| Zeus | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the Twelve Olympians | |

Zeus de Smyrne, discovered in Smyrna in 1680[1] |

|

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Planet | Jupiter |

| Symbol | Thunderbolt, eagle, bull, oak |

| Day | Thursday (hēméra Diós) |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Cronus and Rhea |

| Siblings | Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon and Demeter; Chiron (half) |

| Consort | Hera, various others |

| Children | Aeacus, Agdistis, Angelos, Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Britomartis, Dionysus, Eileithyia, Enyo, Epaphus Eris, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Heracles, Hermes, Lacedaemon, Melinoë, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Pollux, Rhadamanthus, Zagreus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Roman equivalent | Jupiter («Jovis» or «Iovis» in Latin) |

Zeus[a] (Ζεύς) is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus. His name is cognate with the first element of his Roman equivalent Jupiter.[4] His mythology and powers are similar, though not identical, to those of Indo-European deities such as Jupiter, Perkūnas, Perun, Indra, Dyaus, and Zojz.[5][6][7][8][9]

Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, the youngest of his siblings to be born, though sometimes reckoned the eldest as the others required disgorging from Cronus’s stomach. In most traditions, he is married to Hera, by whom he is usually said to have fathered Ares, Eileithyia, Hebe, and Hephaestus.[10][11] At the oracle of Dodona, his consort was said to be Dione,[12] by whom the Iliad states that he fathered Aphrodite.[15] According to the Theogony, Zeus’ first wife was Metis, by whom he had Athena.[16] Zeus was also infamous for his erotic escapades. These resulted in many divine and heroic offspring, including Apollo, Artemis, Hermes, Persephone, Dionysus, Perseus, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Minos, and the Muses.[10]

He was respected as an allfather who was chief of the gods[17] and assigned roles to the others:[18] «Even the gods who are not his natural children address him as Father, and all the gods rise in his presence.»[19][20] He was equated with many foreign weather gods, permitting Pausanias to observe «That Zeus is king in heaven is a saying common to all men».[21] Zeus’ symbols are the thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak. In addition to his Indo-European inheritance, the classical «cloud-gatherer» (Greek: Νεφεληγερέτα, Nephelēgereta)[22] also derives certain iconographic traits from the cultures of the ancient Near East, such as the scepter. Zeus is frequently depicted by Greek artists in one of three poses: standing, striding forward with a thunderbolt leveled in his raised right hand, or seated in majesty. It was very important for the lightning to be exclusively in the god’s right hand as the Greeks believed that people who were left-handed were associated with bad luck.

Name

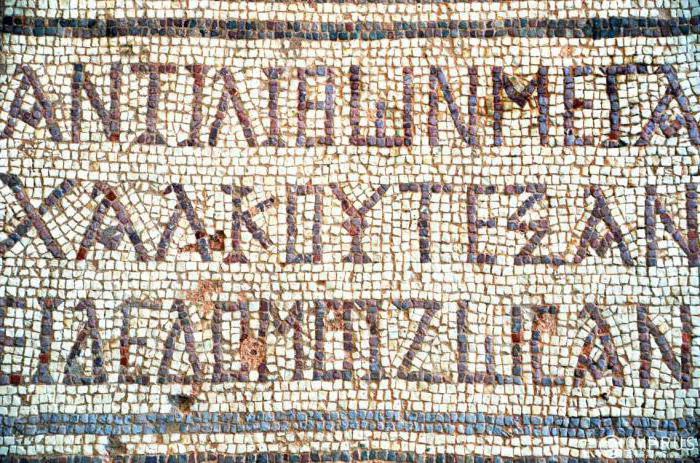

The god’s name in the nominative is Ζεύς (Zeús). It is inflected as follows: vocative: Ζεῦ (Zeû); accusative: Δία (Día); genitive: Διός (Diós); dative: Διί (Dií). Diogenes Laërtius quotes Pherecydes of Syros as spelling the name Ζάς.[23]

Zeus is the Greek continuation of *Di̯ēus, the name of the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, also called *Dyeus ph2tēr («Sky Father»).[24][25] The god is known under this name in the Rigveda (Vedic Sanskrit Dyaus/Dyaus Pita), Latin (compare Jupiter, from Iuppiter, deriving from the Proto-Indo-European vocative *dyeu-ph2tēr),[26] deriving from the root *dyeu— («to shine», and in its many derivatives, «sky, heaven, god»).[24] Albanian Zoj-z is also a cognate of Zeus. In both the Greek and Albanian forms the original cluster *di̯ underwent affrication to *dz.[9] Zeus is the only deity in the Olympic pantheon whose name has such a transparent Indo-European etymology.[27]

The earliest attested forms of the name are the Mycenaean Greek 𐀇𐀸, di-we and 𐀇𐀺, di-wo, written in the Linear B syllabic script.[28]

Plato, in his Cratylus, gives a folk etymology of Zeus meaning «cause of life always to all things», because of puns between alternate titles of Zeus (Zen and Dia) with the Greek words for life and «because of».[29] This etymology, along with Plato’s entire method of deriving etymologies, is not supported by modern scholarship.[30][31]

Diodorus Siculus wrote that Zeus was also called Zen, because the humans believed that he was the cause of life (zen).[32] While Lactantius wrote that he was called Zeus and Zen, not because he is the giver of life, but because he was the first who lived of the children of Cronus.[33]

Mythology

Birth

In Hesiod’s Theogony (c. 730 – 700 BC), Cronus, after castrating his father Uranus,[34] becomes the supreme ruler of the cosmos, and weds his sister Rhea, by whom he begets three daughters and three sons: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, Poseidon, and lastly, «wise» Zeus, the youngest of the six.[35] He swallows each child as soon as they are born, having received a prophecy from his parents, Gaia and Uranus, that one of his own children is destined to one day overthrow him as he overthrew his father.[36] This causes Rhea «unceasing grief»,[37] and upon becoming pregnant with her sixth child, Zeus, she approaches her parents, Gaia and Uranus, seeking a plan to save her child and bring retribution to Cronus.[38] Following her parents’ instructions, she travels to Lyctus in Crete, where she gives birth to Zeus,[39] handing the newborn child over to Gaia for her to raise, and Gaia takes him to a cave on Mount Aegaeon.[40] Rhea then gives to Cronus, in the place of a child, a stone wrapped in swaddling clothes, which he promptly swallows, unaware that it isn’t his son.[41]

While Hesiod gives Lyctus as Zeus’s birthplace, he is the only source to do so,[42] and other authors give different locations. The poet Eumelos of Corinth (8th century BC), according to John the Lydian, considered Zeus to have been born in Lydia,[43] while the Alexandrian poet Callimachus (c. 310 – c. 240 BC), in his Hymn to Zeus, says that he was born in Arcadia.[44] Diodorus Siculus (fl. 1st century BC) seems at one point to give Mount Ida as his birthplace, but later states he is born in Dicte,[45] and the mythographer Apollodorus (first or second century AD) similarly says he was born in a cave in Dicte.[46]

Infancy

While the Theogony says nothing of Zeus’s upbringing other than that he grew up swiftly,[47] other sources provide more detailed accounts.

According to Apollodorus, Rhea, after giving birth to Zeus in a cave in Dicte, gives him to the nymphs Adrasteia and Ida, daughters of Melisseus, to nurse.[48] They feed him on the milk of the she-goat Amalthea,[49] while the Kouretes guard the cave and beat their spears on their shields so that Cronus cannot hear the infant’s crying.[50] Diodorus Siculus provides a similar account, saying that, after giving birth, Rhea travels to Mount Ida and gives the newborn Zeus to the Kouretes,[51] who then takes him to some nymphs (not named), who raised him on a mixture of honey and milk from the goat Amalthea.[52] He also refers to the Kouretes «rais[ing] a great alarum», and in doing so deceiving Cronus,[53] and relates that when the Kouretes were carrying the newborn Zeus that the umbilical cord fell away at the river Triton.[54]

Hyginus, in his Fabulae, relates a version in which Cronus casts Poseidon into the sea and Hades to the Underworld instead of swallowing them. When Zeus is born, Hera (also not swallowed), asks Rhea to give her the young Zeus, and Rhea gives Cronus a stone to swallow.[55] Hera gives him to Amalthea, who hangs his cradle from a tree, where he isn’t in heaven, on earth or in the sea, meaning that when Cronus later goes looking for Zeus, he is unable to find him.[56] Hyginus also says that Ida, Althaea, and Adrasteia, usually considered the children of Oceanus, are sometimes called the daughters of Melisseus and the nurses of Zeus.[57]

According to a fragment of Epimenides, the nymphs Helike and Kynosura are the young Zeus’s nurses. Cronus travels to Crete to look for Zeus, who, to conceal his presence, transforms himself into a snake and his two nurses into bears.[58] According to Musaeus, after Zeus is born, Rhea gives him to Themis. Themis in turn gives him to Amalthea, who owns a she-goat, which nurses the young Zeus.[59]

Antoninus Liberalis, in his Metamorphoses, says that Rhea gives birth to Zeus in a sacred cave in Crete, full of sacred bees, which become the nurses of the infant. While the cave is considered forbidden ground for both mortals and gods, a group of thieves seek to steal honey from it. Upon laying eyes on the swaddling clothes of Zeus, their bronze armour «split[s] away from their bodies», and Zeus would have killed them had it not been for the intervention of the Moirai and Themis; he instead transforms them into various species of birds.[60]

