Эрнст Теодор Амадей Гофман родился в 1776 году. Место его рождения -Кенигсберг. Поначалу в его имени присутствовал Вильгельм, но он сам изменил имя, так как очень сильно любил Моцарта. Его родители развелись, когда ему было всего 3 года, и его воспитывала бабушка — мать его матери. Дядя его был юристом и очень умным человеком. Отношения у них складывались довольно сложные, однако дядя оказал влияние на племянника, на развитие его различных талантов.

Ранние годы

Когда Гофман вырос, он тоже решил, что станет юристом. Он поступает в университет в Кенигсберге, после обучения служил в разных городах, его профессия — судейский чиновник. Но такая жизнь была не для него, поэтому он начал рисовать и музицировать, чем и пытался зарабатывать на жизнь.

Вскоре он встретил свою первую любовь Дору. На ту пору ей было всего 25, но она была замужем и уже родила 5 детей. Они вступили в отношения, но в городе начали сплетничать, и родственники решили, что нужно отослать Гофмана в Глогау к другому дядюшке.

Начало творческого пути

В конце 1790-х Гофман становится композитором, он взял себе псевдоним Иоганн Крейслер. Есть несколько произведений, которые достаточно известны, например, — написанная им в 1812 году опера под названием «Аврора». Также Гофман работал в Бамберге в театре и служил капельмейстером, а также был дирижером.

Так сложилась судьба, что Гофман вернулся на госслужбу. Когда он сдал экзамен в 1800 году, то стал работать асессором в Верховном суде Познани. В этом городе он и встретил Михаэлину, с которой вступил в брак.

Литературное творчество

Э.Т.А. Гофман произведения свои начал писать в 1809 году. Первая новелла называлась «Кавалер Глюк», ее напечатала Лейпцигская газета. Когда же он вернулся к юриспруденции в 1814 году, то одновременно писал и сказки, в том числе «Щелкунчик и Мышиный король». Во времена, когда Гофман творил, процветал немецкий романтизм. Если хорошенько прочитать произведения, то можно увидеть основные тенденции школы романтизма. Например ирония, идеальный художник, ценность искусства. Писатель демонстрировал конфликт, который происходил между реальностью и утопией. Он постоянно иронизирует над своими героями, которые пытаются найти в искусстве какую-то свободу.

Исследователи творчества Гофмана едины в своем мнении, что нельзя отделять его биографию, его творчество от музыки. Особенно, если наблюдать за новеллами -например «Крейслериана».

Все дело в том, что в ней главным героем является Иоганнес Крейслер (как мы помним, это псевдоним автора). Произведение представляет собой очерки, темы у них разные, но герой один. Уже давно признано, что именно Иоганн считается двойником Гофмана.

Вообще писатель — человек довольно яркий, он не боится трудностей, готов бороться с ударами судьбы, чтобы достичь определенной цели. И в данном случае это искусство.

«Щелкунчик»

Данная сказка была опубликована в сборнике в 1716 году. Когда Гофман создавал это произведение, то пребывал под впечатлением от детей своего приятеля. Детишек звали Мари и Фриц, их имена Гофман дал своим персонажам. Если прочитать Гофмана «Щелкунчик и мышиный король «, анализ произведения покажет нам моральные принципы, которые пытался передать автор детям.

Вкратце история такова: Мари и Фриц готовятся к Рождеству. Крестный всегда делает игрушку для Мари. Но после Рождества эту игрушку обычно забирают, так как она очень искусно сделана.

Дети приходят к елке и видят, что там целая куча подарков, девочка находит Щелкунчика. Эта игрушка служит для того, чтобы разгрызать орехи. Как-то Мари заигралась в куклы, и в полночь появились мыши, во главе со своим королем. Это была огромная мышь с семью головами.

Тогда игрушки во главе с Щелкунчиком оживают и вступают с мышами в бой.

Краткий анализ

Если сделать анализ произведения Гофмана «Щелкунчик», то заметно, что писатель постарался показать, как важно добро, мужество, милосердие, что нельзя оставлять кого бы то ни было в беде, надо помогать, проявлять смелость. Мари смогла рассмотреть в неказистом Щелкунчике его свет. Ей понравилось его добродушие, и она всеми силами старалась защищать своего любимца от противного брата Фрица, который вечно обижал игрушку.

Несмотря ни на что, она пытается помочь Щелкунчику, отдает сладости наглому Мышиному королю, лишь бы тот не причинял солдатику вред. Здесь демонстрируются смелость и мужество. Мари и ее брат, игрушки и Щелкунчик объединяются ради достижения цели — победы над Мышиным королем.

«Золотой горшок»

Данное произведение является также достаточно известным, и Гофман создавал его, когда в 1814 году к Дрездену подошли французские войска, которые вел Наполеон. При этом город в описаниях довольно реален. Автор рассказывает про быт людей, как они катались на лодке, ходили в гости друг другу, проводили народные гулянья и многое другое.

События сказки разворачиваются в двух мирах, это реальный Дрезден, а также Атлантида. Если делать анализ произведения «Золотой горшок» Гофмана, то можно увидеть, что автор описывает гармонию, которую в обычной жизни днем с огнем не сыщешь. Главным героем является студент Ансельм.

Писатель постарался красиво рассказать про долину, где растут прекрасные цветы, летают удивительные птицы, где все пейзажи просто великолепны. Когда-то там жил дух Саламандр, он влюбился в Огненную лилию и нечаянно послужил причиной разрушения сада князя Фосфора. Тогда князь выгнал этого духа в мир людей и рассказал, какое у Саламандра будет будущее: люди забудут про чудеса, он снова встретит свою любимую, появится у них три дочки. Саламандр сможет вернуться домой, когда его дочери найдут себе возлюбленных, готовых поверить, что чудо возможно. В произведении Саламандр тоже может видеть будущее и предсказывать его.

Произведения Гофмана

Надо сказать, что хотя у автора было очень интересные музыкальные произведения, тем не менее, он известен в качестве сказочника. Произведения для детей Гофмана достаточно популярны, некоторые из них можно прочитать маленькому ребенку, какие-то подростку. Например, если взять сказку про Щелкунчика, то она подойдет и для тех, и для других.

«Золотой горшок» — сказка довольно интересная, но наполненная аллегориями и двойным смыслом, где демонстрируются основы нравственности, которые актуальны и в наши непростые времена, например, умение дружить и помогать, защищать, проявлять мужество.

Достаточно вспомнить и «Королевскую невесту» — произведение, которое было основано на реальных событиях. Речь идет про поместье, где проживает один ученый со своей дочкой.

Овощами правит подземный король, он и его свита приходят в огород Анны и оккупируют его. Они мечтают о том, что однажды на всей Земле будут жить только человекоовощи. А началось все с того, что Анна нашла необычайное кольцо…

Цахес

Кроме вышеописанных сказок, есть и другие произведения подобного рода Эрнста Теодора Амадея Гофмана — «Крошка Цахес, по прозванию Циннобер». Жил-был один маленький уродец. Фея пожалела его.

Она решила подарить ему три волоска, имеющих волшебные свойства. Как только что-то происходит в том месте, где Цахес находится, значительное или талантливое, или кто-то подобное произносит, то все думают, что это сделал он. А если карлик сделает какую-нибудь пакость, то все думают на других. Обладая подобным даром, крошка становится среди народа гением, его вскоре назначают министром.

«Приключение в новогоднюю ночь»

Однажды в ночь как раз под Новый год один странствующий товарищ попал в Берлин, где с ним произошла некая вполне волшебная история. Он встречает в Берлине Юлию, свою возлюбленную.

Такая девушка существовала на самом деле. Гофман преподавал ей музыку и был влюблен, но родные помолвили Юлию с другим.

«История о пропавшем отражении»

Интересен факт, что вообще в произведениях автора то и дело где-нибудь проглядывает мистическое, а уж про необычное и говорить не стоит. Умело смешивая юмор и нравственное начало, чувства и эмоции, реальный и нереальный мир, Гофман добивается полного внимания своего читателя.

Этот факт можно проследить в интересном произведении «История о пропавшем отражении». Эразм Спикер очень сильно хотел посетить Италию, чего и смог добиться, однако там он встретил прекрасную девушку Джульетту. Он совершил плохой поступок, вследствие чего ему пришлось уехать домой. Рассказывая все Джульетте, он говорит, что хотел бы с ней остаться навечно. В ответ она просит его, отдать свое отражение.

Другие произведения

Надо сказать, что известные произведения Гофмана разных жанров и для разных возрастов. Например, мистическая «История привидений».

Гофман очень сильно тяготеет к мистике, что прослеживается в рассказах про вампиров, про роковую монахиню, про песочного человека, а также в серии книг под названием «Ночные этюды».

Интересна забавная сказка о повелителе блох, где речь идет про сынка богатого торговца. Ему не по душе то, чем занимается его отец, и он не собирается идти по той же дорожке. Эта жизнь не для него, и он пытается сбежать от действительности. Однако его неожиданно арестовывают, хотя он не понимает за что. Тайный советник хочет найти преступника, а виновен преступник или нет, ему неинтересно. Он точно знает — у каждого человека можно найти какое-либо прегрешение.

В большинстве произведений Эрнста Теодора Амадея Гофмана присутствует много символики, мифов и легенд. Сказки вообще трудно делить по возрастам. Вот, например, взять «Щелкунчика», этот рассказ настолько интригующий, наполнен приключениями и влюбленностью, событиями, которые происходят с Мэри, что будет достаточно интересен детям и подросткам, и даже взрослые с удовольствием его перечитывают.

