. Immediately after World War II a cheap edition of the poem with Heine’s Foreword and an introduction by Wolfgang Goetz was published by the Wedding-Verlag in Berlin in 1946.

Modern times see in Heine’s work – rather, the basis of a wider concern with nationalism and narrow concepts of German identity, against the backdrop of European integration – a weighty political poem in the German language: sovereign in its insight and inventive wit, stark in its images, masterly in its use of language. Heine’s figure-creations (like, for example, the ‘Liktor’) are skilful, and memorably portrayed.

A great deal of the attraction which the verse-epic holds today is grounded in this, that its message is not one-dimensional, but rather brings into expression the many-sided contradictions or contrasts in Heine’s thought. The poet shows himself as a man who loves his homeland and yet can only be a guest and visitor to it. In the same way that Antaeus needed contact with the Earth, so Heine drew his skill and the fullness of his thought only through intellectual contact with the homeland.

This exemplified the visible breach which the French July Revolution of 1830 signifies for intellectual Germany: the fresh breeze of freedom suffocated in the reactionary exertions of the Metternich Restoration, the soon-downtrodden ‘Spring’ of freedom yielded to a new winter of censorship, repression, persecution and exile; the dream of a free and democratic Germany was for a whole century dismissed from the realm of possibility.

Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen is a high-point of political poetry of the Vormärz period before the March Revolution of 1848, and in Germany is part of the official educational curriculum. The work taken for years and decades as the anti-German pamphlet of the ‘voluntary Frenchman’ Heine, today is for many people the most moving poem ever written by an emigrant.

Recently, reference to this poem has been made by director Sönke Wortmann for his football documentary on the German male national team during the 2006 FIFA world cup. The movie is entitled «Deutschland. Ein Sommermärchen». The world cup in 2006 is often mentioned as a point in time which had a significant positive impact on modern Germany, reflecting a changed understanding of national identity which has been evolving continuously over the 50 years prior to the event.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Amey, L. J. (1997-01-01). Censorship: Gabler, Mel, and Norma Gabler-President’s Commission on Obscenity and Pornography. Salem Press. p. 350. ISBN 9780893564469.

Ironically, Heine became famous because of censorship, particularly after he wrote a political cycle of poems entitled Germany. A Winter’s Tale in 1 844 that was immediately banned throughout the confederation

- ^ Franz Schubert, Sammlung der Lieder kritisch revidirt von Max Friedlaender, Vol 1., Preface by F. Max Müller (Edition Peters, Leipzig)

Sources[edit]

Translation into English

- Deutschland: A Not So Sentimental Journey by Heinrich Heine. Translated (into English) with an Introduction and Notes by T. J. Reed (Angel Books, London 1986). ISBN 0-946162-58-1

- Germany. A Winter’s Tale in: Hal Draper: The Complete Poems of Heinrich Heine. A Modern English Version (Suhrkamp/Insel Publishers Boston Inc. 1982). ISBN 3-518-03062-0

German Editions

- Heinrich Heine. Historico-critical complete edition of the Works. Edited by Manfred Windfuhr. Vol. 4: Atta Troll. Ein Sommernachtstraum / Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Revised by Winfried Woesler. (Hoffmann und Campe, Hamburg 1985).

- H. H. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Edited by Joseph Kiermeier-Debre. (Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1997.) (Bibliothek der Erstausgaben.) ISBN 3-423-02632-4

- H. H. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Edited by Werner Bellmann. Revised Edition. (Reclam, Stuttgart 2001.) ISBN 3-15-002253-3

- H. H. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Edited by Werner Bellmann. Illustrations by Hans Traxler.(Reclam, Stuttgart 2005.) ISBN 3-15-010589-7 (Paperback: Reclam, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-15-020236-4)

Research literature, Commentaries (German)

- Werner Bellmann: Heinrich Heine. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. Illustrations and Documents. Revised Edition. (Reclam, Stuttgart 2005.) ISBN 3-15-008150-5

- Karlheinz Fingerhut: Heinrich Heine: Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. (Diesterweg, Frankfurt am Main 1992). (Grundlagen und Gedanken zum Verständnis erzählender Literatur) ISBN 3-425-06167-4

- Jost Hermand: Heines Wintermärchen – On the subject of the ‘deutsche Misere’. In: Diskussion Deutsch 8 (1977) Heft 35. p 234-249.

- Joseph A. Kruse: Ein neues Lied vom Glück? (A new song of happiness?) Heinrich Heines Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. In: J. A. K.: Heine-Zeit. (Stuttgart/München 1997) p 238-255.

- Renate Stauf: Heinrich Heine. Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. In: Renate Stauf/Cord Berghahn (Editors): Weltliteratur II. Eine Braunschweiger Vorlesung. (Bielefeld 2005). p 269-284.

- Jürgen Walter: Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen. In: Heinrich Heine. Epoche — Werk — Wirkung. Edited by Jürgen Brummack. (Beck, München 1980). p 238-254.

External links[edit]

- German text at German Wikisource [1]

- German text at Project Gutenberg [2]

А. В. Ерохин

Литературное наследие и политико-литературная оппозиция в ГДР: случай Вольфа Бирмана

Ерохин Александр Владимирович,

доктор филологических наук,

заведующий кафедрой издательского дела и книговедения

Удмуртского государственного университета (Ижевск).

E-mail: erochin@yandex.ru.