Ascension to Power

1st century BC statue of Zeus[61]

According to the Theogony, after Zeus reaches manhood, Cronus is made to disgorge the five children and the stone «by the stratagems of Gaia, but also by the skills and strength of Zeus», presumably in reverse order, vomiting out the stone first, then each of the five children in the opposite order to swallowing.[62] Zeus then sets up the stone at Delphi, so that it may act as «a sign thenceforth and a marvel to mortal men».[63] Zeus next frees the Cyclopes, who, in return, and out of gratitude, give him his thunderbolt, which had previously been hidden by Gaia.[64] Then begins the Titanomachy, the war between the Olympians, led by Zeus, and the Titans, led by Cronus, for control of the universe, with Zeus and the Olympians fighting from Mount Olympus, and the Titans fighting from Mount Othrys.[65] The battle lasts for ten years with no clear victor emerging, until, upon Gaia’s advice, Zeus releases the Hundred-Handers, who (similarly to the Cyclopes) were imprisoned beneath the Earth’s surface.[66] He gives them nectar and ambrosia and revives their spirits,[67] and they agree to aid him in the war.[68] Zeus then launches his final attack on the Titans, hurling bolts of lightning upon them while the Hundred-Handers attack with barrages of rocks, and the Titans are finally defeated, with Zeus banishing them to Tartarus and assigning the Hundred-Handers the task of acting as their warders.[69]

Apollodorus provides a similar account, saying that, when Zeus reaches adulthood, he enlists the help of the Oceanid Metis, who gives Cronus an emetic, forcing to him to disgorge the stone and Zeus’s five siblings.[70] Zeus then fights a similar ten-year war against the Titans, until, upon the prophesying of Gaia, he releases the Cyclopes and Hundred-Handers from Tartarus, first slaying their warder, Campe.[71] The Cyclopes give him his thunderbolt, Poseidon his trident and Hades his helmet of invisibility, and the Titans are defeated and the Hundred-Handers made their guards.[72]

According to the Iliad, after the battle with the Titans, Zeus shares the world with his brothers, Poseidon and Hades, by drawing lots: Zeus receives the sky, Poseidon the sea, and Hades the underworld, with the earth and Olympus remaining common ground.[73]

Challenges to Power

Upon assuming his place as king of the cosmos, Zeus’ rule is quickly challenged. The first of these challenges to his power comes from the Giants, who fight the Olympian gods in a battle known as the Gigantomachy. According to Hesiod, the Giants are the offspring of Gaia, born from the drops of blood that fell on the ground when Cronus castrated his father Uranus;[74] there is, however, no mention of a battle between the gods and the Giants in the Theogony.[75] It is Apollodorus who provides the most complete account of the Gigantomachy. He says that Gaia, out of anger at how Zeus had imprisoned her children, the Titans, bore the Giants to Uranus.[76] There comes to the gods a prophecy that the Giants cannot be defeated by the gods on their own, but can be defeated only with the help of a mortal; Gaia, upon hearing of this, seeks a special pharmakon (herb) that will prevent the Giants from being killed. Zeus, however, orders Eos (Dawn), Selene (Moon) and Helios (Sun) to stop shining, and harvests all of the herb himself, before having Athena summon Heracles.[77] In the conflict, Porphyrion, one of the most powerful of the Giants, launches an attack upon Heracles and Hera; Zeus, however, causes Porphyrion to become lustful for Hera, and when he is just about to violate her, Zeus strikes him with his thunderbolt, before Heracles deals the fatal blow with an arrow.[78]

In the Theogony, after Zeus defeats the Titans and banishes them to Tartarus, his rule is challenged by the monster Typhon, a giant serpentine creature who battles Zeus for control of the cosmos. According to Hesiod, Typhon is the offspring of Gaia and Tartarus,[79] described as having a hundred snaky fire-breathing heads.[80] Hesiod says he «would have come to reign over mortals and immortals» had it not been for Zeus noticing the monster and dispatching with him quickly:[81] the two of them meet in a cataclysmic battle, before Zeus defeats him easily with his thunderbolt, and the creature is hurled down to Tartarus.[82] Epimenides presents a different version, in which Typhon makes his way into Zeus’s palace while he is sleeping, only for Zeus to wake and kill the monster with a thunderbolt.[83] Aeschylus and Pindar give somewhat similar accounts to Hesiod, in that Zeus overcomes Typhon with relative ease, defeating him with his thunderbolt.[84] Apollodorus, in contrast, provides a more complex narrative.[85] Typhon is, similarly to in Hesiod, the child of Gaia and Tartarus, produced out of anger at Zeus’s defeat of the Giants.[86] The monster attacks heaven, and all of the gods, out of fear, transform into animals and flee to Egypt, except for Zeus, who attacks the monster with his thunderbolt and sickle.[87] Typhon is wounded and retreats to Mount Kasios in Syria, where Zeus grapples with him, giving the monster a chance to wrap him in his coils, and rip out the sinews from his hands and feet.[88] Disabled, Zeus is taken by Typhon to the Corycian Cave in Cilicia, where he is guarded by the «she-dragon» Delphyne.[89] Hermes and Aegipan, however, steal back Zeus’s sinews, and refit them, reviving him and allowing him to return to the battle, pursuing Typhon, who flees to Mount Nysa; there, Typhon is given «ephemeral fruits» by the Moirai, which reduce his strength.[90] The monster then flees to Thrace, where he hurls mountains at Zeus, which are sent back at him by the god’s thunderbolts, before, while fleeing to Sicily, Zeus launches Mount Etna upon him, finally ending him.[91] Nonnus, who gives the most longest and most detailed account from antiquity, presents a narrative similar to Apollodorus, with differences such as that it is instead Cadmus and Pan who recovers Zeus’s sinews, by luring Typhon with music and then tricking him.[92]

In the Iliad, Homer tells of another attempted overthrow, in which Hera, Poseidon, and Athena conspire to overpower Zeus and tie him in bonds. It is only because of the Nereid Thetis, who summons Briareus, one of the Hecatoncheires, to Olympus, that the other Olympians abandon their plans (out of fear for Briareus).[93]

Seven wives of Zeus

Jupiter, disguised as a shepherd, tempts Mnemosyne by Jacob de Wit (1727)

According to Hesiod, Zeus had seven wives. His first wife was the Oceanid Metis, whom he swallowed on the advice of Gaia and Uranus, so that no son of his by Metis would overthrow him, as had been foretold. Later, their daughter Athena would be born from the forehead of Zeus.[16]

Zeus’s next marriage was to his aunt and advisor Themis, who bore the Horae (Seasons) and the Moirai (Fates).[94] Zeus then married the Oceanid Eurynome, who bore the three Charites (Graces).[95]

Zeus’s fourth wife was his sister, Demeter, who bore Persephone.[96] The fifth wife of Zeus was his aunt, the Titan Mnemosyne, whom he seduced in the form of a mortal shepherd. Zeus and Mnemosyne had the nine Muses.[97] His sixth wife was the Titan Leto, who gave birth to Apollo and Artemis on the island of Delos.[98]

Zeus’s seventh and final wife was his older sister Hera.[99]

| Children of Zeus and his seven wives [100] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Zeus and Hera

Main article: Hera

Wedding of Zeus and Hera on an antique fresco from Pompeii

Zeus was the brother and consort of Hera. According to Pausanias, Zeus had turned himself into a cuckoo to woo Hera.[105] By Hera, Zeus sired Ares, Hebe, Eileithyia and Hephaestus,[11] though some accounts say that Hera produced these offspring alone. Some also include Eris,[106] Enyo[107] and Angelos[108] as their daughters. In the section of the Iliad known to scholars as the Deception of Zeus, the two of them are described as having begun their sexual relationship without their parents knowing about it.[109]

According to a scholion on Theocritus’ Idylls, when Hera was heading toward Mount Thornax alone, Zeus created a terrible storm and transformed himself into a cuckoo bird who flew down and sat on her lap. When Hera saw the cuckoo, she felt pity for him and covered him with her cloak. Zeus then transformed back and took hold of her; because she was refusing to sleep with him due to their mother, he promised to marry her.[110] In one account Hera refused to marry Zeus and hid in a cave to avoid him; an earthborn man named Achilles convinced her to give him a chance, and thus the two had their first sexual intercourse. Zeus then promised Achilles that every person who bore his name shall become famous.[111]

A variation goes that Hera had been reared by a nymph named Macris on the island of Euboea, but Zeus stole her away, where Mt. Cithaeron, in the words of Plutarch, «afforded them a shady recess». When Macris came to look for her ward, the mountain-god Cithaeron drove her away, saying that Zeus was taking his pleasure there with Leto.[112]

According to Callimachus, their wedding feast lasted three thousand years.[113] The Apples of the Hesperides that Heracles was tasked by Eurystheus to take were a wedding gift by Gaia to the couple.[114]

Zeus mated with several nymphs and was seen as the father of many mythical mortal progenitors of Hellenic dynasties. Aside from his seven wives, relationships with immortals included Dione and Maia.[115][116] Among mortals were Semele, Io, Europa and Leda (for more details, see below) and with the young Ganymede (although he was mortal Zeus granted him eternal youth and immortality).