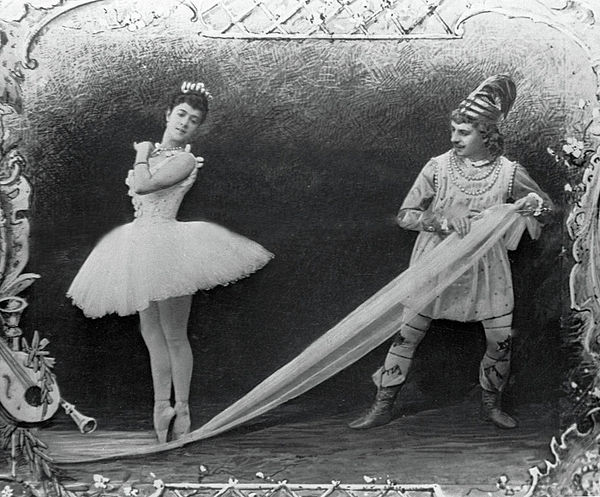

По данному произведению снимаются мультфильмы, неоднократно ставятся спектакли, балет и т. д.

На фото — первое исполнение «Щелкунчика» в Мариинском театре.

А вот другие произведения Эрнста Гофмана возможно будут немного трудноваты для восприятия ребенком. Некоторые люди приходят к этим произведениям вполне осознанно, чтобы насладиться необычайным стилем Гофмана, его причудливой смесью.

Гофмана привлекает тема, когда человек страдает безумием, совершает какое-то преступление, у него есть «темная сторона». Если у человека есть воображение, есть чувства, то он может впасть в безумие и покончить жизнь самоубийством. Для того чтобы написать рассказ «Песочный человек», Гофман изучал научные труды по болезням и клиническим составляющим. Новелла привлекла внимание исследователей, среди них был и Зигмунд Фрейд, который даже посвятил этому произведению свое эссе.

Каждый решает сам, в каком возрасте ему читать книги Гофмана. Некоторые не совсем понимают его слишком сюрреалистического языка. Однако стоит только начать читать произведение, как поневоле втягиваешься в этот смешанный мистический и безумный мир, где в реальном городе живет гном, где по улицам ходят духи, а прелестные змейки ищут своих прекрасных принцев.

|

E. T. A. Hoffmann |

|

|---|---|

Self-portrait |

|

| Born | Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann 24 January 1776 Königsberg, Kingdom of Prussia, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 25 June 1822 (aged 46) Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation |

| Pen name | E. T. A. Hoffmann |

| Occupation | Jurist, author, composer, music critic, artist |

| Period | 1809–1822 |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Signature | |

|

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (born Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann; 24 January 1776 – 25 June 1822) was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic horror, a jurist, composer, music critic and artist.[1][2][3] His stories form the basis of Jacques Offenbach’s opera The Tales of Hoffmann, in which Hoffmann appears (heavily fictionalized) as the hero. He is also the author of the novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker is based. The ballet Coppélia is based on two other stories that Hoffmann wrote, while Schumann’s Kreisleriana[4] is based on Hoffmann’s character Johannes Kreisler.

Hoffmann’s stories highly influenced 19th-century literature, and he is one of the major authors of the Romantic movement.

Life[edit]

Youth[edit]

Hoffmann’s ancestors, both maternal and paternal, were jurists.[5] His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann (1736–97), was a barrister in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), as well as a poet and amateur musician who played the viola da gamba. In 1767 he married his cousin, Lovisa Albertina Doerffer (1748–96). Ernst Theodor Wilhelm, born on 24 January 1776, was the youngest of three children, of whom the second died in infancy.

When his parents separated in 1778, his father went to Insterburg (now Chernyakhovsk) with his elder son, Johann Ludwig Hoffmann (1768–1822), while Hoffmann’s mother stayed in Königsberg with her relatives: two aunts, Johanna Sophie Doerffer (1745–1803) and Charlotte Wilhelmine Doerffer (c. 1754–79) and their brother, Otto Wilhelm Doerffer (1741–1811), who were all unmarried. The trio raised the youngster.

The household, dominated by the uncle (whom Ernst nicknamed O Weh—»Oh dear!»—in a play on his initials «O.W.»), was pietistic and uncongenial. Hoffmann was to regret his estrangement from his father. Nevertheless, he remembered his aunts with great affection, especially the younger, Charlotte, whom he nicknamed Tante Füßchen («Aunt Littlefeet»). Although she died when he was only three years old, he treasured her memory (a character in Hoffmann’s Lebensansichten des Katers Murr is named after her) and embroidered stories about her to such an extent that later biographers sometimes assumed her to be imaginary, until proof of her existence was found after World War II.[6]

Between 1781 and 1792 he attended the Lutheran school or Burgschule, where he made good progress in classics. He was taught drawing by one Saemann, and counterpoint by a Polish organist named Podbileski, who was to be the prototype of Abraham Liscot in Kater Murr.[citation needed] Ernst showed great talent for piano-playing, and busied himself with writing and drawing. The provincial setting was not, however, conducive to technical progress, and despite his many-sided talents he remained rather ignorant of both classical forms and of the new artistic ideas that were developing in Germany. He had, however, read Schiller, Goethe, Swift, Sterne, Rousseau and Jean Paul, and wrote part of a novel titled Der Geheimnisvolle.

Around 1787 he became friends with Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Younger (1775–1843), the son of a pastor, and nephew of Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Elder, the well-known writer friend of Immanuel Kant. During 1792, both attended some of Kant’s lectures at the University of Königsberg. Their friendship, although often tested by an increasing social difference, was to be lifelong.

In 1794, Hoffmann became enamored of Dora Hatt, a married woman to whom he had given music lessons. She was ten years older, and gave birth to her sixth child in 1795.[7] In February 1796, her family protested against his attentions and, with his hesitant consent, asked another of his uncles to arrange employment for him in Glogau (Głogów), Prussian Silesia.[8]

The provinces[edit]

From 1796, Hoffmann obtained employment as a clerk for his uncle, Johann Ludwig Doerffer, who lived in Glogau with his daughter Minna. After passing further examinations he visited Dresden, where he was amazed by the paintings in the gallery, particularly those of Correggio and Raphael. During the summer of 1798, his uncle was promoted to a court in Berlin, and the three of them moved there in August—Hoffmann’s first residence in a large city. It was there that Hoffmann first attempted to promote himself as a composer, writing an operetta called Die Maske and sending a copy to Queen Luise of Prussia. The official reply advised to him to write to the director of the Royal Theatre, a man named Iffland. By the time the latter responded, Hoffmann had passed his third round of examinations and had already left for Posen (Poznań) in South Prussia in the company of his old friend Hippel, with a brief stop in Dresden to show him the gallery.

From June 1800 to 1803, he worked in Prussian provinces in the area of Greater Poland and Masovia. This was the first time he had lived without supervision by members of his family, and he started to become «what school principals, parsons, uncles, and aunts call dissolute.»[9]

His first job, at Posen, was endangered after Carnival on Shrove Tuesday 1802, when caricatures of military officers were distributed at a ball. It was immediately deduced who had drawn them, and complaints were made to authorities in Berlin, who were reluctant to punish the promising young official. The problem was solved by «promoting» Hoffmann to Płock in New East Prussia, the former capital of Poland (1079–1138), where administrative offices were relocated from Thorn (Toruń). He visited the place to arrange lodging, before returning to Posen where he married Mischa (Maria or Marianna Thekla Michalina Rorer, whose Polish surname was Trzcińska). They moved to Płock in August 1802.

Hoffmann despaired because of his exile, and drew caricatures of himself drowning in mud alongside ragged villagers. He did make use, however, of his isolation, by writing and composing. He started a diary on 1 October 1803. An essay on the theatre was published in Kotzebue’s periodical, Die Freimüthige, and he entered a competition in the same magazine to write a play. Hoffmann’s was called Der Preis («The Prize»), and was itself about a competition to write a play. There were fourteen entries, but none was judged worthy of the award: 100 Friedrichs d’or. Nevertheless, his entry was singled out for praise.[10] This was one of the few good times of a sad period of his life, which saw the deaths of his uncle J. L. Hoffmann in Berlin, his Aunt Sophie, and Dora Hatt in Königsberg.

At the beginning of 1804, he obtained a post at Warsaw.[11] On his way there, he passed through his hometown and met one of Dora Hatt’s daughters. He was never to return to Königsberg.

Warsaw[edit]

Hoffmann assimilated well with Polish society; the years spent in Prussian Poland he recognized as the happiest of his life. In Warsaw he found the same atmosphere he had enjoyed in Berlin, renewing his friendship with Zacharias Werner, and meeting his future biographer, a neighbour and fellow jurist called Julius Eduard Itzig (who changed his name to Hitzig after his baptism). Itzig had been a member of the Berlin literary group called the Nordstern, or «North Star», and he gave Hoffmann the works of Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Carlo Gozzi and Calderón. These relatively late introductions marked his work profoundly.

He moved in the circles of August Wilhelm Schlegel, Adelbert von Chamisso, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Rahel Levin and David Ferdinand Koreff.

