Хранители сказок | Балкарские народные сказки

У глубокого ущелья, возле высоких гор раскинулся большой аул. Неподалеку от него жили эмегены, и не было от них покоя людям. Самые храбрые из жителей аула погибали в схватке с великанами.

Жила в том ауле бедная вдова с сыном. Не было у мальчика особой силы, зато был он умный и очень смекалистый. Решил мальчик попробовать отбить у эмегенов охоту грабить аул

Однажды вечером сказал мальчик своей матери:

– Снаряди меня в дорогу. Дай мне круг сыру побольше да бурдюк с айраном.

Приготовила женщина все, что попросил сын, и пустился он в путь.

Пришел мальчик на берег реки, видит – набирает эмеген воду.

Страшновато стало мальчику, да только не показал он виду. А эмеген вдруг как закричит – даже эхо отозвалось в соседнем ущелье!

– Попался мне, человечек! Давай померяемся силой, а потом я отнесу тебя своим братьям, Вот уж будут они довольны!

– Согласен, – отвечал мальчик. – Кто победит из нас, прикажет другому исполнить все, что тот захочет! Попробуем сначала выдавить из земли масло!

Стал эмеген топтать изо всех сил землю ногами, да только не выступило из земли масло.

А мальчик незаметно присыпал бурдюк с айраном песком, наступил на него пяткой – разлился айран.

Удивился эмеген – откуда столько силы у маленького мальчика? – но смолчал.

А мальчик говорит:

– Можешь ли ты, эмеген, разбить рукою камень и выдавить из него воду?

Взял эмеген самый большой белый камень, да только ничего не смог с ним сделать.

Схватил мальчик круг сыра и разломил его на несколько частей, потом сжал – потекла из сыра сыворотка.

– Хоть и мал ты ростом, – проговорил эмеген, – да оказался сильнее меня. Приказывай что захочешь, я все исполню.

– Возьми меня на спину и перенеси через речку. Надо мне добраться до недругов, проучить их хорошенько, чтобы навсегда забыли они дорогу в наш аул.

Что было делать эмегену? Наполнил он водой огромный бурдюк, взвалил его на плечо, на другое плечо посадил мальчика и так переправился через быструю горную речку.

Возвратился эмеген к своим братьям, когда они о чем-то спорили.

Увидели великаны, что их брат несет мальчика, обрадовались.

– Хороший ужин будет у нас сегодня! – сказал один из них.

Эмеген, который принес мальчика, испуганно ответил:

– И думать забудьте об ужине. Это великан рода человеческого. Не смотрите, что он мал ростом: силы у него Больше, чем у любого из нас. Я сам видел, как он руками разламывал огромные камни и выжимал из них воду, а ногой выдавил из земли масло. Он прибыл к нам по важному делу. Сделайте так, чтобы он остался доволен. Не вздумайте рассердить его, иначе он перебьет всех нас.

Эмегены приняли мальчика как почетного гостя: поместили в кунацкой, готовили для него хорошую еду, оказывали всевозможные почести. А сами все-таки решили испытать его силу.

Дали они ему огромный бурдюк из буйволовой кожи.

– Принеси, – говорят, – нам воды. Никто из эмегенов не может донести этот бурдюк с водой.

Пришел мальчик к реке, разделся и вошел в воду. Стал он надувать бурдюк воздухом. Долго пришлось ему дуть; наконец наполнился бурдюк. Крепко завязал мальчик горлышко бурдюка и вынес его из воды.

Потом он оделся, взвалил бурдюк на плечи и пошел потихоньку к пещере, где жили эмегены. Не прошел он и половины пути – хлынул ливень. А когда мальчик был совсем рядом с пещерой, ливень стал еще сильнее.

Мальчик выпустил из бурдюка воздух и вошел в пещеру с пустым бурдюком.

– А где же вода? – спрашивает старший из эмегенов.

– Выгляните из пещеры и увидите воду, которую я принес.

Увидели эмегены потоки воды – не знали они, что прошел ливень, – испугались силача мальчика и решили избавиться от него.

– Давайте сегодня ночью зальем кипящей водой кунацкую, где спит мальчик. Вот и избавимся от него, – сказал старший из эмегенов.

Услышал мальчик эти слова, и, когда ложился спать, укрылся он своей буркой. А бурка была чудесной – она спасала хозяина и от жары и от холода, могла выдержать любую тяжесть. Укрывшись ею, мальчик мог спать спокойно.

Стали ночью эмегены лить в дымоход кипяток – залили им всю кунацкую.

Утром встал мальчик, стряхнул бурку, вышел из кунацкой. Удивились эмегены, увидев мальчика живым и здоровым.

– Как спалось тебе, дорогой гость? – спросил старший из эмегенов.

– Хорошо спалось, – отвечал мальчик. – Вот только немного блохи беспокоили.

Видят эмегены, что не взял мальчика кипяток, – решили забросать его камнями. И этот разговор услышал . мальчик и снова укрылся своей буркой.

Стали ночью эмегены бросать в дымоход кунацкой камни. Самый большой из камней упал на мальчика, да спасла его опять бурка.

Утром как ни в чем не бывало вышел он из кунацкой. Еще больше удивились эмегены, увидев мальчика живым и здоровым.

– Как спалось тебе нынче, дорогой гость? – спросил старший из эмегенов.

– Хорошо спалось, – отвечал мальчик. – Вот только чердак у вас, видно, дырявый – всю ночь оттуда глина падала. Пришлось мне переменить место.

Поняли эмегены, что не удастся им погубить мальчика. Стали они думать, как бы скорее выпроводить нежеланного гостя.

Пришел к мальчику старший из эмегенов и говорит:

– Ты знаешь, дорогой гость, что, по обычаю горцев, в течение трех дней хозяин не должен спрашивать гостя о причине его приезда. Ты гостишь у нас уже неделю. Нам всем хотелось бы узнать, какое дело привело тебя в наши края.

– Много раз вы грабили наш аул, угоняли у жителей скот. Вот и пришел я, чтобы получить у вас все то, что забрали вы в нашем ауле.

– Но ведь весь скот давно уже съеден.

– Тогда расплатитесь со мной золотом. Дайте мне золота столько, сколько войдет в кожаный мешок – тулук, – сшитый из шкуры трехгодовалого буйвола, – ответил мальчик.

Совсем не хотелось эмегенам выполнять это условие, да что делать? Собрали они все золото, какое было у них в запасе, но едва наполнили им тулук из кожи трехгодовалого буйвола.

– Мне не положено тащить на спине тулук. Пусть кто-нибудь из эмегенов отнесет его.

Никому из великанов не хотелось тащить тяжелый . мешок. Долго спорили они, кому идти в аул, а потом решили бросить жребий. Выпало тащить тулук тому эмегену, который принес мальчика. Утром отправились они в путь. Эмеген едва тащит тулук, а мальчик идет себе рядом, посвистывает.

Когда были они недалеко от аула, мальчик сказал:

– Не спеши, иди потихоньку, а я тем временем схожу домой, скажу, чтоб достойно встретили гостя.

Подошел эмеген к сакле, где жила мать мальчика, и слышит, как тот говорит матери:

– Приготовь угощение гостю.

– Право, не знаю, что и подать ему,— отвечает мать, как научил ее сын. – Ничего нет в доме, одна только нога эмегена осталась. Ее и зажарю.

Задрожал великан от страха. Оставил тулук возле сакли и побежал прочь без оглядки. Прибежал к своим братьям и говорит им:

– Хорошо, что мы выпроводили этого гостя. Узнал я, что его мать на ужин собиралась зажарить ногу эмегена. Значит, они могут и нас съесть.

Поднялось все племя эмегенов в страхе и ушло из ущелья куда глаза глядят. С тех пор не водилось в том краю эмегенов. Мальчик раздал золото эмегенов всем беднякам. И за: жили с тех пор люди в ауле спокойно.