Many myths render Hera as jealous of his affairs and a consistent enemy of Zeus’ mistresses and their children by him. For a time, a nymph named Echo had the job of distracting Hera from his affairs by talking incessantly, and when Hera discovered the deception, she cursed Echo to repeat the words of others.[117]

According to Diodorus Siculus, Alcmene, the mother of Heracles, was the very last mortal woman Zeus ever slept with; following the birth of Heracles, he ceased to beget humans altogether, and fathered no more children.[118]

Prometheus and conflicts with humans

When the gods met at Mecone to discuss which portions they will receive after a sacrifice, the titan Prometheus decided to trick Zeus so that humans receive the better portions. He sacrificed a large ox, and divided it into two piles. In one pile he put all the meat and most of the fat, covering it with the ox’s grotesque stomach, while in the other pile, he dressed up the bones with fat. Prometheus then invited Zeus to choose; Zeus chose the pile of bones. This set a precedent for sacrifices, where humans will keep the fat for themselves and burn the bones for the gods.

Zeus, enraged at Prometheus’s deception, prohibited the use of fire by humans. Prometheus, however, stole fire from Olympus in a fennel stalk and gave it to humans. This further enraged Zeus, who punished Prometheus by binding him to a cliff, where an eagle constantly ate Prometheus’s liver, which regenerated every night. Prometheus was eventually freed from his misery by Heracles.[119]

Now Zeus, angry at humans, decides to give humanity a punishing gift to compensate for the boon they had been given. He commands Hephaestus to mold from earth the first woman, a «beautiful evil» whose descendants would torment the human race. After Hephaestus does so, several other gods contribute to her creation. Hermes names the woman ‘Pandora’.

Pandora was given in marriage to Prometheus’s brother Epimetheus. Zeus gave her a jar which contained many evils. Pandora opened the jar and released all the evils, which made mankind miserable. Only hope remained inside the jar.[120]

When Zeus was atop Mount Olympus he was appalled by human sacrifice and other signs of human decadence. He decided to wipe out mankind and flooded the world with the help of his brother Poseidon. After the flood, only Deucalion and Pyrrha remained.[121] This flood narrative is a common motif in mythology.[122]

The Chariot of Zeus, from an 1879 Stories from the Greek Tragedians by Alfred Church.

In the Iliad

Jupiter and Juno on Mount Ida by James Barry, 1773 (City Art Galleries, Sheffield.)

The Iliad is an ancient Greek epic poem attributed to Homer about the Trojan war and the battle over the City of Troy, in which Zeus plays a major part.

Scenes in which Zeus appears include:[123][124]

- Book 2: Zeus sends Agamemnon a dream and is able to partially control his decisions because of the effects of the dream

- Book 4: Zeus promises Hera to ultimately destroy the City of Troy at the end of the war

- Book 7: Zeus and Poseidon ruin the Achaeans fortress

- Book 8: Zeus prohibits the other Gods from fighting each other and has to return to Mount Ida where he can think over his decision that the Greeks will lose the war

- Book 14: Zeus is seduced by Hera and becomes distracted while she helps out the Greeks

- Book 15: Zeus wakes up and realizes that his own brother, Poseidon has been aiding the Greeks, while also sending Hector and Apollo to help fight the Trojans ensuring that the City of Troy will fall

- Book 16: Zeus is upset that he couldn’t help save Sarpedon’s life because it would then contradict his previous decisions

- Book 17: Zeus is emotionally hurt by the fate of Hector

- Book 20: Zeus lets the other Gods lend aid to their respective sides in the war

- Book 24: Zeus demands that Achilles release the corpse of Hector to be buried honourably

Other myths

Zeus slept with his great-granddaughter, Alcmene, disguised as her husband Amphitryon. This resulted in the birth of Heracles, who would be tormented by Zeus’s wife Hera for the rest of his life. After his death, Heracles’s mortal parts were incinerated and he joined the gods on Olympus. He married Zeus and Hera’s daughter, Hebe, and had two sons with her, Alexiares and Anicetus.[125]

When Hades requested to marry Zeus’s daughter, Persephone, Zeus approved and advised Hades to abduct Persephone, as her mother Demeter wouldn’t allow her to marry Hades.[126]

Zeus fell in love with Semele, the daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia, and started an affair with her. Hera discovered his affair when Semele later became pregnant, and persuaded Semele to sleep with Zeus in his true form. When Zeus showed his true form to Semele, his lightning and thunderbolts burned her to death.[127] Zeus saved the fetus by stitching it into his thigh, and the fetus would be born as Dionysus.[128]

In the Orphic «Rhapsodic Theogony» (first century BC/AD),[129] Zeus wanted to marry his mother Rhea. After Rhea refused to marry him, Zeus turned into a snake and raped her. Rhea became pregnant and gave birth to Persephone. Zeus in the form of a snake would mate with his daughter Persephone, which resulted in the birth of Dionysus.[130]

Zeus granted Callirrhoe’s prayer that her sons by Alcmaeon, Acarnan and Amphoterus, grow quickly so that they might be able to avenge the death of their father by the hands of Phegeus and his two sons.[131]

Both Zeus and Poseidon wooed Thetis, daughter of Nereus. But when Themis (or Prometheus) prophesied that the son born of Thetis would be mightier than his father, Thetis was married off to the mortal Peleus.[132][133]

Zeus was afraid that his grandson Asclepius would teach resurrection to humans, so he killed Asclepius with his thunderbolt. This angered Asclepius’s father, Apollo, who in turn killed the Cyclopes who had fashioned the thunderbolts of Zeus. Angered at this, Zeus would have imprisoned Apollo in Tartarus. However, at the request of Apollo’s mother, Leto, Zeus instead ordered Apollo to serve as a slave to King Admetus of Pherae for a year.[134] According to Diodorus Siculus, Zeus killed Asclepius because of complains from Hades, who was worried that the number of people in the underworld was diminishing because of Asclepius’s resurrections.[135]

The winged horse Pegasus carried the thunderbolts of Zeus.[136]

Zeus took pity on Ixion, a man who was guilty of murdering his father-in-law, by purifying him and bringing him to Olympus. However, Ixion started to lust after Hera. Hera complained about this to her husband, and Zeus decided to test Ixion. Zeus fashioned a cloud that resembles Hera (Nephele) and laid the cloud-Hera in Ixion’s bed. Ixion coupled with Nephele, resulting in the birth of Centaurus. Zeus punished Ixion for lusting after Hera by tying him to a wheel that spins forever.[137]

Once, Helios the sun god gave his chariot to his inexperienced son Phaethon to drive. Phaethon could not control his father’s steeds so he ended up taking the chariot too high, freezing the earth, or too low, burning everything to the ground. The earth itself prayed to Zeus, and in order to prevent further disaster, Zeus hurled a thunderbolt at Phaethon, killing him and saving the world from further harm.[138] In a satirical work, Dialogues of the Gods by Lucian, Zeus berates Helios for allowing such thing to happen; he returns the damaged chariot to him and warns him that if he dares do that again, he will strike him with one of this thunderbolts.[139]

Transformation of Zeus

| Love interest | Disguises |

|---|---|

| Aegina | an eagle or a flame of fire |

| Alcmene | Amphitryon[140] |

| Antiope | a satyr[141] |

| Asopis | a flame of fire |

| Callisto | Artemis[142] or Apollo[143] |

| Cassiopeia | Phoenix |

| Danaë | shower of gold[144] |

| Europa | a bull[145] |

| Eurymedusa | ant |

| Ganymede | an eagle[146] |

| Hera | a cuckoo[147] |

| Lamia | a lapwing |

| Leda | a swan[148] |

| Mnemosyne | a shepherd |

| Nemesis | a goose[149] |

| Persephone | a serpent[130] |

| Rhea | a serpent[130] |

| Semele | a fire |

| Thalia | a vulture |

| Manthaea | A bear[150] |

Children

| Offspring | Mother |

|---|---|

| Heracles | Alcmene[151] |

| Persephone | Demeter[152] |

| Charites (Aglaea, Euphrosyne, Thalia) | Eurynome[153] |

| Ares, Eileithyia, Hebe | Hera[154] |

| Apollo, Artemis | Leto[155] |

| Hermes | Maia[156] |

| Athena | Metis[157] |

| Muses (Calliope, Clio, Euterpe, Erato, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsichore, Thalia, Urania) | Mnemosyne[158] |

| Dionysus | Semele[159] |

| Horae (Dike, Eirene, Eunomia), Moirai (Atropos, Clotho, Lachesis) | Themis[160] |

| Offspring | Mother |

|---|---|

| Aegipan[161] | Aega, Aix or Boetis |

| Tyche[162] | Aphrodite |

| Hecate,[163] Heracles[164] | Asteria |

| Acragas[165] | Asterope |

| Corybantes[166] | Calliope |

| Coria (Athene)[167] | Coryphe |

| Dionysus[168] | Demeter |

| Aphrodite | Dione[169] |

| Charites (Aglaea, Euphrosyne, Thalia) | Euanthe or Eunomia[170] or Eurydome or Eurymedusa |

