This article is about the Mongol khanate established in the 13th century. For other uses, see Golden Horde (disambiguation).

|

Golden Horde Ulug Ulus |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1242–1502[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Flag during the reign of Öz Beg Khan as shown in Dulcert’s 1339 map (other sources claim that the Golden Horde was named for the yellow banner of the khan[3]). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Sarai (Western wing, later overall) Sighnaq (Eastern wing) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Semi-elective monarchy, later hereditary monarchy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1226–1280 |

Orda Khan (White Horde) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1242–1255 |

Batu Khan (Blue Horde) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1379–1395 |

Tokhtamysh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1459–1465 |

Mahmud bin Küchük (Great Horde) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1481–1502 |

Sheikh Ahmed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Kurultai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Middle Ages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Established after the Mongol invasion of Rus’ |

1242 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Blue Horde and White Horde united |

1379 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Disintegrated into Great Horde |

1466 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Great Stand on the Ugra River |

1480 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

• Sack of Sarai by the Crimean Khanate |

1502[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1310[5][6] | 6,000,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Pul, Som, Dirham[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, lit. ‘Great State’ in Turkic,[8] was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire.[9] With the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire after 1259 it became a functionally separate khanate. It is also known as the Kipchak Khanate or as the Ulus of Jochi, and replaced the earlier less organized Cuman–Kipchak confederation.[10]

After the death of Batu Khan (the founder of the Golden Horde) in 1255, his dynasty flourished for a full century, until 1359, though the intrigues of Nogai instigated a partial civil war in the late 1290s. The Horde’s military power peaked during the reign of Uzbeg Khan (1312–1341), who adopted Islam. The territory of the Golden Horde at its peak extended from Siberia and Central Asia to parts of Eastern Europe from the Urals to the Danube in the west, and from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea in the south, while bordering the Caucasus Mountains and the territories of the Mongol dynasty known as the Ilkhanate.[10]

The khanate experienced violent internal political disorder beginning in 1359, before it briefly reunited (1381–1395) under Tokhtamysh. However, soon after the 1396 invasion of Timur, the founder of the Timurid Empire, the Golden Horde broke into smaller Tatar khanates which declined steadily in power. At the start of the 15th century, the Horde began to fall apart. By 1466, it was being referred to simply as the «Great Horde». Within its territories there emerged numerous predominantly Turkic-speaking khanates. These internal struggles allowed the northern vassal state of Muscovy to rid itself of the «Tatar Yoke» at the Great Stand on the Ugra River in 1480. The Crimean Khanate and the Kazakh Khanate, the last remnants of the Golden Horde, survived until 1783 and 1847 respectively.

Name

The name Golden Horde is a partial calque of Russian Золотая Орда (Zolotája Ordá), itself supposedly a partial calque of Turkic Altan Orda. Золотая (Zolotája) was translated to «Golden,» while Орда (Ordá) was transliterated to «Horde.»

The Turkic word orda means «palace», «camp» or «headquarters», in this case the headquarters of the khan, being the capital of the khanate, metonymically extended to the khanate itself. The English word «horde,» in the sense of a large (and often threatening) group, emerged later, metaphorically extended from the reputation of the Mongol hordes.

The appelation «Golden» is said to have been inspired by the golden color of the tents the Mongols lived in during wartime, or an actual golden tent used by Batu Khan or by Uzbek Khan,[11] or to have been bestowed by the Slavic tributaries to describe the great wealth of the khan.

It was not until the 16th century that Russian chroniclers begin explicitly using the term to refer to this particular successor khanate of the Mongol Empire. The first known use of the term, in 1565, in the Russian chronicle History of Kazan, applied it to the Ulus of Batu (Russian: Улуса Батыя), centered on Sarai.[12][13] In contemporary Persian, Armenian and Muslim writings, and in the records of the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries such as the Yuanshi and the Jami’ al-tawarikh, the khanate was called the «Ulus of Jochi» («realm of Jochi» in Mongolian), «Dasht-i-Qifchaq» (Qipchaq Steppe) or «Khanate of the Qipchaq» and «Comania» (Cumania).[14][15]

The eastern or left wing (or «left hand» in official Mongolian-sponsored Persian sources) was referred to as the Blue Horde in Russian chronicles and as the White Horde in Timurid sources (e.g. Zafar-Nameh). Western scholars have tended to follow the Timurid sources’ nomenclature and call the left wing the White Horde. But Ötemish Hajji (fl. 1550), a historian of Khwarezm, called the left wing the Blue Horde, and since he was familiar with the oral traditions of the khanate empire, it seems likely that the Russian chroniclers were correct, and that the khanate itself called its left wing the Blue Horde.[16] The khanate apparently used the term White Horde to refer to its right wing, which was situated in Batu’s home base in Sarai and controlled the ulus. However, the designations Golden Horde, Blue Horde, and White Horde have not been encountered in the sources of the Mongol period.[17]

Mongol origins (1225–1241)

At his death in 1227, Genghis Khan divided the Mongol Empire amongst his four sons as appanages, but the Empire remained united under the supreme khan. Jochi was the eldest, but he died six months before Genghis. The westernmost lands occupied by the Mongols, which included what is today southern Russia and Kazakhstan, were given to Jochi’s eldest sons, Batu Khan, who eventually became ruler of the Blue Horde, and Orda Khan, who became the leader of the White Horde.[18][19] In 1235, Batu with the great general Subutai began an invasion westwards, first conquering the Bashkirs and then moving on to Volga Bulgaria in 1236. From there he conquered some of the southern steppes of present-day Ukraine in 1237, forcing many of the local Cumans to retreat westward. The Mongol campaign against the Kypchaks and Cumans had already started under Jochi and Subutai in 1216–1218 when the Merkits took shelter among them. By 1239 a large portion of Cumans were driven out of the Crimean peninsula, and it became one of the appanages of the Mongol Empire.[20] The remnants of the Crimean Cumans survived in the Crimean mountains, and they would, in time, mix with other groups in the Crimea (including Greeks, Goths, and Mongols) to form the Crimean Tatar population. Moving north, Batu began the Mongol invasion of Rus’ and spent three years subjugating the principalities of former Kievan Rus’, whilst his cousins Möngke, Kadan, and Güyük moved southwards into Alania.

Using the migration of the Cumans as their casus belli, the Mongols continued west, raiding Poland and Hungary, which culminated in Mongol victories at the battles of Legnica and Mohi. In 1241, however, Ögedei Khan died in the Mongolian homeland. Batu turned back from his siege of Vienna but did not return to Mongolia, rather opting to stay at the Volga River. His brother Orda returned to take part in the succession. The Mongol armies would never again travel so far west. In 1242, after retreating through Hungary, destroying Pest in the process, and subjugating Bulgaria,[21] Batu established his capital at Sarai, commanding the lower stretch of the Volga River, on the site of the Khazar capital of Atil. Shortly before that, the younger brother of Batu and Orda, Shiban, was given his own enormous ulus east of the Ural Mountains along the Ob and Irtysh Rivers.

While the Mongolian language was undoubtedly in general use at the court of Batu, few Mongol texts written in the territory of the Golden Horde have survived, perhaps because of the prevalent general illiteracy. According to Grigor’ev, yarliq, or decrees of the Khans, were written in Mongol, then translated into the Cuman language. The existence of Arabic-Mongol and Persian-Mongol dictionaries dating from the middle of the 14th century and prepared for the use of the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate suggests that there was a practical need for such works in the chancelleries handling correspondence with the Golden Horde. It is thus reasonable to conclude that letters received by the Mamluks – if not also written by them – must have been in Mongol.[21]

Golden Age

Batu Khan (1242–1256)

When the Great Khatun Töregene invited Batu to elect the next Emperor of the Mongol Empire in 1242, he declined to attend the kurultai and instead stayed at the Volga River. Although Batu excused himself by saying he was suffering from old age and illness, it seems that he did not support the election of Güyük Khan. Güyük and Büri, a grandson of Chagatai Khan, had quarreled violently with Batu at a victory banquet during the Mongol occupation of Eastern Europe. He sent his brothers to the kurultai, and the new Khagan of the Mongols was elected in 1246.

All the senior Rus’ princes, including Yaroslav II of Vladimir, Daniel of Galicia, and Sviatoslav III of Vladimir, acknowledged Batu’s supremacy. Originally Batu ordered Daniel to turn the administration of Galicia over to the Mongols, but Daniel personally visited Batu in 1245 and pledged allegiance to him. After returning from his trip, Daniel was visibly influenced by the Mongols, and equipped his army in the Mongol fashion. Austrian visitors to his camp remarked that all of Daniel’s horsemen dressed like Mongols. The only one who did not was Daniel himself, who dressed according to «the Russian custom».[22] Michael of Chernigov, who had killed a Mongol envoy in 1240, refused to show obeisance and was executed in 1246.[23]

When Güyük called Batu to pay him homage several times, Batu sent Yaroslav II, Andrey II of Vladimir and Alexander Nevsky to Karakorum in Mongolia in 1247. Yaroslav II never returned and died in Mongolia. He was probably poisoned by Töregene Khatun, who probably did it to spite Batu and even her own son Güyük, because he did not approve of her regency.[24] Güyük appointed Andrey Grand prince of Vladimir-Suzdal and Alexander prince of Kyiv. However when they returned, Andrey went to Vladimir while Alexander went to Novgorod instead. A bishop by the name of Cyril went to Kiev and found it so devastated that he abandoned the place and went further east instead.[25][26]

In 1248, Güyük demanded Batu come eastward to meet him, a move that some contemporaries regarded as a pretext for Batu’s arrest. In compliance with the order, Batu approached, bringing a large army. When Güyük moved westwards, Tolui’s widow and a sister of Batu’s stepmother Sorghaghtani warned Batu that the Jochids might be his target. Güyük died on the way, in what is now Xinjiang, at about the age of 42. Although some modern historians believe that he died of natural causes because of deteriorating health,[27] he may have succumbed to the combined effects of alcoholism and gout, or he may have been poisoned. William of Rubruck and a Muslim chronicler state that Batu killed the imperial envoy, and one of his brothers murdered the Great Khan Güyük, but these claims are not completely corroborated by other major sources. Güyük’s widow Oghul Qaimish took over as regent, but she would be unable to keep the succession within her branch of the family.