Хранители сказок | Балкарские народные сказки

Храбрый портняжка

Эта советская мультипликация, снятая на студии «Союзмультфильм», является экранизацией сказки братьев Гримм.

В одном небольшом городке жил молоденький портной. Природа наградила парня веселым нравом и смекалкой. Но однажды, зазевавшись, портняжка прожег камзол своему заказчику. Дабы избежать неприятностей, он решает пока попутешествовать и помочь тем, кто нуждается в защите. В дорогу двадцатилетний паренек прихватил кусок жирного сыра, певчего стрижа и пояс, на котором было написано «Силачом слыву недаром, семерых одним ударом». А в это время на высокой горе скучал глупый великан. Подымив своей трубкой, он решил слегка развлечься, для чего направился в город. Жители испугались до смерти, закрыли окна и двери. Но портняжка, не зная страха, решил наказать наглеца и для начала закружил голову глупому великану так, что тот едва не потерял сознание. После этого великан предложил помериться силой с портняжкой и в доказательство своего превосходства выжал воду из камня. Каково же было его изумление, когда соперник достал из кармана камень и выжал из него гораздо больше воды. Глупцу было невдомек, что портняжка сжимает в руке простой кусок сыра…

Мультфильм «Храбрый портняжка» погрузит вас в удивительный мир великанов, королей и единорогов. Смотреть эту сказочную историю будет интересно и маленьким зрителям, и взрослым, которые смогут вернуться в яркий мир детства.

Молодой портной, доделав заказ для очередного клиента, решает его погладить. Внезапно залетевшие в окно мухи, усевшиеся прямо на его завтрак, отвлекают парня от работы. Пока он убивает назойливых насекомых и кормит ими своего щегла, раскаленный утюг прожигает камзол. Портняжка понимает, что обозленный заказчик так просто не спустит ему с рук порчу дорогой одежды, поэтому решает сбежать. С собой он берет только творог, который собирался съесть на завтрак, щегла и пояс, где вышивает фразу о том, что он способен одним ударом убить семерых.

Эти слова, а также бахвальская песенка портняжки привлекают к нему внимание великана, который решает победить зарвавшегося храбреца. Пока соперник пытается выдавить воду из камня и подбросить его как можно выше, юноша проделывает то же самое с творогом и щеглом, доказывая, что он сильнее, ведь воду из своего несостоявшегося завтрака он добывает одной рукой, а птица улетает так высоко, что скрывается из виду и больше не возвращается. Пораженный великан предлагает портняжке сразиться и со своим двоюродным братом, но парень одолевает и его.

Прознав о необычном юноше, король дает ему самые сложные поручения, чтобы навсегда избавиться от непредсказуемого силача, но тот выполняет их все. Вернувшись во дворец, портняжка никого там не находит, ведь все попрятались от страха, поэтому юный храбрец отправляется восвояси в поисках новых приключений.

Cмотреть «Храбрый портняжка» на всех устройствах

Приложение доступно для скачивания на iOS, Android, SmartTV и приставках

Подключить устройства

У глубокого ущелья, возле высоких гор, раскинулся большой аул. Неподалёку от него жили эмегены, и не было от них покоя людям. Самые храбрые из жителей аула погибали в схватке с великанами.

Жила в том ауле бедная вдова с сыном. Не было у мальчика особой силы, зато был он умный и очень смекалистый. Решил мальчик попробовать отбить у эмегенов охоту грабить аул.

Однажды вечером сказал мальчик своей матери:

– Снаряди меня в дорогу. Дай мне круг сыру побольше да бурдюк с айраном (айран – напиток из кислого молока).

Приготовила женщина всё, что попросил сын, и пустился он в путь.

Пришёл мальчик на берег реки, видит: набирает эмеген воду.

Страшновато стало мальчику, да только не показал он виду. А эмеген вдруг как закричит – даже эхо отозвалось в соседнем ущелье!

– Попался мне, человечек! Давай померяемся силой, а потом я отнесу тебя своим братьям. Вот уж будут они довольны!

– Согласен,– отвечал мальчик.– Кто победит из нас, прикажет другому исполнить всё, что тот захочет! Попробуем сначала выдавить из земли масло!

Стал эмеген топтать изо всех сил землю ногами, да только не выступило из земли масло.

А мальчик незаметно присыпал бурдюк с айраном песком, наступил на-него пяткой – разлился айран.

Удивился эмеген, откуда столько силы у маленького мальчика, но смолчал.

А мальчик говорит:

– Можешь ли ты, эмеген, разбить рукою камень и выдавить из него воду?

Взял эмеген самый большой белый камень, да только ничего не смог с ним сделать.

Схватил мальчик круг сыра и разломил его на несколько частей, потом сжал – потекла из сыра сыворотка.

– Хоть и мал ты ростом,– проговорил эмеген,– да оказался сильнее меня. Приказывай что захочешь, я всё исполню.

– Возьми меня на спину и перенеси через речку. Надо мне добраться до недругов, проучить их хорошенько, чтобы навсегда забыли они дорогу в наш аул.

Что было делать эмегену? Наполнил он водой огромный бурдюк, взвалил его на плечо, на другое плечо посадил мальчика и так переправился через быструю горную речку.

Возвратился эмеген к своим братьям, когда они о чём-то спорили.

Увидели великаны, что их бра.т несёт мальчика, обрадовались.

– Хороший ужин будет у нас сегодня! – сказал один из них.

Эмеген, который принёс мальчика, испуганно ответил:

– И думать забудьте об ужине. Это великан рода человеческого. Не смотрите, что он мал ростом: силы у него больше, чем у любого из нас. Я сам видел, как он руками разламывал огромные камни и выжимал из них воду, а ногой выдавливал из земли масло. Он прибыл к нам по важному делу. Сделайте так, чтобы он остался доволен. Не вздумайте рассердить его, иначе он перебьёт всех нас.

Эмегены приняли мальчика как почётного гостя: поместили в кунацкой, готовили для него хорошую еду, оказывали всевозможные почести. А сами всё-таки решили испытать его силу.

Дали они ему огромный бурдюк из буйволиной кожи.

– Принеси,– говорят,– нам воды. Никто из эмегенов не может донести этот бурдюк с водой.

Пришёл мальчик к реке, разделся и вошёл в воду. Стал он надувать бурдюк. Крепко завязал мальчик горлышко бурдюка и вынес его из воды.

Потом он оделся, взвалил бурдюк на плечи и пошёл потихоньку к пещере, где жили эмегены.

Не прошёл он и половины пути – хлынул ливень. А когда мальчик был совсем рядом с пещерой, ливень стал ещё сильнее.

Мальчик выпустил из бурдюка воздух и вошёл в пещеру с пустым бурдюком.

– А где же вода? – спрашивает старший из эмегенов. – Выгляните из пещеры и увидите воду, которую я принёс.

Увидели эмегены потоки воды – не знали они, что прошёл ливень,– испугались силача мальчика и решили избавиться от него.

– Давайте сегодня ночью зальём кипящей водой кунацкую, где спит мальчик. Вот и избавимся от него,– сказал старший из эмегенов.

Услышал мальчик эти слова, и, когда ложился спать, укрылся он своей буркой. А бурка была чудесной: она спасала хозяина и от жары и от холода, могла выдержатьлюбую тяжесть. Укрывшись ею, мальчик мог спать спокойно.

Стали ночью эмегены лить в дымоход кипяток – залили им всю кунацкую.

Утром встал мальчик, стряхнул бурку, вышел из кунацкой. Удивились эмегены, увидев мальчика живым и здоровым.

– Как спалось тебе, дорогой гость? – спросил старший из эмегенов.

– Хорошо спалось,– отвечал мальчик.– Вот только немного блохи беспокоили.

Видят эмегены, что не взял мальчика кипяток,– решили забросать его камнями. И этот разговор услышал мальчик и снова укрылся своей буркой.