Аннотация: Поэтическое творчество Вольфа Бирмана (Wolf Biermann, род. 1936) рассматривается в контексте «бардовского» песенного движения в Германии, в случае Бирмана тесно смыкающегося с политическим инакомыслием в ГДР. Определяются основные источники влияния на творчество Бирмана: театр кабаре начала ХХ века, пропагандистский театр 20-х годов, лирика Ф. Вийона, Г. Гейне, Б. Брехта, музыка Г. Эйслера. Проводятся типологические параллели между Бирманом и В. Борхертом, а также Е. Шварцем и Ф. Гельдерлином.

Annotation: The paper approaches the question of literary heritage and political opposition in the GDR by considering the lyrics of Wolf Biermann as a key representative of the German “Liedermacher” movement in the 60-70s. The essay demonstrates that Biermann’s poetry roots in different literary traditions, in cabaret and political theatre of the 20s, in Villon, Heine, Brecht et al.

Ключевые слова: авторская песня, политический протест, разделение Германии, баллада.

Key words: Liedermacher movement, political protest, the divided Germany, ballad.

Вольф Бирман (Wolf Biermann), современный немецкий поэт-песенник (Liedermacher), родился в 1936 г. в Гамбурге в семье еврейского рабочего-коммуниста, убитого нацистами в 1943 г. в Освенциме. В 1953 году Бирман переселился в ГДР и поступил в университет имени Гумбольдта в Восточном Берлине, где изучал сначала политическую экономию (1955—1957), а затем философию и математику (1959—1963). В перерыве Бирман два года проработал ассистентом режиссера в брехтовском «Берлинском ансамбле» (Berliner Ensemble).

В 1960 г. произошла знаменательная встреча Бирмана с композитором Хансом Эйслером (Hanns Eisler, 1898—1962), которая круто изменила его жизнь. При поддержке Эйслера Бирман начинает сочинять стихи и песни, становится профессиональным певцом и музыкантом. В 1961 г. он участвует в создании Берлинского рабочего и студенческого театра (b.a.t.), в котором на добровольной основе вместе работали профессионалы, рабочие и студенты. Театр будет закрыт в 1963 г., в том числе по причинам политическим: в 1961 г. цензурой была запрещена постановка пьесы Бирмана «За невестой в Берлин» (Berliner Brautgang), ставшей одним из первых литературных откликов на возведение Берлинской стены.

Первые стихи Бирмана печатаются в антологии «Стихотворения о любви» (Liebesgedichte, 1962). В этом же году Бирман выступает со своим первым концертом в Берлинской академии художеств. В 1965 г. в Западной Германии в свет выходит его первая книга стихов, «Арфа из колючей проволоки» (Die Drahtharfe). Еще раньше, в 1963 г., неудобному для партийного руководства ГДР Бирману после двухлетнего кандидатского стажа отказывают в приеме в Социалистическую единую партию Германии (СЕПГ). Конфликт с СЕПГ еще более обостряется после того, как в 1964 г. поэта пригласили с гастролями в Западную Германию. Бирману запрещают печататься и выступать с концертами в ГДР, обвиняя его в «классовой измене» и «непристойности». Газета «Нойес Дойчланд» (Neues Deutschland) обрушивается на Бирмана за его «анархизм» и «буржуазный индивидуализм», помноженный на ницшеанскую идеологию «сверхчеловека»1. Наступает одиннадцатилетний период почти полной общественной изоляции, прерывающийся отдельными политическими заявлениями Бирмана (так, в 1968 г. он поддержал «Пражскую весну» и ее лидера Александра Дубчека), публикациями стихов и выпусками музыкальных альбомов в ФРГ2.

В ноябре 1976 г. Бирман получает приглашение на гастроли в Западную Германию. Через три дня после начала турне, 16 ноября, политбюро ЦК СЕПГ лишает его гражданства, мотивируя свое решение тем, что его гастрольная программа направлена против ГДР и мировой системы социализма. В поддержку Бирмана выступили некоторые ведущие деятели культуры ГДР, в том числе инициатор этой акции Штефан Хермлин (Stephan Hermlin), а также Штефан Хайм (Stefan Heym), Юрек Беккер (Jurek Becker), Фолькер Браун (Volker Braun), Криста Вольф (Christa Wolf), Сара Кирш (Sarah Kirsch), Гюнтер Кунерт (Günter Kunert) и Хайнер Мюллер (Heiner Müller). Фактическая высылка Бирмана из ГДР и последовавшие затем протесты многими считается началом краха СЕПГ и Германской Демократической Республики3.

Диссидентство Бирмана в своей основе едва ли было «буржуазно-индивидуалистическим» или тем более «ницшеанским». Он всегда подчеркивал свои левые, марксистские и социалистические убеждения, защищая, наряду с такими оппозиционными мыслителями ГДР, как его друг Роберт Хавеман (Robert Havemann, 1910—1982) и Вольфганг Харих (Wolfgang Harich, 1923—1995) «классический» марксизм против его официальной партийной интерпретации в ГДР.

Антиавторитарный, оппозиционный марксизм Бирмана дополняется иными источниками протеста, идущими от его занятий «бардовской» поэзией. Бирман — яркий представитель послевоенного поколения авторской песни в Германии, восходящей к немецкому театру кабаре начала ХХ века с его критическими, свободолюбивыми тенденциями, к лирике Брехта и к революционному немецкому «агитпропу» двадцатых — начала тридцатых годов. В шестидесятые — семидесятые годы как в Западной, так и Восточной Германии на волне антивоенного движения и студенческих протестов распространяется движение авторской политической песни. Наряду с Бирманом здесь следует упомянуть западных немцев Франца Йозефа Дегенхардта (Franz Josef Degenhardt, род. 1931), Дитера Зюверкрюпа (Dieter Süverkrüp, род. 1934), Ханнеса Вадера (Hannes Wader, род. 1942), Константина Веккера (Konstantin Wecker, род. 1947), а также Беттину Вегнер (Bettina Wegner, род. 1947) из ГДР.