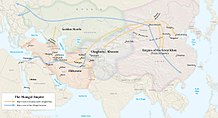

Routes taken by Mongol invaders

With the assistance of Batu, Möngke succeeded as Great Khan in 1251. Utilizing the discovery of a plot designed to remove him, Möngke as the new Great Khan began a purge of his opponents. Estimates of the deaths of aristocrats, officials, and Mongol commanders range from 77 to 300. Batu became the most influential person in the Mongol Empire as his friendship with Möngke ensured the unity of the realm. Batu, Möngke, and other princely lines shared rule over the area from Afghanistan to Turkey. Batu allowed Möngke’s census-takers to operate freely in his realm. In 1252–1259, Möngke conducted a census of the Mongol Empire, including Iran, Afghanistan, Georgia, Armenia, Rus’, Central Asia, and North China. While the census in China was completed in 1252, Novgorod in the far northwest was not counted until winter 1258–59.[28]

With the new powers afforded to Batu by Möngke, he now had direct control over the Rus’ princes. However the Grand Prince Andrey II refused to submit to Batu. Batu sent a punitive expedition under Nevruy, who defeated Andrey and forced him to flee to Novgorod, then Pskov, and finally to Sweden. The Mongols overran Vladimir and harshly punished the principality. The Livonian Knights stopped their advance to Novgorod and Pskov. Thanks to his friendship with Sartaq Khan, Batu’s son, who was a Christian, Alexander was installed as the Grand Prince of Vladimir by Batu in 1252.[29]

Berke (1258–1266)

After Batu died in 1256, his son Sartaq Khan was appointed by Möngke Khan. As soon as he returned from the court of the Great Khan in Mongolia, Sartaq died. The infant Ulaghchi succeeded him under the regency of Boragchin Khatun. The khatun summoned all the Rus’ princes to Sarai to renew their patents. In 1256 Andrey traveled to Sarai to ask for pardon. He was once again reappointed as prince of Vladimir-Suzdal.[30]

Ulaghchi died soon after and Batu Khan’s younger brother Berke, who had been converted to Islam, was enthroned as khan of the Golden Horde in 1258.[31]

In 1256, Daniel of Galicia openly defied the Mongols and ousted their troops in northern Podolia. In 1257, he repelled Mongol assaults led by the prince Kuremsa on Ponyzia and Volhynia and dispatched an expedition with the aim of taking Kiev. Despite initial successes, in 1259 a Mongol force under Boroldai entered Galicia and Volhynia and offered an ultimatum: Daniel was to destroy his fortifications or Boroldai would assault the towns. Daniel complied and pulled down the city walls. In 1259 Berke launched savage attacks on Lithuania and Poland, and demanded the submission of Béla IV, the Hungarian monarch, and the French King Louis IX in 1259 and 1260.[32] His assault on Prussia in 1259/60 inflicted heavy losses on the Teutonic Order.[33] The Lithuanians were probably tributary in the 1260s, when reports reached the Curia that they were in league with the Mongols.[34]

Mongol agents began taken censuses in the Rus’ principalities. Novgorod in the far northwest was not counted until winter 1258–59. There was an uprising in Novgorod against the Mongol census, but Alexander Nevsky forced the city to submit to the census and taxation.[28]

In 1261, Berke approved the establishment of a church in Sarai.[35]

Toluid Civil War (1260–1264)

After Möngke Khan died in 1259, the Toluid Civil War broke out between Kublai Khan and Ariq Böke. While Hulagu Khan of the Ilkhanate supported Kublai, Berke sided with Ariq Böke.[36] There is evidence that Berke minted coins in Ariq Böke’s name,[37] but he remained militarily neutral. After the defeat of Ariq Böke in 1264, he freely acceded to Kublai’s enthronement.[38] However, some elites of the White Horde joined Ariq Böke’s resistance.

Berke–Hulagu war (1262–1266)

The Golden Horde army defeats the Ilkhanate at the battle of Terek in 1262. Many of Hulagu’s men drowned in the Terek River while withdrawing.

Möngke ordered the Jochid and Chagatayid families to join Hulagu’s expedition to Iran. Berke’s persuasion might have forced his brother Batu to postpone Hulagu’s operation, little suspecting that it would result in eliminating the Jochid predominance there for several years. During the reign of Batu or his first two successors, the Golden Horde dispatched a large Jochid delegation to participate in Hulagu’s expedition in the Middle East in 1256/57.

One of the Jochid princes who joined Hulagu’s army was accused of witchcraft and sorcery against Hulagu. After receiving permission from Berke, Hulagu executed him. After that two more Jochid princes died suspiciously. According to some Muslim sources, Hulagu refused to share his war booty with Berke in accordance with Genghis Khan’s wish. Berke was a devoted Muslim who had had a close relationship with the Abbasid Caliph Al-Musta’sim, who had been killed by Hulagu in 1258. The Jochids believed that Hulagu’s state eliminated their presence in the Transcaucasus.[39] Those events increased the anger of Berke and the war between the Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate soon broke out in 1262.

The increasing tension between Berke and Hulagu was a warning to the Golden Horde contingents in Hulagu’s army to flee. One contingent reached the Kipchak Steppe, another traversed Khorasan, and a third body took refuge in Mamluk ruled Syria where they were well received by Sultan Baybars (1260–1277). Hulagu harshly punished the rest of the Golden Horde army in Iran. Berke sought a joint attack with Baybars and forged an alliance with the Mamluks against Hulagu. The Golden Horde dispatched the young prince Nogai to invade the Ilkhanate but Hulagu forced him back in 1262. The Ilkhanid army then crossed the Terek River, capturing an empty Jochid encampment, only to be routed in a surprise attack by Nogai’s forces. Many of them were drowned as the ice broke on the frozen Terek River. The outbreak of conflict was made more annoying to Berke by the rebellion of Suzdal at the same time, killing Mongol darughachis and tax-collectors. Berke planned a severe punitive expedition. But after Alexander Nevsky begged Berke not to punish the Rus’ and the Vladimir-Suzdal cities agreed to pay a large indemnity, Berke relented. Alexander died on his trip back in Gorodets on the Volga. He was well loved by the people and called the «sun of Russia».[40][41]

When the former Seljuk Sultan Kaykaus II was arrested in the Byzantine Empire, his younger brother Kayqubad II appealed to Berke. An Egyptian envoy was also detained there. With the assistance of the Kingdom of Bulgaria (Berke’s vassal), Nogai invaded the Empire in 1265. By the next year, the Mongol-Bulgarian army was within reach of Constantinople. Nogai forced Michael VIII Palaiologos to release Kaykaus and pay tribute to the Horde. Berke gave Kaykaus Crimea as an appanage and had him marry a Mongol woman. Hulagu died in February 1265 and Berke followed the next year while on campaign in Tiflis, causing his troops to retreat.[42]

Ariq Böke had earlier placed Chagatai’s grandson Alghu as Chagatayid Khan, ruling Central Asia. He took control of Samarkand and Bukhara. When the Muslim elites and the Jochid retainers in Bukhara declared their loyalty to Berke, Alghu smashed the Golden Horde appanages in Khorazm. Alghu insisted Hulagu attack the Golden Horde; he accused Berke of purging his family in 1252. In Bukhara, he and Hulagu slaughtered all the retainers of the Golden Horde and reduced their families into slavery, sparing only the Great Khan Kublai’s men.[43] After Berke gave his allegiance to Kublai, Alghu declared war on Berke, seizing Otrar and Khorazm. While the left bank of Khorazm would eventually be retaken, Berke had lost control over Transoxiana. In 1264 Berke marched past Tiflis to fight against Hulagu’s successor Abaqa, but he died en route.