But Hoffmann’s fortunate position was not to last: on 28 November 1806, during the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops captured Warsaw, and the Prussian bureaucrats lost their jobs. They divided the contents of the treasury between them and fled. In January 1807, Hoffmann’s wife and two-year-old daughter Cäcilia returned to Posen, while he pondered whether to move to Vienna or go back to Berlin. A delay of six months was caused by severe illness. Eventually the French authorities demanded that all former officials swear allegiance or leave the country. As they refused to grant Hoffmann a passport to Vienna, he was forced to return to Berlin.

He visited his family in Posen before arriving in Berlin on 18 June 1807, hoping to further his career there as an artist and writer.

Berlin and Bamberg[edit]

The next fifteen months were some of the worst in Hoffmann’s life.

The city of Berlin was also occupied by Napoleon’s troops. Obtaining only meagre allowances, he had frequent recourse to his friends, constantly borrowing money and still going hungry for days at a time; he learned that his daughter had died. Nevertheless, he managed to compose his Six Canticles for a cappella choir: one of his best compositions, which he would later attribute to Kreisler in Lebensansichten des Katers Murr.

Hoffmann’s portrait of Kapellmeister Kreisler

On 1 September 1808 he arrived with his wife in Bamberg, where he began a job as theatre manager. The director, Count Soden, left almost immediately for Würzburg, leaving a man named Heinrich Cuno in charge. Hoffmann was unable to improve standards of performance, and his efforts caused intrigues against him which resulted in him losing his job to Cuno. He began work as music critic for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, a newspaper in Leipzig, and his articles on Beethoven were especially well received, and highly regarded by the composer himself. It was in its pages that the «Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler» character made his first appearance.

Hoffmann’s breakthrough came in 1809, with the publication of Ritter Gluck, a story about a man who meets, or believes he has met, the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–87) more than twenty years after the latter’s death. The theme alludes to the work of Jean Paul, who invented the term Doppelgänger the previous decade, and continued to exact a powerful influence over Hoffmann, becoming one of his earliest admirers. With this publication, Hoffmann began to use the pseudonym E. T. A. Hoffmann, telling people that the «A» stood for Amadeus, in homage to the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91). However, he continued to use Wilhelm in official documents throughout his life, and the initials E. T. W. also appear on his gravestone.

The next year, he was employed at the Bamberg Theatre as stagehand, decorator, and playwright, while also giving private music lessons.

He became so enamored of a young singing student, Julia Marc, that his feelings were obvious whenever they were together, and Julia’s mother quickly found her a more suitable match. When Joseph Seconda offered Hoffmann a position as musical director for his opera company (then performing in Dresden), he accepted, leaving on 21 April 1813.

Dresden and Leipzig[edit]

Prussia had declared war against France on 16 March during the War of the Sixth Coalition, and their journey was fraught with difficulties. They arrived on the 25th, only to find that Seconda was in Leipzig; on the 26th, they sent a letter pleading for temporary funds. That same day Hoffmann was surprised to meet Hippel, whom he had not seen for nine years.

The situation deteriorated, and in early May Hoffmann tried in vain to find transport to Leipzig. On 8 May, the bridges were destroyed, and his family were marooned in the city. During the day, Hoffmann would roam, watching the fighting with curiosity. Finally, on 20 May, they left for Leipzig, only to be involved in an accident which killed one of the passengers in their coach and injured his wife.

They arrived on 23 May, and Hoffmann started work with Seconda’s orchestra, which he found to be of the best quality. On 4 June an armistice began, which allowed the company to return to Dresden. But on 22 August, after the end of the armistice, the family was forced to relocate from their pleasant house in the suburbs into the town, and during the next few days the Battle of Dresden raged. The city was bombarded; many people were killed by bombs directly in front of him. After the main battle was over, he visited the gory battlefield. His account can be found in Vision auf dem Schlachtfeld bei Dresden. After a long period of continued disturbance, the town surrendered on 11 November, and on 9 December the company travelled to Leipzig.

On 25 February, Hoffmann quarrelled with Seconda, and the next day he was given notice of twelve weeks. When asked to accompany them on their journey to Dresden in April, he refused, and they left without him. But during July his friend Hippel visited, and soon he found himself being guided back into his old career as a jurist.

Berlin[edit]

Grave of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated, the inscription reads: E. T. W. Hoffmann, born on 24 January 1776, in Königsberg, died on 25 June 1822, in Berlin, Councillor of the Court of Justice, excellent in his office, as a poet, as a musician, as a painter, dedicated by his friends.

At the end of September 1814, in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat, Hoffmann returned to Berlin and succeeded in regaining a job at the Kammergericht, the chamber court. His opera Undine was performed by the Berlin Theatre. Its successful run came to an end only after a fire on the night of the 25th performance. Magazines clamoured for his contributions, and after a while his standards started to decline. Nevertheless, many masterpieces date from this time.

During the period from 1819, Hoffmann was involved with legal disputes, while fighting ill health. Alcohol abuse and syphilis eventually caused weakening of his limbs during 1821, and paralysis from the beginning of 1822. His last works were dictated to his wife or to a secretary.

Prince Metternich’s anti-liberal programs began to put Hoffmann in situations that tested his conscience. Thousands of people were accused of treason for having certain political opinions,

and university professors were monitored during their lectures.

King Frederick William III of Prussia appointed an Immediate Commission for the investigation of political dissidence; when he found its observance of the rule of law too frustrating, he established a Ministerial Commission to interfere with its processes. The latter was greatly influenced by Commissioner Kamptz. During the trial of «Turnvater» Jahn, the founder of the gymnastics association movement, Hoffmann found himself annoying Kamptz, and became a political target. When Hoffmann caricatured Kamptz in a story (Meister Floh), Kamptz began legal proceedings. These ended when Hoffmann’s illness was found to be life-threatening. The King asked for a reprimand only, but no action was ever taken. Eventually Meister Floh was published with the offending passages removed.

Hoffmann died of syphilis in Berlin on 25 June 1822 at the age of 46. His grave is preserved in the Protestant Friedhof III der Jerusalems- und Neuen Kirchengemeinde (Cemetery No. III of the congregations of Jerusalem Church and New Church) in Berlin-Kreuzberg, south of Hallesches Tor at the underground station Mehringdamm.

Works[edit]

Literary[edit]

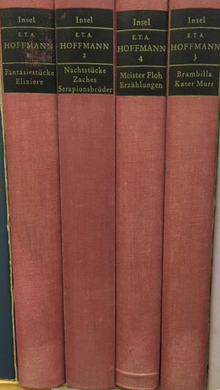

Four volume set of Hoffmann’s writings

- Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier (collection of previously published stories, 1814)[12]

- «Ritter Gluck», «Kreisleriana», «Don Juan», «Nachricht von den neuesten Schicksalen des Hundes Berganza»

- «Der Magnetiseur», «Der goldne Topf» (revised in 1819), «Die Abenteuer der Silvesternacht»

- Die Elixiere des Teufels (1815)

- Nachtstücke (1817)

- «Der Sandmann», «Das Gelübde», «Ignaz Denner», «Die Jesuiterkirche in G.»

- «Das Majorat», «Das öde Haus», «Das Sanctus», «Das steinerne Herz»

- Seltsame Leiden eines Theater-Direktors (1819)

- Little Zaches (1819)

- Die Serapionsbrüder (1819)

- «Der Einsiedler Serapion», «Rat Krespel», «Die Fermate», «Der Dichter und der Komponist»

- «Ein Fragment aus dem Leben dreier Freunde», «Der Artushof», «Die Bergwerke zu Falun», «Nußknacker und Mausekönig» (1816)

- «Der Kampf der Sänger», «Eine Spukgeschichte», «Die Automate», «Doge und Dogaresse»

- «Alte und neue Kirchenmusik», «Meister Martin der Küfner und seine Gesellen», «Das fremde Kind»

- «Nachricht aus dem Leben eines bekannten Mannes», «Die Brautwahl», «Der unheimliche Gast»

- «Das Fräulein von Scuderi», «Spielerglück» (1819), «Der Baron von B.»

- «Signor Formica», «Zacharias Werner», «Erscheinungen»

- «Der Zusammenhang der Dinge», «Vampirismus», «Die ästhetische Teegesellschaft», «Die Königsbraut»

- Prinzessin Brambilla (1820)

- Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1820)

- «Die Irrungen» (1820)

- «Die Geheimnisse» (1821)

- «Die Doppeltgänger» (1821)

- Meister Floh (1822)

- «Des Vetters Eckfenster» (1822)

- Letzte Erzählungen (1825)

Musical[edit]

Vocal music[edit]

- Messa d-moll (1805)

- Trois Canzonettes à 2 et à 3 voix (1807)

- 6 Canzoni per 4 voci alla capella (1808)

- Miserere b-moll (1809)

- In des Irtisch weiße Fluten (Kotzebue), Lied (1811)

- Recitativo ed Aria „Prendi l’acciar ti rendo» (1812)

- Tre Canzonette italiane (1812); 6 Duettini italiani (1812)

- Nachtgesang, Türkische Musik, Jägerlied, Katzburschenlied für Männerchor (1819–21)

Works for stage[edit]

- Die Maske (libretto by Hoffmann), Singspiel (1799)

- Die lustigen Musikanten (libretto: Clemens Brentano), Singspiel (1804)

- Incidental music to Zacharias Werner’s tragedy Das Kreuz an der Ostsee (1805)

- Liebe und Eifersucht (libretto by Hoffmann after Calderón, translated by August Wilhelm Schlegel) (1807)