Главным учителем для Бирмана, по его собственному выражению, «мастером» остается Бертольт Брехт. Сам Бирман в своих интервью подчеркивал, что ему интересен весь Брехт, как ранний, так и поздний: «Если бы Брехт не сделал ничего иного, кроме как переложил стихами Коммунистический манифест, — что он, к сожалению, пробовал делать (интересный опыт, надо сказать), — то и тогда он был бы важнее и интереснее, чем мы со всей нашей болтовней»4. Рядом с Брехтом он ставит Ханса Эйслера. В особенности Бирман ценит сценическую обработку Брехтом в 1932 г. романа Горького «Мать», к которой Эйслер написал одноименную кантату. По словам Бирмана, «Мать» Брехта и Эйслера явилась вершиной левого агитационного искусства в веймарской Германии5. В целом брехтовская и эйслеровская традиция музыкально-политического театра объединяет Бирмана с другими представителями авторской песни по обе стороны «железного занавеса». В современных исследованиях эта линия обозначается как «музыкальное измерение “социализма с человеческим лицом”»6.

Не менее важна для Бирмана ранняя поэзия Брехта, в первую очередь «Домашние проповеди» (Hauspostille, 1927). От раннего Брехта Бирман перенял витальную непосредственность лирического высказывания, натурализм и иронию вкупе с политической ангажированностью «прикладной поэзии». Как и Брехт, Бирман предпочитает жанр народной «городской баллады» или «нравоучительной песни» (Bänkelsang), используя балладный повествовательный сюжет для политической критики. Интерес к «дерзкой душе» (freche Seele) еще одного классика балладного жанра, Франсуа Вийона, Бирман также унаследовал от своего «мастера», написавшего, как известно, балладу «О Франсуа Вийоне», а также подражавшего Вийону в «Трехгрошовой опере» и стихотворении «О бедном Б. Б.»7.

В своем интересе к Вийону Бирман не уникален среди литераторов ГДР. До него к французскому поэту обращались такие поэты Восточной Германии, как Луис Фюрнберг («Безымянный брат. Жизнь, рассказанная в стихах», Der Bruder Namenlos. Ein Leben in Versen,)8, Петер Хухель («Перед Нимом 1452», Vor Nimes 1452)9, Харальд Герлах («Из наследия Вийона», Aus dem Nachlaß des Villon)10, Иоганнес Бобровский («Вийон 2», Villon 2)11 и Георг Маурер («Вийон», Villon, из цикла «Фигуры любви», Gestalten der Liebe)12.

Бирман посвящает французскому лирику «Балладу о поэте Франсуа Вийоне» (Ballade auf den Dichter Francois Villon, 1964). Он частично следует за формой вийоновой баллады, сохраняя, например, ее «посылку». Баллада Бирмана гротескна и частью фантастична: в ней описывается визит «Франца» (Franz) Вийона в квартиру немецкого поэта и его трагикомическое столкновение с реальностью ГДР шестидесятых годов. Он принимает участие в пирушках приятелей Бирмана, успевая при этом с приходом сотрудников госбезопасности спрятаться в шкафу. Устав скрываться, он выбирается из квартиры и отправляется гулять по Берлинской стене; в него стреляют пограничники, но пули проходят сквозь него, не причиняя вреда. Вернувшись домой, он изрыгает попавшие в него пули. Вийона приходят арестовывать полицейские, но в шкафу они обнаруживают лишь остатки рвоты13.

Образ Вийона в балладе Бирмана лишен какой-либо идеализации: это грязный, пьяный, дерзкий бродяга-сквернослов. Вийон у Бирмана со своей шокирующей, провокационной, грубой телесностью бросает вызов нестерпимому лицемерию и невнятному бюрократическому языку новой социалистической Германии (и попутно ее официального печатного органа — газеты «Нойес Дойчланд»)14.

Гротескная, асоциальная чувственность «Франца Вийона» у Бирмана является жестом радикального эпатажа со стороны автора, вытесненного официальной политикой и цензурой за пределы «социалистической публичности». Маргинальность положения Бирмана в публичном пространстве ГДР делает его поэзию предельно откровенной как в политическом, так и в приватном смысле. Изолированный в своем частном существовании, окруженный недругами и соглядатаями, поэт во многом вынужденно балансирует между риторическим надрывом и грубым физиологическим натурализмом. Это состояние имеет определенное сходство с литературной ситуацией Вольфганга Борхерта, земляка Бирмана, представителя послевоенной «литературы развалин», также объединявшего в своем творчестве экспрессионистскую взвинченность и натуралистическую откровенность.

Бирман, обычно охотно цитирующий других авторов, не ссылается на тексты Борхерта. Тем не менее, в его стихах есть определенные типологические параллели с Борхертом, связанные, прежде всего, с мотивами Гамбурга, родного города двух авторов. Например, баллада Бирмана «Смерть в Алтоне» (Tod in Altona, 1995) по своей интонации, одновременно иронической и меланхолической, напоминает стихи и рассказы Борхерта, посвященные Гамбургу. У Бирмана сатирический рассказ о вдове погибшего во время Второй мировой войны нацистского командира подводной лодки обрамляется характерным экспрессионистским, «борхертовским» пейзажем Гамбурга: «Вороны кружат над домом престарелых / И призывают ночь своим черным карканьем…»15.