Mengu-Timur (1266–1280)

Berke left no sons, so Batu’s grandson Mengu-Timur was nominated by Kublai and succeeded his uncle Berke.[44] However, Mengu-Timur secretly supported the Ögedeid prince Kaidu against Kublai and the Ilkhanate. After the defeat of Ghiyas-ud-din Baraq, a peace treaty was concluded in 1267 granting one-third of Transoxiana to Kaidu and Mengu-Timur.[45] In 1268, when a group of princes operating in Central Asia on Kublai’s behalf mutinied and arrested two sons of the Qaghan (Great Khan), they sent them to Mengu-Timur. One of them, Nomoghan, favorite of Kublai, was located in the Crimea.[46] Mengu-Timur might have briefly struggled with Hulagu’s successor Abagha, but the Great Khan Kublai forced them to sign a peace treaty.[47] He was allowed to take his share in Persia. Independently from the Khan, Nogai expressed his desire to ally with Baibars in 1271. Despite the fact that he was proposing a joint attack on the Ilkhanate with the Mamluks of Egypt, Mengu-Timur congratulated Abagha when Baraq was defeated by the Ilkhan in 1270.[48]

In 1267, Mengu-Timur issued a diploma – jarliq – to exempt Rus’ clergy from any taxation and gave to the Genoese and Venice exclusive trading rights in Caffa and Azov. Some of Mengu-Timur’s relatives converted to Christianity at the same time and settled among the Rus’ people. One of them was a prince who settled in Rostov and became known as Tsarevich Peter of the Horde (Peter Ordynsky). Even though Nogai invaded the Eastern Orthodox Christian Byzantine Empire in 1271, the Khan sent his envoys to maintain friendly relationship with Michael VIII Palaiologos, who sued for peace and married one of his daughters, Euphrosyne Palaiologina, to Nogai. Mengu-Timur ordered the Grand prince of Rus to allow German merchants free travel through his lands. This gramota says:

Mengu-Timur’s word to Prince Yaroslav: give the German merchants way into your lands. From Prince Yaroslav to the people of Riga, to the great and the young, and to all: your way is clear through my lands; and who comes to fight, with them I do as I know; but for the merchant the way is clear.[49]

This decree also allowed Novgorod’s merchants to travel throughout the Suzdal lands without restraint.[50] Mengu Timur honored his vow: when the Danes and the Livonian Knights attacked Novgorod Republic in 1269, the Khan’s great basqaq (darughachi), Amraghan, and many Mongols assisted the Rus’ army assembled by the Grand duke Yaroslav. The Germans and the Danes were so cowed that they sent gifts to the Mongols and abandoned the region of Narva.[51] The Mongol Khan’s authority extended to all Rus’ principalities, and in 1274–75 the census took place in all Rus’ cities, including Smolensk and Vitebsk.[52]

In 1277, Mengu-Timur launched a campaign against the Alans north of the Caucasus. Along with the Mongol army were also Rus’, who took the fortified stronghold of the Alans, Dadakov, in 1278.[53]

Dual khanship (1281–1299)

Mengu-Timur was succeeded in 1281 by his brother Töde Möngke, who was a Muslim. However Nogai Khan was now strong enough to establish himself as an independent ruler. The Golden Horde was thus ruled by two khans.[54]

Töde Möngke made peace with Kublai, returned his sons to him, and acknowledged his supremacy.[55][56] Nogai and Köchü, Khan of the White Horde and son of Orda Khan, also made peace with the Yuan dynasty and the Ilkhanate. According to Mamluk historians, Töde Möngke sent the Mamluks a letter proposing to fight against their common enemy, the unbelieving Ilkhanate. This indicates that he might have had an interest in Azerbaijan and Georgia, which were both ruled by the Ilkhans.

In the 1270s Nogai had savagely raided Bulgaria[57] and Lithuania.[58] He blockaded Michael Asen II inside Drăstăr in 1279, executed the rebel emperor Ivailo in 1280, and forced George Terter I to seek refuge in the Byzantine Empire in 1292. In 1284 Saqchi came under the Mongol rule during the major invasion of Bulgaria, and coins were struck in the Khan’s name.[59] Smilets was installed by Nogai as emperor of Bulgaria. Accordingly, the reign of Smilets has been considered the height of Mongol overlordship in Bulgaria. When he was expelled by a local boyars c. 1295, the Mongols launched another invasion to protect their protege. Nogai compelled Serbian king Stefan Milutin to accept Mongol supremacy and received his son, Stefan Dečanski, as hostage in 1287. Under his rule, the Vlachs, Slavs, Alans, and Turco-Mongols lived in modern-day Moldavia.

At the same time, the influence of Nogai greatly increased in the Golden Horde. Backed by him, some Rus’ princes, such as Dmitry of Pereslavl, refused to visit the court of the Töde Möngke in Sarai, while Dmitry’s brother Andrey of Gorodets sought assistance from Töde Möngke. Nogai vowed to support Dmitry in his struggle for the grand ducal throne. On hearing about this, Andrey renounced his claims to Vladimir and Novgorod and returned to Gorodets. He returned with Mongol troops sent by Töde Möngke and seized Vladimir from Dmitry. Dmitry retaliated with the support of Mongol troops from Nogai and retook his holdings. In 1285 Andrey again led a Mongol army under a Borjigin prince to Vladimir, but Dmitry expelled them.[60]

In 1283, Mengu-Timur converted to Islam and abandoned state affairs. Rumors spread that the khan was mentally ill and only cared for clerics and sheikhs. In 1285, Talabuga and Nogai invaded Hungary. While Nogai was successful in subduing Slovakia, Talabuga was stalled north of the Carpathian Mountains. Talabuga’s soldiers were angered and sacked Galicia and Volynia instead. In 1286, Talabuga and Nogai attacked Poland and ravaged the country. After returning, Talabuga overthrew Töde Möngke, who was left to live in peace. Talabuga’s army made unsuccessful attempts to invade the Ilkhanate in 1288 and 1290.[61]

During a punitive expedition against the Circassians, Talabuga became resentful of Nogai, whom he believed did not provide him with adequate support during the invasions of Hungary and Poland. Talabuga challenged Nogai, but was defeated in a coup and replaced with Toqta in 1291.[62]

Some of the Rus’ princes complained to Toqta about Dmitry. Mikhail Yaroslavich was summoned to appear before Nogai in Sarai, and Daniel of Moscow declined to come. In 1293 Toqta sent a punitive expedition led by his brother, Dyuden to Rus’ and Belarus to punish those stubborn subjects. The latter sacked fourteen major cities, finally forcing Dmitry to abdicate. Nogai was annoyed by this independent action and sent his wife to Toqta in 1293 to remind him who was in charge. In the same year, Nogai sent an army to Serbia and forced the king to acknowledge himself as a vassal.[63]

Nogai’s daughter married a son of Kublai’s niece, Kelmish, who was wife of a Qongirat general of the Golden Horde. Nogai was angry with Kelmish’s family because her Buddhist son despised his Muslim daughter. For this reason, he demanded Toqta send Kelmish’s husband to him. Nogai’s independent actions related to Rus’ princes and foreign merchants had already annoyed Toqta. Toqta thus refused and declared war on Nogai. Toqta was defeated in their first battle. Nogai’s army turned their attention to Caffa and Soldaia, looting both cities.. Within two years, Toqta returned and killed Nogai in 1299 at the Kagamlik, near the Dnieper. Toqta had his son stationed troops in Saqchi and along the Danube as far as the Iron Gate.[64] Nogai’s son Chaka of Bulgaria, first escaped to the Alans, and then Bulgaria where he briefly ruled as emperor before he was murdered by Theodore Svetoslav on the orders of Toqta.[65]

After Mengu-Timur died, rulers of the Golden Horde withdrew their support from Kaidu, the head of the House of Ögedei. Kaidu tried to restore his influence in the Golden Horde by sponsoring his own candidate Kobeleg against Bayan (r. 1299–1304), Khan of the White Horde.[66] After taking military support from Toqta, Bayan asked help from the Yuan dynasty and the Ilkhanate to organize a unified attack on the Chagatai Khanate under the leadership of Kaidu and his second-in-command Duwa. However, the Yuan court was unable to send quick military support.[67]

General peace (1299–1312)

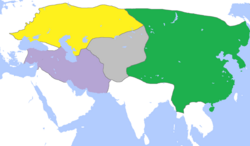

The division of the Mongol Empire, c. 1300, with the Golden Horde in yellow

From 1300 to 1303 a severe drought occurred in the areas surrounding the Black Sea. However the troubles were soon overcome and conditions in the Golden Horde rapidly improved under Toqta’s reign. After the defeat of Nogai Khan, his followers either fled to Podolia or remained under the service of Toqta, to become what would eventually be known as the Nogai Horde.

[69]

Toqta established the Byzantine-Mongol alliance by Maria, an illegitimate daughter of Andronikos II Palaiologos.[70] A report reached Western Europe that Toqta was highly favourable to the Christians.[71] According to Muslim observers, however, Toqta remained an idol-worshiper (Buddhism and Tengerism) and showed favour to religious men of all faiths, though he preferred Muslims.[72]

He demanded that the Ilkhan Ghazan and his successor Oljeitu give Azerbaijan back but was refused. Then he sought assistance from Egypt against the Ilkhanate. Toqta made his man ruler in Ghazna, but he was expelled by its people. Toqta dispatched a peace mission to the Ilkhan Gaykhatu in 1294, and peace was maintained mostly uninterrupted until 1318.[73]

In 1304 ambassadors from the Mongol rulers of Central Asia and the Yuan announced to Toqta their general peace proposal. Toqta immediately accepted the supremacy of Yuan emperor Temür Öljeytü, and all yams (postal relays) and commercial networks across the Mongol khanates reopened. Toqta introduced the general peace among the Mongol khanates to Rus’ princes at the assembly in Pereyaslavl.[74] The Yuan influence seemed to have increased in the Golden Horde as some of Toqta’s coins carried ‘Phags-pa script in addition to Mongolian script and Persian characters.[75]

Toqta arrested the Italian residents of Sarai and besieged Caffa in 1307. The cause was apparently Toqta’s displeasure at the Genoese slave trade of his subjects, who were mostly sold as soldiers to Egypt.[76] In 1308, Caffa was plundered by the Mongols.[77]

During the late reign of Toqta, tensions between princes of Tver and Moscow became violent. Daniel of Moscow seized the town of Kolomna from the Principality of Ryazan, which turned to Toqta for protection. However Daniel was able to beat both Ryazan and Mongol troops in 1301. His successor Yury of Moscow also seized Pereslavl-Zalessky. Toqta considered eliminating the special status of the Grand principality of Vladimir, and placing all the Rus’ princes on the same level. Toqta decided to personally visit northern Rus’ to settle the conflict between the princes, but he fell ill and died while crossing the Volga in 1313.[78]

Islamization

Öz Beg Khan (1313–1341)

Territories of the Golden Horde under Öz Beg Khan.