| Asopus[171] | Eurynome |

| Dodon[172] | Europa |

| Agdistis,[173] Manes,[174] Cyprian Centaurs[175] | Gaia |

| Angelos, Arge,[176] Eleutheria,[177] Enyo, Eris, Hephaestus[178] | Hera |

| Pan[179] | Hybris |

| Helen of Troy[180] | Nemesis |

| Melinoë, Zagreus,[181] Dionysus | Persephone |

| Persephone[182] | Rhea |

| Dionysus,[183] Ersa,[184] Nemea,[185] Nemean Lion, Pandia[186] | Selene |

| Persephone[187] | Styx |

| Palici[188] | Thalia |

| Aeacus,[189] Damocrateia[190] | Aegina |

| Amphion, Zethus | Antiope[191] |

| Targitaos[192] | Borysthenis |

| Arcas[193] | Callisto |

| Britomartis[194] | Carme |

| Dardanus,[195] Emathion,[196] Iasion or Eetion,[195] Harmonia[197] | Electra |

| Myrmidon[198] | Eurymedousa |

| Cronius, Spartaios, Cytus | Himalia[199] |

| Colaxes[200] | Hora |

| Cres[201] | Idaea |

| Epaphus, Keroessa[202] | Io |

| Sarpedon, Argus | Lardane[203] |

| Saon[204] | Nymphe |

| Meliteus[205] | Othreis |

| Offspring | Mother |

|---|---|

| Tantalus[206] | Plouto |

| Lacedaemon[207] | Taygete |

| Archas[208] | Themisto |

| Carius[209] | Torrhebia |

| Megarus[210] | Nymph Sithnid |

| Olenus[211] | Anaxithea |

| Aethlius or Endymion[212] | Calyce |

| Milye,[213] Solymus[214] | Chaldene |

| Perseus[215] | Danaë |

| Pirithous[216] | Dia |

| Tityos[217] | Elara |

| Minos,[218] Rhadamanthus,[219] Sarpedon,[220] | Europa |

| Arcesius | Euryodeia |

| Orchomenus | Hermippe[221] |

| Agamedes | Iocaste |

| Thebe,[222] Deucalion[176] | Iodame |

| Acheilus[223][224] | Lamia |

| Libyan Sibyl (Herophile)[225] | Lamia (daughter of Poseidon) |

| Sarpedon[226] | Laodamia |

| Helen of Troy, Pollux | Leda |

| Heracles[227] | Lysithoe |

| Locrus | Maera[228] |

| Argus, Pelasgus | Niobe[229] |

| Graecus,[230] Latinus[231] | Pandora |

| Achaeus[232] | Phthia |

| Aethlius,[233] Aetolus,[234] Opus[235] | Protogeneia |

| Hellen[236] | Pyrrha |

| Aegyptus,[222] Heracles[237] | Thebe |

| Magnes, Makednos | Thyia[238] |

| Aletheia, Ate,[239] Nysean,[240] Caerus, Eubuleus,[241] Litae,[242] various nymphs, Phasis,[243] Calabrus,[244] Geraestus, Taenarus, Corinthus,[245] Crinacus[246] | unknown mothers |

| Orion[247] | No mother |

Roles and epithets

Zeus played a dominant role, presiding over the Greek Olympian pantheon. He fathered many of the heroes and was featured in many of their local cults. Though the Homeric «cloud collector» was the god of the sky and thunder like his Near-Eastern counterparts, he was also the supreme cultural artifact; in some senses, he was the embodiment of Greek religious beliefs and the archetypal Greek deity.

Aside from local epithets that simply designated the deity as doing something random at some particular place, the epithets or titles applied to Zeus emphasized different aspects of his wide-ranging authority:

- Zeus Aegiduchos or Aegiochos: Usually taken as Zeus as the bearer of the Aegis, the divine shield with the head of Medusa across it,[249] although others derive it from «goat» (αἴξ) and okhē (οχή) in reference to Zeus’ nurse, the divine goat Amalthea.[250][251]

- Zeus Agoraeus (Αγοραιος): Zeus as patron of the marketplace (agora) and punisher of dishonest traders.

- Zeus Areius (Αρειος): either «warlike» or «the atoning one».

- Zeus Eleutherios (Ἐλευθέριος): «Zeus the freedom giver» a cult worshiped in Athens[252]

- Zeus Horkios: Zeus as keeper of oaths. Exposed liars were made to dedicate a votive statue to Zeus, often at the sanctuary at Olympia

- Zeus Olympios (Ολύμπιος): Zeus as king of the gods and patron of the Panhellenic Games at Olympia

- Zeus Panhellenios («Zeus of All the Greeks»): worshipped at Aeacus’s temple on Aegina

- Zeus Xenios (Ξένιος), Philoxenon, or Hospites: Zeus as the patron of hospitality (xenia) and guests, avenger of wrongs done to strangers

Additional names and epithets for Zeus are also:

A

- Abrettenus (Ἀβρεττηνός) or Abretanus: surname of Zeus in Mysia[253]

- Achad: one of his names in Syria.

- Acraeus (Ακραίος): his name at Smyrna. Acraea and Acraeus are also attributes given to various goddesses and gods whose temples were situated upon hills, such as Zeus, Hera, Aphrodite, Pallas, Artemis, and others

- Acrettenus: his name in Mysia.

- Adad: one of his names in Syria.

- Zeus Adados: A Hellenization of the Canaanite Hadad and Assyrian Adad, particularly his solar cult at Heliopolis[254]

- Adultus: from his being invoked by adults, on their marriage.

- Aleios (Ἄλειος), from «Helios» and perhaps connected to water as well.[255]

- Amboulios (Αμβουλιος, «Counsellor») or Latinized Ambulius[256]

- Apemius (Apemios, Απημιος): Zeus as the averter of ills

- Apomyius (Απομυιος): Zeus as one who dispels flies

- Aphesios (Αφεσιος; «Releasing (Rain)»)

- Argikeravnos (ἀργικέραυνος; «of the flashing bolt»).[257]

- Astrapios (ἀστραπαῖός; «Lightninger»): Zeus as a weather god

- Atabyrius (Ἀταβύριος): he was worshipped in Rhodes and took his name from the Mount Atabyrus on the island[258]

- Aithrios (Αἴθριος, «of the Clear Sky»).[257]

- Aitherios (Αἰθέριος, «of Aether»).[257]

B

- Basileus (Βασιλευς, «King, Chief, Ruler»)

- Bottiaeus/ Bottaios (Βοττιαίος, «of the Bottiaei»): Worshipped at Antioch[259] Libanius wrote that Alexander the Great founded the temple of Zeus Bottiaios, in the place where later the city of Antioch was built.[260][261]

- Zeus Bouleus/ Boulaios (Βουλαίος, «of the Council»): Worshipped at Dodona, the earliest oracle, along with Zeus Naos

- Brontios and Brontaios (Βρονταῖος, «Thunderer»): Zeus as a weather god

C

- Cenaean (Kenaios/ Kenaius, Κηναῖος): a surname of Zeus, derived from cape Cenaeum[262][256]

- Chthonios (Χθόνιος, «of the earth or underworld»)[257]

D

- Diktaios (Δικταιος): Zeus as lord of the Dikte mountain range, worshipped from Mycenaean times on Crete[263]

- Dodonian/ Dodonaios (Δωδωναῖος): meaning of Dodona[264]

- Dylsios (Δύλσιος)[265]

E

- Eilapinastes (Εἰλαπιναστής, «Feaster»). He was worshipped in Cyprus.[266][267]

- Epikarpios (ἐπικάρπιος, «of the fruits»).[257]

- Eleutherios (Ἐλευθέριος, «of freedom»). At Athens after the Battle of Plataea, Athenians built the Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios.[268] Some writers said that was called «of freedom» because free men built the portico near his shrine, while others because Athenians escaped subjection to the power of Persia and they were free.[269]

- Epidôtês/ Epidotes (Επιδωτης; «Giver of Good»): an epithet of Zeus at Mantineia and Sparta

- Euênemos/ Euanemos (Ευηνεμος; «of Fair Winds», «Giver of Favourable Wind») or Latinized Evenemus/ Evanemus[256]

G

- Genethlios (Γενέθλιός; «of birth»).[257]

- Zeus Georgos (Ζεὺς Γεωργός, «Zeus the Farmer»): Zeus as god of crops and the harvest, worshipped in Athens

H

- Zeus Helioupolites («Heliopolite» or «Heliopolitan Zeus»): A Hellenization of the Canaanite Baʿal (probably Hadad) worshipped as a sun god at Heliopolis (modern Baalbek)[254] in Syria

- Herkeios (Ἑρκειος, «of the Courtyard») or Latinized Herceius

- Hecalesius, a festival named Hecalesia (Εκαλήσια) was celebrated at Athens in honour of Zeus Hecalesius and Hecale.[270]

- Hetareios (Ἑταιρεῖος, «of fellowship»): According to the Suda, Zeus was called this among the Cretans.[271]

- Hikesios (Ἱκεσιος; «of Suppliants») or Latinized Hicesius

- Homognios (ὁμόγνιος; «of kindred»)[257]

- Hyetios (Ὑετιος; «of the Rain»)

- Hypatos (Ὑπατος, «Supreme, Most High»)[256]