С Борхертом Бирмана сближает общий травматический опыт мировой войны. В предисловии к собранию своих стихотворений Бирман так описывает свое переживание бомбардировки Гамбурга авиацией союзников летом 1943 года: «…крохотные часы моей жизни расплавились в моей грудной клетке, они остановились в огненном шторме той единственной ночи. Мне тогда было шесть с половиной лет, и таким я остался навсегда. Я — поседевший ребенок, который до сих пор преисполнен изумления»16. Это высказывание Бирмана можно считать программным.

Непосредственность и искренность Борхерта, несмотря на отсутствие конкретных ссылок на него у Бирмана, несомненно, повлияли на творчество последнего. Борхерт занимает свое место в ряду явных и неявных учителей Бирмана, от поэта-трикстера «Франца Вийона» с его физиологическими откровенностями до либертина Генриха Гейне и мастера политической лирики Бертольта Брехта.

Своих любимых поэтов Бирман противопоставляет такому герметическому автору, как Рильке. В позднем стихотворении «Рильке Рильке» (Rilke Rilke, 1986/1995) австрийский поэт презрительно назван «пустой коробочкой для пудры» (leere Puderdose)17. Его темный слог, «чья поверхностность претендует на глубину», нравится лишь «невеждам и неплательщикам налогов»18. При этом Бирман порой не может скрыть восхищения артистизмом Рильке: «И все же поэту / удается иная связка строф, от которой / я белею от зависти, и мой грубый немецкий / по-детски удивляет меня: язык, такой гибкий и послушный, / как же это выходит, что от увядших рук / рождаются такие анемоны, сладкий дар языка…»19. Не обходит вниманием Бирман и русские мотивы у Рильке, которые у него также осмысляются в амбивалентном ключе: «Здесь кровь Спасителя пенится в русском кубке, / Вырезанном из дерева…»20.

В свою очередь, меланхоличные, порой критические нотки слышны в стихотворениях Бирмана, посвященных его кумиру Брехту. Фамилия Брехта обыгрывается по созвучию с немецким словом «gebrochen» (сломанный, надломленный). Особенно достается его наследникам, ставшим партийными функционерами в ГДР, в стихотворении «Брехт, твои потомки» (Brecht, deine Nachgeborenen, 1967): «Верно, их голоса уже не хрипят / — ведь им нечего более сказать / И лица их уже не искажены, это так: / Они стали безликими. Наконец / Человек стал волком для волка»21. Бирман отождествляет себя с «живым» Брехтом и объединяется с ним против «культурных бонз», паразитирующих на его наследии. В стихотворении «Реализм у Брехта» (Realismus bei Brecht, 1974) «надломленность» брехтовской традиции передается по наследству поколению Бирмана: «Брехт, он показал нам расколотый мир / в своем отшлифованном зеркале. Мы, новейшие, / разбили зеркало / и показываем целый мир / в его осколках»22.

Кроме Брехта, Вийона и Рильке, в поэтическом арсенале Бирмана обнаруживаются аллюзии на революционно-демократических поэтов «Молодой Германии», и прежде всего Генриха Гейне, под влиянием которого Бирман в 1964—1972 гг. написал поэму «Германия. Зимняя сказка» (Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen), изданную в Западной Германии в 1972 г. и ярко выразившую скорбь и негодование автора, вынужденного жить в разделенной отчизне. Литературная критика ГДР проигнорировала поэму, тогда как в Западной Германии она была встречена с большим интересом23. В отношении Бирмана к Гейне, отразившемся, среди прочего, в его «Германии. Зимней сказке», проявляется характерное для современного немецкого поэта противоречие между оптимистическим «принципом надежды» и печалью по поводу бесславной смерти свободы и революции в затхлом сталинистском режиме ГДР24.

В поисках опоры и вдохновения для своего антиавторитарного художественного творчества Бирман обращается и к русской, точнее — советской литературной традиции. В 1971 г. в Мюнхенском камерном театре (Münchner Kammerspiele) было поставлено его «большое действо об убийце дракона в восьми актах с музыкой» (Große Drachentöterschau in acht Akten mit Musik) под названием «Дра-дра» (Der Dra-Dra). Пьеса, напечатанная в 1970 г. в Западном Берлине, представляла собой переделку известной пьесы советского драматурга Евгения Шварца «Дракон» (1943). Бирман использовал текст Шварца для критики восточногерманского режима. Его охотник на драконов Ханс Фольк (Hans Folk) сражается с умножающимися драконьими головами, питающимися мелкобуржуазными страхом и косностью, которые прорастают из-под каменных «глыб» омертвевшей социалистической идеологии.

Западногерманская критика отнеслась к мюнхенской постановке критически. Так, Эрнст Вендт из газеты «Цайт» (Die Zeit) обращает внимание читателей на неуместность «драконьей» метафорики в условиях Западной Германии: по мнению критика, постановка, атакующая тоталитарный режим за его географическими пределами, бьет мимо цели, поскольку в ФРГ дракона зовут иначе, и имя ему «капитализм». Но этого «монстра» постановщики так и не смогли вывести на сцену; в результате инсценировка Хансгюнтера Хейме (Hansgünter Heyme) «в течение более трех часов сражается с противником, который в конце так и не появится перед нами»25.