After Öz Beg Khan assumed the throne in 1313, he adopted Islam as the state religion. He built a large mosque in the city of Solkhat in the Crimea in 1314 and proscribed Buddhism and Shamanism among the Mongols in the Golden Horde. By 1315, Öz Beg had successfully Islamicized the Horde and killed Jochid princes and Buddhist lamas who opposed his religious policy.[79] Under the reign of Öz Beg, trade caravans went unmolested and there was general order in the Golden Horde. When Ibn Battuta visited Sarai in 1333, he found it to be a large and beautiful city with vast streets and fine markets where Mongols, Alans, Kypchaks, Circassians, Rus’, and Greeks each had their own quarters. Merchants had a special walled section of the city all to themselves.[80]

Öz Beg continued the alliance with the Mamluks begun by Berke and his predecessors. He kept a friendly relationship with the Mamluk Sultan and his shadow Caliph in Cairo. In 1320, the Jochid princess Tulunbay was married to Al-Nasir Muhammad, Sultan of Egypt.[81] Al-Nasir Muhammad came to believe that Tulunbay was not a real Chingissid princess but an impostor. In 1327/1328, he divorced her, and she then married one of al-Nasir Muhammad’s commanders. When Öz Beg learned of the divorce in 1334/1335, he sent an angry missive. Al-Nasir Muhammad claimed that she had died and showed his ambassadors a fake legal document as proof, although Tulunbay still lived and would only pass away in 1340.[82]

The Golden Horde invaded the Ilkhanate under Abu Sa’id in 1318, 1324, and 1335. Öz Beg’s ally Al-Nasir refused to attack Abu Sa’id because the Ilkhan and the Mamluk Sultan signed a peace treaty in 1323. In 1326 Öz Beg reopened friendly relations with the Yuan dynasty and began to send tributes thereafter.[83] From 1339 he received annually 24,000 ding in Yuan paper currency from the Jochid appanages in China.[84] When the Ilkhanate collapsed after Abu Sa’id’s death, its senior-beys approached Öz Beg in their desperation to find a leader, but the latter declined after consulting with his senior emir, Qutluq Timür.

Öz Beg, whose total army exceeded 300,000, repeatedly raided Thrace in aid of Bulgaria’s war against Byzantium and Serbia beginning in 1319. The Byzantine Empire under Andronikos II Palaiologos and Andronikos III Palaiologos was raided by the Golden Horde between 1320 and 1341, until the Byzantine port of Vicina Macaria was occupied. Friendly relations were established with the Byzantine Empire for a brief period after Öz Beg married Andronikos III Palaiologos’s illegitimate daughter, who came to be known as Bayalun. In 1333, she was given permission to visit her father in Constantinople and never returned, apparently fearing her forced conversion to Islam.[85][86] Öz Beg’s armies pillaged Thrace for forty days in 1324 and for 15 days in 1337, taking 300,000 captives. In 1330, Öz Beg sent 15,000 troops to Serbia in 1330 but was defeated.[87] Backed by Öz Beg, Basarab I of Wallachia declared an independent state from the Hungarian crown in 1330.[68]

With Öz Beg’s assistance, the Grand duke Mikhail Yaroslavich won the battle against the party in Novgorod in 1316. While Mikhail was asserting his authority, his rival Yury of Moscow ingratiated himself with Öz Beg so that he appointed him chief of the Rus’ princes and gave him his sister, Konchak, in marriage. After spending three years at Öz Beg’s court, Yury returned with an army of Mongols and Mordvins. After he ravaged the villages of Tver, Yury was defeated by Mikhail in December 1318, and his new wife and the Mongol general, Kawgady, were captured. While she stayed in Tver, Konchak, who converted to Christianity and adopted the name Agatha, died. Mikhail’s rivals suggested to Öz Beg that he had poisoned the Khan’s sister and revolted against his rule. Mikhail was summoned to Sarai and executed on November 22, 1318.[88][89] Yury became grand duke once more. Yury’s brother Ivan accompanied the Mongol general Akhmyl in suppressing a revolt by Rostov in 1320. In 1322, Mikhail’s son, Dmitry, seeking revenge for his father’s murder, went to Sarai and persuaded the Khan that Yury had appropriated a large portion of the tribute due to the Horde. Yury was summoned to the Horde for a trial, but he was killed by Dmitry before any formal investigation. Eight months later, Dmitry was also executed by the Horde for his crime. The title of grand duke went to Aleksandr Mikhailovich.[90]

In 1327, the baskak Shevkal, cousin of Öz Beg, arrived in Tver from the Horde, with a large retinue. They took up residence at Aleksander’s palace. Rumors spread that Shevkal wanted to occupy the throne for himself and introduce Islam to the city. When, on 15 August 1327, the Mongols tried to take a horse from a deacon named Dyudko, he cried for help and a mob killed the Mongols. Shevkal and his remaining guards were burnt alive. The incident in Tver caused Öz Beg to begin backing Moscow as the leading Rus’ state. Ivan I Kalita was granted the title of grand prince and given the right to collect taxes from other Rus’ potentates. Öz Beg also sent Ivan at the head of an army of 50,000 soldiers to punish Tver. Aleksander was shown mercy in 1335, however, when Moscow requested that he and his son Feoder be quartered in Sarai by orders of the Khan on October 29, 1339.[91]

In 1323 Grand Duke Gediminas of Lithuania gained control of Kiev and installed his brother Fedor as prince, but the principality’s tribute to the Khan continued. On a campaign a few years later, the Lithuanians under Fedor included the Khan’s baskak in their entourage.[92]

A decree, issued probably by Mengu-Timur, allowing the Franciscans to proselytize, was renewed by Öz Beg in 1314. Öz Beg allowed the Christian Genoese to settle in Crimea after his accession, but the Mongols sacked their outpost Sudak in 1322 when the Genoese clashed with the Turks.[93] The Genoese merchants in the other towns were not molested. Pope John XXII requested Öz Beg to restore Roman Catholic churches destroyed in the region. Öz Beg signed a new trade treaty with the Genoese in 1339 and allowed them to rebuild the walls of Caffa. In 1332 he allowed the Venetians to establish a colony at Tanais on the Don. In 1333, when Ibn Battuta visited Sudak, he found the population to be predominantly Turkish.[81]

Jani Beg (1342–1357)

Öz Beg’s eldest son Tini Beg reigned briefly from 1341 to 1342 before his younger brother, Jani Beg (1342–1357), came to power.[94]

In 1344, Jani Beg tried to seize Caffa from the Genoese but failed. In 1347, he signed a commercial treaty with Venice. The slave trade flourished due to strengthening ties with the Mamluk Sultanate. Growth of wealth and increasing demand for products typically produce population growth, and so it was with Sarai. Housing in the region increased, which transformed the capital into the center of a large Muslim Sultanate.[94]

The Black Death of the 1340s was a major factor contributing to the economic downfall of the Golden Horde. It struck the Crimea in 1345 and killed over 85,000 people.[95]

Jani Beg abandoned his father’s Balkan ambitions and backed Moscow against Lithuania and Poland. Jani Beg sponsored joint Mongol-Rus’ military expeditions against Lithuania and Poland. In 1344 his army marched against Poland with auxiliaries from Galicia–Volhynia, as Volhynia was part of Lithuania. In 1349, however, Galicia–Volhynia was occupied by a Polish-Hungarian force, and the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia was finally conquered and incorporated into Poland. This act put an end to the relationship of vassalage between the Galicia–Volhynia Rus’ and the Golden Horde.[96] In 1352, a Mongol-Russian army ravaged Polish territory and Lublin. The Polish King, Casimir III the Great, submitted to the Horde in 1357 and paid tribute in order to avoid more conflicts. The seven Mongol princes were sent by Jani Beg to assist Poland.[97]

Jani Beg asserted Jochid dominance over the Chagatai Khanate and conquered Tabriz, ending Chobanid rule there in 1356. After accepting the surrender of the Jalayirids, Jani Beg boasted that three uluses of the Mongol Empire were under his control. However on his way back from Tabriz, Jani Beg was murdered on the order of his own son, Berdi Beg. Following the assassination of Jani Beg, the Golden Horde quickly lost Azerbaijan to the Jalayir king Shaikh Uvais in 1357.[98]

Decline

Great troubles (1359–1381)