Стали ночью эмегены бросать в дымоход кунацкой камни. Самый большой из камней упал на мальчика, да спасла его опять бурка.

Утром как ни в чём не бывало вышел он из кунацкой. Ещё больше удивились эмегены, увидев мальчика живым и здоровым.

– Как спалось тебе нынче, дорогой гость? – спросил старший из эмегенов.

– Хорошо спалось,– отвечал мальчик.– Вот только чердак у вас, видно, дырявый – всю ночь оттуда пыль сыпалась. Пришлось мне переменить место.

Поняли эмегены, что не удастся им погубить мальчика. Стали они думать, кaк бы скорее выпроводить нежеланного гостя. Пришёл к мальчику старший из эмегенов и говорит:

– Ты знаешь, дорогой гость, что, по обычаю горцев, в течение трёх дней хозяин не должен спрашивать гостя о причине его приезда. Ты гостишь у нас уже неделю. Нам всем хотелось бы узнать, какое дело привело тебя в наши края.

– Много раз вы грабили наш аул, угоняли у жителей скот. Вот и пришёл я, чтобы получить у вас всё то, что забрали вы в нашем ауле.

– Но ведь весь скот давно уже съеден.

– Тогда расплатитесь со мной золотом. Дайте мне золота столько, сколько войдёт в кожаный мешок – тулук,– сшитый из шкуры трёхгодовалого буйвола,– ответил мальчик.

Совсем не хотелось эмегенам выполнять это условие, да что делать? Собрали они всё золото, какое было у них в запасе, но едва наполнили им тулук из кожи трёхгодовалого буйвола.

– Мне не положено тащить на спине тулук. Пусть кто-нибудь из эмегенов отнесёт его.

Никому из великанов не хотелось тащить тяжёлый мешок.

Долго спорили они, кому идти в аул, а потом решили бросить жребий.

Выпало тащить тулук тому эмегену, который принёс мальчика.

Утром отправились они в путь. Эмеген едва тащит тулук, а мальчик идёт рядом да посвистывает.

Когда были они недалеко от аула, мальчик сказал:

– Не спеши, иди потихоньку, а я тем временем схожу домой, скажу, чтоб достойно встретили гостя.

Подошёл эмеген к сакле, где жила мать мальчика, и слышит, как тот говорит матери:

– Приготовь угощение гостю.

– Право, не знаю, что и подать ему,– отвечает мать, как научил её сын.– Ничего нет в доме, одна только нога эмегена осталась. Её и зажарю.

Задрожал великан от страха. Оставил тулук возле сакли и побежал прочь без оглядки.

Прибежал к своим братьям и говорит им:

– Хорошо, что мы выпроводили этого гостя. Узнал я, что его мать на ужин собиралась зажарить ногу эмегена. Значит, они могут и нас съесть.

Поднялось всё племя эмегенов в страхе и ушло из ущелья куда глаза глядят.

С тех пор не водилось в том краю эмегенов.

Мальчик раздал золото эмегенов всем беднякам. И зажили с тех пор люди в ауле спокойно.

| The Brave Little Tailor | |

|---|---|

The tailor provokes the giants. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Brave Little Tailor |

| Also known as | The Valiant Little Tailor |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 1640 (The Brave Tailor) |

| Country | Germany |

| Published in | Grimm’s Fairy Tales |

| Related | «Jack and the Beanstalk», «Jack the Giant Killer», «The Boy Who Had an Eating Match with a Troll» |

«The Brave Little Tailor» or «The Valiant Little Tailor» or «The Gallant Tailor» (German: Das tapfere Schneiderlein) is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm (KHM 20). «The Brave Little Tailor» is a story of Aarne–Thompson Type 1640, with individual episodes classified in other story types.[1]

Andrew Lang included it in The Blue Fairy Book.[2] The tale was translated as Seven at One Blow.[3] Another of many versions of the tale appears in A Book of Giants by Ruth Manning-Sanders.

It is about a humble tailor who tricks many giants and a ruthless king into believing in the tailor’s incredible feats of strength and bravery, leading to him winning wealth and power.

Origin[edit]

The Brothers Grimm published this tale in the first edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen in 1812, based on various oral and printed sources, including Der Wegkürzer (c. 1557) by Martinus Montanus.[1][4]

Synopsis[edit]

A tailor is preparing to eat some jam, but when flies settle on it, he kills seven of them with one blow of his hand. He makes a belt describing the deed, reading «Seven at One Blow». Inspired, he sets out into the world to seek his fortune. The tailor meets a giant who assumes that «Seven at One Blow» refers to seven men. The giant challenges the tailor. When the giant squeezes water from a boulder, the tailor squeezes milk, or whey, from cheese. The giant throws a rock far into the air, and it eventually lands. The tailor counters the feat by tossing a bird that flies away into the sky; the giant believes the small bird is a «rock» which is thrown so far that it never lands. Later, the giant asks the tailor to help him carry a tree. The tailor directs the giant to carry the trunk, while the tailor will carry the branches. Instead, the tailor climbs on, so the giant carries him as well, but it appears as if the tailor is supporting the branches.

Impressed, the giant brings the tailor to the giant’s home, where other giants live as well. During the night, the giant attempts to kill the tailor by bashing the bed. However, the tailor, having found the bed too large, had slept in the corner. Upon returning and seeing the tailor alive, the other giants flee in fear of the small man.

The tailor enters the royal service, but the other soldiers are afraid that he will lose his temper someday, and then seven of them might die with every blow. They tell the king that either the tailor leaves military service or they will. Afraid of being killed for sending him away, the king instead attempts to get rid of the tailor by sending him to defeat two giants along with a hundred horsemen, offering him half his kingdom and his daughter’s hand in marriage if the tailor can kill the giants. By throwing rocks at the two giants while they sleep, the tailor provokes the pair into fighting each other until they kill each other, at which time the tailor stabs the giants in their hearts.

The king, surprised the tailor has succeeded, balks on his promise, and requires more of the tailor before he may claim his rewards. The king next sends him after a unicorn, another seemingly impossible task, but the tailor traps it by standing before a tree, so that when the unicorn charges, he steps aside and it drives its horn into the trunk. The king subsequently sends him after a wild boar, but the tailor traps it in a chapel with a similar luring technique.

Duly impressed, the king relents, marries the tailor to the princess, and makes the tailor the ruler of half the original kingdom. The tailor’s new wife hears him talking in his sleep and realizes with fury that he was merely a tailor and not a noble hero. Upon the princess’s demands, the king promises to have him killed or carried off. A squire warns the tailor of the king’s plan. While the king’s servants are outside the door, the brave little tailor pretends to be talking in his sleep and says «Boy, make the jacket for me, and patch the trousers, or I will hit you across your ears with a yardstick! I have struck down seven with one blow, killed two giants, led away a unicorn, and captured a wild boar, and I am supposed to be afraid of those who are standing just outside the bedroom!» Terrified, the king’s servants leave. The king does not try to assassinate the tailor again and so the tailor lives out his days as a king in his own right.