Итог поэтическому развитию Вольфа Бирмана подводить еще рано. Он продолжает работать, и от него можно ожидать новых свершений, несмотря на несколько двусмысленную популярность, окружающую его в сегодняшней Федеративной Республике Германии. (Бирман, в частности, сильно смутил своих сторонников и доброжелателей тем, что активно поддержал агрессию США в Ираке). В качестве предварительного вывода можно подчеркнуть, что богатая литературными аллюзиями поэзия Бирмана своим центральным нервом имеет тему немецкого раскола и единства, причем далеко не только в политическом и идеологическом смысле. Ярчайшим образом эта проблематика «расколотого неба» Германии выражена в знаменитой «Балладе о прусском Икарe», в которой вылитый из чугуна Икар на одном из мостов через Шпрее в Восточном Берлине застывает между небом и землей, полетом и падением, окутанный колючей проволокой раздора и изоляции. Не только восточная часть страны, но и вся Германия в этом стихотворении оказывается «островом», омываемым «свинцовыми волнами». Сам поэт видит себя в положении прусского Икара со спутанными крыльями, рвущегося к свободе, но останавливающегося на границе в мучительном раздумье и беспокойстве26.

Бирман ищет пути преодоления извечного немецкого раскола — как политического, так и культурного. В поисках решения этой немецкой проблемы он обращается к Фридриху Гельдерлину. По его мнению, именно Гельдерлину удалось осмыслить и преодолеть разрыв в немецкой культуре между рациональным и чувственным, между радостью и отчаянием. Бирман в своих интервью любит ссылаться на роман Гельдерлина «Гиперион», в котором содержатся суровые упреки немцам, ставшим «благодаря своему трудолюбию и науке, благодаря самой своей религии еще большими варварами»27. В то же время, именно в «Гиперионе» Бирман находит спасительную формулу для решения проблемы современной культуры, движущейся в пространстве между надеждой и разочарованием. Бирман ссылается на последнее письмо Гипериона к Беллармину, в котором, среди прочего, говорится о том, «что сердцу откроется новая благодать, если оно выдержит и вытерпит глухую полночь скорби»28. Во всяком случае, преодоление трагического разделения Германии Бирман еще в 1981 году видел в словах гельдерлинова Гипериона: «Примиренье таится в самом раздоре, и все разобщенное соединяется вновь»29.

Примечания

1 Neues Deutschland, 5.12.1965. См. также: H. K. Rosenthal. The German Democratic Republic and Its Marxist Dissidents: The Process of Control // Australian Journal of Politics & History. Vol. 24, Issue 3, December 1978. Pp. 352-355.

2 Среди песенных альбомов Бирмана шестидесятых — начала семидесятых следует назвать «Шоссейную улицу, 131» (1968; Chausseestrasse, 131 — в то время адрес Бирмана в Берлине), «Не жди лучших времен» (1973; Warte nicht auf bessere Zeiten), «Оо — да!» (1974; Aah — Ja!), «Песни о любви» (1975; Liebeslieder), «Есть жизнь перед смертью» (1976; Es gibt ein Leben vor dem Tod).

3 Ср., например: W. Emmerich. Literarische Öffentlichkeit und Zensur in der DDR // Deutsche Literatur zwischen 1945 und 1995. Eine Sozialgeschichte. Hrsg. von H. A. Glaser. Bern, Stuttgart, Wien, 1997. S. 137f.

4 H. Schmidt, H. Fehervary. Interview mit Wolf Biermann // The German Quarterly. Vol. 57, Nr. 2 (Spring, 1984), pp. 276-277.

5 Ibid., p. 272.

7 О фигуре Вийона у Брехта и в поэзии Германской Демократической Республики см.: J. P. Wieczorek. «Doch seine freche Seele lebt wohl noch…»: The Figure of Francois Villon in East German Poetry // German Life and Letters 42:2 (January 1989), pp. 129-144.

8 L. Fürnberg. Gesammelte Werke in sechs Bänden. Berlin/Weimar, 1965, Bd. 2. S. 19.

9 P. Huchel. Gesammelte Werke in zwei Bänden. Frankfurt a.M., 1984. Bd. 1. S. 191f.

10 H. Gerlach. Aus dem Nachlaß des Villon // H. Gerlach. Mauerstücke. Berlin/Weimar, 1979. S. 75.

11 J. Bobrowski. Sarmatische Zeit. Berlin, 1961. S. 52.

12 G. Maurer. Gestalten der Liebe. Halle, 1965. S. 142f.

13 W. Biermann. Nachlaß 1. Köln, 1977. S. 45-49.

14 J. P. Wieczorek., a. a. O., S. 138.

15 «Kräh’n kreisen überm Altersheim / Und schreien schwarz die Nacht herbei…» // W. Biermann. Alle Gedichte. Köln, 1995. S. 154.

16 «…daß die kleine Lebensuhr in meinem Rippenkäfig auch festgebrannt ist, sie ist stehengeblieben im Feuergebläse dieser einen Nacht. Sechseinhalb Jahre war ich damals, und so alt blieb ich mein Leben lang. Ich bin ein graugewordenes Kind, das immer noch staunt». Ibid., S. 180-181.

17 Ibid., S. 140.

18 «So was gefällt den Steuerhinterziehern und Banausen / So dunkle Worte, deren Seichtigkeit auf Tiefe pocht…». Ibid., S. 140.

19 «Und doch, es glückt / Dem Dichter manches Strophenbündel, das mich weiß / Vor Neid macht, und mit kindlichem Erstaunen trifft / Mein grobes Deutsch mich: Deutsch so biegeschlank / Wie kommt das bloß, daß aus der abgewelkten Hand / So Buschwindröschen blühn, der Sprache süßes Gift…». Ibid., S. 140.

20 «Da schäumt des Heilands Blut im Russen-Becher / Aus Holz geschnitten…». Ibid., S. 140.

21 «Stimmt: ihre Stimme ist nicht mehr heiser / — sie haben ja nichts mehr zu sagen / nicht mehr verzerrt sind ihre Züge, stimmt: / Denn gesichtslos sind sie geworden. Geworden / Ist endlich der Mensch dem Wolfe ein Wolf». Ibid., S. 49.