Berdi Beg was killed in a coup by his brother Qulpa in 1359. Qulpa’s two sons were Christians and bore the Slavic names Michael and Ivan, which outraged the Muslim populace of the Golden Horde. In 1360, Qulpa’s brother Nawruz Beg revolted against the khan and killed him and his sons. In 1361, a descendant of Shiban (5th son of Jochi), was invited by some grandees to seize the throne. Khidr rebelled against Nawruz, whose own lieutenant betrayed him and handed him over to be executed. Khidr was slain by his own son, Timur Khwaja, in the same year. Timur Khwaja reigned for only five weeks before descendants of Öz Beg Khan seized power.[99]

In 1362, the Golden Horde was divided between Keldi Beg in Sarai, Bulat Temir in Volga Bulgaria, and Abdullah in Crimea. Meanwhile, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania attacked the western tributaries of the Golden Horde and conquered Kyiv and Podolia after the Battle of Blue Waters in 1363.[40] A powerful Mongol general by the name of Mamai backed Abdullah but failed to take Sarai, which saw the reign of two more khans, Murad and Aziz. Abdullah died in 1370 and Muhammad Bolaq was enthroned as puppet khan by Mamai.[99] Mamai also had to deal with a rebellion in Nizhny Novgorod. Muscovite troops impinged on the Bulgar territory of Arab-Shah, the son of Bulat Temir, who caught them off guard and defeated them on the banks of the Pyana River. However Arab-Shah was unable to take advantage of the situation because of the advance of another Mongol general from the east.[100] Encouraged by the news of Muscovite defeat, Mamai sent an army against Dmitri Donskoy, who defeated the Mongol forces at the Battle of the Vozha River in 1378. Mamai hired Genoese, Circassian, and Alan mercenaries for another attack on Moscow in 1380. In the ensuing battle, Mongol forces once again lost at the Battle of Kulikovo.[100]

By 1360, Urus Khan had set up court in Sighnaq. He was named Urus, which means Russian in Turkish language, presumably because «Urus-Khan’s mother was a Russian princess… he was prepared to press his claims on Russia on that ground.»[101] In 1372, Urus marched west and occupied Sarai. His nephew and lieutenant Tokhtamysh deserted him and went to Timur for assistance. Tokhtamysh attacked Urus, killing his son Kutlug-Buka, but lost the battle and fled to Samarkand. Soon after, another general Edigu deserted Urus and went over to Timur. Timur personally attacked Urus in 1376 but the campaign ended indecisively. Urus died the next year and was succeeded by his son, Timur-Melik, who immediately lost Sighnaq to Tokhtamysh. In 1378, Tokhtamysh conquered Sarai.[102]

By the 1380s, the Shaybanids and Qashan attempted to break free of the Khan’s power.

Tokhtamysh (1381–1395)

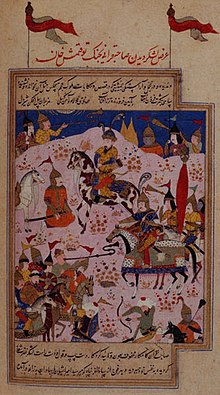

Emir Timur and his forces advance against the Golden Horde, Khan Tokhtamysh.

Tokhtamysh attacked Mamai, who had recently suffered a loss against Muscovy, and defeated him in 1381, thus briefly reestablishing the Golden Horde as a dominant regional power. Mamai fled to the Genoese who killed him soon after. Tokhtamysh sent an envoy to the Rus’ states to resume their tributary status, but the envoy only made it as far as Nizhny Novgorod before he was stopped. Tokhtamysh immediately seized all the boats on the Volga to ferry his army across and commenced the Siege of Moscow (1382), which fell after three days under a false truce. The next year most of the Rus’ princes once again made obeisance to the khan and received patents from him.[103] Tokhtamysh also crushed the Lithuanian army at Poltava in the next year.[104] Władysław II Jagiełło, Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland, accepted his supremacy and agreed to pay tribute in return for a grant of Rus’ territory.[105]

Elated by his success, Tokhtamysh invaded Azerbaijan in 1386 and seized Tabriz. He ordered money with his name on it coined in Khwarezm and sent envoys to Egypt to seek an alliance. In 1387, Timur sent an army into Azerbaijan and fought indecisively with the forces of the Golden Horde. Tokhtamysh invaded Transoxania and reached as far as Bukhara, but failed to take the city, and had to turn back. Timur retaliated by invading Khwarezm and destroyed Urgench. Tokhtamysh attacked Timur on the Syr Darya in 1389 with a massive army including Russians, Bulgars, Circassians, and Alans. The battle ended indecisively. In 1391, Timur gathered an army 200,000 strong and defeated Tokhtamysh at the Battle of the Kondurcha River. Timur’s allies Temür Qutlugh and Edigu took the eastern half of the Golden Horde. Tokhtamysh returned in 1394, ravaging the region of Shirvan. In 1395, Timur annihilated Tokhtamysh’s army again at the Battle of the Terek River, destroyed his capital, looted the Crimean trade centers, and deported the most skillful craftsmen to his own capital in Samarkand. Timur’s forces reached as far north as Ryazan before turning back.[106]

Edigu (1395–1419)

Temür Qutlugh was chosen Khan in Sarai while Edigu became co-ruler, and Koirijak was appointed sovereign of the White Horde by Timur.[107] Tokhtamysh fled to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and asked Vytautas for assistance in retaking the Golden Horde in exchange for suzerainty over the Rus’ lands. In 1399, Vytautas and Tokhtamysh attacked Temür Qutlugh and Edigu at the Battle of the Vorskla River but were defeated. The Golden Horde victory secured Kyiv, Podolia, and some land in the lower Bug River basin. Tokhtamysh died in obscurity in Tyumen around 1405. His son Jalal al-Din fled to Lithuania and participated in the Battle of Grunwald against the Teutonic Order.[108]

Temür Qutlugh died in 1400 and his cousin Shadi Beg was elected khan with Edigu’s approval. After defeating Vytautas, Edigu concentrated on strengthening the Golden Horde. He forbade selling Golden Horde subjects as slaves abroad. Later on the slave trade was resumed, but only Circassians were allowed to be sold. As a result most of the Mamluk recruits in the 15th century were of Circassian origin. Timur died in 1405 and Edigu took advantage to seize Khwarezm a year later. From 1400 to 1408, Edigu gradually regained the eastern Rus’ tributaries, with the exception of Moscow, which he failed to take in a siege but ravaged the surrounding area. Smolensk was also lost to Lithuania. Shadi Beg rebelled against Edigu but was defeated and fled to Astrakhan. Shadi Beg was replaced by Pulad, who died in 1410 and was succeeded by Temur Khan, the son of Temür Qutlugh. Temur Khan turned against Edigu and forced him to flee to Khwarezm in 1411. Temur himself was ousted the next year by Jalal al-Din, who returned from Lithuania and briefly took the throne. In 1414, Shah Rukh of the Timurids conquered Khwarezm. Edigu fled to the Crimea where he launched raids on Kiev and tried to forge an alliance with Lithuania to win back the horde. Edigu died in 1419 in a skirmish with one of Tokhtamysh’s sons.[109]

Disintegration and succession

Khanate of Sibir (1405)

The Khanate of Sibir was ruled by a dynasty originating with Taibuga in 1405 at Chimgi-Tura. After his death in 1428, the khanate was ruled by the Uzbek[clarification needed] khan Abu’l-Khayr Khan. When he died in 1468, the khanate split in two, with the Shaybanid Ibak Khan situated in Chimgi-Tura, and the Taibugid Muhammad at the fortress of Sibir, from which the khanate derives its name.[110]

Uzbek Khanate (1428)

After 1419, the Golden Horde functionally ceased to exist. Ulugh Muhammad was officially Khan of the Golden Horde but his authority was limited to the lower banks of the Volga where Tokhtamysh’s other son Kepek also reigned. The Golden Horde’s influence was replaced in Eastern Europe by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, who Ulugh Muhammad turned to for support. The political situation in the Golden Horde did not stabilize. In 1422, the grandson of Urus Khan, Barak Khan, attacked the reigning khans in the west. Within two years, Ulugh, Kepek, and another claimant Dawlat Berdi, were defeated. Ulugh Muhammad fled to Lithuania, Kepek tried to raid Odoyev and Ryazan but failed to establish himself in those regions, and Dawlat took advantage of the situation to seize Crimea. Barak defeated an invasion by Ulugh Beg in 1427 but was assassinated the next year. His successor, Abu’l-Khayr Khan, founded the Uzbek Khanate.[111]

Nogai Horde (1440s)

By the 1440s, a descendant of Edigu by the name of Musa bin Waqqas was ruling at Saray-Jük as an independent khan of the Nogai Horde.[112]

Khanate of Kazan (1445)