Analysis[edit]

In the Aarne–Thompson–Uther system of folktale classification, the core of the story is motif type 1640, named The Brave Tailor for this story.[5] It also includes episodes of type 1060 (Squeezing Water from a Stone); type 1062 (A Contest in Throwing Stones); type 1052 (A Contest in Carrying a Tree); type 1051 (Springing with a Bent Tree); and type 1115 (Attempting to Kill the Hero in His Bed).[1]

«The Brave Little Tailor» has close similarities to other folktales collected around Europe, including «The Boy Who Had an Eating Match with a Troll» (Norway) and «Stan Bolovan» (Romania). It also shares many elements with «Jack the Giant Killer» (Cornwall and England, with ties to «Bluebeard» folktales of Brittany, and earlier Arthurian stories of Wales), though the protagonist in that story uses his guile to actually kill giants. Both the Scandinavian and British variants feature a recurring stock character fairy-tale hero, respectively: Jack (also associated with other giant-related stories, such as «Jack and the Beanstalk»), and Askeladden, also known as Boots. It is also similar to the Greek myth of Hercules in which Hercules is promised the ability to become a god if he slays the monsters, much like the main character in «The Brave Little Tailor» is promised the ability to become king through marrying the king’s daughter if he kills the beasts in the story.[citation needed]

The technique of tricking the later giants into fighting each other is identical to the technique used by Cadmus, in Greek mythology and a related surviving Greek folktale, to deal with the warriors who sprang up where he sowed dragon’s teeth into the soil.[6] In the 20th-century fantasy novel The Hobbit, a similar strategy is also employed by Gandalf to keep three trolls fighting amongst themselves, until the rising sun turns them to stone.

Variants[edit]

Folklorist Joseph Jacobs, in European Folk and Fairy Tales (or Europa’s Fairy Book) tried to reconstruct the protoform of the tale, which he named «A Dozen at One Blow».[7]

Europe[edit]

A variant has been reported to be present in Spanish folktale collections,[8] specially from the folktale compilations of the 19th century.[9] The tale has also been attested in American sources.[10]

A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi («Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage»), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found twenty-four variants of the tale across Italian sources.[11]

A Danish variant, Brave against his will («Den tapre Skrædder»), was collected by Jens Christian Bay.[12]

Joseph Jacobs located an English version from Aberdeen, named Johnny Gloke,[13] which was first obtained by Reverend Walter Gregor with the name John Glaick, the Brave Tailor and published in The Folk-Lore Journal.[14] Jacobs wondered how the Grimm’s tale managed to reach Aberdeen, but he suggests it might have originated from an English compilation of the brothers’ tales.[15] The tale was included in The Fir-Tree Fairy Book.[16]

Irish sources also contain a tale of lucky accidents and a fortunate fate that befalls the weaver who squashes the flies in his breakfast: The legend of the little Weaver of Duleek Gate (A Tale of Chivalry).[17] The tale was previously recorded in 1846 by Irish novelist Samuel Lover.[18]

In the Hungarian tale Százat egy ütéssel («A Hundred at One Blow»), at the end of the tale, the tailor mumbles in his sleep about threads and needles, and his wife, the princess, hears it. When confronted by his father-in-law, the tailor dismisses any accusations by saying he visited earlier a tailor’s shop in the city.[19]

A Russian variant collected by Alexander Afanasyev, called «The Tale of the Bogatyr Gol’ Voyanskoy» (the name roughly translatable as «poor warrior») has a peasant kill a number of horse-flies and mosquitoes bothering his horse. After that, he goes to adventure on said horse after leaving a message about his «deed» carved into a tree, inviting other heroes to join him. After being joined by Yeruslan Lazarevich, Churila Plyonkovich and Prince Bova, the four defeat the defenders of a kingdom ruled by a princess, upon which the peasant drinks the magic water the princess has, becomes a bogatyr for real and marries her.

Asia[edit]

A similar story, Kara Mustapha (Mustafa), the Hero, was collected by Hungarian folklorist Ignác Kúnos, from Turkish sources.[20]

Francis Hindes Groome proposed a parallel between this tale with Indian story of Valiant Vicky, the Brave Weaver.[21] Valiant Vicky was originally collected by British author Flora Annie Steel from a Punjabi source, with the title Fatteh Khân, Valiant Weaver.[22][23]

Sometimes the weaver or tailor does not become a ruler, but still gains an upper station in life (general, commander, prime minister). One such tale is Sigiris Sinno, the Giant, collected in Sri Lanka.[24] Other variant is The Nine-killing Khan.[25]

Character analysis[edit]

- Tailor – this character is clever, intelligent, and confident. He uses misdirection and other cunning to trick other characters. For example, various forms of psychological manipulation to influence the behavior of others, such as turning the pair of giants against each other, and playing on the assassins’ and the earlier giants’ assumptions and fears. Similarly, he uses decoy tactics to lure the quest animals (unicorn, boar) into his traps, and to avoid being killed in the first giant’s bed. This reliance on trickery and manipulation by the protagonist is a feature of the stock character of the antihero.

- King – this character is very mistrusting and judgmental, who uses the promise of half the kingdom to persuade the protagonist to take on seemingly deadly tasks. The king is one-dimensional as a character, and is essentially a plot device, the source of challenges for the protagonist to overcome to achieve the desired goal.

- Princess – the prize for completing all these challenges is the hand in marriage of the princess, and along with it, half the kingdom. She sets great store by the social class of royal birthright, so when she finds out that the man she has married is no more than a poor tailor, she is furious, and tries to have him killed. Her self-absorbed vindictiveness, and its easy defeat, is consistent with the stock character of the shrewish bride.

Adaptations[edit]

- Mickey Mouse appeared in a 1938 Disney short cartoon, Brave Little Tailor, based on this tale.

- Tibor Harsányi composed a suite, L’histoire du petit tailleur, for narrator, seven instruments, and percussion in 1950. One of the most famous recordings of this work was performed by the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire conducted by Georges Prêtre, with Peter Ustinov as the narrator reading in both English (Angel Records, 1966) and French (Pour les Enfants, EMI Classics France, 2002).

- The story formed an episode of the second season of Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics, a 1987–1989 anime television series.

- The Valiant Little Tailor was featured in the first season of Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child, a 1995–2000 HBO animated TV series, where it was set in the West African Sahel. The tailor was called Bongo and was voiced by David Alan Grier and also featured the voice talents of James Earl Jones as King Dakkar, Mark Curry as the Giant, Dawnn Lewis as Princess Songe, and Zakes Mokae as an exclusive character named Mr. Barbooska.

- Le vaillant petit tailleur is a 2004 French-language novel by Éric Chevillard retelling the fairy tale in a postmodernist way.

- «Satmaar Palowan» («The Wrestler Who Kills Seven»), a short story by Bengali writer Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, was inspired by this tale.[26]

- A Soviet cartoon based on the fairy tale was produced in 1964, directed by the Brumberg sisters.

- In the game Fairytale Fights, he acts as the main antagonist who is stealing all the fame and glory from four fable characters (Little Red Riding Hood, Snow White, Jack, and The Naked Emperor) by stalking them throughout the game and lets them do all the life-threatening hard work before swooping in after every victory to steal the prize and claim the credit for himself. His fame was short-lived after the heroes defeated him and exposed his storybook to the fairytale village that he’s a fraud, the Tailor tried to escape but was flattened and killed by the father giant who drop the heroes’ books on top of him and taken his book, this resulted of the heroes’ fame finally being restored and the villagers cheering them on.

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c Ashliman, D. L. (2017). «The Brave Little Tailor». University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Andrew Lang, The Blue Fairy Book, «The Brave Little Tailor»

- ^ Wiggin, Kate Douglas Smith; Smith, Nora Archibald. Tales of Laughter : A Third Fairy Book. New York: McClure. 1908. pp. 138-145.

- ^ Cosquin, Emmanuel (1876). «Contes populaires lorrains recueillis dans un village du Barrois à Montiers-sur-Saulx (Meuse) (suite)». Romania (in French). 5 (19): 333–366. doi:10.3406/roma.1876.7128. ISSN 0035-8029.

- ^ Kinnes, Tormod (2009). «The ATU System». AT Types of Folktales. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ Richard M. Dorson, «Foreword», p xxii, Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, European Folk and Fairy Tales, «A Dozen at One Blow»

- ^ Boggs, Ralph Steele. Index of Spanish folktales, classified according to Antti Aarne’s «Types of the folktale». Chicago: University of Chicago. 1930. p. 136.