- Hypsistos (Ὕψιστος, «Supreme, Most High»)

I

- Idaeus or Idaios (Ἰδαῖος), of mount Ida. Either Mount Ida in Crete or Mount Ida in the ancient Troad[272]

- Ikmaios (Ικμαιος; «of Moisture») or Latinized Icmaeus

- Ithomatas (Ιθωμάτας), an annual festival celebrated at Ithome for Zeus Ithomatas.[256][273]

K

- Zeus Kasios («Zeus of Mount Kasios» the modern Jebel Aqra) or Latinized Casius: a surname of Zeus, the name may have derived from either sources, one derived from Casion, near Pelusium in Egypt. Another derived from Mount Kasios (Casius), which is the modern Jebel Aqra, is worshipped at a site on the Syrian–Turkish border, a Hellenization of the Canaanite mountain and weather god Baal Zephon

- Kataibates (Καταιβάτης, «descending») or Latinized Cataebates, because he was sending-down thunderbolts or because he was descending to earth due to his love of women.[274]

- Katharsios (Καθάρσιος, «purifying»).[257]

- Keraunios (Κεραυνιος; «of the Thunderbolt») or Latinized Ceraunius

- Klarios (Κλαριος; «of the Lots») or Latinized Clarius[256]

- Konios (Κονιος; «of the Dust») or Latinized Conius[256]

- Koryphaios (Κορυφαιος, «Chief, Leader») or Latinized Coryphaeus[256]

- Kosmêtês (Κοσμητης; «Orderer») or Latinized Cosmetes

- Ktesios (Κτησιος, «of the House, Property») or Latinized Ctesius[256]

L

- Zeus Labrandos (Λαβρανδευς; «Furious, Raging», «Zeus of Labraunda»): Worshiped at Caria, depicted with a double-edged axe (labrys), a Hellenization of the Hurrian weather god Teshub

- Laphystius («of Laphystium»), Laphystium was a mountain in Boeotia on which there was a temple to Zeus.[275]

- Limenoskopos (Λιμενοσκοπος; «Watcher of Sea-Havens») or Latinized Limenoscopus occurs as a surname of several deities, Zeus, Artemis, Aphrodite, Priapus and Pan

- Lepsinos, there is a temple of Zeus Lepsinos at Euromus.[276]

- Leukaios (Λευκαῖος Ζεύς; «Zeus of the white poplar»)[277]

M

- Maimaktês (Μαιμακτης; «Boisterous», «the Stormy») or Latinized Maemactes, a surname of Zeus, derived from the Attic calendar month name ‘Maimakterion’ (Μαιμακτηριών, Latinized Maemacterion) and which that month the Maimakteria was celebrated at Athens

- Zeus Meilichios/ Meilikhios (Μειλίχιος; «Zeus the Easily-Entreated»)[256] There was a sanctuary south of the Ilissos river at Athens.[278]

- Mêkhaneus (Μηχανευς; «Contriver») or Latinized Mechaneus[256]

- Moiragetes (Μοιραγέτης; «Leader of the Fates», «Guide or Leade of Fate»): Pausanias wrote that this was a surname of Zeus and Apollo at Delphi, because Zeus knew the affairs of men, all that the Fates give them and all that is not destined for them.[279]

N

- Zeus Naos: Worshipped at Dodona, the earliest oracle, along with Zeus Bouleus

O

- Ombrios (Ομβριος; «of the Rain», «Rain-Giver»)[256]

- Ouranios (Οὐράνιος, «Heavenly»).[257]

- Ourios (Οὐριος, «of Favourable Wind»). Ancient writers wrote about a sanctuary at the opening of the Black Sea dedicated to the Zeus Ourios (ἱερὸν τοῦ Διὸς τοῦ Οὐρίου).[280] In addition, on the island of Delos a dedication to Zeus Ourios was found. The dedication was made by a citizen of Ascalon, named Damon son of Demetrius, who escaped from pirates.[281]

P

- Palaimnios (Παλαμναῖος; «of Vengeance»)[257]

- Panamaros (Πανάμαρος; «of the city of Panamara»): there was an important sanctuary of Zeus Panamaros at the city of Panamara in Caria[282][283]

- Pankrates (Πανκρατής; «the almighty»)[284]

- Patrios (Πάτριος; «paternal»)[257]

- Phratrios (Φράτριος), as patron of a phratry[285]

- Philios (Φιλιος; «of Friendship») or Latinized Philius

- Phyxios (Φυξιος; «of Refuge») or Latinized Phyxius[256]

- Plousios (Πλουσιος; «of Wealth») or Latinized Plusius

- Polieus (Πολιεὺς; «from cities (poleis»).[257]

S

- Skotitas (Σκοτιτας; «Dark, Murky») or Latinized Scotitas

- Sêmaleos (Σημαλεος; «Giver of Signs») or Latinized Semaleus:

- Sosipolis (Σωσίπολις; «City saviour»): There was a temple of Zeus Sosipolis at Magnesia on the Maeander[286]

- Splanchnotomus («Entrails cutter»), he was worshipped in Cyprus.[266]

- Stratios (Στράτιος; «Of armies»). [257]

T

- Zeus Tallaios («Solar Zeus»): Worshipped on Crete

- Teleios (Τελειος; «of Marriage Rites») or Latinized Teleus

- Theos Agathos (Θεος Αγαθος; «the Good God») or Latinized Theus Agathus

- Tropaioukhos/ Tropaiuchos (τροπαιοῦχος, «Guardian of Trophies»):[257] after the Battle of the 300 Champions, Othryades, dedicated the trophy to «Zeus, Guardian of Trophies» .[287]

X

- Xenios (Ξενιος; «of Hospitality, Strangers») or Latinized Xenius[256]

Z

- Zygius (Ζυγίος): As the presider over marriage. His wife Hera had also the epithet Zygia (Ζυγία). These epithets describing them as presiding over marriage.[288]

Cults of Zeus

Panhellenic cults

The major center where all Greeks converged to pay honor to their chief god was Olympia. Their quadrennial festival featured the famous Games. There was also an altar to Zeus made not of stone, but of ash, from the accumulated remains of many centuries’ worth of animals sacrificed there.

Outside of the major inter-polis sanctuaries, there were no modes of worshipping Zeus precisely shared across the Greek world. Most of the titles listed below, for instance, could be found at any number of Greek temples from Asia Minor to Sicily. Certain modes of ritual were held in common as well: sacrificing a white animal over a raised altar, for instance.

Zeus Velchanos

With one exception, Greeks were unanimous in recognizing the birthplace of Zeus as Crete. Minoan culture contributed many essentials of ancient Greek religion: «by a hundred channels the old civilization emptied itself into the new», Will Durant observed,[290] and Cretan Zeus retained his youthful Minoan features. The local child of the Great Mother, «a small and inferior deity who took the roles of son and consort»,[291] whose Minoan name the Greeks Hellenized as Velchanos, was in time assumed as an epithet by Zeus, as transpired at many other sites, and he came to be venerated in Crete as Zeus Velchanos («boy-Zeus»), often simply the Kouros.

In Crete, Zeus was worshipped at a number of caves at Knossos, Ida and Palaikastro. In the Hellenistic period a small sanctuary dedicated to Zeus Velchanos was founded at the Hagia Triada site of a long-ruined Minoan palace. Broadly contemporary coins from Phaistos show the form under which he was worshiped: a youth sits among the branches of a tree, with a cockerel on his knees.[292] On other Cretan coins Velchanos is represented as an eagle and in association with a goddess celebrating a mystic marriage.[293] Inscriptions at Gortyn and Lyttos record a Velchania festival, showing that Velchanios was still widely venerated in Hellenistic Crete.[294]

The stories of Minos and Epimenides suggest that these caves were once used for incubatory divination by kings and priests. The dramatic setting of Plato’s Laws is along the pilgrimage-route to one such site, emphasizing archaic Cretan knowledge. On Crete, Zeus was represented in art as a long-haired youth rather than a mature adult and hymned as ho megas kouros, «the great youth». Ivory statuettes of the «Divine Boy» were unearthed near the Labyrinth at Knossos by Sir Arthur Evans.[295] With the Kouretes, a band of ecstatic armed dancers, he presided over the rigorous military-athletic training and secret rites of the Cretan paideia.

The myth of the death of Cretan Zeus, localised in numerous mountain sites though only mentioned in a comparatively late source, Callimachus,[296] together with the assertion of Antoninus Liberalis that a fire shone forth annually from the birth-cave the infant shared with a mythic swarm of bees, suggests that Velchanos had been an annual vegetative spirit.[297]

The Hellenistic writer Euhemerus apparently proposed a theory that Zeus had actually been a great king of Crete and that posthumously, his glory had slowly turned him into a deity. The works of Euhemerus himself have not survived, but Christian patristic writers took up the suggestion.