22 «Brecht, die zerbrochene Welt / zeigte er uns in seinem geschliffenen / Spiegel. Wir Neueren / haben nun auch den Spiegel zerbrochen / und zeigen in den Scherben die Welt ganz». Ibid., S. 51.

24 Biermann W. Über «Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen»: Heinrich Heine // Biermann W. Klartexte im Getümmel. 13 Jahre im Westen. Von der Ausbürgerung bis zum November-Revolution. Hrsg. von Hannes Stein. Köln, 1990. S. 217-221.

25 Wendt E. Politik als Spiegelfechterei. Wolf Biermanns «Der Dra-Dra» in München // Die Zeit, 30.4.1971, Nr.18.

26 Стихотворение помещено на немецком языке в: M. S. Fries. Fetters of Allusion: The Daedalus Myth in the German Democratic Republic // The German Quarterly, Vol. 59, No. 4 (Autumn, 1986), pp. 534-535.

27 Гельдерлин Ф. Гиперион. Стихи. Письма. М., Наука, 1988. 247-248. На это место в «Гиперионе» Бирман ссылается, в частности, в интервью на Немецком радио (Deutschlandfunk) 1 ноября 2000 г. См.: http://www.dradio.de/dlf/sendungen/interview_dlf/156474/.

28 Гельдерлин Ф. Указ. соч. С. 253.

29 Там же. С. 257. См. также: «I’d Rather Be Dead than Think the Way Kunert Does»: Interview with Wolf Biermann and Günter Kunert // New German Critique, Nr. 23 (Spring — Summer, 1981), p. 52.

Вольф Бирман

«Я не настолько безумен, чтобы верить в Бога; я еще безумнее — я верю в его творения.»

Вольф Бирман

2009

Фото: Thomas Ammerpohl.

ВОЛЬФ БИРМАН (нем. Wolf Biermann, род. в 1936) — немецкий поэт, композитор, бард, в 1970-х бывший одним из самых известных диссидентов в ГДР.

Вольф Бирман родился 15 ноября 1936 г. в Гамбурге, где закончил гимназию Генриха Герца. Его биография отражает трагедию «двух Германий» и мира, который более полувека был расколот на два «лагеря». Отец Бирмана — работник гамбургской верфи, коммунист, участник антифашистского Сопротивления, погиб в Освенциме в 1943-ем. Сам Вольф вместе с матерью чудом остался в живых после мощнейших бомбардировок Гамбурга. В 17 лет он эмигрировал в ГДР, следуя своим политическим убеждениям и не желая жить в стране, где «нацистам среднего звена» было позволено занимать государственные и муниципальные должности. Первое время после переезда его опекала супруга Эриха Хоннекера.

Молодой Бирман слыл социал-демократическим идеалистом, штудировал философские тексты, изучал политическую экономию, создал Рабочий и студенческий театр в Берлине. Уже в начале 60-ых у него, как автора и исследователя, начались проблемы: режим костенел в бюрократизме и догматичности, официальное отношение к революционным романтикам, верившим в то, что Восточная Германия — место, стартующей утопии, становилось все более враждебным.

В начале 1960-х годов Бирман изучал философию и математику в Берлинском университете имени Гумбольдта. Тогда же начал сочинять стихи. В 1961 году основал восточноберлинский «Рабочий и студенческий театр». Поставленная там пьеса о проблеме Берлинской стены была запрещена. Вольф Бирман получил первоначальное музыкальнотеатральное образование в знаменитом «Берлинском ансамбле” Брехта и до сих пор называет Эйслера «Mein Meister”

В это время отношения поэта с властями ГДР резко ухудшаются.

Его выгнали из университетской докторантуры (с извинениями диплом вручили в 2008-ом).

В 1976-ом во время кёльнского концерта бард позволил себе в открытую насмехаться над государственными порядками соцстран и его заочно лишили гражданства с формулировкой «за серьезные нарушения обязанностей гражданина» (партия добавила «контрреволюционер, ренегат, платный агент классового врага»).

В ноябре 1976 бард едет на гастроли в ФРГ, и обратный въезд в ГДР ему запрещают. Фактическая высылка Бирмана спровоцировала отъезд из ГДР целого ряда деятелей культуры, включая певицу Нину Хаген. Нина Хаген — приёмная дочь барда — бесстрашно написала письмо в министерство иностранных дел, в котором заявила, что не хочет оставаться в государстве, в котором не разрешают жить такому замечательному человеку, как Вольф Бирман. В министерстве отнеслись к письму достаточно серьёзно и предложили певице в течении четырёх дней убраться из страны. Нина Хаген запаковала чемоданы и улетела в Гамбург к своему приёмному отцу, который помог ей тут же получить контракт с концерном Columbia. Оставшись на Западе, Бирман продолжает сочинять и исполнять песни. Поддержал военные операции в Косово (1999) и Ираке (2003)

Einschlaf und Aufwachelied

Schlaf ein, mein Lieb, sonst ist die Nacht

Vorbei und hat uns nicht Gebracht

Als wirre irre Fragen

Gib mir dein’ Arm und noch ein’ Kuss

Ich muss ja durch den Schlafeflu;

Und will dich r;ber tragen.

Wach auf, mein Lieb, du schl;fst ja noch!

Komm aus den dunklen Tr;umen hoch

Und freu dich an uns beiden!

Die Sonne hat l;ngst dein Gesicht

Gestreichelt, und du merkst das nicht

— das mag ich an dir leiden.

На пороге сна и пробуждения

(песня)

Усни, родная, эта ночь

Сомнений, дум неясных, прочь

Бежит, не дав ответа

Дай руку: через реку снов

Перенести тебя готов

Лишь поцелуй – за это.