Ulugh Muhammad ousted Dawlat Berdi from Crimea. At the same time, the khan Hacı I Giray fled to Lithuania to ask Vytautas for support. In 1426, Ulugh Muhammad contributed troops to Vytautas’ war against Pskov. Despite the Golden Horde’s greatly reduced status, both Yury of Zvenigorod and Vasily Kosoy still visited Ulugh Muhammad’s court in 1432 to request a grand ducal patent. A year later, Ulugh Muhammad lost the throne to Sayid Ahmad I, a son of Tokhtamysh. Ulugh Muhammad fled to the town of Belev on the upper Oka River, where he came into conflict with the Grand Duchy of Muscovy. Vasily II of Moscow attempted to drive him out but was defeated at the Battle of Belyov. Ulugh Muhammad became master of Belev. Ulugh Muhammad continued to exert influence on Muscovy, occupying Gorodets in 1444. Vasily II even wanted him to issue him a patent for the throne, but Ulugh Muhammad attacked him instead at Murom in 1445. On 7 July, Vasily II was defeated and taken prisoner by Ulugh Muhammad at the Battle of Suzdal. Despite his victory, Ulugh Muhammad’s situation was pressed. The Golden Horde was no more, he had barely 10,000 soldiers, and thus could not press the advantage against Moscow. A few months later he released Vasily II for a ransom of 25,000 rubles. Unfortunately, Ulugh Muhammad was murdered by his son, Mäxmüd of Kazan, who fled to the middle Volga region and founded the Khanate of Kazan in 1445.[113] In 1447, Mäxmüd sent an army against Muscovy but was repelled. [114]

Crimean Khanate (1449)

In 1449, Hacı I Giray seized Crimea from Ahmad I, and founded the Crimean Khanate.[114] The Crimean Khanate considered its state as the heir and legal successor of the Golden Horde and Desht-i Kipchak, called themselves khans of «the Great Horde, the Great State and the Throne of the Crimea».[115][116]

Qasim Khanate (1452)

One of Ulugh Muhammad’s sons, Qasim Khan, fled to Moscow, where Vasily II granted him land that became the Qasim Khanate.[114]

Kazakh Khanate (1458)

In 1458, Janibek Khan and Kerei Khan led 200,000 of Abu’l-Khayr Khan’s followers eastwards to the Chu River where Esen Buqa II of Moghulistan granted them pasture lands. After Abu’l-Khayr Khan died in 1467, they assumed leadership over most of his followers, and became the Kazakh Khanate.[117]

Great Horde (1459–1502)

In 1435, the khan Küchük Muhammad ousted Sayid Ahmad. He attacked Ryazan and suffered a major defeat against the forces of Vasily II. Sayid Ahmad continued to raid Muscovy and in 1449 made a direct attack on Moscow. However he was defeated by Muscovy’s ally Qasim Khan. In 1450, Küchük Muhammad attacked Ryazan but was turned back by a combined Russo-Tatar army. In 1451, Sayid Ahmad tried to take Moscow again and failed.[118]

Küchük Muhammad was succeeded by his son Mahmud bin Küchük in 1459, from which point on the Golden Horde came to be known as the Great Horde. Mahmud was succeeded by his brother Ahmed Khan bin Küchük in 1465. In 1469, Ahmed attacked and killed the Uzbek Abu’l-Khayr Khan. In the summer of 1470, Ahmed organized an attack against Moldavia, the Kingdom of Poland, and Lithuania. By August 20, the Moldavian forces under Stephen the Great defeated the Tatars at the battle of Lipnic. In 1474 and 1476, Ahmed insisted that Ivan III of Russia recognize the khan as his overlord. In 1480, Ahmed organized a military campaign against Moscow, resulting in a face off between two opposing armies known as the Great Stand on the Ugra River. Ahmed judged the conditions unfavorable and retreated. This incident formally ended the «Tatar Yoke» over Rus’ lands. On 6 January 1481, Ahmed was killed by Ibak Khan, the prince of the Khanate of Sibir, and Nogays at the mouth of the Donets River.[119]

Ahmed’s sons were unable to maintain the Great Horde. They attacked the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (which possessed much of Ukraine at the time) in 1487–1491 and reached as far as Lublin in eastern Poland before being decisively beaten at Zaslavl.[120]

The Crimean Khanate, which had become a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire in 1475, subjugated what remained of the Great Horde, sacking Sarai in 1502. After seeking refuge in Lithuania, Sheikh Ahmed, last Khan of the Horde, died in prison in Kaunas some time after 1504. According to other sources, he was released from the Lithuanian prison in 1527.[121]

Records of Golden Horde existence reach however as far as end of 18th century and it was mentioned in works of Russian publisher Nikolay Novikov in his work of 1773 «Ancient Russian Hydrography».[122]

Astrakhan Khanate (1466)

After 1466, Mahmud bin Küchük’s descendants continued to rule in Astrakhan as the khans of the Astrakhan Khanate.[123]

Russian conquests

The Tsardom of Russia conquered the Khanate of Kazan in 1552, the Khanate of Astrakhan in 1556, and the Khanate of Sibir in 1582. The Crimean Tatars wreaked havoc in southern Russia, Ukraine and even Poland in the course of the 16th and early 17th centuries (see Crimean–Nogai slave raids in Eastern Europe), but they were not able to defeat Russia or take Moscow. Under Ottoman protection, the Khanate of Crimea continued its precarious existence until Catherine the Great annexed it on April 8, 1783. It was by far the longest-lived of the successor states to the Golden Horde.

Tributaries

The Golden Horde and its Rus’ tributaries in 1313 under Öz Beg Khan

The subjects of the Golden Horde included the Rus’ people, Armenians, Georgians, Circassians, Alans, Crimean Greeks, Crimean Goths, Bulgarians, and Vlachs. The objective of the Golden Horde in conquered lands revolved around obtaining recruits for the army and exacting tax payments from its subjects. In most cases the Golden Horde did not implement direct control over the people they conquered.[124]

Influence

For three centuries, Mongol (or Tatar) presence was an undeniable fact for Russians. Although defined as Russians here, there was no «Russian people» or Russian nation during the period of Mongol rule, and therefore no cohesive national response. Aristocratic Russians responded more uniformly to Mongol rule but the same cannot be said with certainty for the peasantry. There is not much evidence for Mongol influence on the Russian peasantry, whose direct contact with the Mongols was mainly through slavery or forced labor. Russian sources generally tend to focus on military encounters with the Mongols but the literary prose betrays a greater Mongol impact on Russian society than accepted at face value. There was a great deal of familiarity with the Mongols among writers, who recorded the name of virtually every Mongol prince, grandee, and official they came into contact with. The Galician–Volhynian Chronicle recounts the words of Tovrul, a captured informant at the Siege of Kiev (1240), who identifies the Mongol captains by name. Russian sources contain a list of the khans of the Golden Horde as well as more detail on their careers during the time of Great Troubles than Arab-Persian sources. Even the names of numerous lesser ranked Mongols are mentioned. The Mongol khan was called tsar, a title also used for the basileus.[125][126] It is evident that the writers expected their audience to be familiar with the names of individual Mongols and their attributes despite their pervasive hostility.[126]

While the Mongols generally did not directly administer the Eastern European lands they conquered, in the cases of the Principality of Pereyaslavl, Principality of Kiev, and Podolia, they removed the native administration altogether and replaced it with their own direct control. The Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, Principality of Smolensk, Principality of Chernigov, and Principality of Novgorod-Seversk retained their princes but also had to contend with Mongol agents who enforced recruitment and tax collection. The Novgorod Republic was exempt from the presence of Mongol agents after 1260 but still had to pay taxes. The Mongols took censuses of Rus’ lands in 1245, 1258, 1259, 1260, 1274, and 1275. No further censuses were taken after that. Some places such as the town of Tula became the personal property of individual Mongols such as the Khatun Taidula, the mother of Jani Beg.[124]

The Russian aristocracy had to familiarize themselves with the workings of Mongol society.[127] The Rus’ prince had to receive a patent for his throne from the khan, who then sent an envoy to install the prince on his throne. From the time of Öz Beg Khan on, a commissioner was appointed by the khan to reside at each of the Rus’ principalities’ capitals. Mongol rule loosened in the late 13th century so that some Rus’ princes were able to collect taxes as the khan’s agents. By the early 14th century, all the grand dukes were collecting taxes by themselves, so that the average people no longer dealt with Mongol overlords while their rulers answered to Sarai.[128]

Aristocratic familiarity with Mongol customs did not result in adopting Mongol culture. Any partiality shown towards Mongol customs could be dangerous, although in one instance they did adopt Mongol military attire. After visiting Batu’s camp in 1245, Daniel of Galicia was visibly influenced by the Mongols, and equipped his army in the Mongol fashion. Austrian visitors to his camp remarked that all of Daniel’s horsemen dressed like Mongols. The only one who did not was Daniel himself, who dressed according to «the Russian custom».[22] Mongols that moved into Russian society shed their former customs as they adopted Orthodox Christianity and despite the numerous mentions of Mongol atrocities, some more honorable portrayals do exist. In the «Tale of the Destruction of Riazan’ by Batu» the Mongol Batu exhibited chivalric courtesy to the Russian noble Evpatii by allowing his men to carry him off the field in honor of his bravery. Russian nobles also fought alongside the Mongols as allies at times.[127]

Intermarriage did happen but was rare. Fedor Rostyslavovich, Yury of Moscow, and Gleb Vasil’kovich married Mongol princesses. Vasil’kovich spent his entire career among the Mongols in the steppes. Urus Khan’s mother may have been a Russian princess.[101][129] Such intermarriage ceased after the Golden Horde Mongols converted to Islam until the 15th century when the weakened Horde’s Mongol grandees moved into Muscovite territory. Most of them entered into the service of grand princes, married aristocracy, converted to Christianity, and became assimilated. It is uncertain how much Mongol Tatar blood entered the Russian aristocracy. Some Mongols might have changed their names after converting while Russians took on Mongol nicknames as patronyms. The nobles of Ryazan and the Godunov clan of prince Chet claimed Tatar descent. Mongol ancestry was considered as prestigious as German, Latin, and Greek ancestry in the 16th century, although such views declined dramatically after the Time of Troubles.[129] There was also intermarriage with their other subjects, such as between Berke and a Seljuk princess, and Jöge (eldest son of Nogai) and a Bulgarian princess.[130][131]