- Arlequin, ballet (1808)

- Der Trank der Unsterblichkeit (libretto: Julius von Soden), romantic opera (1808)

- Wiedersehn! (libretto by Hoffmann), prologue (1809)

- Dirna (libretto: Julius von Soden), melodrama (1809)

- Incidental music to Julius von Soden’s drama Julius Sabinus (1810)

- Saul, König von Israel (libretto: Joseph von Seyfried), melodrama (1811)

- Aurora (libretto: Franz von Holbein), heroic opera (1812)

- Undine (libretto: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué), Zauberoper (1816)

- Der Liebhaber nach dem Tode (unfinished)

Instrumental[edit]

- Rondo für Klavier (1794/95)

- Ouvertura. Musica per la chiesa d-moll (1801)

- Klaviersonaten: A-Dur, f-moll, F-Dur, f-moll, cis-moll (1805–1808)

- Große Fantasie für Klavier (1806)

- Sinfonie Es-Dur (1806)

- Harfenquintett c-moll (1807)

- Grand Trio E-Dur (1809)

- Walzer zum Karolinentag (1812)

- Teutschlands Triumph in der Schlacht bei Leipzig, (by «Arnulph Vollweiler», 1814; lost)

- Serapions-Walzer (1818–1821)

Assessment[edit]

Statue of «E. T. A. Hoffmann and his cat» in Bamberg

Hoffmann is one of the best-known representatives of German Romanticism, and a pioneer of the fantasy genre, with a taste for the macabre combined with realism that influenced such authors as Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), Nikolai Gogol[13][14] (1809–1852), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), George MacDonald (1824–1905),[15] Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), Vernon Lee (1856–1935),[16] Franz Kafka (1883–1924) and Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980). Hoffmann’s story Das Fräulein von Scuderi is sometimes cited as the first detective story and a direct influence on Poe’s «The Murders in the Rue Morgue»;[17] Characters from it also appear in the opera Cardillac by Paul Hindemith.

The twentieth-century Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin characterised Hoffmann’s works as Menippea, essentially satirical and self-parodying in form, thus including him in a tradition that includes Cervantes, Diderot and Voltaire.

Robert Schumann’s piano suite Kreisleriana (1838) takes its title from one of Hoffmann’s books (and according to Charles Rosen’s The Romantic Generation, is possibly also inspired by «The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr», in which Kreisler appears).[4] Jacques Offenbach’s masterwork, the opera Les contes d’Hoffmann («The Tales of Hoffmann», 1881), is based on the stories, principally «Der Sandmann» («The Sandman», 1816), «Rat Krespel» («Councillor Krespel», 1818), and «Das verlorene Spiegelbild» («The Lost Reflection») from Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht (The Adventures of New Year’s Eve, 1814). Klein Zaches genannt Zinnober (Little Zaches called Cinnabar, 1819) inspired an aria as well as the operetta Le Roi Carotte, 1872). Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker (1892) is based on «The Nutcracker and the Mouse King», and the ballet Coppélia, with music by Delibes, is based on two eerie Hoffmann stories.

Hoffmann also influenced 19th-century musical opinion directly through his music criticism. His reviews of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) and other important works set new literary standards for writing about music, and encouraged later writers to consider music as «the most Romantic of all the arts.»[18] Hoffmann’s reviews were first collected for modern readers by Friedrich Schnapp, ed., in E.T.A. Hoffmann: Schriften zur Musik; Nachlese (1963) and have been made available in an English translation in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Writings on Music, Collected in a Single Volume (2004).

Hoffmann’s drawing of himself, riding on Tomcat Murr and fighting «Prussian bureaucracy»

Hoffmann strove for artistic polymathy. He created far more in his works than mere political commentary achieved through satire. His masterpiece novel Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr, 1819–1821) deals with such issues as the aesthetic status of true artistry and the modes of self-transcendence that accompany any genuine endeavour to create. Hoffmann’s portrayal of the character Kreisler (a genius musician) is wittily counterpointed with the character of the tomcat Murr – a virtuoso illustration of artistic pretentiousness that many of Hoffmann’s contemporaries found offensive and subversive of Romantic ideals.

Hoffmann’s literature indicates the failings of many so-called artists to differentiate between the superficial and the authentic aspects of such Romantic ideals. The self-conscious effort to impress must, according to Hoffmann, be divorced from the self-aware effort to create. This essential duality in Kater Murr is conveyed structurally through a discursive ‘splicing together’ of two biographical narratives.

Science fiction[edit]

While disagreeing with E. F. Bleiler’s claim that Hoffmann was «one of the two or three greatest writers of fantasy», Algis Budrys of Galaxy Science Fiction said that he «did lay down the groundwork for some of our most enduring themes».[19]

Historian Martin Willis argues that Hoffmann’s impact on science fiction has been overlooked, saying «his work reveals a writer dynamically involved in the important scientific debates of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.» Willis points out that Hoffmann’s work is contemporary with Frankenstein (1818) and with «the heated debates and the relationship between the new empirical science and the older forms of natural philosophy that held sway throughout the eighteenth century.» His «interest in the machine culture of his time is well represented in his short stories, of which the critically renowned The Sandman (1816) and Automata (1814) are the best examples. …Hoffmann’s work makes a considerable contribution to our understanding of the emergence of scientific knowledge in the early years of the nineteenth century and to the conflict between science and magic, centred mainly on the ‘truths’ available to the advocates of either practice. …Hoffmann’s balancing of mesmerism, mechanics, and magic reflects the difficulty in categorizing scientific knowledge in the early nineteenth century.»[20]

In popular culture[edit]

- Robertson Davies invokes Hoffmann as a character (with the pet name of ‘ETAH’) trapped in Limbo, in his novel The Lyre of Orpheus (1988).

- Alexandre Dumas, père translated The Nutcracker into French, which aided in making the tale popular and widespread.

- The exotic and supernatural elements in the storyline of Ingmar Bergman’s 1982 film Fanny and Alexander derive largely from the stories of Hoffmann.[21]

- Freud gives an extensive psychoanalytic analysis of Hoffmann’s «The Sandman» in his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche.[citation needed]

- Coppelius is a German classical metal band whose name is taken from a character in Hoffmann’s «The Sandman». The band’s 2010 album Zinnober includes a track titled «Klein Zaches».[22][citation needed]

- The Russian show Puppets was cancelled by government officials after an episode in which Vladimir Putin was portrayed as Hoffmann’s Klein Zaches.[23][1][24]

See also[edit]

- The Tales of Hoffmann for Offenbach’s opera.

- The Tales of Hoffmann for the film

- Gofmaniada, a Russian puppet-animated feature film about Hoffmann and several of his stories.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Penrith Goff, «E.T.A. Hoffmann» in E. F. Bleiler, Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror. New York: Scribner’s, 1985. pp. 111–120. ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ^ Mike Ashley, «Hoffmann, E(rnst) T(heodor) A(madeus) «, in St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost, and Gothic Writers, ed. David Pringle. Detroit: St. James Press/Gale, 1998. ISBN 9781558622067 (pp. 668-69).

- ^ «Ludwig Tieck, Heinrich von Kleist, and E. T. A. Hoffmann also profoundly influenced the development of European Gothic horror in the nineteenth century….» Heide Crawford, The Origins of the Literary Vampire. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2016. ISBN 9781442266742 (p. xiii).

- ^ a b Schumann, Robert (2004). Herttrich, Ernst (ed.). Kreisleriana (PDF) (in German, English, and French). G. Henle Verlag. pp. III.

- ^ Jaffé 1978, p. 13.

- ^ Friedrich Schnapp. «Hoffmanns Verwandte aus der Familie Doerffer in Königsberger Kirchenbüchern der Jahre 1740–1811.» Mitteilungen der E. T. A. Hoffmann-Gesellschaft. 23 (1977), 1–11.

- ^ Zipes, Jack (2007) [1816]. «The ‘Merry’ Dance of the Nutcracker: Discovering the World through Fairy Tales». Nutcracker & Mouse King & The Tale of the Nutcracker. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0143104834. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

He began writing novels and musical compositions as a young man and had his first love affair in 1794 with Cora (Dora) Hatt, a woman ten years older

- ^ Rüdiger Safranski. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Das Leben eines skeptischen Phantasten. Carl Hanser, Munich, 1984. ISBN 3-446-13822-6

Gerhard R. Kaiser. E. T. A. Hoffmann. J. B. Metzlersche, Stuttgart, 1988. ISBN 3-476-10243-2 - ^ Hoffmann, E. T. A. (1977). Sahlin, Johanna C. (ed.). Selected Letters of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated by Sahlin, Johanna C. University of Chicago Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-226-34790-7.

- ^ Die Freimüthige, 11 February 1804. Volume II, no. 6, pages xxi–xxiv.

- ^ Jaffé 1978, p. 15.

- ^ «Fantasy pieces in the manner of Jacques Callot»

- ^ Krys Svitlana, «Intertextual Parallels Between Gogol’ and Hoffmann: A Case Study of Vij and The Devil’s Elixirs.» Canadian-American Slavic Studies (CASS) 47.1 (2013): 1-20. (20 pages)

- ^ Krys Svitlana, «Allusions to Hoffmann in Gogol’s Ukrainian Horror Stories from the Dikan’ka Collection.» Canadian Slavonic Papers: Special Issue, devoted to the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol’s birth (1809–1852) 51.2-3 (June–September 2009): 243-266. (23 pages)

- ^ Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife London: Allen and Unwin, 1924 (p. 297-8).