- ^ Amores, Monstserrat. Catalogo de cuentos folcloricos reelaborados por escritores del siglo XIX. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Departamento de Antropología de España y América. 1997. pp. 293–294. ISBN 84-00-07678-8

- ^ Baughman, Ernest Warren. Type and Motif-index of the Folktales of England and North America. Indiana University Folklore Series No. 20. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton & Co 1966. p. 42.

- ^ Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral and Non Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Motifs or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. p. 273.

- ^ Bay, J. Christian. Danish Fairy & Folk Tales. New York and London: Harper and Brothers Publishers. 1899. pp. 175-188.[1]

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. More English Fairy Tales. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. 1894. pp. 71-74.

- ^ The Folk-Lore Journal. Vol. VII. (January–December 1889). 1889. London: Published for the Folk-Lore Society by Elliot Stock pp. 163-165.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. More English Fairy Tales. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. 1894. p. 227.

- ^ Johnson, Clifton. The fir-tree fairy book; favorite fairy tales. Boston: Little, Brown. 1912. pp. 179-183.

- ^ Graves, Alfred Perceval. The Irish fairy book. London: T. F. Unwin. 1909. pp. 167-179.

- ^ Lover, Samuel. Legends And Stories of Ireland. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard. 1846. pp. 211-219.

- ^ János Erdélyi. Magyar népmesék. Pest: Heckenast Gusztáv Sajátja. 1855. pp. 128-134.

- ^ Kunos, Ignacz. Forty-four Turkish fairy tales. London: G. Harrap. pp. 50-57.

- ^ Groome, Francis Hindes. Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. 1899. pp. lxviii–lxix.

- ^ Steel, Flora Annie Webster. Tales of the Punjab: told by the people. London: Macmillan. 1917. pp. 80-88 and 305.

- ^ Steel, Flora Annie; Temple, R. C. Wide-awake Stories. London: Trübner & Co. 1884. pp. 89-97.

- ^ Village Folk-Tales of Ceylon. Collected and translated by H. Parker. Vol. I. New Delhi/Madras: Asian Educational Services. 1997 [1910]. pp. 289-292.

- ^ Swynnerton, Charles. Indian nights’ entertainment; or, Folk-tales from the Upper Indus. London: Stock. 1892. pp. 208-212.

- ^ «সাতমার পালোয়ান : উপেন্দ্রকিশোর রায়চৌধুরী (ছোটোগল্প), SATMAR PALOAN (Page 1) — STORY (ছোটগল্প) — Banglalibrary». omegalibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-27. Retrieved 2016-12-26.

References[edit]

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 148–165.

- Gregor, Walter. «John Glaick, the Brave Tailor.» The Folk-Lore Journal 7, no. 2 (1889): 163-65. JSTOR 1252657.

- Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s sons. 1916. pp. 238–239.

- Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 215–217. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Bødker, Laurits. “The Brave Tailor in Danish Tradition”. In: Studies in Folklore in Honor of Distinguished Service Professor Stith Thompson. Ed. W. Edson Richmond. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1957. pp. 1–23.

- Jason, Heda (1993). «The brave little tailor. Carnivalesque forms in oral literature». Acta Ethnographica Hungarica. 38 (4): 385–395. ISSN 0001-5628.

- Senft, Gunter. «What Happened to ‘The Fearless Tailor’ in Kilivila. A European Fairy-Tale — from the South Seas.» In: Anthropos 87, no. 4/6 (1992): 407-21. JSTOR 40462653.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- The complete set of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, including The Brave Little Tailor at Standard Ebooks

| The Brave Little Tailor | |

|---|---|

The tailor provokes the giants. |

|

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Brave Little Tailor |

| Also known as | The Valiant Little Tailor |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 1640 (The Brave Tailor) |

| Country | Germany |

| Published in | Grimm’s Fairy Tales |

| Related | «Jack and the Beanstalk», «Jack the Giant Killer», «The Boy Who Had an Eating Match with a Troll» |

«The Brave Little Tailor» or «The Valiant Little Tailor» or «The Gallant Tailor» (German: Das tapfere Schneiderlein) is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm (KHM 20). «The Brave Little Tailor» is a story of Aarne–Thompson Type 1640, with individual episodes classified in other story types.[1]

Andrew Lang included it in The Blue Fairy Book.[2] The tale was translated as Seven at One Blow.[3] Another of many versions of the tale appears in A Book of Giants by Ruth Manning-Sanders.

It is about a humble tailor who tricks many giants and a ruthless king into believing in the tailor’s incredible feats of strength and bravery, leading to him winning wealth and power.

Origin[edit]

The Brothers Grimm published this tale in the first edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen in 1812, based on various oral and printed sources, including Der Wegkürzer (c. 1557) by Martinus Montanus.[1][4]

Synopsis[edit]

A tailor is preparing to eat some jam, but when flies settle on it, he kills seven of them with one blow of his hand. He makes a belt describing the deed, reading «Seven at One Blow». Inspired, he sets out into the world to seek his fortune. The tailor meets a giant who assumes that «Seven at One Blow» refers to seven men. The giant challenges the tailor. When the giant squeezes water from a boulder, the tailor squeezes milk, or whey, from cheese. The giant throws a rock far into the air, and it eventually lands. The tailor counters the feat by tossing a bird that flies away into the sky; the giant believes the small bird is a «rock» which is thrown so far that it never lands. Later, the giant asks the tailor to help him carry a tree. The tailor directs the giant to carry the trunk, while the tailor will carry the branches. Instead, the tailor climbs on, so the giant carries him as well, but it appears as if the tailor is supporting the branches.

Impressed, the giant brings the tailor to the giant’s home, where other giants live as well. During the night, the giant attempts to kill the tailor by bashing the bed. However, the tailor, having found the bed too large, had slept in the corner. Upon returning and seeing the tailor alive, the other giants flee in fear of the small man.

The tailor enters the royal service, but the other soldiers are afraid that he will lose his temper someday, and then seven of them might die with every blow. They tell the king that either the tailor leaves military service or they will. Afraid of being killed for sending him away, the king instead attempts to get rid of the tailor by sending him to defeat two giants along with a hundred horsemen, offering him half his kingdom and his daughter’s hand in marriage if the tailor can kill the giants. By throwing rocks at the two giants while they sleep, the tailor provokes the pair into fighting each other until they kill each other, at which time the tailor stabs the giants in their hearts.

The king, surprised the tailor has succeeded, balks on his promise, and requires more of the tailor before he may claim his rewards. The king next sends him after a unicorn, another seemingly impossible task, but the tailor traps it by standing before a tree, so that when the unicorn charges, he steps aside and it drives its horn into the trunk. The king subsequently sends him after a wild boar, but the tailor traps it in a chapel with a similar luring technique.

Duly impressed, the king relents, marries the tailor to the princess, and makes the tailor the ruler of half the original kingdom. The tailor’s new wife hears him talking in his sleep and realizes with fury that he was merely a tailor and not a noble hero. Upon the princess’s demands, the king promises to have him killed or carried off. A squire warns the tailor of the king’s plan. While the king’s servants are outside the door, the brave little tailor pretends to be talking in his sleep and says «Boy, make the jacket for me, and patch the trousers, or I will hit you across your ears with a yardstick! I have struck down seven with one blow, killed two giants, led away a unicorn, and captured a wild boar, and I am supposed to be afraid of those who are standing just outside the bedroom!» Terrified, the king’s servants leave. The king does not try to assassinate the tailor again and so the tailor lives out his days as a king in his own right.