Zeus Lykaios

Further information: Lykaia

The epithet Zeus Lykaios (Λύκαιος; «wolf-Zeus») is assumed by Zeus only in connection with the archaic festival of the Lykaia on the slopes of Mount Lykaion («Wolf Mountain»), the tallest peak in rustic Arcadia; Zeus had only a formal connection[298] with the rituals and myths of this primitive rite of passage with an ancient threat of cannibalism and the possibility of a werewolf transformation for the ephebes who were the participants.[299] Near the ancient ash-heap where the sacrifices took place[300] was a forbidden precinct in which, allegedly, no shadows were ever cast.[301]

According to Plato,[302] a particular clan would gather on the mountain to make a sacrifice every nine years to Zeus Lykaios, and a single morsel of human entrails would be intermingled with the animal’s. Whoever ate the human flesh was said to turn into a wolf, and could only regain human form if he did not eat again of human flesh until the next nine-year cycle had ended. There were games associated with the Lykaia, removed in the fourth century to the first urbanization of Arcadia, Megalopolis; there the major temple was dedicated to Zeus Lykaios.

There is, however, the crucial detail that Lykaios or Lykeios (epithets of Zeus and Apollo) may derive from Proto-Greek *λύκη, «light», a noun still attested in compounds such as ἀμφιλύκη, «twilight», λυκάβας, «year» (lit. «light’s course») etc. This, Cook argues, brings indeed much new ‘light’ to the matter as Achaeus, the contemporary tragedian of Sophocles, spoke of Zeus Lykaios as «starry-eyed», and this Zeus Lykaios may just be the Arcadian Zeus, son of Aether, described by Cicero. Again under this new signification may be seen Pausanias’ descriptions of Lykosoura being ‘the first city that ever the sun beheld’, and of the altar of Zeus, at the summit of Mount Lykaion, before which stood two columns bearing gilded eagles and ‘facing the sun-rise’. Further Cook sees only the tale of Zeus’ sacred precinct at Mount Lykaion allowing no shadows referring to Zeus as ‘god of light’ (Lykaios).[303]

A statue of Zeus in a drawing.

Additional cults of Zeus

Although etymology indicates that Zeus was originally a sky god, many Greek cities honored a local Zeus who lived underground. Athenians and Sicilians honored Zeus Meilichios (Μειλίχιος; «kindly» or «honeyed») while other cities had Zeus Chthonios («earthy»), Zeus Katachthonios (Καταχθόνιος; «under-the-earth») and Zeus Plousios («wealth-bringing»). These deities might be represented as snakes or in human form in visual art, or, for emphasis as both together in one image. They also received offerings of black animal victims sacrificed into sunken pits, as did chthonic deities like Persephone and Demeter, and also the heroes at their tombs. Olympian gods, by contrast, usually received white victims sacrificed upon raised altars.

In some cases, cities were not entirely sure whether the daimon to whom they sacrificed was a hero or an underground Zeus. Thus the shrine at Lebadaea in Boeotia might belong to the hero Trophonius or to Zeus Trephonius («the nurturing»), depending on whether you believe Pausanias, or Strabo. The hero Amphiaraus was honored as Zeus Amphiaraus at Oropus outside of Thebes, and the Spartans even had a shrine to Zeus Agamemnon. Ancient Molossian kings sacrificed to Zeus Areius (Αρειος). Strabo mention that at Tralles there was the Zeus Larisaeus (Λαρισαιος).[304] In Ithome, they honored the Zeus Ithomatas, they had a sanctuary and a statue of Zeus and also held an annual festival in honour of Zeus which was called Ithomaea (ἰθώμαια).[305]

Hecatomphonia

Hecatomphonia (Ancient Greek: ἑκατομφόνια), meaning killing of a hundred, from ἑκατόν “a hundred” and φονεύω “to kill”. It was a custom of Messenians, at which they offered sacrifice to Zeus when any of them had killed a hundred enemies. Aristomenes have offered three times this sacrifice at the Messenian wars against Sparta.[306][307][308][309]

Non-panhellenic cults

In addition to the Panhellenic titles and conceptions listed above, local cults maintained their own idiosyncratic ideas about the king of gods and men. With the epithet Zeus Aetnaeus he was worshiped on Mount Aetna, where there was a statue of him, and a local festival called the Aetnaea in his honor.[310] Other examples are listed below. As Zeus Aeneius or Zeus Aenesius (Αινησιος), he was worshiped in the island of Cephalonia, where he had a temple on Mount Aenos.[311]

Oracles of Zeus

Although most oracle sites were usually dedicated to Apollo, the heroes, or various goddesses like Themis, a few oracular sites were dedicated to Zeus. In addition, some foreign oracles, such as Baʿal’s at Heliopolis, were associated with Zeus in Greek or Jupiter in Latin.

The Oracle at Dodona

The cult of Zeus at Dodona in Epirus, where there is evidence of religious activity from the second millennium BC onward, centered on a sacred oak. When the Odyssey was composed (circa 750 BC), divination was done there by barefoot priests called Selloi, who lay on the ground and observed the rustling of the leaves and branches.[312] By the time Herodotus wrote about Dodona, female priestesses called peleiades («doves») had replaced the male priests.

Zeus’ consort at Dodona was not Hera, but the goddess Dione — whose name is a feminine form of «Zeus». Her status as a titaness suggests to some that she may have been a more powerful pre-Hellenic deity, and perhaps the original occupant of the oracle.

The Oracle at Siwa

The oracle of Ammon at the Siwa Oasis in the Western Desert of Egypt did not lie within the bounds of the Greek world before Alexander’s day, but it already loomed large in the Greek mind during the archaic era: Herodotus mentions consultations with Zeus Ammon in his account of the Persian War. Zeus Ammon was especially favored at Sparta, where a temple to him existed by the time of the Peloponnesian War.[313]

After Alexander made a trek into the desert to consult the oracle at Siwa, the figure arose in the Hellenistic imagination of a Libyan Sibyl.

Zeus and foreign gods

Zeus was identified with the Roman god Jupiter and associated in the syncretic classical imagination (see interpretatio graeca) with various other deities, such as the Egyptian Ammon and the Etruscan Tinia. He, along with Dionysus, absorbed the role of the chief Phrygian god Sabazios in the syncretic deity known in Rome as Sabazius. The Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes erected a statue of Zeus Olympios in the Judean Temple in Jerusalem.[315] Hellenizing Jews referred to this statue as Baal Shamen (in English, Lord of Heaven).[316]

Zeus is also identified with the Hindu deity Indra. Not only they are the king of gods, but their weapon — thunder is similar.[317]

Zeus and the sun

Zeus is occasionally conflated with the Hellenic sun god, Helios, who is sometimes either directly referred to as Zeus’ eye,[318] or clearly implied as such. Hesiod, for instance, describes Zeus’ eye as effectively the sun.[319] This perception is possibly derived from earlier Proto-Indo-European religion, in which the sun is occasionally envisioned as the eye of *Dyḗus Pḥatḗr (see Hvare-khshaeta).[320] Euripides in his now lost tragedy Mysians described Zeus as «sun-eyed», and Helios is said elsewhere to be «the brilliant eye of Zeus, giver of life».[321] In another of Euripides’ tragedies, Medea, the chorus refers to Helios as «light born from Zeus.»[322]

Although the connection of Helios to Zeus does not seem to have basis in early Greek cult and writings, nevertheless there are many examples of direct identification in later times.[323] The Hellenistic period gave birth to Serapis, a Greco-Egyptian deity conceived as a chthonic avatar of Zeus, whose solar nature is indicated by the sun crown and rays the Greeks depicted him with.[324] Frequent joint dedications to «Zeus-Serapis-Helios» have been found all over the Mediterranean,[324] for example, the Anastasy papyrus (now housed in the British Museum equates Helios to not just Zeus and Serapis but also Mithras,[325] and a series of inscriptions from Trachonitis give evidence of the cult of «Zeus the Unconquered Sun».[326] There is evidence of Zeus being worshipped as a solar god in the Aegean island of Amorgos, based on a lacunose inscription Ζεὺς Ἥλ[ιο]ς («Zeus the Sun»), meaning sun elements of Zeus’ worship could be as early as the fifth century BC.[327]

The Cretan Zeus Tallaios had solar elements to his cult. «Talos» was the local equivalent of Helios.[328]

Zeus in philosophy

In Neoplatonism, Zeus’ relation to the gods familiar from mythology is taught as the Demiurge or Divine Mind, specifically within Plotinus’s work the Enneads[329] and the Platonic Theology of Proclus.

Zeus in the Bible

Zeus is mentioned in the New Testament twice, first in Acts 14:8–13: When the people living in Lystra saw the Apostle Paul heal a lame man, they considered Paul and his partner Barnabas to be gods, identifying Paul with Hermes and Barnabas with Zeus, even trying to offer them sacrifices with the crowd. Two ancient inscriptions discovered in 1909 near Lystra testify to the worship of these two gods in that city.[330] One of the inscriptions refers to the «priests of Zeus», and the other mentions «Hermes Most Great» and «Zeus the sun-god».[331]

The second occurrence is in Acts 28:11: the name of the ship in which the prisoner Paul set sail from the island of Malta bore the figurehead «Sons of Zeus» aka Castor and Pollux (Dioscuri).