- ^ «Another major influence for Lee is unmistakably E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann…» Christa Zorn, Vernon Lee : aesthetics, history, and the Victorian female intellectual. Athens : Ohio University Press, 2003. ISBN 0821414976 (p. 142).

- ^ The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker, Continuum, 2004, page 507

- ^ See also Fausto Cercignani, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Italien und die romantische Auffassung der Musik, in S. M. Moraldo (ed.), Das Land der Sehnsucht. E. T. A. Hoffmann und Italien, Heidelberg, Winter, 2002, S. 191–201.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (July 1968). «Galaxy Bookshelf». Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 161–167.

- ^ Martin Willis (2006). Mesmerists, Monsters, and Machines: Science Fiction and the Cultures of Science in the Nineteenth Century. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. pp. 29–30.

- ^ «Fanny and Alexander». www.ingmarbergman.se. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Review of Zinnober, http://www.ice-vajal.com/c/CD/coppelius.htm

- ^ «New Cartoon Show Puts Putin Among Men» http://www.ekaterinburg.com/news/print/news_id-316222.html

- ^ Loiko, Sergei (20 February 2012). «Vladimir Putin is spoofed on the Internet». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

Sources[edit]

- Jaffé, Aniela (1978). Bilder und Symbole aus E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Märchen «Der Goldne Topf» (in German) (2nd ed.). Gerstenberg Verlag Hildesheim.

External links[edit]

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about E. T. A. Hoffmann at Internet Archive

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hoffmann’s Life and Opinions of the Tom Cat Murr

- Free scores by E. T. A. Hoffmann in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- T. A. Hoffmann’s Fairy Tales

- Compositions of E. T. A. Hoffmann in the digital collection of the Bamberg State Library

- E. T. A. Hoffmann entry in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy

- E. T. A. Hoffmann at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Extensively cross-indexed bibliography of Hoffmann’s works

|

E. T. A. Hoffmann |

|

|---|---|

Self-portrait |

|

| Born | Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann 24 January 1776 Königsberg, Kingdom of Prussia, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 25 June 1822 (aged 46) Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation |

| Pen name | E. T. A. Hoffmann |

| Occupation | Jurist, author, composer, music critic, artist |

| Period | 1809–1822 |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Signature | |

|

Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (born Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann; 24 January 1776 – 25 June 1822) was a German Romantic author of fantasy and Gothic horror, a jurist, composer, music critic and artist.[1][2][3] His stories form the basis of Jacques Offenbach’s opera The Tales of Hoffmann, in which Hoffmann appears (heavily fictionalized) as the hero. He is also the author of the novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, on which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker is based. The ballet Coppélia is based on two other stories that Hoffmann wrote, while Schumann’s Kreisleriana[4] is based on Hoffmann’s character Johannes Kreisler.

Hoffmann’s stories highly influenced 19th-century literature, and he is one of the major authors of the Romantic movement.

Life[edit]

Youth[edit]

Hoffmann’s ancestors, both maternal and paternal, were jurists.[5] His father, Christoph Ludwig Hoffmann (1736–97), was a barrister in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), as well as a poet and amateur musician who played the viola da gamba. In 1767 he married his cousin, Lovisa Albertina Doerffer (1748–96). Ernst Theodor Wilhelm, born on 24 January 1776, was the youngest of three children, of whom the second died in infancy.

When his parents separated in 1778, his father went to Insterburg (now Chernyakhovsk) with his elder son, Johann Ludwig Hoffmann (1768–1822), while Hoffmann’s mother stayed in Königsberg with her relatives: two aunts, Johanna Sophie Doerffer (1745–1803) and Charlotte Wilhelmine Doerffer (c. 1754–79) and their brother, Otto Wilhelm Doerffer (1741–1811), who were all unmarried. The trio raised the youngster.

The household, dominated by the uncle (whom Ernst nicknamed O Weh—»Oh dear!»—in a play on his initials «O.W.»), was pietistic and uncongenial. Hoffmann was to regret his estrangement from his father. Nevertheless, he remembered his aunts with great affection, especially the younger, Charlotte, whom he nicknamed Tante Füßchen («Aunt Littlefeet»). Although she died when he was only three years old, he treasured her memory (a character in Hoffmann’s Lebensansichten des Katers Murr is named after her) and embroidered stories about her to such an extent that later biographers sometimes assumed her to be imaginary, until proof of her existence was found after World War II.[6]

Between 1781 and 1792 he attended the Lutheran school or Burgschule, where he made good progress in classics. He was taught drawing by one Saemann, and counterpoint by a Polish organist named Podbileski, who was to be the prototype of Abraham Liscot in Kater Murr.[citation needed] Ernst showed great talent for piano-playing, and busied himself with writing and drawing. The provincial setting was not, however, conducive to technical progress, and despite his many-sided talents he remained rather ignorant of both classical forms and of the new artistic ideas that were developing in Germany. He had, however, read Schiller, Goethe, Swift, Sterne, Rousseau and Jean Paul, and wrote part of a novel titled Der Geheimnisvolle.

Around 1787 he became friends with Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Younger (1775–1843), the son of a pastor, and nephew of Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Elder, the well-known writer friend of Immanuel Kant. During 1792, both attended some of Kant’s lectures at the University of Königsberg. Their friendship, although often tested by an increasing social difference, was to be lifelong.

In 1794, Hoffmann became enamored of Dora Hatt, a married woman to whom he had given music lessons. She was ten years older, and gave birth to her sixth child in 1795.[7] In February 1796, her family protested against his attentions and, with his hesitant consent, asked another of his uncles to arrange employment for him in Glogau (Głogów), Prussian Silesia.[8]

The provinces[edit]

From 1796, Hoffmann obtained employment as a clerk for his uncle, Johann Ludwig Doerffer, who lived in Glogau with his daughter Minna. After passing further examinations he visited Dresden, where he was amazed by the paintings in the gallery, particularly those of Correggio and Raphael. During the summer of 1798, his uncle was promoted to a court in Berlin, and the three of them moved there in August—Hoffmann’s first residence in a large city. It was there that Hoffmann first attempted to promote himself as a composer, writing an operetta called Die Maske and sending a copy to Queen Luise of Prussia. The official reply advised to him to write to the director of the Royal Theatre, a man named Iffland. By the time the latter responded, Hoffmann had passed his third round of examinations and had already left for Posen (Poznań) in South Prussia in the company of his old friend Hippel, with a brief stop in Dresden to show him the gallery.

From June 1800 to 1803, he worked in Prussian provinces in the area of Greater Poland and Masovia. This was the first time he had lived without supervision by members of his family, and he started to become «what school principals, parsons, uncles, and aunts call dissolute.»[9]

His first job, at Posen, was endangered after Carnival on Shrove Tuesday 1802, when caricatures of military officers were distributed at a ball. It was immediately deduced who had drawn them, and complaints were made to authorities in Berlin, who were reluctant to punish the promising young official. The problem was solved by «promoting» Hoffmann to Płock in New East Prussia, the former capital of Poland (1079–1138), where administrative offices were relocated from Thorn (Toruń). He visited the place to arrange lodging, before returning to Posen where he married Mischa (Maria or Marianna Thekla Michalina Rorer, whose Polish surname was Trzcińska). They moved to Płock in August 1802.

Hoffmann despaired because of his exile, and drew caricatures of himself drowning in mud alongside ragged villagers. He did make use, however, of his isolation, by writing and composing. He started a diary on 1 October 1803. An essay on the theatre was published in Kotzebue’s periodical, Die Freimüthige, and he entered a competition in the same magazine to write a play. Hoffmann’s was called Der Preis («The Prize»), and was itself about a competition to write a play. There were fourteen entries, but none was judged worthy of the award: 100 Friedrichs d’or. Nevertheless, his entry was singled out for praise.[10] This was one of the few good times of a sad period of his life, which saw the deaths of his uncle J. L. Hoffmann in Berlin, his Aunt Sophie, and Dora Hatt in Königsberg.

At the beginning of 1804, he obtained a post at Warsaw.[11] On his way there, he passed through his hometown and met one of Dora Hatt’s daughters. He was never to return to Königsberg.

Warsaw[edit]

Hoffmann assimilated well with Polish society; the years spent in Prussian Poland he recognized as the happiest of his life. In Warsaw he found the same atmosphere he had enjoyed in Berlin, renewing his friendship with Zacharias Werner, and meeting his future biographer, a neighbour and fellow jurist called Julius Eduard Itzig (who changed his name to Hitzig after his baptism). Itzig had been a member of the Berlin literary group called the Nordstern, or «North Star», and he gave Hoffmann the works of Novalis, Ludwig Tieck, Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano, Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert, Carlo Gozzi and Calderón. These relatively late introductions marked his work profoundly.

He moved in the circles of August Wilhelm Schlegel, Adelbert von Chamisso, Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Rahel Levin and David Ferdinand Koreff.

But Hoffmann’s fortunate position was not to last: on 28 November 1806, during the War of the Fourth Coalition, Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops captured Warsaw, and the Prussian bureaucrats lost their jobs. They divided the contents of the treasury between them and fled. In January 1807, Hoffmann’s wife and two-year-old daughter Cäcilia returned to Posen, while he pondered whether to move to Vienna or go back to Berlin. A delay of six months was caused by severe illness. Eventually the French authorities demanded that all former officials swear allegiance or leave the country. As they refused to grant Hoffmann a passport to Vienna, he was forced to return to Berlin.