Analysis[edit]

In the Aarne–Thompson–Uther system of folktale classification, the core of the story is motif type 1640, named The Brave Tailor for this story.[5] It also includes episodes of type 1060 (Squeezing Water from a Stone); type 1062 (A Contest in Throwing Stones); type 1052 (A Contest in Carrying a Tree); type 1051 (Springing with a Bent Tree); and type 1115 (Attempting to Kill the Hero in His Bed).[1]

«The Brave Little Tailor» has close similarities to other folktales collected around Europe, including «The Boy Who Had an Eating Match with a Troll» (Norway) and «Stan Bolovan» (Romania). It also shares many elements with «Jack the Giant Killer» (Cornwall and England, with ties to «Bluebeard» folktales of Brittany, and earlier Arthurian stories of Wales), though the protagonist in that story uses his guile to actually kill giants. Both the Scandinavian and British variants feature a recurring stock character fairy-tale hero, respectively: Jack (also associated with other giant-related stories, such as «Jack and the Beanstalk»), and Askeladden, also known as Boots. It is also similar to the Greek myth of Hercules in which Hercules is promised the ability to become a god if he slays the monsters, much like the main character in «The Brave Little Tailor» is promised the ability to become king through marrying the king’s daughter if he kills the beasts in the story.[citation needed]

The technique of tricking the later giants into fighting each other is identical to the technique used by Cadmus, in Greek mythology and a related surviving Greek folktale, to deal with the warriors who sprang up where he sowed dragon’s teeth into the soil.[6] In the 20th-century fantasy novel The Hobbit, a similar strategy is also employed by Gandalf to keep three trolls fighting amongst themselves, until the rising sun turns them to stone.

Variants[edit]

Folklorist Joseph Jacobs, in European Folk and Fairy Tales (or Europa’s Fairy Book) tried to reconstruct the protoform of the tale, which he named «A Dozen at One Blow».[7]

Europe[edit]

A variant has been reported to be present in Spanish folktale collections,[8] specially from the folktale compilations of the 19th century.[9] The tale has also been attested in American sources.[10]

A scholarly inquiry by Italian Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi («Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage»), produced in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found twenty-four variants of the tale across Italian sources.[11]

A Danish variant, Brave against his will («Den tapre Skrædder»), was collected by Jens Christian Bay.[12]

Joseph Jacobs located an English version from Aberdeen, named Johnny Gloke,[13] which was first obtained by Reverend Walter Gregor with the name John Glaick, the Brave Tailor and published in The Folk-Lore Journal.[14] Jacobs wondered how the Grimm’s tale managed to reach Aberdeen, but he suggests it might have originated from an English compilation of the brothers’ tales.[15] The tale was included in The Fir-Tree Fairy Book.[16]

Irish sources also contain a tale of lucky accidents and a fortunate fate that befalls the weaver who squashes the flies in his breakfast: The legend of the little Weaver of Duleek Gate (A Tale of Chivalry).[17] The tale was previously recorded in 1846 by Irish novelist Samuel Lover.[18]

In the Hungarian tale Százat egy ütéssel («A Hundred at One Blow»), at the end of the tale, the tailor mumbles in his sleep about threads and needles, and his wife, the princess, hears it. When confronted by his father-in-law, the tailor dismisses any accusations by saying he visited earlier a tailor’s shop in the city.[19]

A Russian variant collected by Alexander Afanasyev, called «The Tale of the Bogatyr Gol’ Voyanskoy» (the name roughly translatable as «poor warrior») has a peasant kill a number of horse-flies and mosquitoes bothering his horse. After that, he goes to adventure on said horse after leaving a message about his «deed» carved into a tree, inviting other heroes to join him. After being joined by Yeruslan Lazarevich, Churila Plyonkovich and Prince Bova, the four defeat the defenders of a kingdom ruled by a princess, upon which the peasant drinks the magic water the princess has, becomes a bogatyr for real and marries her.

Asia[edit]

A similar story, Kara Mustapha (Mustafa), the Hero, was collected by Hungarian folklorist Ignác Kúnos, from Turkish sources.[20]

Francis Hindes Groome proposed a parallel between this tale with Indian story of Valiant Vicky, the Brave Weaver.[21] Valiant Vicky was originally collected by British author Flora Annie Steel from a Punjabi source, with the title Fatteh Khân, Valiant Weaver.[22][23]

Sometimes the weaver or tailor does not become a ruler, but still gains an upper station in life (general, commander, prime minister). One such tale is Sigiris Sinno, the Giant, collected in Sri Lanka.[24] Other variant is The Nine-killing Khan.[25]

Character analysis[edit]

- Tailor – this character is clever, intelligent, and confident. He uses misdirection and other cunning to trick other characters. For example, various forms of psychological manipulation to influence the behavior of others, such as turning the pair of giants against each other, and playing on the assassins’ and the earlier giants’ assumptions and fears. Similarly, he uses decoy tactics to lure the quest animals (unicorn, boar) into his traps, and to avoid being killed in the first giant’s bed. This reliance on trickery and manipulation by the protagonist is a feature of the stock character of the antihero.

- King – this character is very mistrusting and judgmental, who uses the promise of half the kingdom to persuade the protagonist to take on seemingly deadly tasks. The king is one-dimensional as a character, and is essentially a plot device, the source of challenges for the protagonist to overcome to achieve the desired goal.

- Princess – the prize for completing all these challenges is the hand in marriage of the princess, and along with it, half the kingdom. She sets great store by the social class of royal birthright, so when she finds out that the man she has married is no more than a poor tailor, she is furious, and tries to have him killed. Her self-absorbed vindictiveness, and its easy defeat, is consistent with the stock character of the shrewish bride.

Adaptations[edit]

- Mickey Mouse appeared in a 1938 Disney short cartoon, Brave Little Tailor, based on this tale.

- Tibor Harsányi composed a suite, L’histoire du petit tailleur, for narrator, seven instruments, and percussion in 1950. One of the most famous recordings of this work was performed by the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire conducted by Georges Prêtre, with Peter Ustinov as the narrator reading in both English (Angel Records, 1966) and French (Pour les Enfants, EMI Classics France, 2002).

- The story formed an episode of the second season of Grimm’s Fairy Tale Classics, a 1987–1989 anime television series.

- The Valiant Little Tailor was featured in the first season of Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child, a 1995–2000 HBO animated TV series, where it was set in the West African Sahel. The tailor was called Bongo and was voiced by David Alan Grier and also featured the voice talents of James Earl Jones as King Dakkar, Mark Curry as the Giant, Dawnn Lewis as Princess Songe, and Zakes Mokae as an exclusive character named Mr. Barbooska.

- Le vaillant petit tailleur is a 2004 French-language novel by Éric Chevillard retelling the fairy tale in a postmodernist way.

- «Satmaar Palowan» («The Wrestler Who Kills Seven»), a short story by Bengali writer Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, was inspired by this tale.[26]

- A Soviet cartoon based on the fairy tale was produced in 1964, directed by the Brumberg sisters.

- In the game Fairytale Fights, he acts as the main antagonist who is stealing all the fame and glory from four fable characters (Little Red Riding Hood, Snow White, Jack, and The Naked Emperor) by stalking them throughout the game and lets them do all the life-threatening hard work before swooping in after every victory to steal the prize and claim the credit for himself. His fame was short-lived after the heroes defeated him and exposed his storybook to the fairytale village that he’s a fraud, the Tailor tried to escape but was flattened and killed by the father giant who drop the heroes’ books on top of him and taken his book, this resulted of the heroes’ fame finally being restored and the villagers cheering them on.

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c Ashliman, D. L. (2017). «The Brave Little Tailor». University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Andrew Lang, The Blue Fairy Book, «The Brave Little Tailor»

- ^ Wiggin, Kate Douglas Smith; Smith, Nora Archibald. Tales of Laughter : A Third Fairy Book. New York: McClure. 1908. pp. 138-145.

- ^ Cosquin, Emmanuel (1876). «Contes populaires lorrains recueillis dans un village du Barrois à Montiers-sur-Saulx (Meuse) (suite)». Romania (in French). 5 (19): 333–366. doi:10.3406/roma.1876.7128. ISSN 0035-8029.