The deuterocanonical book of 2 Maccabees 6:1, 2 talks of King Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), who in his attempt to stamp out the Jewish religion, directed that the temple at Jerusalem be profaned and rededicated to Zeus (Jupiter Olympius).[332]

Zeus in Gnostic literature

Pistis Sophia, a Gnostic text discovered in 1773 and possibly written between the 3rd and 4th centuries AD alludes to Zeus. He appears there as one of five grand rulers gathered together by a divine figure named Yew.[333]

In modern culture

Film

Zeus was portrayed by Axel Ringvall in Jupiter på jorden, the first known film adaption to feature Zeus; Niall MacGinnis in Jason and the Argonauts[334][335] and Angus MacFadyen in the 2000 remake;[336] Laurence Olivier in the original Clash of the Titans,[337] and Liam Neeson in the 2010 remake,[338] along with the 2012 sequel Wrath of the Titans;[339][340] Rip Torn in the Disney animated feature Hercules,[341] Sean Bean in Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010).[342] Russell Crowe portrays a character based on Zeus in Marvel Studios’ Thor: Love and Thunder (2022).

TV series

Zeus was portrayed by Anthony Quinn in the 1990s TV series Hercules: The Legendary Journeys; Corey Burton in the TV series Hercules; Hakeem Kae-Kazim in Troy: Fall of a City; and Jason O’Mara in the Netflix animated series Blood of Zeus.[343]

Video games

Zeus has been portrayed by Corey Burton in God of War II, God of War III, God of War: Ascension, PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale & Kingdom Hearts 3[344][345] and Eric Newsome in Dota 2. Zeus is also featured in the 2002 Ensemble Studios game Age of Mythology where he is one of 12 gods that can be worshipped by Greek players.[346][347]

Other

Depictions of Zeus as a bull, the form he took when abducting Europa, are found on the Greek 2-euro coin and on the United Kingdom identity card for visa holders. Mary Beard, professor of Classics at Cambridge University, has criticised this for its apparent celebration of rape.[348] A character based on the god was adapted by Marvel Comics creators Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, first appearing in 1949.

Genealogy of the Olympians

| Olympians’ family tree [349] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Argive genealogy

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colour key:

Male |

Gallery

-

The abduction of Europa

-

Olympian assembly, from left to right: Apollo, Zeus and Hera

-

The «Golden Man» Zeus statue

-

Enthroned Zeus (Greek, c. 100 BC) — modeled after the Olympian Zeus by Pheidas (c. 430 BC)

-

Zeus and Hera

-

Zeus statue

-

Zeus/Poseidon statue

See also

- Family tree of the Greek gods

- Agetor

- Ambulia – Spartan epithet used for Athena, Zeus, and Castor and Pollux

- Hetairideia – Thessalian Festival to Zeus

- Temple of Zeus, Olympia

- Zanes of Olympia – Statues of Zeus

Footnotes

- ^ British English ;[2] American English [3]

Attic–Ionic Greek: Ζεύς, romanized: Zeús Attic–Ionic pronunciation: [zděu̯s] or [dzěu̯s], Koine Greek pronunciation: [zeʍs], Modern Greek pronunciation: [zefs]; genitive: Δῐός, romanized: Diós [di.ós]

Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian Doric Greek: Δεύς, romanized: Deús Doric Greek: [děu̯s]; genitive: Δέος, romanized: Déos [dé.os]

Greek: Δίας, romanized: Días Modern Greek: [ˈði.as̠]

Notes

- ^ The sculpture was presented to Louis XIV as Aesculapius but restored as Zeus, ca. 1686, by Pierre Granier, who added the upraised right arm brandishing the thunderbolt. Marble, middle 2nd century CE. Formerly in the ‘Allée Royale’, (Tapis Vert) in the Gardens of Versailles, now conserved in the Louvre Museum (Official on-line catalog)

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. «Zeus, n.» Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1921.

- ^ Zeus in the American Heritage Dictionary

- ^ Larousse Desk Reference Encyclopedia, The Book People, Haydock, 1995, p. 215.

- ^ Thomas Berry (1996). Religions of India: Hinduism, Yoga, Buddhism. Columbia University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-231-10781-5.

- ^ T. N. Madan (2003). The Hinduism Omnibus. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-566411-9.

- ^ Sukumari Bhattacharji (2015). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–281.

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. ISBN 9788184752779. Entry: «Dyaus»

- ^ a b Hyllested, Adam; Joseph, Brian D. (2022). «Albanian». In Olander, Thomas (ed.). The Indo-European Language Family : A Phylogenetic Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 232. doi:10.1017/9781108758666. ISBN 9781108758666. S2CID 161016819.

- ^ a b Hamilton, Edith (1942). Mythology (1998 ed.). New York: Back Bay Books. p. 467. ISBN 978-0-316-34114-1.

- ^ a b Hard 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Brill’s New Pauly, s.v. Zeus.

- ^ Homer, Il., Book V.

- ^ Plato, Symp., 180e.

- ^ There are two major conflicting stories for Aphrodite’s origins: Hesiod’s Theogony claims that she was born from the foam of the sea after Cronos castrated Uranus, making her Uranus’s daughter, while Homer’s Iliad has Aphrodite as the daughter of Zeus and Dione.[13] A speaker in Plato’s Symposium offers that they were separate figures: Aphrodite Ourania and Aphrodite Pandemos.[14]

- ^ a b Hesiod, Theogony 886–900.

- ^ Homeric Hymns.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony.

- ^ Burkert, Greek Religion.

- ^ See, e.g., Homer, Il., I.503 & 533.

- ^ Pausanias, 2.24.4.

- ^ Νεφεληγερέτα. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Laërtius, Diogenes (1972) [1925]. «1.11». In Hicks, R.D. (ed.). Lives of Eminent Philosophers. «1.11». Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers (in Greek).

- ^ a b «Zeus». American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved 3 July 2006.

- ^ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 499.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. «Jupiter». Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Burkert (1985). Greek Religion. p. 321. ISBN 0-674-36280-2.

- ^ «The Linear B word di-we». «The Linear B word di-wo». Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of Ancient languages.

- ^ «Plato’s Cratylus« by Plato, ed. by David Sedley, Cambridge University Press, 6 November 2003, p. 91

- ^ Jevons, Frank Byron (1903). The Makers of Hellas. C. Griffin, Limited. pp. 554–555.

- ^ Joseph, John Earl (2000). Limiting the Arbitrary. ISBN 1556197497.

- ^ «Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, Books I-V, book 5, chapter 72». www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Lactantius, Divine Institutes 1.11.1.

- ^ See Gantz, pp. 10–11; Hesiod, Theogony 159–83.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 67; Hansen, p. 67; Tripp, s.v. Zeus, p. 605; Caldwell, p. 9, table 12; Hesiod, Theogony 453–8. So too Apollodorus, 1.1.5; Diodorus Siculus, 68.1.

- ^ Gantz, p. 41; Hard 2004, p. 67–8; Grimal, s.v. Zeus, p. 467; Hesiod, Theogony 459–67. Compare with Apollodorus, 1.1.5, who gives a similar account, and Diodorus Siculus, 70.1–2, who doesn’t mention Cronus’ parents, but rather says that it was an oracle who gave the prophecy.

- ^ Cf. Apollodorus, 1.1.6, who says that Rhea was «enraged».

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Gantz, p. 41; Smith, s.v. Zeus; Hesiod, Theogony 468–73.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 74; Gantz, p. 41; Hesiod, Theogony 474–9.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 74; Hesiod, Theogony 479–84. According to Hard 2004, the «otherwise unknown» Mount Aegaeon can «presumably … be identified with one of the various mountains near Lyktos».

- ^ Hansen, p. 67; Hard 2004, p. 68; Smith, s.v. Zeus; Gantz, p. 41; Hesiod, Theogony 485–91. For iconographic representations of this scene, see Louvre G 366; Clark, p. 20, figure 2.1 and Metropolitan Museum of Art 06.1021.144; LIMC 15641; Beazley Archive 214648. According to Pausanias, 9.41.6, this event occurs at Petrachus, a «crag» nearby to Chaeronea (see West 1966, p. 301 on line 485).

- ^ West 1966, p. 291 on lines 453–506; Hard 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Fowler 2013, pp. 35, 50; Eumelus fr. 2 West, pp. 224, 225 [= fr. 10 Fowler, p. 109 = PEG fr. 18 (Bernabé, p. 114) = Lydus, De Mensibus 4.71]. According to West 2003, p. 225 n. 3, in this version he was born «probably on Mt. Sipylos».

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 391; Grimal, s.v. Zeus, p. 467; Callimachus, Hymn to Zeus (1) 4–11 (pp. 36–9).

- ^ Fowler 2013, p. 391; Diodorus Siculus, 70.2, 70.6.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.1.6.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Gantz, p. 41; Hesiod, Theogony 492–3: «the strength and glorious limbs of the prince increased quickly».

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.1.6; Gantz, p. 42; West 1983, p. 133.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 612 n. 53 to p. 75; Apollodorus, 1.1.7.

- ^ Hansen, p. 216; Apollodorus, 1.1.7.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 7.70.2; see also 7.65.4.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 7.70.2–3.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 7.65.4.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, 7.70.4.

- ^ Gantz, p. 42; Hyginus, Fabulae 139.

- ^ Gantz, p. 42; Hard 2004, p. 75; Hyginus, Fabulae 139.