Russian Orthodox Church

The Mongols required the Russian Orthodox Church to pray for the health of the khan and in return they looked after the church’s health and fostered its growth. A bishopric was established in Sarai for Russians and to act as an intermediary between the Golden Horde and both the Russian Church and Byzantium. The khans granted the Church significant tax privileges which enabled it to recover from the invasion and prosper even more than before. It was during the 14th century that the Church made decisive inroads into the pagan countryside, possibly due to the attraction of economic benefits bestowed upon Church lands that incentivized peasants to settle. The «Tale of Peters, tsarevich of the Horde» was written in the 14th century. It tells of how the Mongol Peter, a descendant of Genghis Khan, converted and founded the Petrov monastery. Peter’s descendants used their ties to the khans to protect the monastery from the Rostov princes and the neighboring Russians who desired the fishing rights to that land. The depiction of Mongols by Chuch was mixed and awkward. It portrayed them as a disaster and their caretaker. This contradiction can be seen in the khans’ portrayals in Church texts. Where the khans’ names would have been in the missals, there was a blank space for the name to be read aloud orally. There was also a careful delineation between khan and «Tatars». Hagiographers sometimes absolved the khans from their role in killing Russian princes. After the khans’ power began to wane in the 14th century, the Church gave its full backing to the Russian princes. However even after Mongol rule ended, the Church still invoked the Mongol model as an example of how they should be treated. In the 16th century, churchmen circulated a translated Mongol yarlyk that granted tax immunity to the Church.[132]

Administration

The Grand Duchy of Moscow adopted the Mongol tax system and continued to collect tribute after they stopped passing it onto the Golden Horde. The Muscovite grand princes replaced the Mongol basqaq with officials called danshchiki who collected tribute known as dan’, which was probably modeled after the Mongol tribute system. The Russians adopted the Mongol word for treasury, kazna, treasurer, kaznachey, and money, den’ga. The Muscovites used the Mongol customs tax system called tamga, from which the Russian word tamozhnya (customs house) is derived from.[133] The yam postal system was adopted by Russia in the late 15th century as the peasants had already been paying a yam tax for centuries. The practice of poruka, collective responsibility of a sworn group, became more common in Russia during the Mongol period and may have been influenced by the Mongols. The Mongols may have spread the practice of beating the shins as a punishment from China to Russia, where this punishment for nonpayment of debts was called pravezh.[134]

Military

Some of the Mongols’ subjects adopted Mongol military accoutrements. In 1245, Daniel of Galicia’s army was dressed in the Mongol fashion after a visit to Batu Khan’s camp. Austrian visitors to Daniel’s camp remarked that with the exception of Daniel himself, all the horsemen dressed like Mongols.[22] Muscovite cavalrymen were equipped in a similar fashion to the Mongols as late as the 16th century, when they were depicted using a Mongol-style saddle with Mongol stirrups, wearing a Mongol helmet, and armed with a Mongol bow and quiver. European observers mistook them for Ottoman dress. Muscovite armies also deployed in a similar fashion to the Mongols with the right guard ranked above the left (due to a shamanist belief). The emphasis on cavalry declined in the 16th century as warfare increasingly involved sieges in Eastern Europe than on the steppes with nomadic horsemen.[135]

Decline

|

|

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia’s quality standards, as The second part of this chapter is a carbon copy of other paragraphs. It should explain how the Golden Horde lost its administrative influence, not historical events already described. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (October 2020) |

Mongol rule in Galicia ended with its conquest by the Kingdom of Poland (1025–1385) in 1349. The Golden Horde entered severe decline after the death of Berdi Beg in 1359, which started a protracted political crisis lasting two decades. In 1363, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania won the Battle of Blue Waters against the Golden Horde and conquered both Kiev and Podolia. After 1360, payment of tribute and taxes from Rus’ subjects to the declining Golden Horde decreased significantly. In 1374, Nizhny Novgorod rebelled and slaughtered an embassy sent by Mamai. For a brief period after the victorious Battle of Kulikovo in 1380 by Dmitry Donskoy against Mamai, the Grand Duchy of Moscow was free of Mongol control until Tokhtamysh restored Mongol suzerainty over Moscow two years later with the Siege of Moscow (1382).[136] Tokhtamysh also crushed the Lithuanian army at Poltava in the next year.[104] Władysław II Jagiełło, Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland, accepted his supremacy and agreed to pay tribute in turn for a grant of Rus’ territory.[105] In 1395, Timur annihilated Tokhtamysh’s army again at the Battle of the Terek River, destroyed his capital, looted the Crimean trade centers, and deported the most skillful craftsmen to his own capital in Samarkand. Timur’s forces reached as far north as Ryazan before turning back. Tokhtamysh fled to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and asked Vytautas for assistance in retaking the Golden Horde in exchange for suzerainty over the Rus’ lands. In 1399, Vytautas and Tokhtamysh attacked Temür Qutlugh and Edigu at the Battle of the Vorskla River but were defeated. The Golden Horde victory secured for it Kiev, Podolia, and some land in the lower Bug River basin. Tokhtamysh died in obscurity in Tyumen around 1405. His son Jalal al-Din fled to Lithuania and participated in the Battle of Grunwald against the Teutonic Order.[137]

From 1400 to 1408, Edigu gradually regained control of the eastern Rus’ tributaries, with the exception of Moscow, which he failed to take in a siege but ravaged the surrounding countryside. Smolensk was lost to Lithuania.[137] After Edigu died in 1419, the Golden Horde rapidly disintegrated but it still retained some vestige of influence in Eastern Europe. In 1426, Ulugh Muhammad contributed troops to Vytautas’ war against Pskov and despite the horde’s reduced size, both Yury of Zvenigorod and Vasily Kosoy still visited Ulugh Muhammad’s court in 1432 to request a grand ducal patent. A year later, Ulugh Muhammad was ousted and fled to the town of Belev on the upper Oka River, where he came into conflict with Vasily II of Moscow, whom he defeated twice in battle. In 1445, Vasily II was taken prisoner by Ulugh Muhammad and ransomed for 25,000 rubles. Ulugh Muhammad was murdered in the same year by his son, Mäxmüd of Kazan, who fled to the middle Volga region and founded the Khanate of Kazan.[113]

In 1447, Mäxmüd sent an army against Muscovy but was repelled. Another of Ulugh Muhammad’s sons, Qasim Khan, fled to Moscow, where Vasily II granted him land that became the Qasim Khanate[114] Both the khans Küchük Muhammad and Sayid Ahmad attempted to reassert authority over Moscow. Küchük Muhammad attacked Ryazan and suffered a major defeat against the forces of Vasily II. Sayid Ahmad continued to raid Muscovy and in 1449 made a direct attack on Moscow. However he was defeated by Muscovy’s ally Qasim Khan. In 1450, Küchük Muhammad attacked Ryazan but was turned back by a combined Russo-Tatar army. In 1451, Sayid Ahmad tried to take Moscow again and failed.[118]

In the summer of 1470, Ahmed Khan bin Küchük, ruler of the Great Horde, organized an attack against Moldavia, the Kingdom of Poland, and Lithuania. By August 20, the Moldavian forces under Stephen the Great defeated the Tatars at the battle of Lipnic. In 1474 and 1476, Ahmed insisted that Ivan III of Russia recognize the khan as his overlord. In 1480, Ahmed organized a military campaign against Moscow, resulting in a face off between two opposing armies known as the Great Stand on the Ugra River. Ahmed judged the conditions unfavorable and retreated. This incident formally ended the «Tatar Yoke» over Rus’ lands.[119]

Trade

Sarai carried on a brisk trade with the Genoese trade emporiums on the coast of the Black Sea – Soldaia, Caffa, and Azak. Mamluk Egypt was the Khans’ long-standing trade partner and ally in the Mediterranean. Berke, the Khan of Kipchak had drawn up an alliance with the Mamluk Sultan Baibars against the Ilkhanate in 1261.[138]

A change in trade routes

According to Baumer[139] the natural trade route was down the Volga to Serai where it intersected the east-west route north of the Caspian, and then down the west side of the Caspian to Tabriz in Persian Azerbaijan where it met the larger east-west route south of the Caspian. Around 1262 Berke broke with the Il-Khan Hulagu Khan. This led to several wars on the west side of the Caspian which the Horde usually lost. The interruption of trade and conflict with Persia led the Horde to build trading towns along the northern route. They also allied with the Mamluks of Egypt who were the Il-Khan’s enemies. Trade between the Horde and Egypt was carried by the Genoese based in Crimea. An important part of this trade was slaves for the Mamluk army. Trade was weakened by a quarrel with the Genoese in 1307 and a Mumluk-Persian peace in 1323. Circa 1336 the Ilkhanate began to disintegrate which shifted trade north. Around 1340 the route north of the Caspian was described by Pegolotti. In 1347 a Horde siege of the Genoese Crimean port of Kaffa led to the spread of the black death to Europe. In 1395-96 Tamerlane laid waste to the Horde’s trading towns. Since they had no agricultural hinterland many of the towns vanished and trade shifted south.[citation needed]

Geography and society

Genghis Khan assigned four Mongol mingghans: the Sanchi’ud (or Salji’ud), Keniges, Uushin, and Je’ured clans to Jochi.[140] By the beginning of the 14th century, noyans from the Sanchi’ud, Hongirat, Ongud (Arghun), Keniges, Jajirad, Besud, Oirat, and Je’ured clans held importants positions at the court or elsewhere. There existed four mingghans (4,000) of the Jalayir in the left wing of the Ulus of Jochi (Golden Horde).