He visited his family in Posen before arriving in Berlin on 18 June 1807, hoping to further his career there as an artist and writer.

Berlin and Bamberg[edit]

The next fifteen months were some of the worst in Hoffmann’s life.

The city of Berlin was also occupied by Napoleon’s troops. Obtaining only meagre allowances, he had frequent recourse to his friends, constantly borrowing money and still going hungry for days at a time; he learned that his daughter had died. Nevertheless, he managed to compose his Six Canticles for a cappella choir: one of his best compositions, which he would later attribute to Kreisler in Lebensansichten des Katers Murr.

Hoffmann’s portrait of Kapellmeister Kreisler

On 1 September 1808 he arrived with his wife in Bamberg, where he began a job as theatre manager. The director, Count Soden, left almost immediately for Würzburg, leaving a man named Heinrich Cuno in charge. Hoffmann was unable to improve standards of performance, and his efforts caused intrigues against him which resulted in him losing his job to Cuno. He began work as music critic for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, a newspaper in Leipzig, and his articles on Beethoven were especially well received, and highly regarded by the composer himself. It was in its pages that the «Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler» character made his first appearance.

Hoffmann’s breakthrough came in 1809, with the publication of Ritter Gluck, a story about a man who meets, or believes he has met, the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–87) more than twenty years after the latter’s death. The theme alludes to the work of Jean Paul, who invented the term Doppelgänger the previous decade, and continued to exact a powerful influence over Hoffmann, becoming one of his earliest admirers. With this publication, Hoffmann began to use the pseudonym E. T. A. Hoffmann, telling people that the «A» stood for Amadeus, in homage to the composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91). However, he continued to use Wilhelm in official documents throughout his life, and the initials E. T. W. also appear on his gravestone.

The next year, he was employed at the Bamberg Theatre as stagehand, decorator, and playwright, while also giving private music lessons.

He became so enamored of a young singing student, Julia Marc, that his feelings were obvious whenever they were together, and Julia’s mother quickly found her a more suitable match. When Joseph Seconda offered Hoffmann a position as musical director for his opera company (then performing in Dresden), he accepted, leaving on 21 April 1813.

Dresden and Leipzig[edit]

Prussia had declared war against France on 16 March during the War of the Sixth Coalition, and their journey was fraught with difficulties. They arrived on the 25th, only to find that Seconda was in Leipzig; on the 26th, they sent a letter pleading for temporary funds. That same day Hoffmann was surprised to meet Hippel, whom he had not seen for nine years.

The situation deteriorated, and in early May Hoffmann tried in vain to find transport to Leipzig. On 8 May, the bridges were destroyed, and his family were marooned in the city. During the day, Hoffmann would roam, watching the fighting with curiosity. Finally, on 20 May, they left for Leipzig, only to be involved in an accident which killed one of the passengers in their coach and injured his wife.

They arrived on 23 May, and Hoffmann started work with Seconda’s orchestra, which he found to be of the best quality. On 4 June an armistice began, which allowed the company to return to Dresden. But on 22 August, after the end of the armistice, the family was forced to relocate from their pleasant house in the suburbs into the town, and during the next few days the Battle of Dresden raged. The city was bombarded; many people were killed by bombs directly in front of him. After the main battle was over, he visited the gory battlefield. His account can be found in Vision auf dem Schlachtfeld bei Dresden. After a long period of continued disturbance, the town surrendered on 11 November, and on 9 December the company travelled to Leipzig.

On 25 February, Hoffmann quarrelled with Seconda, and the next day he was given notice of twelve weeks. When asked to accompany them on their journey to Dresden in April, he refused, and they left without him. But during July his friend Hippel visited, and soon he found himself being guided back into his old career as a jurist.

Berlin[edit]

Grave of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated, the inscription reads: E. T. W. Hoffmann, born on 24 January 1776, in Königsberg, died on 25 June 1822, in Berlin, Councillor of the Court of Justice, excellent in his office, as a poet, as a musician, as a painter, dedicated by his friends.

At the end of September 1814, in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat, Hoffmann returned to Berlin and succeeded in regaining a job at the Kammergericht, the chamber court. His opera Undine was performed by the Berlin Theatre. Its successful run came to an end only after a fire on the night of the 25th performance. Magazines clamoured for his contributions, and after a while his standards started to decline. Nevertheless, many masterpieces date from this time.

During the period from 1819, Hoffmann was involved with legal disputes, while fighting ill health. Alcohol abuse and syphilis eventually caused weakening of his limbs during 1821, and paralysis from the beginning of 1822. His last works were dictated to his wife or to a secretary.

Prince Metternich’s anti-liberal programs began to put Hoffmann in situations that tested his conscience. Thousands of people were accused of treason for having certain political opinions,

and university professors were monitored during their lectures.

King Frederick William III of Prussia appointed an Immediate Commission for the investigation of political dissidence; when he found its observance of the rule of law too frustrating, he established a Ministerial Commission to interfere with its processes. The latter was greatly influenced by Commissioner Kamptz. During the trial of «Turnvater» Jahn, the founder of the gymnastics association movement, Hoffmann found himself annoying Kamptz, and became a political target. When Hoffmann caricatured Kamptz in a story (Meister Floh), Kamptz began legal proceedings. These ended when Hoffmann’s illness was found to be life-threatening. The King asked for a reprimand only, but no action was ever taken. Eventually Meister Floh was published with the offending passages removed.

Hoffmann died of syphilis in Berlin on 25 June 1822 at the age of 46. His grave is preserved in the Protestant Friedhof III der Jerusalems- und Neuen Kirchengemeinde (Cemetery No. III of the congregations of Jerusalem Church and New Church) in Berlin-Kreuzberg, south of Hallesches Tor at the underground station Mehringdamm.

Works[edit]

Literary[edit]

Four volume set of Hoffmann’s writings

- Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier (collection of previously published stories, 1814)[12]

- «Ritter Gluck», «Kreisleriana», «Don Juan», «Nachricht von den neuesten Schicksalen des Hundes Berganza»

- «Der Magnetiseur», «Der goldne Topf» (revised in 1819), «Die Abenteuer der Silvesternacht»

- Die Elixiere des Teufels (1815)

- Nachtstücke (1817)

- «Der Sandmann», «Das Gelübde», «Ignaz Denner», «Die Jesuiterkirche in G.»

- «Das Majorat», «Das öde Haus», «Das Sanctus», «Das steinerne Herz»

- Seltsame Leiden eines Theater-Direktors (1819)

- Little Zaches (1819)

- Die Serapionsbrüder (1819)

- «Der Einsiedler Serapion», «Rat Krespel», «Die Fermate», «Der Dichter und der Komponist»

- «Ein Fragment aus dem Leben dreier Freunde», «Der Artushof», «Die Bergwerke zu Falun», «Nußknacker und Mausekönig» (1816)

- «Der Kampf der Sänger», «Eine Spukgeschichte», «Die Automate», «Doge und Dogaresse»

- «Alte und neue Kirchenmusik», «Meister Martin der Küfner und seine Gesellen», «Das fremde Kind»

- «Nachricht aus dem Leben eines bekannten Mannes», «Die Brautwahl», «Der unheimliche Gast»

- «Das Fräulein von Scuderi», «Spielerglück» (1819), «Der Baron von B.»

- «Signor Formica», «Zacharias Werner», «Erscheinungen»

- «Der Zusammenhang der Dinge», «Vampirismus», «Die ästhetische Teegesellschaft», «Die Königsbraut»

- Prinzessin Brambilla (1820)

- Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (1820)

- «Die Irrungen» (1820)

- «Die Geheimnisse» (1821)

- «Die Doppeltgänger» (1821)

- Meister Floh (1822)

- «Des Vetters Eckfenster» (1822)

- Letzte Erzählungen (1825)

Musical[edit]

Vocal music[edit]

- Messa d-moll (1805)

- Trois Canzonettes à 2 et à 3 voix (1807)

- 6 Canzoni per 4 voci alla capella (1808)

- Miserere b-moll (1809)

- In des Irtisch weiße Fluten (Kotzebue), Lied (1811)

- Recitativo ed Aria „Prendi l’acciar ti rendo» (1812)

- Tre Canzonette italiane (1812); 6 Duettini italiani (1812)

- Nachtgesang, Türkische Musik, Jägerlied, Katzburschenlied für Männerchor (1819–21)

Works for stage[edit]

- Die Maske (libretto by Hoffmann), Singspiel (1799)

- Die lustigen Musikanten (libretto: Clemens Brentano), Singspiel (1804)

- Incidental music to Zacharias Werner’s tragedy Das Kreuz an der Ostsee (1805)

- Liebe und Eifersucht (libretto by Hoffmann after Calderón, translated by August Wilhelm Schlegel) (1807)

- Arlequin, ballet (1808)

- Der Trank der Unsterblichkeit (libretto: Julius von Soden), romantic opera (1808)

- Wiedersehn! (libretto by Hoffmann), prologue (1809)

- Dirna (libretto: Julius von Soden), melodrama (1809)

- Incidental music to Julius von Soden’s drama Julius Sabinus (1810)

- Saul, König von Israel (libretto: Joseph von Seyfried), melodrama (1811)

- Aurora (libretto: Franz von Holbein), heroic opera (1812)