- ^ Kinnes, Tormod (2009). «The ATU System». AT Types of Folktales. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ Richard M. Dorson, «Foreword», p xxii, Georgias A. Megas, Folktales of Greece, University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 1970

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, European Folk and Fairy Tales, «A Dozen at One Blow»

- ^ Boggs, Ralph Steele. Index of Spanish folktales, classified according to Antti Aarne’s «Types of the folktale». Chicago: University of Chicago. 1930. p. 136.

- ^ Amores, Monstserrat. Catalogo de cuentos folcloricos reelaborados por escritores del siglo XIX. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Departamento de Antropología de España y América. 1997. pp. 293–294. ISBN 84-00-07678-8

- ^ Baughman, Ernest Warren. Type and Motif-index of the Folktales of England and North America. Indiana University Folklore Series No. 20. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton & Co 1966. p. 42.

- ^ Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral and Non Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Motifs or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. p. 273.

- ^ Bay, J. Christian. Danish Fairy & Folk Tales. New York and London: Harper and Brothers Publishers. 1899. pp. 175-188.[1]

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. More English Fairy Tales. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. 1894. pp. 71-74.

- ^ The Folk-Lore Journal. Vol. VII. (January–December 1889). 1889. London: Published for the Folk-Lore Society by Elliot Stock pp. 163-165.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph. More English Fairy Tales. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. 1894. p. 227.

- ^ Johnson, Clifton. The fir-tree fairy book; favorite fairy tales. Boston: Little, Brown. 1912. pp. 179-183.

- ^ Graves, Alfred Perceval. The Irish fairy book. London: T. F. Unwin. 1909. pp. 167-179.

- ^ Lover, Samuel. Legends And Stories of Ireland. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard. 1846. pp. 211-219.

- ^ János Erdélyi. Magyar népmesék. Pest: Heckenast Gusztáv Sajátja. 1855. pp. 128-134.

- ^ Kunos, Ignacz. Forty-four Turkish fairy tales. London: G. Harrap. pp. 50-57.

- ^ Groome, Francis Hindes. Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. 1899. pp. lxviii–lxix.

- ^ Steel, Flora Annie Webster. Tales of the Punjab: told by the people. London: Macmillan. 1917. pp. 80-88 and 305.

- ^ Steel, Flora Annie; Temple, R. C. Wide-awake Stories. London: Trübner & Co. 1884. pp. 89-97.

- ^ Village Folk-Tales of Ceylon. Collected and translated by H. Parker. Vol. I. New Delhi/Madras: Asian Educational Services. 1997 [1910]. pp. 289-292.

- ^ Swynnerton, Charles. Indian nights’ entertainment; or, Folk-tales from the Upper Indus. London: Stock. 1892. pp. 208-212.

- ^ «সাতমার পালোয়ান : উপেন্দ্রকিশোর রায়চৌধুরী (ছোটোগল্প), SATMAR PALOAN (Page 1) — STORY (ছোটগল্প) — Banglalibrary». omegalibrary.com. Archived from the original on 2016-12-27. Retrieved 2016-12-26.

References[edit]

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri. Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm. Erster Band (NR. 1-60). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. 1913. pp. 148–165.

- Gregor, Walter. «John Glaick, the Brave Tailor.» The Folk-Lore Journal 7, no. 2 (1889): 163-65. JSTOR 1252657.

- Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam’s sons. 1916. pp. 238–239.

- Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. pp. 215–217. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

Further reading[edit]

- Bødker, Laurits. “The Brave Tailor in Danish Tradition”. In: Studies in Folklore in Honor of Distinguished Service Professor Stith Thompson. Ed. W. Edson Richmond. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1957. pp. 1–23.

- Jason, Heda (1993). «The brave little tailor. Carnivalesque forms in oral literature». Acta Ethnographica Hungarica. 38 (4): 385–395. ISSN 0001-5628.

- Senft, Gunter. «What Happened to ‘The Fearless Tailor’ in Kilivila. A European Fairy-Tale — from the South Seas.» In: Anthropos 87, no. 4/6 (1992): 407-21. JSTOR 40462653.

External links[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- The complete set of Grimms’ Fairy Tales, including The Brave Little Tailor at Standard Ebooks

История о молодом портном, который стал очень смелым, когда убил семь мух одним ударом. Он отправился в путешествие по миру с поясом, на котором было написано «Когда злой бываю, семерых убиваю». Храбрый и хитрый портной справился с великанами и разбойниками, перехитрил самого короля…

Храбрый портной читать

Вот как-то сидит портной Ганс на столе, шьет и слышит — кричат на улице: «Варенье! Сливовое варенье! Кому варенья?»

«Варенье! — подумал портной. — Да еще сливовое. Это хорошо».

Подумал он так и закричал в окошко:

— Тетка, тетка, иди сюда! Дай-ка мне варенья!

Купил он этого варенья полбаночки, отрезал себе кусок хлеба, намазал его вареньем и стал жилетку дошивать.

«Вот, — думает, — дошью жилетку и варенья поем».

А в комнате у портного Ганса много-много мух было, прямо не сосчитать сколько. Может, тысяча, а может, и две тысячи. Почуяли мухи, что вареньем пахнет, и налетели на хлеб.

— Мухи, мухи, — говорит им портной, — вас-то кто сюда звал? Зачем на мое варенье налетели?

А мухи его не слушают и едят варенье. Тут портной рассердился, взял тряпку да как ударит тряпкой по мухам, так семь мух сразу и убил.

— Вот какой я храбрый! — сказал портной Ганс. — Об этом весь город должен узнать. Да что город? Пусть весь мир узнает! Скрою-ка я себе новый пояс и вышью на нем большими буквами: «Когда злой бываю, семерых убиваю».

Так он и сделал. Потом надел на себя новый пояс, сунул в карман кусок творожного сыра на дорогу и вышел из дому.

У самых своих ворот увидел он птицу, запутавшуюся в кустарнике. Бьется птица, кричит, а выбраться не может. Поймал Ганс птицу и сунул ее в тот же карман, где у него творожный сыр лежал.

Шел он, шел и пришел наконец к высокой горе. Забрался на вершину и видит: сидит на горе великан и кругом посматривает.

— Здравствуй, приятель! — говорит ему портной Ганс. — Пойдем вместе со мною по свету странствовать.

— Какой ты мне приятель! — отвечает великан. — Ты слабенький, маленький, а я большой и сильный. Уходи, пока цел.

— А это ты видел? — говорит портной Ганс и показывает великану свой пояс. А на поясе у Ганса вышито крупными буквами: «Когда злой бываю, семерых убиваю».

Прочел великан и подумал: «Кто его знает, может, он и верно сильный человек. Надо его испытать».

Взял великан в руки камень и так крепко сжал его, что из камня потекла вода.

— А теперь ты попробуй это сделать, — сказал великан.

— Только и всего? — говорит портной. — Ну, для меня это дело пустое.

Вынул он потихоньку из кармана кусок творожного сыра и стиснул в кулаке. Из кулака вода так и полилась на землю.

Удивился великан такой силе, но решил испытать Ганса еще раз. Поднял с земли камень и швырнул его в небо. Так далеко закинул, что камня и видно не стало.

— Ну-ка, — говорит он портному, — попробуй и ты так.

— Высоко ты бросаешь, — сказал портной. — А все же твой камень упал на землю. Вот я брошу, так прямо на небо камень закину.

Сунул он руку в карман, выхватил птицу и швырнул ее вверх. Птица взвилась высоко-высоко в небо и улетела.

— Что, приятель, каково? — спрашивает портной Ганс.

— Неплохо, — говорит великан. — А вот посмотрим теперь, можешь ли ты дерево на плечах снести.

Подвел он портного к большому срубленному дубу и говорит :

— Если ты такой сильный, так помоги мне вынести это дерево из лесу.

— Ладно, — ответил портной, а про себя подумал: «Я слаб, да умен, а ты силен, да глуп. Я всегда тебя обмануть сумею». И говорит великану:

— Ты себе на плечи только ствол взвали, а я понесу все ветви и сучья. Ведь они потяжелее будут.