The population of the Golden Horde was largely a mixture of Turks and Mongols who adopted Islam later, as well as smaller numbers of Finnic peoples, Sarmato-Scythians, Slavs, and people from the Caucasus, among others (whether Muslim or not).[141] Most of the Horde’s population was Turkic: Kipchaks, Cumans, Volga Bulgars, Khwarezmians, and others. The Horde was gradually Turkified and lost its Mongol identity, while the descendants of Batu’s original Mongol warriors constituted the upper class.[142] They were commonly named the Tatars by the Russians and Europeans. Russians preserved this common name for this group down to the 20th century. Whereas most members of this group identified themselves by their ethnic or tribal names, most also considered themselves to be Muslims. Most of the population, both agricultural and nomadic, adopted the Kypchak language, which developed into the regional languages of Kypchak groups after the Horde disintegrated.

The descendants of Batu ruled the Golden Horde from Sarai Batu and later Sarai Berke, controlling an area ranging from the Volga River and the Carpathian mountains to the mouth of the Danube River. The descendants of Orda ruled the area from the Ural River to Lake Balkhash. Censuses recorded Chinese living quarters in the Tatar parts of Novgorod, Tver and Moscow.

Internal organization

Tilework fragments of a palace in Sarai.

The Golden Horde’s elites were descended from four Mongol clans, Qiyat, Manghut, Sicivut and Qonqirat. Their supreme ruler was the Khan, chosen by the kurultai among Batu Khan’s descendants. The prime minister, also ethnically Mongol, was known as «prince of princes», or beklare-bek. The ministers were called viziers. Local governors, or basqaqs, were responsible for levying taxes and dealing with popular discontent. Civil and military administration, as a rule, were not separate.

The Horde developed as a sedentary rather than nomadic culture, with Sarai evolving into a large, prosperous metropolis. In the early 14th century, the capital was moved considerably upstream to Sarai Berqe, which became one of the largest cities of the medieval world, with 600,000 inhabitants.[143] Sarai was described by the famous traveller Ibn Battuta as «one of the most beautiful cities … full of people, with the beautiful bazaars and wide streets», and having 13 congregational mosques along with «plenty of lesser mosques».[144] Another contemporary source describes it as «a grand city accommodating markets, baths and religious institutions».[144] An astrolabe was discovered during excavations at the site and the city was home to many poets, most of whom are known to us only by name.[144][145]

Despite Russian efforts at proselytizing in Sarai, the Mongols clung to their traditional animist or shamanist beliefs until Uzbeg Khan (1312–41) adopted Islam as a state religion. Several rulers of Kievan Rus’ – Mikhail of Chernigov and Mikhail of Tver among them – were reportedly assassinated in Sarai, but the Khans were generally tolerant and even released the Russian Orthodox Church from paying taxes.

Provinces

The Mongols favored decimal organization, which was inherited from Genghis Khan. It is said that there were a total of ten political divisions within the Golden Horde. The Golden Horde majorly was divided into Blue Horde (Kok Horde) and White Horde (Ak Horde). Blue Horde consisted of Pontic–Caspian steppe, Khazaria, Volga Bulgaria, while White Horde encompassed the lands of the princes of the left hand: Taibugin Yurt, Ulus Shiban, Ulus Tok-timur, Ulus Ezhen Horde.

Vassal territories

- Venetian port cities in Crimea (center at Qırım). After the Mongol conquest in 1238, the port cities in Crimea paid the Jochids custom duties, and the revenues were divided among all Chingisid princes of the Mongol Empire in accordance with the appanage system.,[146]

- the banks of Azov,

- the country of Circassians,

- Walachia,

- Alania,

- Russian lands.[147]

Genetics

A 2016 study analyzed the DNA of 5 graves in Tavan Tolgoi, Mongolia, identified as members of the Mongol Golden Family.[148] The male individuals identified as Golden Family members belonged to the West Eurasian paternal haplogroup R1b-M343.[149] Their mitochondrial haplogroup was identified as the East Asian D4.[150] The authors proposed that R1b may be the patrilineal lineage of Genghis Khan, and that the R1b-carrying Tavan Tolgoi specimens were the descendants of prior mixed marriages between West Eurasian migrants and women indigenous to the Mongolian plateau. The authors observed a special link between haplogroup R1b-M343 and the populations residing in the former territory of the Golden Horde, noting a high frequency of R1b-M343 among populations such as the Hazara, as well as Bashkirs and Eastern Russian Tatars.[151][152]

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of two Golden Horde males buried in the Ulytau District in Kazakhstan ca. 1300 AD.[153] One male, who was a Buddhist warrior of Mongoloid origin,[154] carried paternal haplogroup C3[155] and the maternal haplogroup D4m2.[156] The other male, who was Caucasian and possibly a slave or servant,[157][154] was a carrier of the paternal haplogroup R1[158] and the maternal haplogroup I1b.[159]

Coinage

-

Talabuga’s coin, dating c. 1287–1291 AD.

-

Jani Beg’s coin, dating c. 1342–1357 AD.

-

Berdi Beg’s coin minted in Azak, dating c. 1357 AD.

-

Kildibeg’s coin minted in Sarai, dating c. 1360 AD.

-

Ordumelik’s coin minted in Azak, dating c. 1360 AD.

-

Muscovite coin minted in the name of Abdullah ibn Uzbeg, dating c. 1367–1368 or 1369–1370

-

Dawlat Berdi’s coin minted in Kaffa, dating c. 1419–1421 or 1428–1432 AD.

Gallery

-

Golden Horde raid at Ryazan

-

Golden Horde raid at Kiev

-

Golden Horde raid at Kozelsk

-

Golden Horde raid Vladimir

-

Golden Horde raid Suzdal

-

Mongol-Tatar warriors besiege their opponents.

-

The Mongol army captures a Rus’ city

-

Mongol invasion of Hungary in 1285

-

Drawing of Mongols of the Golden Horde outside Vladimir presumably demanding submission before sacking the city

-

Mongol-Tatar raid

-

A Rus’ prince being punished by the Golden Horde

See also

- Cuman people

- Mongol invasion of Rus’

- Russo-Kazan Wars

- Tatar invasions

- Tokhtamysh–Timur war

- Volga Bulgaria

- Division of the Mongol Empire

- Berke–Hulagu war

- History of the western steppe

- List of Khans of the Golden Horde

- List of medieval Mongol tribes and clans

- List of Mongol states

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- Jarlig

Reference and notes

- ^ a b c Kołodziejczyk (2011), p. 4.

- ^ Halperin 1986, p. 59.

- ^ Zahler, Diane (2013). The Black Death (Revised ed.). Twenty-First Century Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4677-0375-8.

- ^ Mustafayeva, A.A.; Aubakirova, K.K.. «The language situation and status of the Turkic language in the Egyptian Mamluk state and Golden Horde». Journal of Oriental Studies, [S.l.], v. 97, n. 2, p. 17-25, June 2021. ISSN 2617-1864. Available at: <https://bulletin-orientalism.kaznu.kz/index.php/1-vostok/article/view/1689>. Date accessed: 01 sep. 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.26577/JOS.2021.v97.i2.02.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). «East-West Orientation of Historical Empires». Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). «Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia». International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 498. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- ^ German A. Fedorov-Davydov The Monetary System of The Golden Horde*. Translated by L. I. Smirnova (Holden). Retrieved: 14 July 2017.

- ^ «The History and Culture of the Golden Horde (Room 6)». The State Hermitage Museum, Sankt Petersburg. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Perrie, Maureen, ed. (2006). The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume 1, From Early Rus’ to 1689. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-81227-6.

- ^ a b «Golden Horde». Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007.

Also called Kipchak Khanate Russian designation for Juchi’s Ulus, the western part of the Mongol Empire, which flourished from the mid-13th century to the end of the 14th century. The people of the Golden Horde were mainly a mixture of Turkic and Uralic peoples and Sarmatians & Scythians and, to a lesser extent, Mongols, with the latter generally constituting the aristocracy. Distinguish the Kipchak Khanate from the earlier Cuman-Kipchak confederation in the same region that had previously held sway, before its conquest by the Mongols.

- ^ Atwood (2004), p. 201.

- ^ «рЕПЛХМ гНКНРЮЪ нПДЮ — НЬХАЙЮ РНКЛЮВЮ 16 ЯРНКЕРХЪ (мХК лЮЙЯХМЪ) / оПНГЮ.ПС — МЮЖХНМЮКЭМШИ ЯЕПБЕП ЯНБПЕЛЕММНИ ОПНГШ». Proza.ru. Retrieved 2014-04-11.