- Undine (libretto: Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué), Zauberoper (1816)

- Der Liebhaber nach dem Tode (unfinished)

Instrumental[edit]

- Rondo für Klavier (1794/95)

- Ouvertura. Musica per la chiesa d-moll (1801)

- Klaviersonaten: A-Dur, f-moll, F-Dur, f-moll, cis-moll (1805–1808)

- Große Fantasie für Klavier (1806)

- Sinfonie Es-Dur (1806)

- Harfenquintett c-moll (1807)

- Grand Trio E-Dur (1809)

- Walzer zum Karolinentag (1812)

- Teutschlands Triumph in der Schlacht bei Leipzig, (by «Arnulph Vollweiler», 1814; lost)

- Serapions-Walzer (1818–1821)

Assessment[edit]

Statue of «E. T. A. Hoffmann and his cat» in Bamberg

Hoffmann is one of the best-known representatives of German Romanticism, and a pioneer of the fantasy genre, with a taste for the macabre combined with realism that influenced such authors as Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), Nikolai Gogol[13][14] (1809–1852), Charles Dickens (1812–1870), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867), George MacDonald (1824–1905),[15] Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881), Vernon Lee (1856–1935),[16] Franz Kafka (1883–1924) and Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980). Hoffmann’s story Das Fräulein von Scuderi is sometimes cited as the first detective story and a direct influence on Poe’s «The Murders in the Rue Morgue»;[17] Characters from it also appear in the opera Cardillac by Paul Hindemith.

The twentieth-century Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin characterised Hoffmann’s works as Menippea, essentially satirical and self-parodying in form, thus including him in a tradition that includes Cervantes, Diderot and Voltaire.

Robert Schumann’s piano suite Kreisleriana (1838) takes its title from one of Hoffmann’s books (and according to Charles Rosen’s The Romantic Generation, is possibly also inspired by «The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr», in which Kreisler appears).[4] Jacques Offenbach’s masterwork, the opera Les contes d’Hoffmann («The Tales of Hoffmann», 1881), is based on the stories, principally «Der Sandmann» («The Sandman», 1816), «Rat Krespel» («Councillor Krespel», 1818), and «Das verlorene Spiegelbild» («The Lost Reflection») from Die Abenteuer der Silvester-Nacht (The Adventures of New Year’s Eve, 1814). Klein Zaches genannt Zinnober (Little Zaches called Cinnabar, 1819) inspired an aria as well as the operetta Le Roi Carotte, 1872). Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker (1892) is based on «The Nutcracker and the Mouse King», and the ballet Coppélia, with music by Delibes, is based on two eerie Hoffmann stories.

Hoffmann also influenced 19th-century musical opinion directly through his music criticism. His reviews of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) and other important works set new literary standards for writing about music, and encouraged later writers to consider music as «the most Romantic of all the arts.»[18] Hoffmann’s reviews were first collected for modern readers by Friedrich Schnapp, ed., in E.T.A. Hoffmann: Schriften zur Musik; Nachlese (1963) and have been made available in an English translation in E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Writings on Music, Collected in a Single Volume (2004).

Hoffmann’s drawing of himself, riding on Tomcat Murr and fighting «Prussian bureaucracy»

Hoffmann strove for artistic polymathy. He created far more in his works than mere political commentary achieved through satire. His masterpiece novel Lebensansichten des Katers Murr (The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr, 1819–1821) deals with such issues as the aesthetic status of true artistry and the modes of self-transcendence that accompany any genuine endeavour to create. Hoffmann’s portrayal of the character Kreisler (a genius musician) is wittily counterpointed with the character of the tomcat Murr – a virtuoso illustration of artistic pretentiousness that many of Hoffmann’s contemporaries found offensive and subversive of Romantic ideals.

Hoffmann’s literature indicates the failings of many so-called artists to differentiate between the superficial and the authentic aspects of such Romantic ideals. The self-conscious effort to impress must, according to Hoffmann, be divorced from the self-aware effort to create. This essential duality in Kater Murr is conveyed structurally through a discursive ‘splicing together’ of two biographical narratives.

Science fiction[edit]

While disagreeing with E. F. Bleiler’s claim that Hoffmann was «one of the two or three greatest writers of fantasy», Algis Budrys of Galaxy Science Fiction said that he «did lay down the groundwork for some of our most enduring themes».[19]

Historian Martin Willis argues that Hoffmann’s impact on science fiction has been overlooked, saying «his work reveals a writer dynamically involved in the important scientific debates of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.» Willis points out that Hoffmann’s work is contemporary with Frankenstein (1818) and with «the heated debates and the relationship between the new empirical science and the older forms of natural philosophy that held sway throughout the eighteenth century.» His «interest in the machine culture of his time is well represented in his short stories, of which the critically renowned The Sandman (1816) and Automata (1814) are the best examples. …Hoffmann’s work makes a considerable contribution to our understanding of the emergence of scientific knowledge in the early years of the nineteenth century and to the conflict between science and magic, centred mainly on the ‘truths’ available to the advocates of either practice. …Hoffmann’s balancing of mesmerism, mechanics, and magic reflects the difficulty in categorizing scientific knowledge in the early nineteenth century.»[20]

In popular culture[edit]

- Robertson Davies invokes Hoffmann as a character (with the pet name of ‘ETAH’) trapped in Limbo, in his novel The Lyre of Orpheus (1988).

- Alexandre Dumas, père translated The Nutcracker into French, which aided in making the tale popular and widespread.

- The exotic and supernatural elements in the storyline of Ingmar Bergman’s 1982 film Fanny and Alexander derive largely from the stories of Hoffmann.[21]

- Freud gives an extensive psychoanalytic analysis of Hoffmann’s «The Sandman» in his 1919 essay Das Unheimliche.[citation needed]

- Coppelius is a German classical metal band whose name is taken from a character in Hoffmann’s «The Sandman». The band’s 2010 album Zinnober includes a track titled «Klein Zaches».[22][citation needed]

- The Russian show Puppets was cancelled by government officials after an episode in which Vladimir Putin was portrayed as Hoffmann’s Klein Zaches.[23][1][24]

See also[edit]

- The Tales of Hoffmann for Offenbach’s opera.

- The Tales of Hoffmann for the film

- Gofmaniada, a Russian puppet-animated feature film about Hoffmann and several of his stories.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Penrith Goff, «E.T.A. Hoffmann» in E. F. Bleiler, Supernatural Fiction Writers: Fantasy and Horror. New York: Scribner’s, 1985. pp. 111–120. ISBN 0-684-17808-7

- ^ Mike Ashley, «Hoffmann, E(rnst) T(heodor) A(madeus) «, in St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost, and Gothic Writers, ed. David Pringle. Detroit: St. James Press/Gale, 1998. ISBN 9781558622067 (pp. 668-69).

- ^ «Ludwig Tieck, Heinrich von Kleist, and E. T. A. Hoffmann also profoundly influenced the development of European Gothic horror in the nineteenth century….» Heide Crawford, The Origins of the Literary Vampire. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2016. ISBN 9781442266742 (p. xiii).

- ^ a b Schumann, Robert (2004). Herttrich, Ernst (ed.). Kreisleriana (PDF) (in German, English, and French). G. Henle Verlag. pp. III.

- ^ Jaffé 1978, p. 13.

- ^ Friedrich Schnapp. «Hoffmanns Verwandte aus der Familie Doerffer in Königsberger Kirchenbüchern der Jahre 1740–1811.» Mitteilungen der E. T. A. Hoffmann-Gesellschaft. 23 (1977), 1–11.

- ^ Zipes, Jack (2007) [1816]. «The ‘Merry’ Dance of the Nutcracker: Discovering the World through Fairy Tales». Nutcracker & Mouse King & The Tale of the Nutcracker. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0143104834. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

He began writing novels and musical compositions as a young man and had his first love affair in 1794 with Cora (Dora) Hatt, a woman ten years older

- ^ Rüdiger Safranski. E. T. A. Hoffmann: Das Leben eines skeptischen Phantasten. Carl Hanser, Munich, 1984. ISBN 3-446-13822-6

Gerhard R. Kaiser. E. T. A. Hoffmann. J. B. Metzlersche, Stuttgart, 1988. ISBN 3-476-10243-2 - ^ Hoffmann, E. T. A. (1977). Sahlin, Johanna C. (ed.). Selected Letters of E. T. A. Hoffmann. Translated by Sahlin, Johanna C. University of Chicago Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-226-34790-7.

- ^ Die Freimüthige, 11 February 1804. Volume II, no. 6, pages xxi–xxiv.

- ^ Jaffé 1978, p. 15.

- ^ «Fantasy pieces in the manner of Jacques Callot»

- ^ Krys Svitlana, «Intertextual Parallels Between Gogol’ and Hoffmann: A Case Study of Vij and The Devil’s Elixirs.» Canadian-American Slavic Studies (CASS) 47.1 (2013): 1-20. (20 pages)

- ^ Krys Svitlana, «Allusions to Hoffmann in Gogol’s Ukrainian Horror Stories from the Dikan’ka Collection.» Canadian Slavonic Papers: Special Issue, devoted to the 200th anniversary of Nikolai Gogol’s birth (1809–1852) 51.2-3 (June–September 2009): 243-266. (23 pages)

- ^ Greville MacDonald, George MacDonald and His Wife London: Allen and Unwin, 1924 (p. 297-8).