Так они и сделали.

Великан взвалил себе на плечи ствол и понес. А портной вскочил на ветку и уселся на ней верхом. Тащит великан на себе все дерево, да еще и портного в придачу. А оглянуться назад не может. Ему ветви мешают. Едет портной Ганс верхом на ветке и песенку поет:

— Как пошли наши ребята

Из ворот на огород…

Долго тащил великан дерево, наконец устал и говорит:

— Слушай, портной, я сейчас дерево на землю сброшу. Устал я очень.

Тут портной соскочил с ветки и ухватился за дерево обеими руками, как будто он все время шел позади великана.

— Эх ты, — сказал он великану, — такой большой, а силы, видать, у тебя мало.

Оставили они дерево и пошли дальше.

Шли, шли и пришли наконец в пещеру. Там у костра сидели пять великанов, и у каждого в руках было по жареному барану.

— Вот, — говорит великан, который привел Ганса, — тут мы и живем. Забирайся-ка на эту кровать, ложись и отдыхай.

Посмотрел портной на кровать и подумал: «Ну, эта кровать не по мне. Чересчур велика».

Подумал он так, нашел в пещере уголок потемнее и лег спать. А ночью великан проснулся, взял большой железный лом и ударил с размаху но кровати.

— Ну, — сказал великан своим товарищам, — теперь-то я избавился от этого силача.

Встали утром все шестеро великанов и пошли в лес дрова рубить.

А портной тоже встал, умылся, причесался и пошел за ними следом.

Увидели великаны в лесу Ганса и перепугались.

«Ну, — думают, — если мы даже ломом железным его не убили, так он теперь всех нас перебьет».

И разбежались великаны в разные стороны.

А портной посмеялся над ними и пошел куда глаза глядят.

Шел он, шел и пришел наконец к королевскому дворцу. Там у ворот он лег на зеленую траву и крепко заснул.

А пока он спал, увидели его королевские слуги, наклонились над ним и прочли у него на поясе надпись: «Когда злой бываю, семерых убиваю».

— Вот так силач к нам пришел, — сказали они. — Надо королю о нем доложить.

Побежали королевские слуги к своему королю и говорят:

— Лежит у ворот твоего дворца силач. Хорошо бы его на службу взять. Если война будет, он нам пригодится.

Король обрадовался.

— Верно, — говорит, — зовите его сюда.

Выспался портной, протер глаза и пошел служить королю.

Служит он день, служит другой. И стали королевские воины говорить друг другу:

— Чего нам хорошего ждать от этого силача? Ведь он, когда злой бывает, семерых убивает. Так у него и на поясе написано.

Пошли они к королю и сказали:

— Не хотим служить с ним вместе. Он всех нас перебьет, если рассердится. Отпусти нас со службы.

А король уже и сам жалел, что взял такого силача к себе на службу.

«А вдруг, — думал он, — этот силач и в самом деле рассердится, воинов моих перебьет, меня зарубит и сам на мое место сядет. Как бы от него избавиться?»

Позвал он портного Ганса и говорит:

— В моем королевстве в дремучем лесу живут два разбойника, и оба они такие силачи, что никто к ним близко подойти не смеет. Приказываю тебе найти их и одолеть. А в помощь тебе даю сотню всадников.

— Ладно, — сказал портной. — Я, когда злой бываю, семерых убиваю. А с двумя-то разбойниками я и шутя справлюсь.

И пошел он в лес. А сто королевских всадников за ним следом поскакали.

На опушке леса обернулся портной к всадникам и говорит:

— Вы, всадники, здесь подождите, а я с разбойниками один справлюсь.

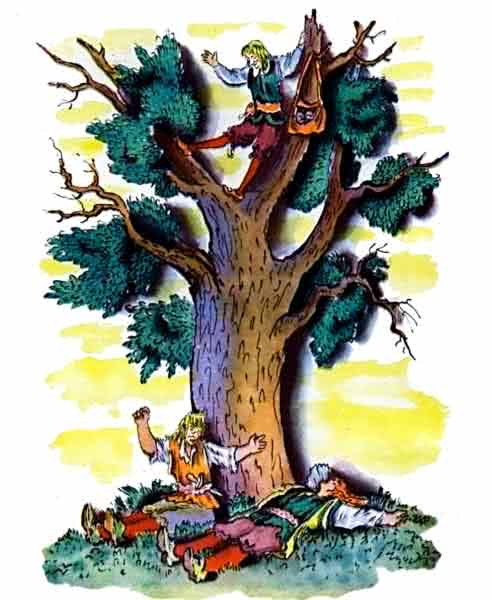

Вошел он в чащу и стал оглядываться кругом. Видит: лежат под большим деревом два разбойника и так храпят во сне, что ветки над ними колышутся.

Портной недолго думая набрал полные карманы камней, залез на дерево и стал сверху бросать камни в одного разбойника. То в грудь попадет ему, то в лоб. А разбойник храпит и ничего не слышит.

И вдруг один камень стукнул разбойника по носу. Разбойник проснулся и толкает своего товарища в бок:

— Ты что меня бьешь?

— Да что ты, — говорит другой разбойник. — Я тебя не бью, тебе, видно, приснилось.

И опять они оба заснули.

Тут портной начал бросать камни в другого разбойника.

Тот тоже проснулся и стал кричать на товарища:

— Ты что в меня камни бросаешь? С ума сошел?

Да как ударит своего приятеля но лбу. А тот его. И стали они драться камнями, палками и кулаками.

И до тех пор дрались, пока друг друга насмерть не убили.

Тогда портной соскочил с дерева, вышел на опушку леса и говорит всадникам:

— Дело сделано. Оба убиты. Ну и злые же эти разбойники — и камнями они в меня швыряли, и кулаками на меня замахивались, да что им со мной поделать? Ведь я, когда злой бываю, семерых убиваю.

Въехали королевские всадники в лес и видят: верно, лежат на земле два разбойника, лежат и не шевелятся — оба убиты.

Вернулся портной Ганс во дворец к королю. А король хитрый был. Выслушал он Ганса и думает: «Ладно, с разбойниками ты справился, а вот сейчас я тебе такую задачу задам, что ты у меня в живых не останешься».

— Слушай, — говорит Гансу король, — поди-ка ты опять в лес, излови свирепого зверя единорога.

— Изволь, — говорит портной Ганс, — это я могу. Ведь я, когда злой бываю, семерых убиваю. Так с одним-то единорогом живо справлюсь.

Взял он с собой топор и веревку и опять пошел в лес.

Недолго пришлось портному Гансу искать единорога: зверь сам к нему навстречу выскочил — страшный, шерсть дыбом, рог острый, как меч.

Кинулся на портного единорог и хотел было проткнуть его своим рогом, да портной за дерево спрятался. Единорог с разбегу так и всадил в дерево свой острый рог. Рванулся назад, а вытащить не может.

— Вот теперь-то ты от меня не уйдешь! — сказал портной, набросил единорогу на шею веревку, вырубил топором его рог из дерева и повел зверя на веревке к королю.

Привел единорога прямо в королевский дворец.

А единорог, как только увидел короля в золотой короне и красной мантии, засопел, захрипел. Глаза у него кровью налились, шерсть дыбом, рог как меч торчит. Испугался король и кинулся бежать. И все его воины за ним. Далеко убежал король, так далеко, что назад дороги найти не смог.

А портной стал себе спокойно жить да поживать, куртки, штаны и жилетки шить. Пояс свой он на стенку повесил и больше ни великанов, ни разбойников, ни единорогов на своем веку не видал.

(Перевод с немецкого А. Введенского под редакцией С. Маршака, илл. В.Конашевича)

❤️ 200

🔥 146

😁 154

😢 71

👎 87

🥱 109

Добавлено на полку

Удалено с полки

Достигнут лимит