- ^ Smith and Trzaskoma, p. 191 on line 182; West 1983, p. 133 n. 40; Hyginus, Fabulae 182 (Smith and Trzaskoma, p. 158).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 75–6; Gantz, p. 42; Epimenides fr. 23 Diels, p. 193 [= Scholia on Aratus, 46]. Zeus later marks the event by placing the constellations of the Dragon, the Greater Bear and the Lesser Bear in the sky.

- ^ Gantz, p. 41; Gee, p. 131–2; Frazer, p. 120; Musaeus fr. 8 Diels, pp. 181–2 [= Eratosthenes, Catasterismi 13 (Hard 2015, p. 44; Olivieri, p. 17)]; Musaeus apud Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.13.6. According to Eratosthenes, Musaeus considers the she-goat to be a child of Helios, and to be «so terrifying to behold» that the gods ask for it to be hidden in one of the caves in Crete; hence Earth places it in the care of Amalthea, who nurses Zeus on its milk.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 75; Antoninus Liberalis, 19.

- ^ J. Paul Getty Museum 73.AA.32.

- ^ Gantz, p. 44; Hard 2004, p. 68; Hesiod, Theogony 492–7.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Hesiod, Theogony 498–500.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Gantz, p. 44; Hesiod, Theogony 501–6. The Cyclopes presumably remained trapped below the earth since being put there by Uranus (Hard 2004, p. 68).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Gantz, p. 45; Hesiod, Theogony 630–4.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 68; Hesiod, Theogony 624–9, 635–8. As Gantz, p. 45 notes, the Theogony is ambiguous as to whether the Hundred-Handers were freed before the war or only during its tenth year.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 639–53.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 654–63.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 687–735.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 69; Gantz, p. 44; Apollodorus, 1.2.1.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 69; Apollodorus, 1.2.1.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 69; Apollodorus, 1.2.1.

- ^ Gantz, p. 48; Hard 2004, p. 76; Brill’s New Pauly, s.v. Zeus; Homer, Iliad 15.187–193; so too Apollodorus, 1.2.1; cf. Homeric Hymn to Demeter (2), 85–6.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 86; Hesiod, Theogony 183–7.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 86; Gantz, p. 446.

- ^ Gantz, p. 449; Hard 2004, p. 90; Apollodorus, 1.6.1.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 89; Gantz, p. 449; Apollodorus, 1.6.1.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 89; Gantz, p. 449; Salowey, p. 236; Apollodorus, 1.6.2. Compare with Pindar, Pythian 8.12–8, who instead says that Porphyrion is killed by an arrow from Apollo.

- ^ Ogden, pp. 72–3; Gantz, p. 48; Fontenrose, p. 71; Fowler, p. 27; Hesiod, Theogony 820–2. According to Ogden, Gaia «produced him in revenge against Zeus for his destruction of … the Titans». Contrastingly, according to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (3), 305–55, Hera is the mother of Typhon without a father: angry at Zeus for birthing Athena by himself, she strikes the ground with her hand, praying to Gaia, Uranus, and the Titans to give her a child more powerful than Zeus, and receiving her wish, she bears the monster Typhon (Fontenrose, p. 72; Gantz, p. 49; Hard 2004, p. 84); cf. Stesichorus fr. 239 Campbell, pp. 166, 167 [= PMG 239 (Page, p. 125) = Etymologicum Magnum 772.49] (see Gantz, p. 49).

- ^ Gantz, p. 49; Hesiod, Theogony 824–8.

- ^ Fontenrose, p. 71; Hesiod, Theogony 836–8.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 839–68. According to Fowler, p. 27, the monster’s easy defeat at the hands of Zeus is «in keeping with Hesiod’s pervasive glorification of Zeus».

- ^ Ogden, p. 74; Gantz, p. 49; Epimenides FGrHist 457 F8 [= fr. 10 Fowler, p. 97 = fr. 8 Diels, p. 191].

- ^ Fontenrose, p. 73; Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 356–64; Pindar, Olympian 8.16–7; for a discussion of Aeschylus’ and Pindar’s accounts, see Gantz, p. 49.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.6.3.

- ^ Gantz, p. 50; Fontenrose, p. 73.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 84; Fontenrose, p. 73; Gantz, p. 50.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 84; Fontenrose, p. 73.

- ^ Fontenrose, p. 73; Ogden, p. 42; Hard 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 84–5; Fontenrose, p. 73–4.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 85.

- ^ Ogden, p. 74–5; Fontenrose, pp. 74–5; Lane Fox, p. 287; Gantz, p. 50.

- ^ Gantz, p. 59; Hard 2004, p. 82; Homer, Iliad 1.395–410.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 901–905; Gantz, p. 52; Hard 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 901–911; Hansen, p. 68.

- ^ Hansen, p. 68.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 53–62; Gantz, p. 54.

- ^ Homeric Hymn to Apollo (3), 89–123; Hesiod, Theogony 912–920; Morford, p. 211.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 921.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 886–929 (Most, pp. 74, 75); Caldwell, p. 11, table 14.

- ^ a b One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at 358.

- ^ Of Zeus’ children by his seven wives, Athena was the first to be conceived ( 889), but the last to be born. Zeus impregnated Metis then swallowed her, later Zeus himself gave birth to Athena «from his head» ( 924).

- ^ At 217 the Moirai are the daughters of Nyx.

- ^ Hephaestus is produced by Hera alone, with no father at 927–929. In the Iliad and the Odyssey, Hephaestus is apparently the son of Hera and Zeus, see Gantz, p. 74.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.17.4

- ^ Homer, Iliad 4.441

- ^ Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy, 8.424

- ^ Scholia on Theocritus, Idyll 2.12 referring to Sophron

- ^ Iliad, Book 14, line 294

- ^ Scholia on Theocritus’ Idylls 15.64

- ^ Ptolemaeus Chennus, New History Book 6, as epitomized by Patriarch Photius in his Myriobiblon 190.47

- ^ Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelica 3.1.84a-b; Hard 2004, p. 137

- ^ Callimachus, Aetia fragment 48

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Library 2.5.11

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.3.1

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 938

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 3.361–369

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4.14.4

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 507-565

- ^ Hesiod, Works and Days 60–105.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.216–1.348

- ^ Leeming, David (2004). Flood | The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780195156690. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ «The Gods in the Iliad». department.monm.edu. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ^ Homer (1990). The Iliad. South Africa: Penguin Classics.

- ^ Apollodorus, 2.48–77.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 146.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 179.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.43.

- ^ Meisner, pp. 1, 5

- ^ a b c West 1983, pp. 73–74; Meisner, p. 134; Orphic frr. 58 [= Athenagoras, Legatio Pro Christianis 20.2] 153 Kern.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.76.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.13.5.

- ^ Pindar, Isthmian odes 8.25

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.10.4

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 4.71.2

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 285

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 554; Apollodorus, Epitome 1.20

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.747–2.400; Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.42.2; Nonnus, Dionysiaca 38.142–435

- ^ Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods Zeus and the Sun

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 247; Apollodorus, 2.4.8.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 303; Brill’s New Pauly, s.v. Antiope; Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes, 4.1090.

- ^ Gantz, p. 726; Ovid, Metamorphoses 2.401–530; Hyginus, De Astronomica 2.1.2; Apollodorus, 3.8.2; Hansen, p. 119; Grimal, s.v. Callisto, p. 86; Brill’s New Pauly, s.v. Callisto.

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.8.2; Brill’s New Pauly, s.v. Callisto.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 238

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 337; Lane Fox, p. 199.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 522; Ovid, Metamorphoses 10.155–6; Lucian, Dialogues of the Gods 10 (4).

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 137

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 439; Euripides, Helen 16–22.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 438; Cypria fr. 10 West, pp. 88, 89 [= Athenaeus, Deipnosophists 8.334b–d].

- ^ Pseudo-Clement, Recognitions 10.21-23

- ^ Hard 2004, p.244; Hesiod, Theogony 943.

- ^ Hansen, p. 68; Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 912.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 901–911; Hansen, p. 68.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 79; Hesiod, Theogony 921.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 912–920; Morford, p. 211.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 80; Hesiod, Theogony 938.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 77; Hesiod, Theogony 886–900.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 78; Hesiod, Theogony 53–62; Gantz, p. 54.

- ^ Hard 2004, p. 80; Hesiod, Theogony 940.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 901–905; Gantz, p. 52; Hard 2004, p. 78.

- ^ Hyginus, Fabulae 155

- ^ Pindar, Olympian 12.1–2; Gantz, p. 151.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 26, 40; Musaeus fr. 16 Diels, p. 183; Scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 3.467

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.16; Athenaeus, Deipnosophists 9.392e (pp. 320, 321).

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Akragantes; Smith, s.v. Acragas.

- ^ Strabo, Geographica 10.3.19

- ^ Cicero, De Natura Deorum 3.59.

- ^ Scholiast on Pindar, Pythian Odes 3.177; Hesychius

- ^ Homer, Iliad 5.370; Apollodorus, 1.3.1

- ^ West 1983, p. 73; Orphic Hymn to the Graces (60), 1–3 (Athanassakis and Wolkow, p. 49).

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.12.6; Grimal, s.v. Asopus, p. 63; Smith, s.v. Asopus.

- ^ FGrHist 1753 F1b[permanent dead link].

- ^ Smith, s.v. Agdistis.

- ^ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 1.27.1; Grimal, s.v. Manes, p. 271.

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 14.193.