- ^ «Another major influence for Lee is unmistakably E.T.A. Hoffmann’s Der Sandmann…» Christa Zorn, Vernon Lee : aesthetics, history, and the Victorian female intellectual. Athens : Ohio University Press, 2003. ISBN 0821414976 (p. 142).

- ^ The Seven Basic Plots, Christopher Booker, Continuum, 2004, page 507

- ^ See also Fausto Cercignani, E. T. A. Hoffmann, Italien und die romantische Auffassung der Musik, in S. M. Moraldo (ed.), Das Land der Sehnsucht. E. T. A. Hoffmann und Italien, Heidelberg, Winter, 2002, S. 191–201.

- ^ Budrys, Algis (July 1968). «Galaxy Bookshelf». Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 161–167.

- ^ Martin Willis (2006). Mesmerists, Monsters, and Machines: Science Fiction and the Cultures of Science in the Nineteenth Century. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. pp. 29–30.

- ^ «Fanny and Alexander». www.ingmarbergman.se. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Review of Zinnober, http://www.ice-vajal.com/c/CD/coppelius.htm

- ^ «New Cartoon Show Puts Putin Among Men» http://www.ekaterinburg.com/news/print/news_id-316222.html

- ^ Loiko, Sergei (20 February 2012). «Vladimir Putin is spoofed on the Internet». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

Sources[edit]

- Jaffé, Aniela (1978). Bilder und Symbole aus E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Märchen «Der Goldne Topf» (in German) (2nd ed.). Gerstenberg Verlag Hildesheim.

External links[edit]

German Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about E. T. A. Hoffmann at Internet Archive

- Works by E. T. A. Hoffmann at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Hoffmann’s Life and Opinions of the Tom Cat Murr

- Free scores by E. T. A. Hoffmann in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- T. A. Hoffmann’s Fairy Tales

- Compositions of E. T. A. Hoffmann in the digital collection of the Bamberg State Library

- E. T. A. Hoffmann entry in The Encyclopedia of Fantasy

- E. T. A. Hoffmann at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Extensively cross-indexed bibliography of Hoffmann’s works

Занимательный час

«Волшебный мир сказок Э. А. Т. Гофмана»

(6 класс)

Подготовила:

библиотекарь читального зала

Детского отдела МКУК ЦБ

Е. А. Черкасова.

«Читайте! И пусть в вашей жизни не будет ни одного дня,

когда бы вы не прочли хоть одной странички из новой книги!»

К.Г. Паустовский.

«Одну минуточку, я что хотел спросить:

Легко ли Гофману три имени носить?

О, горевать и уставать за трех людей

Тому, кто Эрнст, и Теодор, и Амадей».

КУШНЕР АЛЕКСАНДР

Цель: познакомиться

с главными героями произведений Гофмана (повесть-сказка «Щелкунчик и мышиный

король», новелла «Золотой горшок», повесть-сказка «Маленький Цахес, по

прозванию Циннобер», роман «Житейские воззрения кота Мурра»). Отметить черты их

характеров, сориентироваться, где и когда происходят описываемые события.

Задачи

Образовательные:

— развивать навыки анализа прозаического сказочного

текста, обогащать представление о художественной детали;

— формировать умение пересказывать близко

к тексту, не нарушая логики, выделять связи между явлениями, формулировать

выводы и обобщать.

Развивающие:

— развивать творческое видение учащихся,

воображение, память;

— формировать умение грамотно работать с

книгой.

Воспитательные:

— подвести детей к сознанию того, как важно стремиться понять

других и если это необходимо, помочь им;

— развивать культуру общения; формировать творческую активность

школьников;

— воспитывать потребность общения друг с другом;

— продолжить формирование интереса к предмету.

Оборудование:

книги, иллюстрации, цитаты, кроссворды, картинки для разукрашивания, музыка из

балета Чайковского П.И. «Щелкунчик», портрет Э.Т.А. Гофмана, презентация,

листы с заданиями и ручки, фломастеры.

Ход урока.

1.

Организационный момент. Здравствуйте, ребята! Занимайте

свои места. Сегодня наше мероприятие посвящено жизни и творчеству Э. А. Т.

Гофмана.

2.

Вступительное слово.

Библиотекарь: Все

его книги наполнены загадочными персонажами, которые могут внезапно исчезать

или возникать ниоткуда. Его героям всегда сопутствуют необычные непонятные

сюрпризы: крохотный кавалер-шаркун, коробочка-сюрприз, из которой со звоном

выскакивает серебряная птичка, механическая кукла, которую не отличишь от живой

девушки, миниатюрный замок с золотыми башенками и зеркальными окнами.

Этот маг и волшебник не носил чёрной мантии с таинственными

знаками, а ходил в поношенном коричневом фраке и вместо волшебной палочки

использовал гусиное перо, которым записывал все свои чудесные истории,

созданные им буквально из «ничего»: из бронзовой дверной ручки с ухмыляющейся

физиономией, из щипцов для орехов, из хриплого боя старых часов.

— Ребята, знакомы ли Вы со сказками Гофмана? Какие произведения

читали? Может быть, видели известный мультик по повести-сказке «Щелкунчик

и мышиный король»? Сегодня мы познакомимся с автором этих увлекательных

историй, а также погрузимся в волшебный мир его сказок.

3.

Биография и творчество Э. А. Т. Гофмана:

Библиотекарь: Давайте, вспомним, а может,

и узнаем что-то новое из биографии автора. Для начала, прослушаем

стихотворение Александра Кушнера, в котором поэт точно подметил основные

моменты биографии Гофмана.

Гофман

Одну минуточку, я что хотел спросить:

Легко ли Гофману три имени носить?

О, горевать и уставать за трех людей

Тому, кто Эрнст, и Теодор, и Амадей.

Эрнст — только винтик, канцелярии юрист,

Он за листом в суде марает новый лист,

Не рисовать, не сочинять ему, не петь —

В бюрократической машине той скрипеть.

Скрипеть, потеть, смягчать кому-то

приговор.

Куда удачливее Эрнста Теодор.

Придя домой, превозмогая боль в плече,

Он пишет повести ночами при свече.

Он пишет повести, а сердцу все грустней.

Тогда приходит к Теодору Амадей,

Гость удивительный и самый дорогой.

Он, словно Моцарт, машет в воздухе рукой…

На Фридрихштрассе Гофман кофе пьет и ест.

«На Фридрихштрассе»,— говорит тихонько Эрнст.

«Ах нет, направо!» — умоляет Теодор.

«Идем налево,— оба слышат,— и во двор».

Играет флейта еле-еле во дворе,

Как будто школьник водит пальцем в букваре.

«Но все равно она,— вздыхает Амадей,—

Судебных записей милей и повестей».

КУШНЕР АЛЕКСАНДР

Библиотекарь: В 1776

году в городе Кёнигсберге родился Эрнст Теодор Вильгельм Гофман, теперь

известный как Эрнст Теодор Амадей Гофман. Свое имя Гофман сменил уже в

зрелом возрасте, добавив к нему, Амадей в честь Моцарта – композитора, перед

творчеством которого преклонялся. И именно это имя стало символом нового

поколения сказок от Гофмана, читать которые стали с упоением и взрослые и дети.

Родился будущий известный писатель и композитор Гофман

в семье адвоката, но отец разошелся с матерью, когда мальчик был ещё совсем

маленьким. Воспитали Эрнста его бабушка и дядя, который, кстати говоря, тоже

практиковал как юрист. Именно он воспитал в мальчике творческую личность и

обратил внимание на его склонности к музыке и рисованию, хотя и настоял на том,

чтобы Гофман получил юридическое образование и работал в юриспруденции для

обеспечения приемлемого уровня жизни. Последующую жизнь Эрнст был благодарен

ему, так как не всегда удавалось заработать на хлеб при помощи искусства, и

бывало так, что приходилось голодать.

В 1813 году Гофман получил наследство, оно хоть и было

небольшим, но всё же позволило ему стать на ноги. Как раз в то время, он уже

получил работу в Берлине, которая пришлась как нельзя, кстати, ведь оставалось

время для посвящения себя искусству. Именно тогда Гофман впервые задумался над

сказочными идеями, витавшими в его голове.

Ненависть ко всяким светским встречам и вечеринкам

привели к тому, что Гофман стал пить в одиночестве и по ночам писать свои

первые произведения, которые были настолько ужасны, что приводили в отчаяние

его самого. Однако уже тогда он написал несколько произведений, достойных

внимания, но и те не были признаны, так как содержали недвусмысленную сатиру и

в то время не приходились по вкусу критикам. Гораздо более популярным писатель

стал за пределами своей родины. К огромному сожалению, Гофман окончательно

извел свой организм нездоровым образом жизни и скончался в 46 лет, а сказки

Гофмана, как он и мечтал, стали бессмертны.

Немногие писатели удостаивались такого внимания к

собственной жизни, но на основе биографии Гофмана и его произведений были

созданы поэма «Ночь Гофмана» и опера «Сказки Гофмана».

Гофман с самого раннего детства больше всего на свете любил музыку, играл на

фортепьяно, скрипке, органе, пел, рисовал и сочинял стихи — но, несмотря на

это, должен был, как и все его предки, стать чиновником. Он покорился воле

семьи: окончил юридический факультет Кёнигсбергского университета и много лет

служил в разных судебных ведомствах. Жизненные обстоятельства складывались так,

что его творческие интересы должны были оставаться на втором месте – он всю