Проснись, любимая, проснись!

На радость нам с тобой вернись

Из сумрачного края!

Луч солнца милые черты

Ласкает, и не видишь ты

Как я, любя, страдаю.

Перевел М.Колчинский

Auf dem Friedhof am Montmatre

Auf dem Friedhof am Montmatre

Weint sichaus der Winterhimmel

Und ich spring mit d;nnen Schuhen

;ber Pf;tzen, darin schwimmen

Kippen, die sich langsam ;ffnen

K;tel von Pariser Hunden

Und so hatt’ ich nasse F;;e

Als ich Heines Grab gefunden.

Unter wei;em Marmor frieren

Im Exil seine Gebeine

Mit ihm liegt da Frau Mathilde

Und friert er nicht alleine.

Doch sie hei;t nicht mehr Mathilde

Eingemei;elt in dem Steine

Steht da gro; sein gro;er Name

Und darunter blo;: Frau Heine.

Und im Kriege, als die Deutschen

An das Hakenkreuz die Seine-

Stadt genagelt hatten, st;rte

Sie der Name Henri Heine!

Und ich wei; nicht wie, ich wei; nur

Das: er wurde weggemacht

Und wurd wieder angeschrieben

Von Franzosen manche Nacht.

Auf dem Friedhof am Montmatre

Weint sichaus der Winterhimmel

Und ich spring mit d;nnen Schuhen

;ber Pf;tzen, darin schwimmen

Kippen, die sich langsam ;ffnen

K;tel von Pariser Hunden

Und ich hatte nasse F;;e

Als ich Heines Grab gefunden.

На кладбище Монмартра

Здесь, на кладбище Монмартра

Небо дышит зимней стужей

Я в ботинках модных, тонких

Перепрыгиваю лужи

В лужах плавают окурки

И дерьмо собачек милых

Хоть мои промокли ноги

Гейне я нашел могилу.

Белым мрамором укрытый

Прах его в изгнаньи стынет

С ним лежит его Матильда

С тех далеких пор доныне

Но не только как подруга

В камне высечена тайна

Текст, и в нем поэта имя

Ниже просто: «Frau Heine“.

В ту пору, когда чернела

Всюду свастика на Рейне

Было предано проклятью

Это имя — Генрих Гейне.

Хлеб изгнанника не сладок

Только точно знаю я

Что не отдали французы

Гейне мраку забытья.*

Здесь, на кладбище Монмартра

Небо дышит зимней стужей

Я в ботинках модных, тонких

Перепрыгиваю лужи

В лужах плавают окурки

И дерьмо собачек милых

Пусть мои промокли ноги

Гейне я нашел могилу.

Перевел М.Колчинский

*В 1901г. датский скульптор Луис Хассельрюс установил на могиле мраморный бюст поэта

и высек его стихотворение „Wo?“ («Где?»).

(Прим. переводчика)

Gro; es Rot bei Chagall

Ja, das ist ein anderer

Chagall, nicht der ewige

Fiedler, nicht wieder

im Blumenstrau;

das labile Liebespaar

in stabiler Schwebe

Ein Ikarus st;rzt aus Odessas

Himmel. St;rzt in eine b;uerliche

Menschheit. M;nner, Frauen

glotzen, auf niedrigen D;chern

sitzend, stechend, gelassen

der Fall war erwartet worden

Ich aber kann mitansehn

wie die da mitansehn

die Landung zum Tode, gro;

Blutet ein Rot

Chagall, sein Gro;es Rot

Blutet den Berg herunter

Dann

aus der braunschen R;hre tropft

Holocaust ins Haus. Rinnsal

aus Hollywood ein Rot

das kleine Rot

kriecht unter den Teppich.

Большой алый цвет Шагала*

Да, это другой

Шагал, не тот вечный

скрипач, не снова

в букете

лабильная пара влюбленных

в стабильном паренье

Икар падает с неба

Одессы. В сельских пределах

паденье. Мужчины и женщины

глазеют, на низких кровлях

сидя, стоя, невозмутимо

крушения ожидая

и я могу быть свидетелем

как те, что в полях наблюдают

падение к смерти. Большой

кровоточит алый цвет

Шагала, его большой алый цвет

кровотоком сверху вниз

Тогда

из коричневых труб стекал

Холокост в мой дом. Струйка

алого цвета из Голливуда

крохотный алый цвет

стекал в никуда

Перевел М.Колчинский

*»Падение Икара». Холст. Масло. 213×198. Париж, Mузей совр. иск.

Wenn die Sonne eine Stunde

Sp;ter zu mir kommt am Morgen

westw;rts bis nach Altona

Auf dem Weg von Israel, dann

Lieg ich wach und warte schon auf

ihre News und Totenklagen

Steine, Pizzeria, Panzer

In Jerushalajm Al-Aksa

Hamas, Libanon, Hisbolla

Sederabend in Netanya

Tel Aviv. Tod in der Disko

Haifa, Bethlehem und Jaffa

Siehste: Ick brauch jar keene Zeitung

Tagesschau, die doppelt qu;lt

meine Sonne hat mir schon alles

hier in Deutschland ;ber alles

viel wahrhaftiger erz;hlt

Schlimmer als am Bauch die Bomben

Schlimmer als in Knabenh;nden

die Kalaschnikow, die Steine da

Schlimmer noch ist dieser blinde

Ha; von klein auf eingef;ttert

in die m;rderische Brut da, ja…

Paradiesisch siebzig Jungfraun

Winken jedem Selbstmordm;rder

Ruhm und Rente winken irdisch

Der Familie solcher Opfer

Denn wo Gott so ;bergro; wird,

schrumpfen seine Menschenkinder

Siehste: Ick brauch jar keene Zeitung

Tagesschau, die doppelt qu;lt

meine Sonne hat mir schon alles

hier in Deutschland ;ber alles

viel wahrhaftiger erz;hlt

Und blutjunge Juden stiefeln

Angstvoll, von der Welt ge;chtet

als Besatzer durch die Westbank da

Rache wird ger;cht mit Rache

Keiner kommt mit saubren H;nden

aus dem Bruderkrieg am Jordan

Ob die Pal;stina-Fahne

;berm Sarg liegt, ob der blaue

Davidstern auf wei;em Laken

Ach! bei dem Begr;bnis sind auf

Beiden Seiten M;ttertr;nen

salzig, salzig, salzig, salzig

Когда солнце часом позже

Когда солнце часом позже

от Израиля на запад

Утром в Альтону приходит

Я не сплю. Я жду оттуда

новостей и жалоб горьких

Камни, пиццерия, танки

В Иерушалаиме Аль-Акса

Хамас, Ливан, Хезболла

Седер вечером в Нетании

Тель-Авив. И смерть на диско

Хайфа, Вифлеем и Яффа

Видишь: не нуждаюсь я в газетах

шоу мне претит вдвойне

мое солнце рассказало

здесь, в Германии, всю правду

обо всем всю правду мне

Хуже, чем под платьем бомбы

Хуже, чем в руках мальчишки

и Калашников, и камни

Это – ненависть слепая

Та, что с малых лет вскормила

В человеке людоеда, да…

Семь десятков юных гурий

Ждут в раю самоубийцу

А семье его пророчат

Славу и блага земные

Там где Бог велик чрезмерно

Меньше там его подобий

Видишь: не нуждаюсь я в газетах

шоу мне претит вдвойне

мое солнце рассказало

здесь, в Германии, всю правду

обо всем всю правду мне

И в тревоге по Вестбанку

Ходят юные евреи

мир клеймит их: оккупанты

Месть рождает месть взаимно

Чистых рук в братоубийстве

нет на водах Иордана

Палестинский флаг на гробе

Иль покрыт он белым флагом

с голубой звездой Давида

Ах! Слезы матери у гроба

Одинаково повсюду

Жгучи жгучи жгучи жгучи

Перевел М.Колчинский

© Copyright: Михаил Колчинский 2, 2009

Свидетельство о публикации №1902223106

http://www.stihi.ru/2009/02/22/3106

Heimat

Ich suche Ruhe und finde Streit

Wie süchtig nach lebendig Leben

Zu kurz ist meine lange Zeit

Will alles haben, alles geben

Weil ich ein Freundefresser bin

Hab ich nach Heimat Hunger – immer!

Das ist der Tod, da will ich hin

Ankommen aber nie und nimmer

Tief schlafen, träumen ohne Schrei

Aufwachen und noch bißchen dösen

Schluck Tee, Stück Butterbrot dabei

Leicht alle Menschheitsfragen lösen

Im ewig jungen Freiheitskrieg

Das Unerträgliche ertragen:

Die Niederlage steckt im Sieg

Trotz Furcht: Die Liebe tapfer wagen!

Zur Nacht ein Glas Rioja-Wein

Weib! Weib, du bist mein Bacchanalchen

Laß Tier uns mit zwei Rücken sein!

Flieg du nochmal und ich nochmalchen

Dir bau ich den Balladen-Text

Wenn meinem Salamander wieder

Der abgebissne Schwanz nachwächst

Und so, ihr Lumpen, macht man Lieder

Ich suche Ruhe und finde Streit

Wie süchtig nach lebendig Leben

Zu kurz ist meine lange Zeit!

Will alles haben, alles geben

Weil ich ein Feindefresser bin

Hab ich nach Rache Hunger – immer!

Das ist der Tod, da will ich hin

Ankommen aber nie und nimmer

Родина

Ищу покой, но всюду бой.

Жизнь жизнью наполняя в мире

Мне жить доверено судьбой,

Имея всё, и всё транжиря.

Мне, едоку друзей, всегда

Отчизной свой насытить голод

Так хочется. Стремлюсь туда,

Но чувствую могильный холод..

Люблю поспать подольше я

Не торопиться встать с восходом,

Решать вопросы бытия

За чашкой чая с бутербродом.

Свободу новая война

Несёт. И новые прозренья:

Страх одолеть любовь должна,

В победе скрыто пораженье.

Стакан вина – залог удач,

О женщина, моя вакханка.

Зверь о двух спинах мчится вскачь,

Рысь, иноходь, галоп, стоянка …

Тебе стихов сплету венец,

Лишь должен мой тритон,хоть тресни,

Хвоста откушенный конец

Вновь отрастить – и будут песни!

Ищу покой, но всюду бой.

Жизнь жизнью наполняя в мире

Мне жить доверено судьбой,

Имея всё, и всё транжиря.

Мне, едоку врагов, всегда

Отмщеньем свой насытить голод

Так хочется. Стремлюсь туда,

Но чувствую могильный холод.

Перевод Daniel Kogan

http://kiebitz.livejournal.com/9503.html

Использованные источники:

http://www.wolf-biermann.de/

http://placeboworld.org.ua/?p=596

http://www.darksage.ru/publ/543-1-0-244

http://www.2zvuka.ru/music/Wolf+Biermann

http://gs-team.ru/home/547615318

Материал подготовила Ирина Валиулина

16/04/2012 —

Posted by |

Uncategorized

Комментариев нет.